Abstract

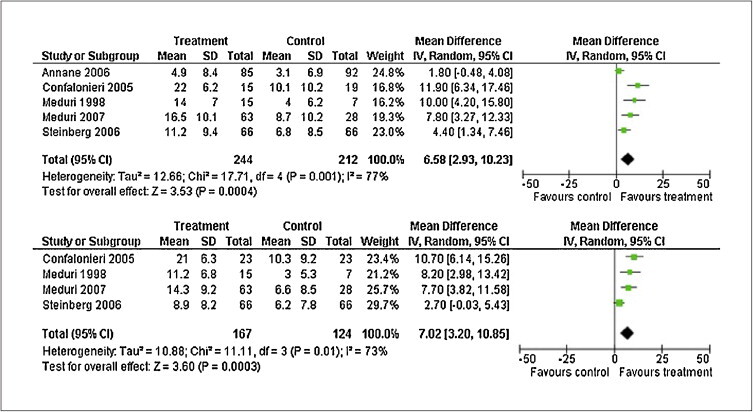

Based on molecular mechanisms and physiologic data, a strong association has been established between dysregulated systemic inflammation and progression of ARDS. In ARDS patients, glucocorticoid receptor-mediated down-regulation of systemic inflammation is essential to restore homeostasis, decrease morbidity and improve survival and can be significantly enhanced with prolonged low-to-moderate dose glucocorticoid treatment. A large body of evidence supports a strong association between prolonged glucocorticoid treatment-induced down-regulation of the inflammatory response and improvement in pulmonary and extrapulmonary physiology. The balance of the available data from controlled trials provides consistent strong level of evidence (grade 1B) for improving patient-centered outcomes. The sizable increase in mechanical ventilation-free days (weighted mean difference, 6.58 days; 95% CI, 2.93 –10.23; P < 0.001) and ICU-free days (weighted mean difference, 7.02 days; 95% CI, 3.20–10.85; P < 0.001) by day 28 is superior to any investigated intervention in ARDS. The largest meta-analysis on the subject concluded that treatment was associated with a significant risk reduction (RR = 0.62, 95% CI: 0.43–0.91; P = 0.01) in mortality and that the in-hospital number needed to treat to save one life was 4 (95% CI 2.4–10). The balance of the available data, however, originates from small controlled trials with a moderate degree of heterogeneity and provides weak evidence (grade 2B) for a survival benefit. Treatment decisions involve a tradeoff between benefits and risks, as well as costs. This low cost highly effective therapy is familiar to every physician and has a low risk profile when secondary prevention measures are implemented.

In this issue.

Does my patient really have ARDS?

L. Brochard, Geneva, Switzerland.

Mechanical ventilation during acute lung injury: current recommendations and new concepts

L. Del Sorbo et al., Torino, Italy

Prone positioning in acute respiratory distress syndrome: When and How?

F. Roche-Campo et al., Barcelona, Spain

Pathophysiology of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Glucocorticoid receptor-mediated regulation of inflammation and response to prolonged glucocorticoid treatment

G. Umberto Meduri et al., Memphis, USA

Virus-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome: epidemiology, management and outcome

C.-E. Luyt et al., Paris, France

Lung function and quality of life in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

M. Elizabeth Wilcox and Margaret S. Herridge, Toronto, Canada

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a disease of multifactorial etiology characterized by a specific morphologic lesion termed “diffuse alveolar damage” (DAD) [1]. This chapter will emphasize the inflammatory nature of ARDS, the regulatory role of the glucocorticoid receptor and how, similar to all inflammatory lung diseases [2], prolonged glucocorticoid treatment is an important therapeutic option. Clinicians assess the progression of ARDS with daily measurements of variables incorporated into the lung injury score (LIS) [3]. Patients with a 1-point or greater reduction in LIS in the first week of mechanical ventilation (resolving ARDS), in contrast to (unresolving ARDS), in contrast to patients with unresolving ARDS, have improved short and long-term outcomes [4]. Experimental and clinical evidence has demonstrated a strong cause and effect relationship between persistence vs. reduction in systemic and pulmonary inflammation and progression (unresolving) vs. resolution (resolving) of ARDS, respectively [4]. In this chapter, the cellular mechanisms involved in activating and regulating inflammation are contrasted between patients with resolving and unresolving ARDS. At the cellular level, patients with unresolving ARDS have deficient glucocorticoid-mediated down-regulation of inflammatory cytokine and chemokine transcription despite elevated levels of circulating cortisol, a condition defined as systemic inflammation-associated acquired glucocorticoid resistance [4]. These patients, contrary to those with resolving ARDS, have persistent elevation over time in both systemic and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) levels of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, markers of alveolar-capillary membrane permeability and fibrogenesis [4]. At the tissue level, the continued production of inflammatory mediators leads to tissue injury, intra- and extravascular coagulation and proliferation of mesenchymal cells, all resulting in maladaptive lung repair and progression of extrapulmonary organ dysfunction [4]. High levels, contrary to low-moderate levels, of inflammatory cytokines also promote bacterial growth and increase susceptibility to nosocomial infections [5].

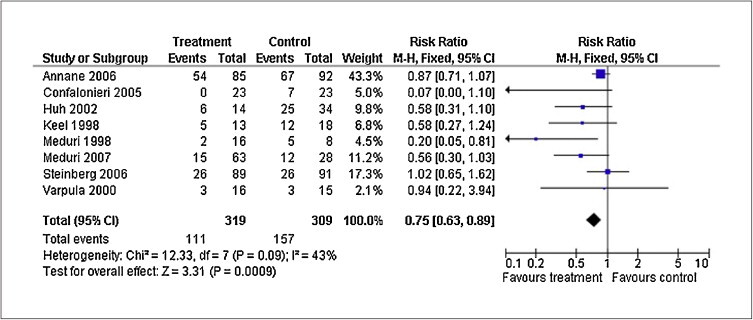

In ARDS, down-regulation of systemic inflammation is essential to restoring homeostasis, decreasing organ dysfunction and morbidity and improving survival. Prolonged low-moderate dose glucocorticoid therapy promotes down-regulation of inflammatory cytokine transcription at the cellular level by enhancing activated glucocorticoid receptor α (GC-GRα)-mediated down-regulation of transcription factor nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) [4]. Eight controlled studies have consistently reported a significant reduction in markers of systemic inflammation, pulmonary and extrapulmonary organ dysfunction scores, duration of mechanical ventilation and intensive care unit length of stay [6]. In the aggregate (N = 628), reduction in mortality was substantial for all patients (RR = 0.75, 95% CI: 0.63 to 0.89; P < 0.001; I2 43%) and for those treated before day 14 (RR = 0.71, 95% CI: 0.59 to 0.85; P < 0.001; I2 40%). Despite the lack of financial incentives to educate intensivists [7], this treatment is now used in 50% of patients with ARDS [8]. Much of this chapter was previously published in a recent review [4].

Systemic inflammation and tissue host defense response

Systemic inflammation is a highly organized response to infectious and noninfectious threats to homeostasis that includes the activation of at least five major programs:

-

(1)

tissue host defense response [9];

-

(2)

acute-phase reaction;

-

(3)

sickness syndrome (including sickness behavior) [10];

-

(4)

pain program mediated by the afferent sensory and autonomic systems and;

-

(5)

the stress program mediated by the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the locus ceruleus-norepinephrine/sympathetic nervous system [11].

The main effectors of systemic inflammation are inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and IL-6; chemokines and other mediators of inflammation; the acute-phase reactants, mostly of hepatic origin, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), fibrinogen and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; the effectors of the sensory afferent system, such as substance P and of the stress system, namely hypothalamic corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH) and vasopressin, cortisol, the catecholamines norepinephrine and epinephrine and peripheral neuronal CRH (reviewed in reference [11]). Excessive release of inflammatory mediators into the circulation induces tissue changes in vital organs leading to multiple-organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) [12], [13].

The host defense response (HDR) is a tissue-protective response, which serves to destroy, dilute, or contain injurious agents and to repair any resulting damage. The HDR consists of an integrated network of three simultaneously activated pathways (Box 1) [4] – inflammation, coagulation and tissue repair – which account for the observed histological and physiological changes with progression or resolution of ARDS and MODS. Whereas appropriately regulated inflammation – tailored to stimulus and time [11] – is beneficial, excessive or persistent systemic inflammation incites tissue destruction and disease progression [14]. It is the lack of regulation (dysregulated systemic inflammation) of this vital response that is central to the pathogenesis of organ dysfunction in patients with sepsis and ARDS [15], [16]. Improved understanding of the critical role played by the neuroendocrine response in critical illness and the cellular mechanisms that initiate, propagate and limit inflammation [17] have provided a new understanding of the role endogenous and exogenous glucocorticoids play in life-threatening systemic inflammation.

Box 1. Components of the tissue host defense response.

Reproduced with permission from reference [4].

