Abstract

Background

Cluster of differentiation (CD)73-adenosine and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β pathways are involved in abrogated antitumor immune responses and can lead to protumor conditions. This Phase 1 study (NCT03954704) evaluated the safety, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and efficacy of dalutrafusp alfa (also known as GS-1423 and AGEN1423), a bifunctional, humanized, aglycosylated immunoglobulin G1 kappa antibody that selectively inhibits CD73-adenosine production and neutralizes active TGF-β signaling in patients with advanced solid tumors.

Methods

Dose escalation started with an accelerated titration followed by a 3+3 design. Patients received dalutrafusp alfa (0.3, 1, 3, 10, 20, 30, or 45 mg/kg) intravenously every 2 weeks (Q2W) up to 1 year or until progressive disease (PD) or unacceptable toxicity.

Results

In total, 21/22 patients received at least one dose of dalutrafusp alfa. The median number of dalutrafusp alfa doses administered was 3 (range 1–14). All patients had at least one adverse event (AE), most commonly fatigue (47.6%), nausea (33.3%), diarrhea (28.6%), and vomiting (28.6%). Nine (42.9%) patients had a Grade 3 or 4 AE; two had Grade 5 AEs of pulmonary embolism and PD, both unrelated to dalutrafusp alfa. Target-mediated drug disposition appears to be saturated at dalutrafusp alfa doses above 20 mg/kg. Complete CD73 target occupancy on B cells and CD8+ T cells was observed, and TGF-β 1/2/3 levels were undetectable at dalutrafusp alfa doses of 20 mg/kg and higher. Free soluble (s)CD73 levels and sCD73 activity increased with dalutrafusp alfa treatment. Seventeen patients reached the first response assessment, with complete response, partial response, stable disease, and PD in 0, 1 (4.8%), 7 (33.3%), and 9 (42.9%) patients, respectively.

Conclusions

Dalutrafusp alfa doses up to 45 mg/kg Q2W were well tolerated in patients with advanced solid tumors. Additional evaluation of dalutrafusp alfa could further elucidate the clinical utility of targeting CD73-adenosine and TGF-β pathways in oncology.

Keywords: adenosine, immunomodulation, immunotherapy, tumor biomarkers, tumor microenvironment

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Cluster of differentiation (CD)73-adenosine and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β signaling pathways may be involved in abrogated antitumor immune responses, leading to protumorigenic conditions, and could be considered targets of therapeutic intervention.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This study describes a first-in-human study of dalutrafusp alfa (also known as GS-1423 and AGEN1423), a first-in-class, bifunctional, humanized antibody designed to selectively inhibit CD73-adenosine production and neutralize active TGF-β signaling within the tumor microenvironment. Although full target occupancy was reached at >20 mg/kg, soluble CD73 levels and activity increased above baseline. Dalutrafusp alfa was well tolerated in patients up to 45 mg/kg dosed every 2 weeks, with mostly mild and moderate adverse events reported.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

These clinical and pharmacodynamic results may inform the design of future inhibitors and studies that attempt to target the CD73-adenosine and TGF-β signaling pathways as therapeutic interventions in oncology.

Introduction

Adenosine and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β increase in the tumor microenvironment and are two immunosuppressive mechanisms suspected to contribute to therapeutic resistance and progressive disease (PD).1 Cluster of differentiation (CD)73 is an ectoenzyme found on cell surfaces and in circulation that converts adenosine monophosphate (AMP) to adenosine.2 3 Adenosine generated in the tumor microenvironment and its agonism of adenosine receptor A2A found on T-cells may lead to suppression of T-cell receptor signaling, thus inducing an immunosuppressive effect. Animals lacking CD73 have decreased carcinogenesis, and studies have shown that tumor growth, metastasis, and immunosuppression can be inhibited by CD73 blockade.4–7 Upregulation of CD73/adenosine is observed in human melanomas,5 8 with high CD73 expression being an unfavorable prognostic factor in patients with cancer.9

TGF-β is a pleiotropic cytokine that regulates cell growth in several organ systems and may be involved in tumor growth and metastasis.10 Early in cancer development, TGF-β suppresses tumor growth but promotes tumor progression in later stages.11 TGF-β can also regulate the adaptive immune system by suppressing interferon-γ expression, attenuating CD8+ effector T-cell function, and inducing differentiation of regulatory T cells.12 TGF-β overexpression during late stages of cancer is associated with therapeutic resistance,13 and treatments that inhibit the TGF-β receptor are being developed to treat patients with cancer.14 TGF-β cytokine traps demonstrate positive results in treating cancerous tumors by neutralizing active TGF-β signaling within the tumor microenvironment while maintaining acceptable safety in rodents and humans.15–17 The roles of CD73-adenosine and TGF-β pathways in tumorigenesis and resistance to treatment suggest they are promising drug targets in oncology. However, targeting only one of these pathways may not be sufficient to enable effective therapeutic responses due to the prevalence of both pathways in human cancers and the development of and treatment with a single molecule may be preferred over two novel agents. Therefore, there may be clinical utility in simultaneously targeting the CD73-adenosine and TGF-β pathways in patients with cancer.

Dalutrafusp alfa (also known as GS-1423 and AGEN1423) is a first-in-class, bifunctional, humanized, aglycosylated immunoglobulin G1 kappa antibody comprizing an anti-CD73 antibody fused to a TGF-βreceptor II-based cytokine trap (online supplemental figure S1). Dalutrafusp alfa binds to human CD73 with an estimated binding affinity (KD; elimination rate constant apparent) of 32 pM under avid binding conditions and 26 nM under monovalent fragment antigen-binding conditions (online supplemental figure S2). The TGF-β trap uses the extracellular domain of the natural TGF-βRII; therefore, dalutrafusp alfa is expected to bind TGF-β1, TGF-β2, and TGF-β3 effectively.18 This first-in-human study was designed to assess the safety and tolerability of dalutrafusp alfa monotherapy in patients with solid tumors and to define dose-limiting toxicities (DLT) and the maximum tolerated dose (MTD). Secondary objectives included characterizing the pharmacokinetics and evaluating immunogenicity of dalutrafusp alfa. Exploratory objectives included characterizing the pharmacodynamics and assessing the clinical efficacy of dalutrafusp alfa.

jitc-2022-005267supp001.pdf (2.8MB, pdf)

Materials and methods

Patient population

This was a Phase 1, open-label, dose-escalation study of dalutrafusp alfa in patients with advanced solid tumors (NCT03954704). Patients were enrolled at four sites (all in the USA) between June 2019 and April 2021. Patients were eligible if they were aged 18 years or more with confirmed advanced or metastatic solid tumor(s) for which standard therapy had failed or no standard therapy was available. Additional inclusion criteria are listed in the online supplemental file 1. Key exclusion criteria included other concurrent malignancies, known central nervous system metastases, or active or history of autoimmune disease. Full exclusion criteria are found in the Supplemental Material.

