Summary

Background

By October 30, 2022, 76,871 cases of mpox were reported worldwide, with 20,614 cases in Latin America. This study reports characteristics of a case series of suspected and confirmed mpox cases at a referral infectious diseases center in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Methods

This was a single-center, prospective, observational cohort study that enrolled all patients with suspected mpox between June 12 and August 19, 2022. Mpox was confirmed by a PCR test. We compared characteristics of confirmed and non-confirmed cases, and among confirmed cases according to HIV status using distribution tests. Kernel estimation was used for exploratory spatial analysis.

Findings

Of 342 individuals with suspected mpox, 208 (60.8%) were confirmed cases. Compared to non-confirmed cases, confirmed cases were more frequent among individuals aged 30–39 years, cisgender men (96.2% vs. 66.4%; p < 0.0001), reporting recent sexual intercourse (95.0% vs. 69.4%; p < 0.0001) and using PrEP (31.6% vs. 10.1%; p < 0.0001). HIV (53.2% vs. 20.2%; p < 0.0001), HCV (9.8% vs. 1.1%; p = 0.0046), syphilis (21.2% vs. 16.3%; p = 0.43) and other STIs (33.0% vs. 21.6%; p = 0.042) were more frequent among confirmed mpox cases. Confirmed cases presented more genital (77.3% vs. 39.8%; p < 0.0001) and anal lesions (33.1% vs. 11.5%; p < 0.0001), proctitis (37.1% vs. 13.3%; p < 0.0001) and systemic signs and symptoms (83.2% vs. 64.5%; p = 0.0003) than non-confirmed cases. Compared to confirmed mpox HIV-negative, HIV-positive individuals were older, had more HCV coinfection (15.2% vs. 3.7%; p = 0.011), anal lesions (45.7% vs. 20.5%; p < 0.001) and clinical features of proctitis (45.2% vs. 29.3%; p = 0.058).

Interpretation

Mpox transmission in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, rapidly evolved into a local epidemic, with sexual contact playing a crucial role in its dynamics and high rates of coinfections with other STI. Preventive measures must address stigma and social vulnerabilities.

Funding

Instituto Nacional de Infectologia Evandro Chagas, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (INI-Fiocruz).

Keywords: Mpox, Outbreaks, STI, HIV, Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), Men who have sex with men, Latin America, Brazil, Public health

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

In Latin America, the first case of mpox was confirmed on May 13, 2022, in Mexico, and the first case in Brazil was reported on June 9. There were 20,614 confirmed cases in Latin America by October 28, 2022, of which 9162 were from Brazil, and eight of the 16 confirmed deaths in the Americas were from Brazil. Worldwide, Brazil ranked second in the number of confirmed cases of mpox and first in the number of deaths on November 4, 2022.

We searched PubMed using the terms (“monkeypox”) AND (“Latin America”) on October 30, 2022. We also reviewed the literature on research pertaining to mpox in other regions, with a particular focus on the description of case series during the 2022 outbreak. We found two manuscripts from international collaborative group of clinicians: one from 16 countries (N = 528), including cases from Argentina (n = 1) and Mexico (n = 1),1 and the second one from 15 countries (N = 211), also including a case from Argentina (n = 1).2 We retrieved six manuscripts reporting few case reports from Brazil and Mexico.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 However, none of these studies reported large case series from the Latin America region, revealing a gap on mpox publications in Latin America.

Added value of this study

This is the first case series report of mpox in Brazil. Our study is the first to compare epidemiological, sociodemographic, behavioral, clinical, and laboratory characteristics, including the prevalence of HIV and other ISTs for suspected and confirmed mpox cases. We compare characteristics of confirmed mpox cases according to HIV status. Furthermore, our cases are disaggregated by gender identity.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our results provide clinical and epidemiological data to inform clinicians on treatment and management of mpox patients, as well as governments and stakeholders to create effective public health policies regarding the most affected population groups in Latin America.

Introduction

Mpox is a zoonotic infection caused by the mpox virus (MPXV), an enveloped double-stranded DNA virus in the Orthopoxvirus genus of the Poxviridae family, which also includes variola and vaccinia viruses.9,10 The two distinct genetic MPXV clades, formerly known as Central African (or Congo Basin) and West African clades, were recently renamed Clade I and Clade II, respectively.11 The mean incubation period is 13 days (range 3–34). The virus replicates at the inoculation site and spreads to regional lymph nodes. Following a period of initial viremia, the virus spreads to other body organs. MPXV can be found in blood, semen, throat, rectum, and skin lesions.12 Symptoms usually include fever, myalgia, and lymphadenopathy followed by a centrifugally appearing “pox” rash, often with numerous lesions. The duration of symptoms is typically two to four weeks.13 These lesions progress through the vesiculopustular to ulcerative stage and then spontaneously resolve. In general, Clade II infections cause less severe disease than Clade 1.14

This emerging zoonotic agent was discovered in 1958 in Denmark among laboratory monkeys. The first human cases of mpox were reported in 197115 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and since then, human cases have mostly been reported in African countries.16, 17, 18 Outside Africa, the first cases were reported in 2003 in the United States, also likely to be due to animal-to-human transmission.14 Since early May 2022, several mpox cases have been reported in countries where the disease is not endemic. This multi-country outbreak has rapidly spread throughout the world14,19, 20, 21 and thus triggered significant concerns, including a potential for sexual transmission based on detection of viral DNA in sexual fluids in addition to the previously known transmission routes throughout endemic African countries or the imported or travel related cases reported since 2003.22 This scenario has led WHO to declare the current mpox outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) on July 23, 2022.

Worldwide, 76,871 cases of mpox were reported by October 30, 2022, from 109 countries, resulting in 36 deaths.23 This new outbreak, mostly concentrated among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (MSM)91, seems to be characterized by a milder course than previously reported outbreaks. Although initially phylogenetic analysis of MPXV sequences associated with the 2022 worldwide outbreak cluster (lineage B.1) suggested they belong in a new clade, there is still an ongoing debate regarding a possible subclade of clade II or an independent clade III.9,24,25

A systematic review with meta-analysis of hospitalizations, complications, and deaths related to mpox was carried out on June 7, 2022, including observational studies, case reports, and case series without language or time restrictions. A total of 12 quantitative studies involving 1958 patients were analyzed, confirming that rash (93%, 95%CI 80–100%) and fever (72%, 95%CI 30–99%) were most frequently reported symptoms, followed by pruritus (65%, 95%CI 47–81%) and lymphadenopathy (62%, 95%CI 47–76%). Approximately 35% of patients (95%CI 14–59%) were hospitalized, of which 5% had fatal outcomes (95%CI 1–9%).26

In Latin America, the first case was confirmed on May 13 in Mexico,6 and the first case in Brazil was reported on June 9.5,27 Of the 20,614 confirmed cases in Latin America by October 28, 9162 were from Brazil28; 11 of the 18 deaths confirmed in the Americas were also from Brazil by November 4, 2022. Worldwide, Brazil ranks second in number of confirmed cases of MPXV and first in number of deaths by November 4, 2022. A bibliometric analysis study showed that Latin America has a greater gap in mpox research than the rest of the world, with fewer publications of original studies.29

This study aims to report baseline sociodemographic, behavior, clinical and laboratory characteristics of a case series of suspected and confirmed mpox cases evaluated and followed at a referral center, the Evandro Chagas National Institute of Infectious Diseases (INI)-Fiocruz, in Brazil. This is the first study to report a mpox case series in Brazil, despite the high number of cases observed in the country. Moreover, we also report suspected cases and differences between suspected and confirmed cases, data which none of the case series from other regions have included.

Methods

Study design and participants

In this single center, prospective, observational cohort study we enrolled all consecutive patients with suspected mpox from June 12 to August 19, 2022, who had their final case definition by August 21 at INI-Fiocruz, the major referral center for Infectious Diseases in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. As such, INI-Fiocruz has become a pillar in the Brazilian response against mpox, providing diagnosis and care to potential and confirmed cases and establishing a mpox cohort.

At baseline, we offered MPXV PCR testing to all participants with suspected infection. A confirmed case of mpox was defined as a positive result on real-time PCR of skin lesion, anal, or oropharynx swab specimens.

All individuals with a mpox diagnosis had follow-up visits scheduled at days 3–5 and 21, for a total of at least two planned follow-up visits within 21 days (or until full resolution of skin lesions, if longer), which could be performed through telemedicine. Interim visits were scheduled as needed. At each visit, patients were evaluated for potential signs of complications, symptomatic contacts, clinical or laboratory signs of other sexually transmitted infections (STI), as well as duration of isolation.

Procedures

We prospectively collected sociodemographic, epidemiological, behavior, clinical (presentation and outcome) and laboratory data onto a standardized case report form using Redcap. Information on date of birth, gender identity and race according to Brazilian standard classification,30 education level,31 sexual history in the previous 30 days, including sexual intercourse, anal sex and sexual contact with a potential mpox case and HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use were assessed. Smallpox vaccination was compulsory in Brazil until 1975, with universal coverage through the Brazilian Ministry of Health Immunization Program. For these analyses, we considered those born before 1975 as vaccinated for smallpox.

