Abstract

The pandemic, political upheavals, and social justice efforts in our society have resulted in attention to persistent health disparities and the urgent need to address them. Using a scoping review, we describe published updates to address disparities and targets for interventions to improve gaps in care within Allergy and Immunology. These disparities-related studies provide a broad view of our current understanding of how social determinants of health threaten patient outcomes and our ability to advance health equity efforts in our field. We outline next steps to improve access to care and advance health equity for patients with allergic/immunologic diseases through actions taken at the individual, community, and policy levels, which could be applied outside of our field. Key amongst these are efforts to increase the diversity among our trainees, providers, and scientific teams and enhancing efforts to participate in advocacy work and public health interventions. Addressing health disparities requires advancing our understanding of the interplay between social and structural barriers to care and enacting the needed interventions in various key areas to effect change.

Keywords: health disparities, allergy, immunology, asthma, social determinants of health, health equity, structural racism, allergic rhinitis, food allergy

Introduction

The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (JACI) and Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice (JACI: IP), have each devoted an issue to health disparities in the past year. Developments such as the coronavirus pandemic and increased attention to structural racism have brought about an urgency to identify and address health disparities. Structural determinants of health are social structures and processes that impact a person’s health such as birth location, housing and work conditions, socioeconomic, educational, and community factors, and are not disease specific. There are also upstream societal factors such as institutional and legislative policies that impact health equity. Although we describe some disease specific disparities in this article, our aim is to extend beyond studies describing disparities to highlight interventions or investigational studies performed to mitigate disparities where they exist.

We performed a scoping review of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms “health disparities,” “health status disparities,” “social determinants of health,” “structural determinants of health,” “health inequity,” “structural racism,” “social vulnerabilities,” “economic instability,” and “burden,” paired with terms relevant to allergic and immunologic disorders identified between 2020 and 2022 within JACI and JACI: IP. The authors reviewed articles meeting these parameters in depth. Where interventional studies did not exist, we provide perspective on studies that are needed that may further community and population health, and in some cases considered examples of interventions from other fields and journals that may apply to Allergy and Immunology. We have provided a summary of identified approaches to mitigate disparities in key areas in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary topics and interventions for mitigating health disparities in allergic and immunologic diseases.

| Disease States | |

|---|---|

| Solutions | |

| Atopic Disorders | Employ specialized training and courses to help providers distinguish, recognize, and manage diseases in marginalized patient populations Integrate care gap analysis into the EHR to help providers identify, document, and address mitigation factors for HD Engage in advocacy work to address structural racism and improve equitable distribution of resources Expand techniques and programs to increase diversity of research participants, including engaging with stakeholders in study design Adopt universal use of validated screening tools in areas that serve vulnerable populations to aid in identifying barriers to care and opportunities to intervene Partner with community clinics to improve access to specialists through use of virtual visits |

| Genetic Profiling in Health Disparities | Improve the interpretation of GWAS in assessing disease and prevalence in at-risk populations should incorporate:

|

| Immunologic Disorders | Expand the collection and reporting of epidemiologic data by registries to better understand the impact of SDoH on immunologic disease prevalence, diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes Trial use of technology to enhance patient engagement through as text message reminders and mobile health applications Partner with primary care or pediatrician-based telemedicine referral programs for IEI evaluation based on laboratory or clinical warning-signs to address reduced access to specialists and specialized testing Use specific engagement and education programming targeting marginalized communities to improve HSCT donor registry diversity |

| Health Disparities in COVID | Target outreach using community-based organizations and use culturally appropriate messaging Improve intervention effectiveness by involving affected communities at all stages of planning and implementation Enhance outreach by using mobile clinics, community health workers, and partnerships with trusted intermediaries to better reach marginalized communities. |

| Beyond Race/Ethnic Disparities | |

| Solutions | |

| Gender/Sex | Increase research focus to advance our understanding of how diverse social identities impact diagnosis, management, and outcomes in A/I Improve cultural competency education through didactic courses/modules and community/advocacy work designed with key members of affected communities Create enhanced clinical and work environments that are welcoming, inclusive, and culturally sensitive (i.e. - providing gender affirming care) Use treatment strategies that follow general guidelines for all tissues and organs present in patients, regardless of gender identity Arrange and update publicized accessibility information that does not reinforce dependency of disabled persons on others to engage with a facility or practitioner. Support appropriate accommodations in schools for patients and assure ease of access to facilities for patients who are disabled Expand techniques and programs to increase diversity of research participants Provide interpreter services and assure written communication is appropriately translated |

| LGBTQI+ | |

| Persons With Disabilities | |

| Language | |

| Structural Barriers to Care: Access, Community, and Physical Environment | |

| Solutions | |

| Equitable Access | Increase prevalence and inclusion of Black and Latinx individuals in studies/research, as well as other vulnerable, at-risk groups Establish partnerships with well-respected and trusted community leaders to engage with communities with high disease prevalence Repair relationships between marginalized communities and the health institutions that care for them |

| DEI in Research Participation | Engage with patients from underrepresented communities and their community leaders early on in study design and activities Adopt use of community-based participatory research designs and methods with structures of accountability Focus participant recruitment efforts on subjects from underrepresented backgrounds with intentional engagement and recruitment material Use evidence-based models to interrogate and enhance the relationship between diverse populations and research teams |

| Built Environment | Advocate for rigorous studies screening and treating maternal stress/depression in low-income, urban populations Dismantle systemic practices that increase socioenvironmental issues and contribute to material hardship Identify root causes for social and environmental disparities that impact health outcome Use QI projects and public health programs to provide effective interventions that mitigate exposures to disease triggers Perform geospatial analysis (i.e., using location data) to evaluate at-risk neighborhoods and vulnerable populations that need additional resources |

| Hiring, Training, and Education | |

| Solutions | |

| Hiring Practices | Train admission committee members on unconscious bias Enhance recruitment efforts and foster relationships with HBCUs, SNMA, and LMSA Adjust the interview format to ensure a holistic review of the applicant Increase the diversity of the admissions and hiring committees |

| Training in Health Disparities/Equity | Use previously published toolkits and guiding principles to target academic institutions of various sizes to adapt activities and programs to train providers in HE/HD |

| DEI and Medical Journals | Increase author and editorial diversity Address and correct biased hiring practices by intentionally recruiting and retaining UIMs in medicine and editorial boards Incentivize and enhance funding and mentorship for UIMs at every level of academia, including within academic journal editorial staff |

A/I – Allergy and Immunology; COVID - SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus; DEI – Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion; HER – electronic health record; GWAS – Genome Wide Association Study; HBCU – Historically Black Colleges and Universities; HD – health disparities; HE – health equity; HSCT – Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant; IEI – Inborn Errors of Immunity; LGBTQI+ - Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, queer/questioning, asexual and many other terms (such as non-binary and pansexual); LMSA – Latino Medical; SDoH – Social Determinants of Health; QI – Quality Improvement; Student Association; SNMA – Student National Medical Association; UIMs – Underrepresented in Medicine

As evidence-based interventions are more appropriately defined in allergy-immunology, research into the sustainability of these interventions should be studied to ensure continued progress.