This study and all investigators abided by Good Clinical Practices in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Council for Harmonization. All patients in the study provided written informed consent.

Study design

Dalutrafusp alfa (0.3, 1, 3, 10, 20, 30, or 45 mg/kg) was administered intravenously to patients on Day 1 of each 2-week cycle (Q2W) for up to 1 year (maximum 26 cycles) or until PD or unacceptable toxicity occurred. Dalutrafusp alfa dose interruption (but not dose reduction) was permitted for adverse events (AEs). A modified, accelerated, dose-titration design was used for the first two dose levels, 0.3 and 1 mg/kg, followed by a 3+3 dose-escalation design for dose levels 3 mg/kg and above to determine the DLT and MTD of dalutrafusp alfa.19 DLTs were evaluated in patients during the first 28 days of dalutrafusp alfa administration. The complete DLT criteria are described in the Supplemental Material. The MTD is defined as the highest dose level with an incidence of DLTs in one or fewer of six patients during the first 28 days of study drug dosing. Additional details for MTD determination are described in the Supplemental Material.

In addition to dose escalation, this study was planned to assess dalutrafusp alfa flat-dose regimens, dalutrafusp alfa in combination with a chemotherapy regimen in gastric cancer, and dalutrafusp alfa in patients with advanced solid tumors accessible for biopsy. After monotherapy dose escalation, the decision was made not to continue clinical evaluation of dalutrafusp alfa in this study.

Safety

Following the first dose of dalutrafusp alfa, patients were monitored for safety (AEs and laboratory data) for the duration of the study. Assessment of clinical laboratory test findings, physical examination, 12-lead electrocardiogram, echocardiogram or mitigated acquisition scans, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, and vital signs were conducted for the duration of the study. A safety review team was established to determine safety, make decisions on dose escalation, and assess DLTs and determine MTD. Clinical AEs were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities V.23.1, and both AEs and laboratory abnormalities were graded by Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events V.5.0.

Pharmacokinetics and immunogenicity

Dalutrafusp alfa concentrations in platelet-poor plasma were determined using a validated bioanalytical immunoassay method (BioAgilytix, Durham, North Carolina, USA). The assay uses an anti-idiotype mouse monoclonal antibody coated on the wells of a 96-well microtiter plate to capture dalutrafusp alfa that has an available CD73 binding site. A SULFO-tagged (ruthenylated) mouse monoclonal antibody binds the human TGF-β receptor II portion of dalutrafusp alfa as the detection agent and emits a luminescence signal on electrochemical stimulation. The method detects free dalutrafusp alfa, defined as a dalutrafusp alfa species that has at least one available CD73 binding site and one available TGF-β binding site. The lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ) is 30 ng/mL of dalutrafusp alfa per mL of plasma. Neither TGF-β nor CD73 interfered with the method at their physiologically relevant plasma concentrations.

Pharmacokinetic blood samples were collected at Cycle 1 predose, end of infusion (+10 min), and at 2 hours (±15 min), 6 hours (±0.5 hours), Day 2 (24±2 hours), Day 3 (48±4 hours), Day 5 (96±4 hours), and Day 8 (168±4 hours) after start of infusion and at Cycle 2 predose (336 hours [±1 day] post start of infusion at Cycle 1). Pharmacokinetic parameters were estimated using Phoenix WinNonlin software V.8.2 (Certara USA, Princeton, New Jersey, USA) and standard non-compartmental methods. Estimated parameters included maximum observed dalutrafusp alfa concentration (Cmax), concentration at the end of the dosing interval (Ctrough), area under the concentration versus time curve over the dosing interval (AUCtau), and time to Cmax (Tmax).

Immunogenicity was assessed in plasma by a validated, bridging affinity capture elution immunoassay method (BioAgilytix, Durham, North Carolina, USA) that uses dalutrafusp alfa coated on the wells of a microtiter plate to capture antidrug (ie, anti-dalutrafusp alfa) antibodies (ADAs) and ruthenylated dalutrafusp alfa to detect captured ADAs by electrochemiluminescent signal emission on electrochemical stimulation. The method had a lower limit of detection of 4.26 ng/mL of a positive control ADA (1:1 mixture [mole:mole] of a mouse monoclonal anti-TGF-β receptor II antibody and a mouse monoclonal anti-dalutrafusp alfa idiotype antibody) and could detect 500 ng/mL or 11.0 ng/mL of the positive control at up to 500 µg/mL or 12.5 µg/mL of dalutrafusp alfa, respectively, in the test sample. Neither TGF-β nor CD73 interfered with the method at their physiologically relevant plasma concentrations. ADA assessments were conducted predose for Cycles 1–4, 6, and every 6 cycles after. ADA was also assessed on Day 15 of Cycle 4 postdose. Immunogenicity to dalutrafusp alfa among patients was evaluated based on number and percentage of positive or negative results at each specified time point.

Pharmacodynamic biomarker testing

Pharmacodynamic biomarker assessments were performed in serial blood samples from 21 patients treated with dalutrafusp alfa. Blood for biomarker testing was collected predose at Cycles 1–4, 7, 13, and at end of treatment. For Cycles 1 and 4, blood was also collected at 2, 6, 24, and 168 hours after the start of infusion. Dalutrafusp alfa–unbound TGF-β 1/2/3, CD73 target occupancy (TO) and expression on B cells and CD8+ T cells, free soluble (s)CD73 levels, and sCD73 activity were all quantified.

