Abstract

Objective:

Evaluate a computerized-based attention test in early infancy in predicting neurocognitive school-age performance in HIV-exposed uninfected children.

Method:

Thirty-eight Ugandan HIV-exposed/uninfected children (17 boys, 21 girls) were evaluated with the Early Childhood Vigilance Test (ECVT) of attention between 3–5 years of age, which is a 6-minute 44 second animation with colorful animals that greet the child and move across the screen. Attention was proportion of total animation time viewing computer screen, as well as proportion of time tracking the moving animal using eye tracking. These children were then again tested at least two years later (between 5 and 9 years of age) with the Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children, 2nd Edition (KABC-II) and the visual computerized Tests of Variables of Attention (TOVA).

Results:

Irrespective of whether scored by webcam video scoring or using automated eye tracking to compute proportion of time viewing the animation, ECVT attention was significantly correlated with all TOVA outcomes for vigilance attention. This was still the case when the correlation was adjusted for type of caregiver training for the mother, child gender, SES, and quality of HOME environment – especially for the TOVA response time variability to signal (p=0.03). None of the ECVT attention performance measures correlated significantly with any of the KABC-II cognitive ability outcomes.

Conclusion:

Attention assessment in early childhood is predictive of school-age computer-based measures of attention and can be used to gauge the effects of factors of early risk and resilience in brain/behavior development in African children affected by HIV.

Keywords: Attention, Cognition, Children, HIV, Africa

In a recent review of a variety of pediatric neurodevelopmental and neuropsychological assessments used in low and middle income countries (LMICs), the authors noted that many of the assessments adapted for use have not been well validated in these contexts (Semrud-Clikeman et al., 2016). Further, to administer these assessments in a valid manner, significant training and monitoring of the assessment personnel was necessary. Due to the complexities of assessment administration in resource-constrained settings, more consideration is being given to automated or computer-based assessments that can be readily adapted cross culturally.

One example of computer-based assessments is the Tests for Variables of Attention (TOVA), which is a computerized continuous performance test lasting about 20 minutes that tachistoscopically presents a smaller square within a larger square to which a child responds by quickly pressing a switch, depending on the position of the square (Greenberg, 1993). Because the TOVA does not depend on a given language or script and has proven clinically sensitive to a wide range of developmental disorders and disabilities, it has been a good candidate for evaluating attention and impulsivity in LMICs (Boivin & Giordani, 2009). The TOVA has been validated with children in LMICs to evaluate inattention and impulsivity in children 5 yrs of age and older in Laos (Boivin, Chounramany, Giordani, Xaisida, & Choulamountry, 1996) and Uganda (Bangirana, John, et al., 2009), and has proven sensitive to the persisting neuropsychological effects of cerebral malaria in Senegal (Boivin, 2002) and Uganda (Boivin et al., 2007; John et al., 2008).

However, in evaluating the neurodevelopmental and neuropsychological effects of infectious diseases such as malaria and HIV, it is important to have valid, sensitive, and reliable measures of attention in children who are too young to complete a test like TOVA (less than 5 yrs of age). The Early Childhood Vigilance Test (ECVT) is a computer-based, experimental measure of sustained attention that was designed to evaluate vigilance in preschool children.(Goldman, Shapiro, & Nelson, 2004; Zelinsky, Hughes, Rumsey, Jordan, & Shapiro, 1996). It is modeled after Ruff’s puppet vigilance paradigm (Ruff, Capozzoli, Dubiner, & Parrinello, 1990; Ruff & Capozzoli, 2003) only using lively and colorful animal-like figures which periodically appear in an animation cartoon to actively greet the child viewing the program. The ECVT has proven sensitive to the effects of severe malaria anemia and cerebral malaria in Ugandan children 2 to 5 years of age (Bangirana et al., 2014). With preschool severe malaria survivors in Uganda, the ECVT also correlated significantly with other more comprehensive performance-based measures of development, such as the Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL) (Bangirana et al., 2014; Boivin & Sikorskii, 2013). It has also been used to evaluate the benefits of early anti-retroviral treatment in Ugandan children living with HIV (Boivin et al., 2013) and among HIV-exposed/uninfected children (Boivin, Nakasujja, et al., 2017; Ikekwere et al., 2021), whose caregivers participated in a year-long biweekly training program to improve their daily interactions with their children so as to enhance their child’s development.

