Summary

Background

Climate change is increasing the risks of injuries, diseases, and deaths globally. However, the association between ambient temperature and renal diseases has not been fully characterized. This study aimed to quantify the risk and attributable burden for hospitalizations of renal diseases related to ambient temperature.

Methods

Daily hospital admission data from 1816 cities in Brazil were collected during 2000 and 2015. A time-stratified case-crossover design was applied to evaluate the association between temperature and renal diseases. Relative risks (RRs), attributable fractions (AFs), and their confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to estimate the associations and attributable burden.

Findings

A total of 2,726,886 hospitalizations for renal diseases were recorded during the study period. For every 1°C increase in daily mean temperature, the estimated risk of hospitalization for renal diseases over lag 0–7 days increased by 0·9% (RR = 1·009, 95% CI: 1·008–1·010) at the national level. The associations between temperature and renal diseases were largest at lag 0 days but remained for lag 1–2 days. The risk was more prominent in females, children aged 0–4 years, and the elderly ≥ 80 years. 7·4% (95% CI: 5·2–9·6%) of hospitalizations for renal diseases could be attributable to the increase of temperature, equating to 202,093 (95% CI: 141,554–260,594) cases.

Interpretation

This nationwide study provides robust evidence that more policies should be developed to prevent heat-related hospitalizations and mitigate climate change.

Funding

China Scholarship Council, and the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council

Keywords: Temperature, hospitalization, renal disease, case-crossover study, climate change

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We searched Pubmed without any language restrictions for articles published from inception to Dec 31, 2020, using the following search terms: “temperature” or “heat”, “renal disease” or “kidney disease”, “daily”, and “short-term”. We then manually selected relavant articles by reading the abstracts and full texts. Existing studies were relatively small, making them unable to evaluate whether the association varies by sex, age, region, and diseases type. More importantly, current studies were mainly conducted in developed countries and few in developing countries, and the health burden of renal diseases attributable to temperature has not been fully understood in low- and middle-income countries like Brazil.

Added value of this study

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in Brazil and the largest study in the world evaluating the association between ambient temperature and hospitalizations for renal diseases. Using a time-stratified case-crossover design, our study showed that the risk of hospitalizations for renal diseases was positively associated with daily mean temperature. We also found 7·4% of total hospitalizations could be attributed to the increase of ambient temperature and children aged 0–4 years were more vulnerable.

Implications of all the available evidence

In the context of global warming, more strategies and policies should be developed to prevent heat-related hospitalizations. Our findings suggest that there should be a significant association between ambient temperature and hospitalization for renal diseases. The results show that interventions should be promoted by targeting specific individuals, including females, children, adolescents, and the elderly, as they are more vulnerable to heat with regard to renal diseases. Moreover, attention should be paid to low- and middle-income countries like Brazil, where reliable heat warning systems and preventive measures are still in need.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Introduction

Despite being the most neglected chronic diseases,1 renal diseases, including acute kidney injury (AKI) and chronic kidney disease (CKD), have been recognized as a global public health concern.2 It was estimated that 2·59 million deaths, 0·613 million disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) were attributable to impaired kidney function in 2017, showing a 26·6% and 20·3% increase from 2007, respectively.3 In Brazil, renal diseases have also become a great health burden. It was estimated that the overall prevalence of CKD was over 6·7% and the cost spending for renal dialysis has more than doubled from US$340 million in 2000 to US$713 million in 2009 in Brazil.4,5

Climate change characterized by temperature rise is increasing the risks of injuries, diseases, and deaths. It was estimated that 92,207 and 255,486 additional deaths can be attributed to the increase of temperature in 2030 and 2050, respectively.6 Heat-induced sweating and following dehydration are believed to play a vital role in the development of temperature-related renal diseases.7,8 Some studies have suggested that the increase of temperature may increase the risk of emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalizations for renal diseases.8, 9, 10 Current studies were mainly conducted in developed countries, with few reports available from developing countries.11 Moreover, existing studies were relatively small, preventing them from evaluating whether the association varies by sex, age, region, and diseases type. Thus, the health impact of ambient temperature on renal diseases in developing countries has not been fully characterized.

In this study, using national hospitalization dataset from 2000 to 2015 in Brazil, we aim to estimate the association between temperature and hospitalizations for renal diseases, to characterize the time course of the association, and to explore whether the association is consistent in different age groups, gender, regions, and subtypes of renal disease. Besides, we also quantified the hospitalization burden of renal diseases attributable to the increase of temperature.

Methods

Data collection

Daily hospital admission data between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2015 were collected from the Brazilian Unified Health System (BUHS), which has been described in detail in our previous studies.12, 13, 14 The Brazilian Health System has a hybrid structure for health management, based on the simultaneous operation of a public and free service to citizens and a private one, which works in a complementary manner.15 Hospitalization data provided by BUHS covered hospitalizations in both public and privately contracted hospitals, which account for around 80% of total hospitalizations in Brazil.13 A total of 1816 cities with complete hospitalization records for the entire 16 years duration were included in this analysis, which comprised 79·0% of the national population and were located in five regions: North, Northeast, Central West, Southeast, and South (Figure 1). The primary diagnosis was coded according to the International Classification of Diseases–10th revision (ICD-10). We only included hospitalizations with a principal discharge diagnosis of renal diseases (N00-N19) in this study. Cases were classified into 3 main categories: glomerular diseases (N00-N08), renal tubulo-interstitial diseases (N10-N16), and kidney failure (N17-N19). Information on date of admission, sex, and age were also included in the data. Hospitalizations were further classified into three precise diagnoses, including acute renal failure (N17), chronic kidney disease (N18), and pyelonephritis (N10–N12).8,16 Our study has been approved by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee. The Brazilian Ministry of Health did not require ethical approval or informed consent for secondary analysis of aggregated anonymized data from the BUHS.