Total TGF-β 1/2/3 levels were determined with an analytically qualified Magnetic Bio-Plex Pro TGF-β 1/2/3 assay (Cat# 171W4001M; Bio-Rad). The assay was qualified for sodium heparin (NaHep) platelet-poor plasma. Blood was collected into NaHep tubes and processed to platelet-poor plasma through double centrifugation and stored frozen at −80°C until analysis. TGF-β 1/2/3 were detected with a Luminex FLEXMAP 3D Analyzer. Assay qualification and clinical sample testing were performed at Gilead Sciences.

CD73 expression and TO on B cells and CD8+ T cells were measured in whole blood collected in Cyto-Chex blood collection tubes using flow cytometry staining panels consisting of CD45 (BD Biosciences, 624328), CD3 (BioLegend, 300415), CD8 (BioLegend, 301033), CD19 (BioLegend, 302208), and either a dalutrafusp alfa–competitive CD73 (clone AD2, BioLegend, 344006) or a dalutrafusp alfa–non-competitive CD73 (clone 416, Agenus) antibody. Assays were developed at Gilead Sciences, and then transferred to and qualified at CellCarta (Fremont, California, USA). Whole blood was collected at the clinical sites and shipped overnight to CellCarta and processed using BD Phosflow Lyse/Fix (BD Biosciences, 558049) and BD bovine serum albumin stain buffer (BD Biosciences, 554657) in accordance with vendor instructions. The integrated median fluorescent intensity of CD73, which is the product of the positive gate percent frequency of the parent population multiplied by its MFI, was determined for predose and postdose samples. Surface CD73 expression (%CD73 loss) and %TO were calculated using the equations listed in the Supplemental Material.

Free (unbound dalutrafusp alfa) sCD73 in platelet-poor NaHep plasma was measured by a quantitative ELISA. A monoclonal CD73 antibody (Millipore Cat# MABD122) was precoated onto a microplate, then standards and samples were added. sCD73 in samples was bound by the immobilized antibody and detected using a biotinylated monoclonal CD73 antibody (Clone 562, Agenus), streptavidin horseradish peroxidase (HRP; Thermo Scientific Cat# N201), and fluorogenic HRP substrate (Thermo Scientific Cat# 15169). Fluorescence intensity was determined using a microplate reader (Molecular Devices, SpectraMax M5). sCD73 in samples was quantified by interpolation from the standard curve. Assay development, qualification, and clinical sample testing were performed at Gilead Sciences.

sCD73 enzymatic activity in platelet-poor NaHep plasma was measured by quantifying free phosphate, a product from the hydrolysis of AMP by sCD73. To block tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase (TNAP) activity, a TNAP inhibitor (TNAPi; EMD Millipore, Cat# 613810) was added to samples prior to initiating the sCD73 enzyme reaction. Reactions were initiated by combining TNAPi-treated plasma with AMP (Sigma-Aldrich Cat# 01930) so that concentrations of 95% plasma, 4 mM AMP, and 0.5 mM TNAPi were achieved. Reactions were incubated at 37°C and terminated using 5% v/v trichloroacetic acid (Sigma-Aldrich: Cat# T0699) after 0, 20, 40, and 180 min. Phosphate concentrations in completed reaction mixtures were quantified using the Malachite Green Phosphate Assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich: Cat# MAK307), and the absorbance was measured at 620 nm using a microplate reader (Molecular Devices SpectraMax M5e). Phosphate concentration was interpolated from a standard curve. To determine the sCD73 enzyme rate, phosphate concentrations at Time 0 were subtracted from the phosphate concentrations in the 20, 40, or 180 min reactions for each sample. Change in phosphate concentration was then plotted as a function of time, and the slope of the fitted line was reported as the sCD73 enzyme activity rate (μM phosphate/minute). Assay development, qualification, and clinical sample testing were performed at Gilead Sciences.

Clinical efficacy

Radiologic tumor assessments were performed at 6, 12, 18, and 24 weeks from first treatment dose, then every 12 weeks thereafter. Response assessments were performed by the investigator according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors V.1.1.20 Patients who discontinued study treatment for reasons other than PD were followed until study discontinuation criteria were met. All patients who discontinued study treatment were followed for survival up to 12 months.

Statistical analysis

Unless otherwise indicated, 90% CIs or binary variables were calculated using the exact method and were two sided. Baseline demographics were summarized using descriptive methods. Safety was summarized using descriptive statistics by dose level/cohort for the safety analysis set, which included all patients who received at least one dose of study drug. In this study, AEs were considered treatment emergent if the onset date of the AE was on or after the first dosing date of dalutrafusp alfa and no later than 30 days after permanent discontinuation of dalutrafusp alfa. Pharmacokinetic parameters were summarized descriptively in patients in the pharmacokinetic analysis set, which includes all enrolled patients who received at least one dose of study drug and had at least one non-missing postdose concentration value. Immunogenicity was assessed in the immunogenicity analysis set, which includes all enrolled patients who received at least one dose of study drug and had at least one ADA test. Absolute and derived (CD73 and TO on B cells and CD8+ T cells) pharmacodynamic biomarker values were plotted longitudinally by dose, and no statistical analyses were conducted. Data were analyzed from the biomarker analysis set, which includes all enrolled patients who received at least one dose of study drug and had at least one evaluable biomarker measurement available. Clinical efficacy analyses were conducted using the full analysis set (all enrolled patients who received at least one dose of study drug).

Results

Patients and baseline demographics

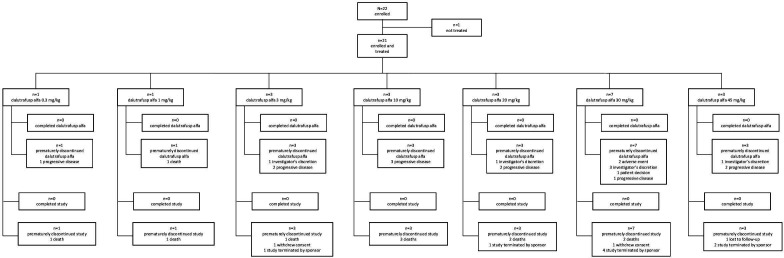

Of the 22 patients enrolled, 21 (95%) received at least one dose of dalutrafusp alfa. One patient did not receive dalutrafusp alfa when pre-infusion safety laboratory evaluations on study Day 1 precluded the patient’s eligibility. Patient disposition is presented in figure 1. Of the 21 patients, 1, 1, 3, 3, 3, 7, and 3 patients received dalutrafusp alfa at doses of 0.3, 1, 3, 10, 20, 30, and 45 mg/kg, respectively. Patients received between 1 and 14 doses of dalutrafusp alfa (median three doses). Most patients were female (71.4%), White (85.7%), and all had an ECOG status of 1 or less (ECOG=0, 2 (9.5%); ECOG=1, 19 (90.5%)). Median age at baseline was 65 years. Patients had varying malignancy types and best responses to treatment at baseline. The most common malignancy type was colon cancer (19.0%), and most patients had PD or stable disease (SD) as a best response (table 1).

