Abstract

The Oncology Grand Rounds series is designed to place original reports published in the Journal into clinical context. A case presentation is followed by a description of diagnostic and management challenges, a review of the relevant literature, and a summary of the authors’ suggested management approaches. The goal of this series is to help readers better understand how to apply the results of key studies, including those published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, to patients seen in their own clinical practice.

The development of immune checkpoint inhibitors has revolutionized the management of recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (R/M HNSCC). The landmark KEYNOTE-048 clinical trial established the programmed death-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab with and without chemotherapy as a new standard first-line treatment for patients with platinum-sensitive R/M HNSCC. Nonetheless, clinical decision making can be challenging when considering the significant morbidity associated with rapidly progressive disease in high-risk locations, patient fitness, and programmed death-ligand 1 expression. Both planned and unplanned subgroup analyses from KEYNOTE-048 provide valuable insights into how therapy for untreated R/M HNSCC may be optimized for individual patients. Given differences in the toxicity profile of pembrolizumab alone versus in combination with chemotherapy, prioritizing patient preference is paramount in this palliative treatment setting. Here, the case of a patient presenting with de novo metastatic HNSCC is discussed to highlight the practical application of KEYNOTE-048 data in clinical practice.

CASE PRESENTATION

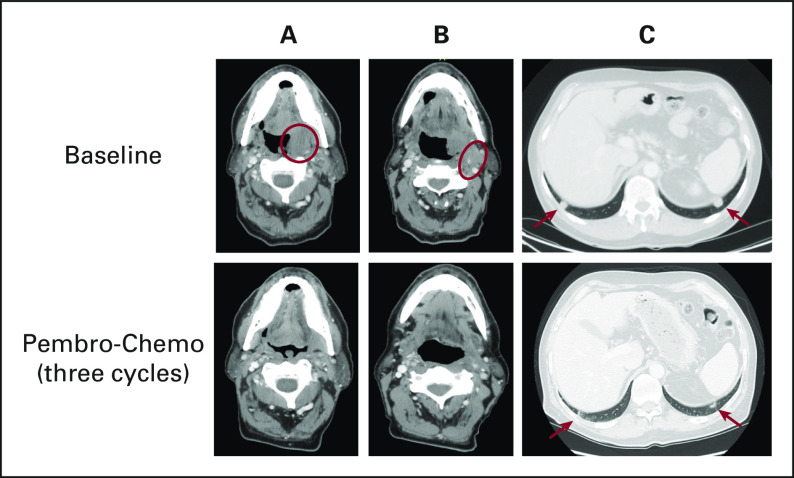

A 65-year-old nonsmoking man with a remote history of Hodgkin lymphoma previously treated with mediastinal radiation presented with dysphagia, dysarthria, and mild oropharyngeal pain. Otolaryngology examination revealed a left tonsil mass. On computed tomography, the primary tonsil tumor was 3.6 × 2.5 × 3.5 cm and involved the left hypoglossal muscle, submandibular gland, and soft palate with extension across the midline (Fig 1). Bilateral, malignant cervical neck lymphadenopathy was also seen, including a left level 2A 3.1-cm conglomerate mass that encased the proximal left external carotid artery. Staging scans revealed bilateral pulmonary nodules, the largest of which measured 1.5 cm. Biopsy of the left tonsil primary and of a lung nodule each disclosed invasive squamous cell carcinoma, positive for human papilloma virus (HPV) by RNA in situ hybridization. Programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) immunohistochemistry staining yielded a combined positive score (CPS) of 0 in the primary tumor and a CPS of 8 in the lung metastasis. He presented to our service for initial treatment recommendations.

FIG 1.

Sixty-five year-old man with metastatic HPV-positive HNSCC. The images are computed tomography axial views of the locoregional and metastatic tumors in this patient. A (red circle), Left tonsil primary with significant regression after pembro-chemo. B (red circle), Left level IIA conglomerate nodal metastasis encasing and narrowing the external carotid artery; medially adjacent is the primary tumor. Treatment with pembro-chemo resulted in significant regression and increased patency of the external carotid artery. C (red arrows), Bilateral lung metastases with significant regression on pembro-chemo. HPV, human papilloma virus; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; pembro-chemo, pembrolizumab-chemotherapy.

