Abstract

As Teen Dating Violence (TDV) has gained attention as a public health concern across the United States (US), many efforts to mitigate TDV appear as policies in the 50 states in the form of for programming in K-12 schools. A keyword search identified 61 state-level school-based TDV policies. We developed an abstraction form to conduct a content analysis of these policies and generated descriptive statistics and graphic summaries. Thirty of the policies were original and 31 were additions or revisions of policies enacted by 17 of the 30 states previously. Of a possible score of 63, the minimum, mean, median, and maximum scores of currently active policies were 3.0, 17.7, 18.3 and 33.8, respectively. Results revealed considerable state-to-state variation in presence and composition of school-based TDV policies. Opportunity for improving policies was universal, even among those with most favorably scores.

Keywords: teen dating violence, adolescent dating violence, public health law, K-12 programming

Introduction

Teen dating violence (TDV) is a prevalent and preventable public health challenge. While this type of harm impacts many societies, and many prevention strategies foreseeably transcend social, cultural and political contexts, this work offers a summary of the U.S. policies enacted in an effort to mitigate TDV. The United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention defines TDV as: “verbal, physical, emotional, psychological, or sexual abuse in a dating relationship, including stalking and perpetration via electronic media” [1] when “one or both partners is between thirteen and twenty years of age” [2]. TDV can cause acute physical injuries and mental health concerns and influence long- term health outcomes, including an increased risk for pregnancy, risky sexual behavior, eating disorders, substance abuse, suicide or suicidal ideation [3], victimization in adult relationships [4], depression, smoking, and binge drinking [5].

The public health burden of TDV disproportionately falls on teenage girls and teens who are Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual [6]. National figures from the US 2015 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) indicate that among students who dated, the prevalence of physical TDV victimization was 40% higher among girls than boys (11.7% vs 7.4%), and sexual TDV rates were 2.6-times higher in girls than boys (14.0% vs 5.4%). State-based rates of TDV varied widely, with physical TDV highest in Arkansas (15.6%) and lowest in Massachusetts (6.7%) [7]. Prior research suggests approximately one out of five teens engage in an abusive relationship, and 10% of reported intentional injuries to adolescent girls are the result of dating violence by male partners [3].

Efforts to prevent and mitigate the consequences of TDV have largely taken the form of state policies that attempt to reduce teen dating violence through programming in kindergarten (K)-12 schools [8, 9]. K-12 schools are a common setting for health-related programming and supportive services to children and youth, including awareness building and prevention education around TDV [8]. These programs offer opportune access points for introducing awareness, prevention, and recognition strategies and opportunities for delivering support resources to the population at risk for TDV, and to the school staff with whom these teens engage. Schools are also sites of TDV incidents, and personnel often work with students who have expressed violent behavior toward someone in or out of school. Recent research, however, provides reason to suspect many US schools are not adequately prepared to address TDV for lack of awareness and understanding [4]. In a national survey of high school guidance counselors, a group often engaged in responding to TDV, 58% had not received TDV education, 81% were unaware of a school protocol for responding to TDV incidents, and 90% had not been trained to assist students victimized by TDV [10].

Violence prevention theoretical frameworks like the socioecological model suggest a need to implement interventions beyond the individual level [10], and studies of TDV laws and policies support this. Recent work has affirmed that improving TDV perpetration and responses to TDV behaviors require effective interventions to facilitate re-shaping social norms and culture around TDV [11]. Some states have enacted legislative action only recently, since 1992. The oldest TDV policy that has not been updated since its enactment in 2002. Thus, our figures display 2002 as the oldest year of enactment for a currently active policy, although the first state to enact a law did so in 1992, then updated it.) Policies meant to address public health concerns vary widely in terms of their written quality, implementation integrity ( the extent to which a policy’s implemented form aligns with what a policy’s authors intended to occur), and overall capacity to help implementers achieve the intended impact on health outcomes. A community-based participatory research effort conducted by Gulliot-Wright et al. [12] on Texas-specific TDV legislation and school-based curriculum found gaps in uptake of school-based prevention programming. They identified legislation that addressed individual- and system-level causes for violence as an important opportunity for prevention. Jackson et al. [13] also examined Texas-specific TDV policies from an implementation perspective and found most districts had developed basic policies and were making progress in implementation.

