Abstract

Alcohol is legalized and used for a variety of reasons, including socially or as self-medication for trauma in the absence of accessible and safe supports. Trauma-informed approaches can help address the root causes of alcohol use, as well as the stigma around women’s alcohol use during pregnancy. However, it is unclear how these approaches are used in contexts where pregnant and/or parenting women access care. Our objective was to synthesize existing literature and identify promising trauma-informed approaches to working with pregnant and/or parenting women who use alcohol. A multidisciplinary team of scholars with complementary expertise worked collaboratively to conduct a rigorous scoping review. All screening, extraction, and analysis was independently conducted by at least two authors before any differences were discussed and resolved through team consensus. The Joanna Briggs Institute method was used to map existing evidence from peer-reviewed articles found in PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Social Work Abstracts, and Web of Science. Data were extracted to describe study demographics, articulate trauma-informed principles in practice, and gather practice recommendations. Thirty-six studies, mostly from the United States and Canada, were included for analysis. Studies reported on findings of trauma-informed practice in different models of care, including live-in treatment centers, case coordination/management, integrated and wraparound supports, and outreach—for pregnant women, mothers, or both. We report on how the following four principles of trauma-informed practices were applied and articulated in the included studies: (1) trauma awareness; (2) safety and trustworthiness; (3) choice, collaboration, and connection; and (4) strengths-based approach and skill building. This review advances and highlights the importance of understanding trauma and applying trauma-informed practice and principles to better support women who use alcohol to reduce the risk of alcohol-exposed pregnancies. Relationships and trust are central to trauma-informed care. Moreover, when applying trauma-informed practices with pregnant and parenting women who use alcohol, we must consider the unique stigma attached to alcohol use.

Keywords: alcohol, cultural safety, maternal health, parenting, pregnancy, relational approaches, stigma, substance use, support, trauma-informed

Introduction

To understand the relevance of trauma-informed approaches with women who use(d) alcohol during pregnancy, it is important to situate the role of alcohol in girls’/women’s lives when they are pregnant. Alcohol is an increasingly common substance used by pregnant girls and women in many countries.1 For example, in Canada, 70%–80% of women of childbearing age drink alcohol and approximately 22%–25% report heavy drinking (defined as four or more drinks on one occasion).2 The reasons why women drink alcohol while pregnant are highly varied and complex. Reasons range from not knowing they are pregnant and enjoying alcohol as a social norm and lubricant, to coping with compounding realities of trauma, systemic inequities, discrimination, mental health challenges, and violence.1,3–6

Alcohol use during pregnancy is intertwined with social and structural determinants of health, including early childhood experiences of trauma and violence, patriarchy and toxic masculinity, mental health challenges, racism and discrimination, contemporary and historical forms of colonization, as well as the lack of access to supports and services for mental health and/or trauma.7–11 In addition to early childhood experiences of trauma, people experiencing social and health inequities frequently live with elevated health burdens, including preventable injuries and chronic diseases that contribute to an increased likelihood of mental health and substance use challenges.12–14 Moreover, women globally are disproportionately affected by intimate partner and domestic violence, fewer opportunities for employment with liveable wages, inequitable parenting and other caregiving responsibilities, and other forms of gender discrimination.15–17 As a legal and accessible substance, alcohol is commonly used for self-medication and as a coping method.18

While public and private messages aimed at women consuming alcohol greatly vary by cultural norms, places that endorse and market alcohol to all legal drinking ages, regardless of gender or childbearing years, also shame women who drink alcohol while pregnant for the potential harm it may have on a fetus. If a woman has a child with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD), a lifelong developmental disability resulting from prenatal alcohol exposure, she often experiences many forms of judgment, assumptions, guilt, fear, and shame.19,20 These judgments, assumptions, guilt, and shame associated with having to disclose or explain prenatal alcohol use usually surface out of concern for children with FASD, and not the mothers themselves—sometimes resulting in having children removed from their mother’s care and placed in foster care, with no clear mandate to support the mother.21–24 Stigma, blame, and shame attached to consuming alcohol during pregnancy for women is a real and significant barrier to accessing support, information, resources, and care for themselves, their child(ren), and their families.25,26

Experiences of trauma and trauma-informed approaches

Some women may drink alcohol to cope with trauma and life challenges.27 Trauma results from experiences that overwhelm an individual’s coping capacity and can interfere with an individual’s sense of security, safety, and self-efficacy.28 In an earlier study of 80 women in Washington State who had given birth to children with FASD, 95% of the women had been abused as a child or adult, 80% had a major mental illness, which included 77% being diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, and 72% were unable to reduce their alcohol consumption because of their experiences in abusive relationships.29 The interconnections between trauma, substance use, discrimination and racism, violence, as well as social, health, and material inequities are inherent and well documented.30–32

Trauma-informed approaches take into account the long-lasting emotional responses from distressing events, both the past and present in all aspects of service delivery. Trauma-informed approaches also respond to the judgmental and accusatory narrative around alcohol use in pregnancy. Furthermore, trauma-informed approaches involve acknowledgment that women may not attend services not because of a lack of interest or desire, but because of specific past experiences of trauma, thus allowing providers to adapt service provision to better support women who experience barriers to substance use and related services.

Trauma-informed practices acknowledge a person’s life experiences and impacts of trauma, avoid re-traumatizing them, and support safety, choice, and control so that an effective and sensitive response can be adopted in practice and service delivery.33 Four key principles guide trauma-informed approaches including: (1) trauma awareness; (2) safety and trustworthiness; (3) choice, collaboration, and connection; and (4) strengths-based approach and skill building.34 Being trauma-informed does not necessarily require disclosing or treating trauma; rather, it means working in ways that support healing and acknowledge women’s circumstances without retraumatizing them.34 Because pregnant women can be especially vulnerable to violence and trauma,35 trauma-informed practices are vital in supporting women, particularly when helping women to reduce alcohol use in their current pregnancy or in future pregnancies. How trauma-informed practices are being used and experienced, or how impactful they are, in diverse settings where girls and women who use(d) alcohol during pregnancy are accessing programs, services, or supports is not well documented.

This study

In this scoping review, our objective was to synthesize existing literature and identify a range of promising trauma-informed approaches when working with pregnant and/or parenting women who use(d) alcohol. By mapping and examining promising trauma-informed approaches, programs, and initiatives, we aimed to advance and highlight approaches that better support women who use alcohol to reduce the risk of alcohol-exposed pregnancies.

Throughout this article, we use the term substance use instead of terms such as “problematic substance use” and “substance abuse” because not all substance use should be seen as problematic, and “abuse” is a word reserved for harm inflicted on people. In cases where authors reported on women diagnosed with substance use disorder, we did not change the terminology. We deliberately use the term live-in to describe any programs or services that include living accommodations instead of “residential” because of its association with residential schools, educational institutions that many Indigenous children were forced to attend across Canada, the United States, Australia, and Aotearoa (New Zealand), in efforts to colonize Indigenous People. We use the term women to include people of any gender who were pregnant or had given birth, recognizing that authors of analyzed studies used did not define or qualify how they used or understood sex and gender in their research when reporting on girls, females, and women.

