Abstract

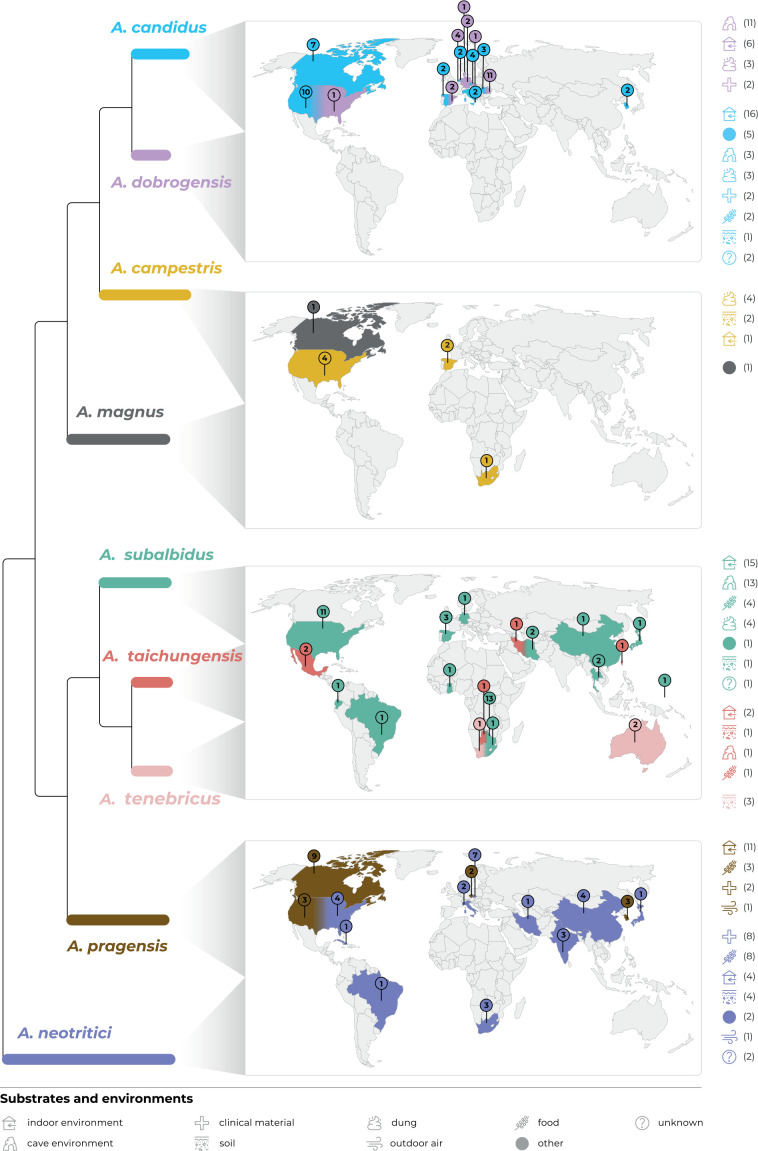

Aspergillus section Candidi encompasses white- or yellow-sporulating species mostly isolated from indoor and cave environments, food, feed, clinical material, soil and dung. Their identification is non-trivial due to largely uniform morphology. This study aims to re-evaluate the species boundaries in the section Candidi and present an overview of all existing species along with information on their ecology. For the analyses, we assembled a set of 113 strains with diverse origin. For the molecular analyses, we used DNA sequences of three house-keeping genes (benA, CaM and RPB2) and employed species delimitation methods based on a multispecies coalescent model. Classical phylogenetic methods and genealogical concordance phylogenetic species recognition (GCPSR) approaches were used for comparison. Phenotypic studies involved comparisons of macromorphology on four cultivation media, seven micromorphological characters and growth at temperatures ranging from 10 to 45 °C. Based on the integrative approach comprising four criteria (phylogenetic and phenotypic), all currently accepted species gained support, while two new species are proposed (A. magnus and A. tenebricus). In addition, we proposed the new name A. neotritici to replace an invalidly described A. tritici. The revised section Candidi now encompasses nine species, some of which manifest a high level of intraspecific genetic and/or phenotypic variability (e.g., A. subalbidus and A. campestris) while others are more uniform (e.g., A. candidus or A. pragensis). The growth rates on different media and at different temperatures, colony colours, production of soluble pigments, stipe dimensions and vesicle diameters contributed the most to the phenotypic species differentiation.

Taxonomic novelties: New species: Aspergillus magnus Glässnerová & Hubka; Aspergillus neotritici Glässnerová & Hubka; Aspergillus tenebricus Houbraken, Glässnerová & Hubka.

Citation: Glässnerová K, Sklenář F, Jurjević Ž, Houbraken J, Yaguchi T, Visagie CM, Gené J, Siqueira JPZ, Kubátová A, Kolařík M, Hubka V (2022). A monograph of Aspergillus section Candidi. Studies in Mycology 102: 1–51. doi: 10.3114/sim.2022.102.01

Keywords: Aspergillus candidus, Aspergillus tritici, genealogical concordance, integrative taxonomy, intraspecific variability, multispecies coalescent model

INTRODUCTION

Aspergillus is a large genus of filamentous fungi which is divided into 27 sections. Aspergillus section Candidi currently includes seven white- or yellow-sporulating species (Houbraken et al. 2020). Members of this section show a relatively uniform morphology and their identification to a species level is non-trivial when using only phenotypic characters. The first modern monograph of the section was published by Varga et al. (2007) who used a polyphasic approach for species delimitation (combination of morphology, physiology, exometabolite profiles and molecular data) and recognized A. candidus [MB 204868] and three other species: A. tritici [MB 309248] (Mehrotra & Basu 1976), A. campestris [MB 110495] (Christensen 1982) and A. taichungensis [MB 434473] (Yaguchi et al. 1995). Since then, another three species have been described, namely, A. subalbidus [MB 809190] (Visagie et al. 2014), A. pragensis [MB 800371] (Hubka et al. 2014) and A. dobrogensis [MB 821313] (Hubka et al. 2018b).

The studies of Varga et al. (2007), Visagie et al. (2014) and Hubka et al. (2014) used a combination of morphology, phylogeny and/or profiles of exometabolites for species description (polyphasic approach). Another widely used approach in fungal taxonomy, GCPSR (Genealogical Concordance Phylogenetic Species Recognition), has not been applied in section Candidi. This approach involves comparisons of topologies of single-locus phylogenetic trees and search for monophyletic genealogical groups that are concordantly well-supported (Taylor et al. 2000, Dettman et al. 2003a). More recently, new phylogenetic methods based on the multispecies coalescent model (MSC) have been implemented in taxonomy (Fujisawa et al. 2016). These methods take into account for example the incomplete lineage sorting, a most common reason for incongruences in tree topologies constructed on the basis of different loci (Edwards 2009, Mirarab et al. 2016). The application of these methods on section Candidi led to segregation of A. candidus into two species and description of A. dobrogensis (Hubka et al. 2018b).

The best known and the first described member of this section is A. candidus, a xerophilic species which is able to grow on substrates with low water activity like stored grains and seeds, where it can reduce the grains’ germinability (Thom & Raper 1945, Papavizas & Christensen 1960, Raper & Fennell 1965). It is also frequently found in the indoor environment, on food products (flour, cereals, spices, nuts), in soil or in the marine environment (Weidenbörner & Kunz 1994, Pitt & Hocking 1997, Klich 2002, Wei et al. 2007, Visagie et al. 2017). The section also encompasses several clinically relevant representatives which occasionally cause superficial (onychomycosis or otitis externa) or invasive mycoses, or contaminate clinical samples. Among these, A. tritici and A. candidus are confirmed etiological agents of some infections, while A. pragensis and A. dobrogensis have only been isolated from clinical samples and their clinical significance remains questionable (Moling et al. 2002, Hubka et al. 2012, Hubka et al. 2014, Becker et al. 2015, Nouripour-Sisakht et al. 2015, Gupta et al. 2016, Masih et al. 2016, Carballo et al. 2020, Kaur et al. 2021).

Members of the section Candidi produce many industrially important enzymes and secondary metabolites with a biotechnological potential. For example, they produce extracellular lipases, xylanases and cellulases which have potential to be used in the waste degradation processes (Milala et al. 2009, Garai & Kumar 2013, Farias et al. 2015) or metabolites with antioxidant activity which can be used in the process of maturing foods (Grazia et al. 1986, Pitt & Hocking 1997, Sunesen & Stahnke 2003). The production of bioactive metabolites with pharmacological potential has been identified in some species, for example chlorflavonin with antibiotic and antifungal effects (Munden et al. 1970, Marchelli & Vining 1973, Hubka et al. 2014), compounds with significant anti-oxidative activity such as candidusin B, 3-hydroxyterphenyllin or dihydroxymethyl pyranone (Yen et al. 2001, Elaasser et al. 2011), cytotoxic candidusin A, preussin or p-terphenyl derivatives (Kobayashi et al. 1982, Malhão et al. 2019, Lin et al. 2021) and many other recently discovered compounds with antitumor, antimicrobial, cytotoxic or antiviral activities such as ascandinines (Zhou et al. 2021), taichunines (El-Desoky et al. 2021), unguisins (Li et al. 2020) or other p-terphenyl derivatives (Han et al. 2020, Shan et al. 2020, Wang et al. 2020). The production of most of these secondary metabolites is usually attributed to A. candidus, but it is likely that the producer was misidentified in some cases with other species from section Candidi. For instance, production of p-terphenyl derivative 4″-deoxy-2′-methoxyterphenyllin attributed to A. candidus is in fact produced by A. subalbidus (Shan et al. 2020). Such re-identifications are, however, only possible when the isolate is accessioned and preserved in culture collections or DNA sequence data are available which is gradually becoming a standard in studies on compounds produced by microorganisms.

Previous studies focused on section Candidi included only a small number of strains and consequently, little is known about intraspecific genetic and phenotypic variability. Section Candidi members are widespread worldwide and occur on a wide range of substrates, but at low frequencies. During our past projects, a large collection of over a hundred strains belonging to the section Candidi has been gathered from various substrates and countries, and a high genetic and morphological variability has been observed within species which were previously considered to be relatively homogeneous. To determine if this variability reflects undescribed species diversity or a high intraspecific variability, we compared the data from phenotypic analyses, classical phylogenetic methods, GCPSR approach and delimitation methods based on coalescence theory. According to the resulting taxonomic conclusions, we revised the descriptions of all supported species in the section.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains

This study builds upon previous taxonomic studies dealing with section Candidi (Varga et al. 2007, Hubka et al. 2014, Visagie et al. 2014, Hubka et al. 2018b). The majority of new and yet unpublished strains were isolated from indoor environments, caves and dung. The isolation techniques mostly followed the procedures previously described by Jurjević et al. (2015), Nováková et al. (2018), Guevara-Suarez et al. (2020) and Visagie et al. (2021). Remaining strains were obtained from culture collections and collaborators, and originated from diverse substrates and countries. In total, we gathered 113 strains and detailed information about their provenance is listed in Table 1. Dried holotype and isotype specimens of the newly described species were deposited into the herbarium of the Mycological Department, National Museum, Prague, Czech Republic (PRM).

Table 1.

List of strains from Aspergillus section Candidi examined in this study.

| Species | Strain No.a | Provenance: country, locality, substrate, year, collector/isolator |

GenBank/ENA/DDBJ accession Nos.

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | benA | CaM | RPB2 | |||

| A. campestris | CBS 348.81 T = IMI 259099T = NRRL 13001T = IBT 13382T = IBT 28561T = ATCC 44563T = IFM 50931T = CCF 5596T | USA, North Dakota, near Zap, storage pile of topsoil displaced from a native, mixed prairie (Agropyron spp., Bouteloua gracilis), 1979, R.M. Miller & S.M. Pippen | EF669577 | EU014091 | EF669535 | EF669619 |

| IBT 17867 = CCF 5700 | USA, Wyoming, Pillot Hill Road, Medicine Bow National Forest, near Laramie, soil, 1994, J.C. Frisvad | ON156368 | ON164544 | ON164594 | ON164491 | |

| CCF 5641 = IFM 66789 = EMSL 1816 | USA, Wyoming, Gillette, air of living room, 2012, Ž. Jurjević | ON156369 | ON164567 | ON164616 | ON164514 | |

| FMR 15224 = CBS 142984 = CCF 6075 = IFM 66790 | Spain, Castile and Leon, Palencia, Monte el Viejo, Deer Reserve Park, herbivore dung, 2016, J. Gené & J.Z. Siqueira | LT798902 | LT798915 | LT798916 | LT798917 | |

| FMR 15226 = CBS 142985 = CCF 6053 | Spain, Castile and Leon, Palencia, Monte el Viejo, Deer Reserve Park, herbivore dung, 2016, J. Gené & J.Z. Siqueira | LT798903 | LT798918 | LT798919 | LT798920 | |

| IBT 23172 = IMI 073462 = CCF 5699 = IFM 66791 | USA, California, rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) dung, 1958, S. Stribling | ON156370 | ON164568 | ON164617 | ON164515 | |

| IMI 344489 | South Africa, Pretoria, mouse dung, deposited into IMI collection in 1991, R.Y. Anelich | ON156371 | ON164569 | ON164618 | ON164516 | |

| A. candidus | CBS 566.65T = IMI 091889T = NRRL 303T = IBT 28566T = ATCC 1002T = CCF 5594T | unknown, received by K.B. Raper and D.I. Fennell in 1909 from J. Westerdijk | EF669592 | EU014089 | EF669550 | EF669634 |

| CCF 488 = IBT 32273 | Czech Republic, tunnels of bark beetles, 1960, E. Kotýnková-Sychrová | FR733811 | LT626977 | LT626978 | LT626979 | |

| CCF 4029 = CMF ISB 1730 = IBT 32272 | Romania, Meziad Cave, bat droppings, 2009, A. Nováková | FR733813 | LT626980 | FR751424 | LT626981 | |

| CCF 3996 = CBS 134394 | Czech Republic, Prague, external auditory canal of 53-year-old man (otitis externa), 2010, P. Lysková | FR727137 | FR775325 | HE716843 | LT626982 | |

| CCF 5577 | Romania, Ungurului Cave, old bat guano, 2010, A. Nováková | LT626946 | LT626983 | LT626984 | LT626985 | |

| NRRL 58579 = CCF 5843 = IBT 33371 = EMSL 914 | USA, New York, indoor air of a home, 2008, Ž. Jurjević | LT626947 | LT626986 | LT626987 | LT626988 | |

| NRRL 58959 = CCF 5845 = EMSL 1252 | USA, Pennsylvania, indoor air of a home, 2009, Ž. Jurjević | LT626948 | LT626989 | LT626990 | LT626991 | |

| CCF 4912 = EMSL 2295 | USA, New Jersey, Cranbury, crawlspace metal duct (swab), 2014, Ž. Jurjević | LT626949 | LT626992 | LT626993 | LT626994 | |

| CCF 5172 | Czech Republic, Prague, mouse excrements in grain store, 2000, J. Hubert | LT626953 | LT627005 | LT627006 | LT627007 | |

| CCF 4713 | Romania, Ungurului Cave, bat guano, 2010, A. Nováková | LT626950 | LT626995 | LT626996 | LT626997 | |

| CCF 4659 | Czech Republic, Hustopeče, toenail of 52-year-old woman, 2012, S. Dobiášová | HG915889 | HG916672 | HG916681 | LT626998 | |

| CCF 4915 = EMSL 1285 | USA, Rhode Island, indoor air of living room, 2009, Ž. Jurjević | LT626951 | LT626999 | LT627000 | LT627001 | |

| NRRL 4646 = IMI 359076 = DTO 213-G2 = CBS 133061 | USA, barn litter, D.I. Fennell | EF669605 | EU014090 | EF669563 | EF669647 | |

| CCF 5675 = EMSL 2403 | USA, Pennsylvania, Feasterville, air in a basement of a house, 2014, Ž. Jurjević | LT626952 | LT627002 | LT627003 | LT627004 | |

| CCF 5576 = EMSL 2421 | USA, New York, Binghamton, air in bedroom, 2014, Ž. Jurjević | LT626954 | LT627008 | LT627009 | LT627010 | |

| DTO 223-E5 | The Netherlands, soil, 2012, M. Meijer | LT626955 | LT627011 | LT627012 | LT627013 | |

| CCF 6195 = EMSL 2721 | USA, Minnesota, Minneapolis, classroom dust, 2015, Ž. Jurjević | ON156372 | ON164545 | ON164634 | ON164492 | |

| CCF 6198 = EMSL 2863 | USA, Ohio, Westerville, air in basement (settle plates), 2015, Ž. Jurjević | ON156373 | ON164546 | ON164595 | ON164493 | |

| CCF 6200 = EMSL 2895 | USA, Massachusetts, Cohasset, air in bathroom, 2015, Ž. Jurjević | ON156374 | ON164547 | ON164596 | ON164494 | |

| CMW-IA 8 = CMW 58610 = CN138F7 = KAS 5864 | Canada, Nova Scotia, Wolfville, house dust, 2015, C.M. Visagie & A. Walker | — | ON164548 | ON164597 | ON164495 | |

| CMW-IA 9 = CMW 58611 = CN138F8 = KAS 6297 | Canada, Nova Scotia, Little Lepreau, house dust, 2015, C.M. Visagie & A. Walker | — | ON164549 | ON164598 | ON164496 | |

