Abstract

Background

Intraprocedural optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a valuable tool for guidance of percutaneous coronary intervention, but long-term follow-up data are lacking.

Aims

The aim of this study was to address the long-term (7.5 years) clinical impact of quantitative OCT metrics of suboptimal stent implantation.

Methods

This retrospective study includes 391 patients with long-term follow-up (mean 2,737 days; interquartile range 1,301-3,143 days) from the multicentre Centro per la Lotta contro l’Infarto - Optimisation of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (CLI-OPCI) registry. OCT-assessed suboptimal stent deployment required the presence of at least one of the following pre-defined OCT findings: in-stent MLA <4.5 mm2, proximal or distal reference lumen narrowing with lumen area <4.5 mm2, significant proximal or distal edge dissection width ≥200 μm.

Results

One hundred and two patients (26.1%) with 138 stented lesions (27.7%) experienced a device-oriented cardiovascular event (DOCE). In-stent MLA <4.5 mm2 (38.1% vs 19.8%, p<0.001), in-stent lumen expansion <70% (29.5% vs 20.3%, p=0.032), proximal reference lumen narrowing <4.5 mm2 (6.5% vs 1.4%, p=0.004), and distal reference lumen narrowing <4.5 mm2 (12.9% vs 3.6%, p=0.001) were significantly more common in the DOCE vs non-DOCE group. OCT-assessed suboptimal stent deployment was an independent predictor of long-term DOCE (HR 2.17, p<0.001), together with bare metal stent implantation (HR 1.73, p=0.003) and prior revascularisation (HR 1.53, p=0.017).

Conclusions

The presence of OCT-assessed suboptimal criteria for stent implantation was related to a worse clinical outcome at very long-term follow-up. This information further supports an OCT-guided strategy of stent deployment.

Introduction

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) provides high-resolution images of coronary arteries and stented segments and can identify interventional details related to stent failure1,2. The Centro per la Lotta contro l’Infarto-Optimisation of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (CLI-OPCI) project was conceived to explore the role of angiographic plus OCT guidance for routine percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI)3,4,5 and to contribute to other studies in the development of metrics for optimal stenting6,7,8. However, because of the relatively recent clinical introduction of OCT, clinical data are mainly limited to 12-month follow-up and rarely exceed 24-36 months9. The present study assessed the longest-term impact of the pre-specified OCT-assessed quantitative criteria as developed within the CLI-OCPI project.

Methods

Study design

The CLI-OCPI project is a retrospective, multicentre PCI registry that only included consecutive cases of stent implantation performed with frequency domain OCT assessment. All patients had a final OCT assessment of the treated vessel that was performed at the end of the procedure. The OCT acquisition length was sufficient to include the stented segments, plus the proximal (when feasible), as well as distal reference segments6. Indications for OCT assessment and its practical utilisation were left to each operator’s discretion, and no formal selection criteria or treatment strategies (e.g., routine stent post-dilation) were prospectively adopted. For the purposes of this study, only OCT findings obtained at the end of the procedure were considered.

All patients provided written informed consent for the index procedure and for follow-up via telephone or direct visit. Ethical approval was waived because of the study’s observational retrospective design.

In the present study, we evaluated the impact of the individual OCT findings and OCT-based assessment of suboptimal stent deployment on the very long-term clinical outcomes of 427 consecutive patients enrolled in the CLI-OPCI project. As per the study protocol, the follow-up time refers to the time at which patients experienced a clinical event. Only patients with a minimum follow-up length of seven years were included.

For the purpose of this study, the incidence of major adverse device-oriented cardiac events (DOCE) was a composite of cardiac mortality, myocardial infarction (MI) not clearly attributable to a non-target vessel (including periprocedural MI defined as creatine kinase myocardial band level >3 times the upper limit of normal), and target lesion revascularisation10. All outcomes were defined according to the recommendations of the Academic Research Consortium11. Endpoint adjudication was performed by a central clinical event committee at the central core laboratory (Rome Heart Research, Rome, Italy), after reviewing blinded relevant source documents.

No extramural funding was used to support this work, and the authors were solely responsible for the design, conduct, and final contents of the study.

Patients and procedures

In consideration of the retrospective study design, treatment choices (access site, stenting technique, drug-eluting stent [DES] utilisation, and additional pharmacological therapy) were made according to local practice. All patients received unfractionated heparin (a bolus of 70 IU/kg with additional doses aimed at achieving an intraprocedural activated clotting time of 250 to 300 s). All patients were pre-treated with 325 mg of aspirin and a loading dose of clopidogrel 600 mg, prasugrel 60 mg, or ticagrelor 180 mg, if they were not already on a maintenance dose. Unless contraindicated, dual antiplatelet therapy was recommended for at least 12 months.

After discharge, patients were followed up via scheduled direct visits (generally, at one and six months and then routinely or as needed) and telephone contacts. In the case of adverse events or new hospitalisation, source documents were obtained and examined in detail.

OCT measurements and definitions

OCT was acquired by means of the frequency domain C7-XR system (St. Jude Medical) with a non-occlusive technique according to a well-standardised method6.

The following post-intervention OCT metrics were assessed:

1. edge dissection: the presence of a linear rim of tissue with a width ≥200 μm and a clear separation from the vessel wall or underlying plaque that was adjacent (<5 mm) to a stent edge;

2. reference lumen narrowing: lumen area <4.5 mm2 in the presence of significant residual plaque adjacent to stent endings;

3. malapposition: stent-adjacent vessel lumen distance >200 µm;

4. in-stent minimum lumen area (MLA) <4.5 mm2;

5. relative in-stent MLA narrowing: MLA <70% of the average reference lumen area;

6. intrastent plaque/thrombus protrusion: tissue prolapsing between stent struts extending inside a circular arc connecting adjacent struts or intraluminal mass ≥500 μm in thickness with no direct continuity with the surface of the vessel wall or highly backscattered luminal protrusion in continuity with the vessel wall and resulting in signal-free shadowing;

7. asymmetry index: ratio between maximum and minimum lumen diameter (MLD) greater than 1.5 mm.

Suboptimal OCT stent deployment required the presence of at least one of the following pre-defined OCT findings: in-stent MLA <4.5 mm2, proximal or distal reference lumen narrowing with lumen area <4.5 mm2, and significant proximal or distal edge dissection width ≥200 μm. These were significantly associated with major adverse cardiac events (MACE) in the CLI-OPCI II study, which included a composite of cardiac mortality, MI not clearly attributable to a non-target vessel (including periprocedural MI defined as creatine kinase myocardial band level >3 times the upper limit of normal), and target lesion revascularisation3,4.