Nationally, Black, Hoefer, & Ricard [14] scored TDV policies using the advocacy group Break the Cycle’s A – F grading system. This system focuses on ability youth (those under age 18) to make use of civil protective orders and modeled their relationship with other system-level factors (state political and economic conditions) to TDV prevalence. They found an inverse association between the caliber of a TDV policy and TDV outcomes. Cascardi, et al. [15] examined TDV policies in the context of policies against ‘bullying’(a pattern of unwanted, aggressive behaviors involving a perceived power imbalance, and occurring between youths who are not family members or dating partners) based on the binary inclusion or exclusion of a purpose statement and discussion of prohibited behaviors and harmful effects, enumeration of school jurisdiction, discussion of protected groups, local or district policy development and implementation, designation of a specialist within schools, reporting or investigation procedures, and sanctions recommended.

To our knowledge, although TDV state policies have been studied and scored, a gold standard for assessing the elements in state laws does not yet exist. The goal of this work was to synthesize current approaches to TDV legislation and position future research efforts to elucidate what drives policy variation, and how TDV policy variation shapes TDV outcomes. Thus, we systematically abstracted and described states’ TDV law content and distinguished among those with presence, partial presence, or absence of 34 policy components.

Methods

Law students identified school-based state TDV policies from keywords searches in Westlaw®. Westlaw Codified Law Index terms for the search are reported elsewhere. [16] The study period was defined by the enactment dates of all policies identified in 2019: related policies were enacted as early as 1992 and as recently as 2018. The project leader (KH) organized the legal language by state and by effective periods in MonQcle (a software system developed by the Temple University Center for Public Health Law Research to support policy surveillance and scientific legal research projects) in preparation for component scoring.

School-based TDV Policy Abstraction Form Development

To understand states’ approaches to school-based TDV policy, the authors (HR, CP, AA, AE, KH) developed and applied an abstraction form to measure TDV policy components based on our literature search of peer-reviewed health sciences, social sciences, education, and law publications available as of 2019. As no one has yet established best practices to guide TDV legislative evaluation, our study team developed a scoring system to identify components of a comprehensive law and allowed for components to be designated as present, partially present, or absent. Four sources guided our scoring system for components: US Department of Education (DOE) recommendations on best practices for anti-bullying laws and policies [17], policy elements in existing laws [18], Start Strong’s TDV model school policy [19] and best practices for public health law evaluation [20]. The team (HR, CP, AA, AE, KH) that developed the scoring system was multidisciplinary with broad expertise: a legal expert on family law pertaining to intimate partner violence, an epidemiologist with experience in domestic violence research, two injury epidemiologists with experience conducting violence research and policy evaluations, and a biostatistician with experience conducting longitudinal, hierarchical modeling analysis.

Select authors (HR, AA, KH)revised our original abstraction form using an iterative process during a pilot period. Three individuals (HR, AA,KH) with graduate training in public health and experience working with sexual and intimate partner violence policies piloted use of the abstraction form with policies from two states that the same select authors (HR, AA, KH) perceived to present low risk for error in coding (Michigan and Pennsylvania), from two states perceived to present moderate risk for error in coding (Delaware and Massachusetts), and from two states perceived to present high risk for error in coding (California and Connecticut). In coding, the project leader (KH) assessed initial abstraction results of two authors (HR, AA) for areas of frequent (recurrent in piloted policies) or severe discrepancy (scores by one party indicating full presence of a component and another party indicating absence), or both. The authors (HR, CP, AA, AE, KH) clarified intent and criteria for coding each abstraction item of concern. The authors (HR, CP, AA, AE, KH) retained in the final version all the originally proposed sections of the instrument. Full abstraction occurred after the pilot process was complete.

Policy Element Abstraction & Analysis

Abstraction Process

We included 34-items in the abstraction form, organized into 7 sections. The full abstraction form is available in Appendix A. We scored each item in each Section from 0 – 2 scale where 0 indicated the element was not present, 1 that it was partially present or encouraged, and, 2 that it was fully present or required. We standardized the item on the minimum number of years of TDV prevention education for students to a 0-12 scale (of years of schooling) from a 0-13 scale (thus some scores involve decimals).