CLINICAL CHALLENGES IN EVALUATION AND TREATMENT

Head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCCs) originating in the upper aerodigestive tract (oral cavity, oropharynx, larynx, and hypopharynx) affect > 50,000 individuals annually in the United States1 and > 600,000 people worldwide.2 HNSCC is a challenging diagnosis given the significant cosmetic and functional morbidity often associated with the disease and standard treatment approaches. Recurrent or metastatic (R/M) HSNCC is typically incurable and carries a poor prognosis. Before the immunotherapy era, standard first-line treatment for advanced, platinum-sensitive HNSCC consisted of the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor cetuximab combined with platinum/fluorouracil (FU) doublet chemotherapy, yielding a median overall survival (OS) of approximately 10 months in the EXTREME trial.3

The development of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) targeting the programmed death 1 (PD-1)/PD-L1 pathway to overcome T-cell exhaustion and tumor immune evasion has proven to be the most consequential development for HNSCC therapeutics in the past decade, improving survival for metastatic patients in the platinum-refractory setting.4,5 The KEYNOTE-048 trial comparing the PD-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab, with or without platinum/FU, with the standard arm of cetuximab plus platinum/FU established pembrolizumab-based therapies as first-line treatment for patients with platinum-sensitive R/M HNSCC.6 As with many pembrolizumab trials, PD-L1 expression was quantified on this study using the CPS, defined as the number of PD-L1 immunohistochemistry-positive tumor, lymphocyte, and macrophage cells divided by the total number of tumor cells × 100.

In the companion to this article, Harrington et al7 provide updated study outcomes from KEYNOTE-048 with approximately 4 years of follow-up, validating the OS advantage of pembrolizumab with or without chemotherapy over cetuximab-chemotherapy for patients with CPS ≥ 20 and CPS ≥ 1 tumors, as well as the survival benefit of pembrolizumab-chemotherapy among all patients regardless of CPS. For patients with CPS ≥ 1 tumors, choosing between pembrolizumab or pembrolizumab-chemotherapy requires consideration of several clinicopathologic factors, including (1) tumor growth rate, location, and symptomatology; (2) patient fitness for chemotherapy; (3) PD-L1 CPS; and (4) patient preference. Although KEYNOTE-048 was not designed to directly compare the outcomes observed between the pembrolizumab alone and pembrolizumab-chemotherapy arms, considering how each performed relative to cetuximab-chemotherapy within different CPS subgroups (with or without formal statistical testing) aids in clinical decision making for individual patients. Below, we discuss some key factors to consider when applying KEYNOTE-048 data to HNSCC patient management.

