Abstract

Background

Rising opioid-related death rates have prompted reductions of opioid prescribing, yet limited data exist on population-level associations between opioid prescribing and opioid-related deaths.

Objective

To evaluate population-level associations between five opioid prescribing measures and opioid-related deaths.

Design

An ecological panel analysis was performed using linear regression models with year and commuting zone fixed effects.

Participants

People ≥10 years aggregated into 886 commuting zones, which are geographic regions collectively comprising the entire USA.

Main Measures

Annual opioid prescriptions were measured with IQVIA Real World Longitudinal Prescription Data including 76.5% (2009) to 90.0% (2017) of US prescriptions. Prescription measures included opioid prescriptions per capita, percent of population with ≥1 opioid prescription, percent with high-dose prescription, percent with long-term prescription, and percent with opioid prescriptions from ≥3 prescribers. Outcomes were age- and sex-standardized associations of change in opioid prescriptions with change in deaths involving any opioids, synthetics other than methadone, heroin but not synthetics or methadone, and prescription opioids, but not other opioids.

Key Results

Change in total regional opioid-related deaths was positively correlated with change in regional opioid prescriptions per capita (β=.110, p<.001), percent with ≥1 opioid prescription (β=.100, p=.001), and percent with high-dose prescription (β=.081, p<.001). Change in total regional deaths involving prescription opioids was positively correlated with change in all five opioid prescribing measures. Conversely, change in total regional deaths involving synthetic opioids was negatively correlated with change in percent with long-term opioid prescriptions and percent with ≥3 prescribers, but not for persons ≥45 years. Change in total regional deaths in heroin was not associated with change in any prescription measure.

Conclusions

Regional decreases in opioid prescriptions were associated with declines in overdose deaths involving prescription opioids, but were also associated with increases in deaths involving synthetic opioids (primarily fentanyl). Individual-level inferences are limited by the ecological nature of the analysis.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-022-07686-z.

The USA is in the midst of an unprecedented increase in deaths involving opioids. Between 1999 and 2020, annual opioid-related deaths increased from 8,050 to 68,630.1 Concern that lax opioid prescribing contributes to fatal1 and non-fatal2 overdoses stimulated several policies to rein in opioid prescriptions3–9 that were followed by a decline in opioid prescribing.10 Yet overall opioid-related deaths have continued to increase, driven primarily by deaths involving heroin and synthetic opioids other than methadone,11 which frequently include illicit fentanyl.12, 13

With declines in opioid prescribing, concerns have developed that overly restrictive opioid prescribing policies might unintentionally increase overdose risks from illicitly obtained opioids.14–16 By encouraging opioid tapering and discontinuation in stable patients with chronic pain, strong prescription control policies may lead some individuals to manage their pain or ward off cravings with illicit opioids.14 Stopping long-term prescribed opioids has been connected to increased risks of heroin use,17 non-fatal overdoses,18 and fatal19, 20 overdoses. Questions exist over whether strong policy measures to reduce the opioid prescription supply21 are effective population-level strategies to lower opioid-related deaths.14–16

Prior research on associations between regional opioid prescribing practices and overdose mortality has yielded mostly positive correlations22–24 with one report of a weakly significant negative correlation.25 Research on associations between regional prescribing of specific opioids and overdose deaths has found significant correlations for some opioids, but not others.24, 26–28 Although these associations, which involve correlations across geographic regions, are informative, they are vulnerable to confounding by regional variation in socioeconomic conditions, which are strongly related to opioid prescribing and overdose mortality.29

We first describe regional changes in national opioid prescribing and opioid-related mortality. We then use fixed effect models in which geographic regions serve as their own controls to evaluate changes in regional opioid prescribing in relation to changes in opioid-related overdose deaths. This design takes advantage of geographic variation in opioid prescribing and mortality trends and controls for characteristics, such as regional socioeconomic deprivation level or number of substance use treatment facilities, which tend to remain fairly constant. We considered associations between five opioid prescribing measures and total opioid-related deaths, deaths involving synthetic opioids (primarily fentanyl), heroin, and prescription opioids. We hypothesized that regions with the greater than average declines in opioid prescriptions would have greater than average declines in overdose deaths involving prescription opioids, while they would also have the greater than average increases in overdose deaths involving illicit opioids.

METHODS

Sources of Data

Opioid-related mortality was measured with 2009–2017 Multiple Cause of Death Research files (All Counties).30 These files contain information on age, sex, race, ethnicity, county and state of occurrence, and cause of death of all US deaths. To control for differences in age and sex composition between populations by age, sex, and year, we calculated age- and sex-standardized associations of changes in regional opioid-related prescribing with opioid-related mortality using direct standardization with 2009 as the standard population.

Opioid prescriptions were measured with the IQVIA Real World Data: Longitudinal Prescription Data (LRx) dataset (January 2009 to December 2017), excluding buprenorphine formulations approved for opioid addiction. The LRx is a longitudinal prescription database from retail and non-retail pharmacies for individuals followed across years, pharmacies, and payment sources. The estimated covered proportion of the US population increased from 76.5% in 2009 to 90.0% in 2017.

