Abstract

A staggering number of individuals live with cognitive decline. Primary care providers are ideally situated to detect the first signs of cognitive decline, but many persons remain undiagnosed. This limits their access to appropriate care. Unfortunately, the timely diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment or dementia in primary care is difficult to achieve. There is a great need for interventions to address this problem. This article applies an implementation science framework, the Behavioral Change Wheel, to evaluate the factors that influence detection of cognitive impairment in primary care and proposes candidate interventions for future study.

Among the highest priority milestones in the US National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s Disease is early detection of cognitive impairment.1 This milestone recognizes the growing burden of both dementia and mild cognitive impairment (MCI). It also recognizes how for most people the diagnostic journey begins in primary care,2 but in that setting dementia is under-diagnosed, and there is a shortage of specialists available to diagnose these individuals.3,4 The problem of dementia under-diagnosis is especially large in non-Whites and those with lower educational attainment.5,6

Interventions to address under-diagnosis in primary care have been tested. They include policy changes, such as a cognitive screening requirement for the Medicare annual wellness visit. Unfortunately, there has been limited success to date.7 New approaches are needed.

National policy changes and alternative payment models are important, but strategies to improve our nation’s capacity to care for people living with dementia that do not address clinician-level barriers may have limited impact. Barriers to dementia evaluations in primary care at the level of the clinician are common. They include the complexity and time-intensive nature of a workup, the stigma that pervades Alzheimer’s disease, and perceived diagnostic futility.8 Use of a theoretical framework can help researchers devise targeted interventions more likely to effect change when there are significant clinical-level barriers to dementia detection present.

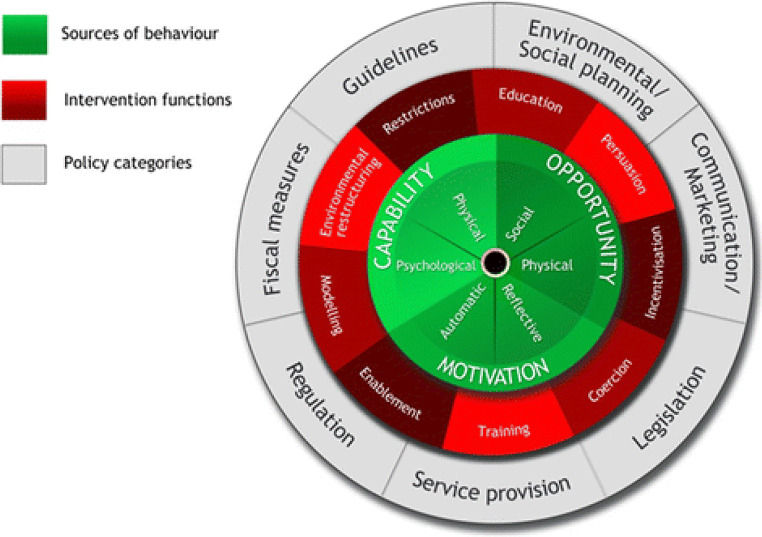

One promising framework is the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation, and Behavior (COM-B) model, central to the Behavioral Change Wheel (BCW). It emphasizes capability, opportunity, and motivation as the key factors influencing whether behavior change will be achieved.9 Other frameworks may be suitable to address the topic of dementia under-diagnosis, but the BCW is valuable because it focuses on methods to promote behavior change, it has been successfully used to design interventions targeting health-related behaviors in other areas of medicine, and it is derived from a systematic analysis of several other behavioral intervention frameworks to overcome their limitations.9–12 Here, we review how the COM-B domains can inform novel approaches for achieving increased detection of cognitive impairment and dementia in primary care.

CAPABILITY

In the BCW, capability describes the physical skills (physical capability) and knowledge or expertise (the BCW calls this “psychological capability”) an individual needs to perform the desired behavior. This is distinct from whether the individual has the motivation or opportunity to perform the behavior. In the context of performing cognitive evaluations, physical capability is an easy target to reach. It simply requires a provider have the physical skills needed to interview and examine a patient and order diagnostic testing, elements of routine clinical care.

