Abstract

Background

Many states in the United States (US) have introduced barriers to impede voting among individuals from socio-economically disadvantaged groups. This may reduce representation thereby decreasing access to lifesaving goods, such as health insurance.

Methods

We used cross-sectional data from 242,727 adults in the 50 states and District of Columbia participating in the US 2017 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). To quantify access to voting, the Cost of Voting Index (COVI), a global measure of barriers to voting within a state during a US election was used. Multilevel modeling was used to determine whether barriers to voting were associated with health insurance status after adjusting for individual- and state-level covariates. Analyses were stratified by racial/ethnic identity, household income, and age group.

Findings

A one standard deviation (SD) increase in COVI score was associated with an overall increased odds of being uninsured (OR=1.25; 95% CI=1.22, 1.28). This association was also present for Non-Hispanic Black (OR=1.18; 95% CI=1.13,1.22), Hispanic (1.18; 95% CI=1.15,1.21), and Asian (OR=1.45;95%CI=1.27,1.66), and other Non-Hispanic (OR=1.12, 95% CI=1.06, 1.18) US adults, but not for White Non-Hispanic and Native US adults. Likewise, a one SD increase in COVI among adults from low-income households was associated with an increased odds of being uninsured (OR=1.32; 95% CI=1.26,1.38) but there was no association among individuals with incomes greater than $75,000. This association was similar for younger US adults (OR=1.22; 95%CI=1.20,1.24) but not among those aged 45 to 64.

Interpretation

Groups commonly targeted by voting restriction laws—those with low incomes, who are racial minorities, and who are young—are also less likely to be insured in states with more voting restrictions. However, those who are wealthier, white or older are no more likely to be uninsured irrespective of the level of voting restrictions.

Funding

Pabayo is a Tier II Canada Research Chair.

1. Introduction

Roughly 253 laws that restrict voting rights were introduced in the United States as of July 2021, up from 35 in 2020 [1]. Laws erecting barriers to voting disproportionately impact individuals from low-income households, racial minority groups, and younger US residents [1,2]. Barriers to voting take many forms, including laws allowing certain types of IDs to be used in polling stations that make it easier for targeted groups to vote (e.g., gun permits) while restricting others (e.g., those with student ID cards) [3]. Such laws are often enacted in the name of preventing voter fraud, but have clear underlying political motives.

These types of laws often result in reduced voting and weakened political power of minority groups[4], specifically Black and Latinx populations. For example, many states with high proportions of non-Hispanic Black Americans who support Medicaid expansion tend to be represented by elected officials who oppose Medicaid expansion [5]. Representatives to federal and state governments are elected from "single-member, winner-take-all" districts within a two-party system that often encourages non-voting among the working class [6]. Therefore, laws that place barriers to voting among sub-groups in the population can have disproportionate effects on the policy landscape [2,7].

Research has shown that voter identification laws have been associated with reductions in minority turnout [7]. Laws that restrict voting are usually enacted at the state-level, where legislators also have the power to limit access to Medicaid and private insurance policies offered under the Affordable Care Act. By reducing the representation of voters who use such services, fewer officials are elected to advocate for such services [8].

These differences in voting can therefore produce run-on health effects by increasing access to life-saving goods, such as health insurance [8,9]. In 2019, 10.3%, or 33.2 million Americans, lacked health insurance coverage [10]. Among US adults aged 18-64, 14.7% were uninsured [10]. The vast majority of uninsured people in the US are from low-income households and ethnic or racial minority groups [11], [12], [13]. Americans who are from lower income or racial and ethnic minority backgrounds are less likely to be insured compared with those with higher income or who are white [14,15]. Finally, younger adults are at greater risk for being uninsured since Medicare provides coverage to the vast majority of older adults in the US; with fewer than 1% of those 65 years and older are uninsured [16].

The Ecosocial Theory of Disease Transmission conceptualizes health inequities in relation to power, social hierarchy, life course, historical generation, biology, and ecosystems [17]. In the US, laws, known as "Jim Crow" laws, incorporated voting restrictions such as voter suppression, which were similar to apartheid laws enacted in 20th century South Africa [17,18].

Laws that make it difficult for racialized minorities, in particular non-Hispanic Black Americans, to vote are examples of structural racism, which has been defined as the "totality of ways in which societies foster racial discrimination through mutually reinforcing systems of housing, education, employment, earnings, benefits, credit, media, health care, and criminal justice."12 For example, a 2013 U.S. Supreme Court decision, Shelby v. Holder [19], overturned parts of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that had prohibited racial discrimination in elections in the US [20,21]. It explicitly outlaws deliberate attempts to disenfranchise minority groups via voting restrictions, such as literacy tests. Originally, the act also contained a special core provision known as the Section 5 preclearance requirement, which prohibits certain jurisdictions from implementing any change affecting voting without receiving preapproval from the US attorney general or the US District Court for D.C. to ensure that the change does not discriminate against protected minorities [21]. However, in 2013, this preclearance clause was ruled unconstitutional in the Shelby decision on the grounds that it was outdated and infringed on the equal sovereignty of the states [19].

Since this ruling, states and localities have closed polling stations, early voting has been curtailed, voter rolls have been purged, and there has been an imposition of strict voter ID laws [22,23]. As a result, it has become disproportionately difficult to vote in certain areas within states, such as predominantly non-Hispanic Black counties [23].

However, these laws extend beyond structural racism, and spill over to social class. Overall, these laws have made it difficult for not only for racial minorities to vote, but also younger, low socioeconomic status (SES) groups as well. The purpose of this study is to examine the associations between state-level access to voting and the odds of being uninsured in the US. Furthermore, we test whether associations were heterogeneous across sociodemographic groups, such as race, household income, and age groups.

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

PubMed, PsychInfo, and ScienceDirect were searched using the following key terms: Barriers to Voting/Rights, Voting Restrictions/Laws, Structural Racism, Health/Healthcare Insurance, Medicaid, and Affordable Care Act. Studies, as well as reports and data from Federal and State health agencies, and commentaries published after January 1, 2000 were included if they explored the relationship between voting restrictions or barriers and with health insurance or healthcare insurance within the United States. Most studies identified a relationship between voter turnout or voting participation and health care insurance or Medicaid. To our knowledge, we did not identify any empirical evidence examining the relationship between state-laws restricting voting rights and access to health insurance.

Added value to this study

To our knowledge, this is the first study identifying the association between barriers to voting and the odds for not having health insurance. Findings indicate greater barriers to voting is associated with a greater odds for being uninsured among adults who are Non-Hispanic Black, Asian, young, and from low household income backgrounds.