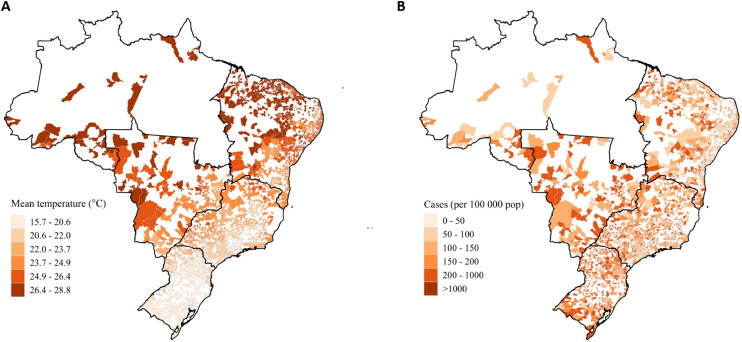

Figure 1.

City-specific daily mean temperature (A) and crude hospitalization rate (per 100 000 residents, B) in Brazil during 2000−2015. City-specific population size were collected from the Brazilian Census 2000 and 2010.

Daily minimum and maximum temperatures, and daily mean relative humidity during the study period were obtained from a national meteorological dataset (0·25° × 0·25° resolution), which was interpolated based on 735 nationwide weather stations in Brazil, using the inverse distance weighting approach.17 City-specific data were collected from the grid overlaying the centroid of each city.14 Data of city-specific population size were collected from the Brazilian Census in 2000 and 2010.18 The daily mean temperature is calculated as the average of the daily minimum and maximum temperature.

Statistical analyses

Temperature-hospitalization association

A time-stratified case-crossover design with conditional logistic regression models was applied to evaluate the association between temperature and hospitalization for renal diseases.19, 20, 49 Case period was defined as the day when the health event (hospitalization) occurs. For each case, the same days of the week in the same calendar month, the same year, and the same city were selected as control periods and thus each case period has 3 or 4 control periods, which could control for seasonality and long-term trend.21 Daily mean temperature for the case period and control periods was compared. Confounders like age, sex, income, and lifestyle, which unlikely change in such a short period, can be effectively controlled by this method with the self-matched design.22, 23, 24

Conditional logistic regression was applied to fit the relationship between temperature and risk of hospitalization for renal diseases:

| (1) |

where stratum i, j is the fixed time strata i in city j (the same calendar month for case day and control days in the same city), is the intercept of stratum i in city j, Holiday is a binary variable indicating whether the date was a public holiday, and are the cross-basis function to fit both the exposure-response relationship and the lag-response relationship of temperature and relative humidity.

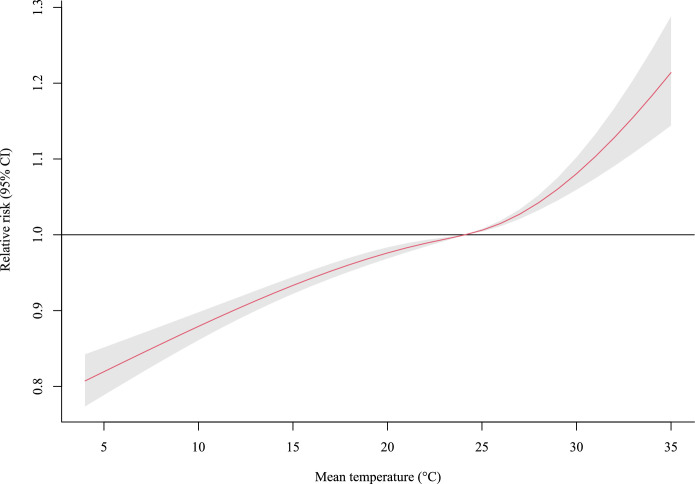

Bayesian information criterion (BIC) was used to evaluate the performance of the nonlinear model (natural cubic spline with 3 degrees of freedom, df = 3) and linear model in the exposure-response dimension of temperature as in the previous study.25 The result and the exposure-response curve (Figure 2) showed that the BIC value of the linear model (2,709,075) is relatively lower than that of the non-linear model (2,709,124). Therefore, a linear function was used for the temperature-response dimension with a natural cubic spline function for the lag-response dimension (df = 3, lag 0–7 days) in the cross-basis function of temperature. Nonlinear models were used in humidity-response dimension (df = 3) and lag-response dimension (df = 3, lag 0–7 days) in the cross-basis function of average relative humidity.

Figure 2.

The association between ambient temperature (every 1˚C increase in daily mean temperature) and hospitalization for renal diseases across 0–7 lag days. The shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval of the relative risk.

Relative risks (RRs) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated to estimate the association of every 1°C increase in ambient temperature with the hospitalization for renal diseases. Stratified analyses were performed to detect the associations in subgroups including sex, region, age group (0–4, 5–19, 20–39, 40–59, 60–79, and ≥80 years), and subtype of renal diseases. Random effect meta-regression with maximum likelihood method was fitted to detect the differences of the associations between subgroups. We also repeated the analyses in the hot season (defined as city-specific 4 adjacent hottest months), cold season (defined as city-specific 4 adjacent coldest months), and moderate season (city-specific months other than cold seasons and hot seasons). Associations between ambient temperature and specific renal disease (acute renal failure, chronic kidney disease, pyelonephritis) were investigated.