For people living with HIV (PLWH), we assessed the most recent CD4 count cells/mm3, HIV viral load and antiretroviral therapy (ART) regimen, which data was obtained from the clinical charts and from the Brazilian Antiretroviral Logistics database (SICLOM). For all hospitalized cases we collected information on reason for admission, use of intravenous antibiotics, intensive support care use and hospitalization outcome.

The cutaneous rash variable was split into two categories: localized and disseminated. Localized cases were those presenting rash on one segment (head/neck, trunk, trunk, pelvis, upper limbs, or lower limbs), while disseminated cases referred to rash on two or more segments. Self-reported complaints of tenesmus and/or anal pain were considered clinical signs of proctitis. Signs of secondary bacterial infection considered those cases in which the medical doctor had prescribed any antibiotics to treat skin infections, or clearly described the presence of phlogistic signs in skin lesions.

PCR testing was performed for case confirmation at the Mpox Reference Laboratory at the Oswaldo Cruz Institute (IOC)-Fiocruz. Skin lesion, anal, and oropharynx swabs were collected. MPXV DNA was detected by a specific mpox qPCR protocol described by LI Y et al.32 in a AB 7500 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystem).

A comprehensive sexual health screen was offered to all individuals, including HIV testing, which was performed according to the Brazilian Ministry of Health algorithm. Moreover, HIV RNA was performed for all individuals aiming to diagnose potential cases of acute HIV infection.

A rapid Treponema pallidum (TP) test was performed for syphilis screening and positive results were confirmed using nontreponemal tests (venereal disease research laboratory [VDRL]) at enrollment. Active/recent syphilis at enrollment was defined as titers equal to or higher than 1:8 and a positive micro-hemagglutination assay for T. pallidum (MHA-TP).

Rectal swabs for chlamydia (Chlamydia trachomatis) and gonorrhea (Neisseria gonorrhoeae) detection were collected at enrollment and testing was conducted using the Abbott Real Time platform. Hepatitis B and hepatitis C were investigated at enrollment using hepatitis B surface antibody and anti-HCV rapid test, respectively. For patients with positive anti-HCV rapid test, only those who had not reported previous HCV infection or treatment were considered as a newly diagnosed HCV infection.

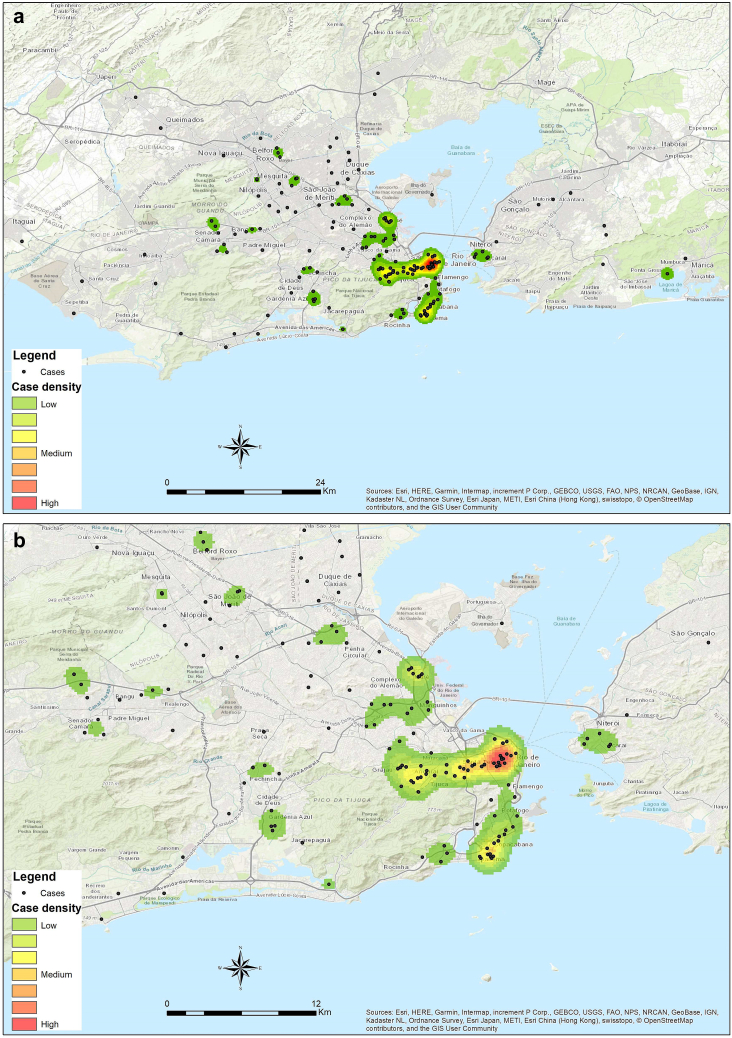

Spatial analysis

We conducted an exploratory analysis based on the Kernel estimator, with a radius of 2 km and Gaussian function, to obtain an overview of the spatial distribution of mpox confirmed cases and identify hot spots of occurrence. The zip codes of the cases were considered for georeferencing. This analysis was performed using functions from the Spatial Analyst module in ArcGis 10.4.

Statistical analysis

We compared sociodemographic, behavior, clinical and laboratory characteristics according to mpox diagnosis (confirmed vs. non-confirmed). Among confirmed mpox cases, we compared study characteristics according to HIV status (negative vs. positive). For such comparisons, we used chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test for qualitative variables and Mann–Whitney test for quantitative variables. All analyses were performed using R software version 4.2.1 (www.r-project.com).

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Board at INI-Fiocruz (CAAE # 61290422.0.0000.5262). All study participants provided either oral or written informed consent to participate. Written consent for images were obtained as well. Individuals who required hospitalization were prospectively followed at the INI-Fiocruz Inpatient care Unit. If hospitalization occurred outside our institution, data were retrospectively collected.

Role of the funding source

The funding body (INI-Fiocruz) was involved in all steps of study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Between June 12 and August 19, 2022, a total of 342 individuals with suspected human MPXV infection sought medical care at INI-Fiocruz. Of those, 208 (60.8%) were confirmed cases (Fig. 1), representing 49.3% of all cases reported to the Rio de Janeiro State surveillance system by August 19, 2022.33 Among individuals with confirmed mpox, median age was 33 years (IQR: 28, 38), most were black or Pardo (69.5%) and had post-secondary education (61.8%). The majority were cisgender men (96.2%), and among them 89.7% were MSM.

Fig. 1.

Kernel density maps ofmpoxcasesby August 19, 2022,inINI-Fiocruz,Rio de Janeiro, Brazil,for confirmed cases (1a) and hot spots (1b).

Compared to non-confirmed cases, confirmed mpox cases were more frequent among individuals aged 30–39 years (30–39 years: 47.1% vs. 31.3%; p < 0.0001), cisgender men (96.2% vs. 66.4%; p < 0.0001), MSM (89.7% vs. 56.9%; p < 0.0001), and less frequent among those vaccinated for smallpox (8.2% vs. 17.9%; p = 0.011). More mpox confirmed cases reported sexual intercourse in the previous 30 days (95.0% vs. 69.4%; p < 0.0001), anal sex (44.1% vs. 22.2%; p < 0.0001) and sexual contact with a potential mpox case (22.4% vs. 11.7%; p = 0.051) (Table 1). Among the confirmed mpox cases, the lesion swab PCR yielded the highest positivity rate (lesion swab 96.3%, rectal swab 77.2%, oropharyngeal swab 64% - Supplementary Table S1).

Table 1.

Socio demographic and behavior characteristics of the study population according to mpox diagnosis at first medical assessment (N = 342).

| Confirmed (n = 208; 60.8%) n/total (%) |

Non-confirmed (n = 134; 39.2%) n/total (%) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 33 (28, 38) | 32 (25, 40) | 0.20a |

