Abstract

What is already known about this topic?

Limited evidence on healthy longevity was provided in the world, and no studies investigated the fractions of healthy longevity attributed to modifiable factors.

What is added by this report?

Incidences of longevity and healthy longevity in China are provided. It reveals that the total weighted population attributable fractions for lifestyles and all modifiable factors were 32.8% and 83.7% for longevity, respectively, and 30.4% and 73.4% for healthy longevity, respectively.

What are the implications for public health practice?

China has a high potential for longevity and healthy longevity. Strategies may be targeted at education and residence in early life as well as healthy lifestyles, disease prevention, and functional optimization in late life.

Keywords: Population attributable fraction, Healthy longevity, Late-elderly

Globally, the population of the late-elderly (aged ≥75 years) was expected to rise from 275 million in 2020 to 768 million by 2050 (1), which might result in large disease burdens accompanied by increased life years of ill-health (2–3). However, the lack of data on multiple health measurements of older adults in large long-term cohorts increases the difficulty in studying healthy longevity. To fill the gap, analyses were conducted using data from the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS) from 1998 to 2018. Separate logistic regression models were performed to identify factors associated with longevity and healthy longevity among 11,005 late-elderly participants, who were more likely to survive to 90 years old than younger adults. The corresponding population attributable fractions (PAFs) were also calculated. The incidence densities were 17.0/1,000 person-years for healthy longevity and 63.0/1,000 person-years for usual longevity. Considering early life factors, lifestyles, functional health, and diseases, the total weighted PAFs were 83.7% for longevity and 73.4% for healthy longevity, suggesting great potential for longevity and healthy longevity in China. Effective strategies may include targeting people through education and residence in early life, healthy lifestyles, disease prevention, and functional optimization in late life.