Attributable hospitalizations

City-specific daily number of hospitalizations for renal diseases attributable to the increase of temperature was estimated by equation:

| (2) |

where i is the specific day during the study period, is the city-specific 8-day average (day i to day i +7) number of hospitalizations for renal diseases, RRi is the city-specific cumulative relative risk for hospitalizations associated with the increase of mean temperature for day i. RRi can be calculated by the equation:

| (3) |

where Ti is the city-specific mean temperature for day i, Tref is the city-specific reference temperature which is defined as the minimum daily mean temperature for the city during the study period, RRregion is the region-specific association estimated from case-crossover analyses in the region where the city is located. The total attributable cases (AC) and 95% CI were generated by summing the ACi values (95% CIs) of all cities during the study period. The attributable fractions (AFs) and 95% CIs were then calculated by dividing the total AC values (95% CI) by total hospitalization cases for renal diseases.

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses were performed to test the robustness of this study. First, the maximum number of lag days (4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 days) and the df of lag days (3 or 4) were changed in the cross-basis function of temperature (Table S1). Second, the df of exposure-response dimension (3 or 4) and the df of lag days (3 or 4) were changed in the cross-basis function of humidity (Table S2).

R software (version 4.0.1) was used to perform the data analyses, with “dlnm”, “survival”, and “mvmeta” package used for the construction of cross-basis function, conditional logistic regression, and meta-regression, respectively.

Role of the funding source: The funding bodies did not play any role in the study design, data collection, data analyses, results interpretation, writing of this manuscript or decision to publish.

Results

Table 1 summarizes the basic characteristics of the included hospitalizations. Overall, there were a total of 2,726,886 hospitalizations (female: 58·5%) due to renal diseases during 2000–2015, including 313,616 (11·5%) cases with glomerular diseases, 1,431,586 (52·5%) cases with renal tubulo-interstitial diseases, and 981,684 (36·0%) cases with kidney failure. The median age of all cases was 40·8 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 21·4 – 61·7 years), while the median age of cases with glomerular diseases (12·1, IQR: 6·3 – 35·0 years) was much lower than that of cases with renal tubulo-interstitial diseases (32·0, IQR: 19·6 – 53·8 years) and cases with kidney failure (56·7, IQR: 42·1 – 69·1 years). The highest number of hospitalizations for the total renal diseases was observed in the 20–39 age group. The geographical variations in the daily mean temperature and crude hospitalization rate were shown in Figure 1. Cities with the highest daily mean temperature and crude hospitalization rate were generally located in the Central West region and Northeast region.

Table 1.

Summary of hospitalizations for renal diseases by region and age group, in 1816 Brazilian cities during 2000-2015.

| Glomerular diseases | Renal tubulo-interstitial diseases | Kidney failure | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 313,616 | 1,431,586 | 981,684 | 2,726,886 |

| Region (%) | ||||

| North | 12,422 (4.0) | 47,916 (3.3) | 24,407 (2.5) | 84,745 (3.1) |

| Northeast | 141,793 (45.2) | 371,788 (26.0) | 204,407 (20.8) | 717,988 (26.3) |

| Central West | 28,683 (9.1) | 167,762 (11.7) | 82,613 (8.4) | 279,058 (10.2) |

| Southeast | 96,634 (30.8) | 516,865 (36.1) | 467,893 (47.7) | 1,081,392 (39.7) |

| South | 34,084 (10.9) | 327,255 (22.9) | 202,364 (20.6) | 563,703 (20.7) |

| Female, No. (%) | 151,256 (48.2) | 1,008,420 (70.4) | 436,702 (44.5) | 1,596,378 (58.5) |

| Age, median (IQR), years | 12.1 (6.3, 35.0) | 32.0 (19.6, 53.8) | 56.7 (42.1, 69.1) | 40.8 (21.4, 61.7) |

| Age group (%), years | ||||

| 0−4 | 38,787 (12.4) | 104,202 (7.3) | 11,323 (1.2) | 154,312 (5.7) |

| 5−19 | 152,683 (48.7) | 232,383 (16.2) | 41,321 (4.2) | 426,387 (15.6) |

| 20−39 | 53,268 (17.0) | 519,236 (36.3) | 155,896 (15.9) | 728,400 (26.7) |

| 40−59 | 39,502 (12.6) | 278,484 (19.5) | 329,257 (33.5) | 647,243 (23.7) |

| 60−79 | 23,597 (7.5) | 209,896 (14.7) | 349,087 (35.6) | 582,580 (21.4) |

| ≥80 | 5,778 (1.8) | 87,381 (6.1) | 94,796 (9.7) | 187,955 (6.9) |

Note: There were five missing values in sex and nine missing values in age.

Lag association between ambient temperature and hospitalizations for renal diseases

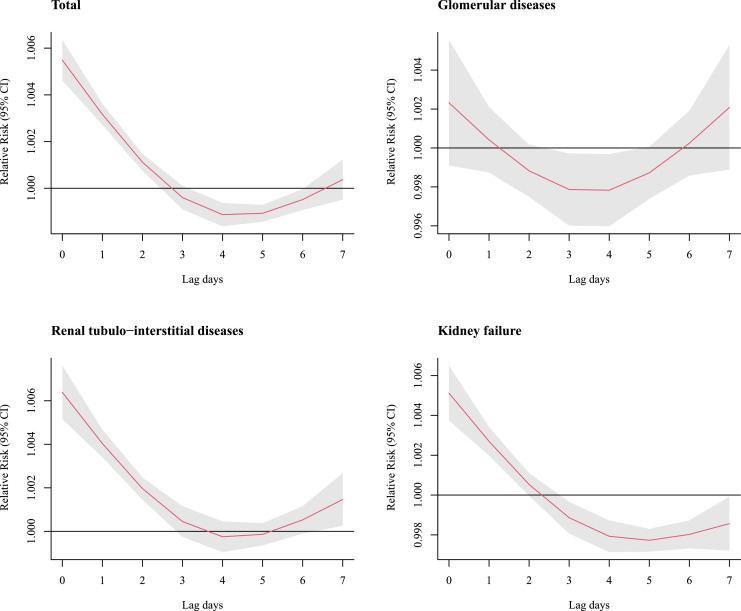

As shown in Figure 3, the associations between temperature and hospitalizations were the highest at lag day 0, decreased gradually to lag day 4, and increased up to lag day 7. A temporal displacement (harvesting effect) can be observed in total, glomerular diseases, and renal diseases at lag day 3 and subsequent 2 days.26

Figure 3.

