Abstract

Objective

Advance consent is a recognised method of obtaining informed consent for participation in research, whereby a potential participant provides consent for future involvement in a study contingent on qualifying for the study’s inclusion criteria on a later date. The goal of this study is to map the existing literature on the use of advance consent for enrolment in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) for emergency conditions.

Design

Scoping review designed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses–Extension for Scoping Reviews guidelines.

Data sources

We searched electronic databases including MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science and the Cochrane Register of Clinical Trials from inception to 10 February 2020.

Eligibility criteria

Eligible studies included articles that discussed or employed the use of advance consent for enrolment in RCTs related to emergency conditions. There were no restrictions on the type of eligible study. Data were extracted directly from included papers using a standardised data charting form. We produced a narrative review including article type and authors’ dispositions towards advance consent.

Results

Our search yielded 1039 titles with duplicates removed. Six articles met inclusion criteria. Three articles discussed the theoretical use of research advance directives in emergency conditions; one article evaluated stakeholders’ perceptions of advance consent; and one article described a method for patients to document their preferences for participation in future research. Only one study employed advance consent to enrol participants into a clinical trial for an emergency condition.

Conclusion

Our review demonstrates that there has been minimal exploration of advance consent for enrolment in RCTs for emergency conditions. Future studies could aim to assess the acceptability of advance consent to participants, along with the feasibility of enrolling research participants using this method of consent.

Protocol

The protocol for this scoping review was published a priori.

Keywords: MEDICAL ETHICS, ACCIDENT & EMERGENCY MEDICINE, NEUROLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This scoping review outlines a novel approach to obtaining consent for enrolment in randomised controlled trials.

We systemically summarised the literature using broad inclusion criteria which did not restrict the type of publications included in this scoping review.

This review is limited by there being little literature available on this topic.

Given the heterogeneity of study types included in our analysis, there is inherent risk of bias.

Introduction

Informed consent, in which a patient agrees to participate in research after having received a thorough explanation of the potential risks and benefits, is a fundamental component of modern clinical research. Emergency research presents unique challenges to obtaining informed consent because decision making needs to happen quickly; patients may be incapacitated; and patients and their family members may be severely distressed.1–3 These challenges have been increasingly recognised in the design of trials for emergency neurological conditions such as acute ischaemic stroke and intracerebral haemorrhage, where patients are almost universally incapable of providing consent and enrolment decisions need to happen on a scale of minutes.4 5 Several methods have been employed to try to address the challenge of informed consent in research with incapacitated patients under emergency circumstances. In some instances, patients may be enrolled into randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with consent from a substitute decision maker (SDM).6 Other potential methods of enrolment include waiver of consent and deferral of consent, where a patient is enrolled into a study immediately and efforts are made to obtain consent after the fact, either from the patient or from an SDM.7–9 Availability and acceptability of approaches to consent may vary, depending on legal or cultural factors.6 10 11

Advance consent for enrolment in RCTs for emergency conditions is a potential method to overcome the challenges of obtaining informed consent. Advance consent for research occurs when a potential participant provides consent for future involvement in a study, contingent on qualifying for the study’s inclusion criteria at a later date, for example, when the participant no longer has capacity.12 13 Advance consent may be specific to a particular trial, may detail a patient’s wishes concerning participation in specific types of studies or may be a reflection of values to guide researchers about the patient’s desire to participate in research. American and Canadian guidelines specifically allow for advance consent; the Canadian TCPS2 statement explicitly requires researchers and authorised parties to be guided by these directives’.14 Historically, advance consent has mainly been used for research in predictably progressive diseases, such as Alzheimer’s dementia.15–18 Though advance consent may appear challenging to apply to emergency conditions, given their unpredictable nature, it may be possible to identify patients at risk of suffering from specific emergency conditions based on the presence of recognised risk factors (eg, patients seen in a cardiology clinic with coronary artery disease who are at risk of developing acute coronary syndrome, patients seen in a stroke prevention clinic who are at risk of suffering an acute ischaemic stroke or patients with epilepsy seen in a general neurology clinic who are at risk of presenting with status epilepticus). Inviting them to provide advance consent for research could alleviate many limitations of current consent practices for emergency research.

With these issues in mind, we aimed to review the existing literature on the use of advance consent for enrolment in RCTs for emergency conditions and to secondarily describe the use of advance consent specifically for emergency neurological conditions.

