Abstract

Background

Moral distress is a common challenge among professional nurses when caring for their patients, especially when they need to make rapid decisions. Therefore, leaving moral distress unconsidered may jeopardize patient quality of care, safety, and satisfaction.

Aim

To estimate moral distress among nurses.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis conducted systematic search in Scopus, PubMed, ProQuest, ISI Web of Knowledge, and PsycInfo up to end of February 2022. Methodological quality of included studies was assessed using the Newcastle Ottawa checklist. Data from included studies were pooled by meta-analysis with random effect model in STATA software version 14. The selected key measure was mean score of moral distress total score with its’ 95% Confidence Interval was reported. Subgroup analyses and meta-regressions were conducted to identify possible sources of heterogeneity and potentially influencing variables on moral distress. Funnel plots and Begg’s Tests were used to assess publication bias. The Jackknife method was used for sensitivity analysis.

Ethical consideration

The protocol of this project was registered in the PROSPERO database under decree code of CRD42021267773.

Results

Eighty-six manuscripts with 19,537 participants from 21 countries were included. The pooled estimated mean score of moral distress was 2.55 on a 0–10 scale [95% Confidence Interval: 2.27–2.84, I2: 98.4%, Tau2:0.94]. Publication bias and small study effect was ruled out. Moral distress significantly decreased in the COVID-19 pandemic versus before. Nurses working in developing countries experienced higher level of moral distress compared to their counterparts in developed countries. Nurses' workplace (e.g., hospital ward) was not linked to severity of moral disturbance.

Conclusion

The results of the study showed a low level of pooled estimated score for moral distress. Although the score of moral distress was not high, nurses working in developing countries reported higher levels of moral distress than those working in developed countries. Therefore, it is necessary that future studies focus on creating a supportive environment in hospitals and medical centers for nurses to reduce moral distress and improve healthcare.

Keywords: Moral distress, nurses, COVID-19 pandemic, systematic review, meta-analysis

Introduction

Moral distress impacts health care professionals, including nurses, globally. 1 Moral distress is frequently encountered by professional nurses when caring for patients, especially when they need to make rapid decisions as patient advocates. 2 Moral distress may co-occur with frustration, anger, and painful emotions, and if left unidentified and unaddressed, may jeopardize patient care, safety, and satisfaction. 3 Nurses may inadvertently reduce patient support by not fully attending to patient’s suffering and avoiding certain patient requests or needs, thereby undermining health outcomes. 4 Moral distress has been associated with increased stress, workplace fatigue, impaired inter-professional relationships, job burnout, and reduced nurse satisfaction, and these may ultimately lead to leaving the workplace or leaving the nursing profession and reducing available nursing staff.2,5 Moral distress may also reduce nurses’ confidence and abilities to learn and lead to pessimism about, and reduced interests in, nursing. 6 Accordingly, efforts to reduce moral distress in nurses may lead to improved quality of care. 7

Complicating approaches to addressing moral distress among nurses, the causes, frequency, and severity of moral distress may vary according to work locations, services provided, and care settings. 8 Additional factors linked to moral distress in nursing may include feeling the need to provide unnecessary care, having limited physical resources, overwork, observation of patient suffering,6,9 beliefs regarding provision of sub-standard care and treatment due to lack of specialist staff and working with poorly qualified people, 10 inadequate knowledge, fear of talking, 11 improper inter-professional communication, 12 caring for critically ill patients, high mortality rates, unfavorable expectations of patients’ families and an inordinate sense of responsibility for patients’ lives and deaths, receipt of inadequate support, 13 and professional attitudes and psychological characteristics. 14

Nurses across hospital wards, such as internal medicine, surgery, psychiatry, 9 oncology,9,15 emergency,16–18 and specialty wards,7,19 may experience moral distress. It has been proposed that nurses in different wards may experience different levels of incidence and severity of moral distress, but evidence are not consistent regarding which kinds of nurses’ experience are more or less linked to moral distress.20–22

Several previous reviews have been published on nurses’ moral distress with different designs including systematic reviews,23–29 integrative and rapid scoping reviews.3,30,31 However, there are limitations regarding these reviews. Of the available reviews, only three summarized the findings using meta-analyses.23–25 Also, participants in these studies were limited to one group of nurses including undergraduate nursing students, 26 oncology, 23 intensive care unit (ICU), 25 neonatal and pediatric ICU, 28 and Iranian nurses. 24 Therefore, none of previous systematic reviews gathered and compared evidence regarding moral distress across nursing wards. Some previous studies have additional limitations regarding lack of methodological quality assessment and comprehensive literature review.3,26,27 Based on the limitations of previous studies, a comprehensive search strategy through main academic databases and gray literature was designed to gather evidence with no limitations regarding nurses’ characteristics including work locations. The other novel aspect of the current systematic review involves the possibility to consider moral distress among nurses before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, given that work expectations and conditions may vary across countries with differing levels of development, this was considered in the present study. With the consideration of the literature gaps mentioned above, the current systematic review aimed to estimate moral distress among nurses with subgroup analysis considering characteristics including work location, COVID-19 pandemic timing and development status of the local jurisdiction.

Methods

Design and registration

The present study was a systematic review and meta-analysis conducted between October 2021 and February 2022. The protocol of this project was registered in the PROSPERO database affiliated with the International prospective registry of systematic reviews under decree code of CRD42021267773. 32

Search strategy

Five academic databases including Scopus, PubMed, ProQuest, ISI Web of Knowledge, and PsycInfo were searched systematically from inception to end of February 2022. To construct the systematic search question and search query, the PECO-S framework was used. Based on PECO, queries were comprised of four aspects: Population (P), Exposure (E), Comparison (C), Outcome (O), and Study design (S). 33 PECO-S framework in current systematic review was explained as: Nurses for population; working in clinical conditions including hospitals, elderly care setting, health care systems for exposure; comparison was not defined based on the main objective of current systematic review; moral distress mean score was set as outcome; and observational studies including cross sectional or baseline of longitudinal studies were selected study design. Two main components of P (nurse) and O (moral distress) was selected as main search terms. The search terms were extracted from PubMed Medical Subject Heading terms. The main search terms were moral distress and nurses. The search query was developed using the Boolean operators of AND/OR/NOT. The core search syntax was (Nurse OR (Personnel AND Nursing) OR “Nursing Personnel” OR “Registered Nurses” OR (Nurse AND Registered) OR (Nurses AND Registered) OR “Registered Nurse” OR nurse*) AND (“moral distress” OR (moral AND distress) OR “moral stress” OR “moral responsibility” OR “moral dilemma” OR conscience OR “ethical confrontation”). Then search syntax was customized based on the advanced search attributes of each database. Additionally, reference lists of included studies, Open Grey and NYAM were searched as gray literature to increase the comprehensiveness of search.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria were considered as below

Type of participants

Nurses working in any position and or any clinical setting should be assessed as target population. If nurses were assessed as subgroup of studies, that was included when the findings related to nurses were reported separately.

Type of outcomes measure

Moral distress mean scores were considered as the main outcome of current systematic review. So, moral distress should be assessed by valid and reliable scales to be included. Also data on moral distress should be reported as mean and standard deviation (SD).

Type of studies

All English, peer-reviewed papers with observational studies including Cross sectional studies or baseline of longitudinal studies published up to February 2022 were included.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

Estimation of moral distress among nurses.

Secondary outcomes

1. Comparison of moral distress before and after the COVID-19 pandemic;

2. Influencing variables (e.g., age and working ward) in estimation of moral distress among nurses;

3. Assessment of heterogeneity and possible sources

Study screening & selection

First, title and abstract of all retrieved papers were screened based on the inclusion criteria. The full texts of potentially relevant studies were further reviewed based on the aforementioned criteria. In this process, relevant studies were selected.

Quality assessment

The methodological quality (or risk of bias) of included studies was assessed using the Newcastle Ottawa checklist that was developed for appraisal methodological quality of observational studies. Selection, comparability, and outcome were assessed with 7 items. The maximum acquirable score is 9 and scores less than 5 points were classified as being low methodological quality (or having a high risk of bias). 34 Methodological quality was not considered as an eligibility criterion, but rather its’ impact on pooled effect sizes was examined in subgroup analyses.

Data extraction

A pre-designed excel sheet form was prepared to extract data including first author’s name, collection date, study design, country, number of participants, percent of female participants, mean age, scale used to assess moral distress, and numerical results regarding the means and standard deviations of moral distress scores. In studies in which nurses were a subgroup of participants, numerical findings related to nurses were extracted.