GAUGING THE CLINICAL NEED FOR TUMOR RESPONSE

Despite the survival advantage of pembrolizumab-based therapies, neither arm meaningfully improved objective response rate (ORR) or progression-free survival (PFS) over cetuximab-chemotherapy. Compared with the standard arm, the ORR of the pembrolizumab alone arm was numerically inferior and declined with lower CPS (for pembrolizumab [P] v cetuximab-chemotherapy [C-C]: 23.3% v 36.1% [CPS ≥ 20]; 19.1% v 34.9% [CPS ≥ 1]).7 Progression of disease as best response was numerically higher with pembrolizumab as well (CPS ≥ 20, 31.6% [P] v 9.8% [C-C]; CPS ≥ 1, 38.9% [P] v 12.9% [C-C]),7 resulting in inferior 6-month PFS compared with cetuximab-chemotherapy, as initially reported with approximately 12 months of follow-up (CPS ≥ 20, 32% [P] v 45% [C-C]; CPS ≥ 1, 28% [P] v 43% [C-C]).6 One driver of survival benefit achieved with pembrolizumab alone over cetuximab-chemotherapy was the remarkably long median duration of response (DOR) achieved among those who experienced complete or partial responses (CPS ≥ 20, 23.4 [P] v 4.2 months [C-C]; CPS ≥ 1, 24.8 [P] v 4.5 months [C-C]).6 That substantial difference in DOR contributed to the high percentage of long-term pembrolizumab alone survivors (approximately 20% alive at approximately 4 years).7 Said another way, when effective, pembrolizumab elicits unprecedented efficacy against R/M HNSCC, but the benefit is limited to a minority of patients. For that reason, when tumor regression with therapy is an urgent priority for CPS ≥ 1 patients because of rapidly progressive disease, tumor in critical anatomic locations, or tumor-related symptoms, pembrolizumab-chemotherapy is preferred over pembrolizumab monotherapy as it achieves a higher response rate that is comparable with cetuximab-chemotherapy (for pembrolizumab-chemotherapy [P-C] v C-C: 43.7% v 38.2% [CPS ≥ 20]; 37.2% v 35.7% [CPS ≥ 1]).7 It should be noted that progression of disease was still higher with pembrolizumab-chemotherapy relative to the standard arm (CPS ≥ 20, 15.1% [P-C] v 8.2 [C-C]; CPS ≥ 1, 17.4% [P-C] v 12.3% [C-C]), although the differences were smaller than what was observed with pembrolizumab alone.7 Despite the apparent ORR advantage of pembrolizumab-chemotherapy over pembrolizumab alone, the median OS for each of these arms within the CPS ≥ 1 groups were numerically close (CPS ≥ 20, 14.7 [P-C] v 14.9 months [P]; CPS ≥ 1, 13.6 [P-C] v 12.3 months [P]) while the median DOR achieved with adding chemotherapy to pembrolizumab was inferior to pembrolizumab alone (CPS ≥ 20, 7.0 [P-C] v 23.4 months [P]; CPS ≥ 1, 6.7 [P-C] v 24.8 months [P]).7 Hence, although there may be clinical utility for administering cytotoxic chemotherapy concurrently with pembrolizumab, it is not clear to what degree the combination truly augments immunotherapy-driven responses or significantly improves OS over pembrolizumab alone.

FACTORING IN CPS

An unplanned, post hoc analysis of KEYNOTE-048 study outcomes among CPS < 1 and CPS 1-19 subgroups provides further insight into the relationship between pembrolizumab efficacy and PD-L1 expression.8 Among the CPS < 1 subgroup (n = 128), median OS with pembrolizumab alone was inferior to cetuximab-chemotherapy (7.9 [P] v 11.3 [C-C] months) and achieved only a 4.5% ORR while pembrolizumab-chemotherapy had a numerically superior median OS compared with the standard arm (11.3 [P-C] v 10.7 [C-C] months [P value = .78932]), an OS hazard ratio of 1.21 (95% CI, 0.76 to 1.94), and inferior ORR (30.8% [P-C] v 39.5% [C-C]).8 Although definitive conclusions cannot be reached with an unplanned analysis of only 128 patients total (14.5% of study participants), these data question the clinical benefit of adding pembrolizumab to chemotherapy for CPS < 1 patients and suggest cetuximab-chemotherapy is a viable option. For a CPS of 1-19 (n = 373), pembrolizumab elicited a modestly higher median OS than cetuximab-chemotherapy (10.8 [P-C] v 10.1 [C-C] months [P value = .12827]) and produced an ORR of 14.5% while pembrolizumab-chemotherapy maintained a statistically significant OS advantage over cetuximab-chemotherapy (12.7 [P-C] v 9.9 [C-C] months [P value = .00726]). These results suggest that either pembrolizumab or pembrolizumab-chemotherapy is a therapeutic option for CPS 1-19 tumors, although the validation of a survival advantage with the latter may make it a preferred approach for eligible patients.

ASSESSING PATIENT FITNESS FOR CHEMOTHERAPY

Beyond tumor-intrinsic considerations, patient fitness is an important factor for clinical decision making. The toxicity profile of pembrolizumab alone was favorable compared with pembrolizumab-chemotherapy with lower rates of treatment-related adverse events (58.3% v 95.7%) and grade ≥ 3 treatment-related adverse events (17.0% v 71.7%).7 It should be noted that the efficacy of pembrolizumab in frail or chemotherapy-ineligible patients with HNSCC, however, is not well understood, and superiority to lower toxicity cytotoxic options has not been established.9 Clinical considerations for chemotherapy eligibility include overall performance status, frailty, or biologic age as assessed by geriatric screening tools,10 chronic infection, cytopenias, or other select comorbidities (eg, uncontrolled coronary artery disease as a contraindication for FU).

