Abstract

Bacteria, similar to most organisms, have a love–hate relationship with metals: a specific metal may be essential for survival yet toxic in certain forms and concentrations. Metal ions have a long history of antimicrobial activity and have received increasing attention in recent years owing to the rise of antimicrobial resistance. The search for antibacterial agents now encompasses metal ions, nanoparticles and metal complexes with antimicrobial activity (‘metalloantibiotics’). Although yet to be advanced to the clinic, metalloantibiotics are a vast and underexplored group of compounds that could lead to a much-needed new class of antibiotics. This Review summarizes recent developments in this growing field, focusing on advances in the development of metalloantibiotics, in particular, those for which the mechanism of action has been investigated. We also provide an overview of alternative uses of metal complexes to combat bacterial infections, including antimicrobial photodynamic therapy and radionuclide diagnosis of bacterial infections.

Subject terms: Medicinal chemistry, Drug discovery and development, Mechanism of action, Antibiotics

Metals and their complexes with antimicrobial activity are a promising source of new antibiotics. Their 3D geometry and potential for multiple mechanisms of action are important assets; however, a substantial investment in research is needed to advance them to the clinic.

Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is on track to become the leading cause of death of world in the coming decades. In 2019, there were an estimated 4.95 million deaths associated with AMR, of which 1.3 million were directly attributable to resistant infections1. This number is expected to reach 10 million deaths per year worldwide by 20502, if not sooner due in part to the widespread over-prescription of antibiotics to COVID-19 patients over the past 2 years3. Despite this urgency, conventional organic medicinal chemistry has failed to replenish the depleted antimicrobial pipeline: a 2022 analysis showed that, as of June 2021, there were only 45 ‘traditional’ antibiotics in clinical development4. Hence, new approaches for developing the next generation of antibiotics are urgently needed.

Inorganic compounds, organometallic compounds, and/or metal complexes have had a small but seminal role in twentieth-century medicine. The discovery and regulatory approval of the anticancer drug cisplatin heralded the modern era of medicinal inorganic chemistry. Since then, many metal-containing compounds have been studied for the treatment of diseases, with several entering human clinical trials5. However, only recently have metals and metalloantibiotics gained considerable attention as potential antimicrobials, in response to the rapid rise of AMR in the past decade.

This Review covers the current state of metals and metalloantibiotics as antibacterial agents. We discuss the role of metal ions in bacteria and the potential of some metal ions to directly kill bacterial pathogens, along with strategies to hijack bacterial metal-ion pathways for antimicrobial activity. We focus on antibacterial metal complexes and present examples for which the mechanism of action has been (at least partially) elucidated. The Review includes a brief overview of the application of light-activated metal compounds against bacteria as an example of alternative mechanism of action that are possible with metalloantibiotics. We conclude by discussing the use of complexes of radioactive metal isotopes to improve the diagnosis of bacterial infections by visualizing their location, in a similar fashion to the detection of cancer through imaging.

This Review does not include a comprehensive list of all metalloantibiotics: interested readers are referred to excellent reviews that have been published on this topic6–16. Regiel-Futyra et al.17 recently reviewed bioinorganic strategies against bacteria. A comprehensive look at the molecular and cellular targets of metal ions was published by Lemire et al.18 in 2013. The use of metal complexes as adjuvants or potentiators, in combination with antibiotics or other biologically active compounds, is another fertile field of research, but beyond the scope of this Review. A significant body of research has been published on the use of nanoparticles as antimicrobial agents and has been reviewed elsewhere19,20. Finally, for metal-based antifungal compounds, we refer to the recent review by Lin et al.21.

Metals and bacteria

Metal ions are essential for all living organisms. In bacteria, metal-ion-containing enzymes catalyse almost half of all biochemical reactions, requiring the cell to maintain homeostasis for essential metals at sufficiently high levels to meet cellular demands and low enough to avoid toxicity22. Research into the essentiality of metal ions within biological processes is ever-evolving. To date, it has been shown that the key metals required by most organisms are the first-row transition metals such as manganese, iron, cobalt, nickel, copper and zinc23. Bacteria use specific uptake mechanisms to acquire essential metals. For example, nickel and copper are transported by NikMNQO and CbiMNQO uptake systems, respectively24. Cobalt is the centrally coordinated ion in cyclic tetrapyrroles known as corrin rings, such as the cobalamin at the centre of vitamin B12 (ref. 25). Bacterial handling of copper is believed to involve metallochaperones that deliver copper from import pumps to most bacterial cuproenzymes26. Other metals that are important, but not essential, include the redox-active transition metals molybdenum (Mo) and tungsten (W). They are incorporated into enzymes, mediate various reactions and have significant roles in supporting virulence in pathogenic bacteria27. Zinc and iron systems are described in greater detail below.

The host immune system uses several strategies that alter the homeostasis of transition metals to combat invading pathogens28–31. For example, the bacterial acquisition of iron is hindered by the host protein lipocalin, which binds to the siderophores that bacteria use to sequester iron from their environment32. Another host protein, calprotectin, appears to sequester manganese at sites of infection33, with other studies providing additional evidence that manganese is depleted around infecting bacteria by both extracellular manganese chelation and intracellular manganese transport28.

Zinc has an important role in normal host immune function34. At a cellular level, macrophages can adopt divergent strategies of both zinc starvation and zinc toxicity to kill the bacteria they engulf. Mammalian macrophages contain a range of zinc transporters that can alter their intracellular zinc concentrations. For example, upregulation of the SLC30A family that exports zinc from macrophages leads to zinc starvation of intracellular bacteria, whereas upregulation of the SLC39A family that imports zinc leads to zinc toxicity30,35,36. In response to elevated zinc concentrations, bacteria can turn on regulators such as ZntR, which induce the bacterial ZntA to export zinc; in contrast, when starved of zinc, they can activate transporter systems such as the ZnuABC ATP-binding cassette to import zinc30,37–39. For example, when putative zinc efflux pumps were deleted from Streptococcus pyogenes, the bacteria became more susceptible to zinc and to their killing by human neutrophils, with the addition of a zinc chelator restoring survival back to wild-type levels40. Global RNA sequencing of mouse macrophages during infection with Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium showed increases in cytosolic zinc (45 times higher than that before infection) but depletion of zinc within the phagosome. This limits the bacterial access to zinc while providing sufficient zinc for the immune response41. During Streptococcus pneumoniae infection, elevated zinc concentrations have been shown to inhibit PsaA — the manganese transport system of the bacteria — impairing the ability of bacteria to colonize the human host42,43. At a macroscopic level, the importance of host manipulation of zinc levels during bacterial infections has been highlighted by 2D elemental analysis of tissue abscesses caused by Staphylococcus aureus, which showed almost no detectable zinc (or manganese) in the abscess, in contrast with high levels in the surrounding tissue33. Zinc also has an important role in the metallo-β-lactamases that inactivate most β-lactam antibiotics, because these are zinc-dependent hydrolases44.

Iron is indispensable for bacteria, with vital roles in DNA replication, transcription, repair, biosynthesis of cofactors, ATP synthesis, nucleotide biosynthesis and so on45–47. However, in human hosts, free iron concentrations are extremely low (between 10−9 and 10−18 M)48 because most iron is complexed to iron-storage or iron-transport proteins. Consequently, bacteria must sequester iron from the environment of their host and transport it inside the bacterial cell to enable their survival49. These iron chelators, known as siderophores or metallophores, are produced and secreted then outcompete the iron-chelating proteins of the host (or other iron-binding factors in other environments) to solubilize and sequester iron before being reimported with their iron cargo50. Bacteria can also acquire iron by targeting the iron-containing haemoglobin of the host using haemoglobin-binding proteins and specific transporters, as recently described for Corynebacterium diphtheria51.

In summary, it is clear that careful regulation of intracellular metal concentrations is crucial for bacterial survival.

Antibacterial strategies based on metal uptake

The rise in antibiotic resistance requires new strategies to develop novel antimicrobials. Given that bacteria require metal uptake for their survival and proliferation, drugs that target these uptake pathways are a promising approach. This section explores how specific metal uptake pathways in bacteria can be used and provides examples of antibiotics that use this strategy.

Metallophores

Metallophores are low-molecular-mass organic ligands that supply metal-ion nutrients to an organism. Thus, siderophores are metallophores with exceptionally high specificity and affinity towards iron, particularly the Fe3+ (ferric) ionic form. Several hundred different siderophores have been identified and reviewed, with different bacteria and fungi producing different types52–54 and with some microorganisms even using siderophores from other species55. Although structurally diverse, siderophores are typically hexadentate, containing three bidentate functional groups, such as catechols (for example, enterobactin), hydroxamates (for example, ferrioxamine B) and α-hydroxy carboxylates (for example, staphyloferrin A) (Fig. 1a), which facilitate the preferred octahedral coordination geometry of Fe3+ (ref. 56). Siderophores with reduced coordination (that is, bidentate, tridentate and tetradentate) have also been identified, but they generally exhibit lower affinity for Fe3+ than their hexadentate counterparts57,58. Siderophores can also bind the Fe2+ (that is, ferrous) form of iron, as well as other metals; however, their affinity for Fe3+ is generally much higher59,60.