Methods and analysis

We conducted a scoping review to search the literature for experiences with advance consent for participation in RCTs for emergency conditions.19 A detailed protocol of the study design and methods was developed and published a priori.19 This scoping review was designed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses–Extension for Scoping Reviews guidelines.20 It was conducted using the framework of Arksey and O’Malley and further defined by Levac et al.21 22

Information sources and search strategy

We performed a search of MEDLINE, Embase (Embase Classic+Embase), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and Web of Science from inception to 10 February 2020. We developed a structured search strategy in consultation with a health science librarian. Controlled vocabulary and relevant key terms were used. Reference lists of included studies were reviewed for potential inclusion. The full search strategies are outlined in online supplemental table 1.

bmjopen-2022-066742supp001.pdf (69.3KB, pdf)

Eligibility criteria and study selection

Research articles were selected for inclusion if they discussed, in any manner, the use of advance consent for participation in RCTs on emergency conditions and/or treatments. An emergency condition was defined as one that required the initiation of investigations or treatment quickly, including in severely ill hospitalised patients and in the emergency department (ED). We included articles with adult patients 18 year or older, published in English. Articles were not restricted based on study design. Studies focusing on advance care planning in areas other than research, or for research into non-emergency conditions, and those exclusively discussing other variations on informed consent were excluded. Abstracts and letters to the editor were additionally excluded (table 1).

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

| Language | English | Any other language |

| Type of article | RCTs, observational studies, systematic reviews, narrative reviews, surveys, interviews, ethics papers | Letters to the editor, abstracts |

| Age | 18 years or older | Younger than 18 years old |

| Population | Emergency conditions and/or treatment |

|

| Topic of interest | Advance consent for participation in RCTs |

|

RCT, randomised controlled trial.

We used Covidence (Covidence, Melbourne) to screen citations for inclusion at the title, abstract and full-text level.23 Citations were screened independently by at least two trained reviewers (NN and RL). Reviewers met to resolve discrepancies after 25% of the title and abstract citations had been screened. Citations advanced to the next step of review after agreement between the two independent reviewers. Conflicts were resolved by consensus or a third-party independent reviewer (NN and RL). Reference lists of included full-text articles were reviewed for further relevant publications.

Data extraction and charting

We retrieved the full texts of included studies, and the data were extracted by two independent reviewers (NN and RL) onto a standardised data charting form (online supplemental table 2). Conflicts were resolved by consensus. Descriptive data were extracted on the article and author including the journal title, year of publication, type of author (MD, PhD or other) and publication country of origin. Data on the paper characteristics, methodology, medical condition of interest and method of employing advance consent for research were also obtained. Specifically, we extracted the type of research paper, the medical condition of focus, whether the medical condition was neurological, the author’s position on the use of advance consent for research, and any statements explaining how advance consent was used or discussed in the paper. If the paper was a clinical study, we recorded whether advance consent was used to enrol participants.

Analysis

Given the anticipated heterogeneity of study methodology and expected varying use of advance consent in eligible studies, we performed a narrative review with descriptive analysis. Data were synthesised with thematic grouping. Quantitative analysis was not planned.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not directly involved in the design or dissemination plan of this research project.

Results

Search results

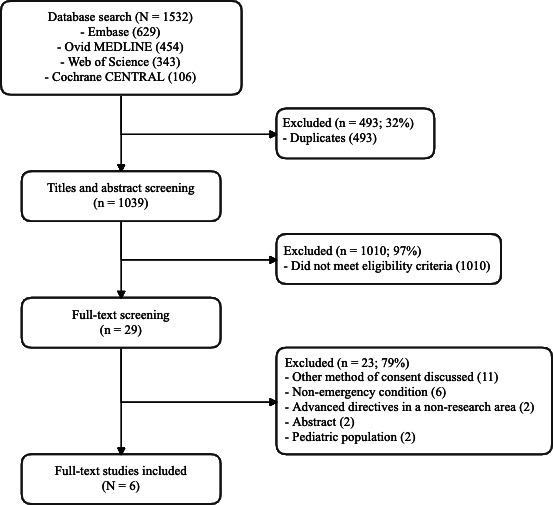

Our electronic database searches yielded 1532 studies. With duplicates removed, 1039 titles and abstracts were screened, and 29 full-text articles were reviewed. No additional publications were included after reviewing the reference lists. Six articles met the inclusion criteria (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram.