Health Disparities in Allergy-Immunology Disease States

Atopic Clinical Disorders

Asthma

Recent publications about disparities and inequities in asthma emphasize the impact of socioeconomic status (SES), exposures, patient preferences, and provider interactions on health. A review revealed that low SES is associated with higher rates of asthma-related healthcare utilization (emergency room visits, hospitalizations, and readmission) and morbidity (increased ventilation/intubation rates).1 A similar evaluation analyzing data from a patient registry in the UK highlighted that marginalized patients also have higher rates of healthcare utilization and disease burden, with increased atopy and allergic biomarkers (FeNO, total IgE, and eosinophilia).2 Additionally, an evaluation of demographic information from participants in the PeRson EmPowered Asthma RElief randomized trial revealed a higher prevalence of asthma morbidity in participants who lived in poverty, despite having adequate health literacy.3 Patients with lower SES were more likely to have lower educational attainment (did not graduate high school) and were predominantly Spanish-speaking or unemployed. Investigators uniquely identified increased perceived stress being related to increased asthma morbidity. Others found that significant financial stress due to out-of-pocket expenses from higher urgent care or emergency room visits rates substantially burdened low-income patients with asthma.4

Food Allergy

Food allergies (FA) disproportionately affect Black persons more than other racial groups.5 Historic red-lining and creation of food deserts have contributed to the lack of access to healthy food options for these patients resulting in food insecurity (FI).6 The AAAAI Adverse Reactions to Foods Work Group Report noted that approximately 21% of US children with FA experience FI; disproportionately affecting the Latinx, Indigenous, and Black communities.7 However, only one-third of US physicians systematically screen for FI in their practices. Additionally, 71.2% of surveyed physicians were unaware of the impact of FI on their patients with FA and did not discuss financial barriers to accessing specialized dietary foods.7

Allergic Rhinitis

Allergic rhinitis (AR) has a high prevalence in the general population but is underdiagnosed in under-resourced patients.8,9 Differential sensitization and exposure to mold, cockroach, and mouse allergens are linked to the urban built environment, low socioeconomic status, and predominantly affects Black and Latinx populations contributing to disease in these groups. As a result of reduced recognition and treatment of AR, as highlighted by the AAAAI Work Group Report of the Committee on the Underserved disparate outcomes for Black and Latinx patients exist.10 A study of school-aged majority Black and Medicaid insured children with co-morbid asthma found that children with poorly controlled, symptomatic asthma, were more likely to have an elevated FeNO and comorbid AR.11 These children were undertreated for AR with only 45% of these participants receiving therapy. Of those receiving treatment, the therapeutics prescribed were not uniformly standard of care medications. Additionally, allergen immunotherapy (AIT) in these patients was either less likely to be prescribed or prematurely discontinued.

Other Atopic Conditions

There is minimal published data in recognizing health disparities in other atopic disorders (i.e. - atopic dermatitis, eosinophilic disorders, and mast cell disorders) and none have interventional studies to address health disparities. To better guide understanding and interventions in these diseases, improved attention is warranted.

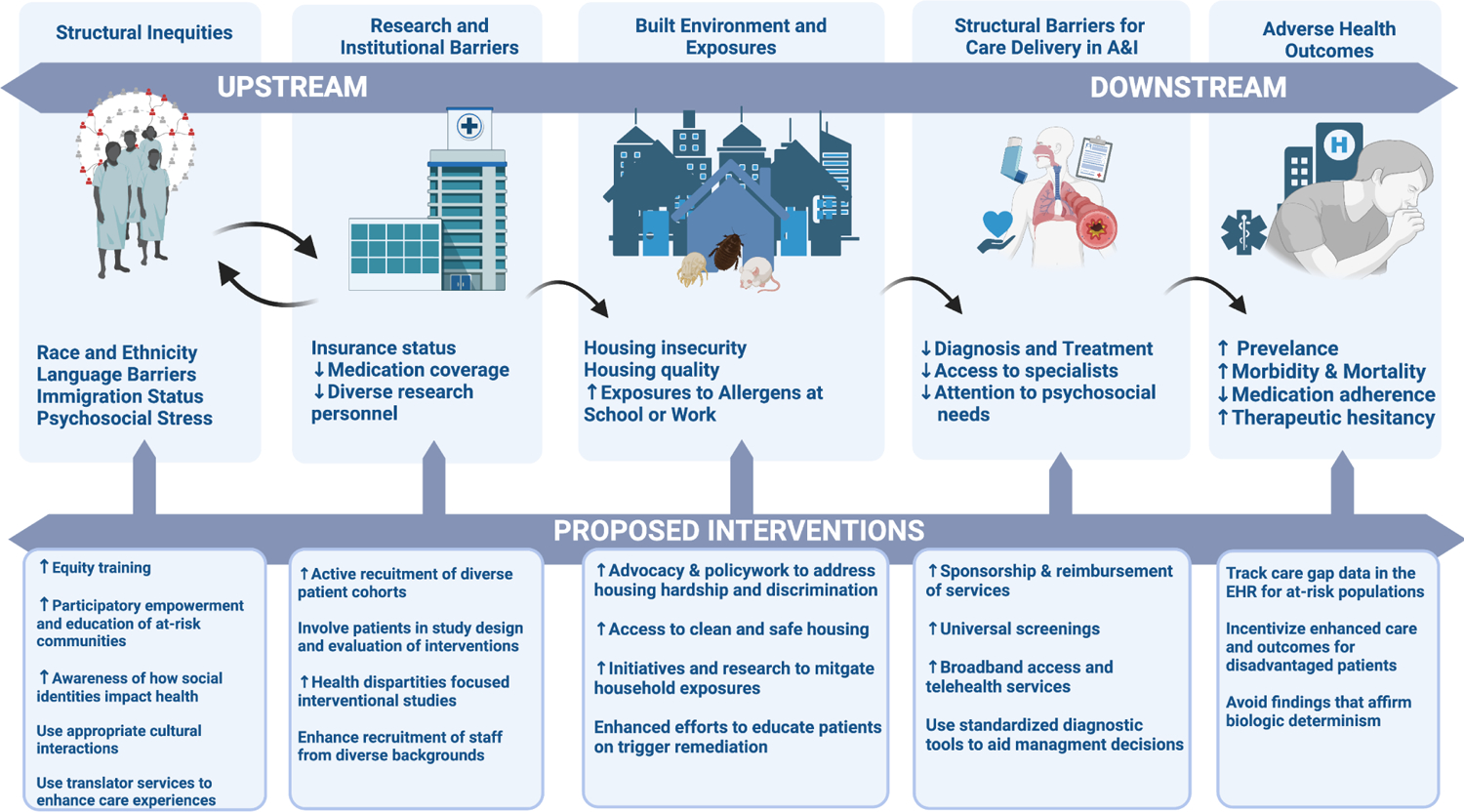

Mitigating Disparities in Atopic Clinical Disorders

Beyond defining the problem, several interventional studies and perspectives have been published to aid in addressing asthma morbidity for at-risk populations and could be extended to advance equity efforts in other atopic conditions. An important first step is increasing providers’ understanding of the impact of social determinants of health (SDoH) on patient outcomes. This can be accomplished through focused training programs and by engaging with key stakeholders in under-resourced communities. Through advocacy work, reforming policies, and creating community partnerships, Allergy-Immunology providers can begin to address the upstream, discriminatory practices and policies that reinforce inequitable distribution of resources to Black, Latinx, and other groups from vulnerable health populations (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Framework for upstream and downstream effects of health disparities in allergic and immunologic diseases

