Abstract

This study aimed to systematically review research findings regarding the relationship between adult friendship and wellbeing. A multidimensional scope for wellbeing and its components with the use of the PERMA theory was adopted. A total of 38 research articles published between 2000 and 2019 were reviewed. In general, adult friendship was found to predict or at least be positively correlated with wellbeing and its components. In particular, the results showed that friendship quality and socializing with friends predict wellbeing levels. In addition, number of friends, their reactions to their friend's attempts of capitalizing positive events, support of friend's autonomy, and efforts to maintain friendship are positively correlated with wellbeing. Efforts to maintain the friendship, friendship quality, personal sense of uniqueness, perceived mattering, satisfaction of basic psychological needs, and subjective vitality mediated this relationship. However, research findings highlighted several gaps and limitations of the existing literature on the relationship between adult friendship and wellbeing components. For example, for particular wellbeing components, findings were non-existent, sparse, contradictory, fragmentary, or for specific populations only. Implications of this review for planning and implementing positive friendship interventions in several contexts, such as school, work, counseling, and society, are discussed.

Keywords: friendship, wellbeing, adults, PERMA, systematic review

1. Introduction

1.1. Adult friendship

Adult friendship is conceptualized as a voluntary, reciprocal, informal, restriction-free, and usually long-lasting close relationship between two unique partners (Wrzus et al., 2017; Fehr and Harasymchuk, 2018).

Mendelson and Aboud (1999) defined six functional components of adult friendship that determine its quality. The first friendship function is stimulating companionship, which refers to joint participation in recreational and exciting activities (Fehr and Harasymchuk, 2018). Friends, unlike acquaintances, interact in a more relaxed and carefree way, use more informal language, make jokes, and tease each other (Fehr, 2000).

Existing research literature has mainly focused on the second function of friendship, namely help or social support (Wallace et al., 2019). Three forms of social support have been identified: (a) emotional support, which is conceptualized as acceptance, sympathy, affection, care, love, encouragement, and trust (Li et al., 2014); (b) instrumental support, which is defined as provision of financial assistance, material goods, services, or other kinds of help (Nguyen et al., 2016); and (c) informational support, which refers to provision of advice, guidance, and useful information (Wood et al., 2015).

The third function of adult friendship is emotional security, which refers mainly to the sense of safety offered by friends in new, unprecedented and threatening situations (Fehr and Harasymchuk, 2018). Research has shown that friends can significantly reduce their partners' stress caused by negative life events (Donnellan et al., 2017).

The fourth function of adult friendship is reliable alliance, which is defined as the constant availability and mutual expression of loyalty (Wrzus et al., 2017). At the core of reliable alliance lie the concepts of trust and loyalty (Miething et al., 2017).

Self-validation is the fifth function of adult friendship. It concerns the individuals' sense that their friends provide them with encouragement and confirmation, thus helping them to maintain a positive self-image (Fehr and Harasymchuk, 2018).

Finally, the sixth function of adult friendship is intimacy, which refers to self-disclosure procedures (e.g., the free and honest expression of personal thoughts and feelings; Fehr and Harasymchuk, 2018). It is necessary for both friends to reciprocally reveal “sensitive” information and react positively to the information that their partner discloses to them; in this way, feelings of trust can be developed and consolidated (Hall, 2011).

Adults differ significantly not only with regard to friendship quality, but also to the number of friends one has and the hierarchy of friendships (Demir, 2015). Most individuals maintain small networks of long-term and close friends (Wrzus et al., 2017). Empirical research shows that individuals report an average of three close friends (Christakis and Chalatsis, 2010). Also, individuals make fine distinctions between best, first closest friend, second closest friend, other close friendships, and casual friendships (Demir and Özdemir, 2010). These differentiations reflect the ratings of these friendships regarding several quality indicators (Demir et al., 2011b). The present systematic review of the literature will cover multiple aspects of friendship as predictors of wellbeing, namely friendship quality indicators, number of friends, and friendship ratings.

1.2. The concept of wellbeing

Wellbeing is a central issue in the field of positive psychology (Heintzelman, 2018). It is a multifaceted construct (Forgeard et al., 2011) and there are several theoretical approaches of its components (Martela and Sheldon, 2019). We define wellbeing as a broad construct that involves the presence of indicators of positive psychological functioning, such as life satisfaction and meaning in life, and the absence of indicators of negative psychological functioning, e.g., negative emotions or psychological symptoms (Houben et al., 2015). This conceptualization captures both hedonic elements of wellbeing (Diener, 1984), that involve pleasure, enjoyment, satisfaction, comfort, and painlessness (Huta, 2016) and eudaimonic elements (Ryff, 1989), that include concepts like meaning, personal growth, excellence, and authenticity (Huta and Waterman, 2014). Our definition on wellbeing also involves the components of subjective wellbeing (Diener et al., 1999), psychological and social wellbeing (Ryff, 1989) and general wellbeing (Disabato et al., 2019). Finally, this definition encompasses the two different approaches on wellbeing, which are based on the mental illness model (Keyes, 2005) and on positive psychology principles (Seligman, 2011).

Several attempts have been made to synthesize the aforementioned models. In this systematic review of the literature, we used Seligman's (2011) PERMA theory to organize our findings. Seligman (2011) argued that individuals can flourish and thrive if they manage to establish the following five pillars of their lives: positive emotions (P), engaging in daily activities (E), positive relationships (R), a sense of meaning in life (M), and accomplishments (A).

According to the Broaden-and-Build theory (Fredrickson, 2001), when individuals experience positive emotions, their repertoire of thoughts and actions broaden (Fredrickson and Branigan, 2005). The broadening effect activates an upward spiral, resulting in the experience of new and deeper positive emotions (Fredrickson and Joiner, 2002). This, in turn, leads to building of resources, which last over time and act as a protective shield against adversity (Tugade and Fredrickson, 2004). Finally, experiencing positive emotions seems to undo the unpleasant effects of experiencing negative emotions (Fredrickson et al., 2000). All the above mechanisms facilitate the physical and psychological wellbeing of individuals (Kok et al., 2013).

Engagement describes a positive state of mind in which individuals are fully present psychologically and channel their interest, energy, and time into physical, cognitive, and emotional processes to achieve or create something (Butler and Kern, 2016). Engagement is substantially linked to the experience of flow, which is conceptualized as the psychological focus on an activity, accompanied by an experience of high intrinsic motivation and sense of control, and resulting in optimal functioning (Csikszentmihalyi, 2009). High levels of engagement are associated with various indices of wellbeing, such as increased levels of experiencing positive emotions and life satisfaction (Fritz and Avsec, 2007) and decreased levels of anxiety and depression over time (Innstrand et al., 2012).

Positive close relationships with family, friends and other significant people are also beneficial. They are found to be associated with emotional and instrumental support, intimacy, trust, increased sense of belonging and other protective indices of physical and psychological wellbeing (Carmichael et al., 2015; Mertika et al., 2020; Mitskidou et al., 2021).

Meaning in life reflects the individual's sense that life has coherence, purpose, and significance so that it is worth-living (Martela and Steger, 2016). Research findings show that the presence of meaning in life enhances wellbeing, because it entails high levels of positive emotions and life satisfaction as well as low levels of negative psychological and physical conditions (Pezirkianidis et al., 2016a,b, 2018; Galanakis et al., 2017).

Accomplishments in all domains of life are recognized and rewarded by society; this reinforces the individuals' desire to succeed (Nohria et al., 2008). However, accomplishments are not restricted to great achievements in life but also include the fulfillment of daily personal ambitions and the achievement of everyday goals. These minor accomplishments have been found to contribute to the wellbeing of individuals (Butler and Kern, 2016).

1.3. Associations between adult relationships and wellbeing components

Positive, supportive relationships predict higher physical and psychological wellbeing levels more than any other variable (Vaillant, 2012). In particular, integrating people into support networks provides them with the necessary resources to successfully deal with depression, anxiety, loneliness, alcohol overdose and many other physical and mental health difficulties (Christakis and Fowler, 2009, 2013). In addition, the chances of individuals' happiness increase when they are associated with a happy person. Therefore, happiness seems to be transmitted through positive relationships (Fowler and Christakis, 2008).

Moreover, research findings show that perceived support from positive relationships is associated with experiencing more positive emotions (Kok et al., 2013), sense of calm and security (Kane et al., 2012), and presence of meaning in life (Hicks and King, 2009).

In particular, adult friendship is a valuable personal relationship (Demir, 2015), which contributes in various ways to individuals' wellbeing (Demir et al., 2007), and significantly fulfills the fundamental human need for social interaction and belonging (Lyubomirsky, 2008). The quality of adult friendship is related to wellbeing and the experiencing of positive emotions (Demir et al., 2007; Secor et al., 2017; Pezirkianidis, 2020). In addition, existing literature shows that a close adult friendship is related to personal achievement and engagement to projects, which promote meaning in life (Green et al., 2001; Koestner et al., 2012).