Inflammation

Vasodilatation and stasis

Increased expression of adhesion molecules

Increased permeability of the microvasculature with exudative edema

Leukocyte extravasation*

Release of leukocyte products potentially causing tissue damage

Coagulation

Activation of coagulation

Inhibition of fibrinolysis

Intravascular clotting

Extravascular fibrin deposition

Tissue repair

Angiogenesis

Epithelial growth

Fibroblast migration and proliferation

Deposition of extracellular matrix and remodeling

*Initially polymorph nuclear cells and later monocytes

Progression of acute respiratory distress syndrome: resolving vs. unresolving

ARDS is a disease of multifactorial etiology characterized by a specific morphologic lesion termed “diffuse alveolar damage” (DAD) [1]. ARDS develops rapidly, in most patients within 12–48 h of exposure to infectious or noninfectious insults that can affect the lung directly (via the alveolar compartment) or indirectly (via the vascular compartment) [18]. At presentation, ARDS manifests with severe, diffuse and spatially inhomogeneous HDR of the pulmonary lobules leading to a breakdown in the barrier integrity and gas exchange function of the lung. Every anatomical component of the pulmonary lobule (epithelium, endothelium and interstitium) is involved including the respiratory bronchioles, alveolar ducts and alveoli, as well as arteries and veins. Diffuse injury to the alveolar-capillary membrane (ACM) causes edema of the airspaces and interstitium with a protein-rich neutrophilic exudate, resulting in severe gas exchange and lung compliance abnormalities [19]. Although the term “syndrome” was applied in its original description, [20] ARDS meets all the constitutive elements of a disease process [21]. Translational clinical research has constructed – through a “holistic” level of inquiry – a pathophysiological model of ARDS that fits pathogenesis (biology) with morphological (pathology) and clinical (physiology) findings observed during the longitudinal course of the disease [21].

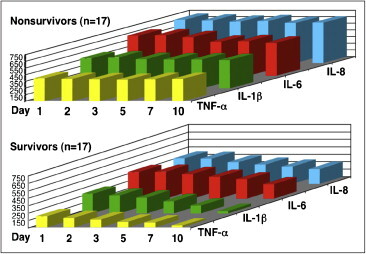

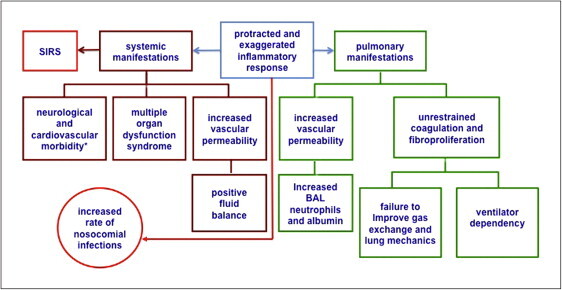

The LIS quantifies the physiologic respiratory impairment in ARDS through the use of a four-point score based on the level of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), ratio of PaO2 to fraction of inspired oxygen (FIO2) (PaO2:FIO2), the static lung compliance and the degree of infiltration present on chest radiograph (one point per quadrant of lung fields involved) [3]. On simple physiological criteria, the evolution of ARDS can be divided into resolving and unresolving based on achieving a 1-point reduction in LIS by day 7 (table I) [4]. Even though, at the onset of ARDS, the two groups may appear similar, daily measurement of lung injury and MODS scores and C-reactive protein levels allow early identification of nonimprovers. Patients failing to improve LIS in the first week of mechanical ventilation (unresolving ARDS) have, significantly higher levels of inflammatory cytokines at the onset of the disease (figure 1) [22], [23]. Moreover, nonimprovers have persistent elevation over time in circulating and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) levels of inflammatory cytokines (figure 1) [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31] and chemokines [32], markers of ACM permeability [27], [33], [34] and fibrogenesis compared to improvers [35]. Patients with unresolving ARDS develop fever (systemic inflammatory response syndrome) in the absence of infection [29], [36], [37] and are also at increased risk for developing nosocomial infections (figure 2) [5], [29]. Elevated levels of systemic cytokines are also involved in the pathogenesis of morbidity frequently encountered in patients with sepsis and ARDS including hyperglycemia [38], short- and long-term neurological dysfunction (delirium [39], neuromuscular weakness [39] and posttraumatic stress disorder [40] and sudden cardiac events in those with underlying atherosclerosis (figure 2) [4], [41].

Table I.

Progression of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

| Resolving | Unresolving | |

|---|---|---|

| Onset of ARDS | ||

| Systemic inflammation | Moderate | Exaggerated |

| HPA-axis responsea | Adequate | Inadequate |

| Over time | ||

| Systemic inflammation | Regulated | Dysregulated |

| Cellular activation/regulation of inflammation | GRα-driven | NF-κB-driven |

| Inflammation, markersb | Decreasing | Persistent elevation |

| ACM permeability, markers | Decreasing | Persistent elevation |

| Fibrogenesis, markersb | Decreasing | Increasing |

| Lung repair (histology) | Adaptive | Maladaptive |

| Reduction in lung injury score | ≥ 1-point by day 7 | < 1-point by day 7 |

| Intensive care unit mortality | Low | High |

Figure 1.

Inflammatory cytokines and chemokines plasma levels in patients with unresolving and resolving acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

Plasma inflammatory cytokine levels over time in survivors and non-survivors. Plasma TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8 levels from days 1 to 10 of sepsis-induced ARDS. On day 1 of ARDS, non-survivors (n = 17) had significantly higher (P < 0.001) TNF-α, IL-1β, IL 6 and IL-8 levels. Over time, non-survivors had persistent elevation, whereas survivors (n = 17) had a rapid decline. Receiver operating curve analysis revealed that at the onset of ARDS, plasma IL-1β (Endogen, Boston, MA), TNF-α, IL-6, (Genzyme, Cambridge, MA) and IL-8 (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) greater than 400 pg/mL were prognostic of death. When IL-1β values on day 1 of ARDS were categorized as either greater or lower than 400 pg/mL, high values of IL-1β were prognostic of death (relative risk = 3.75; 95% CI = 1.08–13.07) and independent of the presence of sepsis or shock, APACHE II score, cause of ARDS and MODS score. These findings indicate that loss of autoregulation is an early phenomenon.

Figure 2.

Pathophysiological manifestations of dysregulated systemic inflammation in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

Dysregulated systemic inflammation leads to changes at the pulmonary and systemic levels [9]. In the lungs, persistent elevation of inflammatory mediators sustains inflammation with resulting tissue injury, alveolar-capillary membrane permeability, intra- and extravascular coagulation in previously spared lobules and proliferation of mesenchymal cells with deposition of extracellular matrix in previously affected lobules, resulting in maladaptive lung repair. This manifests clinically with failure to improve gas exchange and lung mechanics and persistent BAL neutrophilia. Systemic manifestations include: systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) in the absence of infection, progression of MODS, positive fluid balance and increased rate of nosocomial infections. Additional morbidity attributed to elevated cytokinemia includes hyperglycemia [38], short- and long-term neurological dysfunction (delirium [39], neuromuscular weakness [39] and posttraumatic stress disorder [40] and sudden cardiac events in those with underlying atherosclerosis [41], [128].

Reproduced with permission from reference [4]

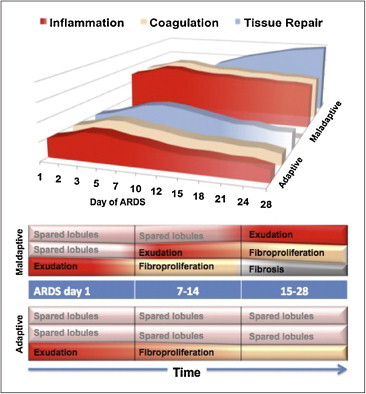

At the tissue level, the continued production of inflammatory mediators sustains inflammation with resulting tissue injury, intra- and extravascular coagulation (exudation) in previously spared lobules and proliferation of mesenchymal cells (fibroproliferation) with deposition of extracellular matrix in previously affected lobules (intra-alveolar, interstitial and endovascular), resulting in maladaptive lung repair evolving ultimately in fibrosis (figure 3) [9]. Histologically, these two processes can be seen adjacent to each other [42] and have been described in detail [43]. Persistent endothelial and epithelial injury leads to protracted vascular permeability (“capillary leak”) in the lung and systemically. Intravascular coagulation and fibroproliferation decreases available pulmonary vascular bed, while intra-alveolar fibrin deposition promotes cell-matrix organization by fibroproliferation [44]. Predictors of poor outcome in ARDS are expressions of persistent and exaggerated (dysregulated) systemic inflammation [9].

Figure 3.

Evolution of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): adaptive vs. maladaptive response

Top: progression of the host defense response (HDR) in patients with adaptive and maladaptive repair. In the first group, the HDR is initially less severe and diminish over time allowing for restoration of anatomy and function. In the second group, the HDR is initially more severe and continues unrestrained over time leading to repeated inflammatory insults and amplification of intra- and extravascular coagulation and fibroproliferation resulting in maladaptive lung repair. Maladaptive lung repair manifest clinically, with persistent hypoxemia, failure to improve lung mechanics and prolonged mechanical ventilation. Bottom: in patients with adaptive response, with progressive reduction in NF-κB-driven TNF–α and IL–1β levels, previously spared lobules are not subjected to new insults, while previously affected lobules undergo an adaptive repair leading to restoration of anatomy and function. In patients with maladaptive response, with persistent elevation in NF-κB-driven TNF–α and IL–1β levels, previously spared lobules are now subjected to new insults and previously affected lobules undergo a maladaptive repair (unrestrained coagulation and fibroproliferation) leading to fibrosis.

