Abstract

OBJECTIVE.

To determine the impact of total household decolonization with intranasal mupirocin and chlorhexidine gluconate body wash on recurrent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection among subjects with MRSA skin and soft-tissue infection.

DESIGN.

Three-arm nonmasked randomized controlled trial.

SETTING.

Five academic medical centers in Southeastern Pennsylvania.

PARTICIPANTS.

Adults and children presenting to ambulatory care settings with community-onset MRSA skin and soft-tissue infection (ie, index cases) and their household members.

INTERVENTION.

Enrolled households were randomized to 1 of 3 intervention groups: (1) education on routine hygiene measures, (2) education plus decolonization without reminders (intranasal mupirocin ointment twice daily for 7 days and chlorhexidine gluconate on the first and last day), or (3) education plus decolonization with reminders, where subjects received daily telephone call or text message reminders.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES.

Owing to small numbers of recurrent infections, this analysis focused on time to clearance of colonization in the index case.

RESULTS.

Of 223 households, 73 were randomized to education-only, 76 to decolonization without reminders, 74 to decolonization with reminders. There was no significant difference in time to clearance of colonization between the education-only and decolonization groups (log-rank P =.768). In secondary analyses, compliance with decolonization was associated with decreased time to clearance (P = .018).

CONCLUSIONS.

Total household decolonization did not result in decreased time to clearance of MRSA colonization among adults and children with MRSA skin and soft-tissue infection. However, subjects who were compliant with the protocol had more rapid clearance.

The incidence of community-onset Staphylococcus aureus skin and soft-tissue infections (SSTI) has increased in recent years, with the majority caused by methicillin-resistant strains.1–3 S. aureus colonizes several anatomic sites, including the anterior nares,4 throat,5 axillae,6 groin,7 rectum,6 and skin wounds.8 Previous studies have demonstrated that colonization with methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) is linked to acute infection in approximately 25% of patients.9–13 Notably, more than half of patients with MRSA SSTI develop recurrent infections within 1 year.10,14–16 As a result, several decolonization strategies have been used to try to decrease MRSA colonization and reduce the burden of subsequent infection. Topical mupirocin has been shown to effectively eradicate S. aureus nasal colonization17 and is often a component of decolonization protocols. However, given the presence of MRSA in dermatologic sites, antiseptic body washes, such as chlorhexidine, hexachlorophene, or bleach baths, have also been utilized. There is great variability among practitioners regarding prescription of decolonization strategies, timing of decolonization, decolonization of household members, and choice of agents.18 Furthermore, MRSA eradication in individuals has not been shown to decrease recurrent infections among those colonized or their close contacts,19 perhaps related to recurrent transmission of MRSA among close contacts.

MRSA transmission among household members is common.20,21 Previous studies have demonstrated that the presence of colonization with MRSA among household members results in prolonged duration of MRSA colonization in index cases.22–24 Failure to eradicate MRSA colonization among household members may increase risk of persistent or recurrent colonization and subsequent reinfection.25–28 However, the ideal strategies for management of household MRSA colonization require further study. Therefore, the objective of this study was to determine the impact of total household decolonization with intranasal mupirocin and chlorhexidine gluconate (CHG) body wash on recurrent MRSA infections. Secondarily, we sought to determine time to clearance of colonization among subjects initially presenting with MRSA SSTI. Although the primary outcome of the original protocol was recurrent infection, there were very few outcomes in any of the intervention groups. Therefore, this article focuses on the secondary outcome of interest, clearance of colonization.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

We conducted a 3-arm, nonmasked randomized controlled trial to assess the impact of total household decolonization on recurrent infection among subjects presenting with MRSA SSTI. The study was performed from November 1, 2011, through May 31, 2013, at 5 academic medical centers in Southeastern Pennsylvania: the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, a 782-bed adult acute care hospital; Penn Presbyterian Medical Center, a 300-bed adult acute care hospital; Pennsylvania Hospital, a 500-bed adult community hospital; Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, a 520-bed children’s hospital; and Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, a 551-bed adult and pediatric hospital. Adults and children aged at least 6 months presenting to the emergency departments or primary care settings at any of the 5 study sites with an acute SSTI for which a microbiologic sample was sent were approached for entry. Additionally, patients hospitalized for 14 days or fewer with an acute SSTI and who had a wound swab sent for microbiologic culture within the first 72 hours were also approached. Eligible subjects were those whose culture subsequently grew MRSA. To be enrolled, the study subject (ie, index case) and all members of his/her household were required to participate. Each household was enrolled only once. Informed consent or assent was obtained from all index cases and household members. This study was approved by the institutional review boards of all participating institutions. A Data Safety Monitoring Board oversaw study conduct and reviewed safety data at the midpoint of the study period.