1.4. Gaps in the literature on the relationship between adult friendship and wellbeing

Even though the relationship between friendship and wellbeing has been extensively studied in children (e.g., Holder and Coleman, 2015), adolescents (e.g., Raboteg-Saric and Sakic, 2014), and the elderly (e.g., Park and Roh, 2013), it is not yet fully understood how the various elements of adult friendship are related to wellbeing. The main reason for this is that adulthood consists of many different life periods, from young to late adulthood, during which there are fluctuations in the network of friends and changes in friendship quality (Bowker, 2004).

In fact, most of the empirical research on the relationship between adult friendship and wellbeing focuses on the effect of adult friendship on one-dimensional indices of wellbeing, such as happiness or life satisfaction (Demir et al., 2007). It is worth-noting that research is mainly conducted with university student samples, which limits generalizability to older age groups (Demir, 2015).

1.5. The present study

This study aims to systematically review the research literature on the relationship between adult friendship and wellbeing as well as its components, in order to shed more light on the nature of this relationship and the mechanisms that underlie it. More specifically, we will review empirical studies which examined the relationship of quantitative and qualitative indices of adult friendship with wellbeing within the framework of PERMA theory (Seligman, 2011). Therefore, the relationship between adult friendship and overall wellbeing as well as each of its PERMA components will be studied.

Five research questions have been formulated: (a) Which adult friendship variables are mostly associated with wellbeing? (b) Which adult friendship variables predict wellbeing levels based on longitudinal studies? (c) Are there mediating and/or moderating variables in the association between adult friendship and wellbeing? (d) Are there individual differences on the associations between adult friendship and wellbeing? (e) Does adult friendship associate with specific components of wellbeing on the basis of PERMA theory?

2. Methods

2.1. Criteria of suitability/inclusion of bibliographic sources

We searched for sources reporting empirical research with quantitative and qualitative design using samples ranging in age from 18 to 65 years. Articles were published in scientific journals between 2000 and 2019, since we decided to exclude studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, when the relationships with significant others were negatively affected. We included articles written in English and accompanied by a digital identifier (DOI). Book chapters, reviews and gray literature were excluded.

2.2. Search strategy, source selection and data extraction

We searched for resources in the following search engines: Google Scholar, PsycNET, and Scopus. The following algorithm was used to search for the literature sources: “friends” OR “friend” OR “friendship” OR “friendships” AND “wellbeing” OR “wellbeing” OR “psychological wellbeing” OR “psychological wellbeing” OR “happiness” OR “flourish” OR “flourishing” OR “psychological flourish” OR “psychological flourishing” OR “subjective wellbeing” OR “subjective wellbeing” OR “positive emotions” OR “positive emotion” OR “positive affect” OR “engagement” OR “flow” OR “psychological flow” OR “positive relationship” OR “positive relationships” OR “social support” OR “meaning” OR “meaning of life” OR “meaning in life” OR “life meaning” OR “life purpose” OR “purpose of life” OR “purpose in life” OR “achievement” OR “achievements” OR “accomplishment” OR “accomplishments” OR “performance” OR “success” AND “adult” OR “adults”.

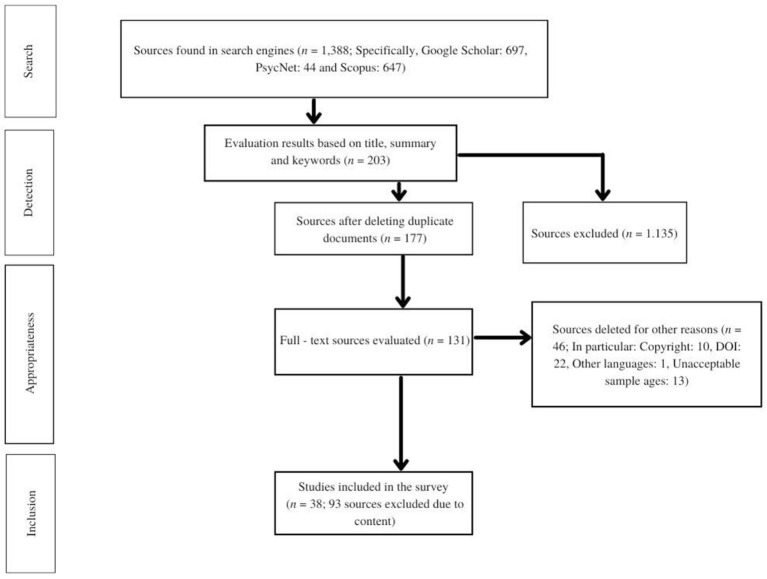

The studies were initially selected by two independent evaluators on the basis of their abstract, title and keywords (phase 1). The evaluators were both psychologists and one of them is a researcher, experienced on systematic reviews. The total number of abstracts tested was 1,388. Any paper considered relevant at least by one of the two evaluators was eligible for full-text inspection. The agreement between the evaluators at the first phase was 78%. Thus, 203 articles were included for full-text evaluation (phase 2).

During the second phase of the evaluation process, we first checked the sources for duplication and fulfilling the inclusion criteria. The exclusion criteria were the same for both phases. As a result, we removed 33 duplicate documents, 10 articles that their full-text could not be found due to copyright, 22 articles that did not have a DOI, and one article not written in English. In addition, 13 studies were rejected because the sample's age was not within the set limits. Next, the two evaluators independently inspected the full-text of the remaining articles (n = 131). As a result, 93 articles were excluded because their content was not relevant to the aims of the study. The agreement between the evaluators at this phase was 96%; if the decision was not unanimous after further discussion, it was excluded by the study. Thus, in total, 38 studies were eligible for the review (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of search strategy and source selection.

3. Results

From the selected 38 studies, two followed a qualitative design, nine were longitudinal, two had a mixed cross-sectional and experimental design and the rest of them were based on a cross-sectional design. Most of them (n=28) used a sample of young adults, mainly university students (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Findings of the systematic literature review regarding the associations between adult friendship and wellbeing.

| References | Study design | Sample (n, male %, Mage) | Independent variables | Dependent variables (PERMA variable) | Measures | Key statistical results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Akin and Akin (2015) | CS | USA university students (271, 46%, N/A) | FQ, Subjective vitality | H (WB) | FQS, SHS, SVS | FQ positively correlates with H (r = 0.29). Subjective vitality partially mediates this relationship (β = 0.33). |

| 2. Almquist et al. (2014) | Q | Swedish adults born in 1990 (1.289, 50.19%, 19) | FQ, Trust, Self-disclosure | MWB (WB) | Interview via phone | Emotional SS, i.e., FQ (B = 3.59), trust (B = 2.62), and self–disclosure (B = 1.61), positively associate with MWB. |

| 3. Brannan et al. (2013) | CS | College students: Iran (151, 59%, 22), Jordan (161, 57%, 21), USA (234, 35%, 25) | SS-Fr | LS, PE (WB, PE) | PSS-Fr, SWLS, PANAS | In USA sample PSS–Fr associates with LS (β = 0.13) and PE (β = 0.26) levels, in the Jordanian sample PSS–Fr associates with PE (β = 0.21) but no significant relationships found in Iran sample. |

| 4. Cable et al. (2012) | L | Adults born in GB in 1958 (6.681, 47.43%, T1: 42, T2: 45, T3: 50) | SNS | PWB (WB) | SNS-SI, Warwicke-Edinburgh MWBS | Smaller friendship networks at age 45 predict lower levels of PWB 5 years later (B = −1.30 to −4.72 for less than five friends). |

| 5. Carmichael et al. (2015) | L | USA adults (133, 44.36%, T1: 20, T2: 30, T3: 50) | FQ | PWB (WB) | Social Network Index, FQ-SI, PWB | FQ at 20s predicts FQ at 30s (β = 0.29 to.33), while FQ at 30s predict PWB at 50s (β = 0.38). |

| 6. Carr and Wilder (2016) | CS | USA adults (224, 46%, 21.69) | Risks of seeking SS-Fr | FS, Relational closeness (R) | Risks of seeking social support (5-item scale), Relationship Assessment Scale-FR, Interpersonal Solidarity Scale | Individuals perceiving high risks in seeking social support from friends correlates to lower levels of interpersonal closeness (r = −0.38) and friendship satisfaction (r = −0.48). |