Upstream factors of structural inequity, barriers to research, and the built environment effects on adverse outcomes and barriers to care in allergy-immunology are shown. Proposed interventions and examples of future research needs are described. Created using Biorender.com

By using a standardized severity or risk grading tool that makes use of clinical data in the electronic health record, providers could potentially circumvent issues that bias diagnosis and management of disease in under-resourced populations and improve clinical decision making. Because geographic proximity to subspecialists and work constraints influence the care patients can access, equity-focused interventions should identify patients requiring specialized high-resource care and prioritize access, education, and medication availability in those groups. One report describes a provider-led, school-based program in New Orleans that provided stock epinephrine to schools in under-resourced communities.12 Another interventional study in lung cancer treatment used alerts in the EHR, race-specific treatment completion (or adherence) rates, and a nurse navigator to enhance care for minoritized patients.13 These are examples of interventions that could be adapted and implemented in allergy and immunology.

Ultimately, by including key stakeholders in study design creation and using directed feedback, we can increase the likelihood of creating culturally appropriate interventions that address the impact of socioeconomic status on disease-related morbidity.

Genetic Profiles for Disparities in Atopic Diseases

There were several recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) published in JACI/JACI: In Practice that aimed to advance the understanding and identification of genetic factors on the susceptibility, severity, and biologic nature of allergic diseases. They illustrate a rising interest in associating genetic factors with SDoH, marginalized communities, and health disparities. Several single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been identified in different cohorts with varying results in each, several of which will be discussed below.

A high frequency risk loci (rs60242841) was associated with the atopic march from AD to asthma in people of African ancestry in large pediatric cohorts.14 And certain SNPs were inferred to increase clinical predisposition to atopic disease trajectory in those self-identifying as Black. Another study compared Peruvian children with and without asthma based on indigenous versus Spanish-European ancestry and found that those with native indigenous ancestry had higher IgE levels (associated with the HLADR/DQ region; correlated with risk loci rs3135348) and FEV1 values (correlated with risk loci rs4410198).15 To evaluate genetic risk loci associated with asthma-related hospitalizations, a cohort study assessed White British adults and 2 replication cohorts of Latinx children and adolescents from Hartford, Connecticut and San Juan, Puerto Rico.16 No associations to previously reported gene loci were identified in their study, but unique SNPs associated with higher rates of asthma-related hospitalizations and severe asthma exacerbations were identified.

A prospective cohort study of Black and White children identified an association with African ancestry and asthma readmission (OR 1.11, 95% CI 1.05–1.18 for every 10% increase in African ancestry, p <0.001).17 However, when accounting for the impact of social and environmental variables on readmission (aeroallergen sensitization, outdoor exposures, indoor exposures, disease management, community factors, and hardship), African ancestry was no longer associated with readmission (p = 0.388). Similarly, no association between African genetic ancestry and atopic dermatitis susceptibility and disease control was found in a study assessing over 80,000 individuals aged 2–100 years old although atopic dermatitis was more common and less well-controlled in self-identified, African Americans compared to non-Hispanic, White individuals.18

Future approaches in assessing genetic associations of health disparities that include environmental exposures, structural bias, and social determinants of health on disease outcomes and morbidity can better reflect the biopsychosocial impacts on health disparities.19,20

Immunologic Disorders

The Work Group Report of the AAAAI’s Committee on the Underserved highlighted the increased reporting of inborn errors of immunity (IEI) in White compared to Black or Latinx patients though registries have not yet reported demographics in a diverse disease cohort of IEIs.10 In addition, under-recognition of immune defects and bronchiectasis in Black and Latinx patients have been reported even after correction for household income.21,22 Globally some genetically homogenous groups that practice consanguinity or endogamy have a higher prevalence of IEI.21 In the UK, rare diseases such as severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) are more frequent in Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Middle Eastern, and North African communities.23 Diagnosis of IEI requires access to specialized laboratory testing and clinical immunologists that are able to interpret immunologic and genetic testing. Timely primary care telemedicine referrals for laboratory or clinical red-flags could help address access to specialists in areas that are lacking specialized care in IEI.

Beyond diagnosis, hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT), a curative therapy for some IEIs, is significantly impacted by disparate access to unrelated donors in bone marrow donation registries.24 In 2014, the likelihood of finding an optimal donor was the highest among White individuals of European descent (75%), while the lowest probability was identified for those of African-American, Black African, Caribbean, and South or Central American descent (16–19%).24 Immunologists can aid in ensuring genetic counseling, medication management, and HSCT are equally considered for all patients including those from disadvantaged backgrounds. Improving the relationships between disadvantaged groups and the healthcare system through participatory empowerment, educational videos, and social media advertisements may help to improve registry diversity for use in HSCT.25–27

Health Disparities in COVID

Since the outset of the pandemic, COVID19 infection rates, morbidity, and mortality are consistently disproportionately higher for Black and Latinx communities.28 The distribution of COVID19 deaths in Black and American Indian and Alaskan Native persons outpaces the unweighted population distribution of the US. Due to this disparate outcome, much has been noted about the impact of SDoH on COVID19 exposure risk, infections, and mortality in these groups. Importantly, members of these communities throughout the pandemic have been more likely to be essential workers and less able to work remotely and social distance.

Multidimensional poverty, increased exposure, diminished access to care, enhanced morbidity from prevalent comorbid conditions, and lower vaccination rates worsened for disadvantaged communities during the COVID19 pandemic.29 Pre-pandemic, Black children with food allergy were significantly more likely to experience low food security compared with White children with food allergy. However, the relationship between household dietary restrictions and pandemic-related food insecurity was persistent in those with pre-existing food restrictions but similar across racial and ethnic subgroups during the pandemic.30

Intervention studies have aimed to reduce disparities in COVID19 vaccination uptake. By using a care gap alert in the EHR at the San Francisco Health Network, the unintended consequence of Black patients being offered COVID vaccines less often than the overall primary care population and lower vaccination rates in Black patients 65 years and older was observed.31 More successful multi-level interventions included staff huddles, providing “missed opportunity” reports to managers, and forming Vaccine Equity Committees with patient advisors to develop virtual training modules. Care gap analysis data was reviewed at multiple time points, and in clinics where disparities persisted, site visits, structured observations, and stakeholder interviews were conducted. This study reported an improvement in vaccine offer rates for Black patients, and subsequent increased vaccine uptake within the network.

Preparedness planning, community and policy infrastructure approaches, and tailored strategies are effective.32 These types of interventional studies emphasize the importance of involving the communities affected at all stages of planning and implementation to help address linguistic, cultural, and educational barriers that would impact successful implementation. Specific strategies to reach marginalized communities include the use of mobile clinics, engaging lay community health workers, and disseminating communication materials in partnership with trusted intermediaries such as lay promotoras, community organizations, and faith-based organizations. These studies should serve as a catalyst for ideas for providers who engage with high-risk communities related to COVID19 vaccinations and sequelae of COVID infection.