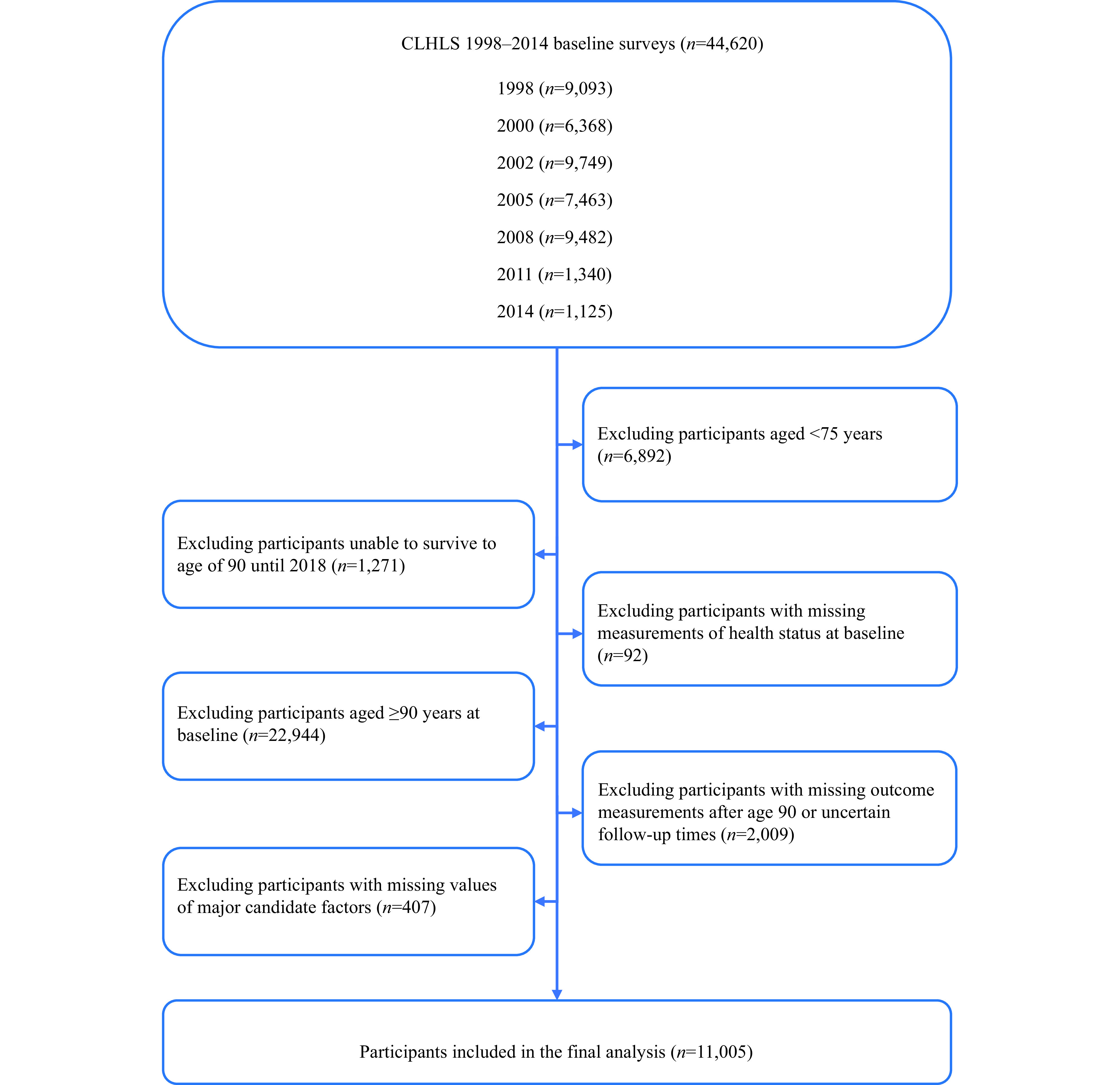

Study participants were recruited from the CLHLS study, which is the first study to investigate factors of healthy longevity in China covering 23 provincial-level administrative divisions (PLADs) (3). The study included 11,005 late-elderly participants who had the potential to survive to age 90 years by 2018, with complete measurement of outcomes and candidate factors for analysis (Supplementary Figure S1, available in http://weekly.chinacdc.cn). Healthy longevity was defined with reference to the WHO definition of healthy ageing and participants were classified into three categories (2): 1) healthy longevity: age at death ≥90 years, with good physical performance, cognitive function, mental health, visual function, and hearing function; 2) usual longevity: age at death ≥90 years, with at least one kind of functional impairment or disability mentioned above; 3) non-survival: age at death <90 years, irrespective of functional status (Supplementary Methods, available in http://weekly.chinacdc.cn). Candidate influencing factors, including demographic characteristics, lifestyles, functional status, self-rated health, and diseases, were collected through face-to-face interviews with all participants (Supplementary Methods).

Factors of longevity and healthy longevity were identified with separate logistic regression models via a bidirectional stepwise procedure and inclusion of candidate factors with P<0.1 in the raw estimates only adjusted for age: 1) non-longevity versus longevity; 2) usual longevity versus healthy longevity. As participants with different baseline ages will have different periods to age 90, age was included as a confounder as opposed to a risk factor in the analyses. The PAFs of modifiable factors were calculated by transforming them into binary or multifactorial variables according to previous studies and were adjusted for communality, which explains the overlap between factors (4-5). We performed a principal component analysis to calculate the communality for each factor and took into account how much each unobserved component explained each measured factor (5). Both age and sex were considered fixed variables. In this study, the PAF is interpreted as the probability gains of longevity or healthy longevity if all participants kept to healthy lifestyles or were in the absence of adverse health status factors (4). All analyses were finished with R 4.1.3 for Windows (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Statistical significance was set at two-tailed with a P-value <0.05.