Methods

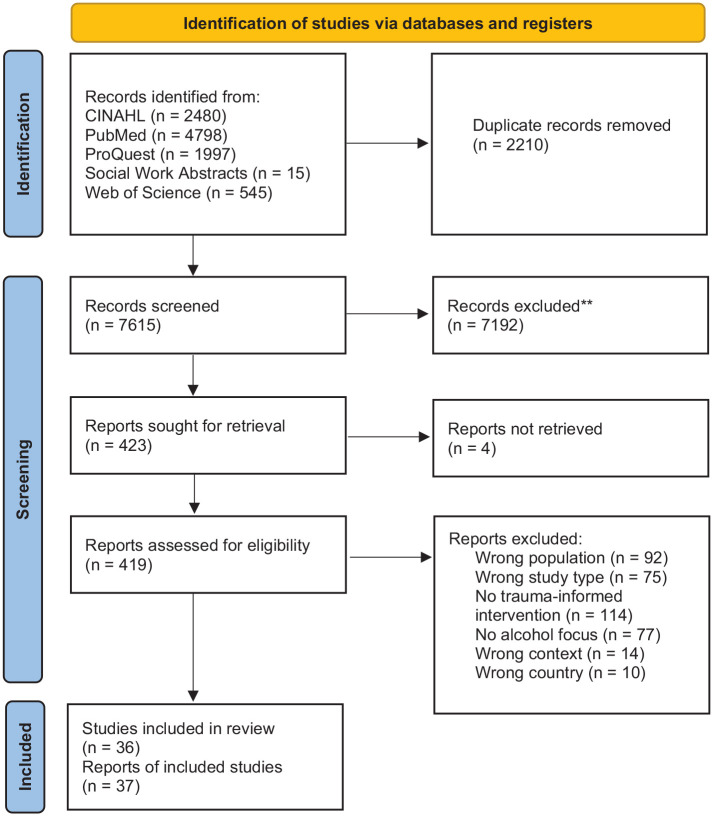

Scoping reviews are useful in providing a broad overview of a topic by mapping and examining emerging evidence.36 They are effective in clarifying key concepts, examining critical gaps in knowledge, and reporting on types of evidence that address and inform practice. We used the Joanna Briggs Institute’s (JBI) Review Methodology which consisted of five key steps: (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying relevant peer-reviewed studies; (3) study selection; (4) charting the data; and (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results. We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist.37 See Figure 1 for the PRISMA flow diagram.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of records.

Source: Based on the 2020 PRISMA flow diagram by Page et al.38

Search strategy

An initial concept chart was developed using the JBI Population/Concept/Context (PCC) framework to inform the search strategy.39,40 The concept chart was developed by the second author (YA), discussed with three members of the research team (MEMN, LW, and KDH), reviewed by other co-authors and a research librarian (DC). YA identified nine relevant peer-reviewed articles that were essential to the review and DC conducted an analysis of keywords in the titles, abstracts, and the index terms of the relevant articles and refined the concept chart into a search strategy. These relevant articles were retrieved through researching databases for studies that explicitly utilized trauma-informed approaches related to pregnant and/or pregnant women who use(d) alcohol. The subject headings and keywords used are outlined in Supplementary File 1. The keywords included, but were not limited to, pregnancy, substance use, prenatal care, parenting, social determinants of health, stigma, harm reduction, and social support. This strategy was translated into CINAHL (EBSCO), PychINFO, Social Work Abstracts, and Web of Science. The final search of peer-reviewed published literature was run by YA on 19 January 2022 to include results dating back to 2005 when the Canadian guidelines for FASD were first published. When the guidelines were released, there was increased attention to potential harms associated with drinking alcohol during pregnancy and we were interested in analyzing relevant research conducted since that time.36

Identifying relevant studies

All citations were imported into Covidence, a data screening and extraction software system for reviews.37 After duplicate articles were removed by the software, the research team members met to discuss inclusion and exclusion criteria to maximize inter-rater reliability. Two reviewers independently screened each title/abstract and full text. Any conflicts at the title/abstract screening stage were reviewed through discussion between LW and YA. Before starting the full-text screening, all reviewers (except DC) pilot screened a sample of five articles outside of Covidence to test for consistency between team members and discussed conflicts until consensus was reached. For full-text screening, conflicts were discussed by the reviewers in conflict or by a small team of three reviewers [YA, MEMN, LW].

Inclusion criteria were: primary studies published in English between 2005 to 19 January 2022; within Canada, Australia, Aotearoa, United States, South Africa, or the United Kingdom; reported on interventions with pregnant and/or parenting women who use(d) alcohol (alone or with other substances) or whose children have FASD; reported on approaches, programs, tools, supports, or models linked to pregnant or parenting girls/women; and contained evidence of trauma-informed practices. We determined which countries would have the most studies related to women, pregnancy, and alcohol use based on our familiarity with FASD prevention-related bodies of literature. We excluded: discussion, commentary, literature review, or prevalence articles and case reports; interventions that targeted substances that did not focus primarily on alcohol; preconception approaches and programs; articles that had no women-specific population interests, focus, or outcomes; articles focused on foster/adoptive families or parents generally; and articles that focused on health-care providers’ perspectives or perceptions of an intervention. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were determined based on the research team’s previous experience and publications on FASD and women who use(d) substances.18,25,41–43

Data extraction

Data extraction was conducted by five team members [YA, NB, LW, KDW, MEMN] within Covidence. Extraction fields were discussed and finalized through team discussions to map and examine available evidence that would help us identify promising trauma-informed approaches and practices with pregnant and parenting women who use(d) alcohol during pregnancy. We extracted information about the study demographics, the approach or interventions, the results, recommendations, and how trauma-informed practices were applied (see Table 1). After two reviewers independently extracted from each article, MEMN reviewed all extracted information by both reviewers to create a “consensus” response to each extracted field. The consensus extraction fields were exported out of Covidence and into Microsoft Excel for analysis.

Table 1.

List of extraction headings and questions.

| Category | Extracted information |

|---|---|

| Study demographics | • Study location (country) • Study objective(s) • Research question(s) • Study population • Study methodology • Number of participants |

| Approach/Intervention | • Focus on pregnant, postnatal/parenting, or both • Setting of approach/intervention • Focus on specific intervention/tool, program/service, or other • Brief description of support, intervention, program • Terms authors used to describe their approach/intervention |

| Results | • Outcomes reported regarding facilitators to care • Outcomes reported regarding barriers to care • Trauma-informed principles reported39 • Other important results |

| Recommendations | • For practice • For further research |

Data analysis

Exported data were “cleaned” to have consistent categories and terminology to describe locations (e.g. “Breaking the Cycle treatment program” to “multi-service maternal substance use treatment program in Toronto”), populations studied (e.g. “women accessing Sheway services” to “pregnant and parenting women with substance use, and their children, accessing an interdisciplinary wraparound program”), and study settings (e.g. “residential substance abuse treatment program participants were interviewed about their time in the facility where they stayed for a period of time” to “live-in substance use treatment program where the majority of women were Indigenous, between age 16–31, from rural and/or reservation communities and where people are court mandated to attend the program”). For qualitative descriptions of program or initiative approaches, reported trauma-informed practices, terms used to describe trauma-informed approaches and practices, barriers, outcomes, as well as practice and research recommendations, we thematically open-coded and organized the data. MEMN and YA independently conducted an initial analysis before discussing and reaching consensus on themes. After consensus was reached, MEMN and YA re-analyzed the data before sharing and discussing preliminary themes with other team members. The team discussion on the findings resulted in re-analyzing the trauma-informed practices data using a deductive approach with four trauma-informed principles articulated in the Trauma-Informed Practice Guide, which is widely recognized in Canada: (1) trauma awareness; (2) emphasis on safety and trustworthiness; (3) opportunity for choice, collaboration, and connection; and (4) strengths-based approach and skill building.34 We chose to organize the findings by principles so that readers could see how trauma-informed practices were operationalized across diverse practice modalities.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

The database searches yielded 7615 unique references after duplicates were removed. After screening all titles and abstracts, 423 articles were retrieved and a total of 37 articles were included for analysis as shown in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1). Two articles reported on the same study so they were analyzed together and represented in Table 2 in the same row,44,45 resulting in 36 included studies.

