Abstract

Purpose:

To examine gender differences in visual functioning using the National Eye Institute Visual Functioning Questionnaire-25 (VFQ-25) in a Colorado cohort of patients with age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

Methods:

A retrospective cohort study was conducted using a registry of AMD patients who attended the Sue Anschutz-Rodgers Eye Center (2014 to 2019). Demographic, clinical, and image data were collected, and AMD was categorized as Early/Intermediate AMD, or unilateral/bilateral neovascular (NV) AMD, geographic atrophy (GA), or Both Advanced using the Beckman Classification. Each patient completed the VFQ-25, which evaluates visual functioning, generating a composite score and subscale scores for vision-specific activities. Univariate and multivariable general linear models were used to estimate the associations between gender and VFQ −25 scores with parameter estimates (PE) and standard errors (SE).

Results:

Among 739 patients with AMD, 294 (39.8%), 115 (15.6%), 168 (22.7%), and 162 (21.9%) were diagnosed with Early/Intermediate AMD, GA, NV AMD, and Both Advanced, respectively. Adjusted for AMD classification, age and habitual visual acuity in the better-seeing and worse-seeing eyes, female gender was not significantly associated with lower composite VFQ-25 scores (PE (SE): −1.2 (0.9), p = .193), and was significantly associated with reportedly worse ocular pain and driving subscale scores (PE (SE): −4.6 (1.0), p < .0001 and −9.1 (2.1), p < .0001, respectively).

Conclusion:

Gender plays a role in reported driving activities and ocular pain among patients with AMD. This may need to be accounted for in future research related to the use of VFQ-25 for AMD.

Keywords: Age-related macular degeneration (AMD), visual functioning, gender, NEI VFQ-25

Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that is the leading cause of severe vision loss among individuals aged 55 years and older in Western countries.1,2 AMD affects an estimated 11 million Americans and will likely impact 22 million individuals in the United States alone by 2050.2 AMD is characterized by loss of central vision, which can hinder a patient’s ability to perform basic tasks such as reading, recognizing faces, viewing fine details, and driving.3,4 AMD can result in profound and irreversible visual impairment.1 Based on a clinical classification system described by the Beckman Initiative for Macular Research Classification Committee, the disease can be categorized as early, intermediate, or advanced AMD.5 Advanced AMD can be further divided into neovascular (NV) AMD and geographic atrophy (GA).

In recent times there has been increasing awareness of the importance of integrating sex and gender into medical research.6–9 In the area of quality of life research it has been reported that females consistently report lower generic health-related quality of life measures than males in population-based, community-based, and elderly cohorts.10–14 Gender has also been recognized as important in ophthalmology research, specifically in research involving measures of visual functioning among patients with cataracts, keratoconus, and other visual impairments.15–19

The National Eye Institute Visual Functioning Questionnaire-25 (NEI VFQ-25) was developed to evaluate visual functioning among individuals with low vision or ocular conditions. It measures the extent to which vision problems affect a patient’s daily functioning and self-reported health status, including factors such as social functioning and emotional well-being.20,21 Several studies have supported the validity and reliability of this questionnaire.22–24

Prior publications evaluating the impact of gender on visual functioning among patients with AMD have found conflicting results. Female gender was significantly associated with worse physical functioning and mental health in patients with AMD and longitudinal declines in composite VFQ-25 scores among patients with GA and NV AMD.25,26 In one study of patients with subfoveal choroidal neovascularization from AMD, males reported significantly worse general vision and role difficulties and significantly better driving than their female counterparts.27 However, other studies indicate that there are no significant gender differences in visual functioning and the ability to carry out daily activities among patients with AMD.28,29

These studies offer evidence of gender differences in quality of life and indicate some gender differences in visual functioning as well. However, the available few published studies have focused on one or two particular advanced groups of AMD and have not examined the non-advanced forms of AMD or distinguished between unilateral and bilateral disease when investigating gender disparities. As described in our previous research,30 it is important to account for these classifications as they can profoundly influence patients’ visual functioning. Thus, building on our previous research in this area,30,31 the purpose of this study was to assess gender differences in overall visual functioning and vision-specific activities in a cohort of patients with AMD, distinguished by AMD classification stage and number of eyes affected.

Materials and methods

AMD registry

In 2014, the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine developed a registry of patients with a diagnosis of AMD attending the retina clinics at the Sue Anschutz-Rodgers Eye Center. The results presented in this study are based on patients enrolled in the registry from July 9, 2014 to December 31, 2019. The study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board and adhered to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all patients. The registry includes demographic data, clinical characteristics, and image data for each patient. At the time of enrollment into the registry the NEI’s VFQ-25 was completed on each patient. The methods used for this database are described in further detail elsewhere.32