The purpose of the present study was to evaluate if preschool ECVT scores among HIV-exposed/uninfected children in Uganda predicted their performance several years later, at school-age, on two neuropsychological measures; the TOVA and the Kaufman Assessment Battery of Children, 2nd edition (KABC-II). In the present study, we hypothesize that the ECVT will correlate more strongly with TOVA performance at school age, since both are measures of vigilance attention. We propose that ECVT performance will correlate less well than KABC-II cognitive performance measures.

Method

Participants

IRB approval for this study was obtained from Michigan State University and Makerere University. Written informed consent was provided by the mothers of the study children after the consent form was explained to the mothers in their local language. Research permission was issued by the Ugandan National Council for Science and Technology. Participants were 38 children (17 boys, 21 girls) 5 to 9 years of age (mean [M]=7.88, standard deviation [SD]=0.98 yrs) perinatally exposed to HIV but uninfected (ELISA test) and cared for by the biological mother, staying within a 20 km catchment area of Tororo town. We were able to trace these 38 children for a follow-up assessment with TOVA and KABC-II, representing 86% of the 44 HIV-exposed/uninfected children were assessed about two years earlier (between 3 and 5 years of age) with the ECVT as part of a feasibility of eye tracking study (Boivin, Weiss, et al., 2017). These 44 children were originally part of a larger study; the Mediational Intervention for Sensitizing Caregivers (MISC) early childhood development (ECD) caregiver training cluster randomized controlled trial (cRCT) (Boivin, Nakasujja, et al., 2017) comparing biweekly yearlong MISC (N=24) versus a nutrition/health/hygiene curriculum (N=14). Only 44 children had ECVT data because they were the final participants (out of 200) scheduled for their 2-year post-enrollment assessment for the cRCT at the time when the ECVT was adapted, and pilot tested to eye tracking instrumentation at the study site.

Demographics:

child demographics were recorded at enrollment at pre-school age and included age, sex, and physical growth (weight, height, upper-arm circumference) (Boivin, Weiss, et al., 2017). Caregivers reported on their age, marital status (married/unmarried), education (any/none), and relationship to the study child (mother/other). A measure of socio-economic status (SES) was also acquired largely based on material possessions in the home and access to clean water, electricity, and type and quality of home dwelling (Table 1).

Table 1.

Child and caregiver characteristics and outcomes at time of school-age Tests of Variables of Attention (TOVA) and Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children, 2nd edition (KABC-II) assessment for Ugandan children HIV exposed but uninfected (HEU). Descriptive statistics are presented by caregiver training intervention trial arm.

| Characteristic | Mediational Intervention for Sensitizing Caregivers (MISC) N= 24 |

UCOBAC Health/Nutrition Curriculum (Treatment as Usual: TAU) N= 14 |

P-value for comparison by arm |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child Descriptive and Performance Measures | |||

| N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 13 (54%) | 4 (29%) | |

| Female | 11 (46%) | 10 (71%) | 0.13 |

| Mean (St Dev) | Mean (St Dev) | ||

| Age (yrs) at MISC/TAU initial enrollment | 2.50 (1.23) | 2.39 (0.97) | 0.77 |

| Age (yrs) at TOVA/KABC testing (>4 yrs after enrollment) | 7.82 (1.04) | 7.98 (0.87) | 0.64 |

| Time between ECVT and TOVA/KABC testing (yrs) | 1.72 (0.54) | 1.98 (0.67) | 0.20 |

| Home Observation Measurement of the Environment (HOME) | 24.09 (2.50) | 20.62 (5.09) | 0.009 |

| Child Cognitive Performance Measures at Preschool (ECVT) and at School Age (TOVA, KABC) | |||

| Early Childhood Vigilance Test (ECVT) preschool test of attention. 6.4-minute animation video viewing | |||

| ECVT % webcam PROCODER software observer scoring | 67.46 (18.17) | 71.15 (12.21) | 0.51 |

| ECVT % Tobii eye tracking of moving animals only | 57.62 (19.91) | 60.99 (15.31) | 0.59 |

| ECVT % Tobii eye tracking animation total score | 68.07 (22.19) | 73.16 (17.25) | 0.47 |

| Test of Variables of Attention (TOVA) school-age computerized test of attention and impulsivity | |||

