Abstract

Introduction

Combining lenvatinib with a programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) inhibitor has been explored for the treatment of un-resectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC). This study aimed to investigate the real-world efficacy of and prognostic factors for survival associated with lenvatinib plus PD-1 inhibitor treatment in a large cohort of Asian uHCC patients even the global LEAP-002 study failed to achieve the primary endpoints.

Methods

Patients with uHCC treated with lenvatinib and PD-1 inhibitors were included. The primary endpoints were overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS), and the secondary endpoints were the objective response rate (ORR) and adverse events (AEs). Prognostic factors for survival were also analyzed.

Results

A total of 378 uHCC patients from two medical centers in China were assessed retrospectively. The median patient age was 55 years, and 86.5% of patients were male. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection (89.9%) was the dominant etiology of uHCC. The median OS was 17.8 (95% confidence interval (CI) 14.0–21.6) months. The median PFS was 6.9 (95% CI 6.0–7.9) months. The best ORR and disease control rate (DCR) were 19.6% and 73.5%, respectively. In multivariate analysis, Child‒Pugh grade, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status score, involved organs, tumor burden score, and combination with local therapy were independent prognostic factors for OS. A total of 100% and 57.9% of patients experienced all-grade and grade 3/4 treatment-emergent AEs, respectively.

Conclusion

This real-world study of lenvatinib plus PD-1 inhibitor treatment demonstrated long survival and considerable ORRs and DCRs in uHCC patients in China. The tolerability of combination therapy was acceptable but must be monitored closely.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12072-022-10480-y.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Un-resectable, Lenvatinib, PD-1 inhibitor, Pembrolizumab, Nivolumab, Adverse events, Hepatitis B virus

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) has a high incidence and mortality. Most cases are un-resectable HCC (uHCC) [1, 2]. Patients with uHCC treated with systematic therapy exhibit a median overall survival (OS) of only 11.8–21.2 months based on both phase III studies [3–10] and real-world studies [11–14].

Recently, phase 1b studies of lenvatinib plus a PD-1 inhibitor (pembrolizumab or nivolumab) for the treatment of uHCC patients showed promising efficacy in European and American [15] and Japanese cohorts [16]. Additionally, the recent LEAP-002 study found that compared with lenvatinib, lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab did not significantly increase OS (21.2 vs. 19.0 months, HR = 0.840, p = 0.0227 > 0.0185) but did result in the longest OS in patients with uHCC [10]. In East Asia, especially China, where chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is an important etiological factor of HCC and where the disease is different from that in other countries [1, 17], the efficacy of lenvatinib plus PD-1 inhibitor combination therapy is unclear.

Many PD-1 inhibitors for patients with uHCC are approved for use in China [18–20]. However, there is a lack of studies of large Chinese uHCC cohorts to evaluate this combination therapy. Moreover, it is unclear whether such patients could achieve better survival with lenvatinib plus PD-1 inhibitor combination therapy. Therefore, we designed this study to retrospectively observe the effect of lenvatinib plus PD-1 inhibitor combination therapy in a large uHCC cohort and explore the prognostic factors for survival associated with this treatment.

Patients and methods

Study design and patients

We retrospectively collected data on consecutive patients with uHCC treated with lenvatinib plus PD-1 inhibitors from October 2017 to November 2021 at 2 tertiary care hospitals (Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH) and the Fifth Medical Center of the People's Liberation Army General Hospital (PLAGH)).

Patients were eligible for this study if they met the following criteria: patients were pathologically confirmed or confirmed by imaging to have HCC [21–23]; patients exhibited at least one measurable lesion per the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1 guidelines; patients exhibited uHCC, i.e., were not eligible for curative treatment; patients were at least 18 years old; patients had a Child‒Pugh classification of A–B, and patients exhibited Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) scores of 0–2. The exclusion criteria included the presence of end-stage HCC; history of organ transplant; prior lenvatinib or PD-1 inhibitor treatment; and discontinued use of combination therapy after less than 2 cycles of treatment. We performed a simple comparison with our real-world cohorts and similar randomized controlled LEAP-002 study to show the similarity and difference in baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes, which may also highlight some important clinical prognostic factors for survival.

This study is registered as NCT03892577.

Treatment

Patients were treated with the de novo combination of lenvatinib and a PD-1 inhibitor. The dose of lenvatinib was dependent on patient weight (> = 60 kg: 12 mg; < 60 kg: 8 mg). For PD-1 inhibitors, pembrolizumab or nivolumab, and camrelizumab, sintilimab, toripalimab, or tislelizumab were allowed, and 200 mg (toripalimab: 240 mg), every three weeks, was administered intravenously. The choice of the type of PD-1 inhibitor in our study was a joint decision between physicians and patients in the real-world practice.

Endpoints and assessments

The primary endpoints were OS and progression-free survival (PFS), and the secondary endpoints were the objective response rate (ORR) and safety. OS was defined as the time elapsed from the start of combination therapy until death (all causes). Surviving patients were censored at the last follow-up date. Tumor response was evaluated by the RECIST v1.1 guidelines [24]. PFS was defined as the time elapsed from the start of combination therapy until the date of progression or death (all causes), whichever occurred first. Durable clinical benefit (DCB) was defined as complete response (CR), partial response (PR), or stable disease (SD) for ≥ 24 weeks [25], which was evaluated by professional radiologists at our centers who were blinded to the therapeutic outcomes and clinicopathological features. Grades of adverse events (AEs) were assessed by physical examination and laboratory and imaging tests performed at the time of treatment based on the National Cancer Institute’s Common Toxicity Criteria (CTCAE) version 5.0. Management of AEs was according to the related guidelines [26, 27] and the guidelines for administration of the drug.