For geographic aggregation, we used states and commuting zones (n=886) as defined by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.31 Commuting zones, which are based on journey-to-work data, are county clusters with strong commuting ties. Commuting zones (hereafter regions) including counties from multiple states were partitioned into single-state components. US Census Bureau data were used to derive regional population-based rates of the opioid prescribing and opioid-related mortality measures.

Opioid Prescribing Measures

Five opioid prescription measures were calculated for each study year and region. The first metric, which is used by the CDC to communicate national opioid prescribing trends,10 was the number of filled opioid prescriptions per capita. Because the volume of opioid prescribing is unevenly distributed among patients,32 we also included annual percent with ≥1 prescription. In order to evaluate whether quality of care metrics33 track more closely with opioid-related mortality, we also considered percent with ≥1 prescription with a daily dose of >120 mg morphine equivalents (high-dose opioid prescriptions) that has been associated with increased risks of overdose deaths.34 Because length of opioid prescribing is strongly associated with persistent opioid use,35 we included a measure of percent with opioid prescriptions for ≥60 consecutive days (long-term opioid prescriptions). Finally, because of an association between multiple opioid prescribers and opioid overdose risk,36 we defined a multiple prescriber measure as percent with ≥3 different opioid prescribers during a year.

Opioid Mortality

Drug overdose deaths involving opioids of persons aged ≥10 years were identified in multiple cause-of-death mortality data using ICD-10-CM codes for drug overdoses (X40–44, X60–64, Y10–Y14) excluding homicide (X85–X90). Among deaths with drug overdose as the underlying cause, those involving opioids were identified including ICD-10-CM multiple cause-of-death codes following CDC categories37 as total opioid-related deaths (T40.0–T40.4, T40.6) and separately as a hierarchy of those involving [1] synthetic opioids other than methadone (T40.4), [2] heroin (T40.1), [3] prescription opioids (T40.2 and T40.3), and [4] other opioids (T40.0 and T40.6). Because applying this hierarchy resulted in the first three groups absorbing all deaths in the “other opioids” group, three mutually exclusive subgroups were retained: deaths involving synthetic opioids, heroin (but not synthetics), and prescription opioids (but not synthetics or opioids).

Analytic Strategy

First, we calculated population-weighted regional rates per 100 persons in 2009 and 2017 of the 5 opioid prescribing measures for the total sample, 4 age groups (10–24, 25–44, 45-64, ≥65 years), and males and females. Year (2009–2017) differences were calculated with associated 95% confidence intervals. Similar procedures were followed to calculate total regional annual opioid-related death rates per 100,000 persons and for opioid-related deaths involving synthetic opioids, heroin, and prescription opioids. Second, maps were generated for 2009 and 2017 by applying 2009 distributions and creating quintiles for regional rates of total opioid-related deaths, deaths involving synthetic opioids, heroin, and prescription opioids per 100,000 persons. Similar procedures were followed for the five regional opioid prescription measures. Third, data from all nine years (2009–2017) were used and linear regression estimates were calculated using z-scored values of prescribing and mortality variables so that coefficients represent the effect of a one standard deviation change in the prescribing variable on standard deviation units of mortality. Z-scores were calculated using means and standard deviations specific to each group by age and sex. These values were pooled in analyses of the whole population. In all models, year and state/commuting zone fixed effects were included so that estimates reflect temporal changes in prescribing within commuting zones. In pooled models, sex and age group controls were included. Confidence intervals were corrected to account for heteroskedasticity caused by correlation of error terms across observations from the same region.38 Analyses were weighted by commuting zone population. To protect from type 1 error, the Bonferroni correction of alpha .05 was applied to each block of 7 age and sex linear regression analyses (p<.0071), conceiving each block as an independent evaluation. The analyses were performed with Stata v17.0.

All data were de-identified and exempted from consent by the Institutional Review Board of the New York State Psychiatric Institute University.

RESULTS

Trends in Opioid Prescribing

All five opioid measures declined during the 2009 to 2017 study period. Regional opioid prescription per capita declined from 70.19 to 61.63; percent with ≥1 opioid prescription from 26.40 in 2009 to 20.27 in 2017; percent filling high-dose prescriptions from 2.01 to 1.60; percent filling long-term prescriptions from 1.24 to 0.96; and percent filling prescriptions from ≥3 prescribers from 3.18 to 2.26 (Table S1, Figures S1–S3).