Implications of all the available evidence

Since most US states have enacted 153 new laws that are barriers to voting in 2021 (so far), these findings highlight the potential risk for widening social and health inequities. Members of disenfranchised groups across race, socio-economic status, and age may disproportionately be affected by the inability to participate in their right to vote.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

2. Methods

We analyzed the 2017 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), a random-digit dialed telephone survey conducted annually by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [24]. For telephone landlines, the BFRSS utilizes a disproportionate stratified sample design [25]. For cellular telephone sampling, commercially available sampling frames were utilized [25]. The median combined response rate for both landlines and cellphones was 45.9%, with a range of 30.6-64.1% across the states [26]. Design weights were developed to take into account the design of the BRFSS survey and characteristics of the population [25]. Data weighting helps make sample data more representative of the population from which the data were collected [25]. The BRFSS collects health risk data from all 50 states and the District of Columbia. The target population includes non-institutionalized individuals aged 18 years and older with access to a landline or cellular telephone. For this investigation, we analyzed data among adults aged 18 to 64 years. Older adults were excluded due to nearly universal health insurance coverage in this population offered by Medicare.

2.1. Measures

Area-level covariates. The primary exposure of interest is access to voting as measured using the Cost of Voting Index (COVI). The COVI is a global measure of barriers or restrictions on voting rights [27] for both state and federal elections, however federal voting restrictions are much less frequent that state-level restrictions. A principal components analysis on 33 different state election laws from 1996 to 2016 was conducted. The barriers included in the COVI are: 1) the number of days prior to an election that registrations must occur; 2) whether felons are allowed to register; 3) whether participation in a state training course is required; 4) whether pre-registration is allowed; 5) whether early voting is allowed; 6) whether time off from work is mandated for voting; 7) whether the state or locality has reduced the number of polling stations in some areas but not others; 8) whether a photo ID is required; and 9) the number of hours the polls are open [27]. The higher the score, the more difficult it is to vote [27]. The construct validity of the COVI scale has been tested, and aggregate voter turnout is lower in states with higher index values [27].

The state's political ideology was measured using the Cook Partisan Voting Index (CPVI), which is a measurement of how strongly a US state leans toward the Democratic party or Republican party. It is based on how that state voted in the presidential elections of 2012 and 2016 [28]. Scores ranged from -43 to +25; the higher the score, the more the state leaned Republican. Scores were standardized using the Z-transformation.

Other state-level covariates include the median income, proportion of the state in poverty, proportion of the state population that is Non-Hispanic Black, and the population size. None of the state-level factors were strongly correlated (Pearson correlation coefficients ranged from -0.59 to 0.38). In order to facilitate interpretation, we used the Z-transformation on these continuous variables to standardize these variables into z-scores.

Individual-level covariates. Individual-level covariates that could confound the relationship between voting barriers or restrictions on the right to vote and health insurance include gender, age, total household income (less than $10,000, $10,000 to $15,000, $15,001 to $20,000, $20,001 to $25,000, $25,001 to $35,000, $35,001 to $50,000, $50,001 to $75,000, and greater than $75,000), race/ethnicity (White non-Hispanic, Black non-Hispanic, Asian non-Hispanic, American Indian/Alaskan Native non-Hispanic, Hispanic, and other race non-Hispanic), education (less than high school, high school, some college, and college graduate), and marital status (coupled or single).

2.2. Outcome measures

To assess health care coverage, respondents were asked "Do you have any kind of health care coverage, including health insurance, prepaid plans such as HMOs, government plans such as Medicare or Indian Health Service?" Response options included 1) Yes; 2) No; 7) Don't know/Not sure; 9) Refused. Those who responded "no" were categorized as having no access to health care. Those who did not know, were not sure, refused, or who had a missing response were excluded.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

Since respondents were nested within 50 states and the District of Columbia, multilevel logistic regression modeling was used to investigate the potential relationship between COVI and the odds of having no health insurance. A sequence of models was conducted. We first estimated a state-level intercept-only model and the 95% plausible value range [29], which is similar to the ICC. This value represents the degree of variability of having no health care insurance between US states for each outcome. For example, the range presents the minimum and maximum values in proportions of respondents not ensured within the US states. Second, we measured the unadjusted association between the COVI index and the odds of not being insured. Third, we added state-level demographic characteristics into the models. Fourth, we stratified the analyses across racial/ethnic, household income, and age groups to determine whether associations were heterogeneous across sociodemographic groups. With respect to interaction terms, we observed statistically significant interactions between income x COVI, age x COVI, and non-Hispanic Black x COVI. The 2017 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System sampling weights were used, and analyses were conducted with Stata v. 14.0.

Since barriers to voting or restrictions on the right to vote within a state may be a marker of political ideology, we first determined the correlation between COVI and CPVI. The Pearson correlation coefficient was 0.22. Because the association is weak, we conducted sensitivity analyses in which CPVI was included and excluded from the final model specification.

2.4. Role of the funding source

The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

3. Results

The 2017 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System included 287,816 respondents aged 18 to 64 years from 50 states and the District of Columbia. All respondents with missing data on health insurance or the socio-demographic covariates of interest were excluded, yielding a case-complete dataset of n=242,727 participants (84.3%). Those excluded were more likely to be female, single, non-white, and have less than a high school education, and less likely to have a household income greater than 75,000 dollars.

The characteristics of the respondents with complete data can be found in Table 1. Among the BRFSS respondents, 50.5% were men. A majority of the participants were White non-Hispanic (60.9%) and were coupled (57.1%). Approximately 36.8% had a household income of over $75,000, and 61.0% had at least some college education.

Table 1.

Characteristics of US adults participating in the 2017 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) (n=242,727) and US states (50 states and the District of Columbia)

| Unweighted n | Weighted % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Level Characteristics | |||

| Sex | |||

| Male | 114,031 | 50.5 | |

| Female | 128,696 | 49.5 | |

| Age, years | |||

| 18-24 | 18,493 | 13.5 | |

| 25-34 | 30,243 | 22.5 | |

| 35-44 | 45,292 | 21.5 | |

| 45-54 | 58,196 | 21.2 | |

| 55-64 | 80,503 | 21.2 | |

| Racial Background | |||

| White Non-Hispanic | 178,984 | 60.9 | |

| Black Non-Hispanics | 21,334 | 12.3 | |

| Hispanic | 22,986 | 17.7 | |

| Asian Non-Hispanic | 6,322 | 5.8 | |

| Native Non-Hispanic | 5,386 | 1.0 | |

| Other Non-Hispanic | 7,715 | 2.1 | |

| Household Income | |||

| Less than 10,000 | 12,788 | 6.0 | |

| 10,000 to 15,000 | 11,014 | 4.7 | |

| 15,000 to 25,000 | 16,090 | 7.3 | |

| 20,000 to 25,000 | 19,223 | 8.7 | |

| 25,000 to 35,000 | 21,880 | 9.6 | |

| 35,000 to 50,000 | 31,051 | 12.5 | |

| 50,000 to 75,000 | 38,747 | 14.6 | |

| Greater than 75,000 | 91,934 | 36.8 | |

| Education | |||

| Less than High School | 15,330 | 12.3 | |

| High School | 61,974 | 26.7 | |

| Some College | 69,193 | 31.8 | |

| College | 96,230 | 29.2 | |

| Marital Status | |||

| Couple | 143,558 | 57.1 | |

| Single | 99,139 | 42.9 | |

| State Level Characteristics (n=51) | Mean (SD) | Median | Range |

| COVI | 0.01 (0.74) | 0.06 | -2.06 to 1.30 |

| CPVI | 2.57(12.3) | 3.0 | -43 to 25 |

| State Median Income, USD | 58,143(9,820) | 56,565 | 41,754-78,9945 |

| Proportion Non-Hispanic Black | 12.1 (11.1) | 8.7 | 0.8-52.2 |

| Proportion Poor | 14.2 (3.1) | 14.5 | 8.2-22 |

| State Population | 6,332,183 (7,235,904) | 4,438,182 | 584,215-39,167,117 |

The characteristics of the 50 states and District of Columbia are also presented in Table 1. The COVI index had a mean of 0.01, a standard deviation (SD) of 0.74, a median of 0.06, and ranged from -2.06 to 1.30. The mean CPVI was 2.6 (SD=12.3), the state mean income was $58,143 (SD=9,820), the proportion non-Hispanic Black was 12.1 (SD=11.1), the proportion poor was 14.2 (SD=3.1), and the mean state population was 6,332,183 (SD=7,235,904).