Gaps in Understanding of Disparate Outcomes Beyond Racial and Ethnic Disparities

Sex, Gender, and LGBTQI+ Individuals

Gender has been shown to impact behaviors by both the patient and their provider, with differential prevalence and outcomes based on biologic and social differences.33 Disparities based on gender exists throughout healthcare with women experiencing difficulty accessing timely healthcare, forgoing care, and being non-adherent to medications due to cost.34 Socioeconomic and environmental factors that differentially impact women in the US include decreased educational level, lower salary or income, and higher rates of psychosocial stress (exposures to domestic violence, trauma, and mental illness).35

LGBTQI+ individuals experience interpersonal discrimination in the form of slurs, microaggressions, sexual harassment, and violence, that negatively impacts the desire of LGBTQI+ individuals to access healthcare due to perceived or anticipated discrimination.36 Experiencing stigma, discrimination, and social exclusion may negatively impact the experience within the healthcare system overall, and by extension health outcomes specific to allergic and immunologic diseases.

Differences based on sex in asthma prevalence, morbidity, and mortality are widely recognized, but understanding of intersectional effects with sexual orientation are not.35,37 Transgender status has been associated with significantly higher prevalence of asthma; and gay or lesbian adolescent patients had higher rates of asthma disease burden, with the highest rates amongst White gay males and Black lesbian females.38 Careful understanding of culturally appropriate interactions is necessary to garner trust and ensure a positive health care experience for those identifying as LGBTQI+.39 Although no studies have assessed interventions related to gender identity, gender expression, and sexual orientation on health outcomes specific to allergic or immunologic diseases, it is well established that gender-affirming care can improve mental health outcome for transgender and non-binary individuals.40

Persons with Disabilities

Disability is a complex and dynamic state of being that exists on a continuum, extending from physical or anatomic differences (i.e. - blindness, deafness, or limb deficits) to mental or psycho-emotional impairments (cognitive impairments, intellectual disabilities, or severe psychiatric disorders). Beyond that, children with food allergies have an “invisible” disability (as defined under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 by the US Department of Education) and experience exclusion and bullying. Studies assessing healthcare disparities in persons with disabilities have highlighted differences in general disease prevalence (obesity, diabetes, preterm birth, malnutrition, substance abuse, HIV, and cardiovascular disease), morbidity (late disease diagnosis and lack of treatment), and mortality compared to those without disabilities.41–43 Because disabled persons are marginalized due to different experiences in how they navigate and experience work, schools, or health systems, care should be taken to ensure that the work or school environment and provider interactions respect a disabled person’s autonomy. Providers can support appropriate accommodations in schools for patients and assure ease of access to facilities for patients who are disabled. Further, interventional studies performed in general atopic diseases should aim to facilitate inclusion of individuals with disabilities and to study disparate outcomes related to allergic and immunologic disorders.

Language

Language barriers can result in differential outcomes for non-English speakers who seek care in the US. Language barriers can lead to poor satisfaction with the healthcare experience, and limit access to care which has both ethical and legal implications.44–45 Language barriers not only impact direct communication with care providers, but also play a role in health literacy and cultural health beliefs.6 There is a paucity of published studies aimed at advancing our understanding of how language barriers impact disparate outcomes within the field of Allergy-Immunology. Providing interpreter services and assuring written communication is appropriately translated may help mitigate some of the barriers to care.

Intersectionality

These above social categories that impact a patient’s ability to access healthcare, engage with health systems and providers, and obtain equitable healthcare interact through a theoretical public health framework termed intersectionality. Intersectionality is the multiple, interlocking social identities (e.g. race, gender, sexual orientation, or disability status) of an individual that determines their experiences at the social-structural level (e.g. racism, sexism, heterosexism, ableism).46–47 Belonging to multiple disadvantaged groups may further magnify disparities. Interventions that could help enhance health equity for the individual with grouped social identities include engaging in cultural competency education, and using treatment strategies that follow general guidelines, regardless of gender identity, sexual orientation, ability, or preferred language. Allergy-Immunology specialists should consider intersectionality in the patients they provide care for and engage with stakeholders to ensure the needs of their patients are appropriately met. Additionally, research is needed to capture these important demographic concepts, and explore how varied identities intersect and impact health

Structural Barriers to Care - Access, Community, and Physical Environment

Equitable Access to Care

Equitable access and coverage of medications is particularly important with the rise of novel targeted therapies. The majority of asthma biologic users are White, and according to a recent study have an annual income of at least $75,000/year.48 Black and Latinx individuals comprised 15% of total biologic users with commercial insurance (7.5% and 7.9% respectively), and 25% of those with Medicare (15.5% and 9.2% respectively). Higher income and access to specialists were associated with use of biologics, but race, ethnicity, and the overall biologic eligibility of the included population was not available. Despite Black and Latinx patients experiencing higher rates of disease morbidity and severity in atopic diseases, they appear to lack access to biologics. This may be the result of a combination of factors including cost, reduced access to subspecialists, and offer rates of biologics by providers.48

Research Participation by Underrepresented Groups

A recent study highlighted the overrepresentation of White participants in food allergy research and combined expertise from clinicians and researchers with feedback from advocates and patients to determine recommendations to address this issue.49 And, as stated previously in this manuscript, the need to enhance research participant diversity extends to other allergic and immunologic disorders. Beyond establishing community partnerships, enhancing recruitment efforts, and intentionally recruiting diverse investigators and research staff are important for increasing participation from racially underrepresented patient populations.10,49 Other specialties have reported on the use of community-based participatory research designs that incorporate the insights from community representatives from the target recruitment population.50–51 These insights may be helpful in mitigating issues related to mistrust and discrimination by ensuring that acceptable, patient-centered interventions, recruitment strategies, data collection, and trial designs are incorporated by investigators at the outset. Lastly, to assure that a study’s recruitment consists of a representative sample of those affected by the disease, deliberately recruiting an increased number of participants from underrepresented backgrounds may be needed to obtain generalizable data.

The Built Environment – Exposures and Mitigation Strategies

Exposures

As evident from a growing body of literature, early life exposures impact asthma prevalence and likely contribute to disparities in asthma incidence and morbidity. The Urban Environment and Childhood Asthma (URECA) study evaluated the effects of pre- and post-natal exposures to maternal stress and depression on respiratory phenotypes among racial and ethnic minority children residing in low-income, urban areas in the U.S.52 They found that maternal stress and depression were associated with wheezing and the number of wheezing illnesses. They also showed that exposure to household dust high in ergosterol and low in animal allergens conferred a risk for a high wheeze, high atopy, and low lung function phenotype. This highlights that “housing is health,” and is further supported by the link between poor housing conditions and disproportionate exposures to asthma triggers in low-income patients.53 These differences are, in part, the result of historical discriminatory practices such as redlining and predatory lending that constrained Black people to neighborhoods with older domestic and school buildings that are now in disrepair and house harmful asthma triggers.