Total Opioid-Related Deaths

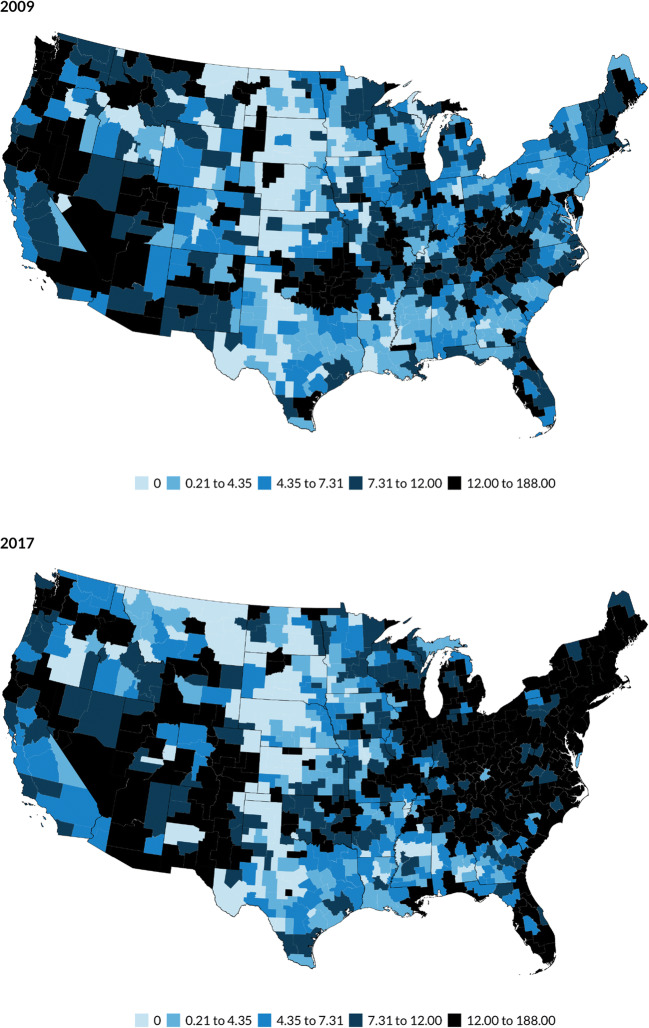

Between 2009 and 2017, total regional opioid-related deaths per 100,000 persons increased from 7.94 to 17.21 (difference, 95%CI: 9.27, 8.34 to 10.20) (Table S2). Opioid-related deaths increased in several regions, especially those within Northeastern and South Central states (Fig. 1). Change in total regional opioid-related deaths was positively associated with change in regional opioid prescriptions per capita, percent with ≥1 opioid prescription, and percent with high-dose opioid prescription (Table 1). Significant corresponding associations were also observed among males and females, except for change in percent with ≥1 opioid prescription among males (β=.104, p=.012). Among the two older age groups, change in total regional opioid-related deaths was significantly and positively correlated with change in all five opioid prescribing measures.

Fig. 1.

Total opioid-related deaths per 100,000 persons by quintiles in 882 commuting zones, USA 2009 and 2017.

Table 1.

Associations of Regional Change in Prescription Opioid Use Measures with Total Opioid-Related Mortality by Age Group and Sex

| Opioid prescriptions per capita | Percent with ≥1 opioid prescription | Percent with high-dose prescription | Percent with long-term prescription | Percent with ≥3 prescribers | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | |

| Total | 0.110 | <.001 | 0.100 | 0.001 | 0.081 | <.001 | 0.060 | 0.014 | 0.059 | 0.020 |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Male | 0.108 | 0.005 | 0.104 | 0.012 | 0.066 | 0.006 | 0.048 | 0.127 | 0.043 | 0.221 |

| Female | 0.085 | 0.001 | 0.080 | 0.002 | 0.084 | <.001 | 0.053 | 0.021 | 0.045 | 0.043 |

| Age, years | ||||||||||

| 10–24 | 0.049 | 0.097 | 0.057 | 0.072 | 0.045 | 0.066 | 0.040 | 0.131 | −0.038 | 0.214 |

| 25–44 | 0.043 | 0.338 | 0.043 | 0.337 | 0.027 | 0.503 | −0.012 | 0.778 | −0.056 | 0.206 |

| 45–64 | 0.179 | <.001 | 0.136 | <.001 | 0.184 | <.001 | 0.145 | <.001 | 0.127 | 0.001 |

| 65+ | 0.047 | <.001 | 0.040 | 0.001 | 0.058 | <.001 | 0.042 | 0.001 | 0.047 | <.001 |

Opioid-related deaths were defined as deaths with an underlying ICD-10-CM cause of overdose (X40–44, X60–64, or Y10–Y14) and that involved opioids (T40.0–T40.4, T40.6)