Interventions and Randomization

Enrolled households were randomized to 1 of 3 intervention groups: (1) education, (2) education plus decolonization without reminders, and (3) education plus decolonization with reminders. The educational intervention included 10 minutes of face-to-face instruction by a study staff member and written materials29 (Supplementary Appendix 1), which were reviewed with all site coordinators to ensure consistency. The education focused on personal hygiene (eg, hand hygiene and bathing), interrupting transmission (eg, avoidance of shared towels), and household hygiene (eg, regular washing of linens and towels). The decolonization protocol was as follows: (1) 2% mupirocin ointment applied inside both nares twice daily for 7 days, and (2) a 4% CHG (Hibiclens; Mölnlycke Health Care) body wash, including entire skin surface, excluding face and hair, with particular attention to axillae, inguinal, and perirectal areas, performed on the first and last day of mupirocin use. Subjects were asked to record performance of each step of the protocol in a journal, which was returned at the end of the period of medication use, along with any unused portion of the agents. The subjects randomized to decolonization without reminders were instructed on the decolonization protocol during the initial visit. Those randomized to decolonization with reminders also received daily phone calls or text messages during the decolonization protocol period to remind them to perform the indicated procedures.

Households were randomized using block randomization with randomly varying block sizes. Treatment allocations were assigned 1:1:1 on the basis of a random number generator and the allocation was placed in a sealed envelope that was opened only after the full household was consented.

Longitudinal Follow-Up, Outcomes, and Data Collection

After randomization and performance of the decolonization protocol (for treatment groups), index cases and all household members performed self-sampling for MRSA from 3 anatomic sites (nares, axillae, groin) every 2 weeks for 6 months. Multiple anatomic sites were chosen for sampling in order to maximize the sensitivity of detection of MRSA colonization.30,31 The ESwab System (Copan Diagnostics) was used for all sample collections. Subjects obtained specimens by placing a swab in both nares; they then placed a second swab in both axillae followed by both groin creases. If the initial skin lesion was present, that site was sampled with a third swab. The swab specimens were mailed to the study laboratory. Subjects returned the first swab within 7–14 days after completing the decolonization protocol. Research staff demonstrated the method for sampling each anatomic site and also provided an information sheet with these instructions at the enrollment visit. For children unable to self-collect specimens, parents/guardians were instructed to perform the sampling. Of note, self-collection of swabs has proven highly sensitive compared with swabs collected by research staff.32

The primary end point was recurrent MRSA infection in the index case (ie, the subject presenting with MRSA SSTI). The secondary end point was time to clearance of MRSA colonization. The following data elements were collected on index cases and household members through the initial home visit interview and confirmed or expanded via review of medical and prescription records: demographic data; medical history, including comorbidities and medications; number of people in the household; and, for index cases only, antibiotic use during the year prior to diagnosis of SSTI (pretreatment), the 14 days following SSTI diagnosis (treatment), and the period after treatment through end of follow-up (posttreatment). Antibiotic use in the 14 days prior to SSTI diagnosis was not included because this was assumed to be empirical treatment for the presenting infection. For the primary end point, index cases were asked to report any recurrent skin infections during the follow-up period. These were reported via biweekly data collection forms that were to be mailed in along with the swab samples. Additionally, house visits were performed halfway and at the end of the follow-up period to confirm and expand information submitted on the forms.

Laboratory Testing

Swab samples were plated to BBL ChromAgar MRSA (BD) and processed according to manufacturer’s instructions.33 Susceptibility testing of isolates was performed using the Vitek 2 automated identification and susceptibility testing system with Advanced Expert System (bioMérieux) and interpreted according to established criteria.34 Isolates that were erythromycin-resistant but clindamycin-susceptible were routinely tested for inducible macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin resistance by the disk diffusion method (D-test).34

Data Analysis

For the primary analysis, subjects who received the education intervention only were compared with those who underwent decolonization (ie, combined subjects who underwent decolonization with and without reminders). The primary analysis was performed as a modified intention-to-treat analysis. A per-protocol analysis was also performed, excluding subjects in the intervention arms who were not compliant with the decolonization protocol. Compliance was defined in 2 ways using self-report (ie, journals): (1) 100% compliance with both mupirocin (14 doses) and CHG (2 doses), and (2) at least 50% compliance with both mupirocin (≥7 doses) and CHG (≥1 dose). We conducted secondary analyses to account for the effect of varying degrees of compliance with the decolonization protocol by examining study cohorts with 50% and 100% compliance. For these analyses, subjects in the education group were considered to have 0% compliance, along with subjects in the intervention arms who did not meet the definitions of 50% and 100% compliance. Index cases who were prescribed a decolonization agent as part of their care during the 14 days after diagnosis of SSTI were excluded from these secondary analyses. Missing data were accounted for using 2 methods, via sensitivity analyses. In 1 analysis, households with any missing compliance data were excluded; in a second analysis, missing compliance data was regarded as noncompliance.