Table 2.

Summary of analyzed studies.

| Author Country |

Study aims | Study methodology | Study population and setting | Approach description | Reported trauma-informed practices | Key outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andrews et al.67

Canada |

To (1) describe women’s use of service, (2) examine how early engagement of pregnant women related to postnatal service use, and (3) examine the circumstances in which women ended their service relationship with an early intervention and prevention program for pregnant/parenting women and their young children. | Quantitative | Population (n = 160): pregnant/parenting women using substances clients and their families Setting: single access setting in downtown Toronto; early prevention and intervention program for pregnant/parenting women using substances, and their young children aged 0–6 years |

• Comprehensive, integrated, cross-sectoral program • Offered integrated substance use counseling, health/medical services, parenting support, development screening and assessment, early childhood interventions, childcare, access to FASD Diagnostic Clinic, and basic needs support • Home visitation and street outreach components • Formal partnership with services relating to child protection, substance use treatment, health, corrections and probation, and child mental health and development |

Trauma awareness: staff understood complex trauma and worked to overcome barriers to service; staff supported families in accessing and maintaining service involvement Safety and trustworthiness: safe and healthy relationships among staff, between staff and management, and among community agencies were supported; core philosophy revolved around promotion and modeling of safe and healthy relationships for women, their children and the mother–child dyad; staff goals were to engage women, demonstrate safety, be kind, empathetic, caring, compassionate, reliable and consistent |

• Women were actively engaged in many services for long duration • Early engagement with women was associated with greater service use; greater service use was associated with better outcomes by the end of the program • Integrating positive relationships at all levels was critical to supporting families with complex needs • Staff fostered healthy relationships between women and their children using therapeutic modalities and supportive interactions |

| Barlow et al.48

United States |

To (1) evaluate a home visiting program effects on parental competence and maternal behavioral problems that impede effective parenting through early childhood (0–36 months postpartum) and (2) intervention effects on early childhood emotional and behavioral outcomes | Randomized controlled trial | Population (n = 322): pregnant youth ages 12–19 who were at no more than 32-weeks’ gestation from four southwestern American Indian reservation communities Setting: home visiting program |

• Home visiting program • Involved 43 structured lessons focused on reducing behaviors associated with early childhood behavior problems, including externalizing, internalizing, and dysregulation problems • Lessons also addressed maternal behavior and mental health challenges that impede positive parenting, including substance use and externalizing and internalizing behaviors |

Safety and trustworthiness: program was delivered at home Choice, connection, and collaboration: provided transportation to recommended prenatal and well-baby clinic visits, pamphlets about childcare and community resources, and referrals to local services; addressed access barriers to health care for young mothers and children Strengths-based approach and skill building: focused on skills to reduce behaviors associated with early childhood behavior problems; taught skills to address mental health challenges |

• Having a paraprofessional that was Indigenous doing the home visiting was shown to have improved access as compared with the standard “mainstream” home visitation program |

| Chou et al.52

United States |

To explore the construct of mothering children during family-centered substance use treatment | Qualitative | Population (n = 10): mothers with enrolled in live-in substance use treatment, have children under 12 years of age living with them, and have completed a 21-day live-in treatment with children in care Setting: live-in family centered treatment facility |

• Voluntary substance use treatment center • Family-centered, with a behavioral healthcare provider for women, their children, and their families • Evidence-based individual and family-based treatment options for substance use, co-occurring disorders, and trauma for both women and children |

Trauma awareness: the center offered evidence-based treatment for trauma Safety and trustworthiness: sense of community developed; families could share challenges and successes in safe spaces; staff provided empathy and support Choice, connection, and collaboration: connection with staff and other mothers provided a sense of belonging and support; clinical and support staff, such as parenting educators, family therapists, child therapists, and child case managers were available on site Strengths-based approach and skill building: mothers were able to engage in planned/structured activities with their children; different parenting techniques were taught |

• Women gained an understanding of their substance use in the context of their roles as mothers • Having family part of treatment was key to completing the treatment • Children benefited from therapeutic daycare, therapy, and case management services • Connection with staff and other mothers was integral in recovery and provided a sense of belonging and support • Support from other mothers extended beyond treatment as bonds were formed |

| de Guzman et al.53

United States |

To identify and describe which elements of a motivational interviewing intervention were effective in engaging participants and fostering behavior change and expand understanding contexts and motivations that may have contributed to behavioral changes | Qualitative | Population (n = 25): mothers who use alcohol, parenting adolescent children, and had not injected substances in past 3 months. Setting: unclear |

• Fourteen individualized video-based motivational sessions • Sessions 1–7 were designed to assist mothers in reducing or eliminating drinking/substance use and associated harms • Sessions 8–14 focus on parenting skills and built on skills learned in the first component • Primary focus was assisting mothers in engaging members of their social network to support their substance use and parenting goals |

Trauma awareness: recognized the complexities of women’s lives and their lived experience Safety and trustworthiness: relational approach; harm reduction approach Choice, connection, and collaboration: supported women to focus on goals beyond those that solely addressed substance use; focused on the connection between facilitators, children, and support networks Strengths-based approach and skill building: dedicated time to build healthy coping mechanisms and parenting skills |

• Relationships between women and facilitators were key to engagement and making changes • Harm reduction approach allowed women to develop realistic plans and responses to substance use • increased skills and parenting strategies developed |

| Espinet et al.76

Canada |

To (1) explore whether a relationship-focused intervention produces greater improvements in maternal substance use, relationship capacity, and mental health than standard integrated treatment and (2) explore mechanisms of change | Quantitative | Population (n = 91): mothers parenting children under the age of seven, in a treatment program, compared to mothers receiving standard integrated treatment Setting: multi-service maternal substance use treatment program in Toronto |

• Relationship-focused intervention • Integrated program that offered substance use- and parenting-related services • Built on the understanding that maternal substance use is often a problem arising from relationships since childhood that have been largely traumatic • Services were offered to the mother–child dyad so that the mother–child relationship is always considered |

Trauma awareness: acknowledged past trauma and the role of relationships (past & present) in active substance use and recovery Safety and trustworthiness: extensive > 1 month intake process (with clinical assessments, case formulation, and counseling) was designed to build rapport, gain trust, and establish a secure therapeutic connection; promoted a positive mother–child relationship in treatment for women who use substances Choice, connection, and collaboration: mothers accessed (through self-agency or other referral) and engaged in the interventions on a voluntary basis; abstinence was encouraged as a choice as well as reduction in drinking |

• Improved maternal confidence in using less/no substances • Reduced symptoms of depression and anxiety after 1 year of intervention • Improved relationships through enhancing maternal perceptions of support from family • Increased feelings of social support and attachment security after 1 year of intervention |

| Frazer et al.54

United States |

To identify common motivators for seeking treatment and barriers to treatment for pregnant/parenting women with substance use disorders to reduce barriers, optimize motivations, and improve access to care | Qualitative | Population (n = 20): pregnant women ages 18 or older, in treatment at Center for substance use and pregnancy for at least 4 weeks at the time of interview, without a gap in treatment for more than 1 week in the 4 weeks preceding interview Setting: intensive outpatient treatment facility at Johns Hopkins. |