Deaths Involving Synthetic Opioids

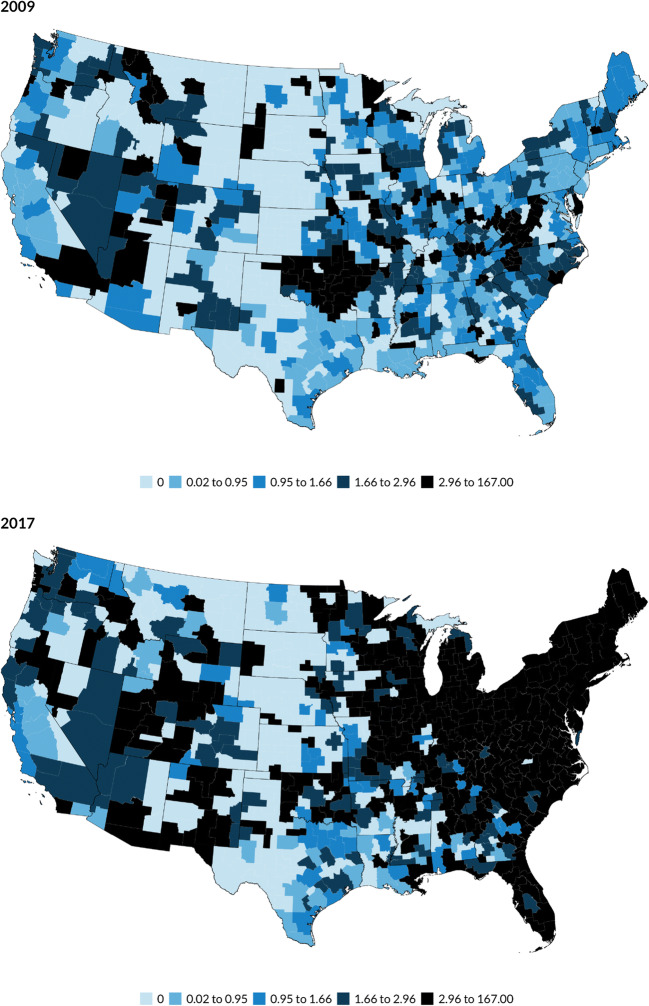

Total deaths involving synthetic opioids per 100,000 persons increased from 1.14 to 10.31 (difference, 95%CI: 9.17, 8.38 to 9.95). The maps reveal particularly large increases in regions within New England, Mid-Atlantic, South Atlantic, and East North Central states (Fig. 2). Change in total regional deaths involving synthetic opioids was negatively associated with change in percent with long-term opioid prescription and with percent with ≥3 prescribers (Table 2). Among males and females as well as among persons aged 10 to 24 years and 25 to 44 years, corresponding negative associations were also observed between change in regional deaths involving synthetic opioids and change in these two opioid prescribing measures. For adults aged 25 to 44 years, there was also a significant association between change in deaths involving synthetic opioids and change in percent with high-dose opioid prescription.

Fig. 2.

Overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids per 100,000 persons by quintiles in 882 commuting zones, USA 2009 and 2017.

Table 2.

Associations of Regional Change in Prescription Opioid Use Measures with Deaths Involving Synthetic Opioids by Age Group and Sex

| Opioid prescriptions per capita | Percent with ≥1 opioid prescription | Percent with high-dose prescription | Percent with long-term prescription | Percent with ≥3 prescribers | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | |

| Total | −0.047 | 0.249 | −0.049 | 0.271 | −0.040 | 0.077 | −0.081 | 0.004 | −0.114 | 0.002 |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Male | −0.075 | 0.149 | −0.080 | 0.168 | −0.063 | 0.028 | −0.109 | 0.002 | −0.157 | 0.002 |

| Female | −0.047 | 0.183 | −0.038 | 0.310 | −0.032 | 0.147 | −0.082 | 0.004 | −0.103 | 0.001 |

| Age, years | ||||||||||

| 10–24 | −0.112 | 0.015 | −0.109 | 0.030 | −0.043 | 0.120 | −0.084 | 0.005 | −0.250 | <0.001 |

| 25–44 | −0.147 | 0.016 | −0.140 | 0.023 | −0.134 | 0.005 | −0.177 | <0.001 | −0.287 | <0.001 |

| 45–64 | 0.033 | 0.623 | −0.013 | 0.830 | 0.030 | 0.617 | −0.021 | 0.712 | −0.050 | 0.435 |

| 65+ | 0.008 | 0.511 | 0.003 | 0.841 | 0.018 | 0.101 | 0.007 | 0.564 | −0.003 | 0.813 |

Deaths involving synthetic opioids were defined as deaths with an underlying ICD-10-CM cause of overdose (X40–44, X60–64, or Y10–Y14) and that involved synthetic opioids other than methadone (T40.4)

Deaths Involving Heroin

Regional rates of deaths involving heroin per 100,000 persons increased from 1.27 to 2.68 (difference, 95%CI: 1.41, 1.25 to 1.57) (Figure S4). None of opioid prescribing measures was significantly correlated with total deaths involving heroin (Table 3). For persons aged ≥65 years, however, change in regional deaths involving heroin was negatively associated with change in opioid prescriptions per capita, percent with ≥1 opioid prescription, percent with high-dose opioid prescription, and percent with long-term opioid prescription.

Table 3.

Associations of Regional Change in Prescription Opioid Use Measures with Deaths Involving Heroin by Age Group and Sex

| Opioid prescriptions per capita | Percent with ≥1 opioid prescription | Percent with high-dose prescription | Percent with long-term prescription | Percent with ≥3 prescribers | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | |

| Total | 0.060 | 0.038 | 0.057 | 0.056 | 0.020 | 0.157 | 0.005 | 0.830 | 0.047 | 0.038 |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Male | 0.081 | 0.018 | 0.081 | 0.022 | 0.026 | 0.103 | 0.009 | 0.705 | 0.062 | 0.018 |

| Female | 0.027 | 0.311 | 0.025 | 0.363 | 0.012 | 0.450 | −0.008 | 0.719 | 0.017 | 0.422 |

| Age, years | ||||||||||

| 10–24 | 0.037 | 0.123 | 0.050 | 0.051 | −0.010 | 0.485 | 0.009 | 0.654 | −0.022 | 0.377 |

| 25–44 | 0.014 | 0.669 | 0.023 | 0.489 | −0.012 | 0.597 | −0.033 | 0.204 | −0.024 | 0.384 |

| 45–64 | 0.010 | 0.814 | 0.008 | 0.818 | 0.013 | 0.715 | −0.009 | 0.803 | 0.009 | 0.781 |

| 65+ | −0.121 | <.001 | −0.092 | 0.005 | −0.101 | <.001 | −0.115 | <.001 | −0.088 | 0.011 |