| 7. Chen et al. (2015) | EXP, CS | University students (study 1: 54 friendship pairs, 24%, 18.56; study 2: 131, 19.85%, 19; study 3: 332, 24.69%, 19) | FQ | SS (R) | Social Support scale, Relationship Quality Scale, Relationship Satisfaction Index | Perceived FQ predicts received support during adversity (β = 0.26) and emotional–focused support among European Americans (β = 0.37). Also, FQ more strongly associates with support provision among European Americans (β = 0.56) than Japanese (β = 0.24), while FQ associates with higher levels of attentiveness (β = 0.42) and companionship (β = 0.38) among Asian Americans than European Americans (β = 0.20 and 0.18, respectively). |

| 8. Cyranowski et al. (2013) | CS | USA adults (692, 43.4%, 43.97) | Companionship with friends | SS, Loneliness, Social distress (R) | UCLA-R, Interpersonal Support Evaluation List, Negative Interaction Scale | Companionship with friends correlates with higher levels of SS from others (r = 0.77) and lower levels of loneliness (r = −0.81) and social distress (−0.27). |

| 9. Demir and Davidson (2013) | CS | USA university students (4.283, 26.38%, 18.81) | PRCA, PM, NS | PE (PE) | PRCAS, MTOQ, PANAS, NS-FR | PM (r = 0.32), NS–FR (r = 0.33) and PRCA (r = 0.19) positively correlate with PE. NS–FR explains PE levels of men (β = 0.49), while PM (β = 0.09), NS–FR (β = 0.33) and PRCA (β = 0.08) explain PE levels of women. |

| 10. Demir et al. (2007) | CS | USA university students (280, 31.43%, 22.56) | FQ | LS, PE, H (WB, PE) | Network of Relationships Inventory, SWLS, PANAS | The quality of best (r = 0.20) and first close friendships (r = 0.19) positively correlates with LS and H (r = 0.26 and 0.19, respectively), but not with experiencing of PE. Stimulating companionship in best (r = 0.29) and first close friendship (r = 0.22) associates with H. |

| 11. Demir et al. (2017) | CS | USA university students (2,997, 30%, 19.15) | FQ, PRCA, PNS | H (WB) | MFQ-FF, PRCAS, NSS, SHS, SWLS, PANAS | PRCA and FQ positively correlate to H (r = 0.19 to.27 and r = 0.26 to.31, respectively). FQ mediates the relationship of PRCA with H in best friendships (β = 0.29 for men and 0.53 for women) and, similarly, PNS in same–sex friendships (β = 0.65 among men and 0.52 amongst women). No differences of gender and same/different–sex friendships were found. |

| 12. Demir et al. (2019) | CS | USA university students (685, 33%, 18.73) | FM, PRCA | SWB, H (WB) | FMS, PRCAS, SWLS, SHS, PANAS | PRCA and FM positively correlates to SWB (r = 0.19 and 0.37) and H (r = 0.21 and 0.31). FM mediates the relationship of PRCA with SWB (β = 0.11 for men and 0.16 for women) and H (β = 0.08 for men and 0.14 for women). No gender differences found. |

| 13. Demir et al. (2013a) | CS | University students: Turkey (287, 46.69%, 22.22), USA (268, 41.42%, 21.37) | FQ, PRCA | H (WB) | MFQ-FF, PRCAS, SHS | Both in Turkish and Americans FQ and PRCA positively associate with H (r = 0.35 and 0.28; r = 0.18 and 0.16, respectively). FQ mediates the relationship of PRCA and H in both samples (β = 0.03 for Turkish and 0.04 for Americans). |

| 14. Demir et al. (2012a) | CS | University students: Malaysia (154, N/A, 22.10), USA (211, N/A, 21.95) | FQ | H, Social skills (WB, R) | MFQ-FF, Interpersonal Competence Questionnaire, SHS | FQ both among Americans and Malaysians associates with social skills (β = 0.24 and 0.20) and H (β = 0.33 and 0.38, respectively) and mediates the relationship between social skills and H (β = 0.11 for Americans and 0.15 for Malaysians). |

| 15. Demir and Özdemir (2010) | CS | USA university students (400, 29.25%, 22.39) | FQ, PNS | H (WB) | MFQ-FF, NSS, PANAS | FQ positively correlates with to PNS (r = 0.69) and H (r = 0.25). PNS mediates the relationship of FQ with H in the three closest friendships (β = 0.26). |

| 16. Demir et al. (2011a) | CS | USA university students (study 1: 256, 32.81%, 20.34; study 2: 498, 21.28%, 19.10; study 3: 299, 20.4%, 19.81, study 4: 175, 30.85%, 20.57) | FAS, FM | H, LS, PE (WB, PE) | FASQ, FMS, SHS, SWLS, PANAS | FAS (r = 0.21 to.24) and FM (r = 0.41 to.48) positively correlate with H, PE (r = 0.18 and 0.43, respectively), and LS (r = 0.27 and 0.35, respectively). FM fully mediates the relationship between FAS and H in close and best friendships (β = 0.51). |

| 17. Demir et al. (2011b) | CS | USA university students (study 1: 212, 32.07%, 23.99) | FQ, PM | H (WB) | MFQ-FF, MTOQ, PANAS | PM (r = 0.36) and FQ (r = 0.21) positively correlate with H. PM mediates the relationship between FQ and H regarding the three closest friendships (β = 0.16 to.21). |

| 18. Demir et al. (2012b) | CS | University students: Turkey (296, N/A, 21.14), USA (273, N/A, 21.80) | FQ, PM | H (WB) | MFQ-FF, MTOQ, PANAS | FQ and PM positively correlate to H among Turkish and Americans (r = 0.29 and 0.18; r = 0.21 and 0.33, respectively). Among Americans, PM mediates the relationship of FQ and H, whilst among Turkish FQ mediates the relationship of PM with H. |

| 19. Demir et al. (2013b) | CS | USA university students (2,429, 27%, 18.8) | FQ, Sense of uniqueness | H (WB) | MFQ-FF, PSU, PANAS, SWLS, SHS | FQ positively correlates with SoU (r = 0.34 to.38) and H (r = 0.29 to.32). SoU mediates the relationship between FQ and H (β = 0.38 to.41). |

| 20. Demir and Weitekamp (2007) | CS | USA university students (423, 29.07%, 22.53) | FQ | H, LS, PE (WB, PE) | MFQ-FF, SWLS, PANAS | FQ positively correlates with PE (r = 0.25), LS (r = 0.18), and H (r = 0.26). |

| 21. Derdikman-Eiron et al. (2013) | L | Norwegian adults (1,346, 38.41%, T1: 14.4, T2: 26.9) | Frequency of meeting friends | SS-Fr (R) | Frequency of meeting friends-SI, SS-Fr (2-item scale) | Frequency of meeting friends during adolescence predicts SS–Fr among young adults (OR = 1.33). |

| 22. Griffin et al. (2006) | CS | USA black and white women (290, 0%, 37.8) | SS-Fr satisfaction, Friend network size | LS (WB) | SS questionnaire, LS scale | SS–Fr satisfaction (β = 0.23) and friendship network (β = 0.22) positively associate with LS. No racial differences found. |

| 23. Heck and Fowler (2007) | L | USA secondary and high school students, who became adults seven years later (14.332, 50.9%, N/A) | NF | Participation in community activities (E) | Social network measure, Individual interview | NF of secondary and high school students predicts engagement levels in community activities during young adulthood (β = 0.05). |

| 24. Helliwell and Huang (2013) | CS | Canadian adults (5,025, 49%, 44.93) | NF | LS, H (WB) | NF-SI, Cantril's Self-Anchoring Ladder | NF positively associate with LS and H (β = 0.29 and 0.37, respectively), especially for single, divorced, separated, or widowed individuals. |

| 25. Huxhold et al. (2013) | L | German adults (2.830, 50.8%, 53.3) | SC-Fr | LS, PE (WB, PE) | SC-Fr scale, SWLS, PANAS | SC–Fr positively predicts LS and PE levels 6 years later (β = 0.08 and 0.08). |

| 26. Koestner et al. (2012) | L | 105 dyads of friends (210, 0%, 20.19) | FAS | SWB, FQ, Goal progress (WB, R, A) | FQ (5-item scale), SWLS, Goal descriptions and progress ratings | FAS positively correlates with FQ (r = 0.60), goal progress (r = 0.28), and SWB (r = 0.37). FQ positively correlates with SWB (r = 0.34). FAS predicts increases in FQ (β = 0.43), SWB (β = 0.21), and goal progress (β = 0.22) 3 months later. |