Three steps of study selection, quality assessment, and data extraction were done independently by two reviewers. In the process, disagreements were resolved through discussion involving the two reviewers.

Data synthesis

Data from included studies were pooled using quantitative approaches and STATA software version 14. Meta-analyses using random effect models were conducted to include within- and between-study variances. 35 Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the Q Cochrane test. The I2 index was used to estimate the degree of heterogeneity. 36 It was interpreted as mild (I2 < 25%), moderate (25 < I2 < 50%, severe (50 < I2 < 75%), and highly severe (I2 > 75%). 36

The selected key measure was mean score of moral distress total score. It was analyzed using Metan module of Stata pooling mean and SDs of included studies. The pooled estimate of this key measure with 95% confidence interval was reported. In the included studies, different versions of the Moral Distress scale with different number of questions and different ranges of acquirable scores were used. But in all studies, higher scores present more moral distress. To have comparable and analyzable scores for the purpose of meta-analysis, the scores obtained from each questionnaire were converted to a scale of 0–10. For this purpose, the average score obtained in the study was multiplied by 10 and then divided by the highest score obtained in that scale. For example, when a mean score of 35 was reported in the range of 0–336, then it was corrected as (35 * 10)/336 = 1.04. Then, 1.04 was used as the corrected mean in a scale ranging from 0–10 and entered in the meta-analysis.

Subgroup analysis (analyzed using Metan module based on subgroups) and meta-regression (analyzed using Metareg module) was done to identify possible sources of heterogeneity and influencing variables on moral distress. Funnel plots (analyzed using Metafunnel module) and Begg’s Tests (analyzed using Metabias module) were used to assess publication bias. 37 Studies with smaller sample sizes and/or negative or less significant results are often more likely to be less successful to be published. 38 This may lead to publication bias in a meta-analysis (presented as asymmetric funnel plot and significant Begg’s test). 39 Presence of publication bias can mislead the conclusions. So, identified publication bias should be corrected using the available methods. 40 Fill and trim method is one of the best methods to correct publication bias; in which probable related unpublished papers are retrieved using various statistical methods. 41 In the present study, probable publication bias was corrected using fill and trim method.

The Jackknife method was used for sensitivity analysis (analyzed using Metaninf module). 42 It is also called “leave one out” method. First, the pooled effect size is estimated from the whole sample. Then, in an iterative process, the pooled effect size is computed when each study is, in turn, dropped from the sample. 43

Results

Study screening & selection process

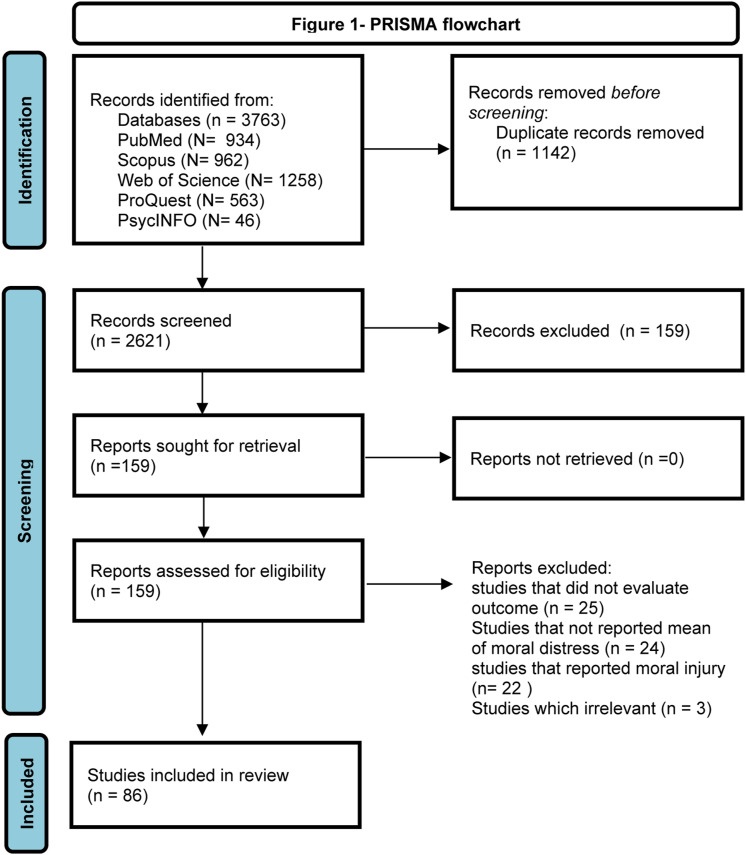

The initial search retrieved 3763 studies: PubMed (N = 934); Scopus (N = 962); Web of Science (N = 1258); ProQuest (N =563), PsycINFO (N = 46). After removing duplicated papers, 2621 papers were screened based on title and abstract and in next stage 159 full text were assessed. Finally, 86 studies met the eligibility criteria and were pooled in the meta-analysis. The search and selection process based on the PRISMA flowchart is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart.

Study description

86 papers with 19,537 participants from 21 countries (Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Finland, Germany, Greece, Iran, Israel, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Norway, Romania, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Sweden, Thailand, Turkey, UK, and USA) were included. Fifteen papers gathered data during the early part of the COVID-19 pandemic. The smallest sample size was 21 and the largest was 1226. The individual countries with the highest number of eligible studies were Iran (N = 27) and USA (N = 22). Almost 81% of participants were female. The mean participant age and working experience were 36.28 and 11.52 years, respectively. Most studies were conducted in developed countries (N = 49) with a cross-sectional design (N = 81). Nine studies were conducted after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Table 1 provides summary characteristics of included studies.

Table 1.

Summary of characteristics of included studies.

| Author | Year | COVID-19 pandemic | Country | Developing status | Design | Working ward | Sample size | Female % | Measure | NOS score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ventovaara 55 | 2021 | No | Finland | Developed | Cross sectional | Pediatric oncology | 93 | 95 | Moral distress scale–revised | 6 |

| Karakachian 56 | 2021 | No | USA | Developed | Cross sectional | Pediatric | 146 | 91.8 | Moral distress scale neonatal–pediatrics | 8 |

| Janatolmakan 6 | 2021 | No | Iran | Developing | Cross sectional | No specific ward | 86 | 40 | Moral distress scale–revised | 6 |

| Babamohamadi 8 | 2021 | No | Iran | Developing | Cross sectional | Emergency | 203 | 46.3 | Moral distress scale–revised | 8 |

| Lake 57 | 2021 | Yes | USA | Developed | Cross sectional | No specific ward | 306 | NR | COVID-19 moral distress scale | 5 |

| Malliarou 58 | 2021 | Yes | Greece | Developed | Cross sectional | ICU | 257 | 82.8 | Moral distress for healthcare professionals | 6 |

| Donkers 59 | 2021 | Yes | Netherlands | Developed | Cross sectional | ICU | 345 | 77.2 | Moral distress for healthcare professionals | 5 |

| Prompahakul 60 | 2021 | Yes | Thailand | Developing | Mixed method | No specific ward | 462 | 97 | Moral distress for healthcare professionals | 5 |

| Petrisor 61 | 2021 | No | Romania | Developing | Cross sectional | ICU | 79 | 89.87 | Moral distress for healthcare professionals | 5 |

| Bleicher 62 | 2021 | No | USA | Developed | Mixed method | ICU | 21 | 90.5 | Moral distress for healthcare professionals | 4 |

| Guttmann 63 | 2021 | No | USA | Developed | Prospective | ICU | 178 | 97 | Moral distress thermometer | 6 |

| Miljeteig 64 | 2021 | Yes | Norway | Developed | Cross sectional | No specific ward | 525 | NR | Moral distress thermometer | 6 |

| Tajalli 65 | 2021 | Yes | Iran | Developing | Cross sectional | NICU | 209 | NR | Moral distress scale–revised | 7 |

| Isık 66 | 2021 | No | Turkey | Developing | Cross sectional | ICU | 128 | NR | Moral distress scale–revised | 6 |

| Goyaghaj 67 | 2021 | No | Iran | Developing | Cross sectional | Patients with spinal cord injury | 160 | 61.9 | Moral distress scale–revised | 6 |

| Fujii 68 | 2021 | No | Japan | Developed | Cross sectional | No specific ward | 242 | 88 | Moral distress for healthcare professionals | 6 |

| Nemati 69 | 2021 | Yes | Iran | Developing | Cross sectional | No specific ward | 296 | 76.07 | Moral distress scale | 7 |