| <18 | 1/208 (0.5) | 5/134 (3.7) | <0.0001b |

| 18–24 | 19/208 (9.1) | 28/134 (20.9) | |

| 25–29 | 45/208 (21.6) | 24/134 (17.9) | |

| 30–39 | 98/208 (47.1) | 42/134 (31.3) | |

| ≥40 | 45/208 (21.6) | 35/134 (26.1) | |

| Gender identity | <0.0001b | ||

| Cisgender men | 200/208 (96.2) | 89/134 (66.4) | |

| Cisgender women | 8/208 (3.8) | 43/134 (32.1) | |

| Transgender women | 0/208 (0.0) | 2/134 (1.5) | |

| Travesti | 0/208 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | |

| Non-binary | 0/208 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | |

| MSM | <0.0001c | ||

| Yes | 156/174 (89.7) | 41/72 (56.9) | |

| No | 18/174 (10.3) | 31/72 (43.1) | |

| Race | 0.16b | ||

| Black | 57/144 (39.6) | 28/85 (32.9) | |

| Pardo (mixed) | 43/144 (29.9) | 25/85 (29.4) | |

| White | 43/144 (29.9) | 29/85 (34.1) | |

| Asian | 0/144 (0.0) | 3/85 (3.5) | |

| Indigenous | 1/144 (0.7) | 0/85 (0.0) | |

| Education | 0.56c | ||

| Primary | 7/152 (4.6) | 7/88 (8.0) | |

| Secondary | 51/152 (33.6) | 28/88 (31.8) | |

| Post-secondary | 94/152 (61.8) | 53/88 (60.2) | |

| Traveld | 0.89c | ||

| Yes | 39/168 (23.2) | 25/101 (24.8) | |

| No | 129/168 (76.8) | 76/101 (75.2) | |

| Vaccinated for smallpoxe | 0.011c | ||

| Yes | 17/208 (8.2) | 24/134 (17.9) | |

| No | 191/208 (91.8) | 110/134 (82.1) | |

| Live in the same household of suspected/confirmedmpoxcase | 0.92c | ||

| Yes | 11/146 (7.5) | 8/91 (8.8) | |

| No | 135/146 (92.5) | 83/91 (91.2) | |

| Sex worker | 1.00b | ||

| Yes | 4/165 (2.4) | 2/109 (1.8) | |

| No | 161/165 (97.6) | 107/109 (98.2) | |

| Sexual intercoursed | <0.0001c | ||

| Yes | 170/179 (95.0) | 75/108 (69.4) | |

| No | 9/179 (5.0) | 33/108 (30.6) | |

| Anal sexd,f | <0.0001c | ||

| Yes | 79/179 (44.1) | 24/108 (22.2) | |

| No | 100/179 (55.9) | 84/108 (77.8) | |

| Sexual contact with a potentialmpoxcased,f | 0.051c | ||

| Yes | 35/156 (22.4) | 11/94 (11.7) | |

| No | 121/156 (77.6) | 83/94 (88.3) |

Mann–Whitney test.

Fisher's exact test.

Chi-squared test.

Previous 30 days.

Individuals born before 1975.

Only individuals who reported sexual intercourse.

HIV infection was more frequent among confirmed mpox cases (53.2% vs. 20.2%; p < 0.0001). Two individuals were diagnosed as HIV + at mpox assessment; one HIV acute infection was detected. Among individuals with HIV negative status, PrEP use was more common among those with confirmed mpox (31.6% vs. 10.1%; p < 0.0001). Among all individuals with a positive anti-HCV rapid test (n = 18), eight (44%) reported no previous knowledge of hepatitis C diagnosis and were considered to be diagnosed with hepatitis C at mpox assessment. HCV infection was higher in mpox confirmed cases (9.8% vs. 1.1%; p = 0.0046). Gonorrhea (9.9%) and/or chlamydia (10.6%), and/or active syphilis (21.2%) were diagnosed in 33.0% of confirmed mpox cases (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical and laboratory characteristics of the study population according to mpox diagnosis at first medical assessment (N = 342).

| Confirmed (n = 208; 60.8%) n/total (%) |

Non-confirmed (n = 134; 39.2%) n/total (%) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV infection | 109/205 (53.2) | 25/124 (20.2) | <0.0001c |

| Time of HIV diagnosis | 0.16d | ||

| Previously diagnosed | 107/109 (98.2) | 23/25 (92.0) | |

| Diagnosed at mpox assessment | 2/109 (1.8) | 2/25 (1.5) | |

| PrEP usea | <0.0001c | ||

| Yes | 31/89 (31.6) | 11/99 (10.1) | |

| No | 58/89 (59.2) | 88/99 (80.7) | |

| HBV infection | 0.54d | ||

| Yes | 2/158 (98.7) | 0/85 (0.0) | |

| No | 156/158 (98.7) | 85/85 (100.0) | |

| HCV Infectionb | 17/173 (9.8) | 1/93 (1.1) | 0.0046d |

| Time of HCV diagnosis | 0.44d | ||

| Previously diagnosed | 10/17 (58.8) | 0/1 (0.0) | |

| Diagnosed at mpox assessment | 7/17 (41.2) | 1/1 (100.0) | |

| Active syphilis | 0.43c | ||

| Yes | 36/170 (21.2) | 15/92 (16.3) | |

| No | 134/170 (78.8) | 77/92 (83.7) | |

| Gonorrhea | 0.096d | ||

| Yes | 14/141 (9.9) | 2/69 (2.9) | |

| No | 127/141 (90.1) | 67/69 (97.1) | |

| Chlamydia | 1.00c | ||

| Yes | 15/141 (10.6) | 7/69 (10.1) | |

| No | 126/141 (89.4) | 62/69 (90.0) | |

| Any STIe | 0.042c | ||

| Yes | 60/182 (33.0) | 22/102 (21.6) | |

| No | 122/182 (67.0) | 80/102 (78.4) | |

| Days between first symptoms and clinical assessment | 0.57f | ||

| Median (IQR) | 5 (4, 8) | 5 (3, 10) | |

| Systemic signs and symptomsg | 0.0003c | ||

| Yes | 158/190 (83.2) | 78/121 (64.5) | |

| No | 32/190 (16.8) | 43/121 (35.6) | |

| Cutaneous rash | 0.0080c | ||

| Localized | 47/197 (23.9) | 47/122 (38.5) | |

| Disseminated | 150/197 (76.1) | 75/122 (61.5) | |

| Genital lesionsh | <0.0001c | ||

| Yes | 150/194 (77.3) | 49/123 (39.8) | |

| No | 44/194 (22.7) | 74/123 (60.2) | |

| Anal lesions | <0.0001c | ||

| Yes | 59/178 (33.1) | 13/113 (11.5) | |

| No | 119/178 (66.9) | 100/113 (88.5) | |

| Clinical features of proctitis | <0.0001c | ||

| Yes | 66/178 (37.1) | 15/113 (13.3) | |

| No | 112/178 (62.9) | 98/113 (86.7) | |

| Signs of secondary bacterial infection | 0.51c | ||

| Yes | 7/147 (4.8) | 8/106 (7.5) | |

| No | 140/147 (95.2) | 98/106 (92.5) | |

| Deaths | 0/208 (0.0) | 0/134 (0.0) |

Only HIV negative individuals.

PCR confirmation for anti-HCV positive cases is ongoing.

Chi-squared test.

Fisher's exact test.

At least one sexually transmitted infection: gonorrhea, chlamydia, or syphilis.

Mann–Whitney test.

Reported at least one sign or symptom (fever, asthenia, myalgia, headache, sore throat, adenomegaly).

Excluding anal/perianal lesions.

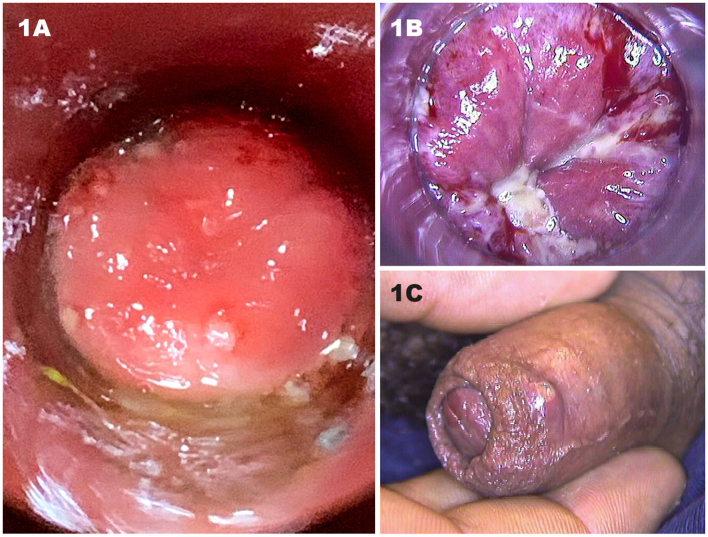

Clinical presentation varied greatly according to the stages of mpox at the time of testing (Supplementary Figs. S1–S7). Confirmed mpox cases presented more genital and anal lesions than non-confirmed cases (77.3% vs. 39.8%; p < 0.0001 and 33.1% vs. 11.5%; p < 0.0001, respectively). Clinical features of proctitis were noted more in mpox confirmed cases (37.1 vs. 13.3%; p < 0.0001) (Table 2).