| TOVA ADHD Index Score | −1.96 (2.49) | −1.56 (2.41) | 0.64 |

| TOVA Signal Detection D prime | 2.67 (0.85) | 2.93 (0.85) | 0.38 |

| TOVA % Omission Errors | 12.88 (12.95) | 13.27 (15.20) | 0.93 |

| TOVA % Commission Errors | 11.34 (10.95) | 7.56 (5.64) | 0.24 |

| TOVA response time variability (msec) | 253.83 (89.62) | 234.71 (62.18) | 0.49 |

| TOVA response time average (msec) | 653.42 (128.21) | 57.39 (10.94) | 0.90 |

| Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children (KABC) 2nd edition administered at school age | |||

| KABC Mental Processing Index (MPI) standard score | 63.63 (7.67) | 62.86 (8.39) | 0.78 |

| KABC Nonverbal Index (NVI) standard score | 63.79 (11.10) | 61.79 (10.65) | 0.59 |

| KABC Sequential Processing standard score | 73.13 (8.60) | 70.50 (8.58) | 0.94 |

| KABC Simultaneous Processing standard score | 70.83(9.98) | 72.50 (11.92) | 0.90 |

| KABC Learning standard score | 73.00 (11.40) | 68.43 (9.52) | 0.21 |

| KABC Delayed Recall standard score | 73.46 (12.50) | 68.00 (10.76) | 0.19 |

| KABC Planning (Reasoning) standard score | 62.53 (9.90) | 65.42 (9.57) | 0.43 |

Exclusion criteria were the same as in the cRCT, and included a medical history of serious birth complications, severe malnutrition, bacterial meningitis, encephalitis, cerebral malaria, or other known brain injury or disorder requiring hospitalization which could overshadow the developmental benefits of MISC caregiver training. A clinical medical officer performed a physical examination (to verify that the child was in good health and could proceed with neuropsychological assessments) along with the Ten Question Questionnaire (TQQ) with the principal caregiver to screen for neurodisabilities (Durkin, Davidson, & Desai, 2005; Durkin, Gottlieb, Maenner, Cappa, & Loaiza, 2008).

Measures

Home Observation for the Measurement of the Environment (HOME)

(Caldwell & Bradley, 1979) is a composite measure designed to assess the quality and quantity of stimulation that the child is exposed to in their home environment. The Infant/Toddler version, administered around the time of the ECVT assessment, includes 45 yes/no items. A total HOME score was generated by summing the number of ‘yes’ responses; higher HOME scores indicate higher quality interactions.

Early Childhood Vigilance Test (ECVT).

Developed for children 12- to 46-months of age, this measure evaluates how vigilance is used in very young children to evaluate sustained attention (Goldman et al., 2004; Zelinsky et al., 1996). Children are required to monitor a colorful computer screen for the sudden appearance of active and engaging cartoon animal characters that appear unpredictably at 5-to-15 second intervals. The ECVT involves a six minute and forty-four second cartoon in which a child watches an animated video, with animal characters moving across the screen for about 6 minutes of the total animation time. The more vigilant the children are in monitoring the screen, the more likely they are to be rewarded with cartoons engaging in lively movements when they appear for about 10 seconds.

