Abstract

After World War II, consumer patterns of food consumption changed dramatically. Initially, it was mobility, economic evolution, and home appliance technologies that induced a shift toward meals eaten outside of the home and to ready-to-eat foods at home. More recently, health concerns and sustainability issues shifted consumer tastes among meat products and gave rise to a change in attitudes about raising animals for human consumption. On the supply side, new technologies in nonmeat production enabled new producers, most notably Impossible Foods and Beyond Meat, to enter as fringe competitors to vertically integrated, oligopolistic meat processors. Today, these nonmeat products represent a small, but growing, share of consumer expenditures at grocery stores, restaurants, and direct-to-consumer delivery channels. In this paper, we evaluate the disruption of the traditional meat industry through the lens of consumer spending trends and substitution among meat products and find that the development of alternative meat products is market-driven rather than policy-driven. Given these findings, we identify implications for product development and industrial organization.

Keywords: Plant-based, Cell-based, Cultured meat, Cultural complements

Introduction

In 2019, a major coup was executed in the meat industry. An ensconced fast-food giant, Burger King, home of the Whopper, introduced its newest product, the Impossible Whopper, as “100% Whopper, 0% beef.” That same year Dunkin’ Donuts introduced the Beyond Sausage Egg and Cheese sandwich. Alternative meat made a direct hit into the heart of America’s food culture: the fast-food industry.

The main interests of this paper are to evaluate the potential disruptive effects of alternative meat products developed, most prominently from new plant-based technology, on the U.S. meat industry, defined to include beef, pork, poultry, and other meat products.1 We argue that the main motivations for why consumers, particularly those who are younger, seem willing to substitute to alternative meat products are as follows: (1) the product characteristics are very similar to meat; (2) the products are made widely available through fast-food restaurants, retail grocery stores, and direct-to-consumer distribution; (3) the production of these products satisfy consumer attitudes about healthy eating, sustainable production, and an avoidance of animal slaughter; and (4) the prices of the products are competitive to meat products in the relevant market segments. That is, it is the market that is mainly driving the development of nonmeat products.

We note that several factors may deter adoption by meat eaters and flexitarians to nonmeat products. The most important is how closely products can mimic real meat staples in taste, texture, appearance, perception, and use. In addition, cultural complements—norms in meat use—weigh heavily on consumer choice and only very close substitutes that are priced competitively will thrive. We conclude that meat is here to stay, but so are alternative nonmeat products. We expect:

Production on a large enough scale to tap the market potential will likely require vertically integrated firms that have sufficient capital to finance investment in R&D and production capacity. Vertical integration will permit producers to address packaging and marketing on a broad scale by channel. Smaller niche producers are not likely to be foreclosed from the market, but mass marketing and distribution demands will require a certain minimum efficient scale.

Continued improvement in nonmeat substitutes for lower value meat products and mass-market offerings (e.g., hamburger, chicken tenders, sausage) will result in a proliferation of horizontally differentiated products by sales channel.

Continued improvement in taste, texture, and form will permit vertical differentiation in higher-value substitutes by channel.

The market structure that evolves will consist of a relatively few large firms managing broad portfolios of branded products, akin to the breakfast cereal and beverage industries.

Market size and participants

In 2019, McKinsey and Company (2019) estimated that the size of the global markets for alternative meats and traditional meat products were roughly $2.2 billion and $1.7 trillion, respectively. The consulting firm predicted, however that the growth rate of meat would decline significantly, in large measure because of the increase in popularity and availability of nonmeat products. By 2030, Statista (2020) expects that nonmeat alternatives will account for 28% of the worldwide meat and meat alternative market.

In the U.S., the leading producers of meat alternatives are Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods. 2009, Beyond Meat provides product in approximately 130,000 retail and foodservice outlets across the U.S. Europe, and China.2 In 2021, the firm brought in $464.5 million in revenue, the majority of which was earned in the US.3 Privately held Impossible Foods, founded in 2011, is in 20,000 grocery stores and 40,000 restaurants in seven countries.4 and is valued at approximately $7 billion.5

While the new entrants had the first mover advantage in the plant-based product space, traditional meat processing firms had the resources and established vertical relationships to scale quickly.6 Over the past 3 years, agricultural conglomerates such as Tyson, JBS, Cargill, National Beef, Smithfield, Sanderson Farms, and Perdue Foods introduced competitive plant-based products.

Tastes, technology, and distribution (or the market: demand & supply)

But in capitalist reality as distinguished from its textbook picture, it is not that kind of competition [price competition] which counts but the competition from the new commodity, the new technology, the new source of supply, the new type of organization (the largest-scale unit of control for instance)—competition which commands a decisive cost or quality advantage and which strikes not at the margins of the profits and the outputs of the existing firms but at their foundations and their very lives. This kind of competition is as much more effective than the other as a bombardment is in comparison with forcing a door, and so much more important that it becomes a matter of comparative indifference whether competition in the ordinary sense functions more or less promptly; the powerful lever that in the long run expands output and brings down prices is in any case made of other stuff. (Schumpeter 1942)

This passage from Schumpeter is often quoted because it is timeless. Its message is as applicable to the invention of the light bulb that led to the demise of the gas lighting industry as it is to the widespread adoption of mobile telephony and its effect on the wireline network subscription, and its apparent applicability to technological innovations in producing nonmeat alternatives. Why? Because technological breakthroughs affect the extensive margin, and the choice over substitutable alternatives whose characteristics are fundamentally different in composition, in use, or in taste. Impossible Foods and Beyond Meat made it a point to develop products that are similar in use and similar in taste, texture, and appearance to meat products when sold and cooked, despite their fundamental difference in composition. By developing very close substitutes to meat products, they expanded their appeal to consumers who are meat eaters and not just consumers who choose not to eat meat.7 This is not to say that price is unimportant. We find that consumers are fairly price sensitive in choosing between meat products, especially in the short run. However, further enhancements of product characteristics that enable alt-meat products to approach perfect substitutability will lead to wider market acceptance in the end, not only by vegetarian segments but also by consumers who buy and eat meat.

Currently, the main technologies used in producing alternative meats are either plant-based or cell-based.8 The products from the two industry leaders, Impossible Foods and Beyond Meat, are plant based but differ in that Impossible Foods uses soy-based protein, while Beyond Meat combines pea proteins with other bean sources.

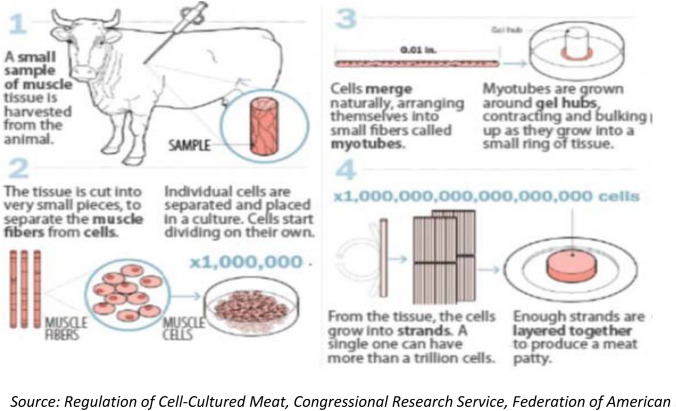

Cell-based research is in its infancy and there is currently no commercial product available on a widespread basis in any markets except Singapore.9 Cell-based production takes place in the laboratory and is developed by cultivating the stem cells drawn from the particular animal (e.g., cow, pig). While cell-based meat products do not eliminate meat, they do bypass the typical farm or ranch to slaughterhouse process and, therefore, reduce the environmental and animal welfare concerns of a segment of the consumer market. Figure 1 shows the cell-based meat creation process schematically.

Fig. 1.

Cell-based meat production.

