Abstract

Background

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2), which causes novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19), is spreading rapidly around the world. Thrombocytopenia in patients with COVID‐19 has not been fully studied.

Objective

To describe thrombocytopenia in patients with COVID‐19.

Methods

For each of 1476 consecutive patients with COVID‐19 from Jinyintan Hospital, Wuhan, China, nadir platelet count during hospitalization was retrospectively collected and categorized into (0, 50], (50, 100], (100‐150], or (150‐) groups after taking the unit (×109/L) away from the report of nadir platelet count. Nadir platelet counts and in‐hospital mortality were analyzed.

Results

Among all patients, 238 (16.1%) patients were deceased and 306 (20.7%) had thrombocytopenia. Compared with survivors, non‐survivors were older, were more likely to have thrombocytopenia, and had lower nadir platelet counts. The in‐hospital mortality was 92.1%, 61.2%, 17.5%, and 4.7% for (0, 50], (50, 100], (100‐150], and (150‐) groups, respectively. With (150‐) as the reference, nadir platelet counts of (100‐150], (50, 100], and (0, 50] groups had a relative risk of 3.42 (95% confidence interval [CI] 2.36‐4.96), 9.99 (95% CI 7.16‐13.94), and 13.68 (95% CI 9.89‐18.92), respectively.

Conclusions

Thrombocytopenia is common in patients with COVID‐19, and it is associated with increased risk of in‐hospital mortality. The lower the platelet count, the higher the mortality becomes.

Keywords: COVID‐19, generalized linear model, mortality, SARS‐CoV‐2, thrombocytopenia

Essentials

-

•

Thrombocytopenia in patients with novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) needs further study.

-

•

A retrospective single‐centered study including 1476 patients was conducted.

-

•

Thrombocytopenia is common in patients with COVID‐19.

-

•

Thrombocytopenia is associated with increased risk of in‐hospital mortality.

Alt-text: Unlabelled Box

1. INTRODUCTION

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2), a new highly transmittable coronavirus, is spreading rapidly around the world.1 The virus causes a spectrum of diseases, named novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) by the World Health Organization (WHO).2 Among these diseases, pneumonia is studied most extensively.3., 4., 5., 6., 7. Complications associated with COVID‐19, including acute respiratory distress syndrome3., 4., 5., 6., 7. and cardiac injury,8 were associated with increased mortality. One small‐sample‐sized study reported that the rate of thrombocytopenia was 12%.4 Another study reported that 36.2% of patients had platelet count less than 150 × 109/L.7 However, the degree of thrombocytopenia and its association with mortality have not been fully elucidated.

The present large‐sample‐sized study from a single hospital in Wuhan, China, focused exclusively on thrombocytopenia. The objectives were to describe the epidemiology of thrombocytopenia and to explore the association between thrombocytopenia and mortality among patients with COVID‐19.

2. METHODS

Consecutive patients with confirmed COVID‐19 admitted to Wuhan Jinyintan Hospital since late December 2019, who were either discharged or deceased by February 25, 2020, were included. The diagnosis of COVID‐19 was according to WHO interim guidance and confirmed by RNA detection of SARS‐CoV‐2. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Jinyintan Hospital (KY‐2020‐06.01).

At admission, tests of complete blood count, including platelet count, were conducted and repeated on the discretion of treating physicians. All data on laboratory tests of patients with COVID‐19 were stored on a local server. After log files with information on hospital admission numbers were obtained, data on laboratory tests were retrieved and matched using admission numbers, which were unique to each patient. For each patient, the nadir platelet count was identified and categorized into (0, 50], (50, 100], (100‐150], or (150‐) groups after taking the unit (× 109/L) away from the report of nadir platelet count.

Data were expressed as median (interquartile range [IQR]) for continuous variables and count (percentage) for categorical variables. The differences between survivors and non‐survivors were explored using a Wilcoxon test or Fisher's exact test. A generalized linear model was then used to analyze the relative risk (RR) of death in age, gender, and groups of nadir platelet count. A double‐sided P‐value < .05 indicated statistical significance. The Stata/IC 15.1 software (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA) was used for all analyses.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

