Abstract

Background:

Asthma is a chronic lung disease that affected 5 million children. Allergy is a common comorbidity of asthma. Having both conditions is associated with unfavorable health outcomes and impaired quality of life.

Objective:

Purpose of this study was to assess allergy and its association with asthma by select characteristics among children to determine differences by populations.

Methods:

National Health Interview Survey data (2007–2018) were used to assess asthma and allergy status, trends, the association between allergy and asthma by select characteristics among U.S. children (aged 0–17 years).

Results:

Prevalence of asthma decreased among all children (slope(−) p<0.001) and among those with allergy (slope(−) p=0.002). More children had respiratory allergy (14.7%), followed by skin allergy (12.7%) and food allergy (6.4%). Prevalence of respiratory allergy significantly decreased among White non-Hispanic children, food allergy increased among White non-Hispanic and Hispanic children, and skin allergy increased among Hispanic children.

Depending on number and type, children with allergy were 2 to 8 times (skin allergy only and having all three allergies, respectively) more likely to have current asthma than were children without allergy. Among children with current asthma, having any allergy was significantly associated with missed school days (adjusted prevalence ratio [aPR]: 1.33[1.03, 1.72]) and taking preventive medication daily (aPR: 1.89[1.32, 2.71]).

Conclusion:

Trends in allergies across years differed by race and ethnicity. Strength of association between asthma and allergy differed by type and number of allergies, being highest among children having all three types of allergies. Having both asthma and allergy was associated with unfavorable asthma outcomes.

Keywords: Survey research, pediatrics, respiratory diseases, disparities, health outcomes, trends

Introduction

Asthma is a chronic lung disease requiring complex medical management.1 Approximately 5 million children (7.0% of the population) had current asthma in 2019.2 Allergic asthma is a common asthma phenotype3 with nearly 60% of children with current asthma having reported of any allergy.4 Recent studies note the importance of epidermal barrier impairment in allergic sensitization and the progression from eczema to asthma.5–7 They determined that from 2001 to 2013, the prevalence of food and skin allergy among children with asthma increased and respiratory allergy decreased. Increases in allergic disease prevalence have been attributed to environmental exposures and changes in gene expression.8,9

Asthma, allergic rhinitis (hay fever), eczema, and food allergies are common atopic diseases. Children with one of the atopic diseases are more likely to develop another.10 Airway remodeling occurring in hay fever may influence clinical expression of asthma.11 A strong association exists between food allergy and asthma, with food sensitization in infants increasing the risk of developing asthma.5 Asthma outcomes may also be worse for children with allergies. Children with coexisting atopic conditions are at greater risk for unfavorable health outcomes among children with asthma5,12,13 and challenges in disease management at school.5 Licari et al14 documented that allergic rhinitis is a risk factor for severe asthma, which may lead to poor asthma control.11 Uncontrolled asthma and emergency department or urgent care center visits have been associated with school absenteeism.15 Having coexisting atopic conditions can negatively affect a person’s quality of life in various ways, in areas ranging from social interactions to food types to avoid.16

This study contributes to the existing literature on asthma and allergy among children (aged 0–17 years) through an analysis of the most recent National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data (2007–2018). We assessed trends in prevalence of asthma and allergy and the association between allergy and asthma by select characteristics among U.S. children (aged 0–17 years) with the following objectives: to examine if asthma and allergy were more common among certain demographic and socioeconomic groups; if the association between allergy and asthma differed by type and number of allergy (i.e., respiratory allergy, skin allergy, and food allergy); and if having allergy was associated with unfavorable health outcomes among children with asthma.

Methods

Survey Data Description

The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) is an annual, cross-sectional, household health survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics that covers a broad range of health topics since 1957. NHIS is the nation’s largest household and longest running survey on the nation’s health. The survey targets the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population residing in the 50 states and District of Columbia.17 A “sample child” was randomly selected from each family with children, and a knowledgeable adult proxy responded to survey questions for the child. The final response rate in 2018 was 59.2% for children.17 This study analyzed annual NHIS data from 2007–2018 to assess annual trends in the prevalence of allergy (i.e., any allergy, respiratory allergy, skin allergy, and food allergy), 4 allergy types by race and ethnicity, and current asthma by 4 allergy types and race and ethnicity among U.S. children aged 0–17 years. NHIS data from 3 years (2016–2018) were combined to increase sample size for reliable estimates of asthma and allergies by characteristics, and associations between asthma and allergies (4 and 8 allergy groups). Expanded content from the 2018 NHIS periodic asthma supplementary questions, including missed school days, asthma-related hospitalization, and use of quick relief and preventive asthma medications, were used to assess if having allergy affected these outcomes among children with asthma. This study was exempt from CDC Institutional Review Board review because it only involves secondary data analysis of de-identified public-use data files.

Survey Data Variables

Survey question responses were self-reported by knowledgeable adult proxy (e.g., parent or guardian). A child was considered to have current asthma if a “yes” response was given to the questions “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that [child’s name] had asthma?” and “Does [child’s name] still have asthma?” A child with current asthma who experienced an asthma attack in the past 12 months was counted as having an asthma attack. A child with current asthma who had an emergency department or urgent care center visit in the past 12 months for asthma was defined as having had an emergency department or urgent care center visit because of asthma.

The 4 allergy types were determined by “yes” responses to the following child NHIS questions:

During the past 12 months, has child had any of the following conditions:

Hay fever

Any kind of respiratory allergy

Any kind of food or digestive allergy

Eczema or any kind of skin allergy

The survey asks two questions to capture all upper respiratory allergy (i.e., hay fever and any kind of respiratory allergy). For the analysis we combined responses to these two questions into “respiratory allergy.” The final 4 allergy types for analysis included any allergy (i.e., having had hay fever, respiratory allergy, skin allergy, or food allergy in the past 12 months), respiratory allergy (i.e., having had hay fever or any respiratory allergy), skin allergy, or food allergy. A detailed allergy grouping with 8 combinations (i.e., all 3 allergies, respiratory and skin allergy, respiratory and food allergy, food and skin allergy, respiratory allergy only, skin allergy only, food allergy only, or no allergy) was created using the responses to the allergy questions.

The 2018 NHIS asthma supplemental question data were used to assess the effects of having allergies on the following asthma indicators: missed school days, medication use, and asthma-related hospitalization. Missed school days were determined if a child aged 5–17 years has missed 1 or more school days in the past 12 months. Medication use was specified by two questions: one for use of a prescription quick relief inhaler for asthma symptoms in the past 3 months, and the other if preventative asthma medication was used every day or almost every day. Asthma-related hospitalization was defined as staying overnight in the hospital because of asthma in the past 12 months.

