Abstract

Objective:

The primary objective of this study was to determine the influence of rural residence on access to and outcomes of lung cancer-directed surgery for Medicare beneficiaries.

Summary Background Data:

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States and rural patients have 20% higher mortality. Drivers of rural disparities along the continuum of lung cancer-care delivery are poorly understood.

Methods:

Medicare claims (2015–2018) were used to identify 126,352 older adults with an incident diagnosis of non-metastatic lung cancer. Rural Urban Commuting Area codes were used to define metropolitan, micropolitan, small town, and rural site of residence. Multivariable logistic regression models evaluated influence of place of residence on 1) receipt of cancer-directed surgery 2) time from diagnosis to surgery, and 3) postoperative outcomes.

Results:

Metropolitan beneficiaries had higher rate of cancer directed surgery (22.1%) than micropolitan (18.7%), small town (17.5%), and isolated rural (17.8%) (p <0.001). Compared to patients from metropolitan areas, there were longer times from diagnosis to surgery for patients living in micropolitan, small, and rural communities. Multivariable models found non-metropolitan residence to be associated with lower odds of receiving cancer-directed surgery and MIS. Non-metropolitan residence was associated with higher odds of having postoperative emergency department visits.

Conclusions:

Residence in non-metropolitan areas is associated with lower probability of cancer-directed surgery, increased time to surgery, decreased use of MIS, and increased postoperative ED visits. Attention to timely access to surgery and coordination of postoperative care for non-metropolitan patients could improve care delivery.

Mini-Abstract

Although nearly 20% of Americans live in rural communities, little is known about disparities in lung cancer care for rural patients. This study evaluates Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed with incident lung cancer from 2015 through 2018. Non-metropolitan place of residence was associated with decreased odds of receiving cancer directed surgery, delayed time to surgery, and higher odds of postoperative visit to an emergency department.

INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer related death in the United States, but its impact varies considerably across the country, with a 20% higher per capita mortality for patients living in non-metropolitan areas.1 Beyond differential smoking rates and lung cancer incidence, there is increasing recognition that where one lives plays an important role in cancer care delivery, especially for the 20% of Americans who reside in non-metropolitan communities.2–5 However, little is understood as to how rural place of residence influences care delivery for patients with lung cancer across the care continuum from diagnosis through postoperative care.

Multiple factors contribute to rural-urban disparities in cancer care outcomes, including rates of smoking, utilization of cancer screening, rates of referral to specialist, and receipt of optimal care.6,7 Similar trends are present for the timely diagnosis and treatment for lung cancer. Residents in nonmetropolitan areas are one third more likely to smoke and have less access to smoking cessation programs.8,9 Furthermore, lung cancer screening rates have been shown to be lower in rural communities and, as a consequence, rural patients are less likely to be diagnosed with earlier stage disease.10,11 Early data also suggest differential adoption of minimal invasive surgery for lung cancer across geographic regions in the United States.12 However, few studies have tracked the receipt of cancer care, the travel patterns for patients undergoing cancer-directed surgery, and costs across the continuum of lung cancer care based on rurality.

The objective of this study is to describe the influence of rural residence on receipt of cancer directed surgery, timing from diagnosis to curative intent surgery, postoperative readmissions or emergency room visits, and 90-day morbidity and mortality. We hypothesize that rural residence will be associated with longer time between diagnosis and surgery, decreased probability of cancer-directed surgery, and increased postoperative complications. Secondary analyses will compare differential location of lung cancer surgery based on patient residential location as well as spending for lung cancer patients residing in rural compared to urban communities.

METHODS

We used national Medicare claims data from 2015 through 2018 to build the study cohort of beneficiaries with newly diagnosed lung cancer (Supplementary Figure 1). Using validated algorithms, incident lung cancer diagnosis was determined using International Classification of Disease (ICD) 10th Edition diagnosis codes for primary lung cancer as well as Current Procedure Terminology (CPT) codes that indicate cancer treatment (Supplementary Table 1 and 2).13,14 Inclusion as an incident cancer required 1) at least one cancer ICD diagnosis OR outpatient visit with a CPT code related to chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or cancer-directed surgery; 2) at least two cancer ICD diagnosis codes either on different dates within 60 days of one another or within 12 months following a biopsy; or 3) one cancer ICD diagnosis code within 14 days of a complication and one within the following 12 months. We excluded nursing home residents, patients under the age of 65 years, patients with end stage renal disease, patients with metastatic disease, and patients with other primary cancers. We established a “run in period” between October 1, 2015 and March 31, 2016 to exclude any prevalent lung cancer. Additionally, we used Hierarchical Condition Category (HCC) coding to exclude patients with any cancer diagnosis during 2015. The study period ran from April 1, 2016 through December 31, 2018.

Place of residence was determined using each beneficiary’s 5-digit zip-code at the time of diagnosis. Zip codes were used to determine the Rural-Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) codes as determined by the United States Department of Agriculture.15 RUCA codes classify census tracts based on population density, urbanization, and daily community practices of residence. We used definitions of metropolitan (RUCA codes 1–3), micropolitan (RUCA codes 4–6), small town (RUCA codes 7–9), and rural (RUCA code 10).