• Services available in one location • Services for pregnant women with substance use disorders seeking comprehensive care • individual and group therapy • Pharmacological care • Pediatric and case management, which included housing, legal, and financial support • Option for intensive outpatient treatment • Option for shelter beds for women experiencing homelessness, violence, or otherwise unstable living conditions. |

Trauma awareness: approach was described as “trauma-informed” Safety and trustworthiness: non-judgmental care Strengths-based approach and skill building: defined as an educational program |

• Motivators for seeking treatment included: • Seeking daily structure concern for health of baby • Homelessness • Desire to maintain/gain custody of child(ren) • Feeling ready to stop using • Motivation from a partner • Inability of other treatment facilities to treat pregnant women |

| Gartner et al.79

Canada |

To empower and amplify voices of women with a history of perinatal substance use so improved services are client- and patient-directed and meet the women’s needs | Qualitative | Population (n = 21): pregnant/parenting women, largely urban Indigenous women with substance use, and their children, accessing an interdisciplinary wraparound program Setting: interdisciplinary, “one-stop shop” program for women with substance use in pregnancy and their children, in Vancouver |

• Health-care services accessed by pregnant women with a substance use history • Services available in one location • Women-centered model with an interdisciplinary team including social work, counseling, substance use workers, nursing, early childhood development, medicine, legal support, Indigenous cultural support, and housing advocacy • Provides daily meals in a drop-in, child-friendly space |

Trauma awareness: acknowledged that women accessing Sheway frequently reported traumatic experiences. Safety and trustworthiness: positive, welcoming, genuine, and non-judgmental place where women felt safe Choice, connection, and collaboration: relationships were developed between clients and staff; services were delivered collaboratively between staff and women |

• Loving bonds were developed and women described gaining stability in their lives • Meeting other women in the program gave women a vision of where they could be |

| Gruß et al.55

United States |

To identify patient perspectives about the role of a pilot program for pregnant and postpartum women with substance use disorders, and specifically examine how peer support groups played a role in their recovery | Qualitative | Population (n = 12): pregnant/parenting women who participated in an integrated care initiative for pregnant and postpartum women with substance use disorders Setting: medical care centers that are part of an integrated health-care system providing health insurance coverage to approximately 610,000 patients with commercial and public insurance plans throughout the state of Oregon. |

• Integrated care program initiative • Weekly peer support groups; peer mentors with lived experience to support social support as needed outside of the support group • Obstetric care • Created space for participants to share any experiences from their daily lives relevant to their substance use and recovery • Included education such as information about birth control • Obstetricians, gynecologists, or substance use specialists typically referred patients to the program |

Safety and trustworthiness: peer support group component provided a judgment-free space Choice, connection, and collaboration: patients chose to attend treatment as they preferred (regularly or sporadically); collaboration between staff in the program regarding treatment and services (substance use counselor, social worker, ob-gyn, paid peer mentor) Strengths-based approach and skill building: developed skills to process and address stigmatizing encounters |

• Weekly attendance at peer support groups helped women remain accountable for staying engaged and maintaining sobriety • Participation in the support group helped renew commitment to engage in recovery and provided immediate access to medical services for all participants • Establishing a community around motherhood helped with self-acceptance and validation, while enabling mothers to shift perceptions from “addicts” to mothers • Support group provided the opportunity to process stigmatizing experiences |

| Hennelly et al.80

United Kingdom |

To develop, implement, and evaluate the feasibility of a mindfulness-based maternal behavior change intervention for women who are pregnant | Mixed methods | Population (n = 30): pregnant women who expressed interest in participating in a mindfulness program Setting: recruitment through social media, yoga classes, and other pregnancy exercise and interest groups. Women who expressed interest, attended face-to-face sessions at an unknown location |

• Mindfulness-based behavior change intervention for pregnant women • 17-week program that began with an introductory session with information about potential effects of alcohol, smoking, nutrition, and activity on pregnant women and their children’s immediate and lifetime outcomes • Participants received a mindfulness book/CD combo and a diary, set SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-framed) goals • First 8 weeks were in-person sessions and second 8 weeks were self-led sessions |

Choice, connection, and collaboration: voluntary program Strengths-based approach and skill building: taught mindfulness skills and psychoeducation; women were invited to set their autonomous SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-framed) goals |

• Women who were already engaged in self-care were more likely to choose this approach • The few women who did not complete the full 16 weeks had higher mental health symptoms and increased “health behaviour risks” • The message about alcohol was obscured by the focus on mindfulness |

| Hser et al.57

United States |

To examine the long-term outcomes of women who were pregnant/parenting at admission to women-only versus mixed-gender substance use treatment programs | Quantitative | Population (n = 1000): pregnant/parenting women from 8 women-only and 32 mixed-gender substance use programs Setting: 8 women-only and 32 mixed-gender substance use treatment programs across California |

• Women-only programs, as compared with mixed-gender programs, were significantly more likely to offer childcare and child development services, mothering groups, and HIV testing • Women-only programs tended to employ only women in counseling positions |

Trauma-awareness: recognized that women were more likely to have co-existing psychiatric problems, lower self-esteem, and extensive histories of traumatic life events. Strengths-based approach and skill building: women’s only programs were more likely to offer job training and practical skills training |

• None reported |

| Le et al.68

Canada |

The objectives of this study were to: (1) describe the population of women attending integrated programs in Ontario; and (2) evaluate levels and predictors of treatment participation. This study forms part of a larger mixed-methods evaluation of treatment processes and outcomes in Ontario’s integrated programs | Quantitative | Population (n = 5162): pregnant/parenting women with children under 6 years old at the point of admission to one of 36 substance use treatment programs Setting: outpatient integrated treatment programs across Ontario for pregnant/parenting women |

• Integrated substance use treatment programs designed for pregnant/parenting women and their children under 6 years of age • Women-centered, holistic, empowering, and focused on meeting individual needs of women and their children including providing childcare • Counseling for substance use and mental health • Prenatal and primary care services for parenting and child development to address social-economic resources, with a focus on maternal and child health promotion and the development of healthy relationships |

Trauma awareness: described as trauma and violence informed Safety and trustworthiness: women-centered, empowering, holistic, and focused on meeting the needs of women and their children. Strengths-based approach and skill building: programs worked toward helping women reduce their substance use or maintain abstinence; worked to improve maternal and child health, and outcomes relating to parenting and child custody, housing, and social support |

• Counselor played central role for emotion regulation and executive functioning • Multi-sectoral service coordination and therapeutic supports for emotion regulation and executive functioning may be particularly important for pregnant/parenting women who are accessing substance use services |

| Lefebvre et al.69

Canada |

To assess participant perception of an integrated model of care for substance use in pregnancy. The goal of the study was to determine which components of care were the most valuable to the women in intensive case management (ICM) | Qualitative | Population (n = 19): pregnant women who had received substance use and prenatal care at one of two sites of family medicine units Setting: clinics in Toronto and Montreal where women access prenatal care; integrated care can be provided to women with substance use during pregnancy, through coordination and referrals to different clinical and other services |

• Diverse staff included family physicians, obstetricians, nurse practitioners, midwives, nurses, and clerical staff • Integrated care included substance use counseling, methadone prescribing, and antenatal and intrapartum care • Patients also had the option to remain as family medicine patients postpartum if they did not have a physician |