Subjects were presumed to be colonized with MRSA at the date of enrollment. Clearance of colonization was defined as 2 consecutive sampling periods with no MRSA-positive surveillance cultures. The clearance date was then considered to be the midpoint between the date of the last positive surveillance culture and the date of the first negative culture. Study groups were compared on the basis of demographic, comorbidity, household, and antibiotic use characteristics using χ2 or Fisher exact test for categorical variables and t test or Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables, as appropriate. Median time to clearance of colonization with MRSA was determined using a Kaplan-Meier estimate. The difference in time to clearance of colonization between groups was measured using the log-rank test. A Cox proportional hazards model was developed to adjust for any potential confounding variables, including household size.

For all calculations, a 2-tailed P < .05 was considered to be significant. Statistical calculations were performed using commercially available software (SAS, version 9.3 [SAS Institute]).

RESULTS

Of 223 enrolled households, 73 were randomized to education only, 76 to decolonization without reminders, and 74 to decolonization with reminders (Figure 1). Of these, 52 (71%), 48 (63%), and 49 (66%) index cases, respectively, returned swabs for at least the first 2 consecutive sampling periods (thus permitting calculation of duration of colonization). Therefore, 149 households were included in the modified intention-to-treat analysis, which consisted of 149 index cases and 537 household members. There were no statistical differences between the included and excluded subjects with respect to demographic characteristics and comorbidities. Median duration of follow up for index cases and household members was 91 days (interquartile range, 48–151 days) and 114 days (79–184 days), respectively. Index cases returned swab samples for a median of 6 (interquartile range, 3–10) sampling episodes (of possible 14), whereas household members returned samples for a median of 7 (4–11). There were no substantive differences in baseline characteristics between the study groups (Table 1). Index cases in the decolonization groups (group 2 and group 3) received clindamycin as treatment for the MRSA SSTI more commonly (62.9% vs 50%) and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole less commonly (30.9% vs 40.4%) than those in the education group (Supplementary Table 1). There were no serious adverse events in any of the 3 study groups.

FIGURE 1.

Participants in study of the effect of total household decolonization on clearance of colonization with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics in Study of the Effect of Total Household Decolonization on Clearance of Colonization With Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus

| Variable | Group 1: education only (N = 52) |

Group 2: decolonization without reminders (N = 49) |

Group 3: decolonization with reminders (N = 48) |

Groups 2 & 3: decolonization (N = 97) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 25.3 (24.3) | 23.2 (18.9) | 25.5 (20.6) | 24.4 (19.7) |

| Age ≥18 y | 24 (46.2) | 24 (49.0) | 24 (50.0) | 48 (49.5) |

| Female sex | 31 (59.6) | 25 (51.0) | 28 (58.3) | 53 (54.6) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 18 (34.6) | 22 (44.9) | 13 (27.1) | 35 (36.1) |

| Black/African-American | 29 (55.8) | 26 (53.1) | 30 (62.5) | 56 (57.7) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0) | 2 (4.2) | 2 (2.1) |

| Asian | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.1) | 1 (1.0) |

| Mixed race or other | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.1) | 1 (1.0) |

| Site of enrollment | ||||

| HUP | 13 (25.0) | 13 (26.5) | 12 (25.0) | 25 (25.8) |

| PPMC | 5 (9.6) | 4 (8.2) | 2 (4.2) | 6 (6.2) |

| PAH | 2 (3.8) | 3 (6.1) | 6 (12.5) | 9 (9.3) |

| CHOP | 26 (50.0) | 25 (51.0) | 25 (52.1) | 50 (51.5) |

| HMC | 6 (11.5) | 4 (8.2) | 3 (6.3) | 7 (7.2) |

| Departmenta | ||||

| Emergency department | 37 (71.2) | 37 (75.5) | 32 (68.1) | 69 (71.9) |

| Outpatient | 9 (17.3) | 8 (16.3) | 14 (29.8) | 22 (22.9) |

| Inpatient | 6 (11.5) | 4 (8.2) | 1 (2.1) | 5 (5.2) |

| Household size | ||||

| 1 | 2 (3.8) | 5 (10.2) | 4 (8.3) | 9 (9.3) |

| 2 | 9 (17.3) | 5 (10.2) | 7 (14.6) | 12 (12.4) |

| 3 | 5 (9.6) | 9 (18.4) | 10 (20.8) | 19 (19.6) |

| 4 | 14 (26.9) | 10 (20.4) | 6 (12.5) | 16 (16.5) |

| 5 | 6 (11.5) | 9 (18.4) | 7 (14.6) | 16 (16.5) |

| >5 | 16 (30.8) | 11 (22.4) | 14 (29.2) | 25 (25.8) |

| Medical comorbiditiesa | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 7 (13.5) | 3 (6.3) | 8 (16.7) | 11 (11.5) |