| 27. Lemay and Clark (2008) | CS | USA (study 1: 96 adults, 15.6%, 34.89; study 2: 86 university students, 38.37%, 21; study 3: 60 pairs of friends, 16.67%, 21; study 4: 96 couples, 50%, 26.5; study 5: 153 adults, 33.33%, 24.63) | Individual's communal responsiveness | SS-Fr, Self-disclosure, Friend's communal responsiveness (R) | Responsiveness (own and friend's), Inventory of Social Supportive Behaviors, SC-Fr-SI, Self-Disclosure Index | Adults' own felt communal responsiveness toward a friend appeared to bias their perceptions of the friend's communal responsiveness (r = 0.60), which in turn is associated to own and partner's self–disclosure (r = 0.47 and 0.49), evaluation of the friend (r = 0.27), and support provision (r = 0.40). |

| 28. Li and Kanazawa (2016) | CS | USA adults (15.197, N/A, 21.96) | SC-Fr | LS (WB) | SC-Fr-SI, LS-SI | Frequency of SC–Fr positively associates with LS (β = 0.03), when controlling for marital status. |

| 29. Miething et al. (2016) | L | Swedish adults (772, 50.90%, 23) | Friendship network quality (FNQ) | PWB, FNQ (WB, R) | FNQ-SI, PWB (6-item scale) | FNQ correlates with PWB of young adults both for males and females (r = 0.15 and 0.17). FNQ during late adolescence predicts FNQ (β = 0.37 for males and 0.30 for females) and PWB (β = 0.15 and 0.17, respectively) of young adults. |

| 30. Morelli et al. (2015) | Q | 49 dyads of same-sex friends (98, 51%, N/A) | Practical and emotional support | SWB (WB) | Personal diaries | Emotional support is associated to wellbeing levels of the actor during time. Practical support is associated to wellbeing of both friends only when the actor is emotionally engaged. |

| 31. Morry and Kito (2009) | CS | USA university students (253, 42.68%, 19.8) | FQ, FS | Relationship supportive behaviors, Relational self (R) | Relational-Interdependent Self-Construal Scale, MFQ-FF-RA, Self-disclosure (10-item scale), Trust (17-item scale), Relationship Assessment Scale, Liking and loving (26-item scale) | FQ and FS positively correlate with relationship supportive behaviors (r = 0.76 and 0.75) and the tendency to think oneself in terms of relationships with others (r = 0.31 and 0.37). |

| 32. Ratelle et al. (2013) | CS | USA university students (256, 25%, 23) | FAS | SWB (WB) | Learning Climate Questionnaire, SWLS, PANAS | FAS positively correlates with and SWB (r = 0.43, β = 0.35). |

| 33. Rubin et al. (2016) | L | AU university students (314, 35.67%, 23.4) | SC-Fr, PS | LS (WB) | SC-Fr-SI, DASS, SWLS | SC–Fr predicts LS 6 months later (β = 0.13). |

| 34. Sanchez et al. (2018) | CS | USA college students (study 1: 273, 30.40%, 19.13; study 2: 368, 32%, 18.90) | FM | H, Compassion (WB, R) | FMS, Compassion Scale, SHS, PANAS | FM correlates with compassion for others and H (r = 0.61 and 0.35, respectively) and mediates the relationship of compassion with H (β = 0.18 to.30 for men and 0.24 to 0.29 for women). |

| 35. Secor et al. (2017) | CS, EXP | USA adults (87, 18.39%, 36.87) | SS-Fr, Negative life events | Positive relationships, Life purpose (R, M) | PSSS-Fr, Impact of Event Scale-R, PWBS | SS–Fr positively associates with positive relationships with others and purpose in life after negative life events (r = 0.62 and 0.39, β = 0.52 and 0.35, respectively). |

| 36. Walen and Lachman (2000) | CS | USA adults (3.485, 55%, 49.4) | SS-Fr | LS, PE (WB, PE) | Phone interviews, SS-Fr (4-item scale), LS-SI, PE (6-item scale) | SS–Fr positively associate with LS and PE (r = 0.23 and 0.22, β = 0.08 and 0.14, respectively). |

| 37. Weiner and Hannum (2013) | CS | USA university students (142, 28.9%, 19.83) | Distance from friends | SS-Fr (R) | Distance status of friends, Inventory of Socially Supportive Behaviors-Modified | Among geographically closer friends received SS positively correlates with perceived emotional (r = 0.32), informational (r = 0.33) and instrumental support (r = 0.23). Closer best friends provide higher levels of perceived and received SS than long distance friends. Received instrumental SS is affected more by long distance from friends (d = 0.78). |

| 38. Weisz and Wood (2005) | L | USA university students (80, 50%, N/A) | Social identity support-Fr, Closeness-Fr | FQ (R) | Social Network, Social Support, Social Identity and Social Identity Support Questionnaires | Closeness with and social identity support by another student during the first year predicts best friendship 4 years later (OR = 1.95 and 3.41, respectively). |

CS, cross-sectional; EXP, experimental; L, longitudinal; Q, qualitative. T1, first measurement; T2, second measurement. SI, single item. OR, odds ratio. Friendship variables (measures): FAS, friendship autonomy support; FM, friendship maintenance; FQ, friendship quality (MFQ-FF, McGill Friendship Questionnaire-Friendship Functions); FS, friendship satisfaction; NF, number of friends; PM, perceived mattering (MTOQ, Mattering To Others Questionnaire); PNS, psychological needs satisfaction; PRCA, perceived responses to capitalization attempts; SNS, social network size; SC-Fr, social contact with friends; SS-Fr, social support from friends (PSSS-Fr, Perceived Social Support Scale from Friends). Wellbeing indices (measures): A, accomplishments; E, engagement; H, happiness (SHS, Subjective Happiness Scale); M, meaning in life; LS, life satisfaction (SWLS, Satisfaction With Life Scale); PE, positive emotions (PANAS, Positive and Negative Affect Schedule); PWB, psychological wellbeing; R, positive relationships; SWB, subjective wellbeing; WB, wellbeing.

The selected studies were divided into six subgroups on the basis of the PERMA theory of wellbeing and with regard to the associations of friendship with (a) wellbeing, (b) experiencing positive emotions; (c) engagement; (d) building positive relationships; (e) meaning in life; and (f) accomplishments. Also, another analysis was conducted focusing on individual differences regarding the association of friendship variables with wellbeing components.

3.1. Associations between adult friendship and wellbeing

Twenty-six studies were found to investigate the association between adult friendship and wellbeing variables. The adult friendship variables studied were friendship quality, best or close friendships, number of friends, support from friends, maintenance of friendship, social interaction with friends and support of autonomy from friends. The wellbeing variables studied were subjective wellbeing, psychological wellbeing, happiness, and life satisfaction. The measures used to measure wellbeing variables were Subjective Happiness Scale (n = 9 studies, Lyubomirsky and Lepper, 1999), Satisfaction With Life Scale (n = 11, Diener et al., 1985), Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (n = 9, Watson et al., 1988), other psychological wellbeing measures (n = 5), and single items (n = 3; see Table 1).

The results showed that friendship quality significantly associates with wellbeing (Demir and Weitekamp, 2007; Demir et al., 2007, 2011a,b, 2012b, 2013a,b, 2017; Demir and Özdemir, 2010; Akin and Akin, 2015; Carmichael et al., 2015; Miething et al., 2016). In addition, it was found that friendship quality predicts wellbeing levels in the long run. More specifically, friendship quality at the age of 30 predicts wellbeing at the age of 50 (Carmichael et al., 2015). The friendship function, which has been found to mostly correlate with wellbeing levels is stimulating companionship (Demir et al., 2007).

Moreover, perceived emotional or instrumental support offered by friends has been found to significantly associate with wellbeing (Walen and Lachman, 2000; Griffin et al., 2006; Almquist et al., 2014; Morelli et al., 2015; Secor et al., 2017). An interesting finding is that peer support predicts both the provider's and the recipient's wellbeing levels (Morelli et al., 2015).

Regarding socializing with friends, that is, the amount of time individuals spend together, it was found that it also associates with wellbeing levels (Helliwell and Huang, 2013; Huxhold et al., 2013; Li and Kanazawa, 2016), while predicts wellbeing from 6 months to 12 years later (Derdikman-Eiron et al., 2013; Huxhold et al., 2013; Miething et al., 2016; Rubin et al., 2016). Moreover, friends' support of their partners' autonomy (Demir et al., 2011a; Koestner et al., 2012; Ratelle et al., 2013), their reactions to partner's attempts of capitalizing positive experiences (Demir et al., 2013a, 2017), and efforts to maintain the friendship (Demir et al., 2011a) were also found to be positively correlated with wellbeing levels.

Another friendship variable, which was found to be positively associated with wellbeing, is the number of friends (Cable et al., 2012; Helliwell and Huang, 2013). In particular, large and well-integrated friendship networks emerged as a source of wellbeing for adults (Cable et al., 2012). However, no significant associations were found between wellbeing and other friendship variables, such as same gender vs different gender as well as best or close friendships (Demir et al., 2007, 2017).