The intercept-only multi-level model confirmed significant variability in the percentage of the population with health insurance across the US states. For example, the overall predictive probability of having no health insurance among US adults aged 18-64 was 15.3%. The 95% plausible value range values indicated that having no health insurance varied between 11.9% to 19.4% across US states.

Table 2 shows the association between COVI and the odds of being uninsured. One standard deviation increase in COVI was associated with an unadjusted increased odds of being uninsured (odds ratio [OR]=1.03, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.01,1.05, not shown). When state-level characteristics were added to the model, the association became much stronger; one standard deviation increase of COVI in the adjusted model was associated with a 1.25 increased odds of having no health insurance (95% CI=1.22,1.28). When analyses were stratified by race (Table 2), there was no association between COVI and being uninsured for White non-Hispanics and Native non-Hispanics. However, there was a strong association for racial and ethnic minority groups. For Non-Hispanic Blacks (OR=1.18, 95% CI=1.13,1.22), Hispanics (OR=1.18, 95% CI=1.15,1.21), Asians (OR=1.45, 95% CI=1.27,1.66), and members of other racial groups (OR=1.12, 95% CI=1.06, 1.18), a strong association between COVI and being uninsured emerges.

Table 2.

The relationship between Cost of Voting Index and odds for no health insurance controlling for individual and state-level characteristics stratified by race, 2017

| Odds for No Health Insurance |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Sample | White Non-Hispanic |

Black Non-Hispanic |

Hispanic |

Asian Non-Hispanic |

Native Non-Hispanic |

Other Non-Hispanic |

|||||||

| Adjusted |

Adjusted |

Adjusted + CPVI |

Adjusted |

Adjusted + CPVI |

Adjusted |

Adjusted + CPVI |

Adjusted |

Adjusted + CPVI |

Adjusted |

Adjusted + CPVI |

Adjusted |

Adjusted + CPVI |

|

| OR | OR | OR | OR | OR | OR | OR | OR | OR | OR | OR | OR | OR | |

| 95%CI | 95%CI | 95%CI | 95%CI | 95%CI | 95%CI | 95%CI | 95%CI | 95%CI | 95%CI | 95%CI | 95%CI | 95%CI | |

| State Characteristics | |||||||||||||

| Cost of Voting Index (COVI) Z-Score | 1.25 | 1.02 | 0.95 | 1.18 | 1.17 | 1.18 | 1.05 | 1.45 | 1.34 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 1.12 | 1.14 |

| (1.22,1.28) | (0.97,1.07) | (0.93,0.97) | (1.13,1.22) | (1.13,1.21) | (1.15,1.21) | (1.03,1.07) | (1.27,1.66) | (1.18,1.53) | (0.71,1.14) | (0.77,1.08) | (1.06,1.18) | (1.06,1.23) | |

| Cook Partisan Voting Index (CPVI) Z-Score | 1.29 | 1.78 | 1.75 | 1.07 | 1.18 | 1.64 | |||||||

| (1.25,1.34) | (1.69,1.88) | (1.67,1.83) | (0.89,1.28) | (0.98,1.43) | (1.35,1.99) | ||||||||

| State Median Income Z-score | 1.00 | 0.79 | 0.99 | 0.75 | 1.35 | 0.85 | 1.27 | 0.85 | 0.81 | 0.72 | 0.84 | 0.60 | 1.04 |

| (0.94,1.07) | (0.74,0.85) | (0.94,1.03) | (0.68,0.82) | (1.28,1.44) | (0.79,0.90) | (1.20,1.35) | (0.76,0.96) | (0.66,0.98) | (0.56,0.93) | (0.68,1.04) | (0.52,0.69) | (0.77,1.40) | |

| Proportion Non-Hispanic Black Z-score | 0.92 | 1.17 | 1.19 | 1.08 | 1.35 | 0.97 | 1.45 | 0.80 | 0.85 | 1.17 | 1.06 | 1.07 | 1.03 |

| (0.88,0.96) | (1.08,1.26) | (1.15,1.24) | (1.03,1.13) | (1.28,1.42) | (0.93,1.00) | (1.40,1.49) | (0.68,0.94) | (0.73,0.98) | (0.98,1.40) | (0.95,.19) | (1.00,1.14) | (0.96,1.10) | |

| Proportion Poor Z-score | 0.96 | 0.84 | 1.14 | 0.81 | 0.94 | 0.88 | 1.11 | 0.83 | 1.06 | 0.54 | 0.71 | 0.93 | 0.78 |

| (0.90,1.03) | (0.78,0.90) | (1.09,1.19) | (0.72,0.90) | (0.88,0.99) | (0.82,0.94) | (1.05,1.17) | (0.72,0.95) | (0.85,1.32) | (0.44,0.65) | (0.62,0.81) | (0.80,1.08) | (0.63,0.98) | |

| State Population Z-score | 1.26 | 1.14 | 1.27 | 1.30 | 1.20 | 1.07 | 1.06 | 1.04 | 1.00 | 1.15 | 1.13 | 1.19 | 1.17 |

| (1.23,1.28 | (1.09,1.18) | (1.24,1.29) | (1.25,1.35) | (1.17,1.24) | (1.05,1.08) | (1.05,1.08) | (1.00,1.09) | (0.95,1.06) | (0.25,5.23) | (1.00,1.27) | (1.14,1.24) | (1.11,1.22) | |

| Individual Characteristics | |||||||||||||

| Gender (ref: male) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Female | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.58 | 0.57 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.78 | 0.80 | 0.76 | 0.76 | |

| (0.64,0.78) | (0.65,0.78) | (0.49,0.68) | (0.49,0.68) | (0.53,0.79) | (0.53,0.79) | (0.31,1.03) | (0.31,1.04) | (0.54,1.14) | (0.54,1.18) | (0.52,1.10) | (0.52,1.11) | ||

| Age (ref: 18 to 24 years) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| 25 to 34 | 1.54 | 1.54 | 1.07 | 1.06 | 1.47 | 1.48 | 1.39 | 1.37 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 2.13 | 2.05 | |

