In this issue of Lancet Regional Health-Americas, Mikaela Smith and colleagues use data from the Guttmacher Institute and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to examine the frequency with which people in the United States cross state lines for abortion care.1 This is an important study both because the extent to which one has to go to another state is an understudied aspect of abortion care and because the findings will likely serve as a baseline for comparison after the US Supreme Court hands down a decision in Dobbs v Jackson Women's Health Organization, which may overturn the precedent set with Roe in 1973.2

Abortion is an experience shared by millions of women worldwide every year, including by 860,000 women annually in the United States.3,4 Moreover estimates suggest that nearly 1 in 4 U.S. women will have an abortion by age 45.5 Despite the frequency with which people have abortions in the US, it is likely the only type of health care that requires so many individuals to leave their state.

This travel compounds the obstacles that many already face when accessing abortion care, especially for vulnerable populations. Challenges include finding a way to pay for the abortion, taking time off work, and having to arrange childcare—and doing all this again if the state has an in-person two visit requirement. Smith and colleagues found that the proportion of abortion patients who crossed state lines for care was four times larger—12%—in states whose legislatures were hostile to abortion rights, compared to 3% in states generally supportive of abortion rights. Other research further shows that restrictions may not just push abortions across state lines but force women to give birth following an unwanted pregnancy.6,7

One mechanism through which state legislators have tried to obstruct access to abortion has been through intentionally onerous regulations which make it difficult for providers to operate.8 When faced with numerous burdensome and costly regulations, clinics sometimes are forced to stop providing abortion care or find it too difficult to start providing in the first place. This is one reason 5 states only have one abortion clinic.

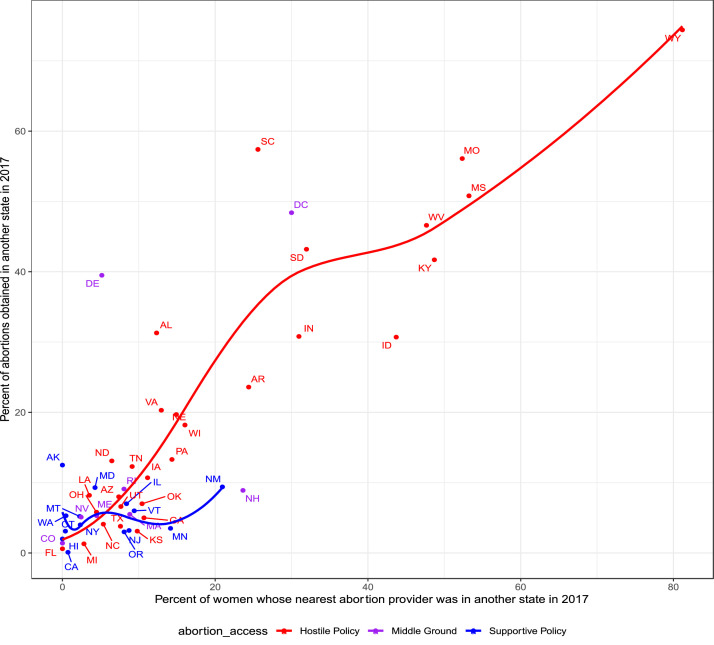

Smith and colleagues did not find evidence that the number of clinics per million women was associated with the proportion of patients who received care out of state within policy strata. However, they posited that an association might be found with a less ‘crude’ measure of facility density. For this reason, we used data from our previously published analysis of distance to nearest abortion clinic to examine the proportion of women whose nearest provider was in another state.9 We plotted these proportions against those from Smith and colleagues, with loess curves for hostile and supportive states (Figure 1). Among hostile states, the correlation between the proportion of women whose nearest provider was in another state and the proportion who obtained care out of state was .91 compared to .21 in supportive states. This may reflect that people often prefer to seek care in state because that is where their doctors and insurance coverage are. This may be why some who live in supportive states still seek care in state regardless of where the nearest clinic is—this is represented in the relatively flat curve and low correlation. In contrast, people who live in hostile states are much more often traveling when the nearest clinic is outside their state-and, moreover, as Smith and colleagues find, frequently to another hostile state.

Figure 1.

Proportion of women whose nearest clinic was in, and proportion of patients to traveled to, another state, by policy environment.

Anyone who wants and needs an abortion should be able to get timely, affordable and compassionate care, ideally in their own community, and certainly within their own state. Unfortunately, however, abortion is highly regulated-not for medical reasons but for political ones-and states with policy environments hostile to abortion access are clustered together in the South and Midwest. With more restrictions and quite possibly outright bans on the horizon, it may become impossible for many to obtain an abortion either in their state or a bordering state.

Research shows being denied an abortion compounds economic disadvantage.10 Moreover, politically-motivated policies that erect barriers to abortion care will most severely impact those with the fewest financial resources as well as those who are systematically oppressed. Such policies do not just prevent access to abortion care, but the fulfillment of one's right to control their own body and future.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

We thank Elizabeth Nash, Joerg Dreweke, Kathryn Kost, and Kimberly Lufkin for their comments.

References

- 1.Smith M.H., Muzyczk Z., Chakraborty P., et al. Abortion travel within the United States: an observational study of cross-state movement to obtain abortion care in the United States in 2017. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2022;10 doi: 10.1016/j.lana.2022.100214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sobel L., Ramaswamy A., Salganicoff A. Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health; 2021. Abortion at SCOTUS.https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/abortion-at-scotus-dobbs-v-jackson-womens-health/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bearak J., et al. Unintended pregnancy and abortion by income, region, and the legal status of abortion: estimates from a comprehensive model for 1990–2019. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e1152–e1161. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30315-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones, RK, Witwer, E. & Jerman, J. Abortion incidence and service availability in the United States, Guttmacher Institute. 2017. https://www.guttmacher.org/report/abortion-incidence-service-availability-us-2017 (2019).

- 5.Jones R., Jerman J. Population group abortion rates and lifetime incidence of abortion: United States, 2008–2014. Am J Public Health. 2017;107:1904–1909. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts S.C.M., Johns N.E., Williams V., Wingo E., Upadhyay U.D. Estimating the proportion of Medicaid-eligible pregnant women in Louisiana who do not get abortions when Medicaid does not cover abortion. BMC Womens Health. 2019;19:78. doi: 10.1186/s12905-019-0775-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Upadhyay U.D., McCook A.A., Bennett A.H., Cartwright A.F., Roberts S.C.M. State abortion policies and Medicaid coverage of abortion are associated with pregnancy outcomes among individuals seeking abortion recruited using Google Ads: a national cohort study. Soc Sci Med. 2021;274 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerdts C., Fuentes L., Grossman D., et al. Impact of clinic closures on women obtaining abortion services after implementation of a restrictive law in Texas. Am J Public Health. 2016;106:857–864. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bearak J.M., Burke K.L., Jones R.K. Disparities and change over time in distance women would need to travel to have an abortion in the USA: a spatial analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2:e493–e500. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30158-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foster D.G., Biggs M.A., Ralph L., Gerdts C., Roberts S., Glymour M.M. Socioeconomic outcomes of women who receive and women who are denied wanted abortions in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(3):407–413. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]