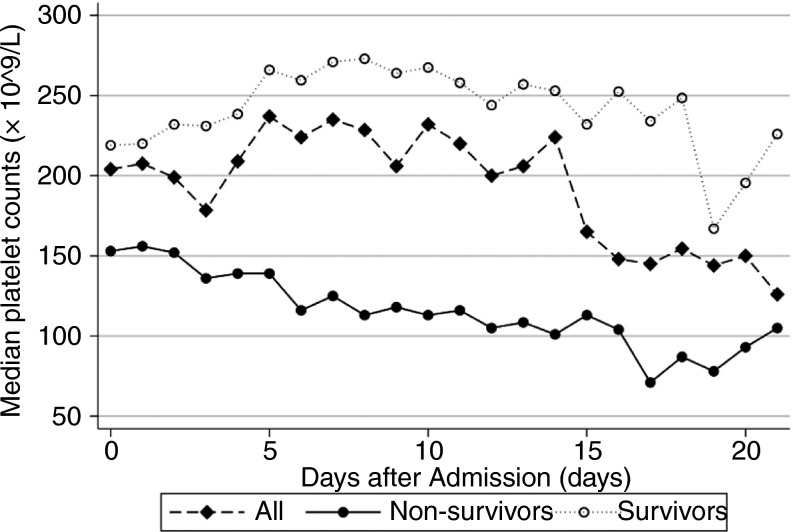

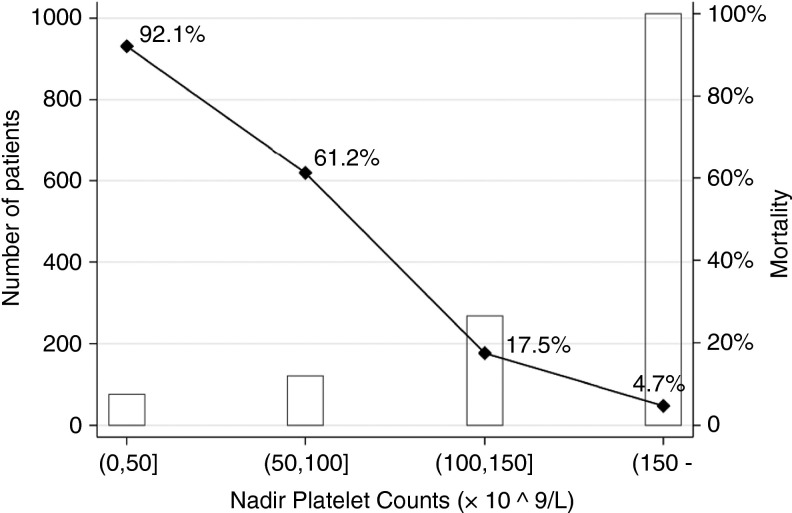

A total of 1476 patients, comprising 1238 (83.9%) survivors and 238 (16.1%) non‐survivors, was included. Their median [IQR] age was 57 [47‐67] years and 776 (52.6%) patients were men. A total number of 4663 tests on platelet count was identified. The sequential changes in platelet counts in the first 3 weeks after admission are presented in Figure 1 . With 125 × 109/L as the lower limit of normal range, thrombocytopenia occurred in 306 (20.7%) patients. As for nadir platelet counts, among predefined groups, the mortality decreased with increasing platelet counts (Figure 2 ).

Figure 1.

The sequential changes in platelet counts among 1476 patients with COVID‐19 in the first 3 weeks after admission. The number of survivors was 1238 and the number of non‐survivors was 238

Figure 2.

Number of patients and mortalities in four groups of patients with COVID‐19 based on their nadir platelet counts

Compared with survivors, non‐survivors were older (67 [IQR, 59‐75] years versus 56 [IQR, 46‐65] years, P < .001), and more were male (65.5% versus 50.0%, P < .001; Table 1 ). Thrombocytopenia was more likely to occur in non‐survivors than in survivors (72.7% versus 10.7%, P < .001). Non‐survivors had significantly lower nadir platelet counts than survivors (79 [43‐129] versus 203 [155 −257], P < .001). When generalized linear modeling was used, the RR of death due to age was 1.03 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.02‐1.04) with every one‐year increase in age (Table 2 ). Compared with females, male patients had a RR of 1.29 (95% CI 1.06‐1.57). With (150‐) as the reference, nadir platelet counts of (100‐150], (50, 100], and (0, 50] had a RR of 3.42 (95% CI 2.36‐4.96), 9.99 (95% CI 7.16‐13.94), and 13.68 (95% CI 9.89‐18.92), respectively.

Table 1.

Differences in age, gender, and tests of platelet count between survivors and non‐survivors of patients with COVID‐19

| Characteristics | Survivors (n = 1238) | Non‐survivors (n = 238) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 56 [46‐65] | 67 [59‐75] | <.001 |

| Male | 620 (50.0%) | 156 (65.5%) | <.001 |

| Number of tests of platelet count | 2 [2‐3] | 4 [2‐8] | <.001 |

| Number of patients with thrombocytopeniaa | 133 (10.7%) | 173 (72.7%) | <.001 |

| Nadir platelet count of each patient | 203 [155‐257] | 79 [43‐129] | <.001 |

Note:Data are expressed as median [interquartile range (IQR)] or count (%).

Normal range was 125 to 350 × 109/L.

Table 2.