By study design, final OCT images taken at the end of the procedures were analysed off-line at a certified central core laboratory (Euroimage Research, Rome, Italy) whose operators were blinded to procedural characteristics and outcomes.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are reported as mean±standard deviation or median (interquartile range) in case of normal or skewed distribution, respectively; discrete variables are reported as percentages. The Student’s t-test, the Mann-Whitney U test, chi-square statistics, or the Fisher exact test were applied for bivariate analyses as appropriate. Combined adverse events were evaluated using Cox regression analysis and Kaplan-Meier estimates. All study variables were tested for bivariate association with DOCE; if nominally significant (p<0.05), they were evaluated with a Cox regression model to identify independent outcome predictors and to calculate their adjusted hazard ratios (HR) with associated 95% confidence intervals (CI). A two-tailed p-value <0.05 was established as the level of statistical significance for all tests. All statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS-PASW version 22.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics; IBM Corporation).

Results

We reported the findings of 427 patients treated with OCT guided stenting with a medium follow-up of 2,737 days (7.5 years). A list of DES used in the present study is reported in Supplementary Table 1. Thirty-seven patients were lost to follow-up (8.6%) so that 391 patients (91.3%) with a total of 498 lesions entered the present long term CLI-OPCI study. Overall, 102 patients (26.1%) developed DOCE during follow-up. The comparison between the groups with and without DOCE showed a statistically significant difference for age, family history of coronary artery disease (CAD), and prior revascularisation (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of patients according to the follow-up device-oriented cardiovascular events (DOCE).

| Total population (n=391) | Patients with DOCE (n=102) | Patients without DOCE (n=289) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 65 (56-73) | 66 (59-76) | 64 (56-72) | 0.014 |

| Female gender (%) | 71 (18.0) | 18 (18.0) | 53 (18.6) | 0.895 |

| Left ventricle EF (%) | 55 (48-60) | 55 (45-60) | 56 (48-60) | 0.249 |

| Hypertension (%) | 287 (75.0) | 78 (78.8) | 209 (73.9) | 0.328 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia (%) | 250 (65.0) | 64 (64.6) | 186 (65.7) | 0.846 |

| Smoking habit (%) | 129 (34.0) | 38 (38.4) | 91 (32.2) | 0.259 |

| Family history of CAD (%) | 113 (29.0) | 19 (19.3) | 92 (31.8) | 0.012 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 87 (23.0) | 28 (28.3) | 59 (20.8) | 0.129 |

| CKD (%) | 64 (17.0) | 22 (24.2) | 42 (16.0) | 0.080 |

| Multivessel disease (%) | 248 (64.0) | 70 (70.7) | 178 (62.7) | 0.150 |

| Prior MI (%) | 84 (22.0) | 28 (28.3) | 56 (19.9) | 0.082 |

| Prior revascularisation (%) | 113 (29.0) | 39 (38.4) | 76 (26.5) | 0.026 |

| Acute coronary syndrome (%) | 233 (61.0) | 64 (64.0) | 169 (59.9) | 0.473 |

| STEMI (%) | 119 (31.0) | 28 (28.0) | 91 (32.2) | 0.428 |

| NSTEMI (%) | 35 (9.0) | 13 (13.0) | 22 (7.8) | 0.122 |

| Unstable angina (%) | 79 (21.0) | 23 (23.0) | 56 (19.9) | 0.505 |

| Stable angina (%) | 149 (39.0) | 36 (36.0) | 113 (40.1) | 0.473 |

| Expressed as median and interquartile range. CAD: coronary artery disease; CKD: chronic kidney disease (GFR ≤60 ml∕min∕1.73 m²); DOCE: device-oriented cardiovascular events; EF: ejection fraction; MI: myocardial infarction; NSTEMI: non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction; STEMI: ST-elevation myocardial infarction | ||||

Lesion analysis

Lesions in the DOCE group were located more frequently in the left circumflex artery and less often in the right coronary artery. Additionally, more lesions were treated with bare metal stents (BMS) in the group with DOCE (39.1% vs 25.2% in the non-DOCE group, p=0.002) (Table 2).

Table 2. Lesion and procedural characteristics according to the follow-up device-oriented cardiovascular events (DOCE).

| All lesions (n=498) | Lesions with DOCE (n=138) | Lesions without DOCE (n=360) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locations of treated lesions | ||||

| Left main (%) | 29 (5.4) | 10 (7.2) | 14(3.9) | 0.110 |

| Left anterior descending artery (%) | 283 (52.3) | 77 (55.4) | 203 (56.5) | 0.941 |

| Left circumflex artery (%) | 117 (21.6) | 27 (30.0) | 89 (20.5) | 0.048 |

| Right coronary artery (%) | 108 (20.0) | 10 (11.1) | 92 (21.2) | 0.028 |

| Characteristics of treated lesions | ||||

| Ellis class B2∕C (%) | 448 (82.8) | 117(84.2) | 299 (83.3) | 0.711 |

| Calcific lesion (%) | 75 (15.5) | 24 (17.3) | 44 (12.3) | 0.149 |

| Ostial lesion (%) | 31 (6.4) | 8 (5,8) | 21 (5,8) | 0.970 |

| Bifurcation lesion (%) | 68 (13.9) | 17(12.2) | 51 (14.2) | 0.104 |

| Chronic occlusion (%) | 9 (1.9) | 2 (1,4) | 6 (1.7) | 0.862 |

| In-stent restenosis lesion (%) | 26 (5.7) | 6 (6.5) | 20 (5.5) | 0.718 |

| Stent thrombosis lesion (%) | 15 (3.3) | 2 (2.1) | 13 (3.6) | 0.469 |

| Procedural aspects | ||||

| Direct stenting (%) | 122 (27.9) | 24 (27.9) | 98 (27.9) | 0.998 |

| Thrombectomy use (%) | 62 (12.8) | 10 (10.8) | 52 (13.3) | 0.509 |

| Post-dilatation (%) | 278 (62.5) | 51 (57.3) | 227 (63.8) | 0.260 |

| DES (%) | 342 (68.7) | 84 (60.8) | 269 (74.7) | 0.041 |

| BMS (%) | 156 (31.1) | 54 (39.1) | 91 (25.2) | 0.002 |

| Overlapping stent (%) | 123 (22.7) | 28 (20.1) | 85 (23.7) | 0.349 |

| Optimal angiographic result (%) | 487 (97.8) | 135 (97.8) | 350 (97.4) | 0.842 |

| Stent diameter (mm) | 3.0 (2.6-3.2) | 2.91 (2.5-3.2) | 2.98 (2.7-3.2) | 0.110 |

| Stent length (mm) | 18 (15-28) | 21.7 (13-28) | 23.5 (15-28) | 0.125 |

| Max deployment pressure | 16 (14-18) | 15.6 (14-18) | 15.9 (14-18) | 0.446 |

| Contrast dye (ml) | 242 (200-300) | 248 (182-300) | 259 (200-200) | 0.226 |

| Expressed as median and interquartile range. BMS: bare metal stent; DES: drug-eluting stent; DOCE: device-oriented cardiovascular events | ||||