Fig. 1. Chemical structures of metallophores and metallophore–antibiotic conjugates.

a, Examples of naturally occurring metallophores with different metal-binding motifs: enterobactin, an example of a catechol-based metallophore; ferrioxamine B, an example of a hydroxamate-based metallophore and staphyloferrin A, an example of an α-hydroxy carboxylate. b, Chemical structures of metallophore–antibiotic conjugates: albomycin δ1, a naturally occurring metallophore–antibiotic; cefiderocol, one of the first synthetic metallophore–antibiotics approved for clinical use; GSK3342830, BAL30072, MC-1 and MB-1, which are synthetic metallophore–antibiotics in clinical development from various pharmaceutical companies, as well as galbofloxacin and Ent-Cipro, which are synthetic metallophore–antibiotics prepared by academic groups. The metallophore in each example is shown in blue.

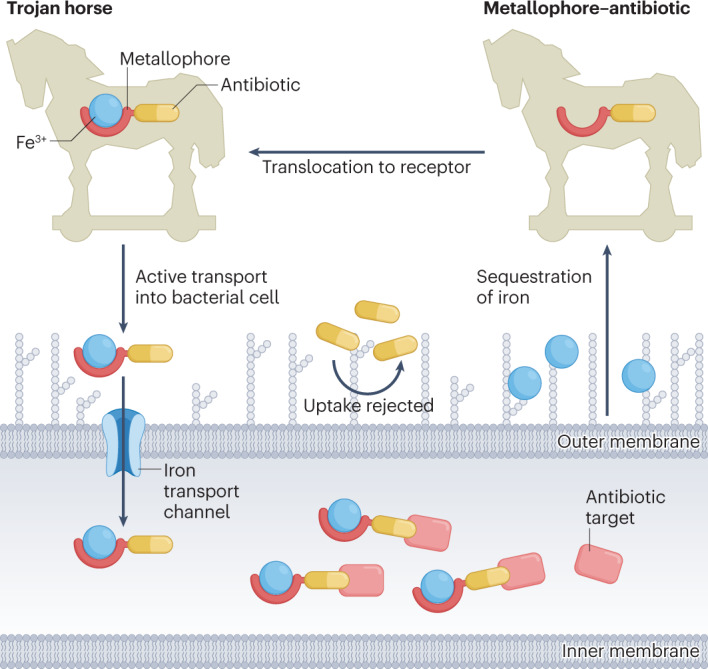

Bacteria have evolved specific transport channels to ensure successful translocation of iron–metallophore complexes into cells61. This is a requirement for Gram-negative bacteria, which contain an outer membrane that prevents many molecules, such as antibiotics and other small compounds, from passively entering the cell62. In most bacteria, TonB-dependent transporters recognize specific iron–metallophore complexes and enable their passage into the cell63,64. Remarkably, to outcompete rival bacterial species, some bacteria (for example, Streptomyces sp.) have developed their own antibacterial agents that are composed of a metallophore conjugated to an antimicrobial warhead (for example, albomycin (Fig. 1b) isolated from Streptomyces griseus65), effectively deceiving the target bacteria into actively internalizing a lethal toxin65,66. This metallophore–antibiotic strategy has been termed the Trojan horse approach (Fig. 2), because the idea is reminiscent of the tactic used in Greek mythology to conquer the city of Troy.

Fig. 2. Trojan horse strategy.

The metallophore–antibiotic conjugate sequesters iron from its local environment and is actively transported into the bacterial cell where the antibiotic portion of the compound can act on its target.

Academia and industry have attempted to mimic nature’s innovation to develop novel metallophore-based antimicrobials. However, there are several considerations that must be addressed before this can be realized: these include broadening the high bacterial specificity of many metallophores, selecting an appropriate antibiotic cargo and target location, and utilizing an appropriate linker strategy. The TonB-dependent transporters are generally highly selective for specific metallophores and will not allow the passage of structurally different metallophores67, making it difficult to generate broad-spectrum agents. The type of antibiotic is important, as the location of the antibiotic target varies, and successful uptake of the conjugate does not guarantee transport to all target locations. Most successful metallophore–antibiotic conjugates use antibiotics with periplasmic targets (such as β-lactams), because this is where metallophores are initially delivered, and the inner membrane limits their diffusion into the cytoplasm. Antibiotics with cytoplasmic targets therefore require a more complex approach that involves cleavage of the metallophore portion of the conjugate in the periplasm to allow for subsequent passage of the free antibiotic through the inner membrane. Ideally, this linker should remain stable while transported into the periplasm, but cleave upon cell entry. Several cleavable linkers have been developed and reviewed68.

Despite these limitations, the Trojan horse approach has been applied to many antibiotics, with one construct in clinical use. In 2019, cefiderocol (Shionogi & Co) became one of the first metallophore–antibiotic conjugates to be approved for clinical use when it was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and later by the European Medicines Agency (2020). Cefiderocol (Fig. 1b) is composed of a catechol (that is, a bidentate metallophore) covalently tethered via a non-cleavable linker to ceftazidime (that is, a third-generation cephalosporin). It exhibits potent activity against a range of carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative clinical isolates, most of which are highly resistant to the parent compound and other β-lactams69. Several other pharmaceutical companies have progressed metallophore–antibiotic conjugates into preclinical development or clinical trials. GSK3342830 of GlaxoSmithKline (Fig. 1b), which is similar to cefiderocol, showed promising in vitro activity against carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii70. GSK3342830 entered phase I clinical trials in 2016 but was terminated in 2018 owing to significant side effects71. Basilea Pharmaceutica created a metallophore–monobactam, BAL30072 (Fig. 1b), which displayed potent activity against several multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens72. BAL30072 began phase I clinical trials in 2010 but was abandoned because of hepatotoxicity73. Pfizer developed at least two metallophore–antibiotic conjugates on the basis of a monobactam core (MC-1 and MB-1; Fig. 1b). Both exhibited promising in vitro activity against several multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens but were not suitable for progression into clinical trials74–76: MC-1 was hydrolytically unstable with high plasma protein affinity74 and MB-1 exhibited low in vivo efficacy in a neutropenic murine infection model77.

Although the pharmaceutical industry has demonstrated some success with the metallophore–antibiotic approach, their reported conjugates have predominantly used only β-lactams and bidentate catechol-based metallophores. By contrast, conjugates produced by academic groups have explored a greater diversity of both metallophores and antibiotic classes, as discussed in several reviews54,78–81. For example, Miller and co-workers82 produced several hydroxamate-based metallophore–fluoroquinolone conjugates with activity against S. aureus, as well as a synthetic mixed catechol-hydroxamate metallophore–daptomycin conjugate that converted a Gram-positive antibiotic into one with potent activity against multidrug-resistant A. baumannii clinical isolates83.

Metallophore–antibiotics can use the specificity of metallophore uptake or the specificity of linker cleavage to create narrow-spectrum drugs that target specific pathogenic bacteria. This overcomes one liability of broad-spectrum antibiotics: their potential to facilitate the emergence of resistance by selecting for resistant mutants in non-pathogenic commensal bacteria, which subsequently transfer this resistance to pathogenic strains84. For example, Budzikiewicz and co-workers85,86 produced several pyoverdine-based (a Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain-specific siderophore) metallophore–β-lactam conjugates, which exhibited potent activity against specific P. aeruginosa strains. In another example, Nolan and co-workers87 developed an enterobactin-based (that is, triscatecholate) metallophore–ciprofloxacin conjugate with a pathogen-specific cleavable linker, Ent-Cipro (Fig. 1b). Ent-Cipro was shown to enter via the iron-uptake pathway; however, the release of the antibiotic payload required an esterase, which is predominantly expressed in pathogenic bacteria, such as uropathogenic Escherichia coli.

Although most groups tend to use natural metallophores to develop their metallophore–antibiotic conjugates, some have found success in developing artificial metallophores. For example, Brönstrup and co-workers produced several multipurpose metallophores on the basis of the enterobactin core88,89. One was recently linked to several different antibiotics (five β-lactams and daptomycin), producing a conjugate with potent, nanomolar activity against several Gram-positive and Gram-negative multidrug-resistant pathogens89.

The ability of metallophores to complex and transport metals into bacterial cells has also led to an alternative strategy for developing antimicrobial agents: complexing other antimicrobial metals and delivering potentially lethal concentrations of them into bacterial cells. A gallium (Ga) complexed desferrichrome-based (trishydroxamate) metallophore–ciprofloxacin conjugate, galbofloxacin90,91 (Fig. 1b), exhibited higher potency against S. aureus than the parent compound (ciprofloxacin), the uncomplexed galbofloxacin derivative and even the corresponding iron-complexed galbofloxacin derivative90. This compound demonstrates how preloading metallophore–antibiotic conjugates with other metal payloads can improve potency. However, the universality of this approach remains to be demonstrated.