The association between ambient temperature (every 1˚C increase in daily mean temperature) and hospitalization for renal diseases [Relative risk with 95% confidence intervals (CIs)] across lag 0–7 days by renal diseases subtype. The association for lag 0–7 days was estimated from a time-stratified case-crossover design with conditional logistic regression. A cross-basis function for mean temperature was used in the model with adjustment for daily mean relative humidity and public holidays.

Cumulative association between ambient temperature and hospitalizations for renal diseases

Figure 4 shows estimated RRs for hospitalizations due to renal diseases in relation to a 1°C increase in daily mean temperature from 2000 to 2015. At the national level, the estimated risk of hospitalizations for renal diseases increased by 0·9% (RR = 1·009, 95% CI: 1·008–1·010) per 1°C increase in daily mean temperature over lag 0–7 days. For males, there was a 0·6% increase in renal diseases hospitalizations (RR = 1·006, 95% CI: 1·004–1·008) for each 1°C increase in daily mean temperature, which is lower than that in females (RR = 1·011, 95% CI: 1·009–1·012).

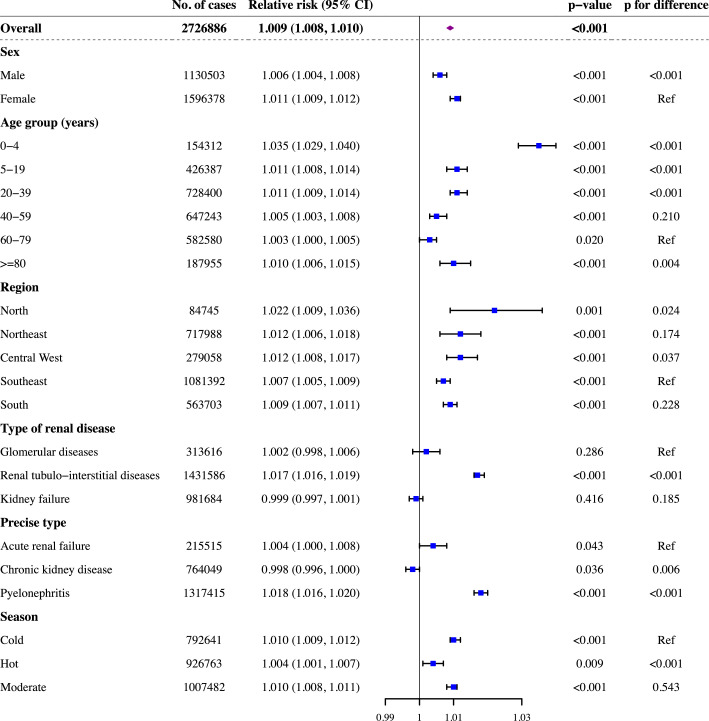

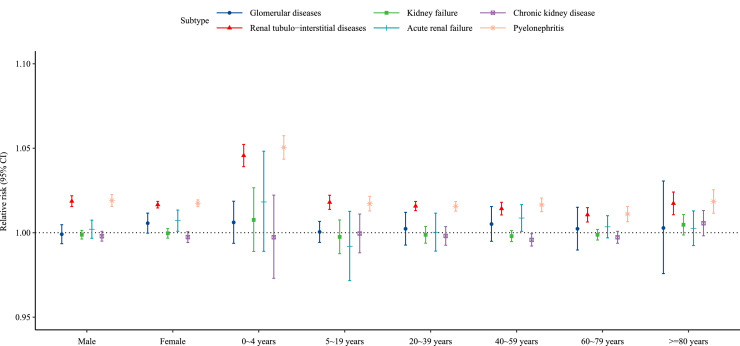

Figure 4.

The association between ambient temperature (every 1˚C increase in daily mean temperature) and hospitalization for renal diseases [Relative risk with 95% confidence intervals (CIs)] over 0–7 lag days. The relative risk represents the cumulative association over lag 0–7 days and came from a time-stratified case-crossover design with conditional logistic regression. A cross-basis function for mean temperature was used in the model with adjustment for daily mean relative humidity and public holidays. P for difference was estimated by meta-regression to test the difference in associations between subgroups.

The associations between renal diseases hospitalizations and daily mean temperature were also examined in different age groups. The highest association was observed in children aged 0–4 years, which shows that a 3·5% increase in renal diseases hospitalizations (RR = 1·035, 95% CI: 1·029–1·040) for each 1°C increase in daily mean temperature. The association was weaker in successive age groups: RR of hospitalizations for renal diseases decreased from 1·035 for those aged 0–4 years to 1·003 (95% CI: 1·000–1·005) for those aged 60–79 years. However, the association for the elderly ≥ 80 years increased to 1·010 (95% CI: 1·006–1·015), which is higher compared with those aged 60–79 years.