| Khorashadizadeh 70 | 2021 | No | Iran | Developing | Cross sectional | No specific ward | 454 | 80.8 | Moral distress scale | 5 |

| Meese 71 | 2021 | Yes | USA | Developed | Cross sectional | No specific ward | 136 | 78.26 | Single-item moral distress frequency | 7 |

| Kok 72 | 2020 | Yes | Netherlands | Developed | Cross sectional | ICU | 194 | 80.9 | Moral distress scale–revised | 4 |

| Safarpour 73 | 2020 | No | Iran | Developing | Cross sectional | No specific ward | 217 | 90.78 | Moral distress scale–revised | 6 |

| Clark 2 | 2020 | No | USA | Developed | Cross sectional | Emergency | 175 | 87.4 | Moral distress for healthcare professionals | 6 |

| Barr 74 | 2020 | No | Australia | Developed | Cross sectional | NICU | 136 | 99 | Moral distress scale neonatal–pediatrics | 6 |

| Rezaei Fard 75 | 2020 | No | Iran | Developing | Cross sectional | No specific ward | 150 | 56 | Moral distress scale | 7 |

| Marturano 21 | 2020 | No | USA | Developed | Cross sectional | Oncology | 93 | 93 | Moral distress scale–revised | 6 |

| Sedaghati 76 | 2020 | No | Iran | Developing | Cross sectional | Nursing home | 227 | 78 | Moral distress scale–revised | 7 |

| Sandeberg 77 | 2020 | No | Sweden | Developed | Cross sectional | No specific ward | 223 | NR | Moral distress scale–revised | 5 |

| Emmamally 78 | 2020 | No | South Africa | Developing | Cross sectional | CCU | 74 | NR | Moral distress scale–revised | 5 |

| Ramos 79 | 2019 | No | Brazil | Developing | Cross sectional | No specific ward | 1226 | NR | Moral distress scale–revised | 5 |

| Jones 80 | 2019 | No | UK | Developed | Cross sectional | Pediatric ICU | 1194 | 95 | Moral distress scale–revised | 6 |

| Yeganeh 81 | 2019 | No | Iran | Developing | Cross sectional | ICU | 180 | 93.89 | Moral distress scale | 5 |

| Sannino 82 | 2019 | No | Italy | Developed | Cross sectional | Pediatric ICU | 136 | 89 | Moral distress scale neonatal–pediatrics | 4 |

| Wachholz 83 | 2019 | No | Brazil | Developing | Cross sectional | No specific ward | 141 | NR | Moral distress scale–revised | 7 |

| Pergert 84 | 2019 | No | Sweden | Developed | Cross sectional | No specific ward | 223 | NR | Moral distress scale–revised | 7 |

| Bayat 85 | 2019 | No | Iran | Developing | Cross sectional | No specific ward | 300 | 73.33 | Moral distress scale–revised | 6 |

| Fruet 86 | 2019 | No | Brazil | Developing | Cross sectional | Oncology | 46 | NR | Moral distress scale | 6 |

| Zabetian 87 | 2019 | No | Iran | Developing | Cross sectional | No specific ward | 145 | 90 | Moral distress scale | 5 |

| Harorani 88 | 2019 | No | Iran | Developing | Cross sectional | CCU | 300 | 70 | Moral distress scale | 5 |

| Colville 89 | 2019 | No | UK | Developed | Cross sectional | ICU | 145 | 77 | Moral distress scale–revised | 6 |

| Abdolmaleki 90 | 2018 | No | Iran | Developing | Cross sectional | Emergency | 173 | NR | Moral distress scale–revised | 8 |

| Mehlis 15 | 2018 | No | Germany | Developed | Cross sectional | Oncology | 50 | 60 | Moral distress thermometer | 5 |

| Altaker 91 | 2018 | No | USA | Developed | Cross sectional | ICU | 238 | 90 | Moral distress scale–revised | 6 |

| Asayesh 92 | 2018 | No | Iran | Developing | Cross sectional | ICU | 117 | 66.7 | Moral distress scale | 7 |

| Robaee 93 | 2018 | No | Iran | Developing | Cross sectional | No specific ward | 120 | 90 | Nurses’ MDS by Atashzadeh-Shoorideh | 6 |

| Alborzi 94 | 2018 | No | Iran | Developing | Cross sectional | ICU | 100 | 79 | Moral distress scale | 6 |

| Lamiani 95 | 2018 | No | Italy | Developed | Cross sectional | ICU | 77 | 53 | Moral distress scale–revised | 5 |

| Ajoudani 96 | 2018 | No | Iran | Developing | Cross sectional | No specific ward | 278 | 85.82 | Moral distress scale–revised | 8 |

| Neumann 97 | 2018 | No | USA | Developed | Cross sectional | Transplantation | 763 | 96 | Moral distress scale–revised | 7 |

| Noghanchi Saleh 98 | 2018 | No | Iran | Developing | Cross sectional | NICU | 172 | NR | Moral distress scale | 5 |

| Sirilla 99 | 2017 | No | USA | Developed | Cross sectional | No specific ward | 316 | NR | Moral distress scale–revised | 6 |

| Christodoulou-Fella 100 | 2017 | No | Europe and the USA | Developed | Cross sectional | Psychiatric | 206 | 56.3 | Moral distress scale for mental health services | 8 |

| Haghighinezhad 13 | 2017 | No | Iran | Developing | Cross sectional | ICU | 284 | 33.05 | ICU nurses’ moral distress scale | 6 |

| Xiaoyan 101 | 2016 | No | China | Developed | Cross sectional | No specific ward | 465 | 92.25 | Moral distress scale–revised | 8 |

| Lusignani 102 | 2016 | No | Italy | Developed | Cross sectional | No specific ward | 283 | 80.21 | Moral distress scale–revised | 6 |

| Dyo 9 | 2016 | No | USA | Developed | Cross sectional | No specific ward | 279 | 92.83 | Moral distress scale | 6 |

| Ameri 103 | 2016 | No | Iran | Developing | Cross sectional | Oncology | 148 | 88.51 | Moral distress scale–revised | 5 |

| Ando 104 | 2016 | No | Japan | Developed | Cross sectional | Psychiatric | 130 | 78.5 | Moral distress scale for psychiatric nurses | 5 |

| Soleimani 105 | 2016 | No | Iran | Developing | Cross sectional | No specific ward | 193 | 81.3 | Moral distress scale–revised | 8 |

| Zavotsky 106 | 2016 | No | USA | Developed | Cross sectional | Emergency | 198 | 85.4 | Moral distress scale–revised | 7 |

| Darabzadeh 107 | 2016 | No | Iran | Developing | Cross sectional | Surgical | 123 | 80.5 | Moral distress scale | 5 |

| Sauerland 108 | 2015 | No | USA | Developed | Cross sectional | Pediatric ICU | 53 | 88.7 | Moral distress scale neonatal–pediatrics | 5 |

| Karagozoglu 109 | 2015 | No | Turkey | Developing | Cross sectional | ICU | 200 | 73.5 | Moral distress scale–revised | 5 |

| Trotochaud 110 | 2015 | No | USA | Developed | Cross sectional | Pediatric | 577 | NR | Moral distress scale–revised | 5 |

| Borhani 111 | 2015 | No | Iran | Developing | Cross sectional | No specific ward | 300 | 87 | Moral distress scale | 5 |

| Browning 112 | 2015 | No | USA | Developed | Cross sectional | No specific ward | 277 | NR | Moral distress scale | 6 |

| de Boer 113 | 2015 | No | Netherlands | Developed | Prospective | NICU | 87 | 98.9 | Moral distress scale–revised | 5 |

| Ganz 114 | 2014 | No | Israel | Developed | Cross sectional | Nurse middle manager | 133 | 88.72 | Ethical dilemmas in nursing | 6 |

| Sauerland 115 | 2014 | No | USA | Developed | Cross sectional | CCU | 225 | 80 | Moral distress scale | 5 |

| Borhani 116 | 2014 | No | Iran | Developing | Cross sectional | No specific ward | 220 | NR | Moral distress scale | 5 |

| Hamaideh 117 | 2014 | No | Saudi Arabia | Developing | Cross sectional | Psychiatric | 130 | 56.9 | Moral distress scale for psychiatric nurses | 6 |

| Karanikola 118 | 2014 | No | Italy | Developed | Cross sectional | ICU | 566 | 70.8 | Moral distress scale | 7 |

| Shoorideh 119 | 2014 | No | Iran | Developing | Cross sectional | ICU | 159 | 72.3 | ICU nurses’ moral distress scale | 5 |