Reproduced with permission from reference [4]

Cellular regulation of inflammation – interaction between activated nuclear factor-κB and glucocorticoid receptor α

The body needs mechanisms to keep acute inflammation in check [16] and the GC-activated glucocorticoid receptor α (GRα) complex (GC-GRα) is the most important physiologic inhibitor of inflammation [17] affecting thousands of genes involved in stress-related homeostasis with more transactivation than transrepression [45], [46]. In fact, glucocorticoids exert within few hours transrepression activities by physical interaction with NF-kB preventing its migration to the nucleus and downstream reading of genes encoding for most inflammatory mediators. Transactivation occurs within days of exposure to glucocortioids, the GC-GRa complex migrates to the nucleus and activate the reading of a number of genes encoding for proteins involved in the resolution of inflammation. It is now appreciated that the ubiquitously present cytoplasmic transcription factors nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) – activated by inflammatory signals – and glucocorticoid receptor α – activated by endogenous or exogenous glucocorticoids – have diametrically opposed functions that counteract each other in regulating transcription of inflammatory genes [47], [48]. NF-κB is recognized as the principal driver of the inflammatory response, responsible for the transcription of greater than 100 genes, including TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 [49]. NF-κB activation is central to the pathogenesis of sepsis, lung inflammation and acute lung injury [50], [51]. At the molecular level, glucocorticoids also have very rapid (within minutes) non-genomic effects via interaction with membrane sites or the release of chaperone proteins from the glucocorticoid receptor. These effects include mainly a modulation of cellular responses with decrease in cell adhesion, phosphotyrosine kinases and an increase in annexin 1 externalization [52].

The adrenal gland does not store cortisol; increased secretion occurs from increased synthesis under adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) control. During systemic inflammation, peripherally generated TNF-α and IL-1β stimulate the HPA-axis [53], [54] to limit the inflammatory response through the synthesis of cortisol [55]. Cortisol, secreted into the systemic circulation, readily penetrates cell membranes and exerts its anti-inflammatory effects by activating cytoplasmic GRα. Once activated, NF-κB and GRα can mutually repress each other through a protein-protein interaction that prevents their binding to and proper interaction with promoter and/or enhancer DNA and subsequent regulation of transcriptional activity. Activation of one transcription factor in excess of the binding (inhibitory) capacity of the other shifts cellular responses toward increased (dysregulated) or decreased (regulated) transcription of inflammatory mediators over time [56]. In sepsis and ARDS, the effect of endogenous cortisol on target tissue is blunted at least partly as a result of decreased GR-mediated activity, allowing an uninhibited increase of NF-κB activation in immune cells over time and, hence, leading to an impaired down-regulation of systemic inflammation [23], [57], [58].

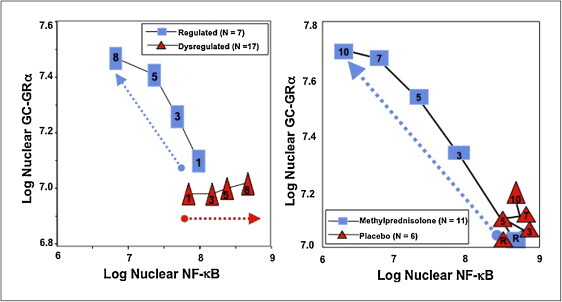

Interaction between activated nuclear factor-κB and glucocorticoid receptor α in acute respiratory distress syndrome

Using an ex vivo model of systemic inflammation, a recent study investigated the intracellular upstream and downstream events associated with DNA-binding of NF-κB and GRα in naive peripheral blood leukocytes (PBLs) stimulated with longitudinal plasma specimens obtained from 28 ARDS patients (most ARDS caused by sepsis) [23]. Intracellular and extracellular laboratory findings were correlated with physiological progression (resolving vs. unresolving) of ARDS in the first week of mechanical ventilation and after blind randomization to prolonged glucocorticoid treatment vs. placebo on day 9 ± 3 of ARDS (described in the next section) [23], [56]. Exposure of naive cells to longitudinal plasma samples from the patients led to divergent directions in NF-κB and GRα activation that reflected the severity of systemic inflammation (defined by plasma TNF-α and IL-1β levels). Activation of one transcription factor in excess of the other shifted cellular responses toward decreased (GRα-driven) or increased (NF-κB-driven) transcription of inflammatory mediators over time [23].

Plasma samples from patients with declining inflammatory cytokine levels (regulated systemic inflammation) over time elicited a progressive increase in all measured aspects of GC-GRα-mediated activity (P = 0.0001) and a corresponding reduction in NF-κB nuclear binding (P = 0.0001) and transcription of TNF-α and IL-1β [23]. In contrast, plasma samples from patients with sustained elevation in inflammatory cytokine levels elicited only modest longitudinal increases in GC-GRα-mediated activity (P = 0.04) and a progressive increase in NF-κB nuclear binding over time (P = 0.0001) that was most striking in non-survivors (dysregulated, NF-κB-driven response) [23]. These findings demonstrate that insufficient GC-GRα-mediated activity is an important mechanism for early loss of homeostatic autoregulation (i.e., down-regulation of NF-κB activation). The divergent directions in NF-κB and GRα activation (figure 4, left) in patients with regulated vs. dysregulated systemic inflammation places insufficient GC-GRα-mediated activity as an early crucial event leading to unchecked NF-κB activation [23]. Deficient GRα activity in naive cells exposed to plasma from patients with dysregulated inflammation was observed despite elevated circulating cortisol and ACTH levels, implicating inflammatory cytokine-driven excess NF-κB activation as an important mechanism for target organ insensitivity (resistance) to cortisol [23]. The concept of inflammation-associated intracellular glucocorticoid resistance in sepsis and acute lung injury is supported by in vitro and animal studies (reviewed in references [59] and [60]). In vitro studies have shown that cytokines may induce – in a dose-dependent fashion – resistance to glucocorticoids by reducing GRα binding affinity to cortisol and/or DNA glucocorticoid response elements [61], [62], [63]. Because glucocorticoid resistance is most frequently observed in patients with excessive inflammation, it remains unclear whether it is a primary phenomenon and/or whether the anti-inflammatory capacity of glucocorticoids is simply overwhelmed by an excessive synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines [64].

Figure 4.

Longitudinal relation on natural logarithmic scales between mean levels of nuclear NF-κB and nuclear GRα: resolving vs. unresolving Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (right) and after randomization to methylprednisolone vs. placebo

Left: plasma samples from patients with sustained elevation in cytokine levels over time elicited only a modest longitudinal increase in GC-GRκ-mediated activity (P = 0.04) and a progressive significant (P = 0.0001) increase in NF-κB nuclear binding over time (dysregulated, NF-κB-driven response). In contrast, in patients with regulated inflammation an inverse relationship was observed between these two transcription factors, with the longitudinal direction of the interaction shifting to the left (decreased NF-κB) and upward (increased GC-GRα). The first interaction is defined as NF-κB–driven (progressive increase in NF-κB-DNA binding and transcription of TNF-α and IL-1β) and the second interaction as GRα-driven response (progressive increase in GRα-DNA binding and transcription of IL-10). Right: longitudinal relation on natural logarithmic scales between mean levels of nuclear NF-αB and nuclear GRα observed by exposing naive PBL to plasma samples collected at randomization (rand) and after 3, 5, 7 and 10 days in the methylprednisolone (open squares) and placebo (open triangles) groups. With methylprednisolone, contrary to placebo, the intracellular relationship between the NF-κB and GRα signaling pathways changed from an initial NF-κB-driven and GR-resistant state to a GRα-driven and GR-sensitive one. It is important to compare the two figures to appreciate how methylprednisolone supplementation restored the equilibrium between activation and suppression of inflammation that is distinctive of a regulated inflammatory response.

Data from references [23], [56]. Reproduced with permission from reference [4]

The above findings are in agreement with two longitudinal studies that investigated NF-κB binding activity directly in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with sepsis or trauma (reviewed in reference [65]) [57], [58]. In both studies [57], [58], non-survivors, contrary to survivors, had a progressive increase in NF-κB activity over time. In one longitudinal study, non-survivors of septic shock had, by day 2 to 6, a 200% increase in NF-κB activity from day 1 [58]. Similarly, NF-κB binding activity on day 3 of ARDS clearly separated patients by outcome, providing an argument for early initiation of prolonged glucocorticoid treatment [23]. Degree of NF-κB and GRα activation also affects histological progression of ARDS. In immunohistochemical analysis of lung tissue, lobules with histologically severe vs. mild fibroproliferation had higher nuclear uptake of NF-κB (13 ± 1.3 vs. 7 ± 2.9; P = 0.01) and lower ratio of GRα:NF-κB nuclear uptake (0.5 ± 0.2 vs.1.5 ± 0.2; P = 0.007) [23]. Thus, measurements in circulating and tissue cells have established that increased NF-κB activation over time is a significant premortem pathogenetic component of lethal sepsis and ARDS and that increased GC-GRα-mediated activity is required for NF-κB down-regulation.