Overall, 3,454 (31.4%) participants survived to age 90, of whom 735 (6.7%) were classified as having healthy longevity and 2,719 (24.7%) were classified as having usual longevity. The corresponding incidence densities were 17.0/1,000 and 63.0/1,000 person-years, respectively. Rural residents and women were more likely to be classified as having longevity, but most of them were classified as having usual longevity, indicative of a lower likelihood of being classified as having healthy longevity. The incidences of longevity, healthy longevity, and usual longevity were higher in older adults with advanced ages (Table 1).

Table 1. Person-years of follow-up, number of outcome events, and incidence per 1,000 person years of observation by residence, sex, and age groups among Chinese late-elderly, 1998–2018.

| Groups | All participants | Longevity | Healthy longevity | Usual longevity | |||||||

| No. of participants | Person-years | No. of events | Incidence | No. of events | Incidence | No. of events | Incidence | ||||

| Total | 11,005 | 43,154 | 3,454 | 80.0 | 735 | 17.0 | 2,719 | 63.0 | |||

| Residence | |||||||||||

| Urban | 4,683 | 17,980 | 1,371 | 76.3 | 311 | 17.3 | 1,060 | 59.0 | |||

| Rural | 6,322 | 25,174 | 2,083 | 82.7 | 424 | 16.8 | 1,659 | 65.9 | |||

| Sex | |||||||||||

| Men | 5,595 | 21,103 | 1,572 | 74.5 | 417 | 19.8 | 1,155 | 54.7 | |||

| Women | 5,410 | 22,051 | 1,882 | 85.3 | 318 | 14.4 | 1,564 | 70.9 | |||

| Age group (years) | |||||||||||

| 75–79 | 1,516 | 9,339 | 179 | 19.2 | 40 | 4.3 | 139 | 14.9 | |||

| 80–84 | 4,791 | 20,952 | 938 | 44.8 | 185 | 8.8 | 753 | 36.0 | |||

| 85–89 | 4,698 | 12,862 | 2,337 | 181.7 | 510 | 39.7 | 1,827 | 142.0 | |||

Odds ratios [95% confidence intervals (CIs)] for factors retained in the final logistic regression models are presented in Table 2. The PAFs for modifiable factors associated with longevity and healthy longevity are displayed in Table 3. Of all modifiable lifestyles, performing housework, watching TV or listening to the radio, and never smoking are the top three factors contributing to longevity (weighted PAFs were 6.7%, 4.9%, and 3.3%, respectively); never smoking or having quit, normal weight or overweight, and tea-drinking are the top three factors contributing to healthy longevity (weighted PAFs were 8.8%, 6.0%, and 4.9%, respectively). All modifiable lifestyles combined may explain 32.8% probability gains of longevity and 30.4% probability gains of healthy longevity. The probability gains reached 83.7% and 73.4% when all potentially modifiable factors, excluding age and sex, were considered. Among factors other than lifestyles, interventions at early ages also contribute to considerable probability gains of longevity and healthy longevity (weighted PAF of residence areas was 2.7% for longevity, weighted PAF of education years was 2.3% for healthy longevity); early prevention and usage of supporting tools or equipment to optimize functional abilities are also important in promoting longevity [weighted PAFs of chewing ability, activities of daily living (ADL) limitations, and cognitive impairment were 2.2%, 13.1%, and 9.3%, respectively] and healthy longevity (weighted PAFs of chewing ability, ADL limitations, and hearing function were 4.4%, 15.4%, and 20.5%, respectively).

Table 2. Odds ratios (95% CIs) for factors associated with longevity and healthy longevity among Chinese late-elderly, 1998–2018.

