Abstract

Background

Few observations exist with respect to the pro‐coagulant profile of patients with COVID‐19 acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Reports of thromboembolic complications are scarce but suggestive for a clinical relevance of the problem.

Objectives

Prospective observational study aimed to characterize the coagulation profile of COVID‐19 ARDS patients with standard and viscoelastic coagulation tests and to evaluate their changes after establishment of an aggressive thromboprophylaxis.

Methods

Sixteen patients with COVID‐19 ARDS received a complete coagulation profile at the admission in the intensive care unit. Ten patients were followed in the subsequent 7 days, after increasing the dose of low molecular weight heparin, antithrombin levels correction, and clopidogrel in selected cases.

Results

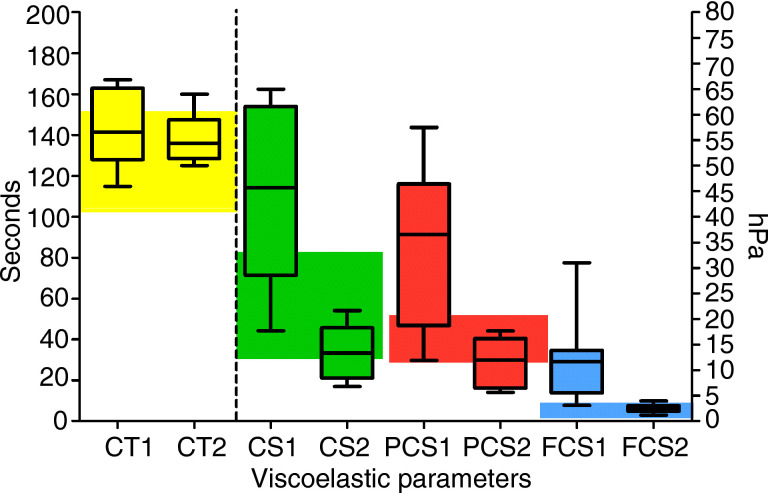

At baseline, the patients showed a pro‐coagulant profile characterized by an increased clot strength (CS, median 55 hPa, 95% interquartile range 35‐63), platelet contribution to CS (PCS, 43 hPa; interquartile range 24‐45), fibrinogen contribution to CS (FCS, 12 hPa; interquartile range 6‐13.5) elevated D‐dimer levels (5.5 μg/mL, interquartile range 2.5‐6.5), and hyperfibrinogenemia (794 mg/dL, interquartile range 583‐933). Fibrinogen levels were associated (R2 = .506, P = .003) with interleukin‐6 values. After increasing the thromboprophylaxis, there was a significant (P = .001) time‐related decrease of fibrinogen levels, D‐dimers (P = .017), CS (P = .013), PCS (P = .035), and FCS (P = .038).

Conclusion

The pro‐coagulant pattern of these patients may justify the clinical reports of thromboembolic complications (pulmonary embolism) during the course of the disease. Further studies are needed to assess the best prophylaxis and treatment of this condition.

Keywords: coagulation parameter, D‐dimer, viscoelastic tests, COVID‐19, acute respiratory distress syndrome

Essentials

-

•

COVID‐19 patients with ARDS show a procoagulant pattern at both standard and viscoelastic tests.

-

•

Fibrinogen levels and platelet count are increased.

-

•

At viscoelastic tests, there is an increased clot strength due to both fibrinogen and platelet contribution.

-

•

After 14 days of aggressive anti‐thrombotic therapy, viscoelastic tests return to values close to normal.