| Hepatic dysfunction | 4 (7.7) | 2 (4.2) | 2 (4.2) | 4 (4.2) |

| Renal dysfunction | 3 (5.8) | 3 (6.3) | 0 (0) | 3 (3.1) |

| Malignancy | 3 (5.8) | 1 (2.1) | 2 (4.2) | 3 (3.1) |

| Organ transplant | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.1) | 1 (1.0) |

NOTE. Data are no. (%) of patients, unless otherwise indicated. CHOP, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia; HMC, Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center; HUP, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania; PAH, Pennsylvania Hospital; PPMC, Penn Presbyterian Medical Center.

Percentages calculated using incomplete data available for various subgroups.

Modified Intention-to-Treat Analysis

There were 5 reported subsequent infections among index cases, 4 of which were confirmed to be MRSA infections (1 in the education group and 3 in the decolonization groups; P = .122). Median time to clearance of MRSA colonization was 19 days (95% CI, 15–33 days) for the education-only group and 23 days (17–29 days) for the groups who underwent decolonization (log-rank P = .768) (Figure 2). Using a Cox proportional hazards model to adjust for the differences in antibiotic treatment between the groups and household size, there was still no significant effect of decolonization on duration of colonization (Table 2). There were no significant differences in time to clearance of MRSA colonization between the education-only group and those who underwent decolonization with or without reminders (log-rank P =.811) (Supplementary Figure 1). There was no effect modification by age (P = .985). Approximately 20% of index cases remained colonized at the end of the study period, regardless of group.

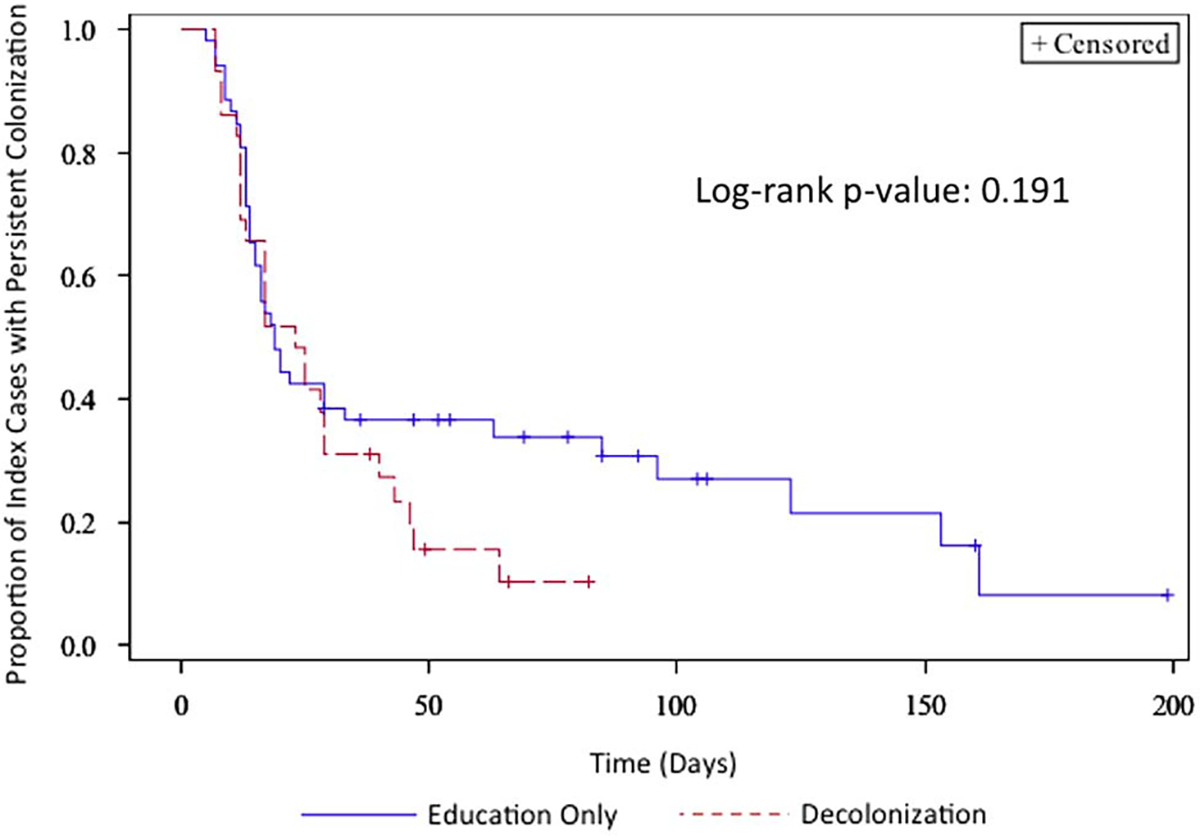

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve of time to clearance of colonization: education-only vs decolonization.