Statistical analyses

Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan‒Meier method and compared with the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression models were used to estimate the possible risk factors influencing PFS and OS; the results are reported as hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All variables potentially associated with OS or PFS and having a univariate p value of < 0.1 were included in multivariate analyses. The results with two-tailed p values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.1.2 and Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (version 25; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Results

Patient characteristics

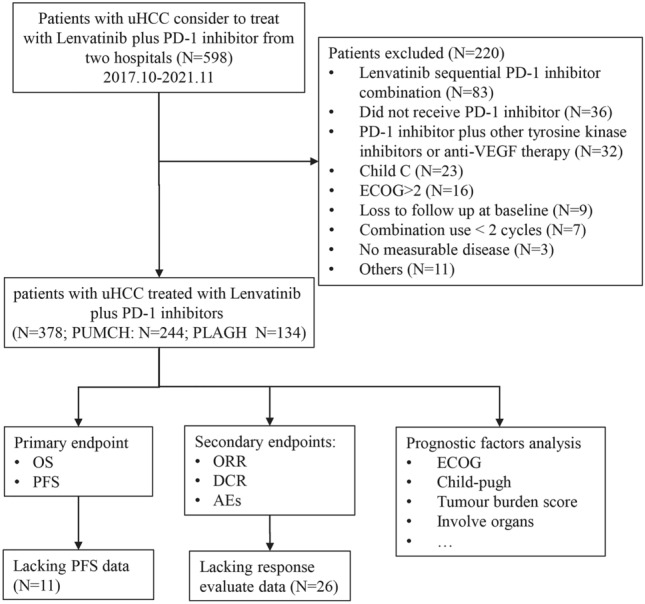

A total of 598 patients with HCC from October 2017 to November 2021 were screened from two hospitals, and 220 patients were excluded. Then, a total of 378 consecutively eligible uHCC patients who were treated with lenvatinib plus PD-1 inhibitors were evaluated (Fig. 1). Their baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the study design

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of Chinese un-resectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC) patients and LEAP-002 study receiving lenvatinib plus PD-1 inhibitors

| Present study | LEAP-002 study | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Lenvatinib plus PD-1 inhibitors (N = 378) |

Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab (N = 395) |

Lenvatinib plus placebo (N = 399) |

| Median age (range) | 55 (18–89) | 66 (19–88) | 66 (20–88) |

| Sex—no. (%) | |||

| Male | 327 (86.5) | 317 (80.3) | 327 (82.0) |

| Female | 51 (13.5) | 78 (19.7) | 72 (18.0) |

| ECOG performance status—no. (%) | |||

| 0 | 165 (43.7) | 268 (67.8) | 273 (68.4) |

| 1 | 164 (43.4) | 127 (32.2) | 126 (31.6) |

| 2 | 49 (13.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Child–Pugh Grade—no. (%) | |||

| A | 293 (77.5) | 393 (99.5) | 397 (99.5) |

| B | 85 (22.5) | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.5) |

| BCLC Stage—no. (%) | |||

| B | 48 (12.7) | 85 (21.5) | 95 (23.8) |

| C | 330 (87.3) | 310 (78.5) | 302 (75.7) |

| Etiology—no. (%) | |||

| HBV | 340 (89.9) | 192 (48.6) | 193 (48.4) |

| HCV | 11 (2.9) | 94 (23.8) | 87 (21.8) |

| HBV and HCV | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Others | 26 (6.9) | 109 (27.6) | 119 (29.8) |

| MVI—no. (%) | |||

| Yes | 198 (52.4) | 71 (18.0) | 62 (15.5) |

| No | 180 (47.6) | 324 (82.0) | 337 (84.5) |

| EHS metastasis—no. (%) | |||

| Yes | 173 (45.8) | 249 (63.0) | 243 (60.9) |

| No | 205 (54.2) | 146 (37.0) | 156 (39.1) |

| MVI or EHS—no. (%) | 297 (78.6) | 268 (67.8) | 262 (65.7) |

| AFP level—no. (%) | |||

| < 400 ng/mL | 199 (52.6) | 119 (30.1) | 132 (33.1) |

| ≥ 400 ng/mL | 179 (47.8) | 276 (69.9) | 267 (66.9) |

| No. of involved organs—no. (%) | |||

| 1 | 217 (57.4) | – | – |

| 2 | 123 (32.5) | – | – |

| ≥ 3 | 38 (10.1) | – | – |

| Tumor burden score (TBS)—no. (%) | |||

| < 8 | 199 (52.6) | – | – |

| ≥ 8 | 179 (47.4) | – | – |

| Tumor largest size—no. (%) | |||

| < 7 cm | 195 (51.6) | – | – |

| ≥ 7 cm | 183 (48.4) | – | – |

|

Number of prior systemic therapies—no. (%) |

|||

| 0 | 310 (82.0) | 395 (100.0) | 399 (100.0) |

| 1 | 60 (15.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| ≥ 2 | 8 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Combined with local therapy—no. (%) | |||

| Yes | 206 (54.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| No | 172 (45.5) | 395 (100.0) | 399 (100.0) |

AFP alpha-fetoprotein, BCLC Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer, ECOG Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, EHS extra-hepatic spread, HBV hepatitis B virus, HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, HCV chronic hepatitis C virus, MVI macrovascular invasion

The median age of the 378 patients was 55 years, and the majority (86.5%) of patients were male. The percentages of patients with ECOG-PS values of 0, 1 and 2 were 43.7%, 43.4% and 13.0%, respectively. Chronic HBV infection (89.9%) was the dominant etiology of uHCC. At baseline, 198 (52.4%) patients exhibited macrovascular invasion (MVI) by the tumor, whereas 173 (45.8%) exhibited extra-hepatic spread (EHS) of the tumor. The tumor burden score (TBS) was calculated by the maximum tumor size and number of tumors in the liver [28, 29]. Using the cutoff of 8 [28, 29], 47.4% of patients were classified as the high TBS score group. Most uHCC patients were systemic therapy-naïve (82.0%). During treatment, 54.5% of patients also received local therapy (trans-arterial chemoembolization (TACE), radiofrequency ablation (RFA) or radiation therapy (RT)) before and after two months of the combination therapy. There were many kinds of PD-1 inhibitors used for our cohort. The proportions of patients treated with pembrolizumab, nivolumab, sintilimab, camrelizumab, toripalimab, and tislelizumab were 18.3%, 5.6%, 33.9%, 27.5%, 11.6%, and 3.2%, respectively. We found that the important characteristics (ECOG, BCLC stage, etc.) were similar in lenvatinib plus different PD-1 inhibitors groups (Table S1). Only a relatively higher proportion of patients with Child‒Pugh B liver function (49/129, 38.3%) were observed in lenvatinib plus sintilimab subgroup.

