Abstract

Paneth cells are versatile secretory cells located in the crypts of Lieberkühn of the small intestine. In normal conditions, they function as the cornerstones of intestinal health by preserving homeostasis. They perform this function by providing niche factors to the intestinal stem cell compartment, regulating the composition of the microbiome through the production and secretion of antimicrobial peptides, performing phagocytosis and efferocytosis, taking up heavy metals, and preserving barrier integrity. Disturbances in one or more of these functions can lead to intestinal as well as systemic inflammatory and infectious diseases. This review discusses the multiple functions of Paneth cells, and the mechanisms and consequences of Paneth cell dysfunction. It also provides an overview of the tools available for studying Paneth cells.

Keywords: paneth cells, gut homeostasis, infection, antimicrobial peptides

Subject Categories: Digestive System

This Review discusses biological functions of Paneth cells and their importance for intestinal homeostasis and organismal health.

Glossary

- PCs

Paneth cells are secretory cells located in the crypts of Lieberkühn, adjacent to the intestinal stem cells. They produce antimicrobial peptides and proteins and other components that are important in host defense and immunity.

- α‐defensins

Enteric α‐defensins are antimicrobial peptides stored in the secretory granules of PCs. They are responsible for most of the antimicrobial activity of PCs.

- LYZ

Lysozyme is the first antimicrobial peptide discovered in PCs and is widely used as a PC marker in the small intestine.

- Wnt/β‐catenin signaling pathway

Wingless‐related integration site (Wnt)/β‐catenin signaling pathway is a signal transduction pathway regulating intestinal stem cell self‐renewal and differentiation. The Wnt/β‐catenin pathway is most active at the intestinal crypt base.

- Notch signaling

Notch signaling in the gut directs the differentiation of progenitor cells into absorptive cells (enterocytes) by inhibiting secretory cell differentiation (Goblet cells, enteroendocrine cells, tuft cells, and PCs) via the expression of the transcription factor Hairy and enhancer of split 1 (HES1).

- miRNA

microRNA is a small single‐stranded non‐coding RNA molecule that regulates gene expression on a post‐transcriptional level.

- mTORC1

Mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 is a serine/threonine protein kinase and serves as a sensor for a wide range of environmental factors, for example, nutrient availability. The protein responds to environmental triggers by adapting transcription, translation and autophagy, and can thereby regulate several cellular processes.

- Autophagy

Autophagy is a process by which a cell removes damaged or unnecessary components via lysosome‐dependent degradation. It is a fundamental cell survival mechanism contributing to the mobilization of cellular energy stores and is thus critical for maintaining the homeostasis of cells.

- Endoplasmic reticulum

Endoplasmic reticulum is an intracellular organelle that plays a key role in, for example, folding, modifying, and sorting newly synthesized proteins and the synthesis of cellular lipids.

- ER stress

Endoplasmic reticulum stress is induced by the accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins. Cells activate signaling pathways (unfolded protein response; UPR) to deal with ER stress.

- Mucus

The mucus layer in the intestinal epithelium forms a physical and immunological barrier to protect the epithelium from infiltration of microorganisms and other components.

Introduction and definition of Paneth cells

Paneth cells (PCs) are found in the crypts of the small intestine of many mammals (Lueschow & McElroy, 2020). They are highly secretory cells with a lifespan of about 2 months (Ireland et al, 2005). Their secretory function is hallmarked by a pyramidal‐shaped morphology, abundant endoplasmic reticulum (ER), well‐developed Golgi network and apically oriented secretory granules. These granules accumulate antimicrobial peptides and proteins (AMPs), enzymes and growth factors, many of which are crucial in host defense (Ayabe et al, 2000). Hence, PCs might control the composition of the enteric microbiota and maintain gut homeostasis. Alterations in PCs or PC dysfunction contribute to several diseases, for example, graft‐versus‐host disease (GVHD) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (Levine et al, 2013; Deuring et al, 2014). Understanding PCs and expanding the tools to study them is therefore of utmost importance. This review focusses on their biological functions, how they can be modulated by environmental conditions and disease, and the tools available to study them.

PC ontogeny

The enteric epithelium consists of a monolayer of columnar cells with diverse functions and plays a crucial role in metabolism, preserving intestinal homeostasis, and defense of the body (Ali et al, 2020). Its architecture is composed of upright villi interspersed by the crypts of Lieberkühn. The epithelium of the small intestine consists of five main cell types differentiated from Lgr5+ intestinal stem cells (ISCs): enterocytes, goblet cells, enteroendocrine cells, tuft cells, and PCs (Van Der Flier & Clevers, 2009). Due to the daily challenge of food components and bacteria, the epithelium is constantly renewed to maintain homeostasis and preserve the integrity of the intestinal lining (Barker et al, 2012). ISCs are responsible for the rapid renewal and replenishment of the epithelium by forming progenitor cells that can differentiate further. The major part of differentiated cells moves upwards in the villus, with a lifespan of 3–5 days, and are then shed into the lumen at the top of the villus, where they die by a process called anoikis (Cheng & Leblond, 1974). However, PCs move downwards into the crypts of Lieberkühn, where they exert versatile functions, including ISC support. In some mammals, such as humans and mice, PCs are abundant and easy to observe, but in other animals (e.g., pigs), their existence is controversial (Myer, 1982; van der Hee et al, 2018).

PC formation and differentiation

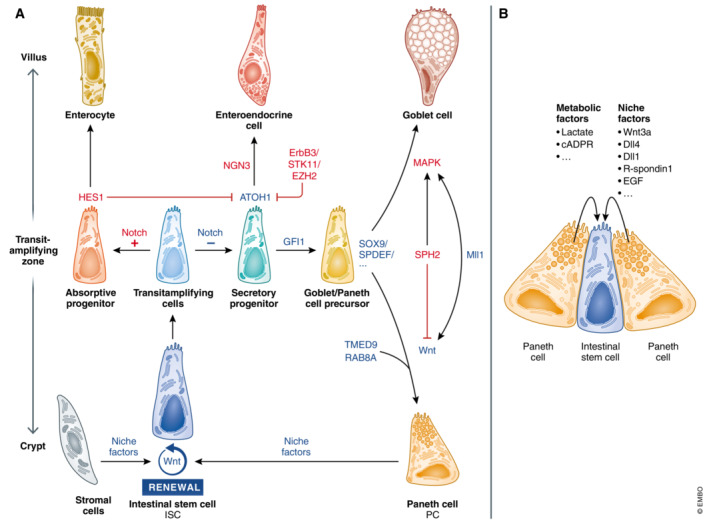

ISCs in the lower part of the crypts give rise to a large pool of transit‐amplifying cells. The most important regulators of ISC activity are Wnt, bone morphogenetic protein (BMP), Notch, and epidermal growth factor (EGF) signaling pathways. These factors are gradually expressed along the villi and crypts (Malijauskaite et al, 2021). Transit‐amplifying cells remain 2 days in the transit‐amplifying zone (higher part of the crypts), where they multiply and mature into differentiated intestinal epithelial cells (IECs, Fig 1) (Van Der Flier & Clevers, 2009).

Figure 1. Intestinal cell differentiation pathways and signals.

(A) Wnt and Notch signals control ISC renewal and differentiation. PCs and for example, pericryptal stromal cells support the stemness of ISCs by providing niche factors. ISCs in the lower part of the crypt give rise to a larger pool of transit‐amplifying cells in the transit‐amplifying zone. Differentiation from transit‐amplifying cells towards secretory or absorptive progenitors is initially controlled by Notch signaling. Cells that receive Notch signals express HES1, a negative regulator of ATOH1, leading to differentiation into absorbing enterocytes. Cells devoid of Notch express ATOH1, a hallmark of secretory cells. GFI1 acts downstream of ATOH1 to select for goblet cell and PC differentiation, as it represses neurogenin 3 (NGN3), a transcription factor involved in enteroendocrine cell differentiation. ErbB3, STK11, and EZH2 influence PC differentiation by reducing ATOH1 levels and affect the numbers and/or location of mature PCs. SOX9 and SPDEF are involved in PC and goblet cell differentiation. Reduced MAPK signaling and increased Wnt signaling (influenced by Wnt regulating factors, e.g., RAB8A, TMED9, SPH2, and Mll1) favor differentiation into PCs instead of goblet cells. (B) PCs support ISCs by providing niche and metabolic factors. Blue – factors that promote PC differentiation, red – factors that inhibit PC differentiation.

The PC differentiation is initially controlled by Notch signaling. Progenitor cells that are deficient in Notch receptor express atonal BHLH transcription factor 1 (ATOH1), the essential driver of secretory cell differentiation (Yang et al, 2001). Progenitor cells with high Notch activity induce HES1, a negative regulator of ATOH1, making them prone to differentiate into absorbing enterocytes. Growth factor independent 1 transcriptional repressor (GFI1) acts downstream of ATOH1 to select for differentiation of goblet cells and PCs, as it transcriptionally represses differentiation towards enteroendocrine cells by repressing the transcription factor neurogenin 3 (Bjerknes & Cheng, 2010).

Thus, factors that affect ATOH1 influence the differentiation towards PCs (and other secretory cells). PKCλ/Ι is such a factor, as it destabilizes EZH2, an ATOH1 suppressor co‐localized with PC markers in the crypts. PKCλ/Ι ΔIEC mice (lacking Prkci, which encodes PKCλ/Ι , specifically in the intestinal epithelium) had reduced ATOH1 and GFI1 crypt levels, and less mature PCs, along with an increase in an intermediate cell‐type positive for both PC and goblet cell markers (Nakanishi et al, 2016). Erb‐b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 3 (ErbB3) and serine/threonine kinase 11 (STK11) block ATOH1 via the PI3K–Akt pathway and PDK4, respectively, suppressing PC differentiation. Interestingly, ErbB3 knockout (KO) mice (ErbB3 KO) had increased lysozyme (LYZ, encoded in human by LYZ, and in mice by Lyz1) expressing PCs but no change in other secretory cells (Almohazey et al, 2017).

ATOH1/GFI1‐positive precursor cells can further differentiate towards PCs, a process that is not fully understood but strongly depends on (1) transcription factors and downstream effectors of Wnt/β‐catenin signaling and (2) factors that can influence Wnt/β‐catenin signaling (van Es et al, 2005; Van Der Flier & Clevers, 2009; Grinat et al, 2022).