These same codes were used to classify location of surgical practices where patients received cancer-directed surgery. We used zip-code centroid as the location of each facility where patients underwent surgery. Practice location was classified as metropolitan, micropolitan, or small town/rural. For comparison of travel patterns, we combined small town and rural areas for both patient residential location and surgical practice location. This combination occurred because of small numbers of patients receiving surgical care in either small towns or rural locations. Distance travelled for surgical resection was determined by zip-code centroid to centroid straight-line distance in miles.

The primary outcomes for this study include receipt of cancer-directed surgery, time from diagnosis to surgery, receipt of minimally invasive surgery, and 90-day morbidity and mortality. Minimally invasive surgery compared to open surgery was determined using CPT codes (Supplementary Table 3). 90-day morbidity was determined from date of surgery and included postoperative urinary tract complication (e.g. renal failure), pulmonary compromise, gastrointestinal hemorrhage following non-gastrointestinal surgery, myocardial infarction, pneumonia, venous thromboembolism or pulmonary embolism, post-operative hemorrhage or hematoma, wound infection, and delirium (Supplementary Table 4). Secondary outcomes included presentation to an emergency department and readmission within 90 days of discharge from index operations. Additionally, total price-adjusted spending was determined for each beneficiary in the 90 days following surgery.16

Baseline characteristics were compared using chi-squared and non-parametric testing. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to determine the influence of place of residence on outcomes. All models controlled for patient age, sex, race, comorbidities, dual Medicare and Medicaid enrollment status, community-level measures of socioeconomic deprivation, and patient disability status. Age strata were used including age 65–74 years, 75–84 years, and 85 years and older. Race was classified as White, Black, Hispanic, and Other as captured in Medicare data. Race/ethnicity in the Medicare data is self-reported by beneficiaries.17 We included race/ethnicity in the model to account for systemic racism that contributes to patient access and receipt of care. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Hierarchical Condition Category (HCC) codes were used to adjust for comorbidities. Consistent with prior studies on lobectomy in Medicare patients, we used the HCC risk scores is a composite measure that weights comorbidities and demographics on their role in determining expenses in the year, which in turn is correlated with outcomes.18 The Area Deprivation Index, a composite of 17 individual measures of socioeconomic resources related to employment, housing, food availability, segregation, was determined at the level of the 9-digit zip code.19 The index ranges from 1 to 100, with higher values representing greater degrees of a socioeconomic deprivation. We used the ADI as a continuous variable in final models. Cox proportional-hazards regression models were used to evaluate the influence of place of residence on the time between diagnosis and receipt of cancer-directed surgery.

Additional sensitivity models included adjustment for receipt of neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiation within 60-days of surgery, receipt of minimally invasive surgery, as well as individual comorbidities, specifically diabetes, prior myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, stroke or transient ischemic attack, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, liver, or kidney disease.

All analyses were performed using SAS (Cary, NC). P-values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant. This study was deemed exempt from IRB review.

RESULTS

Our final cohort included 126,352 beneficiaries with incident, non-metastatic lung cancer diagnosis, including 26,603 who underwent cancer-directed surgery (see Supplementary Figure 1 for exclusions). Approximately 74% of patients resided in metropolitan areas, followed by 13% in micropolitan, 7% in small town, and 5% in rural communities (Table 1). Patients in metropolitan areas were slightly older, more likely female and White. Metropolitan beneficiaries had lower average ADI (43 points compared to 62–67 points for non-metropolitan communities). Additional evaluation demonstrated similar differences when evaluating patient characteristics by hospital location (Supplementary Table 5). Patients undergoing surgery at non-metropolitan hospitals had similar age distribution but were more likely to be male, White, have both Medicare and Medicaid coverage, and come from communities with higher degree of social deprivation.

Table 1.

Cohort demographic and clinical characteristics

| All Patients n=126,352 | Metropolitan n=93,713 | Micropolitan n=16,758 | Small Town n=9,303 | Rural n=6,578 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age n (%) | ||||

| 65–74 | 46,145 (49.2) | 9,044 (54.0) | 4,992 (53.7) | 3,455 (52.5) |

| 75–84 | 36,313 (38.8) | 6,156 (36.7) | 3,440 (37.0) | 2,550 (38.8) |

| >85 | 11,255 (12.0) | 1,558 (9.3) | 871 (9.4) | 573 (8.7) |

| Female n (%) | 49,251 (52.6) | 8,078 (48.2) | 4,472 (48.1) | 3,126 (47.5) |

| Race/Ethnicity n (%) | ||||

| White | 81,632 (87.1) | 15,366 (91.7) | 8,578 (92.2) | 6,114 (93.0) |

| Black | 6,212 (6.6) | 708 (4.2) | 408 (4.4) | 157 (2.4) |

| Hispanic | 2,539 (2.7) | 320 (1.9) | 121 (1.3) | 56 (0.9) |

| Other | 3,330 (3.6) | 364 (2.2) | 196 (2.1) | 251 (3.8) |

| Comorbidity Score mean (std) | 0.9 (0.8) | 0.9 (0.8) | 0.9 (0.8) | 0.9 (0.8) |

| Medicare & Medicaid n (%) | 6,079 (6.5) | 1,269 (7.6) | 802 (8.6) | 629 (9.6) |

| Area Deprivation Index mean (std) | 43.0 (26.4) | 62.3 (21.1) | 67.0 (19.3) | 65.1 (19.2) |