Relative risk of death in age, gender, and groups of nadir platelet count in patients with COVID‐19 obtained using a generalized linear model

| Relative risk (95% confidence interval) | P | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.03 (1.02‐1.04) | <.001 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1.29 (1.06‐1.57) | .012 |

| Female | Reference | |

| Nadir platelet count | ||

| (150‐] | Reference | |

| (100‐150] | 3.42 (2.36‐4.96) | <.001 |

| (50, 100] | 9.99 (7.16‐13.94) | <.001 |

| (0, 50] | 13.68 (9.89‐18.92) | <.001 |

In this large‐sample‐sized study we found that 306 (20.7%) had thrombocytopenia and for patients categorized into (0, 50], (50, 100], (100‐150], and (150‐) groups, the mortality was 92.1%, 61.2%, 17.5%, and 4.7%, respectively. After adjusting for age and gender, the trend that in‐hospital mortalities corresponded positively to the magnitude of decrease in platelet count remained.

To our knowledge, this study is the first one specialized in the epidemiology of thrombocytopenia and the association between thrombocytopenia and in‐hospital mortality in patients with COVID‐19. The power of this study relies on its sample size. Even in the (0, 50] group, a total of 76 patients were identified. The cut‐off values to group nadir platelet counts were derived from platelet criterion of sequential organ failure assessment score.9 We did not use 20 × 109/L as a cut‐off value because it would make the number of patients small in both the (0, 20] group and the (20, 50] group.

The proportion of patients with thrombocytopenia was smaller than that of patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). In patients infected by SARS‐CoV, thrombocytopenia was found in 40% to 50% patients.10., 11., 12. SARS‐CoV can induce hematopoiesis after infecting cells in bone marrow. As a coronavirus sharing 79% genomic sequence with SARS‐CoV and the same cell entry receptor of angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2,13 it is possible that SARS‐CoV‐2 may cause thrombocytopenia in a similar way. In a study on coagulopathy associated with COVID‐19, 71.4% (15 in 21) non‐survivors met the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis criteria of disseminated intravascular coagulopathy,14 which may cause increased consumption of platelets. SARS‐CoV‐2 infects and causes diffuse alveolar damage, which entraps megakaryocytes and hinders the release of platelets from megakaryocytes.15

This study has limitations. First, it is a retrospective study and the tests on platelet count for each patient had different time intervals in between. Second, this study was focused on exploring thrombocytopenia, so data on other organ damages were barely mentioned. Third, the medical source was from a relatively short time in the beginning of the COVID‐19 outbreak in Wuhan, China, and this was a single‐centered study. Further studies are needed to confirm our findings.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

X. Yang drafted the manuscript; X. Yang, Q. Yang, X. Wang, Y. Wu, J. Xu, and Y. Yu collected the data; Q. Yang analyzed the data; X. Yang and Y. Shang designed the study.

Footnotes

Xiaobo Yang and Qingyu Yang Contributed equally.

Manuscript handled by: David Lillicrap

Final decision: 14 April 2020

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Situation report ‐ 84. Published April 13th, 2020. Accessed April 13th, 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default‐source/coronaviruse/situation‐reports/20200413‐sitrep‐84‐covid‐19.pdf?sfvrsn=44f511ab_2.

- 2.World Health Organization. Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) and the virus that causes it. Published February 11, 2020. Accessed March 31, 2020. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel‐coronavirus‐2019/technical‐guidance/naming‐the‐coronavirus‐disease‐(covid‐2019)‐and‐the‐virus‐that‐causes‐it.

- 3.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., et al. Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus‐Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China [published online ahead of print 7 February 2020] JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang X., Yu Y., Xu J., et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS‐CoV‐2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single‐centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;2600(20):1–7. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guan W.‐.J., Ni Z.‐.Y., Hu Y., et al. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China [published online ahead of print 28 February 2020] N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi S., Qin M., Shen B., et al. Association of Cardiac Injury With Mortality in Hospitalized Patients With COVID‐19 in Wuhan, China [published online ahead of print 25 March 2020] JAMA Cardiol. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vincent J.L., Moreno R., Takala J., et al. The SOFA (Sepsis‐related organ failure assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the working group on Sepsis‐related problems of the European society of intensive care medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22:707–710. doi: 10.1007/BF01709751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee N., Hui D., Wu A., et al. A major outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(20):1986–1994. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong R.S.M., Wu A., To K.F., et al. Haematological manifestations in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome: retrospective analysis. BMJ. 2003;326(7403):1358–1362. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7403.1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi K.W., Chau T.N., Tsang O., et al. Outcomes and prognostic factors in 267 patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(9):715. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-9-200311040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou P., Yang X.‐.L., Wang X.‐.G., et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang N., Li D., Wang X., Sun Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(4):844–847. doi: 10.1111/jth.14768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mandal R.V., Mark E.J., Kradin R.L. Megakaryocytes and platelet homeostasis in diffuse alveolar damage. Exp Mol Pathol. 2007;83(3):327–331. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]