Active Wnt signaling promotes PC differentiation. Wnt activation causes stabilization and translocation of β‐catenin to the nucleus, where it interacts with several T cell factor (TCF) molecules to induce a unique differentiation profile. TCF4 is a regulator of PC maturation and induces a PC gene program in the embryonic intestine of mice (van Es et al, 2005). SRY‐Box transcription factor 9 (SOX9) and SAM‐pointed domain containing ETS transcription factor (SPDEF) are involved in PC and goblet cells differentiation (Bastide et al, 2007; Gregorieff et al, 2009). The unique positioning of PCs towards the crypts is tightly regulated by the Wnt target ephrin receptor B3 (EphB3). Pathways downstream of ATOH1 often affect both goblet cells and PCs, and further research is needed to distinguish their differentiation. However, it is known that persistently active Wnt signaling in the secretory progenitors favors PC differentiation (van Es et al, 2005).

Spherocytosis 2 protein (SPH2), ras‐related protein (RAB8A) and Krüppel‐like factor 5 (KLF5) can influence Wnt/β‐catenin signaling. Ablation of SPH2 reduces ERK1/2‐MAPK signaling, corresponding with higher Wnt β‐catenin/TCF4 signaling and differentiation towards PCs (Heuberger et al, 2014). Ablation of RAB8A, a protein involved in Wnt secretion, reduces Wnt signaling and PC number (Das et al, 2015). Deletion of the transcription factor Klf5 reduces PC and goblet cell numbers (Nandan et al, 2014). Also, miRNAs can influence PC function and differentiation; for example, miRNA‐802 represses TMED9, a stimulator of Wnt and LYZ/α‐defensins secretion in PCs (Goga et al, 2021). Besides, the epigenetic factor Mll1 can influence the differentiation towards secretory cells in a dual way. Mll1 is involved in keeping stemness and preventing differentiation but also has a role in determining PC and goblet cell fate by coordinating Wnt and MAPK signaling in the progenitor cells. Mll1 KO mice had increased secretory cells, but impaired PCs and goblet cell specification, as these cells were positive for both PC and goblet cell markers (Grinat et al, 2022).

Paneth cell differentiation is a complex interplay between different factors. Reduced Notch, strong Wnt, and weak MAPK signaling in progenitor cells promote PC differentiation. Notably, most research on PC differentiation and ISC niche has been performed in mice, but there can be differences between species, for example, there are important differences in niche factors needed in human and mouse organoids (Sato et al, 2011b).

PC numbers

Paneth cells increase in the proximal to distal direction of the small intestine, which corresponds with increased bactericidal activity (Nakamura et al, 2020). The number of PCs per crypt in mice vary between strains and the techniques used but are estimated at 5–16 PCs per crypt (Nakamura et al, 2020). Inbred strains under identical housing conditions differ in the number of PCs and the expression of AMPs. For example, 129/SvEv mice have fewer PCs than C57BL/6J mice (Gulati et al, 2012). This identifies a critical role of the host genotype in PC activity and the intestinal microbiota. Such differences might be of interest to search for modifier genes that influence PC numbers and activities, but such inbred strains have been established as homozygous lines and kept in captivity over many decades. This environmental pressure may have led to genetic drifts that have little relevance to natural environments. PC studies on wild mice and wildling mice might be more relevant (but also more complex) than inbred lines kept in captivity.

PC functions in physiology and homeostasis

The best‐known function of PCs is controlling the microbiome composition, but they have much broader functions. PCs can support and communicate with ISCs, they are involved in metal uptake, and can perform phagocytosis, efferocytosis and preserve barrier function.

PCs and the ISC niche: support and communication

The unique crypt morphology of terminally differentiated PCs interspersed between pluripotent ISCs indicates the interactivity of these two crypt cells. The study of developmental issues in villus–crypt proliferation and differentiation led to insights into ISC maintenance and plasticity. One insight is that PCs produce essential niche signals for ISCs: Wnt family member 3A (Wnt3a), EGF, R‐spondin 1, Notch ligands (Dll4 and Dll1), and transforming growth factor α (TGFα) (Sato et al, 2011a). PCs' support of ISC stemness, and ISCs' differentiation into PCs illustrate their strong interdependence (Mei et al, 2020). In vivo PC ablation in three genetic mouse models (CR2‐tox176 mice, Gfi1 mutation, and conditional deletion of Sox9) leads to similar losses in ISCs (Sato et al, 2011a). The dependency of ISC stemness on PCs has also been shown in vitro, as the absence of PCs largely prevents organoid formation from ISCs. However, the effect on ISCs seems to depend on the PC‐ablation model: loss of Atoh1 in the gut induced PC ablation but did not affect the number of ISCs (Durand et al, 2012). Some studies indicated a role for pericryptal stromal cells in providing niche factors (Durand et al, 2012; McCarthy et al, 2020). Moreover, PC ablation by using a diphtheria toxin receptor gene inserted into the Lyz1 locus led to the appearance of alternative niche cells (enteroendocrine and tuft cells) that provided niche factors to ISCs (Van Es et al, 2019).

Certain bacterial communities (such as Bifidobacterium spp. and Lactobacillus spp.) can communicate with ISCs via PCs (Lee et al, 2018). They produce lactic acid in the lumen, which binds to the recently discovered lactate G‐protein‐coupled receptor (Gpr81, encoded by Hcar1) on PCs. This interaction triggers PCs to increase Wnt3a expression and then stimulates Wnt signaling in ISCs (Lee et al, 2018). PCs can also rely on their glycolytic metabolism to produce lactate, which is then excreted and passed to ISCs. This lactate is oxidized by ISCs to pyruvate and serves as a fuel for the TCA cycle to generate ATP and reactive oxygen species (ROS). The latter is required to keep up high levels of phosphorylated P38, a MAP kinase important for regulation of ISCs self‐renewal, differentiation, and crypt formation (Rodríguez‐Colman et al, 2017). PCs can also serve as sensors of the nutritional status of the organism and communicate it to adjacent ISCs via mTORC1. Caloric restriction attenuates mTORC1 signaling in PCs, followed by increased bone stromal antigen (Bst1) levels. Bst1 is an ectoenzyme that converts NAD+ to cyclic ADP ribose, a paracrine product that promotes ISC self‐renewal, while reducing the pool of more differentiated progenitor cells (Yilmaz et al, 2012). Moreover, in pathological conditions, PCs can de‐differentiate into ISCs (Schmitt et al, 2018). PC–ISC interactions have been reviewed (Mei et al, 2020) and will not be discussed much in this review.

Controlling microbiome composition

Paneth cells are the main producers of AMPs in the gastrointestinal tract, making them key players in sensing and controlling the microbiome composition. Thereby, they can preserve homeostasis and prevent bacteria from crossing the intestinal barrier. PCs produce a unique repertoire of AMPs in the gut, for example, LYZ, α‐defensins (called cryptdins in mice) and cryptdin‐related sequence peptides. AMPs are stored in secretory granules and released at the apex of PCs into the crypt lumen. In addition, PCs also produce AMPs that are not restricted to PCs in the gastrointestinal tract, for example, Regenerating islet‐derived protein 3 gamma (Reg3γ), secretory phospholipase A2 IIA (sPLA2 IIA), and Angiogenin‐4. A review elegantly describes the general intestinal AMPs in detail (Bevins & Salzman, 2011), so this review will focus on the AMPs that are exclusively produced by PCs in the gut.

Action mechanism of PC‐specific AMPs in the gut

LYZ was the first AMP discovered in PCs and is widely used as a PC marker in the ileum (Haber et al, 2018). The most abundant AMPs in PCs are α‐defensins, which are also produced by some myeloid‐derived cells (Selsted & Ouellette, 1995). The structures, action mechanisms, and functions of both AMPs are listed in Table 1. The cryptdin‐related sequence peptides share similarities with α‐defensin in their prosegment but the amount and positioning of the cysteines in the mature part are different.

Table 1.

The structure, mechanisms, and functions of lysozyme and α‐defensins.

| Lysozyme | Structure and antimicrobial activity | β‐1,4‐N‐acetylmuramoylhydrolase: Glycosidase responsible for enzymatic hydrolysis of peptidoglycans. This causes instability in the cell wall particularly of Gram‐positive bacteria | Ragland & Criss (2017) |

| Cationic protein: The cationic structure leads to electrostatic interaction with phospholipids in the bacterial membrane. This results in the formation of pores in the membranes of both Gram‐positive and Gram‐negative bacteria, and subsequent bacterial death | Derde et al (2013), Ragland & Criss (2017) | ||

| Other activities | It also has antiviral, antineoplastic and as antioxidant properties | Sava et al (1989), Croguennec et al (2000), Małaczewska et al (2019) | |

| α‐Defensins | Structure and antimicrobial activity | Mature peptide consisting of six conserved cysteines forming three intramolecular disulfide bonds stabilizing a β‐sheet structure | Selsted & Ouellette (1995) |

| The mature peptide is cationic and amphiphilic, leading to electrostatic interaction with phospholipids in the bacterial membrane. This results in the formation of membrane pores in both Gram‐positive and Gram‐negative bacteria, and subsequent bacterial death | Hadjicharalambous et al (2005) | ||

| Other activities | It also has antiviral, antifungal and antiprotozoal activities | Daher et al (1986), Aley et al (1994), Kai‐Larsen et al (2007) |

In mice, the MGI Genome Browser reports 43 annotated α‐defensin genes, nine cryptdin‐related sequence genes, and 18 α‐defensin pseudogenes (Table 2). Genetic differences in α‐defensins exist among mouse strains, which can affect PC studies in specific mouse backgrounds. Despite the many annotated genes in mice, not all are found at the protein level (Shanahan et al, 2011). The human genome encodes 10 α‐defensins but produces only two enteric α‐defensins (HD5 and HD6) (Patil et al, 2005). However, humans express diverse neutrophilic α‐defensins, which is not the case in mice (Shanahan et al, 2011). Human HD6 differs from other α‐defensins (e.g., cryptdins and HD5) by having an extra antimicrobial function, that is, the formation of self‐assembled peptide nano‐nets to capture bacteria (Chu et al, 2012; Schroeder et al, 2015).

Table 2.