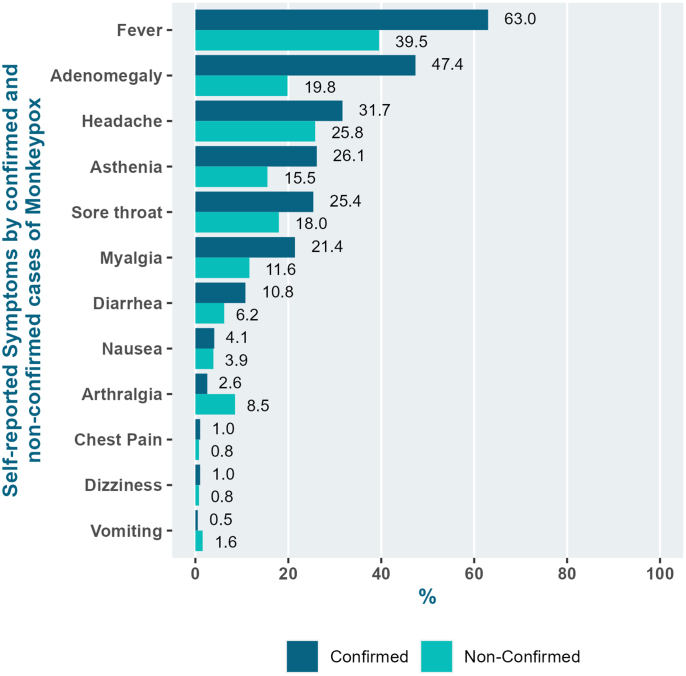

Presence of at least one systemic sign or symptom attributable to the invasive phase of the illness was common among all participants (75.9%). Compared to non-confirmed cases, more confirmed mpox cases presented systemic signs and symptoms (83.2% vs. 64.5%; p = 0.0003) (Table 2): fever (63.0% vs. 39.5%; p < 0.0001), adenomegaly (47.4% vs. 19.8%; p < 0.0001), asthenia (26.1% vs. 15.5%; p = 0.023) and myalgia (21.4% vs. 11.6%; p = 0.023. Arthralgia was reported by more non-confirmed cases (2.6% vs. 8.5%; p = 0.015) than mpox confirmed cases (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Clinical symptoms according tompoxdiagnosis (%).

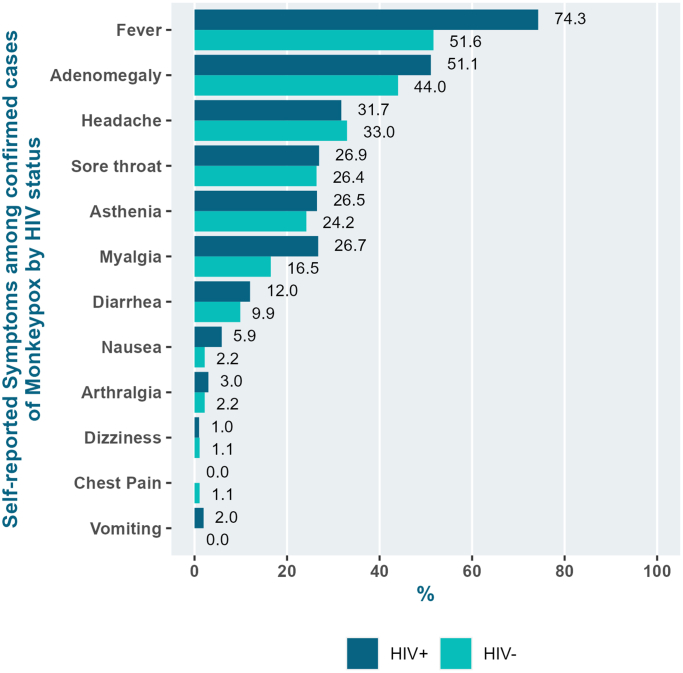

Compared to HIV-negative individuals with confirmed mpox, PLWH were older (30–39 years: 51.4% vs. 42.7%; ≥40 years: 25.7% vs. 16.7%; p < 0.0001), more self-identified as Pardo (37.2% vs. 21.2%; p = 0.019) and white (32.1% vs. 27.3%; p = 0.019), more diagnosed with HCV (15.2% vs. 3.7%; p = 0.011) and active syphilis (28.7% vs 11.8%; p = 0.013). Moreover, anal lesions (45.7% vs. 20.5%; p < 0.0001), clinical features of proctitis (45.2% vs. 29.3%; p = 0.058) (Table 3), and fever (74.3% vs. 51.6%; p = 0.0010) were more frequent among PLWH (Fig. 3). Among PLWH with mpox (N = 109), median CD4 cell count was 527.5 cells/mm3 (IQR: 379.5, 826.7), 90.8% had undetectable HIV viral load and 75.2% were using an INSTI-based ART regimen (Table 4).

Table 3.

Socio demographic, clinical and laboratory characteristics of confirmed mpox cases according to HIV Infection (N = 205).

| HIV+ (n = 109; 53.2%) n/total (%) |

HIV- (n = 96; 46.8%) n/total (%) |

Total (n = 205)a | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years (%) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 34 (30, 40) | 31 (25, 37.5) | 33 (28, 38) | 0.012b |

| <18 | 0/109 (0.0) | 0/95 (0.0) | 0/205 (0.0) | <0.0001c |

| 18–24 | 4/109 (3.7) | 15/95 (15.6) | 19/205 (9.3) | |

| 25–29 | 21/109 (19.3) | 24/95 (25.0) | 45/205 (22.0) | |

| 30–39 | 56/109 (51.4) | 41/95 (42.7) | 97/205 (47.3) | |

| ≥40 | 28/109 (25.7) | 16/95 (16.7) | 44/205 (21.5) | |

| Gender identity | 0.098c | |||

| Cisgender men | 108/109 (99.1) | 91/95 (94.8) | 199/205 (97.1) | |

| Cisgender women | 1/109 (0.9) | 5/95 (5.2) | 6/205 (2.9) | |

| Race | 0.019c | |||

| Black | 23/79 (29.5) | 34/65 (51.5) | 57/144 (27.8) | |

| Pardo (mixed) | 29/79 (37.2) | 14/65 (21.2) | 43/144 (21.0) | |

| White | 25/79 (32.1) | 18/65 (27.3) | 43/144 (21.0) | |

| Indigenous | 1/79 (1.3) | 0/65 (0.0) | 1/144 (0.5) | |

| HBV Infection | 0.502c | |||

| Yes | 2/87 (2.3) | 0/71 (0.0) | 2/158 (1.0) | |

| No | 85/87 (97.7) | 71/71 (100.0) | 156/158 (76.1) | |

| HCV Infectione | 0.011c | |||

| Yes | 14/92 (15.2) | 3/80 (3.7) | 17/172 (9.8) | |

| No | 78/92 (84.7) | 78/80 (96.3) | 156/172 (90.7.) | |

| Active syphilis | 0.013d | |||

| Yes | 27/94 (28.7) | 9/76 (11.8) | 36/170 (17.6) | |

| No | 67/94 (71.3) | 67/76 (88.2) | 134/170 (65.4) | |

| Gonorrhea | 0.40d | |||

| Yes | 5/65 (7.7) | 9/76 (11.8) | 14/141 (9.9) | |

| No | 60/65 (92.3) | 67/76 (88.2) | 127/141 (90.1) | |

| Chlamydia | 1.00d | |||

| Yes | 8/76 (10.5) | 7/65 (10.8) | 15/141 (10.6) | |

| No | 68/76 (89.5) | 58/65 (89.2) | 126/141 (89.4) | |

| Any STIf | 0.020d | |||

| Yes | 40/99 (40.4) | 20/83 (24.1) | 60/182 (33.0) | |

| No | 59/99 (59.6) | 63/83 (75.9) | 122/182 (67.0) | |

| Days between first symptoms and clinical assessment | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 6 (4, 10) | 5 (3, 8) | 5 (4, 8) | 0.03b |

| Systemic signs and symptomsg | 0.038d | |||

| Yes | 93/103 (90.3) | 64/84 (76.2) | 157/187 (84.0) | |

| No | 10/103 (9.7) | 20/84 (23.8) | 8/187 (16.0) | |

| Cutaneous rash | 0.12d | |||

| Localized | 20/105 (19.2) | 25/89 (27.8) | 45/194 (22.0) | |

| Disseminated | 84/105 (80.8) | 65/89 (72.2) | 149/194 (72.7) | |

| Genital lesionsh | 0.11d | |||

| Yes | 84/102 (83.2) | 66/89 (73.3) | 150/191 (73.2) | |

| No | 17/102 (16.8) | 24/89 (26.7) | 41/191 (20.0) | |

| Anal lesions | <0.0001d | |||

| Yes | 42/93 (45.7) | 17/82 (20.5) | 59/175 (28.8) | |

| No | 50/93 (54.3) | 66/82 (79.5) | 116/175 (56.6) | |

| Clinical features of proctitis | 0.058d | |||

| Yes | 42/94 (45.2) | 24/81 (29.3) | 66/175 (32.2) | |

| No | 51/94 (54.8) | 58/81 (70.7) | 109/175 (53.2) | |

| Signs of secondary bacterial infection | 0.71c | |||

| Yes | 3/76 (4.0) | 4/68 (5.8) | 7/144 (3.4) | |

| No | 72/76 (96.0) | 65/68 (94.2) | 137/144 (66.8) |

Three missing HIV status among mpox confirmed patients.

Mann–Whitney test.

Fisher's exact test.

Chi-squared test.

PCR confirmation for anti-HCV positive cases is ongoing.

At least one sexually transmitted infection: gonorrhea, chlamydia, or syphilis.

Reported at least one sign or symptom (fever, asthenia, myalgia, headache, sore throat, adenomegaly).

Excluding anal/perianal lesions.

Fig. 3.

Self-reported clinical symptoms amongconfirmedmpoxcases according to HIV status (%).

Table 4.