Finally, six friendship variables were found to mediate the association between adult friendship and wellbeing. These variables are: maintenance of friendship (Demir et al., 2011a, 2019; Sanchez et al., 2018), perceived mattering (i.e., the psychological tendency to evaluate the self as significant to specific other people, according to Marshall, 2001; see also Demir et al., 2011b, 2012b), personal sense of uniqueness (i.e., the tendency to recognize oneself as having distinctive features and to experience worthiness; Demir et al., 2013b), friendship quality (Demir et al., 2012b, 2013a, 2017), satisfaction of basic psychological needs (Demir and Özdemir, 2010; Demir et al., 2017), and subjective vitality (i.e., the conscious experience of possessing energy and aliveness, according to Ryan and Frederick, 1997; see also Akin and Akin, 2015).

3.2. Association between adult friendship and PERMA components

3.2.1. Associations between adult friendship and experiencing positive emotions

Seven studies were identified investigating the relationship between adult friendship and experiencing positive emotions (see Table 1). Almost in all studies PANAS (n = 6, Watson et al., 1988), was used to measure positive emotions. The results are contradictory regarding the relationship between friendship quality and experiencing of positive emotions. Demir et al. (2007) found no significant relationship, while Demir and Weitekamp (2007) found a low positive correlation. On the other hand, support from friends was found to positively associate with positive emotions among Americans and Jordanians but not Iranians (Walen and Lachman, 2000; Brannan et al., 2013) and predict positive emotions six years later among Germans (Huxhold et al., 2013).

Moreover, research showed that friends' reactions to their partner's attempts of capitalizing positive events, perceived mattering by the friend, psychological needs' satisfaction in friendship (Demir and Davidson, 2013), friend's efforts to maintain the friendship and friendship autonomy support (Demir et al., 2011a) are positively correlated with experiencing of positive emotions. No mediators/moderators of the aforementioned relationships were examined.

3.2.2. Associations between adult friendship and engagement

Only one study was identified investigating the relationship between adult friendship variables and engagement in specific activities (see Table 1). In particular, it was found that the number of friends of secondary and high school students predicts engagement levels in community activities during young adulthood (Heck and Fowler, 2007).

3.2.3. Associations between adult friendship and building positive relationships

Thirteen studies were identified investigating the associations between adult friendship variables and building positive relationships (see Table 1). The results showed that friendship quality and satisfaction positively correlate to relationship supportive behaviors, the tendency to think oneself in terms of relationships with others (Morry and Kito, 2009) and social skills (Demir et al., 2012a). Also, friendship network quality during late adolescence predicts friendship network quality of young adults (Miething et al., 2016). Moreover, friendship quality predicts received support during adversity and emotional-focused support (Chen et al., 2015).

Similarly, companionship with friends during adolescence predicts support from friends during adulthood (Derdikman-Eiron et al., 2013). Also, time spend with friends significantly correlates to higher levels of social support from others and lower levels of loneliness and social distress (Cyranowski et al., 2013). Furthermore, the existing literature reveals an explicit relationship between social support from friends and positive relationships with others (Secor et al., 2017). Taken together, these findings show that adult friendship is an indicator of a well-developed social life.

In addition, support of friends' autonomy is associated with improved quality of friendship after 3 months (Koestner et al., 2012). Individuals who seek support from their friends develop more solidarity-based relationships in their lives, with which they are more satisfied (Carr and Wilder, 2016). Also, received and perceived social support is stronger among geographically closer friends (Weiner and Hannum, 2013) and these friendship maintenance behaviors associate with higher levels of compassion for others (Sanchez et al., 2018). Young adults, especially, build positive, close, supportive and warm relationships if their friends have supported their social identity when they entered university (Weisz and Wood, 2005). Therefore, it is clear that adult friendship exerts a beneficial influence on the quality of concurrent as well as future relationships.

Finally, there is another interesting finding pointing at the mechanisms which lead to positive friendships. When individuals perceive their friends as generous as themselves in their relationship, they are likely to make efforts to maintain and promote the common bond by increasing support and self-disclosure levels in their friendship (Lemay and Clark, 2008).

3.2.4. Associations between adult friendship and meaning in life

Only one study was identified investigating the association between adult friendship variables and sense of meaning in life (see Table 1). In particular, it was found that social support from friends positively associates with purpose in life after negative life events (Secor et al., 2017).

3.2.5. Associations between adult friendship and accomplishments

Similarly, only one study found investigating the relationships between friendship variables and accomplishments (see Table 1). This study found that friendship autonomy support predicts increases in goal progress 3 months later (Koestner et al., 2012).

3.3. Individual differences on the relationship between adult friendship variables and wellbeing outcomes

Regarding gender differences, contradictory findings emerged for different friendship variables and their relationship with wellbeing indices. More specifically, perceived mattering by a friend was found to associate with experiencing of positive emotions only among women (Demir and Davidson, 2013), while in the relationship of wellbeing with friend's responses to capitalization attempts, friendship quality and friendship maintenance behaviors no gender differences were found (Demir et al., 2017, 2019). Moreover, no differences were found based on friendship ratings, i.e., between the three closest friendships and their associations with wellbeing indices (Demir et al., 2007; Demir and Özdemir, 2010).

Concerning race, the few studies investigating racial differences focused on comparing Americans with samples from Arabic countries, e.g., Jordan, Malaysia, and Turkey. A few interesting findings focus on the role of support from friends and friendship quality on the wellbeing levels of different samples based on race. More specifically, friendship quality associates more strongly with support provision among European Americans than Japanese, and associates with higher levels of attentiveness and companionship among Asian Americans than European Americans (Chen et al., 2015). On the other hand, Demir and colleagues (Demir et al., 2012a,b) found no racial differences on the relationship between friendship quality and wellbeing among Americans with Malaysians and Turkish. Among Americans, however, perceived mattering by a friend mediates the relationship of friendship quality and wellbeing, whilst among Turkish friendship quality mediates the relationship of perceived mattering with wellbeing (Demir et al., 2012b). Also, as regards the relationship of satisfaction by the support from friends and wellbeing, no racial differences were found among black and white women (Griffin et al., 2006). Nevertheless, support from friend was found to associate with wellbeing in an American sample but not in Jordanian and Iranian samples (Brannan et al., 2013).

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to systematically review the literature regarding the relationship between adult friendship and wellbeing as well as its components. The existing literature was evaluated through the lens of the PERMA theory (Seligman, 2011), which recognizes five pillars of wellbeing: experiencing positive emotions, engagement, positive relationships, sense of meaning in life, and accomplishments.

The literature review showed that, in general, adult friendship is positively correlated with individuals' wellbeing as well as most of its components. It has been documented that friendship is a valuable personal relationship among adults (Demir, 2015), contributes in various ways to their wellbeing (Pezirkianidis, 2020), enhances their resilience (Mertika et al., 2020; Pezirkianidis, 2020), and fulfills the fundamental human need for social interaction (Lyubomirsky, 2008). However, the instruments used in the previous literature to measure and conceptualize wellbeing significantly vary, i.e., the researchers focus on emotional, psychological, cognitive or subjective aspects of wellbeing making it difficult to draw conclusions and understand the nature of friendships' influences on wellbeing. Also, for particular wellbeing components, the results of the literature review were non-existent, sparse, contradictory or fragmentary, and many were drawn from studies on specific populations.

Concerning the first research question, it was found that the adult friendship variables mostly related to wellbeing are quality of friendship, number of friends, attempts to maintain the friendship, socialization with friends, friends' reactions to partner's attempts to capitalize on positive events, and support from friends (instrumental, emotional or support of autonomy). These findings underlie the importance of studying both qualitative and quantitative dimensions of friendships (Demir and Urberg, 2004; Demir et al., 2007).

As for the second research question, results showed that among the above variables, quality of friendship and socialization with friends predict wellbeing based on longitudinal studies' results. The study of social networks underlines that people's happiness is related to their friends' happiness levels (Fowler and Christakis, 2008; Christakis and Fowler, 2009). Moreover, perceived support from friends, such as companionship, predicts high wellbeing levels more than any other variable (Chau et al., 2010; Forgeard et al., 2011).

In response to the third research question about possible mediators and moderators in the association between adult friendship variables and wellbeing, evidence for moderation was not found. However, six variables were found to mediate this relationship: efforts to maintain the friendship, friendship quality, personal sense of uniqueness, perceived mattering, satisfaction of basic psychological needs, and subjective vitality.