Incidence of major comorbidities were similar between areas. Receipt of neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiation within 60 days was uncommon and similar across regions (metropolitan 4.6%; micropolitan 4.1%; small town 3.4%; and rural 4.0%). The overall, 90-day mortality for all patients from the time of diagnosis was 17.6%. The regional 90-day mortality was lowest for metropolitan areas (16.8%) followed by micropolitan areas (19.8%), small town (20.5%), and rural areas (20.2%).

Overall, 26,603 patients (21.1%) underwent cancer-directed surgery. Of these, 16,741 patients (62.9%) underwent resection via a minimally invasive approach. The 90-day complication rate was 31.2%, with the most frequent complications being pulmonary compromise (n=4,247, 16.0%), urinary tract complication including urinary tract infection or renal insufficiency (n=2,771; 10.4%), and postoperative pneumonia (n=2,302; 8.7%). Death within 90 days of surgery occurred in 1,034 patients (3.9%). In surgical patients, presentation to an emergency department or being readmitted within 90 days of discharge occurred for 6,897 (25.9%) and 4,505 (16.9%) patients, respectively.

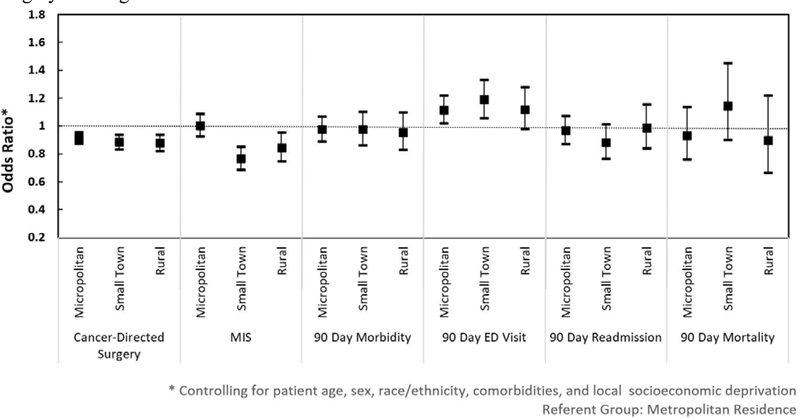

Patients residing in metropolitan areas had greater probability of having cancer-directed surgery (n=20,677; 22.1%) than patients living in micropolitan (n=3,126; 18.7%), small town (n=1,626; 17.5%), or rural communities (n=1,174; 17.8%). After controlling for confounding factors, patients in micropolitan, small town, and rural communities were each significantly less likely to undergo cancer-directed surgery compared to those living in metropolitan areas (Figure 1). Among patients undergoing cancer-directed surgery, residence in small town and rural areas was significantly associated with decreased odds of having minimally invasive approach (OR 0.77, 95% CI (0.69–0.85); OR 0.84, 95% CI (0.75–0.95), respectively). Full regression output is demonstrated in Supplementary Table 6.

Figure 1.

Influence of place of residence on receipt of and outcomes from cancer-directed surgery for lung cancer.

* Controlling for patient age, sex, race/ethnicity, comorbidities, and local socioeconomic deprivation

Referent group: Metropolitan residence

Between 90 and 92% of patients who underwent surgery had this resection within 90 days of diagnosis. However, patients in micropolitan, small town, and rural communities were more likely to have surgery between 30 and 90 days from diagnosis while patients from metropolitan areas were more likely to have surgery within 30 days (Table 2). The median number of days from time of diagnosis to surgery was lowest for patients from metropolitan areas (28 days) followed by micropolitan (32 days), small towns (31 days), and rural areas (31 days). Cox-Proportional Hazard models confirmed a statistically significant association between geographic area of residence and time to cancer-directed surgery, with greater time from diagnosis to surgery for patients living in micropolitan (Hazard Ratio 1.07; 95% CI 1.03–1.16), small town (HR 1.10; 95% CI 1.04–1.16), and rural communities (HR 1.11; 95% CI 1.05–1.18).

Table 2.