Most recent laboratory and ART regimen among people living with HIV with confirmed mpox (N = 109).

| HIV+ (n = 109) | |

|---|---|

| CD4 count cells/mm3 – Median (IQR) | 527.5 (379.5, 826.7) |

| HIV viral load | |

| Undetectable (<50 copies/ml) | 79/87 (90.8%) |

| Detectable | 8/87 (9.2%) |

| <40 copies/ml | 77/87 (88.5%) |

| 41–200 copies/ml | 5/87 (5.7%) |

| >200 copies/ml | 5/87 (5.87%) |

| ART regimen | 109/109 (100.0%) |

| INSTI-based | 82/109 (75.2%) |

| PI-based | 18/109 (16.5%) |

| NNRTI-based | 9/109 (8.3%) |

INSTI, Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitor; NNRTI, Non-Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor.

By July 21, 2022, 7.6% of all individuals with suspected mpox (26/342) had been hospitalized, and most of them were confirmed as mpox cases (19/26; 73.0%) (Table 5). Among the confirmed mpox cases, the hospitalization rate was 9.1% (19/208). Other diagnoses included varicella (n = 2), skin and soft tissue infection (n = 1), disseminated herpes simplex (HSV) infection (n = 1), hemorrhoidal thrombosis (n = 1), Sweet syndrome (n = 1), and drug hypersensitivity (n = 1). Among hospitalized confirmed cases, all were cisgender men and median age of 31 years (IQR: 29, 41). The most common reasons for admission were pain control (n = 11), bacterial superinfection (n = 3) and paraphimosis (n = 3). Intravenous antibiotics were administered for eight patients and only one required intensive care support with vasoactive drugs and mechanical ventilation. All paraphimosis cases were resolved after manual reduction performed by a urologist specialist, with no surgical interventions required. There were no registered deaths of suspected mpox patients in this case series.

Table 5.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of hospitalized suspect and confirmed mpox cases.

| ID | Age (years) | Race | Gender Identity | Reason for admission | Diagnosis | Intravenous Antibiotics (Y/N) | Hospitalization outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30 | NA | Cisgender Men | Paraphimosis and pain control | mpox | Y | Currently hospitalized |

| 2 | 29 | Pardo | Cisgender Men | Bacterial superinfection | mpox | Y | Discharged |

| 3 | 52 | NA | Cisgender Men | Bacterial superinfection and pain control | mpox | Y | Currently hospitalized |

| 4 | 26 | White | Cisgender Men | Clinical investigation | mpox | Y | Discharged |

| 5 | 31 | Pardo | Cisgender Men | Clinical investigation | mpox | N | Discharged |

| 6 | 42 | Pardo | Cisgender Men | Inability to self-isolate | mpox | N | Discharged |

| 7 | 51 | White | Cisgender Men | Mediastinitisb | mpox | Y | Currently hospitalizeda |

| 8 | 24 | NA | Cisgender Men | Pain control | mpox | N | Discharged |

| 9 | 37 | Pardo | Cisgender Men | Pain control | mpox | N | Currently hospitalized |

| 10 | 35 | Pardo | Cisgender Men | Pain control | mpox | N | Discharged |

| 11 | 30 | NA | Cisgender Men | Pain control | mpox | Y | Discharged |

| 12 | 31 | Black | Cisgender Men | Pain control | mpox | Y | Discharged |

| 13 | 29 | NA | Cisgender Men | Pain control | mpox | N | Discharged |

| 14 | 37 | Black | Cisgender Men | Bacterial superinfection and pain control | mpox | Y | Discharged |

| 15 | 29 | Pardo | Cisgender Men | Pain control and Inability to self-isolate | mpox | N | Discharged |

| 16 | 25 | Black | Cisgender Men | Pain control | mpox | N | Discharged |

| 17 | 28 | Black | Cisgender Men | Paraphimosis | mpox | N | Discharged |

| 18 | 32 | White | Cisgender Men | Paraphimosis | mpox | N | Discharged |

| 19 | 30 | Pardo | Cisgender Men | Sustained fever | mpox | N | Discharged |

| 20 | 29 | NA | Cisgender Men | Bacterial superinfection | Varicella | Y | Discharged |

| 21 | 44 | NA | Cisgender Women | Clinical investigation | Sweet syndrome | N | Discharged |

| 22 | 31 | Black | Cisgender Women | Clinical investigation | Drug hypersensitivity | N | Discharged |

| 23 | 59 | White | Cisgender Men | Clinical investigation | Skin and soft tissue infection | Y | Discharged |

| 24 | 21 | NA | Cisgender Men | Clinical investigation | Varicella | N | Discharged |

| 25 | 48 | Black | Cisgender Men | Inability to self-isolate | Hemorrhoidal thrombosis | N | Discharged |

| 26 | 50 | White | Cisgender Men | Seizures | Probable disseminated HSV infection with bacterial superinfection | Y | Currently hospitalizeda |

HSV, herpes simplex virus; NA, not available; N, No; Y,Yes.

Required intensive support care. Patient still hospitalized as of August 21, 2022.

Primary case under investigation.

Discussion

In this study we report sociodemographic, behavior, clinical and laboratory data of 208 confirmed mpox cases in Brazil, the first case series to our knowledge reported in Latin America. We also provide information on non-confirmed suspected cases to explore potential factors associated with mpox, and comparisons of confirmed mpox cases according to HIV status.

Sociodemographic and behavioral aspects

Our findings showed that most cases were concentrated in MSM, aged 30 to 39 year-old, similar to other case series.1,19,21,34, 35, 36, 37, 38 Such older age pattern differs from the current dynamics of other STIs, such as syphilis, chlamydia, gonorrhea, and HIV in Latin America, more prevalent among younger MSM aged <30 years.39, 40, 41 A potential explanation is that these older individuals were more frequently linked to PrEP and HIV care services, and, therefore, had better access to health services and mpox diagnosis. Alternatively, other factors could play a role such as differences on sexual networks, attended venues and number of partners according to age.42 Nevertheless, there is still a significant gap on the knowledge of sexual networks among sexual and gender minority populations in Brazil.

Most published studies on mpox cases included at least 99% of cisgender men, while 3% of our cases were in cisgender women, and this might increase with further community transmission. By October 8, 2022, 8.3% of mpox cases were reported in those who self-declared as female sex assigned at birth,43 reinforcing the importance of a comprehensive public debate on this topic. During this analysis timeframe, no cases among non-binary, travesti and transgender women were assessed at our clinic, despite our health unit being a referral service for sexual health, HIV prevention and care for these populations.44, 45, 46 However, we reported the first case of mpox in a transgender woman on September 7, 2022,47 almost three months after the first mpox diagnosis in Rio de Janeiro. As few studies so far have provided disaggregated information by gender identity, the actual burden of mpox among sexual and gender minority populations remains unknown. However, a Spanish cohort showed no infections among transgender women, and official data from the United States Centers of Diseases Control showed that transgender women contributed to less than 1% of cases.37,48 This might be related to the different sexual networks of MSM and transgender women and these paths not critically involved in the dynamics of MPXV transmission.

Transmission dynamics in Brazil

Mpox was confirmed in Brazil for the first time on June 9, 2022, in a 41-year-old man who had travelled to Portugal and Spain. The first mpox case in Rio de Janeiro State was confirmed by our service on June 14, 2022 in an individual who arrived in Brazil from London, United Kingdom, on June 11, 2022. Soon after this case, community MPXV transmission was identified. MPXV infections in Brazil are sharply increasing, the country has registered the first death outside an endemic country, and currently ranks first in mpox related-deaths wordwidely.8

Our exploratory spatial analysis points out to two main hotspots, in neighborhoods located relatively close to each other, possibly related to highly connected sexual networks and the broad use of dating apps.49 Moreover, there were cases identified in other municipalities outside the Metropolitan area. Sociodemographic analysis shows that mpox cases were mainly composed of white cisgender men in the initial weeks, but the proportion of cases among black or Pardo individuals has gradually increased, accounting for the majority of cases so far (see Supplementary Material, Fig. S8), mirroring the profile of the Rio de Janeiro State population. Furthermore, travel history was not associated to mpox diagnosis, suggesting that MPXV local transmission in Rio de Janeiro has rapidly evolved.