Source: Regulation of Cell-Cultured Meat, Congressional Research Service, Federation of American Scientists (October 2018)

Innovation in distribution—retail and food service channels

Traditional food products are delivered through a supply chain beginning with the farm, moving through processing stages and wholesalers, and then finally reaching the consumer in grocery stores, warehouse clubs, and farmers’ markets. The larger retail outlets distribute products made by third parties but often compete in food categories with their own space, Trader Joe’s Foods and Beyond Meat products but also sell their own proprietary brands.10 Smaller alt-meat producers have product promotion as the adoption of nonmeat products. In a tended to buy less substantially more grocery stores (versus large chains), and farmers. For example, No Evil Foods products are sold at the Fresh Market and Wegman’s. Finally, the expansion of direct-to-consumer marketing and sales have enabled producers to bypass some retail buyer segments by using online platforms for product promotion and distribution (Renner et al. 2021). Use of online platforms and social media add a network dimension to the adoption of nonmeat products.

In a study of fresh food buying, Deloitte found that younger consumer groups (independent of income) tended to buy less at traditional grocery stores and substantially more through online methods, local grocery stores (versus large chains), and farmers markets.11 Although frozen is sometimes regarded as an imperfect substitute for fresh, the combination of frozen distribution, with implications assessed a post-Covid acceleration purchases.12 Positive product perceptions along with the desire for wide availability of products opens the door to direct-to-consumer marketing and distribution, with implications for the growth of alternative meat products. In a follow-up study, Deloitte assessed a post-Covid acceleration in online food purchases and found that consumer acceptance of frozen meat is correlated with interest in plant-based meat alternatives (Renner et al. 2021).

For food consumption away from home, Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods products are increasingly found alongside pub fare in casual dining, higher-end restaurants, and sports stadiums. At last count, 12 Major League Baseball parksoffered a range of nonmeat and nondairy products.13 Large food service providers, including US Foods and Aramark, have developed extensive menus based on plant-forward products.14 Seeking differentiation, higher-end restaurants, such as Fleming’s Steakhouse, offer third-party plant-based nonmeat products and their own nonmeat products.15

Trends in U.S. food and meat consumption: what’s for dinner, or shall we just eat out?

For any retail product or service, it is ultimately the consumer who signals through choice what should be profitably produced. Food is no different. Consumer buying patterns reflect a host of factors, including cultural norms, changing tastes, attitudes about health and quality, and cost (that is, the products opens full cost of a meal, including the time used to prepare a meal at home).

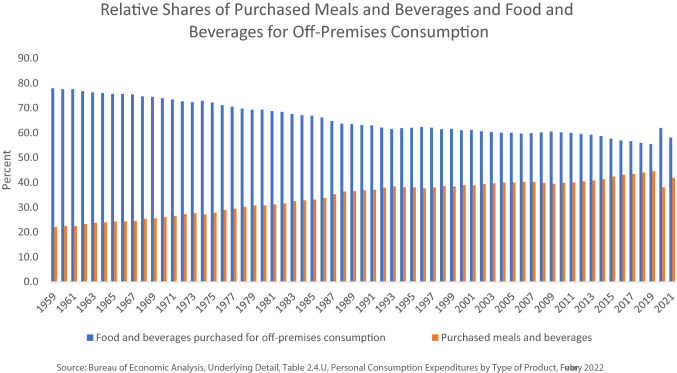

There are several socioeconomic trends that bear on consumer expenditures on meat and choices between meat products. Using data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) Underlying Detail Tables for Consumer Spending, we examine nominal spending for food and beverages purchased for off-premises (at home) consumption and purchased meals and beverages for consumption at public eating places. Table 1 shows 10-year snapshots of the data from 1959 to 2019. In 1959, nominal spending for food at home was $61.6 billion, while spending for purchased meals was roughly $17.5 billion. Almost 78 percent of consumer spending on food was for meals prepared at home. By 2019 that share had diminished to 55.5 percent, a clear reflection of increased consumer preferences for eating out. (Personal Consumer Expenditure-PCE-data for 2020 and 2021 are included. The uptick in 2020 clearly reflects the distortion in normal consumption patterns induced by Covid-19, and the 2022 data appears to show a reversion due to some return to normal activities during that year.)

Table 1.

Food and beverages—off-premises (home) and purchased (away from home)

| Millions of $US, seasonally adjusted at annual rates | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1959 | 1969 | 1979 | 1989 | 1999 | 2009 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |

| Food and beverages purchased for off-premises consumption | $61,597 | $95,371 | $218,370 | $365,388 | $515,530 | $772,930 | $1,030,911 | $1,146,676 | $1,234,693 |

| Share of total (%) | 77.9 | 74.5 | 69.3 | 63.5 | 61.6 | 60.5 | 55.5 | 62.0 | 58.1 |

| Purchased meals and beverages | $17,454 | $32,683 | $96,740 | $210,214 | $321,821 | $504,423 | $828,227 | $703,603 | $890,418 |

| Share of total (%) | 22.1 | 25.5 | 30.7 | 36.5 | 38.4 | 39.5 | 44.5 | 38.0 | 41.9 |

| Total | $79,051 | $128,054 | $315,110 | $575,602 | $837,351 | $1,277,353 | $1,859,138 | $1,850,279 | $2,125,111 |

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Underlying Detail, Table 2.4.5U. Personal Consumption Expenditures by Type of Product

Figure 2 shows the trends in nominal spending for food at home and purchased food from 1959 through 2021. The most recent 2 years clearly reflect the changes due to Covid restrictions on mobility.

Fig. 2.

Relative shares of purchased meals and beverages and food and beverages for off-premises consumption.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Underlying Detail, Table 2.4.U, Personal Consumption Expenditures by Type of Product, February 2022

Two prominent reasons for the rise in the percentage of food and beverages consumed away from home over the past 60 years are increases in societal mobility, and labor force participation by women.

Post-World War II America experienced vast changes in production and consumer technologies that upended the social and economic patterns of life. High personal savings, a consequence of restricted wartime consumption, and an expanding economy enabled increased automobile ownership. The concurrent development of the Interstate Highway system and more widespread local roads reduced the cost of geographically dispersed homeownership and travel time for work and play. One of the byproducts of greater mobility was a fast-food culture, built around the branded franchise drive-in. “Fast food [took off] in large part because of the highway system that we built in the 1950s and the1960s. America started driving more than ever before and we rearranged our cities based on car travel, for better or worse. And it was a natural business response to the American on-the-go kind of lifestyle” (Chandler 2019).

The end of the war also brought a ramp up in non-military economic activity at home and a widespread need for workers. Women responded. In the 50 years between 1949 and 1999, the female labor force participation rate (LFPR) jumped from 33 to 60%.16 Today, the LFPR of women is close to that of men, and more than 50% of U.S. households are dual income.17 As is the case for most consumer products, changes in socioeconomic developments and demographics have consequential effects on product mix and distribution. Food is no exception. From a Beckerian point of view, higher wages and more time allocated to work have increased the shadow price of food prepared at home relative to the prices of ready-to-eat food outside the home, curtailing expenditures for food prepared at home and expanding the markets for ready-to-cook and prepared foods and for eating out.

Consumer spending for meat products

The shift away from consuming food at home is generally explained by changes in income and demographic changes both nationally and regionally. Equally interesting is how consumer choices have affected the composition of expenditure for meat. Table 2 displays real per capita PCE for meat and meat products from 1959 through 2019 by 10-year increments, plus 2020 and 2021.18

Table 2.

