Abstract

The Oncology Care Model (OCM), launched in 2016 by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, was the first demonstration of value-based payment in oncology. Although the OCM delivered mixed results in terms of quality of care and total episode costs, the model had no statistically significant impact on remediating racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities among beneficiaries. These deficits have been prominent in other aspects of US healthcare, and as a result, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement has advocated for stakeholders to leverage improvement science, an applied science that focuses on implementing rapid cycles for change, to identify and overcome barriers to health equity. With the announcement of the new Enhancing Oncology Model, a continuation of the OCM’s efforts in introducing value to cancer care for episodes surrounding chemotherapy administration, both policymakers and providers must apply tenets of improvement science and make eliminating disparities in alternative payment models a forefront objective. In this commentary, we discuss previous inequities in alternative payment models, the role that improvement science plays in addressing health-care disparities, and steps that stakeholders can take to maximize equitable outcomes in the Enhancing Oncology Model.

Value-based payment models, which hold providers accountable for high quality at lower costs, are uniquely positioned to deliver efficient care and address racial and socioeconomic disparities. With the national cost of cancer drastically increasing every year, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) launched the Oncology Care Model (OCM) in 2016, a pioneering alternative payment model (APM) focused on introducing value to cancer care through financial and performance accountability for episodes of care surrounding chemotherapy administration. Although the OCM represented the first major demonstration of value-based care in oncology and partially achieved its goal of reducing 6-month episode costs, the model made no statistically significant impact on health equity (1,2). Given similar deficits in previous equity efforts throughout US health care, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) advocates that health-care organizations and stakeholders leverage improvement science, an applied science that emphasizes rapid-cycle testing per a clear measurement plan to generate knowledge about what changes, in which contexts, produce desired improvements (3).

As more Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries enter into accountable care relationships, APMs must harness the teachings of improvement science and make racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic equity a priority. The proposed Enhancing Oncology Model (EOM), a continuation of the OCM’s objective of advancing value-based payment in oncology, is a promising first step in embedding equity and the social determinants of health (SDOH) into the framework of modern care delivery. However, to maximally achieve equitable outcomes throughout the duration of the model, CMS needs to devise novel incentives that tie SDOH reporting to actionable response, support all participants with the requisite services to ensure a smooth transition from the OCM, create robust and dynamic risk adjustment models, and appropriately diffuse performance-based financial risk for less-resourced providers.

Inequities in oncology APMs

Although the OCM and other APMs have delivered mixed results in terms of performance, it remains a consensus that previous value-based programs in oncology have fallen short of embedding equity into their models and engaging providers with marginalized patient populations. For example, in a report evaluating the OCM through performance period 5 (2016-2019), the CMS disclosed that the OCM reduced episode cost by $256 (P < .05) for White beneficiaries but had no statistically significant impact for Black and Hispanic beneficiaries. Hispanic patients also reported small but statistically significant declines in patient-reported care experience (decline of 0.4 survey points on a scale from 0 to 10), and both Black and Hispanic patients found inadequate support for end-of-life care (2,4). Furthermore, the OCM did not decrease beneficiary out-of-pocket expenses, including deductibles and copays, for Medicare Part A, B, and D services, thereby failing to address longstanding issues associated with financial toxicity for low-income individuals (2). Additionally, Aggarwal et al. (5) and Johnston et al. (6) concluded, respectively, that hospitals with a higher proportion of Black patient populations (defined as hospitals with a high proportion of Medicare hospitalizations for Black patients) and clinicians with greater minority caseloads were more likely to perform worse in Medicare’s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program, Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program, or Merit-Based Incentive Payment System and be disproportionately penalized by payers (hospitals with a high proportion of Black patients: 23.4%, vs other hospitals penalized: 12.3%; P < .001). These inequities were largely mirrored throughout the full length of the OCM, and with the introduction of downside risk for low-performing practices in 2019, participation in the model plummeted by more than 34% at its conclusion (7).

Overall, the purpose of the OCM was to balance multiple priorities, such as form the logistic groundwork for APM implementation in oncology, improve quality of care, and reduce episode costs. Therefore, a natural progression of this model should be to focus on creating and benchmarking equity at various clinical touchpoints. Achieving this goal will require all involved stakeholders to understand the tenets of improvement science as well as apply these lessons to policy redesign.