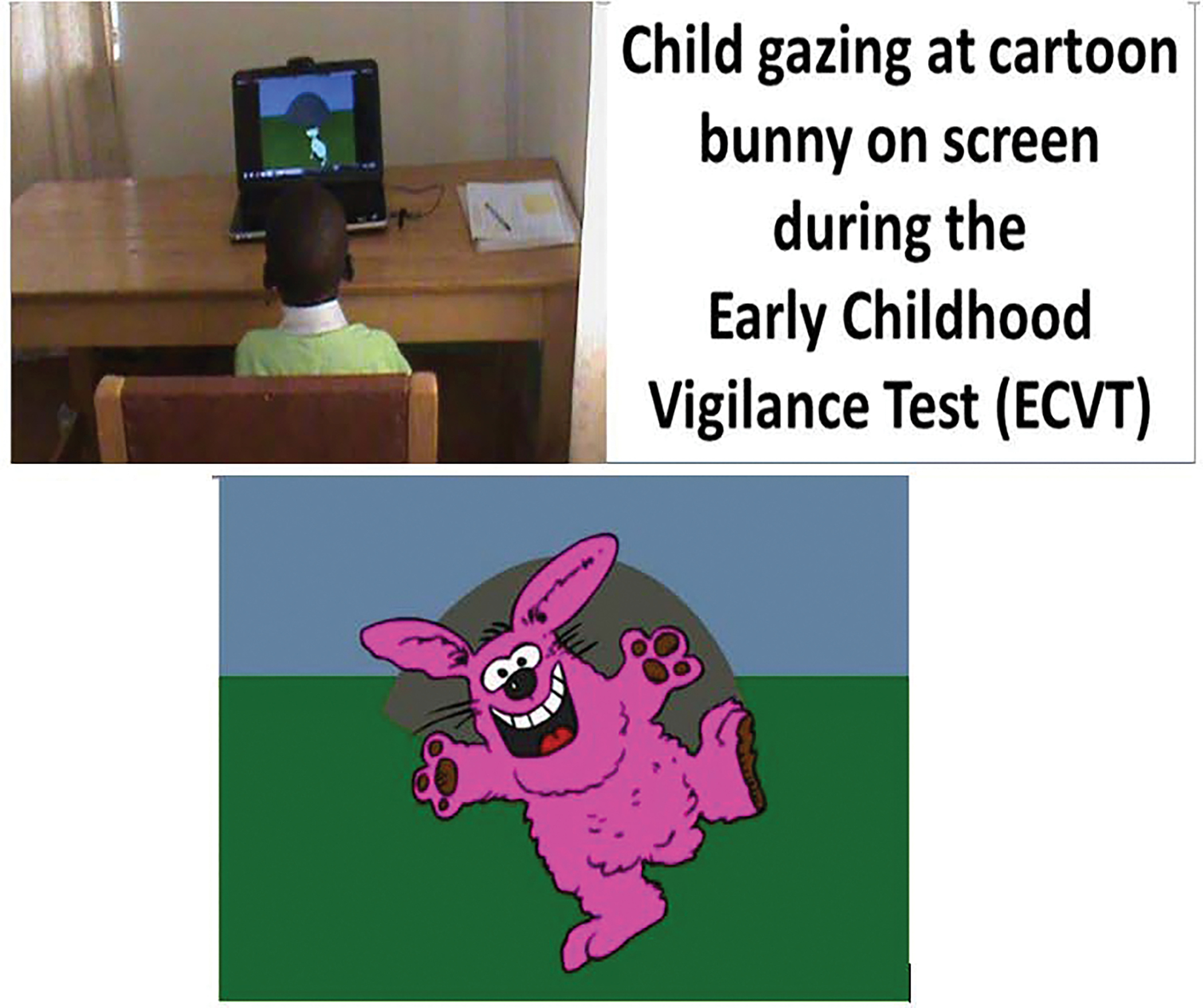

The child was videotaped with a webcam video placed above the computer monitor (see Figure 1). The videos were coded and scored by a trained researcher using a software program called PROCODER. Coding videos involved tracking the amount of time in seconds the child was looking at the screen and turning that amount into a percentage representing the amount of time spent attending to the screen out of the total time of the animation.

Figure 1.

These photographs show the screen viewing and seating arrangement for children in the present study viewing the Early Childhood Vigilance Test (ECVT) (Figure 1a), a six minute and 44 second cartoon animation test in which colorful and active animals would appear and would intermittently great the child (see pink bunny below; Figure 1b) to gain the child’s attention to the screen. The web cam is mounted at the top of the screen and the Tobii X2–300 infrared camera strip to record pupillary gaze for eye tracking is situated in a strip below the screen.

The other ECVT performance measures were obtained automatically using a Tobii X2–30 portable infrared camera calibrated to track eye gaze by means of pupillary direction. Studio Professional software was programmed with the Tobii X2–30 portable infrared camera to monitor the child’s pupil direction during the cartoon to automatically calculate the proportion of time the child gazed at the monitor screen during the entire animation presentation. The Tobii system was also programmed to measure the proportion of time watching the screen when colorful animals were moving across it.

Our principal measures in the present study were ECVT PROCODER scored webcam video measures of total time watching the screen during the animation, and ECVT Tobii eye tracking automated measures of proportion of time watching the screen during the animation. For the ECVT Tobii eye tracking, we also used a 2nd outcome measure, that of total proportion of time viewing that portion of the animation when animals were moving across the animation screen. (insert Figure 1 about here)

Test of Variables of Attention (TOVA).