Study variables were defined using the following categories. Demographic variables included age group (0–4 years, 5–11 years, and 12–17 years), sex (male or female), 6 detailed racial and ethnic groups (non-Hispanic White [White], non-Hispanic Black [Black], non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native [AI/AN], non-Hispanic Asian [Asian], non-Hispanic multiracial [multiracial], and Hispanic), 4 racial and ethnic groups (White, Black, non-Hispanic other [other], and Hispanic), ethnicity subgroup (Puerto Rican, Mexican, and other Hispanic). The other category in the four-subgroup race and ethnicity variable includes AI/AN, Asian, and multiracial. Family income was also calculated using 5 publicly available, imputed income files as the ratio of income to poverty categorized into 4 federal poverty levels (FPLs): <100% FPL, 100% to <250% FPL, 250% to <450% FPL, and ≥450% FPL. The U.S. Census Bureau’s federal poverty threshold is based on family income and family size. The geographic variable includes U.S. Census region, with subgroups: Northeast, Midwest, South, and West.

Statistical Analysis

Trends in prevalence of allergies, allergies by race and ethnicity, and current asthma by allergy and race and ethnicity were assessed using annual NHIS data from 2007–2018.

We used multivariable logistic regression models to assess associations between dependent and independent variables (e.g., between current asthma and any allergy, between current asthma and each allergy [respiratory, skin, or food allergy], and between current asthma and 8-level allergy group by adjusting for age, sex, race, and ethnicity). We also assessed whether having allergy was associated with medication use and asthma-related outcomes (i.e., asthma attack, missed school days, medication use, emergency department or urgent care center visit, or hospitalization) among children with asthma. Unadjusted prevalence ratios (PR) and adjusted prevalence ratios (aPR) (adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity) were calculated with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). CIs not containing null value of 1 were considered statistically significant. Relative standard error values were determined for each prevalence estimate, defined as standard error divided by prevalence estimate, as a measure of an estimate’s reliability. A value below 0.30 indicates a reliable estimate.

Chi-square tests (Wald test statistic χ2) were conducted to determine associations between characteristics and prevalence of asthma and allergies, and two-sided significance tests were conducted to determine subgroup differences. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05 for these statistical tests. Throughout the paper, stating that the value of an outcome for a variable category was higher or lower than another category indicates the results of a two-sided statistical test (t-test or z-test), where applicable. Sample weights were used to adjust for nonresponse, poststratification, and probability of selection.17,18,19 To account for the survey’s complex sample design, estimates of prevalence, standard errors, and prevalence ratios were calculated using SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute) and SAS-callable SUDAAN (version 11.0.1; Research Triangle Institute). Joinpoint statistical software (version 4.9.0.0; National Cancer Institute)20 was used to determine the statistical significance of trends using Joinpoint regression. The Joinpoint software calculates the fewest number of linear segments necessary to characterize a trend and the year(s) where two segments with different slopes meet. Model-based (trend line) and observed prevalence estimates (dots) were plotted in the figures.

Results

Approximately 26.4% of U.S. children aged 0–17 years had one or more allergies (any allergy) (Table 1). Prevalence of current asthma was 8.1% (Table 2) among all U.S. children aged 0–17 years and 18.1% (Table 1) among U.S. children who had allergy. The most reported type of allergy was respiratory (i.e., hay fever or other respiratory allergies) (14.7%), followed by skin allergy (12.7%) and food allergy (6.4%) (Table 1). Of U.S. children, 1.1% had all 3 types of allergies, 2.7% had respiratory and skin allergies, 1.3% had respiratory and food allergies, 1.2% had food and skin allergies, 9.6% had only respiratory allergy, 7.7% had only skin allergy, and 2.8% had only food allergy (Table 1).

Table 1.

Association between having current asthma and type of allergy, 2016–2018

| All child (0–17 years) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Prevalence of allergy | Prevalence and aPR for current asthma | |||||

|

|

||||||

| Allergy types | Sample size n | % (95% CI) |

Sample size n | Prev, % (95% CI) |

Unadjusted PR (95% CI) |

aPR (95% CI) |

|

| ||||||

| Any allergy | ||||||

| Yes | 7930 | 26.4 (25.7, 27.2) |

1382 | 18.1 (17.0, 19.3) |

4.02

(3.62, 4.46) |

3.86

(3.48, 4.28) |

| No | 20 283 | 73.6 (72.8, 74.3) |

936 | 4.5 (4.1, 4.9) |

Ref | Ref |

| Individual allergy type | ||||||

| Respiratory allergy | ||||||

| Yes | 4542 | 14.7 (14.1, 15.3) |

1037 | 23.8 (22.3, 25.4) |

4.40

(4.00, 4.83) |

3.47

(3.14, 3.84) |

| No | 23 663 | 85.3 (84.7, 85.9) |

1279 | 5.4 (5.0, 5.8) |

Ref | Ref |

| Skin allergy | ||||||

| Yes | 3723 | 12.7 (12.2, 13.3) |

634 | 17.4 (15.8, 19.1) |

2.57

(2.30, 2.87) |

1.79

(1.59, 2.02) |

| No | 24 472 | 87.3 (86.7, 87.8) |

1684 | 6.8 (6.3, 7.2) |

Ref | Ref |

| Food allergy | ||||||

| Yes | 1870 | 6.4 (6.0, 6.7) |

362 | 19.9 (17.6, 22.5) |

2.73

(2.40, 3.11) |

1.67

(1.42, 1.96) |

| No | 26 315 | 93.6 (93.3, 94.0) |

1953 | 7.3 (6.9, 7.7) |

Ref | Ref |

| 8-level allergy group | ||||||

| All 3 allergies | 320 | 1.1 (0.9, 1.2) |

124 | 38.8 (32.2, 46.0) |

8.61

(7.07, 10.50) |

7.99

(6.48, 9.85) |

| Respiratory and skin allergy | 824 | 2.7 (2.4, 2.9) |

241 | 30.8 (26.8, 35.0) |

6.82

(5.81, 8.01) |

6.28

(5.36, 7.37) |

| Respiratory and food allergy | 386 | 1.3 (1.1, 1.5) |

114 | 28.1 (22.6, 34.3) |

6.23

(5.00, 7.77) |

5.89

(4.72, 7.36) |

| Food and skin allergy | 355 | 1.2 (1.1, 1.4) |

48 | 13.3 (9.5, 18.3) |

2.95

(2.11, 4.12) |

3.05

(2.21, 4.20) |

| Respiratory allergy only | 3012 | 9.6 (9.2, 10.1) |

558 | 19.6 (17.9, 21.4) |

4.34

(3.84, 4.91) |

4.04

(3.57, 4.58) |

| Skin allergy only | 2224 | 7.7 (7.3, 8.2) |

221 | 10.5 (9.0, 12.2) |

2.32

(1.94, 2.78) |

2.32

(1.94, 2.78) |

| Food allergy only | 809 | 2.8 (2.5, 3.0) |

76 | 11.9 (8.7, 16.0) |

2.63

(1.91, 3.61) |

2.73

(2.01, 3.69) |

| No allergy | 20 283 | 73.6 (72.8, 74.3) |

936 | 4.5 (4.1, 4.9) |

Ref | Ref |

aPR, adjusted prevalence ratio (adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity); CI, confidence interval; PR, prevalence ratio; Prev, prevalence; Ref, referent.