Using improvement science to address health equity

The IHI carefully defines the Model for Improvement as a continuous process for testing change that asks 3 questions: What are we trying to accomplish? How will we know that a change is an improvement? What changes can we make that will result in improvement? In other words, all improvement efforts should encompass 1) a clear, measurable aim; 2) a comprehensive measurement framework that assesses progress; 3) a description of the ideas and how these ideas will result in change; 4) a detailed execution strategy to ensure adoption of the ideas; 5) a dedication to rapid testing, prediction, and learning from tests; and 6) a robust visualization system to describe, understand, and learn from heterogeneity in data (8,9). Equity has often eluded APMs because providers lack the knowledge of how to measure appropriate outcomes and properly devise, introduce, and monitor change as encouraged by improvement science. Indeed, the improvement science framework has been successfully leveraged by the IHI to improve health equity in low- and middle-income countries. For example, to improve maternal and newborn health outcomes in Ethiopia, the IHI and the Ethiopia Ministry of Health liaised with district hospitals to engage participatory women’s groups, leverage data managers to disaggregate patient data and proactively address disparities, and collaborate with patient navigators to comprehensively serve disadvantaged populations (10,11). These initiatives resulted in improved quality overall, with most facility teams reporting over 90% adherence to all labor and care pathways and improvement in at least 1 outcome of maternal and neonatal service coverage (12).

The EOM signifies a promising shift in value-based care delivery precisely because many of these components are embedded into its design. For example, to address the lack of equity in the OCM, participants in the EOM are required to screen patients for health-related social needs, such as malnutrition during chemotherapy, limited transportation access to infusion appointments, and housing insecurity, that can contribute to or exacerbate cancer disparities (13). Moreover, providers must agree to a measurement framework provided by CMS and report beneficiary-level sociodemographic data (eg, race, ethnicity, cultural identity, language preference, disability status, sexual orientation, and gender identity) in addition to electronic patient-reported outcomes to payers. In contrast to previous efforts by the IHI, however, CMS solely outlines quality improvement expectations for oncologists in the EOM without providing tangible guardrails to ensure these objectives are successfully met. As CMS strives to create more equitable oncology value-based payment models, it will be crucial that they abide by the Model for Improvement and collaborate with providers to translate ambition into action.

Call for improvement

Although the EOM makes substantial progress in addressing social needs among beneficiaries, barriers remain that complicate the realization of equity in value-based care. As a result, it is imperative that improvement science models are continually iterated on to identify and resolve problems throughout the duration of the EOM. We present 4 immediate steps that both CMS and providers can take to create more equitable outcomes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Improvements in the EOM and future steps to achieve health equity in value-based oncology modelsa

| OCM | EOM | Future steps |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

CEHRT = certified electronic health record technology; CMS = Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; EOM = Enhancing Oncology Model; ePRO = electronic patient reported outcome; HIT = health information technology; HRSN = health-related social need; ICHOM = International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement; IHI = Institute for Healthcare Improvement; LIS = low-income subsidy status; MEOS = Monthly Enhanced Oncology Services; OCM = Oncology Care Model; PBR = performance-based recoupment; SDOH = social determinants of health; SOC = standard of care.

First, new incentives need to be devised that more effectively tie SDOH reporting with concrete action. Although the reporting requirement in the EOM represents a major improvement from the OCM, Friedberg et al. (14) concluded in a qualitative case study incorporating 34 physician practices that extra documentation requirements in APMs create discontent and are often perceived by providers as irrelevant to both patient care and downstream disparities. Similarly, in a systematic review of 71 studies, the inclusion of SDOH data in electronic health records failed to ensure necessary referrals to community-based organizations (CBOs) and prevent downstream emergency department visits, general hospitalizations, and readmissions for marginalized populations (15). With the EOM now mandating participants to submit care plans promoting health equity, improvement science can be leveraged to ensure that SDOH screening is met with tangible response protocols. Namely, to prevent SDOH reporting from becoming an administrative burden without material benefits for patients, CMS can first identify bottlenecks in the documentation streams and begin reimbursing providers for requisite support staff that manage these new data workflows. Alternatively, participants can directly contract with CBOs and SDOH stakeholders that specialize in managing social health and diffuse performance-based financial risk appropriately. These personnel would be accountable for screening patients for health-related social needs and patient-reported outcomes, creating and implementing equity plans, and tracking longitudinal outcomes.