Housing quality is measured by an affirmative response to three of seven conditions: (1) problems with pests such as rats, mice, or roaches, (2) leaking roof or ceiling, (3) windows with broken glass or that cannot be shut, (4) exposed electrical wires, (5) plumbing problems such as a toilet or hot water heater that does not work, (6) holes or cracks in the walls or ceiling and, (7) large holes in the floor.54 Researchers have found that homes of Black children with asthma were commonly impacted by pest infestations, plumbing leaks, and structural issues. However, these issues may not be exclusively linked to race, as shown by a 2021 study evaluating the spatial distribution of asthma-related emergency department visit incidence rates.55 The study found neighborhood-to-neighborhood variability in incidence rates not fully explained by race, ethnicity, poverty, or characteristics of the built environment. This study demonstrates the value of spatial analysis in grasping population-level trends and, like other recent studies using census data, shows that associations exist between neighborhood-level social vulnerability with asthma outcomes.56–58

Epidemiologic studies have also linked mold exposure in the home to asthma incidence and morbidity in childhood. Two recent studies further characterized this association. One found that home exposure to Mucor-containing dust was predictive of difficult-to-control asthma in a cohort of urban children.59 Homes with window air conditioning units were more likely to have higher Mucor levels. Another, using a new, patient-reported home environmental index, was able to assess environmental exposures and identified higher scores observed in Black residents as compared to White residents.60

Mitigation strategies

Current public health and regulatory practices are insufficient to correct historic discriminatory housing practices. Although it may be beyond the purview of Allergy-Immunology practitioners to identify safe housing for patients, at minimum, they should engage in dialogue that ensures a comprehensive approach to identifying exposures and disease-exacerbating triggers for patients. When appropriate, clinical advice for trigger remediation for sensitized patients should be provided. Collaboration with health organizations, insurers, private funding groups, and public health programs to advocate for rigorous studies to screen and treat maternal stress and depression are also important. Work to improve the home, school, or work environment of low-income, urban populations have been performed both recently and over the past decade and should continue.61–64 Further work in high-risk populations should advance our understanding of appropriate mitigation strategies and reasons for lack of effect in some studies should be further explored.

The Physician Workforce, Graduate Medical Education, and Training:

Underrepresented Persons in Medicine – Physician Workforce and Trainees

The need for specialists in Allergy-Immunology has increased over time, but the number of physicians in this field has not increased to meet this demand.65 As in other fields, the rates of specialists who identify as underrepresented in medicine (UIM) have also been stagnant over the past several decades.65 Lower numbers of providers from ethnically and culturally diverse backgrounds impact the ability to provide equitable, high quality health services to underserved Black and Latinx populations. Similarly, the number of UIMs applying to Allergy-Immunology fellowship training programs have declined from 2017–2021, with lower rates of UIM applicants in Allergy-Immunology as compared to other specialties.66

In addition to racial disparities, gender differences were also noted within Allergy-Immunology providers in a recent cross-sectional analysis.67 Male allergists were found to comprise 63.7% of the allergy faculty at academic institutions. and were substantially more likely to be full professors, first or last author on publications, and NIH-funded. However, when adjusted for factors that correspond to promotion (e.g. age, years since residency, faculty appointment at a “top 20” medical school, number of publications, NIH grants, clinical trial investigation, and Medicare reimbursement), the adjusted rate of full professorship status was similar, implying that with enhanced focus on recruitment, retention, and sponsorship, improved equity for faculty positions could be achieved.

Authors of a recent rostrum proposed several initiatives to help improve diversity in the trainee pipeline, medical education faculty, and the AAAAI.68 They suggested increasing the visibility of the specialty to prospective trainees early in their medical education, with a distinct effort made to recruit from historically Black medical schools and medical schools with the highest percentage of Black students. They recommended using bias reduction interventions to improve recruitment and retention of UIM faculty; funding programs that financially support or incentivize the training of UIM medical students, Allergy-Immunology fellows and faculty. The authors also endorsed outreach programs that engage with UIM and economically disadvantaged communities to explore topics and stoke interest in allergy-immunology. As is typical in other specialties, the use of education for managers, adoption of inclusive hiring practices, and fostering a work culture that values diversity and eliminates barriers to equal opportunity for UIMs is needed.69–75

Training in Health Disparities and Health Equity

It is important to make a concerted effort to better understand how patients’ social and lived environments affect accessibility and engagement with the healthcare system. The design and implementation of curricula for faculty and trainees to understand SDoH and reduce health disparities have been published.76 Interactive discussion-based sessions workshops may be effective for experiential learning. The curriculum incorporated guiding principles and an adaptable curriculum for learners covering topics such as racism and bias, economic and social context, advocacy and social justice, barriers to research participation, and environmental impact. Another recent report presents a framework for commitment to equity and anti-racism which was developed jointly by faculty, fellows, and residents.77 Attention to community outreach and workplace improvement with leadership commitment and financial support were highlighted. While these toolkits targeted academic institutions, they can be easily adapted for use by smaller institutions and groups of private practitioners.76,77

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Medical Journals

Medical journals play an essential role in medical education. Recognizing their importance, JACI, JACI: IP, and JACI: Global recently took a number of steps to improve discussion of Diversity Equity and Inclusion (DEI) in their Journal. They launched a health disparity case study feature, appointed a DEI coordinator, created a health disparities collection on the website, and updated guidelines for reporting race and ethnicity within the Journal. Several other journals have taken steps to improve representation and address issues related to DEI that have traditionally favored or provided advancements for non-minoritized racial groups, including JACI, NEJM, and JAMA. Although information about demographic details for authors are not typically recorded, a study reviewed and described the stagnant levels of authorship for UIMs in the NEJM and JAMA.78 Other high-impact journals have also been identified as lacking author and editorial diversity.79 Underpinning these trends is the lack of sponsorship and representation at the organizational and administrative levels within both journals and academia. This can be addressed by: creating and incentivizing efforts to recruit and retain members from underrepresented backgrounds in medicine and research; diversifying members on editorial and institutional boards; and enhancing sponsorship and mentorship for UIMs at every level of academia.80

Conclusion

This comprehensive report of varied topics in health disparities within allergy-immunology is not all-inclusive. There is much to learn about the barriers and mitigation strategies that impact how patients receive care, interact with providers, engage in research, and succeed in addressing their disease. Information on this topic within JACI and JACI: In Practice is currently incomplete, but by using examples from other fields on this topic, we were able to further expand our ability to highlight ways in which providers and researchers can effect change. In doing so, this report provides an important initial step forward in highlighting a framework (summarized in Figure 1) that addresses both upstream and downstream factors to address health disparities in allergy-immunology.

By including interventional studies from other fields and journals, we were able to more completely identify the issues related to health disparities in allergy-immunology and detail effective ways to address them. These disparities exist beyond the well-investigated areas of asthma and COVID into disease entities like atopic dermatitis, CVID, SCID, various immunodysregulatory conditions, and eosinophilic disorders. We should strive to advance our understanding of disparities and interventions in those spaces just as liberally. However, care must be taken when attempting to evaluate the “biology of racism” through avenues such as GWAS which sometimes makes use of comparators from disparate and distinct social and cultural groups. These out of context results may dissuade readers from the true origins of these differences – social and structural factors that have created differential socioeconomic conditions for our patients.