Annotated α‐defensin genes, cryptdin‐related sequence genes, and α‐defensin pseudogenes in the MGI Genome Browser.

| Name | MGI ID | Symbol |

|---|---|---|

| defensin, alpha 1 | MGI:94880 | Defa1 |

| defensin, alpha, 2 | MGI:94882 | Defa2 |

| defensin, alpha, 3 | MGI:94883 | Defa3 |

| defensin, alpha, 4 | MGI:99584 | Defa4 |

| defensin, alpha, 5 | MGI:99583 | Defa5 |

| defensin, alpha, 6 | MGI:99582 | Defa6 |

| defensin, alpha, 7 | MGI:99581 | Defa7 |

| defensin, alpha, 8 | MGI:99580 | Defa8 |

| defensin, alpha, 9 | MGI:99579 | Defa9 |

| defensin, alpha, 10 | MGI:99591 | Defa10 |

| defensin, alpha, 11 | MGI:99590 | Defa11 |

| defensin, alpha, 12 | MGI:99589 | Defa12 |

| defensin, alpha, 13 | MGI:99588 | Defa13 |

| defensin, alpha, 14 | MGI:99587 | Defa14 |

| defensin, alpha, 15 | MGI:99586 | Defa15 |

| defensin, alpha, 16 | MGI:99585 | Defa16 |

| defensin, alpha, 17 | MGI:1345152 | Defa17 |

| defensin, alpha, 20 | MGI:1915259 | Defa20 |

| defensin, alpha, 21 | MGI:1913548 | Defa21 |

| defensin, alpha, 22 | MGI:3639039 | Defa22 |

| defensin, alpha, 23 | MGI:3630381 | Defa23 |

| defensin, alpha, 24 | MGI:3630383 | Defa24 |

| defensin, alpha, 25 | MGI:3630385 | Defa25 |

| defensin, alpha, 26 | MGI:3630390 | Defa26 |

| defensin, alpha, 27 | MGI:3642780 | Defa27 |

| defensin, alpha, 28 | MGI:3646688 | Defa28 |

| defensin, alpha, 29 | MGI:94881 | Defa29, Defa‐rs1 |

| defensin, alpha, 30 | MGI:3808881 | Defa30 |

| defensin, alpha, 31 | MGI:102509 | Defa31Defa‐rs7 |

| defensin, alpha, 32 | MGI:3709042 | Defa32 |

| defensin, alpha, 33 | MGI:5434357 | Defa33 |

| defensin, alpha, 34 | MGI:3709048 | Defa34 |

| defensin, alpha, 35 | MGI:3711900 | Defa35 |

| defensin, alpha, 36 | MGI:5434853 | Defa36 |

| defensin, alpha, 37 | MGI:3705236 | Defa37 |

| defensin, alpha, 38 | MGI:3709605 | Defa38 |

| defensin, alpha, 39 | MGI:3611585 | Defa39 |

| defensin, alpha, 40 | MGI:3708769 | Defa40 |

| defensin, alpha, 41 | MGI:3705230 | Defa41 |

| defensin, alpha, 42 | MGI:3645033 | Defa42 |

| defensin, alpha, 43 | MGI:3648003 | Defa43 |

| defensin, alpha, pseudogene 1 | MGI:3630392 | Defa‐ps1 |

| defensin, alpha, pseudogene 2 | MGI:3832603 | Defa‐ps2 |

| defensin, alpha, pseudogene 3 | MGI:3705791 | Defa‐ps3 |

| defensin, alpha, pseudogene 4 | MGI:3705782 | Defa‐ps4 |

| defensin, alpha, pseudogene 5 | MGI:3705778 | Defa‐ps5 |

| defensin, alpha, pseudogene 6 | MGI:3705855 | Defa‐ps6 |

| defensin, alpha, pseudogene 7 | MGI:3705773 | Defa‐ps7 |

| defensin, alpha, pseudogene 8 | MGI:3832672 | Defa‐ps8 |

| defensin, alpha, pseudogene 9 | MGI:3705785 | Defa‐ps9 |

| defensin, alpha, pseudogene 10 | MGI:3705783 | Defa‐ps10 |

| defensin, alpha, pseudogene 11 | MGI:3705879 | Defa‐ps11 |

| defensin, alpha, pseudogene 12 | MGI:3647175 | Defa‐ps12 |

| defensin, alpha, pseudogene 13 | MGI:3705864 | Defa‐ps13 |

| defensin, alpha, pseudogene 14 | MGI:3705817 | Defa‐ps14 |

| defensin, alpha, pseudogene 15 | MGI:3705808 | Defa‐ps15 |

| defensin, alpha, pseudogene 16 | MGI:3705774 | Defa‐ps16 |

| defensin, alpha, pseudogene 17 | MGI:3705788 | Defa‐ps17 |

| defensin, alpha, pseudogene 18 | MGI:3642785 | Defa‐ps18 |

| defensin, alpha, related sequence 2 | MGI:99592 | Defa‐rs2 |

| defensin, alpha, related sequence 4 | MGI:102512 | Defa‐rs4 |

| defensin, alpha, related sequence 5 | MGI:102511 | Defa‐rs5 |

| defensin, alpha, related sequence 6 | MGI:102510 | Defa‐rs6 |

| defensin, alpha, related sequence 8 | MGI:102508 | Defa‐rs8 |

| defensin, alpha, related sequence 9 | MGI:102507 | Defa‐rs9 |

| defensin, alpha, related sequence 10 | MGI:102516 | Defa‐rs10 |

| defensin, alpha, related sequence 11 | MGI:102515 | Defa‐rs11 |

| defensin, alpha, related sequence 12 | MGI:102514 | Defa‐rs12 |

The α‐defensins are produced as pre‐pro‐peptides. First, they lose their signal peptide while moving from the ER into the secretory vesicles. Then, proteolytic cleavage turns the pro‐defensin into an active α‐defensin. In humans, this proteolytic maturation is executed by trypsin, which is stored as a proenzyme (trypsinogen) in the PCs and activated after or during secretion (Ghosh et al, 2002). In mice, proteolytic maturation is performed by matrix metalloproteinase 7 (MMP7, also known as matrilysin) (Wielockx et al, 2004).

Wilson et al (1999) reported that full‐body MMP7KO mice do not perform terminal maturation (proteolysis) of pro‐defensins in PCs. Hence, MMP7KO mice could be used as a mouse model without biologically active α‐defensins in PCs. Although the microbiota of these mice were shifted, these mice were healthy. However, they are less able to control infection with Salmonella typhimurium. Also, PC‐specific overexpression in mice of human α‐defensin 5 (HD5, considered human ortholog of the mouse α‐defensin genes) led to microbial shifts and protection against S. typhimurium challenge (Salzman et al, 2003). These data reflect the importance of α‐defensins in dealing with foreign bacterial invasions in the gastrointestinal tract (Wilson et al, 1999).

Bacterial signaling in PCs

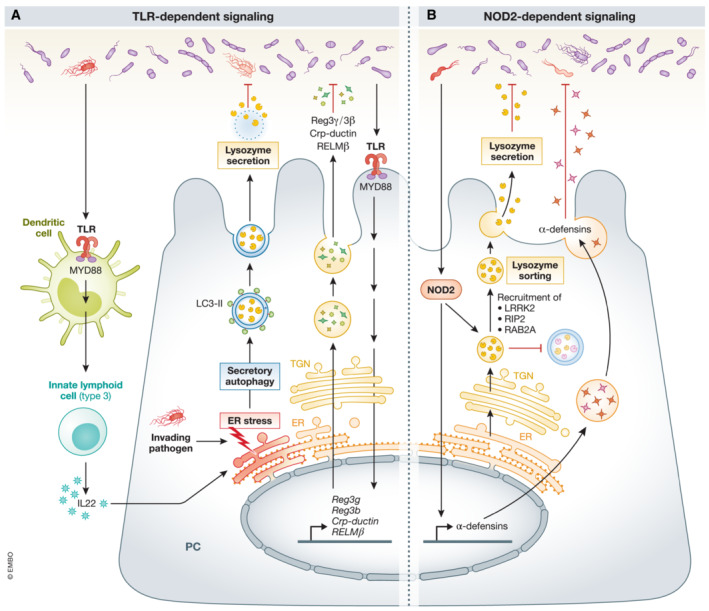

The mechanism of bacterial sensing and signaling in PCs is incompletely understood. Yet, several pathways link bacterial signaling with increased expression and maturation of different AMPs (Fig 2). PCs might sense bacteria directly via myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MYD88) and nucleotide‐binding oligomerization domain containing 2 (NOD2), which trigger the expression of a different subset of AMPs (Vaishnava et al, 2008; Dessein et al, 2009). But they might also be sensed indirectly by PCs, for example, via the MYD88 pathway in dendritic cells (Bel et al, 2017).

Figure 2. Bacterial stimulation of AMP expression and release in PCs.

(A) Intestinal bacteria can communicate directly with PCs via a PC‐autonomous TLR‐MYD88 pathway. This triggers the production and secretion of AMPs (measured in PCs by laser capture microdissection). There is also evidence for indirect extrinsic MyD88 bacterial signaling to activate the secretion of LYZ in PCs: S. typhimurium can stimulate dendritic cells via TLR‐MYD88 signaling, leading to IL22 production in innate lymphoid cells (type 3). IL22, together with invading S. typhimurium in the PC, induce ER stress in these cells, leading to secretory autophagy. The LYZ‐containing secretory autophagosomes have the typical features of an autophagosome, namely, a double membrane labeled with LC3. However, instead of fusing with lysosomes, these LYZ‐containing autophagosomes are released in the lumen of the small intestine. (B) Intestinal bacteria can stimulate NOD2 and increase α‐defensins production and secretion. Bacterial NOD2 activation can also lead to the recruitment of LRRK2, RIP2, and RAB2A onto the surface of DCSGs which coordinate lysozyme sorting.

TLR/MYD88‐dependent bacterial signaling

In mice with genetic MYD88 deficiency, expression of several AMPs in PCs is reduced (Reg3γ, Reg3β, CRP‐ductin, and RELM) and bacterial translocation is increased (Vaishnava et al, 2008). Rescue of MYD88 expression only in PCs (by Defa2‐MyD88 transgenic expression in MYD88KO mice) rescued this phenotype. These elegant experiments illustrated that (1) intestinal bacteria can communicate directly with PCs via cell‐autonomous MYD88 signaling and (2) the MYD88‐dependent antimicrobial response in PCs can prevent bacterial translocation. MyD88‐dependent pathways are essential for host defense against infections by S. aureus, Toxoplasma gondii, and Listeria monocytogenes (Scanga et al, 2002; Seki et al, 2002). There is also evidence for indirect extrinsic MyD88 bacterial signaling to activate the secretion of LYZ via secretory autophagy in PCs. Bel et al (2017) showed that S. typhimurium can invade PCs, damaging the Golgi apparatus and causing ER stress (Bel et al, 2017). This stress can activate secretory autophagy, only with the help of MyD88‐dependent DC signaling, followed by interleukin (IL) 22 production by innate lymphoid cells (type3). The LYZ‐containing secretory autophagosomes have the typical features of autophagosomes, a double membrane labeled with LC3. But, instead of fusing with lysosomes, these autophagosomes are released in the small intestinal lumen.