Definitions of sex and gender

Although the terms gender and sex are often used interchangeably, they have distinct meanings. Sex is a biological variable defined by physiological and anatomical attributes encoded in DNA, such as hormone levels and reproductive organs.6 In contrast, gender encompasses social, cultural, and psychological factors that impact an individual’s self-identity.6 While both sex and gender can profoundly influence health and disease, this study specifically measured gender.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients who were between 55 and 99 years of age, had AMD in one or both eyes, and had the capacity to provide consent were eligible for inclusion in the registry. Exclusion criteria included terminal illness, active ocular inflammatory disease, prior treatment with anti–vascular endothelial growth factor injections, panretinal photocoagulation, and branch and central retinal vein occlusion. Further exclusion criteria included proliferative diabetic retinopathy, non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy, diabetic macular edema, cystoid macular edema, macula-off retinal detachment, central serous retinopathy, full-thickness macular hole, ocular melanoma, pattern/occult macular dystrophy, macular telangiectasia, corneal transplant, drusen not cause by age-related macular degeneration, current systemic treatment for cancer, or any serious mental health /advanced dementia issues.

Classification of AMD

Retinal images were reviewed and classified by two vitreo-retinal specialists based on the previously described clinical classification system.5 Discrepancies were settled by a third vitreo-retinal specialist. The classification was determined using multimodal imaging including spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT), near infrared reflectance (NIR), short-wavelength fundus autofluorescence (FAF) and color fundus photography.

AMD classification at enrollment was categorized as early AMD, intermediate AMD or subcategories of advanced AMD: NV AMD and GA. Eyes with both NV and GA were characterized as “Both Advanced”. Advanced AMD categories were further designated as unilateral or bilateral disease. For the purposes of this research project, the early and intermediate groups were combined into one group, early/intermediate AMD.

Visual acuity

A certified ophthalmic technician assessed each patient’s habitual visual acuity (HVA) using Snellen measures, which were subsequently converted to corresponding LogMAR values for statistical analyses. The eye with the lower LogMAR value was categorized as the “better-seeing eye” and the eye with the higher LogMAR value was the “worse-seeing eye”.

NEI VFQ-25

At the time of enrollment, each patient in the study completed the National Eye Institute Visual Functioning Questionnaire-25 (NEI VFQ-25), which measures how vision impacts the physical, mental, and social domains of health and functioning for individuals with chronic eye diseases.20 This multidimensional questionnaire includes the following scales: global vision, difficulty with near vision activities, difficulty with distance vision activities, limitations in social functioning, role limitations, dependency, mental health symptoms, driving difficulties, peripheral vision, color vision, ocular pain, and general health.21 The NEI VFQ-25 has been previously validated for measuring visual functioning among patients with AMD.22,23

The NEI VFQ-25 generates scores for each subscale, as well as a composite score, which is the average of the vision-targeted subscale scores with the exception of general health.21 The scores for each subscale range from 0 to 100, with 0 representing the lowest possible visual functioning and 100 representing the highest or best possible visual functioning.20

Statistical analysis

The demographic characteristics and habitual visual acuity (HVA) of the study sample were summarized by AMD classification and number of eyes affected. Student t-testing and Wilcoxon rank sum testing were used to compare age and HVA by gender for each AMD group. Univariate and multivariable general linear models were used to estimate the associations between gender and visual functioning scores, with gender as the primary explanatory variable and NEI VFQ-25 composite and subscale scores as the dependent variables. There were two adjusted models, the first adjusted model included classification of AMD and age as potential confounding variables. The second adjusted model included AMD classification, age, and also HVA in both the better-seeing and worse-seeing eyes to show visual functioning adjusted for visual acuity. Least square means, standard errors, and p-values from the multivariable models were presented, with p-values of less than 0.05 considered statistically significant. Analyses were conducted using SAS (version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

A total of 760 patients who met the study inclusion criteria participated in the study. Of these, 21 were excluded from analysis due to unresolved AMD status, missing imaging data, or largely incomplete VFQ-25 questionnaires. The remaining 739 patients were included in the final analysis. More specific details and numbers for each of the AMD groups are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Detailed description of the AMD classification groups.

| AMD classification and eyes affected | Number of patients | More detailed description |

|---|---|---|

| Unilateral Early/Intermediate AMD | 22 | 10 unilateral early; 12 unilateral intermediate |