| CMW-IA 10 = CMW 58612 = CN138F9 = KAS 6134 | Canada, Nova Scotia, Wolfville, house dust, 2015, C.M. Visagie & A. Walker | — | ON164550 | ON164599 | ON164497 | |

| CMW-IA 11 = CMW 58613 = CN138G1 = KAS 6135 | Canada, Nova Scotia, Wolfville, house dust, 2015, C.M. Visagie & A. Walker | — | ON164551 | ON164600 | ON164498 | |

| A. dobrogensis | CCF 4651T = CCF 4655T = NRRL 62821T = IBT 32697T = CBS 143370T | Romania, Movile Cave, 2nd airbell, cave sediment, 2012, A. Nováková | LT626959 | LT627027 | LT558722 | LT627028 |

| IBT 29476 = CCF 5823 | Denmark, Høve Strand, mouse dung (in bed in summer house annex), 2007, J.C. Frisvad | LT907964 | LT907967 | LT907966 | LT907969 | |

| CCF 5567 | Romania, Meziad Cave, bat droppings, 2009, A. Nováková | LT626960 | LT627029 | LT627030 | LT627031 | |

| CCF 5568 | Romania, Liliecilor de la Guru Dobrogei Cave, Galeria Fossile, bat guano, 2010, A. Nováková | LT626961 | LT627032 | LT627033 | LT627034 | |

| CCF 4650 = CCF 4657 = NRRL 62820 = IBT 32699 | Romania, Meziad Cave, cave sediment, 2010, A. Nováková | LT626962 | LT627035 | LT627036 | LT627037 | |

| CCF 4649 = IBT 32700 | Romania, Liliecilor de la Guru Dobrogei Cave, Galeria Fossile, bat guano, 2010, A. Nováková | LT626963 | LT627038 | LT627039 | LT627040 | |

| CCF 5569 | Romania, Liliecilor de la Guru Dobrogei Cave, Galeria Fossile, bat guano, 2010, A. Nováková | LT626964 | LT627041 | LT627042 | LT627043 | |

| CCF 5570 | Romania, Liliecilor de la Guru Dobrogei Cave, Galeria Fossile, bat droppings, 2010, A. Nováková | LT626965 | LT627044 | LT627045 | LT627046 | |

| CCF 5573 | Romania, Liliecilor de la Guru Dobrogei Cave, cave air, 2011, A. Nováková | LT626966 | LT627047 | LT627048 | LT627049 | |

| CCF 5571 | Romania, Meziad Cave, hall in the upper floor, bat guano, 2010, A. Nováková | LT626967 | LT627050 | LT627051 | LT627052 | |

| CCF 5572 | Romania, Liliecilor de la Guru Dobrogei Cave, cave air, 2013, A. Nováková | LT626968 | LT627053 | LT627054 | LT627055 | |

| CCF 5574 | Romania, Liliecilor de la Guru Dobrogei cave, Galeria Fossile, bat droppings, 2014, A. Nováková | LT626969 | LT627056 | LT627057 | LT627058 | |

| CCF 5575 | Czech Republic, nails of 31-year-old woman, 2014, P. Lysková | LT626970 | LT627 059 | LT627060 | LT627061 | |

| CBS 225.80 = DTO 031-E6 | The Netherlands, human nail (contaminant), 1980, CBS | LT626971 | LT627062 | LT627063 | LT627064 | |

| DTO 025-I1 | Germany, carpet, 2006 | LT626972 | LT627077 | LT627078 | LT627079 | |

| DTO 013-C4 = IBT 28582 | The Netherlands, Maastricht, indoor air, 2006, J. Houbraken | LT626973 | LT627065 | LT627066 | LT627067 | |

| DTO 001-F9 = IBT 28576 | The Netherlands, surface of museum piece, 2004, J. Houbraken | LT626974 | LT627068 | LT627069 | LT627070 | |

| DTO 029-H2 | Germany, carpet, 2006 | LT626975 | LT627071 | LT627072 | LT627073 | |

| DTO 031-D9 = CBS 116945 = IBT 116945 = IBT 28573 | The Netherlands, Tiel, dust in museum, 2004, J. Houbraken | LT626976 | LT627074 | LT627075 | LT627076 | |

| CCF 5844 = EMSL No. 2810 | USA, New York, Lockport, indoor air in basement (settle plate), 2015, Ž. Jurjević | LT907963 | ON164552 | LT907965 | LT907968 | |

| FMR 15444 = CBS 142752 = CCF 6119 | Spain, Galicia, Lugo, Ribeira Sacra, herbivore dung, 2016, J. Guarro & M. Guevara-Suarez | LT798904 | LT798921 | LT798922 | LT798923 | |

| FMR 15601 = CCF 5846 | Spain, Galicia, Orense, Cortegada, herbivore dung, 2016, J. Guarro & M. Guevara-Suarez | ON156375 | LT962396 | ON164601 | ON164499 | |

| A. magnus | UAMH 1324T = IBT 14560T = CCF 6606T | Canada, Alberta, Edmonton, mouse collected on horsefarm, 1962, J.W. Carmichael | ON156376 | ON164570 | ON164619 | ON164517 |

| A. neotritici | CCF 3853T = IBT 32725T | Czech Republic, Prague, toenail of 62-year-old man, 2008, M. Skoøepová | FR727136 | FR775327 | HE661598 | LT627021 |

| CBS 266.81 = IBT 21956 = CCF 5842 | India, grains of Triticum aestivum, before 1976, B.S. Mehrotra | LT626958 | EU076293 | HG916678 | LT627017 | |

| CCF 4030 = CMF ISB 1300 = IBT 32729 | Czech Republic, Frýdek-Místek, vermicompost, 2001, A. Nováková | FR733814 | LT627018 | FR751425 | LT627019 | |

| CCF 4653 | Czech Republic, Prague, toenail of 58 -year-old woman, 2012, P. Lysková | HG915890 | HG916674 | HG916677 | LT627020 | |

| CCF 3314 | Czech Republic, Prague, outdoor air, 1996, A. Kubátová | FR733812 | LT627022 | FR751426 | LT627023 | |

| CCF 1649 | Czech Republic, Prague, flour, 1979, J. Svrčková | FR733810 | LT627024 | FR751427 | LT627025 | |

| NRRL 4847 = IMI 359077 = DTO 213-G3 = CBS 133055 = CCF 4809 | Japan (?), unknown, received by K.B. Raper and D.I. Fennell from CBS as Nakazawa′s strain of A. albus var. thermophilus | ON156395 | ON164587 | ON164628 | ON164537 | |

| CCF 4658 | Czech Republic, Prague, toenail of 69-year-old woman, 2008, M. Skoøepová | HG915891 | HG916675 | HG916676 | LT627026 | |

| DTO 201-D3 = CBS 129260 = RMF 7641 | USA, Nebraska, 1 mile north of Miller, loess soil, 6 feet deep, soil profile, 1984 | ON156397 | ON164591 | ON164632 | ON164541 | |

| DTO 201-G7 = RMF TC 215 = CBS 129307 | Unknown location, soil | ON156398 | ON164592 | ON164633 | ON164542 | |

| CCF 6202 = EMSL 3152 | USA, Florida, Key West, air in bedroom (settle plates), 2015, Ž. Jurjević | ON156396 | ON164588 | ON164629 | ON164538 | |

| CCF 6397 | Czech Republic, Havlíčkùv Brod, abdominal cavity of 62-year-old male with disseminated mycosis (probably caused by Rhizopus sp. and Trichosporon asahii), 2020, D. Lžičaøová | ON156394 | ON164589 | ON164630 | ON164539 | |

| CMW-IA 12 = CMW 58614 = CN117B9 | South Africa, Free State, Viljoenskroon, sunflower seed, 2020, C.M. Visagie | — | ON164590 | ON164631 | ON164540 | |

| IBT 12659 | USA, New Mexico, Seviletta National Wildlife Refuge, Socorro County, soil in a kangaroo rat burrow, 1989, L. Hawkins | ON156393 | ON164557 | ON164606 | ON164504 | |

| CCF 4914 = IFM 66793 = EMSL 2182 | USA, Arizona, Tucson, air in a hospital, 2013, Ž. Jurjević | ON156392 | ON164556 | ON164605 | ON164503 | |

| A. pragensis | CCF 3962T = CBS 135591T = IBT 32274T = NRRL 62491T | Czech Republic, Prague, toenail of 58-year-old man, 2007, M. Skoøepová | FR727138 | HE661604 | FR751452 | LN849445 |

| CCF 4654 = IBT 32701 | Czech Republic, Prague, toenail of 59-year-old man, 2013, P. Lysková | HG915888 | HG916673 | HG916680 | LT627014 | |

| CCF 5847 = EMSL 2216 | USA, Pennsylvania, Feasterville, carpet in bedroom, 2013, Ž. Jurjević | LT908112 | LT908040 | LT908041 | LT908042 | |

| NRRL 58614 = CCF 4911 = EMSL 1057 | USA, Pennsylvania, indoor air of a home, 2008, Ž. Jurjević | LT908111 | LT908037 | LT908038 | LT908039 | |

| CCF 5693 EMSL 2397 | USA, Maryland, Cohasset, outdoor air, 2014, Ž. Jurjević | LT908113 | LT908043 | LT908044 | LT908045 | |

| CMW-IA 13 = CMW 58615 = CN138F5 = KAS 6296 | Canada, Nova Scotia, Little Lepreau, house dust, 2015, C.M. Visagie & A. Walker | — | ON164553 | ON164602 | ON164500 | |

| CMW-IA 14 = CMW 58616 = CN138G6 = KAS 6138 | Canada, Nova Scotia, Little Lepreau, house dust, 2015, C.M. Visagie & A. Walker | — | ON164554 | ON164603 | ON164501 | |

| CMW-IA 15 = CMW 58617 = CN138G8 = KAS 6299 | Canada, Nova Scotia, Little Lepreau, house dust, 2015, C.M. Visagie & A. Walker | — | ON164555 | ON164604 | ON164502 | |

| A. subalbidus | CBS 567.65T = NRRL 312T = ATCC 16871T = IMI 230752T = CCF 5822T | Brazil, received by K.B. Raper and D.I. Fennell in 1939 from J. Reis (Instituto Biologica) | EF669593 | KP987050 | EF669551 | EF669635 |

| CBS 112449 = DTO 031-E3 = DTO 039-E7 | Germany, indoor environment | LT626956 | EU076294 | EU076307 | LT627015 | |

| NRRL 5214 = ATCC 26930 = IMI 16046 = CCF 4860 | Ghana, vegetable lard, International Mycological Institute, Egham, England, 1933, H.A. Dade (strain GC601) sent to IMI | LT908114 | LT908034 | LT908035 | LT908036 | |

| CCF 5696 =EMSL 2674 | USA, Georgia, Canton, settle plates in living room, 2015, Ž. Jurjević | ON156388 | ON164571 | ON164620 | ON164518 | |

| CCF 6199 = EMSL 2894 | USA, Florida, Bradenton, air in bathroom (settle plates), 2015, Ž. Jurjević | ON156386 | ON164572 | ON164621 | ON164519 | |

| CMW-IA 16 = CMW 58618 = CN162C8 = DN12 | Botswana, Okavango basin, Gcwihaba Caves, bat guano-contaminated soil, 2019, G. Modise, D. Nkwe & R. Mazebedi | — | ON164573 | MW480718 | ON164520 | |

| CMW-IA 17 = CMW 58619 = CN162C9 = DN13 | Botswana, Okavango basin, Gcwihaba Caves, bat guano-contaminated soil, 2019, G. Modise, D. Nkwe & R. Mazebedi | — | ON164574 | MW480719 | ON164521 | |

| CMW-IA 18 = CMW 58620 = CN162D1 = DN62 | Botswana, Okavango basin, Gcwihaba Caves, bat guano-contaminated soil, 2019, G. Modise, D. Nkwe & R. Mazebedi | — | ON164575 | MW480764 | ON164522 | |

| CMW-IA 19 = CMW 58621 = CN162D2 = DN67 | Botswana, Okavango basin, Gcwihaba Caves, bat guano-contaminated soil, 2019, G. Modise, D. Nkwe & R. Mazebedi | — | ON164576 | MW480769 | ON164523 | |

| CMW-IA 20 = CMW 58622 = CN162D3 = DN68 | Botswana, Okavango basin, Gcwihaba Caves, bat guano-contaminated soil, 2019, G. Modise, D. Nkwe & R. Mazebedi | — | ON164577 | MW480770 | ON164524 | |

| CN162D4 = DN69 | Botswana, Okavango basin, Gcwihaba Caves, bat guano-contaminated soil, 2019, G. Modise, D. Nkwe & R. Mazebedi | — | ON164578 | MW480771 | ON164525 | |

| CN162D5 = DN75 | Botswana, Okavango basin, Gcwihaba Caves, bat guano-contaminated soil, 2019, G. Modise, D. Nkwe & R. Mazebedi | — | ON164579 | MW480777 | ON164526 | |

| CN162D6 = DN80 | Botswana, Okavango basin, Gcwihaba Caves, bat guano-contaminated soil, 2019, G. Modise, D. Nkwe & R. Mazebedi | — | ON164580 | MW480781 | ON164527 | |

| CN162D7 = DN82 | Botswana, Okavango basin, Gcwihaba Caves, bat guano-contaminated soil, 2019, G. Modise, D. Nkwe & R. Mazebedi | — | ON164581 | MW480783 | ON164528 | |

| CN162D8 = DN85 | Botswana, Okavango basin, Gcwihaba Caves, bat guano-contaminated soil, 2019, G. Modise, D. Nkwe & R. Mazebedi | — | ON164582 | MW480785 | ON164529 | |

| CCF 5642 = IFM 66794 = EMSL 410 | USA, Connecticut, wall in a house, 2008, Ž. Jurjević | ON156377 | ON164558 | ON164607 | ON164505 | |

| CCF 6197 = IFM 66795 = EMSL 2731 | USA, Illinois, Mokena, air in crawl space (settle plates), 2015, Ž. Jurjević | ON156378 | ON164559 | ON164608 | ON164506 | |

| CCF 5643 = EMSL 2181 | USA, Maryland, Baltimore, carpet in living room, 2013, Ž. Jurjević | ON156380 | ON164561 | ON164610 | ON164508 | |

| NRRL 4809 = ATCC 11380 = IFO 4310 = DTO 213-F7 = CBS 133057 = CCF 5595 | Japan (?), chinese yeast cake, received by K.B. Raper and D.I. Fennell from the Institute for Fermentation, Osaka, Japan (No. 4319) as “A. albus var. 1”, M. Yamazaki, 1946 | EF669609 | EU014092 | EF669567 | EF669651 | |

| NRRL 58123 = CCF 6193 = IFM 66796 = EMSL 465 | USA, California, wall in a house, 2008, Ž. Jurjević | ON156382 | ON164565 | ON164614 | ON164512 | |

| CCF 5697 = IFM 66797 = EMSL 2180 | USA, New Jersey, Mont Clair, indoor air, 2013, Ž. Jurjević | ON156381 | ON164562 | ON164611 | ON164509 | |

| CCF 4913 = EMSL 2297 | USA, Maryland, Baltimore, house dust (living room), 2014, Ž. Jurjević | ON156379 | ON164560 | ON164609 | ON164507 | |

| CCF 5698 = EMSL 2369 | USA, Maryland, Baltimore, house dust (living room), 2014, Ž. Jurjević | ON156385 | ON164563 | ON164612 | ON164510 | |

| CCF 5848 = EMSL 2646 | USA, California, Rancho Mirage, settle plates in living room, 2014, Ž. Jurjević | ON156387 | ON164564 | ON164613 | ON164511 | |

| CCF 6205 = EMSL 3325 | USA, Texas, Harker Heights, air in basement (settle plates), 2015, Ž. Jurjević | ON156383 | ON164566 | ON164615 | ON164513 | |

| FMR 15733 = CBS 142983 = CCF 6052 = IFM 66798 | Spain, Canary Islands, Gran Canaria, Santa Brígida, herbivore dung, 2016, J. Gené & J.Z. Siqueira | LT798905 | LT798924 | LT798925 | LT798926 | |

| FMR 15736 = CBS 142982 = CCF 6074 | Spain, Canary Islands, Gran Canaria, Teror, herbivore dung, 2016, J. Gené & J.Z. Siqueira | LT798906 | LT798927 | LT798928 | LT798929 | |

| FMR 15877 = CBS 142667 = CCF 6058 | Spain, Canary Islands, Gran Canaria, North Coast, herbivore dung, 2016, J. Gené & J.Z. Siqueira | LT798907 | LT798930 | LT798931 | LT798932 | |

| DTO 196-E4 = CBS 126836 | Ecuador, Galapagos Islands, soil, 1965, D.P. Mahoney | ON156384 | ON164583 | ON164622 | ON164530 | |

| A. taichungensis | IBT 19404T = CCF 5597T= DTO 031-C6T | Taiwan, Taichung city, soil, 1994, T. Yaguchi | LT626957 | EU076297 | HG916679 | LT627016 |

| CMW-IA 21 = CMW 58623 = CN162D9 = DN07 | Botswana, Okavango basin, Gcwihaba Caves, bat guano-contaminated soil, 2019, G. Modise, D. Nkwe & R. Mazebedi | — | — | MW480714 | ON164531 | |

| DTO 266-G2 = CCF 5827 = IFM 66799 | Mexico, house dust, 2013, C.M. Visagie | KJ775572 | KJ866980 | ON164627 | ON164536 | |