| Characteristics | Longevity | Healthy longevity | ||

| OR (95% CI) | P -value | OR (95% CI) | P -value | |

| Note: Data are adjusted OR (95% CI). A value higher than 1 indicates participants are more likely to be longevity or healthy longevity. Not included means factors were not selected or non-significant (P>0.05) in the stepwise logistic models and not retained in the final models. Abbreviation: CI=confidence interval; OR=odds ratio; ADL=activities of daily living; MMSE=mini-mental state examination; BMI=body mass index. | ||||

| Women | 1.45 (1.30–1.61) | <0.001 | 0.71 (0.58–0.87) | 0.001 |

| Rural | 1.16 (1.05–1.28) | 0.003 | Not included | |

| Education years (per 1 year) | Not included | − | 1.05 (1.03–1.08) | <0.001 |

| Smoking | ||||

| Never smokers | 1 (ref) | − | 1 (ref) | − |

| Current smokers | 0.86 (0.76–0.97) | 0.016 | 0.79 (0.62–0.99) | 0.044 |

| Former smokers | 0.83 (0.72–0.95) | 0.007 | 1.14 (0.89–1.46) | 0.310 |

| Performing housework | Not included | |||

| Rarely or not | 1 (ref) | − | − | − |

| Occasionally | 1.25 (1.09–1.44) | 0.002 | − | − |

| Often | 1.42 (1.29–1.57) | <0.001 | − | − |

| Raising domestic animals | ||||

| Rarely or not | 1 (ref) | − | 1 (ref) | − |

| Occasionally | 1.04 (0.88–1.22) | 0.670 | 1.51 (1.13–2.01) | 0.006 |

| Often | 1.23 (1.09–1.38) | 0.001 | 1.35 (1.09–1.65) | 0.005 |

| Reading newspapers or book | Not included | |||

| Rarely or not | 1 (ref) | − | − | − |

| Occasionally | 0.94 (0.78–1.13) | 0.490 | − | − |

| Often | 1.19 (1.03–1.38) | 0.019 | − | − |

| Watching TV or listening to the radio | Not included | |||

| Rarely or not | 1 (ref) | − | − | − |

| Occasionally | 1.11 (0.98–1.27) | 0.110 | − | − |

| Often | 1.27 (1.14–1.43) | <0.001 | − | − |

| Garlic consumption | Not included | |||

| Rarely or not | 1 (ref) | − | − | − |

| Occasionally | 1.14 (1.04–1.26) | 0.008 | − | − |

| Often | 1.05 (0.92–1.19) | 0.510 | − | − |

| Tea drinking | Not included | |||

| Rarely or not | − | − | 1 (ref) | − |

| Occasionally | − | − | 1.37 (1.10–1.71) | 0.005 |

| Often | − | − | 1.21 (0.99–1.47) | 0.062 |

| Good chewing ability | 1.14 (1.03–1.25) | 0.008 | 1.25 (1.05–1.48) | 0.014 |

| ADL score (per 1 point) | 0.84 (0.80–0.88) | <0.001 | 0.85 (0.75–0.97) | 0.018 |

| MMSE score (per 1 point) | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) | <0.001 | ||

| Psychological resources (per 1 point) | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) | 0.005 | 1.05 (1.03–1.08) | <0.001 |

| Hearing loss | Not included | 0.49 (0.33–0.74) | 0.001 | |

| Heart disease | 0.73 (0.61–0.87) | 0.001 | ||

| Cerebrovascular disease | 0.77 (0.60–0.98) | 0.036 | Not included | − |

| Respiratory disease | 0.79 (0.69–0.91) | 0.001 | Not included | − |

| BMI | Not included | |||

| Underweight | − | − | 0.82 (0.68–0.98) | 0.032 |

| Normal | − | − | 1 (ref) | − |

| Overweight | − | − | 1.08 (0.81–1.43) | 0.620 |

| Obese | − | − | 0.45 (0.22–0.89) | 0.022 |

| Self-rated health status | Not included | |||

| Good | 1.07 (0.97–1.19) | 0.19 | − | − |

| So so | 1 (ref) | − | − | − |

| Bad | 0.76 (0.65–0.89) | 0.001 | − | − |

Table 3. Population attributable fractions for modifiable factors of longevity and healthy longevity among the late-elderly in China, 1998–2018.