Article characteristics

The six articles were published from 1995 to 2019. All of the articles were from the USA. They were heterogeneous in their methodologies, medical conditions studied, and methods of using, evaluating or describing advance consent for research. Two of the articles were commentaries24 25; one was a consensus statement26; one consisted of semistructured interviews27; one was a historical review28; and one was a cohort study.29 Specific conditions addressed included acute psychiatric illnesses (n=2),24 29 pneumonia (n=1)27 and stroke (n=1).25 Two articles did not mention specific conditions26 28 but rather addressed emergency conditions in general. Three articles discussed the theoretical use of research advance directives in emergency conditions.24 26 28 One article used semistructured interviews to determine stakeholders’ perceptions of the use of advance consent for enrolment in an RCT for the treatment of pneumonia.27 One article described a method for patients to document their preferences for participation in future research as part of a broader approach to advance directive for patients who had a stroke but did not elaborate on advance consent specifically.25 Only one study reported using advance consent to enrol participants into a clinical trial (table 2).29

Table 2.

Characteristics of included articles

| Author | Year | Country | n | Type of article | Condition | Description of use of advance consent |

| Backlar24 | 1999 | USA | 369 | Commentary | Psychiatric: schizophrenia | Author discusses the theoretical use of research advance directives. |

| Biros et al26 | 1995 | USA | 303 | Consensus statement | No specific condition mentioned: ‘emergency conditions’ | Authors discuss the theoretical use of research advance directives in the context of federal regulations in the USA. |

| Cole et al29 | 2019 | USA | 1165 | Cohort | Psychiatric: agitation | Authors employ the use advance consent for enrolment in an randomised controlled trial. Observational cohort study of patients screened and who consented in advance for potential future enrolment in a randomised trial examining treatments for acute agitation in the emergency department. |

| Corneli et al27 | 2018 | USA | 1095 | Interview | Respiratory: pneumonia | Authors interview stakeholders to determine the perceived acceptability of the use advance consent for enrolment in a theoretical RCT. |

| Karlawish et al28 | 1997 | USA | 340 | Historical review | No specific condition mentioned: emergency medicine | Authors explain research advance directives and discuss the ethics and regulations in the USA concerning the use of advance consent for research on emergency conditions. |

| McGehrin et al25 | 2018 | USA | 811 | Commentary | Neurological: ischaemic stroke | Authors outline the use of a standardised document which allows patients to record their preferences regarding acute stroke treatment interventions, as well as for preferences for participation in future stroke clinical trials. |

Arguments for and against the use of advance consent for research

Three articles expressed opinions in favour of using advance consent for research24 25 27; two were critical of its use26 29; and one did not mention an opinion (table 3).28 The arguments in favour of advance consent were that it is acceptable to patients27 and that it enhances patient autonomy.24 25 The arguments against advance consent were that it was not feasible,26 29 that participants would not be adequately informed26 and that it would not protect patients from the risks of participation in RCTs.26 29 One article did not mention an opinion regarding the use of advance consent for research and instead defined research advance directives, discussed the ethical considerations and outlined the current regulations in the USA.28

Table 3.

Author’s disposition on the use of advance consent for research

| Author | Author’s disposition | Description of supporting evidence |

| Backlar24 | In favour of use of advance consent for research | The author reasons that ‘substantive and procedural research advance directives allow potential subjects to make a choices of their own as to whether they wish to be enrolled and participate in a research protocol, to appoint a surrogate decision maker of their own choosing, and to additionally spell out specific safeguards’ and that ‘research advance directives provide potential subjects with the opportunity not only to make choices of their own but provide a mechanism that guarantees them a cluster of important protections’. |

| Biros et al26 | Against use of advance consent for research | The authors contend that ‘patients may not consider consent carefully when the changes of entry into a specific study are remote. Thus, they may not be adequately protected from research risks’. Regarding advance consent at hospital admission for a potential future research protocol, the authors argue that preconsent ‘cannot be used for emergency research in the prehospital setting or for studying the treatment of acute illnesses that occur in the out-of-hospital setting’. Regarding obtaining advance consent from unaffected subjects who may require emergency care in the future, the authors argue that ‘identifying those patients who have previously consented may not be feasible when the critical situation occurs’. |