Distribution of outcomes for patients diagnosed with and undergoing cancer-directed surgery for lung cancer

| All Patients n=126,352 |

Metropolitan n=93,713 (74.2%) |

Micropolitan n=16,758 (13.3%) |

Small Town n=9,303 (7.4%) |

Rural n=6,578 (5.2%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer Directed Surgery n (%) | 20,677 (22.1%) | 3,126 (18.7%) | 1,626 (17.5%) | 1,174 (17.8) |

| Time to surgery n (%) | ||||

| Diagnosis made at time of surgery | 396 (1.9) | 69 (2.2) | 31 (1.9) | 21 (1.8) |

| <30 days | 10,425 (50.4) | 1,442 (46.1) | 767 (47.2) | 563 (48.0) |

| 31–60 days | 5,708 (27.6) | 948 (30.3) | 520 (32.0) | 338 (28.8) |

| 61–90 days | 2,042 (9.9) | 353 (11.3) | 177 (10.9) | 144 (12.3) |

| >90 days | 2,106 (10.2) | 314 (10.0) | 131 (8.1) | 108 (9.2) |

| Minimally invasive approach n (%) | 13,441 (65.0) | 1,843 (59.0) | 826 (50.8) | 631 (53.8) |

| 90-day Morbidity n (%) | 4,686 (22.7) | 764 (24.4) | 410 (25.2) | 285 (24.3) |

| 90-day ED visit n (%) | 5,171 (25.0) | 895 (28.6) | 494 (30.4) | 337 (28.7) |

| 90-day Readmission n (%) | 3,477 (16.8) | 549 (17.6) | 270 (16.6) | 209 (17.8) |

| 90-day Mortality n (%) | 765 (3.7) | 131 (4.2) | 89 (5.5) | 49 (4.2) |

| Cost of Care mean (SD) | $32,981 ($24,916) | $33,558 ($25,253) | $35,235 ($29,824) | $34,747 ($34,456) |

Patients from metropolitan areas traveled a median of 10.6 miles to the site of surgery compared to the median distances of 40.6 miles for micropolitan patients and 51.9 miles for patients from small town or rural communities (Table 3). Over 85% of patients in small town or rural communities traveled a median of 56.1 miles to receive care in metropolitan hospitals whereas 99.2% of metropolitan patients traveled an average of 10.5 miles to undergo surgery. 19.2% of micropolitan patients and 14.1% of small town or rural patients also received surgical care at non-metropolitan hospital as compared to only 0.8% of patients from metropolitan areas.

Table 3.

Variation in the location of surgical resection by Medicare beneficiary residential location

| Beneficiary Location | Practice Location | ||||

| Non-Rural | Rural | ||||

| All Practice Locations | Metropolitan | Micropolitan | Small Town/Rural | ||

|

Metropolitan n=20,282 (77.7%) % patients, median distance traveled |

10.6 mi |

99.2% 10.5 mi |

0.3% 27.4 mi |

0.1% 19.3 mi |

|

|

Micropolitan n=3,071 (11.8%) |

40.6 mi |

80.8% 47.7 mi |

18.5% 8.7 mi |

0.7% 37.5 mi |

|

|

Small Town/Rural n=2,759 (10.6%) |

51.9 mi |

85.9% 56.1 mi |

12.4% 30.2 mi |

1.7 % 14.7 mi |

|

Darker shade indicates beneficiary and practice locations are same category.

Residence in micropolitan areas or small towns was associated with significantly greater odds of having a visit to an emergency department within 90-days from discharge (OR 1.16, 95% CI (1.02–1.22); OR 1.19 (1.06–1.33), respectively). The higher odds of postoperative visit to emergency department for patients in rural communities did not reach statistical significance (OR 1.12 (0.98–1.28). There was no statistically significant association between place of residence and 90-day morbidity, mortality, or readmission to hospital. Evaluation of overall price-adjusted spending in the first 90 days after surgery found the mean standardized spending per patient to be $33,264 (S.D. $25,778). Average standardized spending was similar between geographic areas although with widening standard deviation in small town and rural areas (Table 2).