| Factors | PAFs for longevity (%) | PAFs for healthy longevity (%) | |||

| Raw | Weighted † | Raw | Weighted † | ||

| Note: All models were adjusted for age, sex, and all other potentially modifiable factors. Not included means factors were not selected or non-significant (P>0.05) in the stepwise logistic models and not retained in the final models. Abbreviation: CI=confidence interval; PAF=population attributable fraction; BMI=body mass index; ADL=activities of daily living. * Based on the results of separate logistic models, never smoking was considered in the calculation of PAFs for longevity, and never or quit smoking was considered in the calculation of PAFs for healthy longevity. † Weighted PAFs were the relative contributions of each factor to the overall PAF of all potentially modifiable factors when adjusted for communality. | |||||

| Lifestyle factors | |||||

| Smoking* | 9.8 | 3.3 | 21.4 | 8.8 | |

| Tea drinking (often or occasionally) | Not included | Not included | 12.0 | 4.9 | |

| Garlic consumption (often or occasionally) | 7.5 | 2.5 | Not included | Not included | |

| Performing housework (often or occasionally) | 19.9 | 6.7 | Not included | Not included | |

| Reading newspapers or books (often) | 3.4 | 1.1 | Not included | Not included | |

| Raising domestic animals (often or occasionally) | 4.8 | 1.6 | 9.8 | 4.0 | |

| Watching TV or listening to the radio (often or occasionally) | 14.5 | 4.9 | Not included | Not included | |

| BMI (normal weight or overweight; 18.5–27.9 kg/m2) | Not included | Not included | 14.7 | 6.0 | |

| Other potentially modifiable factors | |||||

| Residence (rural) | 7.9 | 2.7 | Not included | Not included | |

| Education years (≥6) | Not included | Not included | 5.5 | 2.3 | |

| Chewing ability (good) | 6.4 | 2.2 | 10.7 | 4.4 | |

| ADL limitations (no) | 38.8 | 13.1 | 37.5 | 15.4 | |

| Cognitive impairment (no) | 27.6 | 9.3 | Not included | Not included | |

| Mental health (good) | 9.7 | 3.3 | 17.3 | 7.1 | |

| Hearing function (good) | Not included | Not included | 49.8 | 20.5 | |

| Heart disease (no) | 24.8 | 8.4 | Not included | Not included | |

| Cerebrovascular disease (no) | 27.1 | 9.1 | Not included | Not included | |

| Respiratory disease (no) | 19.0 | 6.4 | Not included | Not included | |

| Self-rated health status (good or so so) | 26.7 | 9.0 | Not included | Not included | |

| Combined factors | |||||

| All modifiable lifestyle factors | 47.5 | 32.8 | 46.8 | 30.4 | |

| All potentially modifiable factors | 94.1 | 83.7 | 88.3 | 73.4 | |

DISCUSSIONS

In this large cohort study of 11,005 late-elderly participants, incidences of longevity and healthy longevity in China were provided and 19 modifiable factors for longevity and healthy longevity were identified. The weighted PAFs of longevity and healthy longevity are 32.8% and 30.4%, respectively, for all modifiable lifestyle factors and would increase to 83.7% for longevity and 73.4% for healthy longevity when all potentially modifiable factors were considered. Longevity and healthy longevity should be considered from a life course perspective, in which education and residence in early life and lifestyles in late life would continuously influence both the health status (including functional status and diseases) of a person and the probability of longevity and healthy longevity. Although functional status and diseases are probably irreversible in late life, the benefits are still substantial if supporting environments are strengthened to optimize the intrinsic capacity and functional abilities of late-elderly populations.