Trauma awareness: staff were trained in compassionate and nonjudgmental care Safety and trustworthiness: women felt comfortable and secure with their providers; the physician/nurse dyad manages patients from intake to postpartum (formed trusting relationships over time) Choice, connection, and collaboration: respected women’s choices and offered support; woman-centered model of care Strengths-based approach and skill building: a variety of services were offered including sensitive childbirth education information |

• Women felt comfortable in an encouraging environment, which increased the likelihood of them returning • Integrated programs helped educate women’s own family physicians • Women felt less rushed at appointments in integrated programs compared to care from other providers |

| Marcellus71

Canada |

To describe pathways that women and their families followed and how transitions were experienced in the early years after receiving services through an integrated community-based maternity program, using grounded theory | Mixed methods | Population (n = 18): women transitioning from pregnancy to parenthood and recovering from substance use, majority of whom were Indigenous Setting: community-based pregnancy outreach and parenting program offering health care and counseling for women and mothers with substance use, in an inner urban neighborhood with high incidences of homelessness, substance use, and HIV |

• Integrated community-based program • Offered practical supports, health care, and counseling to high-risk pregnant women and mothers with substance use |

Trauma awareness: model of practice was woman-centered, trauma-informed, focused on harm reduction, and culturally responsive Choice, connection, and collaboration: women worked through challenges and connected with other women who were parenting; the program facilitated connections for the women with friends, family, and culture Strengths-based approach and skill building: women built routine and stability to support the development of their children; women attended parenting classes |

• Connection with family, friends, resources, and children was increased • Women’s resilience was increased |

| McCarron et al.58

United States |

To identify the social and cultural mechanisms that support the recovery of American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) pregnant/parenting women seeking substance use treatment | Qualitative | Population (n = 18): discharged pregnant or parenting women’s live-in substance use treatment program; primarily Indigenous women living with poverty Setting: live-in substance use treatment program where the majority of women are Indigenous, between age 16 and 31, from rural and/or reservation communities and where people are court mandated to attend the program |

• Live-in substance use treatment program • Women were allowed to have their children live with them throughout treatment • Participants attended individual and group counseling sessions • Women had access to culturally specific materials (e.g. for smudging) |

Trauma awareness: acknowledged the impacts of historical trauma, and the psychological and social responses to traumatic events a community/population experiences over generations among AI/AN women Safety and trustworthiness: the program was culturally competent and culturally safe Choice, connection, and collaboration: staff provided physical support for the women in the program by watching their children, providing transportation and ensuring they were on time for appointments |

• Interacting with people who had similar experiences was helpful in reducing alcohol use • Participating in programs such as AA or Indigenous specific sobriety programs were important for aftercare • Therapy was beneficial in maintaining the sobriety of Indigenous participants • Talking circles and being able to share and discuss experiences with others as a part of successful recovery were helpful • Emotional support was talked about more than any other type of support |

| Milligan et al.70

Canada |

To develop a theoretical model of integrated treatment by examining how qualities and behaviors within the therapeutic relationship support positive outcomes for pregnant/parenting women with substance-related problems | Qualitative | Population (n = 50): mothers from six integrated treatment programs in Ontario; varied ethnicities and sexual identities Setting: six clinics with integrated substance use treatment programs, across Ontario |

• Integrated substance use treatment programs • Resources based on local needs • Varied services including childcare, parenting supports, access to primary care, housing, employment supports, and so on • Service provision for women and their children ages 0–6 • Promoted healthy child/family outcomes, reducing substance-related harms among women, and healthy pregnancy |

Trauma awareness: counselors would initiate contact, call, and text participants recognizing what barriers to care may be and act as a cognitive cue to attendance Safety and trustworthiness: program counselors were caring, warm, accepting, empathetic, and non-judgmental Choice, connection, and collaboration: counselors were flexible, client-driven, and able to respond to client readiness to change; counselors helped women navigate systems and develop action-oriented goals; women felt in control of their recovery and able to make choices best suited to their individual circumstances Strengths-based approach and skill building: counselors taught women regulation skills and coping strategies; counselors provided parent coaching that was adapted to the learning styles of each woman |

• Relationships between the participants and their counselors were foundational for treatment • Non-judgment, empathetic listening, supportive commitment, support for emotional regulation, and treatment flexibility were beneficial therapeutic approaches • Participants felt that they were seen as a whole person and not judged for their substance use alone • Acknowledgment of participants’ success boosted self-esteem and empowered them to continue • Development of a secure attachment, with proximity seeking, safe haven in times of distress, and a secure base had the strongest impact on the quality of the therapeutic relationship |

| Morgenstern et al.59

United States |

To test the effectiveness of usual care versus integrated case management with substance-dependant women accessing temporary assistance for families “in need” | Randomized controlled trial | Population (n = 302): mothers with substance dependency also receiving substance use treatment and involved with welfare services; primarily Black women Setting: separate clinical space at the local welfare office |

• Mothers with substance use dependency were assessed and randomly assigned to either receive intensive case management (ICM) or usual care (UC) • UC consisted of a health assessment and a referral to substance use treatment and welfare services • ICM clients received augmented longer-term care strategies and cross-systems coordination that addresses other health and social needs as well as monitoring for relapse over an extended period of time |

Trauma awareness: case managers provided outreach (including home visitation and outreach to family); case manager contact with clients was adapted on the basis of need and phase of treatment, tailored to the individual Safety and trustworthiness: clients received vouchers for purchasing items as incentives for attending treatment Choice, connection, and collaboration: case managers coordinated services with treatment staff and met with clients weekly |

• ICM clients used care management services twice as long as UC clients across a 15-month period • Significantly more ICM clients initiated treatment within the first 30 days • Rates for program completion were almost twice as high among ICM clients than among UC clients • Likelihood of point prevalence abstinence (percentage of participants abstinent during the 1-month window) during months 1 through 15 were 75% higher among ICM clients than among UC clients |

| Murnan et al.56

United States |

To look into effective interventions for women sex workers seeking substance use treatment | Randomized controlled trial | Population (n = 68): mothers who do sex work and have custody of children ages 8–16, and who accessed a treatment facility Ohio for their substance use disorder Setting: mothers with a substance use disorder and work in the sex trade, who had previously accessed substance use treatment program in Ohio in the past were randomly assigned to a (1) home-based family therapy, (2) office-based family therapy, or (3) Women’s Health Education (WHE) |

• Woman–child dyads were randomly assigned to one of three interventions: (1) home-based family therapy (2) office-based family therapy, or (3) Women’s Health Education (WHE) • A 12-session family therapy that targets specific stressful parent–child interactions that contribute to the development of problem behaviors such as substance use (called ecologically based family therapy (EBFT)) was offered in the home- and office-based therapy • WHE was a 12-session psycho-educational intervention focused on topics such as female anatomy, human sexual behavior, pregnancy and childbirth, and sexually transmitted infections—and does not engage other family members in treatment |

Safety and trustworthiness: therapists were available 24 h a day, seven days a week for crises Choice, connection, and collaboration: the intervention focused on the social interactions among all family members; appointments were scheduled to meet clients’ needs with evening and weekend sessions offered; therapists assisted families in connecting with other needed services such as medical care, job training, governmental assistance, or 12-step programs Strengths-based approach and skill building: therapists facilitated improved communication and problem-solving skills among family members; therapists assisted parents and children in becoming more confident and competent in their ability to communicate needs and address their responsibilities |