| Wilson 120 | 2013 | No | USA | Developed | Cross sectional | ICU | 48 | 94 | Moral distress scale | 6 |

| Ganz 121 | 2013 | No | Israel | Developed | Cross sectional | ICU | 291 | 75.3 | Moral distress scale | 7 |

| Fernandez-Parsons 122 | 2013 | No | USA | Developed | Cross sectional | Emergency | 51 | NR | Moral distress scale–revised | 5 |

| Ganz 123 | 2012 | No | Israel | Developed | Cross sectional | Surgical | 119 | 93.3 | Ethical dilemmas in nursing | 7 |

| Lazzarin 124 | 2012 | No | Italy | Developed | Cross sectional | Oncology and hematology | 235 | 95 | Moral distress scale neonatal–pediatrics | 4 |

| Papathanassoglou 125 | 2012 | No | European critical care conference delegates | Developed | Cross sectional | ICU | 255 | NR | Moral distress scale | 7 |

| Villers_ Non-CCU nurses 126 | 2012 | No | USA | Developed | Cross sectional | No specific ward | 28 | 96 | Moral distress scale | 6 |

| Villers_CCU nurses 126 | 2012 | No | USA | Developed | Cross sectional | CCU | 65 | 91 | Moral distress scale | 6 |

| Joolaee 127 | 2012 | No | Iran | Developing | Cross sectional | No specific ward | 210 | 90 | Moral distress scale | 5 |

| McAndrew 128 | 2011 | No | USA | Developed | Cross sectional | ICU | 78 | NR | Moral distress scale | 7 |

| Ohnishi 129 | 2010 | No | Japan | Developed | Cross sectional | Psychiatric | 264 | 73.1 | Moral distress scale for psychiatric nurses | 6 |

| Pauly 130 | 2009 | No | Canada | Developed | Cross sectional | No specific ward | 374 | 94 | Moral distress scale–revised | 6 |

| Elpern 131 | 2005 | No | USA | Developed | Cross sectional | ICU | 28 | 77 | Moral distress scale | 5 |

ICU: Intensive care unit, NICU: Neonatal intensive care unit, PICU: Pediatric intensive care unit, CCU: Cardiac care unit; NOS score: Methodological quality score based on NOS checklist.

Methodological quality assessment

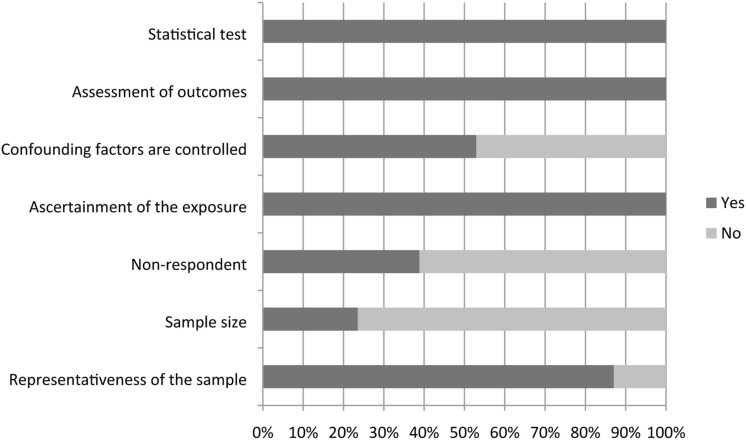

Considering Newcastle Ottawa scores (NOS) > 5 as high quality, 65.88% of included studies (56 papers) were categorized as having low risk of bias. Methodological problems were related to: (i) no explanations regarding sample size estimation; (ii) no explanations regarding non-respondents and how non-response was managed; and (iii) controlling for potentially confounding factors. Figure 2 provides results of methodological quality assessments based on NOS checklist items.

Figure 2.

Results of the methodological quality assessment based on the NOS checklist.

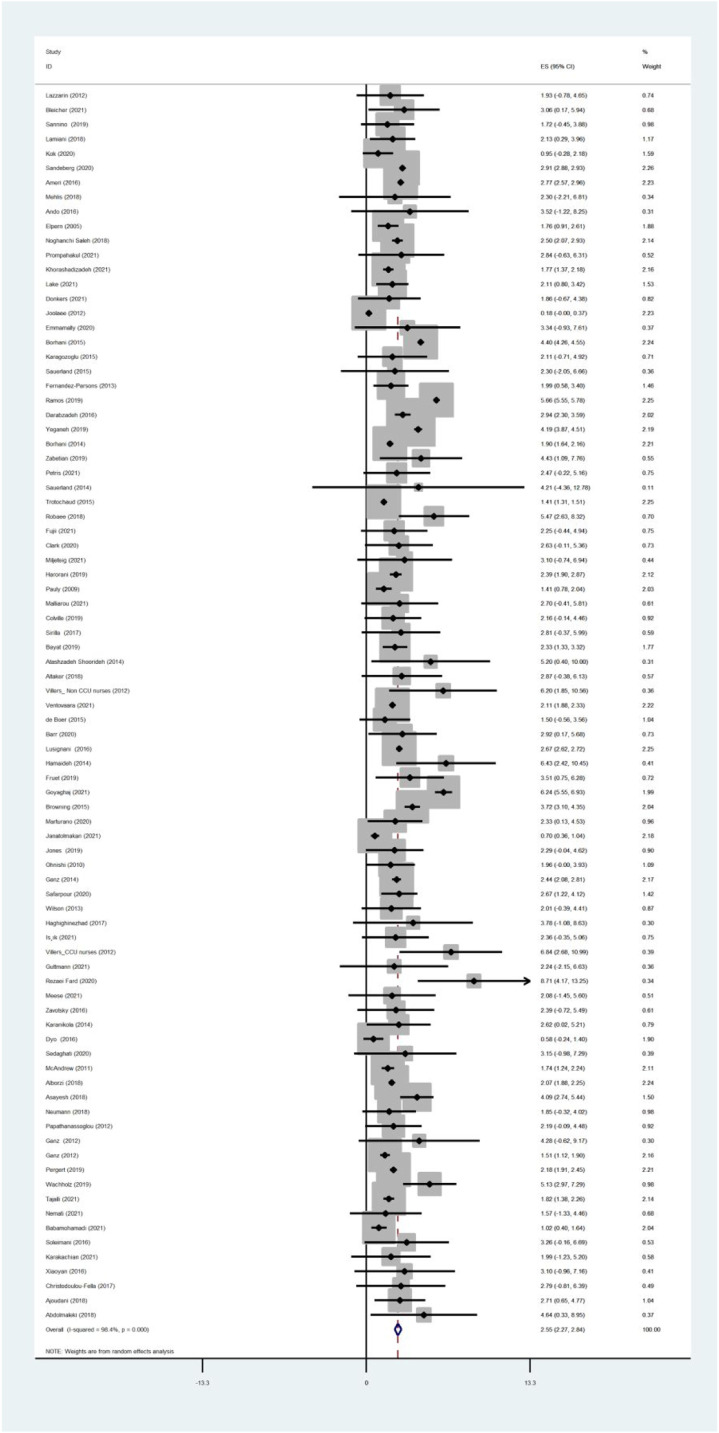

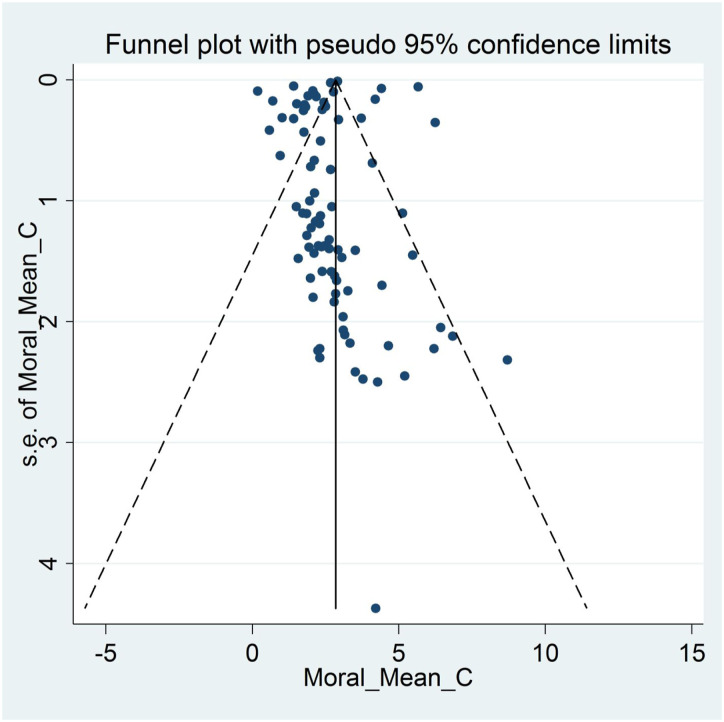

Estimation of pooled moral distress mean score

The pooled estimated mean score of moral distress was 2.55 in a range of 0–10 [95% Confidence Interval: 2.27–2.84, I2: 98.4%, Tau2:0.94]. Figure 3 provides a forest plot regarding the pooled estimated mean score of moral distress. Begg’s tests (p < .001) and funnel plots (Figure 4) consider probabilities of publication bias. Meta trim was used to correct for probable publication bias. But on trim methodology, no studies were imputed and probability of publication bias was considered low. Also, sensitivity analysis suggested that the pooled effect size was not affected by any single study.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of estimated pooled mean scores of moral distress.