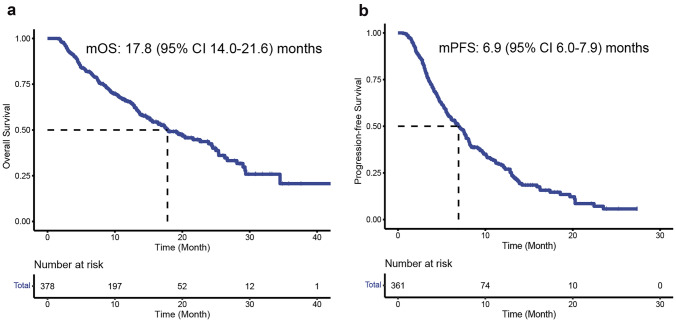

Efficacy outcomes and prognostic factors and subgroup analyses for survival

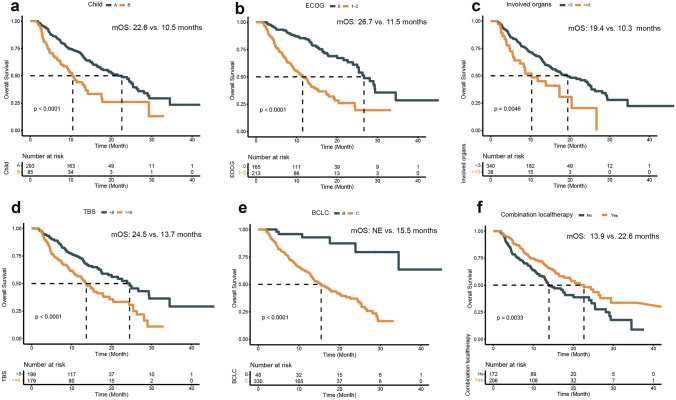

At the time of analysis, the median follow-up was 10.4 (interquartile range (IQR) 6.2–15.8) months. The median OS was 17.8 months (95% confidence intervals (CIs) 14.0–21.6) (Fig. 2A), and the 1-year and 1.5-year OS rates were 43.7% (95% CI 38.7–48.7) and 18.3% (95% CI 14.4–22.1), respectively (Table 2). Eight potential prognostic variables for OS were selected based on univariate Cox analysis, namely Child‒Pugh grade, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage, ECOG PS, a-fetoprotein (AFP) level, involved organs, TBS, MVI, and combination with local therapy (Table 3). In multivariate analysis, Child‒Pugh grade (B vs. A: HR 1.675; 95% CI 1.171–2.396, p = 0.005; 10.5 vs. 22.6 months; Fig. 3A), ECOG PS (1–2 vs. 0: HR 2.209; 95% CI 1.538–3.173, p < 0.001; 11.5 vs. 26.7 months; Fig. 3B), involved organs (< 3 vs. ≥ 3: HR 1.716; 95% CI 1.073–2.744, p = 0.024; 10.3 vs. 19.4 months; Fig. 3C), and TBS (high vs. low: HR 1.543; 95% CI 1.093–2.177, p = 0.014; 13.7 vs. 24.5 months; Fig. 3D) were independently associated with a significantly shorter OS. Conversely, BCLC stage (B vs. C: HR 0.297; 95% CI 0.115–0.767, p = 0.012; not evaluated (NE) vs. 15.5 months; Fig. 3E) and combination with local therapy (yes vs. no: HR 0.665; 95% CI 0.485–0.911, p = 0.011; 22.6 vs. 13.9 months; Fig. 3F) were associated with a significantly longer OS (Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan‒Meier estimates of overall survival (A) and progression-free survival (B)

Table 2.

Efficacy outcomes in Chinese un-resectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC) patients and LEAP-002 study receiving lenvatinib plus PD-1 inhibitors

| Parameter | Present study | LEAP-002 study | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lenvatinib plus PD-1 inhibitors (N = 378) |

Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab (N = 395) |

Lenvatinib plus placebo (N = 399) |

|

| ORR, % (95 CI) | 19.6 (15.6–23.6) | 26.1% | 17.5% |

| Best overall response | |||

| CR, no. (%) | 0 (0) | – | – |

| PR, no. (%) | 74 (19.6) | – | – |

| SD, no. (%) | 221 (58.5) | – | – |

| PD, no. (%) | 57 (15.1) | – | – |

| Unknown/not evaluable, no. (%) | 26 (6.9) | – | – |

| DCR, % (95 CI) | 78.0 (73.9–82.2) | 81.3% | 78.4% |

| DCB, % (95 CI) | 50.0 (45.0–55.0) | – | – |

| DOR, % (95 CI) | 10.8 (7.5–14.0) | 16.6 (range: 2.0 +–33.6 +) | 10.4 (range: 1.9–35.1 +) |

| Median PFS, months (95%CI) | 6.9 (6.0–7.9) | 8.2 (6.4–8.4) | 8.0 (6.3–8.2) |

| 6 months, % (95 CI) | 44.0 (38.9–49.2) | – | – |

| 12 months, % (95 CI) | 15.0 (11.3–18.6) | 34.1% | 29.3% |

| Median OS, months, months (95%CI) | 17.8 (14.0–21.6) | 21.2 (19.0–23.6) | 19.0 (17.2–21.7) |

| 6 months, % (95 CI) | 75.4 (71.1–79.7) | – | – |

| 12 months, % (95 CI) | 43.7 (38.7–48.7) | – | – |

| 18 months, % (95 CI) | 18.3 (14.4–22.1) | – | – |

| Median follow-up, month (IQR) | 10.4 (6.2–15.8) | 32.1 (range: 25.8–41.1) | |

CI confidence interval, CR complete response, DCR disease control rate, DCB durable clinical benefit, DOR duration of response, IQR interquartile range, ORR objective response rate, OS overall survival, PD progressive disease, PFS progression-free survival, PR partial response, SD stable disease