| DTO 270-C9 = CCF 5826 | Mexico, house dust, 2013, C.M. Visagie | KJ775573 | KJ866981 | ON164626 | ON164535 | |

| A. tenebricus | DTO 337-H7T = CBS 147048T | South Africa, Robben island, soil, 2015, P.W. Crous & M. Meijer | ON156389 | ON164584 | ON164623 | ON164532 |

| DTO 440-E1 = CBS 147376 | Australia, Queensland, soil, 2009, P.W. Crous, N. Yilmaz & T. Hoogenhuijzen | ON156390 | ON164585 | ON164624 | ON164533 | |

| DTO 440-E2 | Australia, Queensland, soil, 2009, P.W. Crous & T. Hoogenhuijzen | ON156391 | ON164586 | ON164625 | ON164534 | |

| Aspergillus sp. | DTO 244-F1 | New Zealand, indoor environment, E. Whitfield, K. Mwange & T. Atkinson | ON156399 | ON164543 | ON164593 | ON164490 |

a Acronyms of culture collections in alphabetic order: ATCC, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Virginia; CBS, Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute (formerly Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures), Utrecht, the Netherlands; CCF, Culture Collection of Fungi, Department of Botany, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic; CMF ISB, Collection of Microscopic Fungi of the Institute of Soil Biology, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, České Budějovice, Czech Republic; CN, CMW & CMW-IA, working and formal culture collections housed at FABI (Forestry and Agricultural Biotechnology) Institute, University of Pretoria, South Africa; DN, working collection of David Nkwe, housed at the Department of Biological Sciences and Biotechnology, Botswana International University of Science and Technology, Botswana; DTO, Internal Culture Collection of The Department Applied and Industrial Mycology of the CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre, Utrecht, The Netherlands; EMSL, EMSL Analytical Inc., New Jersey, USA; FMR, Facultat de Medicina i Ciències de la Salut, Reus, Spain; FRR, Food Fungal Culture Collection, North Ryde, Australia; IBT, Culture Collection at Department of Biotechnology and Biomedicine, Lyngby, Denmark; IFM, Collection at the Medical Mycology Research Center, Chiba University, Japan; IFO, Institute for Fermentation, Osaka, Japan; IHEM (BCCM/IHEM), Belgian Coordinated Collections of Micro-organisms, Fungi Collection: Human and Animal Health, Sciensano, Brussels, Belgium; IMI, CABI’s collection of fungi and bacteria, Egham, UK; KAS, fungal collection of Keith A. Seifert, internal working culture collection at DAOMC (Culture collection of the National Mycological Collections, Agriculture & Agri-Food Canada), Ottawa, Canada; NRRL, Agricultural Research Service Culture Collection, Peoria, Illinois, USA; RMF, Rocky Mountain Fungi, Dept. of Botany, University of Wyoming, Laramie; UAMH, University of Alberta Microfungus collection and Herbarium, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

Phenotypic studies

Macromorphological characters were studied on malt extract agar (MEA; malt extract from Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, UK), Czapek Yeast Extract Agar (CYA; yeast extract from Oxoid Ltd.), Czapek-Dox Agar (CZA), and Czapek Yeast Extract Agar with 20 % sucrose (CY20S). For the agar media composition, see Samson et al. (2014). The strains were inoculated in three points on growth media in 90 mm Petri dishes and colony dimensions were measured after seven and 14 d of incubation at 25 °C. After 14 d, the photographs of colonies were taken, and after 28 d, the colonies were checked for presence of sclerotia and soluble pigment production as these characters are frequently expressed with delay. To determine the cardinal temperatures, the strains were grown for 14 d on MEA at 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 37, 40, and 45 °C. The description and names of colours followed Kornerup & Wanscher (1967). Colony details were documented with a Canon EOS 500D camera and a Leica M205C stereo microscope with a Leica DMC 5400 digital camera.

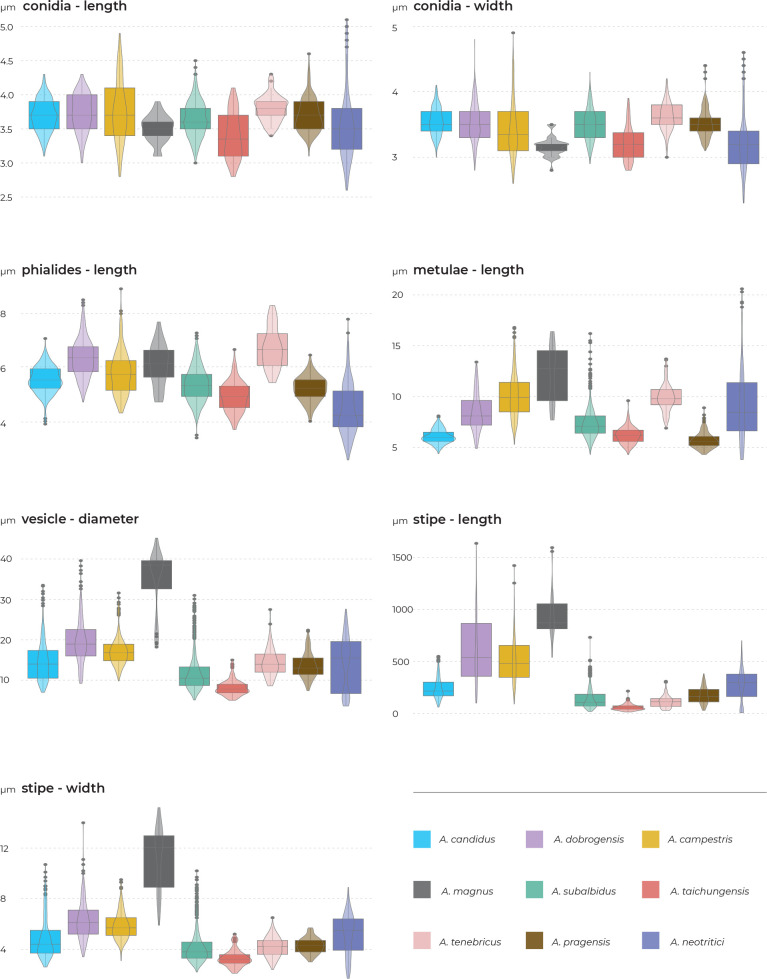

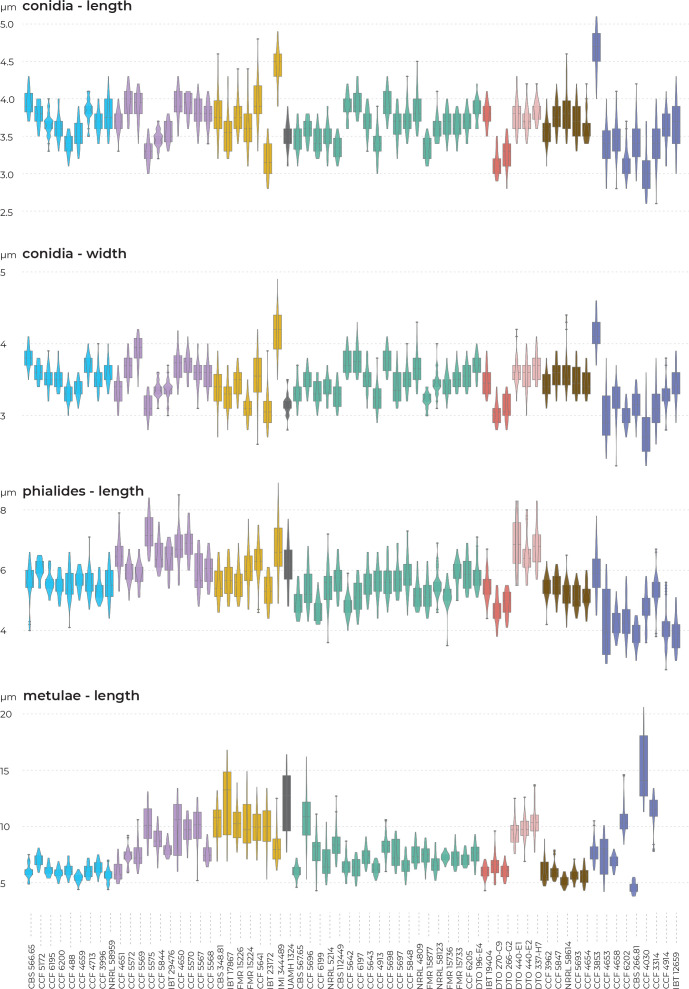

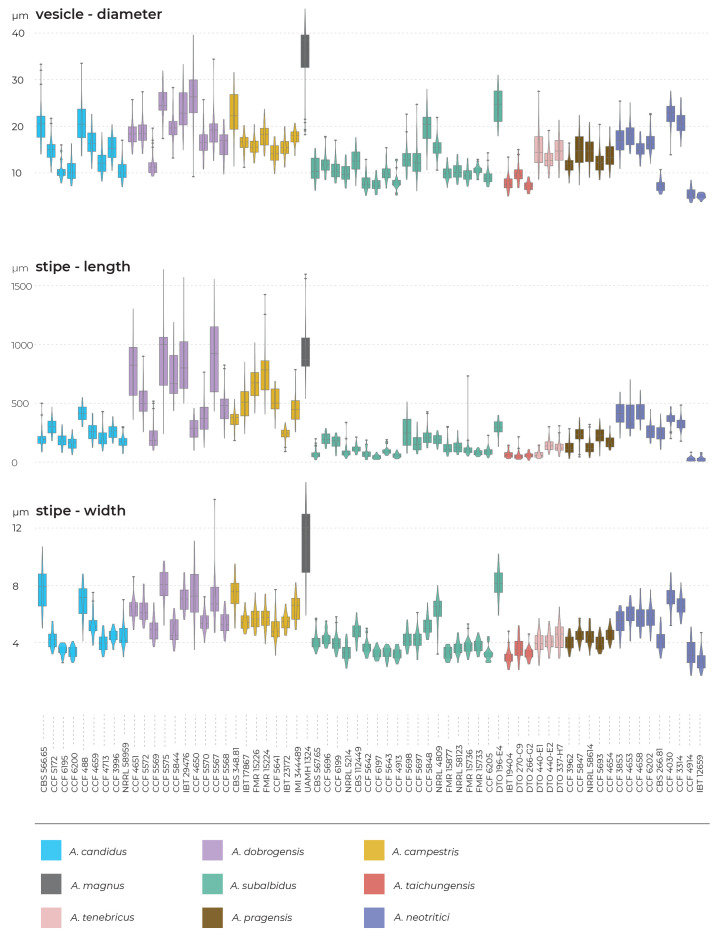

Micromorphological characters (length and width of stipe, vesicle diameter, length of metulae and phialides, length and width of conidia) were photographed and measured from 7–21-d-old colonies on MEA incubated at 25 °C. Lactic acid (60%) was used as mounting medium. Every morphological character was recorded at least 35 times for each strain. Statistical differences, in particular phenotypic characters, were tested with one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s honest significant difference (HSD) test in R v. 4.1.2 (R Core Team 2021). Boxplots and violin graphs were created in R with package ggplot2 (Wickham 2016).

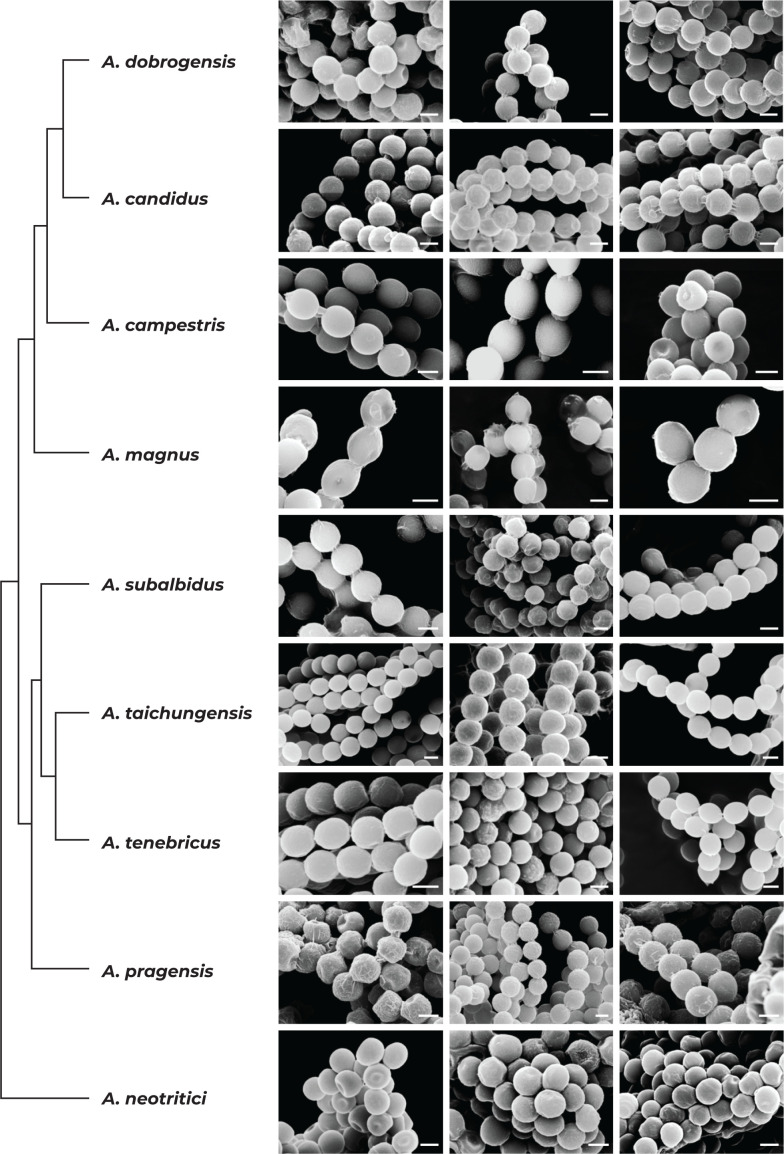

Microscopic photographs were taken using an Olympus BX51 microscope equipped with an Olympus DP72 camera. The photographic plates were made in CorelDRAW Graphic Suite 2021. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was performed using a JEOL-6380 LV microscope (JEOL Ltd. Tokyo, Japan) as described previously by Hubka et al. (2013b).

Molecular studies

Total genomic DNA was extracted from 7-d-old colonies growing on MEA using the ZR Fungal/ Bacterial DNA Kit™ (Zymo Research, Irvin, CA, USA). The quality of the isolated DNA was verified using a NanoDrop 1000 Spectrophotometer.

The PCR reaction volume of 20 μL contained 1 μL (50 ng mL-1) of DNA, 0.3 μL of both primers (25 pM mL-1), 0.2 μL of MyTaqTM DNA Polymerase (Bioline, GmbH, Germany) and 4 μl of 5 × MyTaq PCR buffer. The standard thermal cycle profile was 93 °C—2 min; 38 cycles of 93 °C—30 s, 55 °C—30 s, 72 °C—60 s; and a final extension of 72 °C—10 min. The internal transcribed spacer rDNA region (ITS) was amplified using forward primer ITS1 (White et al. 1990) and reverse primers NL4 (O’Donnell 1993) or ITS4 (White et al. 1990); the partial β-tubulin gene region (benA) was amplified using forward primers Bt2a (Glass & Donaldson 1995), T10 (O’Donnell & Cigelnik 1997) or Ben2f (Hubka & Kolařík 2012) and reverse primer Bt2b (Glass & Donaldson 1995); the partial calmodulin gene region (CaM) was amplified using forward primers CF1L, CF1M (Peterson 2008) or cmd5 (Hong et al. 2006) and reverse primers CF4 (Peterson 2008) or cmd6 (Hong et al. 2006); and the partial RNA polymerase II second largest subunit gene region (RPB2) using forward primers fRPB2-5F (Liu et al. 1999) or RPB2-F50-CanAre (Jurjević et al. 2015) and reverse primer fRPB2-7cR (Liu et al. 1999). The PCR products were separated by electrophoresis on 1 % agarose gel and subsequently purified using ExoSAP-IT™ (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Vilnius, Lithuania).

Sequences were inspected and assembled using BioEdit v. 7.2.5 (Hall 1999) and deposited into the GenBank database under accession numbers listed in Table 1.