Figure 1.

Patient disposition (all-enrolled analysis set).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics (safety analysis set)

| Characteristics | Dalutrafusp alfa doses (mg/kg) | |||||||

| 0.3 n=1 |

1 n=1 |

3 n=3 |

10 n=3 |

20 n=3 |

30 n=7 |

45 n=3 |

Total N=21 |

|

| Age, years, median (range) | 58 | 67 | 72 (60–77) | 64 (62–83) | 59 (56–70) | 55 (36–77) | 67 (66–79) | 65 (36–83) |

| Sex, female, n (%) | 0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 15 (71.4) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||||||

| Black | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 (14.3) |

| White | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 18 (85.7) |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (range) | 26.0 | 22.7 | 28.7 (22.0–34.7) | 20.3 (19.9–21.8) | 40.4 (32.1–40.8) | 33.6 (26.7–42.2) | 26.6 (26.3– 28.2) | 28.7 (19.9–42.2) |

| ECOG performance status, n (%) | ||||||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 (9.5) |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 19 (90.5) |

| Number of prior anticancer regimens, median (range) | 4 | 3 | 4 (2–7) | 3 (3–3) | 7 (3–16) | 4 (1–8) | 6 (4–6) | 4 (1–16) |

| Malignancy type (best response) | ||||||||

| Colon | 1 (PD) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (NA) | 2 (SD/PD) | 4 (19.0) |

| Bladder | 0 | 1 (NA) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.8) |

| Renal cell | 0 | 0 | 1 (SD) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (9.5) |

| NSCL | 0 | 0 | 1 (SD) | 0 | 1 (SD) | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.8) |

| Adrenal | 0 | 0 | 1 (PD) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.8) |

| Pancreatic | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (PD/PD/PD) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (14.3) |

| Appendiceal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (PD) | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.8) |

| Ovarian | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (SD) | 1 (SD) | 1 (PD) | 3 (14.3) |

| Liposarcoma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (SD) | 0 | 1 (4.8) |

| Endometrial | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (PD/PR) | 0 | 2 (9.5) |

| Rectal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (NA) | 0 | 1 (4.8) |

| Breast | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (NA) | 0 | 1 (4.8) |

BMI, body mass index; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; NA, not available (patient did not make it to the first response); NSCL, non-small cell lung; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

Treatment exposure

The overall median duration of dalutrafusp alfa treatment was 4.1 weeks (range 0.1–26.3), although exposure varied widely among dose levels: 0.3 mg/kg, 4.1 weeks; 1 mg/kg, 2.1 weeks; 3 mg/kg, 9.9 weeks (range 6.1–10.1); 10 mg/kg, 4.1 weeks (range 3.6–4.1); 20 mg/kg, 4.7 weeks (range 4.1–9.1); 30 mg/kg, 4 weeks (range 0.1–26.3); and 45 mg/kg, 4.3 weeks (range 4.1–6.0).

Safety

Every patient had at least one AE, all of which were treatment emergent. The most common AEs were fatigue (47.6%), nausea (33.3%), diarrhea (28.6%), and vomiting (28.6%; table 2). Nine of 21 (42.9%) patients had either a Grade 3 or 4 AE. Ten (47.6%) deaths were observed in this study. Two (9.5%) patients died due to AEs deemed unrelated to study drug: one from pulmonary embolism (resulting from the underlying malignancy) and the other from PD (table 2). Eight deaths occurred more than 30 days after the last dose of study drug; of these, seven deaths were due to PD of underlying malignancy, and one death occurred during survival follow-up, the cause of which was unknown. The most common AEs occurring in three or more patients and considered related to study drug were arthralgia (14.3%), nausea (14.3%), and vomiting (14.3%). Nine (42.9%) patients had serious AEs (SAEs) during the study, with pleural effusion reported in two patients (one each in 20 and 30 mg/kg dose groups). The following SAEs were reported in one patient each: abdominal pain, anemia, aortic embolus, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia, PD, fatigue, headache, pulmonary embolism, fever, thrombocytopenia, tumor pain, and vomiting. The only SAE considered related to dalutrafusp alfa was thrombocytopenia (see further detail in the Supplemental Material). Dalutrafusp alfa was discontinued in all 21 patients: 2 (9.5%) due to AEs, 1 (4.8%) due to death, 6 (28.6%) due to investigator’s discretion, 1 (4.8%) due to patient’s decision, and 11 (52.4%) due to PD (figure 1). Four (19%) patients had at least one AE leading to temporary interruption of dalutrafusp alfa. These AEs included iron-deficiency anemia, sinus tachycardia, fever, COVID-19 pneumonia, infusion-related reactions, and headache.

Table 2.