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of prognostic factors for progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS)

| Variates | Univariate analysis for PFS | Multivariate analysis | Univariate analysis for OS | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p value | p value | HR (95% CI) | p value | p value | HR (95% CI) | |

| Age (< 65 vs. ≥ 65) | 0.116 | 0.552 | ||||

| Sex (Female vs. Male) | 0.979 | 0.710 | ||||

| HBV (No vs. Yes) | 0.793 | 0.854 | ||||

| HCV (No vs. Yes) | 0.454 | 0.829 | ||||

| Child–Pugh score (B vs. A) | 0.050 | 0.565 | 1.100 (0.795–1.523) | < 0.001 | 0.005 | 1.675 (1.171–2.396) |

| BCLC stage (B vs. C) | 0.001 | 0.544 | 0.859 (0.525–1.404) | < 0.001 | 0.012 | 0.297 (0.115–0.767) |

| ECOG PS (1–2 vs. 0) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 1.832 (1.363–2.461) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 2.209 (1.538–3.173) |

| AFP level (≥ 400 vs. < 400) | 0.059 | 0.488 | 1.098 (0.843–1.431) | 0.014 | 0.474 | 1.122 (0.819–1.536) |

| Involve organs (≥ 3 vs. < 3) | 0.113 | 0.005 | 0.024 | 1.716 (1.073–2.744) | ||

| TBS (≥ 8 vs. < 8) | 0.001 | 0.047 | 1.348 (1.005–1.809) | < 0.001 | 0.014 | 1.543 (1.093–2.177) |

| MVI (Yes vs. No) | 0.004 | 0.239 | 1.203 (0.885–1.636) | 0.001 | 0.431 | 1.162 (0.800–1.689) |

| EHS (Yes vs. No) | 0.367 | 0.153 | ||||

| First line (No vs. Yes) | 0.495 | 0.848 | ||||

| Combination with local therapy (Yes vs. No) | 0.005 | 0.008 | 0.701 (0.539–0.912) | 0.004 | 0.011 | 0.665 (0.485–0.911) |

| PD-1 inhibitor (Others vs. Pembrolizumab) | 0.451 | 0.332 | ||||

Bold values indicate p ≤ 0.05

AFP alpha-fetoprotein, BCLC Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer, CI confidence interval, ECOG Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, EHS extra-hepatic spread, HBV hepatitis B virus, HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, HCV chronic hepatitis C virus, HR hazard radio, MVI macrovascular invasion, OS overall survival, PFS progression-free survival, TBS tumor burden score

Fig. 3.

Kaplan‒Meier curves for overall survival stratified by Child‒Pugh classification (A), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) score (B), involved organs (C), tumor burden score (D), Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage (E), and combination with local therapy (F) subgroups

For PFS analysis, 361 patients were analyzed. The median PFS was 6.9 months (95% CI 6.0–7.9) (Fig. 2B), and the 0.5-year and 1-year PFS rates were 44.0% (95% CI 38.9–49.2) and 15.0% (95% CI 11.3–18.6), respectively. Based on multivariate analysis, ECOG PS (1–2 vs. 0: HR 1.832; 95% CI 1.363–2.461, p < 0.001; 5.1 vs. 10.1 months; Fig. S1A) and TBS (high vs. low: HR 1.348; 95% CI 1.005–1.809, p = 0.047; 5.4 vs. 8.2 months, p = 0.001; Fig. S1B) were associated with a significantly shorter PFS (Table 3). However, combination with local therapy (yes vs. no: HR 0.701; 95% CI 0.539–0.912, p = 0.008; 7.8 vs. 5.5 months; Fig. S1C) was an independent predictor of a longer PFS.

In the intent-to-treat analysis of 378 patients based on the RECIST v1.1 criteria, objective responses were observed in 74 patients (19.6%, 95% CI 15.6–23.6), and disease control was observed in 295 patients (78.0%, 95% CI 73.9–82.2). If the tumor exhibited a response, the median duration of response (DOR) was 10.8 (95% CI 7.5–14.0) months. Half (50%) of the patients reached the DCB from lenvatinib plus PD-1 inhibitor therapy.

Safety

All patients were assessed for drug safety. The overall incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) was 100% (Table 4). However, TEAEs were grade 3/4 in 219 (57.9%) patients. The most frequent grade 3 to 4 TEAEs (> 5%) were hypertension (15.1%), increased blood bilirubin levels (8.5%), fatigue (7.7%), proteinuria (7.1%), decreased platelet count (6.9%), decreased appetite (6.3%), hypokalemia (6.3%), and diarrhea (5.8%). Grade 5 fatal AEs occurred in 5 patients (1.3%) and included upper gastrointestinal bleeding (four patients) and cerebral hemorrhage (one patient). Generally, almost (99.7%, 377/378) all-grade AEs may refer to lenvatinib, and just 21.4% (81/378) of all-grade AEs may relate to PD-1 inhibitors. On the other hand, also almost (96.8%, 212/219) of grade 3 to 4 AEs may refer to lenvatinib and just 23.3% (51/219) of grade 3 to 4 AEs may relate to PD-1 inhibitors. Moreover, in our study, about 24.9% (94/378) of patients experienced treatment discontinued due to AEs. In addition, 19.6% of 378 patients were treated with systematic corticosteroids to manage AEs.

Table 4.