Prolonged glucocorticoid treatment in ALI-ARDS: improves glucocorticoid resistance and decreases NF-κB-driven inflammation-coagulation-tissue repair

The above findings place GC-GRα-mediated down-regulation of NF-κB activity as a critical factor for the reestablishment of homeostasis during the acute, life-threatening systemic inflammation-associated with sepsis and ARDS [23]. In a randomized trial [66], longitudinal measurements of biomarkers provided compelling evidence that prolonged methylprednisolone treatment modifies, at the cellular level, the core pathogenetic mechanism (systemic inflammation-acquired GC resistance) of ARDS and positively affects the biology, histology and physiology of the disease process [65]. Normal blood leukocytes exposed to plasma samples collected during glucocorticoid vs. placebo treatment exhibited rapid, progressive and significant increases in GC-GRα-mediated activities (GRα binding to NF-κB, GRα binding to glucocorticoid response element [GRE] DNA, stimulation of inhibitory protein IκBα and stimulation of IL-10 transcription) and significant reductions in NF-κB κb-DNA-binding (figure 4, right) [4] and transcription of TNF-α and IL-1β [56]. During glucocorticoid treatment, the relationship between NF-κB and GC-GRα signaling pathways changed from an initial NF-κB-driven and GC-GRα-resistant state to a GC-GRα-driven and GC-GRα-sensitive one (figure 4, right) [4], [56]. A prolonged glucocorticoid treatment-induced increase in GR nuclear translocation was also reported in polymorphonuclear leukocytes of patients with sepsis [67]. As shown in table II , in ARDS, methylprednisolone treatment led to a rapid and sustained reduction in mean plasma and BAL levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1, IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra), soluble TNF receptor 1 and 2 and procollagen amino terminal propeptide type I and III and increases in IL-10 and anti-inflammatory to pro-inflammatory cytokine ratios (IL-1ra:IL-1β, IL-10:TNF-α, IL-10:IL-1β) compared to placebo [32], [35], [56], [68].

Table II.

Biological response to prolonged methylprednisolone treatment

| Biological response to prolonged methylprednisolone treatment | |

|---|---|

| Plasma and bronchoalveolar lavage findings | |

| TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 [10], [11], [12], [13] | Decreased |

| C-reactive protein [31], [70], [72] | |

| IL-8, soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 [32] | Decreased |

| IL-10 and IL-10/ IL-1β IL-10/TNF-α [68] | Increased |

| BAL total protein, albumin, neutrophilia [74], [75] | Decreased |

| Procollagen type I and III [35] | Decreased |

| Ex vivo cellular findings [56] | |

| GRα binding to NF-κB [56] | Increased |

| GRα binding to GRE DNA [56] | Increased |

| Inhibitory protein IκBα [56] | Increased |

| IL-10 mRNA [56] | Increased |

| NF-κB κb-binding [56] | Decreased |

| TNF-α and IL-1β mRNA [56] | Decreased |

Reproduced with permission from reference [4]

Taken together, these findings indicate that systemic inflammation-induced glucocorticoid resistance is an acquired, generalized process mediated by excess NF-κB activation and potentially reversible by increasing GC-GRα activation with quantitatively adequate and prolonged glucocorticoid supplementation. During prolonged glucocorticoid treatment, reduction in inflammation, coagulation and fibroproliferation at the tissue level (figure 2) was associated with a parallel improvement in pulmonary [31], [66], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74] and extrapulmonary organ dysfunction scores [31], [66], [70], [71], [72], [74] and indices of ACM permeability [74], [75]. Importantly, the extent of biological improvement in markers of systemic and pulmonary inflammation demonstrated during prolonged methylprednisolone administration is superior (qualitatively and quantitatively) to any other investigated intervention in ARDS [65]. Experimental evidence supporting the use of prolonged glucocorticoid treatment in acute lung injury-ARDS was recently reviewed [76].

Dysregulated systemic inflammation and increased risk for nosocomial infections

ARDS patients with dysregulated systemic inflammation have a higher rate of nosocomial infections [77], partly due to the effect of elevated inflammatory cytokine levels on intracellular and extracellular bacterial growth [5]. While a moderate degree of local inflammation is required to control infection, excessive release of inflammatory cytokines favors bacterial proliferation and virulence following a U-shaped response. When freshly isolated bacteria (fresh isolates of Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter sp.) obtained from patients with ARDS were exposed in vitro to a lower concentration (10 pg to 250 pg) of TNF–α, IL–1β, or IL–6 – similar to the plasma values detected in ARDS survivors – extracellular and intracellular bacterial growth was not promoted and human monocytic cells were efficient in killing the ingested bacteria [78], [79]. However, when bacteria were exposed to higher concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines, similar to those found in ARDS non-survivors, intracellular and extracellular bacterial growth was enhanced in a dose-dependent fashion [78], [79]. In separate parallel experiments, impairment in intracellular bacterial killing in activated monocytes correlated with the increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, while restoration of monocyte killing function upon exposure to methylprednisolone coincided with the down-regulation of the expression of TNF–α, IL–1β and IL–6 [80]. These data indicate that down-regulation of excessive inflammation is important not only to accelerate disease resolution but also to decrease the risk for development of nosocomial infections.

Prolonged glucocorticoid treatment in ALI-ARDS: factors affecting response

Duration of treatment is an important determinant of both efficacy and toxicity [59]. Optimization of glucocorticoid treatment is affected by three factors: actual biological (not clinical) duration of the disease process (systemic inflammation and critical illness related corticosteroid insufficiency [CIRCI]), recovery time of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis after discontinuing treatment and, cumulative risk associated with prolonged treatment (risk) and the essential role of secondary prevention (risk reduction).

Longitudinal measurements of plasma and BAL inflammatory cytokine levels in ARDS showed that inflammation extends well beyond resolution of respiratory failure [22], [23], [27]. One uncontrolled study found that, despite prolonged methylprednisolone administration, local and systemic inflammation persisted for 14 days (limit of study) [75]. Similar findings were reported in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) for inflammatory mediators on day 10 of treatment [32], [56].

Prolonged glucocorticoid treatment is associated with down-regulation of glucocorticoid receptor levels and suppression of the HPA-axis (reviewed later), affecting systemic inflammation after discontinuing treatment. Experimental and clinical literature (reviewed in reference [81]) underscores the importance of continuing glucocorticoid treatment beyond clinical resolution of acute respiratory failure (extubation). In the recent ARDS network trial, methylprednisolone was removed within 3–4 days of extubation and likely contributed, as acknowledged by the authors, to the deterioration in PaO2:FIO2 ratio and higher rate of re-intubation and associated mortality [74], [81]. In two other ARDS trials [31], [66], glucocorticoid treatment was continued up to 18 days to maintain reduced inflammation [31], [66]. This prolonged glucocorticoid treatment was not associated with relapse of ARDS.

Table III shows potential complications masked by or associated with prolonged glucocorticoid treatment and secondary prevention measures [31], [66]. While the risk for infection and neuromuscular weakness is not increased during low-to-moderate dose prolonged glucocorticoid treatment (reviewed below), it is still very important to implement secondary prevention for the following reasons:

-

•

infection surveillance. Failed or delayed recognition of nosocomial infections in the presence of a blunted febrile response represents a serious threat to the recovery of patients receiving prolonged glucocorticoid treatment [59]. In two randomized trials [31], [66] that incorporated infection surveillance, nosocomial infections were frequently (56%) identified in the absence of fever. The infection surveillance protocol incorporated bronchoscopy with bilateral BAL at 5- to 7-day intervals in intubated patients (without contraindication) and a systematic diagnostic protocol when patients developed clinical and laboratory signs suggestive of infection in the absence of fever [82];

-

•

increased risk for neuromuscular weakness with neuromuscular blocking agents. The combination of glucocorticoids and neuromuscular blocking agents versus glucocorticoids alone significantly increases the risk for prolonged neuromuscular weakness [83]. For this reason, using neuromuscular blocking agents is strongly discouraged in patients receiving concomitant glucocorticoid treatment, particularly when other risk factors are present (sepsis, aminoglycosides, etc.);

-

•

glucocorticoid treatment can impair glycemic control. It is well established that exogenous glucocorticoids administered as a bolus produce hyperglycemic variability, an independent predictor of ICU and hospital mortality [84]. Two studies have shown that glucocorticoid infusion is superior to intermittent boluses in preventing glycemic variability by decreasing changes in insulin infusion rate [85], [86];

-

•

avoidance of rebound inflammation. There is ample evidence [35], [87], [88], [89], [90], [91], [92], [93], [94] that early removal of glucocorticoid treatment may lead to rebound inflammation and an exaggerated cytokine response to endotoxin [95]. Experimental work has shown that short-term exposure of alveolar macrophages [96] or animals to dexamethasone is followed by enhanced inflammatory cytokine response to endotoxin [97]. Similarly, normal human subjects pretreated with hydrocortisone had significantly higher TNF-α and IL-6 response after endotoxin challenge compared to controls [98]. Two potential mechanisms may explain rebound inflammation: homologous down-regulation and GC-induced adrenal insufficiency. Glucocorticoid treatment down-regulates glucocorticoid receptor levels in most cell types, thereby decreasing the efficacy of the treatment. The mechanisms of homologous down-regulation have been reviewed elsewhere [99]. Down-regulation occurs at both the transcriptional and translational level and hormone treatment decreases receptor half-life by approximately 50% [99]. In experimental animals, overexpression of glucocorticoid receptors improves resistance to endotoxin-mediated septic shock, while glucocorticoid receptor blockade increases mortality [100]. No study (to the best of our knowledge) has investigated recovery of glucocorticoid receptor levels and function following prolonged glucocorticoid treatment in patients with sepsis or ARDS.