CONSIDERING OTHER PUTATIVE BENEFITS OF PEMBROLIZUMAB IN THE FIRST-LINE SETTING

The OS advantage with pembrolizumab-based treatment in KEYNOTE-048 was greater than predicted by just the benefit observed in patients who experienced durable responses. One interpretation is that even after progression on first-line pembrolizumab, a sustained imprint on tumor immunology may increase the degree of benefit achieved with subsequent lines of therapy. Retrospective studies do suggest higher than expected response rates to conventional therapies after progression on ICI treatment.11,12 Post hoc KEYNOTE-048 data analysis revealed that PFS2 (time from random assignment to progression on subsequent line of therapy or death from any cause) was prolonged with pembrolizumab with or without chemotherapy over cetuximab-chemotherapy in the same CPS categories where OS was improved.7 However, only approximately half of the patients in this analysis received subsequent drug therapy, making it difficult to conclude that this observation reflects greater efficacy with second-line therapy after pembrolizumab progression. The primary reason to prioritize administering pembrolizumab in the first-line setting remains ensuring that R/M patients gain access to possible immunotherapy responses and the related OS benefit afforded by PD-1 targeting. More data are needed to clarify the putative carryover impact of first-line pembrolizumab upon subsequent lines of therapy.

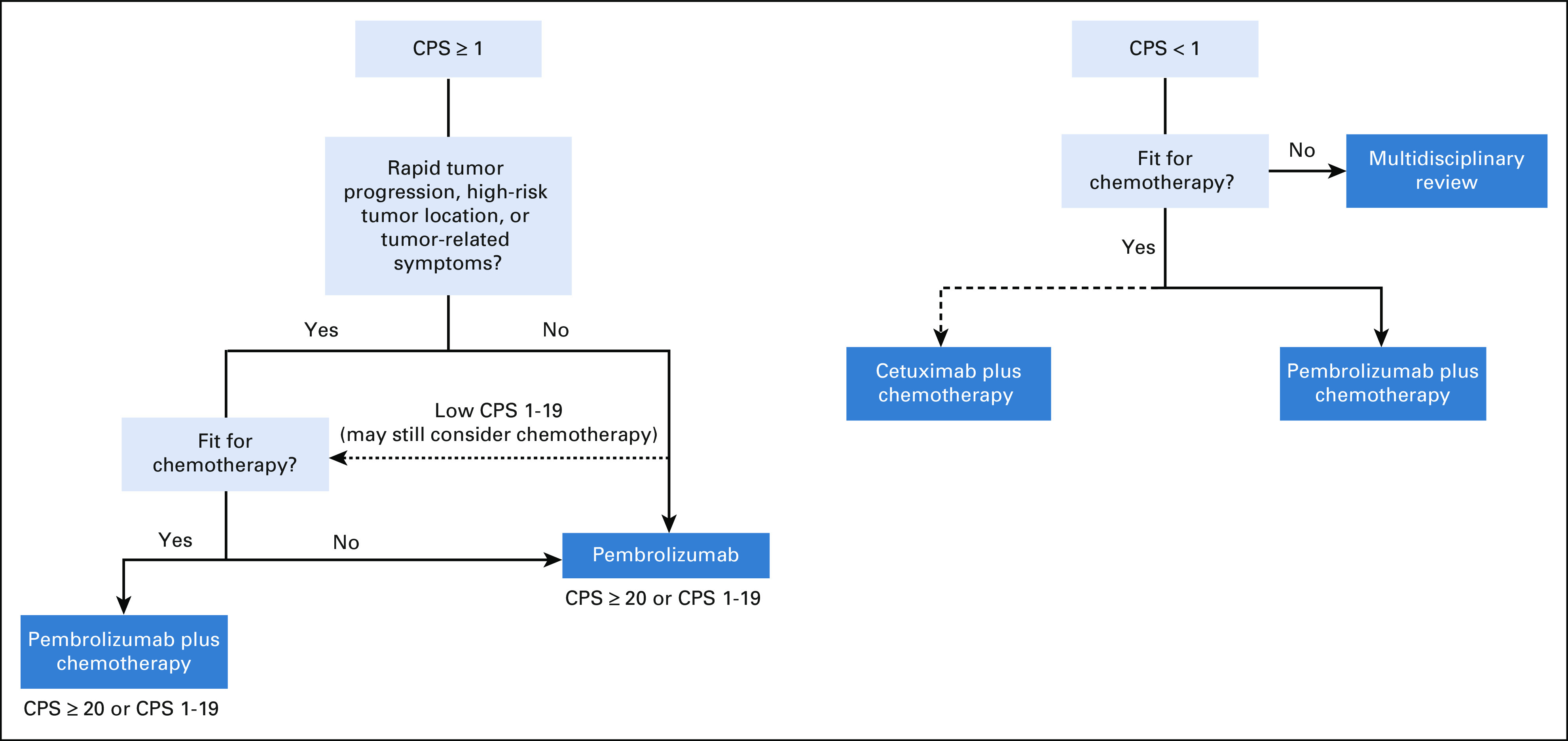

TREATMENT ALGORITHM

Figure 2 summarizes our general treatment algorithm for first-line therapy in patients with R/M HNSCC in the context of the KEYNOTE-048 planned and unplanned analyses. The CPS subgroups referenced (CPS ≥ 20, CPS 1-19, CPS < 1) are those for which clinical data have been analyzed, but these should not be considered absolute CPS cutoffs since pembrolizumab efficacy is not strictly defined by these categories13 and some of the analyses of these subgroups were unplanned with small sample sizes.8 Tumor heterogeneity and random sampling may also produce CPS values that are not reflective of overall tumor biology, as was encountered in our case example. The decision algorithm reflects that for patients with CPS ≥ 1 tumors, either pembrolizumab alone or pembrolizumab-chemotherapy are reasonable options on the basis of the primary KEYNOTE-048 survival analysis. For chemotherapy-fit patients in whom achieving tumor regression is a priority, pembrolizumab-chemotherapy is preferred; other patients may be considered for pembrolizumab monotherapy. For CPS 1-19 patients, pembrolizumab-chemotherapy may garner greater consideration in fit patients. Importantly, patient preference for how to balance treatment toxicity and efficacy with therapy selection must be prioritized in the palliative treatment setting, particularly given