Alt-text: Unlabelled Box

1. INTRODUCTION

Patients with COVID‐19 associated pneumonia exhibit a number of abnormal coagulation parameters, according to different reports,1., 2., 3. and coagulation abnormalities have been associated with a higher mortality rate.3., 4., 5. The hemostatic system alterations include changes in the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), in the International Normalized Ratio (INR) of the prothrombin time, increased D‐dimer and fibrin degradation products. The aPTT and the prothrombin time were found shorter than normal in 16% and 30% of the patients, respectively.2 Patterns of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) were reported in deaths, and within this group the aPTT and the prothrombin time were prolonged.3

In our intensive care unit (ICU) we started admitting patients with COVID‐19 infection and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) since March 8. In the first 2 days, we had two mortality cases with a pattern of pulmonary embolism (sudden death after mobilization with signs of acute right ventricular failure), and other hospitals in our network reported similar cases. Pulmonary embolism cases in COVID‐19 patients have already been reported in the literature,6 and in a recent report from EuroELSO, 20% of patients under extracorporeal membrane oxygenation had pulmonary embolism.7 From 2 to 5 days after the first admission in the ICU, we started a wide collection of laboratory data and coagulation point‐of‐care tests viscoelastic tests to characterize the coagulation profile of these patients. Additionally, after the first round of tests, we have changed our standard anticoagulant therapy toward a higher degree of anticoagulation. In this study, the coagulation profile of COVID‐19 ARDS patients is analyzed with standard tests and visco‐elastic tests, and the differences induced by a more aggressive antithrombotic therapy are investigated.

2. METHODS

2.1. Patient population

The patient population comprised 16 patients with a diagnosis of COVID‐19‐associated pneumonia and ARDS, admitted to our ICU under tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the San Raffaele Hospital. Data are presented in an anonymous form.

2.2. Central laboratory and point‐of‐care coagulation tests

The hemostasis and coagulation characterization included the measure of the aPTT, INR, platelet count, fibrinogen, D‐dimer, and antithrombin (AT) activity. INR and aPTT were assessed using the STA‐NeoPTimal 10 and the STA‐Cephascreen 10 (Diagnostica Stago), respectively; fibrinogen was measured using the Clauss‐based STA‐LiquidFib (Diagnostica Stago). Cytokine levels (interleukin‐6 [IL‐6]) were measured at the admission in the ICU.

Viscoelastic tests were performed after 2 to 5 days from the admission in the ICU. We have used a Quantra Hemostasis analyzer (Quantra System; HemoSonics LLC) that uses an ultrasound‐based technology that measures changes in viscoelastic properties of whole blood. The Quantra System includes a consumable cartridge that provides a number of parameters related to clot time and clot stiffness. Blood is collected in citrated tubes and blood is directly suctioned by the instrument, without blood dispersion. This study was performed using the Quantra QPlus cartridge, which includes four parallel channels, each prefilled with specific lyophilized reagents and performing simultaneous measurements. The output of the instrument consists of (a) clot coagulation time (CT, seconds) after blood activation with kaolin; (b) clot stiffness (CS, hPa) after activation by thromboplastin; (c) fibrinogen contribution to the overall clot stiffness (FCS, hPa) by adding abciximab (ReoPro; Eli Lilly); and (d) platelet contribution to CS (PCS, hPa), as difference between the total CS and the FCS.8

All patients received a baseline determination of standard and viscoelastic tests. Ten patients were followed over the next 7 days, with daily measure of standard tests.

2.3. Thromboembolic prophylaxis and other therapies

At the ICU admission, all patients were receiving a thromboprophylaxis management of 4000 IU twice daily low molecular weight heparin (LMWH, calcium nadroparin). After the first round of standard coagulation and viscoelastic tests, the patients were switched to the following protocol: LMWH 6000 twice daily (8000 IU twice daily if body mass index >35); AT concentrate to correct values <70%; clopidogrel loading dose 300 mg + 75 mg/d if platelet count >400 000 cells/µL. Additional therapies included hydroxychloroquine and antiviral agents.

All patients were sedated with propofol or midazolam and mechanically ventilated under full muscle relaxant dose.

2.4. Statistics

Data are presented as number (%) or median (interquartile range) as appropriate. Data were tested for differences at the various points in time using a Friedman test. Correlation between different continuous variables was tested with linear or polynomial regression analyses. For all the tests, a two‐tailed P value <.05 was considered significant. The statistical analyses were conducted using computerized packages (SPPS 13.0, IBM and GraphPad).