TABLE 2.

Cox Proportional Hazards Model of Time to Clearance of MRSA Colonization

| Group | HR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Education | 1.00 [Reference] | … |

| Decolonization (combined) | 0.92 (0.61–1.37) | .667 |

| Treatment with clindamycin | 2.53 (1.60–4.00) | <.001 |

| Treatment with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | 1.29 (0.83–2.12) | .254 |

| Household size | 1.04 (0.96–1.11) | .331 |

NOTE. HR, hazard ratio; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

Per-Protocol Analysis

Full compliance data were available for 126 households (84.6%). Fifteen index cases (10%) had a prescription from their treating physician for mupirocin, CHG, or bleach baths/body wipes in the 14 days following diagnosis of SSTI. In the per-protocol analysis, households with incomplete compliance data and those with index cases who were prescribed decolonization agents by their providers (ie, not part of the study) were excluded. Those index cases whose households reported 100% compliance (29 [26.1%] of 111 subjects) with the decolonization strategies had a median time to clearance of colonization of 23 days (95% CI, 12–29 days), compared with the education-only group, who had a median time to clearance of colonization of 19 days (15–33 days; log-rank P = .191) (Figure 3). When comparing those with at least 50% compliance (63 [56.8%] of 111 subjects) to index cases in households with education as the intervention, the index cases also had similar median time to clearance of MRSA colonization (23 days [95% CI, 17–29 days] vs 19 days [15–33 days]; log-rank P = .545) (Supplementary Figure 2). There was no significant difference in compliance between adults and children (ie, <18 years of age) (data not shown). Eleven households consisted only of the index case. Sensitivity analyses of both modified intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses were performed excluding those households and results did not differ (data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

Kaplan-Meier curve of time to clearance of colonization: education-only vs 100% compliance with decolonization (per-protocol).