Deaths involving heroin were defined as deaths with an underlying ICD-10-CM cause of overdose (X40–44, X60–64, or Y10–Y14) and that involved heroin (T40.1), but did not involve synthetic opioids other than methadone (T40.4)

Deaths Involving Prescription Opioids

Deaths involving prescription opioids decreased from 5.62 to 4.22 (difference, 95%CI: −1.31, −1.61 to −1.00) (Figure S5). In the total population and among males and females and each of age group, change in deaths involving prescription opioids was positively correlated with change in all five opioid prescribing measures (Table 4).

Table 4.

Associations of Regional Change in Prescription Opioid Use Measures with Deaths Involving Prescription Opioids by Age Group and Sex

| Opioid prescriptions per capita | Percent with ≥1 opioid prescription | Percent with high-dose prescription | Percent with long-term prescription | Percent with ≥3 prescribers | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | |

| Total | 0.199 | <.001 | 0.185 | <.001 | 0.162 | <.001 | 0.173 | <.001 | 0.192 | <.001 |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Male | 0.227 | <.001 | 0.220 | <.001 | 0.167 | <.001 | 0.192 | <.001 | 0.213 | <.001 |

| Female | 0.161 | <.001 | 0.147 | <.001 | 0.151 | <.001 | 0.153 | <.001 | 0.162 | <.001 |

| Age, years | ||||||||||

| 10–24 | 0.121 | <.001 | 0.124 | <.001 | 0.094 | <.001 | 0.103 | <.001 | 0.128 | <.001 |

| 25–44 | 0.226 | <.001 | 0.214 | <.001 | 0.203 | <.001 | 0.188 | <.001 | 0.222 | <.001 |

| 45–64 | 0.210 | <.001 | 0.180 | <.001 | 0.217 | <.001 | 0.213 | <.001 | 0.185 | <.001 |

| 65+ | 0.062 | <.001 | 0.055 | <.001 | 0.064 | <.001 | 0.055 | <.001 | 0.065 | <.001 |

Deaths involving prescription opioids were defined as deaths with an underlying ICD-10-CM cause of overdose (X40–44, X60–64, or Y10–Y14) and that involved prescription opioids (T40.2, T40.3), but did not involve synthetic opioids other than methadone (T40.4) or heroin (T40.1)

DISCUSSION

Across the USA, substantial spatial and temporal variations exist in opioid prescribing and opioid-related deaths. In accord with prior cross-sectional Canadian research,22,23 we report positive associations over time between regional opioid prescribing and opioid-related deaths, especially for deaths involving prescription opioids. However, there were also significant negative associations of changes in long-term opioid prescribing and multiple opioid prescribers with deaths involving synthetic opioids (primarily fentanyl). Although the results were generally similar for males and females, there were significant differences across age groups. Among adults 25 to 44 years of age, regional decreases in high-dose prescriptions, long-term prescriptions, and 3 or more opioid prescribers were linked to increased regional risks of deaths involving synthetic opioids.

The findings suggest that declining opioid prescribing practices, which may have occurred as a result of restrictive opioid prescribing policies, might have inadvertently increased overdose risks among young adults with illicitly obtained synthetic opioids. To mitigate these risks, care should be taken to closely monitor patients during opioid tapers and short opioid tapers should be avoided.39, 40 It may also be helpful to refer chronic pain patients to pain medicine specialists to optimize non-pharmacological pain management41 and refer high-risk patients to opioid treatment programs.42 Beyond clinical reforms in chronic pain management, vigorous public health strategies may be needed to expand access to buprenorphine and other medications for individuals with opioid use disorder. Such measures might help to offset effects of declining availability of illicit opioid pills from driving opioid-dependent individuals to use more dangerous illicit synthetic opioids. Office-based collaborative care opioid treatment program within community health centers is one well-developed but underfinanced model for expanding access to opioid use disorder treatment.43

The findings underscore the role of patient age in opioid surveillance including the vulnerability of younger adults to death involving illicit opioids. For adults aged 25 to 44 years, there were negative associations between change in opioid prescribing and deaths involving synthetic opioids such as fentanyl for long-term prescriptions and three or more opioid prescribers. This vulnerability may be related to the high prevalence of opioid use disorder among young people44 and increased risks of overdose following discontinuation of long-term prescribed opioids18–20 or indirect effects via declining diversion of prescription opioids on young people with opioid dependence. These results highlight the need for increasing access of young adults to medications for opioid use disorder. In older adults, who have a relatively high prevalence of chronic pain45 and in whom a large percentage of opioid-related deaths involve prescription opioids (Table S2), changes in all five opioid measures were directly related totally to changes in total opioid-involved deaths.