| Cole et al29 | Against use of advance consent for research | The authors screened 1461 patients for their RCT on loxapine versus IM haloperidol+lorazepam for treatment of acute agitation in the ED secondary to bipolar disorder type 1 or schizophrenia. ‘Despite screening >1400 patients and obtaining preconsent in 43 patients’, not a single patient was enrolled using preconsent methods. Only two patients were enrolled in the study, and the study was terminated 1 month after enrolment of the first patient due to loss of funding. The article concludes that the use of preconsent in their study was ‘found to be infeasible’. |

| Corneli et al27 | In favour of use of advance consent for research | Structured interviews detail that ‘patients and caregivers expressed no concerns about being approached in the ICU about a clinical trial on treatment for pneumonia before the patient was diagnosed with the condition’ and that ‘the IRB representatives expressed no ethical or regulatory concerns with the early enrollment strategy using advance consent’. The article concludes that ‘early enrollment strategy with advance consent appears to be an acceptable approach among key stakeholders’. |

| Karlawish et al28 | No opinion for or against the use of advance consent for research | The authors outline that ‘advance informed consent means, that at a time before enrollment, an investigator seeks the consent of a competent person who is a potential subject of a research trial.(…)Like advance directives for clinical care such as living wills, regulations could endorse advance directives for research’. They then explain that ‘a moral conflict can occur when an advance directive conflicts with substituted judgement or best interests principles’ and that ‘there are the practical limits, including that an advance directive cannot address every circumstance a potential subject faces and that many people do not execute them’. |

| McGehrin et al25 | In favour of use of advance consent for research | The article states that ‘one solution to preserving patient autonomy in acute stroke care is the advent of a stroke advance directive. An advance directive for acute stroke therapy was created at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) in 2015 titled COAST (Coordinating Options for Acute Stroke Therapy). This 4-page form allows patients to document their preferences regarding acute stroke treatment interventions, as well as participation in clinical stroke trials, in a nonurgent setting and in advance of a potential stroke’. |

ED, emergency department; IM, intramuscular; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Experiences with advance consent

Corneli et al was the only study to report the results of empirical research in that they conducted semistructured interviews with 52 stakeholders, including patients, caregivers, institutional review board representatives, clinical investigators and study coordinators, about advance consent.27 Stakeholders, including patients and caregivers, reported no concerns about being approached in advance regarding participation in a research study prior to developing the condition required for in enrolment, in this case, pneumonia. The authors therefore concluded that an early enrolment strategy with advance consent would be acceptable.

Cole et al presented the sole experience using advance consent for study enrolment.29 The authors conducted an observational cohort study of psychiatric participants preconsented for an RCT examining treatments for acute agitation in the ED. Eligible participants provided informed consent for enrolment in the RCT, which involved having a drug administered for agitation in the event that they would present to the ED within the next 3 years with acute agitation. Potential participants could also be consented for the trial in real time, if they retained capacity to provide informed consent or if a legally authorised representative was present to provide consent. Over 1000 patients were screened for the study, and only 75 were found to be eligible to provide advance consent, 43 of whom did provide advance consent. No participant was enrolled into the study via advance consent, and only two participants were successfully enrolled into the trial by other methods of consent. The trial was terminated early, 1 month after enrolling its first patient, due to loss of funding. Given that no participant was enrolled by advance consent, the authors concluded that it was not a feasible approach to study enrolment.

Advance consent and emergency neurological conditions

The article by McGehrin et al was the only paper that specifically focused on neurological conditions. McGehrin et al proposed a four-page advance directive document they call ‘Coordinating Options for Acute Stroke Therapy’, which is designed to allow patients to document their preferences regarding acute stroke treatment, including participation in future clinical stroke trials.25 The article did not describe what information would be recorded regarding preferences for involvement in future stroke trials, nor did it detail how this information would be used for future enrolment in research studies.

Discussion

Our scoping review maps the existing literature on the use of advance consent for enrolling participants into RCTs for emergency conditions. The results of our review demonstrate that there has been minimal exploration of the use of advance consent for enrolment in RCTs for emergency conditions. We could only identify one study that had attempted the use of advance consent in an adult population29 and one study in which opinions about advance consent were elicited.27 No studies had endeavoured to use advance consent for enrolment into research in emergency neurological conditions.