Bold numbers are statistically significant.

Table 2.

Characteristics of study population and prevalence of current asthma and allergy by characteristics, 2016–2018

| All children (aged 0–17 years) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| Prevalence of selected health conditions | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Characteristics of study population | Current asthma | Any allergy | Respiratory allergy | Skin allergy | Food allergy | ||

|

|

|||||||

| Characteristics | Sample size n | % (95% CI) |

Prev, % (95% CI) |

Prev, % (95% CI) |

Prev, % (95% CI) |

Prev, % (95% CI) |

Prev, % (95% CI) |

|

| |||||||

| Total | 28 221 | — | 8.1 (7.7, 8.6) |

26.4 (25.7, 27.2) |

14.7 (14.1, 15.3) |

12.7 (12.2, 13.3) |

6.4 (6.0, 6.7) |

| Age group (years) | p < 0.001* | p < 0.001* | p < 0.001* | p < 0.001* | p = 0.91 | ||

| 0–4 | 7621 | 26.9 (26.2, 27.6) |

4.0 (3.5, 4.7) |

23.1 (21.9, 24.3) |

7.9 (7.2, 8.7) |

14.3 (13.4, 15.3) |

6.3 (5.6, 7.0) |

| 5–11 | 10 299 | 39.4 (38.6, 40.1) |

8.8 (8.1, 9.6) |

26.8 (25.7, 27.9) |

15.6 (14.7, 16.6) |

13.1 (12.3, 13.9) |

6.5 (5.9, 7.0) |

| 12–17 | 10 301 | 33.7 (33.0, 34.4) |

10.5 (9.7, 11.4) |

28.6 (27.5, 29.8) |

19.0 (18.0, 20.0) |

11.0 (10.3, 11.8) |

6.4 (5.8, 7.0) |

| Sex | p < 0.001* | p = 0.03* | p < 0.001* | p = 0.12 | p = 0.60 | ||

| Male | 14 688 | 51.0 (50.3, 51.7) |

9.0 (8.4, 9.7) |

27.1 (26.2, 28.1) |

16.3 (15.6, 17.1) |

12.3 (11.6, 13.1) |

6.5 (6.0, 7.0) |

| Female | 13 533 | 49.0 (48.3, 49.7) |

7.1 (6.6, 7.7) |

25.7 (24.6, 26.8) |

13.0 (12.2, 13.8) |

13.1 (12.4, 13.9) |

6.3 (5.7, 6.8) |

| Race (non-Hispanic) and ethnicity | p < 0.001* | p < 0.001* | p < 0.001* | p < 0.001* | p = 0.002* | ||

| White | 15 436 | 51.3 (49.6, 53.0) |

6.8 (6.3, 7.4) |

27.7 (26.7, 28.6) |

16.4 (15.6, 17.2) |

12.1 (11.5, 12.8) |

6.7 (6.2, 7.2) |

| Black | 3244 | 13.4 (12.4, 14.4) |

14.2 (12.8, 15.8) |

29.6 (27.6, 31.6) |

14.0 (12.6, 15.6) |

18.0 (16.4, 19.8) |

6.3 (5.3, 7.5) |

| AI/AN | 299 | 0.9 (0.5, 1.4) |

10.2 (5.6, 17.6) |

15.7 (11.1, 21.7) |

8.0 (4.9, 12.8) |

5.6 (3.4, 9.1) |

4.9† (2.7, 8.9) |

| Asian | 1556 | 5.1 (4.6, 5.6) |

3.8 (3.0, 5.0) |

21.6 (19.3, 24.1) |

10.9 (9.2, 12.7) |

11.2 (9.4, 13.3) |

6.0 (4.8, 7.5) |

| Multiple | 1336 | 4.2 (3.8, 4.6) |

13.0 (10.9, 15.5) |

34.7 (31.4, 38.2) |

20.7 (18.0, 23.7) |

18.5 (16.0, 21.4) |

9.7 (7.8, 12.1) |

| Hispanic | 6265 | 25.2 (23.5, 27.0) |

7.5 (6.6, 8.4) |

22.3 (21.0, 23.6) |

11.6 (10.5, 12.7) |

10.8 (9.8, 11.8) |

5.3 (4.6, 6.1) |

| p = 0.002* | p = 0.01* | p = 0.51 | p = 0.003* | p = 0.21 | |||

| Puerto Rican | 606 | 9.1 (7.7, 10.7) |

13.6 (10.3, 17.8) |

27.5 (23.4, 31.9) |

12.6 (9.4, 16.8) |

15.3 (12.1, 19.1) |

6.3 (4.1, 9.5) |

| Mexican | 3943 | 64.5 (61.4, 67.5) |

6.6 (5.7, 7.6) |

21.0 (19.4, 22.8) |

11.1 (9.8, 12.5) |

9.6 (8.5, 10.9) |

4.8 (4.0, 5.8) |

| Other Hispanic | 1716 | 26.4 (23.9, 29.0) |

7.6 (6.0, 9.5) |

23.4 (20.8, 26.3) |

12.4 (10.4, 14.6) |

12.0 (10.1, 14.1) |

6.1 (4.8, 7.8) |

| Ratio of family income to federal poverty threshold | p < 0.001* | p < 0.001* | p < 0.001* | p = 0.48 | p < 0.001* | ||

| <100% FPL | 4359 | 18.5 (17.6, 19.5) |

10.6 (9.3, 11.9) |

25.2 (23.5, 26.9) |

13.6 (12.3, 15.0) |

13.5 (12.2, 15.0) |

5.8 (4.9, 6.8) |

| 100% to <250% FPL | 8452 | 31.4 (30.4, 32.4) |

8.8 (8.1, 9.7) |

24.4 (23.1, 25.7) |

13.0 (12.1, 13.9) |

12.4 (11.4, 13.4) |

5.8 (5.2, 6.4) |

| 250% to <450% FPL | 7474 | 24.9 (24.1, 25.6) |

7.2 (6.4, 8.0) |

26.6 (25.3, 28.0) |

15.3 (14.2, 16.4) |

12.4 (11.5, 13.4) |

6.1 (5.5, 6.9) |

| ≥450% FPL | 7937 | 25.2 (24.0, 26.5) |

6.3 (5.7, 7.0) |

29.7 (28.4, 31.0) |

17.0 (16.0, 18.1) |

12.9 (12.0, 13.9) |

7.8 (7.0, 8.6) |

| U.S. Census region | p = 0.01* | p = 0.46 | p = 0.35 | p = 0.44 | p = 0.20 | ||