Real expenditures per capita $U.S

| Year | 1959 | 1969 | 1979 | 1989 | 1999 | 2009 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beef | $288.31 | $385.08 | $273.66 | $229.06 | $165.55 | $138.84 | $125.70 | $132.05 | $128.26 |

| Pork | $81.00 | $85.73 | $93.77 | $111.11 | $92.34 | $97.68 | $104.08 | $112.59 | $110.30 |

| Other Meat | $67.56 | $80.04 | $67.85 | $70.45 | $82.13 | $94.89 | $100.23 | $107.06 | $110.84 |

| Poultry | $35.18 | $50.15 | $75.46 | $103.80 | $154.23 | $153.75 | $166.27 | $180.96 | $183.17 |

| Total Meat | $472.05 | $601.00 | $510.75 | $514.42 | $494.25 | $485.15 | $496.28 | $532.65 | $532.57 |

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Underlying Detail, Table 2.4.5U, Personal Consumption Expenditures by Type of Product, February 2022

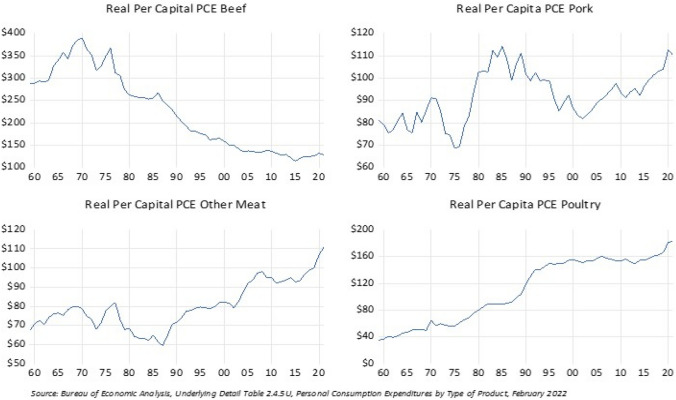

What is most obvious is thechanging shares of beef and chicken in the consumer budget. In 1959, of the $472.05 an average person spent on meat in real terms, $288.31 was spent on beef and $35.18 was spent on chicken. As percentages, beef represented 61 percent of consumer expenditure on meat, while poultry accounted for approximately 7 percent. By 2009, real per capita spending for chicken had eclipsed that for beef, representing 31.5 percent of expenditures versus 28.5 percent. By 2020, the per capita expenditure on chicken was more than four times greater than what it was in 1959, while the expenditure on beef had fallen by more than half. Over the same time period, pork became a slightly more important meat product in the consumer budget, increasing from $81.00 in 1959, or 17 percent of total meat real expenditures per capita, to $112.59 in 2020, representing 21 percent of a typical consumer’s expenditure on meat. One can detect a peak in pork consumption in the late 1980’s, coincident to the “Pork, The Other White Meat” advertising campaign. The steady increase in Other Meat products, which are largely prepared meats and ready-to-eat meat products, provides some evidence of the consumer preference for quick and easy foods to prepare (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Real per capital spending by meat product.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Underlying Detail, Table 2.4.5U, Personal Consumption Expenditures by Type of Product, February 2002

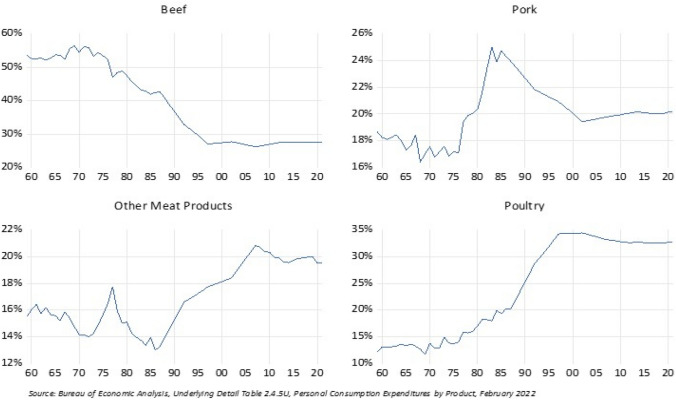

The consumer budget choices shown in Table 2 and Fig. 2 are reflected in the expenditure shares of meat products in Table 3 and Fig. 4 below. The dramatic substitution away from beef and especially to poultry and ready-to-eat processed meat over the decades is apparent. The shifts reflect several likely causal factors including relative price.

Table 3.

Expenditure shares of meat products (percent)

| Year | 1959 | 1969 | 1979 | 1989 | 1999 | 2009 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beef | 61.1 | 64.1 | 53.6 | 44.5 | 33.5 | 28.6 | 25.3 | 24.8 | 24.1 |

| Pork | 17.2 | 14.3 | 18.4 | 21.6 | 18.7 | 20.1 | 21.0 | 21.1 | 20.7 |

| Other Meat | 14.3 | 13.3 | 13.3 | 13.7 | 16.6 | 19.6 | 20.2 | 20.1 | 20.8 |

| Poultry | 7.5 | 8.3 | 14.8 | 20.2 | 31.2 | 31.7 | 33.5 | 34.0 | 34.4 |

| Total Meat | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Underlying Detail, Table 2.4.5U, Personal Consumption Expenditures by Type of Product, February 2022

Fig. 4.

Shares of expenditures for meat products.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Underlying Detail, Table 2.4.5U, Personal Consumption Expenditures by Type of Product, February 2002

We argue that the secular shift is in some part cultural, due to increased concern of consumers about the health effects of beef consumption and more recently, the preference for more sustainable and humane concerns in the production of meat.

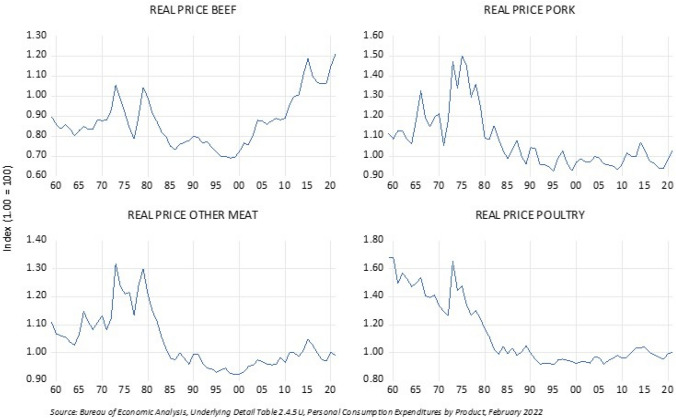

Figure 5 shows the relative prices by meat product. The values were calculated using BEA’s price indexes for beef, pork, other meat products, and poultry, and then deflating by the overall PCE price index. Beef prices have increased in real terms fairly sharply since 2000, while the prices of pork, poultry, and other meat products began falling in the 1970s and have remained relatively stable since that time.

Fig. 5.

Real prices of meat products.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Underlying Detail, Table 2.4.5U, Personal Consumption Expenditures by Type of Product, February 2002

In the next section, we present empirical evidence of price elasticities of the demand for meat products and the influence of demographic factors on meat choices.

Price and nonprice factors in the demand for meat products

Price elasticities and implications for nonmeat product demand

A traditional way to empirically estimate consumer demand and expenditure for goods and services was initially developed by Stone (1954). Using the related Almost Ideal System (Deaton and Muellbauer 1980), Roosen et al. (2022) estimated price elasticities for meat products in Germany, by income and age, in order to assess the welfare effects of increasing Value Added taxes on meat. The authors found that the expenditure elasticities for beef, pork, and poultry were greater than 1.0. They also found that higher-income groups were more price sensitive for all meat products than were lower-income groups, perhaps because lower-income groups purchase lower grades of meat (e.g., hamburger, store brands). By age, the authors found that price elasticities for all products were slightly higher for older consumers than younger consumers.

Lee et al. (2020) examined demand for meat products by age and by age cohort. Using several datasets from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), they applied a two-stage framework to analyze the direct and indirect impacts of price on meat product demand. They found that older cohorts (those born in an earlier time) purchased less poultry than younger cohorts when measured at the same age. They also found that purchase of poultry increased with age relative to beef and pork, and that beef had the highest own-price elasticity among all meat products.

Their results suggest a price-age explanation to the observed trends in the changing shares among meat products. Moreover, as the relative price of beef increased, and the relative price of poultry and other meat products decreased, there was a substitution away from beef to other meat products, especially poultry.