Safety summary and incidence of AEs of any grade observed in at least 5% of the study population

| Dalutrafusp alfa doses (mg/kg) | ||||||||

| 0.3 n=1 |

1 n=1 |

3 n=3 |

10 n=3 |

20 n=3 |

30 n=7 |

45 n=3 |

Total N=21 (n [%]) |

|

| AE | ||||||||

| Grade 1 or 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 10 (47.6) |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 9 (42.9) |

| SAE | ||||||||

| Grade 1 or 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 (14.3) |

| Grade 3 or 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 4 (19.0) |

| AEs leading to discontinuation of dalutrafusp alfa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 (9.5) |

| AEs leading to interruption of dalutrafusp alfa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 4 (19.0) |

| AEs leading to death | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (9.5) |

| Incidence of AEs of any Grade observed in at least 5% of the study population | ||||||||

| Fatigue | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 10 (47.6) |

| Nausea | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 7 (33.3) |

| Diarrhea | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 6 (28.6) |

| Vomiting | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 6 (28.6) |

| Fever | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 5 (23.8) |

| Abdominal pain | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 (19.0) |

| Anemia | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 (19.0) |

| Arthralgia | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 (19.0) |

| Decreased appetite | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 (19.0) |

| Dyspnea | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 (14.3) |

| Abdominal distension | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 (9.5) |

| ALT increased | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 (9.5) |

| AST increased | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 (9.5) |

| Back pain | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 (9.5) |

| Constipation | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (9.5) |

| Contusion | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 (9.5) |

| Dehydration | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 (9.5) |

| Dizziness | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (9.5) |

| Gait disturbance | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (9.5) |

| Headache | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 (9.5) |

| Lymphocyte count decreased | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (9.5) |

| Pleural effusion | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 (9.5) |

| Pruritus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 (9.5) |

| Stomatitis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 (9.5) |

| Tumor pain | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 (9.5) |

| Weight decreased | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 (9.5) |

AE, adverse event; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; SAE, serious AE.

Laboratory abnormalities that were Grade 3 or 4 included anemia, platelet decrease, alkaline phosphatase increase, gamma-glutamyl transferase increase, and hyponatremia. Each of these laboratory abnormalities occurred in two patients or fewer (<10%) and are summarized in Supplemental Table S1.

There was no DLT reported. Since no DLTs occurred up to the highest dose evaluated, and the highest-dosed cohort was not fully enrolled, the MTD could not be determined in this study.

Pharmacokinetics and immunogenicity

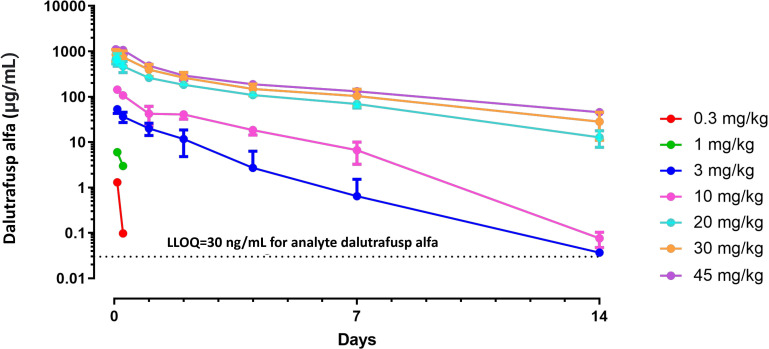

The increase in dalutrafusp alfa plasma exposure was more than dose proportional in the 0.3–20 mg/kg dose range and was approximately dose proportional at doses above 20 mg/kg (table 3, figure 2).

Table 3.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of dalutrafusp alfa in patients with advanced solid tumors (pharmacokinetic analysis set)

| Dalutrafusp alfa doses (mg/kg) | |||||||

| Pharmacokinetic parameter | 0.3 n=1 |

1 n=1 |

3 n=3 |

10 n=3 |

20 n=3 |

30 n=7 |

45 n=3 |

| Cmax, μg/mL, mean (%CV) | 1.3 | 6.0 | 53.1 (18.9) | 144 (0.4) | 703 (26.8) | 858 (24.0) | 1180 (11.0) |

| Tmax, h, median, (Q1, Q3) | 2.08 | 2.00 | 1.85 (1.83, 2.05) | 1.97 (1.83, 3.00) | 1.75 (1.07, 1.82) | 1.45 (1.07, 3.12) | 1.12 (1.03, 4.93) |

| Ctrough, μg/mL, mean (%CV) | NE* | NE* | 0.037† | 0.076 (37.2)‡ | 15.1 (30.5)‡ | 32.1 (51.1)§ | 45.5 (9.5) |

| AUCtau, μg∙h/mL, mean (%CV) | NE* | NE* | 1480 (51.4) | 5310 (11.2) | 33,500 (4.9) | 51,600 (31.6)¶ | 64,900 (15.1) |

*Ctrough at 0.3 mg/kg and 1 mg/kg were below the limit of quantitation and thus AUCtau cannot be estimated robustly.

†n=1.

‡n=2.

§n=5.

¶n=6.

AUCtau, area under the concentration versus time curve over the dosing interval; Cmax, maximum observed drug concentration; Ctrough, trough drug concentration; CV, coefficient of variation; h, hours; NE, not estimated; Q, quartile; Tmax, time to reach Cmax.

Figure 2.

Mean (SD) dalutrafusp alfa plasma concentrations versus time during Cycle 1 (semi-log scale). LLOQ, lower limit of quantitation.

Thirty-eight per cent of patients (n=8) evaluated across the dose levels developed ADAs. The earliest ADA onset on-treatment was 14 days after the first dose (Supplemental Table S2). There was no clear impact of ADAs on dalutrafusp alfa exposure in the small sample size evaluated.

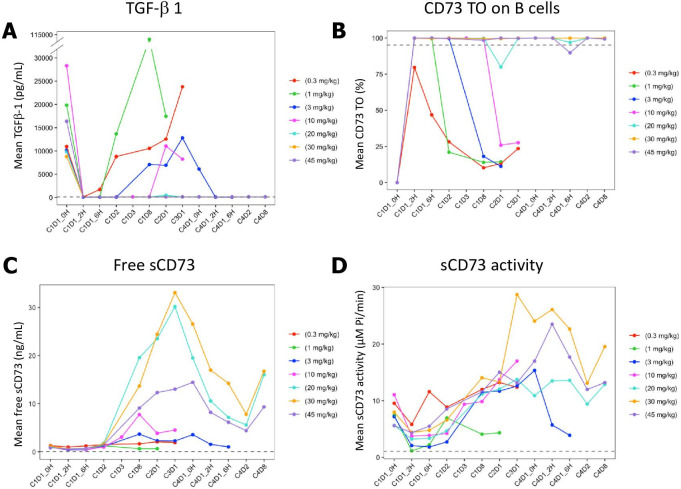

Pharmacodynamic biomarker testing

A dose-dependent decrease in TGF-β 1/2/3 in plasma was observed on-treatment (figure 3 and Supplemental Figures S3A and S3B). There was no detectable TGF-β at the 20 mg/kg dose level and above at 2 hours after first dose and for the duration of the Q2W dosing interval. A dose-dependent increase in CD73 TO on B cells and CD8+ T cells was also observed with treatment, and complete TO in peripheral blood was achieved at 20 mg/kg and above at 2 hours after first dose for the duration of the Q2W dosing interval (figure 3B and online supplemental figure 3C). Free sCD73 decreased at 2 hours after first dose, while remaining above the LLOQ, and then increased above baseline after 24 hours postdose at the 3 mg/kg dose level and above. The sCD73 activity also increased similarly to free sCD73 levels (figure 3C and D).