| (1.39,1.71) | (1.39,1.71) | (0.81,1.41) | (0.80,1.39) | (1.11,1.96) | (1.11,1.97) | (0.70,2.75) | (0.69,2.72) | (0.14,0.88) | (0.15,0.90) | (1.01,4.46) | (0.95,4.39) | ||

| 35 to 44 | 1.47 | 1.46 | 0.83 | 0.82 | 1.34 | 1.35 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.60 | 0.61 | 2.13 | 2.06 | |

| (1.25,1.72) | (1.25,1.71) | (0.68,1.03) | (0.66,1.01) | (0.97,1.85) | (0.97,1.86) | (0.29,2.15) | (0.30,2.07) | (0.32,1.13) | (0.33,1.12) | (0.91,5.00) | (0.84,5.04) | ||

| 45 to 54 | 1.07 | 1.07 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 2.12 | 2.10 | 0.31 | 0.32 | 1.84 | 1.76 | |

| (0.92,1.24) | (0.92,1.24) | (0.64,0.96) | (0.64,0.95) | (0.62,1.03) | (0.62,1.03) | (1.30,3.47) | (1.28,3.42) | (0.11,0.92) | (0.11,0.93) | (0.86,3.93) | (0.80,3.90) | ||

| 55 to 64 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 1.18 | 1.17 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.86 | 0.82 | |

| (0.60,0.84) | (0.60,0.84) | (0.39,0.64) | (0.39,0.63) | (0.36,0.61) | (0.36,0.61) | (0.36,3.89) | (0.36,3.80) | (0.02,0.36) | (0.02,0.34) | (0.39,1.92) | (0.35,1.93) | ||

| Marital Status (ref: married) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Single | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.45 | 1.45 | 1.03 | 1.02 | 1.45 | 1.42 | 0.85 | 0.90 | 0.98 | 0.97 | |

| (1.11,1.30) | (1.10,1.30) | (1.18,1.79) | (1.18,1.78) | (0.85,1.24) | (0.85,1.24) | (1.03,2.03) | (1.00,2.02) | (0.41,1.77) | (0.44,1.81) | (0.64,1.52) | (0.61,1.55) | ||

| Household Income (ref: less than $10,000) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| $10,001 to 15,000 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.78 | 0.79 | 1.11 | 1.15 | 1.74 | 1.73 | 1.43 | 1.49 | |

| (0.79,1.07) | (0.79,1.07) | (0.66,1.34) | (0.67,1.34) | (0.71,0.87) | (0.71,0.87) | (0.35,3.52) | (0.34,3.89) | (0.56,5.41) | (0.59,5.04) | (0.74,2.79) | (0.76,2.93) | ||

| $15,001 to 20,000 | 1.23 | 1.24 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 1.62 | 1.65 | 0.50 | 0.47 | 1.29 | 1.26 | |

| (1.05,1.44) | (1.06,1.45) | (0.68,1.11) | (0.70,1.13) | (0.73,1.13) | (0.73,1.13) | (0.79,3.34) | (0.78,3.46) | (0.10,2.40) | (0.10,2.28) | (0.75,2.20) | (0.73,2.18) | ||

| $20,001 to 25,000 | 1.15 | 1.15 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 1.26 | 1.27 | 1.35 | 1.35 | 1.40 | 1.41 | |

| (0.94,1.42) | (0.93,1.41) | (0.64,1.18) | (0.65,1.20) | (0.67,0.95) | (0.67,0.95) | (0.49,3.26) | (0.49,3.30) | (0.38,4.80) | (0.40,4.53) | (0.84,2.33) | (0.84,2.39) | ||

| $25,001 to 35,000 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.69 | 0.71 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 1.18 | 1.20 | 1.07 | 1.09 | 1.17 | 1.20 | |

| (0.72,1.07) | (0.72,1.07) | (0.51,0.95) | (0.52,0.96) | (0.48,0.70) | (0.48,0.71) | (0.67,2.07) | (0.67,2.14) | (0.29,4.00) | (0.31,3.80) | (0.54,2.53) | (0.55,2.62) | ||

| $35,001 to 50,000 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.65 | 0.63 | 1.21 | 1.21 | |

| (0.54,0.81) | (0.54,0.81) | (0.42,0.75) | (0.41,0.75) | (0.27,0.72) | (0.27,0.72) | (0.26,0.95) | (0.25,0.98) | (0.18,2.30) | (0.08,2.21) | (0.71,2.08) | (0.70,2.09) | ||

| $50,001 to 75,000 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.39 | 0.42 | 1.04 | 1.05 | |

| (0.32,0.55) | (0.32,0.54) | (0.22,0.48) | (0.22,0.48) | (0.17,0.45) | (0.17,0.46) | (0.08,0.48) | (0.08,0.50) | (0.06,2.55) | (0.08,2.21) | (0.56,1.93) | (0.56,1.94) | ||

| Greater than 75,000 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.46 | 0.46 | |

| (0.19,0.29) | (0.19,0.29) | (0.11,0.34) | (0.11,0.35) | (0.08,0.22) | (0.08,0.23) | (0.11, 0.42) | (0.11, 0.43) | (0.01,0.77) | (0.02,0.67) | (0.21,1.00) | (0.21,1.02) | ||

| Education (ref: less than high school) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| High School | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.66 | 0.67 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 1.21 | 1.23 | 0.69 | 0.68 | 0.38 | 0.37 | |

| (0.50,0.73) | (0.50,0.73) | (0.52,0.85) | (0.52,0.85) | (0.48,0.86) | (0.47,0.86) | (0.84,1.75) | (0.85,1.78) | (0.42,1.11) | (0.42,1.09) | (0.23,0.64) | (0.23,0.61) | ||

| Some College | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.34 | 0.33 | |

| (0.38,0.55) | (0.38,0.55) | (0.51,0.71) | (0.50,0.70) | (0.26,0.39) | (0.26,0.39) | (0.38,1.38) | (0.39,1.42) | (0.04,0.63) | (0.04,0.65) | (0.20,0.60) | (0.19,0.58) | ||

| College degree | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.19 | |

| (0.21,0.31) | (0.21,0.31) | (0.27,0.47) | (0.27,0.46) | (0.24,0.38) | (0.24,0.38) | (0.44,0.93) | (0.44,0.94) | (0.10,0.62) | (0.09,0.60) | (0.11,0.36) | (0.10,0.34) | ||

Likewise, when stratified by household income (Table 3), a one standard deviation increase in COVI was associated with an increase in being uninsured for low-income groups with earnings ≤$35,000 (OR=1.32, 95% CI=1.26,1.38) and among middle-income groups with earnings between $35,000 to $75,000 (OR=1.20, 95% CI=1.16, 1.24). However, no association was observed among those with household incomes over $75,000.

Table 3.