In the general population, the rate of overdose deaths involving heroin or synthetic opioids is nearly three times higher in males than in females (Table S1).37 As compared with women with opioid use disorder, men are less likely to have first obtained opioids via a legitimate opioid prescription.46 Nevertheless, there were few differences between males and females in population-level associations between opioid prescribing and opioid-related deaths. For both sexes, population-level decline in opioid prescribing was associated with lower population risk of overdoses involving prescription opioids and greater risks of overdoses involving synthetic opioids such as fentanyl.

Our results support distinguishing opioid-related deaths involving prescriptions and non-prescribed illicit opioids in local opioid prescription surveillance. Yet these ecological-level analyses do not permit inferences concerning clinical pathways connecting prescribing to individual deaths and call for corresponding person-level research. For example, we cannot distinguish overdose risks to individual patients that directly flow from prescribed opioids22, 47 from community overdose risks that are indirectly related via illicit opioid prescription diversion to someone other than the patient.48 Diversion of prescribed opioids might help to explain negative regional correlations of the percentage of people with ≥3 opioid prescribers with deaths involving synthetic opioids. Clinical cohort49 and case control50 research has demonstrated that patients filling opioid prescriptions from multiple providers are at increased risk of opioid overdose death. However, these studies did not distinguish deaths involving illicit opioids or capture possible indirect potential adverse community-wide effects posed by local shortages or disruptions in the illicit supply of diverted opioid pills that might follow decreases in these opioid prescribing measures and could lead to use of riskier illicit opioids. In our analyses, it was also not possible to distinguish potential risks following abrupt discontinuation of opioid therapy from risks of withholding opioid therapy from patients with intolerable pain.

In evaluating local prescribing practices, each prescribing measure was robustly associated with deaths involving prescription opioids. However, the measures varied in their correlation with changes in deaths involving synthetic opioids. For regional changes in this important cause of opioid-related death, there were negative associations with long-term opioid prescribing and 3 or more opioid prescribers, but not with changes in opioid prescriptions per capita, which is the standard metric used by the CDC. This suggests that there may be a role for tracking regional changes in opioid prescribing with a range of metrics.

This study has several limitations. First, this observational study cannot establish cause and effect. Because of potential confounding by time-varying factors, we cannot infer that local changes in opioid prescribing caused coincident changes in opioid-related mortality. Second, there was an increase in post mortem toxicological screening that may have contributed to improved classification of opioid-related deaths in later years.51 Third, the IQVIA database does not capture prescriptions filled at non-participating pharmacies and the representativeness of participating pharmacies is unknown, while the mortality data misclassifies location of deaths that are recorded outside of the decedent’s region of residence. Fourth, while this ecological analysis informs opioid prescription surveillance policy at a regional level, it does not identify mechanisms of individual risk. Datasets that link individual prescribing to individual mortality are needed to separate direct overdose risks among patients prescribed opioids from indirect regional risks related to illicit diversion of prescribed opioids or other changes in the illicit opioid landscape. Fifth, the analyses do not probe policy changes during the study period, such as the CDC guidelines for opioid management of chronic pain,3 prior authorization policies,4 prescription drug monitoring programs,52 and the Affordable Care Act,53 that may have influenced opioid prescriptions. Finally, because the opioid crisis has evolved towards being more closely related to illicit heroin and fentanyl,54 results from 2009 to 2017 may not directly apply to contemporary conditions.

Opioid prescribing patterns assume complex though discernible relationships with opioid-related deaths. Although research has examined intended and unintended effects of opioid policies,55 national relationships of regional opioid prescribing to opioid-related deaths have not previously been examined. Depending upon how it is achieved, limiting the supply of opioid prescriptions could have both positive and negative effects on opioid-related mortality. Great caution should be taken in tapering or discontinuing long-term opioids and close connections should be established between pain management services and opioid treatment programs. Yet it would be naïve to assume that narrowly focusing on opioid prescription practices will stem the rising tide of US opioid-related deaths without also addressing underlying social determinants of health,56 increasing access to medications for opioid use disorder,57 and expanding naloxone availability.58 It is further important to bear in mind that a great majority of people prescribed opioids do not experience difficulties with these medications.59 Nevertheless, many people who experience opioid harms were initially exposed to them via a prescription.60, 61

Supplementary information

(PDF 7001 kb)

(DOCX 54 kb)

Acknowledgements

Dr. Waidmann had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding

This work is supported by NIDA R01DA044981 (Marissa King, PI).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this article are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the United States Government.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.National Institute on Drug Abuse, Overdose death rates. https://www.drugabuse.gov/drug-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates

- 2.Vivolo-Kantor AM, Seth P, Gladden RM, et al. Vital signs: trends in emergency department visits for suspected opioid overdoses—United States, July 2016–September 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(9):279–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(1):1–49. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Hartung DM, Kim H, Ahmed SM, et al. Effect of high dosage opioid prior authorization policy on prescription opioid use, misuse, and overdose outcomes. Subst Abuse 2017;39(2):239-246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Schuchat A, Houry D, Guy GP Jr. New data on opioid use and prescribing in the United States. JAMA 2017;318(5):425-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Lin LA, Bohnert ASB, Kerns RD, Clay MA, Ganoczy D, Ilgen MA. Impact of the Opioid Safety Initiative on opioid-related prescribing in veterans. Pain. 2017;158(5):833–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Interactive Training Series, Applying CDC’s Guideline for Prescribing Opioids, An Online Training series for Healthcare Providers. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/training/online-training.html