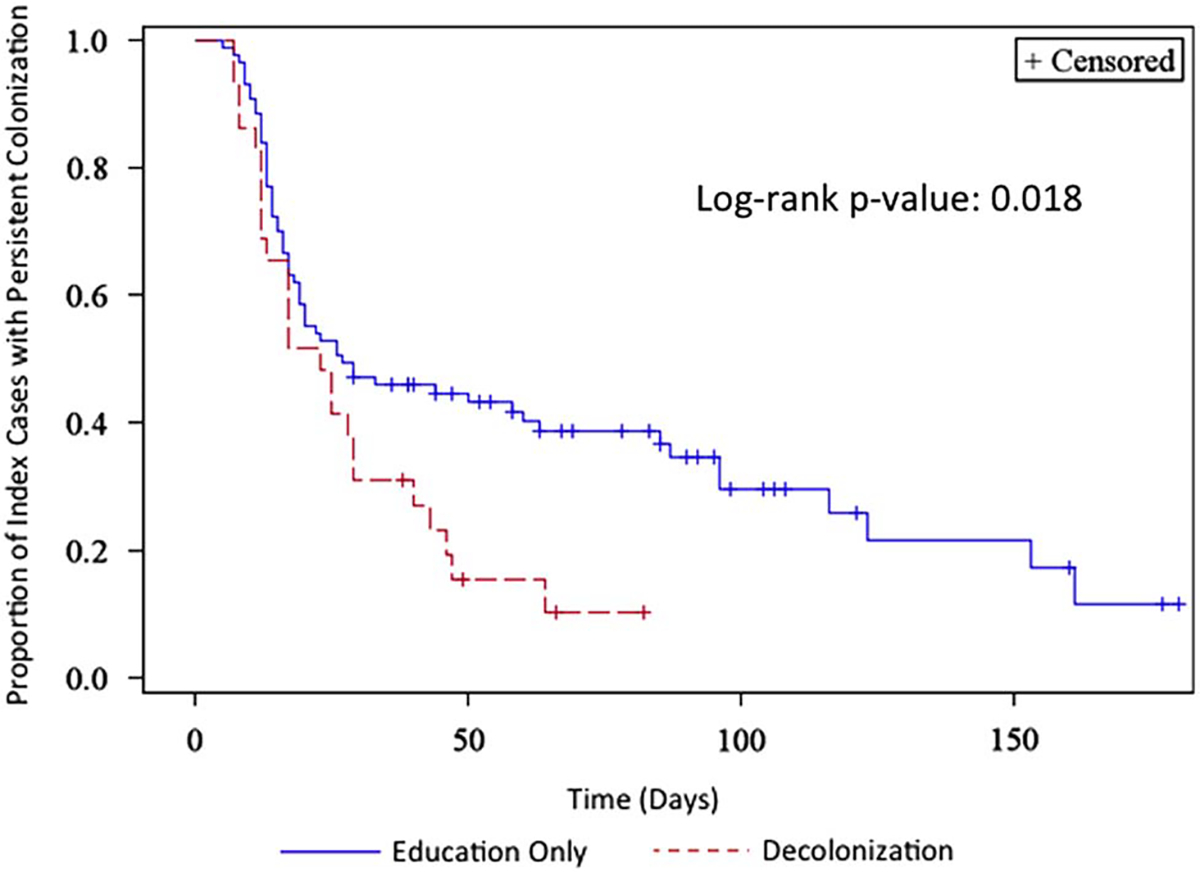

Secondary Analysis of Compliance

Subjects with missing data and with prescriptions for decolonization agents outside of the study were excluded, resulting in analysis of 116 index cases (78%). Subjects in the education-only arm were defined as having 0% compliance. Household 100% compliance with decolonization resulted in a median time to clearance of colonization of 23 days (95% CI, 12–29 days) in the index case, whereas those households with less than 100% compliance had a median time to clearance of 27 days (19–63 days; log-rank P = .018) (Figure 4). Similarly, those index cases in households with at least 50% compliance also had shorter median time to clearance of MRSA colonization compared with households with less than 50% compliance (23 days [95% CI, 17–29 days] vs 33 days [16–123 days]; log-rank P =.051) (Supplementary Figure 3). When missing compliance data were regarded as noncompliance, results were similar for both the 100% compliance and 50% thresholds (data not shown). Randomization to decolonization with reminders was not associated with either 50% or 100% compliance (P = .105 and P =.750, respectively).

FIGURE 4.

Kaplan-Meier curve of time to clearance of colonization: 100% compliance vs less than 100% compliance.

DISCUSSION

We conducted a randomized trial of total household decolonization to assess its effect on recurrent MRSA SSTI and clearance of MRSA colonization among subjects who initially presented with and were treated for acute community-onset MRSA SSTI. This cohort more accurately reflects the clinical situation ambulatory providers typically encounter. Surprisingly, very few subjects reported recurrent MRSA SSTI. We found that decolonization of all household members did not decrease time to clearance of colonization in the intention-to-treat or per-protocol analyses. However, on secondary analyses assessing degree of compliance as an exposure, subjects who were more compliant with the decolonization procedures had modest but statistically significantly shorter times to clearance of MRSA colonization.

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to compare the effect of total household decolonization with that of routine hygiene measures on clearance of MRSA colonization. Fritz and colleagues16 recently conducted a randomized controlled trial comparing individual versus total household decolonization among children who presented with S. aureus SSTI and found that total household decolonization did not lead to increased cessation of colonization but did result in fewer recurrent SSTIs. Our study demonstrated similar findings in terms of clearance of colonization when comparing total household decolonization with hygiene education only, but we could not assess the impact on recurrent SSTI because subsequent infections occurred in only 5 subjects. A randomized controlled trial of bleach baths plus education on routine hygiene measures compared with routine hygiene measures alone showed no significant difference in rate of recurrent SSTI among children,35 although that study was limited to children and employed a different decolonization protocol, and the outcome included only medically attended SSTI, which may have underestimated the true incidence of recurrent infection.

In our secondary analysis we found that better compliance was associated with more rapid clearance of MRSA colonization. Fritz et al16 noted a high rate of compliance (81%) with the decolonization protocol, which they defined as at least 5 days of 2% mupirocin applied intranasally twice daily and once-daily 4% CHG, but did not report a per-protocol analysis to determine the effect of compliance on the outcome. Although our analyses suggest that the decolonization regimen was effective when applied, it remains unclear what measure and degree of compliance is necessary to result in clinically significant outcomes and whether such compliance is feasible in real world settings.

Approximately 20% of subjects remained colonized at the end of the study period, regardless of study group. This is consistent with prior studies of MRSA colonization, showing approximately 20% of subjects will have persistent colonization.24,36,37 Further studies should seek to identify these patients earlier and examine the effect of focusing education, decolonization, and improved compliance efforts in this higher-risk population.