Two graduate students (HR, AA) with training in public health, public policy, and violence research (neither of whom participated in the piloting of the instrument) completed formal abstraction using MonQcle®; the project leader (KH) adjudicated discrepancies. During the abstraction process, we first coded the original policies of the 30 states that had any policy, then coded any subsequent updates. Each student carried out abstraction independently, prior to the generation of the Krippendorff’s alpha for inter-rater reliability to correct for change agreement, handle multiple coders, and measure intercoder agreement for nominal, ordinal, and interval data. [21] The inter-rater reliability score generated using Krippendorf’s alpha was 0.88.

Analysis of Abstracted Data

We separated states according to the presence or absence of school-based TDV policies, and assigned a scored of 0 for those with no laws. We isolated scores of states with school-based TDV policies to derive their distribution and a series of descriptive statistics. We generated descriptive statistics for each of the 7 policy component sections.

Several states had more than one score because they updated their school-based policy between the start and end of the analysis period (1992 – 2018). In these instances, we used the overall score and Section-specific scores of the current policy. To determine the presence of a temporal trend we assessed changes in state policy scores, in each state, over time, using a Pearson correlation test for policy score and year of enactment.

Results

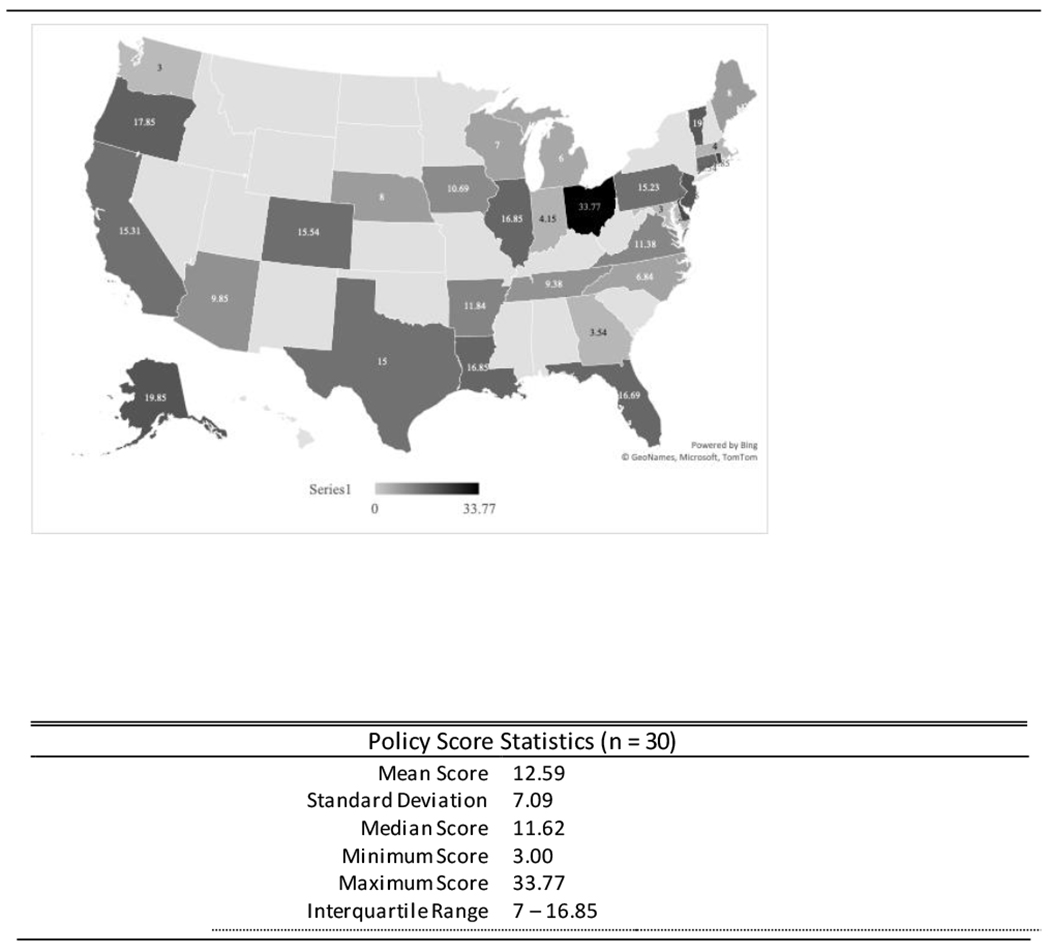

Thirty states had enacted at least one related policy by 2019, scoring between 3 and 33.77 out of a possible 68. Our TDV policy search yielded 61 policies from 30 states. Of these, 30 policies were original, and 31 were additions or revisions enacted by 17 of the 30 states. Table 1 displays states with policies, scores for currently active policies, and the year the state enacted its latest policy. Twenty-one states enacted no TDV policy between 1992 and 2018. States enacted policies with the lowest scores in 2005, 2015, and 2017, and with the highest scores in 2011, 2017, and 2018. The highest component score was Ohio’s at 33.77, and the lowest component score observed was 3, held by both Maryland and Washington. California, Connecticut, Tennessee, Ohio, and Virginia implemented or revised TDV policies most recently. Maine Michigan and Washington maintained policies for the longest duration. The association between the date of enactment and the component score is not significant (correlation of 0.501). For policies active in 2018 or earlier, the mean year of enactment was 2012. California had the largest number of policy updates (5 revisions since 1994).