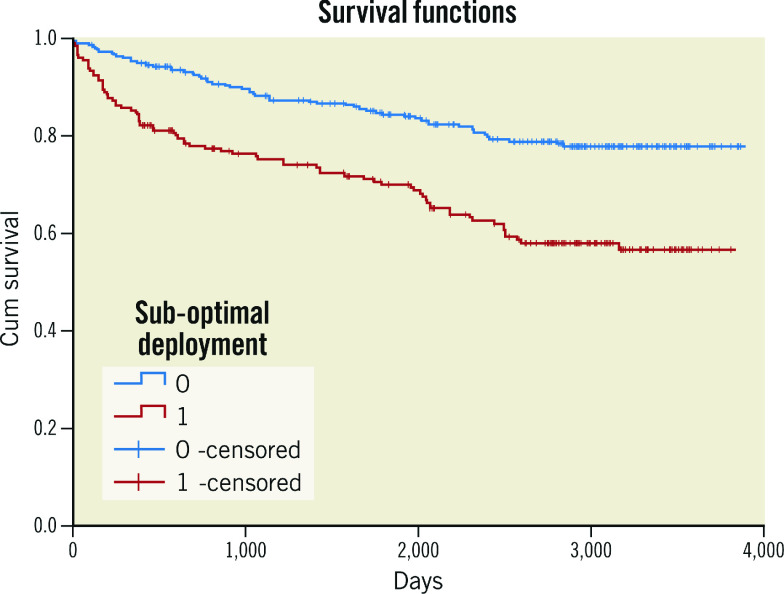

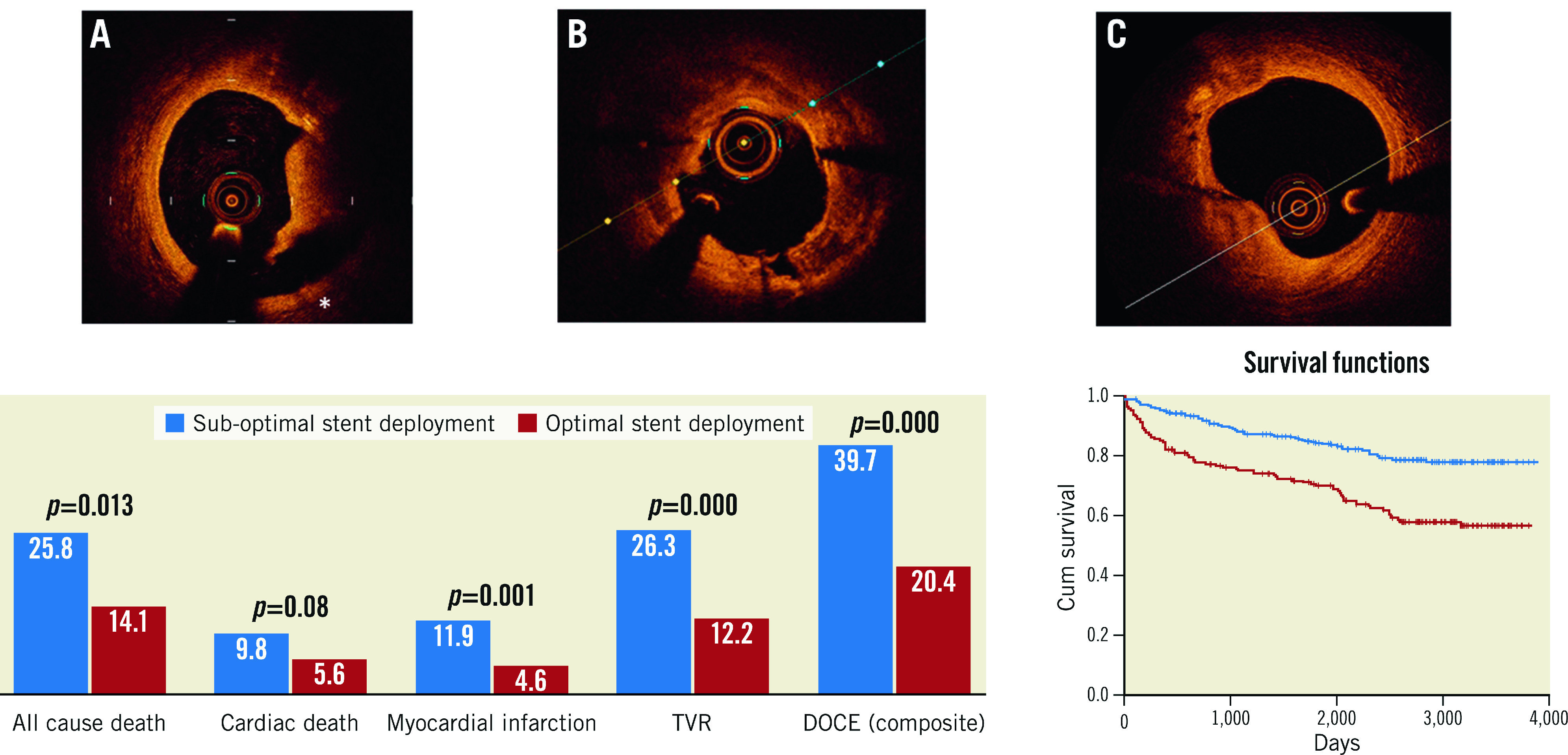

Multivariate Cox hazard analysis confirmed OCT-assessed suboptimal stent deployment to be an independent predictor of long-term DOCE (HR 2.17, p<0.001), together with BMS implantation (HR 1.73, p=0.003) and prior revascularisation (HR 1.53, p=0.017) (Figure 2), Central illustration).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier curves of OCT-assessed suboptimal versus optimal stent deployment for DOCE.

DOCE: device-oriented cardiac events; OCT: optical coherence tomography

Central illustration. OCT-assessed suboptimal stent deployment required the presence of at least one of the following pre-defined OCT findings: A) Significant proximal or distal edge dissection (*) width ≥200 μm; B) intra-stent minimum lumen area <4.5 mm²; C) proximal or distal reference lumen narrowing with lumen area <4.5 mm2.

DOCE: device-oriented cardiovascular events; TVR: target vessel revascularisation

Excluding DOCE occurring in the first year

After exclusion of the 44 patients (95 lesions) who experienced a DOCE in the first year of follow-up, stented lesions in the “DOCE beyond one year” group exhibited the following post-intervention OCT findings: smaller MLD (2.31±0.54 mm vs 2.44±0.53 mm, p=0.03) and a trend toward a smaller MLA (5.66±2.06 mm2 vs 6.11±2.25 mm2, p=0.08). Malapposition length was significantly longer in the non-DOCE group (9.63±23.63 mm vs 4.06±23.63 mm in the DOCE group, p=0.025) (Table 5).