Prevalence of concomitant STIs

Our cases presented with considerable more frequency of concomitant STIs compared to case series from other countries, especially active syphilis and HCV infection.1,36,37,50 These findings underscore the importance of STI screening during the assessment of mpox suspected cases, presenting an opportunity to identify cases and initiate adequate treatments51 and highlighting the well-established fact that having an STI amplifies the risk of acquiring additional STIs,52 reinforcing the need for comprehensive sexual health services.51

HIV prevalence among confirmed mpox cases in our cohort was similar to other studies (24%–50%), and most of PLWH had suppressed viral load and median CD4 cells counts superior to 500 cells per mm3.1,19,21,34, 35, 36, 37, 38,51 During our baseline assessment we diagnosed four new cases of HIV infection, including one case of acute HIV infection which is, to the best of our knowledge, the first case reported in Latin America. This individual developed no mpox-related complications, differing from a previous case reported in Portugal with severe mpox lesions.53

PrEP use

Just few studies provided information on PrEP use, widely varying from 19.7% to 95%, possibly biased by initial site of assessment, for instance sexual health clinics.1,9,19,21,34,54,55 Our data show that, among mpox cases, only 31.6% of HIV negative individuals were on PrEP, highly inferior to high-income settings in Europe, such as the United Kingdom and France.9,19,34 Although PrEP use in Brazil accounts for the largest proportion of PrEP users in Latin America and has expanded during 2021–2022,56 it is far behind the projected PrEP coverage needed.57

Clinical features and hospitalizations

Our findings were similar to the clinical syndrome reported during the current 2022 mpox outbreak in non-endemic countries, with most patients developing a different clinical course from that previously described in endemic countries,15, 16, 17 notably with a predominance of anogenital lesions.1,19,21,34,36,37,48,50 In our case series, proctitis was reported more frequently, which might be partially explained by the high rate of STI coinfections.1,21,37 In agreement with other studies, systemic symptoms were not a universal finding, thus case definitions must include patients who present only with cutaneous and/or mucosal manifestations. In addition, in our study, consistent with previous analysis, 25% of confirmed cases had a localized rash frequently involving only genital and/or perianal area.1,19,21,36,37,48,50,58 Together, these data highlight the importance of a thorough clinical examination and detailed medical history while considering mpox as a differential diagnosis.

Our manuscript is one of the first to compare the clinical presentation between HIV positive and negative cases with confirmed MPXV infection. The majority of PLWH were virologically suppressed and none had advanced immunosuppression at mpox diagnosis. PLWH showed higher rates of STI coinfections as well as anal lesions and proctitis, in line with previous findings from a multicentric study.2 This is of concern, since active mpox lesions might potentially increase HIV transmission in the context of unsuppressed viral load, which outlines the importance of the Undetectable = Untransmissible (U=U) message dissemination and reinforcement of ART adherence.59 In our case series, HIV coinfection did not appear to imply a more severe mpox disease, and mucocutaneous-related complications were observed regardless of HIV status. Nevertheless, none of our patients had advanced immunosuppression, in line with most evidence published so far.2,53,60, 61, 62, 63 However, mpox cases with severe immunosuppression require attention, as a recent case series report of hospitalized mpox patients in the United States showed severe immunosuppression might be related to higher hospitalization rates and worse clinical outcomes.64

Despite its benign course, mpox might be associated with complications such as cutaneous sepsis, encephalitis, keratitis, disabling pain and other less common complications such as paraphimosis.50,65 During the course of our study, 9.1% of confirmed mpox cases received inpatient care, a relatively high proportion compared to that reported in other countries varying from 2% to 13%.1,21,34, 35, 36, 37,65 Most admissions were related to pain control, and have largely not required intensive care support. Two cases were admitted due to inability to self-isolate, but only one was confirmed with MPXV infection. There were three cases of paraphimosis, a complication recently described,50 that might require urgent evaluation by an urologist specialist.

Other relevant aspects

This case series highlights the importance of systematic monitoring of patients diagnosed with mpox after initial consultation, as the clinical course lasts about three weeks and may lead to a need for specialists to deal with complications. Adequate patient follow-up requires a strong organization of health systems, including telemedicine evaluations to allow monitoring of potential complications that might require a specialist. While health systems face a major burden due to this emergency, they must restructure appropriate responses to guarantee a continuum of care, with rapid linkage to specialized care whenever needed. Finally, the fact that some people required hospitalization to guarantee self-isolation due to the high habitants-to-rooms ratio at home exposes the serious social inequalities in Brazil and raises concerns about a possible role of household transmission in the mpox outbreak dynamics.

Despite the absence of specific therapeutic alternatives for mpox, drugs with proven experimental efficacy and potential clinical impact such as tecovirimat or cidofovir (especially its lipid conjugate, brincidofovir) are not widely available in Brazil. Furthermore, although in some countries MPX vaccination has been implemented for individuals under higher risk for MPXV infection and contacts of positive cases, at this stage, no anti-smallpox vaccines are available in Brazil. No preventive measures have been implemented in the country so far, which might impact on transmission dynamics. Hurdles that prevent people from adequately following home isolation guidance, such as impossibility of missing work for a prolonged number of days, risk of food insecurity and the high number of individuals cohabitating in small households may also have contributed to increase community transmission.

As a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic, Brazil has increased its molecular testing capacity and has established laboratory networks that share genomic surveillance data, resulting in better preparedness against other emerging threats such as the current mpox outbreak. Our study confirmed the reliability of mucocutaneous lesion swab samples for MPXV detection as the gold standard for diagnostics.66 However, it is important to note that testing specimens from multiple sites may improve diagnostic sensitivity and reduce false-negative test results.67

Nevertheless, despite most cases of mpox presenting as a mild disease, it might bring an additional burden on an already fragile public health system, especially after the last two and half years of the COVID-19 pandemic and recent cuts in the Ministry of Health's budget.

There is also an important need for healthcare workers' education on the many clinical and epidemiological aspects of mpox, allowing for proper differential diagnosis, especially in the context of the syphilis epidemic, which highly affects the most vulnerable to MPXV infection.68 Similarly, it is important to develop standardized protocols to guide pain control management, as well as to timely identify potential complications.

Limitations

This study has limitations. Although we reported cases from a single health care unit, our sample represents 49.3% of all mpox cases reported in Rio de Janeiro State and has a similar profile compared to this population.33 Nevertheless, Brazil and the Latin American region more broadly face different vulnerabilities that might impact the disease's epidemiological and clinical course. Still, this case series is a first step in building up knowledge and evidence on how this region might be impacted by this outbreak.

Conclusions

This is the first study to describe sociodemographic, behavioral, and clinical aspects of the current mpox outbreak in Latin America. Mpox has been endemic in some countries of Africa for more than forty years and was considered a neglected tropical disease. After its spread, initially in Europe and North America and quickly escalating to a global level, it was declared a public health emergency. Currently, the region of Americas is the epicenter of this outbreak, with Brazil accounting for a considerable proportion of the cases and the largest number of deaths worldwide.

Our findings point to an extremely relevant role of sexual contact in the transmission dynamics of mpox in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, highlighting the importance of a comprehensive sexual health screening while evaluating suspected cases. Special attention needs to be given to the stigma and discrimination related to the mpox epidemic, as it mostly affects MSM, who already face homophobia, which is deeply entangled in the Brazilian society. Strengthening links with the community and building bridges, as well as increasing community education on mpox with clear and stigma free messaging, are critical. Conversely, our study suggests that mpox dynamics in Rio de Janeiro rapidly evolved into a local epidemic, and community transmission might further increase if no preventive measures are implemented.

Several efforts are ongoing to mitigate the impacts of this outbreak, such as expansion of vaccination strategies, and design of clinical trials to evaluate efficacy of antiviral treatments. In this context, considering socioeconomic disparities across different regions and providing an equitable distribution of these technologies are essential steps while structuring a robust global health response for this emergence. Despite its relatively benign clinical course, mpox might pose an extra burden for health services in the global south, especially in the context of socioeconomic vulnerabilities and AIDS epidemics.

Contributors

MSTS, MDW, VGV, and BG conceived this study. MSTS, CC, TST, and BG conceived and supervised the current analysis and manuscript preparation. MSTS, EP, RIM, FL, and MAM performed data acquisition and statistical analyses. MSTS, ADEG, MOB, ICFT, MPDR, MRMSR, HBA, APLS, JBSN, PR, and JBSN performed clinical evaluations, and SN, EES, and LASR laboratory evaluation supervision. EPN, BH, APLS, MS-O, LV, and SWC were involved in revising the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

INI-Fiocruz Mpox study group

André Miguel Japiassu, Marcel Trepow, Italo Guariz Ferreira, Larissa Villela, Rafael Teixeira Fraga, Mariah Castro de Souza Pires, Rodrigo Otavio da Silva Escada, Leonardo Paiva de Sousa, Gabriela Lisseth Umaña Robleda, Desirée Vieira Santos, Luiz Ricardo Siqueira Camacho, Pedro Amparo, João Victor Jaegger de França, Felipe de Oliveira Heluy Correa, Bruno Ivanovinsky Costa de Sousa, Bernardo Vicari do Valle, João Paulo Bortot Soares, Livia Cristina Fonseca Ferreira, Pedro da Silva Martins, Maira Braga Mesquita, José Ricardo Hildebrant Coutinho, Raissa de Moraes Perlingeiro, Priscila Peixoto de Castro Oliveira, Hugo Perazzo Pedroso Barbosa, André Figueiredo Accetta, Marcelo Cunha, Rosangela Vieira Eiras, Ticiana Martins dos Santos, Wladmyr Davila da Silva, Monique do Vale Silveira, Tania de Souza Brum, Guilherme Amaral Calvet, Rodrigo Caldas Menezes, Sandro Antônio Pereira.

Data sharing statement

A complete de-identified dataset sufficient to reproduce the primary study findings will be made available upon request to the corresponding author, following approval of a concept sheet summarizing the analyses to be done.