Figure 3.

Peripheral TGF-β, CD73 TO, and sCD73 levels across all dalutrafusp alfa cohorts. (A) TGF-β1 in plasma on-treatment with dalutrafusp alfa. (B) CD73 TO on B cells in whole blood on-treatment with dalutrafusp alfa. (C) Free sCD73 in plasma on-treatment with dalutrafusp alfa. (D) sCD73 activity in plasma on-treatment with dalutrafusp alfa. CD, cluster of differentiation; s, soluble; TGF, tumor growth factor; TO, target occupancy.

Clinical efficacy

Of the 21 patients who received dalutrafusp alfa, 17 reached the first response assessment. The overall best response of complete response (CR), partial response (PR), SD, and PD were observed in 0, 1 (4.8%), 7 (33.3%), and 9 (42.9%) patients, respectively. Overall response rate (ORR; CR+PR; 90% CI) was 4.8% (0.2% to 20.7%), and disease control rate (DCR; CR+PR+SD) was 38.1% (20.6% to 58.3%). Among the eight patients with disease control, two patients with best response of SD had disease progression (at 2.4 and 3.7 months), three patients with best response of SD started new anticancer therapy (at 1.1 and 1.3 months), and three patients censored due to study termination.21 The median duration of disease control by Kaplan-Meier estimate was not reached.

The patient with confirmed PR (100% tumor reduction from baseline and presence of a stable non-target bone lesion) had Stage 4 endometrial carcinoma (microsatellite stable, programmed death ligand-1 <1% by Dako immunohistochemistry 22C3) with one previous line of chemotherapy (paclitaxel/carboplatin), where best response was SD. This patient was receiving dalutrafusp alfa at the 30 mg/kg dose level with a time to first response at study Day 84. After 26 weeks (last dose study Day 184), dalutrafusp alfa was discontinued due to thrombocytopenia (Grade 4; study Day 191), and the patient was treated with a platelet transfusion, one dose of intravenous immunoglobulin, and a course of oral dexamethasone. The thrombocytopenia was downgraded to Grade 3 on study Day 193 and resolved on study Day 197.

Discussion

Dalutrafusp alfa is a first-in-class, bifunctional, monoclonal antibody targeting CD73 and TGF-β, two molecules involved in immunosuppressive pathways. This first-in-human study indicated that dalutrafusp alfa can be safely administered at doses of 0.3–45 mg/kg intravenously Q2W. Fourteen (66.7%) patients had an AE considered related to dalutrafusp alfa, with 2 (9.5%) patients having a Grade 3 or 4 AE. Of the 21 patients in whom dalutrafusp alfa was discontinued, 2 (9.5%) discontinued due to AEs, 1 (4.8%) due to death, 6 (28.6%) due to investigator’s discretion (n=4 clinical disease progression, n=1 patient deterioration, n=1 patient started an alternative anticancer therapy), 1 (4.8%) due to patient’s decision, and 11 (52.4%) due to PD. Fatigue, nausea, diarrhea, and vomiting were the most common AEs in this study. There was no DLT reported, and the MTD could not be determined.

One patient who achieved a PR discontinued dalutrafusp alfa due to an AE of Grade 4 thrombocytopenia after 26 weeks of study treatment. This patient recovered after clinical intervention. There were no additional AEs of thrombocytopenia or laboratory platelet abnormalities reported for other patients in the study. The mechanism of thrombocytopenia, and its association with ADAs in this patient, remain unclear.

The increase in dalutrafusp alfa plasma exposure was more than dose proportional at doses in the 0.3–20 mg/kg dose range and was dose proportional at doses above 20 mg/kg. This suggests that dalutrafusp alfa undergoes target-mediated drug disposition, which is saturated at doses above 20 mg/kg.

Consistent with the pharmacokinetic findings, dalutrafusp alfa fully suppressed free peripheral TGF-β 1/2/3 and achieved full CD73 occupancy on B cells and CD8+ T cells at the 20 mg/kg dose level and above for the duration of the Q2W dosing interval. However, free sCD73 and corresponding sCD73 activity increased on-treatment with dalutrafusp alfa. A transient decrease in sCD73 levels and its activity was detected at the first day of Cycle 1 at all doses; however, sCD73 levels remained above the LLOQ. Free sCD73 levels and enzymatic activity increased above baseline levels after the second day of Cycle 1. This observation was unexpected. In contrast, biomarker data for oleclumab22 and BMS986179,23 both of which are also anti-CD73 monoclonal antibodies, suggested a persistent decrease in detection of free sCD73 in patients administered these drugs for the duration of the dosing intervals. A follow-up analysis demonstrated that total plasma levels of sCD73 increased in patients treated with BMS986179.24 The impact of oleclumab and BMS986179 on sCD73 activity has not been published. The increase in total sCD73 may be a compensatory upregulation resulting from CD73 inhibition. The apparent increase of free sCD73 on dalutrafusp alfa treatment, but not oleclumab or BMS986179 treatment, may be due to the lower monovalent binding affinity of dalutrafusp alfa, resulting in the loss of dalutrafusp alfa binding to sCD73. The impact of the increased levels of sCD73 and the increase in CD73 enzymatic activity in blood with dalutrafusp alfa treatment on safety and efficacy needs to be further characterized.

Preliminary clinical activity of dalutrafusp alfa monotherapy was observed in this population of patients with advanced solid tumors, with an ORR of 4.8% and DCR of 38.1%. Single-agent activity was observed in one patient with endometrial cancer who achieved PR.