The relationship between Cost of Voting Index and odds for no health insurance controlling for individual and state-level characteristics, stratified by household income 2017

| Odds for No Health Insurance |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Sample | Household Income ≤35K | Household Income 35K to 75K | Household Income >75K | ||||||

| Adjusted | Adjusted | Adjusted + CPVI | Adjusted | Adjusted + CPVI | Adjusted | Adjusted + CPVI | |||

| OR | OR | OR | OR | OR | OR | OR | |||

| 95%CI | 95% CI | 95% CI | 95% CI | 95% CI | 95% CI | 95% CI | |||

| State Characteristics | |||||||||

| Cost of Voting Index (COVI) Z-Score | 1.25 | 1.32 | 1.04 | 1.20 | 1.03 | 1.05 | 1.04 | ||

| (1.22,1.28) | (1.26,1.38) | (1.03,1.06) | (1.16,1.24) | (1.00,1.06) | (0.99,1.11) | (0.98,1.11) | |||

| Cook Partisan Voting Index (CPVI) Z-Score | 0.89 | 1.40 | 1.20 | ||||||

| (0.84,0.94) | (1.32,1.48) | (1.12,1.28) | |||||||

| State Median Income Z-score | 1.00 | 0.84 | 1.22 | 1.07 | 1.03 | 0.78 | 0.94 | ||

| (0.94,1.07) | (0.75,0.93) | (1.16,1.28) | (1.00,1.14) | (0.97,1.09) | (0.71,0.86) | (0.84,1.05) | |||

| Proportion Non-Hispanic Black Z-score | 0.92 | 1.29 | 0.91 | 1.05 | 1.06 | 1.04 | 1.07 | ||

| (0.88,0.96) | (1.21,1.36) | (0.86,0.95) | (1.00,1.10) | (1.02,1.10) | (0.97,1.11) | (1.00,1.15) | |||

| Proportion Poor Z-score | 0.96 | 0.71 | 1.01 | 0.94 | 0.87 | 0.90 | 0.96 | ||

| (0.90,1.03) | (0.65,0.78) | (0.97,1.06) | (0.89,1.01) | (0.82,0.92) | (0.81,0.99) | (0.87,1.06) | |||

| State Population Z-score | 1.26 | 1.12 | 1.18 | 1.17 | 1.15 | 1.14 | 1.10 | ||

| (1.23,1.28 | (1.09,1.14) | (1.17,1.20) | (1.14,1.19) | (1.13,1.18) | (1.10,1.19) | (1.06,1.14) | |||

| Individual Characteristics | |||||||||

| Gender (ref: male) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Female | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.75 | 0.75 | |||

| (0.57,0.71) | (0.57,0.71) | (0.73,1.00) | (0.74,1.00) | (0.70,0.80) | (0.70,0.80) | ||||

| Age (ref: 18 to 24 years) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 25 to 34 | 1.44 | 1.44 | 1.43 | 1.42 | 2.03 | 2.02 | |||

| (1.26,1.65) | (1.26,1.65) | (1.04,1.97) | (1.03,1.97) | (1.83,2.25) | (1.82,2.24) | ||||

| 35 to 44 | 1.29 | 1.29 | 1.52 | 1.52 | 1.50 | 1.49 | |||

| (1.09,1.53) | (1.09,1.53) | (1.24,1.87) | (1.23,1.87) | (1.34,1.68) | (1.34,1.67) | ||||

| 45 to 54 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 1.07 | 1.07 | 1.18 | 1.18 | |||

| (0.81,1.06) | (0.81,1.06) | (0.82,1.39) | (0.82,1.39) | (1.06,1.32) | (1.05,1.32) | ||||

| 55 to 64 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.87 | 0.87 | |||

| (0.50,0.66) | (0.50,0.66) | (0.58,0.78) | (0.57,0.77) | (0.77,0.99) | (0.77,0.98) | ||||

| Race (ref: White) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.18 | 1.18 | 1.17 | 1.17 | |||

| (0.89,1.17) | (0.89,1.17) | (1.02,1.35) | (1.03,1.36) | (1.03,1.32) | (1.03,1.33) | ||||

| Hispanic | 2.28 | 2.28 | 1.66 | 1.67 | 1.55 | 1.56 | |||

| (1.97,2.64) | (1.97,2.64) | (1.29,2.13) | (1.30, 2.14) | (1.41,1.70) | (1.42,1.70) | ||||

| Asian | 1.15 | 1.15 | 0.58 | 0.59 | 1.16 | 1.16 | |||

| (0.94,1.41) | (0.94,1.41) | (0.26,1.27) | (0.26,1.31) | (0.96,1.40) | (0.96,1.41) | ||||

| Native | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.50 | 0.47 | 0.78 | 0.76 | |||

| (0.40,1.04) | (0.40,1.04) | (0.18,1.36) | (0.17,1.29) | (0.57,1.05) | (0.56,1.04) | ||||

| Other | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.53 | 1.52 | 1.34 | 1.33 | |||

| (0.85,1.16) | (0.85,1.16) | (1.08,2.17) | (1.07,2.16) | (1.16,1.55) | (1.15,1.54) | ||||

| Marital Status (ref: married) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Single | 1.11 | 1.11 | 1.18 | 1.17 | 2.15 | 2.16 | |||

| (0.97,1.27) | (0.97,1.27) | (1.03,1.34) | (1.03,1.34) | (2.02,2.30) | (2.02,2.30) | ||||

| Education (ref: less than high school) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| High School | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.45 | 0.45 | |||

| (0.58,0.75) | (0.58,0.75) | (0.33,0.47) | (0.33,0.46) | (0.41.49) | (0.41,0.50) | ||||

| Some College | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.27 | 0.27 | |||

| (0.39,0.51) | (0.39,0.51) | (0.21,0.35) | (0.20,0.34) | (0.24,0.30) | (0.24,0.30) | ||||

| College degree | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.13 | |||

| (0.29,0.40) | (0.29,0.41) | (0.12,0.19) | (0.11,0.19) | (0.12,0.15) | (0.12,0.15) | ||||