Table 5. OCT findings (DOCE vs no DOCE) after excluding patients with DOCE in the first year.

| All lesions (n=454) | Lesions with DOCE (n=94) | Lesions without DOCE (n=360) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-stent MLA (mm2) | 6.01±2.22 | 5.66±2.06 | 6.11±2.25 | 0.08 |

| Diameter minimum (mm) | 2.41±053 | 2.31±0.54 | 2.44±0.53 | 0.03 |

| Diameter maximum (mm) | 3.05±0.76 | 2.94±0.58 | 3.09±0.80 | 0.11 |

| Stent symmetry at MLA site | 1.39±1.32 | 1.44±1.50 | 1.38±1.27 | 0.68 |

| Reference distal lumen area (mm2) | 6.13±3.10 | 6.20±3.15 | 6.12±3.15 | 0.82 |

| Reference proximal lumen area (mm2) | 8.16±3.47 | 7.74±3.56 | 8.28±3.56 | 0.19 |

| Mean reference lumen area (mm2) | 7.10±2.94 | 6.97±3.01 | 7.13±3.01 | 0.65 |

| Stent expansion % | 91.49±38.11 | 85.56±39.70 | 93.26±39.70 | 0.08 |

| Malapposition thickness (mm) | 0.23±0.24 | 0.21±0.25 | 0.24±0.25 | 0.40 |

| Malapposition length (mm) | 8.48±21.48 | 4.06±23.63 | 9.63±23.63 | 0.02 |

| Maximum tissue/thrombus prolapse (mm) | 0.40±0.26 | 0.42±0.26 | 0.39±0.26 | 0.33 |

| Edge dissection distal length (mm) | 0.23±1.03 | 0.31±0.65 | 0.21±0.65 | 0.39 |

| Edge dissection distal width (mm) | 0.40±1.99 | 0.12±2.19 | 0.48±2.19 | 0.14 |

| Edge dissection distal arch (°) | 6.69±24.15 | 7.21±22.28 | 6.55±22.28 | 0.82 |

| Edge dissection proximal length (mm) | 0.21±2.01 | 0.14±2.26 | 0.22±2.26 | 0.75 |

| Edge dissection proximal width (mm) | 0.05±0.15 | 0.07±0.15 | 0.04±0.15 | 0.14 |

| Edge dissection proximal arc (°) | 6.50±20.22 | 9.46±20.23 | 5.67±20.23 | 0.12 |

| In-stent MLA ≤4.5 mm² (%) | 104 (22.91) | 33 (34.74) | 71 (19.78) | 0.004 |

| Distal edge dissection >200 μm (%) | 28 (6.17) | 5 (5.26) | 23 (6.41) | 0.27 |

| Proximal edge dissection >200 μm (%) | 40 (8.81) | 14 (14.74) | 26 (7.24) | 0.039 |

| Edge dissection (any) ≥200 μm (%) | 68 (15.0) | 12 (17.90) | 17 (13.10) | 0.24 |

| In-stent lumen expansion <70% (%) | 101 (22.25) | 28 (29.47) | 73 (20.33) | 0.074 |

| Malapposition ≥200 μm (%) | 223 (49.12) | 45 (47.37) | 178 (49.58) | 0.39 |

| Plaque∕thrombus protrusion ≥500 µm (%) | 124 (27.31) | 24 (25.26) | 100 (27.86) | 0.65 |

| Distal reference narrowing <4.5 mm2 (%) | 22 (4.84) | 9 (9.47) | 13 (3.62) | 0.028 |

| Proximal reference narrowing <4.5 mm2 (%) | 8 (1.76) | 3 (3.16) | 5 (1.39) | 0.37 |

| Reference edge narrowing (any) <4.5 mm2 (%) | 29 (6.39) | 12 (12.63) | 17 (4.74) | 0.009 |

| Suboptimal stent deployment (%) | 167 (41.6) | 48 (51.06) | 119 (33.05) | 0.01 |

| Expressed as mean and standard deviation. DOCE: device-oriented cardiovascular events; MLA: minimum lumen area | ||||

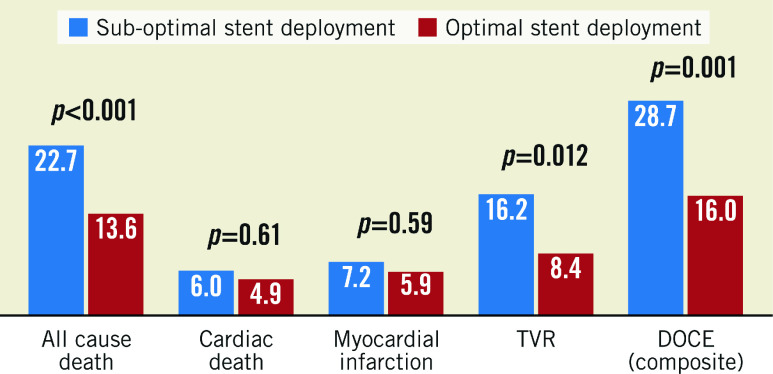

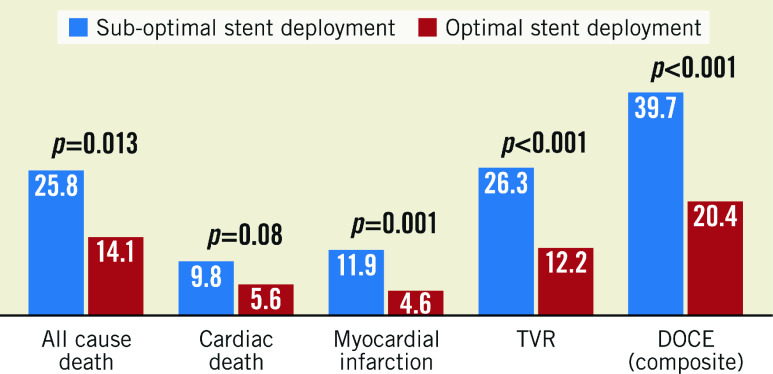

The main composite endpoint (DOCE), all cause death and target vessel revascularisation (TVR) were significantly more common in the lesion group with OCT-assessed suboptimal stent deployment (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Lesions associated with follow-up DOCE after exclusion of patients with DOCE occurring within one year.