| Bilateral Early/Intermediate AMD | 272 | |

| 33 | Both eyes early | |

| 213 | Both eyes intermediate | |

| 26 | One eye early, one eye intermediate | |

| Unilateral GA | 31 | GA in one eye and NV in neither |

| Bilateral GA | 84 | GA in both eyes and NV in neither |

| Unilateral NV AMD | 137 | NV in one eye and GA in neither |

| Bilateral NV AMD | 31 | NV in both eyes and GA in neither |

| Unilateral both advanced | 32 | One affected eye has both NV and GA |

| Bilateral both advanced | 130 | |

| 10 | One eye NV and one eye GA | |

| 34 | Both eyes GA and one eye NV | |

| 21 | Both eyes NV and one eye GA | |

| 65 | Both eyes GA and NV |

In Table 2 we present the demographic characteristics and habitual visual acuity of the study sample, stratified by AMD classification and number of eyes affected. Of the 739 patients, 294 (39.8%) were diagnosed with Early/ Intermediate AMD, 115 (15.6%) with GA, 168 (22.7%) with NV AMD, and 162 (21.9%) were categorized as Both Advanced. While the majority of patients with GA and Both Advanced had bilateral disease (73.0% and 80.2%, respectively), the NV AMD group was primarily composed of patients with unilateral disease (81.5%). Gender distribution was fairly similar across AMD classification. In each AMD classification group, with the exception of Unilateral Both Advanced, the mean age between genders did not differ significantly. Furthermore, in most AMD classification groups, except for Early/Intermediate AMD and Unilateral NV AMD, there were no significant gender differences in mean LogMAR HVA for the better-seeing eye or the worse-seeing eye. When all AMD groups were combined, mean LogMAR HVA was slightly worse for females compared to males (p = .055), and this association remained borderline significant after adjustment for AMD classification and age (p = .061). LogMAR HVA was significantly associated with VFQ-25 scores in univariate and multivariable regression adjusted for AMD classification, age and gender (p < .0001 in both models).

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics by AMD classification and number of eyes affected.

| Early/Int. AMD | Advanced AMD | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eiAMD | GA | NV AMD | Both Advanced | ||||

| Unilateral | Bilateral | Unilateral | Bilateral | Unilateral | Bilateral | ||

| # Patients | 294 | 31 | 84 | 137 | 31 | 32 | 130 |

| Female gender | 61.2% | 54.8% | 58.3% | 56.9% | 54.8% | 46.9% | 64.6% |

| Age, Mean (SD) | |||||||

| Male | 76.7 (7.2) | 80.3 (8.6) | 82.4 (6.7) | 77.3 (8.5) | 77.5 (10.7) | 76.2 (5.2) | 83.0 (7.6) |

| Female | 75.9 (7.3) | 80.9 (7.5) | 81.9 (8.3) | 78.7 (8.2) | 81.4 (9.4) | 81.2 (7.7) | 82.7 (8.1) |

| p-value* | 0.314 | 0.844 | 0.808 | 0.342 | 0.281 | 0.038 | 0.865 |

| LogMAR for better-seeing eye, Mean (SD) Male | 0.08 (0.12) | 0.24 (0.20) | 0.45 (0.34) | 0.12 (0.18) | 0.23 (0.37) | 0.18 (0.16) | 0.38 (0.27) |

| Female | 0.09 (0.11) | 0.33 (0.70) | 0.39 (0.33) | 0.18 (0.18) | 0.24 (0.31) | 0.15 (0.18) | 0.53 (0.50) |

| p-value** | 0.040 | 0.368 | 0.364 | 0.022 | 0.855 | 0.411 | 0.102 |

| LogMAR for worse-seeing eye, Mean (SD) Male | 0.26 (0.37) | 0.80 (0.97) | 0.77 (0.64) | 0.67 (0.86) | 0.58 (0.56) | 0.69 (0.66) | 1.37 (1.10) |

| Female | 0.28 (0.36) | 0.65 (0.73) | 0.96 (0.89) | 0.71 (0.83) | 0.95 (1.04) | 1.02 (0.86) | 1.40 (1.01) |

| p-value** | 0.158 | 0.779 | 0.689 | 0.231 | 0.380 | 0.165 | 0.421 |

Student t-test.

Wilcoxon rank sum test.

To evaluate gender differences in VFQ-25 scores, three separate models were performed for the composite score and each subscale score. The three models for each score are: 1) univariate analysis of gender; 2) multivariable analysis of gender while adjusting for AMD classification and age; and 3) multivariable analysis of gender while adjusting for AMD classification, age, and LogMAR values of the better-seeing and worse-seeing eyes. As shown in Table 3, gender was significantly associated with composite VFQ-25 scores, with female patients reporting an average of 2.2 (SE: 1.1) points lower than males in AMD classification and age-adjusted multivariable general linear regression analysis (p = .038), however, this difference was no longer significant when HVA was included in the model (p = .193). In the fully adjusted subscale models, female patients scored on average 4.6 points below males in ocular pain (p < .0001) and 9.1 (SE: 2.1) points below males in driving (p < .0001). Females were more likely to not have a driving subscale score (17.5% for females versus 4.7% for males) which is the case if the patient is not currently driving for reasons other than eyesight or because of both eyesight and other reasons. There is a question in the VFQ-25 regarding current driving status that is not factored into the scoring. In total, 202/739 (27.3%) participants reported not currently driving and these rates were higher for females, 33.4%, compared to males, 18.4% (p < .0001). Gender was not significantly associated with the other VFQ-25 subscale scores in the fully adjusted models.

Table 3.