Zinc ionophores

The susceptibility of bacteria to zinc toxicity has been leveraged for an alternative therapeutic approach, similar to the delivery of gallium described earlier. For example, the zinc ionophore PBT2 is a moderate-affinity 8-hydroxyquinoline transition metal ligand that was developed as a potential treatment for Alzheimer disease and Huntington’s disease because of its ability to redistribute cobalt and zinc92 and has completed several phase II clinical trials93. A repurposing study found that the combination of PBT2 and zinc could directly kill bacteria in vitro and also act as a ‘potentiator’, re-sensitizing multidrug-resistant group A Streptococcus, methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus to tetracycline, erythromycin and vancomycin, respectively, both in vitro and in vivo94. Increased bacterial cellular concentrations of zinc were observed, accompanied by disruption of iron, manganese and copper content and significant changes in heavy-metal homeostasis gene transcription. Zinc and copper efflux systems were induced, as were manganese transport systems. However, antibiotic re-sensitization was not universal, but was dependent on the antibiotic type and bacterial resistance profile. Further studies demonstrated that PBT2 overcame the intrinsic resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to the lipopeptide antibiotics polymyxin B and colistin and its acquired resistance to tetracycline95. The Gram-negative potentiation activity extended to polymyxin-resistant, extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing, carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae, E. coli, A. baumannii and P. aeruginosa, again leading to susceptibility to colistin and polymyxin B, both in vitro and in vivo96. Increase in cellular zinc and manganese concentrations and a decrease in iron concentration were detected upon treatment of K. pneumoniae with PBT2; however, the cell size, zeta potential and membrane integrity were not affected. The ionophore approach has also been used to deliver copper, as summarized in a 2020 review97.

Metallo-β-lactamases — bacterially produced enzymes that inactivate a wide range of β-lactam antibiotics — use catalytic zinc ions in their active sites to cleave the β-lactam ring. Zinc chelators have been shown to inhibit the enzyme and restore sensitivity to carbapenem antibiotics98,99, as has a Cu-chelated analogue100. A zinc chelator has also been appended to the C terminus of the glycopeptide antibiotic vancomycin, enhancing potency by increasing binding in the vicinity of the cell-wall target via the formation of a zinc complex with pyrophosphate groups of cell-wall lipids101.

Antimicrobial metals

The use of free metal ions to kill bacteria and fungi has longstanding historical precedent. Some of the metal compounds described in the next section, particularly those without strong complexation of the metal, may, in fact, simply act as delivery agents for metal ions. However, metal-resistance genes have been reported among environmental bacteria that have been exposed to high metal concentrations in highly polluted industrial soils102–104 or in agricultural soil irrigated with polluted water105.

Silver

Silver is the metal with the greatest association with antimicrobial activity, both historically and currently106–109. Various medical products include silver, such as bandages, ointments and catheters110. Nanocrystalline silver (silver nanoparticles and colloidal silver), silver nitrate111 and silver sulfadiazine (a complex with the antibiotic sulfadiazine)112 are commonly used. Despite the different forms, Ag+ ions are generally believed to be the active component. The antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles varies with size, shape and surface characteristics (including surface coatings), but these differences are likely due to changes in the release kinetics of Ag+ ions and not because of the particles themselves113. Silver is often synergistic in vitro with a range of antibiotics, such as ampicillin114,115, tobramycin116, gentamicin115,117, ofloxacin115, cefotaxime117, ceftazidime117, meropenem117 and ciprofloxacin117.

A 2019 meta-analysis of high-quality studies on the use of silver in wound care found potential short-term benefits when nanocrystalline silver was used to treat infected wounds, but delayed healing in burns treated with silver sulfadiazine. Overall, the analysis found that the quality of the published research on silver was poor118. Similarly, the efficacy of antimicrobial nanoparticles in their wound-healing abilities has been called into question119. The reputation of silver is further tarnished by widespread, unsupported claims of benefits of colloidal silver (which is regulated by the FDA as a dietary supplement) by social influencers and by companies marketing these products120,121. However, antimicrobial applications of silver have crept into a range of consumer applications, such as socks, deodorants and antibacterial coatings on products, such as refrigerators. By 2025, the annual global production of silver nanoparticles is estimated to reach 400–800 tonnes122, raising concerns over the long-term effects of environmental exposure123. In particular, resistance to Ag+ ions has been identified124,125. A study of 444 clinical isolates found no overt Ag+ resistance, but upon challenge with silver nitrate, over 50% of Enterobacter spp. and Klebsiella spp. (but not E. coli, P. aeruginosa, Acinetobacter spp., Citrobacter spp. or Proteus spp.) gained high levels of resistance (>128 mg l−1). Resistance appeared to be due to a single missense mutation in silS — a gene related to the expression of the sil operon that encodes efflux pumps (SilCBA and SilP) and Ag+ chaperone or binding proteins (SilF and SilE)125,126. Another study has shown that P. aeruginosa inactivates Ag+ by reduction to non-toxic Ag0 via the production of the redox-active metabolite, pyocyanin127. A 2022 genetics study found that silver nanoparticles did not speed up resistance mutation in E. coli and led to a reduction in the expression of quorum sensing molecules, but that resistance was acquired through two-component regulatory systems involved in processes such as metal detoxification, osmoregulation and energy metabolism128.

The exact mechanism by which silver compounds cause bacterial death has yet to be clearly defined. It is likely that several mechanisms are involved and that they vary subtly, depending on the form in which the silver is delivered. Four mechanisms have consistently been identified, as reviewed in detail in 2013 (ref. 109), 2016 (ref. 129) and more succinctly in 2020 (ref. 106). These four mechanisms involve: effects on the cell wall or membrane; interactions with DNA; binding or inhibition of enzymes and membrane proteins and the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). ROS is a somewhat controversial130–133 mechanism of bacterial killing that may directly result from exposure to multiple classes of antibiotics or may be a by-product of other antibiotic-induced effects134. Most of these mechanisms were identified in a 2013 study examining the effects of silver nitrate on E. coli115. An increased concentration of hydroxyl radicals was detected, indicating increased ROS that might result from Ag+ causing the release of Fe2+ from FeS clusters. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) revealed substantial morphological changes in the cell envelope, with an increase in membrane permeability supported by increased uptake of the membrane-impermeant dye propidium iodide. TEM also indicated protein aggregation, suggesting protein misfolding, which might arise from Ag+ replacing the hydrogen atom in cysteine thiol (–SH) side chain and disrupting disulfide bond formation. This study suggested that the misfolded proteins might lead to membrane permeability. Similar effects were observed in the 2019 study135 examining the effects of cationic silver nanoparticles on S. aureus. More specifically, scanning electron microscopy showed extensive damage to the bacterial cell membrane with gas chromatography–mass spectrometry analysis, indicating intracellular content leakage. Silver–protein interactions were indicated by enzymatic inhibition of respiratory chain dehydrogenase activity, and agarose gel electrophoresis revealed DNA degradation or inhibition of replication.

The binding of silver to proteins has been elucidated in a series of recent studies. In 2019, Wang et al.136 used liquid chromatography gel electrophoresis inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LC-GE-ICP-MS) to identify 34 proteins from E. coli that directly bind silver. Ag+ was found to initially damage several enzymes involved in glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid cycle, with subsequent damage to the adaptive glyoxylate pathway and suppression of the cellular responses to oxidative stress. Examination of Ag+ binding to one enzyme in the glycolysis pathway — glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase — revealed that Ag+ inhibited enzyme activity. Moreover, X-ray crystallography showed three bound Ag+ ions, one of which was bound to Cys at the catalytic site137. The same methodology was applied to S. aureus, with 38 silver-binding proteins identified138. Glycolysis was again the major pathway affected, leading to depleted ATP. Damage to the oxidative-stress defence system was also identified, which increased the concentration of ROS. A third affected pathway — the oxidative branch of the pentose phosphate pathway — includes the enzyme 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase. X-ray crystallography showed Ag+ binding with complexation with the catalytic His185 (ref. 138). Another X-ray study focusing on E. coli malate dehydrogenase indicated four Ag+ binding sites with a strong preference for Cys, but also including coordination to S, N and O from the side chains of Met, His and Lys, and the peptide backbone139. One specific protein interaction that has been identified is with urease, a nickel-dependent enzyme found in many organisms, including a number of pathogenic bacteria that use urease as a virulence factor to help colonization and survival. A crystal structure of Sporosarcina pasteurii urease showed that a cysteine thiol, a methionine thioether and a histidine imidazole ring coordinate a bimetallic cluster of Ag+ ions, which affects a protein loop near the active site, rather than the nickel-binding site itself140.

Genetics-based studies can provide insight into the mechanisms involved in bacterial resistance. One analysis in 2018 (ref. 141) used the Keio collection of 3,810 E. coli mutants, each with a deleted non-essential gene, to help decipher the pathways involved in silver sensitivity and resistance. Several mechanisms were identified following low but prolonged exposure to silver on solid minimal media, including genes involved in iron–sulfur clusters, cellular redox enzymes, cell-wall maintenance, quinone metabolism and sulfur assimilation. Similar studies have been conducted for other metals, as described subsequently.