Phylogenetic studies

Alignments of the benA, CaM and RPB2 loci were performed using the FFT-NS-i option implemented in the MAFFT online service (Katoh et al. 2019). ITS was excluded from analyses due to its low number of informative sites. The alignments were trimmed, concatenated and then analysed using maximum likelihood (ML), Bayesian inference (BI) and Maximum Parsimony (MP; this method was used only to construct single-gene phylogenies) methods. Suitable partitioning schemes and substitution models (Bayesian information criterion) for the analyses were selected using a greedy strategy implemented in PartitionFinder 2 (Lanfear et al. 2017) with settings allowing introns, exons and codon positions to be independent datasets. The optimal partitioning schemes for each analysed dataset along with basic alignment characteristics are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of alignments, partition-merging results and best substitution model for each partition according to the Bayesian information criterion.

| Alignment | Length (bp) | Variable position | Parsimony informative sites | Phylogenetic method | Partitioning scheme (substitution model) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| benA + CaM + RPB2 (Fig. 1) | 2069 | 455 | 353 | Maximum likelihood (ML) | Five partitions: 1st codon positions of benA, CaM & RPB2 & 2nd codon positions of CaM (TrN+I); 2nd codon positions of benA & RPB2 (JC); 3rd codon positions of benA & CaM (HKY+G); 3rd codon positions of RPB2 (K81uf+G); introns of benA & CaM (K80+G) |

| Bayesian inference (BI) | Five partitions: 1st codon positions of benA, CaM & RPB2 (HKY+I); 2nd codon positions of benA, CaM & RPB2 (F81+I); 3rd codon positions of benA & CaM (HKY+G); 3rd codon positions of RPB2 (HKY+G); introns of benA & CaM (K80+G) | ||||

| benA (Fig. 2) | 479 | 133 | 106 | ML | Three partitions: 1st & 2nd codon positions (JC); 3rd codon positions (HKY+G); introns (K80+G) |

| BI | Three partitions: 1st & 2nd codon positions (JC); 3rd codon positions (HKY+G); introns (K80+G) | ||||

| CaM (Fig. 2) | 576 | 120 | 88 | ML | Three partitions: 1st & 2nd codon positions (TrN+I); 3rd codon positions (HKY+G); introns (K80+G) |

| BI | Three partitions: 1st & 2nd codon positions (HKY+I); 3rd codon positions (HKY+G); introns (K80+G) | ||||

| RPB2 (Fig. 2) | 1014 | 202 | 159 | ML | Three partitions: 1st codon positions (HKY+I); 2nd codon positions (JC); 3rd codon positions (K81uf+G) |

| BI | Three partitions: 1st codon positions (HKY+I); 2nd codon positions (JC); 3rd codon positions (HKY+G) |

Maximum likelihood trees were constructed with IQ-TREE v. 1.4.4 (Nguyen et al. 2015) with nodal support determined by ultrafast bootstrapping (BS) with 100 000 replicates. Trees were rooted with the clade containing A. neotritici isolates. Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP) were calculated using MrBayes v. 3.2.6 (Ronquist et al. 2012). The analysis ran for 107 generations, two parallel runs with four chains each were used, every 1 000th tree was retained and the first 25 % of trees were discarded as burn-in. The convergence of the runs and effective sample sizes were checked in Tracer v. 1.6 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/tracer). Maximum parsimony (MP) trees were created using PAUP* v.4.0b10 (Swofford 2003). Analyses were performed using the heuristic search option with 100 random taxon additions; tree bisection-reconnection (TBR); maxtrees were set to 1 000. Branch support was assessed by bootstrapping with 500 replications.

The rules for the application of the GCPSR approach were adopted from Dettman et al. (2003a,b) and slightly modified to different design of this study (different number of loci and methods used). To recognize a clade as an evolutionary lineage, it had to satisfy either of two criteria: (a) genealogical concordance - the clade was present in the majority (2/3) of the single-locus genealogies; (b) genealogical nondiscordance - the clade was well supported in at least one single-locus genealogy, as judged by both ML and MP bootstrap proportions (≥70 %) and BI posterior probabilities (≥95 %), and was not contradicted in any other single-locus genealogy at the same level of support. When deciding which evolutionary lineages represent phylogenetic species, two additional criteria were applied and evaluated according to the combined phylogeny of three genes: (a) genetic differentiation - species had to be relatively distinct and well differentiated from other species to prevent minor tip clades from being recognized as a separate species; (b) all individuals had to be placed within a phylogenetic species, and no individuals were to be left unclassified.

In order to create hypotheses about species boundaries, we used one multi-locus multispecies coalescent (MSC) model-based method STACEY (Jones 2017) and four single-locus species MSC delimitation methods: (1) the general mixed Yule-coalescent method (GMYC) (Fujisawa & Barraclough 2013), (2) the Bayesian version of the general mixed yule-coalescent model (bGMYC) (Reid & Carstens 2012), (3) the Poisson tree processes model (PTP) and (4) the Bayesian Poisson tree processes model bPTP (Zhang et al. 2013).

For the single-locus species delimitation methods, we used the haplotype function from package pegas (Paradis 2010) in R to retain only unique sequences in alignments. The following nucleotide substitution models were selected by jModelTest v. 2.1.10 (Darriba et al. 2012) for benA, CaM and RPB2 loci according to the Bayesian information criterion: K80+I, TrNef+G and TrN+I. The GMYC analysis was performed in R with the package splits (Fujisawa & Barraclough 2013). The ultrametric input trees for the GMYC method were calculated in BEAST v. 2.6.6 (Bouckaert et al. 2014) with a chain length of 1 × 107 generations. As a model for creating input trees we set up Coalescent Constant Population prior and performed two tree reconstruction methods – one with Common Ancestor heights (CAh) setting and second with Median heights (Mh) setting. We only show delimitation results of both settings when they were different. The bGMYC analysis was performed with package bgmyc (Reid & Carstens 2012) in R v. 3.4.1. For this method, we firstly discarded the initial 25 % of the trees from the BEAST inference as burn-in and then we used R v. 4.1.2 the package ape (Paradis et al. 2004) in R to randomly select one hundred trees, which were then used as input. Two values (0.5 and 0.75) of bgmyc.point function were set up for all analyses. This function is crucial for the final division of strains into species. The authors of the software recommended value around 0.5, lower value delimits either the same number of species or less while a value >0.5 delimits the same number of species or more. For the PTP and bPTP method, 1 000 maximum likelihood standard bootstrap trees were calculated in IQ-TREE v. 1.6.12 (Nguyen et al. 2015) and used as input. The analysis was run in the Python v. 3 (van Rossum & Drake 2019) package ptp (Zhang et al. 2013).

The multi-locus species delimitation method STACEY was performed in BEAST v. 2.6.6 (Bouckaert et al. 2014) using the STACEY v. 1.2.5 add-on (Jones 2017). We set up the length of mcmc chain to 1 × 109 generations, the species tree prior was set to the Yule model, the molecular clock model was set to strict clock, growth rate prior was set to lognormal distribution (M = 5, S = 2), clock rate priors for all loci were set to lognormal distribution (M = 0, S = 1), PopPriorScale prior was set to lognormal distribution (M = -7, S = 2) and relativeDeathRate prior was set to beta distribution (α = 1, β = 1000). The output was processed with SpeciesDelimitationAnalyzer (Jones 2015). For the presentation of the results of STACEY, we firstly created a plot showing how the number of delimited species and the probability of the most probable scenarios change in relation to the value of collapseheight parameter, and then we created similarity matrices using code from Jones et al. (2015) with two different values (0.007, 0.01) of collapseheight chosen from the plot (see Results section - Species delimitation using STACEY). Phylogenetic trees generated during STACEY analysis were then used for the presentation of species delimitation results analysis. The graphical outputs were created in iTOL (Interactive Tree Of Life) (Letunic & Bork 2021).

We also employed the recently developed software DELINEATE (Sukumaran et al. 2021) to independently test species boundaries hypotheses. Firstly, the dataset was split into hypothetical populations with “A10” analysis in BPP v. 4.3 (Yang 2015). Then, the species tree for these populations was estimated in starBEAST (Heled & Drummond 2009) implemented in BEAST v. 2.6.6 (Bouckaert et al. 2014). Finally, the populations delimited by BPP were lumped into species based on the results of species delimitation methods and phenotypic characters, with several populations always left unassigned to be delimited by DELINEATE. In total, nine models of species boundaries were set up. The analysis was run in Python v. 3 (van Rossum & Drake 2019) package delineate (Sukumaran et al. 2021).

RESULTS

Integrative approach for determining species boundaries

For the species delimitation in section Candidi, three genetic loci (benA, CaM and RPB2) were examined across 113 strains, while phenotypic characters were measured and scored for 66 strains representing the genetic variability across the section. The results from the GCPSR approach were compared with MSC methods and phenotypic data to draw the final conclusions about species limits.

From the early beginning of this study, it was clear that creating initial hypotheses about species boundaries in section Candidi would be extremely difficult due to relatively uniform morphology and conflicting data from single-gene phylogenies. To overcome these difficulties and remain relatively consistent across the section, we decided to score support for delimitation of species and monitor four main criteria. In this integrative approach, we required that the delimited species meet at least three of the following four criteria: (1) no conflict in the assessment of species limits using the GCPSR approach, (2) support from the multi-locus MSC method STACEY (at least in one of the two most probable scenarios – see below), (3) support by the majority (10 from 18) of single-locus MSC methods and their settings (agreement on the delimitation of species in its exact form or delimitation of smaller entities within it but without any admixture with related species/populations) and (4) presence of phenotypic difference(s) from phylogenetically most closely related species. The resulting scoring is summarized in Table 3. Using this approach, delimitation of two novel species was supported, A. magnus and A. tenebricus (see below and section Taxonomy).

Table 3.

Support for delimitation of various species/populations using integrative approach consisting of four main components.

| Examined species/populations |

Support from four evaluated components

|

Overall support (3–4/4) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GCPSR | STACEY1 | Single-locus MSC methods2 | Morphology / physiology | ||

| A. campestris | NO | YES (2/2) | YES (12/18) | YES | YES |

| segregation of A. campestris into three species | NO3 | NO (0/2) | NO (6/18) | NO | NO |

| A. candidus | YES | YES (1/2) | NO (7/18) | N/A (trend) | ? |

| A. dobrogensis | YES | YES (1/2) | NO (7/18) | N/A (trend) | ? |

| Aspergillus sp. DTO 244-F1 | N/A | YES (2/2) | YES (11/18) | N/A | ? |

| A. magnus | N/A | YES (2/2) | YES (17/18) | YES | YES |

| A. neotritici | YES | YES (2/2) | YES (18/18) | YES | YES |

| segregation of CCF 4914 and IBT 12659 from A. neotritici | YES | NO (0/2) | NO (3/18) | YES | NO |

| A. pragensis | YES | YES (2/2) | YES (17/18) | YES | YES |

| A. subalbidus | YES | YES (1/2) | YES (17/18) | YES | YES |

| segregation of CCF 6199 and CCF 5642 (pop 6) from A. subalbidus | YES | YES (1/2) | NO (9/18) | NO | NO |

| A. taichungensis | YES | YES (2/2) | YES (13/18) | YES | YES |

| segregation of DTO 266-G2 from A. taichungensis | NO | NO (0/2) | YES (10/18) | NO | NO |

| A. tenebricus | YES | YES (2/2) | YES (13/18) | YES | YES |

MCS – multispecies coalescent model-based methods; N/A – data not available or analysis could not be performed (non-viable strain DTO 244-F1 could not be analyzed phenotypically; species/populations represented by one strains could not be evaluated using GCPSR; a part of A. dobrogensis and A. candidus isolates cannot be distinguished morphologically – see sections Results, Discussion and Taxonomy).

1Support in at least one of the two most probable scenarios with collapseheight parameters 0.007 and 0.01 – see Fig. 4B.

2Support by the majority (at least 10 out of 18) of single-locus methods and their settings, i.e., agreement on the delimitation of species in its exact form or delimitation of smaller entities within it but without any admixture with related species/populations – see Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic analysis and GCPSR approach

The best scoring ML tree based on the concatenated and partitioned alignment of 113 strains is shown in Fig. 1. The topology of the tree inferred by BI was almost identical and the posterior probabilities are appended to nodes together with bootstrap support values from ML analysis. Isolation source and geographical origin of strains are plotted on the tree (also listed in Table 1) together with the culture collection accession numbers. All alignments are available from the Dryad Digital Repository (https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.3j9kd51mq) and basic alignment characteristics are listed in Table 2 together with partitioning scheme and substitution models used in the analyses.

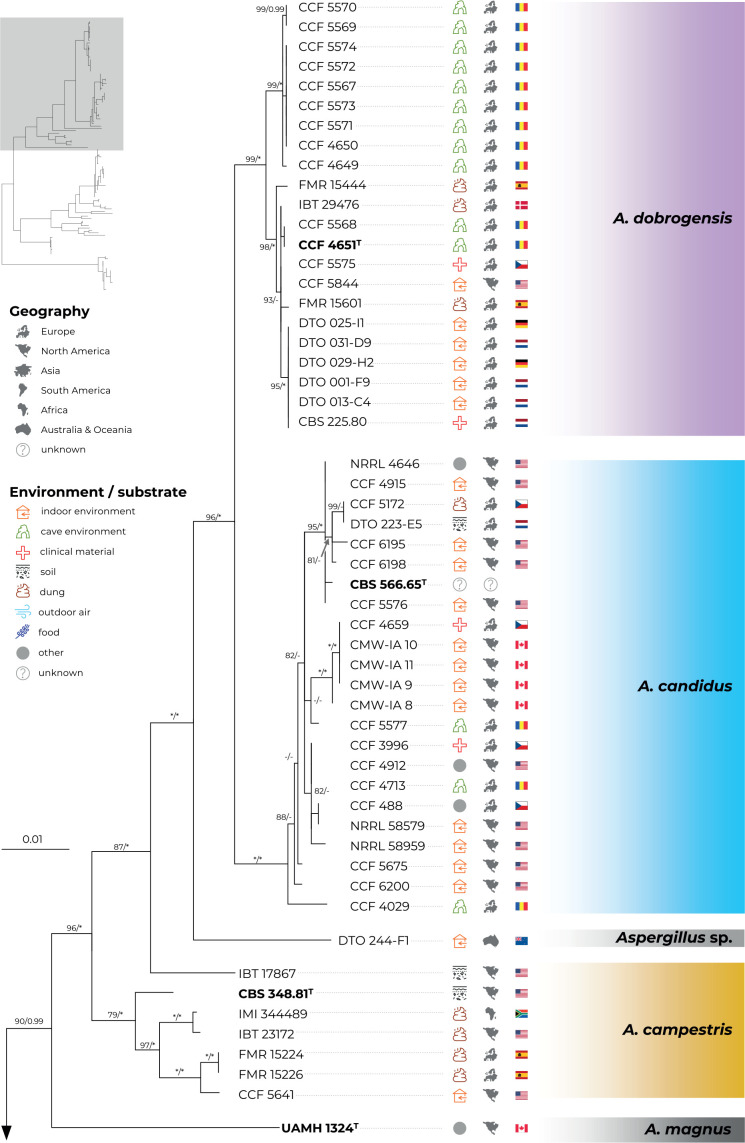

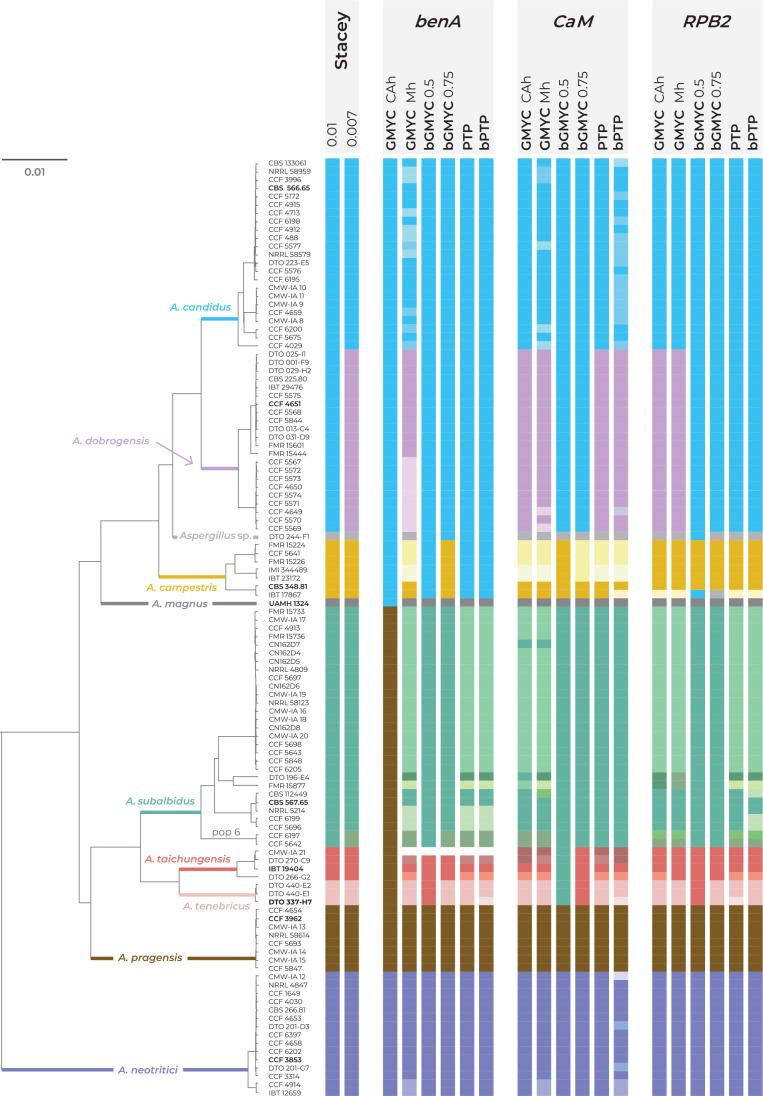

Fig. 1.

Multi-locus phylogeny of Aspergillus section Candidi based on three loci (benA, CaM, RPB2) and comprising 113 isolates. Best scoring Maximum Likelihood tree inferred in the IQ-TREE is shown; Maximum likelihood bootstrap values and Bayesian posterior probabilities are appended to nodes; only support values higher than 70 % and 0.95, respectively, are shown. The ex-type strains are designated with a superscripted T and bold print. Alignment characteristics, partitioning scheme and substitution models are listed in Table 2. The information on geographic origin and isolation source was plotted on the tree – see legend.