DOCE: device-oriented cardiac events; TVR: target vessel revascularisation

Discussion

The present study showed that OCT-assessed post-intervention cut-off metrics predict DOCE at a mean of 7.5 years post-stent implantation, extending the earlier CLI-OPCI registry conclusions to very long-term patient follow-up. This real-world OCT study has, to our knowledge, the most extended OCT follow-up period available in the literature. The criteria for OCT-assessed suboptimal stenting maintain their predictive value independently from CAD presentation and stent type (BMS/DES). OCT-assessed criteria were associated with DOCE even after excluding patients who experienced cardiac events during the first year after intervention. OCT-assessed suboptimal stent deployment is associated with a higher risk of hard cardiac endpoints, especially all-cause mortality, extending conclusions reached at a follow-up time of three years12. Therefore, OCT-assessed suboptimal findings not only predict increased acute/subacute stent thrombosis, in-stent restenosis, or the need for repeat revascularisation, but they also predict mortality, confirming previous OCT findings9.

OCT metrics of suboptimal stenting

The present data confirm the long-term effectiveness of the OCT in-stent MLA <4.5 mm2 cut-off, applied in previous reports from the CLI-OPCI project3,4,5. In-stent MLA ≤4.5 mm² conferred a worse, long-term clinical outcome with an HR of 1.75, slightly lower than the HR observed at one year (HR 2.62, 95% CI: 1.8-3.9, p<0.001)4. Past IVUS studies validated a luminal absolute cut-off of 5 mm2 for non-left main lesions treated with DES13. More recent IVUS studies on first- and second-generation DES deployment suggested a stent MLA of less than 5.0-5.5 mm2 as the best predictor for follow-up events, including DES restenosis and early thrombosis13,14,15,16,17. According to the Does Optical Coherence Tomography Optimize Results of Stenting (DOCTORS) study, an MLA OCT cut-off of 5.44 mm2 was the best predictor of post-procedural fractional flow reserve of 0.9018. In a recent OCT study, Soeda et al investigated the association between post-stenting OCT findings and one-year DOCE, defined as cardiac death, target vessel-related MI, target lesion revascularisation, and stent thrombosis. Minimal DES area <5.0 mm2 was an independent OCT predictor of DOCE at one year (OR 2.54, 95% CI: 1.23-5.25, p=0.012), mainly driven by target lesion revascularisation19.

Absolute versus relative metrics of stent expansion is still a debated issue13,14,16,20,21. The application of an MLA absolute cut-off value seems illogical in the presence of diffusely diseased or small vessels. In contrast with past data with a shorter follow-up3,4,5,19, the present study showed that underexpansion (in-stent lumen area <70% reference lumen areas) can predict DOCE. The present study supports the search for underexpansion, an OCT criterion that has been applied in the ILUMIEN III and IV studies22,23. Surprisingly, different cut-offs of stent underexpansion, such as 80% and 90%, were not able to predict DOCE in our population. Further data will clarify if a more aggressive (greater than 70%) cut-off value will improve the clinical outcome.

In the current long-term follow-up study, reference lumen narrowing at the distal edge <4.5 mm2 (p=0.001) identified lesions at risk of DOCE with an HR of 2.7, similar to earlier reports from the CLI-OPCI project. Furthermore, as a relatively unexpected finding, proximal dissection was associated with a worse outcome.

The role of suboptimal reference metrics in promoting DOCE is by far more important in the first year. Apart from their specific role in favouring target lesion cardiac events, the presence of significant reference narrowings and dissections is probably a marker of extensive atherosclerosis. Consistently, the presence of proximal edge dissections may identify, in later follow-up stages, patients with a more aggressive atherosclerosis located in sites most likely to impact prognosis.

Consistent with previous short- and medium-term findings, malapposition >200 µm did not identify patients at risk of MACE7,24,25. On the other hand, malapposition length was significantly longer in stented lesions without DOCE (4.4±10.3 mm in the DOCE group vs 9.6±23.6 mm, p=0.012). As a plausible explanation, residual stent malapposition tends to occur in large vessels that are at a reduced risk of late cardiac events. In addition, and as in previous studies, thrombus/tissue protrusion and stent asymmetry may have little long-term impact after stent implantation.

Study limitations

As in the past CLI-OPCI project registry studies, the main limitation of the current study resides in its retrospective design. Indeed, this real-world OCT registry included patients with different clinical conditions, with both DES or BMS, and lack of a pre-specified protocol for PCI optimisation. Nevertheless, after correction for the clinical and procedural differences, the presence of non-optimal metrics of stent deployment was confirmed as an independent predictor of DOCE in the multivariate Cox hazard analysis.

Further studies are needed to clarify if the OCT-assessed criteria of suboptimal stent implantation tested in the present study, or other features suggested in a recently published consensus documents7, have a role in predicting coronary events for new-generation DES.

Furthermore, enrolled cases had a relatively low complexity, as shown by the low incidence of coronary bifurcations and total chronic occlusions.

Conclusions

The presence of OCT-assessed criteria of suboptimal stent implantation was related to a worse clinical outcome at very long-term follow-up. This finding supports earlier reports from the CLI-OPCI project that an OCT-guided strategy of stent deployment improves long-term patient outcomes and especially, mortality.

Impact on daily practice

The use of OCT has significantly improved success rates in PCI but long-term data are not yet available. The long-term follow-up data suggest that OCT metrics of suboptimal stent implantation are related to a worse clinical outcome. This finding supports that an OCT-guided strategy of stent deployment improves long-term patient outcomes and especially, mortality. This retrospective study serves to confirm the beneficial role of OCT in PCI. Further additional data from large, randomised trials may provide more compelling evidence on the long-term benefit of OCT-guided PCI.

Supplementary data

List of 498 stents used in the present study.

ROC analysis of in-stent lumen expansion and DOCE with different cut-offs.

Cluster analysis showing the role of suboptimal stent positioning in predicting DOCE and single endpoints in different subgroups.

Figure 1. Lesions associated with follow-up DOCE.

DOCE: device-oriented cardiac events; MLA: minimum lumen area; TVR: target vessel revascularisation

Table 3. OCT findings in patients with and without follow-up device-oriented cardiovascular events (DOCE).

| All lesions (n=498) | Lesions with DOCE (n=138) | Lesions without DOCE (n=360) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-stent MLA (mm2) | 5.94±2.19 | 5.54±1.96 | 6.10±2.25 | 0.009 |

| Diameter minimum (mm) | 2.40±0.53 | 2.30 ± 0.52 | 2.44±0.53 | 0.012 |

| Diameter maximum (mm) | 3.03±0.75 | 2.91± 0.57 | 3.08±0.80 | 0.024 |

| Stent symmetry at MLA site | 1.40±1.38 | 1.45±1.62 | 1.38±1.27 | 0.58 |

| Reference distal lumen area (mm2) | 6.05±3.03 | 5.87±2.67 | 6.12±3.15 | 0.44 |

| Reference proximal lumen area (mm2) | 8.06±3.43 | 7.51±3.08 | 8.29±3.55 | 0.03 |