In this study, the probability of healthy longevity in China was suggested to be similar to that in younger Americans (6–7). Sex and 19 modifiable factors associated with longevity and healthy longevity in China were identified. These results are consistent with previous findings. The PAF for modifiable lifestyles of healthy longevity is comparable to a previous study that investigated successful aging in the United Kingdom when not adjusted for communality (4). Sociodemographically, women, rural residents, and participants with higher education levels were more likely to be classified as having longevity and/or healthy longevity (6). Regarding lifestyles, never smoking and engaging in leisure activities were beneficial to longevity and/or healthy longevity in late-elderly participants, which may be explained by their effects on reducing the risk of cognitive impairment, ADL disability, and mortality (4,6,8); garlic consumption and tea drinking may protect the late-elderly participants by the antidotal effect, inhibiting the growth of cancer cells, and reducing inflammatory levels (9); late-elderly participants who were underweight or obese may suffer from higher risk of chronic diseases and disabilities, reducing the likelihood of healthy longevity (10). Regarding other health measurements, late-elderly participants with good chewing ability, ADL independence, cognitive function, mental health, and hearing function were more likely to reach longevity and/or healthy longevity. These late-elderly participants may suffer from slower functional declines, and good chewing ability also enabled the adequate intake of essential nutrients. Conversely, late-elderly participants with heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, respiratory disease, and bad self-rated health status were more likely to suffer from functional declines and less likely to reach longevity (11).

Several limitations need to be considered when interpreting these findings. First, this study did not include data on genetic information and biomarkers, which need to be further investigated in future studies. Second, the inclusion of Chinese late-elderly participants might limit the generalizability of these findings to other racial groups.

In summary, incidences of longevity and healthy longevity in China in a large cohort of late-elderly participants were provided and revealed that education and residence in early life, healthy lifestyles, disease prevention, and functional optimization in late life together contribute to longevity and healthy longevity. The findings of this study reinforced the importance of a life course perspective in health management and may be applied to develop intervention strategies against the burdens attributed to the ageing population in China.

Conflicts of interest

No conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Methods

Participants recruited at different baseline waves may have different periods to age 90, leading to a smaller number of participants included in the later cohorts for analyses (Supplementary Figure S1). To address the potential bias, baseline age as a confounder was included in the analyses (1).

Healthy longevity is a combination of healthy aging and longer lifespan. Nevertheless, there is still no consensus on the definition of healthy longevity around the world. Previous studies defined healthy longevity as healthy survival to a specific age (e.g., 70, 85, 90), without major diseases, and/or functional decline (physical performance, and/or cognitive impairment) (1-5). These studies paid more attention to diseases rather than functional status, which may not be consistent with the WHO’s definition of healthy ageing as “the process of developing and maintaining the functional ability that enables wellbeing in older age;” presence of diseases is a factor rather than an exclusion criteria of healthy ageing (6).

In this study, a cut-off of 90 was used to define longevity, and healthy longevity was defined in combination with longevity and WHO’s definition of healthy ageing, which focuses more on functional ability that reflects the intrinsic capacity of the individual (i.e., mental and physical capacities including abilities to walk, think, see, hear, and remember) and considers diseases as factors that influence intrinsic capacity and healthy ageing (6). This is similar to the definition proposed by U.S. National Academy of Medicine which links healthy longevity to maintaining physical, mental, and social health and well-being as humans live longer, rather than simply treating ailments (7–8).

According to the healthy ageing concept of WHO, healthy longevity was defined in combination with age at death, physical performance, cognitive function, mental health, visual function, and hearing function. Participants were classified into healthy longevity, usual longevity, and non-survival (Please find the details in the second paragraph of the main text).