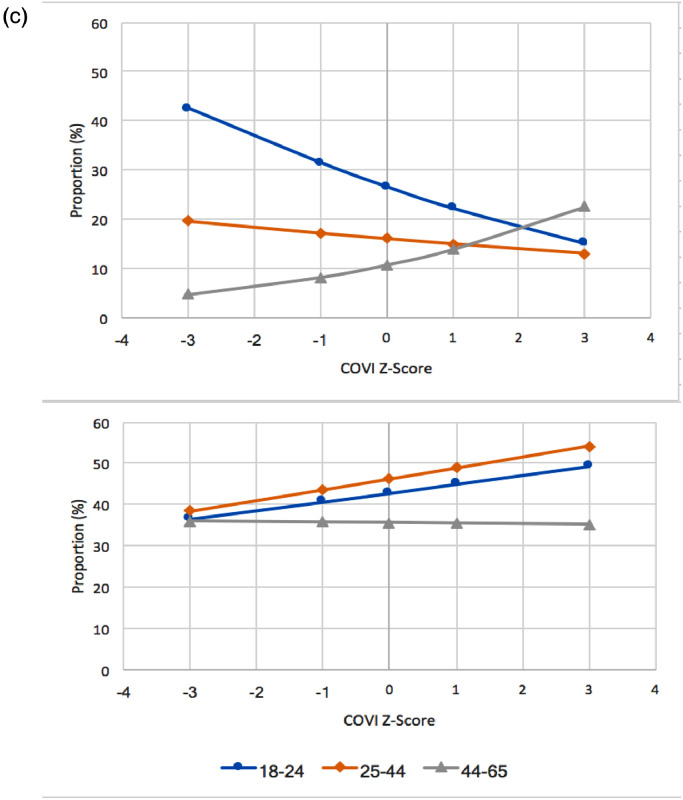

When analyses were stratified by age group (Table 4), the associations between COVI and being uninsured was observed among those aged 18-24 years (OR=1.22, 95% CI=1.20, 1.24) and 25-44 years (OR=1.27, 95% CI=1.24, 1.31), but not among those aged 45-65 years. These crude and adjusted heterogeneous associations across racial, socioeconomic, and age groups are displayed in Figures 1a-1c. We find that higher COVI scores are inversely associated with access to health care among non-white, lower socioeconomic status, and younger demographic groups, in comparison with those from white, higher socioeconomic, and older groups.

Table 4.

The relationship between Cost of Voting Index and odds for no health insurance controlling for individual and state-level characteristics, stratified by age group 2017

| Odds for No Health Insurance |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Sample | Age 18-24 | Age 25-44 | Age 45-65 | ||||||

| Adjusted | Adjusted | Adjusted + CPVI | Adjusted | Adjusted + CPVI | Adjusted | Adjusted + CPVI | |||

| OR | OR | OR | OR | OR | OR | OR | |||

| 95%CI | 95% CI | 95% CI | 95% CI | 95% CI | 95% CI | 95% CI | |||

| State Characteristics | |||||||||

| Cost of Voting Index (COVI) Z-Score | 1.25 | 1.22 | 1.13 | 1.27 | 1.05 | 0.98 | 0.96 | ||

| (1.22,1.28) | (1.20,1.24) | (1.11,1.15) | (1.24,1.31) | (1.02,1.09) | (0.95,1.01) | (0.93,0.99) | |||

| Cook Partisan Voting Index (CPVI) Z-Score | 1.64 | 1.08 | 1.77 | ||||||

| (1.59,1.70) | (1.01,1.16) | (1.65,1.90) | |||||||

| State Median Income Z-score | 1.00 | 0.65 | 0.85 | 0.58 | 1.13 | 0.69 | 1.10 | ||

| (0.94,1.07) | (0.60,0.70) | (0.81,0.92) | (0.55,0.61) | (1.08,1.18) | (0.63,0.75) | (1.04,1.17) | |||

| Proportion Non-Hispanic Black Z-score | 0.92 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1.24 | 1.10 | 1.23 | 1.20 | ||

| (0.88,0.96) | (1.02,1.14) | (1.03,1.15) | (1.20,1.29) | (1.06,1.15) | (1.16,1.29) | (1.14,1.25) | |||

| Proportion Poor Z-score | 0.96 | 0.65 | 0.78 | 0.71 | 0.84 | 0.97 | 0.97 | ||

| (0.90,1.03) | (0.61,0.70) | (0.74,0.82) | (0.67,0.75) | (0.81,0.88) | (0.90,1.05) | (0.93,1.02) | |||

| State Population Z-score | 1.26 | 1.08 | 1.16 | 1.18 | 1.18 | 1.27 | 1.16 | ||

| (1.23,1.28) | (1.07,1.09) | (1.15,1.18) | (1.15,1.21) | (1.15,1.22) | (1.23,1.31) | (1.13,1.19) | |||

| Individual Characteristics | |||||||||

| Gender (ref: male) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Female | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.78 | 0.79 | |||

| (0.51,0.73) | (0.51,0.73) | (0.52,0.69) | (0.52,0.69) | (0.73,0.84) | (0.73,0.84) | ||||

| Race (ref: White) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.47 | 1.47 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 1.05 | 1.06 | |||

| (1.12,1.92) | (1.12,1.93) | (0.80,1.06) | (0.80,1.06) | (0.87,1.27) | (0.88,1.28) | ||||

| Hispanic | 2.39 | 2.39 | 2.13 | 2.13 | 1.96 | 1.98 | |||

| (1.96,2.92) | (1.95,2.91) | (1.70,2.66) | (1.70, 2.67) | (1.71,2.25) | (1.73,2.27) | ||||

| Asian | 1.39 | 1.40 | 0.78 | 0.80 | 1.55 | 1.57 | |||

| (1.03,1.89) | (1.03,1.90) | (0.48,1.28) | (0.49,1.32) | (1.04,2.30) | (1.05,2.34) | ||||

| Native | 1.11 | 1.07 | 0.53 | 0.52 | 0.62 | 0.60 | |||

| (0.50,2.47) | (0.49,2.35) | (0.33,0.86) | (0.32, 0.84) | (0.42,0.93) | (0.40,0.91) | ||||

| Other | 0.80 | 0.81 | 1.18 | 1.17 | 1.21 | 1.20 | |||

| (0.48,1.34) | (0.49,1.34) | (0.94,1.48) | (0.94,1.47) | (0.98,1.49) | (0.97,1.49) | ||||

| Marital Status (ref: married) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Single | 0.97 | 0.98 | 1.08 | 1.08 | 1.20 | 1.20 | |||

| (0.77,1.22) | (0.78,1.23) | (0.99,1.18) | (0.99,1.18) | (1.10,1.31) | (1.11,1.31) | ||||

| Household Income (ref: less than $10,000) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| $10,001 to 15,000 | 1.19 | 1.19 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.65 | 0.66 | |||

| (0.91,1.55) | (0.91,1.56) | (0.76,1.28) | (0.76,1.29) | (0.53,0.80) | (0.53,0.80) | ||||

| $15,001 to 20,000 | 1.19 | 1.19 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 0.89 | 0.89 | |||

| (0.91,1.54) | (0.92,1.55) | (0.92,1.23) | (0.92,1.23) | (0.73,1.07) | (0.73,1.08) | ||||

| $20,001 to 25,000 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.86 | 0.86 | |||

| (0.73,1.18) | (0.73,1.19) | (0.84,1.14) | (0.84,1.13) | (0.71,1.03) | (0.71,1.04) | ||||

| $25,001 to 35,000 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.69 | 0.68 | 0.64 | 0.64 | |||

| (0.71,1.31) | (0.71,1.31) | (0.58,0.82) | (0.58,0.81) | (0.52,0.78) | (0.53,0.78) | ||||

| $35,001 to 50,000 | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.51 | 0.51 | |||

| (0.44,0.71) | (0.44,0.71) | (0.39,0.69) | (0.39,0.69) | (0.40,0.66) | (0.40,0.66) | ||||

| $50,001 to 75,000 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.29 | 0.28 | |||

| (0.20,0.50) | (0.21,0.51) | (0.25,0.47) | (0.25,0.47) | (0.19,0.42) | (0.19,0.42) | ||||

| Greater than 75,000 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.12 | |||

| (0.16,0.36) | (0.16,0.37) | (0.14,0.24) | (0.14,0.24) | (0.08,0.19) | (0.08,0.19) | ||||

| Education (ref: less than high school) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| High School | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.77 | 0.78 | |||

| (0.46,0.75) | (0.46,0.75) | (0.48,0.63) | (0.48,0.63) | (0.70,0.86) | (0.70,0.87) | ||||

| Some College | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.59 | 0.60 | |||

| (0.30,0.47) | (0.30,0.47) | (0.32,0.43) | (0.32,0.43) | (0.52,0.67) | (0.52,0.68) | ||||

| College degree | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.51 | 0.51 | |||

| (0.17,0.31) | (0.16,0.30) | (0.20,0.28) | (0.20,0.28) | (0.43,0.60) | (0.44,0.61) | ||||

Figure 1.