An alternative approach to estimating product demand is by directly modeling individual consumer choice relative to alternative products conditional upon product characteristics, price, and demographic influences. Lusk and Tonsor (2016) applied a discrete choice approach to modeling the demand for meat products by type (e.g., premium cut like In fact, steak or chicken breast) at different price points. Their some study is unique in that it was conducted during a period of high prices for meat. The authors found that higher-income consumers were less responsive to price than middle-income and lower-income consumers for all product types—superior cuts and inferior cuts of beef, pork, and chicken. Higher-income consumers were also much more likely to consume premium cuts of products (steak, chicken breasts) than were lower-income consumers, while lower-income consumers were more likely to consume cheaper cuts. Their nonlinear demand estimates implied that demand was less elastic at higher prices. That is, price changes at high price levels did not induce as much consumer response as they did at low price levels. They also found that own-price elasticities were smaller for price increases than for decreases, cross-elasticities were generally higher for price increases than decreases, and that cross-elasticities were not symmetric.19

In the Appendix, we provide our estimates of price health concerns, environmental and sustainability concerns, cross-price elasticities, and expenditure and ethical treatment of animal stock elasticities. Our findings are consistent with a number of the results in the reviewed research, notably (1) the own-price elasticity of beef is higher than other meats; (2) cross-price elasticities are not symmetric across products; and (3) expenditure elasticities for meat indicate a high value for meat products, especially beef.

Implications for nonmeat product development and expansion

What do these studies suggest for the entry and expansion of alternative meat products? The first point is that the meat market is best addressed by type of meat or cut, and that the product that is introduced in that submarket must have characteristics (look, feel, taste, texture) that are similar to the existing product. Impossible and Beyond Meat are doing just that. They are targeting the meat-eating consumer submarkets that share real meat characteristics. This permits substitution at the margin. It also suggests that the current capabilities of Impossible Foods and Beyond Meat are concentrated at the lower end and more price sensitive product types—ground beef, ground pork, and chicken tenders. Further expansion into higher-value products, like chicken breasts, will require forms that are similar to the meat product they wish to mimic. This is not an “impossible” task. In fact, some nonmeat faux chicken breast products are now on the market.

Nonprice factors and trends in meat consumption

Myriad influences other than price and income operate on the consumer’s choice of product. Sometimes these are identifiable and can be quantified. It is the role of market research in most consumer product companies to do exactly this. In other cases, these factors are lumped as an indication of a change in consumer tastes, and often these taste effects work in contrast and are difficult to decompose and measure. Clearly, when patterns of consumption dictate that one form of meat be consumed—e.g., hamburgers on the 4th of July—health issues exert a contrasting influence on meat consumption—e.g., less red meat. However, as the characteristics of meat substitutes (taste, texture, look, feel) become closer to meat, throwing a Beyond or Impossible burger on the grill next to the hamburger becomes more likely. Three important drivers of consumer demand for meat products have evolved: health concerns, environmental and sustainability concerns, and ethical treatment of animal stock.

Consumer health concerns

“Tell me what you eat: I will tell you what you are.” Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, French lawyer, politician, and famed epicure and gastronome; author of The Physiology of Taste (Physiologie du Goût).

Since Brillat-Savarin coined this phrase, it seems to have been applied to several eating motivations ranging from enjoying the good life to eating a healthy diet. In recent colloquial use in the U.S, it morphed into the idiom “You are what you eat,” the title of Victor Lindlahr’s 1940 book and that became a mantra of the 1960’s counterculture. The more contemporary use applies as a proviso to eat less “junk food” and eat healthier. “Healthier” is controversial in and of itself. Toussant-Samat (2013, p. 994) documents a shift from grain products to products of animal origin in developed countries. While consistent with Brillat-Savarin’s dictum for good living, it also led to a greater importance for meat in the consumer diet and in government food policies and budgets.20 However, there is an apparent change in consumer attitudes and buying habits in recent years, similarly reflected in USDA food recommendations. Today, healthier eating corresponds to having less red meat and processed meat in one’s diet because of their linkage in scientific studies to adverse health outcomes (e.g., heart disease).

Environmental and sustainability concerns

An additional reason why some consumers are choosing to eat less meat is due to environmental and sustainability concerns. According to the EPA, methane accounts for 11% of all greenhouse gas emissions resulting from human activities, and 27% of methane comes from enteric fermentation.21 Cattle are the largest agricultural source of greenhouse gases with an estimated 220 pounds of methane belched from a single cow each year.22 Moreover, animal production uses significant amounts of water. According to the National Geographic, it takes 1799 gallons of water to produce one pound of beef.23 For one pound of chicken and pork, the water needs were estimated at 468 and 576 gallons, respectively, while for one pound of soy the value was 216 gallons24 The estimates for meat products consider the water necessary to irrigate the grasses and grain in feed and the water for drinking and processing.25

Concerns about the environment and sustainability seemingly play a role in consumer attitudes toward nonmeat production. The environmental issues associated with meat production of any type are not new. Efforts to reduce methane emissions in cattle production were one motivation to introduce more natural, grass-fed methods and has been so marketed to consumers who are more sensitive environmental issues. From a market perspective, though, sustainability is much less important to the consumer than the taste of the product for all age groups and diet approaches (RBC 2021). Although younger groups express a greater concern about sustainability, producers of alternative meat products do not generally overemphasize the environmental benefits of consuming their products. While there is some controversy about the magnitude of the environmental effects of agricultural production, and that the effects differ by animal produced, concern about these issues plays some role in the perceptions of consumers who buy the products.26

Animal welfare

There is an old saying that “If the walls of the slaughterhouse were made of glass, we would all be vegetarians.” Whether this is a significant driver of consumer demand for nonmeat products is not well documented. To be sure, the humane treatment of animals has come to the public’s attention over the years and apparently intensified somewhat during the more intensive days of Covid-19. Then sanitary conditions in meatpacking as well as worker conditions were magnified and intensively scrutinized with the shutdown of some major production plants. This is often discussed as a concern in some buyer segments, but the effect may not be large enough to induce buyer switching on a major scale.

The market opportunity

Euromonitor reports (https://www.euromonitor.com/choosing-substitutes-the-rising-tide-of-non-animal-proteins/report) that almost half of the respondents to a survey indicate some restriction of animal products—more than half in the U.S.—and that number had grown since Covid-19.27 Hence, the potential methane emissions in cattle production was one motivation is there but currently the market size of plant-based products pales in comparison to the total meat market.

The main challenge is scale. Producers of soy and pea-based products are simply not large enough to fill the potential. The target market for plant-based alternative meats are meat-eating consumers who are willing to substitute away from meat for some portion of their diet. These “flexitarians” comprise the lion’s share of Beyond Meat’s burger products (RBC 2021).28 These estimates are consistent with those reported by Statista (2021) in the U.S. market for 2019, where the retail sales growth of plant-based nonmeat products was reported at 10 percent, while that for animal meat generally was two percent; and by Morach et al (2021), who expect the growth rate for all nonmeat proteins to rise from 2 percent in 2020 to 11 percent in 2035.

Private investment opportunities and ESG investment

Data and analysis from academic research presented here, strategic research (e.g., McKinsey, Boston Consulting Group), and the financial community (e.g., RBC) all suggest that alternative meat products are a growing part of the food landscape and represent growth opportunities for investors in private and public companies, and in ESG opportunities. Indeed, the Certified Financial Analyst association has developed guidelines for evaluating ESG investment opportunities because of the growing interest in these capital projects, which include sustainable agricultural projects, and offers a certificate program in ESG investment analysis.29

Potential barriers to adoption and expansion of alternative meat

Cultural complements: food is culture—culture is food

“While all organisms hunger, only man thinks about it.” (“Foreword” by Betty Fussell in Toussaint-Samat 2009)

“Imagine, for a minute, traveling to a foreign country and exploring that nation’s culture. How might you hope to really understand the people—their traditions, their customs, and the flavors of their cuisine? You might visit museums, walk down city streets, or browse country markets. You would definitely eat the food there, because that is one of the best and often most surprising ways to learn about a different place (O'Connell 2014).” O’Connell, Libby. The American Plate, Sourcebooks; first edition (2014).