| Northeast | 4469 | 17.1 (15.5, 18.8) |

9.1 (7.8, 10.7) |

25.5 (23.7, 27.5) |

13.8 (12.3, 15.4) |

11.9 (10.6, 13.3) |

7.0 (6.0, 8.2) |

| Midwest | 6043 | 21.2 (19.8, 22.6) |

8.0 (7.2, 8.8) |

25.9 (24.2, 27.6) |

14.4 (13.1, 15.8) |

12.4 (11.3, 13.5) |

5.8 (5.2, 6.6) |

| South | 10 414 | 37.4 (35.1, 39.8) |

8.5 (7.8, 9.2) |

27.1 (25.9, 28.3) |

15.3 (14.4, 16.4) |

13.0 (12.1, 13.9) |

6.2 (5.6, 6.8) |

| West | 7295 | 24.3 (22.2, 26.6) |

6.9 (6.2, 7.7) |

26.5 (25.0, 28.0) |

14.5 (13.5, 15.6) |

13.2 (12.1, 14.4) |

6.7 (6.0, 7.5) |

AI/AN, American Indian or Alaska Native; CI, confidence interval; FPL, federal poverty level; Prev, prevalence.

Statistically significant.

Relative standard error ≥30% indicates unreliable estimate.

Association between allergy and current asthma

All allergy types studied were significantly associated with having current asthma. Children with allergy were 2 to 8 times more likely to have current asthma than children without allergy. Specifically, children were more likely to have current asthma if reported having all three allergies (aPR = 7.99 [6.48, 9.85]), followed by having respiratory and skin allergy (aPR = 6.28 [5.36, 7.37]), respiratory and food allergy (aPR = 5.89 [4.72, 7.36]), respiratory allergy only (aPR = 4.04 [3.57, 4.58], food and skin allergy (aPR = 3.05 [2.21, 4.20]), food allergy only (aPR = 2.73 [2.01, 3.69]), and skin allergy only (aPR = 2.32 [1.94, 2.78]) versus having no allergies (Table 1).