Stratified results suggested that risk for hospitalizations is associated with the increase of daily mean temperature in all regions, ranging from an RR of 1·007 (95% CI: 1·005–1·009) in the Southeast region to that of 1·022 (95% CI: 1·009–1·036) in the North region. The estimated risk of hospitalization in the North region and Central West region (RR = 1·012, 95% CI: 1·008–1·017) was higher than that in the Southeast region. We examined the associations between daily mean temperature and hospitalizations for different types of renal diseases (Figure 4). Only the increase of hospitalizations for renal tubulo-interstitial diseases was found to be associated with the increase of temperature (RR = 1·017, 95% CI: 1·016–1·019). When analyses were restricted in cold season, hot season, and moderate season, the associations between the increase of ambient temperature and risk of renal hospitalizations changed slightly and the highest risk was estimated in the cold season. When stratified by precise subtype of renal diseases, the estimated risk of hospitalizations for pyelonephritis increased by 1·8% (RR = 1·018, 95% CI: 1·016–1·020) per 1°C increase in daily mean temperature and for acute renal failure increased by 0·4% (RR = 1·004, 95% CI: 1·000–1·008) per 1°C increase in daily mean temperature, respectively. By contrast, the estimated risk of hospitalizations for chronic kidney disease decreased by 0·2% (RR = 0·998, 95% CI: 0·996–1·000) per 1°C increase in daily mean temperature. Subgroup analyses were further stratified by renal diseases subtype and by sex and age group, showing a similar result (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The association between ambient temperature (every 1˚C increase in daily mean temperature) and hospitalization for renal diseases [Relative risk with 95% confidence intervals (CIs)] over 0–7 lag days, stratified by renal diseases subtype and by sex and age group. The relative risk represents the cumulative association over lag 0–7 days and came from a time-stratified case-crossover design with conditional logistic regression. A cross-basis function for mean temperature was used in the model with adjustment for daily mean relative humidity and public holidays.

Attributable fractions

Table 2 shows the attributable fractions of hospitalizations associated with temperature at the national level and in subgroups. Assuming a causal relationship, a total of 202,093 (95% CI: 141,554–260,594) cases could be attributable to the increase of temperature over lag 0-7 days, which accounted for 7·4% (95% CI: 5·2–9·6%) of the total hospitalizations during the 16 years.

Table 2.

The fraction and number of cases of hospitalization for renal diseases attributable to ambient temperature over lag 0-7 days from 2000 to 2015 in Brazil.

| Subgroup | Attributable Fraction (95% CI), % |

Number of attributable cases (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Overall | 7.4 (5.2, 9.6) | 202,093 (141,554; 260,594) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 7.2 (5.0, 9.3) | 81,438 (56,505; 105,532) |

| Female | 7.6 (5.3, 9.7) | 120,654 (85,049; 155,062) |

| Age group (years) | ||

| 0−4 | 7.1 (4.8, 9.4) | 11,032 (7,454; 14,478) |

| 5−19 | 7.0 (4.7, 9.3) | 30,025 (20,201; 39,500) |

| 20−39 | 7.6 (5.3, 9.9) | 55,683 (38,936; 71,845) |

| 40−59 | 7.4 (5.3, 9.5) | 48,166 (34,079; 61,793) |

| 60−79 | 7.4 (5.3, 9.5) | 43,378 (31,021; 55,344) |

| ≥80 | 7.3 (5.2, 9.4) | 13,809 (9,864; 17,632) |

| Region | ||

| North | 12.3 (5.4, 18.5) | 10,387 (4,608; 15,646) |

| Northeast | 4.5 (2.2, 6.8) | 32,544 (15,836; 48,772) |

| Central West | 10.0 (6.7, 13.2) | 28,013 (18,638; 36,974) |

| Southeast | 6.4 (4.8, 7.9) | 69,125 (51,975; 85,944) |

| South | 11.0 (9.0, 13.0) | 62,024 (50,498; 73,258) |

| Type of renal diseases | ||

| Glomerular diseases | 6.4 (4.2, 8.6) | 20,157 (13,031; 27,041) |

| Renal tubulo−interstitial diseases | 7.7 (5.4, 9.9) | 110,391 (77,378; 142,246) |

| Kidney failure | 7.3 (5.2, 9.3) | 71,544 (51,145; 91,307) |

| Precise type of renal diseases | ||

| Acute renal failure | 7.4 (5.3, 9.5) | 15,996 (11,424; 20,419) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 7.3 (5.2, 9.3) | 55,394 (39,609; 70,692) |

| Pyelonephritis | 7.7 (5.4, 10.0) | 101,905 (71,301; 131,423) |

| Season | ||

| Cold | 5.1 (3.5, 6.6) | 40,267 (28,026; 52,176) |

| Hot | 4.3 (3.0, 5.7) | 40,260 (27,489; 52,743) |

| Moderate | 5.2 (3.7, 6.8) | 42,906 (30,097; 55,432) |

Note: Attributable burden was calculated as the increase in daily mean temperature compared with the minimum daily mean temperature for the city during the study period.

Although there was no substantial gender or age-related difference, the estimated attributable fraction varied in different regions. Assuming a causal relationship, it was observed that about 12.3% (95% CI: 5.4–18.5%) of the hospitalizations was attributable to the increase of temperature in the North region, which was the highest among the five regions. By contrast, the estimated attributable fraction was lowest in the Northeast region (4·5%, 95% CI: 2·2–6·8%). For different types of renal diseases, the attributable fraction was 7·7% (95% CI: 5·4–9·9%) for renal tubulo-interstitial diseases which was higher than that for kidney failure and glomerular diseases.