The functional performance was measured by qualified doctors at baseline and each follow-up survey until the end of study, death, or lost-to-follow-up. First, physical performance was measured by physical activities in three tests (stand up from a chair, pick up a book from floor, and turn around 360°) (9), and ADL (evaluated by Katz scale, including bathing, dressing, eating, transferring, toileting, and continence; participants who need any assistance with the activity were regarded as having an ADL disability; ADL score, ranges 6–18 points, was also calculated for participants, lower scores represent lower limitations in ADL) (10). Participants without limitations in ADL and physical activities were regarded as having good physical performance. Second, cognitive function was assessed by the mini-mental state examination (MMSE) with a total of 30 points for 24 questions, and the higher the score, the better the cognitive function. Education-adjusted cut-offs were applied to define cognitive impairment (11). Third, mental health was assessed by seven items (5-point response scale, 0–4 points were assigned to each item). The total score ranges 0–28 points, and the higher the score, the better the mental health. Late-elderly participants with scores ≥18 points (the median value) were classified as having good mental health (12). Fourth, visual function was examined by a vision test, defined as poor if the participant cannot see the circle on the cardboard sheet under a flashlight or if the participant is blind (13). Fifth, hearing function was examined during the interview, defined as hearing loss if the participant can only hear a part of what interviewer said with or without a hearing aid, or cannot hear anything (14).

A face-to-face interview was conducted using a validated questionnaire to collect the demographic characteristics (i.e., age, gender, place of residence, education years, marital status, etc.), lifestyles (i.e., smoking, drinking, exercising, performing housework, gardening, reading, raising domestic animals, watching TV or listening to radio, playing cards or mahjong, dietary intake, etc.), functional status (i.e., ADL, cognitive function, mental health measured by psychological resources, etc.), self-rated health and prevalence of chronic diseases (i.e., heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, diabetes, respiratory diseases, digestive disease, cancer, etc.) and other information. Meanwhile, height, weight, blood pressure, visual function, hearing function, and chewing ability were measured by qualified doctors for each participant during the interview (10), and the BMI was calculated and classified into underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese according to cut-offs for the Chinese adults (15).

Figure S1.

Selection criteria for study participants, CLHLS 1998–2018.

Abbreviation: CLHLS=Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey.

REFERENCES

Newson RS, Witteman JCM, Franco OH, Stricker BHC, Breteler MMB, Hofman A, et al. Predicting survival and morbidity-free survival to very old age. Age (Dordr) 2010;32(4):521 − 34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11357-010-9154-8.

Willcox BJ, He QM, Chen RD, Yano K, Masaki KH, Grove JS, et al. Midlife risk factors and healthy survival in men. JAMA 2006;296(19):2343 − 50. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.19.2343.

Yates LB, Djoussé L, Kurth T, Buring JE, Gaziano JM. Exceptional longevity in men: modifiable factors associated with survival and function to age 90 years. Arch Intern Med 2008;168(3):284 − 90. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2007.77.

Shadyab AH, Manson JE, Li WJ, Gass M, Brunner RL, Naughton MJ, et al. Parental longevity predicts healthy ageing among women. Age Ageing 2018;47(6):853 − 60. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afy125.

Rillamas-Sun E, LaCroix AZ, Waring ME, Kroenke CH, LaMonte MJ, Vitolins MZ, et al. Obesity and late-age survival without major disease or disability in older women. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174(1):98 − 106. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12051.

World Health Organization. Decade of healthy ageing: baseline report. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/338677. [2022-10-12].

U.S. National Academy of Medicine. Healthy longevity global grand challenge. https://healthylongevitychallenge.org/about-us/. [2022-10-18].

Dzau VJ, Jenkins JAC. Creating a global roadmap for healthy longevity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2019;74(Suppl_1):S4 − 6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glz226.

Zeng Y, Feng QS, Hesketh T, Christensen K, Vaupel JW. Survival, disabilities in activities of daily living, and physical and cognitive functioning among the oldest-old in China: a cohort study. Lancet 2017;389(10079):1619 − 29. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30548-2.

Zhou JH, Lv YB, Mao C, Duan J, Gao X, Wang JN, et al. Development and validation of a nomogram for predicting the 6-year risk of cognitive impairment among Chinese older adults. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2020;21(6):864 − 71.e6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2020.03.032.

Zhang MY, Katzman R, Salmon D, Jin H, Cai GJ, Wang ZY, et al. The prevalence of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease in Shanghai, China: impact of age, gender, and education. Ann Neurol 1990;27(4):428 − 37. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ana.410270412.