Trends

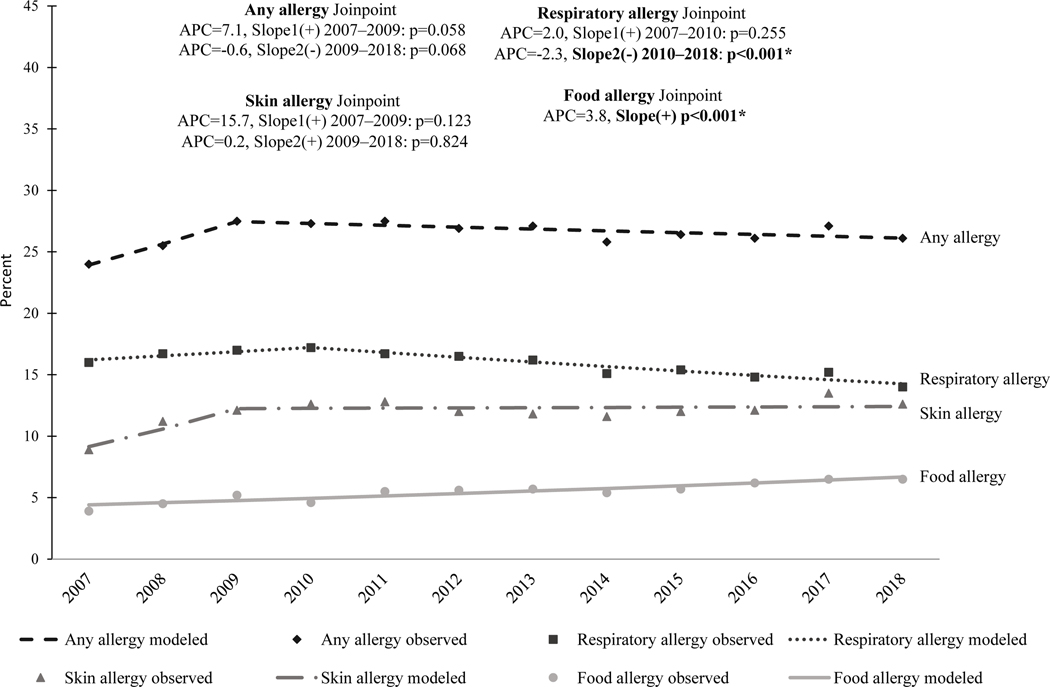

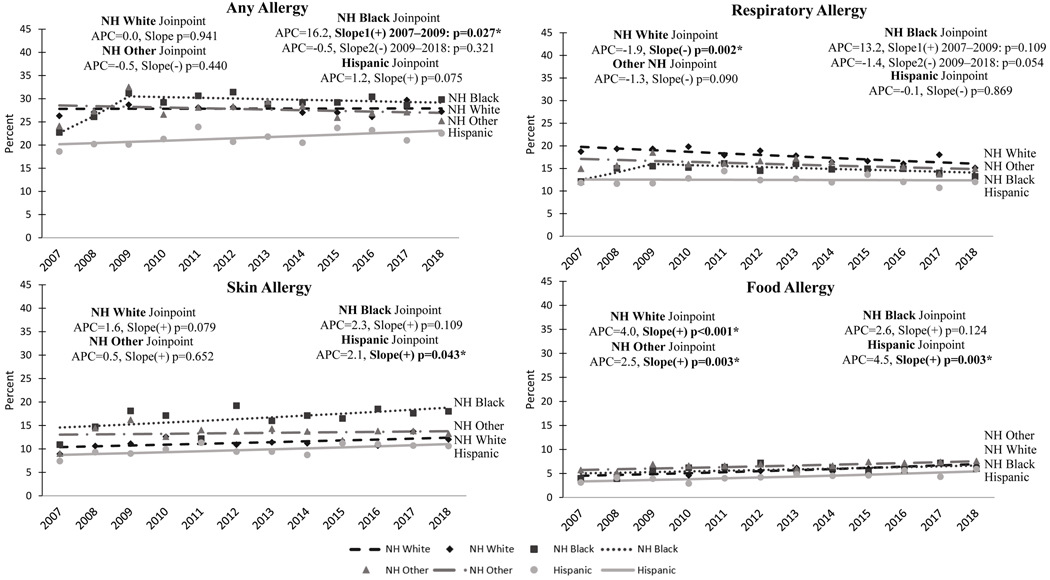

Respiratory allergy prevalence among children aged 0–17 years significantly decreased from 17.2% in 2010 to 14.0% in 2018 (slope (−) p < 0.001), and food allergy prevalence increased from 3.9% in 2007 to 6.5% in 2018 (slope (+) p < 0.001) (Fig 1). However, no significant trends in any allergy and skin allergy were observed during 2007–2018 (Fig 1). Allergy trends among White children (Fig 2) were similar to allergy trends among all children aged 0–17 years: respiratory allergy decreased (slope (−) p = 0.002) and food allergy increased (slope (+) p < 0.001) during 2007–2018. However, among Black children, no significant changes were observed in the prevalence of respiratory, skin, and food allergies during 2007–2018. Although, the prevalence of any allergy among Black children significantly increased during 2007–2009 (slope (+) p = 0.027), with no changes since then (Fig 2). During 2007–2018, an increasing trend in food allergy among other race children (slope (+) p = 0.003) (Fig 2) and increasing trend in food allergy (slope (+) p = 0.003) and skin allergy (slope (+) p = 0.043) among Hispanic children (Fig 2) were observed.

Figure 1.

Allergy prevalence among children by allergy type and year, 2007–2018. APC, annual percent change. Any allergy includes having had hay fever, respiratory allergy, skin allergy, or food allergy in the past 12 months. *p-value of trend line slope is statistically significant at 0.05. Model-based (trend line) and observed prevalence estimates (dots) were plotted.

Figure 2.

Allergy prevalence among children by race and ethnicity and year, 2007–2018. APC, annual percent change. NH, non-Hispanic. Any allergy includes having had hay fever, respiratory allergy, skin allergy, or food allergy in past 12 months. *p-value of trend line slope is statistically significant at 0.05. Model-based (trend line) and observed prevalence estimates (dots) were plotted.

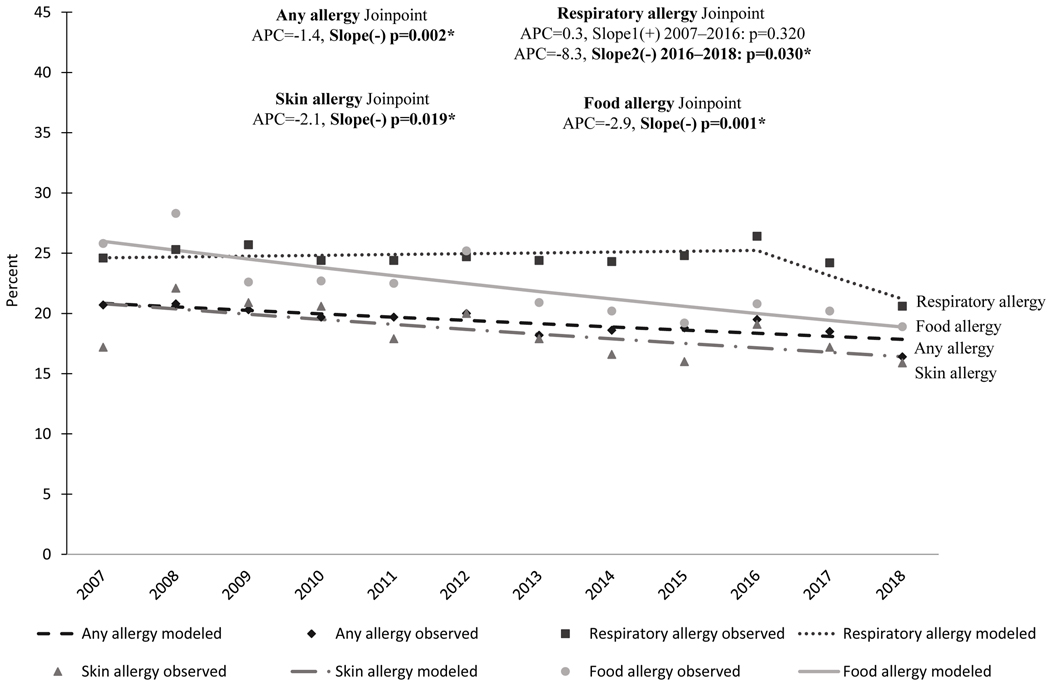

The prevalence of current asthma decreased among all children from 9.1% in 2007 to 7.5% in 2018 (slope (−) p < 0.001), and also among children with allergy from 20.7% to 16.4% (slope (−) p = 0.002) (Fig 3). Although decreases were observed among all racial and ethnic groups with allergy studied, only the trend among White children with allergy was statistically significant (slope (−) p = 0.03).

Figure 3.

Current asthma prevalence by allergy type among children by year, 2007–2018. APC, annual percent change. *p-value of trend line slope is statistically significant at 0.05. Model-based (trend line) and observed prevalence estimates (dots) were plotted.

Allergy and asthma prevalence by demographic characteristics

Prevalence of any allergy was significantly associated with age group (p < 0.001), sex (p = 0.03), race and ethnicity (p < 0.001), and family income (p < 0.001). Having had any allergy was more common among 5 years of age and older (5–11 years: 26.8% [95% CI: 25.7, 27.9]; 12–17 years: 28.6% [27.5, 29.8]), males (27.1% [26.2, 28.1]), multiracial children (34.7% [31.4, 38.2]), and children living in families with incomes ≥450% FPL (29.7% [29.4, 31.0]) compared with ages 0–4 years (23.1% [21.9, 24.3]), girls (25.7% [24.6, 26.8]), White children (27.7% [26.7, 28.6]), and children living in families with incomes <450% FPL (<100% FPL: 25.2% [23.5, 26.9]; 100% to <250% FPL: 24.4% [23.1, 25.7]; 250% to <450% FPL: 26.6% [25.3, 28.0]) (Table 2).

Prevalence of respiratory allergy was significantly associated with age group (p < 0.001), sex (p < 0.001), and race and ethnicity (p < 0.001). Respiratory allergy prevalence increased with increasing age, from 7.9% (7.2, 8.7) for children aged 0–4 years to 19.0% (18.0, 20.0) for children aged 12–17 years. The prevalence was higher among males (16.3% [15.6, 17.1]) than females (13.0% [12.2, 13.8]), and among multiracial children (20.7% [18.0, 23.7]) than among White children (16.4% [15.6, 17.2]) (Table 2).

Prevalence of skin allergy was significantly associated with age group (p < 0.001) and race and ethnicity (p < 0.001). Skin allergy was more common among children aged 0–4 years (14.3% [13.4, 15.3]) and aged 5–11 years (13.1% [12.3, 13.9]) than among children aged 12–17 years (11.0% [10.3, 11.8]). Skin allergy was more common among Black children (18.0% [16.4, 19.8]) and multiracial children (18.5% [16.0, 21.4]) compared with AI/AN children (5.6% [3.4, 9.1]), Asian children (11.2% [9.4, 13.3]), Hispanic children (10.8% [9.8, 11.8]), and White children (12.1% [11.5, 12.8]) (Table 2).