These mediators highlight the possible mechanisms which lead to higher levels of wellbeing. Specifically, when an individual perceives a friend as autonomy supportive, as well as active and constructive responder, friendship quality (e.g., intimacy, support, and trust; Demir et al., 2017) and perceived mattering increase (Demir et al., 2012b). As a result of these positive friendship experiences, individuals satisfy their basic psychological needs (Demir and Özdemir, 2010), realize their unique attributes and create a positive self-image (Demir et al., 2013b); therefore, they are likely to engage in maintenance behaviors in order to reinforce the resilience and continuity of the friendship (Demir et al., 2011a, 2019). This procedure is enhanced when the individual experiences high levels of energy and vitality (Akin and Akin, 2015). Despite the aforementioned findings, further research on mediating and possible moderating effects is clearly needed.

The fourth research question focused on individual differences regarding the associations between adult friendship and wellbeing. The present study found limited differences based on gender and friendship ratings. Previous studies showed significant gender differences concerning friendship functions, but it seems that friendships are equally important for males' and females' wellbeing and prosperity (Christakis and Chalatsis, 2010; Marion et al., 2013). However, significant racial differences were found between samples of completely different cultures, such as Americans and Arabs or Americans and Japanese. More studies needed to shed light on the racial differences between samples of other cultures as well.

The fifth research question focused on whether adult friendship variables can predict specific components of wellbeing on the basis of the PERMA theory (Seligman, 2011). Regarding adult friendship variables and experiencing positive emotions, it was found that friendship quality, support from friends, perceived mattering by friends and satisfaction of the basic psychological needs by a friend significantly and positively associate with experiencing positive emotions. These findings add to the existing knowledge that positive relationships are emotionally rich and a source of great joy for humans (Ryff, 2014). Studies on social networks have shown that positive emotions are “contagious” and are transmitted among friends (Hill et al., 2010; Coviello et al., 2014). Findings about social support show that when friends interact within a positive emotional atmosphere, their experience broadens and this, in turn, activates an upward spiral which evokes even more positive emotions. In this context, partners enrich their interpersonal resources, such as social support, trust, compassion, perceived positive social connections (Kok et al., 2013), and other friendship qualities that are beneficial for physical and mental health (Garland et al., 2010).

According to the PERMA theory, another nuclear component of wellbeing is building positive relationships. The findings of this literature review showed that adult friendship quality and socialization with friends are associated with higher levels of quality and perceived support on every relationship in individuals' lives. Adult friendship is associated with a developed social life, but also with better and more positive relationships. According to Fowler and Christakis (2008), integrating individuals in support networks provides them with the necessary resources to successfully deal with the adverse effects of loneliness. Support from friends, in particular, has been found to lead to higher levels of engagement and satisfaction from different types of relationships, such as romantic and familial ones (Rodrigues et al., 2017). Finally, Weisz and Wood (2005) pointed out that support and appraisal from friends increase satisfaction with friendship as well as its resilience.

Research findings on the relationship of adult friendship with the other three components of wellbeing are limited. Number of friends was found to be related with engagement to community activities, support from friends was found to associate with meaning in life and accomplishments. Relationships with others and the sense of belonging to a network of relationships are one of the main sources of meaning in people's lives (Sørensen et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019) and, thus, create a sense of direction in life and intrinsic motivation to set goals and achieve them (Chalofsky and Krishna, 2009; Weinstein et al., 2013).

4.1. Gaps and limitations of the existing literature

The research literature on the associations between adult friendship, wellbeing and its components is currently growing but is also characterized by gaps and limitations which need to be addressed.

First, existing literature focuses on the quality of friendship as a whole rather than on its specific characteristics and functions in relation to wellbeing. In addition, only a few studies used a longitudinal design or were conducted with pairs of friends. Existing longitudinal studies do not focus on the effects of friendship, but rather study it only secondarily and often with a single-item measure. To add more, research has focused on the relationship between adult friendship and one-dimensional wellbeing indices, such as happiness and life satisfaction. No attempt has been made to construct a comprehensive theoretical model in order to account for the effects of adult friendship variables on specific components of wellbeing. Furthermore, most studies have been conducted in university student samples, a fact that limits the generalizability of the results to different age groups. The above gaps regarding the association between adult friendship and wellbeing are in accordance with some previous attempts to map this research field (Demir, 2015). In conclusion, future studies should address all these gaps and limitations, not only in the general population but also in various population subgroups and cultural contexts.

4.2. Contribution and practical implications of this study

This literature review has clear clinical and social implications. Counselors, psychologists, coaches, social workers, and educators working in clinical, educational, or work settings could utilize the results of this study in order to design interventions for promoting adult friendships. For example, one of the main goals of positive education in childhood and adolescence is to develop skills for building high-quality friendships. Similar efforts could be made in the university context for promoting students' mental health (Bott et al., 2017). In the workplace, building positive relationships and new friendships between employees could be a priority and lead to higher job satisfaction, engagement and productivity (Donaldson et al., 2019). In addition, during counseling or psychotherapy sessions, mental health professionals could use the information provided by this literature review to enhance their clients' supportive environment, experiencing positive emotions and meaning in life and, consequently, strengthen their resilience (Rashid and Baddar, 2019). At the macro level, efforts to build positive friendships and supportive connections between individuals could lead to better and happier citizens, therefore to happier societies (Oishi, 2012).

4.3. Conclusions

This study presented a systematic review of research on how adult friendships contribute to wellbeing as well as its components. Although individuals could reap the benefits of friendship from other social sources as well, it became evident that friendship is a special type of relationship, with a unique contribution to wellbeing. As a result, friendships have survived through the years and, in our days, are considered as vital to psychological flourishing (Wrzus et al., 2017). As Anderson and Fowers (2020) have argued, the most significant contribution of friendship to peoples' lives is the initiation and acceleration of the processes from which wellbeing emerges.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

CP designed the study, conducted the review and the analyses, and wrote the research article. EG wrote and revised the writing of the article. GR wrote parts of the research article. DM revised the writing of the article. AS supervised all stages of the research procedure. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Akin A., Akin Ü. (2015). Friendship quality and subjective happiness: The mediator role of subjective vitality. Educ. Sci. 40, 233–242. 10.15390/EB.2015.378627469364 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Almquist Y. B., Östberg V., Rostila M., Edling C., Rydgren J. (2014). Friendship network characteristics and psychological wellbeing in late adolescence: Exploring differences by gender and gender composition. Scand J. Public Health 42, 146–154. 10.1177/1403494813510793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson A. R., Fowers B. J. (2020). An exploratory study of friendship characteristics and their relations with hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 37, 260–280. 10.1177/0265407519861152 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bott D., Escamilia H., Kaufman S. B., Kern M., Krekel C., Schlicht-Schmälzle R., et al. (2017). The State of Positive Education. Available online at: https://www.worldgovernmentsummit.org/api/publications/document/8f647dc4-e97c-6578-b2f8-ff0000a7ddb6 (accessed December 23, 2022).

- Bowker A. (2004). Predicting friendship stability during early adolescence. J. Early Adolesc. 24, 85–112. 10.1177/0272431603262666 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brannan D., Biswas-Diener R., Mohr C. D., Mortazavi S., Stein N. (2013). Friends and family: a cross-cultural investigation of social support and subjective wellbeing among college students. J. Posit. Psychol. 8, 65–75. 10.1080/17439760.2012.743573 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Butler J., Kern M. L. (2016). The PERMA-profiler: a brief multidimensional measure of flourishing. Int. J. Wellbeing. 6, 1–48. 10.5502/ijw.v6i3.526 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cable N., Bartley M., Chandola T., Sacker A. (2012). Friends are equally important to men and women, but family matters more for men's wellbeing. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 62, 1–6. 10.1136/jech-2012-201113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael C. L., Reis H. T., Duberstein P. R. (2015). In your 20s it's quantity, in your 30s it's quality: the prognostic value of social activity across 30 years of adulthood. Psychol. Aging. 30, 95–105. 10.1037/pag0000014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr and Wilder S. E. (2016). Attachment style and the risks of seeking social support: Variations between friends and siblings. South. Commun. J. 81, 316–329. 10.1080/1041794X.2016.1208266 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chalofsky N., Krishna V. (2009). Meaningfulness, commitment, and engagement: the intersection of a deeper level of intrinsic motivation. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 11, 189–203. 10.1177/1523422309333147 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chau P. S., Saucier D. A., Hafner E. (2010). Meta-analysis of the relationships between social support and wellbeing in children and adolescents. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 29, 624–645. 10.1521/jscp.2010.29.6.62425566380 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. M., Kim H. S., Sherman D. K., Hashimoto T. (2015). Cultural differences in support provision: the importance of relationship quality. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 41, 1575–1589. 10.1177/0146167215602224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christakis and Chalatsis P. (2010). Friendship Relationships: Meanings and Practices in Same and Different Gender Friendships. Athens, Greece: Ellinika Grammata. [Google Scholar]