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Table 1 reports the baseline characteristics of our patient population at baseline and follow‐up. Overall, 94% of the patients were males. Five (31%) were obese, according to the definition of the World Health Organization, and four of five had a body mass index >35. Median values of coagulation parameters showed a prolongation of the aPTT, with platelet count within the normal range and one patient with thrombocytosis (472 000 cells/μL). Four patients (25%) had AT levels below the lower limit of the normal range; the median value of fibrinogen was higher than the upper limit of the normal range, and all the patients had values higher than 400 mg/dL. D‐dimer and IL‐6 values were higher than the upper limit of the normal range in all the patients.

TABLE 1.

Demographics and coagulation parameters of the patient population at baseline and follow‐up

| Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | 61 (55‐65) |

| Gender (male/female) | 15/ 1 |

| Intubation time (d) at baseline | 7 (3.5‐10) |

| Weight (kg) | 85 (72‐109) |

| Body mass index | 26.4 (23.9‐35.1) |

| Obese (body mass index >30) | 5 |

| Standard tests | Normal range | Baseline | Follow‐up 7 d | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| aPTT (sec) | 24‐35 | 36.4 (29‐41.6) | 44.1 (42.1‐47.4) | .012 |

| INR | 1.08 (0.98‐1.11) | 1.13 (1.08‐1.19) | .500 | |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 200‐400 | 794 (583‐933) | 582 (446‐621) | .001 |

| Platelet count (×1000 cells/µL) | 150‐450 | 271 (192‐302) | 320 (308‐393) | .463 |

| Antithrombin (%) | 80‐120 | 85 (65‐91) | 107 (81‐130) | .018 |

| D‐dimer (µg/mL) | <0.5 | 3.5 (2.5‐6.5) | 2.5 (1.6‐2.8) | .017 |

| Interleukin‐6 (pg/mL) | 0 ‐ 10 | 218 (116‐300) | – | – |

| Viscoelastic tests | Normal range | Baseline | Follow‐up 14 d | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clotting time (s) | 103‐153 | 139 (133‐155) | 135 (125‐151) | .058 |

| Clot strength (hPa) | 13‐33.2 | 55 (35‐63) | 34 (17‐54) | .013 |

| Platelet contribution to clot strength (hPa) | 11.9‐29.8 | 43 (24‐45) | 29 (14‐44) | .035 |

| Fibrinogen contribution to clot strength (hPa) | 1‐3.7 | 12 (6‐13.5) | 6.2 (3‐9.9) | .038 |

Note:Data are median and interquartile range.

Abbreviations: aPTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; INR, international normalized ratio of the prothrombin time.

Fibrinogen levels were significantly (P = .003) associated with the IL‐6 values at baseline, according to a logarithmic regression (R 2 for association = .506) (Figure 1 ).

FIGURE 1.

Association between interleukin‐6 values and fibrinogen levels. Logarithmic regression; gray area is 95% confidence interval

Viscoelastic tests showed normal values of CT but confirmed a clot firmness higher than normal, with median values of CT, PCS, and FCS higher than the upper limit of normal range. Eleven (69%) patients had CT values longer than the upper limit of the normal range, with 10 patients (62%) showing PCS values above the upper limit of normal range and 15 (94%) patients with FCS values above the upper limit of the normal range.

Nine patients received a second viscoelastic test after 2 weeks from the baseline (Figure 2 ). There was a significant decrease of CS (P = .013), PCS (P = .035), and FCS (P = .038).

FIGURE 2.