Copper

Copper is another metal with historical antimicrobial use, with applications involving potential antimicrobial activity reported hundreds, if not thousands, of years ago142. More recently, copper-based paints are widely used to prevent fouling on the hulls of ships. Copper is also the only hard surface material that has been approved by the US Environmental Protection Agency to provide antimicrobial effects143. As highlighted in a previous review144, a promising biomedical application of copper is a CuZn-colloid-impregnated bandage, which showed greater reduction in S. aureus than a range of silver-based dressings. Similar mechanisms of action have been proposed for the two metals. Copper, similar to silver, has been tested in combination with antibiotics and has shown synergy with the antifungal agent gatifloxacin145 and the antitubercular drugs capreomycin146 and disulfiram147; for disulfiram, no other bivalent transition metals (for example, Fe2+, Ni2+, Mn2+ and Co2+) were effective. One study has shown that the bacterial toxicity of copper may be related to its effects on the stability of folded proteins — both increased and decreased — with proteins involved with the ribosome and protein biosynthesis, and cell-redox homeostasis particularly affected148. A 2021 study149 used the Keio collection of E. coli mutants (3,985 single deletions for this study compared with the one described earlier for silver) and compared the results with those previously reported for silver (discussed earlier) and gallium (discussed subsequently). Notably, distinct differences were seen, including variations in the genes involved in the same process, such as different subunits in transporters. CueO — a copper oxidase — was the only protein identified that was directly involved in copper homeostasis. The TolC efflux pump was shown to be important in mitigating copper sensitivity. The use of copper can lead to resistance, with horizontal transfer of genes encoding for copper resistance reported in S. aureus and Listeria monocytogenes150.

Other metals

Because the immune system uses zinc to kill bacteria, it is not surprising that studies have examined direct antibacterial applications of zinc151, particularly in the form of zinc oxide nanoparticles152. As with silver, it appears to be the release of Zn2+ from the nanoparticles that is responsible for its activity153. Antibacterial activity of other metals has also been reported9. For example, although much less commonly studied than silver, both gold154,155 and platinum156,157 nanoparticles can exhibit antibacterial properties; however, the effects of gold nanoparticles appear to be dependent on surface functionalization, which adds another layer of complexity to understanding their activity158.

Bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol), colloidal bismuth subcitrate (De-Nol) and ranitidine bismuth citrate (Pylorid) are used to treat Helicobacter pylori gastrointestinal infections. Antimicrobial activity for bismuth subgallate, bismuth subnitrate and colloidal bismuth tartrate has also been reported159. Despite being used for gastrointestinal infections since 1900, the structure of bismuth subsalicylate was only identified in 2022 (ref. 160). Colloidal bismuth subcitrate was also found to inhibit metallo-β-lactamase enzymes and restore the in vivo efficacy of meropenem161.

Antimicrobial properties of gallium also have longstanding recognition162,163, with a 1931 study showing gallium tartrate eliminating syphilis in rabbits and Trypanosoma evansi in mice164; gallium nitrate has been reported to have activity against a range of bacteria162, including P. aeruginosa, A. baumannii and Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and there is an FDA-approved formulation of gallium nitrate (that is, Ganite) for other indications. As mentioned earlier, the similarity of gallium to iron means that it can be taken up by metallophores; however, Ga3+ within iron-dependent enzymes cannot be reduced to Ga2+, which blocks enzyme activity. Application of genetic screening with the Keio collection of E. coli mutants found deletion of genes controlling oxidative stress, DNA or iron–sulfur cluster repair, or nucleotide biosynthesis led to increased sensitivity to gallium, whereas deletion of genes related to iron or siderophore import, amino acid biosynthesis and cell-wall maintenance led to reduced susceptibility165.

Metalloantibiotics

In contrast to freely solvated metal ions or metal nanoparticles, a metal complex is a well-defined arrangement of ligands (organic and/or inorganic) around one or more metal centres. These compounds stand out, as their properties can be manipulated in ways similar to those used in conventional drug development. This section discusses some features of metal complexes that differentiate them from purely organic drug candidates and highlights several concrete cases of promising metal complexes possessing antibacterial activity — metalloantibiotics.

Useful physicochemical properties

There is great diversity of properties among metals and near infinite possibilities and combinations of ligands. The number of ligands attached to a metal centre (that is, the coordination number) can range from as low as 1 to up to 28 (ref. 166). This range of coordination numbers leads to a rich and three-dimensionally diverse variety of structures of metal complexes (Fig. 3). In contrast, because carbon generally does not form more than four bonds, the geometrical diversity of organic molecules is lower. For example, a recent study by Cohen and co-workers167 compared the 3D structures of organic fragments used in fragment-based drug discovery with a small library of metallofragments (that is, fragments based on inert metal complexes). They evaluated the shape diversity of the compounds through analysis of the normalized principle moment of inertia. This analysis showed that the small library of 71 metal compounds covered a much larger portion of the available 3D fragment space than the 18,534 organic fragments from the ZINC database, which contains commercially available organic compounds and is therefore useful for virtual screening167. This metallofragment library was also shown to produce hits in a screening assay against viral, bacterial and human protein targets. Altogether, the rich structural variety of metal complexes makes them interesting and hitherto underexplored starting points for the development of lead molecules for challenging biological targets. This is of potential relevance in medicinal chemistry, in which the increasing predominance of achiral, aromatic compounds has led to calls to ‘escape from flatland’ (that is, to make compounds with structures that extend in all three dimensions), because the complexity and use of chiral centres correlate with higher target selectivity with reduced off-target effects, leading to greater success in transitioning from discovery, through clinical testing, to becoming drugs168,169.

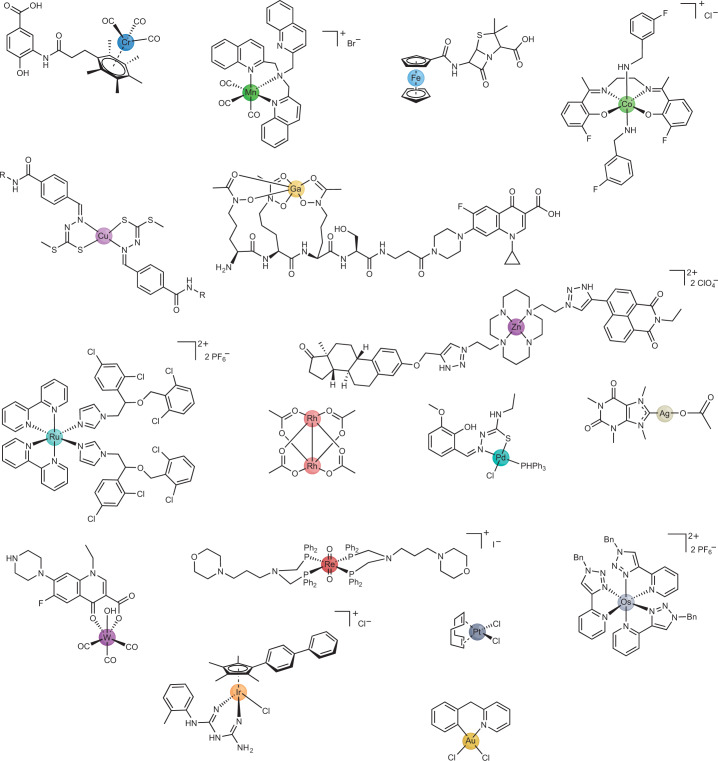

Fig. 3. Diversity in metals and structures accessible to metal complexes that have antibacterial activity.

The compounds shown contain chromium281, manganese176, iron282, cobalt283, copper284, zinc177, gallium90, ruthenium177, rhodium285, palladium286, silver287, tungsten288, rhenium289, osmium290, iridium291, platinum292 or gold293.

In addition to their diverse geometries, metal complexes also have access to a range of different mechanisms of action. These include: redox reactions; the generation of ROS or catalytic generation of other active species; ligand exchange or triggered ligand release and competitive or covalent inhibition of enzymes or binding to proteins. Many of these are difficult — if not impossible — to achieve with organic compounds. Some of these alternative modes of action against bacteria are discussed throughout later sections of this Review. For a comprehensive review of the mechanism of action accessible to metal complexes, the reader is referred to a recent review by Boros et al.170.

Antibacterial activity of metal complexes

The antibacterial properties of metal complexes were noted early in the history of modern inorganic medicinal chemistry. For example, the antibacterial properties of simple ruthenium complexes were reported in 1952 (ref. 171). The antiproliferative properties of platinum complexes that led to the development and approval of the anticancer drug cisplatin were first observed in E. coli bacteria in 1965 (ref. 172). Since those publications, there has been a slow but steady stream of reports on the antibacterial properties of metal complexes, with a marked increase in the past decade. However, the majority simply describe in vitro activity measurements against a few species of bacteria, without detailed investigation into their mechanism of action or their potential to be advanced as antibiotic drug candidates (for example, with toxicity and/or stability studies). In addition, very few metalloantibiotics have been evaluated in in vivo animal models173–176.