Table 1.

States with currently active TDV school policies and their scores at a scored year

| 30 States With TDV School Policies* | Score | Scored Year |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Maryland | 3.00 | 2017 |

| Washington | 3.00 | 2005 |

| Georgia | 3.54 | 2015 |

| Massachusetts | 4.00 | 2010 |

| Indiana | 4.15 | 2010 |

| Michigan | 6.00 | 2004 |

| North Carolina | 6.84 | 2009 |

| Wisconsin | 7.00 | 2012 |

| Nebraska | 8.00 | 2009 |

| Maine | 8.00 | 2002 |

| Tennessee | 9.38 | 2018 |

| Arizona | 9.85 | 2010 |

| Iowa | 10.69 | 2007 |

| Virginia | 11.38 | 2018 |

| Arkansas | 11.84 | 2015 |

| Texas | 15.00 | 2015 |

| Pennsylvania | 15.23 | 2011 |

| California | 15.31 | 2018 |

| Colorado | 15.54 | 2016 |

| Connecticut | 16.54 | 2018 |

| Florida | 16.69 | 2014 |

| Louisiana | 16.85 | 2014 |

| Illinois | 16.85 | 2013 |

| Oregon | 17.85 | 2016 |

| Vermont | 19.00 | 2011 |

| New Jersey | 19.85 | 2014 |

| Alaska | 19.85 | 2017 |

| Rhode Island | 21.85 | 2011 |

| Delaware | 22.00 | 2017 |

| Ohio | 33.77 | 2018 |

Note: The 21 States without TDV school policies as of 2019 are Alabama, Hawaii, Idaho, Kansas, Kentucky, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Utah, Virginia, West Virginia, Wyoming.

Table 2 summarizes policy component scores, identifying the state with the lowest and highest for each. The abstract form version used to score school-based TDV polices is available in Supplemental Material Appendix C). States’ more recent policies generally had the highest component score, except for revisions in Maryland and New Jersey. Maryland’s updated policy lowered the total score from 5 in 2010 to 3 in 2012, reflecting a reduction of the policy’s Section 5 score from 4 to 2 after that allowing students’ parents to opt them out of the TDV-related curriculum. New Jersey’s score change over time was the most dramatic, increasing from 6.0 in 2003 to 20.92 in 2011. New Jersey’s updated policy lowered the total score from 20.92 in 2011 to 19.85 in 2014, after Section 4 score decreased from 5 to 4 after removal of the term ‘comprehensive’ (see Supplemental Material Appendix B for full detail on within-state policy score changes).

Table 2.