This study has several limitations. The low number of recurrent MRSA SSTI limited the ability to assess our primary outcome of interest (ie, recurrent MRSA SSTI). However, given that MRSA colonization often precedes infection, assessment of duration of colonization (ie, our secondary outcome) is also an important target for investigation. Masking was not possible given the nature of the interventions. Although recall bias and relying on patients to report subsequent infections are issues, information was prospectively gathered from subjects through biweekly data collection forms, initial interview, and 2 follow-up home visits to expand self-reported data. Furthermore, subjects were unaware of their treatment group until after the initial interview was completed and investigators involved in determining the outcome were masked to the subject’s intervention group to minimize misclassification bias. Although the measure of compliance was determined before data analysis, the optimal way to define compliance is unknown and requires further study. Subjects also used CHG body wash only twice rather than daily, which may have decreased effectiveness of the decolonization protocol. Additionally, we did not account for the effect of contaminated household objects or pets on the outcomes, which have been suggested to be potential reservoirs for MRSA.38–40 Finally, this study was conducted at 5 academic medical centers in Southeastern Pennsylvania, which might not be generalizable to the broader population; however, the subjects represented a large, ethnically and racially diverse population.

In conclusion, we found that total household decolonization with mupirocin and CHG body wash compared with education on routine hygiene measures alone did not result in decreased time to clearance of MRSA colonization. However, compliance with the decolonization protocol was associated with a more rapid clearance of MRSA colonization. Owing to small numbers, we were unable to examine the effect on recurrent infections. Our findings may indicate that education on hygiene measures plays a critical role in decreasing recurrent infections and, therefore, should be a focus for clinicians. Further studies should assess the beliefs and attitudes of patients and their household members regarding recurrent SSTI and decolonization recommendations in order to inform subsequent education efforts that can be combined with household decolonization. Additionally, it is important to determine the best measure and degree of compliance necessary to affect clinical outcomes, particularly recurrent infections, as well as the longer-term effects of these interventions, including their impact on clinical infections, the development of mupirocin resistance, and time to recurrence of colonization and/or infection.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial support.

Pennsylvania State Department of Health (Commonwealth Universal Research Enhancement Program grant to E.L.); National Institutes of Health (grant K24-AI080942 to E.L.); and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Epicenters Program (grant U54-CK000163 to E.L.).

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/ice.2016.138.