Most common treatment-emergent adverse events in 378 Chinese un-resectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC) patients receiving lenvatinib plus PD-1 inhibitors

| Adverse events, n (%) | Any grade | Grade 3–4 | Grade 5 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment-emergent adverse events | 378 (100.0) | 219 (57.9) | 5 (1.3)* |

| Hypertension | 185 (48.9) | 57 (15.1) | |

| Increased blood bilirubin | 162 (42.9) | 32 (8.5) | |

| Fatigue | 241 (63.7) | 29 (7.7) | |

| Proteinuria | 89 (23.5) | 27 (7.1) | |

| Decreased platelet count | 139 (36.8) | 26 (6.9) | |

| Decreased appetite | 299 (79.1) | 24 (6.3) | |

| Hypokalemia | 89 (23.5) | 24 (6.3) | |

| Diarrhea | 87 (23) | 22 (5.8) | |

| Elevated aspartate aminotransferase | 154 (40.7) | 18 (4.8) | |

| Upper gastrointestinal bleeding | 52 (13.8) | 18 (4.8) | 4 (1.1) |

| Hyponatremia | 97 (25.7) | 12 (3.2) | |

| Decreased leukocytes | 99 (26.2) | 11 (2.9) | |

| Rash | 202 (53.4) | 10 (2.6) | |

| Elevated alanine aminotransferase | 160(42.3) | 8 (2.1) | |

| Decreased weight | 86 (22.8) | 8 (2.1) | |

| Palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia | 60 (15.9) | 7 (1.9) | |

| Pneumonia | 19 (5.0) | 7 (1.9) | |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 198 (52.4) | 6 (1.6) | |

| Pain | 68 (18) | 4 (1.1) | |

| Nausea | 51 (13.5) | 3 (0.8) | |

| Vomiting | 40 (10.6) | 2 (0.5) | |

| Dysphonia | 30 (7.9) | 2 (0.5) | |

| Pruritus | 23 (6.1) | 2 (0.5) | |

| Hypothyroidism | 126 (33.3) | 1 (0.3) | |

| Abdominal pain | 82 (21.7) | 1 (0.3) | |

| Fever | 65 (17.2) | 1 (0.3) | |

| Edema limbs | 33 (8.7) | 1 (0.3) | |

| Oral mucositis | 32 (8.5) | 1 (0.3) | |

| Periodontal disease | 30 (7.9) | 1 (0.3) | |

| Constipation | 25 (6.6) | 1 (0.3) | |

| Abdominal distension | 49 (13.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Epistaxis | 13 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) |

*Including cerebral hemorrhage (N = 1)

To clearly demonstrate AEs associated with lenvatinib plus different PD-1 inhibitors groups, we split AEs according to different treatment combinations (Table S2). The grade 3–4 TEAEs in lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab or nivolumab, sintilimab, camrelizumab, toripalimab, or tislelizumab were 56.5%, 81.0%, 57.0%, 57.7%, 56.8% and 41.7%, respectively, which is basically similar. For special ones, lenvatinib plus sintilimab group seems to have higher all-grade hypokalemia, hyponatremia and rash. Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab seems to have higher all-grade hypokalemia and upper gastrointestinal bleeding. For lenvatinib plus camrelizumab group, the incidence of all-grade diarrhea may be higher and the incidence of reactive cutaneous capillary endothelial hyperplasia (RCCEP) as special AE for camrelizumab occurred in about 14.4% (15/104) patients.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest real-world study of the use of lenvatinib plus PD-1 inhibitors in uHCC patients. We found that the median OS was 17.8 months and the median PFS was 6.9 months. The ORR and DCR were 19.6% and 73.5%, respectively. We also found that Child‒Pugh grade, BCLC stage, ECOG, involved organs, TBS, and combination with local therapy were independent prognostic factors for OS.

Many other cohort studies have also reported the efficacy of lenvatinib plus PD-1 inhibitors in uHCC patients. The phase I Keynote-524 study, the most representative study, reported that an ORR of 36.0% was reached in 100 uHCC patients treated with lenvatinib plus the PD-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab. Moreover, the median PFS and median OS were 8.6 months and 22.0 months, respectively [15]. However, the phage 3 LEAP-002 study found that compared with lenvatinib plus placebo in patients with uHCC, lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab did not significantly increase OS (21.2 vs. 19.0 months, HR 0.840, p = 0.0227 > 0.0185) [10]. The negative LEAP-002 study found that OS in the lenvatinib plus placebo arm (19.0 months) was longer than that in the lenvatinib arm (13.6 months) in the 2018 REFLECT study [4] due to higher rates (22.8%) and efficacy of sequential immunotherapy [10]. In our cohorts, 18.3% (69/378) of patients were treated with the same drug of lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab combination therapy as in the LEAP-002 study [10], but we did not find significant differences for lenvatinib plus other kinds of PD-1 inhibitor (p = 0.33) in our study. For lenvatinib plus sintilimab or camrelizumab, which is the most employed anti-PD-1 inhibitors in our study, some small cohorts found that the mPFS of this combination therapy is approximately 8.0–11.3 months [30–32], which is comparable with that reported in the mPFS in the LEAP-002 study (8.2 months) and our present study (6.9 months).

In the Keynote-524 study [15] and LEAP-002 study [10], patients were excluded if they had with Child–Pugh class B or C liver function, invasion at the main portal vein (Vp4), ECOG‒PS with 2 scores, or received prior systemic therapy. However, in present real-world cohort, 22.5% patients were with Child–Pugh class B, and 13.0% patients were with ECOG‒PS scores of 2, and 18.0% received prior systemic therapy. The efficacy of the combination therapy in our real-world cohort was lower than that achieved in the Keynote-524 study [15] and LEAP-002 [10] because we think important baseline characteristics (Child‒Pugh score, BCLC stage, ECOG PS scores, MVI) were better in these two studies than in our present study. However, such parameters may also be more realistic in real-world practice in Asian uHCC patients who have a high rate of HBV infection. We hope to get more details to compare our cohort with the LEAP-002 study when the LEAP-002 study was published "in extenso".