What would a 4th of July in the U.S. be without a backyard barbeque of hot dogs and hamburgers on the grill? Is it possible to consider a traditional Thanksgiving dinner without a turkey and all the fixings? Some religious practices require strict specification of the kind of meat and meat preparations used in conforming to the religious dictum. And how could we possibly have a Super Bowl party without chicken wings and beer? Virtually every country and every subculture within each country is identified with food that is germane to its region or religious practices.

The social importance of food is undeniable but, the issue here is, to what extent does the existence of social norms or religious practices—what we call “cultural complements”—affect the entry and expansion of new food products, and particularly new alternative meat products, in the market. Nonmeat products have been commercially available for some time but have not had widespread acceptance by consumers or retail restaurants until the appearance of Impossible and Beyond Meat products. There are two reasons for this. The first relates to cultural complementarity and the second relates to product characteristics and target marketing.

We can think of cultural complementarity as either a form of durable preference attitude or a consumer habit (Phlips 1974). New information about a product’s uses (e.g., recipes) or safety (the effect of saturated fat on heart disease) can influence the consumption of the product over time as information diffuses. The shift from high-carbohydrates to low-carbohydrates/high protein in the consumer diet is another example of information-induced choice with large consequences for the kinds of products supplied in the market. The durability of the existing attitude will diminish with new and more frequently available information, and the quantitative challenge is to measure the speed of depreciation of the old attitude.

Habits like smoking, however, can be hard to break, since current consumption is tied to past consumption, like a stock effect. The consumer lock-in is much stronger and the barrier to new products can difficult. Overcoming these barriers requires a more direct strategy toward increasing the substitutability between the existing product and the new product. In the case of smoking, the challenge is to develop an alternative whose characteristics are close enough to the existing product to induce the consumer to switch over time at some full price, including the health risks of smoking. This is the same challenge or opportunity with alternative meat. The product characteristics must be sufficiently close to induce the meat consumer to switch at some full price, including the reduced risks of heart disease.

As we suggested above, this seems to conform with the product strategies of both Impossible Foods and Beyond Meat. Both firms have developed the capability of producing a very close substitute to low-end meat products (e.g., ground beef) and have targeted product subsegments (e.g., hamburger patties, sausage, chicken nuggets). These are the most price elastic product and consumer segments and therefore there is a greater possibility of continued market expansion. To directly compete with higher cuts of meat will require that nonmeat products are designed to contain the characteristics of those product types. Producing an Impossible New York strip steak may not be impossible, but it may lie beyond current capabilities.

Other potential barriers to alternative meat growth

Product characteristics—taste, texture, perception, and use

By far the most important factor that will enable success for the nonmeat product is that its product characteristics approximate the meat product that it mimics: it must have sufficiently similar taste and texture to meat that will create favorable perceptions by the consumer, who will see it as a substitute in use for the original meat product. For example, if the Impossible burger looks like a burger, feels like a burger, tastes like a burger, and can be grilled like a burger, then it stands a good chance of being bought. If a product misses the mark, it risks failure. The lesson provided by Impossible and Beyond Meat was to delay launching until their products were acceptable in each of the relevant channels.

Scale limitations and price

The issue that haunts existing nonmeat producers and startups alike is scale. Even Impossible and Beyond Meat have reported some delays in delivery to retail grocery channels because of limits to production capacity.

Potential future competitive threat from cell based

The wild card in the nonmeat market is cellular. Since cell-based products are produced from the stem cells of animals, they are meat and, therefore, have the greatest chance to replicate the characteristics of the meat products that they intend to replace. Cellular can be a bigger disruption to meat production than plant-based products and could provide a threat to plant-based market shares. However, the technology is in its infancy and not close to any mass production.

Beyond “beyond meat”: the future of meat alternatives

“Whiskey, Steak, Guns” was the message on the woman’s tee shirt seen by one of the authors.

“They want to take your hamburger away!” warned Sebastian Gorka at the 2019 CPAC convention.

Make of this cultural-political symbolism what you will, but have no fear, meat—beef, pork, poultry, and prepared—is here to stay in the American diet. No one is likely to “take your hamburger away,” however, you may choose to eat a hamburger made with an alternative meat if you desire. What market and economic research suggest is that consumer preferences toward meat have been changing in a systematic way for some time now. Indeed, culture plays a prominent role in food choice and self-identification, or as Donnan and Kirchner (2019) describe: “Where we used to define our food legacy by our culture and heritage, we are now seeing people create their own food tribes based on diet trends and like-minded shopping behaviors and choices that consumers believe express who they are. Keto and kale culture? Yes. From fashion to food to following on social media, trends in food and nutrition are becoming embedded as guiding stars for their dedicated followers.”

This paper has identified several observations about consumer choices.

Consumers have been shifting expenditures away from beef and toward poultry for decades in response to health concerns about saturated fats and heart disease.

Consumers are increasingly demanding products—meat or otherwise—that are produced using sustainable methods of production. Producers have responded by promoting “green” actions to differentiate themselves from “non-green” producers.

Consumers have raised concerns about the inhumane treatment of animals for slaughter and have adjusted their meat-buying habits among brands. Producers of major brands (e.g., Costco, Purdue) have acted in their own interests to adjust production methods to allay consumer concerns in an effort to sustain market share.

Consumers are price sensitive to changes in the relative price of meat. In particular, as beef prices have risen relative to other meat prices, consumers have switched consumption away from beef and toward other meats, especially poultry.

Consumers have become increasingly interested in adding plant-forward products to their diets, either as substitutes for meat or as supplements to their food budgets. Cohorts born in the last 20 years, and younger consumers generally, have demonstrated a propensity toward less meat, and poultry in favor of beef and pork.

Consumer adoption of nonmeat alternatives and plant-forward food in general is growing like, and perhaps as an extension of, the proliferation of organic foods over the last decade.

What is telling about these results is, that it is the market that is moving trends in meat and alternative meat expenditures. We argue that consumer demand is inducing producer responses in production and distribution. Moreover, as price differentials between meat and alternative meat products diminish, increased sampling and adoption will surely follow. While Impossible and Beyond Meat have lowered prices over competitive with meat products, they are still priced ata premium. Overcoming supply chain challenges, scaling production, and expanding distribution should close the price gap further.

Although we recognize the old dictum that “anecdotes are not data,” the graphics in the ad below are telling.

The ad in Fig. 6 is from a major, national high-end steak franchise, Fleming’s Prime Steakhouse and Wine Bar. Fleming’s expects to expand its patronage to nonmeat-eating consumers, who might come to their restaurants because of the plant-forward menu, or because they are companions to others who are meat eaters.

Fig. 6.

Plant-forward comes to the steakhouse

Prospective industry structure

We reviewed the most salient factors driving the market for alternative meat products, mainly from the perspective of the consumer. We now consider how vertically integrated, multi-product traditional meat producers might react to domestic and global growth in an adjacent sector, and how those reactions might impact the industrial structure of a wider market. We frame the analysis by looking prospectively at the strategic options available to the industry players and evaluate the likely outcomes that we believe will result.

The technologies to produce plant-based products, whether soy based, or vegetable based, already exist. The newest branded products, most notably those of Impossible and Beyond, are becoming almost identical to meat in all forms. Successful entry into this submarket by incumbent meat producers will require them to match the quality of the existing brands. This outcome will require investment in research and development (R&D), product testing and development, and marketing. While the current alternative meat brands have a head start, their producers lack the scale to drive costs and price points down to meat levels. If an existing meat producer with a well-known brand were able to successfully develop a differentiated product, it might be able to expand market share fairly rapidly given its substantial scale in production and distribution.