TDV School Policy Score Elements for States with a Policy

| Policy Abstraction Form Elements | Range of Possible Scores | Mean (Standard Deviation) | State(s) with the Highest Scoring Policy | State(s) with the Lowest Scoring Policy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Section 1

-- Types of schools Covered (1 2-point item) |

0-2 | 0.93 (0.25) | All other states scored 1. | VA & WA (0) |

|

Section 2

– Definitions (6 2-point items) |

0-14 | 1.43 (1.74) | NJ (6) | AR, GA, IN, IA, ME, MD, MA, MI, NE, NC, TN, VT, VA, WA (0) |

|

Section 3

– District Policy (3 2-point items) |

0-6 | 0.6 (1.19) | DE (5) | AZ, AR, CA, CO, GA, IN, IA, LA, ME, ME, MA, MI, NE, NC, PA, TN, VT, VA, WA, WI (0) |

|

Section 4

– District Policy Components (10 2-point items) |

0-20 | 1.7 (2.64) | OH (11) | CT, GA, IA, LA, ME, MD, MA, MI, NE, NC, VT, VA, WA, WI (1) |

|

Section 5

– Dating Violence Prevention Education for Students (7 2-point items; items 5c and 5d required standardization to fit a 2-point scale) |

0-14 | 6.23 (2.24) | AR (9.85) | MD (2) |

|

Section 6

– Dating Violence Prevention Education for School Staff (5 2-point items) |

0-10 | 2.23 (2.78) | AK, CT, LA (8) | AZ, AR, GA, IN, IA, MD, MA, MI, NE, NJ, NC, WA, WI (0) |

|

Section 7

– Protections and Legal Rights (1 2-point item) |

0-2 | 0.06 (0.25) | PA, TX (1) | All other states scored 0. |

| Total Scores | 0-68 | 12.59 (7.09) | OH (33.77) | MD, WA (3) |

All states received the same component score for the types of schools covered, with no states covering non-public schools (although states do have jurisdiction over educational content required in all types of schools). Section 2 components most prevalent across policies included inclusion of: a purpose and prohibition statements, a definition consistent with the CDC definition of TDV, and specification of policy scope. Fewer policies included electronic communication (text messaging, social media messaging and posts) components within their TDV definitions, offered TDV definitions that enumerated groups, or discussed harms associated with TDV. New Jersey ranked highest in the definition section, (score of 6 of 14). Delaware ranked highest in the district policy section (5 of 6) for having required districts to adopt policies by a specified date and for having provisions for reviewing district policies and reports of TDV incidents to the DOE. Some states called for districts to adopt policies but failed to specify a date or need for policy review and incident reporting provisions in them. District policy scores in Section 4 were highest for Ohio (11 of 20), then Delaware (9 of 20). Most leading states had fewer than half of district policy elements of an ideal policy.

With respect to dating violence education for students, Arkansas led with a score of 9.85 of 14. All states with TDV policies at least encouraged dating violence prevention education for students, but most did not include the remaining policy components of Section 5. Maryland, with a score of 2, ranked lowest here. Policies of many states included no dating violence prevention education for school staff-related (13 of all 30 states with a school-based TDV policy scored 0 in this section). Alaska, Connecticut, and Louisiana scored highest; 8 of 10, due to including 4 of the 5 major provisions. The final section contained only one element – availability to victims of school-based alternatives to protective orders or school transfer options, or both. Except for Pennsylvania and Texas, state TDV policies included neither of these.

Figure 1 displays a map of scores for 2019 together with the summary statistics for TDV school policies active as of 2019.

Figure 1.

2019 TDV Policy Score Heat Map by State

Discussion

This policy content analysis revealed considerable variation in presence and composition of school-based TDV policies from state-to-state. It also revealed universal opportunity for policy improvement: even the states with the most comprehensive policies scored about halfway toward an ideal policy with all components (33.77 / 68.0). Important opportunities for improvement include: explicitly expanding the scope of school-based TDV policies to encompass both public and private schools; incorporating broader TDV training; establishing provisions for in-school protective orders; supporting victims with protective orders and transfer options; and, eliminating parental ability to opt their student out of healthy relationship programming. While scores generally improved as states revised policies over time, no strong relationship appeared between the year of enactment and a policy score across states.

Acting on these opportunities could advance the health and safety for those at risk because TDV victims face challenges finding resources to support them outside of school. Judicial authorities and police hold misconceptions about potential severity of TDV, assuming damage to be mild and short term [13]. Their views compound barriers TDV survivors encounter if they seek legal protections available to adult survivors. Thus, state policies that call for schools to prepare and address TDV are critical to effective prevention and intervention.