NOD2‐dependent bacterial signaling

α‐Defensin gene expression seems rather NOD2 dependent, as NOD2KO mice have decreased expression of multiple α‐defensins (Kobayashi et al, 2005; Vaishnava et al, 2008; Tan et al, 2015). However, in contradiction with these previous reports, Menendez et al (2013) observed reduced α‐defensin expression in TLR2, TLR4, and MYD88KO mice, but not in NOD2KO mice (Menendez et al, 2013). LYZ secretion in PCs is also NOD2 dependent. It is synthesized in the ER of PCs and packed in dense core secretory granules (DCSG) at the trans‐Golgi network. Intestinal bacteria activate NOD2, leading to recruitment of leucine‐rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2), receptor interacting serine/threonine kinase 2 (RIP2), and RAB2A on the surface of these DCSGs, which coordinate LYZ sorting towards the lumen (Zhang et al, 2015; Wang et al, 2017a). Yet, other proteins may end up in lysosomes and become degraded. This LYZ‐sorting pathway is LYZ‐specific and does not apply to other AMPs.

Degranulation of AMP‐containing granules in PCs

The release of α‐defensins from the PC secretory granules can be activated by Gram‐negative or ‐positive bacteria, bacterial antigens (LPS, lipoteichoic acid, lipid A, and muramyl dipeptide), and carbamylcholine (Ayabe et al, 2000). This was shown by monitoring the antibacterial activity of ex vivo stimulated crypt cultures. Bacterial killing in the supernatant was not observed when crypts of MMP7KO mice or mice devoid of PCs (CR2‐tox176) were stimulated with the mentioned ligands, emphasizing the antimicrobial role of α‐defensins in PCs. In vivo results showed that PCs are degranulated after stimulation with cholinergic agents, such as carbamylcholine, or by IL4, IL13, IL22, interferon (IFN)α, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α (Satoh et al, 1989; Ozcan et al, 1996; Rumio et al, 2012; Stockinger et al, 2014; Zwarycz et al, 2019). CpG‐oligodeoxynucleotides (TLR9 antagonists) and poly(I):poly(C) (TLR3 agonist) can also stimulate PCs, as they induce degranulation from 3 h postinjection. After oral treatment with LPS (a TLR4 agonist) and flagellin (a TLR5 agonist), late degranulation, mediated by TNFα, was observed in PCs (Rumio et al, 2012).

Phagocytosis of bacteria and efferocytosis in PCs

Another remarkable function of PCs is that they can digest intestinal microorganisms via phagocytosis. Spiral‐formed bacteria and trophozoites of the flagellate Hexamita muris were identified in the digestive vacuoles of PCs from rats (Erlandsen & Chase, 1972). Both intact and partially digested spiral‐formed bacteria and trophozoites were observed, but only in PCs in the gut. The presence of S. typhimurium was also demonstrated in the PCs of infected mice (Bel et al, 2017).

Efferocytosis was recently identified as a new PC function (Shankman et al, 2021) that removes apoptotic cells by phagocytes. To illustrate that PCs can effectively engulf their neighboring apoptotic IECs, they made use of organoids derived from a transgenic mouse strain, where PC membranes were labelled green, and all membranes of all other cells red, in combination with apoptotic dyes. In enteroids irradiated to induce cell death, apoptotic IECs were engulfed by PCs. Also, PC‐specific ablation reduced efferocytosis in intestinal crypts. So, PCs can remove their neighboring apoptotic IECs and in this way reduce local inflammation and contribute to gut homeostasis (Shankman et al, 2021).

Uptake of heavy metals

It has been established that PCs contain heavy metals (e.g., Se and Zn) (Danscher et al, 1985), along with heavy metal ion‐binding proteins, for example, metallothioneins and the Zn‐binding cysteine‐rich intestinal protein (Fernandes et al, 1997). PCs are believed to pick up heavy metals from the lumen and utilize them.

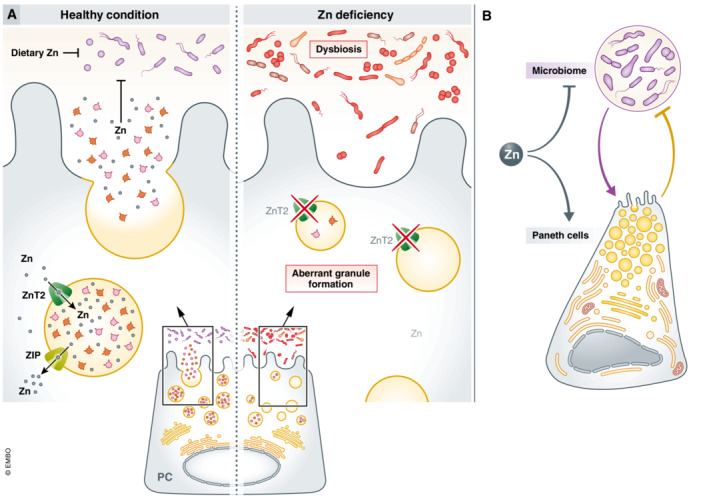

Zn is essential for PC function, as deletion of some zinc importers/exporters causes PC defects. Fourteen Zn‐importing transporters (ZIPs encoded by Slc39a gene family members) and 10 Zn‐exporters (ZnTs, encoded by Slc30a family members) have been described, and several of them are expressed in PCs. An inducible loss‐of‐function of ZIP4 in the murine gut compromises PCs, causing abnormal expression of PC‐related genes (Geiser et al, 2012). Another Zn transporter, ZnT2, is responsible for exporting Zn towards the secretory granules. ZnT2 full KO mice (Slc30a2 KO) have impaired PCs devoid of Zn, disturbed PC granule structure and reduced antimicrobial activity in the ileum, leading to dysbiosis (Podany et al, 2016). These studies confirmed that Zn is not only directly antibacterial but also contributes to PC antimicrobial activities (Fig 3).

Figure 3. The direct and indirect effects (via PCs) of Zn on the microbiome.

(A) In healthy conditions, dietary Zn has a direct antimicrobial effect on the microbiome and inhibits growth of, for example, several Staphylococcus species. Moreover, ZnT2 is responsible for the accumulation of zinc in the secretory granules and for the regulation of AMP secretion in PCs. Upon degranulation, Zn is released in the lumen, leading to an indirect effect (via the PCs) of Zn on the microbiome. Moreover, in vitro assays suggest a role for Zn in stabilization of the antimicrobial HD5 and LYZ. In conditions of Zn deficiency, the direct and indirect antimicrobial effects of Zn on the microbiome are lost or reduced. Deletion of ZnT2 in mice leads to secretory granules devoid of Zn, impaired PCs, disturbed PC granule structure and reduced antimicrobial activity in the ileum, resulting in dysbiosis. (B) Zn can have an antimicrobial effect on the microbiome but is also indispensable for PC functions. PCs can further control the microbiome by the release of AMPs and Zn. The microbiome can in turn stimulate the PCs to produce AMPs.

In PCs, Zn is stored in the secretory granules, but it is not clear why. One explanation is that Zn can stabilize HD5 and chicken egg LYZ, as shown in vitro (Chakraborti et al, 2010; Zhang et al, 2013). Both actions were confirmed in vivo in PCs (Podany et al, 2016; Zhong et al, 2020). It is also speculated that the storage of heavy metals contributes to direct antimicrobial toxicity, as Zn is released upon cholinergic PC stimulation (Giblin et al, 2006). A third potential function, only in mice, is that α‐defensin maturation is Zn‐dependent, as the final proteolytic α‐defensin maturation step is performed by MMP7, a Zn‐dependent metalloprotease (Wilson et al, 1999).

Moreover, Zn is important even in PC survival. In rats and mice, a single injection of the Zn chelator, dithizone, leads to disappearance of PCs and their reappearance after 12–24 h (Sawada et al, 1991). The PC‐specific ablation of PCs by dithizone indicates the strong Zn dependency of PCs.

Preserving the intestinal barrier

Paneth cell‐derived AMPs were found to gather in the mucus to prevent invasion and microbial attachment, augmenting the antimicrobial function of the mucus (Meyer‐Hoffert et al, 2008). Moreover, PC‐deficient mice (Cryptdin2‐tox176) display increased bacterial translocation of commensal bacteria towards the mesenteric lymph nodes (Vaishnava et al, 2008), without adapting the luminal bacterial load in the small intestine (Vaishnava et al, 2008). This illustrates that PCs are essential in preventing bacterial translocation but have no effect on the overall bacterial load in the small intestine. A possible explanation is that PCs regulate the number of mucosa‐associated bacteria, which prevents close contact with the epithelium and subsequent bacterial translocation.

PCs in pathology

Correct PC functioning is important for controlling the microbiota and preserving the crypt niche. This ensures the proper metabolic environment and ISC communication needed for tissue renewal (Lueschow & McElroy, 2020). Failure or disturbance in PC morphology and activity can reduce the secretion of AMPs and stemness factors and increase bacterial translocation. This determines the severity and progression of several gastrointestinal and other disorders in distant organs such as kidney or liver (Teltschik et al, 2012; Cray et al, 2021). Likewise, there is agreement that such diseases might be prevented or even cured by correcting PC abnormalities. Examples include inflammatory bowel disease, ileal CD, and necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) (Barreto et al, 2022).

The PC dysfunction can be studied by quantifying the distribution and expression pattern of cytoplasmic AMPs, the morphology of the granules, and/or the number of PCs per crypt (Stappenbeck & McGovern, 2017). In this sense, genetic disorders, environmental factors, and diet are studied and linked as inducers of PC dysfunctions.

PC numbers

It has been reported that PC numbers may decline by cell death and/or extrusion in the lumen, which aggravates intestinal and inflammatory diseases (Gassler, 2017). The reduction in PC number per crypt has been described in several pathological conditions, such as intestinal ischemia (Grootjans et al, 2011), pathogenic bacterial infections (White et al, 2017), NEC (White et al, 2017), and GVHD (Levine et al, 2013). However, in other intestinal diseases, such as ileal CD, the defect is in PC function and not in PC number (Deuring et al, 2014; Strigli et al, 2021). Moreover, changes in PC numbers are not always correlated with alterations in the expression of PC‐specific AMPs (Zwarycz et al, 2019; Kip et al, 2020). Newly formed PCs after an insult could be immature and/or dysfunctional and contain fewer or aberrant granules.