Ventures into the nascent cell-based, or cultured meat space, will entail a much different path that will require higher levels of near-term investment in R&D to develop new cultured meat products for a potential market that is not immediately available. However, this submarket is moving rapidly. In 2020 Memphis Meats, a cell-based startup, raised $161 million is Series B funding in 2021 Memphis Meats became Upside Foods and raised an additional $400 million in Series C funding, and in April 2022, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) evaluated Upside’s chicken product and issued a No Questions letter permitting the safe consumption of the product. In December 2022, Believer Meats, an Israeli company originally known as Future Meat Technologies, broke ground on a $123 million, 200,000 square-foot, factory in Wilson, North Carolina that will have a production capacity of 10,000 metric tons (Ramirez 2022a, b). Cultured meat is a longer run proposition but there is less risk in mimicking actual meat products, and therefore substantial upside potential. If production scale drives prices toward competitive price meat producers would avoid costly investments points, the market for cell-based products will be wider and will likely grab the flexitarian share from plant-based brands.

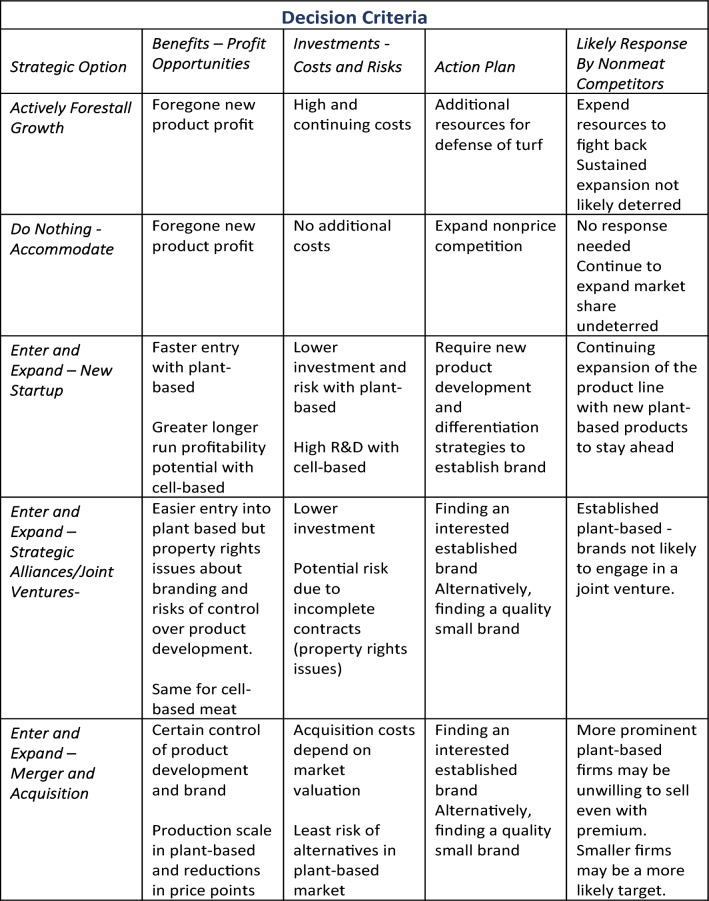

Given the recent technological advancements in believe the same alternative meat products and consumer acceptance of products offered by new market entrants, we consider three broad, strategic options available to the large incumbent meat processing firms and food conglomerates: Actively Forestall Growth, Do Nothing, and Enter and Expand.30

Actively forestall growth

Strategies to deter nonmeat products from expansion include actions that would effectively raise the costs of nonmeat producers to expand existing products or to develop new products. Some of these have already been observed early in the launch of nonmeat products, including regulatory restrictions, negative advertising, and disinformation on social media platforms.

Assessment

We argue that this is a fruitless pursuit because the trend favors the development of and growth in alternative meat products. Meat producers would forego opportunities to participate in the nonmeat market, and fighting growth in nonmeat products would be costly.

Do nothing

This strategy is a passive acquiescence to the continued expansion of alternative meat producers. The industry attitude here is that the new, nonmeat products are trendy but would not last. Beyond and Impossible may be growing but their penetration in the total market defined by all meat products is small and likely to stay small, just as with other plant-based products of the past. Resources invested in forestalling nonmeat growth would be better allocated toward core meat product lines.

Assessment

Pursuing this strategy rests on the assumption that the nonmeat market is small, and that growth is capped. Although meat producers would avoid costly investments in deterring nonmeat growth, they would also forego any opportunities to participate in the nonmeat space. We believe that this would be a costly mistake, and that the large firms in the meat industry believe the same.

Enter and expand

Entry into the nonmeat market yields new product revenues and profit streams that would otherwise be foregone, so why ignore that potential? The early strategy of "wait-and- see" is over as the plant-based alternatives are here to stay. The attitude here is, “if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em.” The question is how? Large incumbent meat producers have a number of potential competitive advantages in the production and distribution of new nonmeat products. They have ample capital to finance innovation and new production; they have existing production facilities and food distribution networks in place; and they have recognizable brands that enhance consumer trust and loyalty to new products. Entry and expansion subsume three specific strategies that vary by type of product.

One option is for an incumbent meat producer to invest in wholly-owned nonmeat R&D, new product development, including consumer testing and marketing, and in new production facilities. The technology for plant-based products would be easier to acquire than for cultured meat, and the cost of developing plant-based products more certain. Hence, entry into the plant-based space would be faster to develop and, with a well-recognized brand, yield returns sooner, but lower, than pursuing a cultured meat path. Because of scale in production and distribution, an incumbent meat producer should be able to expand share readily. This is far from a risk-free venture since its branded portfolio would be competing against established plant-based brands. Should the market not grow as expected, it would be one of several brands competing in the plant-based space.

One way to avoid the burden of the entire cost of product development in either plant-based or cell-based submarkets is to engage in a strategic alliance or a joint venture with an existing nonmeat firm. Ideally, a prominent, branded company like Beyond Meat would find value in exchanging product technology for production and marketing scale. However, these kinds of arrangements are typically most useful in producing a specific product over a certain term, and it is not clear how benefits would extend to either an incumbent meat producer or the partnering nonmeat producer. Indeed, there is some risk in defining outcomes, or control over product development would arise (i.e., incomplete contracts). A partnering arrangement might be more appealing with a cell-based venture but the property rights issues in product development and ownership would be equally uncertain.

We believe the more likely strategy for an incumbent meat producer is through mergers and acquisitions. Common ownership would yield financial capital, production scale, and marketing scale for nonmeat producers, which would expand share and lower price points. Acquiring meat producers would benefit by immediate entry into the alternative meat space with an expanded product portfolio. This outcome is akin to Coca-Cola buying Honest Tea.

The evaluation framework can be envisioned in the Fig. 7—Strategy Evaluation below that links each strategic option to qualitative measures of benefits, costs, actions, and competitive responses.

Fig. 7.

Strategy evaluation

Conclusions and implications for the industry

The nonmeat market is developing very quickly. Based on current developments in consumer markets, and likely strategies on the part of existing meat producers, we can expect:

Further expansion of private capital investment and greenfield investment into plant-based and cell-based product development to tap the multibillion-dollar market in the U.S. and globally.

A proliferation of branded alternative meat products, some under common, vertically integrated ownership including new firms (e.g., Impossible, Beyond Meat), incumbent meat producers (e.g., Tyson) and other food conglomerates (e.g., Kellogg, Cargill), and niche producers. We expect mergers and acquisitions to be the strategy of choice for existing meat producers and nonmeat producers, resulting in somewhat greater industry concentration.

New growth opportunities for ESG projects in the production of alternative meat and in more efficient uses of land and water resources in the production of meat, particularly in developing countries where protein demand is strong and agricultural resources limited.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the anonymous referees for comments and suggestions that resulted in an improved paper.

Biographies

Christopher Swann

is an Assistant Professor of Economics at Temple University, Philadelphia, PA. where he teaches courses in macroeconomics, managerial economics, and the senior capstone writing course. His career has spanned telecommunications (Bell Atlantic/Verizon), macroeconometric forecasting and consulting (WEFA/Global Insight), and regional economic development (Greater Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce). He served on the Board of Directors of National Association for Business Economics (NABE) from 2005 to 2008. While on the Board, he spearheaded the “Get Connected,” outreach program, and later participated in teams that developed the Certified Business Economist (CBE) program. He is currently a member of the editorial board of Business Economics and was recently (2021) elected to be a NABE Fellow. He is a past Chair of the NABE Technology Roundtable and is a past President of the Philadelphia Council for Business Economics. He received both his Ph. D and M.A. in economics from Temple University and his B.A. in Economics from Washington University in St. Louis.