Further limitations with the application of GWAS and similar techniques in the context of disparities research exists and should be carefully examined. GWAS often generalizes findings from small, geographically limited samples, and associates genetic ancestry to health outcomes in heterogeneous populations (multiracial and multiethnic groups). Studies may not include environmental, geographic and social factors that may predispose to increased associations between certain groups and identified genetic variants. Lastly, beyond factors related to causality and biologic determinism, certain research approaches do not advance interventions with more immediate impact on the individual, community, and population health. Improved efforts to perform better-integrated investigational approaches using this method should be pursued.

Ultimately, this report highlights that we need a more concerted effort to fund and publish works that aim to both investigate the context of disparities in allergy-immunology diseases and identify ways in which we can move the needle forward towards providing equitable care (Figure 1 and Table 1). Additionally, we have identified avenues for change that are well within the purview and ability of all medical providers in allergy-immunology. It is only through a concerted effort from all involved parties – clinicians, researchers, administrators, insurers, legislators, public health officials, and members of the affected communities, that we can engage in this topic in a way that will yield results that truly begin to effect change, achieve health equity, and benefit us all.

Funding:

Funded in part by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergic and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health

Dr. Ogbogu receives research support from Blueprint Medical, GSK, and AstraZeneca. She is on the Advisory Board for GSK, AstraZeneca, Sanofi. She is a member of the Editorial Board of JACI Global. Dr. Apter is an associate editor of the Journal of Allergy & Clinical Immunology. The remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Abbreviations:

- AAAAI

American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology

- AR

Allergic Rhinitis

- COVID

SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus

- COVID19

Coronavirus Disease 2019

- DEI

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

- FA

Food Allergy

- FeNO

Fractional excretion of nitric oxide

- FEV1

Forced expiratory volume in 1 second

- FI

Food Insecurity

- GWAS

Genome-Wide Association Study

- HSCT

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant

- IEI

Inborn Errors of Immunity

- JACI

The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- JACI: IP

The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice

- LGBTQI+

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, queer/questioning, asexual and many other terms (such as non-binary and pansexual)