Phylogenetic relationships between section Candidi members are well resolved in the combined phylogeny and the species clustered into three main monophyletic clades. The first clade included A. candidus, A. dobrogensis, Aspergillus sp. DTO 244-F1, A. campestris and A. magnus. Although it is highly probable that strain DTO 244-F1 represents an undescribed species according to this phylogeny and molecular analyses mentioned below, it is no longer viable and thus only molecular data could be analysed. The second clade comprised A. subalbidus, A. taichungensis, A. tenebricus and A. pragensis. Aspergillus neotritici formed a single-species lineage, relatively distant from the other species. This topology was almost identical to the trees generated in STACEY analysis and starBEAST with one notable exception. In the ML and BI trees, A. campestris was resolved as polyphyletic due to the position of the strain IBT 17867. This strain formed a single-strain lineage clustering with Aspergillus sp. DTO 244-F1, A. candidus and A. dobrogensis. This is caused by its atypical RPB2 sequences influencing the topology not only of the RPB2 tree (Fig. 2) but also of the whole multi-locus phylogeny (Fig. 1). The RPB2 sequence of A. campestris IBT 17867 shares many variable positions with A. candidus and A. dobrogensis and probably represents a phenomenon of ancestral polymorphism/incomplete lineage sorting or could be caused by past recombination/hybridization. By contrast, in the tree from the multi-locus MSC method STACEY (Fig. 3) and starBEAST (see Delineate analysis), all seven strains of A. campestris formed a monophyletic clade. Other sequences and phenotypic characters of IBT 17867 were typical of A. campestris.

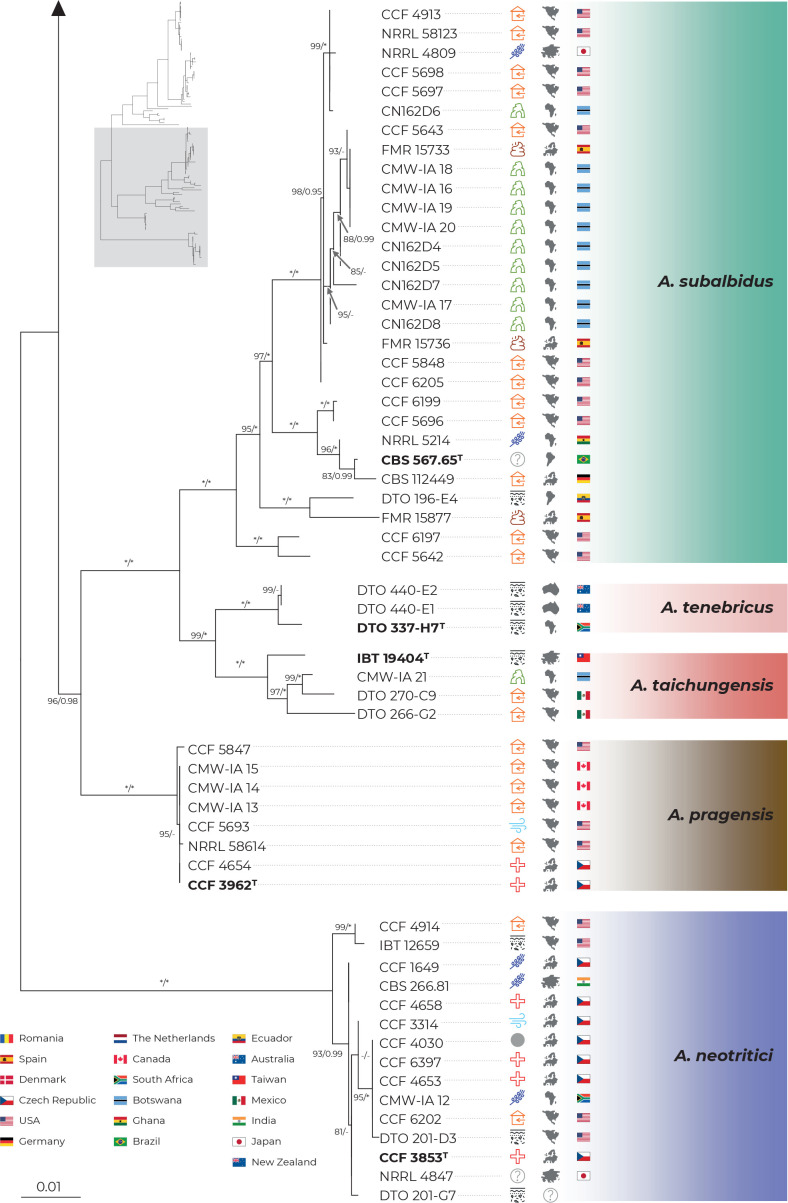

Fig. 2.

Comparison of single-gene genealogies based on the alignments of benA, CaM and RPB2 loci and created by three different phylogenetic methods. Single-locus maximum likelihood trees are shown; maximum likelihood bootstrap supports (MLBS), maximum parsimony bootstrap supports (MPBS) and Bayesian inference posterior probabilities (BIPP) are appended to nodes. Only MLBS and MPBS values ≥70 % and BIPP ≥0.95, respectively, are shown. A cross indicates lower statistical support for a specific node or the absence of a node in the MP and BI phylogenies. Selected strains or strain groups causing incongruences across single-gene phylogenies because of their unstable position are colour highlighted. The ex-type strains are designated with a superscripted T and bold print.

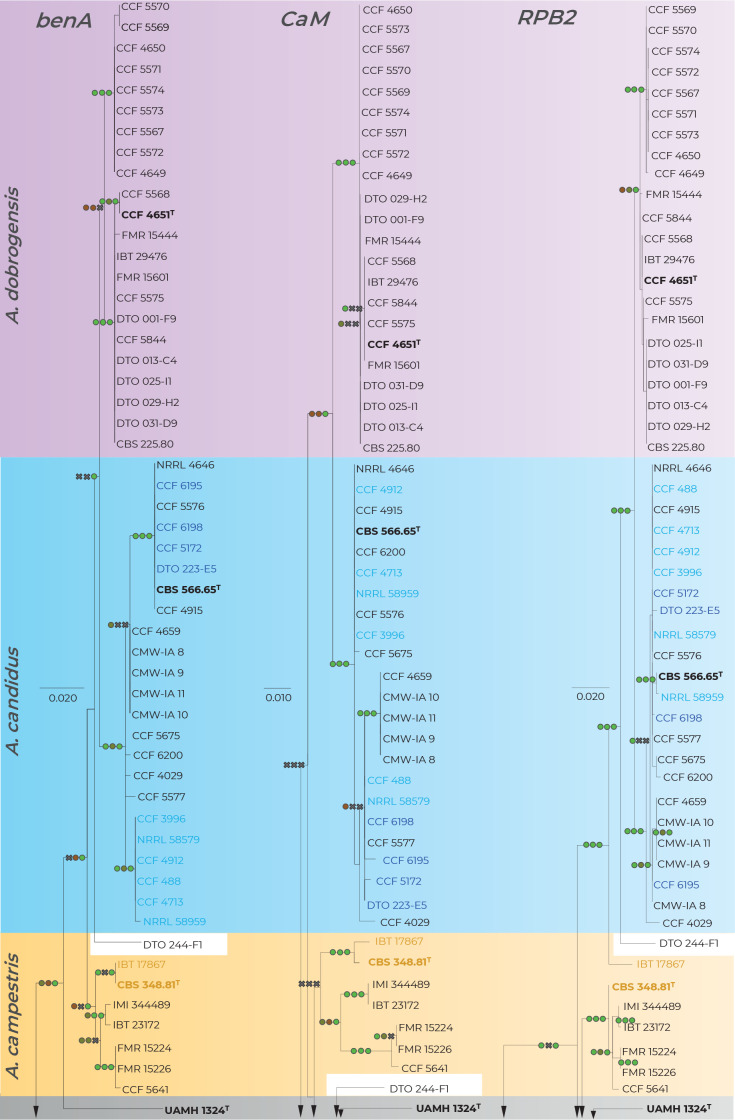

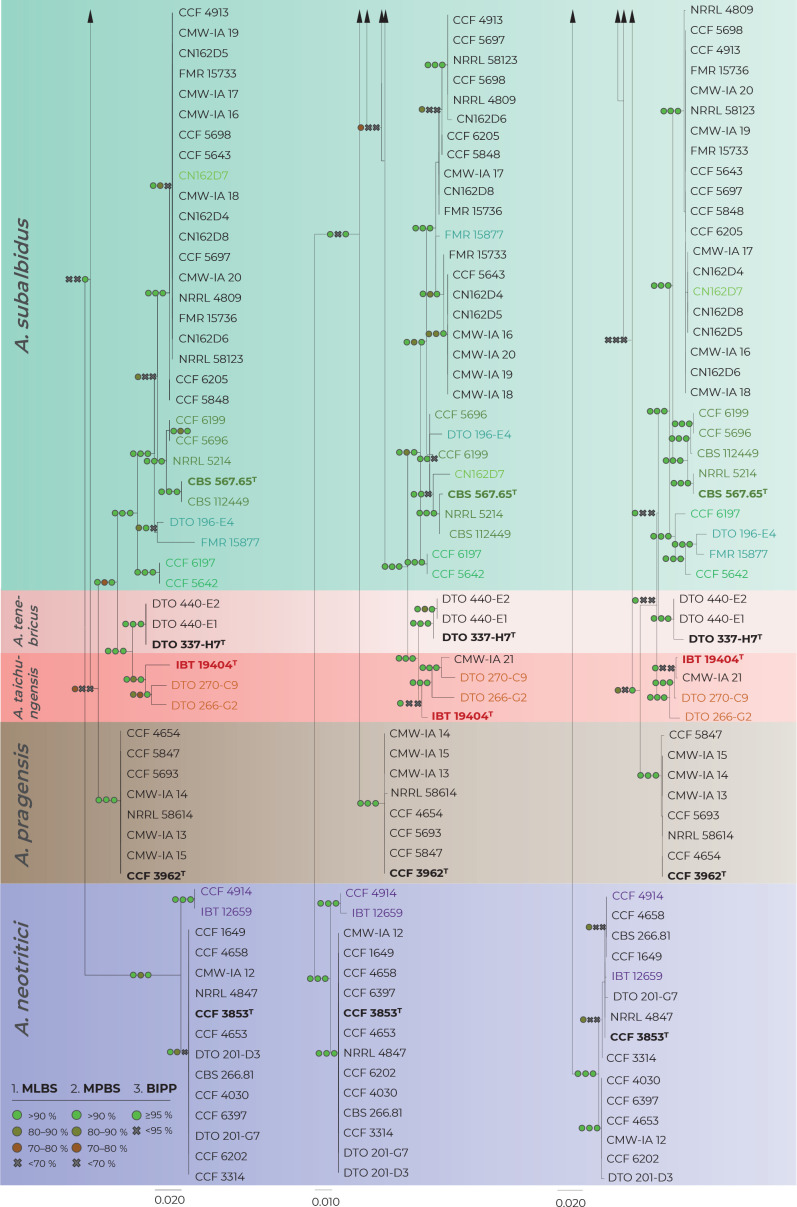

Fig. 3.

Schematic representation of results of species delimitation methods in the section Candidi. One multi-locus method (STACEY) and five single-locus methods (GMYC, bGMYC, PTP, bPTP) were applied on dataset of three loci (benA, CaM, RPB2). The results are depicted by coloured bars with different colours or shades indicating tentative species delimited by specific method and setting. Ex-type isolates of accepted species are highlighted with bold print. STACEY results with two values of collapseheight parameter, 0.01 and 0.007, are shown. For the GMYC method, the Coalescent Constant Population tree model was used as an input with both common ancestor heights (CAh) and Median heights (Mh) settings. For the bGMYC method, values 0.5 and 0.75 were used for the bgmyc.point function. The phylogenetic tree was calculated in starBEAST analysis and it is used solely for the comprehensive presentation of the results from different methods.

When comparing topologies of single-gene trees and applying rules of the GCPSR concept (Fig. 2), no conflicts were found between A. candidus and A. dobrogensis supporting definition of these species in their known limits (Hubka et al. 2018b). There was some exchange of isolates between clades within the A. candidus lineage and we thus consider this species a single phylogenetic species (PS). Three evolutionary lineages are supported among seven examined strains of A. campestris: IBT 17867 + CBS 348.81 (1), IMI 344489 + IBT 23172 (2) and FMR 15224 + FMR 15226 + CCF 5641 (3). Except for lineage 1, these lineages are present in all three single-gene trees without conflict. However, as mentioned above, the deviating RPB2 sequence and phylogenetic position of IBT 17867 in the RPB2 tree contradicts support of lineages 1 in the RPB2 tree. It is difficult to decide if there is a support for three PS using GCPSR because lineage 1 does not occur in the combined phylogeny reconstructed using ML and BI (Fig. 1) but at the same time, it is present in the species trees from other multigene analyses as mentioned above.

Aspergillus pragensis received clear support because this lineage contained little intra-species variation and it is well separated from other species in all phylogenies. The GCPSR approach also clearly supported delimitation of A. tenebricus and its sister species A. taichungensis. There are some incongruences within the A. taichungensis lineage not allowing this species to be defined other than in the form of four strains (IBT 19404, DTO 266-G2, DTO 270-C9 and genetically invariable CMW-IA 21). Significant incongruences can be found in the robust and structured lineage of A. subalbidus. GCPSR approach supports segregation of basal clade with strains CCF 5642 and CCF 6197 (referred to as population “pop 6” according to the DELINEATE analysis – see below) from A. subalbidus. Speciafically, segregation of this PS is supported by benA, CaM and combined phylogenies but not by RPB2 phylogeny (Figs 1–2).

All species belonging to the section Candidi are biseriate, however, within the lineage of A. neotritici, there is a subclade with two uniseriate strains CCF 4914 and IBT 12659 (no biseriate conidiophores observed) which is supported by benA, CaM and combined phylogenies but not by RPB2 (Figs 1–2). Although GCPSR supported segregation of this subclade from A. neotritici, MSC methods preferred a broad concept of A. neotritici (see below).

Singleton lineages with unstable phylogenetic position, namely, Aspergillus sp. DTO 244-F1 and UAMH 1324 (A. magnus), were excluded from evaluation using GCPSR because it is not possible to evaluate potential discordant positions of similar isolates across genealogies. On the other hand, both strains formed their own singleton lineages in all single-gene and multigene trees.

Species delimitation using STACEY

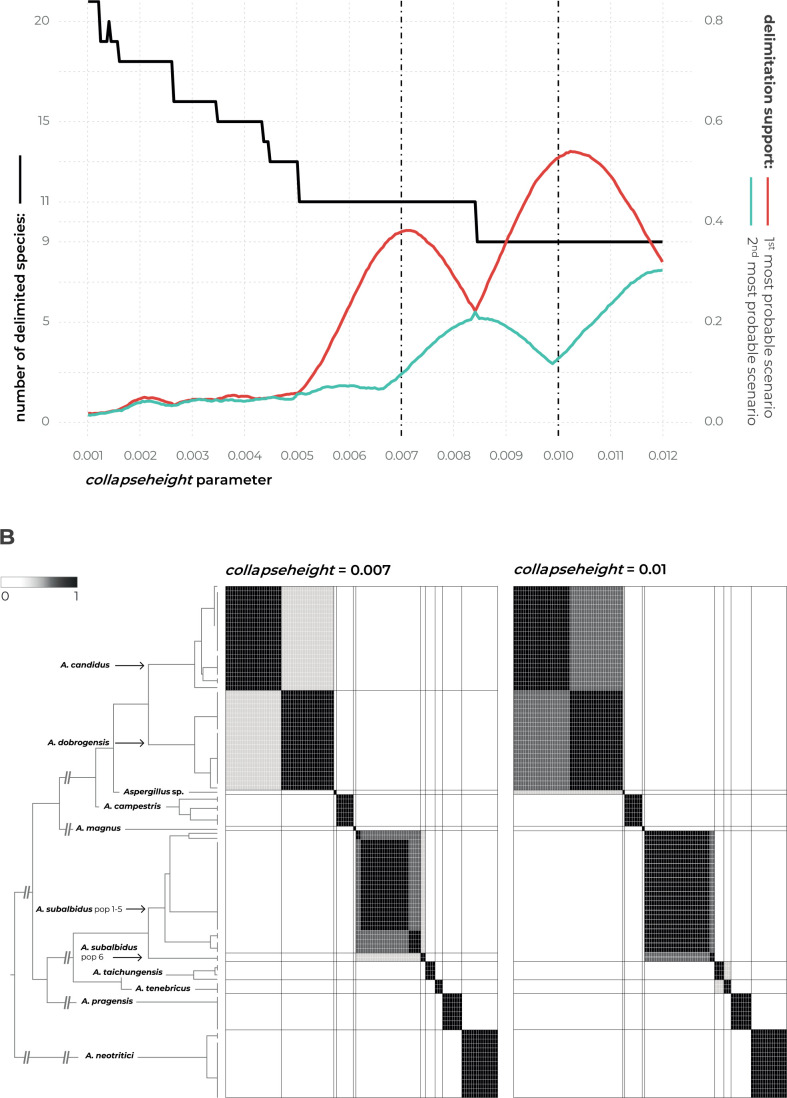

Detailed results of the multi-locus method STACEY are shown in Fig. 4 where subfigure A illustrates the effect of the collapseheight parameter value on the number of delimited species. This collapseheight parameter is plotted on the x-axis while on the left y-axis, there is a number of delimited species with the given collapseheight value (black line). The support for the most probable scenario (red line), and the second most probable scenario (turquoise line) are shown; other less supported scenarios are omitted. The changing value o the collapseheight parameter has consequences especially for the delimitation of A. dobrogensis, A. candidus, and species in the clade containing A. subalbidus, A. taichungensis and A. tenebricus. There are two main scenarios which gained reasonable support, i.e., with 9 and 11 delimited species (Fig. 4A). The vertical dashed lines in subfigure A represent these scenarios illustrated in detail in subfigures B (Fig. 4B) in the form of similarity matrices showing posterior probabilities of each pair of isolates being included in the same species.