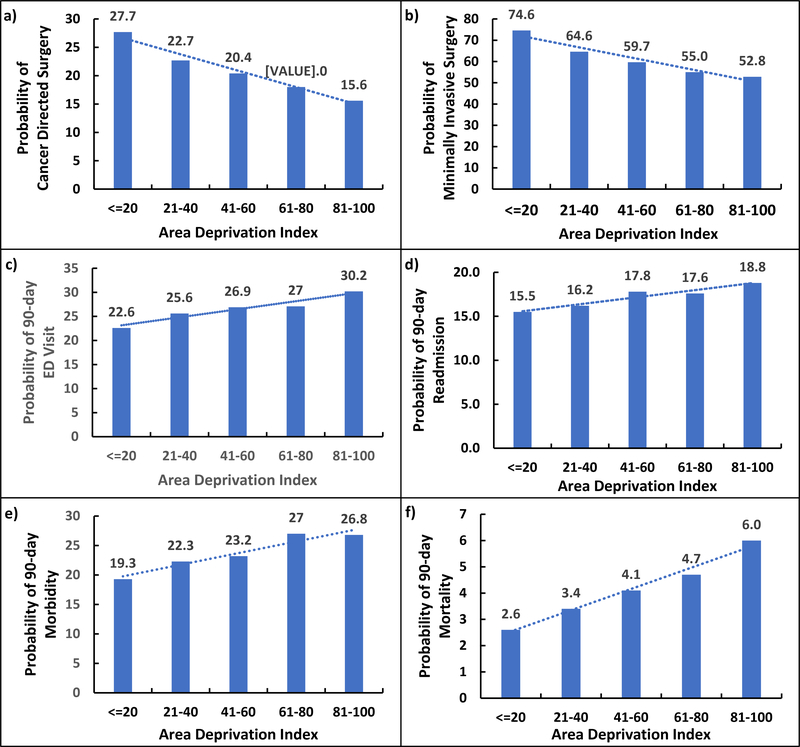

Additionally, we found a statistically significant association between increasing deprivation and decreased odds of cancer-directed surgery and minimally invasive surgery. Increasing deprivation was also associated with increased odds of 90-day postoperative morbidity, ED presentation, readmission, and mortality (Figure 2). ADI was incorporated into models as a continuous variable and as such each additional point in the ADI was associated with a relatively modest though significant increase or decrease in outcomes. Increasing deprivation was associated with decreased odds of cancer directed and minimally invasive surgery (OR 0.99; 95% CI (0.99 – 0.99); OR 0.99 (0.99–0.99), respectively). Increasing deprivation was also associated with increased odds of 90-day morbidity and mortality (OR 1.00 (1.00 – 1.00); OR 1.01 (1.01–1.01)), respectively. Exploration of relationship between deprivation and outcomes showed a linear relationship rather than clear threshold point after which the ADI was more strongly associated with outcomes.

Figure 2.

Relationship between increasing Area Deprivation Index and a) receipt of cancer directed surgery, b) minimal invasive surgery, c) 90-day visit to an Emergency Department, d) 90-day readmission, e) 90-day morbidity, and f) 90-day mortality

Sensitivity analysis accounting for neoadjuvant chemotherapy, radiation, minimal invasive surgery, and individual comorbidities were consistent with primary findings (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

This large national study of all Medicare beneficiaries with incident diagnoses of non-metastatic lung cancer in 2016–2018 found that non-metropolitan place of residence was associated with decreased odds of undergoing cancer-directed surgery. In those who underwent cancer directed surgery, we observed decreased odds of receiving a minimally invasive approach and increased time between diagnosis and surgery for non-metropolitan patients. For those patients who did undergo surgery, non-metropolitan patients traveled significant farther to undergo surgery in metropolitan areas but still had significantly greater probability of undergoing surgery in non-metropolitan hospital. Furthermore, postoperative patients in micropolitan or small town communities also had significantly increased odds of presentation to the emergency department after discharge. Collectively, these data show that non-metropolitan residence is associated with decreased access to and receipt of cancer-directed surgery. For those that do ultimately undergo cancer-directed surgery, our findings show potential challenges in postoperative care coordination resulting in increased use of the emergency department after surgery. However, we found no significant association between place of residence and 90-day postoperative morbidity or mortality.

Disparities in lung cancer care have been well documented by patient race/ethnicity as well as insurance and socioeconomic status. The National Lung Screening Trial found both higher incidence of lung cancer and increased rates of occupational exposure for African Americans compared to White individuals.20 Similarly, Black patients have also been found to have decreased odds of undergoing surgery for non-small cell lung cancer compared to White patients.21 Overall racial disparities in mortality after cancer surgery have remain unchanged over past decade.22 Insurance-based disparities also persist, with uninsured and Medicaid patients having significantly lower odds of undergoing cancer-directed surgery and having worse outcomes compared to privately insured patients.23 However, far less is known about lung cancer surgery for rural patients.

Our findings build on a growing body of work evaluating disparities in healthcare delivery for rural patients. There has been an increasing incidence of and geographic disparities in select early onset cancer for patients residing in rural communities compared to their urban counterparts.24 Despite declining mortality rates for cancer across all regions, disparities in cancer mortality remain for rural populations.25 Limited access to specialty care, including surgery, has been well documented. For instance, rural counties have 80% lower odds of having a hospital that performs emergency general surgery.26 These compounding factors across the continuum of cancer care contribute to persistent rural disparities.

Our results have important implications for lung cancer care and equitable outcomes for rural patients. Our findings may be explained by several factors, including decreased access to preventive care and screening for rural Americans and challenges in traveling increasingly far distances to receive surgical treatment.8–10,27 Consequently, patients are less likely to be diagnosed with early-stage lung cancer and have increased distance barriers to surgical care.11 While we attempted to identify only patients with non-metastatic incident lung cancer, part of our decreased receipt of cancer-directed surgery could be related to more advanced or unresectable disease not captured in claims data. Alternatively, rural patients may be less likely to receive or accept recommendation for surgery.