| Mean reference lumen area (mm2) | 7.02±2.89 | 6.73±2.55 | 7.13±3.01 | 0.17 |

| Stent expansion (%) | 91.22±37.18 | 86.46±29.05 | 93.08±39.79 | 0.08 |

| Malapposition thickness (mm) | 0.23±0.23 | 0.22±0.20 | 0.24±0.25 | 0.38 |

| Malapposition length (mm) | 8.21±20.88 | 4.47±10.38 | 9.66±23.61 | 0.012 |

| Maximum tissue/thrombus prolapse (mm) | 0.40±0.26 | 0.43±0.27 | 0.39±0.26 | 0.19 |

| Edge dissection distal length (mm) | 0.24±1.01 | 0.34±1.61 | 0.21±0.65 | 0.23 |

| Edge dissection distal width (mm) | 0.39±1.92 | 0.16±0.88 | 0.48±2.19 | 0.11 |

| Edge dissection distal arch (°) | 7.48±24.83 | 9.89±30.46 | 6.55±22.28 | 0.19 |

| Edge dissection proximal length (mm) | 0.22±1.95 | 0.20±0.79 | 0.22±2.26 | 0.91 |

| Edge dissection proximal width (mm) | 0.05±0.15 | 0.06±0.15 | 0.04±0.15 | 0.15 |

| Edge dissection proximal arc (°) | 6.67±20.03 | 9.10±19.48 | 5.65±20.20 | 0.10 |

| In-stent MLA ≤4.5 mm² (%) | 124 (24.90) | 53 (38.10) | 71 (19.80) | 0.0001 |

| Distal edge dissection >200 μm (%) | 37 (7.43) | 14 (10.10) | 23 (6.40) | 0.180 |

| Proximal edge dissection >200 μm (%) | 44 (8.84) | 18 (12.90) | 26 (7.20) | 0.073 |

| Edge dissection (any) ≥200 μm (%) | 74 (14.9) | 27 (19.40) | 47 (13.09) | 0.09 |

| In-stent lumen expansion <70% (%) | 114 (22.89) | 41 (29.50) | 73 (20.30) | 0.032 |

| Malapposition ≥200 μm (%) | 243 (48.80) | 65 (46.76) | 178 (49.58) | 0.61 |

| Plaque∕thrombus protrusion ≥500 µm (%) | 164 (32.9) | 49 (35.25) | 115 (31.94) | 0.43 |

| Distal reference narrowing <4.5 mm2 (%) | 31 (6.22) | 18 (12.95) | 13 (3.62) | 0.001 |

| Proximal reference narrowing <4.5 mm2 (%) | 14 (2.81) | 9 (6.47) | 5 (1.39) | 0.004 |

| Reference edge narrowing (any) <4.5 mm2 (%) | 42 (8.43) | 25 (26.30) | 17 (4.73) | <0.000 |

| Sub-optimal stent deployment | 196 (39.3) | 77 (55.8) | 119 (33.0) | <0.000 |

| Data are expressed as mean and standard deviation. DOCE: device-oriented cardiovascular events; MLA: minimum lumen area | ||||

Table 4. Independent variables related to follow-up device-oriented cardiovascular events (DOCE) in the multivariate Cox regression analysis.

| Univariate HR (95% CI) | p-value | Multivariate HR (95%CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malapposition ≥200 μm (%) | 0.87 (0.62-1.21) | 0.407 | 0.92 (0.63-1.39) | 0.661 |

| Stent asymmetry at MLA site | 1.30 (0.703-2.413) | 0.401 | 0.50 (0.22-1.32) | 0.128 |

| Distal edge dissection >200 μm (%) | 1.80 (1.03-3.14) | 0.038 | 1.51 (0.85-2.83) | 0.162 |

| Proximal edge dissection >200 μm (%) | 1.62 (0.99-2.67) | 0.057 | 2.06 (1.18-3.64) | 0.011 |

| Distal reference narrowing <4.5 mm2 | 3.07 (1.86-5.06) | 0.000 | 2.70 (1.66-5.13) | <0.001 |

| Proximal reference narrowing <4.5 mm2 | 3.23 (1.64-6.37) | 0.001 | 2.09 (0.96-4.67) | 0.064 |

| In-stent lumen expansion <70% (%) | 1.43 (0.99-2.07) | 0.056 | 1.59 (1.05-2.56) | 0.038 |

| In-stent MLA ≤4.5 mm² (%) | 2.12 (1.50-2.99) | <0.001 | 1.75 (1.03-2.44) | 0.008 |

| Plaque∕thrombus protrusion ≥500 µm (%) | 1.12 (0.79-1.59) | 0.526 | 0.99 (0.62-1.41) | 0.978 |

| MLA: minimum lumen area | ||||

Acknowledgments

Funding

Supported by a grant from the Centro per la Lotta contro l’Infarto - Fondazione Onlus, Rome, Italy.

Conflict of interest statement

F. Burzotta received speaker's fees from Terumo, Abiomed, Abbott, and Medtronic. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Abbreviations

- CLI-OPCI

Centro per la Lotta contro l’Infarto–Optimisation of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

- DES

drug-eluting stent

- DOCE

device-oriented cardiac events

- MACE

major adverse cardiac events

- MI

myocardial infarction

- MLA

minimum lumen area

- MLD

minimum lumen diameter

- OCT

optical coherence tomography

- PCI

percutaneous coronary intervention

Contributor Information

Francesco Prati, Cardiovascular Sciences Department, San Giovanni Addolorata Hospital, Rome, Italy; UniCamillus - Saint Camillus International University of Health Sciences, Rome, Italy; Centro per la Lotta Contro L'Infarto - CLI Foundation, Rome, Italy.

Enrico Romagnoli, Centro per la Lotta Contro L'Infarto - CLI Foundation, Rome, Italy; Department of Cardiovascular and Thoracic Sciences, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli, IRCCS, Rome, Italy.

Flavio Giuseppe Biccirè, Cardiovascular Sciences Department, San Giovanni Addolorata Hospital, Rome, Italy; Centro per la Lotta Contro L'Infarto - CLI Foundation, Rome, Italy; Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy.

Francesco Burzotta, Department of Cardiovascular and Thoracic Sciences, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli, IRCCS, Rome, Italy.

Alessio La Manna, Cardio-Thoracic-Vascular Department, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria "Policlinico-Vittorio Emanuele", University of Catania, Catania, Italy.

Simone Budassi, Cardiovascular Sciences Department, San Giovanni Addolorata Hospital, Rome, Italy; Centro per la Lotta Contro L'Infarto - CLI Foundation, Rome, Italy.

Vito Ramazzotti, Cardiovascular Sciences Department, San Giovanni Addolorata Hospital, Rome, Italy.

Mario Albertucci, Cardiovascular Sciences Department, San Giovanni Addolorata Hospital, Rome, Italy; Centro per la Lotta Contro L'Infarto - CLI Foundation, Rome, Italy.

Franco Fabbiocchi, Centro Cardiologico Monzino, IRCCS, Milan, Italy.