Sensitivity analysis

All estimations on the temperature-hospitalization associations remained robust when we changed the maximum number of lag days and the df of lag days in the cross-basis function of temperature (Supplementary table S1). Similarly, results were almost unchanged when changing the df of relative humidity and the df of lag days in the cross-basis function of humidity (Supplementary table S2).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest study evaluating the association between ambient temperature and hospitalizations for renal diseases in the world and the first in Brazil to date, covering 2,726,886 hospitalizations from 1816 cities in 2000–2015. Using a time-stratified case-crossover design, we found that the risk of hospitalizations for renal diseases was positively associated with daily mean temperature, and the association was strongest on the hospitalization day but remained so for 2 subsequent days. Assuming a causal relationship, our study showed that ambient temperature could account for an overall attributable fraction of 7·4% in total hospitalizations in Brazil. Besides, the results also identified that associations were higher in children aged 0–4 years and appeared to be stronger for renal tubule-interstitial diseases.

This study showed increased hospitalizations for total renal diseases, renal tubulo-interstitial diseases, and acute renal failure with the increase of daily mean temperature, which is consistent with previous studies.8,16,27, 28, 29 An increased risk of hospitalizations for pyelonephritis was also found in this study, which is inconsistent with a previous study.8 This inconsistency may be attributed to the large sample size in our work and different disease distribution. We also found that ambient temperature showed an inverse association with the risk of hospitalization for CKD. It was demonstrated that acute renal failure could increase the risk of developing progressive CKD, which implied that increased risk of ambient temperature for AKI may eventually translate into risk for CKD.8,30

The biological mechanisms for the association between temperature and hospitalization for renal diseases are still unclear. Renal diseases can occur as a consequence of dehydration or decreased extracellular fluid (ECF) due to the increase of temperature, which could be related to the effects of vasopressin, the activation of the aldose reductase-fructokinase pathway, and the effects of chronic hyperuricemia.8,31,32 Besides, acute renal failure could happen due to the precipitation of myoglobin in the kidney tubules when people are exposed to high temperatures and had a condition of exertional rhabdomyolysis with a pre-existing viral or bacterial infection or the use of analgesics and NSAIDs.33 In addition, fluid loss in the warmer days reduces urinary flow, which may weaken the diluting effect on contaminating bacteria and virulence factors, and predispose to urinary infections.8,34 The findings in this study suggest that this association could manifest and become more profound in cold season. Thus further studies are warranted to explore the association, especially in moderate and cold seasons.

In line with previous studies, we found that children, young adults, and the elderly ≥ 80 years were more susceptible to the influence of increased temperature, which can be attributed to immature physiological systems or lowered thermotolerance and impaired thirst sensation.18,35 Another finding in this study was the higher risk of hospitalization for females compared with males. Our finding was similar to those from Korea showing that females may be more vulnerable to high temperatures than males.16 Another study, however, suggested that men, especially those with hypertension, tended to be more vulnerable to AKI in response to high temperature.28 We also oberserved that the association varied in different regions, which may be related to the social economic status of different regions.13,36,37

Global warming is affecting human health in profound ways and it was estimated that 125 million additional vulnerable people were endangered with heat exposure between 2000 and 2016.38 Assuming a causal relationship, we estimated that over 7% of hospitalizations for renal diseases in Brazil could be attributed to the increase of temperature during 2000–2015. Compared with our previous study, the attributable fraction of hospitalizations for renal diseases was slightly higher than that of all causes, suggesting that the heat-related burden for renal diseases should not be overlooked.18 Consistent with previous studies, findings on the lag patterns showed that the association between temperature and renal diseases appeared immediately and was the largest on the present day.25,29 As a result, heat warning systems and prompt preventive measures should be implemented to reduce preventable mortality and morbidity.39, 40, 41

This study has several strengths. First, this is the first study to assess the association between ambient temperature and hospitalizations for renal diseases in Brazil. By considering different subtypes of renal diseases and age groups, our study provides insights into varying susceptibility for children, adults, and the elderly. Second, this study covered nearly 80% of the Brazilian population and the findings could be representative of the general population. As Brazil is the world's fifth-most populous nation and is undergoing rapid economic development, the results may also have implications for other low- and middle-income countries.42,43

Some limitations must be acknowledged. First, gridded temperature data rather than individual-level data were used in our analysis, which may lead to some inevitable measurement error and underestimate the temperature-hospitalization association. Second, air pollution was not adjusted in this study due to the lack of data for most Brazilian cities. However, previous studies showed that the confounding by air pollution is minimal and may be more evident for respiratory disease.44,45 Moreover, increasing ozone levels due to the extreme temperature and sunlight indicates that air pollutants may act as a mediator between temperature and health indicators.46,47 Third, the diagnoses of renal diseases in this study were entirely dependent on the ICD-10 codes, which may lead to outcome misclassification. The diagnoses could not be reviewed and verified according to medical records personally. However, this bias is more likely to be random and tends to attenuate the association.29,48 Finally, only 80% of the Brazilian population were covered in this study, which may bring a potential selection bias. However, this is the largest national study on this topic in the world and our results could provide the most precise estimation compared other studies in this area.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that there is an association between ambient temperature and hospitalization for renal diseases. The results showed that females, children, adolescents, and the elderly are more vulnerable to high temperature with regard to total renal diseases, which implicated that interventions should be promoted by targeting individuals at greater risks. In the context of global warming, more strategies and policies should be developed to prevent heat-related hospitalizations and address climate change as soon as possible.

Contributors

BW performed the main analysis and wrote the original draft. RX, MSZSC and PHNS prepared the data and made substantial contributions to the design of the study. YW assisted the analysis and interpretation of data. SL and YG conceived the study, developed the methodology, revised the manuscript and was responsible for funding of the study.

Data sharing statement

Researchers who are interested in using the data should contact Prof Yuming Guo (yuming.guo@monash.edu) with their study protocol and statistical analysis plan. There will be an assessment for the data request by a committee including stakeholders from the Brazilian Ministry of Health. If approved by the committee, the researcher can gain access to the data, and an agreement on the use of the data may also be needed.