Fig. 4.

The results of species delimitation by using STACEY method. A. Dependence of delimitation results on collapseheight parameter. The black solid line represents the number of delimited species (left y-axis) depending on the changing value of collapseheight parameter (x-axis). The red line represents the probability (range from 0 to 1, right y-axis) of the most probable scenario at specific collapseheight value. The turquoise line represents the probability of the second most probable scenario at specific collapseheight value. Dashed vertical lines mark two values (0.007, 0.01) of collapseheight parameter whose results are shown in detail by similarity matrices (subfigure B). B. The similarity matrices give the posterior probability of every two isolates belonging to the same multispecies coalescent cluster (tentative species). The darkest black shade corresponds to a posterior probability of 1, while the white colour is equal to 0. Thicker horizontal and vertical lines in the similarity matrices delimit species or their populations that gained delimitation support in some scenarios.

The scenario with 11 species reached support of approximately 0.4 (y-axis on the right side; maximum is 1) when the collapseheight parameter value is around 0.007. In this scenario, A. dobrogensis, A. candidus, A. taichungensis and A. tenebricus are delimited as separate species. Strains of A. subalbidus are divided into two tentative species – status of the separate species is supported for the clade “pop 6” designated according to the DELINEATE analysis (see below).

In the scenario with 9 species and collapseheight parameter value of approximately 0.01, A. subalbidus is delimited as a single broad species, while A. dobrogensis is merged with A. candidus. Both A. taichungensis and A. tenebricus are still delimited but with lower support. The delimitation support of the other species was stable and with high support in both scenarios (Aspergillus sp. DTO 244-F1, A. campestris, A. magnus, A. pragensis and A. neotritici).

Delimitation using single-locus MSC methods

There was a high overall agreement across single-locus MSC methods and their different settings on the delimitation of A. magnus, A. pragensis and A. neotritici while for the other species, different methods generated a plethora of possible arrangements (Fig. 3). Aspergillus pragensis and A. magnus have been consistently defined from other species by all mentioned methods except the GMYC method with Common Ancestor node heights settings (GMYC CAh) based on benA. In this setting, A. magnus was lumped with A. candidus, A. dobrogensis, A. campestris and Aspergillus sp. DTO 244-F1, while A. pragensis was lumped with A. subalbidus, A. taichungensis and A. tenebricus. Only three analyses delimited one or more additional species within A. neotritici lineage, namely GMYC method with Median node heights setting (GMYC Mh) based on benA and CaM loci, and bPTP method based on CaM locus. All these three analyses agreed on the separation of clade containing uniseriate isolates CCF 4914 and IBT 12659 from A. neotritici. Most of the analyses (12/18) also supported delimitation of singleton species Aspergillus sp. DTO 244-F1 which is related to A. candidus, A. dobrogensis and A. campestris.

The agreement of the methods on the delimitation and arrangement of the remaining species was much lower. The majority of analyses did not support the delimitation of A. dobrogensis from A. candidus (Fig. 3). Only seven analyses distinguished A. candidus and A. dobrogensis or delimited a couple of additional species within these species. Delimitation of A. campestris in its broad concept (seven isolates) was only supported by bGMYC with value 0.5 for the bgmyc.point function (bGMYC 0.5) based on CaM locus and with value 0.75 (bGMYC 0.75) based on benA locus. This broad concept is in agreement with results of STACEY with both collapseheight parameters. Some analyses based on benA locus (PTP, bPTP, GMYC CAh and bGMYC 0.5 methods) lumped A. campestris with A. candidus and A. dobrogensis. All methods based on CaM locus except bGMYC 0.5 and also GMYC Mh based on benA locus delimited 2–4 species within A. campestris. Because the RPB2 sequence of strain IBT 17867 is atypical and relatively dissimilar from other A. campestris isolates, all single-locus methods based on RPB2 failed to connect this strain with A. campestris. This strain was either delimited as a singleton species or it was lumped with Aspergillus sp. DTO 244-F1 (bGMYC 0.75) or with the clade containing A. candidus and A. dobrogensis (bGMYC 0.5).

Aspergillus taichungensis was delimited as a species with four strains (IBT 19404, DTO 270-C9, DTO 266-G2 and CMW-IA 21) by STACEY with both values of the collapseheight parameter. This arrangement was only supported by three single-locus methods, namely, bGMYC 0.75 based on benA and RPB2 and GMYC Mh based on RPB2. The majority of analyses (10/18) delimited 2–4 species within A. taichungensis (Fig. 3). Three analyses merged A. taichungensis with A. tenebricus and two analyses (bGMYC 0.5 based on CaM and GMYC Cah based on benA) even merged these species with A. subalbidus and/or A. pragensis. Similarly to STACEY, most of the analyses (10/18) delimited A. tenebricus as a species comprising three strains: DTO 337-H7, DTO 440-E1 and DTO 440-E2. Three analyses supported segregation into two species and the remaining five analyses merged A. tenebricus with related species as mentioned above. Aspergillus subalbidus was represented by a high number of strains (n = 29) which were structured into several clades and frequently delimited as separate species by single-locus MSC methods. STACEY proposed a broad concept of A. subalbidus with 29 or 27 strains, only supporting segregation of “pop 6” (see DELINEATE analysis below) in the setting with low collapseheight parameter (0.007). This broad concept of A. subalbidus was supported by six out of 18 single-locus MSC analyses and the remaining analyses usually segregated “pop 6” (nine out of 18) and/or delimited several additional species with variable arrangements. Two analyses lumped A. subalbidus with neighbouring species (Fig. 3).

Phenotypic analysis - macromorphology

All species were able to grow on the four cultivation media (MEA, CYA, CZA, CY20S) at 25 °C. Colony diameters on these media and selected macromorphological characters relevant for the species identification are summarized in Table 4. Almost all species have the largest colony diameter on CY20S compared to the other media with a lower sugar content. Aspergillus magnus and A. pragensis had the smallest colony diameters and their restricted growth was even more accentuated on CZA.

Table 4.

Overview of selected macromorphological characters and growth parameters at 25 °C.

| Species (no. of examined strains) |

Colony diameter after 7 d in mm (mean) |

Colony diameter after 14 d in mm (mean) |

Colony colours (CYA and MEA) | Soluble pigment (present : absent)1 | Sclerotia (present : absent)1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEA | CYA | CZA | CY20S | MEA | CYA | CZA | CY20S | ||||

| A. campestris (7) | 11–17 (15) | 14–20 (17) | 6–14 (9) | 10–21 (18) | 16–28 (24) | 22–36 (28) | 10–20 (16) | 25–34 (30) | yellow, sulphur yellow, yellowish white | 7 : 0 (CZA > CYA > CY20S) | 4 : 3 (CZA, CYA) |

| A. candidus (9) | 12–17 (15) | 15–21 (18) | 9–15 (11) | 16–25 (22) | 20–27 (24) | 20–32 (27) | 16–25 (21) | 25–45 (36) | white, white with a yellowish tinge | 5 : 4 (CZA > CYA) | 5 : 4 (CZA) |

| A. dobrogensis (10) | 17–20 (19) | 20–24 (21) | 9–14 (10) | 18–28 (24) | 22–35 (29) | 26–39 (32) | 17–22 (19) | 32–48 (41) | white, white with a yellowish tinge | 0 : 10 | 2 : 8 (CZA > MEA, CYA, CY20S ) |

| A. magnus (1) | 12–14 (13) | 12–14 (13) | 4–6 (5) | 13–15 (14) | 20–22 (21) | 16–17 (17) | 11–13 (12) | 19–20 (20) | pale yellow, yellowish gray | 1 : 0 (CYA) | 0 : 1 |

| A. neotritici (11) | 10–25 (18) | 14–28 (22) | 5–19 (12) | 19–31 (27) | 20–47 (31) | 21–50 (38) | 14–39 (25) | 28–60 (51) | white, yellowish white | 6 : 5 (CZA) | 4 : 7 (CZA) |

| A. pragensis (5) | 8–10 (9) | 9–14 (12) | 3–6 (5) | 13–18 (15) | 15–18 (16) | 16–22 (20) | 11–15 (12) | 24–30 (27) | white | 5 : 0 (CZA, CYA) | 2 : 3 (CYA > MEA) |

| A. subalbidus (19) | 11–17 (14) | 14–24 (20) | 8–18 (13) | 18–27 (22) | 18–30 (24) | 24–42 (32) | 16–26 (21) | 24–45 (33) | white, yellowish white | 12 : 7 (CYA > CZA) | 7 : 12 (CZA > CYA > MEA > CY20S) |

| A. taichungensis (3) | 16–18 (17) | 22–28 (25) | 10–12 (11) | 28–31 (30) | 25–29 (27) | 33–43 (38) | 19–21 (20) | 40–51 (46) | pastel yellow | 2 : 1 (CYA, MEA) | 2 : 1 (CZA, CY20S) |

| A. tenebricus (3) | 19–21 (20) | 19–23 (21) | 12–14 (13) | 28–30 (29) | 26–33 (30) | 29–34 (31) | 22–24 (23) | 48–52 (50) | white, yellowish white | 3 : 0 (CYA, CZA) | 2 : 1 (CZA) |

1Production was scored after 4 wk of cultivation on MEA, CYA, CZA and CY20S; the ratio shows the number of strains producing and not producing pigment/sclerotia; media on which pigment or slerotia were produced, are listed in the parentheses and sorted by frequency. See section Taxonomy for more details concerning colours of soluble pigments and sclerotia, and strain numbers.