Alessandro Sticchi, UniCamillus - Saint Camillus International University of Health Sciences, Rome, Italy; Centro per la Lotta Contro L'Infarto - CLI Foundation, Rome, Italy.

Carlo Trani, Department of Cardiovascular and Thoracic Sciences, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli, IRCCS, Rome, Italy.

Giuseppe Calligaris, Centro Cardiologico Monzino, IRCCS, Milan, Italy.

Massimo Fineschi, Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Senese, Siena, Italy.

Francesco Versaci, Cardiology Department, Santa Maria Goretti Hospital, Latina, Italy.

Corrado Tamburino, Cardio-Thoracic-Vascular Department, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria "Policlinico-Vittorio Emanuele", University of Catania, Catania, Italy.

Yukio Ozaki, Department of Cardiology, Fujita Health University Hospital, Toyoake, Japan.

Fernando Alfonso, Department of Cardiology, Hospital Universitario de La Princesa, Universidad Autónoma Madrid, CIBERCV, Madrid, Spain.

Gary S. Mintz, Cardiovascular Research Foundation, New York, NY, USA.

References

- Jang IK, Bouma BE, Kang DH, Park SJ, Park SW, Seung KB, Choi KB, Shishkov M, Schlendorf K, Pomerantsev E, Houser SL, Aretz HT, Tearney GJ. Visualization of coronary atherosclerotic plaques in patients using optical coherence tomography: comparison with intravascular ultrasound. J AmColl Cardiol. 2002;39:604–9. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01799-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintz GS. Clinical utility of intravascular imaging and physiology in coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:207–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prati F, Di Vito, Biondi-Zoccai G, Occhipinti M, La Manna, Tamburino C, Burzotta F, Trani C, Porto I, Ramazzotti V, Imola F, Manzoli A, Materia L, Cremonesi A, Albertucci M. Angiography alone versus angiography plus optical coherence tomography to guide decision-making during percutaneous coronary intervention: the Centro per la Lotta contro l'Infarto-Optimisation of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (CLI-OPCI) study. EuroIntervention. 2012;8:823–9. doi: 10.4244/EIJV8I7A125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prati F, Romagnoli E, Burzotta F, Limbruno U, Gatto L, La Manna, Versaci F, Marco V, Di Vito, Imola F, Paoletti G, Trani C, Tamburino C, Tavazzi L, Mintz GS. Clinical Impact of OCT Findings During PCI: The CLI-OPCI II Study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:1297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prati F, Romagnoli E, Gatto L, La Manna, Burzotta F, Limbruno U, Versaci F, Fabbiocchi F, Di Giorgio, Marco V, Ramazzotti V, Di Vito, Trani C, Porto I, Boi A, Tavazzi L, Mintz GS. Clinical Impact of Suboptimal Stenting and Residual Intrastent Plaque/Thrombus Protrusion in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndrome: The CLI-OPCI ACS Substudy (Centro per la Lotta Contro L'Infarto-Optimization of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Acute CoronaSyndrome). Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:e003726.. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.115.003726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prati F, Guagliumi G, Mintz GS, Costa M, Regar E, Akasaka T, Barlis P, Tearney GJ, Jang IK, Arbustini E, Bezerra HG, Ozaki Y, Bruining N, Dudek D, Radu M, Erglis A, Motreff P, Alfonso F, Toutouzas K, Gonzalo N, Tamburino C, Adriaenssens T, Pinto F, Serruys PW, Di Mario Expert's OCT Review Document. Expert review document part 2: methodology, terminology and clinical applications of optical coherence tomography for the assessment of interventional procedures. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2513–20. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Räber L, Mintz GS, Koskinas KC, Johnson TW, Holm NR, Onuma Y, Radu MD, Joner M, Yu B, Jia H, Meneveau N, de la, Escaned J, Hill J, Prati F, Colombo A, di Mario, Regar E, Capodanno D, Wijns W, Byrne RA, Guagliumi G ESC Scientific Document Group. Clinical use of intracoronary imaging. Part 1: guidance and optimization of coronary interventions. An expert consensus document of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3281–300. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tearney GJ, Regar E, Akasaka T, Adriaenssens T, Barlis P, Bezerra HG, Bouma B, Bruining N, Cho JM, Chowdhary S, Costa MA, de Silva, Dijkstra J, Di Mario, Dudek D, Falk E, Feldman MD, Fitzgerald P, Garcia-Garcia HM, Gonzalo N, Granada JF, Guagliumi G, Holm NR, Honda Y, Ikeno F, Kawasaki M, Kochman J, Koltowski L, Kubo T, Kume T, Kyono H, Lam CC, Lamouche G, Lee DP, Leon MB, Maehara A, Manfrini O, Mintz GS, Mizuno K, Morel MA, Nadkarni S, Okura H, Otake H, Pietrasik A, Prati F, Räber L, Radu MD, Rieber J, Riga M, Rollins A, Rosenberg M, Sirbu V, Serruys PW, Shimada K, Shinke T, Shite J, Siegel E, Sonoda S, Suter M, Takarada S, Tanaka A, Terashima M, Thim T, Uemura S, Ughi GJ, van Beusekom, van der, van Es, van Soest, Virmani R, Waxman S, Weissman NJ, Weisz G International Working Group for Intravascular Optical Coherence Tomography (IWG-IVOCT) Consensus standards for acquisition, measurement, and reporting of intravascular optical coherence tomography studies: a report from the International Working Group for Intravascular Optical Coherence Tomography Standardization and Validation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:1058–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.09.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DA, Rathod KS, Koganti S, Hamshere S, Astroulakis Z, Lim P, Sirker A, O'Mahony C, Jain AK, Knight CJ, Dalby MC, Malik IS, Mathur A, Rakhit R, Lockie T, Redwood S, MacCarthy PA, Desilva R, Weerackody R, Wragg A, Smith EJ, Bourantas CV. Angiography Alone Versus Angiography Plus Optical Coherence Tomography to Guide Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: Outcomes From the Pan-London PCI Cohort. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:1313–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2018.01.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Simoons ML, Chaitman BR, White HD Writing Group on the Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction, Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD, Jaffe AS, Katus HA, Apple FS, Lindahl B, Morrow DA, Chaitman BA, Clemmensen PM, Johanson P, Hod H, Underwood R, Bax JJ, Bonow RO, Pinto F, Gibbons RJ, Fox KA, Atar D, Newby LK, Galvani M, Hamm CW, Uretsky BF, Steg PG, Wijns W, Bassand JP, Menasché P, Ravkilde J, Ohman EM, Antman EM, Wallentin LC, Armstrong PW, Simoons ML, Januzzi JL, Nieminen MS, Gheorghiade M, Filippatos G, Luepker RV, Fortmann SP, Rosamond WD, Levy D, Wood D, Smith SC, Hu D, Lopez-Sendon JL, Robertson RM, Weaver D, Tendera M, Bove AA, Parkhomenko AN, Vasilieva EJ, Mendis S; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG) Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2551–67. [Google Scholar]