This study has several limitations. The median duration of exposure to dalutrafusp alfa was 4.1 weeks, ranging from 0.1–26.3 weeks. The sample size was also small, with six of seven treatment groups having fewer than five patients each. In this study, only blood biomarkers of dalutrafusp alfa were evaluated, as tissue biopsies pretreatment/post-treatment were not available.

In conclusion, dalutrafusp alfa was well tolerated by patients with advanced solid tumors up to 45 mg/kg intravenously Q2W with no DLT reported. The MTD could not be determined in this study, and preliminary clinical activity was observed. Peripheral TGF-β 1/2/3 was undetectable, and complete occupancy of CD73 on B cells and CD8+ T cells was achieved in patients treated with dalutrafusp alfa at doses 20 mg/kg or greater, consistent with saturation of the target-mediated drug disposition observed at these dose levels.

Clinical development of dalutrafusp alfa continues; dalutrafusp alfa will be evaluated in combination with balstilimab (an anti-programmed cell death protein-1 monoclonal antibody) ± chemotherapy in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Additional clinical studies exploring the combination of dalutrafusp alfa with checkpoint inhibitors ± chemotherapy are under evaluation. The rationale for these studies is based on preclinical data demonstrating the potential of dalutrafusp alfa to overcome therapeutic resistance in the tumor microenvironment.5 7 15 25–27

jitc-2022-005267supp002.pdf (1.6MB, pdf)

Acknowledgments

Medical writing support was provided by Gregory Suess of AlphaScientia, and was funded by Gilead Sciences. We would like to thank Xiaoyun Yang, Ping Yi, Rick Sorensen, Biao Li, and Kai-Wen Lin for generating and analyzing the biomarker data and Giuseppe Papalia for interpreting the surface plasmon resonance binding data.

Footnotes

Contributors: Responsible for overall content as the guarantor: AWT. Conceptualization: MZ, JMJ, SS, TC. Resources: AS, MZ, C-HH, JMJ, SS, AAO, TC. Data curation: AS, MZ, C-HH, JMJ, TC, JS. Formal analysis: AS, MZ, C-HH, SZ, JMJ, AAO, TC. Supervision: AWT, AS, MZ, C-HH, TT, JMJ, AAO, TC, JS. Investigation: AWT, MG, KMM, AS, MZ, C-HH, JMJ, AAO, TC, JS. Visualization: AS, MZ, SZ, TC. Methodology: AWT, MG, KMM, AS, MZ, JMJ, AAO, TC. Writing—original draft: MG, AS, MZ, JMJ, SS, AAO, TC. Project administration: AS, TC. Writing—review and editing: AWT, MG, AS, MZ, C-HH, SZ, JMJ, SS, AAO, TC. All authors approved the submitted version of this paper.

Funding: Funding for this project was provided by Gilead Sciences. Funding for this analysis was provided by Gilead Sciences.

Competing interests: AWT reports being a consultant for AbbVie, Aclaris Therapeutics, Agenus, Asana Biosciences, Ascentage Pharma, Axlmmune, Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Gilde Healthcare Partners, HBM Partners, Immuneering Corporation, Immunomet Therapeutics, Impact Therapeutics US, Karma Oncology B.V., Lengo Therapeutics, Mekanistic Therapeutics, Menarini Ricerche, Mersana Therapeutics, Mirati Therapeutics, Nanobiotix, Ocellaris Pharma, Partner Therapeutics, Pfizer, Laboratories Pierre Fabre, Ryvu Therapeutics, Seattle Genetics, SK Life Science, SOTIO Biotechnology, Spirea Limited, Sunshine Guojian Pharmaceutical (Shanghai), Transcenta Therapeutics, and Trillium Therapeutics; reports being an advisory board member for Adagene, Aro Biotherapeutics, Bioinvent, Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH, Deka Biosciences, Eleven Biosciences, Elucida Oncology, EMD Serono/Merck KGaA, Hiber Cell, Ikena Oncology, Immunome, Janssen Global Services, NBE Therapeutics, Pelican, Pieris Pharma, PYXIS Oncology, Vincerx Pharma, ZielBio, and Zymeworks Biopharmaceuticals; and reports receiving compensation for open studies from Gilead Sciences. MG reports potential conflicts with AbbVie, Aeglea BioTherapeutics, Agenus, Arcus Biosciences, Astex Pharmaceuticals, BeiGene, BluePrint Medicines, BMS Amgen, Calithera Biosciences, CellDex Therapeutics, Corcept Therapeutics, Clovis Oncology, Deciphera Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, Endocyte, Five Prime Therapeutics, Genocea Biosciences, Medimmune, Merck, Neon, Plexxikon, Revolution Medicines, Seattle Genetics, EMD Serono, SynDevRx, Tesaro, Tolero Pharmaceuticals, TRACON Pharmaceuticals, and Salarius Pharmaceuticals; and reports being a consultant for Agenus, Daiichi Sankyo, Imaging Endpoints, Salarius Pharmaceuticals, and TRACON Pharmaceuticals. KMM reports no conflicts of interest. AS, SZ, TT, JMJ, SS, AAO, TC reports being an employee of Gilead Sciences, and reports stock ownership in Gilead Sciences. MZ and C-HH reports being a former employee of Gilead Sciences, and a shareholder of Gilead Sciences. JS reports being a part-time employee of Dialectic Therapeutics; reports common stock ownership in AbbVie, Abbott Laboratories, Bristol Myers Squibb, Intuitive Surgical, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals; reports stock option ownership in Dialectic Therapeutics; reports being an advisory board member for Synlogic and Binhui Biopharmaceuticals; and reports being a site principal investigator for studies funded by Agenus Bio, Alkermes, Arvinas, AstraZeneca, BerGenBio, Daiichi Sankyo, Epizyme, Gan & Lee Pharmaceuticals, Genmab, GlaxoSmithKline, Harpoon Therapeutics, Hutchison Medipharma, Jounce, Mirati Therapeutics, Mundipharma, Laekna Limited, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Odonate Therapeutics, Onconova Therapeutics, ORIC Pharma, Pfizer, Rgenix, Shasqi, Surface Oncology, Synlogic Therapeutics, Takeda Pharmaceutical, and Xencor.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Anonymized individual patient data will be shared upon request for research purposes dependent upon the nature of the request, the merit of the proposed research, the availability of the data, and its intended use. More information on data transparency from Gilead Sciences, Inc., can be found at https://www.gileadclinicaltrials.com/transparency-policy/

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by site-related Institutional Review Board and Independent Ethics Committee. ID numbers were not provided.