Table III.

Potential complications masked by or associated with prolonged glucocorticoid treatment and secondary prevention measures

| Potential complications | Secondary prevention measures |

|---|---|

| Glucocorticoids blunt the febrile response leading to failed or delayed recognition of nosocomial infections [31], [66] | Surveillance BAL sampling at 5- to 7-day intervals in intubated patients Systematic diagnostic protocol if patient develops signs of infectiona |

| Glucocorticoids given in combination with neuromuscular blocking agents increase the risk for prolonged neuromuscular weakness [83] | Avoid concomitant use of neuromuscular blocking agents |

| Glucocorticoids given as intermittent bolus produce glycemic variability [84] | Following an initial bolus, administer glucocorticoids as a constant infusion [85], [86] |

| Glucocorticoids given in doses greater than 250 mg hydrocortisone per day may increase risk of gastrointestinal ulcers [116], [117] | Ensure stress ulcer prophylaxis with either a H2-receptor antagonist or a proton pump inhibitor is used in all patients [120] |

| Rapid glucocorticoid tapering is associated with rebound inflammation and clinical deterioration [35], [87], [88], [89], [90], [91], [92], [93], [94] | Slow tapering over 9–12 days. During and after tapering, monitor CRP and clinical variables; if patient deteriorates escalate to prior dosage or restart treatment |

Clinical and laboratory signs suggestive of infection in the absence of fever or hypothermia include increase in immature neutrophil count (≥ 3%), unexplained increase in minute ventilation (≥ 30%), unexplained increase in MODS score, worsening metabolic acidosis and unexplained increase in C-reactive protein level.

Reproduced with permission from reference [130]

Prolonged glucocorticoid treatment in ALI-ARDS: effect on disease resolution and duration of mechanical ventilation

Eight controlled studies (five randomized and three concurrent case-controlled) have evaluated the effectiveness of prolonged glucocorticoid treatment in patients with early ALI-ARDS (N = 314) [31], [72], [73] and late ARDS (N = 314) [66], [69], [70], [71], [74] and were the subject of two recent meta-analyses (limited to studies that have investigated pronged treatment) [6], [81]. Table IV [4] shows dosage and duration of treatment, while table V [4] shows important patient-centered outcome variables. These trials consistently reported that treatment-induced reduction in markers of systemic inflammation [31], [66], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74] was associated with significant improvement in PaO2:FIO2 [31], [66], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74] and a significant reduction in MODS score [31], [66], [70], [71], [72], [74] duration of mechanical ventilation, [31], [66], [72], [73], [74] and intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay (all with P values < 0.05) [31], [66], [72], [74] These consistently reproducible findings [31], [66], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74] provide additional support for a causal relationship between reduction in systemic inflammation and resolution of ARDS that is further reinforced by experimental and clinical data showing rebound inflammation following early removal of glucocorticoid treatment leads to recrudescence of ARDS that improves with re-institution of glucocorticoid therapy [35], [69], [87], [88], [89], [90], [91].

Table IV.

Prolonged glucocorticoid treatment in ALI-ARDS: Type of study, number of patients, dosage, duration of treatment and tapering

| Study | Type of study | No. of patients | Initial daily doseb | Duration (days) | Taper (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early ALI-ARDS | 3/3 RCTs | 314 | 40–80 mg | 7–21 | 1/3 yes |

| Confalonieri, 2005 | RCT | 46 | 48 mg | 7 | No |

| Annane, 2006 | RCT | 177 | 40 mg | 7 | No |

| Meduri, 2007 | RCT | 91 | 1 mg/kg | Up to 21a | Yes [7] |

| Late ARDS | 2/5 RCTs | 314 | 100–250 mg | 7–27 | 5/5 yes |

| Meduri, 1998 | RCT | 24 | 2 mg/kg | Up to 21a | Yes [11] |

| Keel, 1998 | Case control | 31 | 100–250 mg | 8 | Yes (NA) |

| Varpula, 2000 | Case control | 31 | 120 mg | Up to 27 | Yes (NA) |

| Huh, 2002 | Case control | 48 | 2 mg/kg | Up to 21a | Yes [11] |

| Steinberg, 2006 | RCT | 180 | 2 mg/kg | Up to 21a | Yes [3], [4] |

RCT: randomized controlled trial; NA: not available; d: days.

Treatment was continued at full dose for 14 days followed by a lower dosage for 7 days before final tapering. In two trials, if the patient was extubated before day 14, the treatment protocol was advanced to day 15 [31], [66]. In one trial, treatment was rapidly tapered (0.5 to 1.5 days) 48 h after extubation [74].

Methylprednisolone equivalent.

Reproduced with permission from reference [4]

Table V.

Prolonged glucocorticoid treatment in ALI-ARDS: overall mortality, mortality for treatment initiated before day 14 of ARDS, improvement in markers of systemic inflammation, gas exchange, duration of mechanical ventilation and ICU stay and infections after study entry

| Study | Hospital mortalitya for treatment initiated |

Reduction in inflammation | Improvement in PaO2:FiO2 | Reduction in MV duration | Reduction in ICU stay | Rate of infection | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At any time | Before day 14 | ||||||

|

Early ALI-ARDS (≤ 3 d) |

40% vs. 60% |

40% vs. 60% |

3 of 3 |

3 of 3 |

3 of 3 |

2 of 2 |

0.30 vs. 0.39 |

| Confalonieri, 2005b |

0.0% vs. 30% |

0.0% vs. 30% |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

0 vs. 0.17 |

| Annane, 2006 |

64% vs. 73% |

64% vs. 73% |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

NR |

0.14 vs. 0.13 |

| Meduri, 2007b | 24% vs. 43% | 24% vs. 43% | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0.63 vs. 1.43 |

|

Late ARDS (≥ 5 d) |

28% vs. 43% |

26% vs. 45% |

5 of 5 |

5 of 5 |

2 of 3 |

2 of 3 |

0.43 vs. 0.51 |

| Meduri, 1998 |

12% vs. 62% |

13% vs. 57% |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

1.50 vs. 1.25 |

| Keel, 1998 |

38% vs. 67% |

NA |

Yes |

Yes |

NR |

NR |

0 vs. NR |

| Varpula, 2000 |

19% vs. 20% (30d) |

19% vs. 20% (30d) |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

0.56 vs. 0.33 |

| Huh, 2002 |

43% vs. 74% |

43% vs. 74% |

Yes |

Yes |

NR |

NR |

NR |

| Steinberg, 2006 | 29% vs. 29% (60d) | 27% vs. 36% (60d) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0.31 vs. 0.47 |

| Early and Late ARDS | 35% vs. 51% | 35% vs. 54% | 8 of 8 | 8 of 8 | 5 of 6 | 4 of 5 | 0.36 vs. 0.44 |

NA: not available or not applicable; NR: not reported; d: days; MV: mechanical ventilation; ICU: intensive care unit. Rate of infection = number of infections divided by number of patients.

Comparisons are reported as glucocorticoid-treated vs. control.

Mortality is reported as hospital mortality unless specified otherwise in parenthesis.

In two positive trials [31], [72], improvement in lung function (PaO2:FiO2 or lung injury score) was the primary outcome variable.

Reproduced with permission from reference [4]

Four of the five randomized trials provided Kaplan Meier curves for continuation of mechanical ventilation; each showed a 2-fold or greater rate of extubation in the first 5 to 7 days of treatment compared to placebo [31], [66], [72], [74]. In the ARDS network trial, the treated group had – before discontinuation of treatment – a noteworthy 9.5 days’ reduction in duration of mechanical ventilation (14.1 ± 1.7 vs. 23.6 ± 2.9; P = 0.006) and more patients discharged home after initial weaning (62% vs. 49%; P = 0.006) [74]. As shown in figure 5 , analysis of randomized trials showed a sizable increase in the number of mechanical ventilation-free days (weighted mean difference, 6.58 days; 95% CI, 2.93–10.23; P < 0.001) and ICU-free days to day 28 (weighted mean difference, 7.02 days; 95% CI 3.20–10.85; P < 0.001), that is 3-fold greater than the one reported with low tidal volume ventilation (12 ± 11 vs. 10 ± 11; P = 0.007) [101] or conservative strategy of fluid-management (14.6 ± 0.5 vs. 12.1 ± 0.5, P < 0.001) [102]. The reduction in duration of mechanical ventilation and ICU length of stay is associated with a substantial reduction in health care expenditure [103]. While, recent meta-analyses (limited to prolonged treatment [6], [81] or incorporating both short and prolonged treatment [104], [105]) and reviews [106] have reached different conclusions on the quality of evidence supporting a survival benefit, all concur that the quality of evidence for reduction in duration of mechanical ventilation is moderate or strong.