The main barrier in the capability domain is knowledge and expertise, or psychological capability. Primary care clinicians describe how they lack the knowledge and confidence to perform dementia evaluations.4,13 This is understandable. The methods to detect hypertension or diabetes are straightforward. In contrast, the methods to detect cognitive impairment are complex. They require a cognitive exam, functional status assessment, blood work, and, when impairment is detected, brain imaging. Across primary care clinicians, the tremendous variability in dementia evaluation and care is evidence of the need for knowledge supports.4,14

Decision aids for medical decision-making could offer real-time, continuous support for psychological capability. Some aids have been successful in improving quality of care, including one which increased vaccination and cancer screening rates in primary care.15,16 A decision aid that prompted providers to investigate or manage dementia was shown to increase detection of dementia in primary care.17 Integrated into an electronic health record (EHR), these aids could prompt the caregiver, clinician, or other members of the care team to collect necessary information, such as cognitive and functional data, and integrate results of the diagnostic testing to provide an objective assessment of the data and assist clinicians with interpretation. Implementing EHR-integrated decision aids may be useful to health systems looking to improve their capacity to detect and diagnose dementia.

Educational methods also hold promise. Academic detailing, or peer-to-peer educational outreach, is one method with potential. It has successfully improved adherence to evidence-based practices for depression management.18,19 Academic detailing is a core component of the Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) model developed by the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center. Preliminary data on the ECHO model’s effectiveness in pain management, cancer prevention, and HIV are promising.20 The Alzheimer’s Association has partnered with Project ECHO to provide education on Alzheimer’s diagnosis and care. In a six-month program, primary care providers participate in case-based learning led by dementia experts on topics such as evaluation and diagnosis of dementia, care planning, and care management. Its effectiveness in improving dementia detection in primary care should be investigated.20,21

Developing psychological capability for dementia diagnosis and care can begin early in a clinician’s career. Dementia training in medical school is variable.22 There is evidence that a collaborative approach of education and work-based learning can increase trainee confidence in memory evaluations.23,24 These programs are however not widely disseminated.

Developing a dementia-capable workforce requires that medical and advanced practice provider curricula prioritize dementia, and clinical rotations provide greater exposure to dementia, particularly in family and internal medicine residencies. The clinical training should be a collaborative effort between primary care, geriatrics, neurology, and geriatric psychiatry. Trainees need rotations in dementia clinics and didactics delivered by multidisciplinary teams.

OPPORTUNITY

In the BCW, opportunity describes factors outside the individual that make behavior change possible and is divided into environmental (or physical) and social influences.9 Assessments of these influences are well-described in, for example, the development of models to improve health outcomes for patients with mental illness.25,26 One intervention to increase cardiometabolic screening in patients with severe mental illness used a peer navigator to assist patients with physical or mental disabilities to increase their likelihood of completing diagnostic testing. 26 Addressing the opportunity for early dementia detection requires environmental supports and social influences to encourage providers to evaluate for cognitive impairment. This is a promising area under investigation in several academic centers. Recently, Bernstein et al. described three paradigms being tested by the Consortium for Detecting Cognitive Impairment Including Dementia (DetectCID) to improve the quality and frequency of patient evaluations for cognitive impairment in primary care.27 Key features of their implementation address the environmental factors and social influences.

One of these is lack of time, a significant barrier to performing dementia evaluations.8,28 Methods to address this factor by DetectCID include use of an electronic cognitive assessment built into the EHR that can be administered by a medical assistant and SmartPhrases to summarize testing results and streamline the referral process.

Social influences and supports are addressed by features such as use of advocate clinicians to promote implementation of the new paradigm and facilitating consultation with a support network of dementia experts for assistance.27 If DetectCID paradigms are found to be effective, future studies should examine how to address the environmental supports and social influences in rural or low-resource settings to allow for the paradigm’s wider dissemination.