Mary Kelly

is the Associate Chair of Villanova University’s Economics Department and teaching professor of economics where she develops and teaches undergraduate courses in economics both in the classroom and for online delivery. In addition to her teaching responsibilities, Dr. Kelly conducts applied research in the areas of industrial organization and labor. Prior to joining the Villanova faculty full time in 2002, Dr. Kelly worked for Verizon Corporation for nearly 14 years. During her time at Verizon, she held numerous management positions in product development and marketing, information services, and regulation. Dr. Kelly earned a PhD in Economics from the University of Delaware, and a BS in Economics from Villanova University.

Appendix: authors’ estimates of product elasticities

Purpose and scope

Using data from the Bureau of Economic analysis on meat consumption and prices by product, we sought to estimate price and cross-price elasticities to see whether estimates using aggregate data would yield any consistencies with those derived from microdata that are cited in the paper. Elasticities measure consumer demand response and substitution with respect to product price changes and are important in the context of alternative meat introduction since those product introductions are squarely aimed at lower-end, mass-market meat products such as hamburger, pork sausage, and chicken. Major results from the microdata studies suggest that beef products are very price elastic and that consumers are willing to substitute other meat products readily. Although we cannot estimate important impacts by cohort as in Lee et al. (2020), we had hoped to gain some comparisons of demand response broadly. Specifically, we ask (1) how price elastic are the products and how do the elasticities compare across products, and (2) can cross-elasticities be estimated and are they symmetric?

Model and estimation methodology

The meat industry is defined by four major categories: beef, pork, poultry, and other processed products. In this paper, we reviewed literature that estimates demand for these products using several methods and specifications. Roosen et al. (2022) specifies an expenditure equation following Deaton and Muellbauer (1980) in which

Here, is the expenditure share of meat group i (poultry, pork, beef and veal, mixtures) for a household, h, in period t. The price term, , is the real price of a product group j (accounting for own and cross-price effects) and represents a household’s total meat expenditures in real terms. The other terms are parameters to be estimated and is the error term.

We specified a similar system of expenditure equations for meat products using aggregate BEA data to expressly estimate price, cross-price, and expenditure elasticities. Our primary purpose was to see how price, cross-price, and expenditure elasticities estimated with aggregate expenditure data compared to those measured using pooled estimates over individuals. We specified two systems of expenditure equations. The first specifies meat demand as follows:

where i indicates each of the four meat products, beef, pork, other, and poultry respectively. Demand for each product, is measured by deflating each product’s expenditure by its own-price index, taken from the BEA underlying detail for consumer expenditure, yielding a measure of quasi-quantity. The relative price for each product, , is determined by dividing each product’s price index by the PCE price index. The term, , is total real expenditure on all meat products, i.e., total nominal expenditures divided by the PCE price index. The final term is the error term associated with each product equation. The second equation specifies the dependent variable as meat demand per capita:

The system of four equations specifies product demand as a function of own-price effects and cross-price effects with respect to each of the other products. The real expenditure term measures the impact of additional spending on all meat products on a particular product and is in some sense a proxy for an income effect.

The error term is specified as if it followed the assumed rules of Ordinary Least Squares (OLS). However, because there are myriad, unobservable influences on cross-product substitution (including health, tastes, etc.), the error terms are likely to be correlated across equations resulting in biased and inefficient estimators. We estimated the system using a standard two-stage process. We first estimated each of the equations using Ordinary Least Squares and then estimated the system of equations applying the Seemingly Unrelated Regression (SUR) methodology.

Main findings and implications

We estimated both demand and demand per capita as specified above. Table 4 exhibits a table of elasticities and cross-elasticities for quantity demanded and Table 5 shows the same for demand per capita. In both models the own-price elasticities are the correct sign and statistically significant. The own elasticity for beef is greater than other products in absolute value, irrespective of demand definition. This is consistent with microstudies reported here.

Table 4.

Table of elasticities with SUR estimation (t-statistics in parentheses)

| Meat demand | Percentage price change in: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage change in demand for: | Beef | Pork | Other | Poultry | Expenditure |

| Beef | −1.396 | −0.214 | 1.954 | 0.626 | 0.601 |

| t-statistics | −5.457 | −0.612 | 4.477 | 3.203 | 2.661 |

| Pork | 0.441 | −0.752 | 0.241 | −0.887 | 0.330 |

| t-statistics | 3.050 | −3.810 | 0.978 | −8.043 | 2.582 |

| Other | 0.219 | 0.063 | −2.260 | 0.227 | 1.431 |

| t-statistics | 1.011 | 0.212 | −6.107 | 1.372 | 7.466 |

| Poultry | 0.406 | 0.326 | −2.184 | −2.116 | 1.465 |

| t-statistics | 1.263 | 0.744 | −3.986 | −8.631 | 5.162 |

Table 5.

Table of elasticities with SUR estimation (t-statistics in parentheses)

| Meat demand per capita | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage change in Demand per capita for: | Percentage price change in: | ||||

| Beef | Pork | Other | Poultry | Expenditure | |

| Beef | −1.703 | −0.374 | 2.827 | 1.070 | 0.155 |

| t-statistics | −4.946 | −0.795 | 4.812 | 4.068 | 0.509 |

| Pork | 0.133 | −0.912 | 1.114 | −0.443 | −0.117 |

| t-statistics | 0.694 | −3.483 | 3.406 | −3.028 | −0.690 |

| Other | −0.088 | −0.098 | −1.387 | 0.671 | 0.984 |

| t-statistics | −0.551 | −0.446 | −5.079 | 5.492 | 6.961 |

| Poultry | 0.098 | 0.166 | −1.311 | −1.672 | 1.018 |

| t-statistics | 0.404 | 0.499 | −3.159 | −9.006 | 4.738 |

Table 4 displays the coefficients from the first meat demand model. Since the models are specified in log–log form, the coefficients are the elasticities. The Table indicates that other meat products and poultry are substitutes for beef; a 1 percent decrease in other meat products prices reduces beef demand by 2.8 percent and a 1 percent cut in poultry prices reduces beef demand by 1 percent.

Table 5 shows qualitatively the same results when meat demand is measured on a per capita basis. Pork demand is unaffected by beef prices but seen to be complementary to poultry in either specification. On a per capita basis, other meat product prices are substitutes for pork. There is an unusual asymmetry between other meat products and poultry. Table 4 shows that a 1 percent drop in poultry prices will result in a decrease in other meat product demand; however, a decrease in other meat prices leads to a 1.3% increase in poultry demand.

The expenditure variable measures the impact of a 1 percent increase in total meat expenditure on product demand, respectively. Table 4 estimates indicate that for a given percentage increase in total consumer expenditures for meat, beef and pork take smaller shares than do other meat products and poultry. When demand is measured as per capita demand, Table 5 shows that beef and pork increases are not statistically significant. These results are somewhat different than those of Lusk and Tonsor (2016) who report that beef can be viewed as a luxury good and that as income increases, beef demand increases more than proportionally. Our results may be qualitatively different since these expenditure elasticities are not exactly income elasticities.

The model statistics for each estimated equation—demand and demand per capita—are shown below in Tables 6 and 7, respectively.

Table 6.