- MeSH

Medical Subject Headings

- NEJM

The New England Journal of Medicine

- NIH-

National Institutes of Health

- JAMA

The Journal of the American Medical Association

- SCID

Social Determinants of Health

- UIM

Underrepresented in medicine

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Redmond C, Akinoso-Imran AQ, Heaney LG, Sheikh A, Kee F, Busby J. Socioeconomic disparities in asthma health care utilization, exacerbations, and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;149(5):1617–1627. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Busby J, Heaney LG, Brown T, Chaudhuri R, Dennison P, Gore R, et al. Ethnic Differences in Severe Asthma Clinical Care and Outcomes: An Analysis of United Kingdom Primary and Specialist Care. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10(2):495–505.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.09.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cardet JC, Chang KL, Rooks BJ, Carroll JK, Celedón JC, Coyne-Beasley T, et al. Socioeconomic status associates with worse asthma morbidity among Black and Latinx adults [published online ahead of print, 2022 May 18]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;S0091–6749(22)00661–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2022.04.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sinaiko AD, Gaye M, Wu AC, Bambury E, Zhang F, Xu X, et al. Out-of-Pocket Spending for Asthma-Related Care Among Commercially Insured Patients, 2004–2016. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(12):4324–4331.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.07.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warren CM, Turner PJ, Chinthrajah RS, Gupta RS. Advancing Food Allergy Through Epidemiology: Understanding and Addressing Disparities in Food Allergy Management and Outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(1):110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.09.064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogbogu PU, Capers Q 4th, Apter AJ. Disparities in Asthma and Allergy Care: What Can We Do?. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(2):663–669. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.10.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shroba J, Das R, Bilaver L, Vincent E, Brown E, Polk B, et al. Food Insecurity in the Food Allergic Population: A Work Group Report of the AAAAI Adverse Reactions to Foods Committee. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10(1):81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.10.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esteban CA, Klein RB, Kopel SJ, McQuaid EL, Fritz GK, Seifer R, et al. Underdiagnosed and Undertreated Allergic Rhinitis in Urban School-Aged Children with Asthma. Pediatr Allergy Immunol Pulmonol. 2014;27(2):75–81. doi: 10.1089/ped.2014.0344, and pulmonology, 27(2), 75–81. 10.1089/ped.2014.0344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dykewicz MS, Wallace DV, Baroody F, Bernstein J, Craig T, Finegold I, et al. Treatment of seasonal allergic rhinitis: An evidence-based focused 2017 guideline update. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;119(6):489–511.e41. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2017.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis CM, Apter AJ, Casillas A, Foggs MB, Louisias M, Morris EC, et al. Health disparities in allergic and immunologic conditions in racial and ethnic underserved populations: A Work Group Report of the AAAAI Committee on the Underserved. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147(5):1579–1593. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.02.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stern J, Chen M, Fagnano M, Halterman JS. Allergic rhinitis co-morbidity on asthma outcomes in city school children [published online ahead of print, 2022 May 13]. J Asthma. 2022;1–7. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2022.2043363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neupert KB, Huntwork MP, Udemgba C, Carlson JC. Implementation of Stock Epinephrine in Chartered Versus Unchartered Public-School Districts. J Sch Health. 2022;92(8):812–814. doi: 10.1111/josh.13159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cykert S, Eng E, Walker P, Manning MA, Robertson LB, Arya R, et al. A system-based intervention to reduce Black-White disparities in the treatment of early stage lung cancer: A pragmatic trial at five cancer centers. Cancer Med. 2019;8(3):1095–1102. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gabryszewski SJ, Chang X, Dudley JW, Mentch F, March M, Holmes JH, et al. Unsupervised modeling and genome-wide association identify novel features of allergic march trajectories. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147(2):677–685.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.06.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akenroye AT, Brunetti T, Romero K, Daya M, Kanchan K, Shankar G, et al. Genome-wide association study of asthma, total IgE, and lung function in a cohort of Peruvian children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;148(6):1493–1504. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.02.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan Q, Forno E, Herrera-Luis E, Pino-Yanes M, Yang G, Oh S, et al. A genome-wide association study of asthma hospitalizations in adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147(3):933–940. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.08.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mersha TB, Qin K, Beck AF, Ding L, Huang B, Kahn RS. Genetic ancestry differences in pediatric asthma readmission are mediated by socioenvironmental factors [published correction appears in J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022 May;149(5):1818]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;148(5):1210–1218.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.05.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abuabara K, You Y, Margolis DJ, Hoffmann TJ, Risch N, Jorgenson E. Genetic ancestry does not explain increased atopic dermatitis susceptibility or worse disease control among African American subjects in 2 large US cohorts. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(1):192–198.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.06.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borrell LN, Elhawary JR, Fuentes-Afflick E, Witonsky J, Bhakta N, Wu AHB, et al. Race and Genetic Ancestry in Medicine - A Time for Reckoning with Racism. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(5):474–480. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms2029562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsui EC, Adamson AS, Peng RD. Time’s up to adopt a biopsychosocial model to address racial and ethnic disparities in asthma outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(6):2024–2025. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krishna MT, Hackett S, Bethune C, Fox AT. Achieving equitable management of allergic disorders and primary immunodeficiency in a Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic population. Clin Exp Allergy. 2020;50(8):880–883. doi: 10.1111/cea.13698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cunningham-Rundles C, Sidi P, Estrella L, Doucette J. Identifying undiagnosed primary immunodeficiency diseases in minority subjects by using computer sorting of diagnosis codes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113(4):747–755. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.01.761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wallace LJ, Ware MS, Cunningham-Rundles C, Fuleihan RL, Maglione PJ. Clinical disparity of primary antibody deficiency patients at a safety net hospital. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(7):2923–2925.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.03.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gragert L, Eapen M, Williams E, Freeman J, Spellman S, Baitty R, et al. HLA match likelihoods for hematopoietic stem-cell grafts in the U.S. registry. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(4):339–348. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1311707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Mara-Eves A, Brunton G, Oliver S, Kavanagh J, Jamal F, Thomas J. The effectiveness of community engagement in public health interventions for disadvantaged groups: a meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:129. Published 2015 Feb 12. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1352-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Molmenti EP, Finuf KD, Patel VH, Molmenti CL, Thornton D, Pekmezaris R. A Randomized Intervention to Assess the Effectiveness of an Educational Video on Organ Donation Intent. Kidney 360. 2021;2(10):1625–1632. Published 2021 Jul 28. doi: 10.34067/KID.0001392021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chu JN, Stewart SL, Gildengorin G, Wong C, Lam H, McPhee SJ, et al. Effect of a media intervention on hepatitis B screening among Vietnamese Americans. Ethn Health. 2022;27(2):361–374. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2019.1672862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ogbogu PU, Matsui EC, Apter AJ. COVID-19, health disparities, and what the allergist-immunologist can do. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;148(5):1172–1175. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.09.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Willems SJ, Castells MC, Baptist AP. The Magnification of Health Disparities During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10(4):903–908. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2022.01.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guillaume JD, Jagai JS, Makelarski JA, Abramsohn EM, Lindau ST, Verma R, et al. COVID-19-Related Food Insecurity Among Households with Dietary Restrictions: A National Survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(9):3323–3330.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.06.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gregory B, Franks A, Morales L, Rafferty H, Khoong E, George R, et al. System Interventions to Reduce Disparities in Covid-19 Vaccine Offer Rates. NEJM Catal. 2022;3(7). doi: 10.1056/CAT.22.0093 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steege AL, Baron S, Davis S, Torres-Kilgore J, Sweeney MH. Pandemic influenza and farmworkers: the effects of employment, social, and economic factors. Am J Public Health. 2009;99 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S308–S315. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.161091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mauvais-Jarvis F, Bairey Merz N, Barnes PJ, Brinton RD, Carrero JJ, DeMeo DL, et al. Sex and gender: modifiers of health, disease, and medicine [published correction appears in Lancet. 2020 Sep 5;396(10252):668]. Lancet. 2020;396(10250):565–582. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31561-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Daher M, Al Rifai M, Kherallah RY, Rodriguez F, Mahtta D, Michos ED, et al. Gender disparities in difficulty accessing healthcare and cost-related medication non-adherence: The CDC behavioral risk factor surveillance system (BRFSS) survey. Prev Med. 2021;153:106779. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DeBolt C, Harris D. The Impact of Social Determinants of Health on Gender Disparities Within Respiratory Medicine. Clin Chest Med. 2021;42(3):407–415. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2021.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Casey LS, Reisner SL, Findling MG, Blendon RJ, Benson JM, Sayde JM, et al. Discrimination in the United States: Experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer Americans. Health Serv Res. 2019;54 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):1454–1466. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang G-Q, Özuygur Ermis SS, Rådinger M, Bossios A, Kankaanranta H, Nwaru B. Sex disparities in asthma development and clinical outcomes: implications for treatment strategies. J Asthma Allergy. 2022;15:231–247. doi: 10.2147/JAA.S282667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Curry CW, Felt D, Kan K, Ruprecht M, Wang X, Phillips G 2nd,, et al. Asthma Remission Disparities Among US Youth by Sexual Identity and Race/Ethnicity, 2009–2017. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(9):3396–3406. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.04.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arroyo AC, Sanchez DA, Camargo CA Jr, Wickner PG, Foer D. Evaluation of Allergic Diseases in Transgender and Gender-Diverse Patients: A Case Study of Asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10(1):352–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.10.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tordoff DM, Wanta JW, Collin A, Stepney C, Inwards-Breland DJ, Ahrens K. Mental Health Outcomes in Transgender and Nonbinary Youths Receiving Gender-Affirming Care [published correction appears in JAMA Netw Open. 2022 Jul 1;5(7):e2229031]. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e220978. Published 2022 Feb 1. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakkeeran N, Nakkeeran B. Disability, mental health, sexual orientation and gender identity: understanding health inequity through experience and difference. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16(Suppl 1):97. Published 2018 Oct 9. doi: 10.1186/s12961-018-0366-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.The Lancet Public Health. Disability-a neglected issue in public health. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6(6):e346. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00109-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim HW, Shin DW, Yeob KE, Cho IY, Kim SY, Park SM, et al. Disparities in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Gastric Cancer in Relation to Disabilities [published correction appears in Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2021 Mar 10;12(3):e00322]. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2020;11(10):e00242. doi: 10.14309/ctg.0000000000000242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Espinoza J, Derrington S. How Should Clinicians Respond to Language Barriers That Exacerbate Health Inequity?. AMA J Ethics. 2021;23(2):E109–E116. Published 2021 Feb 1. doi: 10.1001/amajethics.2021.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Al Shamsi H, Almutairi AG, Al Mashrafi S, Al Kalbani T. Implications of Language Barriers for Healthcare: A Systematic Review. Oman Med J. 2020;35(2):e122. Published 2020 Apr 30. doi: 10.5001/omj.2020.40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alvidrez J, Greenwood GL, Johnson TL, Parker KL. Intersectionality in Public Health Research: A View From the National Institutes of Health. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(1):95–97. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Inselman JW, Jeffery MM, Maddux JT, Shah ND, Rank MA. Trends and disparities in asthma biologic use in the united states. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020. Feb;8(2):549–554.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Akenroye AT, Heyward J, Keet C, Alexander GC. Lower Use of Biologics for the Treatment of Asthma in Publicly Insured Individuals. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(11):3969–3976. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.01.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bilaver LA, Galic I, Zalavsky J, Anderson B, Catlin PA, Gupta RS. Achieving racial representation in food allergy research: a modified Delphi study [published online ahead of print, 2022 Oct 11]. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;S2213–2198(22)01037–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2022.09.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hurd TC, Kaplan CD, Cook ED, Chilton JA, Lytton JS, Hawk ET, et al. Building trust and diversity in patient-centered oncology clinical trials: An integrated model. Clin Trials. 2017;14(2):170–179. doi: 10.1177/1740774516688860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bonevski B, Randell M, Paul C, Chapman K, Twyman L, Bryant J, et al. Reaching the hard-to-reach: a systematic review of strategies for improving health and medical research with socially disadvantaged groups. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:42. Published 2014 Mar 25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ramratnam SK, Lockhart A, Visness CM, Calatroni A, Jackson DJ, Gergen PJ, et al. Maternal stress and depression are associated with respiratory phenotypes in urban children. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2021. 148(1):120–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bryant-Stephens TC, Strane D, Robinson EK, Bhambhani S, Kenyon CC. Housing and asthma disparities. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;148(5):1121–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.09.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Blake K, Kellerson R, Simic A. Measuring Overcrowding in Housing.U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Policy Development and Research 2007. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/publications/ahsrep/measuring_overcrowding.html