• The EBFT home group showed less moderate and severe substance use than the WHE group on average |

| Niccols and Sword72

Canada |

To evaluate a program designed for women who are pregnant/parenting young children by gaining insight into their experiences and perceptions of any changes attributed to program involvement | Qualitative | Population (n = 11): pregnant/parenting women of young children accessing support for their substance use Setting: one-stop program for women with substance use issues who are pregnant/parenting young children, in a large urban center in Ontario |

• Centralized, multi-sector, and one-stop program • Included substance use groups and counseling, nutrition counseling, skills development, parenting education, peer support, and an enriched children’s program • Individualized program provided linkages with prenatal services, a family physician, a perinatal home visiting program, and other services • Program was not set in terms of a specific structure or length of time, only a goal of improving the health and well-being of women and their children |

Safety and trustworthiness: offered services in a safe and welcoming environment and aimed to improve emotional well-being Choice, connection, and collaboration: women were assisted in defining their needs and goals as well as in designing their own programs for change; collaborative and centralized approach to service delivery was provided and decisions were made with individuals in care; access to numerous supports and services Strengths-based approach and skill building: promoted learning through parenting education, counseling, and children’s programming |

• Decreased substance use was attributed to “self-discovery,” learning strategies to reduce use, and hearing other women’s stories • Mental, social and physical health was enhanced • The one-stop service was beneficial • There was an increased opportunity for employment and awareness of other services in the community |

| O’Malley et al.60

United States |

To describe a program model that provides specialized support to families affected by maternal substance use and presents data on family goal attainment | Mixed methods | Population (n = 220 families): pregnant/parenting women of children 6 months of age, and their families who are affected by maternal substance use in urban midwestern United States Setting: home visiting and family support program |

• Home visiting specialists • Offer holistic, multi-disciplinary, community-based model of care addressing the unique needs of families affected by maternal substance use • staff provided services that aimed to enhance parent–child interactions, promote child development |

Trauma awareness: team members received extensive training in the principles of trauma-informed care; past substance use histories and life challenges were acknowledged without judgment; sensitive practices were promoted to avoid retraumatizing clients Safety and trustworthiness: created a sense of safety and mutual trust that empowered the women to fully participate; facilitated strong therapeutic relationships between home visiting professionals and mothers and their families Choice, connection, and collaboration: staff partnered with families to set goals toward family stability; mothers were surrounded with the resources and support they needed to succeed; flexible programming; courses were customized to meet individualized goals of each woman Strengths-based approach and skill building: strengths-based framework; self-care practices were taught and encouraged to strengthen participants’ resilience |

• Families demonstrated notable growth in six goals (maternal substance use, positive parenting practices, positive child health outcomes, positive maternal health outcomes, family income and family housing) • The model demonstrated the importance of meeting mothers where they are in their lives |

| Ordean and Kahan73

Canada |

To evaluate a physician-led program with a one-stop model of care developed to address the barriers that women faced in accessing care | Quantitative | Population (n = 122): pregnant women who received care at a physician-led program with a one-stop model of care in Toronto Setting: comprehensive prenatal care and substance use treatment program in a family medicine clinic |

• Physician-led program with a one-stop model of care • Provided coordinated and individualized care within a primary care setting for pregnant women who use substances • Combined obstetric and substance use care with case management • Woman-centered and harm reduction approach |

Safety and trustworthiness: women developed trusting relationships with healthcare providers Choice, connection, and collaboration: harm reduction approach aimed to decrease the harmful effects of drug and alcohol use by decreasing use; women-centered approach provided choice and control over health care and other services; collaboration among treatment staff; women were connected to numerous services based on individual needs |

• Women were more likely to continue attending when services were offered at one location • By the time of delivery, more women were living in stable housing • Maternal substance use decreased during pregnancy with statistically significant differences noted for women who came to the clinic early in their pregnancies • The longer a woman received care, the more likely she was to retain custody of her child |

| Osterman et al.62

United States |

To determine the effectiveness of motivational interviewing to decrease alcohol use during pregnancy while investigating self-determination theory mechanisms that may have evoked a change in women’s prenatal alcohol use | Randomized controlled trial | Population (n = 184): pregnant women attending an obstetrical clinic at 36 weeks or less gestation, and who are using alcohol during pregnancy Setting: prenatal clinics in a midwestern university medical center |

• A single session of motivational interviewing (30 min) was used with randomly assigned pregnant women 36 weeks or less gestation with reported alcohol use in the past year • The motivational interviews aimed to assist pregnant women to decrease alcohol use by fostering an empathic relationship that promoted self-awareness of discrepancies in beliefs, values, and behaviors and supported autonomous decision-making to engage in healthier behaviors |

Trauma awareness: staff engaged in non-judgmental and respectful communication Safety and trustworthiness: staff were respectful and caring when asking about a woman’s goals for her pregnancy as well as her beliefs and attitudes about prenatal alcohol use; feedback was provided in a non-judgmental way Choice, connection, and collaboration: women were treated as capable of making healthy decisions for themselves Strengths-based approach and skill building: information and direction was provided to assist each woman in development of strategies for behavior change |

• A single-session MI intervention was not effective in decreasing prenatal alcohol use |

| Osterman et al.61

United States |

To evaluate the efficacy of motivational enhancement therapy in decreasing alcohol use in pregnant women attending substance use treatment | Population (n = 41): pregnant women who entered treatment for substance use in North Carolina, New Mexico, Indiana, and Kentucky Setting: substance use treatment programs across four agencies in North Carolina, New Mexico, Indiana, and Kentucky |

• Pregnant women 18+ and accessing substance use disorder treatment were offered motivational enhancement therapy modified for pregnant women who use substances (MET-PS) • Three sessions included (1) the usual assessments and intake procedures, (2) reviewed each individualized feedback on their substance use behaviors and healthy pregnancy activities, and (3) developed a change plan to strengthen the commitment to change • Standard case management and monthly counseling visits were replaced with two weekly counseling sessions |

Choice, connection, and collaboration: client-centered directive approach Strengths-based approach and skill building: women are motivated to change behaviors based on four principles: establishing empathy, developing discrepancy, rolling with resistance, and supporting self-efficacy |

• Motivational enhancement therapy was reported to have a significant effect in decreasing alcohol use | |

| Rasmussen et al.74

Canada |

To determine whether the Indigenous program modeled after a Canadian Parent–Child Assistance Program resulted in improved outcomes among women at-risk for giving birth to a child with FASD | Quantitative | Population (n = 70): mothers who have already delivered at least one exposed alcohol and drug-exposed child and completed the Alberta First Steps intervention program; approximately half were Indigenous Setting: parent–child assistance program offered to mothers who have a alcohol and/or drug-exposed child, to prevent future substance-exposed children, as a community-based public health intervention program |

• Advocacy and case management model • Included trained and supervised case managers (mentors) with a maximum caseload of 15 families • Mentors worked with clients for 3 years beginning during pregnancy or within 6 months after the birth of a substance-exposed child • The program included needs and goal assessments between clients and mentors |

Safety and trustworthiness: case managers developed a positive, empathic relationship with their clients Choice, connection, and collaboration: case managers helped mothers identify personal goals and the explicit steps necessary to achieve them |