(a). The crude and adjusted relationship between COVI and odds of not having health insurance stratified by race. (b). The crude and adjusted relationship between COVI and odds of not having health insurance stratified by household income. (c). The crude and adjusted relationship between COVI and odds of not having health insurance stratified by age group.

When we added state-level political ideology (i.e., the CPVI), the relationship between COVI and increased odds of having no health insurance remained but was attenuated (OR=1.10, 95% CI=1.07,1.13) (Table 2). Similar findings were obtained across race/ethnicity, socioeconomic, and age groups, with similarly attenuated ORs. The CPVI was also independently associated with increased odds of being uninsured in adjusted models.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to show the relationship between barriers to voting in elections and access to health insurance in the United States. We observed a significant relationship between a validated measure of barriers to voting in elections with the odds of having no health insurance. Barriers to voting or restrictions on the right to vote within a state were associated with increased odds of being uninsured. Furthermore, lower rates of insurance among racial/ethnic minority groups, those with lower socioeconomic status, and younger groups are plausibly explained in part by targeted efforts to restrict voting among these groups.

When the political ideology of a state is added to the model, we see a large attenuation of the relationship between one's barriers to voting and access to health insurance. This suggests that political ideology is a powerful driver of placing barriers to, or outright restrictions on, voting. Republican efforts to impede voter's access to the ballot box also appear to translate into policy changes within the state. However, it also suggests that barriers to voting may not be the only factor hindering either voting or enrolling in public health insurance. The residual effect that remains after controlling for political ideology can be plausibly explained by: 1) the nature of the CPVI score; 2) efforts by Democrats to also hinder voting; and 3) socio-demographic correlates of voter participation. The CPVI is a fairly blunt measure when applied at the state level. For example, it does not account for factors such as gerrymandering, which can lead to a representation by a minority of voters. There is limited evidence of Democratic efforts to enact direct barriers to voting, but Democrats do implement anti-democratic policies such as gerrymandering [30]. Finally, ethnic minority groups appear to be less likely to vote than majority Whites in most elections. Likewise, voter participation tends to increase with income and age.

Voter restrictions that prevent racialized minorities from participating in the democratic process are an example of structural racism. Moreover, findings indicate that these restrictions prevent individuals from other socioeconomic groups, such as young adults and those from low-income households from voting. Since the Shelby County decision of 2013, states began to enact structural voting barriers that lead to the inequitable distribution of power by race, social class, and age. Political scientists note that Republican party efforts to impede voting by ethnic minority groups have increased momentum since the civil rights movement [31]. This may be attributable in part to the changing demographics of the United States, while increasing rolls of minority voters are more likely to vote for Democratic candidates [31,32]. This lack of access to power and representation may subsequently lead to difficulties in access to social resources that would otherwise be beneficial to health (e.g., education and health care). Thus, addressing racial and income inequalities in health in the US will require legislative activism to ensure all citizens have the equitable right to vote.

Previous studies have shown that racial/ethnic minorities, younger people, and those from low SES groups are both less likely to vote and are more likely to experience adverse health outcomes [9]. In addition, previous research has shown that SES in childhood is associated with subsequent voting behaviors in adulthood [33]. The common mechanism involved indicate that those who are more likely to vote are more likely to have higher levels of social cohesion, which in turn is linked with better health outcomes [34]. With this current investigation, we offer an alternative theory by studying unjust upstream and structural factors, which represents the disproportionate difficulties certain groups face when trying to vote in elections. As a result, these groups are less likely to have elected officials represent their interests-interests that could benefit their health. This is concordant with a recent study that found voting reductions followed Medicaid reductions in one state [35].

Implications of these findings underscore how access, or the lack of access, to power is associated with disparities in access to health care, which support the Ecosocial Theory of Disease Distribution [18]. Suppressing the non-Hispanic Black vote is reminiscent of Jim Crow laws and is a form of structural racism [18]. The resulting disproportionate access to health care, thus, has the potential to explain disparities in other health outcomes such as chronic and infectious diseases. Findings also provide evidence of the need for laws that assist rather than hinder minority and underserved groups in voting. For example, one study found that providing opportunities for early voting increased voter turnout on Indian reservations [36]. In addition, laws that currently make voting more difficult should be repealed. Research has shown that reducing these barriers increases voter turnout [7]. Non-partisan interventions can be implemented that promote comprehensive, nonpartisan voter engagement through registration, mobilization, education, and protection of all voters [32]. While registration requirements are themselves a barrier, increasing voter registration is one way to increase engagement in voting. Racial/ethnic minorities, low-income residents, and young people are more likely to be unregistered and to experience barriers in voting registration. 2 Also, rather than preventing people from racial, income, and age socio-demographic groups from voting, political parties should woo these voters rather than prevent them from participating in this democratic right.

The results of this study should be interpreted with caution due to several limitations. First, the study design utilized was cross-sectional thus temporality and causation cannot be inferred. Nonetheless, our analysis focuses on spatial variation between states in barriers to voting after accounting for individual characteristics that may predict voting behavior independent of state of residence. Future studies could include a temporal element that examines insurance status before and after the implementation of barriers to voting. States that opted out of Medicaid expansion are also more likely to have enacted barriers to voting [35]. However, the provision of insurance may also increase trust in the political system. In one randomized-controlled trial, those randomized to Medicaid expansion were more likely to both register to vote and vote in the November 2008 Presidential election [37].

Second, we did not have access to data that may help explain the mechanisms involved. For example, voting behavior among the individual BRFSS respondents was not measured. Thus, we were not able to determine if voting laws lead to votes for governments that enacted laws that made health care insurance more accessible. Future investigations could include a mediation analyses so that we can gain a better understanding of the link between voting restriction laws and disparities in access to health insurance. We also chose not to conduct a formal mediation analysis for CPVI given the measure's weak predictive power for COVI.