Prevalence of food allergy was significantly associated with race and ethnicity (p = 0.91) and family income (p < 0.001). Food allergy prevalence was higher among multiracial children (9.7% [7.8, 12.1]) compared with the prevalence among children of all other racial and ethnic groups. The prevalence was also higher among White children (6.7% [6.2, 7.2]) than among Hispanic children (5.3% [4.6, 6.1]). The prevalence was higher among children living in families with incomes ≥450% FPL (7.8% [7.0, 8.6]) than among children living in families with incomes <450% FPL (<100% FPL: 5.8% [4.9, 6.8]; 100% to <250% FPL: 5.8% [5.2, 6.4]; 250% to <450% FPL: 6.1% [5.5, 6.9]) (Table 2).

Among children aged 0–17 years with allergy, current asthma prevalence was higher among children aged ≥5 years (5–11 years: 20.1%; 12–17 years: 21.2%) than aged 0–4 years (10.1%); boys than girls (19.5% vs. 16.6%); Black (27.0%), multiracial (23.8%), or Hispanic children (18.2%) than White children (15.4%); those living in families with incomes <250% FPL (<100% FPL: 22.6%; 100% to <250% FPL: 20.4%) than incomes ≥450% FPL (15.0%); and children living in the Northeast (20.8%) or Midwest (18.6%) than living in the West (14.8%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association between characteristics and current asthma by allergy, 2016–2018

| Children (aged 0–17 years) | Children (aged 0–17 years) with any allergy | Children (aged 0–17 years) without any allergy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Prevalence of any allergy | Prevalence of current asthma | Prevalence of current asthma | ||||

|

|

||||||

| Characteristics | Prev, % (95% CI) |

aPR (95% CI) |

Prev, % (95% CI) |

aPR (95% CI) |

Prev, % (95% CI) |

aPR (95% CI) |

|

| ||||||

| Total | 26.4 (25.7, 27.2) |

-- | 18.1 (17.0, 19.3) |

-- | 4.5 (4.1, 4.9) |

-- |

| Age group (years) * | ||||||

| 0–4 | 23.1 (21.9, 24.3) |

Ref | 10.1 (8.4, 12.1) |

Ref | 2.2 (1.7, 2.8) |

Ref |

| 5–11 | 26.8 (25.7, 27.9) |

1.17

(1.09, 1.24) |

20.1 (18.2, 22.0) |

2.00

(1.64, 2.43) |

4.7 (4.1, 5.4) |

2.19

(1.68, 2.85) |

| 12–17 | 28.6 (27.5, 29.8) |

1.24

(1.17, 1.32) |

21.2 (19.3, 23.2) |

2.21

(1.80, 2.70) |

6.3 (5.5, 7.1) |

2.91

(2.20, 3.84) |

| Sex * | ||||||

| Male | 27.1 (26.2, 28.1) |

Ref | 19.5 (18.0, 21.2) |

Ref | 5.1 (4.6, 5.7) |

Ref |

| Female | 25.7 (24.6, 26.8) |

0.95

(0.90, 0.99) |

16.6 (15.1, 18.2) |

0.83

(0.73, 0.94) |

3.9 (3.4, 4.4) |

0.76

(0.64, 0.89) |

| Race (non-Hispanic) and ethnicity * | ||||||

| White | 27.7 (26.7, 28.6) |

Ref | 15.4 (14.1, 16.9) |

Ref | 3.5 (3.1, 4.0) |

Ref |

| Black | 29.6 (27.6, 31.6) |

1.07 (1.00, 1.16) |

27.0 (23.9, 30.4) |

1.81

(1.57, 2.09) |

8.8 (7.4, 10.5) |

2.49

(2.00, 3.10) |

| AI/AN | 15.7 (11.1, 21.7) |

0.56

(0.40, 0.80) |

26.6 (15.1, 42.5) |

1.77

(1.05, 2.98) |

7.1† (3.0, 16.1) |

1.93 (0.83, 4.52) |

| Asian | 21.6 (19.3, 24.1) |

0.78

(0.69, 0.88) |

12.2 (9.1, 16.2) |

0.79 (0.58, 1.07) |

1.5 (0.9, 2.5) |

0.43

(0.26, 0.72) |

| Multiple | 34.7 (31.4, 38.2) |

1.26

(1.14, 1.40) |

23.8 (19.1, 29.1) |

1.55

(1.23, 1.95) |

7.3 (5.3, 9.9) |

2.17

(1.55, 3.02) |

| Hispanic | 22.3 (21.0, 23.6) |

0.81

(0.76, 0.86) |

18.2 (15.9, 20.9) |

1.23

(1.04, 1.45) |

4.4 (3.7, 5.2) |

1.26

(1.01, 1.56) |

| Ratio of family income to federal poverty threshold | ||||||

| <100% FPL | 25.2 (23.5, 26.9) |

0.87

(0.80, 0.95) |

22.6 (19.5, 26.0) |

1.37

(1.13, 1.67) |

6.5 (5.4, 7.8) |

2.06

(1.58, 2.70) |

| 100% to <250% FPL | 24.4 (23.1, 25.7) |

0.84

(0.79, 0.90) |

20.4 (18.4, 22.5) |

1.29

(1.10, 1.51) |

5.1 (4.4, 5.9) |

1.70

(1.34, 2.16) |

| 250% to <450% FPL | 26.6 (25.3, 28.0) |

0.90

(0.84, 0.96) |

16.0 (14.0, 18.2) |

1.05 (0.89, 1.24) |

4.0 (3.4, 4.7) |

1.39

(1.09, 1.77) |

| ≥450% FPL | 29.7 (28.4, 31.0) |

Ref | 15.0 (13.2, 16.9) |

Ref | 2.7 (2.2, 3.2) |

Ref |

| U.S. Census region | ||||||

| Northeast | 25.5 (23.7, 27.5) |

0.91 (0.83, 1.00) |

20.8 (17.6, 24.6) |

1.38

(1.11, 1.72) |

5.1 (4.0, 6.5) |

1.24 (0.92, 1.67) |

| Midwest | 25.9 (24.2, 27.6) |

0.90

(0.83, 0.98) |

18.6 (16.4, 21.2) |

1.26

(1.03, 1.54) |

4.3 (3.7, 5.0) |

1.05 (0.83, 1.33) |

| South | 27.1 (25.9, 28.3) |

0.96 (0.90, 1.03) |

18.8 (17.2, 20.5) |

1.14 (0.96, 1.37) |

4.6 (4.0, 5.4) |

0.98 (0.78, 1.23) |

| West | 26.5 (25.0, 28.0) |

Ref | 14.8 (12.8, 17.2) |

Ref | 4.1 (3.4, 4.8) |

Ref |

AI/AN, American Indian/Alaska Native; aPR, adjusted prevalence ratio (adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity); CI, confidence interval; FPL, federal poverty level; Prev, prevalence; Ref, referent.