Editor note

The Lancet Group takes a neutral position with respect to territorial claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Declaration of interests

All authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all study participants, as well as Heberth de Araujo, Adriana Julio, Barbara Viggiani, Mauro Derrico, Katia Derrico, Alexandre Luiz Mariano de Souza, Luciane de Souza Kunz Barbosa, Renato Jorge Gomes da Silva, Katia Caroline Lira Silva, Andressa Jorge Pedro Marciano, Guilherme Ferreira for data checking and Giselle Moreira, Amanda Almeida and Glaucia Motta for nursing assistance.

Funding:Instituto Nacional de Infectologia Evandro Chagas, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2022.100406.

Contributor Information

Beatriz Grinsztejn, Email: gbeatriz@ini.fiocruz.br.

The INI-Fiocruz Mpox Study Group:

André Miguel Japiassu, Marcel Trepow, Italo Guariz Ferreira, Larissa Villela, Rafael Teixeira Fraga, Mariah Castro de Souza Pires, Rodrigo Otavio da Silva Escada, Leonardo Paiva de Sousa, Gabriela Lisseth Umaña Robleda, Desirée Vieira Santos, Luiz Ricardo Siqueira Camacho, Pedro Amparo, João Victor Jaegger de França, Felipe de Oliveira Heluy Correa, Bruno Ivanovinsky Costa de Sousa, Bernardo Vicari do Valle, João Paulo Bortot Soares, Livia Cristina Fonseca Ferreira, Pedro da Silva Martins, Maira Braga Mesquita, José Ricardo Hildebrant Coutinho, Raissa de Moraes Perlingeiro, Priscila Peixoto de Castro Oliveira, Hugo Perazzo Pedroso Barbosa, André Figueiredo Accetta, Marcelo Cunha, Rosangela Vieira Eiras, Ticiana Martins dos Santos, Wladmyr Davila da Silva, Monique do Vale Silveira, Tania de Souza Brum, Guilherme Amaral Calvet, Rodrigo Caldas Menezes, and Sandro Antônio Pereira

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Fig. S1.

Fig. S2.

Fig. S3.

Fig.S4.

Fig.S5.

References

- 1.Thornhill J.P., Barkati S., Walmsley S., et al. Monkeypox virus infection in humans across 16 countries — April–June 2022. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(8):679–691. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2207323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angelo K.M., Smith T., Camprubí-Ferrer D., et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of patients with monkeypox in the GeoSentinel Network: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00651-X. S147330992200651X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brites C., Deminco F., Sá M.S., Brito J.T., Luz E., Stocker A. The first two cases of monkeypox infection in MSM in Bahia, Brazil, and viral sequencing. Viruses. 2022;14(9):1841. doi: 10.3390/v14091841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martins-Filho P.R., de Souza M.F., Oliveira Góis M.A., et al. Unusual epidemiological presentation of the first reports of monkeypox in a low-income region of Brazil. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2022;50 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2022.102466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Lima E.L., Barra L.A.C., Borges L.M.S., et al. First case report of monkeypox in Brazil: clinical manifestations and differential diagnosis with sexually transmitted infections. Rev Inst Med trop S Paulo [Internet] 2022;64 doi: 10.1590/S1678-9946202264054. https://www.scielo.br/j/rimtsp/a/PsVw9gQSWvvzB4NfVY3hPvC/?lang=en# [citado 3 de novembro de 2022]; Disponível em: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pérez-Barragán E., Pérez-Cavazos S. First case report of human monkeypox in Latin America: the beginning of a new outbreak. J Infect Pub Health. 2022;15(11):1287–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2022.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carvalho L.B., Casadio L.V.B., Polly M., et al. Monkeypox virus transmission to healthcare worker through needlestick injury, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 2022;28(11):2334–2336. doi: 10.3201/eid2811.221323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Menezes Y.R., de Miranda A.B. Severe disseminated clinical presentation of monkeypox virus infection in an immunosuppressed patient: first death report in Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2022;55:e0392–e2022. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0392-2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gessain A., Nakoune E., Yazdanpanah Y. Monkeypox. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(19):1783–1793. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2208860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parker S., Nuara A., Buller R.M.L., Schultz D.A. Human monkeypox: an emerging zoonotic disease. Future Microbiol. 2007;2(1):17–34. doi: 10.2217/17460913.2.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.W.H.O. Monkeypox: experts give virus variants new names [Internet] 2022. https://www.who.int/news/item/12-08-2022-monkeypox--experts-give-virus-variants-new-names [citado 6 de setembro de 2022]. Disponível em:

- 12.Noe S., Zange S., Seilmaier M., et al. Clinical and virological features of first human monkeypox cases in Germany. Infection [Internet] 2022 doi: 10.1007/s15010-022-01874-z. https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s15010-022-01874-z [citado 22 de julho de 2022]; Disponível em: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar S., Subramaniam G., Karuppanan K. Human monkeypox outbreak in 2022. J Med Virol. 2022;30 doi: 10.1002/jmv.27894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bunge E.M., Hoet B., Chen L., et al. The changing epidemiology of human monkeypox—a potential threat? A systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022;16(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0010141. Gromowski G, organizador. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ladnyj I.D., Ziegler P., Kima E. A human infection caused by monkeypox virus in Basankusu Territory, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Bull World Health Organ. 1972;46(5):593–597. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.von Magnus P., Andersen E.K., Petersen K.B., Birch-Andersen A. A pox-like disease in cynomolgus monkeys. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 2009;46(2):156–176. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heberling R.L., Kalter S.S. Induction, course, and transmissibility of monkeypox in the baboon (Papio cynocephalus) J Infect Dis. 1971;124(1):33–38. doi: 10.1093/infdis/124.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonilla-Aldana D.K., Rodriguez-Morales A.J. Is monkeypox another reemerging viral zoonosis with many animal hosts yet to be defined? Vet Q. 2022;42(1):148–150. doi: 10.1080/01652176.2022.2088881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Girometti N., Byrne R., Bracchi M., et al. Demographic and clinical characteristics of confirmed human monkeypox virus cases in individuals attending a sexual health centre in London, UK: an observational analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22(9):1321–1328. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00411-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orviz E., Negredo A., Ayerdi O., et al. Monkeypox outbreak in Madrid (Spain): clinical and virological aspects. J Infect. 2022;85(4):412–417. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2022.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iñigo Martínez J., Gil Montalbán E., Jiménez Bueno S., et al. Monkeypox outbreak predominantly affecting men who have sex with men, Madrid, Spain, 26 April to 16 June 2022. Euro Surveill. 2022;27(27) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2022.27.27.2200471. https://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2022.27.27.2200471 [Internet]. Disponível em: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reed K.D., Melski J.W., Graham M.B., et al. The detection of monkeypox in humans in the Western Hemisphere. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(4):342–350. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.WHO Monkeypox data [internet] 2022. https://extranet.who.int/publicemergency/# [citado 6 de setembro de 2022]. Disponível em:

- 24.Isidro J., Borges V., Pinto M., et al. Phylogenomic characterization and signs of microevolution in the 2022 multi-country outbreak of monkeypox virus. Nat Med. 2022;28(8) doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01907-y. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-022-01907-y [citado 22 de julho de 2022]; Disponível em: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luna N., Ramírez A.L., Muñoz M., et al. Phylogenomic analysis of the monkeypox virus (MPXV) 2022 outbreak: emergence of a novel viral lineage? Trav Med Infect Dis. 2022;49 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2022.102402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benites-Zapata V.A., Ulloque-Badaracco J.R., Alarcon-Braga E.A., et al. Clinical features, hospitalisation and deaths associated with monkeypox: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2022;21(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s12941-022-00527-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brasil, Ministério da Saúde Brasil confirma primeiro caso de monkeypox [Internet] 2022. https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/canais-de-atendimento/sala-de-imprensa/notas-a-imprensa/2022/brasil-confirma-primeiro-caso-de-monkeypox [citado 6 de setembro de 2022]. Disponível em:

- 28.PAHO. Monkeypox cases - Region of the Americas [Internet]. Disponível em: https://shiny.pahobra.org/monkeypox/; 2022.