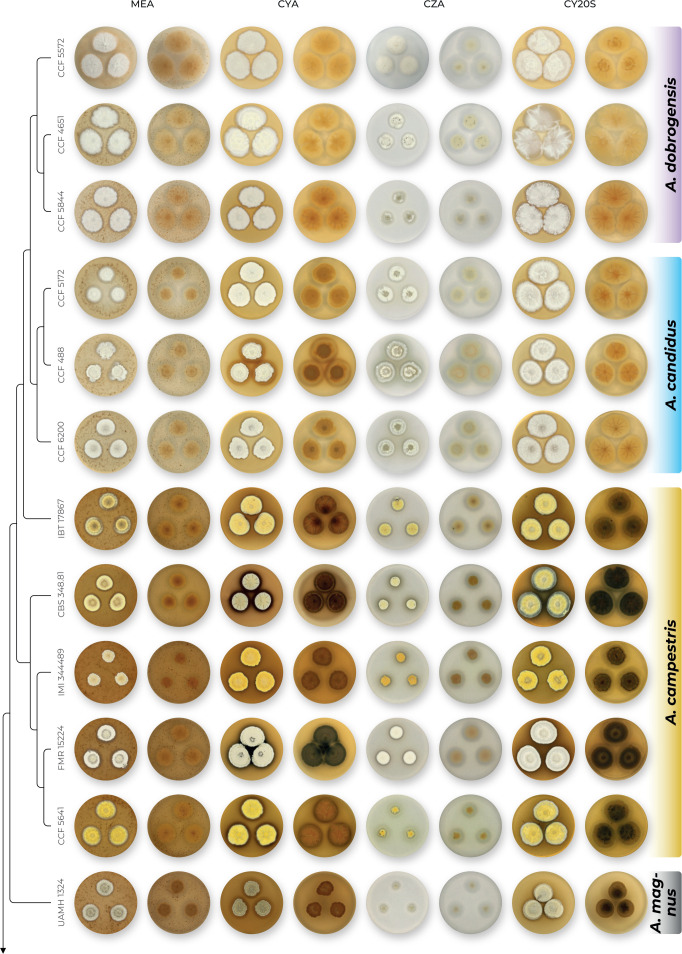

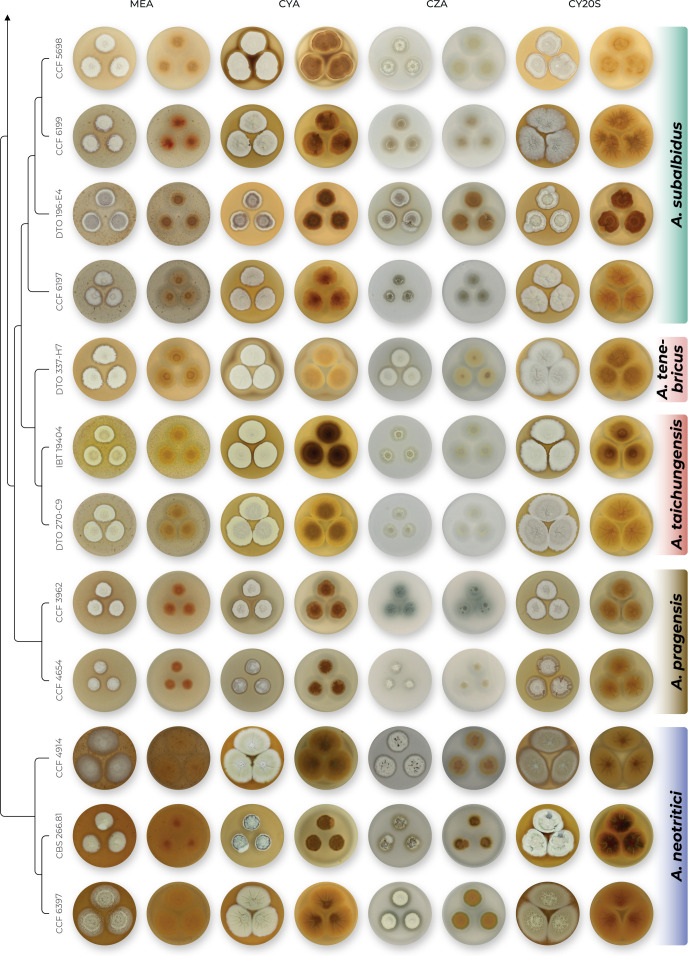

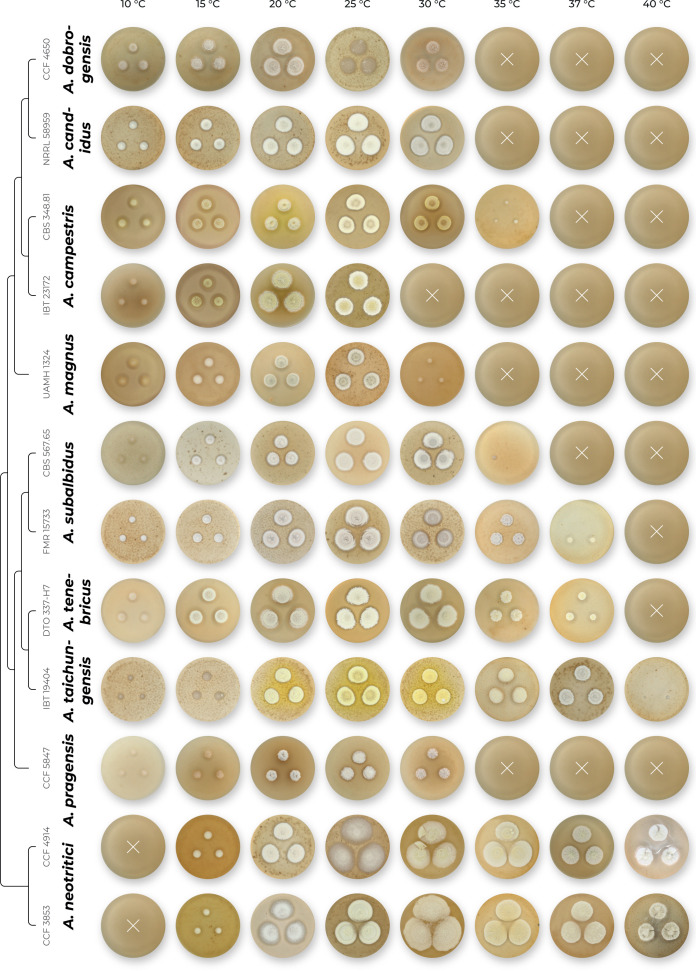

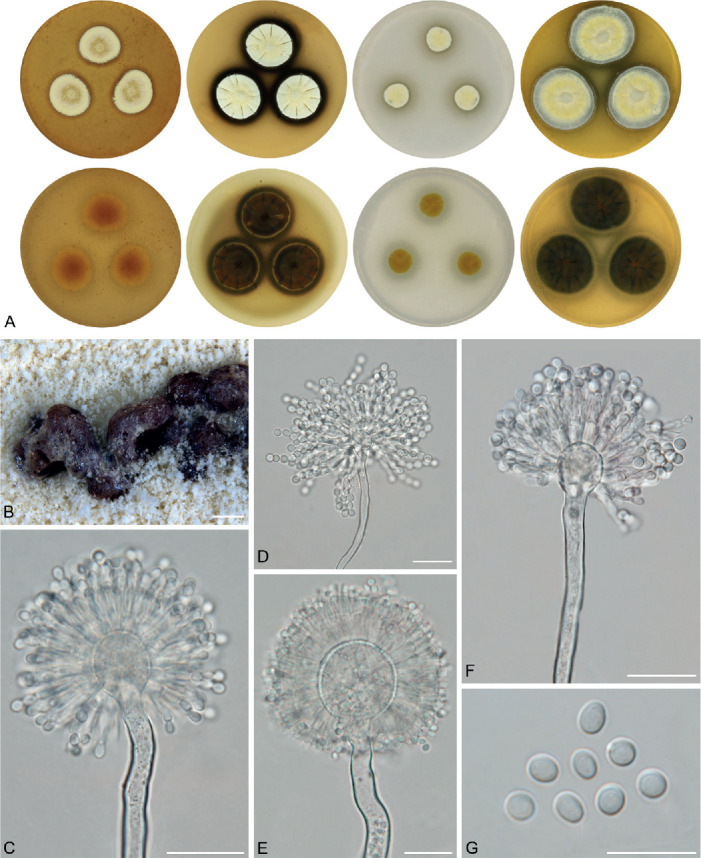

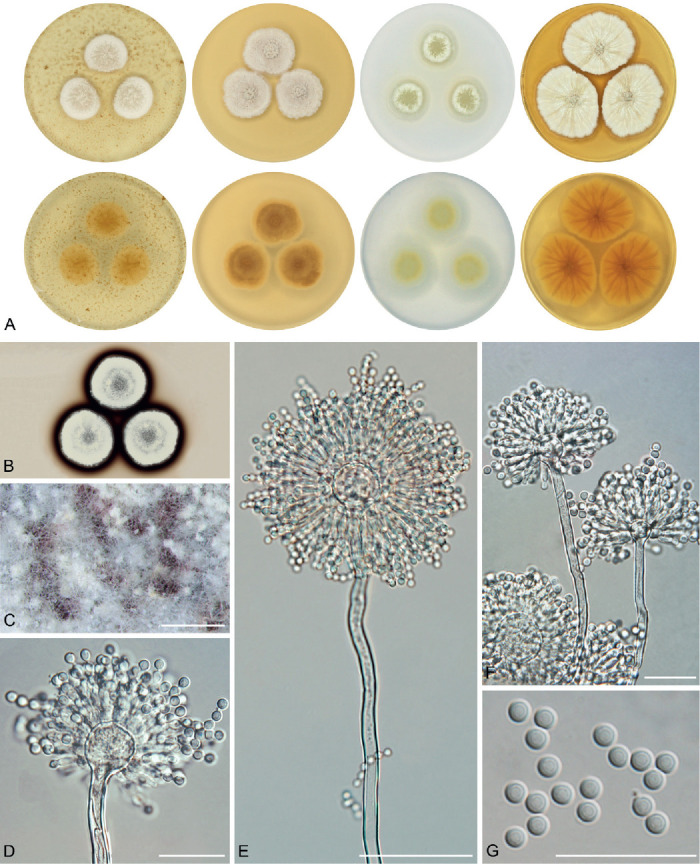

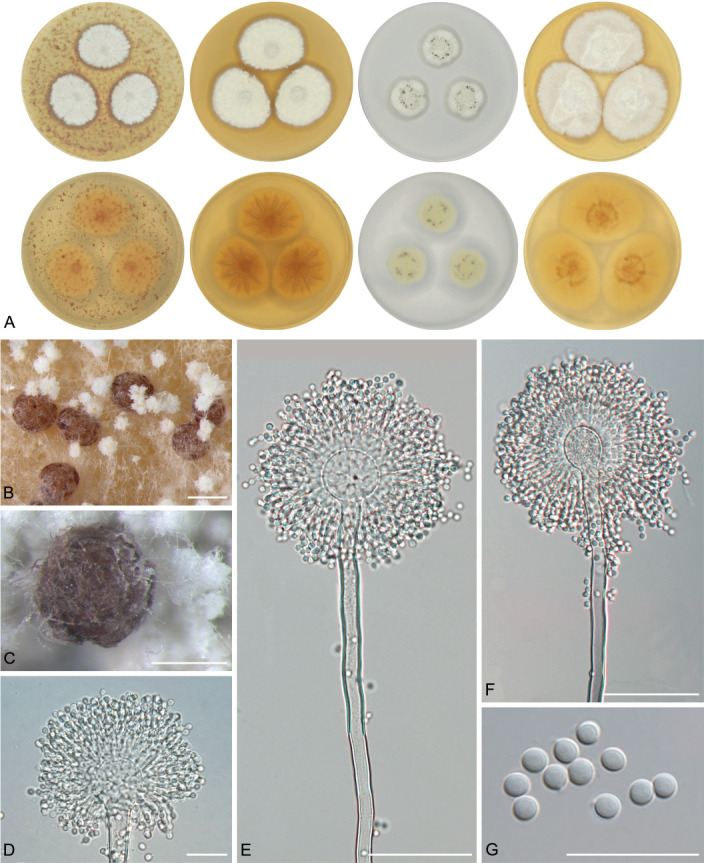

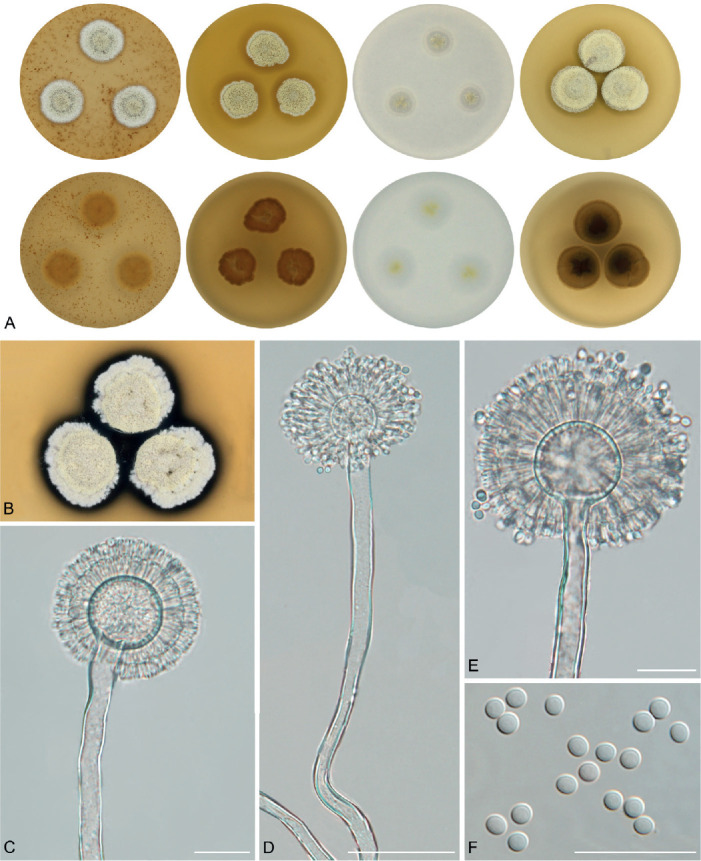

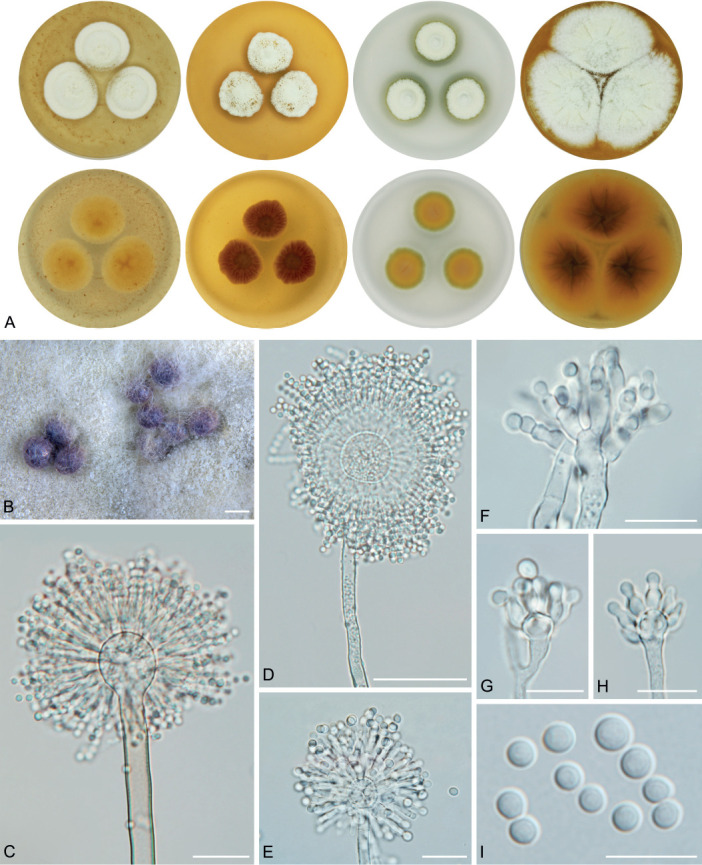

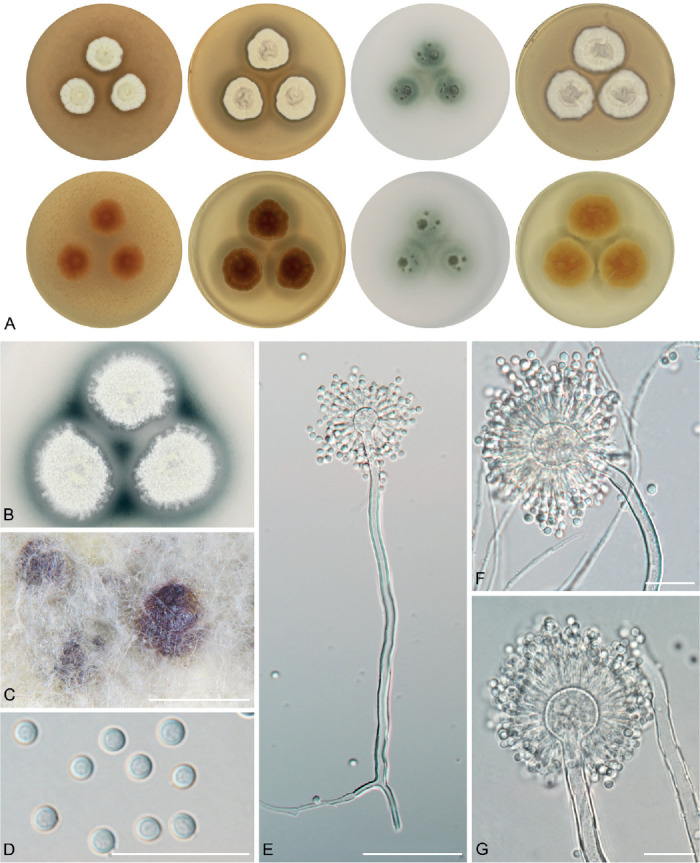

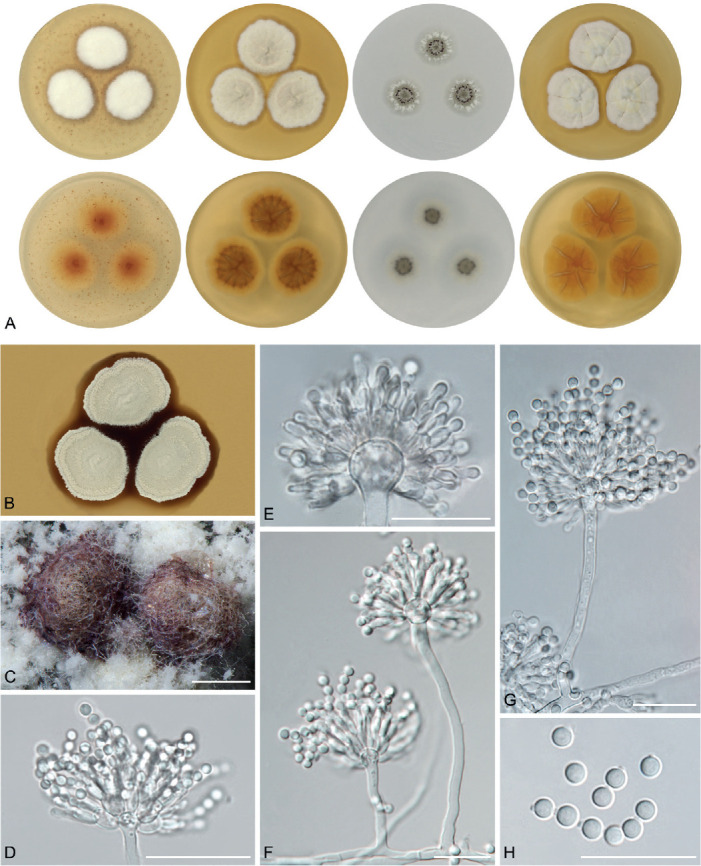

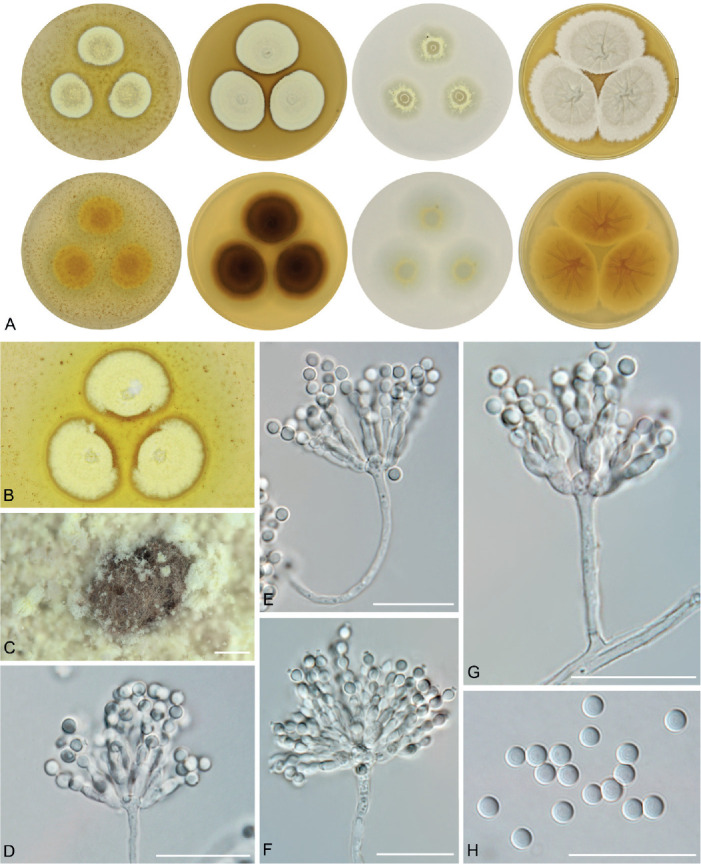

The overview of macromorphology of all species and their various morphotypes are shown in Fig. 5. Colony morphology of A. candidus is very similar to A. dobrogensis, but colonies of A. dobrogensis strains have a larger diameter on MEA, CYA and CY20S (Table 4). The colony colour of most species in the section Candidi is white or yellowish white, but shades of yellow dominate in A. campestris (usually yellow to sulphur yellow), A. magnus (greyish yellow on MEA, CYA and CY20S) and A. taichungensis (pastel yellow on CYA and MEA). Intraspecific variability in colony colour and dimensions is sometimes high. For instance, colonies of A. campestris, usually ascribed as yellow, sulphur yellow or bright yellow, were rather white or yellowish-white in FMR 15224. In addition, there were also significant differences in the shape and profile of colonies, production of soluble pigment and reverse colour among strains (Fig. 5), but without any phylogenetic pattern. Another phenotypically variable species was A. subalbidus with strains showing significant differences in their colony surfaces, dimensions and colours (Fig. 5). Two strains of A. subalbidus (DTO 196-E4 and FMR 15877) differed from other strains by their greyish beige colonies, but otherwise they did not display any other unique characteristics. Neither the other morphological variability observed in A. subalbidus displayed any phylogenetic pattern that could lead to considerations of segregation into multiple monophyletic species. Two strains of A. neotritici (CCF 4914 and IBT 12659), which formed their own subclade (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3), differed from other strains by more velvety colony surface and significantly deviated in micromorphology (see below).

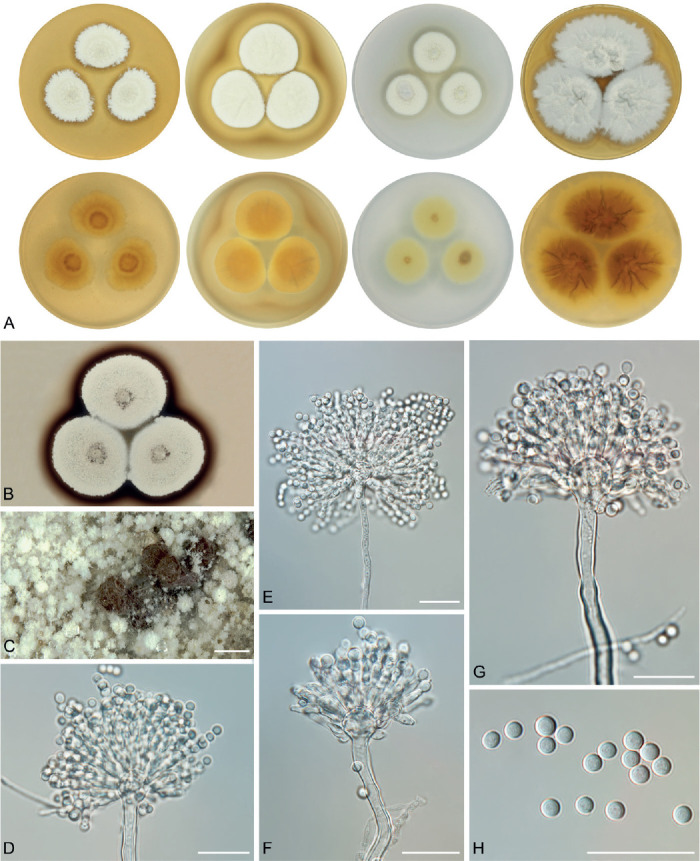

Fig. 5.