Beyond K-12 educational settings (one dimension of the socioecological model’s societal and community layer) research has identified other factors that indicate probability of violence within teen dating partnerships: prosocial beliefs (the view that positive, healthy interactions will be helpful to an individual, and negative, unhealthy interactions will be detrimental to an individual), emotional competencies, alcohol consumption patterns, exposure to violent family conflict, parental monitoring and parental discipline practices, social connectedness in one’s school, and exposure to violent neighborhood settings [22–24]. Other policies may offer levers to mitigate risk factors / support protective factors for TDV that are active in societal, community, and relational contexts.

Limitations and next steps

Although we conducted a comprehensive search of state TDV laws that impact schools, the search process may not have captured every school-based policy relevant to TDV. We did not examine policies that impact other types of school violence or sexual health programming, except for that of states which placed their teen dating violence provisions within sexual health policies. Future research should elucidate additional risk and protective factors for TDV and model the impact of specific K-12 TDV programming provisions on TDV outcomes; examine what promotes the uptake of robust K-12 TDV programming and identify and evaluate strategies beyond school-based interventions for preventing TDV and mitigating its consequences.

Examining sexual health and wellness education policies at the state and district level may also shed insight on opportunities for preventing harm in teen dating relationships. Even so, our detailed data can assist other researchers to explain what factors may be driving the policy variation and how variation shapes TDV outcomes.

Conclusion

TDV is a preventable harm that compromises population health across societies. The policy variation measured in this work revealed that all U.S. states have the opportunity to revise their policies to be more comprehensive. This work also creates a foundation for quasi-experimental studies to identify which policy components are most protective against TDV in the U.S.. It similarly offers a foundation for policies of other nations to be abstracted and analyzed against TDV outcomes of other societies. Related findings can and should inform policy decisions aiming to reduce TDV within US and international contexts.

Supplementary Material

Key messages:

Teen dating violence (TDV) is a prevalent and preventable public health challenge across societies.

Policies enacted by U.S. states to prevent and respond to TDV often make use of K-12 programming, and vary widely in terms of their presence and written caliber.

All TDV policies active in U.S. states as of 2019 have the opportunity to improve their comprehensiveness, with the most robust policy (enacted in Ohio in 2018) scoring only 33.77 out of a possible 68.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Maria Doering Critchlow, Paden Hanson, and Erick Orantes for performing the keyword searches that identified the policies included in this work’s content analysis.

Funding Sources

This work was funded through the CDC/NCIPC-funded University of Iowa Injury Prevention Research Center (CDC/NCIPC R49CE002108).

Biographies

About the authors:

Hannah I. Rochford, MPH is a PhD student at the Injury Prevention Research Center, 2190 Westlawn, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa, USA

Corinne Peek-Asa, PhD is the Director at the Injury Prevention Research Center, 2190 Westlawn, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa, USA

Anne Abbott, MPP is a PhD Student and Program Director at the National Resource Center for Family-Centered Practice, University of Iowa, Coralville, Iowa, USA.

Ann Estin, JD, is professor of family law at the College of Law, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa, USA.

Karisa Harland, PhD, is an assistant professor at the Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa, USA

Footnotes

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material contains Appendices A, B, and C.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Teen Dating Violence Fact Sheet. 2014. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/tdv-factsheet.pdf Accessed January 6, 2016.