Paradoxically, in some cases, like alcohol‐fed animals or Salmonella infections, induction of cell death in the small intestine is coupled with increased PC numbers (Rodriguez et al, 2012). This could be explained by the fact that during intestinal inflammation, post‐mitotic PCs respond by acquiring stem cell‐like properties, thus contributing to the tissue regenerative response during inflammation (Schmitt et al, 2018). An increase in PC number per crypt has been observed after bacterial infection with S. typhimurium (Rodriguez et al, 2012). PC metaplasia has also been described in mouse models after infection (Singh et al, 2020). In humans, PC metaplasia has been described in NEC in premature infants (Puiman et al, 2011) and in CDs and ulcerative colitis patients (Tanaka et al, 2001).

Due to the location of PCs, the study of the number and function of these cells in humans is complex and requires tissue biopsies. The use of murine models is therefore fundamental to understanding the processes of the reduction in PC number and its association with different events.

PC cell death

The ultimate fate of IECs, death, can occur by several mechanisms, either as part of normal physiology and homeostasis (cell renewal) or due to damage‐inducing events. PC death can be the result of physiological pathways defects, ER stress or autophagy, or by extrinsic cell death stimuli induced by factors such as cytokines.

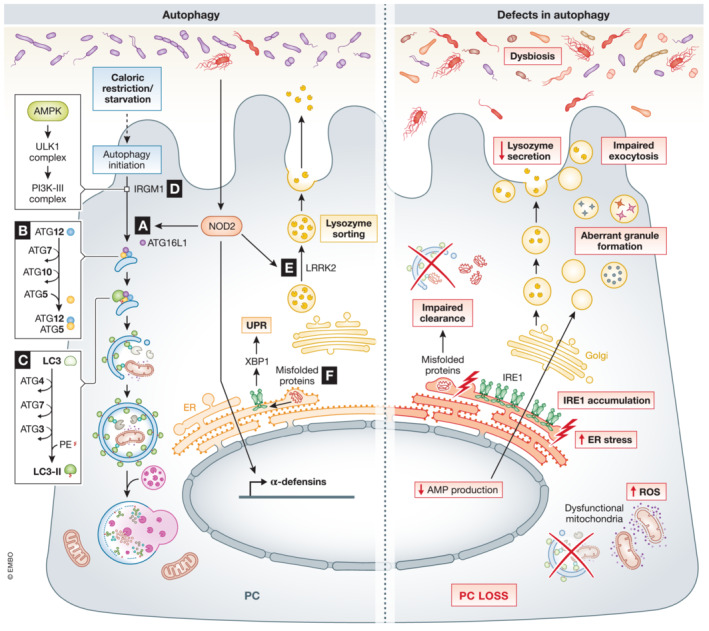

Autophagy and unfolded protein response (UPR)

In PCs, autophagy is important to manage the generation and exocytosis of the secretory granules, clearance of misfolded proteins, maintenance of mitochondrial homeostasis, alleviation of ER stress, bacterial autophagy, and survival cytokine‐mediated immunopathology after infections (Burger et al, 2018; Wang et al, 2018). Defects in autophagy or autophagy related‐genes have been linked to abnormalities in PC morphology and function (Table 3; Fig 4) (Wang et al, 2018).

Table 3.

Mouse studies linking defects in autophagy and/or unfolded protein response (UPR)‐related genes with abnormalities in PCs' morphology and function.

| Knocked‐out gene | Cell type | Mechanism | Outcome | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UPR‐related genes | X‐box‐binding protein 1 (Xbp1) | Intestinal epithelial cells |

Condensed ER ER stress Abnormal secretory granules Decreased expression of alpha‐defensins Paneth cell apoptosis |

Susceptibility to DSS‐induced colitis and bacterial infections | Kaser et al (2008) |

| Paneth cells |

Autophagy activation Abnormal secretory granules Increased cell death in crypts Unresolved ER stress UPR activation |

Transmural ileitis Development of spontaneous intestinal inflammation |

Adolph et al (2013) | ||

| Intestinal epithelial cells |

Increased total and phosphorylated IRE1α Increased NFκΒ activity Autophagosome formation Aberrant Paneth cell granules |

Ileitis dependent on microbiota | Adolph et al (2013) | ||

| Autophagy‐related genes | Atg16l1 | Intestinal epithelial cells |

Crypts with increased XBP1 splicing Reduction in Paneth cell size and number of granules Loss of homeostatic autophagy |

Susceptibility to DSS‐induced inflammation | Adolph et al (2013) |

| Intestinal epithelial cells | Accumulation of IRE1α in Paneth cells | IRE1α‐dependent spontaneous ileitis | Tschurtschenthaler et al (2017) | ||

| Intestinal epithelial cells | Paneth cell depletion | Exacerbated intestinal injury in models of graft‐versus‐host disease | Ishimoto et al (2017) | ||

| Atg16l1 HM (hypomorphic (HM) for expression of the ATG16L1 protein) | Constitutive |

Aberrant Paneth cell granules (size, morphology, and number) Irregularities in the granule exocytosis pathway Morphological abnormalities in Paneth cells Diffuse lysozyme staining |

Cadwell et al (2008) | ||

|

Atg16l1 T300A (Thr300 ➔ Ala300) |

Constitutive | Abnormal Paneth cell lysozyme distribution and decreased antibacterial autophagy after infection | Bel et al (2017) | ||

| Atg16l1/Xbp1 | Intestinal epithelial cells |

Lack of UPR‐induced autophagy Increased total and phosphorylated IRE1α Increased NFκB activity Aberrant Paneth cell granules |

Development of severe spontaneous ileitis Transmural inflammation |

Adolph et al (2013) | |

| Intestinal epithelial cells |

Impaired clearance of IrE1α aggregates ER stress Impaired Paneth cell antimicrobial function |

Aggravated DSS‐induced colitis | Tschurtschenthaler et al (2017) | ||

| Atg5 | Paneth cells |

Abnormalities in number and size of Paneth cell granules Reduced expression of AMPs |

Paneth cell loss upon T. gondii infection Increased permeability due to impaired intestinal barrier function |

Burger et al (2018) | |

| Intestinal epithelial cells |

Reduced expression of AMPs Impaired autophagy in Paneth cells |

Susceptibility to T. gondii‐mediated intestinal damage Paneth cell loss upon T. gondii infection |

Burger et al (2018) | ||

| Intestinal epithelial cells |

Morphological abnormalities in Paneth cells Irregularities in the granule exocytosis pathway Aberrant Paneth cell granules (size, morphology, and number) |

Cadwell et al (2008), Cadwell et al (2009) | |||

| Atg7 | Intestinal epithelial cells |

Deficient Paneth cell‐granule formation Alterations in lysozyme storage and secretion |

Wittkopf et al (2012) | ||

| Intestinal epithelial cells |

Morphological abnormalities in Paneth cells Aberrant Paneth cell granules (size, morphology, and number) Diffuse lysozyme staining |

Cadwell et al (2009) | |||

| Atg7/Xbp1 | Intestinal epithelial cells |

Absent UPR‐induced autophagy Aberrant Paneth cell granules |

Spontaneous ileitis Transmural inflammation Age‐dependent enteritis |

Adolph et al (2013) | |

| Atg4b | Constitutive KO |

Abnormalities in size, morphology, and number of Paneth cell granules Autophagy impairment |

Increased susceptibility to DSS‐induced colitis | Cabrera et al (2013) | |

| Leucine‐rich kinase 2 (Lrrk2) | Constitutive KO | Defects in lysozyme sorting | Increased susceptibility to intestinal Listeria monocytogenes infections | Zhang et al (2015) | |

| Immunity‐related GTPase M (Irgm1) | Constitutive KO |

Alterations in Paneth cell numbers and location |

Susceptibility to dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)‐induced intestinal injury | Rogala et al (2018) | |

| Constitutive KO |

Decreased transcript levels of specific AMPs (Lyz and Defa20) Alterations in Paneth cell numbers and location Aberrant Paneth cell‐granules (size and morphology) Abnormal Paneth cell morphology Impaired mitophagy and autophagy |

Spontaneous intestinal inflammation Ileal injury |

Liu et al (2013) | ||

| Transcription factor EB (Tfeb) | Intestinal epithelial cells | Abnormal morphology of Paneth cell granules | Magnified colitis response upon DSS | Murano et al (2017) |

Figure 4. Role of autophagy and ER in PCs.

(A) Bacterial activation of NOD2 initiates direct autophagy by recruiting ATG16l1. Defects in Nod2 and/or Atg16l1 have been related to a decrease in AMP production, impaired exocytosis, accumulation of IRE1, and bacterial translocation. (B) In PCs, ATG5 binds ATG16L1 and ATG12, which is important in the early stages of autophagy, catalyzing the microtubule‐associated protein light chain 3 (LC3) lipidation. Specific deletion of Atg5 in PCs has been associated with accumulation of ROS and increased ER stress due to impaired clearance of dysfunctional mitochondria. C) ATG4 and ATG7 form a complex with ATG3, responsible for the biogenesis of the autophagosome by determining the site of LC3 lipidation. Dysfunction in autophagy, aberrant granule formation, and defects in AMP production and secretion have been observed in Atg4b KO and Atg7 ΔIEC mice. D) IRGM1 plays a direct role in organizing the autophagy process. IRGM1 can initiate the phosphorylation cascade that activates Unc‐51 like autophagy activating kinase 1 (ULK1) and Beclin1 (an autophagy regulator part of the PI3K‐III complex), which promotes autophagy. Defects in Irgm1 have been linked to alterations in PC numbers and location, abnormal PC morphology and aberrant granules. E) LRRK2, together with RIP2 and RAB2A, coordinates lysozyme sorting after recruitment by bacterial‐activated NOD2. Dysfunctions in Nod2 and/or Lrrk2 result in compromised lysozyme secretion. F) Misfolded or unfolded proteins are recognized by IRE1, which by unconventional splicing generates XBP1, activating UPR response. Specific deletion of Xbp1 in PCs leads to PC dysfunction, a condensed ER and abnormal secretory granules. Black arrows – pathways that are active in PCs, red arrows – “up‐ or downregulation” of factors that negatively affect PCs function.