Gender differences in composite and subscale VFQ-25 scores, and significance of gender in univariate and multivariate models.

| Univariate Model | Multivariate Model adjusted for AMD classification and age | Multivariate Model adjusted for AMD classification, age, and HVA* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter Estimate (SE) | Parameter Estimate (SE) | Parameter Estimate (SE) | |

| Composite Score | −2.7 (1.2) | −2.2 (1.1) | −1.2 (0.9) |

| 0.032 | 0.038 | 0.193 | |

| Subscales Scores | |||

| General Health | −0.1 (1.8) | −0.2 (1.8) | 0.2 (1.8) |

| 0.966 | 0.929 | 0.932 | |

| General Vision | −1.1 (1.3) | −1.1 (1.3) | 0.0 (1.1) |

| 0.410 | 0.410 | 0.996 | |

| Ocular Pain | −4.4 (1.0) | −4.5 (1.0) | −4.6 (1.0) |

| <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| Near Activities | −0.8 (2.0) | −0.2 (1.7) | 1.4 (1.5) |

| 0.692 | 0.928 | 0.349 | |

| Distance Activities | −4.1 (1.7) | −3.6 (1.5) | −2.4 (1.4) |

| 0.013 | 0.016 | 0.077 | |

| Social Functioning | 0.4 (1.3) | 0.8 (1.2) | −1.9 (1.1) |

| 0.747 | 0.506 | 0.090 | |

| Mental Health | −3.6 (1.9) | −3.3 (1.7) | −2.2 (1.6) |

| 0.056 | 0.056 | 0.176 | |

| Role Limitations | −3.4 (2.0) | −2.9 (1.9) | −1.9 (1.8) |

| 0.092 | 0.123 | 0.299 | |

| Dependency | −0.8 (1.9) | −0.1 (1.7) | 1.3 (1.5) |

| 0.663 | 0.952 | 0.373 | |

| Driving | −10.8 (2.8) | −10.8 (2.3) | −9.1 (2.1) |

| 0.0001 | 0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| Color Vision | −2.4 (1.2) | −2.2 (1.2) | −1.5 (1.1) |

| 0.047 | 0.066 | 0.179 | |

| Peripheral Vision | −1.5 (1.4) | −1.4 (1.4) | −0.8 (1.4) |

| 0.299 | 0.338 | 0.561 | |

HVA is habitual visual acuity for better and worse-seeing eyes as two separate variables.