Health insurance is designed to provide financial protections, but may not in of itself directly lead to positive health outcomes. Future research could therefore also determine whether the COVI is directly associated with measurable health outcomes, and whether health insurance mediates this relationship. A percentage of the sample was removed due to missing data or nonresponse, which could have resulted in selection bias. Therefore, estimates may be biased towards the null as our sample disproportionately excluded non-whites and those from low household income backgrounds. Finally, we could not distinguish the specific type of health insurance coverage for each respondent due to a large amount of missingness in the variable that measured primary source of health insurance. Were we able to, we would have had the ability to determine whether lower voter restrictions were associated with government issued health insurance coverage or whether coverage type varied by race.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that barriers or restrictions to the right to vote are associated with increased odds in having no health insurance. In states with laws that prove to be difficult for members of sociodemographic groups to vote in elections, people were less likely to have access to health care coverage. This makes government less accountable to the needs of all people. Research is needed to further examine the longitudinal relationship between laws that make it difficult to vote and access to health insurance in order to determine if these associations are causal and to determine the mechanisms involved. Such knowledge may help develop interventions to help those who are more likely to be disenfranchised. By doing so, access to power, a known social determinant of health, will be equitably distributed. This will decrease disparities in health insurance status between groups and eventually may help decrease health inequities.

Contributors

RP conceptualized the research question, conducted all data analyses, interpreted the results, wrote the manuscript, and took the lead in responding to the reviewer comments. SYL provided guidance with the analyses, helped interpret the results, and helped to write the manuscript. EG helped to develop the conceptual framework, interpreted the findings, consulted with writing the manuscript, and conceptualized the public health implications. DMC helped to develop the conceptual framework, interpreted the findings, consulted with writing the manuscript, and provided background knowledge. PM helped frame the research question, interpreted the findings, consulted with writing the manuscript, provided background knowledge, and identified public health implications.

Declaration of Interests

Daniel M. Cook is an Officer of the Nevada Faculty Alliance.

Data Sharing Statement

Data is available at: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/annual_2017.html

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.lana.2021.100026.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Brennan Center For Justice . 2021. Voting Laws Roundup: Accessed on February 25, 2021. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/voting-laws-roundup-february-2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2.United States Census Bureau . 2018. Voting and Registration in the Election of November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson RT, Feldman M. The New Voter Suppression. 2020 https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/new-voter-suppression accessed May 31, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah P, Smith R. Legacies of Segregation and Disenfranchisement: The Road from Plessy to Frank and Voter ID Laws in the United States. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences. 2021;7(1):134–146. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grogan CM, Park SE. The Racial Divide in State Medicaid Expansions. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2017;42(3):539–572. doi: 10.1215/03616878-3802977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Navarro V. What is Happening in the United States? How Social Classes Influence the Political Life of the Country and its Health and Quality of Life. Int J Health Serv. 2021;51(2):125–134. doi: 10.1177/0020731421994841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hajnal Z, Lajevardi N, Nielson L. Voter Identification Laws and the Suppresion of Minority Votes. The Journal of Politics. 2017;79(2):363–379. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown CL, Raza D, Pinto AD. Voting, health and interventions in healthcare settings: a scoping review. Public Health Rev. 2020;41:16. doi: 10.1186/s40985-020-00133-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reeves A, Mackenbach JP. Can inequalities in political participation explain health inequalities? Soc Sci Med. 2019;234 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen RA, Cha AE, Martinez ME, Terlizzi EP. Health Insurance Coverage: Early Release of Estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 2019. National Center for Health Statistics. 2020 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaffney A, McCormick D. The Affordable Care Act: implications for health-care equity. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1442–1452. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30786-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agenor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453–1463. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sommers BD, MC Mc, Blendon RJ, Benson JM, Sayde JM. Beyond Health Insurance: Remaining Disparities in US Health Care in the Post-ACA Era. Milbank Q. 2017;95(1):43–69. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wehby GL, Lyu W. The Impact of the ACA Medicaid Expansions on Health Insurance Coverage through 2015 and Coverage Disparities by Age. Race/Ethnicity, and Gender. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(2):1248–1271. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cha AE, Cohen RA. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2019. Reasons for being uninsured among adults aged 18–64 in the United States. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tobert J, Orgera K. 2020. Key Facts about the Uninsured Population. https://www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/key-facts-about-the-uninsured-population/(accessed January 11 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krieger N. Measures of Racism, Sexism, Heterosexism, and Gender Binarism for Health Equity Research: From Structural Injustice to Embodied Harm-An Ecosocial Analysis. Annu Rev Public Health. 2020;41:37–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040119-094017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krieger N. Climate crisis, health equity, and democratic governance: the need to act together. J Public Health Policy. 2020;41(1):4–10. doi: 10.1057/s41271-019-00209-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.United States Supreme Court . Vol. 570. 2014. pp. 12–96. (Shelby County v. Holder, No.). [Google Scholar]

- 20.The United States Department of Justice . 2017. History of Federal Voting Rights Laws: The Voting Rights Act of 1965. https://www.justice.gov/crt/history-federal-voting-rights-laws (accessed January 4, 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crum T. The Voting Rights Act's Secret Weapon: Pocket Trigger Litigation and Dynamic Preclearance. The Yale Law Journal. 2010:119. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feder C, Miller M. Voter Purges After Shelby. American Politics Research. 2020;48(6):687–692. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brunell T, Manzo W. The Voting Rights Act After Shelby County v. Holder: A Potential Fix to Revive Section 5. Transatlantica. 2015;1 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers of Disease Control and Prevention . 2017. About BRFSS. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers of Disease Control and Prevention . BRFSS; 2017. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Overview. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. 2017 Summary Data Quality Report. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Q, Pomante M, Schraufnagel S. Cost of Voting in the American States. Election Law Journal. 2018;17(3):234–247. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wasserman D, Flinn A. 2017. Introducing the 2017 Cook Political Report Partisan Voter Index. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Merlo J, Chaix B, Ohlsson H, et al. A brief conceptual tutorial of multilevel analysis in social epidemiology: using measures of clustering in multilevel logistic regression to investigate contextual phenomena. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(4):290–297. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.029454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kang MS. Gerrymandering and the Constitutional Norm Against Government Partisanship. Mich L Rev. 2017;116:351. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bentele K, O'Brien E. Jim Crow 2.0? Why States Consider and Adopt Restrictive Voter Access Policies. Perspectives on Politics. 2013;11(4):1088–1116. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yagoda N. Addressing Health Disparities Through Voter Engagement. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(5):459–461. doi: 10.1370/afm.2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akee R, Copeland W, Costello E, Holbein J, Simeonvova E. National Bureau of Economic Research; Cambridge, MA: 2018. Family Income and the Intergenerational Transmission of Voting Behavior: Evidence from and Income Intervention. NBER Working Paper Series. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Babey S, Wolstein J, Charles S. UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; Los Angeles, CA: 2020. Better Health, Greater Social Cohesion Linked to Voter Participation. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haselswerdt J, Michener J. Disenrolled: Retrenchment and Voting in Health Polic. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 2019;44(3):423–454. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schroedel J, Rogers M, Dietrich J, Johnston S, Berg A. Assessing the efficacy of early voting access on Indian reservations: evidence from a natural experiment in Nevada. Politics, Groups, and Identities. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baicker K, Finkelstein A. The Impact of Medicaid Expansion on Voter Participation: Evidence from the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment. Quarterly Journal of Political Science. 2019;14:383–400. doi: 10.1561/100.00019026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.