Ethics committee approval

This study was approved by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee, and individual consent was exempted because we used anonymized data.

Editorial note: The Lancet Group takes a neutral position with respect to territorial claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Declaration of Competing Interest

We declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

BW, RX, YW were supported by China Scholarship Council [grant number 202006010043, 201806010405, 202006010044] (https://www.csc.edu.cn/chuguo/s/1844, https://www.csc.edu.cn/chuguo/s/1267) SL was supported by the Early Career Fellowship of the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council [grant number APP1109193] (https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/). YG was supported by the Career Development Fellowship of the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council [grant number APP1163693] (https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/). The funding bodies did not play any role in the study design, data collection, data analyses, results interpretation, writing, and submission of this manuscript. We thank the Brazilian Ministry of Health for providing the hospitalization data, and also many thanks to the Brazilian National Institute of Meteorology for providing the meteorological data.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.lana.2021.100101.

Contributor Information

Yuming Guo, Email: yuming.guo@monash.edu.

Shanshan Li, Email: shanshan.li@monash.edu.

Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Luyckx VA, Tonelli M, Stanifer JW. The global burden of kidney disease and the sustainable development goals. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2018;96(6) doi: 10.2471/BLT.17.206441. 414-22D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levin A, Tonelli M, Bonventre J, et al. Global kidney health 2017 and beyond: a roadmap for closing gaps in care, research, and policy. The Lancet. 2017;390(10105):1888–1917. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30788-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stanaway JD, Afshin A, Gakidou E, et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1923–1994. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32225-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silva PAB, Silva LB, Santos JFG, Soares SM. Brazilian public policy for chronic kidney disease prevention: challenges and perspectives. Revista de saude publica. 2020;54:86. doi: 10.11606/s1518-8787.2020054001708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidt MI, Duncan BB, e Silva GA, et al. Chronic non-communicable diseases in Brazil: burden and current challenges. The Lancet. 2011;377(9781):1949–1961. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hales S, Kovats S, Lloyd S, Campbell-Lendrum D. World Health Organization; Switzerland: 2014. Quantitative risk assessment of the effects of climate change on selected causes of death, 2030s and 2050s. [Google Scholar]