- Christakis N. A., Fowler J. H. (2009). Connected: The Surprising Power of Our Social Networks and How They Shape our Lives. Boston, MA: Little Brown and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Christakis N. A., Fowler J. H. (2013). Social contagion theory: examining dynamic social networks and human behavior. Stat. Med. 32, 556–577. 10.1002/sim.5408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coviello L., Sohn Y., Kramer A. D., Marlow C., Franceschetti M., Christakis N. A., et al. (2014). Detecting emotional contagion in massive social networks. PLoS ONE. 9, 3. 10.1371/journal.pone.0090315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi M. (2009). “Flow”, in The encyclopedia of positive psychology, Lopez, S. (ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Cyranowski J. M., Zill N., Bode R., Butt Z., Kelly M. A., Pilkonis P. A., et al. (2013). Assessing social support, companionship, and distress: NIH toolbox adult social relationship scales. Health Psychol. 32, 293–301. 10.1037/a0028586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demir M. (2015). Friendship and Happiness: Across the Life-Span and Cultures. New York City: Springer. 10.1007/978-94-017-9603-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demir M., Davidson I. (2013). Toward a better understanding of the relationship between friendship and happiness: Perceived responses to capitalization attempts, feelings of mattering, and satisfaction of basic psychological needs in same-sex best friendships as predictors of happiness. J. Happiness Stud. 14, 525–550. 10.1007/s10902-012-9341-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demir M., Dogan A., Procsal A. D. (2013a). I am so happy'cause my friend is happy for me: capitalization, friendship, and happiness among U.S. and Turkish college students. J. Social Psychol. 153, 250–255. 10.1080/00224545.2012.714814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demir M., Haynes A., Potts S. N. (2017). My friends are my estate: Friendship experiences mediate the relationship between perceived responses to capitalization attempts and happiness. J. Happiness Stud. 18, 1161–1190. 10.1007/s10902-016-9762-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demir M., Jaafar J., Bilyk H., Ariff M. R. M. (2012a). Social skills, friendship and happiness: a cross-cultural investigation. J. Soc. Psychol. 152, 79–385. 10.1080/00224545.2011.591451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demir M., Özdemir M. (2010). Friendship, need satisfaction and happiness. J. Happiness Stud. 11, 243–259. 10.1007/s10902-009-9138-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demir M., Özdemir M., Marum K. P. (2011a). Perceived autonomy support, friendship maintenance, and happiness. J. Psychol. 145, 537–571. 10.1080/00223980.2011.607866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demir M., Özdemir M., Weitekamp L. A. (2007). Looking to happy tomorrow with friends: best and close friendships as they predict happiness. J. Happiness Stud. 8, 243–271. 10.1007/s10902-006-9025-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demir M., Özen A., Dogan A. (2012b). Friendship, perceived mattering and happiness: a study of American and Turkish college students. J. Soc. Psychol. 152, 659–664. 10.1080/00224545.2011.650237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demir M., Özen A., Dogan A., Bilyk N. A., Tyrell F. A. (2011b). I matter to my friend, therefore I am happy: friendship, mattering, and happiness. J. Happiness Stud. 12, 983–1005. 10.1007/s10902-010-9240-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demir M., Simşek Ö., Procsal A. (2013b). I am so happy'cause my best friend makes me feel unique: Friendship, personal sense of uniqueness and happiness. J. Happiness Stud. 14, 1201–1224. 10.1007/s10902-012-9376-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demir M., Tyra A., Özen-Çiplak A. (2019). Be there for me and I will be there for you: Friendship maintenance mediates the relationship between capitalization and happiness. J. Happiness Stud. 20, 449–469. 10.1007/s10902-017-9957-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demir M., Urberg K. A. (2004). Friendship and adjustment among adolescents. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 88, 68–82. 10.1016/j.jecp.2004.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demir M., Weitekamp L. A. (2007). I am so happy'cause today I found my friend: Friendship and personality as predictors of happiness. J. Happiness Stud. 8, 181–211. 10.1007/s10902-006-9012-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Derdikman-Eiron R., Hjemdal O., Lydersen S., Bratberg G. H., Indredavik M. S. (2013). Adolescent predictors and associates of psychosocial functioning in young men and women: 11 year follow-up findings from the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study. Scand 0. J. Psychol. 54, 95–101. 10.1111/sjop.12036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E. (1984). Subjective wellbeing. Psychol. Bull. 95, 542–575. 10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E., Emmons R., Larsen R., Griffin S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 49, 71–75. 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E., Suh E. M., Lucas R. E., Smith H. L. (1999). Subjective wellbeing: three decades of progress. Psychol. Bull. 125, 276–302. 10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Disabato D., Goodman F. R., Kashdan T. B. (2019). A hierarchical framework for the measurement of well-being. PsyArXiv [Preprint]. 10.31234/osf.io/5rhqj [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson S. I., Lee J. Y., Donaldson S. I. (2019). Evaluating positive psychology interventions at work: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Appl. Posit. Psychol. 4, 113–134. 10.1007/s41042-019-00021-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donnellan W. J., Bennett K. M., Soulsby L. K. (2017). Family close but friends closer: exploring social support and resilience in older spousal dementia carers. Aging and Mental Health. 21, 1222–1228. 10.1080/13607863.2016.1209734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehr B. (2000). “The life circle of friendship,” in Close Relationships: A Sourcebook, Hendrick, C., and Hendrick, S. S. (Eds.). New York: Sage Publications. p. 71–85. 10.4135/9781452220437.n6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fehr B., Harasymchuk C. (2018). “The role of friendships in wellbeing,” in Subjective Wellbeing and Life Satisfaction, Maddux, J. (ed.). Routledge. p. 103–128. 10.4324/9781351231879-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forgeard M. J. C., Jayawickreme E., Kern M., Seligman M. E. P. (2011). Doing the right thing: measuring wellbeing for public policy. Int. J. Wellbeing. 1, 79–106. 10.5502/ijw.v1i1.15 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler J. H., Christakis N. A. (2008). Dynamic spread of happiness in a large social network: Longitudinal analysis over 20 years in the Framingham Heart Study. Br. Med. J. 337, 1–9. 10.1136/bmj.a2338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psycholog. 56, 218–226. 10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson B. L., Branigan C. (2005). Positive emotions broaden the scope of attention and thought-action repertoires. Cognit. Emotion. 19, 313–332. 10.1080/02699930441000238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson B. L., Joiner T. (2002). Positive emotions trigger upward spirals toward emotional wellbeing. Psychological Sci. 13, 172–175. 10.1111/1467-9280.00431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson B. L., Mancuso R., Branigan C., Tugade M. (2000). The undoing effect of positive emotions. Motivation Emot. 24, 237–258. 10.1023/A:1010796329158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz B., Avsec A. (2007). The experience of flow and subjective wellbeing of music students. Horiz. Psychol. 16, 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Galanakis M., Lakioti A., Pezirkianidis C., Karakasidou E., Stalikas A. (2017). Reliability and validity of the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) in a Greek sample. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 5, 120–127. [Google Scholar]

- Garland E. L., Fredrickson B., Kring A. M., Johnson D. P, Meyer P. S., Penn D. L. (2010). Upward spirals of positive emotions counter downward spirals of negativity: Insights from the broaden-and-build theory and affective neuroscience on the treatment of emotion dysfunctions and deficits in psychopathology. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 30, 849–864. 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L. R., Richardson D. S., Lago T., Schatten-Jones E. C. (2001). Network correlates of social and emotional loneliness in young and older adults. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 27, 281–288. 10.1177/014616720127300222 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin M. L., Amodeo M., Clay C., Fassler I., Ellis M. A. (2006). Racial differences in social support: Kin vs. friends. Am. J. Orthopsychiat. 76, 374–380. 10.1037/0002-9432.76.3.374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J. A. (2011). Sex differences in friendship expectations: a meta-analysis. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 28, 723–747. 10.1177/0265407510386192 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heck K., Fowler J. H. (2007). Friends, Trust, and Civic Engagement. Available online at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1024985

- Heintzelman S. J. (2018). “Eudaimonia in the contemporary science of subjective wellbeing: Psychological wellbeing, self-determination, and meaning in life,” in Handbook of wellbeing. DEF Publishers, Diener, E., Oishi, S., and Tay, L. (eds.). Available online at: https://www.nobascholar.com/chapters/18/download.pdf (accessed December 23, 2022).