Figure 4.

Funnel plot assessing publication bias in estimated pooled mean scores of moral distress.

Subgroup/meta-regression results

The results of subgroup analysis (Table 2) and meta-regression (Table 3) showed that mean score of moral distress significantly decreased after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (1.80 vs 2.62). Nurses working in developing countries experienced higher levels of moral distress compared to their counterparts in developed countries (3.14 vs 2.14). Nurses in developed countries experienced less moral distress than their counterparts in developing countries by 0.76 point lower on a scale of 0–10, according to meta-regression analysis (p = .02). The variables of methodological quality and study design had no significant effect on the mean score of moral distress (p > .05). Nurses’ workplace location had no significant relationship with moral distress (p = .62). However, the lowest mean scores of moral distress were observed in pediatric and emergency ward nurses (1.41 and 1.60, respectively), and the highest scores were observed in critical care unit and psychiatric ward nurses (3.42 and 3.14, respectively). Also, the workplace ward had the greatest effect on heterogeneity. The lowest heterogeneity was observed in psychiatry and emergency wards (23.4% and 33%). Among the investigated variables, country’s development status and nurses’ workplace explained 5.59% and 3.16% of the variance in moral distress among nurses.

Table 2.

Results of subgroup analyses.

| Variable | No. of studies | ES (95% CI) | I2 (%) | Tau2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 pandemic | Prior | 76 | 2.62 (2.32; 2.92) | 98.5 | 0.4 |

| During | 9 | 1.80 (1.42; 2.18) | 0 | 0 | |

| Developmental status | Developed | 49 | 2.14 (1.88; 2.38) | 95.3 | 0.26 |

| Developing | 36 | 3.14 (2.39; 3.89) | 99.1 | 4.10 | |

| Design | Cross sectional | 83 | 2.57 (2.28; 2.85) | 98.4 | 0.97 |

| Prospective | 2 | 1.63 (−0.23; 3.50) | 0 | 0 | |

| Methodological quality | Low risk of bias | 56 | 2.47 (2.17; 2.77) | 87.9 | 0.05 |

| High risk of bias | 29 | 2.53 (1.91; 3.14) | 99.4 | 1.98 | |

| Working ward | Oncology | 6 | 2.45 (1.91; 2.99) | 74.8 | 0.16 |

| Pediatrics | 3 | 1.41 (1.31; 1.51) | 0 | 0 | |

| Emergency | 4 | 1.60 (0.62; 2.59) | 33.0 | 0.35 | |

| ICU (including NICU & PICU) | 29 | 2.31 (1.83; 2.79) | 84.8 | 0.82 | |

| CCU | 4 | 3.42 (1.37; 5.48) | 35.8 | 1.76 | |

| Psychiatric | 4 | 3.14 (1.27; 5.01) | 23.4 | 0.90 | |

| No specific wards | 35 | 2.80 (2.38; 3.22) | 99.1 | 0.96 | |

| Overall estimated prevalence | 85 | 2.55 (2.27; 2.84) | 98.4 | 0.94 | |

ICU: Intensive care unit, NICU: Neonatal intensive care unit, PICU: Pediatric intensive care unit, CCU: Cardiac care unit.

Table 3.

Results of meta-regression.

| Variable | Number of studies | Coeff | S.E. | p | I2 res. (%) | Adj. R2 (%) | Tau2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | 85 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.65 | 98.37 | −0.67 | 1.30 |

| Mean age | 47 | 0.005 | 0.03 | 0.88 | 97.41 | −2.10 | 1.57 |

| Mean working experience | 38 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.85 | 94.24 | −3.60 | 1.39 |

| Female percentage of participants | 66 | −0.002 | 0.01 | 0.91 | 96.37 | - 2.45 | 1.32 |

| Working ward | 85 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.18 | 98.35 | 3.16 | 1.83 |

| Methodological quality score | 85 | −0.06 | 0.17 | 0.75 | 98.28 | −0.57 | 1.31 |

| Development status (developed vs developing) | 85 | −0.76 | 0.32 | 0.02 | 98.26 | 5.59 | 1.22 |

| COVID-19 pandemic (during vs prior) | 85 | −0.74 | 0.56 | 0.19 | 98.38 | 0.76 | 1.28 |

| Measure assessing moral distress | 85 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.36 | 98.37 | −1.06 | 1.31 |

Coeff: Coefficient; S.E: Standard Error; I2 res: I2 residual; Adj. R2: Adjusted R2.

Discussion

Given the importance of moral distress among healthcare professionals (e.g., healthcare professionals may respond sub-optimally to certain patient requests or needs based on moral distress, and this result in poor health outcomes for patients),1–5 it is important to understand moral distress among healthcare professionals, especially nurses who often interact more frequently with patients in acute care settings than do other healthcare professional. The present systematic review and meta-analysis used rigorous methods (including a thorough search of five commonly used academic databases, the use of the NOS to evaluate and control for study quality in meta-analysis, 34 the application of subgroup analyses and meta-analyses to identify potential sources of heterogeneity, and several statistical methods to assess and correct fir possible publication bias37,44).

Data from 19,537 participants reported in 86 papers across 21 countries (Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Finland, Germany, Greece, Iran, Israel, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Norway, Romania, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Sweden, Thailand, Turkey, UK, and USA) were assessed, and the mean moral distress was 2.55 on a 0–10 scale. This indicates that in general the nurses did not have high levels of moral distress in their clinical practices. Moreover, such findings were found to be consistent across high-quality versus low-quality studies. The relatively low moral distress suggests that moral distress may not interfere too frequently with nurses provision of quality care. 7 However, subgroup analyses in the present systematic review and meta-analysis revealed that nurses working in developing countries had higher levels of moral distress than those working in developed countries. Moreover, nurses working in a critical care unit or a psychiatric ward appeared to have higher levels of moral distress than those working in other wards (especially those working in pediatric ward), although this finding was not statistically significant. Thus, identifying and addressing moral distress among nurses may be particularly relevant for those working in developing countries.

Nurses in the developing countries may encounter unique experiences including with respect to poor availabilities of health care equipment, training programs, and standardized care procedures when compared to those in the developed countries.45–48 For example, prior evidence shows that the healthcare infrastructure in developing countries may not be capable to of optimally supporting health information systems, mHealth, and artificial intelligence technologies.46–48 Therefore, as compared with nurses in developed countries, nurses working in a developing country may have more difficulties in providing immediate and state-of-the-art treatments to patients. Moral distress may thus occur when nurses in developing country experience limitations in providing high-quality care although this notion is currently speculative and requires direct examination. Moreover, healthcare budgets in developing countries are frequently low and focus on communicable diseases. 49 Therefore, nurses in developing countries may encounter shortages of resources in healthcare settings. Consequently, nurses in developing countries may be likely to suffer from moral distress than those in developed countries, and these possibilities warrant further examination.

Nurses working in a critical care unit or a psychiatric ward were found to have numerically high levels of moral distress. This may reflect difficulties and complexities of caring for patients with critical needs or psychiatric conditions.50,51 Caring for patients with critical needs is often associated with burdens of uncertainty and difficulties in treatment-related decision-making. 52 Speculatively, such difficulties in decision-making may increase moral distress among nurses. For nurses providing psychiatric care, they often experience stigma (e.g., affiliated stigma leading to self-stigma),53,54 and subsequently, nurses providing psychiatric care may be more likely to escape from feelings of stigma via providing less optimal care to patients, further generating moral distress. These currently speculative possibilities warrant direct examination.

Finally, the observation that moral distress among nurses have not increased during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic is heartening and suggests that nurses may have specific resiliency to mitigate against moral distress during the COVID-19-related circumstances. Identification of resiliency factors is important as they may help guide interventions and prevent moral distress and related factors like burnout.