Trial registration. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00966446

REFERENCES

- 1.Hersh AL, Chambers HF, Maselli JH, Gonzales R. National trends in ambulatory visits and antibiotic prescribing for skin and soft-tissue infections. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:1585–1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moran GJ, Krishnadasan A, Gorwitz RJ, et al. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus infections among patients in the emergency department. N Engl J Med 2006;355:666–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaplan SL, Hulten KG, Gonzalez BE, et al. Three-year surveillance of community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus infections in children. Clin Infect Dis 2005;40:1785–1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kluytmans J, van Belkum A, Verbrugh H. Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiology, underlying mechanisms, and associated risks. Clin Microbiol Rev 1997;10:505–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mertz D, Frei R, Jaussi B, et al. Throat swabs are necessary to reliably detect carriers of Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Infect Dis 2007;45:475–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eveillard M, de Lassence A, Lancien E, Barnaud G, Ricard JD, Joly-Guillou ML. Evaluation of a strategy of screening multiple anatomical sites for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus at admission to a teaching hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2006;27:181–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peters PJ, Brooks JT, Limbago B, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization in HIV-infected outpatients is common and detection is enhanced by groin culture. Epidemiol Infect 2011;139:998–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shurland SM, Stine OC, Venezia RA, et al. Colonization sites of USA300 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in residents of extended care facilities. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2009;30:313–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang SS, Platt R. Risk of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection after previous infection or colonization. Clin Infect Dis 2003;36:281–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marschall J, Muhlemann K. Duration of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carriage, according to risk factors for acquisition. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2006;27:1206–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellis MW, Hospenthal DR, Dooley DP, Gray PJ, Murray CK. Natural history of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization and infection in soldiers. Clin Infect Dis 2004;39:971–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coello R, Glynn JR, Gaspar C, Picazo JJ, Fereres J. Risk factors for developing clinical infection with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) amongst hospital patients initially only colonized with MRSA. J Hosp Infect 1997;37:39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis KA, Stewart JJ, Crouch HK, Florez CE, Hospenthal DR. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) nares colonization at hospital admission and its effect on subsequent MRSA infection. Clin Infect Dis 2004;39:776–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller LG, Quan C, Shay A, et al. A prospective investigation of outcomes after hospital discharge for endemic, community-acquired methicillin-resistant and -susceptible Staphylococcus aureus skin infection. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44:483–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen AE, Cantey JB, Carroll KC, Ross T, Speser S, Siberry GK. Discordance between Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization and skin infections in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2009;28:244–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fritz SA, Hogan PG, Hayek G, et al. Household versus individual approaches to eradication of community-associated Staphylococcus aureus in children: a randomized trial. Clin Infect Dis 2012;54:743–751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doebbeling BN, Breneman DL, Neu HC, et al. Elimination of Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage in health care workers: analysis of six clinical trials with calcium mupirocin ointment. The Mupirocin Collaborative Study Group. Clin Infect Dis 1993;17:466–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mascitti KB, Gerber JS, Zaoutis TE, Barton TD, Lautenbach E. Preferred treatment and prevention strategies for recurrent community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin and soft-tissue infections: a survey of adult and pediatric providers. Am J Infect Control 2010;38:324–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ellis MW, Griffith ME, Dooley DP, et al. Targeted intranasal mupirocin to prevent colonization and infection by community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains in soldiers: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2007;51:3591–3598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fritz SA, Hogan PG, Hayek G, et al. Staphylococcus aureus colonization in children with community-associated Staphylococcus aureus skin infections and their household contacts. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2012;166:551–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mollema FP, Richardus JH, Behrendt M, et al. Transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus to household contacts. J Clin Microbiol 2010;48:202–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodriguez M, Hogan PG, Krauss M, Warren DK, Fritz SA. Measurement and impact of colonization pressure in households. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc 2013;2:147–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larsson AK, Gustafsson E, Nilsson AC, Odenholt I, Ringberg H, Melander E. Duration of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization after diagnosis: a four-year experience from southern Sweden. Scand J Infect Dis 2011;43:456–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cluzet VC, Gerber JS, Nachamkin I, et al. Duration of colonization and determinants of earlier clearance of colonization with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Infect Dis 2015;60:1489–1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calfee DP, Durbin LJ, Germanson TP, Toney DM, Smith EB, Farr BM. Spread of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) among household contacts of individuals with nosocomially acquired MRSA. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2003;24:422–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dietrich DW, Auld DB, Mermel LA. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in southern New England children. Pediatrics 2004;113:e347–e352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moran GJ, Amii RN, Abrahamian FM, Talan DA. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in community-acquired skin infections. Emerg Infect Dis 2005;11:928–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cluzet VC, Gerber JS, Nachamkin I, et al. Risk factors for recurrent colonization with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in community-dwelling adults and children. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2015:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zeller JL, Golub RM. JAMA patient page. MRSA infections. JAMA 2011;306:1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bishop EJ, Grabsch EA, Ballard SA, et al. Concurrent analysis of nose and groin swab specimens by the IDI-MRSA PCR assay is comparable to analysis by individual-specimen PCR and routine culture assays for detection of colonization by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol 2006;44:2904–2908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grmek-Kosnik I, Ihan A, Dermota U, Rems M, Kosnik M, Jorn Kolmos H. Evaluation of separate vs pooled swab cultures, different media, broth enrichment and anatomical sites of screening for the detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from clinical specimens. J Hosp Infect 2005;61:155–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lautenbach E, Nachamkin I, Hu B, et al. Surveillance cultures for detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: diagnostic yield of anatomic sites and comparison of provider- and patient-collected samples. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2009;30:380–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Han Z, Lautenbach E, Fishman NO, Nachamkin I. Evaluation of mannitol salt agar, CHROMagar™ Staph aureus and CHROMagar™ MRSA for detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from nasal swab specimens. J Med Microbiol 2007;56:43–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: 18th Informational Supplement. CLSI document. Wayne, PA: CLSI; 2008:M100–S18. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaplan SL, Forbes A, Hammerman WA, et al. Randomized trial of “bleach baths” plus routine hygienic measures vs. routine hygienic measures alone for prevention of recurrent infections. Clin Infect Dis 2014;58:679–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scanvic A, Denic L, Gaillon S, Giry P, Andremont A, Lucet JC. Duration of colonization by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus after hospital discharge and risk factors for prolonged carriage. Clin Infect Dis 2001;32:1393–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robicsek A, Beaumont JL, Peterson LR. Duration of colonization with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Infect Dis 2009;48:910–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fritz SA, Hogan PG, Singh LN, et al. Contamination of environmental surfaces with Staphylococcus aureus in households with children infected with methicillin-resistant S aureus. JAMA Pediatr 2014;168:1030–1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bramble M, Morris D, Tolomeo P, Lautenbach E. Potential role of pet animals in household transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a narrative review. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2011;11:617–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davis MF, Iverson SA, Baron P, et al. Household transmission of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and other staphylococci. Lancet Infect Dis 2012;12:703–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.