In clinical practice, the main concern is selecting patients who would benefit from the therapy [33]. We found that worse ECOG PS (1–2 vs. 0) was a negative prognostic factor for OS (HR = 2.209, p < 0.001) and PFS (HR = 1.832, p < 0.001). Patients with worse Child‒Pugh grades (B vs. A) had a shorter OS (HR = 1.675, p = 0.005) but not PFS (p > 0.05) in multivariate analysis. Many studies have found that the ECOG score and Child‒Pugh grade are prognostic factors for patients with uHCC who were administered lenvatinib and/or PD-1 inhibitors [34–36]. Wu et al. found in multivariate analyses that the Child‒Pugh class (Class B vs. A, HR = 2.646, p = 0.039) but not an ECOG score of ≥ 1 (HR = 1.889, p = 0.162) was a poor prognostic factor for survival in uHCC patients treated with lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab [35]. Choi et al. studied 203 Korean patients with uHCC treated with nivolumab and found that the Child‒Pugh B group had a shorter mOS (2.8 vs. 10.7 months; HR = 2.10; p < 0.001) but not mPFS (HR = 1.17, p = 0.430) [37]. Patients with worse ECOG PS or worse liver function might benefit less from lenvatinib plus PD-1 inhibitors, so the application of drugs should be done with caution.

Tumor characteristics are very important for survival in patients with uHCC [38]. We found that the involved organs and TBS may influence PFS and OS. In a post-analysis of the REFLECT study of patients with uHCC treated with lenvatinib or sorafenib, the number of tumor sites at baseline was a very important prognostic factor (p < 0.001) for OS in multivariate analysis [39]. Moreover, we found that combination loco-regional therapy was an independent factor for both better PFS and OS. This result was consistent with the results of previous studies that found that adding loco-regional therapy to a lenvatinib plus PD-1 inhibitor or lenvatinib monotherapy regimen could lead to a high response and long survival [9, 40–44].

The most frequent AEs were consistent with the use of lenvatinib monotherapy [4]. We think these common AEs may be related to the anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) target mechanism [4, 45]. Regarding safety, ≥ grade 3 TEAEs need to be closely monitored. In the Keynote-524 study, grade 3 TEAEs were hypertension (18%), increased AST levels (14%), increased lipase levels (11%), diarrhea (7%), increased blood bilirubin levels (6% at level 3 and 2% at level 4), fatigue (6%), asthenia (6%), increased ALT levels (6%), decreased weight (5%) and proteinuria (5%) [15]. In the LEAP-002 study, 96.5% and 61.5% of uHCC patients underwent all-grade treatment-related adverse events (TRAE) and grade 3–4 TRAEs [10], respectively, which is similar to our study. However, in our study, 24.9% of treatment discontinuation due to AEs may be higher than about 18.0% in the Keynote-524 study [15] and LEAP-002 study [10]. It may be related to follow-up closely and real-world setting-based practice. We think careful management and adjustment of the drug dose may be important to address AEs and may prolong the duration of treatment and survival [46]. Notably in our cohort, fatigue, decreased appetite, and gastrointestinal bleeding may need closer monitoring and good management. Meanwhile, fatigue and decreased appetite may lead to low quality of life, while gastrointestinal bleeding is always life-threatening, especially in patients with chronic liver disease [47]. In real-world practice, doctors should be reminded to carefully monitor patients’ safety due to patients’ irregular visits and the influence of the coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) pandemic. There are several limitations in our study. First, potential bias could not easily be avoided due to the nature of the retrospective design. Second, multiple kinds of PD-1 inhibitors were heterogeneous and some were off-label used in the study; however, we did not find a significant difference when comparing the use of other PD-1 inhibitors with the use of pembrolizumab. Third, our cohort was predominantly HBV-infected uHCC patients, and the applicability of these findings to non-HBV-infected uHCC patients remains to be further validated in real-world practice.

Conclusions

In conclusion, a real-world study found that lenvatinib plus PD-1 inhibitors achieved long survival and considerable response in uHCC patients in China. The tolerability of combination therapy was acceptable but should be monitored closely in real-world practice.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 Figure S1. Kaplan‒Meier curves for progression-free survival stratified by Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) score (A), tumor burden score (B), and combination with local therapy (C) subgroups. (PDF 836 KB)

Abbreviations

- AFP

Alpha-fetoprotein

- ALT

Elevated alanine aminotransferase

- AST

Aspartate aminotransferase

- BCLC

Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer

- CI

Confidence interval

- CR

Complete response

- CTCAE

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events

- DCR

Disease control rate

- DCB

Durable clinical benefit

- DOR

Duration of response

- ECOG

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- EHS

Extrahepatic spread

- HBV

Hepatitis B virus

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- HCV

Chronic hepatitis C virus

- HAIC

Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy

- IQR

Interquartile range

- MVI

Macrovascular invasion

- ORR

Objective response rate

- OS

Overall survival

- PD

Progressive disease

- PFS

Progression-free survival

- PD-1

Programmed death 1

- PR

Partial response

- RECIST

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors

- PLAGH

People’s Liberation Army General Hospital

- PS

Performance status

- PUMCH

Peking Union Medical College Hospital

- SD

Stable disease

- TBS

Tumor burden score

- TACE

Transarterial chemoembolization

- TEAE

Treatment-emergent adverse event

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

Author contributions

HZ, YL, XY, BC, YW, and YW contributed to the conception and design of the study. HZ, YL, XY, BC, YW, and YW performed the data collection and analysis. HZ, YL, XY, BC, YW, YW, JL, NZ, JX, ZX, LZ, JC, JL, JL, FX, DW, YL, HS, JP, KH, MG, LH, JS, LY, LZ, JZ, ZL, XY, YM, and XS provided study materials or patients. HZ, YL, XY, BC, YW, and YW contributed to data collection. HZ, YL, XY, BC, YW, and YW contributed to data analysis and interpretation. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding

This work was supported by the National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (2022-PUMCH-B-128), CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS) (2022-I2M-C&T-A-003, 2021-I2M-1-061 and 2021-I2M-1-003), CAMS Clinical and Translational Medicine Research Funds (2019XK320006), CSCO-Hengrui Cancer Research Fund (Y-HR2019-0239, Y-HR2020MS-0414 and Y-HR2020QN-0415), CSCO-MSD Cancer Research Fund (Y-MSDZD2021-0213), and National Ten-Thousand Talent Program. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Data availability statementinvestigate the real-world efficacy

All data supporting the findings of this study are available in this article and its online supplementary material files. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Xu Yang, Bowen Chen, Yanyu Wang, Yunchao Wang, Junyu Long, Nan Zhang, Jingnan Xue, Ziyu Xun, Linzhi Zhang, Jiamin Cheng, Jin Lei, Huishan Sun, Yiran Li, Jianzhen Lin, Fucun Xie, Dongxu Wang, Jie Pan, Ke Hu, Mei Guan, Li Huo, Jie Shi, Lingxiang Yu, Lin Zhou, Jinxue Zhou, Zhenhui Lu, Xiaobo Yang, Yilei Mao, Xinting Sang, Yinying Lu, Haitao Zhao declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical statement

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and it was approved by the Institutional Review Board of PUMCH (IRB No. JS-1391) and the Fifth Medical Center of PLAGH (IRB No. KY-2022-4-24-1). Written informed consent was collected from all patients before the application of medication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Xu Yang, Bowen Chen, and Yanyu Wang have contributed equally.

Contributor Information

Yinying Lu, Email: luyinying2017@sina.com.

Haitao Zhao, Email: zhaoht@pumch.cn.

References

- 1.Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, Singal AG, Pikarsky E, Roayaie S, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7:6. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-00240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018 doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378–390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, Han KH, Ikeda K, Piscaglia F, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391:1163–1173. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30207-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1894–1905. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1915745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abou-Alfa Ghassan K, Lau G, Kudo M, Chan Stephen L, Kelley Robin K, Furuse J, et al. Tremelimumab plus durvalumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. NEJM Evidence. 2022 doi: 10.1056/EVIDoa2100070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng AL, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, et al. Updated efficacy and safety data from IMbrave150: atezolizumab plus bevacizumab vs. sorafenib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2022;76:862–873. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelley RK, Rimassa L, Cheng AL, Kaseb A, Qin S, Zhu AX, et al. Cabozantinib plus atezolizumab versus sorafenib for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (COSMIC-312): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022 doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00326-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peng Z, Fan W, Zhu B, Wang G, Sun J, Xiao C, et al. Lenvatinib combined with transarterial chemoembolization as first-line treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III, randomized clinical trial (LAUNCH). J Clin Oncol 2022:Jco2200392. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Finn RS, Kudo M, Merle P, Meyer T, Qin S, Ikeda M, et al. LBA34 Primary results from the phase III LEAP-002 study: Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab versus lenvatinib as first-line (1L) therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (aHCC) Ann Oncol. 2022;33:S1401. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.08.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rimini M, Shimose S, Lonardi S, Tada T, Masi G, Iwamoto H, et al. Lenvatinib versus Sorafenib as first-line treatment in hepatocellular carcinoma: a multi-institutional matched case-control study. Hepatol Res. 2021;51:1229–1241. doi: 10.1111/hepr.13718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patwala K, Prince DS, Celermajer Y, Alam W, Paul E, Strasser SI, et al. Lenvatinib for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma-a real-world multicenter Australian cohort study. Hepatol Int. 2022;16:1170–1178. doi: 10.1007/s12072-022-10398-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Obi S, Sato T, Sato S, Kanda M, Tokudome Y, Kojima Y, et al. The efficacy and safety of lenvatinib for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in a real-world setting. Hepatol Int. 2019;13:199–204. doi: 10.1007/s12072-019-09929-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fu Z, Li X, Zhong J, Chen X, Cao K, Ding N, et al. Lenvatinib in combination with transarterial chemoembolization for treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC): a retrospective controlled study. Hepatol Int. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s12072-021-10184-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finn RS, Ikeda M, Zhu AX, Sung MW, Baron AD, Kudo M, et al. Phase Ib study of lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:2960–2970. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.00808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kudo M Ikeda M, Motomura K, Okusaka T, Kato N, Dutcus CE, et al. A phase Ib study of lenvatinib (LEN) plus nivolumab (NIV) in patients (pts) with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC): Study 117. J Clin Oncol 2020;38 suppl 4; abstr 513.