TOVA is a computerized visual continuous performance test used in to screen, diagnose and monitor children and adults at risk for ADHD (Greenberg, 1993) and adapted for pediatric HIV research in Uganda (Chernoff et al., 2018). TOVA consists of the rapid (tachistoscopic) presentation of a large geometric square on the computer screen with a smaller dark box either in the upper position (signal) or lower position (non-signal). The child is asked to press a switch with the hand as fast as possible in response to the signal (measuring vigilance attention), but to withhold responding to the non-signal (measuring impulsivity). TOVA’s primary outcome variables are response time variability (a sensitive indication of inattention), response time, percent commission errors (impulsivity), percent omission errors (inattention), an attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) index score (missed signals in proportion to incorrect responses to non-signal), and a D prime signal detection measure of overall test performance (correct signal “hits” in proportion to correct non-responses to non-signal).

Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children (second edition).

The KABC-II is. A reliable and valid measure of cognitive abilities of children ranging from ages 3 to 18 years. It has been validated in the sub-Saharan African context,(Bangirana, Musisi, et al., 2009; Giordani et al., 1996; Jansen & Greenop, 2008; Ochieng, 2003) and previously adapted for use in pediatric HIV research in Uganda.(Ajayi et al., 2017; Boivin et al., 2008; Boivin, Nakasujja, Sikorskii, Opoka, & Giordani, 2016; Brahmbhatt et al., 2017; Giordani et al., 2015; Ruel et al., 2012; Wyhe, Water, Boivin, Cotton, & Thomas, 2017) Using the Luria model for neuropsychological assessment within the KABC-II, the primary outcome variables were the global scores of Sequential Processing (memory), Simultaneous Processing (visual-spatial processing and problem solving), Learning (immediate and delayed memory), Planning (executive reasoning), Delayed recall, nonverbal index (NVI) (subtests not dependent on the understanding of instructions in English) and Mental Processing Index (MPI) (a composite of the principal cognitive performance domains).

Statistical analysis:

Distributions of the principal measures of the developmental test at preschool (ECVT) and the school-age attention/impulsivity (TOVA) and cognitive performance across major neuropsychological domains (KABC-II) were evaluated for the present cohort of 38 HEU Ugandan children. Pearson correlations coefficients of ECVT measures with TOVA and KABC were computed. We also evaluated correlations of ECVT as measured with PROCODER video scoring software and Tobii eye tracking. The unadjusted associations between the ECVT Tobii eye tracking, ECVT PROCODER were also depicted using scatterplots.

Next, the adjusted analyses were performed using general linear models (GLM) that related school-age TOVA and KABC principal scores as outcomes (one at a time) to preschool ECVT attention proportion measures (one at a time), while adjusting for MISC/UCOBAC ECD intervention arm during the trial of which they were a part in early childhood, time between pre-school and school-age testing, socio-economic status, and HOME caregiving quality score. In the analysis of TOVA scores, age and sex were also included as covariates. Because the KABC-II scores are age- and sex- standardized, these factors were not included as covariates in the analysis of the KABC-II global performance outcomes. The coefficients for the ECVT measures, their standard errors, and p-values for the tests of significant differences of the coefficients from zero were derived from these GLMs. In addition, the effect size for the association between school-age measures and ECVT scores was estimated as partial eta-squared with the 95% confidence interval for the proportion of variation explained by the ECVT scores in the multivariable model. Eta-squared of 0.01 corresponds to small effect, 0.06 is medium, and 0.14 is a large effect size.

Transparency and openness statement.

We have reported how we determined our sample size, all data exclusions (if any), all manipulations, and all measures in the study, and which are described in further detail in a prior study (Boivin, Weiss, et al., 2017) and in the source clinical trial study (Boivin, Nakasujja, et al., 2017). All data, analysis code, and research materials are available upon request to the senior author (MJB) and contingent upon suitable intellectual property agreements with Michigan State University. Analyses were completed using SAS 9.4. This study’s design and its analysis were not pre-registered.