MOTIVATION

The Behavioral Change Wheel component that is least studied in improving detection of dementia is clinician motivations. Given the success of targeting clinician motivations in other areas of medicine, such as deprescribing initiatives and adoption of evidence-based practices,29–31 this has potential to improve clinician detection of dementia. The BCW has two types of motivations: automatic and reflective. The former describes impulsive or reflexive behaviors, and the latter are deliberate decisions to behave a certain way.9

Automatic motivations use behavioral economics approaches such as nudges, where, without restricting choice, small changes to an environment or the way information is delivered can influence behavior.32 Nudges have been successfully applied to improve care delivery for diseases and treatments such as obesity, cancer screening, vaccinations, hypertension, and medication de-prescribing.29–31 There are six categories of nudges: priming (subconscious cues used to promote a particular choice), salience/affect (vivid examples or explanations used to increase attention to a certain choice), default (the desired choice is preset to be the easiest option), incentive (incentives reinforce a positive choice or penalties discourage a negative choice), commitment/ego (making a public promise to elevate desire to feel good about themselves), and norms and messenger (using peer leaders to establish a norm and communicate with other providers).33

The success of nudges in other areas of health care suggests they are a promising approach to improve the detection of cognitive impairment and thus deserve further investigation.30 Table 1 provides examples of how they could address barriers to detection of cognitive impairment. A priming nudge could use prompts within the EHR to trigger a cognitive assessment. A concern for cognitive impairment, such as from a patient or family member complaint, could be entered in an EHR field by a nurse or medical assistant. This in turn would alert the provider to collect and enter information about the patient’s cognitive and functional status using a “Smart Tool” in the EHR. A salience/affect nudge could give clinicians feedback on how their patients have benefited from early detection of cognitive impairment. This may lead to positive associations with early detection and lead clinicians to perform more diagnostic evaluations. Incentive nudges could use audit and feedback via reports given to clinicians assessing their adherence to dementia evaluation guidelines and how they have performed relative to their peers. Norm and messenger nudges could use clinic or departmental leadership endorsement of a dementia care model, practice guideline, or cognitive evaluation tool to encourage their use.

Table 1.

How Behavioral Nudges Can Address Barriers to Detection of Cognitive Impairment

| Nudge mechanism | Example | Barrier(s) addressed |

|---|---|---|

| Priming | EHR tool to prompt clinician to collect cognitive and functional data and order necessary tests |

- Knowledge (EHR directs clinician to conduct proper assessment) - Time (streamlined process) |

| Salience/affect | Patients give feedback to clinicians on benefits of diagnosis |

- Stigma (reinforces positive outcomes) - Knowledge (clinician learns of benefits of non-pharmacological management) |

| Incentive | Clinicians given feedback on their adherence to guidelines for the evaluation of cognitive impairment and their performance relative to peers | - Health system support (signals to clinician that this is an institutional priority) |

| Norm and messenger | Clinic leadership promote use of practice guideline or cognitive evaluation tool | - Local support (signals to clinician that this is a clinic priority) |

Interventions targeting reflective motivations can address perceptions of diagnostic futility and dementia stigma. Targeted campaigns to persuade providers of the positive outcomes associated with early diagnosis are needed. Providers need to appreciate how detecting dementia in primary care can benefit patients and their families and improve patient care. Campaigns could use a combination of education and advocacy to dispel negative perceptions and increase optimism about early detection of cognitive impairment. Academic detailing, previously discussed as a way to enhance psychological capability, could address the benefits of early lifestyle interventions to slow symptom progression and how, even in the absence of a disease-slowing drug, comprehensive psychosocial management is a crucial benefit of early detection.34–37 Education could be used with a salience/affect nudge such as the example above, or with the inclusion of people living with dementia to advocate for early diagnosis. These activities could be supported by organizations such as the Alzheimer’s Association, which has assembled an Early-Stage Advisory Group of individuals living with dementia to share their personal experiences and increase awareness.38

INTERVENTION DESIGN

Improving dementia detection in primary care is complex, but an implementation science framework such as the BCW can help construct and evaluate interventions to achieve this goal. The BCW framework suggests nine intervention functions (such as education or incentivization) and seven policy categories (such as marketing or legislation) to aid design of behavior change interventions (Fig. 1).9 For the complex problem of dementia under-detection, a multicomponent intervention is likely necessary. Improving dementia diagnosis in primary care must use methods that address multiple barriers, respect the local context of practice, and attend to health equity. The investigation of approaches to improve dementia diagnosis in primary care must attend to social and structural determinants of health. Availability of transportation, proximity to health care centers, income, language, and literacy among other factors will influence patient access to diagnosis and care. Understanding which factors create health disparities in each practice context will help ensure their mitigation when developing and testing diagnostic approaches.

Figure 1.