the more favorable adverse event profile of pembrolizumab without chemotherapy. What KEYNOTE-048 does not address is the potential utility of a sequential approach, such as starting patients on pembrolizumab alone and adding chemotherapy later if objective response is not observed. For CPS < 1, cetuximab or pembrolizumab combined with chemotherapy is indicated. Given a higher response rate and lower risk of disease progression, we prefer cetuximab-based therapy for CPS < 1 cases when acutely achieving tumor response is a priority and for HPV-negative tumors against which cetuximab may be particularly effective.14 CPS < 1 patients who are ineligible for chemotherapy are clinically challenging cases who should undergo multidisciplinary review to identify optimal treatment approaches.

FIG 2.

First-line treatment algorithm for patients with platinum-sensitive, recurrent or metastatic HNSCC. CPS, combined positive score; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.

OUR APPROACH TO MANAGEMENT

In this case example, the patient presented with de novo metastatic HNSCC. After a multidisciplinary evaluation by our surgery, radiation oncology, speech, and medical oncology services, the decision was made to administer systemic therapy with palliative intent, reserving radiation to consolidate an excellent therapeutic response or to palliate tumor-related symptoms later. The discordant CPS of 0 in the primary versus CPS of 8 in the lung metastasis illustrates the heterogeneity in PD-L1 expression encountered with limited tumor sampling. The implication of the different CPS values was discussed with the patient, including the perspective that a CPS of 0 would diminish enthusiasm for pembrolizumab-based therapies while favoring consideration for cetuximab-based treatment (although cetuximab efficacy may be diminished in HPV-positive disease14). Although the CPS of 8 may be indicative of a lower likelihood of pembrolizumab benefit, consideration of all the clinical features and the patient's preference for immunotherapy led to the decision to proceed with pembrolizumab-based treatment. Given the advanced, muscle-invasive primary tumor with lymph node metastasis encasing the carotid artery that could cause worsening pain, dysphagia, trismus, or catastrophic carotid rupture with further tumor progression (Fig 1), treatment with pembrolizumab-chemotherapy was recommended.15 The patient also had modestly compromised renal function at presentation, leading to a choice of carboplatin over cisplatin. Paclitaxel was used instead of infusional FU because data with platinum-based combinations suggest that it may provide better tolerability with equivalent efficacy.16 Post-immunotherapy studies have also reported outsized taxane benefit, suggesting the possibility that this class could enhance immunotherapy response.11