Figure 5.

Effects of prolonged glucocorticoid treatment on mechanical ventilation (top) and intensive care unit (bottom) -free days to day 28

Reproduced with permission from reference [4]

Prolonged glucocorticoid treatment in ALI-ARDS: effect on preventing development or progression of ALI-ARDS

Controlled trials have also prospectively evaluated the impact of early initiation of glucocorticoid treatment on preventing progression of the temporal continuum of systemic inflammation in patients with, or at risk for, ARDS [31], [72], [107], [108]. A prospective controlled study (N = 72) found that the intraoperative intravenous administration of 250 mg of methylprednisolone just before pulmonary artery ligation during pneumonectomy reduced the incidence of postsurgical ARDS (0% vs. 13.5%; P < 0.05) and duration of hospital stay (6.1 days vs. 11.9 days, P = 0.02) [107]. Early treatment with hydrocortisone in patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia prevented progression to septic shock (0% vs. 43%; P = 0.001) and ARDS (0% vs. 17%; P = 0.11) [72] and in patients with early ARDS, prolonged methylprednisolone treatment prevented progression to respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation (42% vs. 100%; P = 0.02) [108] or progression to unresolving ARDS (8% vs. 36%; P = 0.002) [31]. These results contrast with the negative findings of older trials investigating a time-limited (24–48 h) massive daily dose of glucocorticoids [104].

Prolonged glucocorticoid treatment in ALI-ARDS: risk/benefits ratio

Treatment decisions involve a tradeoff between benefits and risks, as well as costs [109]. Side effects attributed to steroid treatment, such as an increased risk of infection and neuromuscular dysfunction, have partly tempered enthusiasm for their broader use in sepsis and ARDS [110]. In recent years, however, substantial evidence has accumulated showing that systemic inflammation is also implicated in the pathogenesis of these complications (figure 3) [5], [29], [39], suggesting that down-regulation of systemic inflammation with prolonged low-to-moderate dose glucocorticoid treatment could theoretically prevent, or partly offset, their development and/or progression. As shown in table V, glucocorticoid treatment was not associated with an increased rate of nosocomial infection. Contrary to older studies investigating a time-limited (24–48 h) massive daily dose of glucocorticoids (methylprednisolone, up to 120 mg/kg par day) [111], [112], recent trials have not reported an increased rate of nosocomial infections. Moreover, new cumulative evidence (reviewed in references [5], [113] indicates that, in ARDS and severe sepsis, down-regulation of life-threatening systemic inflammation with prolonged low-to-moderate dose glucocorticoid treatment improves innate immunity [93], [114] and provides an environment less favorable to the intra- and extracellular growth of bacteria (see above) [80], [115].

In three randomized trials, the rates of gastrointestinal bleeding were monitored and no difference between treatment and placebo groups was detected [31], [72], [73]. Increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding has been associated with glucocorticoid doses greater than 250 mg of hydrocortisone or equivalent [116], [117]. Though this association was reported in retrospective reviews, meta-analyses failed to correlate glucocorticoid use to increased rates of gastrointestinal bleeding in patients without other risk factors [118], [119]. For this reason current guidelines recommend patients on greater than 250 mg hydrocortisone with at least one other minor risk factor for stress ulcers should receive stress ulcer prophylaxis with either a H2-receptor antagonist or a proton pump inhibitor [120]. Moreover, there is evidence that glucocorticoids may protect the gastrointestinal tract in patients with adrenal insufficiency deficiency, acute stress and sepsis [121], [122].

In the reviewed studies, the incidence of neuromuscular weakness was similar in the treatment and placebo groups (17% vs. 18%) [6]. Moveover, two recent publications found no association between prolonged glucocorticoid treatment and electrophysiologically or clinically proven neuromuscular dysfunction [123], [124]. Given that neuromuscular dysfunction is an independent predictor of prolonged weaning [125] and ARDS randomized trials have consistently reported a sizable and significant reduction in duration of mechanical ventilation [31], [66], [72], [73], [74], clinically relevant neuromuscular dysfunction caused by glucocorticoid or glucocorticoid-induced hyperglycemia is unlikely. The aggregate of these consistently reproducible findings shows that desirable effects (table V) clearly outweigh undesirable effects and provide a strong (grade 1B) level of evidence that the sustained anti-inflammatory effect achieved during prolonged glucocorticoid treatment accelerates resolution of ARDS leading to earlier removal of mechanical ventilation. Importantly, the low cost of off-patent methylprednisolone, in the United States approximately $240 for 28 days of intravenous therapy [31], makes this treatment globally and equitably available.

Prolonged glucocorticoid treatment in ALI-ARDS: effect on mortality

Table V[4] shows mortality findings for each study. All but three controlled studies [69], [70], [74] showed a reduction in ICU or hospital mortality and, in one retrospective subgroup analysis, mortality benefits were limited to those with relative adrenal insufficiency [73]. In two of these studies, treatment was associated with significant early physiological improvement; however, rapid dosage reduction [70] or premature removal after extubation (as acknowledged by the authors) [74] may have affected final outcome (see below). The ARDS network trial reported that treated patients had a lower mortality (27% vs. 36%; P = 0.14) when randomized before day 14 and an increased mortality when randomized after day 14 of ARDS (8% vs. 35%; P = 0.01) [74]. The latter subgroup (n = 48), however, had large differences in baseline characteristics and the mortality difference lost significance (P = 0.57) when the analysis was adjusted for these imbalances [126].

As a result of the marked differences in study design and patient characteristics, the limited size of the studies (fewer than 200 patients), the cumulative mortality summary of these studies should be interpreted with some caution. Nevertheless, in the aggregate (N = 628), absolute and relative reduction in mortality was substantial for all patients (16% and 31%) and for those treated before day 14 (19% and 35%). As shown in figure 6 , glucocorticoid treatment was associated with a marked reduction in the risk of death for all patients (RR = 0.75, 95% CI: 0.63 to 0.89; P < 0.001; I2 43%) and for those treated before day 14 (RR = 0.71, 95% CI: 0.59 to 0.85; P < 0.001; I2 40%). However, there was a moderate degree of heterogeneity across the studies, namely differences in timing for initiation, dosage, duration of treatment and tapering and study design. For this reason, a recent consensus statement recommended early initiation of prolonged glucocorticoid treatment for patients with severe ARDS (PaO2:FIO2 < 200 on PEEP 10 cmH2O) and before day 14 for patients with unresolving ARDS (table VI) , grading as weak (grade 2b) the evidence for a survival benefit [52]. This recommendation is supported by recent reviews [8], [105]. While all meta-analyses [6], [81], [104], [105] and reviews [106] call for large clinical trial, there is a general lack of interest in funding this trial via public or private sources.

Figure 6.

Effects of prolonged glucocorticoid treatment on acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) survival

Reproduced with permission from reference [4]

Table VI.

Methylprednisolone treatment of early severe Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and late unresolving ARDS

| Methylprednisolone treatment of early severe ARDS and late unresolving ARDS | ||

|---|---|---|

| Early severe ARDS (PaO2:FiO2 < 200 on PEEP 10 cmH20) | ||

| Time | Administration form | Dosage |

| Loading | Bolus over 30 min | 1 mg/kg |

| Days 1 to 14a, b, c | Infusion at 10 cc/h | 1 mg/kg per day |

| Days 15 to 21a, c | Infusion at 10 cc/h | 0.5 mg/kg per day |

| Days 22 to 25a, c | Infusion at 10 cc/h | 0.25 mg/kg per day |

| Days 26 to 28a, c | Infusion at 10 cc/h | 0.125 mg/kg per day |

| Unresolving ARDS (less than 1-point reduction in lung injury score by day 7 of ARDS) | ||

| Time | Administration form | Dosage |

| Loading | Bolus over 30 min | 2 mg/kg |

| Days 1 to 14a, b, c | Infusion at 10 cc/h | 2 mg/kg per day |

| Days 15 to 21a, c | Infusion at 10 cc/h | 1 mg/kg per day |

| Days 22 to 25a, c | Infusion at 10 cc/h | 0.5 mg/kg per day |

| Days 26 to 28a, c | Infusion at 10 cc/h | 0.25 mg/kg per day |

| Days 29 to 28a, c | Bolus over 30 min | 0.125 mg/kg per day |

IV: intravenous.