Bold numbers statistically significant.

For these variables only adjusted for other two.

Relative standard error ≥30% unreliable estimate.

Association between allergy and asthma-related health outcomes among children with current asthma

Among children with current asthma, having any allergy was significantly associated with missed school days (aPR: 1.33 [1.03, 1.72]) and taking preventive medication daily (aPR: 1.89 [1.32, 2.71]). Having any allergy was not significantly associated with asthma attack, taking quick relief medication in the past 3 months, emergency department visits, or hospitalization (Table 4).

Table 4.

Association between asthma indicators and allergies among U.S. children with current asthma, 2018

| Children with current asthma | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| With allergies | Without allergies | p-value | |||||

| Prevalence of asthma indicators | Prev, % (95% CI) |

Unadjusted PR (95% CI) |

aPR (95% CI) |

Prev, % (95% CI) |

Unadjusted PR (95% CI) |

aPR (95% CI) |

|

|

| |||||||

| Asthma attack | 57.8 (50.9, 64.4) |

1.19 (0.97, 1.45) |

1.18 (0.98, 1.43) |

48.6 (40.5, 56.8) |

Ref | Ref | 0.088 |

| Missed school days | 49.5 (42.2, 56.9) |

1.32

(1.02, 1.73) |

1.33

(1.03, 1.72) |

37.4 (29.4, 46.0) |

Ref | Ref | 0.031* |

| Medication use | |||||||

| Taken quick relief inhaler in past 3 months | 70.4 (63.3, 76.6) |

1.15 (0.98, 1.35) |

1.16 (0.99, 1.36) |

61.4 (52.9, 69.3) |

Ref | Ref | 0.091 |

| Take preventative medication daily | 33.7 (28.1, 39.8) |

1.89

(1.32, 2.71) |

1.89

(1.32, 2.71) |

17.8 (12.9, 24.2) |

Ref | Ref | <0.001* |

| Healthcare use | |||||||

| Emergency department visit | 20.6 (16.0, 26.2) |

1.29 (0.81, 2.04) |

1.34 (0.85, 2.10) |

16.0 (10.9, 23.0) |

Ref | Ref | 0.266 |

| Hospitalization | 5.3† (2.8, 9.8) |

2.77 (0.84, 9.11) |

3.08 (0.95, 9.97) |

§ | Ref | Ref | 0.089 |

aPR, adjusted prevalence ratio (adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity); CI, confidence interval; PR, prevalence ratio; Prev, prevalence; Ref, referent.

Bold numbers statistically significant.

Statistically significant.

Relative standard error ≥30% unreliable estimate.

Relative standard error is ≥50% suppressed estimate.

Discussion

The study analyzed the NHIS data from 2007–2018 to assess asthma and allergy, trends by race and ethnicity, the association between allergy and asthma prevalence, and between allergy and asthma-related health outcomes among U.S. children (aged 0–17 years). Asthma was significantly associated with any type of allergy (i.e., respiratory allergy, skin allergy, and food allergy), and the strength of the association differed by type and number of allergies. Prevalence of current asthma decreased significantly among all children over the years, and among children with allergy for all racial and ethnic groups. However, the decreasing trend in asthma prevalence was statistically significant only among White children. Prevalence of current asthma also decreased in earlier part of 2010 according to past studies.21,22 Considering multifactorial nature of asthma, reasons for this decrease could not be ascertained in this study with certainty, however, improved use of emerging evidence-based strategies in asthma diagnosis and the medical management of asthma1,3 may have contributed to the decrease. Specifically, these strategies may reduce misdiagnosis of asthma by improving differential diagnosis, particularly among children less than 5 years. Also may control asthma symptoms through better management of asthma (e.g., avoiding or reducing asthma triggers such as allergens and irritants) and providing improved asthma education and medical care.1,3,8 These actions may lead to a “no” response on whether still have asthma. Thereby contributing to lower percentage of children with current asthma captured in the survey.

Similar to previous publications, this study’s findings also indicate a decreasing trend in prevalence of respiratory allergy4, increasing trend in prevalence of food allergy4,23, and a stable trend in prevalence of skin allergy among children. Prevalence of food allergies increased significantly for all races, except among Black children. Previous studies6 suggested that environmental factors interacting with genetics6 and changes in risk profiles among children with asthma4 might explain increasing trend in food allergy.

Our assessment of allergy status among U.S. children indicates that the findings differed by demographic factors and poverty level. This study shows that having allergy was more prevalent among multiracial children and having higher family income. Multiracial and Black children had higher prevalence of skin allergy, whereas White children had higher prevalence of respiratory allergy. Other studies have reported that prevalence of skin allergy was higher among Black than White children with asthma4. Eczema severity was associated with Black race,24,25 Hispanic ethnicity,24 and lower socioeconomic status24,25. Atopic dermatitis incidence and persistence was higher among certain non-White racial and ethnic groups.26 Social and economic factors might contribute to increased atopic dermatitis susceptibility among African Americans.25 Furthermore, similar to the previous studies,4,27 this study also shows that prevalence of any allergy, and particularly food allergy, was higher among children living in families with higher income. Low food allergy prevalence found in poor, urban neighborhoods might be partly explained due to less well perceived and diagnosed due to limited access to health care.28

This study reports that the strength of the association between allergy and asthma varied (2 to 8 times) by type and number of allergies indicating a compound effect. The strong association was observed between current asthma and having all three allergies, followed by having two allergies that include respiratory allergy. As reported in this study, as well as in other studies, allergies and asthma are well-known comorbidities4,29 and the presence of one allergic condition such as asthma, allergy, and eczema increase the risk for developing another5. Children with coexisting allergic conditions are at greater risk for severe asthma,12 which might require more complex medical management for symptom control.8 The present study found that children who had both asthma and allergy were more likely to take preventive medication daily and to have missed school days than children with asthma but no allergy. Hsu et al15 found that uncontrolled asthma, asthma exacerbations, and urgent or emergency treatment of asthma are associated with any missed school days. This may suggest that children with asthma and allergies might experience more health problems that need more preventive medication to control asthma symptoms.8,12

This study is subject to at least four limitations. First, the data are self-reported by an adult proxy for a child. The responses might be tempered by social desirability and recall biases and possible misclassification, especially if the proxy adult is less familiar with child’s health history. Second, allergy and asthma data are measured by survey questions with limited specificity on definitions of allergy types. Third, birth order may affect the results. Data were not available for sensitivity analyses to assess effects of birth order on the results. However, selection bias based on birth order in this study is unlikely because households were selected using complex sampling design, sample child was randomly selected from each family with children, and an inflation factor was applied to the sample weight that accounts for selection probability of “sample child” in the family.18,19 Finally, cross-sectional survey data were used for the analyses. Therefore, associations are not necessarily causal and other factors not included in the study might have contributed to associations.