In 2020, we took advantage of the large number of metal complexes screened as part of the Community for Open Antimicrobial Drug Discovery (CO-ADD) Initiative and compared the ability of metal complexes to inhibit bacterial growth with that of purely organic molecules177. At the time, CO-ADD had screened over 295,000 compounds, including close to 1,000 metal-containing ones. Our analysis revealed that the metal-containing compounds had hit rates against critical ESKAPE pathogens that were more than 10 times higher than those of the rest of the molecules in the CO-ADD database. Importantly, we also compared the frequency of cytotoxicity (for mammalian cell lines) and haemolysis (for human red blood cells) of the two classes of compound and found no significant difference between the two classes for either toxicity measure. In addition to demonstrating the enormous potential of metal complexes as antimicrobial agents, this work provides evidence to refute the common perception that metal complexes are inherently more toxic than organic molecules.

With their potential as the next generation of antimicrobials established, it has become more important to understand how metal complexes are able to elicit their antibacterial effects. Unfortunately, the already small number of studies on metalloantibiotics decreases even further once one filters for those that investigate the mechanism of action of these compounds. In the following sections, we provide a curated selection of the most detailed studies to date on the mechanism of action of antibacterial metal complexes. We note that determining the mechanism of action of antibiotics is not trivial, particularly when more than one mechanism may be involved; for example, new mechanisms are still being proposed for polymyxin antibiotics, which were first used clinically in the 1950s (ref. 178).

Rhenium

One of the first detailed mechanism-of-action investigations for metalloantibiotics was undertaken by the groups of Bandow and Metzler-Nolte. They described the preparation of a trimetallic complex containing rhenium, iron and manganese with a peptide nucleic acid backbone (Re1; Fig. 4). This compound showed good activity against a range of Gram-positive bacteria including MRSA, vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus and Bacillus subtilis, but no activity against the tested Gram-negative pathogens179,180. In addition to in-depth mechanistic studies, a thorough investigation of the structure–activity relationship was carried out, which demonstrated that the Re-containing [(dpa)Re(CO)3] moiety was essential for activity, but the ferrocenyl and CpMn(CO)3 units could be replaced by non-metal moieties, such as a phenyl ring181.

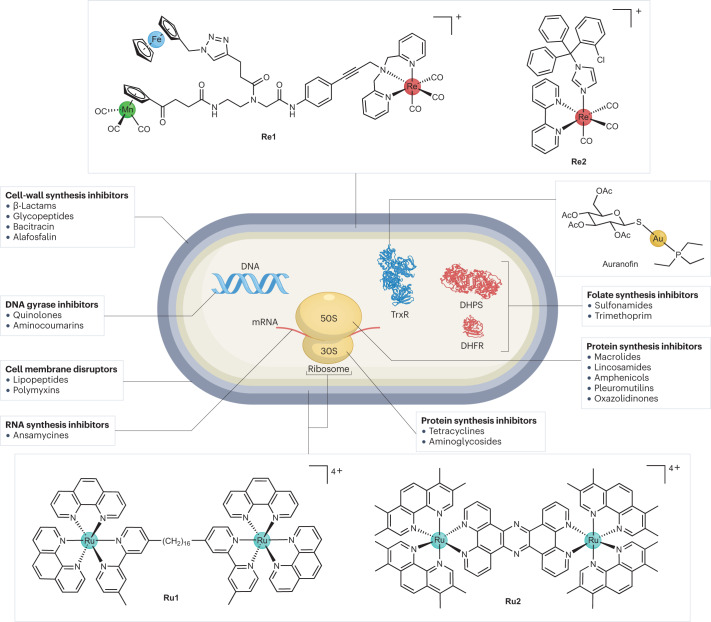

Fig. 4. Overview of the mechanisms of action of known antibiotics and metalloantibiotics.

Antibiotics can act by a number of different mechanisms. Unfortunately, there are relatively few metalloantibiotics for which the mechanism of action has been studied in detail. Illustrated here are the targets of compounds Re1, Re2, Ru1, Ru2 and auranofin. DHPS, dihydropteroate synthase; DHFR, dihydrofolate reductase; TrxR, thioredoxin reductase; mRNA, messenger RNA294.

Ferrocene fragments can generate ROS in biological systems through redox cycling. In the case of the antimalaria drug candidate ferroquine, this enhances its activity against resistant malaria strains182. To study the contribution of the ferrocene moiety to the antibacterial activity, an analogue containing ruthenocene, which does not undergo redox cycling, was synthesized and tested. The compound had similar activity against the S. aureus strains but lower activity against B. subtilis, indicating that the ferrocene moiety contributes only partially to the observed activity of the original compound Re1. Through systematic replacement of the metal-containing moieties in Re1 with simple organic functions, the authors demonstrated that the rhenium moiety of the compound was essential for the observed activity, whereas both ferrocene and manganese fragments could be replaced without appreciable loss of antibacterial activity.

Proteomic profiling was conducted with both Re1 and the ruthenocene-containing analogue, revealing similar general responses179. Several marker proteins for cell-envelope stress, energy or central metabolism and general stress response (for example, YceC, PspA and NadE) were upregulated for both compounds. Notably, oxidative-stress proteins were only upregulated for the ferrocene-containing Re1. Cellular assays revealed some ROS formation on treatment with Re1 but not with the ruthenium-containing analogue. However, the lack of antibacterial activity of the ferrocene-containing analogues of Re1 without the rhenium moiety indicates that ROS formation is not the main mechanism of this compound. Atomic absorption spectroscopy demonstrated accumulation of the metal compound in the membrane of treated bacteria. Monitoring of membrane-potential-dependent localization of the cell division protein MinD revealed that treatment Re1 led to membrane depolarization; however, further assays showed that the compound did not form large pores in the membrane (that is, the mechanism of some other membrane-active antibiotics). Monitoring of cytosolic ATP levels revealed that both Re1 and the ruthenocene analogue caused a significant reduction in relative ATP levels. However, this change did not correlate with the activity levels of the compounds, so it is not clear whether this is relevant to how they work. Overall, these assays provide a convincing case for the cytoplasmic membrane as a target structure of Re1, but the precise molecular target (targets) of the compound remains unknown at this stage.

The repeated occurrence of the M(CO)3 fragment (M = Mn (refs. 176,183–187), Re (refs. 174,175,188,189) and W (ref. 190)) in reported metalloantibiotics suggests that it has a crucial role in imparting the observed biological effects. In 2022, Mendes et al. investigated the structure–activity relationships of a series of manganese and rhenium tricarbonyl compounds, which, inspired by earlier work191, contained the antifungal drug clotrimazole as the axial ligand192. Most of the prepared compounds displayed some degree of activity against the Gram-positive S. aureus, but, in line with previous work on M(CO)3-type compounds, no significant activity against Gram-negative E. coli and S. enterica was observed (although a decrease in growth was noted for these strains). The structure of the bidentate ligand seemed to have an important effect on the activity of the complexes, with bulkier ligands resulting in reduced antibacterial activity. The analogous rhenium and manganese complexes without the clotrimazole axial ligand showed no effect against S. aureus. Clotrimazole alone was less active than the most active metal compounds, emphasizing that the combination of metal core and ligand was crucial for optimal activity.

In the aforementioned study192, the rhenium complex Re2 (Fig. 4) was selected for further mechanism-of-action studies because it had the highest activity, was stable in blood and did not release carbon monoxide. Bioreporter profiling in a specifically designed reference strain (B. subtilis 168) revealed that Re2 attacked the cytoplasmic membrane and potentially interfered with peptidoglycan synthesis. Studies with different fluorescent dyes excluded membrane depolarization and general impairment of the membrane barrier function as the mechanism of action of Re2. Analysis of cytoplasmic levels of UDP-N-acetylmuramic acid-pentapeptide — a soluble peptidoglycan precursor — revealed that the Re2 caused a strong increase of this precursor (no increase was caused by clotrimazole or the rhenium precursor), suggesting inhibition of peptidoglycan synthesis as a likely mechanism of action. Because UDP-N-acetylmuramic acid-pentapeptide is the last cytoplasmic peptidoglycan precursor, the authors focused on the later, membrane-associated, stages of the peptidoglycan biosynthesis. They found that Re2 showed moderate inhibition of lipid II formation in vitro. The use of individual, purified, recombinant enzymes of the metabolic cascade revealed that Re2 could inhibit the MurG-mediated conversion of lipid I to lipid II. Altogether, the evidence suggests that Re2 inhibits peptidoglycan synthesis by complexating lipid I, lipid II and undecaprenyl-pyrophosphate C55PP. However, the observation of dye aggregation upon exposure of bacteria to Re2 is not typical for peptidoglycan synthesis inhibitors, suggesting that there are additional targets for Re2. The amount of work described in this study illustrates the difficulty in readily ascertaining the real mechanism of action of novel compounds.

A liability of Re2 is its cytotoxicity against several human cell lines. However, Sovari et al.175 recently reported a series of new antimicrobial Re(CO)3 complexes with improved activity. Some of these showed no in vivo toxicity in zebrafish embryos and high efficacy (that is, reduced bacterial load and increased survival) in a zebrafish MRSA infection model.