• Significant reduction in needs from pre- to post-program: reduction in financial issues, difficulties with community resources, substance use, health issues, social problems, housing, and transportation difficulties • Significant increase in goals from pre- to post-program: positive change in parenting, self-care, and health • Abstinence rates for clients were 44% for drugs and 35% for alcohol at program exit, and 93% of clients had been sober for at least 1 month |

| Rutman and Hubberstey77

Canada |

To share evaluation findings related to cross-sectoral service collaborations and outcomes for service partners, women, and families for a multi-service drop-in and outreach program for women with substance use issues and who also may be affected by mental illness, trauma, and/or violence | Mixed methods | Population (n = 60): pregnant/parenting women affected by substance use and perhaps affected by mental illness, trauma, and/or violence enrolled in a multi-service drop-in and outreach program; program service partners; program staff Setting: multi-service, drop-in, wraparound, and outreach program for pregnant/parenting women with substance use and may be affected by trauma, violence, and mental health challenges. It is a street-accessible, community-based organization. |

• Drop-in and outreach (for street-involved women) program • Relationship-based, women-centered, and trauma-informed, using a harm reduction approach • Case managers • Basic needs support • Child assessments and early interventions, childcare, child healthcare, and child welfare supports • Cultural programming • Drop-in peer connections • Medical care • Housing advocacy and supports • Mental health counseling and groups as well as substance use counseling • Parenting programming • Pre- and postnatal care |

Trauma awareness: specific focus for women who were affected by substance use and mental illness, trauma, and/or violence Safety and trustworthiness: staff developed trusting relationships with clients and supported and advocated for them; promoted safety and mitigating harm rather than cessation of substances; case managers provided support in emotionally charged situations, including when an infant or child was removed Choice, collaboration, connection: case managers advocated for and supported women in child welfare issues; integrated programming Strengths-based approach and skill building: parenting programming |

• Staff were known through the community of service providers, and these connections are crucial in developing trusting working relationships between agencies that benefit the clients • The program helped to prevent clients’ infants from going into government, helping them regain custody of their children, or improving their connection with their children |

| Rutman et al.82

Canada |

To describe the array of wraparound services and supports offered by the eight programs that offer wraparound services for pregnant/parenting women, and how they organized their services to facilitate access to ‘one-stop’ health and social care | Mixed methods | Population (n = 125 pregnant/parenting women; n = 61 program staff; n = 42 service partners): pregnant/parenting women receiving support at one of the eight wraparound programs offering perinatal, primary, and mental health care, as well as substance use care for pregnant/parenting women Setting: eight multi-service programs in parts of Canada, modeling a wraparound approach that removes barriers to services |

• Community-based programs in Canada that blended primary and prenatal care • Wraparound delivery model responding to individual needs • Basic needs and social support • Perinatal, primary, and mental health care • Substance use services • Co-location with other services, shared services and staff, and relationships with service partners provided supports on-site or connected women to an array of services and support |

Trauma awareness: recognized that most women were wary of formalized healthcare and had previous negative experiences with health and social care systems; approaches were described as relational, harm reduction focused, trauma-informed and culturally safe with a social determinants of health focus; on-site trauma/violence-related programming Safety and trustworthiness: social workers with knowledge of provincial child welfare regulations were on site to function as a bridge between the program and child protection service; on-site group-based and/or one-to-one substance use counseling and support; trusting relationships developed with care providers who were sensitive to personal histories; clients expressed that the staff promoted a sense of safety, honesty, trust, and community Choice, connection, and collaboration: focused on addressing women’s housing needs and assisting them to access safe and stable housing; programs offered a range of services to meet client needs; program managers sought connections with complementary services and programming in areas other than health care, substance use, and child welfare services |

• Wraparound services helped ensure women had access to a wide range of needed primary care, as well as prenatal, postnatal, and mental health care • On-site trauma/violence counseling and support was valued • Having an alliance or partnership with child welfare services was important to women • Programs’ developmental lens helps women access key parenting and pediatric services • Cultural programming promoted women’s (re)connection to traditional knowledge and teachings, and to holistic and land-based healing practices |

| Ryan et al.63

United States |

To evaluate the use of recovery coaches in child welfare | Randomized controlled trial | Population (n = 931): mothers with substance use, enrolled in a randomized clinical trial involving a recovery coach or the traditional services; mostly Black women Setting: recovery coaches engaged with families, in their homes and at appointments, for people who were clients of a substance use treatment program and involved with the child welfare system |

• A recovery coach worked with families as independent advocates and supports • Coaches were employees of a social service agency and not of a child welfare or substance use treatment agency (they had about eight cases each) • Recovery coaches were trained in areas of substance use, relapse prevention, DSM IV, American Society of Addiction Medicine, fundamentals of assessment, ethics, service hours, client tracking systems, service planning, case management and counseling |

Safety and trustworthiness: recovery coaches participated in joint home visits with the child welfare caseworkers and/or agency staff; coaches went to other provider agencies with the women Choice, connection, and collaboration: relationships with the woman and her family were prioritized; recovery coaches engaged in advocacy by assisting parents in obtaining benefits and in meeting the responsibilities and mandates associated with benefits |

• The use of recovery coaches in child welfare significantly decreased the risk of substance exposure at birth • Integrated and comprehensive approaches are necessary for addressing the complex and co-occurring needs of families involved with child protection |

| Slesnick and Erdem44,45

United States *Same study |

To pilot-test a comprehensive intervention with homeless women and their 2–6-year-old children in family shelter | Quantitative | Population (n = 15): mothers who lacked a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence; had physical custody of a biological child between the ages of 2–6 years; and met the DSM criteria for Psychoactive Substance Use or Alcohol Disorder Setting: case management and substance use counseling was provided to mothers with young children in their care at a family shelter or community housing program |

• Intervention supported women to rent an apartment that was not contingent on substance abstinence or treatment attendance • Provided case management and substance use counseling for 6 months • Case management component focused on assisting mothers to meet their basic needs, obtain government entitlements, and obtain employment • Counseling therapists advocated for mothers and connected them to social services through providing referrals and/or transporting women to appointments such as job interviews |

Trauma awareness: case management helped address the basic needs of mothers including issues with housing, safety, food, healthcare, employment, and childcare Safety and trustworthiness: mothers received utility and rental assistance and furniture and appliances Choice, connection, and collaboration: mothers were provided with a list of apartments in the first meeting and noted that independent housing was not contingent on substance use treatment Strengths-based approach and skill building: case management involved assessing mothers needs and building off of it; substance use intervention included a functional analysis of using and non-using behaviors, skills training, and relapse prevention as well as social skills training including communication and problem-solving skills, social and recreational counseling, anger/stress management and support with parenting; treatment aimed to increase alternative reinforcing activities in the client’s life which competed with substance abuse and other maladaptive behavior |

• Mental health symptoms, substance use and children’s internalizing and externalizing problems improved • Housing stability was associated with reduced substance use at 6 and 9 months • Mothers showed improvements in “problem consequences” that were related to substance use |

| Slesnick and Zhang64

United States |

To examine the impact of family systems therapy, compared to a non-family therapy, among women seeking substance use treatment through a large community treatment program | Quantitative | Population (n = 183): mothers with a substance use disorder at a community treatment center with at least one biological child in their care Setting: community substance use treatment center that offers outpatient treatment. Families were assigned to (1) a home-based EBFT, (2) office-based ecologically based family therapy, or (3) WHE |

• 12-session family systems therapy that targets specific dysfunctional interactions linked to the development of problem behaviors • EBFT is a family systems therapy. which recognizes that substance use and related individual and family problems are nested in multiple interrelated systems, and therefore, targets dysfunctional family interactions associated with the development and continuation of problem behaviors • Treatment sessions focused on guiding families to consider their current problems and solutions through techniques such as reframing and interpretations, interrupting problem behaviors through communication and problem-solving skills training, and assisting families in obtaining services such as medical care, job trainings, or self-help programs |