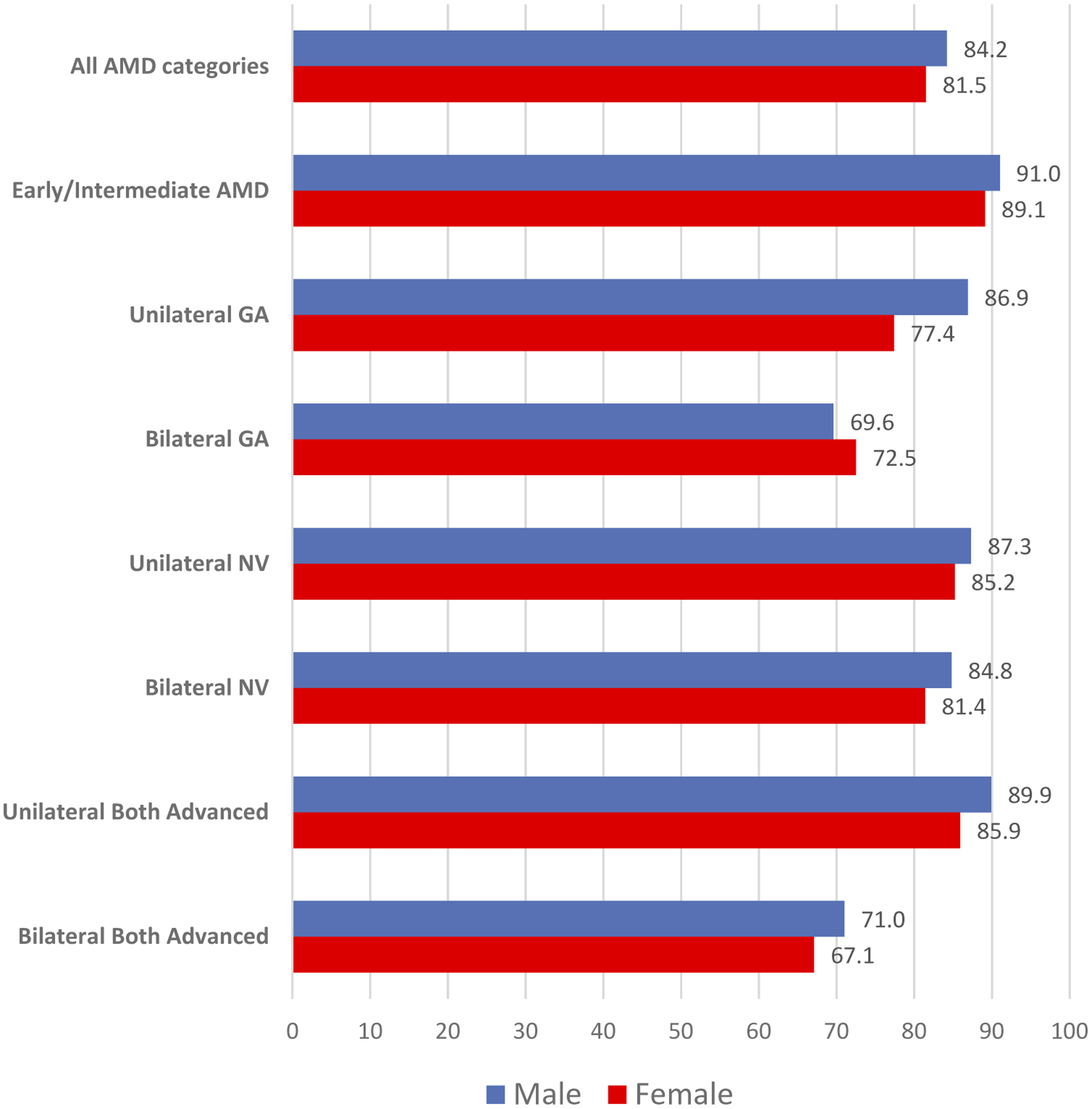

Although not statistically significant, Figure 1 demonstrates that female patients consistently reported lower VFQ-25 composite scores compared with male patients in each group, with the exception of patients with Bilateral GA. Figure 2, which presents VFQ-25 driving subscale scores by gender and AMD classification, indicates a similar pattern, with large differences between genders for all AMD groups. Although the gender differences in driving subscale scores were statistically significant for the entire cohort of AMD patients, when assessed by each AMD classification group, the sample sizes were too small to detect statistically significant differences. AMD groups with more than 100 patients (Early/Intermediate AMD, Unilateral NV, and Bilateral Both Advanced) did significantly differ by gender in the driving subscale scores (p = .004, p < .0001, and p = .037, respectively).

Figure 1.

VFQ-25 Composite Score by gender and AMD classification.

Figure 2.

VFQ-25 Driving Subscale Score by gender and AMD classification.

Discussion

In recent times, there has been an increasing emphasis on the consideration of gender as a variable in health research. The World Health Organization’s strategy for integrating gender analysis and actions into their work states, “Because of social (gender) and biological (sex) differences, women and men face different health risks, experience different responses from health systems, and their health-seeking behavior, and health outcomes differ.”33 Significant strides can be made in understanding these differences and addressing gender-based health inequalities through research elucidating the role that gender plays in health and disease.

There is also a growing recognition of the role of gender in visual functioning. Research from the past two decades indicates that men and women can be impacted differently by a wide range of ophthalmic conditions.34 The NEI VFQ-25 measures visual functioning among individuals with ophthalmic disorders and is frequently used among patients with AMD. Despite this, little is known about the effect of gender on visual functioning among AMD patients. To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine gender differences in overall visual functioning and vision-specific activities in patients with AMD, while distinguishing between AMD classification stage and number of eyes affected.

Age has been shown to be independently associated with NEI-VFQ scores. Among patients with AMD, an increase in age is associated with a decrease in NEI-VFQ subscale scores including dependency, role limitations, difficulty with near tasks, and mental health.35 This is likely influenced by the decline in general health and vision associated with older age, which may negatively impact patients’ abilities to perform such tasks. To minimize confounding, age, in addition to AMD classification, was included in our multivariable analyses, however, male and female patients did not differ by age so including age in our final model did not influence the final parameter estimates. Visual acuity and VFQ-25 scores have also been shown to be strongly associated36 and were so in our cohort as well. Visual acuity was measured at the same patient visit as administration of the VFQ-25 survey and the two measures both quantify visual functioning, although VA is more objective.

Results from one published study concluded that female gender was associated with experiencing a longitudinal decline in composite VFQ-25 scores among patients with GA and NV AMD,26 however, several other studies of patients with AMD found no significant differences in composite VFQ-25 scores between genders.25,27,28 Our study found a difference in composite scores between genders prior to adjusting for visual acuity, but this difference was not significant after adjustment for visual acuity. It is important to note that the sample sizes in these studies were far smaller than our study’s sample. It is also important to note that although statistically significant, the 2.2-point difference in NEI-VFQ-25 composite scores between genders does not represent a clinically meaningful difference. Previous AMD studies suggest that a difference ranging from 4 points to 10 points is clinically relevant and corresponds to a 15-letter change in visual acuity.37–39

Our study’s results illustrate that the largest gender differences are in regards to driving. Differences in our study were even larger than those reported in a prior study of patients with subfoveal choroidal neovascularization from AMD in which females on average reported 6.2 points lower than males for the NEI-VFQ driving subscale.27 In a study of pre-surgical cataract patients, a significantly greater percentage of women reported difficulty driving at night, difficulty driving in difficult conditions, and driving cessation, despite no gender differences in visual acuity.18 While women frequently cited poor eyesight as a reason for their decision to stop driving, men did not, suggesting that women are more likely to restrict their driving to accommodate vision dysfunction.18 Our results are also supported by the findings that female gender is significantly associated with driving restriction in patients with central vision loss,40 and greater driving difficulties in patients with keratoconus.19 One explanation is that overall, women report greater stress associated with difficult driving conditions,41 a higher perceived likelihood of getting into an accident,42 and greater avoidance of potentially risky driving situations compared to men.43 Female drivers are significantly more likely to give up, avoid, or make adaptations to driving compared to men.44–46 Overall, women also report less driving exposure than men46 and more frequently report inactive or infrequent driving patterns.47 Older men are more likely than older women to be the principal driver in the household,43 and males more frequently view the use of a private car as a necessity.41 Because women tend to drive less frequently and feel less need to drive, this may explain why they experience greater difficulties when driving and higher driving cessation rates. One study reports that driving cessation rates of older women with an active driving history are comparable to the driving cessation rates of older men, suggesting that driving patterns later in life are more closely linked with an individual’s driving history than their gender.44