- 29.Lozada-Martinez I.D., Fernández-Gómez M.P., Acevedo-Lopez D., Bolaño-Romero M.P., Picón-Jaimes Y.A., Moscote-Salazar L.R. What has been researched on monkeypox in Latin America? A brief bibliometric analysis. Trav Med Infect Dis. 2022;49 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2022.102399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.IBGE Censo Demográfico [internet] 2022. https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/sociais/populacao/9662-censo-demografico-2010.html?edicao=10503&t=destaques [citado 6 de setembro de 2022]. Disponível em:

- 31.UNESCO International standard classification of education (ISCED) [internet] 2022. https://uis.unesco.org/en/topic/international-standard-classification-education-isced [citado 9 de setembro de 2022]. Disponível em:

- 32.Li Y., Zhao H., Wilkins K., Hughes C., Damon I.K. Real-time PCR assays for the specific detection of monkeypox virus West African and Congo Basin strain DNA. J Virol Methods. 2010;169(1):223–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brasil, Ministério da Saúde Card Situação epidemiológica de Monkeypox no Brasil no 32 [internet] 2022. https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/composicao/svs/resposta-a-emergencias/coes/monkeypox/atualizacao-dos-casos/card-situacao-epidemiologica-de-monkeypox-no-brasil-ndeg-32-se-33-19-08-22/view [citado 6 de setembro de 2022]. Disponível em:

- 34.Mailhe M., Beaumont A.L., Thy M., et al. Clinical characteristics of ambulatory and hospitalised patients with monkeypox virus infection: an observational cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2022.08.012. S1198743X22004281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perez Duque M., Ribeiro S., Martins J.V., et al. Ongoing monkeypox virus outbreak, Portugal, 29 April to 23 may 2022. Eurosurveillance. 2022;27(22) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2022.27.22.2200424. https://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2022.27.22.2200424 [citado 22 de julho de 2022] Disponível em: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tarín-Vicente E.J., Alemany A., Agud-Dios M., et al. Clinical presentation and virological assessment of confirmed human monkeypox virus cases in Spain: a prospective observational cohort study. Lancet. 2022;400(10353):661–669. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01436-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Català A., Clavo Escribano P., Riera J., et al. Monkeypox outbreak in Spain: clinical and epidemiological findings in a prospective cross-sectional study of 185 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187(5):765–772. doi: 10.1111/bjd.21790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control/WHO Regional Office for Europe . World Health Organization; 2022. Monkeypox, Joint Epidemiological overview [Internet]https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/librariesprovider2/monkeypox/monkeypox_euro_ecdc_draft_jointreport_2022-08-31.pdf?sfvrsn=d43ae2a1_3&download=true Disponível em: [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coelho L.E., Torres T.S., Veloso V.G., et al. The prevalence of HIV among men who have sex with men (MSM) and young MSM in Latin America and the Caribbean: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(10):3223–3237. doi: 10.1007/s10461-021-03180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Veloso V.G. Evidence for PrEP implementation in Latin America: ImPrEP project results. 2022. https://conference.aids2022.org/media-2269-evidence-for-prep-implementation-in-latin-america-imprep-project-results [citado 6 de setembro de 2022]. Disponível em:

- 41.Veloso V.G., Moreira R.I., Konda K., et al. PrEP long-term engagement among MSM and TGW in Latin America: the ImPrEP Study. 2022. https://www.croiconference.org/abstract/prep-long-term-engagement-among-msm-and-tgw-in-latin-america-the-imprep-study/ [citado 6 de setembro de 2022]. Disponível em:

- 42.Guimarães M.D.C., Kendall C., Magno L., et al. Comparing HIV risk-related behaviors between 2 RDS national samples of MSM in Brazil, 2009 and 2016. Medicine. 2018;97:S62–S68. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000009079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ministério da Saúde . Ministério da Saúde; 2022. Boletim Epidemiológico Especial de Monkeypox n 15 (25/09/2022 a 08/10/2022) [Internet]https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/centrais-de-conteudo/publicacoes/boletins/epidemiologicos/variola-dos-macacos/boletim-epidemiologico-de-monkeypox-no-15-coe/view [citado 31 de outubro de 2022]. Disponível em: [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferreira A.C.G., Coelho L.E., Jalil E.M., et al. Transcendendo: a cohort study of HIV-infected and uninfected transgender women in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Transgend Health. 2019;4(1):107–117. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2018.0063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jalil E.M., Torres T.S., Luz P.M., et al. Low PrEP adherence despite high retention among transgender women in Brazil: the PrEParadas study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2022;25(3) doi: 10.1002/jia2.25896. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jia2.25896 [citado 5 de setembro de 2022]. Disponível em: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Torres T.S., Jalil E.M., Coelho L.E., et al. A technology-based intervention among young men who have sex with men and nonbinary people (the Conectad@s project): protocol for A vanguard mixed methods study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2022;11(1) doi: 10.2196/34885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Silva M.S.T., Jalil E.M., Torres T.S., et al. Monkeypox and transgender women: the need for a global initiative. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2022;50 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2022.102479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Philpott D., Hughes C.M., Alroy K.A., et al. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of monkeypox cases — United States, May 17–July 22, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(32):1018–1022. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7132e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gibson L.P., Kramer E.B., Bryan A.D. Geosocial networking app use associated with sexual risk behavior and pre-exposure prophylaxis use among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men: cross-sectional web-based survey. JMIR Form Res. 2022;6(6) doi: 10.2196/35548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Patel A., Bilinska J., Tam J.C.H., et al. Clinical features and novel presentations of human monkeypox in a central London centre during the 2022 outbreak: descriptive case series. BMJ. 2022;28 doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-072410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Curran K.G. HIV and sexually transmitted infections among persons with monkeypox — eight U.S. Jurisdictions, may 17–July 22, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71 doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7136a1. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/71/wr/mm7136a1.htm [citado 9 de setembro de 2022]; Disponível em: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gandhi M., Spinelli M.A., Mayer K.H. Addressing the sexually transmitted infection and HIV Syndemic. JAMA. 2019;321(14):1356–1358. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.2945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.de Sousa D., Patrocínio J., Frade J., Correia C., Borges-Costa J., Filipe P. Human monkeypox coinfection with acute HIV: an exuberant presentation. Int J STD AIDS. 2022;33(10):936–938. doi: 10.1177/09564624221114998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hoffmann C., Jessen H., Wyen C., et al. Clinical characteristics of monkeypox virus infections among men with and without HIV : a large outbreak cohort in Germany. HIV Med. 2022;4 doi: 10.1111/hiv.13378. hiv.13378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Palich R., Burrel S., Monsel G., et al. Viral loads in clinical samples of men with monkeypox virus infection: a French case series. Lancet infect Dis. 2022 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00586-2. S1473309922005862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brasil, Ministério da Saúde Painel PrEP [internet] 2022. https://www.gov.br/aids/pt-br/assuntos/prevencao-combinada/prep-profilaxia-pre-exposicao/painel-prep [citado 6 de setembro de 2022]. Disponível em:

- 57.Luz P.M., Benzaken A., de Alencar T.M., Pimenta C., Veloso V.G., Grinsztejn B. PrEP adopted by the brazilian national health system: what is the size of the demand? Medicine (Baltim) 2018;97(1S Suppl 1):S75–S77. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hammerschlag Y., MacLeod G., Papadakis G., et al. Monkeypox infection presenting as genital rash, Australia. Euro Surveill. 2022 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2022.27.22.2200411. https://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2022.27.22.2200411 [citado 22 de julho de 2022];27(22). Disponível em: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Torres T.S., Cox J., Marins L.M., et al. A call to improve understanding of Undetectable equals Untransmittable (U = U) in Brazil: a web-based survey. J Intern AIDS Soc. 2020;23(11) doi: 10.1002/jia2.25630. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jia2.25630 [citado 5 de setembro de 2022]. Disponível em: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brazão C., Garrido P.M., Alpalhão M., et al. Monkeypox virus infection in HIV-1-coinfected patients previously vaccinated against smallpox: a series of 4 cases from Portugal. Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;20 doi: 10.1111/jdv.18655. jdv.18655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fischer F., Mehrl A., Kandulski M., Schlosser S., Müller M., Schmid S. Monkeypox in a patient with controlled HIV infection initially presenting with fever, painful pharyngitis, and tonsillitis. Medicina. 2022;58(10):1409. doi: 10.3390/medicina58101409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Betancort-Plata C., Lopez-Delgado L., Jaén-Sanchez N., et al. Monkeypox and HIV in the canary islands: a different pattern in a mobile population. TropicalMed. 2022;7(10):318. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed7100318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vaughan A.M., Cenciarelli O., Colombe S., et al. A large multi-country outbreak of monkeypox across 41 countries in the WHO European Region, 7 March to 23 August 2022. Euro Surveill. 2022;27(36) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2022.27.36.2200620. https://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2022.27.36.2200620 [citado 4 de novembro de 2022]. Disponível em: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Miller M.J., Cash-Goldwasser S., Marx G.E., et al. Severe monkeypox in hospitalized patients — United States, August 10–october 10, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(44):1412–1417. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7144e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moschese D., Giacomelli A., Beltrami M., et al. Hospitalisation for monkeypox in milan, Italy. Trav Med Infect Dis. 2022;49 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2022.102417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nörz D., Brehm T.T., Tang H.T., et al. Clinical characteristics and comparison of longitudinal qPCR results from different specimen types in a cohort of ambulatory and hospitalized patients infected with monkeypox virus. J Clin Virol. 2022;155 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2022.105254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Veintimilla C., Catalán P., Alonso R., et al. The relevance of multiple clinical specimens in the diagnosis of monkeypox virus, Spain. Euro Surveill. 2022;27(33) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2022.27.33.2200598. https://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2022.27.33.2200598 [citado 21 de agosto de 2022] Disponível em: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tsuboi M., Evans J., Davies E.P., et al. Prevalence of syphilis among men who have sex with men: a global systematic review and meta-analysis from 2000–20. Lancet Global Health. 2021;9(8):e1110–e1118. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00221-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.