- 8.Beaudoin FL, Janicki A, Zhai W, Choo EK. Trends in opioid prescribing before and after implementation of an emergency department opioid prescribing policy. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(2):329-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Raji MA, Kuo YF, Adhikari D, et al. Decline in opioid prescribing after federal rescheduling of hydrocodone products. Pharmacoepi Drug Safety 2018;27(5):513-519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Opioid overdose, US opioid dispensing rate maps. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/maps/rxrate-maps.html

- 11.Mattson CL, Tanz LJ, Quinn K, et al. Trends and geographic patterns in drug and synthetic opioid overdose deaths—United States, 2013-2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021; 70(6):202-207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Gladden RM, Martinez P, Seth P. Fentanyl law enforcement submissions and increases in synthetic opioid-involved overdose deaths – 27 states, 2013-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65 (33): 837-843. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Jones CM, Einstein EB, Compton WM. Changes in synthetic opioid involvement in drug overdose deaths in the United States, 2010-2016. JAMA 2018;319(17):1819-1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Mueller SR, Glanz JM, Nguyen AP, et al. Restrictive opioid prescribing policies and evolving risk environments: a qualitative study of the perspectives of patients who experienced an accidental opioid overdose. Int J Drug Policy. 92(2021) 103077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Rich RL, Prescribing opioids for chronic pain: unintended consequences of the 2016 CDC guideline. Am Family Phys. 2020;101(8):458-459. [PubMed]

- 16.Kertesz SG, Gordon AJ. A crisis of opioids and the limits of prescription control: United States. Addiction 2019;114(1):169-180. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Binswanger IA, Glanz JM, Faul M, et al. The association between opioid discontinuation and heroin use: a nested case-control study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;217:109248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Agnoli A, Zing G, Tancredi DJ, et al. Association of dose tapering with overdose or mental health crisis among patients prescribed long-term opioids. JAMA. 2021;326(5):411-419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.James JR, Scott JM, Klein JW, et al. Mortality after discontinuation of primary care-based chronic opioid therapy for pain: a retrospective cohort study. JGIM. 2019; 34 (12): 2749-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Olivia EM, Bowe T, Manhapra A, et al. Associations between stopping prescriptions for opioids, length of opioid treatment, and overdose or suicide deaths in US veterans: an observational study. BMJ. 2020;368:m283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Lowenstein M, Hossain E, Yan W, et al. Impact of a state opioid prescribing limit and electronic medical record alert on opioid prescriptions: a difference-in-differences analysis. JGIM. 2019;35(3):662-671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Gladstone EJ, Smolina K, Weymann D, et al. Geographic variations in prescription opioid dispensations and deaths among women and men in British Columbia, Canada. Med Care. 2015;53:954-959. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Gomes T, Juurlink DN, Moineddin R, et al. Geographic variation in opioid prescribing and opioid-related mortality in Ontario. Healthcare Quart Rev. 2011;14(1):22-24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Modarai F, Mack K, Hicks P, et al. Relationship of opioid prescription sales and overdoses, North Carolina. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132 (1):81-86. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Romeiser JL, Labriola J, Meliker JR. Geographic patterns of prescription opioids and opioid overdose deaths in New York State, 2013-2015. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;195:94-100. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Fischer B, Jones W, Varatharajan T, et al. Correlations between population-levels of prescription opioid dispensing and related deaths in Ontario (Canada), 2005-2016. Prev Med. 2018;116:112-118. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Fischer B, Jones W, Urbanoski K, et al. Correlations between prescription opioid analgesic dispensing levels and related mortality and morbidity in Ontario, Canada, 2005–2011. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2014;33 (1):19-26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Sauber-Schatz EK, Mack KA, Diekman ST, et al. Associations be- tween pain clinic density and distributions of opioid pain relievers, drug-related deaths, hospitalizations, emergency department visits, and neonatal abstinence syndrome in Florida. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133 (1):161-166. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Kurani S, McCoy RG, Inselman J, et al. Place, poverty and prescriptions: a cross sectional study using Area Deprivation Index to assess opioid use and drug-poisoning mortality in the USA from 2012 to 2017. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e035376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.National Center for Health Statistics. Detailed Multiple Cause of Death (MCOD) Research Files, All Counties, 2009-2017, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program.