- Helliwell J. F., Huang H. (2013). Comparing the happiness effects of real and on-line friends. PLoS ONE. 8, e72754. 10.1371/journal.pone.0072754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks J., King L. (2009). Positive mood and social relatedness as information about meaning in life. J. Positive Psychol. 4, 471–482. 10.1080/1743976090327110820729336 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hill A. L., Rand D. G., Nowak M. A., Christakis N. A. (2010). Infectious disease modeling of social contagion in networks. PLoS Comput. Biol. 6, e1000968. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holder M. D., Coleman B. (2015). “Children's friendships and positive wellbeing,” in Friendship and Happiness, Demir, M. (ed.). New York City: Springer. p. 81–97. 10.1007/978-94-017-9603-3_5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Houben M., Van Den Noortgate W., Kuppens P. (2015). The relation between short-term emotion dynamics and psychological wellbeing: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bull. 141, 901–930. 10.1037/a0038822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huta V. (2016). “An overview of hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing concepts,” in The Routledge Handbook of Media Use and Wellbeing, Reinecke, L., and Oliver, M.-B. (eds.). London: Routledge. p. 14–33. [Google Scholar]

- Huta V., Waterman A. S. (2014). Eudaimonia and its distinction from hedonia: developing a classification and terminology for understanding conceptual and operational definitions. J. Happiness Stud. 15, 1425–1456. 10.1007/s10902-013-9485-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huxhold O., Miche M., Schüz B. (2013). Benefits of having friends in older ages: differential effects of informal social activities on wellbeing in middle-aged and older adults. J. Gerontol. B. Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 69, 366–375. 10.1093/geronb/gbt029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innstrand S., Langballe E., Falkum E. (2012). A longitudinal study of the relationship between work engagement and symptoms of anxiety and depression. Stress Health. 28, 1–10. 10.1002/smi.1395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane H. S., McCall C., Collins N. L., Blascovich J. (2012). Mere presence is not enough: responsive support in a virtual world. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 48, 37–44. 10.1016/j.jesp.2011.07.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes C. (2005). Mental illness and/or mental health? Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 73, 539–548. 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koestner R., Powers T. A., Carbonneau N., Milyavskaya M., Chua S. N. (2012). Distinguishing autonomous and directive forms of goal support: their effects on goal progress, relationship quality, and subjective wellbeing. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 38, 1609–1620. 10.1177/0146167212457075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok B. E., Coffey K. A., Cohn M. A., Catalino L. I., Vacharkulksemsuk T., Algoe B. S., et al. (2013). How positive emotions build physical health: Perceived positive social connections account for the upward spiral between positive emotions and vagal tone. Psychological Sci. 24, 1123–1132. 10.1177/0956797612470827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemay. E. P, Clark M. S. (2008). How the head liberates the heart: Projection of communal responsiveness guides relationship promotion. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 94, 647–671. 10.1037/0022-3514.94.4.647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Ji Y., Chen T. (2014). The roles of different sources of social support on emotional wellbeing among Chinese elderly. PloS ONE. 9, e90051. 10.1371/journal.pone.0090051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N. P., Kanazawa S. (2016). Country roads, take me home… to my friends: How intelligence, population density, and friendship affect modern happiness. Br. J. Psychol. 107, 675–697. 10.1111/bjop.12181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S. (2008). The How of Happiness: A Scientific Approach to Getting the Life You Want. London: Penguin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S., Lepper H. (1999). A measure of subjective happiness: preliminary reliability and construct validation. Soc. Indic. Res. 46, 137–155. 10.1023/A:1006824100041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marion D., Laursen B., Zettergren P., Bergman L. R. (2013). Predicting life satisfaction during middle adulthood from peer relationships during mid-adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 42, 1299–1307. 10.1007/s10964-013-9969-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall S. K. (2001). Do I matter? Construct validation of adolescents' perceived mattering to parents and friends. J. Adolesc. 24, 473–490. 10.1006/jado.2001.0384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martela F., Sheldon K. M. (2019). Clarifying the concept of wellbeing: psychological need satisfaction as the common core connecting eudaimonic and subjective wellbeing. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 23, 458–474. 10.1177/1089268019880886 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martela F., Steger M. F. (2016). The three meanings of meaning in life: distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance. J. Posit. Psychol. 11, 531–545. 10.1080/17439760.2015.1137623 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson M. J., Aboud F. E. (1999). Measuring friendship quality in late adolescents and young adults: McGill Friendship Questionnaires. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 31, 130–132. 10.1037/h0087080 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mertika A., Mitskidou P., Stalikas A. (2020). “Positive relationships” and their impact on wellbeing: a review of the current literature. Psychology. 25, 115–127. 10.12681/psy_hps.25340 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miething A., Almquist Y. B., Edling C., Rydgren J., Rostila M. (2017). Friendship trust and psychological wellbeing from late adolescence to early adulthood: a structural equation modelling approach. Scand 0. J. Public Health. 45, 244–252. 10.1177/1403494816680784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miething A., Almquist Y. B., Östberg V., Rostila M., Edling C., Rydgren J. (2016). Friendship networks and psychological wellbeing from late adolescence to young adulthood: a gender-specific structural equation modeling approach. Psychology. 4, 1–11. 10.1186/s40359-016-0143-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitskidou P., Mertika A., Pezirkianidis C., Stalikas A. (2021). Positive Relationships Questionnaire (PRQ): a pilot study. Psychology. 12, 1039–1057. 10.4236/psych.2021.127062 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morelli S. A., Lee I. A., Arnn M. E., Zaki J. (2015). Emotional and instrumental support provision interact to predict wellbeing. Emotion. 15, 484–493. 10.1037/emo0000084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morry M. M., Kito M. (2009). Relational-interdependent self-construal as a predictor of relationship quality: The mediating of one's own behaviors and perceptions of the fulfillment of friendship functions. J. Soc. Psychol. 149, 205–222. 10.3200/SOCP.149.3.305-322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen A. W., Chatters L. M., Taylor R. J., Mouzon D. M. (2016). Social support from family and friends and subjective wellbeing of older African Americans. J. Happiness Stud. 17, 959–979. 10.1007/s10902-015-9626-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nohria N., Groysberg B., Lee L. (2008). Employee motivation. Harvard Business Rev. 86: 78–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oishi S. (2012). The Psychological Wealth of Nations: Do Happy People Make a Happy Society?. New York: Wiley. 10.1002/9781444354447 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park J., Roh S. (2013). Daily spiritual experiences, social support, and depression among elderly Korean immigrants. Aging and Mental Health. 17, 102–108. 10.1080/13607863.2012.715138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pezirkianidis C. (2020). “Construction of a theoretical model for adult friendships under the scope of Positive Psychology. (PhD thesis),” Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences. Available online at: https://www.didaktorika.gr/eadd/handle/10442/48037 (accessed December 23, 2022).

- Pezirkianidis C., Galanakis M., Karakasidou I., Stalikas A. (2016a). Validation of the Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ) in a Greek sample. Psychology. 7, 1518–1530. 10.4236/psych.2016.713148 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pezirkianidis C., Karakasidou E., Lakioti A., Stalikas A., Galanakis M. (2018). Psychometric properties of the Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21) in a Greek sample. Psychology,. 9, 2933–2950. 10.4236/psych.2018.915170 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pezirkianidis C., Stalikas A., Efstathiou E., Karakasidou E. (2016b). The relationship between meaning in life, emotions and psychological illness: the moderating role of the effects of the economic crisis. J. Counselling Psychol. 4, 77–100. 10.5964/ejcop.v4i1.75 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raboteg-Saric Z., Sakic M. (2014). Relations of parenting styles and friendship quality to self-esteem, life satisfaction and happiness in adolescents. Qual. Life Res. 9, 749–765. 10.1007/s11482-013-9268-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rashid T., Baddar M. K. (2019). “Positive Psychotherapy: Clinical and Cross-Cultural Applications of Positive Psychology, in Positive psychology in the Middle East/North Africa, Lambert, L., and Pasha-Zaidi, N. (eds.). New York: Springer. 10.1007/978-3-030-13921-6_15 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ratelle C. F., Simard K., Guay F. (2013). University students' subjective wellbeing: the role of autonomy support from parents, friends, and the romantic partner. J. Happiness Stud. 14, 893–910. 10.1007/s10902-012-9360-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues D., Lopes D., Monteiro L., Prada M. (2017). Perceived parent and friend support for romantic relationships in emerging adults. Personal Relationships. 24, 4–16. 10.1111/pere.12163 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin M., Evans O., Wilkinson R. B. (2016). A longitudinal study of the relations between university students' subjective social status, social contact with university friends, and mental health and wellbeing. J. Social and Clinical Psychol. 35, 722–737. 10.1521/jscp.2016.35.9.722 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan R. M., Frederick C. (1997). On energy, personality and health: subjective vitality as a dynamic reflection of wellbeing. J. Pers. 65, 529–565. 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1997.tb00326.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological wellbeing. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 57, 1069–1081. 10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff C. D. (2014). Psychological wellbeing revisited: advances in the science and practice of eudaimonia. Psychother. Psychosom. 83, 10–28. 10.1159/000353263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]