Smith J, Gerstorf D, Li Q. Psychological resources for well-being among octogenarians, nonagenarians, and centenarians: differential effects of age and selective mortality. In: Yi Z, Poston DL, Vlosky DA, Gu DN, editors. Healthy longevity in China: demographic, socioeconomic, and psychological dimensions. Dordrecht: Springer. 2008;329 − 46. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-6752-5_20.

Cao GY, Wang KP, Han L, Zhang Q, Yao SS, Chen ZS, et al. Visual trajectories and risk of physical and cognitive impairment among older Chinese adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2021;69(10):2877 − 87. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jgs.17311.

Zhang Y, Ge ML, Zhao W, Liu Y, Xia X, Hou L, et al. Sensory impairment and all-cause mortality among the oldest-old: findings from the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS). J Nutr Health Aging 2020;24(2):132 − 7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1319-2.

Chen CM, Lu FC, Department of Disease Control Ministry of Health, PR China. The guidelines for prevention and control of overweight and obesity in Chinese adults. Biomed Environ Sci 2004;17 Suppl:1-36. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15807475/.

Funding Statement

Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 82025030 and 81941023), Non-profit Central Research Institute Fund of Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (grant number 2021-JKCS-028), and Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Centers grant (grant number 5P30 AG028716 from NIA)

Contributor Information

Yuebin Lyu, Email: lvyuebin@nieh.chinacdc.cn.

Chen Mao, Email: maochen9@smu.edu.cn.

Xiaoming Shi, Email: shixm@chinacdc.cn.

References

- 1.United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division. World population prospects 2022. 2022. https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/CSV/. [2022-10-18].

- 2.World Health Organization. Decade of healthy ageing: baseline report. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/338677. [2022-10-12].

- 3.Zeng Y, Feng QS, Hesketh T, Christensen K, Vaupel JW Survival, disabilities in activities of daily living, and physical and cognitive functioning among the oldest-old in China: a cohort study. Lancet. 2017;389(10079):1619–29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30548-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sabia S, Singh-Manoux A, Hagger-Johnson G, Cambois E, Brunner EJ, Kivimaki M Influence of individual and combined healthy behaviours on successful aging. CMAJ. 2012;184(18):1985–92. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.121080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mukadam N, Sommerlad A, Huntley J, Livingston G Population attributable fractions for risk factors for dementia in low-income and middle-income countries: an analysis using cross-sectional survey data. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(5):e596–603. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30074-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Willcox BJ, He QM, Chen RD, Yano K, Masaki KH, Grove JS, et al Midlife risk factors and healthy survival in men. JAMA. 2006;296(19):2343–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.19.2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shadyab AH, Manson JE, Li WJ, Gass M, Brunner RL, Naughton MJ, et al Parental longevity predicts healthy ageing among women. Age Ageing. 2018;47(6):853–60. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afy125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li ZH, Zhang XR, Lv YB, Shen D, Li FR, Zhong WF, et al Leisure activities and all-cause mortality among the Chinese oldest-old population: a prospective community-based cohort study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(6):713–9.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arumai Selvan D, Mahendiran D, Senthil Kumar R, Kalilur Rahiman A Garlic, green tea and turmeric extracts-mediated green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: phytochemical, antioxidant and in vitro cytotoxicity studies. J Photochem Photobiol B Biol. 2018;180:243–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2018.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rillamas-Sun E, LaCroix AZ, Waring ME, Kroenke CH, LaMonte MJ, Vitolins MZ, et al Obesity and late-age survival without major disease or disability in older women. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(1):98–106. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newson RS, Witteman JCM, Franco OH, Stricker BHC, Breteler MMB, Hofman A, et al Predicting survival and morbidity-free survival to very old age. Age (Dordr) 2010;32(4):521–34. doi: 10.1007/s11357-010-9154-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]