Females also had lower scores than males in the subscale of ocular pain, signifying that they experience greater ocular pain and discomfort. This is consistent with a study of patients with NV AMD which found statistically significant gender differences in ocular pain, with females reporting lower than males.48 However, it differs from other studies, albeit with much smaller sample sizes, that have found no such gender differences.27,28 Female gender has also been associated with greater pain perception following intravitreal injections for NV AMD.49,50 Based on the existing literature, in general health women are at an increased risk for pain sensitivity and clinical pain.51 These differences may exist due to biological, psychological, and socio-cultural factors such as differences in sex hormones, the endogenous opioid system, and genotypes.52

This study supports a growing body of literature indicating gender differences in quality of life not only in ophthalmology, but also in several other fields of medicine. Women are more likely to experience functional impairment and diminished health-related quality of life compared to their male counterparts across a wide range of chronic conditions including HIV/AIDS,53 asthma,54 cardiac disease,55 colorectal cancer,56 and degenerative spine disease.57 A similar association has been observed in community-based studies of older adults, even after adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics and health-related variables.14,58 These findings reinforce the association between gender and health-related quality of life and highlight the need for further research that elucidates the factors driving these gender disparities.

The present study has several limitations. First, because the study has a cross-sectional design, as opposed to a longitudinal design, the patients’ changes in visual functioning and disease progression were not evaluated. The cross-sectional study design also means that although associations can be elucidated, casual inferences cannot be established. Another limitation of our study is the sample size, particularly when stratified by AMD classification. Based on published sample size estimate calculations, 1568 study participants would be required to detect two-point differences in VFQ-25 composite scores.20 While our study’s sample size is about half of this estimate, we were able to detect significant differences between genders for all AMD patients, but typically not when stratified by AMD classification. Our sample size is indeed larger than those used in prior studies on the topic, and likely explain why most prior studies did not identify significant gender differences. Additionally, the study sample was recruited from a single academic center, in which patients primarily identified as White, and therefore, our findings best represent gender differences among this population.

In summary, gender may play a role in reported functioning of driving and ocular pain among patients with AMD. This may need to be accounted for in future AMD studies that use VFQ-25 to assess visual functioning, particularly if gender is differential across study groups.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the University of Colorado Retina Research Group which includes the following list of contributors: Melanie Akau OD, Christopher, Karen L MD, Ruth T. Eshete MPH, C. Rob Graef OD, Anne M. Lynch MB, BCH, BAO, MSPH, Naresh Mandava MD, Niranjan Manoharan MD, Marc T. Mathias MD, Scott N. Oliver MD, Jeffery L. Olson MD, Alan G. Palestine MD, Jennifer L. Patnaik PhD, Jesse M. Smith MD, Brandie D. Wagner PhD.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health under grant number R01EY032456 (AML), a Research to Prevent Blindness challenge unrestricted grant to the Department of Ophthalmology, University of Colorado, and the Frederic C. Hamilton Macular Degeneration Center.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- 1.Chakravarthy U, Wong TY, Fletcher A, et al. Clinical risk factors for age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Ophthalmol. 2010;10:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-10-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pennington KL, DeAngelis MM. Epidemiology of age-related macular degeneration (AMD): associations with cardiovascular disease phenotypes and lipid factors. Eye Vis (Lond). 2016;3:34. doi: 10.1186/s40662-016-0063-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jager RD, Mieler WF, Miller JW. Age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(24):2606–2617. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0801537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fine SL, Berger JW, Maguire MG, Ho AC. Age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2000;342 (7):483–492. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002173420707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferris FL 3rd, Wilkinson CP, Bird A, et al. Clinical classification of age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(4):844–851.doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Institutes of Health. Consideration of sex as a biological variable in NIH-funded research. https://orwh.od.nih.gov/sites/orwh/files/docs/NOT-OD-15-102_Guidance.pdf. Published June 9, 2015. Accessed March 27, 2021.