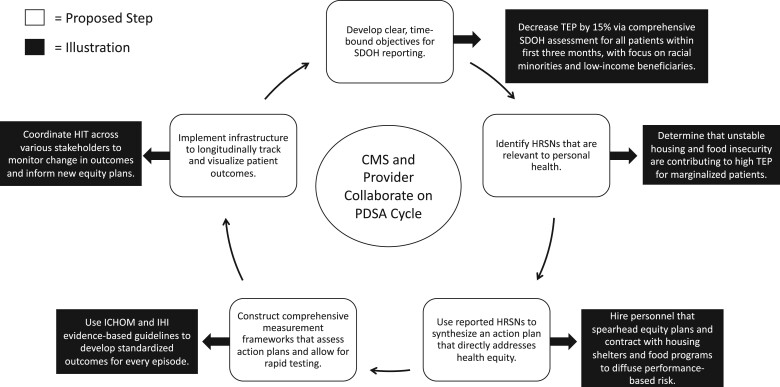

Generally, this concept of integrating CBOs into the care continuum has been extensively pursued by accountable care organizations (ACOs)—groups of providers that are held accountable for the quality, cost, and experience of care of an assigned Medicare fee-for-service beneficiary population—and the US Department of Veteran Affairs (VA). For example, to address behavioral health among beneficiaries in the Pioneer ACO model, participating ACOs developed robust depression and mental health screening guidelines and partnered with behavioral health facilities, CBOs, and social workers for treatment assistance (16). Nearly 60% of all patient engagement was conducted through contact with CBOs, which contributed to improvements in provider communication, rating of physicians, shared decision-making, and overall quality of care (16). Moreover, the VA has incorporated CBOs into its care pathway through Veteran Community Partnerships, which in 2020 involved more than 40 community organizations and over 7700 veterans (17). Veteran Community Partnerships leverage community resources by training local providers about veteran cultural competency, screening, prevention, and mental health referrals and have improved care coordination and increased health-care access throughout the VA (17,18). In a broader sense, a recent survey conducted by USAging (formerly the National Association of Area Agencies on Aging) indicated that the proportion of their partner CBOs contracting with health-care providers statistically significantly increased from 38% in 2017 to 44% in 2021. Additionally, the percent of these CBOs directly entering risk-based contracts with Medicare Advantage plans doubled between 2018 and 2020 from 10% to 20%. This contracting has led to improved management of SDOH, with many health networks reporting reductions in Medicare expenditures, avoidable nursing home placement, and social isolation (19). All in all, participants in oncology APMs can learn from these initiatives and advise CBOs to best identify, document, and mitigate social risk. Throughout this process, improvement science frameworks should be used to foster collaboration where necessary and standardize efforts across stakeholders. By leveraging successive plan-do-study-act cycles, which allow for continuous feedback and total quality improvement, participants can indeed confirm that SDOH reporting will translate to greater health equity (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Using an improvement science cycle to maximize the value of social determinants of health (SDOH) documentation streams. aBoth Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the provider must collaborate on implementing plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles that identify social needs within beneficiary populations and mitigate disparities through rapid-cycle testing. The white boxes represent proposed steps of an improvement science framework, and the black boxes represent potential examples of application. HIT = health information technology; HRSN = health-related social need; ICHOM = XXX; IHI = Institute for Healthcare Improvement; TEP = total episode payment.

Second, participants need more direct support during the lengthy transitory period between the end of the OCM, June 30, 2022, and the start of the EOM, July 1, 2023 (13). To prepare for the EOM, providers must mobilize or develop infrastructure, IT workflows, and the necessary operations to support the extensive screening and documentation required. Without reimbursement from CMS in the interim, however, less-resourced providers––including community oncology practices that care for vulnerable patients––are already at a disadvantage (20). Despite this unfortunate circumstance, both providers and policymakers can be proactive and use continuous improvement ideologies to foster equity throughout the transition. For instance, CMS can reward participants who properly deploy staff, infrastructure, and workflows before the start date and encourage inexperienced providers with direct payments and logistical support. Because safety-net and community providers disproportionately care for minority patients, it is imperative that they have sufficient capital and guidance to succeed in value-based payment models. One mechanism that CMS can leverage to provide such upfront financial support is to allow participants to borrow against their future Monthly Enhanced Oncology Services (MEOS) payments, which are per-beneficiary reimbursements for the provision of enhanced services, such as 24/7 clinician access, patient navigation, and treatment with therapies consistent with nationally recognized clinical guidelines (21). Based on their infrastructural and capital needs before the start of the program, participants can request requisite funding from CMS in advance that will eventually be deducted from their future MEOS reimbursements. Once such funding mechanisms are established, standardized performance frameworks can help to evaluate whether direct payments to underresourced practices are actually fostering equity. Upon collecting feedback from stakeholders, CMS can then decide whether to expand the scope of this intervention or formulate new incentives entirely. Nonetheless, by engaging all participants throughout the entire transition period, payers can have the ability to increase participant retention, support underresourced practices who care for vulnerable patients, as well as improve provider performance during the EOM (22,23).