Ruthenium

In parallel to the aforementioned studies into the rhenium carbonyl complexes as antimicrobials, several studies in the past decade have highlighted the promising antibacterial properties of ruthenium polypyridyl complexes. In particular, dinuclear ruthenium complexes are among the most intriguing classes of new metalloantibiotics173,193. In 2011, Collins and Keene194 reported the antimicrobial activity of inert oligonuclear polypyridylruthenium complexes. They found that dinuclear ruthenium complexes bearing phenanthroline ligands linked by long alkyl chains exhibited good activity (minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) as low as 1–8 µg ml−1; Box 1) against both Gram-positive (that is, S. aureus and MRSA) and Gram-negative (that is, E. coli and P. aeruginosa) bacteria. Analogous tri-nuclear and tetra-nuclear complexes195 and dinuclear compounds bearing a labile chloride ligand196 also exhibited antimicrobial properties, with the highest activity observed for the dinuclear complex with the longest bridging ligand197 (Ru1; Fig. 4). There was no statistically significant difference between the antibacterial activity of the ΔΔ-isomers and ΛΛ-isomers of Ru1, indicating that the mechanism of action does not involve specific interactions with chiral receptors, such as proteins. The authors observed some haemolysis for dinuclear compounds, which correlated with increasing chain length between the two metal centres (HC50 (concentration at which 50% haemolysis is observed) = 22 µg ml−1 = 13.5 µM for Ru1). A similar trend, albeit milder, was observed for cytotoxicity against THP-1 cells (CC50 (concentration causing 50% cell death) = 40 µg ml−1 = 25 µM for Ru1). Overall, these complexes resulted in therapeutic indices ranging between 10 and 100, depending on the bacterial strains and cell lines considered193.

Because of the inherent fluorescent properties of this class of compounds, their bacterial uptake can be determined by measuring the fluorescence remaining in the culture supernatant after removing the bacteria by centrifugation. It was shown that the bacterial uptake of these compounds correlated with their activity, with Ru1 showing the highest uptake across Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial strains (with generally lower uptake in Gram-negative bacteria)198. In other studies199,200, widefield fluorescence microscopy was used to investigate the intracellular localization of Ru1, revealing that the compound co-localized with bacterial ribosomes. Although ruthenium complexes with large, flat polypyridyl ligands are generally good intercalators for DNA, no significant interaction with DNA was observed199,200. These studies also suggested that the complex was able to condense the multiribosome assemblies known as polysomes, thereby stopping bacterial growth. Polysome chains are anionic and have a higher negative charge density than DNA. Therefore, they possess a higher affinity than DNA for polycationic species, such as Ru1. In eukaryotic cells, the ruthenium complex was found to accumulate in mitochondria. The authors hypothesized that the lower toxicity observed in these cells was owing to the ribosomes being membrane-associated, which could prevent the condensation triggered by Ru1 binding201.

Solid-state NMR and molecular dynamics simulations202 revealed that dinuclear ruthenium complexes with long linkers could be incorporated into negatively charged model bacterial membranes; however, with charge-neutral eukaryotic membranes, they only bound to the surface. This study found no evidence of bacterial membrane lytic activity, indicating that membrane insertion did not lead to pore formation. Instead, membrane insertion may contribute to the observed antibacterial activity in other ways, for example, by facilitating cellular uptake or leading to the disruption of other membrane-based processes.

In 2019, Thomas and co-workers described a different family of dinuclear ruthenium complexes, bridged by a (tetrapyrido[3,2-a:2′,3′-c:3′′,2′′-h:2′′′,3′′′-j]phenazine) polypyridyl ligand203 (Ru2; Fig. 4). These compounds were previously identified as excellent fluorescent probes for DNA, with good uptake into bacterial cells204. Compound Ru2 had high activity against Gram-negative bacteria, including a uropathogenic (EC958) E. coli strain. The activity was determined in two different types of media: glucose-defined minimal media and nutrient-rich Mueller–Hinton II media. Ru2 — like most other compounds tested — showed lower activity against EC958 in Mueller–Hinton II media (MIC = 1.6 µM) than the glucose-defined minimal media (MIC = 5.6 µM). The differential activity observed in different media demonstrates that the media type needs to be considered when evaluating and comparing reported in vitro assay results: bacteria are more resistant to killing when they are grown in a medium supporting their growth. Promisingly, the complex showed low cytotoxicity against human embryonic kidney-293 cells (IC50 = 135 µM), providing a higher therapeutic index than the alkyl-chain-linked ruthenium compounds described earlier. A study evaluating the ability for Ru2 to select for resistance against the EC958 strain via a 5-week serial passage assay revealed a fourfold to eightfold increase in the MIC of Ru2. However, this increase MIC was not stable, as when regrown in the absence of Ru2 and then retested, the same MIC as the wild-type strain was obtained. This suggests that the resistance was not caused by mutations, but by altered gene expression after extended exposure, which is reset upon growth in the absence of antibiotic pressure205. Toxicity testing in a Galleria mellonella larva showed that doses of Ru2 up to 80 mg kg−1 were not toxic203.

Cellular uptake of Ru2 was monitored using inductively coupled plasma-absorbance emission spectroscopy to determine the ruthenium levels in E. coli cells206. Some glucose dependency was observed in the uptake, indicating initial active (that is, energy-dependent) transport of the compound into the cells. The fluorescent properties of the compound were then used to conduct super-resolution microscopy, revealing that Ru2 initially accumulated in the bacterial membrane for up to 20 min, but then migrated to the cell poles. This finding coincides with the earlier work by the groups of Collins and Keene194 that identified localization with RNA-rich polysomes. Ru2 was also found to permeabilize the bacterial membrane, as indicated by uptake of a dye that is normally incapable of permeating the membranes of intact bacteria, ATP leakage assays and TEM.

In the subsequent work, Varney et al.205 conducted a transcriptomic analysis in the reference strain E. coli EC958 with Ru2. Nine target genes were monitored by quantitative PCR at different time points after exposure (ompF, spy, sdhA, yrbF, ycfR, ibpA, recN, recA and umuC). These genes were selected because they have functional roles in membrane permeability and stability and in DNA repair. The expression of three of the nine genes showed a significant difference in response to Ru2 exposure. The activity of the ompF gene, which encodes a non-specific porin in E. coli, decreased following exposure. However, there was no difference in the MIC for Ru2 treatment between knockout mutants with ompF and ompF-ompC deletions and the wild-type strain. This suggests that the attempt of bacteria at preventing the effect of Ru2 by reducing the expression of passive transport porins is ineffective. This is likely because the molecular weight limit of porins in E. coli (~600 Da)207 is exceeded by Ru2. A statistically significant increase in expression of the chaperone gene spy was observed. Spy and related chaperones are crucial to maintaining proper protein folding conditions under harsh conditions in bacteria. Lastly, a decrease in activity of the sdhA gene was detected after 2 h of exposure to Ru2. This gene encodes the succinate dehydrogenase flavoprotein subunit A, which is a key protein in the tricarboxylic acid cycle which is an important part of aerobic respiration. Genes involved in the aerobic respiration in E. coli have also been shown to be downregulated in other studies with ruthenium complexes208. After 2 h, uptake studies showed that Ru2 penetrated the membranes in E. coli. Downregulation of metabolic pathways may be a stress response by the bacteria to preserve energy. Overall, the detailed transcriptomic analysis paints a detailed picture of the action of Ru2, suggesting that the complex causes damage to both bacterial membranes in addition to previously mentioned activity on ribosomes.

In the studies described earlier, Ru2 showed better activity against Gram-negative bacteria than against the Gram-positive S. aureus. This was recently explored in more detail by Smitten et al.206. An extensive set of experiments led to the conclusion that teichoic acids, a common glycopolymer in the membrane of Gram-positive (but not Gram-negative) bacteria, bind Ru2, thereby preventing its accumulation inside Gram-positive bacteria. Three-dimensional stimulated emission depletion nanoscopy showed that Ru2 accumulated mostly at the cell wall and membrane of Gram-positive bacteria. Upregulation of mprF is an established resistance mechanism that leads to a higher overall positive charge of the outer surface of S. aureus, thereby reducing its susceptibility towards cationic antibiotics. Indeed, the activity of Ru2 was >25 higher against an mprF knockout mutant. On the basis of these findings, the authors speculated that the complex binds teichoic acids and other negatively charged cell-wall components in Gram-positive bacteria, preventing intracellular accumulation at concentrations necessary for optimal bacterial killing206. The extensive experiments required to come to these conclusions, which still do not provide a definitive mechanism of action, again highlight the difficulty and complexity in determining how novel antibiotics kill bacteria.

Mononuclear ruthenium complexes with antibacterial properties have also been reported173,193. Complexes based on tetrapyridophenazine and dipyridophenazine ligands were active against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, but, unlike the related dinuclear analogues, did not damage bacterial membranes, with no ATP release seen and with a minimal effect on membrane potential. The best compound was rapidly taken up in a glucose-independent manner, with imaging by super-resolution nanoscopy and TEM showing intracellular localization at the bacterial DNA, with co-localization with a DNA-targeting, fluorescent probe (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole)173. It remains to be seen whether there are any significant advantages or disadvantages in pursuing mononuclear or dinuclear complexes, with the more advanced studies to date concentrating on dinuclear examples.

The rhenium and ruthenium complexes discussed earlier are by far the metalloantibiotics that have been studied to the greatest extent. Future development needs to focus on optimizing the properties such as solubility, stability and cytotoxicity, while maintaining or improving the original antibacterial activity. More importantly, the efficacy and safety of these compounds need to be proven in in vivo models. Once a lead compound with favourable properties has demonstrated the ability to cure bacterial infections in vivo at a dose with a sufficient therapeutic index, the difficult road towards clinical application in patients (or potentially animals) can be approached.