Over 80% of non-metropolitan patients had to travel a median 47.7 to 56.1 miles to metropolitan areas for surgery, compared to the over 99% of metropolitan patients who traveled a median of 10.5 miles to undergo surgery in metropolitan hospitals. With closures of rural hospitals and centralization of complex operations at high surgical volume hospitals, these forces in non-metropolitan communities are likely to continue to grow.28 19.2% of micropolitan patients and 14.1% of small town or rural patients stayed within non-metropolitan areas for their surgical treatment, compared to less than 1% of metropolitan patients who traveled to similar hospitals for surgery. While beyond the scope of this study, analysis is warranted to understand the influence of non-metropolitan practice location on outcomes of lung cancer directed surgery care. While minimally invasive surgery, compared to open operations, may not provide superior oncologic outcomes, the significant disparity in receipt of minimal invasive surgery could represent decreased access to higher volume surgeons or centers adopting newer technology. This in turn could have implications for both perioperative outcomes and multimodal therapy across the continuum of cancer care.

The fragmentation of care extends beyond timely receipt of cancer-directed surgery to include coordination of postoperative care. Our findings of increased odds of presenting to an emergency department suggest significant challenges in post-acute care coordination that could prevent emergency department presentation. We did not evaluate the geographic location of emergency departments or other characteristics of these locations providing postoperative care. Furthermore, we did not evaluate whether there was increased admission vs discharge from these emergency departments after evaluation. We suspect that these findings are secondary to non-metropolitan patients being evaluated in local emergency departments for postoperative issues rather than travelling greater distance to place of their original surgery. Our findings of no significant association between place of residence and 90-day morbidity and mortality suggest that the care that non-metropolitan patients are receiving is safe. This builds on prior work showing that when patients with lung cancer receive indicated surgical care, both perioperative and oncologic outcomes improve.20,22 However, we did not specifically evaluate whether cancer-directed surgery was performed at high surgical volume hospitals or with a high-volume surgeon, both of which would have been associated with improved perioperative and oncologic outcomes.29–31

In addition to the geographic impact of rural place of residence, we also found that increasing local area deprivation was associated with deleterious outcomes. Multiple intersecting drivers of inequity in lung cancer care are likely at play, including rurality, local area deprivation, patient-level income and comorbidities, in addition to overlay of systemic and interpersonal racism (Supplementary Figure 2). Although our measured Odds Ratios suggest small impact, we used the Area Deprivation Index as a continuous variable ranging from 1–100. Evaluation of relationship between increasing quintiles of ADI and outcomes demonstrate a more striking association (Figure 2). This is consistent with prior work showing association between community-level socioeconomic factors and receipt of surgical oncology care.32 Hyer and colleagues recently evaluated Medicare patients with four solid organ malignancies (including lung) and reported that increasing social vulnerability was associated with decreased probability of achieving “textbook outcomes” after cancer surgery.33 Minority patients experienced a particularly strong association with adverse outcomes at higher levels of community-level social vulnerability. However, this prior study did not specifically evaluate the interaction between social vulnerability and rural place of residence. Other work within a single New England state found that local ADI and not rurality was associated with increased prevalence of and mortality from lung cancer.34 This is contrary to our study where both ADI and rural residence were independently associated with multiple outcomes, possibly reflecting differences in the relationship between deprivation and rurality depending on a specific region and noting that we did not evaluate relative differences in cancer incidence.

This study should be considered in the context of its unique strengths and limitations. The use of 100% Medicare claims capture a national cohort of patients with the added ability to track care received over time, including time of diagnosis, time to surgical intervention, and long-term postoperative care and intervention. Medicare claims data alone are unable to completely capture or account for stage at diagnosis. However, this analysis did exclude patients presenting with metastatic disease which can be determined from claims. Previous work using state-based cancer registries, the American College of Surgeons National Cancer DataBase (NCDB), and Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) data have evaluated geographic disparities in stage of cancer at diagnosis, but these datasets do not capture the heterogeneity of rurality across the country.3–5,35,36 The NCDB captures data only from American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer Accredited programs and while the SEER database is population-based, it is only a geographic sampling of the country. Additionally, cancer registries have limited ability to track the full continuum of lung cancer care from diagnosis to treatment and clinical outcomes. Additional studies using the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) National Inpatient Sample have documented surgical outcomes such as postoperative morbidity, mortality, and readmission.37 However, they do not allow for tracking of care before and after inpatient hospitalization, omitting considerable points along the care continuum during which improvement could be targeted.

We also recognize limitations to this study. Our evaluation included only patients older than 65 years and with Medicare coverage. As such, these findings may not be generalizable to patients younger than 65 years and those with non-Medicare insurance coverage. Furthermore, our use of claims data has limited oncologic granularity that prevents us from reliably determining patient stage at diagnosis or individual patient-level appropriateness of surgical intervention. Our use of previously validated methodology to identify incident cancer diagnoses in claims data minimized but does not eliminate potential for coding errors. In determining the travel distance to location of surgical resection, we established zip-code centroid to centroid distances which may not represent the true travel time between locations. Additional work evaluating travel time may provide more precise estimations the travel burdens of rural patients for surgery or specialty care. Our straight-line distance estimates likely underestimate the actual travel burdens patients experience. Finally, our work evaluated for differential patterns of care and outcomes by patient location. Future work will be focused on evaluating differential care delivery and outcomes based on rurality of practice locations.