Third, CMS needs to create more robust and dynamic risk adjustment models that appropriately modify target prices and quality outcomes. In the current EOM, risk adjustment will be based on price prediction models that are unique to each cancer type, with an increased emphasis placed on clinical and staging data reported by EOM participants. Additionally, benchmark prices for every episode will be further adjusted based on each beneficiary’s dual Medicare-Medicaid eligibility status and Low-Income Subsidy eligibility as proxies for income and social risk (24). Although these changes represent improvements from the OCM, engaging participants with diverse case mixes will necessitate using more than solely these proxies of socioeconomic risk. For example, in the new ACO Realizing Equity, Access, and Community Health model, which was created by CMS in response to existing inequities in value-based care, each ACO member in the top decile of disadvantage will be given a $30/mo increase in spending benchmarks. This disadvantage score is calculated using individual and neighborhood-level markers, including an area deprivation index—a composite measure of socioeconomic disadvantage based on income, education, household characteristics, and housing—and a neighborhood stress score—a composite measure of economic stress based on needed household assistance, unemployment status, and family income (25). By adjusting target episode prices for factors that directly quantify socioeconomic risk, ACOs may be incentivized to care for the most vulnerable patient populations and, in turn, receive increased cost savings for efficient and effective episode management (26). CMS can translate this approach to the EOM and incorporate ecologic variables, such as neighborhood stress score, to allow for more comprehensive target price adjustment. This is especially pertinent for the early stages of the model when CMS is attempting to understand how sociodemographic outcome reporting and equity plans affect target expenditure calculations. Moreover, should a patient’s income or social risk evolve temporally over the course of an episode, CMS can modify previously established target prices in real-time to account for the dynamic nature of a beneficiary’s SDOH. Ultimately, by supporting providers with accurate benchmark price adjustments that explicitly incorporate socioeconomic risk, both higher- and lower-resourced participants are more likely to remain in the model, earn performance-based payments (PBPs), and reach transformation goals.

Fourth, policymakers must reevaluate the structural elements of the EOM and introduce downside risk more appropriately. Specifically, CMS is cutting the MEOS payment to $70 from its original $160 in the OCM (7,13). Additionally, all participants are required to accept downside risk from the start of the model and must pay CMS a performance-based recoupment depending on total quality performance and expenditures following an episode. Considering the exhaustive screening and reporting that providers in the EOM must conduct, CMS is effectively asking participants for more work with far less reimbursement, which is especially concerning given practices are already dealing with Medicare sequester cuts, COVID-19 challenges, and inflation, among other challenges (20). Two-sided risk also may not make financial sense for smaller practices and in fact can serve as a “significant barrier to enrollment,” as the Association of Community Cancer Centers notes in its most recent statement on the EOM (27). In fact, practices that participated in 2-sided risk and did not earn PBPs in the first 4 periods of the OCM were required to pay recoupments if target benchmark prices were not met. At the time this decision was made, approximately 47% of all participants did not meet transformation goals and failed to earn PBPs (28). Based on their existing infrastructure and patient demographics, practices will naturally require differential times to reach transformation goals.

Therefore, to balance participant retainment and achieve high-value care, CMS must uniquely diffuse risk for providers who are either inexperienced with practicing under APMs or caring for at-risk populations. As an example, new participants and safety-net providers can be identified using standardized metrics, such as patient demographics and past enrollment in APMs. CMS can then allow select providers to operate in an upside-risk setting, where reimbursement is conducted through performance-based and MEOS payments only. Notably, CMS is providing an additional $30 in MEOS reimbursements for beneficiaries with dual Medicare-Medicaid eligibility and is not holding these additional payments against providers in their total episode payment calculations. To better support practices with disadvantaged populations, CMS can withhold a larger proportion of these MEOS reimbursements from total episode expenditures such that providers are further encouraged to engage with these populations.