Baseline viscoelastic parameters. Boxes represent median and interquartile range, whiskers minimum to maximum values. CT, clotting time (left Y axis); CS, clot strength; FCS, fibrinogen contribution to clot strength; PCS, platelet contribution to clot strength (right Y axis). Colored areas are normal range. The numbers after the variables on the X‐axis express baseline (1) and follow‐up at 2 weeks (2)

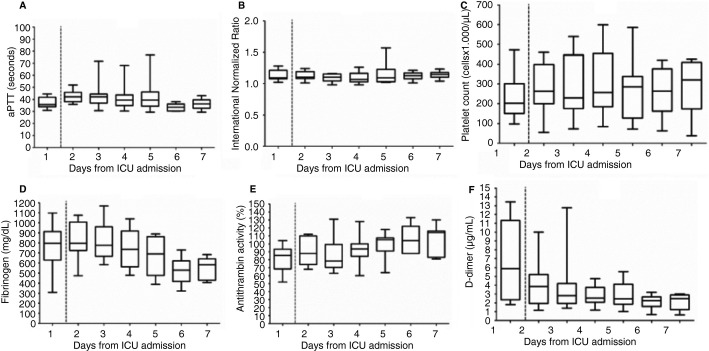

Time‐related changes in standard coagulation profile are shown in Figure 3 . Changes in INR and platelet count were nonsignificant. There was a significant (P = .012) prolongation of the aPTT and a significant (P = .001) decrease of fibrinogen levels and D‐dimers. AT levels significantly (P = .018) increased, with two patients receiving AT concentrate supplementation on day 2.

FIGURE 3.

Time course of coagulation parameters. Boxes represent median and interquartile range, whiskers minimum to maximum values. aPTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; ICU, intensive care unit. Dashed line represents onset of enhanced anti‐thrombotic prophylaxis

The main finding of our study is the pro‐coagulant profile of COVID‐19 ARDS patients and its progression toward normalization after an increased thromboprophylaxis.

The baseline pattern of our patient population is an increased clot strength, which in 100% of the patient population was related to high fibrinogen levels, and in about 60% even to an elevated platelet contribution to clot strength.

From an interpretative perspective, this pattern sticks to a model of interaction between inflammation and coagulation. All the patients had elevated values of IL‐6, and a clear association between IL‐6 and fibrinogen levels was demonstrated. IL‐6 is a powerful pro‐inflammatory cytokine, which induces tissue factor gene expression in endothelial cells and monocytes, fibrinogen synthesis, and platelet production, without affecting fibrinolysis.9., 10. Tissue factor triggers thrombin generation, and the combination of these factors produce a pro‐coagulant profile that was evident in our patient population. Unfortunately, we are lacking direct data on thrombin generation, and the different parameters related to clot formation time (aPTT, INR, and CT) basically reflect the ongoing thrombosis prophylaxis/therapy by LMWH. However, the evidence of an AT consumption at baseline is an indirect marker of thrombin generation. D‐dimers are certainly nonspecific parameters of thrombi formation, but within this pattern they suggest thrombi generation and fibrinolysis.

The establishment of a more pronounced thromboprophylaxis (increased doses of LMWH, AT correction, and clopidogrel in case of thrombocytosis) resulted in a significant decrease of fibrinogen levels and D‐dimers, and of the viscoelastic parameters related to clot strength.

D‐dimer levels have been identified as markers of severity of the disease4 and predictive of mortality.3 The decrease of D‐dimers is therefore suggestive of a decrease severity of the disease. Previous studies have stressed a possible transition to a DIC associated with mortality, and in this case, following its natural course, the prothrombotic state is converted into a pro‐hemorrhagic pattern.3 In our series, we could not observe a transition toward this state, conversely noticing, after 2 weeks, a return to normal of viscoelastic parameters in the survived patients.

This pattern of prothrombotic coagulopathy is different from what noticed in sepsis, where thrombocyte count is usually decreased, and of DIC, where the exhausted coagulation system shows a prolongation of the prothrombin time and aPTT, and a hemorrhagic tendency. It is possible that the aggressive thromboprophylaxis may have slowed or blocked the transition to DIC, as suggested by the tendency to normalize the coagulation parameters after 7 to 14 days.