- 31.United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, Commuting Zones and Labor Market Areas. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/commuting-zones-and-labor-market-areas/

- 32.Kiang MV, Humphreys K, Cullen MR. Opioid prescribing patterns among medical provides in the United States, a retrospective, observational study. BMJ. 2020;368:16968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Moyo P, Gellad WF, Sabik LM, et al. Opioid prescribing safety measures in Medicaid enrollees with and without cancer. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(4):540-544. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Dasgupta N, Funk MJ, Proescholdbell S, Hirsch A, et al. Cohort study of the impact of high-dose opioid analgesics on overdose mortality. Pain Med. 2016;17(1):85-98. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Shah A, Hayes CJ, Bartin BC. Characteristics of initial prescription episodes and likelihood of long-term opioid use: United States, 2006-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(10):265-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Yang Z, Wilsey B, Bohm M, Weyrich M, et al. Overdose: pharmacy shopping and overlapping prescriptions among long-term opioid users in Medicaid. J Pain. 2015;16(5):445-453 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Wilson N, Kariisa M, Seth P, et al. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths – United States, 2017-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020a;69(11):290-297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Froot KA. Consistent covariance matrix estimation with cross-sectional dependence and heteroskedasticity in financial data. J Finan Quant Analysis. 1989;24: 333–355.

- 39.Food and Drug Administration. FDA identifies harm reported from sudden discontinuation of opioid pain medicines and requires label changes to guide prescribers on gradual, individualized tapering FDA Drug Safety Communication, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-identifies-harm-reported-sudden-discontinuation-opioid-pain-medicines-and-requires-label-changes

- 40.Fenton JJ, Agnoli AL, Xing G, Hang L, Altan AE, Tancredi DJ, Jerant A, Magnan E. Trends and rapidity of dose tapering among patients prescribed long-term opioid therapy, 2008-2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;1;2(11):e1916271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Skelly AC, Chou R, Dettori JR, Turner JA, et al. Noninvasive nonpharmacological treatment for chronic pain: a systematic review update. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2020 Apr. Report No.: 20-EHC009. [PubMed]

- 42.Mark TL, Parish W. Opioid medication discontinuation and risk of adverse opioid-related health care events. J Sub Abuse Treatment. 2019;103:58-63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.LaBelle CT, Han SC, Bergeron A, Samet JH. Office-based opioid treatment with buprenorphine (OBOT-B): statewide implementation of the Massachusetts Collaborative Care Model in Community Health Centers. J Sub Abuse Treatment. 2016;60:6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Barocas JA, White LF, Wang J, et al. Estimated prevalence of opioid use disorder in Massachusetts, 2011-2015: a capture-recapture analysis. Am J Pub Health. 2018;108:1675-1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Molton IR, Terrill AL. Overview of persistent pain in older adults. Am Psychologist. 2014; 69(2):197-207. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.McHugh RK, Devito EE, Dodd D, Carroll KM, et al. Gender differences in a clinical trial for prescription opioid dependence. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2013;45(1):38-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Olfson M, Wall M, Wang S, Crystal S, Blanco C. Service use preceding opioid-related fatality. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(6):538-544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Beauchamp GA, Winstanley EL, Ryan SA, Lyons MS. Moving beyond misuse and diversion: the urgent need to consider the role of iatrogenic addiction in the current opioid epidemic. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(11):2023-2029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Jena AB, Goldman D, Weaver L, Karaa-Mandic P. Opioid prescribing by multiple providers in Medicare: retrospective observational study of insurance claims. BMJ. 2014; 348:g1393. 10.1136/bmj.g1393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Baumblatt JAG, Wiedeman C, Dunn JR, et al. High-risk use by patients prescribed opioids for pain and its role in overdose deaths. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(5):796-801. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Warner M. Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 1999-2017: NCHS Data Brief, No. 329. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2018a.

- 52.Bao Y, Pan Y, Taylor A, Radakrishnan S, et al. Prescription drug monitoring programs are associated with sustained reductions in opioid prescribing by physicians. Health Affairs. 2016;35(6):1045-1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Saloner B, Levin J, Chang HY, Jones C, Alesxander GC. Changes in buprenorphine-naloxone and opioid pain reliever prescriptions after the Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansion. JAMA Network Open. 2018;1(4):e181588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Ciccarone D. The rise of illicit fentanyls, stimulants, and the fourth wave of the opioid overdose crisis. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2021;34(4):344-350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Maclean JC, Mallatt J, Ruhm CJ, Simon K. Economic studies on the opioid crisis: a review. NBER Working Paper Series. 2020;Working Paper 28067.

- 56.Dasgupta N, Beletsky L, Ciccarone D. Opioid crisis: no easy fix to its social and economic determinants. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(2):182-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Santo Jr T, Clark B, Hickman M, et al. Association of opioid agonist treatment with all-cause mortality and specific causes of death among people with opioid dependence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psych. 2021; 78(9):979-993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Razaghizad A, Windle SB, Filion KB, et al. The effect of overdose education and naloxone distribution: an umbrella review of systematic reviews. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(8):e1-e12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Fishbain DA, Cole B, Lewis J, et al. What percentage of chronic nonmalignant pain patients exposed to chronic opioid analgesic therapy develop abuse/addiction and/or aberrant drug-related behaviors? A structured evidence-based review. Pain Med. 2008;9(4):444-459 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Hedegaard H, Minino A, Warner M. Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 1999-2017. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018b.

- 61.Cerda M, Santaella J, Marshall BDL, Kim JH, Martins SS. Non- medical prescription opioid use in childhood and early adolescence predicts transitions to heroin use in young adulthood: a national study. J Pediatr. 2015;167(3):605-612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 7001 kb)

(DOCX 54 kb)