In summary, this study shows a decreasing trend of asthma and respiratory allergy among children across time, differing by race and ethnicity. Disparities in asthma and allergies by demographic factors and income level remain, and the associations between asthma and allergies are strong and affect certain asthma outcomes. These findings, by increasing awareness among clinicians and public health providers, might help in clinical management of asthma, allocation of resources in public health programs, and implementation of tailored intervention strategies to reduce the burden of asthma and allergy.

Acknowledgements

Would like to acknowledge and thank Don Meadows and Dr. Dana Flanders for editing assistance.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Abbreviations/Acronyms:

- NHIS

National Health Interview Survey

- U.S

United States

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- AI/AN

non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native

- PR

Unadjusted prevalence ratio

- aPR

Adjusted Prevalence Ratio

- CIs

95% confidence intervals

- APC

Annual Percent Change

- FPLs

Federal poverty levels

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none

References

- 1.Expert Panel Working Group of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) administered and coordinated National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Coordinating Committee (NAEPPCC), Cloutier MM, Baptist AP, Blake KV, Brooks EG, Bryant-Stephens T, et al. 2020 Focused Updates to the Asthma Management Guidelines: A Report from the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Coordinating Committee Expert Panel Working Group. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020. Dec;146(6):1217–1270. Erratum in: J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147(4):1528–1530. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Most recent national asthma data. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2020. [updated 2021 March 30; cited 2021 July 16]. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_national_asthma_data.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. Fontana, WI: Global Initiative for Asthma; 2020. Available at: https://ginasthma.org/gina-reports. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akinbami LJ, Simon AE, Schoendorf KC. Trends in allergy prevalence among children aged 0–17 years by asthma status, United States, 2001–2013. J Asthma. 2016;53(4):356–362. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2015.1126848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di Palmo E, Gallucci M, Cipriani F, Bertelli L, Giannetti A, Ricci G. Asthma and food allergy: which risks? Medicina 2019;55(9):509. doi: 10.3390/medicina55090509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Finding a path to safety in food allergy: assessment of the global burden, causes, prevention, management, and public policy. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2017. doi: 10.17226/23658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sweeney A, Sampath V, Nadeau KC. Early intervention of atopic dermatitis as a preventive strategy for progression of food allergy. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2021;17(1):30. doi: 10.1186/s13223-021-00531-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Third Expert Panel on the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Bethesda, Md: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health; August 2007. 440 pp. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK7232/. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burbank AJ, Sood AK, Kesic MJ, Peden DB, Hernandez ML. Environmental determinants of allergy and asthma in early life. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Venter C, Palumbo MP, Sauder KA, Glueck DH, Liu AH, Yang IV, et al. Incidence and timing of offspring asthma, wheeze, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, and food allergy and association with maternal history of asthma and allergic rhinitis. World Allergy Organ J. 2021;14(3):100526. doi: 10.1016/j.waojou.2021.100526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Licari A, Manti S, Giorgio C. What are the effects of rhinitis on patients with asthma? Expert Rev Respir Med. 2019;13(6)503–505. doi: 10.1080/17476348.2019.1604227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caffarelli C, Garrubba M, Greco C, Mastrorilli C, Povesi Dascola C. Asthma and food allergy in children: is there a connection or interaction? Front Pediatr. 2016;5(4):34. doi: 10.3389/fped.2016.00034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pijnenburg MW, Fleming L. Advances in understanding and reducing burden of severe asthma in children. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:1032–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Licari A, Brambilla I, Filippo MD, Poddighe D, Castagnoli R, Marseglia GL. The role of upper airway pathology as a comorbidity in severe asthma. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2017;11(11);855–865. doi: 10.1080/17476348.2017.1381564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsu J, Qin X, Beavers SF, Mirabelli MC. Asthma-related school absenteeism, morbidity, and modifiable factors. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dierick BJH, van der Molen T, Flokstra-de Blok BMJ, Muraro A, Postma MJ, Kocks JWH, van Boven JFM. Burden and socioeconomics of asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis and food allergy. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2020;20(5):437–453. doi: 10.1080/14737167.2020.1819793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Center for Health Statistics. Survey description, National Health Interview Survey, 2018. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2019. Available at: https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NHIS/2018/srvydesc.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parsons VL, Moriarity C, Jonas K, Moore TF, Davis KE, Tompkins L. Design and estimation for the National Health Interview Survey, 2006– 2015. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2014;2(165):1–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moriarity C, Parsons VL, Jonas K, Schar BG, Bose J, Bramlett MD. Sample design and estimation structures for the National Health Interview Survey, 2016–2025. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2022;2(191). doi: 10.15620/cdc:115394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Cancer Institute. Joinpoint regression program. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 25 March 2021. Available at: https://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/. Accessed July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zahran HS, Bailey CM, Damon SA, Garbe PL, Breysse PN. Vital signs: asthma in children—United States, 2001–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:149–155. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6705e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akinbami LG, Simon AE, Rossen LM. Changing trends in asthma prevalence among children. Pediatrics. 2016;137(1):1–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahdavinia M, Fox SR, Smith BM, James C, Palmisano EL, Mohammed A, et al. Racial differences in food allergy phenotype and health care utilization among US children. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(2):352–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silverberg JI, Simpson EL. Associations of childhood eczema severity: a US population-based study. Dermatitis. 2014;25(3):107–114. doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Croce EA, Levy MA, Adewole SA, Matsui EC. Reframing racial and ethnic disparities in atopic dermatitis in Black and Latinx populations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;148(5):1104–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim Y, Blomberg M, Rifas-Shiman SL, Camargo CA, Gold DR, Thyssen JP, et al. Racial/Ethnic differences in incidence and persistence of childhood atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139(4):827–834. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2018.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uphoff E, Cabieses B, Pinart M, Valdés M, Antó JM, Wright J. A systematic review of socioeconomic position in relation to asthma and allergic diseases. Eur Respir J. 2015;46(2):364–374. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00114514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGowan EC, Matsui EC, McCormack MC, Pollack CE, Peng R, Keet CA. Effect of poverty, urbanization, and race/ethnicity on perceived food allergy in the United States. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;115(1):85–6.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2015.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kankaanranta H, Kauppi P, Tuoisto LE, Ilmarinen P. Emerging comorbidities in adult asthma: risks, clinical associations, and mechanisms. Mediators Inflamm. 2016;2016:3690628. doi: 10.1155/2016/3690628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]