The patient was treated with carboplatin area under the curve 4-5 on day 1, paclitaxel 80 mg/m2 once daily on days 1 and 8, and pembrolizumab 200 mg on day 1 once every 21 days. After three cycles of therapy, imaging revealed marked contraction of the oropharyngeal primary, conglomerate left neck disease, and the pulmonary nodules (Fig 1). Positron-emission tomography revealed no evidence of fluorodeoxyglucose-avid malignancy. Chemoradiation with cisplatin 40 mg/m2 once every week was administered (renal function improved after treatment initiation) to the oropharynx for definitive treatment of the primary site. Within the first 2 weeks of chemoradiation, the patient experienced dizziness, weakness, and mild confusion that was accompanied by orthostatic hypotension and hyponatremia. Detection of low circulating cortisol and adrenocorticotropic hormone levels suggested pembrolizumab-induced adrenal insufficiency, subsequently confirmed with a cosyntropin stimulation test (imaging demonstrated no pituitary lesion). Treatment with hydrocortisone resolved the patient's symptoms, and the patient completed 60 Gy radiation therapy in 30 fractions with a total dose of 240 mg/m2 cisplatin.

After chemoradiation, repeat chest imaging revealed further regression of subcentimeter lung nodules with near complete response (CR). On KEYNOTE-048, patients who achieved CR with ≥ 24 weeks of treatment were given the option of stopping therapy.7 Since our patient only received 12 weeks of pembrolizumab, it was restarted 2 months after radiation. However, after one dose the patient developed worsening fatigue, dysphagia, and new-onset dyspepsia. Endoscopic gastric biopsies revealed striking gastric inflammation with marked lymphoplasmacytic and neutrophilic infiltration, compatible with immunotherapy associated gastritis, which was treated with high-dose steroids. Pembrolizumab has been discontinued, and the patient continues to have a near CR now 10 months out from his initial metastatic HNSCC diagnosis.

Delineating the contribution of PD-1 targeting versus chemotherapy to the observed benefit in this case cannot be definitively determined. Recent data suggest that development of immune-related adverse events may be associated with a higher likelihood of clinical benefit with ICI therapy.17 Secondary adrenal insufficiency and gastritis are uncommon pembrolizumab-related adverse events occurring in < 1% of patients, perhaps suggesting that the native immunologic milieu was uniquely poised for activation with PD-1 inhibition in this patient. Additionally, next-generation sequencing of the lung metastasis that resulted after initiation of therapy revealed the tumor possessed 9.1 mutations/megabase (Mb), just under the ≥ 10 mutations/Mb threshold that has been used to define high tumor mutation burden (TMB) for pembrolizumab in solid tumors.18 Given that higher TMB has been associated with pembrolizumab benefit in patients with HNSCC and the TMB cutoffs that enrich for immunotherapy benefit can vary among different tumor histologies,19 it is possible that this patient's TMB produced a sufficient number of tumor neoantigens against which a pembrolizumab-induced immune response could be targeted. These proposed biomarker associations and mechanisms of action remain speculative or only loosely predictive, highlighting the need to develop composite predictive biomarker panels that can more effectively identify patients who will experience ICI benefit.

See accompanying article on page 790

SUPPORT

Dr A. L. Ho is supported by the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA008748.