Results

Participants from two trial arms (MISC (N=24), UCOBAC (N=14), Table 1) were comparable on the socio-demographic and test performance measures, except for the HOME scores, which were improved by the MISC intervention in the trial (Boivin, Nakasujja, et al., 2017). The ECVT webcam PROCODER viewing proportion of the animated cartoon was highly correlated with the two different automated Tobii eye tracking measures of proportion of total animation time that the child’s gaze was directed to the computer screen where the 6 min 44 sec cartoon was being shown. The ECVT webcam proportion had a significant correlation with the corresponding eye-tracking measure, with an adjusted R2 of 0.5723 (p<0.001) between the two. We obtained an adjusted R2 of 0.8979 (p<0.0001) between the webcam overall animation view proportion and the automated eye tracking measures of overall animation viewing proportion measured only when the cartoon animals periodically appeared and actively moved across the screen in proportion to the total animation time. This measure specific to segments of the animation with moving animals across the screen could only be obtained with the eye tracking instrumentation and software, not with PROVODER scoring of the webcam.

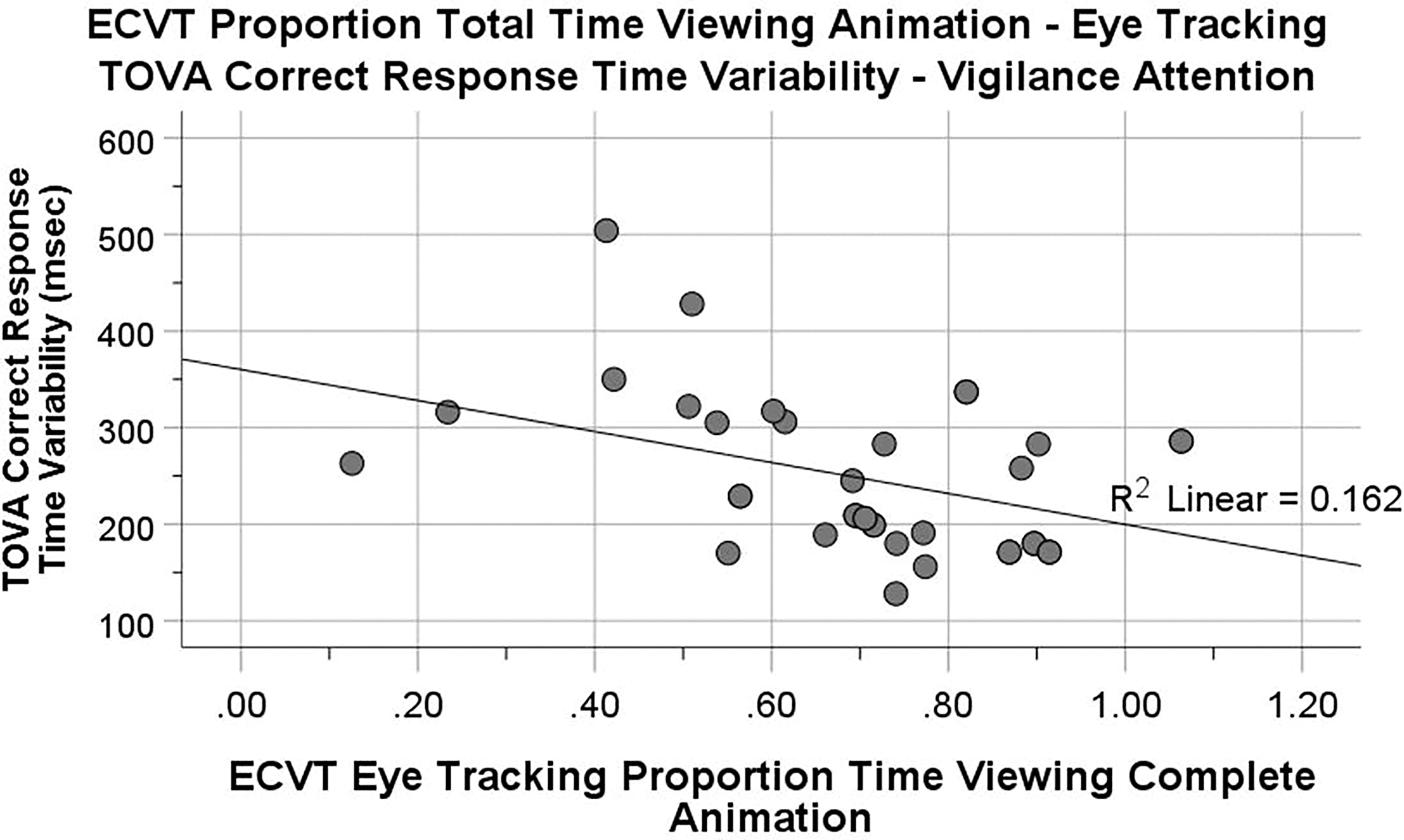

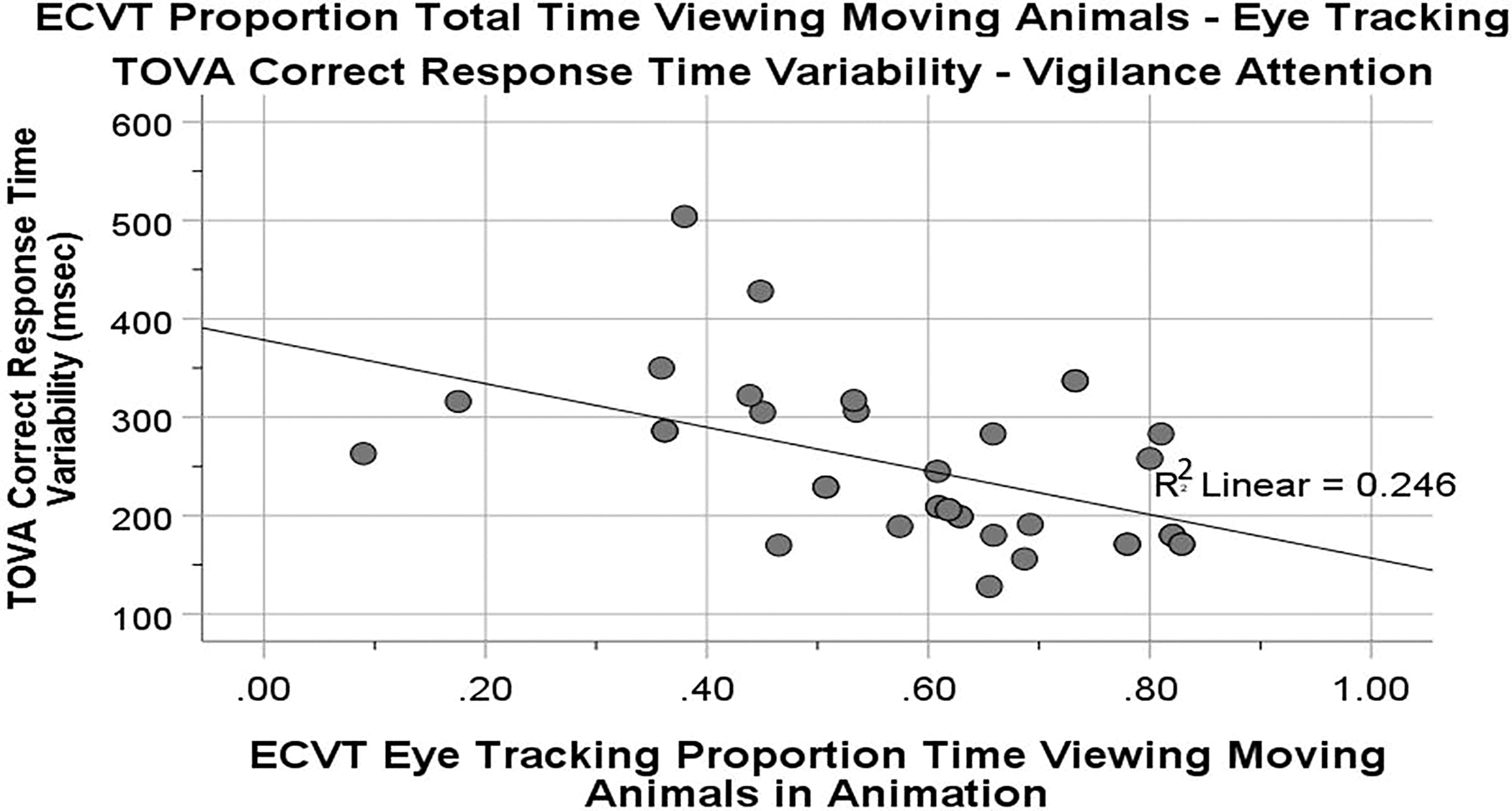

Figure 2 has an unadjusted scatterplot depicting the relationship between ECVT proportion of time viewing the cartoon animation based on the automated Tobii eye tracking recording (horizontal axis) and the TOVA response time variability of correct responses to signal presentation (RTV; vertical axis). This TOVA response time variability (RTV) to the signal is considered among the most sensitive to vigilance attention for this test. The adjusted relationship reveals a significant relationship between ECVT PROCODER webcam proportion of time viewing cartoon and the TOVA correct response time variability measure at school age (adjusted R2=0.3306, p<0.01). The unadjusted scatterplot in Figure 3 depicts the relationship between the automated ECVT Tobii eye tracking time viewing the animation screen when moving cartoon animals appeared, in proportion to the overall cartoon length, with the TOVA RTV measure at school age. The regression formula for the least-squares fit for the adjusted relationship is also statistically significant R2=0.2248, p<0.05). (Insert Figures 2 and 3 about here)

Figure 2.