Box 1 Methods for determining effectiveness of antimicrobial agents.

A number of methodologies are used to assess the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), which is conventionally reported as µg ml−1 or mg l−1 rather than in molarity, presumably because of the historical isolation of antibiotics as complex natural product mixtures. The MIC depends on factors that differ for each microorganism tested, such as the type of medium and plate; volume of the medium (that is, MIC can be performed as a microdilution or macrodilution); the quantity of the microorganism used initially (inoculum) and the length of incubation. The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI)301 and European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST)302 provide comprehensive guidelines for standardized testing.

The in vitro MIC required for an antibiotic is subjective and is directly linked to its toxicity and pharmacokinetic profile, as an antibiotic with an MIC of 16 µg ml−1 or higher may still be able to be developed as a drug if it is non-toxic at high concentrations and is able to achieve a high systemic concentration. Nevertheless, most approved antibiotics have MIC values around 1–2 µg ml−1 or less, so this is a rough benchmark for ‘good’ activity.

Broth dilution or broth microdilution MIC is the most common assay for MIC testing. These assays involve twofold serial dilutions of the tested compound in a broth medium containing an inoculum of the microorganism. Microdilution assays are conducted in a microtitre plate, with the plate incubated at 35 ± 2 °C for 16–24 h (longer for some yeasts and filamentous fungi). Microorganism growth is indicated by a cloudy solution, which can be visualized with the naked eye or quantified using optical density (for example, at 600 nm = OD600 for bacteria) in a spectrophotometer.

Another common assay is agar dilution. In agar dilution, the compound to be tested is combined with melted agar to produce plates with a twofold dilution series of the compound. The microorganism is added as a spot to each plate, using a defined inoculum. After incubation, visual examination determines the lowest concentration at which microorganism growth has occurred. This method allows for multiple types of microorganisms to be tested on one plate.

A less rigorous method to assess antimicrobial activity is the disc-diffusion assay. In this method, an agar plate is uniformly coated with an inoculum of microorganism, and a paper disc soaked with a solution of the test compound is placed on the surface. After incubation, the ‘zone of inhibition’ (any clear area around the disc where the bacteria have not grown enough to be visible) can be measured. However, the size of the zone does not necessarily correlate with relative antimicrobial potency, because it is also affected by the diffusion characteristics of a molecule.

Gold

The gold-based compound auranofin is an FDA-approved drug for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis that has recently been investigated for other applications, such as for the treatment of cancer and AIDS, as well as bacterial infections209. Auranofin is a potent inhibitor of thioredoxin reductase (TrxR) — a crucial enzyme that works in conjunction with glutathione and glutathione reductase to control the redox environment in the cell210. Loss of one of the two enzymes can generally be compensated by the other, and only knockout of both systems results in lethality. However, many Gram-positive bacteria (for example, S. aureus and certain Bacillus spp.), the Gram-negative H. pylori and the intermediate species M. tuberculosis lack the conventional glutathione–glutathione reductase couple, which is present in most Gram-negative species. Therefore, the thioredoxin–TrxR couple is often essential in these organisms. In recent work, auranofin was found to have activity against M. tuberculosis and a series of S. aureus and B. subtilis strains in vitro210, but did not possess significant activity against Gram-negative pathogens. In further assays, the authors demonstrated that auranofin inhibited the isolated TrxR enzymes of both M. tuberculosis and S. aureus and that the concentration of free thiols decreased substantially upon treatment of bacteria with auranofin. In addition, an E. coli mutant lacking glutathione displayed increased sensitivity towards auranofin, furthering the case that TrxR is the molecular target of the compound. Promisingly, auranofin maintained its antibacterial activity in an in vivo murine systemic infection model of S. aureus. Although the compound showed elevated cytotoxicity levels in vitro (HepG2 CC50 = 4.5 µM), the fact that it is FDA-approved with a safe profile even upon daily usage in patients highlights its potential as an antibacterial drug in the future. Several recent studies have explored other derivatives of auranofin with the goal of improving its activity profile and lowering its toxicity211–215.

Photoactivated metal complexes

In addition to being triggered by bacteria-internal stimuli, some classes of antimicrobial metal compounds can also be activated by external triggers such as light in photodynamic therapy (PDT). PDT requires two fundamental components: a light source and a photosensitizer. The photosensitizer absorbs photons from the light source and enters an excited state, from which it can then either directly react with its environment (for example, cellular components) and cause damage or transform surrounding molecules (such as oxygen and water) into ROS (Fig. 5). PDT has been widely used in cancer therapy, with several organic drugs receiving regulatory approval for clinical use216,217. In the past decade, metal-based photosensitizers have gained prominence because their photophysical and biological properties can be finely tuned218. Research in this area has culminated in one ruthenium complex being evaluated in a phase II clinical trial for the treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer219. Tumours are a suitable target for PDT because they are generally localized in one specific area where the light irradiation can be controlled with high spatial and temporal control. Although this is not applicable for systemic infections, antimicrobial PDT has been explored for the treatment of localized infections, such as those resulting from burn wounds, diabetic foot ulcers and skin and urinary tract infections220–222. For an overview on the latest progress in photosensitizer design in antimicrobial PDT, the reader is referred to a recent review223. A potential advantage of antimicrobial PDT is that it is a multifaceted attack against pathogens that is not limited to a singular molecular target. This increases the difficulty for bacteria to develop resistance to this treatment modality224.

Fig. 5. Mechanism of action of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy.

A metal photosensitizer (PS) is activated from its ground state to a singlet excited state upon light irradiation. Through intersystem crossing (ISC), an excited triplet state is reached, which can transfer either an electron to surrounding biological substrates (type 1 mechanism) or energy to surrounding oxygen (type 2 mechanism), generating a suite of reactive species that can kill nearby bacteria. Energy can also be dissipated through internal conversion (IC), fluorescence or phosphorescence. M, metal; ROS, reactive oxygen species; S or 1, singlet state; T or 3, triplet state; hν, photon energy, where h is Planck’s constant and ν is the frequency of light.

Porphyrins and related heterocyclic macrocycles have had major roles as photosensitizers in both anticancer and antibacterial PDT. Many groups have reported improved photophysical and biological properties for these molecules upon metal coordination; several example structures are shown in Fig. 6. Extensive reviews have been published elsewhere on this class of metal complexes225–227. Probably inspired by their success in anticancer PDT, ruthenium complexes have been among the most explored for this application228–233. In 2014, one of the first ruthenium photosensitizer agents was reported to show in vitro activity against S. aureus and E. coli, with a large reduction in colony-forming units upon light irradiation, but low activity in the dark234. Reports also exist for complexes containing iridium235–237, platinum238,239, copper240 and rhenium188,231 (Fig. 7).

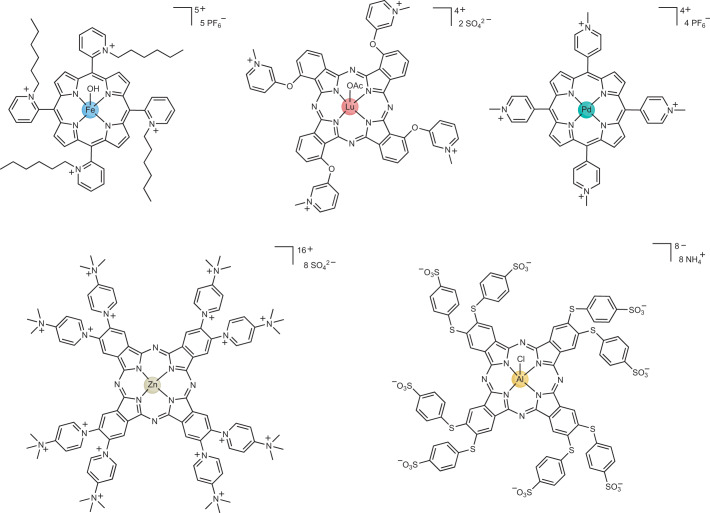

Fig. 6. Example structures of heterocyclic macrocycle metal photosensitizers.

The macrocyclic compounds, which are generally highly positively charged, can contain various different metals such as iron295, lutetium296, palladium297, zinc298 or aluminium299. Ac, acetate.

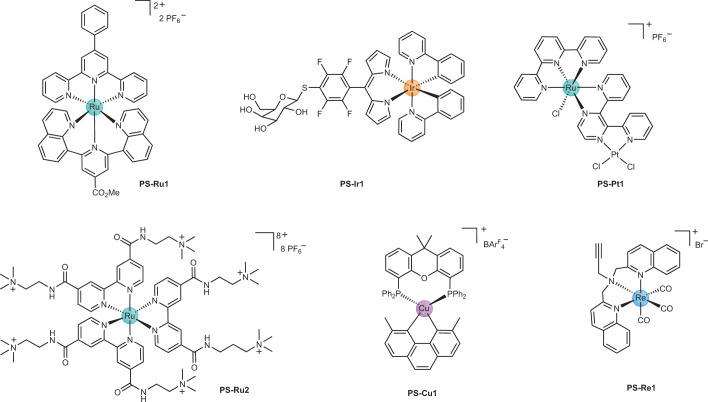

Fig. 7. Structures of metal photosensitizers reported to have antibacterial activity.