- 2.Carlson CN. Invisible victims: Holding the educational system liable for teen dating violence at school. Harv. Women’s LJ. 2003;26:351. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silverman JG, Raj A, Mucci LA, Hathaway JE. Dating violence against adolescent girls and associated substance use, unhealthy weight control, sexual risk behavior, pregnancy, and suicidality. jama. 2001. Aug 1;286(5):572–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levy B, Giggans PO. What parents need to know about dating violence. Seal Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Exner-Cortens D, Eckenrode J, Rothman E. Longitudinal associations between teen dating violence victimization and adverse health outcomes. Pediatrics. 2013. Jan 1;131(1):71–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth online: High school YRBS - United States 2019 Results | DASH | CDC. Retrieved from https://nccd.cdc.gov/youthonline/App/Results.aspx?OUT=&SID=HS&QID=&LID=XX&YID=&LID2=&COL=&ROW1=&ROW2=&FR=&FG=&FSL=&FGL=&PV=&TST=&C1=&C2=&QP=&SYID= . Accessed June 6, 2022 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zaza S, Kann L, Barrios LC. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents: Population estimate and prevalence of health behaviors. Jama. 2016. Dec 13;316(22):2355–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De La Rue L, Polanin JR, Espelage DL, Pigott TD. A meta-analysis of school-based interventions aimed to prevent or reduce violence in teen dating relationships. Review of Educational Research. 2017. Feb;87(1):7–34. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Break the Cycle. 2010 State Law Report Cards: A National Survey of Teen Dating Violence Laws. Los Angeles, CA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khubchandani J, Price JH, Thompson A, Dake JA, Wiblishauser M, Telljohann SK. Adolescent dating violence: A national assessment of school counselors’ perceptions and practices. Pediatrics. 2012. Aug 1;130(2):202–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dahlberg LL, Krug EG. Violence: a global public health problem. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva. 2006;11:1163–78. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guillot-Wright S, Lu Y, Torres ED, Macdonald A, Temple JR. Teen Dating Violence Policy: An Analysis of Teen Dating Violence Prevention Policy and Programming.

- 13.Jackson RD, Bouffard LA, Fox KA. Putting policy into practice: Examining school districts’ implementation of teen dating violence legislation. Criminal Justice Policy Review. 2014. Jul;25(4):503–24. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoefer R, Black B, Ricard M. The impact of state policy on teen dating violence prevalence. Journal of Adolescence. 2015. Oct 1;44:88–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cascardi M, King CM, Rector D, DelPozzo J. School-based bullying and teen dating violence prevention laws: overlapping or distinct?. Journal of interpersonal violence. 2018. Nov;33(21):3267–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harland KK, Vakkalanka JP, Peek-Asa C, Saftlas AF. State-level teen dating violence education laws and teen dating violence victimisation in the USA: a cross-sectional analysis of 36 states. Injury prevention. 2021. Jun 1;27(3):257–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stuart-Cassel V, Bell A, Springer JF. Analysis of State Bullying Laws and Policies. Office of Planning, Evaluation and Policy Development, US Department of Education. 2011. Dec. [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Conference of State Legislatures. Teen Dating Violence. 2015. Retrieved from http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/teen-dating-violence.aspx. Accessed December 5, 2015.

- 19.Schaeffer S, Lee D, Gallopin C, Rosewater A, Vollandt L, Rosenbluth B, Ball B, Miller K, Alex C. School and District Policies to Increase Student Safety and Improve School Climate: Promoting Health Relationships and Preventing Teen Dating Violence. Futures Without Violence. 2012. Retrieved from https://startstrong.futureswithoutviolence.org/wp-content/uploads/school-and-districtpolicies-and-appendix.pdf Accessed January 6, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hall MA. Coding case law for public health law evaluation: A methods monograph for the Public Health Law Research Program (PHLR) Temple University Beasley School of Law. Public Health Law Research, November. 2011. Nov 26. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang N, Kara A, Laskey HA, Seaton FB. A SAS MACRO for calculating intercoder agreement in content analysis. Journal of Advertising. 1993. Jun 1;22(2):17–28. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foshee V, Reyes L, Tharp A, Chang L, Ennett S, Simon T, Latzman N, Suchindran C. Shared longitudinal predictors of physical peer and dating violence. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2015. Jan 1; 56(1):106–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foshee V, McNaughton Reyes H, Chen M, Ennett S, Basile K, DeGue S, Vivolo-Kantor A, Moracco K, Bowling J. Shared risk factors for the perpetration of physical dating violence, bullying, and sexual harassment among adolescents exposed to domestic violence. Journal of youth and adolescence. 2016. Apr;45(4):672–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flaspohler P, Elfstrom J, Vanderzee K, Sink H, Birchmeier Z. Stand by me: The effects of peer and teacher support in mitigating the impact of bullying on quality of life. Psychology in the Schools. 2009. Aug;46(7):636–49. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.