AUTHOR'S DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Immunotherapy, Chemotherapy, or Both: Options for First-Line Therapy for Patients With Recurrent or Metastatic Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma

The following represents disclosure information provided by the author of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol Myers Squibb, Eisai, Genzyme, Novartis, Merck, Sun Pharma, Regeneron, TRM Oncology, Ayala Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Sanofi, CureVac, Prelude Therapeutics, Kura Oncology, McGivney Global Advisors, Rgenta, AffyImmune Therapeutics, Exelixis, Cellestia Biotech, InxMed, Elevar Therapeutics

Speakers' Bureau: Medscape, Omniprex America, Novartis

Research Funding: Lilly, Genentech/Roche, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Kura Oncology, Kolltan Pharmaceuticals, Eisai, Bristol Myers Squibb, Astellas Pharma, Novartis, Merck, Pfizer, Ayala Pharmaceuticals, Allos Therapeutics, Daiichi Sankyo, Elevar Therapeutics, Novartis

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Janssen Oncology, Merck, Kura Oncology, Ignyta, Ayala Pharmaceuticals, Klus Pharma

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A: Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin 72:7-33, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. : Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 68:394-424, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vermorken JB, Mesia R, Rivera F, et al. : Platinum-based chemotherapy plus cetuximab in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med 359:1116-1127, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen EEW, Soulières D, Le Tourneau C, et al. : Pembrolizumab versus methotrexate, docetaxel, or cetuximab for recurrent or metastatic head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma (KEYNOTE-040): A randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet 393:156-167, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferris RL, Blumenschein G, Fayette J, et al. : Nivolumab for recurrent squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med 375:1856-1867, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burtness B, Harrington KJ, Greil R, et al. : Pembrolizumab alone or with chemotherapy versus cetuximab with chemotherapy for recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (KEYNOTE-048): A randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet 394:1915-1928, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harrington KJ, Burtness B, Greil R, et al. : Pembrolizumab with or without chemotherapy in recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: Updated results of the phase III KEYNOTE-048 study. J Clin Oncol 41:790-802, 2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burtness B, Rischin D, Greil R, et al. : Pembrolizumab alone or with chemotherapy for recurrent/metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in KEYNOTE-048: Subgroup analysis by programmed death ligand-1 combined positive score. J Clin Oncol 40:2321-2332, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grünwald V, Graeven U, Ivanyi P, et al. : 912P Results of a randomized phase II study comparing pembrolizumab with methotrexte in elderly, frail or cisplatin-ineligible patients with relapsed or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (RM-SCCHN) (ELDORANDO-AIO-KHT-0115). Ann Oncol 32:S807-S808, 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Szturz P, Cristina V, Herrera Gomez RG, et al. : Cisplatin eligibility issues and alternative regimens in locoregionally advanced head and neck cancer: Recommendations for clinical practice. Front Oncol 9:464, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guiard E, Clatot F, Even C, et al. : Impact of previous nivolumab treatment on the response to taxanes in patients with recurrent/metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Eur J Cancer 159:125-132, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saleh K, Daste A, Martin N, et al. : Response to salvage chemotherapy after progression on immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Eur J Cancer 121:123-129, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haddad RI, Seiwert TY, Chow LQM, et al. : Influence of tumor mutational burden, inflammatory gene expression profile, and PD-L1 expression on response to pembrolizumab in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer 10:e003026, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szturz P, Seiwert TY, Vermorken JB: How standard is second-line cetuximab in recurrent or metastatic head and neck cancer in 2017? J Clin Oncol 35:2229-2231, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saada-Bouzid E, Defaucheux C, Karabajakian A, et al. : Hyperprogression during anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy in patients with recurrent and/or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol 28:1605-1611, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guigay J, Auperin A, Fayette J, et al. : Cetuximab, docetaxel, and cisplatin versus platinum, fluorouracil, and cetuximab as first-line treatment in patients with recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous-cell carcinoma (GORTEC 2014-01 TPExtreme): A multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 22:463-475, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foster CC, Couey MA, Kochanny SE, et al. : Immune-related adverse events are associated with improved response, progression-free survival, and overall survival for patients with head and neck cancer receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer 127:4565-4573, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marabelle A, Fakih M, Lopez J, et al. : Association of tumour mutational burden with outcomes in patients with advanced solid tumours treated with pembrolizumab: Prospective biomarker analysis of the multicohort, open-label, phase 2 KEYNOTE-158 study. Lancet Oncol 21:1353-1365, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Samstein RM, Lee CH, Shoushtari AN, et al. : Tumor mutational load predicts survival after immunotherapy across multiple cancer types. Nat Genet 51:202-206, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]