The dosage is adjusted to ideal body weight and round up to the nearest 10 mg (i.e., 77 mg round up to 80 mg). The infusion is obtained by adding the daily dosage to 240 cc of normal saline.

Five days after the patient is able to ingest medications, methylprednisolone is administered per os in one single daily equivalent dose. Enteral absorption of methylprednisolone is compromised for days after extubation. Prednisone (available in 1-mg, 5-mg, 10-mg and 20-mg strengths) can be used in place of methylprednisolone.

If between days 1 to 14 the patient is extubated, the patient is advanced to day 15 of drug therapy and tapered according to schedule.

When patients leave the ICU, if they are still not tolerating enteral intake for at least 5 days, they should be given the dosage specified but divided into two doses and given every 12 h IV push until tolerating ingestion of medications by mouth.

Recommendations for treatment

We have reviewed data showing that the drug dosage, timing and duration of administration, weaning protocol and implementation of secondary preventive measures largely determine the benefit-risk of glucocorticoid treatment in ARDS. Table VI shows treatment regimens for early and unresolving ARDS. In agreement with a recent consensus statement from the American College of Critical Care Medicine [8], the results of one randomized trial in patients with early severe ARDS [31] indicates that 1 mg/kg per day of methylprednisolone given as an infusion and tapered over 4 weeks is associated with a favorable risk-benefit profile when secondary preventive measures are implemented. For patients with unresolving ARDS, beneficial effects were shown for treatment (methylprednisolone 2 mg/kg per day) initiated before day 14 of ARDS and continued for at least 2 weeks following extubation 8 [66], [74]. If treatment is initiated after day 14, there is no evidence of either benefit or harm [81], [126]. Treatment response should be monitored with daily measurement of LIS and multiple-organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) scores and C-reactive protein level [31], [72].

Secondary prevention is important to minimize complications. Glucocorticoid treatment should be administered as a continuous infusion (while the patient is in ICU) to minimize glycemic variations [85], [86]. When given concurrently with glucocorticoids, two medications are strongly discourage and, when possible, should be avoided: neuromuscular blocking agents to minimize the risk of neuromuscular weakness [83] and etomidate that causes suppression of cortisol synthesis [127]. Glucocorticoid treatment blunts the febrile response; therefore, infection surveillance is essential to promptly identify and treat nosocomial infections. Finally, in agreement with a recent consensus statement from the American College of Critical Care Medicine [8], a slow glucocorticoid dosage reduction (9–12 days) after a complete course allows recovery of glucocorticoid receptors number and the HPA-axis, thereby reducing the risk of rebound inflammation. Laboratory evidence of physiological deterioration (i.e., worsening PaO2:FiO2) associated with rebound inflammation (increased serum C-reactive protein) after the completion of glucocorticoid treatment may require its re-institution.