An important gene involved in autophagy is the autophagy‐related 16 like 1 gene (Atg16l1 in mice, ATG16L1 in humans). The importance of Atg16l1 is mainly in its participation in the formation of autophagosomes, but its function has been linked with other major cell activities. A study on PC‐rich organoids isolated from WT and Atg16l1‐deficient mice showed significant differences in their proteomic signature. In KO cells, 16 important functional processes were altered, the most remarkable being inhibition of the exocytosis pathway (Jones et al, 2019). According to one study, mice with Atg16l1 and Atg5‐deficient‐PCs presented irregularities in the granule exocytosis pathway, which is observed in CD patients with the homozygous ATG16L1 risk allele (Atg16l1 T300A ) (Cadwell et al, 2008). KI mice with Atg16l1 T300A have a similar phenotype, with abnormalities in PC granules, function, and PC numbers (Lassen et al, 2014). In mice, villin or PC‐specific deletion of Atg16l1, Atg5 or Atg7, or constitutive deletion of Atg4b or immunity‐related GTPase family M member (Irgm1) result in impaired exocytosis, accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria, accumulation of inositol‐requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1) and decrease in AMP production (Fig 4A–D). Likewise, mutations of Lrrk2 led to degradation of LYZ via autophagy (Fig 4E). PC‐specific deletion of Lrrk2 has also been linked with the abnormal PC‐phenotype seen in Japanese CD patients (Liu et al, 2017b).

Paneth cells, due to their intense secretions, are very sensitive to ER stress, making autophagy and the UPR important in preventing PC death. The heavy load on the ER network in PCs makes them more prone to ER stress than other cells. Disruption of PC secretions or defects in UPR‐related genes might lead to dysbiosis and inflammatory diseases (Bel et al, 2017; Wang et al, 2018). Deletion of the transcription factor X‐box‐binding protein 1 (Xbp1) specifically in PCs leads to unresolved ER stress, autophagy activation, and PC apoptosis (Table 3; Fig 4F) (Kaser et al, 2008; Adolph et al, 2013). Induction of PC‐specific ER stress has also been observed in SAMP1/YitFc mice, which are a model of CD (Shimizu et al, 2020). The disruption of ER homeostasis in those mice leads to α‐defensin misfolding associated with absence of disulfide bridges, and dysbiosis linked to progression of ileitis. The absence of disulfide bridges in HD5 (leading to reduced rather than oxidized HD5) was observed in PCs of CD patients (Tanabe et al, 2007). Also in CD patients, an increased abundance of enteroinvasive Escherichia coli and other signs of dysbiosis were associated with ER stress in PCs (Deuring et al, 2014).

Cell death by ligands: IFNs

Interferons have been postulated as critical modulators of PC function and survival (Araujo et al, 2021). A recurrent observation is that IFNs induce PC cell death. IFNs I, II, and III have been linked to PC death and/or degranulation (Günther et al, 2019; Araujo et al, 2021). Why PCs are so IFN‐sensitive and the mechanisms of their loss are unknown. However, we will explain that the effects of IFN on PCs are not necessarily direct and that indirect effects are contemplated.

Type I‐IFNs (mainly IFNα and IFNβ) are involved in antimicrobial host defense due to their antiviral and antiproliferative activities. They are considered as essential in the first line of defense against viruses (Liu et al, 2012) and bacteria and are triggered by stimulation of TLRs (Decker et al, 2005) and other pathogen sensors. In PCs, TLR9 signaling might be responsible for the bacterially triggered type‐I IFN production (Fig 5A). Through the IFN I receptor (a heterodimer consisting of IFNAR1 and IFNAR2), type I IFNs can activate several Janus kinases (JAKs), several signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT), and MAPK signaling pathways (González‐Navajas et al, 2012). Although PCs constitutively express Ifna1 (encoding IFNα1) under homeostatic conditions, little is known about its biological effect. Feeding mice with the IFN‐inducing compound, R11567DA, induced IFNα in ileum, colon, and blood, but in situ hybridization (ISH) experiments showed that IFN‐dependent genes were only induced in crypts, likely in PCs (Ifit1, Irf7, and Oas1g genes). Perhaps PCs are unique in expressing Ifnar1, or the signal transduction to IFNs in PCs is much more pronounced because of the lack of inhibitors (Munakata et al, 2008). In another study, expansion in PC numbers in mice lacking the IFNAR1 in the gut (Ifnar1 ΔIEC) was observed, meaning that IFNα can regulate PC numbers (Tschurtschenthaler et al, 2014). Finally, IFNα injection in Wistar rats was shown to cause PC degranulation and α‐defensin release (Ozcan et al, 1996).

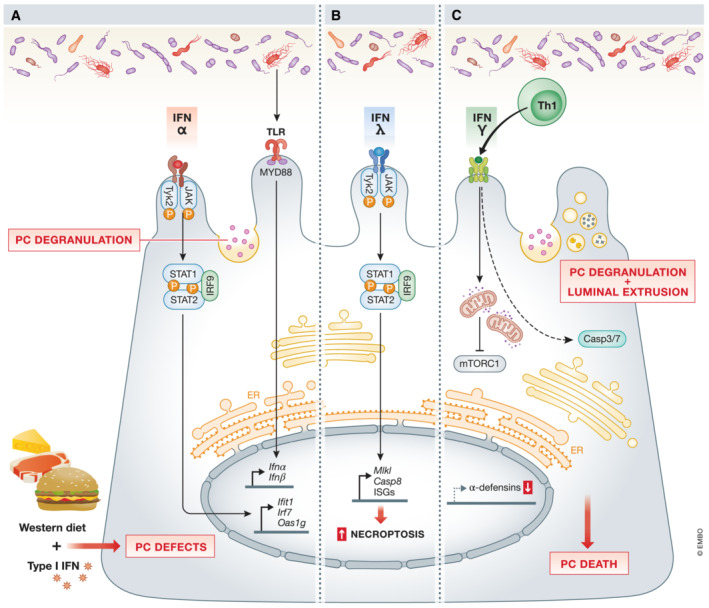

Figure 5. Role of the three types of IFNs in PCs.

(A) IFNα regulates PC‐numbers via JAK/STAT signaling. The release of type I IFN can also be triggered by bacterial‐TLR activation. The combination of Western diet and type I IFN, produced by myeloid cells, negatively affects PCs (see Figure 6 for more details). (B) Detrimental effects have been ascribed to type III IFNs, as IFNλ promotes PC necroptosis in an MLKL/CASP8‐dependent manner. (C) Schematic representation of the mechanisms related to PC‐loss associated with type II IFN (IFNγ). IFNγ mediates PC loss by an mTORC1‐dependent mechanism after disrupting mitochondrial integrity and function. Moreover, after injury, activated Th‐produced IFNγ induces PC depletion via a caspase3&7‐dependent cell death. Black arrows – pathways that are active in PCs, red arrows – “up‐ or downregulation” of factors that negatively affect PCs function.

The type III IFN group, consisting of four IFNs generally termed IFNλ, is mainly sensed by epithelial cells. Günther et al (2019) reported that in the gut epithelium, IFNλ causes the expression of mixed lineage kinase domain like pseudokinase (Mlkl) and Stat1, which leads to increased necroptosis in PCs, controlled by caspase8 (CASP8) (Fig 5B) (Günther et al, 2019). This increased PC death has been seen in CD patients, in whom also higher levels of IFNλ were observed in serum and inflamed ileal tissue (Stolzer et al, 2021).

Recent findings show that of all IFNs, type II IFN (IFNγ) is the most harmful: by promoting PC loss, it is involved in intestinal inflammation (Fig 5C) (Raetz et al, 2013; Farin et al, 2014; Eriguchi et al, 2018). In vitro and in vivo studies have shown that IFNγ hampers the expression of α‐defensins, increases degranulation, and leads to PC death (Bevins & Salzman, 2011; Raetz et al, 2013; Farin et al, 2014; Burger et al, 2018; Eriguchi et al, 2018; Araujo et al, 2021). In serum samples and ileal biopsies of IBD mouse models, increased IFNγ concentrations are concomitant with a higher rate of PC loss (Wang et al, 2018). Moreover, ileal samples from T. gondii‐infected mice had significantly fewer PCs. This occurred entirely though events in the submucosa, namely, dendritic cell activation (Th1 activation) via IL12. IFNγ production by these Th cells ultimately led to PC death (Pêgo et al, 2019), a phenotype that was reverted in mice with an epithelial or PC‐restricted IFNγRII KO (Araujo et al, 2021). Though it seems clear that IFNγ leads to PC death, the mechanisms remain uncertain, particularly whether this loss in PCs is a direct or indirect effect of IFNγ. Experiments on a GVHD mouse model have shown that alterations in the crypt cell niche, and consequently in PCs, were due to effects of IFNγ on ISCs (Takashima et al, 2019). Yokoi et al (2021) showed that both PCs and ISCs express IFNγRI, and that IFNγ caused cell death directly in both cells types. The same was proposed by Eriguchi et al (2018), who observed that IFNγ selectively induced PC death, which might impact the whole intestinal crypt (Eriguchi et al, 2018). While some authors proposed that IFNγ is sufficient to mediate PC loss (Farin et al, 2014; Eriguchi et al, 2018), others reported that both the microbiota and the basal microbiota‐induced IFNγ are needed to cause intestinal pathologies and sustained PC death in Atg5‐deficient mice (Burger et al, 2018). Recent findings have supported the idea that PCs can undergo different mechanisms of death when exposed to IFNγ. The study carried out by Farin et al (2014) confirmed that IFNγ‐induced PC death was caspase3 and 7‐dependent (Farin et al, 2014; Eriguchi et al, 2018). However, others stated that PC death was induced by the inhibition of mTORC1 by IFNγ (Araujo et al, 2021). Further investigations have confirmed that the decreased levels in mTORC1 resulted from impaired mitochondrial function as an indirect response to IFNγ (Araujo et al, 2021). Although autophagy can alleviate the effects of mitochondrial accumulation, it seems insufficient to rescue the loss of PCs, probably due to excessive autophagy or the prolonged inhibition of mTORC1. Thus, IFNγ‐stimulated effects might be exacerbated when autophagy defects exist (Ishimoto et al, 2017).

We speculate that IFNs might be so cytotoxic to PCs because PCs are direct neighbors of ISCs. As PCs sustain the continuous renewal of the intestinal layer, one of their main functions could be the protection of ISCs. They may be programmed to (1) be extremely attractive to viral infection and titrate viruses away from the ISCs, and (2) die and thereby release antimicrobial peptides/proteins to control potential bacterial superinfections of the crypts. In this view, we argue that the loss of PCs associated with potential local dysbiosis may be less damaging than the loss of ISCs.