Limitations

There are limitations in the present systematic review and meta-analysis. First, the population was restricted to nurses. Given that nurses and other healthcare professionals may encounter different moral distress in clinical practice, the findings of the present study may not generalize to other healthcare professionals. However, the focus on nurses is important as they often interact frequently with patients in healthcare settings. Also, it should be considered that the general term of nurse (who passed academic courses and graduated as nurse) and its’ MeSH terms were used to develop search syntax. In many countries, different levels of nurses exists—Registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, and auxiliaries and similar. Most of these terms used for nurses and nursing personnel are retrievable by the comprehensive search syntax developed for current study. But it should be noted that if terms other that nurse were used, those studies might not be retrieved. Second, only studies published in English were included in the present systematic review and meta-analysis. Therefore, some data published in other languages may have been omitted. Third, most included papers utilized a cross sectional study design, therefore, limiting insight into potential causal factors relating to moral distress. Future studies with longitudinal designs are warranted.

Clinical implication

The findings of the present systematic review and meta-analysis suggest the following implications for nursing management. First, moral distress among nurses was found to be higher in developing countries than in developed countries. Therefore, nurse managers, administrators, and other stakeholders should attend to moral distress among nurses, particularly those working in developing countries. Regular workshops helping nurses to overcome moral distress may be important to target moral distress among nurses. Second, nurses working in some specific wards (e.g., critical care unit and psychiatric wards) may experience high levels of moral distress. Therefore, evaluating and addressing moral distress in these settings may be particularly important. In all cases, identifying risk and resilience factors related to moral distress among nurses appears important. Such information may help with developing and targeting appropriate interventions to reduce moral distress among nurses.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present systematic review and meta-analysis showed a low the pooled estimated score of moral distress. Although the score of moral distress was not high, nurses working in developing countries encountered higher levels of moral distress than those working in developed countries. Nurses in developing countries face many challenges that can affect their moral distress. Therefore, it is necessary that future studies focus on creating a supportive environment in hospitals and medical centers for nurses to reduce moral distress and improve healthcare.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The authors have no conflicts of interest with the content of this manuscript. Dr. Potenza discloses that he has consulted for and advised Game Day Data, Addiction Policy Forum, AXA, Idorsia and Opiant Therapeutics; been involved in a patent application with Yale University and Novartis; received research support from the Mohegan Sun Casino and the Connecticut Council on Problem Gambling; consulted for or advised legal and gambling entities on issues related to impulse control and addictive behaviors; performed grant reviews; edited journals/journal sections; given academic lectures in grand rounds, CME events and other clinical/scientific venues; and generated books or chapters for publishers of mental health texts. The other authors report no disclosures.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Amir H Pakpour https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8798-5345

References

- 1.Hussain FA. Psychological challenges for nurses working in palliative care and recommendations for self-care. Br J Nurs 2021; 30: 484–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark P, Crawford TN, Hulse B, et al. Resilience, moral distress, and workplace engagement in emergency department nurses. West J Nurs Res 2021; 43: 442–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McAndrew NS, Leske J, Schroeter K. Moral distress in critical care nursing: the state of the science. Nurs Ethics 2018; 25: 552–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis AJ, Fowler M, Fantus S, et al. Healthcare professional narratives on moral distress: disciplinary perspectives. In: Moral Distress in the health professions. Switzerland: Springer, 2018, pp. 21–57. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xiaoyan W, Yufang Z, Lifeng C, et al. Moral distress and its influencing factors: a cross-sectional study in China. Nurs Ethics 2018; 25: 470–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janatolmakan M, Dabiry A, Rezaeian S. Frequency, severity, rate, and causes of moral distress among nursing students: a cross-sectional study. Educ Res Int 2021; 2021: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moshtagh M, Mohsenpour M. Moral distress situations in nursing care. Clin Ethics 2019; 14: 141–145. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Babamohamadi H, Katrimi SB, Paknazar F. Moral distress and its contributing factors among emergency department nurses: A cross-sectional study in Iran. Int Emerg Nurs 2021; 56: 100982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dyo M, Kalowes P, Devries J. Moral distress and intention to leave: a comparison of adult and paediatric nurses by hospital setting. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2016; 36: 42–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohamadi N, Fakoor F, Haghani H, et al. The association of moral distress and demographic characteristics in the nurses of critical care units in Tehran, Iran. Iran J Nurs 2019; 32: 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krautscheid L, DeMeester DA, Orton V, et al. Moral distress and associated factors among baccalaureate nursing students: a multisite descriptive study. Nurs Education Perspect 2017; 38: 313–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jafari M, Hosseini M, Maddah SSB, et al. Factors behind moral distress among Iranian emergency medical services staff: A qualitative study into their experiences. Nurs Midwifery Stud 2019; 8: 195–202. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haghighinezhad G, Atashzadeh-Shoorideh F, Ashktorab T, et al. Relationship between perceived organizational justice and moral distress in intensive care unit nurses. Nurs Ethics 2019; 26: 460–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lamiani G, Borghi L, Argentero P. When healthcare professionals cannot do the right thing: A systematic review of moral distress and its correlates. J Health Psychology 2017; 22: 51–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehlis K, Bierwirth E, Laryionava K, et al. High prevalence of moral distress reported by oncologists and oncology nurses in end-of-life decision making. Psycho-Oncol 2018; 27: 2733–2739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hou Y, Timmins F, Zhou Q, et al. A cross-sectional exploration of emergency department nurses’ moral distress, ethical climate and nursing practice environment. Int Emerg Nurs 2021; 55: 100972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arnold TC. Moral distress in emergency and critical care nurses: A metaethnography. Nurs Ethics 2020; 27: 1681–1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moskop JC, Geiderman JM, Marshall KD, et al. Another look at the persistent moral problem of emergency department crowding. Ann Emergency Medicine 2019; 74: 357–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borhani F, Abbaszadeh A, Mohamadi E, et al. Moral sensitivity and moral distress in Iranian critical care nurses. Nurs Ethics 2017; 24: 474–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bayanzay K, Amoozgar B, Kaushal V, et al. Impact of profession and wards on moral distress in a community hospital. Nurs Ethics 2021; 29: 356–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marturano ET, Hermann RM, Giordano NA, et al. Moral distress: identification among inpatient oncology nurses in an academic health system. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2020; 24: 500–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delfrate F, Ferrara P, Spotti D, et al. Moral Distress (MD) and burnout in mental health nurses: a multicenter survey. La Medicina Del Lavoro 2018; 109: 97–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eche IJ, Phillips CS, Alcindor N, et al. A systematic review and meta-analytic evaluation of moral distress in oncology nursing. Can Nurs 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.YektaKooshali MH, Esmaeilpour-Bandboni M, Andacheh M. Intensity and frequency of moral distress among Iranian nurses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Iranian J Psychiatry Behav Sci 2018; 12: e10606. [Google Scholar]