Various metals and ligand assemblies have the potential to be used as antibacterial photodynamic therapy agents. In general, aromatic conjugated ligands are used to fine-tune the photophysical properties of the resulting metal complex. Examples containing the metals ruthenium (PS-Ru1, ref. 234; PS-Ru2, ref. 300), iridium (PS-Ir1, ref. 235), platinum (PS-Pt1, refs. 238,239), copper (PS-Cu1, ref. 240) and rhenium (PS-Re1, ref. 188) have been reported. PS, photosensitizer; Ph, phenyl.

Light-mediated metal-based antibacterials are not limited to PDT mechanisms. In other studies, light has been used to trigger the release of ligands from metal complexes241–244. In this case, the free ligand acts as the antimicrobial agent and/or the unsaturated metal complex interacts and binds with cellular biomolecules, such as proteins and DNA. A notable class of light-activated ligand-releasing compounds is carbon monoxide releasing molecules (CORMs)245, which are effective at killing bacteria upon CO release. Both metal-based176,184,246–251 and organic252,253 antimicrobial CORMs have been reported. For example, tricarbonylchloro(glycinato)ruthenium(II) (CORM-3) inhibited the in vitro growth of P. aeruginosa at concentrations as low as 0.5 µM, displayed no cytotoxicity at 200 µM and increased the survival of mice to 100% in a P. aeruginosa peritonitis model 72 h after infection at 7.5 mg kg−1 (ref. 249). Additional studies examined the effects of closely related CORM-2 on P. aeruginosa biofilm disruption251 and of CORM-2 and CORM-3 on killing the gut pathogen H. pylori250. In the latter case, these molecules were found to directly kill H. pylori via inhibition of respiration and urease activity, but also acted as potentiators in combination with other antibiotics250.

Overall, the field of light-activated metal-based antimicrobials remains largely uncharted. Because the optical and biological properties of metal complexes can be fine-tuned through careful ligand design, this field has an exciting future.

Metal complexes for imaging infections

In addition to developing better antimicrobial therapies, there is also an urgent need to improve diagnosis to more rapidly select and monitor optimal treatment, which would reduce the unnecessary use of ineffective antibiotics and improve therapeutic outcomes. In many cases, infections are suspected to be present, but their location cannot be determined, which makes it challenging to prescribe the best therapy. There are currently no whole-body imaging techniques in clinical use that are capable of specifically identifying bacterial infections; the barriers to the development of such techniques are reviewed elsewhere254,255. Few bacterial-specific tracers have been tested in humans, with a 2019 review identifying 77 studies on preclinical and clinical imaging of bacterial infections with fluorescent tracers and radiopharmaceuticals256.

Imaging of bacterial infection has mainly been attempted using positron-emission tomography (PET) or single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) imaging, and many of the radioisotopes used in these techniques are metals. For example, infection imaging has been attempted with white blood cells and antibodies labelled with [67Ga], [99mTc] or [111In], with variable success in detecting prosthetic joint infections257–259. A [99mTc]-labelled version of ciprofloxacin was clinically approved for SPECT imaging but was later removed from the market because of a lack of differentiation between sterile inflammation and infection260, which is a common failure of infection imaging agents. The same antibiotic was also converted into a PET probe as [18F]-ciprofloxacin, which was also unsuccessful in humans, indicating that the antibiotic component, not the added [99mTc], was the likely cause of failure261. Other reported probes tested in humans include a [99mTc]-labelled cationic antimicrobial peptide (ubiquicidin, UB129-41)262, which has not advanced since the early 2000s (ref. 260), and a [68Ga]-NOTA-UBI peptide complex262.

There are, however, several encouraging preclinical research directions. Some earlier examples of metal-containing bacterial targeting moieties for imaging probes include a non-specifically labelled [99mTc]-vancomycin, which showed good discrimination between S. aureus infection and turpentine inflammation in rats263; a zinc-dipicolylamine complexed labelled with [111In] (refs. 264,265) and a range of bacteriophages that were conjugated with chelators and labelled with [99mTc] (ref. 259). More recently, the bacterial uptake of iron metallophores was combined with radioisotopes [67Ga] (SPECT) or [68Ga] (PET), relying on the similarity of coordination properties between Ga3+ and Fe3+ (ref. 266). In this study, natural metallophores from fungi (that is, triacetylfusarinine and ferrioxamine E) were converted into [68Ga]-triacetylfusarinine and [68Ga]-ferrioxamine E (Fig. 8A) and compared for imaging lung infections in Aspergillus fumigatus and S. aureus rat models: only the fungal infection was readily seen owing to the selective metallophore uptake. Similarly, the metallophore pyoverdine PAO1, which is produced by P. aeruginosa, was labelled with [68Ga] and showed very selective in vitro uptake by P. aeruginosa, allowing the detection of P. aeruginosa (but not E. coli or sterile inflammation) in intratracheal (rat) and thigh (mouse) infection models267 (Fig. 8B). In contrast, [68Ga]-citrate and [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose showed non-specific uptake in both the infection and sterile inflammation sites. In another example, desferrioxamine-B — a hydroxamate metallophore produced by Streptomyces pilosus — was also labelled with [68Ga] and showed more general uptake across P. aeruginosa, S. aureus and Streptococcus agalactiae than the PAO1 metallophore, but still not by E. coli, Candida albicans or K. pneumoniae268. This allowed P. aeruginosa and S. aureus thigh and P. aeruginosa lung infections to be visualized in mice (Fig. 8C).

Fig. 8. Metal complexes for imaging bacterial infections.

A, Structures of imaging agents. B, The structure of [68Ga]-PVD-PAO1 (Ba) and static PET–CT imaging of [68Ga]-PVD-PAO1 (Bb and Bc) compared with [68Ga]-citrate (Bd) and [18F]-FDG (Be) in a mouse muscle-infection model 45 min post-injection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in one thigh and Escherichia coli or sterile inflammation in the other thigh. C, The structure of [68Ga]-DFO-B (Ca) and static PET–CT imaging of [68Ga]-DFO-B in a mouse thigh-infection model 45 min post-injection with P. aeruginosa (Cb) or Staphylococcus aureus (Cc) (yellow arrows indicate site of infection). PET, positron-emission tomography; CT, computed tomography; PAI, P. aeruginosa infection; ECI, E. coli infection; SI, sterile inflammation; TAFC, triacetylfusarinine; FOXE, ferrioxamine E; PVD, pyoverdine; FDG, fluorodeoxyglucose; DFO-B, desferrioxamine-B; ID g−1, injected dose per gram of tissue; kBq ml−1, kilobecquerel per millilitre. Part B reprinted from ref. 267, under a Creative Commons licence CC-BY 4.0. Part C reprinted from ref. 268, under a Creative Commons licence CC-BY 4.0.

Other examples of leveraging metallophores for imaging include cyclen-based artificial bifunctional metallophores, which combine a 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic amide binding site for the gallium radionuclide and one or more catechol units to bind iron. These were able to discern (using PET) an E. coli infection in mice from lipopolysaccharide-triggered sterile inflammation88,269. However, the simpler monofunctional complex gave superior results. The galbofloxacin therapeutic described earlier, with a gallium-containing metallophore–ciprofloxacin conjugate, was converted into a radiolabelled probe by complexing [67Ga]90,91 (Fig. 8). The [67Ga]-galbofloxacin was used to determine bacterial uptake and to monitor biodistribution in mice, although imaging studies were not conducted. The complex showed superior discrimination to [67Ga]-citrate, which has been used clinically. However, it is not clear whether the additional complexity of adding additional components to the metallophore provides any advantages over just using the radiolabelled metallophore itself.

In summary, metal complexes show promise not only for treating bacterial infections but also in identifying them. Development as imaging agents may be a more rapid route to clinical use than therapeutic development, given the differing regulatory requirements for approval, and the trace quantities of the metal complex that are administered.

Conclusions and future directions

Over the past decade, there has been a surge of interest in identifying alternative ways to combat bacterial infections and to address the AMR health crisis. Many of the more-promising approaches involve metals as antimicrobial agents, either as free ions, in the form of nanoparticles or as metal complexes.

For free ions to exert their antibacterial effect, they need to reach the locus of the infection. In topical or local applications, this can be achieved by various delivery mechanisms, ranging from ion-loaded wound bandages to engineered gels that slowly release metal ions. For non-topical applications, the ion needs to be ‘packaged’ to be able to selectively reach the pathogenic bacteria. Here, the most promising approach is the use of metallophores, which hijack the bacterial transport systems to ensure intracellular delivery. A future direction could be the development of metallophores that strongly bind antibacterial metal ions but can release the ion when exposed to certain triggers, for example, light, pH or metabolites. Similar observations are valid for metal nanoparticles, which may find an easier road to application on topical, surface treatments or, for example, water disinfection. For systemic administration, more targeted systems will have to be developed.