The limited literature on the use of advance consent may suggest that there are concerns surrounding feasibility, but we believe the issues raised by Cole et al and Biros et al are potentially remediable.26 29 For example, selecting conditions for which a clearly defined at-risk population exists, such as acute ischaemic stroke, would likely enhance feasibility. A recent assessment of local data at a tertiary care centre in Ottawa (Ontario, Canada) also supports the feasibility of advance consent in selected at-risk populations, in this case neurological emergencies. The data established that 5%–7% of patients seen in the stroke prevention clinic with minor stroke or transient ischaemic attack presented to the ED with an acute stroke within 1 year of their clinic appointment. These data reflect a potential 100–150 candidates annually who could be consented in clinic using advance consent methods for RCTs pertaining to acute ischaemic strokes in the ED .30 Moreover, an electronic medical record could be used to document decisions about advance consent in such a way that it is obvious on presentation to the ED. Because the study by Cole et al failed to enrol a patient using advance consent, they conclude that the approach is not feasible; we believe it is important to note that they struggled to enrol patients into their study by any means and that this is unlikely owing simply to the use of advance consent. Biros et al raise an important concern about patients being unable to consider consent carefully when potential enrolment is remote. However, Corneli et al directly addressed this issue in their survey and found that nearly all patient and caregiver respondents were not concerned about a patient’s ability to understand consent information for a potential future trial.

Given the little experience with advance consent we were able to identify in this scoping review, many details regarding the practical application of advance consent could not be developed in detail through our search. First, should advance consent be tied to a particular trial protocol only, or should be it be more general and applicable to any available research trial for which a patient may be eligible? While the concept of general or ‘broad’ consent is known in clinical research, it has tended to be used in relation to the future study of tissue samples. It remains to be seen whether physicians, participants, and regulators will feel comfortable with general advance consent (eg, a patient who consents to participate in any acute stroke trial) as a stand-in for specific informed consent (eg, a specific stroke trial). Second, how would advance consent from an incapable patient be prioritised if that patient’s substitute decision maker objects to trial participation? We would expect that a legal, signed, informed consent document from an incapable patient would be considered valid in most legal jurisdictions, even if a legally authorised representative is available. Such an eventuality could in fact be written into an advance consent document. Importantly, it must also be noted that a patient has the right to decline participation in advance and that such an advance decision should also be respected in the event that they are eligible for participation in a trial. Ultimately, practice regarding some of these issues will be determined by individual jurisdictions’ legal standards, which vary quite significantly from country to country, and sometimes even within countries.

The strengths of our review are that we prospectively registered our study, used a thorough protocol, and systematically searched, screened and summarised the literature on advance consent for research in acute care RCTs. We also employed broad inclusion criteria, which did not restrict the type of included publications in our review. This ensured that we were able to survey all of the available literature on our topic of interest. Our study was not without limitations. Despite our comprehensive search strategy, there was little literature on this topic, and due to the heterogeneity of study types ultimately included in our analysis, there is inherent risk of bias. Because we conducted a scoping review, we did not perform a specific risk of bias assessment of each individual manuscript identified and data synthesis was not performed.

Ultimately, we suspect that advance consent could offer several important advantages over existing trial recruitment methods. Most importantly, advance consent could create a more ethical system for trial enrolment by ensuring that patients’ wishes to be enrolled or not enrolled into trials are respected even if they cannot express them at the time of a medical emergency. Advance consent could reduce the time required to enrol willing patients into trials of time-sensitive treatments, potentially leading to better individual outcomes. It could render research findings more generalisable by removing biases against more severely affected patients or non-accompanied patients. It could even allow RCTs to be completed more quickly, as enrolment rates may be enhanced, leading to a more rapid determination of research results. Future studies could aim to assess the acceptability of advance consent to potential participants, along with the feasibility of enrolling potential research participants using this method of consent.