From a clinical perspective, it is now evident that COVID‐19 ARDS patients may suffer from thromboembolic complications. Cases of pulmonary embolism have been published,6 and a recent report of the French experience with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in COVID‐19‐induced ARDS showed 20% of pulmonary embolism events and two oxygenator thrombosis. The link between influenza‐associated pneumonia and thromboembolic events was already stressed in previous studies.11 Our study, in combination with the other contributions in literature, suggests the potential role of micro‐/macro‐aggregate formation inside the pulmonary vasculature within the pattern of ARDS in COVID‐19 patients. This could justify the evidence of a severe impairment of oxygenation, despite a preserved lung compliance (at least in the early stages of the disease).

In our series of 16 patients, after increasing the anticoagulation regimen we did not observe major thromboembolic events. Six (37.5%) patients were extubated and discharged to the ward; three (18.7%) are still in the ICU; seven (43.7%) did not recover and died from hypoxia and multiorgan failure. An aggressive thromboprophylaxis of these patients seems justified, and the recent guidance of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis stresses the need for coagulation monitoring and LMWH therapy.12 A recent study demonstrated a lower 28‐day mortality rate in patients receiving anticoagulation with LMWH.13 Other strategies could include the use of intravenous unfractionated heparin or direct thrombin inhibitors (bivalirudin or argatroban).

The main limitations of our study are the small sample size and the lack of direct data on thrombin generation and fibrinolysis. Being a nonrandomized trial, our hypothesis that the patients may benefit from a pronounced anticoagulation needs to be confirmed by adequate randomized controlled trials.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dr. Ranucci and and Dr. Bayshnikova received speaker's fees and research funds from HemoSonics. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Marco Ranucci designed the study. Andrea Ballotta, Marco Resta, Marco Dei Poli, and Umberto Di Dedda collected the data. Ekaterina Bayshnikova analyzed the viscoelastic tests. Mara Falco provided the literature search on thromboembolic events imaging and critically revised the manuscript. Giovanni Albano designed the study with Marco Ranucci. Lorenzo Menicanti critically revised the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

IRCCS Policlinico San Donato

Clinical Research Hospital

Italian Ministry of Health

Footnotes

Manuscript handled by: Jean Connors

Final decision: Jean Connors, 14 April 2020

Funding informationThis study was funded by the IRCCS Policlinico San Donato, a Clinical Research Hospital recognized and partially funded by the Italian Ministry of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang N., Li D., Wang X., Sun Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(4):844–847. doi: 10.1111/jth.14768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y., et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID‐19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xie Y., Wang X., Yang P., Zhang S. COVID‐19 complicated by acute pulmonary embolism. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging. 2020;2(2) doi: 10.1148/ryct.2020200067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.ECMO and COVID‐19. Experience from Paris. EuroELSO Webinar, https://www.euroelso.net/webinars/. Accessed April 3, 2020.

- 8.Ferrante E.A., Blasier K.R., Givens T.B., et al. A novel device for evaluation of hemostatic function in critical care settings. Anesth Analg. 2016;123:1372–1379. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerr R., Stirling D., Ludlam C.A. Interleukin 6 and haemostasis. Br J Haematol. 2001;115:3–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.03061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bode M., Mackman N. Regulation of tissue factor gene expression in monocytes and endothelial cells: thromboxane A2 as a new player. Vascul Pharmacol. 2014;62:57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishiguro T., Matsuo K., Fujii S., Takayanagi N. Acute thrombotic vascular events complicating influenza‐associated pneumonia. Respir Med Case Rep. 2019;28:100884. doi: 10.1016/j.rmcr.2019.100884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thachil J., Wada H., Gando S., et al. ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID‐19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1023–1026. doi: 10.1111/jth.14810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang N., Bai H., Chen X., Gong J., Li D., Sun Z. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1094–1099. doi: 10.1111/jth.14817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]