Estimation statistics: meat product demand system methodology: seemingly unrelated regression

| Sample: 1959–2021 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Included observations: 63 | |||||||

| Total system (balanced) observations 252 | |||||||

| Beef | Pork | Other | Poultry | ||||

| Observations: 63 | Observations: 63 | Observations: 63 | Observations: 63 | ||||

| R-squared | 0.793 | R-squared | 0.955 | R-squared | 0.921 | R-squared | 0.9646 |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.775 | Adjusted R-squared | 0.951 | Adjusted R-squared | 0.914 | Adjusted R-squared | 0.9615 |

| S.E. of regression | 0.108 | S.E. of regression | 0.061 | S.E. of regression | 0.092 | S.E. of regression | 0.1356 |

| Durbin-Watson stat | 0.447 | Durbin-Watson stat | 0.720 | Durbin-Watson stat | 0.224 | Durbin-Watson stat | 0.7199 |

| Mean dependent var | 10.869 | Mean dependent var | 10.040 | Mean dependent var | 9.899 | Mean dependent var | 10.1127 |

| S.D. dependent var | 0.228 | S.D. dependent var | 0.274 | S.D. dependent var | 0.312 | S.D. dependent var | 0.6909 |

| Sum squared resid | 0.665 | Sum squared resid | 0.212 | Sum squared resid | 0.478 | Sum squared resid | 1.0480 |

Table 7.

Estimation statistics: meat product demand per capita system methodology: seemingly unrelated regression

| Sample: 1959–2021 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Included observations: 63 | |||||||

| Total system (balanced) observations 252 | |||||||

| Beef | Pork | Other | Poultry | ||||

| Observations: 63 | Observations: 63 | Observations: 63 | Observations: 63 | ||||

| R-squared | 0.877 | R-squared | 0.620 | R-squared | 0.807 | R-squared | 0.962 |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.866 | Adjusted R-squared | 0.587 | Adjusted R-squared | 0.790 | Adjusted R-squared | 0.959 |

| S.E. of regression | 0.145 | S.E. of regression | 0.081 | S.E. of regression | 0.068 | S.E. of regression | 0.103 |

| Durbin-Watson stat | 0.457 | Durbin-Watson stat | 0.324 | Durbin-Watson stat | 0.431 | Durbin-Watson stat | 0.796 |

| Mean dependent var | −1.565 | Mean dependent var | −2.393 | Mean dependent var | −2.535 | Mean dependent var | −2.321 |

| S.D. dependent var | 0.398 | S.D. dependent var | 0.126 | S.D. dependent var | 0.148 | S.D. dependent var | 0.508 |

| Sum squared resid | 1.205 | Sum squared resid | 0.374 | Sum squared resid | 0.260 | Sum squared resid | 0.601 |

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), Underlying Detail tables, Personal Consumption Expenditures by Type of Product, February 2022 at www.bea.gov. The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings in the Appendix are available directly from BEA or from the authors upon request.

Footnotes

The industry is more precisely defined in the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) by the four-firm NAICS code 3116, Animal slaughtering and processing.

The CR4 is 85 in beef, 70 in pork, and 54 in poultry. See https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/01/03/fact-sheet-the-biden-harris-action-plan-for-a-fairer-more-competitive-and-more-resilient-meat-and-poultry-supply-chain/

Meat-eating consumers, who are open to, or actually purchase, alternative meat products are often referred to as “flexitarians” in the press and formal literature.

There are other protein sources used in developing nonmeat foods including whey protein, algae and insects, but we ignore these.

Upside Foods is an example of a cell-based producer. It reports that it expects to decrease the cost of lab-grown meat in order to compete with commercial meat. Its original meat reportedly cost $18,000 a pound but by January 2018 costs were cut to $2400 per pound (RBC (2021)).

Superior packaging includes labeling, wrapping, and shipping using sustainable materials.

See https://www.usfoods.com/why-us-foods/local-sustainable-wellbeing/well-being/plant-based-alternatives.html and https://www.aramark.com/insights-stories/blog/unpacking-the-popularity-of-plant-forward.

See https://www.bnnbloomberg.ca/a-former-steakhouse-chef-wants-to-beat-beyond-meat-at-plant-based-food-1.1766325; and https://www.restaurant-hospitality.com/food-trends/chefs-develop-their-own-plant-based-burgers-without-processing.

Real PCE items were calculated by deflating current dollar PCE by the relevant PCE price index.

Specifically, a decrease in the price of chicken breasts results in a much larger reduction in steak demand than does a similar reduction in ground beef price. Since higher-income consumers are more likely to buy steak and chicken breast than hamburger, a good deal of this demand response happens among high-income consumers. This also contributes to the explanation of the shift from beef to chicken that we observe over the last three decades.

A History of Food, Toussaint-Samat, Maguelonne, p. 994.

Donnan and Kirshher (2019) estimate that only 37% of agricultural production is directed toward consumer ends; the balance goes to animal production.

Also, Grand View Research assesses the global nonmeat market to be $5.0 billion currently and expected to grow at just under 20 percent a year over the next decade, with U.S. growth slightly lower.

These firms include Perdue, Tyson, Hormel, Kellogg’s, and Kraft.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

3/6/2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1057/s11369-023-00309-3

References

- Chandler, Adam. 2019. Drive-thru Dreams: A Journey Through the Heart of America’s Fast-Food Kingdom. New York: Flatiron Books.

- Deaton, Angus S., and John Muellbauer. 1980. An almost ideal demand system. American Economic Review 70: 312–336.

- Donnan, Dave and Kirchher, Kim. 2022. We eat what we are. A.T. Kearney.

- Lee, Ji Yong., Yiwei Quia, Geir Wæhler Gustavsen, Rudolfo M. Nayga Jr., and Kyrre Rickertsen. 2020. Effects of consumer cohorts and age on meat expenditures in the United States. Agricultural Economics 51: 505–517.

- Lindlahr, Victor. 1940. You are what you eat. New York City: National Nutritions Society Incorporated.

- Lusk Jayson L, Tonsor Glynn T. How meat demand elasticities vary with price, income, and product category. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy. 2016;38(4):673–711. doi: 10.1093/aepp/ppv050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McKinsey and Company. 2019. The future of food: Meatless. October.

- Morach, Benjamin, Björn Witte, Decker Walker, Elfrun von Koeller, Friederike Grosse-Holz, Jürgen Rogg, Michael Brigl, Nico Dehnert, Przemek Obloj, Sedef Koktenturk, and Ulrik Schulze. 2019. Food for Thought: The Protein Transformation. Boston Consuting Group and Blue Horizon.

- O’Connell, Libby. 2014. The American Plate: A Culinary History in 100 Bites. New York: Sourcebooks.

- Phlips, Louis. 1974. Applied Consumption Analysis. Elsevier.

- Ramirez, Vanessa Bates. 2022a. In an industry first, upside foods’ lab-grown chicken gets FDA approval. November 17. https://singularityhub.com/2022/11/17/in-an-industry-first-upside-foods-lab-grown-chicken-gets-fda-approval/

- Ramirez, Vanessa Bates. 2022b. The world’s biggest cultured meat factory is under construction in the US. December 14. https://singularityhub.com/2022/12/14/the-worlds-biggest-cultured-meat-factory-is-now-under-construction-in-the-us/

- Renner, Barb, Justin Cook, and Dillon Wiesner. 2021. A new direct-to-consumer opportunity? Meat and seafood consumption trends during the Covid-19 pandemic. The Deloitte Consumer Industry Center, January.

- Roosen, Jutta, Matthias Staugdigel, and Sebastian Rahbauer. 2022. Demand elasticities for fresh meat and welfare effects of meat taxes in Germany. Food Policy 106.

- Schumpeter, Joseph. 1942. Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy. New York: Harper and Brothers.

- Statista. 2020. Meat substitutes market in the U.S.

- Stone, J.R.N. 1954. Linear expenditure systems and demand analysis: an Application to the Pattern of British Demand. Economic Journal 64: 511–527.

- Toussaint-Samat Maguelonne. A history of food. Wiley-Blackwell; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, J. Richard N., 1954 Linear expenditure systems and demand analysis: an Application to the Pattern of British Demand. Economic Journal 64: 511-527.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), Underlying Detail tables, Personal Consumption Expenditures by Type of Product, February 2022 at www.bea.gov. The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings in the Appendix are available directly from BEA or from the authors upon request.