- 55.Zárate RA, Zigler C, Cubbin C, Matsui EC. Neighborhood-level variability in asthma-related emergency department visits in Central Texas. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021. Nov;148(5):1262–1269.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 56.Mutic AD, Mauger DT, Grunwell JR, Opolka C, Fitzpatrick AM. Social Vulnerability Is Associated with Poorer Outcomes in Preschool Children With Recurrent Wheezing Despite Standardized and Supervised Medical Care. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022. Apr;10(4):994–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grunwell JR, Opolka C, Mason C, Fitzpatrick AM. Geospatial Analysis of Social Determinants of Health Identifies Neighborhood Hot Spots Associated With Pediatric Intensive Care Use for Life-Threatening Asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022. Apr;10(4):981–991.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nardone A, Casey JA, Morello-Frosch R, Mujahid M, Balmes JR, Thakur N. Associations between historic residential redlining and current age-adjusted rates of emergency department visits due to asthma across eight cities in California: an ecological study. Lancet Planet Health. 2020. Jan;4(1):e24–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vesper S, Wymer L, Kroner J, Pongracic JA, Zoratti EM, Little FF, et al. Association of mold levels in urban children’s homes with difficult-to-control asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;149(4):1481–1485. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.07.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Juhn YJ, Beebe TJ, Finnie DM, Sloan J, Wheeler PH, Yawn B, et al. Development and initial testing of a new socioeconomic status measure based on housing data. J Urban Health. 2011;88(5):933–944. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9572-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grant TL, McCormack MC, Peng RD, Keet CA, Rule AM, Davis MF, et al. Comprehensive home environmental intervention did not reduce allergen concentrations or controller medication requirements among children in Baltimore [published online ahead of print, 2022 Jun 3]. J Asthma. 2022;1–10. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2022.2083634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Akar-Ghibril N, Sheehan WJ, Perzanowski M, Balcer-Whaley S, Newman M, Petty CR, et al. Predictors of successful mouse allergen reduction in inner-city homes of children with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(11):4159–4161.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.06.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vesper SJ, Wymer L, Coull BA, Koutrakis P, Cunningham A, Petty CR, et al. HEPA filtration intervention in classrooms may improve some students’ asthma [published online ahead of print, 2022 Apr 10]. J Asthma. 2022;1–8. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2022.2059672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Phipatanakul W, Koutrakis P, Coull BA, Petty CR, Gaffin JM, Sheehan WJ, et al. Effect of School Integrated Pest Management or Classroom Air Filter Purifiers on Asthma Symptoms in Students With Active Asthma: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2021;326(9):839–850. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.11559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marshall GD; American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology Workforce Committee. The status of US allergy/immunology physicians in the 21st century: a report from the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology Workforce Committee. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119(4):802–807. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.01.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.ERAS Statistics. American Medical Association. Updated October 5, 2022. Accessed October 23, 2022. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/interactive-data/eras-statistics-data

- 67.Blumenthal KG, Huebner EM, Banerji A, Long AA, Gross N, Kapoor N, et al. Sex differences in academic rank in allergy/immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144(6):1697–1702.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.06.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Carter MC, Saini SS, Davis CM. Diversity, Disparities, and the Allergy Immunology Pipeline. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10(4):923–928. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.12.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bhasin A, Musa A, Massoud L, Razikeen A, Noori A, Ghandour A, et al. Increasing Diversity in Cardiology: A Fellowship Director’s Perspective. Cureus. 2021. Jul 12;13(7):e16344. doi: 10.7759/cureus.16344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Beer J, Heningburg J, Downie J, Beer K. Diversity in Academic Dermatology. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022. Jun 1;21(6):674–676. doi: 10.36849/JDD.6899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cheng JL, Dibble EH, Baird GL, Gordon LL, Hyun H. Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Academic Nuclear Medicine: National Survey of Nuclear Medicine Residency Program Directors. J Nucl Med. 2021. Sep 1;62(9):1207–1213. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.120.260711. Epub 2021 Apr 23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Davenport D, Alvarez A, Natesan S, Caldwell MT, Gallegos M, Landry A, et al. Faculty Recruitment, Retention, and Representation in Leadership: An Evidence-Based Guide to Best Practices for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion from the Council of Residency Directors in Emergency Medicine. West J Emerg Med. 2022;23(1):62–71. Published 2022 Jan 3. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2021.8.53754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Robinett K, Kareem R, Reavis K, Quezada S. A multi-pronged, antiracist approach to optimize equity in medical school admissions. Med Educ. 2021. Dec;55(12):1376–1382. doi: 10.1111/medu.14589. Epub 2021 Jul 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Griffin K, Bennett J, York T. Leveraging Promising Practices: Improving the Recruitment, Hiring, and Retention of Diverse & Inclusive Faculty. doi: 10.31219/osf.io/dq4rw [DOI]

- 75.University Health Services, University of California, Berkeley. A Toolkit for Recruiting and Hiring a More Diverse Workforce. April 2013. Available at: https://diversity.berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/recruiting_a_more_diverse_workforce_uhs.pdf

- 76.Udemgba C, Jefferson AA, Stern J, Khoury P. Toolkit for Developing Structural Competency in Health Disparities in Allergy and Immunology Training and Research. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10(4):936–949. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2022.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chesley C, Lee JT, Clancy CB. A Framework for Commitment to Social Justice and Antiracism in Academic Medicine. ATS Sch. 2021;2(2):159–162. Published 2021 Mar 12. doi: 10.34197/ats-scholar.2020-0149CM [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Abdalla M, Abdalla M, Abdalla S, Saad M, Jones DS, Podolsky SH. The Under-representation and Stagnation of Female, Black, and Hispanic Authorship in the Journal of the American Medical Association and the New England Journal of Medicine [published online ahead of print, 2022 Mar 21]. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2022;1–10. doi: 10.1007/s40615-022-01280-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Else H, Perkel JM. The giant plan to track diversity in research journals. Nature. 2022;602(7898):566–570. doi: 10.1038/d41586-022-00426-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fadeyi OO, Heffern MC, Johnson SS, Townsend SD. What Comes Next? Simple Practices to Improve Diversity in Science. ACS Cent Sci. 2020. Aug 26;6(8):1231–1240. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.0c00905. Epub 2020 Aug 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]