- 7.Miller LR, Marks C, Becker JB, et al. Considering sex as a biological variable in preclinical research. FASEB J. 2017;31(1):29–34.doi: 10.1096/fj.201600781R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cornelison TL, Clayton JA. Article commentary: considering sex as a biological variable in biomedical research. Gend Genome. 2017;1(2):89–93. doi: 10.1089/gg.2017.0006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arnegard ME, Whitten LA, Hunter C, Clayton JA. Sex as a biological variable: a 5-year progress report and call to action. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2020;29 (6):858–864. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2019.8247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guallar-Castillón P, Sendino AR, Banegas JR, López-García E, Rodríguez-Artalejo F. Differences in quality of life between women and men in the older population of Spain. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(6):1229–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gallicchio L, Hoffman SC, Helzlsouer KJ. The relationship between gender, social support, and health-related quality of life in a community-based study in Washington County, Maryland. Qual Life Res. 2007;16 (5):777–786. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-9162-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orfila F, Ferrer M, Lamarca R, Tebe C, Domingo-Salvany A, Alonso J. Gender differences in health-related quality of life among the elderly: the role of objective functional capacity and chronic conditions. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63 (9):2367–2380. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu T, Enkh-Amgalan N, Zorigt G, Hsu Y-J, Chen H-J, Yang H-Y. Gender differences and burden of chronic conditions: impact on quality of life among the elderly in Taiwan. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2019;31(11):1625–1633. doi: 10.1007/s40520-018-1099-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hajian-Tilaki K, Heidari B, Hajian-Tilaki A. Are gender differences in health-related quality of life attributable to sociodemographic characteristics and chronic disease conditions in elderly people? Int J Prev Med. 2017;8:95. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_197_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brabyn JA, Schneck ME, Lott LA, Haegerström-Portnoy G. Night driving self-restriction: vision function and gender differences. Optom Vis Sci. 2005;82(8):755–764. doi: 10.1097/01.opx.0000174723.64798.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu M, Yu J, Zhang J, Yan Q, Liu Y. Evaluating vision-related quality of life in preoperative age-related cataract patients and analyzing its influencing factors in China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2015;15:160. doi: 10.1186/s12886-015-0150-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Esteban JJN, Martínez MS, Navalón PG, et al. Visual impairment and quality of life: gender differences in the elderly in Cuenca, Spain. Qual Life Res. 2008;17 (1):37–45.doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9280-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarkin AJ, Tally SR, Wooldridge JS, Choi K, Shieh M, Kaplan RM. Gender differences in adapting driving behavior to accommodate visual health limitations. J Community Health. 2013;38(6):1175–1181. doi: 10.1007/s10900-013-9730-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fink BA, Wagner H, Steger-May K, et al. Differences in keratoconus as a function of gender. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(3):459–468.doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.03.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mangione CM, Lee PP, Gutierrez PR, et al. Development of the 25-item National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119(7):1050–1058. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.7.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mangione CM. The National Eye Institute 25-Item Visual Function Questionnaire (VFQ-25): scoring algorithm with FAQ. https://www.nei.nih.gov/sites/default/files/2019-06/manual_cm2000.pdf. Published August 2000. Accessed March 22, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orr P, Rentz AM, Margolis MK, et al. Validation of the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire-25 (NEI VFQ-25) in age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(6):3354–3359. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Revicki DA, Rentz AM, Harnam N, Thomas VS, Lanzetta P. Reliability and validity of the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire-25 in patients with age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(2):712–717. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marella M, Pesudovs K, Keeffe JE, O’Connor PM, Rees G, Lamoureux EL. The psychometric validity of the NEI VFQ-25 for use in a low-vision population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(6):2878–2884. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chatziralli I, Mitropoulos P, Parikakis E, Niakas D, Labiris G. Risk factors for poor quality of life among patients with age-related macular degeneration. Semin Ophthalmol. 2017;32(6):772–780. doi: 10.1080/08820538.2016.1181192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahluwalia A, Shen LL, Del Priore LV. Central geographic atrophy vs. neovascular age-related macular degeneration: differences in longitudinal vision-related quality of life. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2021;259(2):307–316. doi: 10.1007/s00417-020-04892-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dong LM, Childs AL, Mangione CM, et al. Health- and vision-related quality of life among patients with choroidal neovascularization secondary to age-related macular degeneration at enrollment in randomized trials of submacular surgery: SST report no. 4. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138(1):91–108.doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schippert AC, Jelin E, Moe MC, Heiberg T, Grov EK. The impact of age-related macular degeneration on quality of life and its association with demographic data: results from the NEI VFQ-25 questionnaire in a Norwegian population. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2018;4:2333721418801601. doi: 10.1177/2333721418801601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williams RA, Brody BL, Thomas RG, Kaplan RM, Brown SI. The psychosocial impact of macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116(4):514–520. doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.4.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patnaik JL, Lynch AM, Pecen PE, et al. The impact of advanced age-related macular degeneration on the National Eye Institute’s visual function questionnaire-25. Acta Ophthalmol. 2020. doi: 10.1111/aos.14731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patnaik JL, Pecen PE, Hanson K, et al. Driving and visual acuity in patients with age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmol Retina. 2019;3(4):336–342. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2018.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lynch AM, Patnaik JL, Cathcart JN, et al. Colorado age-related macular degeneration registry: design and clinical risk factors of the cohort. Retina. 2019;39 (4):656–663.doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000002023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization. Strategy for integrating gender analysis and actions into the work of WHO. https://www.who.int/gender-equity-rights/knowledge/9789241597708/en/. Published March 2009. Accessed May 3, 2021.