Disclosure of interest

the authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

Glossary

- ACM

alveolar-capillary membrane

- ARDS

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- BAL

bronchoalveolar lavage

- DAD

diffuse alveolar damage

- CRH

corticotropin releasing hormone

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- CIRCI

critical illness related corticosteroid insufficiency

- GC-GRα

glucocorticoid receptor α

- GRE

glucocorticoid response element

- HDR

host defense response

- HPA

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal

- ICU

intensive care unit

- IL-1β

interleukin-1β

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-κB

- PEEP

positive end-expiratory pressure

- LIS

lung injury score

- MODS

multiple-organ dysfunction syndrome

- PBLs

peripheral blood leukocytes

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-α

References

- 1.Katzenstein A.L., Bloor C.M., Leibow A.A. Diffuse alveolar damage: the role of oxygen, shock and related factors. A review. Am J Pathol. 1976;85(1):209–228. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jantz M.A., Sahn S.A. Corticosteroids in acute respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(4):1079–1100. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.4.9901075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray J.F., Matthay M.A., Luce J.M., Flick M.R. An expanded definition of the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;138(3):720–723. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/138.3.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meduri G.U., Annane D., Chrousos G.P., Marik P.E., Sinclair S.E. Activation and regulation of systemic inflammation in ARDS: rationale for prolonged glucocorticoid therapy. Chest. 2009;136:1631–1643. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meduri G.U. Clinical review: a paradigm shift: the bidirectional effect of inflammation on bacterial growth. Clinical implications for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care. 2002;6(1):24–29. doi: 10.1186/cc1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang B., Craig J., Eslick G., Seppelt I., McLean A. Use of corticosteroids in acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:1594–1603. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819fb507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burton T. Wall Street Journal; 2002. Why cheap drugs that appear to halt fatal sepsis go unused. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raoof S., Goulet K., Esan A., Hess D.R., Sessler C.N. Severe hypoxemic respiratory failure: part 2--nonventilatory strategies. Chest. 2010;137(6):1437–1448. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meduri G.U. The role of the host defence response in the progression and outcome of ARDS: pathophysiological correlations and response to glucocorticoid treatment. Eur Respir J. 1996;9(12):2650–2670. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09122650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dantzer R., Kelley K.W. Twenty years of research on cytokine-induced sickness behavior. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21(2):153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elenkov I.J., Iezzoni D.G., Daly A., Harris A.G., Chrousos G.P. Cytokine dysregulation, inflammation and well-being. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2005;12(5):255–269. doi: 10.1159/000087104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Imai Y., Parodo J., Kajikawa O., de Perrot M., Fischer S., Edwards V., et al. Injurious mechanical ventilation and end-organ epithelial cell apoptosis and organ dysfunction in an experimental model of acute respiratory distress syndrome. JAMA. 2003;289(16):2104–2112. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.16.2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ranieri V.M., Giunta F., Suter P.M., Slutsky A.S. Mechanical ventilation as a mediator of multisystem organ failure in acute respiratory distress syndrome. JAMA. 2000;284(1):43–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suffredini A.F., Fantuzzi G., Badolato R., Oppenheim J.J., O’Grady N.P. New insights into the biology of the acute-phase response. J Clin Immunol. 1999;19(4):203–214. doi: 10.1023/a:1020563913045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Englert J.A., Fink M.P. The multiple-organ dysfunction syndrome and late-phase mortality in sepsis. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2005;7(5):335–341. doi: 10.1007/s11908-005-0006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mizgerd J.P. Acute lower respiratory tract infection. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(7):716–727. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra074111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rhen T., Cidlowski J.A. Anti-inflammatory action of glucocorticoids. new mechanisms for old drugs. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(16):1711–1723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hudson L.D., Milberg J.A., Anardi D., Maunder R.J. Clinical risks for development of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151(2 Pt 1):293–301. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.2.7842182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steinberg K.P., Hudson L.D. Acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome. The clinical syndrome. Clin Chest Med. 2000;21(3):401–417. doi: 10.1016/s0272-5231(05)70156-8. vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ashbaugh D.G., Bigelow D.B., Petty T.L., Levine B.E. Acute respiratory distress in adults. Lancet. 1967;2(7511):319–323. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(67)90168-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cotran R.S., Kumar V., Robbins S.L. In: Pathologic basis of disease. 5 ed. Cotran R.S., Kumar V., Robbins S.L., editors. W. B. Saunders; Philadelphia: 1994. Cellular injury and cellular death. p. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meduri G.U., Headley S., Kohler G., Stentz F., Tolley E., Umberger R., et al. Persistent elevation of inflammatory cytokines predicts a poor outcome in ARDS. Plasma IL-1 beta and IL-6 levels are consistent and efficient predictors of outcome over time. Chest. 1995;107(4):1062–1673. doi: 10.1378/chest.107.4.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meduri G.U., Muthiah M.P., Carratu P., Eltorky M., Chrousos G.P. Nuclear factor-kappaB- and glucocorticoid receptor alpha- mediated mechanisms in the regulation of systemic and pulmonary inflammation during sepsis and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Evidence for inflammation-induced target tissue resistance to glucocorticoids. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2005;12(6):321–338. doi: 10.1159/000091126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roumen R.M., Hendriks T., van der Ven-Jongekrijg J., Nieuwenhuijzen G.A., Sauerwein R.W., van der Meer J.W., et al. Cytokine patterns in patients after major vascular surgery, hemorrhagic shock and severe blunt trauma. Relation with subsequent adult respiratory distress syndrome and multiple-organ failure. Ann Surg. 1993;218(6):769–776. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199312000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Romaschin A.D., DeMajo W.C., Winton T., D’Costa M., Chang G., Rubin B., et al. Systemic phospholipase A2 and cachectin levels in adult respiratory distress syndrome and multiple-organ failure. Clin Biochem. 1992;25(1):55–60. doi: 10.1016/0009-9120(92)80046-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Groeneveld A.B., Raijmakers P.G., Hack C.E., Thijs L.G. Interleukin 8-related neutrophil elastase and the severity of the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Cytokine. 1995;7(7):746–752. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1995.0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meduri G.U., Kohler G., Headley S., Tolley E., Stentz F., Postlethwaite A. Inflammatory cytokines in the BAL of patients with ARDS. Persistent elevation over time predicts poor outcome. Chest. 1995;108(5):1303–1314. doi: 10.1378/chest.108.5.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baughman R.P., Gunther K.L., Rashkin M.C., Keeton D.A., Pattishall E.N. Changes in the inflammatory response of the lung during acute respiratory distress syndrome: prognostic indicators. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154(1):76–81. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.1.8680703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Headley A.S., Tolley E., Meduri G.U. Infections and the inflammatory response in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Chest. 1997;111(5):1306–1321. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.5.1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parsons P.E., Eisner M.D., Thompson B.T., Matthay M.A., Ancukiewicz M., Bernard G.R., et al. Lower tidal volume ventilation and plasma cytokine markers of inflammation in patients with acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(1):1–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000149854.61192.dc. [discussion 230–232] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meduri G.U., Golden E., Freire A.X., Taylor E., Zaman M., Carson S.J., et al. Methylprednisolone infusion in early severe ARDS: results of a randomized controlled trial. Chest. 2007;131:954–963. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sinclair S.E., Bijoy J., Golden E., Carratu P., Umberger R., Meduri G.U. Interleukin-8 and soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 during acute respiratory distress syndrome and in response to prolonged methylprednisolone treatment. Minerva Pneumologica. 2006;45(2):93–104. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steinberg K.P., Milberg J.A., Martin T.R., Maunder R.J., Cockrill B.A., Hudson L.D. Evolution of bronchoalveolar cell populations in the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150(1):113–122. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.1.8025736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gunther K., Baughman R.P., Rashkin M., Pattishall E. Bronchoalveolar lavage results in patients with sepsis-induced adult respiratory distress syndrome: evaluation of mortality and inflammatory response. Amer Rev Respir Dis. 1993;147:A346. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meduri G.U., Tolley E.A., Chinn A., Stentz F., Postlethwaite A. Procollagen types I and III aminoterminal propeptide levels during acute respiratory distress syndrome and in response to methylprednisolone treatment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158(5 Pt 1):1432–1441. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.5.9801107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andrews C.P., Coalson J.J., Smith J.D., Johanson W.G., Jr. Diagnosis of nosocomial bacterial pneumonia in acute, diffuse lung injury. Chest. 1981;80(3):254–258. doi: 10.1378/chest.80.3.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meduri G.U., Belenchia J.M., Estes R.J., Wunderink R.G., el Torky M., Leeper K.V., Jr. Fibroproliferative phase of ARDS. Clinical findings and effects of corticosteroids. Chest. 1991;100(4):943–952. doi: 10.1378/chest.100.4.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raghavan M., Marik P.E. Stress hyperglycemia and adrenal insufficiency in the critically ill. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;27(3):274–285. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-945533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pustavoitau A., Stevens R.D. Mechanisms of neurologic failure in critical illness. Crit Care Clin. 2008;24(1):1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2007.11.004. vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.von Kanel R., Hepp U., Kraemer B., Traber R., Keel M., Mica L., et al. Evidence for low-grade systemic pro-inflammatory activity in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41(9):744–752. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.El Gamal A., Aleech Y., Umberger R., Meduri G. Sudden cardiac arrest is a leading cause of death in patients with ASCVD admitted to the ICU with acute systemic inflammation. Chest. 2008;134:e587. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bachofen A., Weibel E.R. Alterations of the gas exchange apparatus in adult respiratory insufficiency associated with septicemia. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1977;116(4):589–615. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1977.116.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meduri G.U., Eltorky M., Winer-Muram H.T. The fibroproliferative phase of late adult respiratory distress syndrome. Semin Respir Infect. 1995;10(3):154–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cordier J.F., Peyrol S., Loire R. In: Diseases of the Bronchioles. Epler G.R., editor. Raven Press Ltd; New York: 1994. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia as a model of inflammatory lung disease. p 313–45. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Galon J., Franchimont D., Hiroi N., Frey G., Boettner A., Ehrhart-Bornstein M., et al. Gene profiling reveals unknown enhancing and suppressive actions of glucocorticoids on immune cells. Faseb J. 2002;16(1):61–71. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0245com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ehrchen J., Steinmuller L., Barczyk K., Tenbrock K., Nacken W., Eisenacher M., et al. Glucocorticoids induce differentiation of a specifically activated, anti-inflammatory subtype of human monocytes. Blood. 2007;109(3):1265–1274. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-001115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mastorakos G., Bamberger C., Chrousos G.P. In: Cytokines: stress and immunity. Plotnikoff N.P., Faith R.E., Murgo A.J., Good R.A., editors. FL: CRC Press; Boca Raton: 1999. Neuroendocrine regulation of the immune process. p. 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barnes P.J., Adcock I.M. In: The lung scientific foundations. 2 ed. Crystal R.G., West J.B., Weibel E.R., Barnes P.J., editors. Lippincott-Raven; Philadelphis: 1997. Glucocorticoids receptors. p. 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baeuerle P.A., Baltimore D. Activation of DNA-binding activity in an apparently cytoplasmic precursor of the NF-kappa B transcription factor. Cell. 1988;53(2):211–217. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90382-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fan J., Ye R.D., Malik A.B. Transcriptional mechanisms of acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;281(5):L1037–L1050. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.5.L1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu S.F., Malik A.B. NF-kappa B activation as a pathological mechanism of septic shock and inflammation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290(4):L622–L645. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00477.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marik P.E., Pastores S., Annane D., Meduri G., Sprung C., Arlt W., et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of corticosteroid insufficiency in critical illness: Recommendations of an international task force. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:1937–1949. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31817603ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hermus A.R., Sweep C.G. Cytokines and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1990;37(6):867–871. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(90)90434-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Perlstein R.S., Whitnall M.H., Abrams J.S., Mougey E.H., Neta R. Synergistic roles of interleukin-6, interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor in the adrenocorticotropin response to bacterial lipopolysaccharide in vivo. Endocrinology. 1993;132(3):946–952. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.3.8382602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Munck A., Guyre P.M., Holbrook N.J. Physiological functions of glucocorticoids in stress and their relation to pharmacological actions. Endocr Rev. 1984;5(1):25–44. doi: 10.1210/edrv-5-1-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meduri G.U., Tolley E.A., Chrousos G.P., Stentz F. Prolonged methylprednisolone treatment suppresses systemic inflammation in patients with unresolving acute respiratory distress syndrome. Evidence for inadequate endogenous glucocorticoid secretion and inflammation-induced immune cell resistance to glucocorticoids. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(7):983–991. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.7.2106014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bohrer H., Qiu F., Zimmermann T., Zhang Y., Jllmer T., Mannel D., et al. Role of NF-kappa B in the mortality of sepsis. J Clin Invest. 1997;100(5):972–985. doi: 10.1172/JCI119648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Paterson R.L., Galley H.F., Dhillon J.K., Webster N.R. Increased nuclear factor-kB activation in critically ill patients who die. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(4):1047–1051. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200004000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Meduri G.U. An historical review of glucocorticoid treatment in Sepsis. Disease pathophysiology and the design of treatment investigation. Sepsis. 1999;3:21–38. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Annane D., Bellissant E., Bollaert P.E., Briegel J., Keh D., Kupfer Y. Corticosteroids for treating severe sepsis and septic shock. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(1):CD002243. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002243.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Almawi W.Y., Lipman M.L., Stevens A.C., Zanker B., Hadro E.T., Strom T.B. Abrogation of glucocorticoid-mediated inhibition of T cell proliferation by the synergistic action of IL-1, IL-6 and IFN-gamma. J Immunol. 1991;146(10):3523–3527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kam J.C., Szefler S.J., Surs W., Sher E.R., Leung D.Y. Combination IL-2 and IL-4 reduces glucocorticoid receptor-binding affinity and T cell response to glucocorticoids. J Immunol. 1993;151(7):3460–3466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Spahn J.D., Szefler S.J., Surs W., Doherty D.E., Nimmagadda S.R., Leung D.Y. A novel action of IL-13: induction of diminished monocyte glucocorticoid receptor-binding affinity. J Immunol. 1996;157(6):2654–2659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Farrell R.J., Kelleher D. Glucocorticoid resistance in inflammatory bowel disease. J Endocrinol. 2003;178(3):339–346. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1780339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Meduri G.U., Yates C.R. Systemic inflammation-associated glucocorticoid resistance and outcome of ARDS. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1024:24–53. doi: 10.1196/annals.1321.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Meduri G.U., Headley S., Golden E., Carson S., Umberger R., Kelso T., et al. Effect of prolonged methylprednisolone therapy in unresolving acute respiratory distress syndrome. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280:159–165. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nakamori Y., Ogura H., Koh T., Fujita K., Tanaka H., Sumi Y., et al. The balance between expression of intranuclear NF-kappaB and glucocorticoid receptor in polymorphonuclear leukocytes in SIRS patients. J Trauma. 2005;59(2):308–314. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000185265.63887.5f. [discussion 14–15] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Headley A.S., Meduri G.U., Tolley E., Stentz F. Infections, SIRS and CARS during ARDS and in response to prolonged glucocorticoid treatment (Abstract) Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:A378. [Google Scholar]