Overview of macromorphological patterns (obverse and reverse) within section Candidi on four cultivation media (MEA, CYA, CZ, CY20S) grown for 14 d at 25 °C. Macromorphological characters were scored in detail for 68 isolates and only unique phenotypic patterns are shown for every species.

Production of sclerotia was observed in all species (except A. magnus), mostly on CZA, CYA and MEA (Table 4). Except A. dobrogensis, at least some strains of every species produced soluble pigments after 4 wk of cultivation, most often on CZA and CYA (Table 4). In general, the production of sclerotia and soluble pigments was mostly strain-specific rather than species-specific. But in several species represented by more strains, we observed some trends, and in few cases, production of pigments contributed to the species differentiation. For instance, a dark brown soluble pigment was produced by A. tenebricus compared to yellow soluble pigment produced by some strains of A. taichungensis. Dark soluble pigments were also produced by all strains of A. campestris and A. pragensis but with variable intensity and location. In contrast, soluble pigments were observed to be absent in A. dobrogensis strains while in the closely related A. candidus, five out of nine examined strains produced pigments.

Phenotypic analysis – micromorphology

Dimensions of micromorphological characters are summarized in Table 5 and statistical significances of differences in these characters between species are detailed in Supplementary Table S1. Interesting phenomenon can be seen in A. neotritici because some strains of this species produce atypically short and uniseriate conidiophores only (CCF 4914 and IBT 12659) in contrast to other A. neotritici isolates and other section Candidi species. These strains formed a separate clade in benA and CaM phylogenies and were delimited as separate species by three single-locus MSC methods. The strain CBS 266.81, a reference strain of invalidly described A. tritici, produces atypically short, distorted and septate conidiophores. Colonies of this strain also have a smaller diameter than other A. neotritici isolates on all media and the strain produces abundant sclerotia.

Table 5.

| Species (no. of examined strains) |

Stipe

|

Metulae length; mean ± sd | Phialides length; mean ± sd | Vesicle diam; mean ± sd | Conidia (longer dimension); mean ± sd | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length; mean ± sd | Width; mean ± sd | |||||

| A. campestris (7) | (90–)250–850(–1 300); 507 ± 217.5 | (4–)5–7.5(–9); 5.9 ± 1.1 | (7–)8–14(–17); 10.1 ± 2.3 | (4.5–)5–7(–9); 5.9 ± 0.8 | (10.5–)14–22(–31.5); 17.1 ± 3.7 | (2.8–)3–4.5(–4.9); 3.8 ± 0.5 |

| A. candidus (9) | (70–)125–400(–520); 242 ± 101.5 | (2.5–)3.5–8.5(–9.5); 4.9 ± 1.6 | (4.5–)5.5–7.5(–8); 6 ± 0.7 | (4.5–)5–6.5(–7); 5.6 ±0.5 | (8–)10–23(–33); 14.7 ± 5.0 | (3.1–)3.3–4(–4.3); 3.7 ± 0.2 |

| A. dobrogensis (10) | (100–)150–1 150(–2 000); 609 ± 330.2 | (3–)5–7(–14); 6.2 ± 1.5 | (5–)5.5–12(–14); 8.4 ± 1.9 | (5–)5.5–7.5(–8.5); 6.4 ± 0.7 | (9–)10–30(–39.5); 19.6 ± 5.6 | (3–)3.4–4.1(–4.3); 3.7 ± 0.3 |

| A. magnus (1) | (540–)810–1 150(–1 600); 945 ± 225.8 | (6–)9–13(–16); 11.2 ± 2.4 | (7.5–)9–14(–17); 12.1 ± 2.8 | (4.5–)5.5–7(–8); 6.1 ± 0.8 | (18–)33–49(–45); 34.8 ± 8.0 | (3.2–)3.4–3.6(–3.8); 3.5 ± 0.2 |

| A. neotritici (9) | (140–)250–500(–700); 363 ± 109.73 | (3.5–)4–8(–9); 6.1 ± 1.03 | (4–)7–17(–21); 9.9 ± 3.33 | (2.5–)3.5–6(–8); 4.5 ± 0.9 | (11–)14–24(–28); 18.4 ± 3.73 | (2.6–)3–4.6(–5.1); 3.5 ± 0.5 |

| A. pragensis (5) | (40–)110–260(–380); 175 ± 82.1 | (3–)3.5–5(–6); 4.3 ± 0.6 | (4–)5–6.5(–8); 5.7 ± 0.8 | (4–)5–6(–6.5); 5.3 ± 0.4 | (7–)10–17(–23); 13.6 ± 3.1 | (3.1–)3.5–4(–4.6); 3.7 ± 0.3 |

| A. subalbidus (19) | (20–)50–330(–730); 136 ± 91.0 | (2.5–)3–8(–10); 4.2 ± 1.3 | (4–)6–11(–16.5); 7.4 ± 1.5 | (3.5–)4.5–6(–7.5); 5.4 ± 0.6 | (5–)7–23(–31); 11.8 ± 4.7 | (3–)3.2–4.2(–4.5); 3.7 ± 0.3 |

| A. taichungensis (3) | (15–)40–90(–215); 60 ± 31.4 | (2–)3–4(–5); 3.3 ± 0.7 | (4–)5.5–7(–9.5); 6.2 ± 0.8 | (3.5–)4.5–6.5(–7.5); 5.0 ± 0.5 | (5–)7–11(–15); 8.2 ± 2.0 | (2.8–)3–3.8(–4.1); 3.4 ± 0.3 |

| A. tenebricus (3) | (30–)80–140(–310); 114 ± 57.9 | (2.5–)3.5–5(–6.5); 4.2 ± 0.8 | (7–)8–12(–14); 9.9 ± 1.3 | (5.5–)6–7(–8.5); 6.7 ± 0.7 | (8.5–)11–18(–27); 14.3 ± 3.4 | (3.4–)3.6–3.9(–4.3); 3.8 ± 0.2 |

1Measured after 1–3 wk of cultivation on MEA at 25 °C.

2Statistical comparison of micromorphological characters between species is listed in Supplementary Table 1.

3Strains CCF 4914, IBT 12659 and CBS 266.81 were excluded because they produced short, uniseriate or atypical conidiophores.

Results of the micromorphological analysis show that the most important characters for distinguishing species are the length and width of stipe, vesicle diameter and the length of metulae. In contrast, conidial dimensions are characters that do not contribute to species differentiation (Fig. 6). Aspergillus magnus is easily distinguishable from other species. It has the longest and widest stipes, the largest vesicle and the longest metulae. Aspergillus dobrogensis has larger dimensions of stipes, vesicles, metulae and phialides compared to the closely related A. candidus (Fig. 6). This statement is however valid only for the species as a whole as there are several individual strains not differing from A. candidus (Fig. 7). The possibilities of micromorphological differentiation between related species A. subalbidus, A. taichungensis, A. tenebricus and A. pragensis are limited. Among these species, A. tenebricus typically has longer phialides and metulae. It also has a larger vesicle than A. taichungensis. Some phylogenetic methods supported segregation of clade “pop 6” from A. subalbidus or segregation of DTO 266-G2 from A. taichungensis. We did not observe any specific feature connecting these strains and differentiating them from other A. subalbidus strains. The strain DTO 266-G2 also did not show unique characters compared to remaining A. taichungensis strains except much weaker production of yellow soluble pigment.

Fig. 6.

Summary overview of seven micromorphological characters across species of section Candidi. Boxplots show median, interquartile range, values within ± 1.5 of interquartile range (whiskers) and outliers.

Fig. 7.

A detailed overview of seven micromorphological characters at a strain level. Boxplots show median, interquartile range, values within ± 1.5 of interquartile range (whiskers) and outliers.

In some species, we observed remarkable differences in individual microscopic characters between strains. For example, in the A. campestris lineage, strain IMI 344489 produced larger conidia while strain CBS 348.81 had larger vesicles (Fig. 7). In the A. subalbidus lineage, strain DTO 196-E4 produced significantly larger stipes and vesicles, and among A. neotritici strains, CCF 4030 had longer metulae and CCF 3853 produced larger conidia (Fig. 7). These phenotypically exceptional strains did not form any well-defined phylogenetic units.

We did not observe any differences in surface ornamentation of conidia between species when using SEM (Fig. 8). Conidia of all species were smooth-walled or occasionally finely roughened.

Fig. 8.

Conidia under scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Examined strains from left to right: A. dobrogensis - CCF 4649, IBT 29476, IBT 29476; A. candidus - CCF 3996, CBS 566.65, CCF 3996; A. campestris - FMR 15224, FMR 15226, IBT 23172; A. magnus - UAMH 1324 only; A. subalbidus - FMR 15877, CBS 122449, CCF 5643; A. taichungensis - DTO 266-G2 only; A. tenebricus - DTO 440-E1, DTO 337-H7, DTO 337-H7; A. pragensis - CCF 4654, CCF 3962, CCF 4654; A. neotritici - CCF 4653, CBS 266.81, IBT 12659. Scale bars = 2 μm.

Physiology

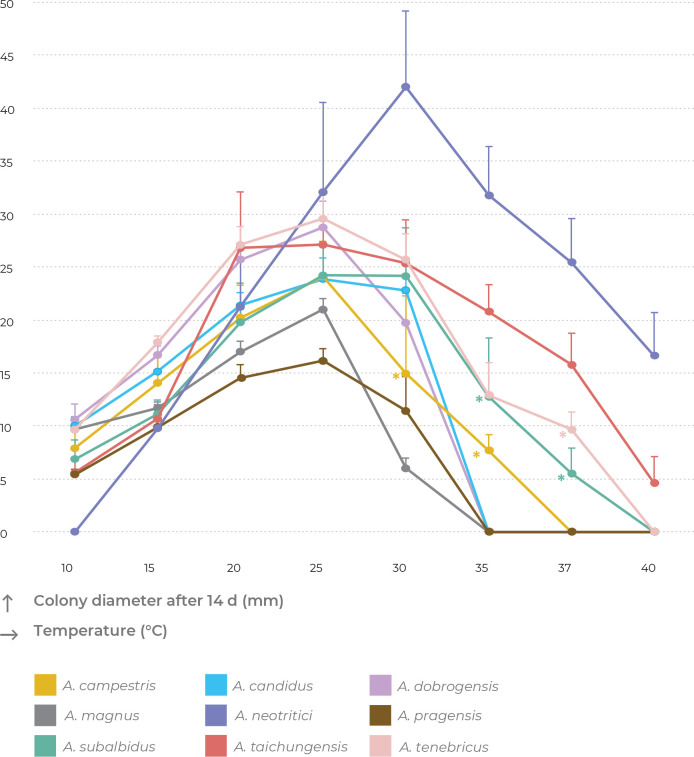

Cardinal temperatures were assessed on MEA at nine different temperatures ranging from 10 to 45 °C. The most common growth patterns are shown in Fig. 9. Aspergillus neotritici is the only species which is not able of growing or at least germinating at 10 °C and its optimal growth temperature is around 30 °C, while all other species have optima around 25 °C or do not grow faster at 30 °C compared to 25 °C. At least some strains of four species can grow at 37 °C, namely, A. neotritici, A. subalbidus, A. taichungensis and A. tenebricus. All strains of A. taichungensis and A. neotritici grow or germinate at 40 °C (Fig. 10). An unusually wide variability was observed in the temperature maximum of A. campestris. Some strains of this species do not grow at 30 °C (IBT 17867, IBT 23172), while all others grow well at this temperature, and the ex-type strain (CBS 348.81) grows up to 35 °C. Similarly, only some strains (CBS 567.65, FMR 15736, NRRL 58123, FMR 15733, CCF 5643, NRRL 4809, CCF 5697, CCF 6197) of A. subalbidus were able to grow at 35 °C and only some strains of A. subalbidus (CCF 5643, CCF 5697, FMR 15733) and A. tenebricus (DTO 337-H7, DTO 440-E2) could grow at 37 °C (Table 6, Fig. 9, Fig. 10).

Fig. 9.

Temperature growth profiles of Aspergillus section Candidi members after 14 d on MEA at temperatures ranging from 10 °C to 40 °C. Physiological characters were scored in detail for 52 isolates and only predominant patterns are shown for every species. For details, see Table 6 and section Taxonomy.

Fig. 10.

Growth of section Candidi members after 14 d on MEA at temperatures ranging from 10 °C to 40 °C. The points on the curves show the mean values and standard deviations. When isolates of the same species differed in their maximum growth temperatures, zero values were omitted for calculation of mean values (these points are designated by asterisks).

Table 6.

Overview of growth parameters at different temperatures.

| Species (no. of examined strains) |

Colony diameter after 14 d of cultivation on MEA in mm (mean value)

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 °C | 15 °C | 20 °C | 25 °C | 30 °C | 35 °C | 37 °C | 40 °C | |

| A. campestris (7) | 4–10 (8) | 10–17 (14) | 15–26 (20) | 16–28 (24) | 0–22 (18)1 | 0–4 (3)1 | — | — |

| A. candidus (5) | 8–11 (10) | 12–17 (15) | 20–23 (21) | 20–27 (24) | 18–25 (23) | — | — | — |

| A. dobrogensis (6) | 9–13 (11) | 15–18 (17) | 24–27 (26) | 23–32 (29) | 17–24 (20) | — | — | — |

| A. magnus (1) | 9–10 (10) | 11–12 (12) | 16–18 (17) | 20–22 (21) | 5–7 (6) | — | — | — |

| A. neotritici (6) | — | 4–13 (10) | 11–26 (21) | 23–47 (32) | 32–51 (42) | 30–42 (32) | 18–33 (25) | 4–22 (17) |

| A. pragensis (5) | 5–6 (5) | 9–11 (10) | 13–17 (15) | 15–18 (16) | 3–14 (11) | — | — | — |

| A. subalbidus (16) | 3–9 (7) | 9–14 (11) | 15–30 (20) | 18–30 (24) | 9–29 (24) | 0–22 (13)1 | 0–9 (6)1 | — |

| A. taichungensis (3) | 4–7 (6) | 9–12 (11) | 20–32 (27) | 25–29 (27) | 20–29 (25) | 18–25 (21) | 12–20 (16) | 1–7 (5) |

| A. tenebricus (3) | 9–11 (10) | 17–19 (18) | 25–29 (27) | 26–33 (30) | 22–29 (26) | 8–16 (13) | 0–12 (10)1 | — |

1The mean was calculated from non-zero values only.

— no growth.

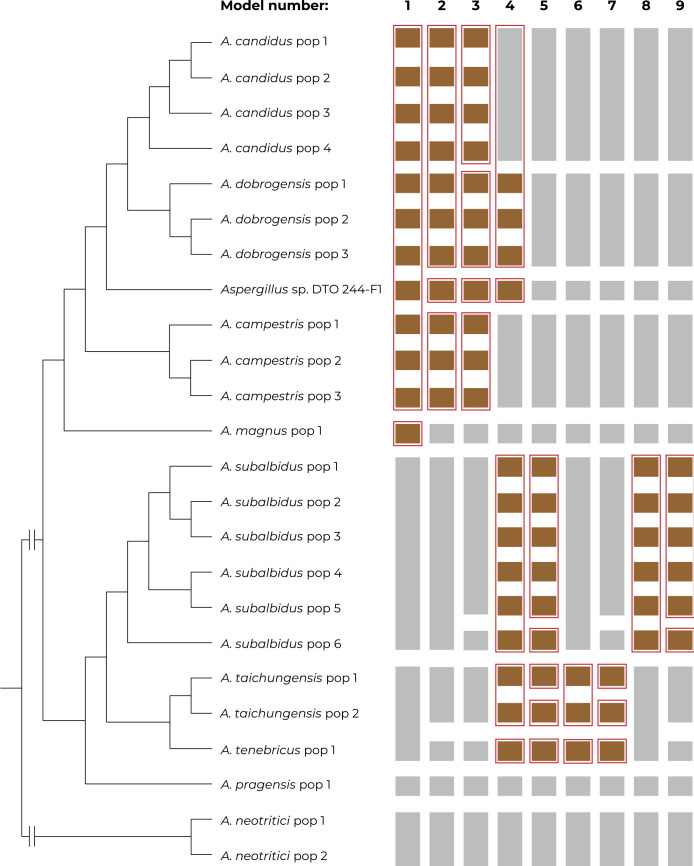

Species delimitation using DELINEATE software

The species hypotheses were independently tested in DELINEATE software where we set up nine different models. The results are summarized in Fig. 11. Individual populations were either assigned into species according to the previous results of species delimitation (Supplementary Table S2) - grey coloured bars, or they were left unassigned and free to be delimited - brown coloured bars. The red frames show the resulting solution proposed by DELINEATE for every model.

Fig. 11.

The results of species validation using the software DELINEATE. Nine models of species boundaries were set up and tested. The brown bars represent unassigned populations left free to be delimited, while the grey bars represent the predefined species. The resulting solutions suggested by DELINEATE are depicted by red frames around bars. The populations of each species were delimited by BPP software (Supplementary Table S2) and the displayed tree was calculated in starBEAST.