The Behavioral Change Wheel.9

LOOKING FORWARD

Chronologic age is among the leading risk factors for dementia. As America’s elderly population grows, the prevalence of dementia will increase. Health systems need a dementia-capable workforce to care for these individuals. To achieve this, researchers must examine ways to change clinician behaviors to improve early detection and care for people with dementia.

Funding

Kyra O’Brien and Jason Karlawish were supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U54AG063546, which funds NIA Imbedded Pragmatic Alzheimer’s Disease and AD-Related Dementias Clinical Trials Collaboratory (NIA IMPACT Collaboratory), and under award number P30AG072979, which funds the University of Pennsylvania Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Dr. O'Brien and Dr. Burke report no conflicts of interest. Dr. Karlawish reports grants from Biogen, Lilly, and Novartis.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.2019 ADRD Summit Recommendations. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/sites/default/files/2019_adrd_summit_recommendations_508c.pdf. Accessed 1 Apr 2022.

- 2.Drabo EF, Barthold D, Joyce G, Ferido P, Chang Chui H, Zissimopoulos J. Longitudinal analysis of dementia diagnosis and specialty care among racially diverse Medicare beneficiaries. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(11):1402-1411. 10.1016/j.jalz.2019.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Bradford A, Kunik ME, Schulz P, Williams SP, Singh H. Missed and delayed diagnosis of dementia in primary care: prevalence and contributing factors. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23(4):306-314. 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181a6bebc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.2020 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2020;16(3):391-460. 10.1002/alz.12068.

- 5.Amjad H, Roth DL, Sheehan OC, Lyketsos CG, Wolff JL, Samus QM. Underdiagnosis of dementia: an observational study of patterns in diagnosis and awareness in US older adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(7):1131-1138. 10.1007/s11606-018-4377-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Tsoy E, Kiekhofer RE, Guterman EL, et al. Assessment of racial/ethnic disparities in timeliness and comprehensiveness of dementia diagnosis in California. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(6):657. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.0399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Fowler NR, Campbell NL, Pohl GM, et al. One-year effect of the medicare annual wellness visit on detection of cognitive impairment: a cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(5):969-975. 10.1111/jgs.15330. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Mansfield E, Noble N, Sanson-Fisher R, Mazza D, Bryant J. Primary care physicians’ perceived barriers to optimal dementia care: a systematic review. Heyn PC, ed. Gerontologist. 2019;59(6):e697-e708. 10.1093/geront/gny067. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):42. 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Isenor JE, Bai I, Cormier R, et al. Deprescribing interventions in primary health care mapped to the Behaviour Change Wheel: a scoping review. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2021;17(7):1229-1241. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Philippine T, Forsgren E, DeWitt C, Carter I, McCollough M, Taira BR. Provider perspectives on emergency department initiation of medication assisted treatment for alcohol use disorder. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):456. 10.1186/s12913-022-07862-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Ekberg K, Timmer B, Schuetz S, Hickson L. Use of the Behaviour Change Wheel to design an intervention to improve the implementation of family-centred care in adult audiology services. Int J Audiol. 2021;60(sup2):20-29. 10.1080/14992027.2020.1844321. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Turner S, Iliffe S, Downs M, et al. General practitioners’ knowledge, confidence and attitudes in the diagnosis and management of dementia. Age Ageing. 2004;33(5):461-467. 10.1093/ageing/afh140. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Bernstein A, Rogers KM, Possin KL, et al. Dementia assessment and management in primary care settings: a survey of current provider practices in the United States. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):919. 10.1186/s12913-019-4603-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Mahmoud A, Alkhenizan A, Shafiq M, Alsoghayer S. The impact of the implementation of a clinical decision support system on the quality of healthcare services in a primary care setting. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2020;9(12):6078. 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1728_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Roshanov PS, You JJ, Dhaliwal J, et al. Can computerized clinical decision support systems improve practitioners’ diagnostic test ordering behavior? A decision-maker-researcher partnership systematic review. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):88. 10.1186/1748-5908-6-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Downs M, Turner S, Bryans M, et al. Effectiveness of educational interventions in improving detection and management of dementia in primary care: cluster randomised controlled study. BMJ. 2006;332(7543):692-696. 10.1136/bmj.332.7543.692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.O’Brien MA, Rogers S, Jamtvedt G, et al. Educational outreach visits: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Published online October 17, 2007. 10.1002/14651858.CD000409.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Patel B, Afghan S. Effects of an educational outreach campaign (IMPACT) on depression management delivered to general practitioners in one primary care trust. Ment Health Fam Med. 2009;6(3):155-162. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Agley J, Delong J, Janota A, Carson A, Roberts J, Maupome G. Reflections on project ECHO: qualitative findings from five different ECHO programs. Med Educ Online. 2021;26(1):1936435. 10.1080/10872981.2021.1936435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.The Alzheimer’s and Dementia Care ECHO® Program for Clinicians | Alzheimer’s Association. https://www.alz.org/professionals/health-systems-clinicians/echo-alzheimers-dementia-care-program. Accessed 13 April 2022.