In summary, our scoping review demonstrates that there has been minimal exploration on the use of advance consent for enrolment in RCTs for emergency conditions, and significant gaps in the literature remain. Furthermore, there have been no studies assessing the use of advance consent for enrolment in RCTs involving neurological emergencies. Patients and caregivers appear open to participate in advance consent for emergency conditions.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors made substantial contributions to the manuscript. NN, BD, JP, DD and MS designed the research question. NN, BD and MS designed the eligibility criteria and the screening strategy. BD, DD and MS designed the search strategy. NN, RL, BD and MS came up with the data extraction items and developed the data synthesis strategy. All authors contributed to analysis, drafting and editing and provided final approval. MS acts as the guarantor for the study.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Dickert NW, Brown J, Cairns CB, et al. Confronting ethical and regulatory challenges of emergency care research with conscious patients. Ann Emerg Med 2016;67:538–45. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.10.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mangset M, Førde R, Nessa J, et al. I don’t like that, it’s tricking people too much… acute informed consent to participation in a trial of thrombolysis for stroke. J Med Ethics 2008;34:751–6. 10.1136/jme.2007.023168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wendler D, Dickert NW, Silbergleit R, et al. Targeted consent for research on standard of care interventions in the emergency setting. Crit Care Med 2017;45:e105–10. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goyal M, Demchuk AM, Menon BK, et al. Randomized assessment of rapid endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1019–30. 10.1056/NEJMoa1414905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shamy MCF, Dewar B, Chevrier S, et al. Deferral of consent in acute stroke trials. Stroke 2019;50:1017–20. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.024096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burns KEA, Zubrinich C, Marshall J, et al. The “ consent to research ” paradigm in critical care: challenges and potential solutions. Intensive Care Med 2009;35:1655–8. 10.1007/s00134-009-1562-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.61 21 CFR part 50. protection of human subjects: informed consent and waiver of consent requirements in certain emergency research; final rules. Food and Drug Administration; Federal Register 1996:51498–2332.10161558 [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Medical Association . The declaration of helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects 2008. n.d. Available: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Beauchamp TL, Fost N, Robertson JA. The ambiguities of “deferred consent.” IRB 1980;2:6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Belle G, Mentzelopoulos SD, Aufderheide T, et al. International variation in policies and practices related to informed consent in acute cardiovascular research: results from a 44 country survey. Resuscitation 2015;91:76–83. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.11.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bravo G, Dubois M-F, Wildeman SM, et al. Research with decisionally incapacitated older adults: practices of canadian research ethics boards. IRB 2010;32:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Largent EA, Wendler D, Emanuel E, et al. Is emergency research without initial consent justified?: the consent substitute model. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:668–74. 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saks ER, Dunn LB, Wimer J, et al. Proxy consent to research: the legal landscape. Yale J Health Policy Law Ethics 2008;8:37–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Government of Canada . Tri-council policy statement on ethical conduct for research involving human. Section 2016;3:11. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sachs GA. Advance consent for dementia research. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1994;8(Suppl. 4):19–27. 10.1097/00002093-199400000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buller T. Advance consent, critical interests and dementia research. J Med Ethics 2015;41:701–7. 10.1136/medethics-2014-102024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stocking CB, Hougham GW, Danner DD, et al. Speaking of research advance directives: planning for future research participation. Neurology 2006;66:1361–6. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000216424.66098.55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pierce R. A changing landscape for advance directives in dementia research. Soc Sci Med 2010;70:623–30. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Niznick N, Lun R, Dewar B, et al. Advanced consent for participation in acute care randomised control trials: protocol for a scoping review. BMJ Open 2020;10:e039172. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-scr): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467–73. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010;5:69. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Covidence systematic review software . Veritas health innovation melbourne, australia. n.d. Available: www.covidence.org

- 24.Backlar P. A choice of one’s own research advance directives: anticipatory planning for research subjects with fluctuating or prospective decisionmaking impairments. Account Res 1999;7:117–28. 10.1080/08989629908573946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGehrin K, Spokoyny I, Meyer BC, et al. The coast stroke advance directive: a novel approach to preserving patient autonomy. Neurol Clin Pract 2018;8:521–6. 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Biros MH, Lewis RJ, Olson CM, et al. Informed consent in emergency research. JAMA 1995;273:1283. 10.1001/jama.1995.03520400053044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corneli A, Perry B, Collyar D, et al. Assessment of the perceived acceptability of an early enrollment strategy using advance consent in health care-associated pneumonia. JAMA Netw Open 2018;1:e185816. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.5816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karlawish JH, Sachs GA. Research on the cognitively impaired: lessons and warnings from the emergency research debate. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997;45:474–81. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb05174.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cole JB, Klein LR, Mullinax SZ, et al. Study enrollment when “ preconsent ” is utilized for a randomized clinical trial of two treatments for acute agitation in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2019;26:559–66. 10.1111/acem.13673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shamy M, Dewar B, Niznick N, et al. Advanced consent for acute stroke trials. Lancet Neurol 2021;20:170.:S1474-4422(21)00029-6. 10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00029-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-066742supp001.pdf (69.3KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study.