- 17.Qin S, Ren Z, Feng YH, Yau T, Wang B, Zhao H, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab versus sorafenib in the Chinese subpopulation with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: phase 3 randomized, open-label IMbrave150 study. Liver Cancer. 2021;10:296–308. doi: 10.1159/000513486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qin S, Ren Z, Meng Z, Chen Z, Chai X, Xiong J, et al. Camrelizumab in patients with previously treated advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicentre, open-label, parallel-group, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:571–580. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ren Z, Fan J, Xu J, Bai Y, Xu A, Cang S, et al. LBA2 Sintilimab plus bevacizumab biosimilar vs sorafenib as first-line treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (ORIENT-32) 2. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:S1287. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.10.134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu J, Shen J, Gu S, Zhang Y, Wu L, Wu J, et al. Camrelizumab in combination with apatinib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (RESCUE): a nonrandomized, open-label, phase II trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27:1003–1011. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-2571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heimbach JK, Kulik LM, Finn RS, Sirlin CB, Abecassis MM, Roberts LR, et al. AASLD guidelines for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2018;67:358–380. doi: 10.1002/hep.29086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou J, Sun HC, Wang Z, Cong WM, Wang JH, Zeng MS, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of primary liver cancer in China (2017 Edition) Liver Cancer. 2018;7:235–260. doi: 10.1159/000488035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address eee, European Association for the Study of the L. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2018;69:182–236. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Schwartz LH, Litière S, de Vries E, Ford R, Gwyther S, Mandrekar S, et al. RECIST 1.1-Update and clarification: from the RECIST committee. Eur J Cancer. 2016;62:132–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.03.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quispel-Janssen J, van der Noort V, de Vries JF, Zimmerman M, Lalezari F, Thunnissen E, et al. Programmed death 1 blockade with nivolumab in patients with recurrent malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13:1569–1576. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rimassa L, Danesi R, Pressiani T, Merle P. Management of adverse events associated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: improving outcomes for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Treat Rev. 2019;77:20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2019.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brahmer JR, Lacchetti C, Schneider BJ, Atkins MB, Brassil KJ, Caterino JM, et al. Management of immune-related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: American society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1714–1768. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.6385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sasaki K, Morioka D, Conci S, Margonis GA, Sawada Y, Ruzzenente A, et al. The tumor burden score: a new, "Metro-ticket" prognostic tool for colorectal liver metastases based on tumor size and number of tumors. Ann Surg. 2018;267:132–141. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vitale A, Lai Q, Farinati F, Bucci L, Giannini EG, Napoli L, et al. Utility of tumor burden score to stratify prognosis of patients with hepatocellular cancer: results of 4759 cases from ITA.LI.CA study group. J Gastrointest Surg. 2018;22:859–871. doi: 10.1007/s11605-018-3688-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wei F, Huang Q, He J, Luo L, Zeng Y. Lenvatinib plus camrelizumab versus lenvatinib monotherapy as post-progression treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a short-term prognostic study. Cancer Manag Res. 2021;13:4233–4240. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S304820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen K, Wei W, Liu L, Deng ZJ, Li L, Liang XM, et al. Lenvatinib with or without immune checkpoint inhibitors for patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma in real-world clinical practice. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00262-021-03060-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao L, Chang N, Shi L, Li F, Meng F, Xie X, et al. Lenvatinib plus sintilimab versus lenvatinib monotherapy as first-line treatment for advanced HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective, real-world study. Heliyon. 2022;8:e09538. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lui TKL, Cheung KS, Leung WK. Machine learning models in the prediction of 1-year mortality in patients with advanced hepatocellular cancer on immunotherapy: a proof-of-concept study. Hepatol Int. 2022;16:879–891. doi: 10.1007/s12072-022-10370-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsuchiya K, Kurosaki M, Sakamoto A, Marusawa H, Kojima Y, Hasebe C, et al. The real-world data in japanese patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma treated with lenvatinib from a nationwide multicenter study. Cancers. 2021;13:2608. doi: 10.3390/cancers13112608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu CJ, Lee PC, Hung YW, Lee CJ, Chi CT, Lee IC, et al. Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab for systemic therapy-naïve and -experienced unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s00262-022-03185-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuo HY, Chiang NJ, Chuang CH, Chen CY, Wu IC, Chang TT, et al. Impact of immune checkpoint inhibitors with or without a combination of tyrosine kinase inhibitors on organ-specific efficacy and macrovascular invasion in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Res Treat. 2020;43:211–220. doi: 10.1159/000505933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choi W-M, Lee D, Shim JH, Kim KM, Lim Y-S, Lee HC, et al. Effectiveness and safety of nivolumab in child-pugh B patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a real-world cohort study. Cancers. 2020;12:1968. doi: 10.3390/cancers12071968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim HS, Kim CG, Hong JY, Kim I-h, Kang B, Jung S, et al. The presence and size of intrahepatic tumors determine the therapeutic efficacy of nivolumab in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2022;14:17588359221113266. doi: 10.1177/17588359221113266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, Han K-H, Ikeda K, Cheng A-L, et al. Overall survival and objective response in advanced unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A subanalysis of the REFLECT study. J Hepatol 2022. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Cai M, Huang W, Huang J, Shi W, Guo Y, Liang L, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization combined with lenvatinib plus PD-1 inhibitor for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective cohort study. Front Immunol. 2022;13:848387. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.848387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cao F, Yang Y, Si T, Luo J, Zeng H, Zhang Z, et al. The efficacy of TACE combined with lenvatinib plus sintilimab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicenter retrospective study. Front Oncol. 2021;11:783480. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.783480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu JY, Yin ZY, Bai YN, Chen YF, Zhou SQ, Wang SJ, et al. Lenvatinib combined with anti-PD-1 antibodies plus transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicenter retrospective study. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 2021;8:1233–1240. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S332420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.He MK, Liang RB, Zhao Y, Xu YJ, Chen HW, Zhou YM, et al. Lenvatinib, toripalimab, plus hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy versus lenvatinib alone for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2021;13:17588359211002720. doi: 10.1177/17588359211002720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xiang YJ, Wang K, Yu HM, Li XW, Cheng YQ, Wang WJ, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization plus a PD-1 inhibitor with or without lenvatinib for intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res. 2022;52:721–729. doi: 10.1111/hepr.13773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmidinger M. Understanding and managing toxicities of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitors. EJC Suppl. 2013;11:172–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcsup.2013.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schneider BJ, Naidoo J, Santomasso BD, Lacchetti C, Adkins S, Anadkat M, et al. Management of immune-related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: ASCO guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:4073–4126. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.01440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rapposelli IG, Tada T, Shimose S, Burgio V, Kumada T, Iwamoto H, et al. Adverse events as potential predictive factors of activity in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with lenvatinib. Liver Int. 2021;41:2997–3008. doi: 10.1111/liv.15014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file1 Figure S1. Kaplan‒Meier curves for progression-free survival stratified by Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) score (A), tumor burden score (B), and combination with local therapy (C) subgroups. (PDF 836 KB)

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available in this article and its online supplementary material files. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.