Choice, connection, and collaboration: EBFT focused on improving social interactions, emotional connectedness, and problem resolution skills among family members; focused on autonomy and readiness; assisted families in obtaining services such as medical care, job trainings, or self-help programs Strengths-based approach and skill building: guided families to consider their problems and solutions through techniques such as reframing and interpretations; taught interrupting problem behaviors through communication and problem-solving skills training |

• Women receiving family systems therapy reported a faster decline of alcohol, marijuana, and cocaine use compared to women in the individual therapy comparison condition • Mothers and children showed improved autonomy-relatedness over time |

| Sperlich et al.65

United States |

To design and evaluate client-centered educational support groups for young mothers and mothers-to-be who experienced traumatic stress and were attending intensive live-in rehabilitation inpatient programs for women with substance use disorders | Mixed methods | Population (n = 48): pregnant or parenting women with a substance use disorder, living in a live-in treatment center Setting: two intensive live-in rehabilitation programs for women with substance use disorders |

• A parenting education support (TIPS) group curriculum for expectant mothers and/or mothers of young children in substance use recovery treatment • The curriculum included eight modules on safety; trauma symptoms; overcoming stigma, guilt and shame; parenting skills; attachment; and child development |

Trauma awareness: curriculum was developed with an emphasis on applying trauma-informed principles of safety, trustworthiness, choice, collaboration, and empowerment Safety and trustworthiness: curriculum covered safety and trauma symptoms Choice, connection, and collaboration: facilitators had flexibility to respond to diverse client choices for each recovery process Strengths-based approach and skill building: women were taught to identify traumatic stress and trauma triggers and what to do once the stress is identified using coping skills, self-care, and social support; women were taught parenting skills and child development |

• Helped women connect past trauma to current recovery • The group helped increase confidence in parenting, ability to cope with stress, and reduced cravings for substances • The group was empowering and increased confidence in parenting |

| Suchman et al.66

United States |

To complete a draft of the Mothers and Toddlers Program (MTP) therapist manual, develop and pilot treatment fidelity/discrimination scales, and conduct a small randomized pilot to test the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of MTP and explore proposed mechanisms of change | Randomized controlled trial | Population (n = 47): mothers in a substance use treatment program, enrolled in an attachment-based individual parenting therapy for mothers, and caring for children 0–36 months Setting: weekly psychotherapy intervention sessions (one hour) for mothers with a clinician, in addition to outpatient substance use treatment |

• Twelve-week individual psychotherapy intervention • The purpose of the intervention was to support the mother in parenting that is more pleasurable and less stressful and encourage the mother’s efforts to openly discuss her concerns • Therapist connected the mother to services that would provide support with basic needs such as food, shelter, childcare, health, and employment |

Safety and trustworthiness: there was a focus on building a trusting relationship between the therapist and the mother Choice, connection, and collaboration: connected to services for basic needs; the therapist conducted sessions based on the direction of the mother and her needs Strengths-based approach and skill building: taught strategies for coping with stress |

• Women who were part of the program focused on mother–child relationships (versus the parent education program) had reduced substance use and mental health issues |

| Tarasoff et al.75

Canada |

To examine and provide a description of services offered in integrated programs within the most populous Canadian province to deepen understanding of the services that comprise integrated programs | Mixed methods | Population (n = 106): pregnant/parenting women with substance use disorders enrolled in either integrated treatment programs or in standard treatment programs Setting: 12 integrated programs in rural and urban areas for pregnant/parenting women with substance use disorders |

• Integrated programs delivered individual substance use treatment • Over half also provided group treatment • Most programs used more than one substance use technique or treatment method, including relapse prevention therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), and motivational interviewing • One program offered emotion-focused couples therapy and mindfulness-based therapy • services included substance use treatment, mental health support, prenatal and primary care, parenting support, childcare, case coordination with child welfare services, life skills training, food security, housing, transportation |

Trauma awareness: being trauma-informed was a major treatment philosophy adopted by participating programs; staff considered the impact of clients’ histories and experiences of trauma; a few programs provided group-based mental health/trauma interventions, including evidence-based treatments Safety and trustworthiness: staff were non-judgmental, supportive, and made women (and their children) feel comfortable and safe; emotional support was provided to clients during case coordination with child welfare services Choice, connection, and collaboration: there was an emphasis on safer substance use and supporting clients’ decisions when operating from a harm reduction philosophy Strengths-based approach and skill building: life skills training was provided as part of individual and group treatment by most integrated programs; programs were strengths-based and focused on client empowerment |

• Clients appreciated home visits tailored to their needs • Clients said the trauma-related groups were helpful and useful • The most helpful aspects of the programs for clients included their relationships with staff, the support offered by staff, and the availability of services/resources beyond substance use treatment, including childcare |

| Teel46

United States |

To (1) explore how a specialized substance use treatment program contributed to improved outcomes; (2) determine priority needs as families began a wraparound intervention; (3) identify goals that were the focus of planning and used final wraparound plans to determine attainment of those goals; and (4) compare the program with standard care. | Qualitative | Population (n = unknown): pregnant/parenting women who entered specialized substance use treatment program Setting: wraparound substance use treatment program. Support teams met at various locations, including the family home, the treatment facility, a church, a jail, and a hospital |

• The “wraparound” intervention team supported families to realize their family vision using a strengths-based and culturally relevant planning process • Families articulated a vision and identified priority needs to inform a mission statement in an initial team meeting, which served as the guide and reference for the team’s work going forward • The goal of the team is to provide consistent, reliable support, helping the woman take care of herself so that she is able to take care of her children |

Trustworthiness and safety: participants noted that the positive nature of the process contributed to their trust in the team; intervention was culturally relevant Choice, connection, and collaboration: the team listened to and honored each woman’s hopes for her life and her family; provided the facilitated collaboration needed to strengthen participating families by (1) helping them build an ongoing support network and access needed resources, (2) supporting the parent’s sustained recovery from substance use, and (3) monitoring the health and development of their young children Strengths-based approach and skill building: each woman’s identified strengths were considered inherent resources that she could draw upon when addressing priority needs and attaining related goals; the intervention helped strengthen families by building resilience by supporting parents in sustaining their recovery and developing healthy ways of coping |

• Strengthened families by building social connections, building concrete supports and building parental resilience contributed to helping mothers build knowledge of parenting, child development and capacity to support the social and emotional competence of their infant • Confidence in the women’s own abilities to secure and use concrete supports was increased • attention, persistence in follow-up, and acknowledgment when progress was made provided life lessons that parents said they would continue to use after their participation ended |

| Troop47

United States |

To explore the experience and views of the postpartum women receiving services in a postpartum program for women with substance use disorders | Qualitative | Population (n = 7): mothers (postpartum) with an identified substance use disorder and part of a comprehensive, post-delivery care program for mothers; mostly white/Caucasian Setting: academic medical center offering substance use treatment for postpartum women with substance use disorders |

• Offered buprenorphine maintenance treatment for opioid use disorder • Provided mental health services • Offered peer support and education • Provided postnatal health services for mother and baby and health system navigation • Provided a comprehensive, post-delivery care program for mothers with substance use disorder through a phased system of care (until their child’s second birthday) • A “medical-home” model supported a recovery journey that was physical, emotional, spiritual, and considered the environment and sociopolitical aspects of women’s lives |