Cell death by ligands: TNF

TNF also plays an important role in autoimmune and inflammatory disorders (Puimège et al, 2014; Van Looveren & Libert, 2018). In vivo studies have shown that TNF injection can lead to systemic inflammation characterized by the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and can induce cell death. Interestingly, in the small intestine, TNF induces apoptosis by binding exclusively to TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1) (Van Hauwermeiren et al, 2015; Ballegeer et al, 2018; Van Looveren et al, 2020). TNF can bind two distinct receptors, namely TNFR1, which mediates most TNF effects, and TNFR2. After TNF is recognized by TNFR1, it can activate proinflammatory and pro‐survival NF‐κB pathways or induce cell death by Fas‐associated death domain (FADD)‐CASP8‐dependent apoptosis or RIPK3‐MLKL‐mediated necroptosis (Pasparakis & Vandenabeele, 2015). The study conducted by Van Hauwermeiren et al (2015) showed that TNF injection in mice induced PC dysfunction characterized by an increase of ER stress, with disturbed and dilated morphology. Moreover, PCs had fewer granules, lost cellular integrity, and became dysfunctional, which may lead to an increase in bacterial translocation induced by TNF (Van Hauwermeiren et al, 2015).

Over recent years, different KO mouse models of genes involved in the TNF‐induced pathways have been generated to study their role and the PC status. Specific ablation of NF‐κB essential modulator (NEMO) in intestinal cells caused PC apoptosis and impairments in AMP expression (Vlantis et al, 2016). Interestingly, the effects of NEMOΔIEC‐mediated PC loss were independent of microbiota, as it was also seen in GF mice, but the lack of bacterial translocation ameliorates the phenotype. In IEC‐specific KO of NF‐κB subunit RelA, the absence of Ripk1 protected mice from PC death (Vlantis et al, 2016). Also, intestinal and myeloid deletion of A20 (TNFAIP3, encoded by Tnfaip3 in mice, Tnfaip3 ΔIEC/Δmyel), an inhibitor of NF‐κB and apoptosis, induces ileitis and severe colitis characterized by IEC apoptosis, goblet cell, and PC loss. The specific deletion of Tnfaip3 only in epithelial cells (Tnfaip3 ΔIEC) does not have a pathological phenotype but sensitize these mice to DSS‐induced colitis and TNF‐induced apoptosis: 24 h after injection of a sublethal TNF dose, LYZ‐containing PCs and expression of PC‐specific AMPs were reduced (Vereecke et al, 2014). Those experiments were confirmed in Tnfaip3‐deficient organoids which were more affected than WT organoids by TNF combined with IFNγ (Vereecke et al, 2014). In contrast, complete ablation of Nf‐κb in intestinal cells causes less severe PC loss, as observed in NEMOΔIEC mice, suggesting that pathways besides NF‐κB are involved in prevention of PC death (Vlantis et al, 2016).

In CASP8ΔIEC mice and FADDΔIEC mice, cell death in the intestinal crypts increased spontaneously, especially in PCs (Welz et al, 2011; Günther et al, 2012). FADD is one of the main regulators of CASP8‐mediated inflammatory responses. RIPK1 and RIPK3 have found to be crucial in PC death, as deletion of these regulators lead to protection in FADDΔIEC mice (Welz et al, 2011; Schwarzer et al, 2020). Particularly in CASP8ΔIEC mice but also in FADDΔIEC mice, inhibition of RIPK1 kinase was as protective as the combined deficiency of TNFR1 and Z‐DNA‐binding protein 1 (ZBP1), indicating that the role of RIPK1 is downstream of TNFR1 and ZBP1 activation (Schwarzer et al, 2020). The study by Schwarzer et al (2020) identified a key role of ZBP1, which appears to have similar functions as TNFR1 in the ileum. Therefore, only the double mutant can partially rescue PC loss and ileitis in FADDΔIEC mice. Günther et al (2012) identified a role for CASP8 in protecting IECs from TNF‐induced RIPK3‐mediated necroptosis. Increased PC death was observed in the ileum of CD patients, and ex vivo treatment with TNF on human control biopsies reduced Lyz in PCs, which can be rescued by an inhibitor of necroptosis. Moreover, in PCs, RIPK3 is present specifically in terminal ileum samples of human patients, but not in other intestinal cell types. These results indicate that high levels of exogenous TNF in the lamina propria, as in CD patients, can induce PC necroptosis and deficient expression of antimicrobial peptides, which may add to disease progression (Günther et al, 2012).

So, deficiencies in genes related to apoptosis sensitize PCs to TNF. Loss of X‐linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) was recently reported to sensitize to TNF‐ and microbiota‐dependent intestinal inflammation (Strigli et al, 2021; Wahida et al, 2021). Deficiency in XIAP has been linked to NF‐κB impairment, alteration in the direct binding and inhibition of caspases, and altered recognition of bacteria, the last due to the critical role of XIAP in the NOD1 and NOD2 complex (Strigli et al, 2021). Exacerbation and development of intestinal inflammation in this mouse model were specifically due to the negative effects in PCs. Impaired expression of α‐defensins‐PC, aberrant granules, and reduced PCs numbers were observed in the ileum of Xiap KO mice and Xiap ΔRING mice (lacking the C‐terminal RING domain of XIAP). Further crosses with TNFR1KO and RIPK3KO mice prevented PC loss in Xiap KO mice, demonstrating that ablation of XIAP promotes TNF‐ and RIPK1/3‐dependent PC death (Strigli et al, 2021). Variants in Ripk1 and Casp8 are observed in patients with severe immune deficiencies and IBD (Wahida et al, 2021).

Mice with a deletion in the TNF AU‐rich elements (TNFΔARE) suffer from CD‐like ileal inflammation due to loss of translational control of TNF linked to PC dysfunction. This dysfunction was characterized by decreased expression of Lyz1 and Defa5, abnormal PC granularity and reduction in PC numbers. Confirming the phenotype, TEM analysis showed that remaining PCs have aberrant secretory granules, enlarged rough ER, and degenerative mitochondria, the latter being key in the CD‐associated loss of stemness (Khaloian et al, 2020).

These findings indicate that deletion of specific genes involved in autophagy, MAPK and NF‐κB signaling, and apoptosis, might lead to defective PCs, increase susceptibility to infection and/or IFN‐/TNF insults, or even to cell death, in some cases specifically in PCs.

PCs in disease

Paneth cell (PC) dysfunction or reduced numbers per crypt have been observed in several inflammatory, infectious, or rejection diseases. CD‐associated E. coli is able to penetrate deep in the intestinal crypts, but the link between reduced numbers of PCs, PC function, or increased resistance of the bacteria to α‐defensins is not yet clear. Enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) infection led to ileal inflammation and fewer PC markers (Ren et al, 2014). Mortality of ETEC‐infected mice was about 30% after 24 h, and PC markers (measured by qPCR) were reduced in the ileum (Liu et al, 2017a). In a mouse model of S. typhimurium infection, PC death was associated with bacterial translocation to the spleen. The PC death was inhibited by treatment with Lactiplantibacillus plantarum. This effect of Lpb. plantarum might have been due to inhibition of pathogen colonization by competitive exclusion or mediated by TLR4/NF‐κB activation (Ren et al, 2022).

Recent studies have shown that abnormal PC morphology and/or decreases in α‐defensins are present in 50% of pediatric CD patients (Perminow et al, 2010; Liu et al, 2018). As dysfunction in autophagy‐related genes trigger PC dysfunctions, it is not surprising that autophagy defects have been correlated with PC aberrations in CD patients (Table 3). Investigators recently reported that abnormalities in PCs increase the risk of ileitis and CD, and consider PCs as central players in the ileal chronic inflammation in CD patients (Wehkamp & Stange, 2020; Cray et al, 2021). Some genes (e.g., Nod2, Atg16l1, Atg5, Xbp1, and Lrrk2) described in Table 3, are identified as risk factors for CD. Moreover, ileal CD patients carrying mutations in some of these genes (e.g., Atg16l1, Nod2, and Lrrk2) have reduced expression of α‐defensins or PC abnormalities. These results support the idea that PC functional problems are the initiators of ileal CD in patients. Moreover, in some cases those effects might be aggravated by non‐specific consequences of an environmental trigger (e.g., diet, antibiotics, and tobacco) (Wehkamp et al, 2007; Stappenbeck & McGovern, 2017). Yet, it is still debated if, and if so, how PC dysfunction can affect inflammation in the colon. A possible explanation is that in healthy conditions, functional α‐defensins from the ileum are found in the colon in an active form, where they can exert an effect (Mastroianni & Ouellette, 2009). Moreover, metaplastic PCs in the colon in IBD are considered as a repair mechanism and a useful marker of the disease (Tanaka et al, 2001).

Paneth cells have also been identified as sensors of viral infection. A study in male rhesus macaques infected with simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) showed a correlation between epithelial damage and induction of IL‐1b expression by PCs preceding the antiviral interferon host response (Hirao et al, 2014). That study reported changes in the microbial composition of the macaques (after the infection) that may promote opportunistic enteric bacterial infections (Zaragoza et al, 2011). Moreover, a recent study with transmissible viral gastroenteritis highlighted the negative impact of PC loss, caused by the infection, and the inhibition of Notch factors secretion on ISC self‐renewal and differentiation (Wu et al, 2020).

In human obese patients, a shift in the microbiome, activation of the UPR in the gut, and reduced HD5 and LYZ in PCs were observed (Hodin et al, 2011b). Moreover, PC numbers were reduced in a human model for ischemia/reperfusion (Grootjans et al, 2011). In mice, clear relations between pathology, reduced PC number, and dysbiosis have been found in a model of GVHD. The rejection of tissue in the mouse model led to changes in microbiota composition. In GVHD, a convincing role of PCs in the pathology has been demonstrated, because PC numbers were greatly reduced in GVHD mice, declining from five to six PCs per crypt to just one PC per crypt. Then, E. coli colonization in the gut increased, followed by tissue invasion and death. The data demonstrated, indirectly, the critical role of PCs in controlling the pathological impact of graft‐initiated inflammation and immune reactions (Ara & Hashimoto, 2021). Cytokines such as IL22 or proteins like R‐spondin‐1 showed success in preventing dysbiosis and improving PC status in in vivo models of GVHD (Takashima et al, 2011; Hanash et al, 2013; Hayase et al, 2017).

Other cytokines

Takahashi et al (2008) were among the first to report that PCs can produce IL17 under certain inflammatory conditions, like TNF challenge. IL17 production was shown to be PC‐specific in the gut (Takahashi et al, 2008). This increase in TNFα‐induced IL17 drives further the intestinal inflammation and is responsible for the damage observed in the small intestine (Takahashi et al, 2008). Others showed in mice that alcohol led to ER stress‐mediated IL17 production in PCs, which increased apoptosis and permeability, leading to bacterial translocation. Normality was restored by antibody blockage of IL17A (Gyongyosi et al, 2019). Moreover, the effects of PC‐induced IL17A have been linked to multiorgan dysfunction (Takahashi et al, 2008; Park et al, 2011, 2012). Remarkably, PCs, and not Th17 cells, have been described as the main source of IL17A, and this was also shown by the decrease of IL17A after PC ablation (Park et al, 2011; Gyongyosi et al, 2019). On the contrary, the use of IL17A inhibitors in CD and ulcerative colitis patients increased the adverse effects (Hueber et al, 2012). Since IL17 receptors are ubiquitously expressed, IL17 produced by PCs could be considered as a locally produced product that has systemic amplifying activities and might be considered as a therapeutic target in systemic diseases.