- 25.AlQahtani RM, Al Saadon A, Alarifi MI, et al. Moral Distress among health care workers in the intensive care unit; a systematic review and meta-analysis, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sasso L, Bagnasco A, Bianchi M, et al. Moral distress in undergraduate nursing students: a systematic review. Nurs Ethics 2016; 23: 523–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huffman DM, Rittenmeyer L. How professional nurses working in hospital environments experience moral distress: a systematic review. Crit Care Nurs Clin 2012; 24: 91–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prentice T, Janvier A, Gillam L, et al. Moral distress within neonatal and paediatric intensive care units: a systematic review. Arch Disease Childhood 2016; 101: 701–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rittenmeyer L, Huffman D. How professional nurses working in hospital environments experience moral distress: a systematic review. JBI Evid Synth 2009; 7: 1234–1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sriharan A, West KJ, Almost J, et al. COVID-19-related occupational burnout and moral distress among nurses: a rapid scoping review. Nurs Leadership (Toronto, Ont) 2021; 34: 7–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewis SL. Emotional intelligence in neonatal intensive care unit nurses: decreasing moral distress in end-of-life care and laying a foundation for improved outcomes: an integrative review. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 2019; 21: 250–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soodmand M, Hosseini Z, Alimoradi Z. Estimation of moral Distress and associated factors among emergency nurses; a protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. PROSPERO database 2021; CRD42021267773. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=267773 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morgan RL, Whaley P, Thayer KA, et al. Identifying the PECO: a framework for formulating good questions to explore the association of environmental and other exposures with health outcomes. Environ International 2018; 121: 1027–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luchini C, Stubbs B, Solmi M, et al. Assessing the quality of studies in meta-analyses: advantages and limitations of the Newcastle Ottawa Scale. World J Meta-anal 2017; 5: 80–84. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hox JJ, Leeuw EDd. Multilevel models for meta-analysis, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huedo-Medina TB, Sánchez-Meca J, Marín-Martínez F, et al. Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I2 index? Psychol Methods 2006; 11: 193–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rothstein HR, Sutton AJ, Borenstein M. Publication bias in meta-analysis. In Publication bias in meta-analysis: Prevention, assessment and adjustments, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nissen SB, Magidson T, Gross K, et al. Publication bias and the canonization of false facts. Elife 2016; 5: e21451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shi L, Lin L. The trim-and-fill method for publication bias: practical guidelines and recommendations based on a large database of meta-analyses. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019; 98: e15987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sterne JA, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JP, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. Bmj 2011; 343: d4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sutton AJ, Duval SJ, Tweedie R, et al. Empirical assessment of effect of publication bias on meta-analyses. Bmj 2000; 320: 1574–1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hedges LV, Olkin I. Statistical methods for meta-analysis. USA: Academic Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salkind N. Encyclopedia of research design, USA: Sage Publications, Inc., 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot–based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 2000; 56: 455–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Misra A, Gopalan H, Jayawardena R, et al. Diabetes in developing countries. J Diabetes 2019; 11: 522–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bawack RE, Kamdjoug JRK. Adequacy of UTAUT in clinician adoption of health information systems in developing countries: the case of Cameroon. Int Journal Medical Informatics 2018; 109: 15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guo J, Li B. The application of medical artificial intelligence technology in rural areas of developing countries. Health Equity 2018; 2: 174–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kruse C, Betancourt J, Ortiz S, et al. Barriers to the use of mobile health in improving health outcomes in developing countries: systematic review. J Medical Internet Research 2019; 21: e13263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pastakia SD, Pekny CR, Manyara SM, et al. Diabetes in sub-Saharan Africa–from policy to practice to progress: targeting the existing gaps for future care for diabetes. Diabetes Metabolic Syndrome Obesity: Targets Therapy 2017; 10: 247–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bojdani E, Rajagopalan A, Chen A, et al. COVID-19 pandemic: impact on psychiatric care in the United States. Psychiatry Research 2020; 289: 113069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.González-Gil Np. demands regarding COVID-19 care delivery in critical care units and hospital emergency services. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Pattison N, Mclellan J, Roskelly L, et al. Managing clinical uncertainty: an ethnographic study of the impact of critical care outreach on end-of-life transitions in ward-based critically ill patients with a life-limiting illness. J Clin Nurs 2018; 27: 3900–3912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Joyce O, Blessing U. Affiliate stigma and compassion satisfaction amongst mental health service providers at a regional psychiatric hospital in Nigeria. J of Behav Therapy and Mental Health 2019; 2(1): 30–39. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Compton C. Exploring associative stigma among mental health professionals working within the local mental health services. Master’s dissertation. Malta: University of Malta, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ventovaara P, Ma S, Räsänen J, et al. Ethical climate and moral distress in paediatric oncology nursing. Nurs Ethics 2021; 28: 1061–1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Karakachian A, Colbert A, Hupp D, et al. Caring for victims of child maltreatment: pediatric nurses’ moral distress and burnout. Nurs Ethics 2021; 28: 687–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lake ET, Narva AM, Holland S, et al. Hospital nurses’ moral distress and mental health during COVID-19. J Adv Nurs 2021; 78: 799–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Malliarou M, Nikolentzos A, Papadopoulos D, et al. ICU nurse’s moral distress as an occupational hazard threatening professional quality of life in the time of pandemic COVID 19. Materia Socio-Medica 2021; 33: 88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Donkers MA, Gilissen VJ, Candel MJ, et al. Moral distress and ethical climate in intensive care medicine during COVID-19: a nationwide study. BMC Medical Ethics 2021; 22: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Prompahakul C, Keim-Malpass J, LeBaron V, et al. Moral distress among nurses: a mixed-methods study. Nurs Ethics 2021; 28: 1165–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Petrișor C, Breazu C, Doroftei M, et al. Association of moral distress with anxiety, depression, and an intention to leave among nurses working in intensive care units during the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare Multidisc Dig Publish Ins, 2021; 9: 1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bleicher J, Place A, Schoenhals S, et al. Drivers of moral distress in surgical intensive care providers: a mixed methods study. J Surg Res 2021; 266: 292–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guttmann K, Flibotte J, Seitz H, et al. Goals of care discussions and moral distress among neonatal intensive care unit staff. J Pain Symptom Manage 2021; 62: 529–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Miljeteig I, Forthun I, Hufthammer KO, et al. Priority-setting dilemmas, moral distress and support experienced by nurses and physicians in the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in Norway. Nurs Ethics 2021; 28: 66–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tajalli S, Rostamli S, Dezvaree N, et al. Moral distress among Iranian neonatal intensive care units’ health care providers: a multi-center cross sectional study. J Med Ethics Hist Med 2021; 14: 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Işık MT, Yıldırım G. Individualized care perceptions and moral Distress of intensive care nurses. Nurs in Crit Care. Online published, 2021. 10.1111/nicc.12715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sedghi Goyaghaj N, Zoka A, Mohsenpour M. Moral sensitivity and moral distress correlation in nurses caring of patients with spinal cord injury. Clin Ethics 2021; 17: 147775092199427. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fujii T, Katayama S, Miyazaki K, et al. Translation and validation of the Japanese version of the measure of moral distress for healthcare professionals. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2021; 19: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nemati R, Moradi A, Marzban M, et al. The association between moral distress and mental health among nurses working at selected hospitals in Iran during the COVID-19 pandemic. Work 2021; 70: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Khorashadizadeh F, Zare NV, Mohajer S, et al. Relationship between moral distress and Virtue-oriented Ethical behavior in nurses working in Government Hospitals in Bojnourd and Nursing Homes in Bojnourd and Mashhad in 2017. Pakistan J Med Health Sci 2021; 15: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Meese KA, Colón-López A, Singh JA, et al. Healthcare is a team sport: stress, resilience, and correlates of well-being among health system employees in a crisis. J Healthc Manage 2021; 66: 304–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kok N, Van Gurp J, van der Hoeven JG, et al. Complex interplay between moral Distress and other risk factors of burnout in ICU professionals: findings from a cross-sectional survey study. BMJ Quality & Safety 2021. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Safarpour H, Ghazanfarabadi M, Varasteh S, et al. The association between moral distress and moral courage in nurses: a cross-sectional study in Iran. Iranian J Nurs Midwifery Res 2020; 25: 533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Barr P. Moral distress and considering leaving in NICU nurses: direct effects and indirect effects mediated by burnout and the hospital ethical climate. Neonatology 2020; 117: 646–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fard ZR, Azadi A, Veisani Y, et al. The association between nurses’ moral distress and sleep quality and their influencing factor in private and public hospitals in Iran. J Educ Health Prom 2020; 9: 268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sedaghati A, Assarroudi A, Akrami R, et al. Moral distress and its influential factors in the nurses of the nursing homes in khorasan provinces in 2019: a descriptive-correlational study. Iranian J Nurs Midwifery Res 2020; 25: 319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Af Sandeberg M, Bartholdson C, Pergert P. Important situations that capture moral distress in paediatric oncology. BMC Med Ethics 2020; 21: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Emmamally W, Chiyangwa O. Exploring moral distress among critical care nurses at a private hospital in Kwa-Zulu Natal, South Africa. South Afr J Crit Care 2020; 36: 104–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ramos FRS, Barth PO, Brehmer LCdF, et al. Intensity and frequency of moral distress in Brazilian nurses. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP 2020; 54: e035578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jones GA, Colville GA, Ramnarayan P, et al. Psychological impact of working in paediatric intensive care. A UK-wide prevalence study. Arch Dis Child 2020; 105: 470–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yeganeh MR, Pouralizadeh M, Ghanbari A. The relationship between professional autonomy and moral distress in ICU nurses of Guilan University of Medical Sciences in 2017. Nurs Practice Today 2019; 6(3): 133–141. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sannino P, Giannì ML, Carini M, et al. Moral distress in the pediatric intensive care unit: an Italian study. Front Pediatr 2019; 7: 338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wachholz A, Dalmolin GdL, Silva AMd, et al. Moral distress and work satisfaction: what is their relation in nursing work? Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP 2019; 53: e03510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pergert P, Bartholdson C, Blomgren K, et al. Moral distress in paediatric oncology: contributing factors and group differences. Nurs Ethics 2019; 26: 2351–2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bayat M, Shahriari M, Keshvari M. The relationship between moral distress in nurses and ethical climate in selected hospitals of the Iranian social security organization. J Med Ethics Hist Med 2019; 12: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fruet IMA, Dalmolin GdL, Bresolin JZ, et al. Moral distress assessment in the nursing team of a hematology-oncology sector. Revista brasileira de enfermagem 2019; 72: 58–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zabetian H, Zarei MJ, Honarmand Jahromy F, et al. Investigation of moral distress in nurses of Jahrom hospitals in 2018. J Res Med Dental Sci 2019; 7: 195–200. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Harorani M, Golitaleb M, Davodabady F, et al. Moral distress and self-efficacy among nurses working in critical care Unit in Iran-An analytical study. J Clin Diagn Res 2019; 13: 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Colville G, Dawson D, Rabinthiran S, et al. A survey of moral distress in staff working in intensive care in the UK. J Intensive Care Soc 2019; 20: 196–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Abdolmaleki M, Lakdizaji S, Ghahramanian A, et al. Relationship between autonomy and moral distress in emergency nurses. Indian J Med Ethics 2018; 6: 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Altaker KW, Howie-Esquivel J, Cataldo JK. Relationships among palliative care, ethical climate, empowerment, and moral distress in intensive care unit nurses. Am Journal Critical Care 2018; 27: 295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Asayesh H, Mosavi M, Abdi M, et al. The relationship between futile care perception and moral distress among intensive care unit nurses. J Med Ethics Hist Med 2018; 11: 2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Robaee N, Atashzadeh-Shoorideh F, Ashktorab T, et al. Perceived organizational support and moral distress among nurses. BMC Nursing 2018; 17: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Alborzi J, Sabeti F, Baraz S, et al. Investigating of moral distress and attitude to euthanasia in the intensive care unit nurses. Int J Pediatr 2018; 6: 8475–8482. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lamiani G, Ciconali M, Argentero P, et al. Clinicians’ moral distress and family satisfaction in the intensive care unit. J Health Psychol 2020; 25: 1894–1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ajoudani F, Baghaei R, Lotfi M. Moral distress and burnout in Iranian nurses: the mediating effect of workplace bullying. Nurs Ethics 2019; 26: 1834–1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Neumann JL, Mau L-W, Virani S, et al. Burnout, moral distress, work–life balance, and career satisfaction among hematopoietic cell transplantation professionals. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2018; 24: 849–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Saleh ZN, Loghmani L, Rasouli M, et al. Moral distress and compassion fatigue in nurses of neonatal intensive care unit. Electron J Gen Med 2019; 16: 4. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sirilla J, Thompson K, Yamokoski T, et al. Moral distress in nurses providing direct patient care at an academic medical center. Worldviews Evidence-Based Nurs 2017; 14: 128–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Christodoulou-Fella M, Middleton N, Papathanassoglou ED, et al. Exploration of the association between nurses’ moral distress and secondary traumatic stress syndrome: implications for patient safety in mental health services. Biomed Research International 2017; 2017: 1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wenwen Z, Xiaoyan W, Yufang Z, et al. Moral distress and its influencing factors: a cross-sectional study in China. Nurs Ethics 2018; 25: 470–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lusignani M, Giannì ML, Re LG, et al. Moral distress among nurses in medical, surgical and intensive-care units. J Nurs Manage 2017; 25: 477–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ameri M, Safavibayatneed Z, Kavousi A. Moral distress of oncology nurses and morally distressing situations in oncology units. Aust J Adv Nurs 2016; 33: 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ando M, Kawano M. Association between moral distress and job satisfaction of Japanese psychiatric nurses. Asian/Pacific Island Nurs J 2016; 1: 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Soleimani MA, Sharif SP, Yaghoobzadeh A, et al. Spiritual well-being and moral distress among Iranian nurses. Nurs Ethics 2019; 26: 1101–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zavotsky KE, Chan GK. Exploring the relationship among moral distress, coping, and the practice environment in emergency department nurses. Adv Emerg Nurs J 2016; 38: 133–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Darabzadeh F, Abbaszadeh A, Shakeri N, et al. Surgical nurses perceptions of moral distress. Res J of Med Sci 2016; 10(4): 412–415. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Sauerland J, Marotta K, Peinemann MA, et al. Assessing and addressing moral distress and ethical climate part II: neonatal and pediatric perspectives. Dimensions Crit Care Nurs 2015; 34: 33–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Karagozoglu S, Yildirim G, Ozden D, et al. Moral distress in Turkish intensive care nurses. Nurs Ethics 2017; 24: 209–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Trotochaud K, Coleman JR, Krawiecki N, et al. Moral distress in pediatric healthcare providers. J Pediatr Nurs 2015; 30: 908–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Borhani F, Mohammadi S, Roshanzadeh M. Moral distress and perception of futile care in intensive care nurses. J Medical Ethics History Medicine 2015; 8: 2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Browning AM. CNE article: moral distress and psychological empowerment in critical care nurses caring for adults at end of life. Am J Crit Care 2013; 22: 143–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.de Boer J, van Rosmalen J, Bakker AB, et al. Appropriateness of care and moral distress among neonatal intensive care unit staff: repeated measurements. Nurs Critical Care 2016; 21: e19–e27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ganz FD, Wagner N, Toren O. Nurse middle manager ethical dilemmas and moral distress. Nurs Ethics 2015; 22: 43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sauerland J, Marotta K, Peinemann MA, et al. Assessing and addressing moral distress and ethical climate, part 1. Dimensions Crit Care Nurs 2014; 33: 234–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Borhani F, Abbaszadeh A, Nakhaee N, et al. The relationship between moral distress, professional stress, and intent to stay in the nursing profession. J Medical Ethics History Medicine 2014; 7: 3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hamaideh SH. Moral distress and its correlates among mental health nurses in Jordan. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2014; 23: 33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Karanikola MN, Albarran JW, Drigo E, et al. Moral distress, autonomy and nurse–physician collaboration among intensive care unit nurses in Italy. J Nursing Management 2014; 22: 472–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Shoorideh FA, Ashktorab T, Yaghmaei F, et al. Relationship between ICU nurses’ moral distress with burnout and anticipated turnover. Nurs Ethics 2015; 22: 64–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wilson MA, Goettemoeller DM, Bevan NA, et al. Moral distress: levels, coping and preferred interventions in critical care and transitional care nurses. J Clin Nurs 2013; 22: 1455–1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ganz FD, Raanan O, Khalaila R, et al. Moral distress and structural empowerment among a national sample of Israeli intensive care nurses. J Adv Nurs 2013; 69: 415–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Fernandez-Parsons R, Rodriguez L, Goyal D. Moral distress in emergency nurses. J Emerg Nurs 2013; 39: 547–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.DeKeyser Ganz F, Berkovitz K. Surgical nurses’ perceptions of ethical dilemmas, moral distress and quality of care. J Advanced Nursing 2012; 68: 1516–1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Lazzarin M, Biondi A, Di Mauro S. Moral distress in nurses in oncology and haematology units. Nurs Ethics 2012; 19: 183–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Papathanassoglou ED, Karanikola MN, Kalafati M, et al. Professional autonomy, collaboration with physicians, and moral distress among European intensive care nurses. Am J Crit Care 2012; 21: e41–e52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.De Villers MJ, DeVon HA. Moral distress and avoidance behavior in nurses working in critical care and noncritical care units. Nurs Ethics 2013; 20: 589–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Soodabeh J, Forough R, Fatemeh H, et al. Relationship between moral distress and job satisfaction among nurses of Tehran University of Medical Sciences Hospitals, HAYAT 2012; 18: 30–41. [Google Scholar]

- 128.McAndrew NS, Leske JS, Garcia A. Influence of moral distress on the professional practice environment during prognostic conflict in critical care. J Trauma Nurs JTN 2011; 18: 221–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Ohnishi K, Ohgushi Y, Nakano M, et al. Moral distress experienced by psychiatric nurses in Japan. Nurs Ethics 2010; 17: 726–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Pauly B, Varcoe C, Storch J, et al. Registered nurses’ perceptions of moral distress and ethical climate. Nurs Ethics 2009; 16: 561–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Elpern EH, Covert B, Kleinpell R. Moral distress of staff nurses in a medical intensive care unit. Am J Crit Care 2005; 14: 523–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]