- 22.Jacinto AF, Leite AGR, Lima Neto JL de, Vidal EI de O, Bôas PJFV. Teaching medical students about dementia: A brief review. Dement Neuropsychol. 2015;9(2):93-95. 10.1590/1980-57642015DN92000002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Lee L, Weston WW, Hillier L, Archibald D, Lee J. Improving family medicine resident training in dementia care: An experiential learning opportunity in Primary Care Collaborative Memory Clinics. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2020;41(4):447-462. 10.1080/02701960.2018.1484737. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Padala KP, Mendiratta P, Orr LC, et al. An interdisciplinary approach to educating medical students about dementia assessment and treatment planning. Fed Pract Health Care Prof VA DoD PHS. 2020;37(10):466-471. 10.12788/fp.0052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Murphy AL, Gardner DM, Kutcher SP, Martin-Misener R. A theory-informed approach to mental health care capacity building for pharmacists. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2014;8(1):46. 10.1186/1752-4458-8-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Mangurian C, Niu GC, Schillinger D, Newcomer JW, Dilley J, Handley MA. Utilization of the Behavior Change Wheel framework to develop a model to improve cardiometabolic screening for people with severe mental illness. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):134. 10.1186/s13012-017-0663-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Bernstein Sideman A, Chalmer R, Ayers E, et al. Lessons from Detecting Cognitive Impairment Including Dementia (DetectCID) in Primary Care. J Alzheimers Dis. 2022;86(2):655-665. 10.3233/JAD-215106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Romano RR, Carter MA, Anderson AR, Monroe TB. An integrative review of system-level factors influencing dementia detection in primary care. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2020;32(4):299-305. 10.1097/JXX.0000000000000230. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Patel MS, Volpp KG, Asch DA. Nudge Units to Improve the Delivery of Health Care. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(3):214-216. 10.1056/NEJMp1712984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Yoong SL, Hall A, Stacey F, et al. Nudge strategies to improve healthcare providers’ implementation of evidence-based guidelines, policies and practices: a systematic review of trials included within Cochrane systematic reviews. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):50. 10.1186/s13012-020-01011-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Meeker D, Linder JA, Fox CR, et al. Effect of behavioral interventions on inappropriate antibiotic prescribing among primary care practices: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(6):562. 10.1001/jama.2016.0275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Thaler RH, Sunstein CR. Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth and Happiness. Revised edition, new international edition. Penguin Books; 2009.

- 33.Dolan P, Hallsworth M, Halpern D, King D, Metcalfe R, Vlaev I. Influencing behaviour: The mindspace way. J Econ Psychol. 2012;33(1):264-277. 10.1016/j.joep.2011.10.009.

- 34.Bayer-Carter JL, Green PS, Montine TJ, et al. Diet intervention and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(6). 10.1001/archneurol.2011.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Lourida I, Soni M, Thompson-Coon J, et al. Mediterranean diet, cognitive function, and dementia: a systematic review. Epidemiology. 2013;24(4):479-489. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3182944410. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Desai P, Evans D, Dhana K, et al. Longitudinal association of total Tau concentrations and physical activity with cognitive decline in a population sample. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(8):e2120398. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.20398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Heintz H, Monette P, Epstein-Lubow G, Smith L, Rowlett S, Forester BP. Emerging collaborative care models for dementia care in the primary care setting: a narrative review. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;28(3):320-330. 10.1016/j.jagp.2019.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Early-Stage Advisory Group | Alzheimer’s Association. https://www.alz.org/about/leadership/early-stage-advisory-group. Accessed 13 April 2022.