- Cutlip DE, Windecker S, Mehran R, Boam A, Cohen DJ, van Es, Steg PG, Morel MA, Mauri L, Vranckx P, McFadden E, Lansky A, Hamon M, Krucoff MW, Serruys PW Academic Research Consortium. Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: a case for standardized definitions. Circulation. 2007;115:2344–51. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.685313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prati F, Romagnoli E, La Manna, Burzotta F, Gatto L, Marco V, Fineschi M, Fabbiocchi F, Versaci F, Trani C, Tamburino C, Alfonso F, Mintz GS. Long-term consequences of optical coherence tomography findings during percutaneous coronary intervention: the Centro Per La Lotta Contro L'infarto - Optimization Of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (CLI-OPCI) LATE study. EuroIntervention. 2018;14:e443–51. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-17-01111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonoda S, Morino Y, Ako J, Terashima M, Hassan AH, Bonneau HN, Leon MB, Moses JW, Yock PG, Honda Y, Kuntz RE, Fitzgerald PJ SIRIUS Investigators. Impact of final stent dimensions on long-term results following sirolimus-eluting stent implantation: serial intravascular ultrasound analysis from the sirius trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1959–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doi H, Maehara A, Mintz GS, Yu A, Wang H, Mandinov L, Popma JJ, Ellis SG, Grube E, Dawkins KD, Weissman NJ, Turco MA, Ormiston JA, Stone GW. Impact of post-intervention minimal stent area on 9-month follow-up patency of paclitaxel-eluting stents: an integrated intravascular ultrasound analysis from the TAXUS IV, V, and VI and TAXUS ATLAS Workhorse, Long Lesion, and Direct Stent Trials. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:1269–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong MK, Mintz GS, Lee CW, Park DW, Choi BR, Park KH, Kim YH, Cheong SS, Song JK, Kim JJ, Park SW, Park SJ. Intravascular ultrasound predictors of angiographic restenosis after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1305–10. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song HG, Kang SJ, Ahn JM, Kim WJ, Lee JY, Park DW, Lee SW, Kim YH, Lee CW, Park SW, Park SJ. Intravascular ultrasound assessment of optimal stent area to prevent in-stent restenosis after zotarolimus-, everolimus-, and sirolimus-eluting stent implantation. Catheter CardiovascInterv. 2014;83:873–8. doi: 10.1002/ccd.24560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Hong SJ, Kim BK, Shin DH, Ahn CM, Kim JS, Ko YG, Choi D, Hong MK, Jang Y. Outcomes of stent optimisation in intravascular ultrasound-guided interventions for long lesions or chronic total occlusions. EuroIntervention. 2020;16:e480–8. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-19-00762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meneveau N, Souteyrand G, Motreff P, Caussin C, Amabile N, Ohlmann P, Morel O, Lefrançois Y, Descotes-Genon V, Silvain J, Braik N, Chopard R, Chatot M, Ecarnot F, Tauzin H, Van Belle, Belle L, Schiele F. Optical Coherence Tomography to Optimize Results of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Patients with Non-ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome: Results of the Multicenter, Randomized DOCTORS Study (Does Optical Coherence Tomography Optimize Results of Stenting). Circulation. 2016;134:906–17. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soeda T, Uemura S, Park SJ, Jang Y, Lee S, Cho JM, Kim SJ, Vergallo R, Minami Y, Ong DS, Gao L, Lee H, Zhang S, Yu B, Saito Y, Jang IK. Incidence and Clinical Significance of Poststent Optical Coherence Tomography Findings; One-Year Follow-Up Study From a Multicenter Registry. Circulation. 2015;132:1020–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.014704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziada KM, Kapadia SR, Belli G, Houghtaling PL, De Franco, Ellis SG, Whitlow PL, Franco I, Nissen SE, Tuzcu EM. Prognostic value of absolute versus relative measures of the procedural result after successful coronary stenting: importance of vessel size in predicting long-term freedom from target vessel revascularization. Am Heart J. 2001;141:823–31. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.114199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maehara A, Ben-Yehuda O, Ali Z, Wijns W, Bezerra HG, Shite J, Généreux P, Nichols M, Jenkins P, Witzenbichler B, Mintz GS, Stone GW. Comparison of Stent Expansion Guided by Optical Coherence Tomography Versus Intravascular Ultrasound: The ILUMIEN II Study (Observational Study of Optical Coherence Tomography [OCT] in Patients Undergoing Fractional Flow Reserve [FFR] and Percutaneous Coronary Intervention). JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:1704–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2015.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali Z, Landmesser U, Karimi Galougahi, Maehara A, Matsumura M, Shlofmitz RA, Guagliumi G, Price MJ, Hill JM, Akasaka T, Prati F, Bezerra HG, Wijns W, Mintz GS, Ben-Yehuda O, McGreevy RJ, Zhang Z, Rapoza RR, West NEJ, Stone GW. Optical coherence tomography-guided coronary stent implantation compared to angiography: a multicentre randomised trial in PCI - design and rationale of ILUMIEN IV: OPTIMAL PCI. EuroIntervention. 2021;16:1092–9. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-20-00501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali ZA, Maehara A, Généreux P, Shlofmitz RA, Fabbiocchi F, Nazif TM, Guagliumi G, Meraj PM, Alfonso F, Samady H, Akasaka T, Carlson EB, Leesar MA, Matsumura M, Ozan MO, Mintz GS, Ben-Yehuda O, Stone GW ILUMIEN III: OPTIMIZE PCI Investigators. Optical coherence tomography compared with intravascular ultrasound and with angiography to guide coronary stent implantation (ILUMIEN III: OPTIMIZE PCI): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388:2618–28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31922-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Mintz GS, Witzenbichler B, Souza CF, Metzger DC, Rinaldi MJ, Duffy PL, Weisz G, Stuckey TD, Brodie BR, Matsumura M, Yamamoto MH, Parvataneni R, Kirtane AJ, Stone GW, Maehara A. Predictors and Long-Term Clinical Impact of Acute Stent Malapposition: An Assessment of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy With Drug-Eluting Stents (ADAPT-DES) Intravascular Ultrasound Substudy. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e004438. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.004438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maehara A, Matsumura M, Ali ZA, Mintz GS, Stone GW. IVUS-Guided Versus OCT-Guided Coronary Stent Implantation: A Critical Appraisal. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10:1487–503. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

List of 498 stents used in the present study.

ROC analysis of in-stent lumen expansion and DOCE with different cut-offs.

Cluster analysis showing the role of suboptimal stent positioning in predicting DOCE and single endpoints in different subgroups.