In conclusion, this national study of Medicare beneficiaries with lung cancer found considerable rural/geographic disparities in receipt of surgical care for lung cancer and fragmented postoperative care resulting in higher utilization of emergency departments in the 90 days after surgery. Additional policies and care delivery improvements should be focused on increasing timely access to surgical evaluation and planning, especially for those in rural areas. Explicit attention should be given to the unique challenges of coordinating care after discharge to improve the equity of lung cancer care for rural patients.

Supplementary Material

Financial Support:

This work was supported through NIH (NCI R37 CA248470-01)

REFERENCES

- 1.Moy E, Garcia MC, Bastian B, Rossen LM, Ingram DD, Faul M, Massetti GM, Thomas CC, Hong Y, Yoon PW, Iademarco MF. Leading Causes of Death in Nonmetropolitan and Metropolitan Areas- United States, 1999–2014. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017. Jan 13;66(1):1–8. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6601a1. Erratum in: MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017 Jan 27;66(3):93. PMID: 28081058; PMCID: PMC5829895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh GK, Siahpush M. Widening rural-urban disparities in life expectancy, U.S., 1969–2009. Am J Prev Med. 2014. Feb;46(2):e19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.017. PMID: 24439358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hashibe M, Kirchhoff AC, Kepka D, Kim J, Millar M, Sweeney C, Herget K, Monroe M, Henry NL, Lopez AM, Mooney K. Disparities in cancer survival and incidence by metropolitan versus rural residence in Utah. Cancer Med. 2018;7(4):1490–7. Epub 2018/03/14. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zahnd WE, James AS, Jenkins WD, Izadi SR, Fogleman AJ, Steward DE, Colditz GA, Brard L. Ruralurban differences in cancer incidence and trends in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2018;27(11):1265–74. Epub 2017/07/29. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.Epi-17-0430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson AM, Hines RB, Johnson JA 3rd, Bayakly AR. Treatment and survival disparities in lung cancer: The effect of social environment and place of residence. Lung Cancer. 2014;83(3):401–7. Epub 2014/02/05. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adler NE, Newman K. Socioeconomic disparities in health: pathways and policies. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002. Mar-Apr;21(2):60–76. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.60. PMID: 11900187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Williams DR, Pamuk E. Socioeconomic disparities in health in the United States: what the patterns tell us. Am J Public Health. 2010. Apr 1;100 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S186–96. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.166082. Epub 2010 Feb 10. PMID: 20147693; PMCID: PMC2837459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jenkins WD, Matthews AK, Bailey A, Zahnd WE, Watson KS, Mueller-Luckey G, Molina Y, Crumly D, Patera J. Rural areas are disproportionately impacted by smoking and lung cancer. Prev Med Rep. 2018. Mar 24;10:200–203. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.03.011. PMID: 29868368; PMCID: PMC5984228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Odahowski CL, Zahnd WE, Eberth JM. Challenges and Opportunities for Lung Cancer Screening in Rural America. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019. Apr;16(4 Pt B):590–595. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2019.01.001. PMID: 30947892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin AN, Hassinger TE, Kozower BD, Camacho F, Anderson RT, Yao N. Disparities in Lung Cancer Screening Availability: Lessons From Southwest Virginia. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019. Aug;108(2):412–416. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2019.03.003. Epub 2019 Apr 2. PMID: 30951691; PMCID: PMC6666421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paquette I, Finlayson SR. Rural versus urban colorectal and lung cancer patients: differences in stage at presentation. J Am Coll Surg. 2007. Nov;205(5):636–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.04.043. Epub 2007 Aug 8. PMID: 17964438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phillips JD, Bostock IC, Hasson RM, Goodney PP, Goodman DC, Millington TM, Finley DJ. National practice trends for the surgical management of lung cancer in the CMS population: An atlas of care. J Thorac Dis. 2019;11(Suppl 4):S500–S508. PMID: 31032068; PMCID: PMC6465423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Setoguchi S, Solomon DH, Glynn RJ, Cook EF, Levin R, Schneeweiss S. Agreement of diagnosis and its date for hematologic malignancies and solid tumors between Medicare claims and cancer registry data. Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18(5):561–9. Epub 2007/04/21. doi: 10.1007/s10552-007-0131-1. PMID: 17447148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bronson MR, Kapadia NS, Austin AM, Wang Q, Feskanich D, Bynum JPW, Grodstein R, Tosteson ANA. Leveraging linkage of cohort studies with administrative claims data to identify individuals with cancer. Med Care. 2018;56:e83–e89. PMID: 29334524. PMCID: PMC6043405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.US Department of Agriculture. Rural-urban commuting area codes. http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes. Accessed January 18, 2019.