References

- 1.Stultz J, Fong L. How to turn up the heat on the cold immune microenvironment of metastatic prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2021;24:697–717. 10.1038/s41391-021-00340-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang R, Elsaadi S, Misund K, et al. Conversion of ATP to adenosine by CD39 and CD73 in multiple myeloma can be successfully targeted together with adenosine receptor A2A blockade. J Immunother Cancer 2020;8:e000610. 10.1136/jitc-2020-000610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morello S, Capone M, Sorrentino C, et al. Soluble CD73 as biomarker in patients with metastatic melanoma patients treated with nivolumab. J Transl Med 2017;15:244–44. 10.1186/s12967-017-1348-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hay CM, Sult E, Huang Q, et al. Targeting CD73 in the tumor microenvironment with MEDI9447. Oncoimmunology 2016;5:e1208875. 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1208875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allard B, Pommey S, Smyth MJ, et al. Targeting CD73 enhances the antitumor activity of anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 mAbs. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19:5626–35. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Häusler SF, Del Barrio IM, Diessner J, et al. Anti-CD39 and anti-CD73 antibodies A1 and 7G2 improve targeted therapy in ovarian cancer by blocking adenosine-dependent immune evasion. Am J Transl Res 2014;6:129–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stagg J, Divisekera U, McLaughlin N, et al. Anti-CD73 antibody therapy inhibits breast tumor growth and metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107:1547–52. 10.1073/pnas.0908801107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reinhardt J, Landsberg J, Schmid-Burgk JL, et al. MAPK signaling and inflammation link melanoma phenotype switching to induction of CD73 during immunotherapy. Cancer Res 2017;77:4697–709. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu X-X, Chen Y-T, Feng B, et al. Expression and clinical significance of CD73 and hypoxia-inducible factor-1α in gastric carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19:1912–8. 10.3748/wjg.v19.i12.1912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Formenti SC, Lee P, Adams S, et al. Focal irradiation and systemic TGFβ blockade in metastatic breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24:2493–504. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-3322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haque S, Morris JC. Transforming growth factor-β: a therapeutic target for cancer. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2017;13:1741–50. 10.1080/21645515.2017.1327107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ravi R, Noonan KA, Pham V, et al. Bifunctional immune checkpoint-targeted antibody-ligand traps that simultaneously disable TGFβ enhance the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy. Nat Commun 2018;9:741. 10.1038/s41467-017-02696-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cui W, Fowlis DJ, Bryson S, et al. TGFbeta1 inhibits the formation of benign skin tumors, but enhances progression to invasive spindle carcinomas in transgenic mice. Cell 1996;86:531–42. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80127-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gatti-Mays ME, Gameiro SR, Ozawa Y, et al. Improving the odds in advanced breast cancer with combination immunotherapy: stepwise addition of vaccine, immune checkpoint inhibitor, chemotherapy, and HDAC inhibitor in advanced stage breast cancer. Front Oncol 2020;10:581801. 10.3389/fonc.2020.581801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lan Y, Zhang D, Xu C, et al. Enhanced preclinical antitumor activity of M7824, a bifunctional fusion protein simultaneously targeting PD-L1 and TGF-β. Sci Transl Med 2018;10:aan5488. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aan5488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knudson KM, Hicks KC, Luo X, et al. M7824, a novel bifunctional anti-PD-L1/TGFβ trap fusion protein, promotes anti-tumor efficacy as monotherapy and in combination with vaccine. Oncoimmunology 2018;7:e1426519. 10.1080/2162402X.2018.1426519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strauss J, Heery CR, Schlom J, et al. Phase I trial of M7824 (MSB0011359C), a bifunctional fusion protein targeting PD-L1 and TGFβ, in advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24:1287–95. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Massagué J, Andres J, Attisano L. TGF‐β receptors. Mol Reprod Dev 1992;32:99–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simon R, Freidlin B, Rubinstein L, et al. Accelerated titration designs for phase I clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 1997;89:1138–47. 10.1093/jnci/89.15.1138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009;45:228–47. 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Data on f . Duration of disease control all enrolled analysis set. In: Gilead Sciences Inc., 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Overman MJ, LoRusso P, Strickler JH. Safety, efficacy and pharmacodynamics (PD) of MEDI9447 (oleclumab) alone or in combination with durvalumab in advanced colorectal cancer (CRC) or pancreatic cancer (panc). ASCO 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siu LL, Burris H, DT L. Abstract CT180: preliminary phase 1 profile of BMS-986179, an anti-CD73 antibody, in combination with nivolumab in patients with advanced solid tumors. AACR 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao Y, Gu H, Postelnek J, et al. Fit-for-purpose protein biomarker assay validation strategies using hybrid immunocapture-liquid chromatography-tandem-mass spectrometry platform: quantitative analysis of total soluble cluster of differentiation 73. Anal Chim Acta 2020;1126:144–53. 10.1016/j.aca.2020.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Young A, Ngiow SF, Barkauskas DS, et al. Co-Inhibition of CD73 and A2aR adenosine signaling improves anti-tumor immune responses. Cancer Cell 2016;30:391–403. 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.06.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ravi R, Noonan KA, Pham V, et al. Bifunctional immune checkpoint-targeted antibody-ligand traps that simultaneously disable TGFβ enhance the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy. Nat Commun 2018;9:741. 10.1038/s41467-017-02696-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takaku S, Terabe M, Ambrosino E, et al. Blockade of TGF-beta enhances tumor vaccine efficacy mediated by CD8(+) T cells. Int J Cancer 2010;126:1666–74. 10.1002/ijc.24961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

jitc-2022-005267supp001.pdf (2.8MB, pdf)

jitc-2022-005267supp002.pdf (1.6MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Anonymized individual patient data will be shared upon request for research purposes dependent upon the nature of the request, the merit of the proposed research, the availability of the data, and its intended use. More information on data transparency from Gilead Sciences, Inc., can be found at https://www.gileadclinicaltrials.com/transparency-policy/