- 34.Sex Eisner A., eyes, and vision: male/female distinctions in ophthalmic disorders. Curr Eye Res. 2015;40 (2):96–101. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2014.975368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cahill MT, Banks AD, Stinnett SS, Toth CA. Vision-related quality of life in patients with bilateral severe age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2005. Jan;112(1):152–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maguire M; Complications of Age-Related Macular Degeneration Prevention Trial Research Group. Baseline characteristics, the 25-item national eye institute visual functioning questionnaire, and their associations in the complications of age-related macular degeneration prevention trial (CAPT). Ophthalmology. 2004;111(7):1307–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suñer IJ, Kokame GT, Yu E, Ward J, Dolan C, Bressler NM. Responsiveness of NEI VFQ-25 to changes in visual acuity in neovascular AMD: validation studies from two phase 3 clinical trials. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50(8):3629–3635. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lindblad AS, Clemons TE. Responsiveness of the national eye institute visual function questionnaire to progression to advanced age-related macular degeneration, vision loss, and lens opacity: AREDS report no. 14. Arch Ophthal. 2005;123(9):1207–1214. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.9.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bressler NM, Chang TS, Fine JT, Dolan CM, Ward J; Anti-VEGF Antibody for the Treatment of Predominantly Classic Choroidal Neovascularization in Age-Related Macular Degeneration (ANCHOR) Research Group. Improved vision-related function after ranibizumab vs photodynamic therapy: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127 (1):13–21. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2008.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sengupta S, van Landingham SW, Solomon SD, Do DV, Friedman DS, Ramulu PY. Driving habits in older patients with central vision loss. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(3):727–732. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.09.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hakamies-Blomqvist L, Wahlström B. Why do older drivers give up driving? Accid Anal Prev. 1998;30 (3):305–312. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(97)00106-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Glendon AI, Dorn L, Davies DR, Matthews G, Taylor RG. Age and gender differences in perceived accident likelihood and driver competences. Risk Anal. 1996;16(6):755–762. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1996.tb00826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Charlton JL, Oxley J, Fildes B, et al. Characteristics of older drivers who adopt self-regulatory driving behaviours. Transp Res Part F Traffic Psychol Behav. 2006;9(5):363–373.doi: 10.1016/j.trf.2006.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anstey KJ, Windsor TD, Luszcz MA, Andrews GR. Predicting driving cessation over 5 years in older adults: psychological well-being and cognitive competence are stronger predictors than physical health. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(1):121–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carr DB, Flood K, Steger-May K, Schechtman KB, Binder EF. Characteristics of frail older adult drivers. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(7):1125–1129. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vance DE, Roenker DL, Cissell GM, Edwards JD, Wadley VG, Ball KK. Predictors of driving exposure and avoidance in a field study of older drivers from the state of Maryland. Accid Anal Prev. 2006;38 (4):823–831. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hakamies-Blomqvist L, Siren A. Deconstructing a gender difference: driving cessation and personal driving history of older women. J Safety Res. 2003;34 (4):383–388. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miskala PH, Bressler NM, Meinert CL. Relative contributions of reduced vision and general health to NEI-VFQ scores in patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(5):758–766. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.5.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haas P, Falkner-Radler C, Wimpissinger B, Malina M, Binder S. Needle size in intravitreal injections - pain evaluation of a randomized clinical trial. Acta Ophthalmol. 2016;94(2):198–202. doi: 10.1111/aos.12901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shin SH, Park SP, Kim YK. Factors associated with pain following intravitreal injections. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2018;32(3):196–203. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2017.0081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bartley EJ, Fillingim RB. Sex differences in pain: a brief review of clinical and experimental findings. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111(1):52–58. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Packiasabapathy S, Sadhasivam S. Gender, genetics, and analgesia: understanding the differences in response to pain relief. JPR. 2018;11:2729–2739. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S94650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mrus JM, Williams PL, Tsevat J, Cohn SE, Wu AW. Gender differences in health-related quality of life in patients with HIV/AIDS. Qual Life Res. 2005;14 (2):479–491. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-4693-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wijnhoven HAH, Kriegsman DMW, Snoek FJ, Hesselink AE, de Haan M. Gender differences in health-related quality of life among asthma patients. J Asthma. 2003;40(2):189–199. doi: 10.1081/jas-120017990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Emery CF, Frid DJ, Engebretson TO, et al. Gender differences in quality of life among cardiac patients. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(2):190–197.doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000116775.98593.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Laghousi D, Jafari E, Nikbakht H, Nasiri B, Shamshirgaran M, Aminisani N. Gender differences in health-related quality of life among patients with color-ectal cancer. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019;10(3):453–461. doi: 10.21037/jgo.2019.02.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gautschi OP, Corniola MV, Smoll NR, et al. Sex differences in subjective and objective measures of pain, functional impairment, and health-related quality of life in patients with lumbar degenerative disc disease. Pain. 2016;157(5):1065–1071.doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee KH, Xu H, Wu B. Gender differences in quality of life among community-dwelling older adults in lowand middle-income countries: results from the study on global AGEing and adult health (SAGE). BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):114. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-8212-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]