- 16.Gottlieb DJ, Zhou W, Song Y, Gilman Andrews K, Skinner JS, Sutherland JM. Prices don’t drive regional Medicare spending variations. Health Affairs. 2010;29(3):537–543. PMID: 20110290. PMCID: PMC2919810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jarrin OF, Nyandege AN, Grafova IB, Dong X, Lin H. Validity of race and ethnicity codes in Medicare administrative data compared with gold-standard self-reported race collected during routine home health care visits. Med Care. 2020;58:e1–e8. PMID: 31688554. PMCID: PMC6904433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehta HB, Dimou F, Adhikari D, Tamirisa NP, Sieloff E, Williams TP, Kuo YF, Riall TS. Comparison of comorbidity scores in predicting surgical outcomes. Med Care. 2016;54:180–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kind AJ, Jencks S, Brock J, et al. Neighborhood Socioeconomic Disadvantage and 30-Day Rehospitalization: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med. 2014; 161:765–774. Doi: 10.7326/M13-2946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Juon HS, Hong A, Pimpinelli M, Rojulpote M, McIntire R, Barta JA. Racial disparities in occupational risks and lung cancer incidence: Analysis of the National Lung Screening Trial. Preventive Medicine. 2021;143: 106355. Published ahead of print. Available at: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolf A, Alpert N, Tran BV, Liu B, Flores R, Taioli E. Persistence of racial disparities in early-stage lung cancer treatment. J Torac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;157(4):1670–1679. PMID: 30685165. PMCID: PMC6433143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lam MB, Raphael K, Mehtsun WT, Phelan J, Orav EJ, Jha AK, Figureroa JF. Changes in racial disparities in mortality after cancer surgery in the US, 2007–2016. JAMA Netw Open.2020;3(12):e2027415. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.27415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stokes SM, Wakeam E, Swords DS, Stringham JR, Varghese TK. Impact of insurance status on receipt of definitive surgical therapy and posttreatment outcomes in early-stage lung cancer. Surgery.2018;164:1287–1293. PMID 30170821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zahnd WE, Gomez SL, Steck SE, Brown MJ, Ganai S, Zhang J, Adams SA, Berger FG, Eberth JM. Rural-urban and racial/ethnic trends and disparities in early-onset and average-onset colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2021127:239–248.PMID 33112412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yao N, Alcala HE, Anerson R, Balkrishnan R. Cancer disparities in rural Appalachia: Incidence, early detection, and survivorship. J Rural Health. 2016;33:375–381. PMID: 27602545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khubchandani JA, Shen C, Ayturk D, Kiefe CI, Santry HP. Disparities in access to emergency general surgery care in the United States. Surgery. 2018;163:243–250. PMID: 29050886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diaz A, Schoenbrunner A, Pawlick TM. Trends in the geospatial distribution of inpatient adult surgical services across the United States. Ann Surg. 2021;273:121–127. PMID: 31396841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Germack HD, Kandrack R, Martsolf GR. When rural hospitals close, the physician workforce goes. Health Affairs. 2019;38(12):2086–2094. PMID 31794309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.von Meyenfeldt EM; Gooiker GA, van Gijn W, Post PN, van de Velde CJH, Tollenaar RAEM, Klomp HM, Wouters MWJM. The relationship between volume or surgeron specialty and outcome in the surgical treatment of lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thorar Oncol.2012;7:1170–1178. PMID: 22617248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park HS, Detterbeck FC, Boffa DJ, Kim AW. Impact of hospital volume of thoracoscopic lobectomy on primary lung cancer outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93:372–380. PMID: 21945225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ellis MC, Diggs BS, Vetto JT, Schipper PH. Intraoperative oncologic staging and outcomes for lung cancer resection vary by surgeon specialty. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:1958–1964. PMID: 21962260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diaz A, Chavarin D Paredes AZ, Tsilimigras DI, Pawlick T. Association of neighborhood characteristics with utilization of high-volume hospitals among patients undergoing high-risk cancer surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28:617–631. PMID: 32699923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hyer JM, Tsilimigras DI, Diaz A, Mirdad RS, Azap RA, Cloyd J, Dilhoff M, Ejaz A, Tsung A, Pawlick T. High social vulnerability and “textbook outcomes” after cancer operation. J Am Coll Surg. 2021. Published ahead of print. Available at: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.11.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fairfield KM, Black AW, Ziller EC, Murray K, Lucas FL, Waterston LB, Korsen N, Ineza D, Han PKJ. Area deprivation index and rurality in relation to lung cancer prevalence and mortality in a rural state. JNCI Cancer Spect. 2020;4(4) pkaa011. doi: 10.1093/jncics/pkaa011. eCollection 2020 Aug. PMID: 32676551. PMCID: PMC7353952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steele CB, Pisu M, Richardson LC. Urban/rural patterns in receipt of treatment for non-small cell lung cancer among black and white Medicare beneficiaries, 2000–2003. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103(8):711–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuo TM, Mobley LR. How generalizable are the SEER registries to the cancer populations of the USA? Cancer Causes Control. 2016;27(9):1117–26. Epub 2016/07/23. doi: 10.1007/s10552-016-0790-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Markin A, Habermann EB, Chow CJ, Zhu Y, Vickers SM, Al-Refaie WB. Rurality and cancer surgery in the United States. Am J Surg. 2012;204(5):569–73. Epub 2012/08/22. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2012.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.