Once new participants and safety-net providers achieve high-value performance results as determined by quality outcomes, policymakers can subsequently adjust the current payment structure and introduce 2-sided risk as appropriate. Indeed, such 2-sided risk models can incorporate health equity benchmarks in addition to clinical outcomes and episode expenditures. Transitioning to such a 2-sided risk structure, in which the provider is accountable for high-value care, should be the end goal for the EOM and all future APMs. Confirming that this transition is equitable and practical, though, will necessitate developing unique incentives for underresourced providers and implementing and evaluating these systems through standardized frameworks. The RAND Corporation, as well as the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network, and the National Minority Quality Forum, have made important strides in operationalizing standard health equity measures, developing performance frameworks, and piloting health equity score cards for providers to assess improvement. For instance, these report cards encourage practices and oncologists to meaningfully engage with their communities via patient advisory committees in linguistically and culturally appropriate manners, implement health information technology to identify particular segments of the care pathway where disparate care is occurring, and continuously document discussions regarding clinical trial options with all patients (29,30). With the EOM commencing in 2023, providers and policymakers alike need to do a better job of integrating these equity measure sets into the clinical workflow and using these data to inform overall decision making.

As value-based payment models evolve and become commonplace in medical specialties, ensuring that health equity is maintained will be a foremost priority in achieving better care. The EOM is a major milestone in that it leverages tenets of improvement science to promote equity across various stakeholders. However, with the model set to commence in 2023, increased focus needs to be devoted toward identifying policy issues before they become larger crises. As cancer researchers, patient advocates, and health-care providers guided by the continuous improvement process, we envision that the EOM will continue to adapt and deliver equitable, high-value care for all beneficiaries involved.

Contributor Information

Tej A Patel, Department of Health Care Management, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Bhav Jain, Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA.

Ravi B Parikh, Perelman School of Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA; Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Funding

The authors report no funding sources.

Notes

Role of the funder: This is not applicable.

Disclosures: TAP and BJ have no conflicts of interest to report. RBP reports receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health, Prostate Cancer Foundation, National Palliative Care Research Center, NCCN Foundation, Conquer Cancer Foundation, Humana, and Veterans Health Administration; personal fees and equity from GNS Healthcare, Inc. and Onc.AI; personal fees from Cancer Study Group, Thyme Care, Humana, and Nanology; honorarium from Flatiron, Inc. and Medscape; board membership (unpaid) at the Coalition to Transform Advanced Care; and serving on a leadership consortium (unpaid) at the National Quality Forum, all outside the submitted work.

Author contributions: Conceptualization: TAP, BJ, RBP. Writing—Original Draft: TAP, BJ. Supervision: RBP. Writing—Review and Editing: TAP, BJ, RBP.

Data availability

No data were used or generated for the writing of this commentary.

References

- 1. Keating NL, Jhatakia S, Brooks GA, et al. ; Oncology Care Model Evaluation Team. Association of participation in the oncology care model with Medicare payments, utilization, care delivery, and quality outcomes. JAMA. 2021;326(18):1829-1839. doi: 10.1001/JAMA.2021.17642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hassol A, West N, Newes-Adeyi G, et al. Evaluation of the oncology care model: performance periods 1-5. 2021. https://innovation.cms.gov/data-and-reports/2021/ocm-evaluation-pp1-5.

- 3. IHI - Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Our work. https://www.ihi.org/. Accessed July 29, 2022.

- 4. Hassol A, West N, Gerteis J, et al. Evaluation of the oncology care model: participants’ perspectives. 2021. https://innovation.cms.gov/data-and-reports/2021/ocm-ar4-eval-part-persp-report.

- 5. Johnston KJ, Meyers DJ, Hammond G, Joynt Maddox KE.. Association of clinician minority patient caseload with performance in the 2019 Medicare Merit-based Incentive Payment System. JAMA. 2021;325(12):1221-1223. doi: 10.1001/JAMA.2021.0031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aggarwal R, Hammond JG, Joynt Maddox KE, Yeh RW, Wadhera RK.. Association between the proportion of Black patients cared for at hospitals and financial penalties under value-based payment programs. JAMA. 2021;325(12):1219-1221. doi: 10.1001/JAMA.2021.0026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. CMS Innovation Center. Oncology Care Model. https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/oncology-care. Accessed July 12, 2022.

- 8. IHI - Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Science of improvement. http://www.ihi.org/about/Pages/ScienceofImprovement.aspx. Accessed July 12, 2022.

- 9. IHI - Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Useful insights, practical advice, and inspiring stories from IHI. http://www.ihi.org/communities/blogs. Accessed July 12, 2022.