- 7.ÓF T, Flynn A, Mulkerrin EC. Heat-related chronic kidney disease mortality in the young and old: differing mechanisms, potentially similar solutions? BMJ evidence-based medicine. 2019;24(2):45–47. doi: 10.1136/bmjebm-2018-110971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borg M, Bi P, Nitschke M, Williams S, McDonald S. The impact of daily temperature on renal disease incidence: an ecological study. Environmental health: a global access science source. 2017;16(1):114. doi: 10.1186/s12940-017-0331-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen T, Sarnat SE, Grundstein AJ, Winquist A, Chang HH. Time-series Analysis of Heat Waves and Emergency Department Visits in Atlanta, 1993 to 2012. Environmental health perspectives. 2017;125(5) doi: 10.1289/EHP44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bobb JF, Obermeyer Z, Wang Y, Dominici F. Cause-Specific Risk of Hospital Admission Related to Extreme Heat in Older Adults. JAMA. 2014;312(24):2659. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.15715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee WS, Kim WS, Lim YH, Hong YC. High Temperatures and Kidney Disease Morbidity: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Journal of preventive medicine and public health = Yebang Uihakhoe chi. 2019;52(1):1–13. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.18.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao Q, Coelho MSZS, Li S, et al. Trends in Hospital Admission Rates and Associated Direct Healthcare Costs in Brazil: A Nationwide Retrospective Study between 2000 and 2015. The Innovation. 2020;1(1) doi: 10.1016/j.xinn.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu R, Zhao Q, Coelho MSZS, et al. Socioeconomic inequality in vulnerability to all-cause and cause-specific hospitalisation associated with temperature variability: a time-series study in 1814 Brazilian cities. The Lancet Planetary Health. 2020;4(12):e566–ee76. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30251-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao Q, Coelho MSZS, Li S, et al. Spatiotemporal and demographic variation in the association between temperature variability and hospitalizations in Brazil during 2000-2015: A nationwide time-series study. Environment international. 2018;120:345–353. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paim J, Travassos C, Almeida C, Bahia L, Macinko J. The Brazilian health system: history, advances, and challenges. The Lancet. 2011;377(9779):1778–1797. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim E, Kim H, Kim YC, Lee JP. Association between extreme temperature and kidney disease in South Korea, 2003-2013: Stratified by sex and age groups. The Science of the total environment. 2018;642:800–808. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xavier AC, King CW, Scanlon BR. Daily gridded meteorological variables in Brazil (1980-2013) International Journal of Climatology. 2016;36(6):2644–2659. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao Q, Li S, Coelho MSZS, et al. Geographic, Demographic, and Temporal Variations in the Association between Heat Exposure and Hospitalization in Brazil: A Nationwide Study between 2000 and 2015. Environmental health perspectives. 2019;127(1) doi: 10.1289/EHP3889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levy D, Sheppard L, Checkoway H, et al. A case-crossover analysis of particulate matter air pollution and out-of-hospital primary cardiac arrest. Epidemiology. 2001;12(2):193–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li S, Guo Y, Williams G. Acute Impact of Hourly Ambient Air Pollution on Preterm Birth. Environmental health perspectives. 2016;124(10):1623–1629. doi: 10.1289/EHP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu R, Xiong X, Abramson MJ, Li S, Guo Y. Ambient temperature and intentional homicide: A multi-city case-crossover study in the US. Environ Int. 2020;143 doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janes H, Sheppard L, Lumley T. Case-crossover analyses of air pollution exposure data: referent selection strategies and their implications for bias. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass) 2005;16(6):717–726. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000181315.18836.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang X, Wang S, Kindzierski W. Eliminating systematic bias from case-crossover designs. Stat Methods Med Res. 2019;28(10-11):3100–3111. doi: 10.1177/0962280218797145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barnett AG, Dobson AJ. Springer; 2010. Analysing seasonal health data. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu R, Zhao Q, Coelho M, et al. The association between heat exposure and hospitalization for undernutrition in Brazil during 2000-2015: A nationwide case-crossover study. Plos Med. 2019;16(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu R, Zhao Q, Coelho M, et al. Association between Heat Exposure and Hospitalization for Diabetes in Brazil during 2000-2015: A Nationwide Case-Crossover Study. Environmental health perspectives. 2019;127(11) doi: 10.1289/EHP5688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim SE, Lee H, Kim J, et al. Temperature as a risk factor of emergency department visits for acute kidney injury: a case-crossover study in Seoul, South Korea. Environmental Health. 2019;18(1) doi: 10.1186/s12940-019-0491-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lim Y-H, So R, Lee C, et al. Ambient temperature and hospital admissions for acute kidney injury: A time-series analysis. Science of The Total Environment. 2018;616-617:1134–1138. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.10.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fletcher BA, Lin S, Fitzgerald EF, Hwang SA. Association of Summer Temperatures With Hospital Admissions for Renal Diseases in New York State: A Case-Crossover Study. American journal of epidemiology. 2012;175(9):907–916. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lo LJ, Go AS, Chertow GM, et al. Dialysis-requiring acute renal failure increases the risk of progressive chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2009;76(8):893–899. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fakheri RJ, Goldfarb DS. Ambient temperature as a contributor to kidney stone formation: implications of global warming. Kidney International. 2011;79(11):1178–1185. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roncal-Jimenez C, Lanaspa MA, Jensen T, Sanchez-Lozada LG, Johnson RJ. Mechanisms by Which Dehydration May Lead to Chronic Kidney Disease. Annals of nutrition & metabolism. 2015;66(Suppl 3):10–13. doi: 10.1159/000381239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clarkson PM. Exertional Rhabdomyolysis and Acute Renal Failure in Marathon Runners. Sports Medicine. 2007;37(4):361–363. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200737040-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simmering JE, Polgreen LA, Cavanaugh JE, Erickson BA, Suneja M, Polgreen PM. Warmer Weather and the Risk of Urinary Tract Infections in Women. J Urol. 2021;205(2):500–506. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000001383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hansen AL, Bi P, Ryan P, Nitschke M, Pisaniello D, Tucker G. The effect of heat waves on hospital admissions for renal disease in a temperate city of Australia. International journal of epidemiology. 2008;37(6):1359–1365. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu Y, Xu R, Wen B, et al. Temperature variability and asthma hospitalisation in Brazil, 2000–2015: a nationwide case-crossover study. Thorax. 2021 doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-216549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu R, Zhao Q, Coelho M, et al. Socioeconomic level and associations between heat exposure and all-cause and cause-specific hospitalization in 1,814 Brazilian cities: A nationwide case-crossover study. Plos Med. 2020;17(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sorensen C, Garcia-Trabanino R. A New Era of Climate Medicine — Addressing Heat-Triggered Renal Disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019;381(8):693–696. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1907859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sera F, Armstrong B, Tobias A, et al. How urban characteristics affect vulnerability to heat and cold: a multi-country analysis. International journal of epidemiology. 2019;48(4):1101–1112. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyz008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Armstrong B, Sera F, Vicedo-Cabrera AM, et al. The Role of Humidity in Associations of High Temperature with Mortality: A Multicountry, Multicity Study. Environmental health perspectives. 2019;127(9):97007. doi: 10.1289/EHP5430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen R, Yin P, Wang L, et al. Association between ambient temperature and mortality risk and burden: time series study in 272 main Chinese cities. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2018 doi: 10.1136/bmj.k4306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lima-Costa MF, de Andrade FB, de Souza PRB, Jr., et al. The Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Aging (ELSI-Brazil): Objectives and Design. American journal of epidemiology. 2018;187(7):1345–1353. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwx387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zou Z, Cini K, Dong B, et al. Time Trends in Cardiovascular Disease Mortality Across the BRICS: An Age-Period-Cohort Analysis of Key Nations With Emerging Economies Using the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Circulation. 2020;141(10):790–799. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.042864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Green RS, Basu R, Malig B, Broadwin R, Kim JJ, Ostro B. The effect of temperature on hospital admissions in nine California counties. Int J Public Health. 2010;55(2):113–121. doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-0076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Basu R, Pearson D, Malig B, Broadwin R, Green R. The effect of high ambient temperature on emergency room visits. Epidemiology. 2012;23(6):813–820. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31826b7f97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buckley JP, Samet JM, Richardson DB. Commentary: Does air pollution confound studies of temperature? Epidemiology. 2014;25(2):242–245. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Williams S, Nitschke M, Sullivan T, et al. Heat and health in Adelaide, South Australia: assessment of heat thresholds and temperature relationships. The Science of the total environment. 2012;414:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu MC, Jan MS, Chiou JY, Wang YH, Wei JC. Constipation might be associated with risk of allergic rhinitis: A nationwide population-based cohort study. PloS one. 2020;15(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu Y, Li S, Guo Y. Space-Time-Stratified Case-Crossover Design in Environmental Epidemiology Study. Health Data Science. 2021;2021 doi: 10.34133/2021/9870798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.