The roles of other cytokines, such as IL22, in PC maturation and function were recently studied (Mühl & Bachmann, 2019; Gaudino et al, 2021; Chiang et al, 2022). Early observations showed that loss of IL22 in the PCs of mice significantly compromises AMP production. A recent study published in Nature highlighted the crucial STAT3‐dependent role of IL22 in crypt regeneration and PC maturation, and pointed to the activation in PCs of IL22–STAT3 signaling response after adherent‐invasive E. coli infection (Chiang et al, 2022). These findings have been confirmed in organoids: production and secretion of LYZ, as well as other PCs markers, increased after IL22 supplementation (Zwarycz et al, 2019; Gaudino et al, 2021). In addition, IL22 alleviates high‐fat diet effects by improving the status of PCs and increasing the production of AMP (Gaudino et al, 2021). Moreover, IL22 reverted the decrease of Reg3γ in PCs in a mouse model of GVHD (Zhao et al, 2018). However, studies on organoids have shown that persistent IL22 signaling can negatively impact PCs by increasing ERS, leading to a decrease in the numbers of ISCs and PCs (Zhao et al, 2018). Downstream of IL22–STAT3 activation is an IL18–IFNγ cascade, which might contribute to host defense against infections such as by adherent‐invasive E. coli. Cooperation between IL22 and IL18 in a coordinated inflammatory response has been previously described in other cell types (Mühl & Bachmann, 2019). While IL22 seems to activate the cascade in response to an infection, IL18 is indispensable for the PC response and homeostasis. IL18KO mice displayed fewer LYZ‐containing PCs and appeared to be more sensitive to bacterial infections. Moreover, organoids increased their AMP production when stimulated with IL18 (Chiang et al, 2022). However, there is no agreement about the role and the expression of Il22r and Il18r in PCs. Gaudino et al (2021) showed that PC maturation and functions depend on cell‐intrinsic IL22Ra1 signaling, and this PC‐specific IL22Ra1 signaling provide immunity against S. typhimurium (Gaudino et al, 2021). However, Chiang et al (2022) showed that the expression of Il22r is specific to Lgr5+ ISCs, and that the expression of Il18r is clearly higher in PCs (Chiang et al, 2022). Due to the participation of IL18 and IL22 receptors in PC antimicrobial response and homeostasis, it is important to unravel their expression profiles and mechanisms of activation.

PCs and aging

Epithelial homeostasis also depends on the balance of the ISC response between self‐renewal and differentiation. The correct management of this continuous cell renewal is crucial for the intestinal epithelium's functions in absorption of nutrients and hormone secretion, while discriminating between commensal and pathogenic microbes.

In the small intestine, a decline in mucosal renewal during aging might lead to a defective immune system and an increased susceptibility to infections (Pentinmikko & Katajisto, 2020). Several authors have reported that the regenerative potential of human and mouse intestinal epithelium decreases with age due to defects in ISCs and in their niche (Nalapareddy et al, 2017). As stem‐cell‐niche supporters, PCs play a key role in tissue regeneration, regulating the number and function of ISCs by secreting niche‐signaling factors, and their metabolism by producing lactate (Sato et al, 2011a; Rodríguez‐Colman et al, 2017). Several studies have reported that during aging, the size and cellular composition of the crypts changes (Pentinmikko & Katajisto, 2020; Nalapareddy et al, 2022). Notably, the number of PCs increases in aged mice and humans, but conflicting results were reported on Lgr5+ cell numbers (Moorefield et al, 2017; Nalapareddy et al, 2017; Mihaylova et al, 2018; Pentinmikko & Katajisto, 2020). In vitro studies on aged ISCs cells and crypts from aged humans and mice have shown impaired regeneration. The impairment and reduction of the regeneration activity of ISCs in aging might be due to an increased expression in Atoh1, and a decrease of both Olfm4 and Notch1 compared with young ISCs (Nalapareddy et al, 2022).

Experiments on organoid cultures were used to establish the role of young and old PCs in the maintenance of the niche homeostasis (Nalapareddy et al, 2017; Pentinmikko et al, 2019). Generation of organoids from isolated ISCs and PCs have shown that the signals specifically from aged PCs compromised the niche function, probably due to reduced canonical Wnt signaling, that might be related with PC dysfunction (Pentinmikko et al, 2019). However, little is known about the overall function and morphology of old PCs. Differences in gene expression has been reported between old and young PCs, such as the reduced expression of Wnt3a (Nalapareddy et al, 2017). Indeed, in vitro supplementation with Wnt3a to aged human and murine organoids improved regeneration of old epithelia (Nalapareddy et al, 2017). This functional decline in stemness‐maintaining Wnt signaling may be due to the production of Notum, a negative extracellular Wnt regulator produced only in aged PCs (Yilmaz et al, 2012). One of the main reasons for this increase in Notum activity might be the activation of mTORC1. Mechanistically, high activity of mTORC1 in aged PCs inhibits the activity of peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor α (PPARα), which ultimately leads to an increase in the expression of Notum (Pentinmikko et al, 2019). The importance of Notum was confirmed in vitro and in vivo by using ABC99, an inhibitor of Notum, which restored the Wnt‐mediated PC and ISC functions, leading to increased regeneration activity in old crypts comparable to those from young mice (Pentinmikko et al, 2019). However, little is known about the functional effect of the bias towards the production of more PCs on the intestinal crypts and the influence on tissue regeneration (Nalapareddy et al, 2022). Why do aged intestines need more PCs? And what is their function in aged subjects?

Another explanation for alteration in PC numbers during aging might also be the lowered Zn availability. Several studies have shown that aging in people is associated with a decrease in blood Zn levels (Meunier et al, 2005). This may be partly due to changes in dietary choices and feeding behavior but could also be a reflection of reduced uptake of Zn from the food and/or the availability of the intracellular ionic Zn (Mocchegiani et al, 2011). As PCs are believed to be the main cells responsible for heavy metal uptake, an imbalance in PC status during aging may be a possibility. Moreover, changes in gut microbiota have been observed upon aging (Claesson et al, 2011). The changes in microbiota composition might affect PCs, or the increase in PCs upon aging might be related to the changes in the microbiota. Alternatively, the intestine might be trying to keep the niche homeostasis by producing more PCs, which could lead to increased secretion of AMPs.

Fasting and diet

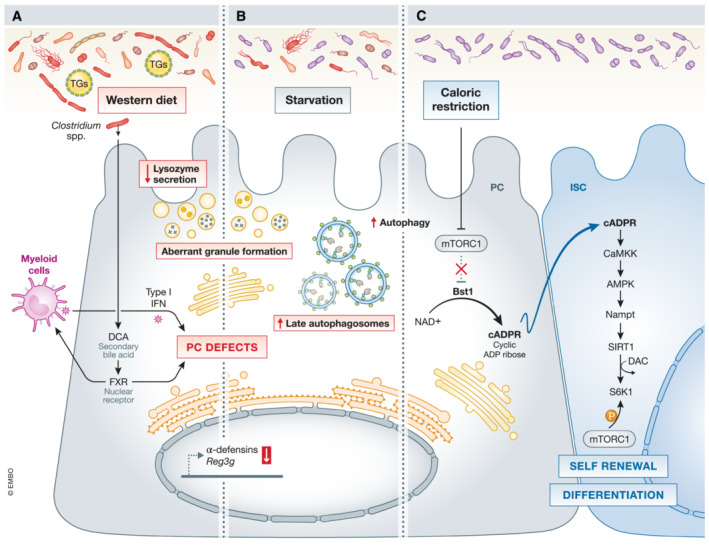

Environmental factors such as diet can also trigger PC dysfunction or increase PC activity. In recent years, multiple studies have covered the crosstalk between diet, commensals, ingested bacteria and their byproducts, and their effect on the immune system. Diet can affect the function and number of PCs either directly or indirectly through the microbiota. The impact of diet (high‐fat diet, Western diet, Zn deficiency, alcohol consumption, or others) or starvation on the status of PCs is summarized in Table 4 and Fig 6A–C.

Table 4.

The impact of diet on PCs and gastrointestinal function.

| Diet | Effect on Paneth cells | Outcome of the diet | Factors reinforcing the effect of the diet on Paneth cells | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol |

Reduced expression of antimicrobial peptides (α‐defensins) Decreased density and size of Paneth cell granules |

Increased bacterial translocation towards the liver Reduced antimicrobial activity of crypts Dysbiosis Outcome reversed by synthetic HD5 Treatment |

MMP7 KO mice (α‐defensin‐deficient mice) Zinc deficiency |

Purohit et al (2008), Zhong et al (2020) |

| Western diet | Paneth cell dysfunction |

Reduced intestinal barrier function Dysbiosis |

Liu et al (2021) | |

| High‐fat diet |

Reduced expression of antimicrobial peptides (α‐defensins and RegIIIγ) Increased Paneth cell death |

Impaired intestinal barrier function Dysbiosis |

Vitamin D receptor KO mice | Su et al (2016), Guo et al (2017), Lee et al (2017) |

| Oxidized n‐3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n3‐PUFA) | Decreased Paneth cell numbers in the duodenum compared to unoxidized n3‐PUFA | Oxidative stress and inflammation in the upper intestine | Awada et al (2012) | |

| Arginine supplementation | Increased expression and secretion of AMPs | Boost of innate immune response in the small intestine | Ren et al (2014) | |

| Ketogenic diet | Increased Paneth cell numbers and activity | Stimulates differentiation in the small intestine via 3‐hydroxy‐3‐methylglutaryl‐CoA synthase 2 (HMGCS2)/and the ketone body β‐hydroxybutyrate (βHB) | Wang et al (2017b) | |

| Caloric restriction | Decreased mTORC1 activity in Paneth cells | Paneth cell produced cyclic ADP ribose promotes self‐renewal of intestinal stem cells | Yilmaz et al (2012) | |

| Starvation |

Decreased expression and secretion of antimicrobial peptides (α‐defensins, Lysozyme and RegIIIγ) Aberrant granule formation Increased autophagy |

Increased intestinal permeability Increased bacterial translocation towards mesenteric lymph nodes |

Hodin et al (2011a) |

Figure 6. Effects of Western diet, starvation, and caloric restriction on PCs.