- 10. Hirschhorn LR, Magge H, Kiflie A.. Quality improvement: aiming beyond equality to reach equity: the promise and challenge of quality improvement. BMJ. 2021;374:n939. doi: 10.1136/BMJ.N939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Magge H, Kiflie A, Nimako K, et al. The Ethiopia healthcare quality initiative: design and initial lessons learned. Int J Qual Health Care. 2019;31(10):G180-G186. doi: 10.1093/INTQHC/MZZ127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hagaman AK, Singh K, Abate M, et al. The impacts of quality improvement on maternal and newborn health: preliminary findings from a health system integrated intervention in four Ethiopian regions. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):522. doi: 10.1186/S12913-020-05391-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. CMS Innovation Center. Enhancing oncology model. https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/enhancing-oncology-model. Accessed July 12, 2022.

- 14. Friedberg MW, Chen PG, White C, et al. Effects of health care payment models on physician practice in the United States. www.rand.org/t/rr869. Published 2015. Accessed July 19, 2022. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15. Chen M, Tan X, Padman R.. Social determinants of health in electronic health records and their impact on analysis and risk prediction: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27(11):1764-1773. doi: 10.1093/JAMIA/OCAA143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nyweide D, Green L, Director P.. Evaluation of CMMI Accountable Care Organization Initiatives. Pioneer ACO Final Report. Published 2016.

- 17. National Center for Healthcare Advancement and Partnerships. Veteran community partnerships. https://www.va.gov/healthpartnerships/updates/vcp/08042020.asp. Accessed September 18, 2022.

- 18. Ward CJ, Child C, Hicken BL, et al. “We got an invite into the fortress”: VA-Community Partnerships for meeting veterans’ healthcare needs. IJERPH. 2021;18(16):8334. doi: 10.3390/IJERPH18168334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kunkel SR, Lackmeyer AE, Graham RJ, Straker JK. Advancing partnerships: contracting between community-based organizations and health care entities. Scripps Gerontology Center. Published 2022.

- 20. Community Oncology Alliance. Community Oncology Alliance Statement on the Enhancing Oncology Model. https://communityoncology.org/reports-and-publications/press-releases-media-statements/statement-enhancing-oncology-model/. Accessed July 13, 2022.

- 21. CMS. Enhancing Oncology Model: EOM Overview Webinar. Published 2022.

- 22. Mattingly II TJ, Slejko JF, Perfetto EM, dosReis SC.. Putting our guard down: engaging multiple stakeholders to define value in healthcare. Health Affairs Forefront. 2019. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20190125.84658/full/. Accessed July 14, 2022. doi:10.1377/forefront.20190125.84658. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Purnell TS, Calhoun EA, Golden SH, et al. Achieving health equity: closing the gaps in health care disparities, interventions, and research. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(8):1410-1415. doi: 10.1377/HLTHAFF.2016.0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chong A, Witherspoon E, Honig B, Cavanagh EE, Strawbridge HL.. Reflections on the oncology care model and looking ahead to the enhancing oncology model. J Clin Oncol Oncol Pract. 2022;18:OP2200329. doi: 10.1200/OP.22.00329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Accountable Care Organization (ACO). Realizing Equity, Access, and Community Health (REACH) Model. CMS website. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/accountable-care-organization-aco-realizing-equity-access-and-community-health-reach-model. Accessed September 21, 2022.

- 26. Gondi S, Joynt Maddox K, Wadhera RK.. “REACHing” for equity — moving from regressive toward progressive value-based payment. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(2):97-99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMP2204749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Association of Community Cancer Centers. ACCC Statement on the Enhancing Oncology Model. https://www.accc-cancer.org/home/news-media/news-releases/news-template/2022/06/29/accc-statement-on-the-enhancing-oncology-model. Accessed July 13, 2022.

- 28. Community Oncology Alliance. COA survey finds OCM participants willing to take on two-sided risk. https://communityoncology.org/news/press-releases-media-statements/coa-survey-finds-ocm-participants-willing-to-take-on-two-sided-risk/. Accessed September 8, 2022.

- 29. Chambers S, Winn R, Aguilera Z, et al. Elevating Cancer Equity: Recommendations to Reduce Racial Disparities in Access to Guideline Adherent Cancer Care. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Published 2021.

- 30. Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Developing health equity measures. https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/developing-health-equity-measures. Accessed September 21, 2022.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data were used or generated for the writing of this commentary.