This scatterplot depicts the automated ECVT Tobii eye tracking proportion of time viewing the entire cartoon (horizontal axis) and the TOVA correct response time variability (to signal) measure at school age in milliseconds (vertical axis). The dark line is the least squares fit for the scatterplot (unadjusted).

Figure 3.

This scatterplot depicts the automated ECVT Tobii eye tracking time viewing the animation screen when cartoon animals appeared in proportion to the overall cartoon length (horizontal axis); with the TOVA correct response time variability (to signal) measure at school age in milliseconds (vertical axis). The dark line is the least squares fit for the scatterplot (unadjusted).

We depicted these scatterplot relationships between the ECVT (preschool) and the TOVA RTV (school age) measures of vigilance attention because they were consistently the most significant amongst all our TOVA and KABC-II predicted outcomes as presented in Tables 2 (ECVT PROCODER webcam) and Table 3 (eye tracking moving animals). Adjusting for age at TOVA/KABC-II testing, socio-economic status (SES), gender, trial arm, and HOME score at the time of ECVT testing -- the ECVT webcam PROCODER proportion measure significantly predicts the TOVA ADHD index score (p<0.05), TOVA average correct response time to signal (p=0.0128), and the TOVA variability of correct response time (RTV) measure of attention (p=0.0061) (Table 2). ECVT was significantly correlated with all the TOVA performance outcomes for the unadjusted correlation coefficients (far right column) except for percent commission errors (a measure of impulsivity rather than inattention). ECVT did not predict any of the KABC-II global performance outcomes.

Table 2.

Prediction of school-age Tests of Variables of Attention (TOVA) and Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children, 2nd edition (KABC-II) principal performance outcomes in Ugandan HIV exposed/uninfected (HEU) children. The predictor measure is performance on the Early Childhood Vigilance Test (ECVT) proportion of time spent view animation (webcam scored with PROCODER software) several years prior as preschoolers. All general linear models included the adjustment for age at school-age testing, SES, gender, MISC intervention treatment arm, and Home Observational Measurement Evaluation (HOME) total quality of caregiving score.

| Tests of Variables of Attention (TOVA) and Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children (KABC) global performance measures | Early Childhood Vigilance Test (ECVT) coef. (SE) | Adjusted P-value for sig. ECVT | ECVT adjusted partial eta squared | Unadjusted correlation coefficient for ECVT | Unadjusted P-value for sig. ECVT correlation coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOVA ADHD Index score | 6.56 (4.50) | .0472 | 0.1290 | 0.38 | 0.0196 |

| TOVA percent omission errors | −16.66 (15.99) | .3060 | 0.0361 | −0.39 | 0.0162 |

| TOVA percent commission errors | 4.09 (10.19) | .6910 | 0.0055 | −0.30 | 0.0659 |

| TOVA correct resp. time (msec) | −339.18 (127.84) | .0128 | 0.1953 | −0.47 | 0.0032 |

| TOVA resp. time variability (msec) | −240.41 (81.30) | .0061 | 0.2317 | −0.58 | 0.0002 |

| TOVA Signal Detection D prime | 0.43 (0.91) | .6414 | 0.0076 | 0.43 | 0.0064 |

| KABC Mental Processing Index (MPI) Standardized total | 2.08 (9.79) | .8332 | 0.0015 | 0.02 | 0.0984 |

| KABC Learning Standardized total | −3.18 (13.28) | .8122 | 0.0018 | −0.06 | 0.7156 |

| KABC Planning Standardized total | 14.46 (15.82) | .3700 | 0.0336 | 0.11 | 0.5461 |

| KABC Sequential Processing total | 9.59 (10.45) | .3663 | 0.0264 | 0.13 | 0.4315 |

| KABC Simultaneous Processing Standardized total | 1.63 (12.87) | .9002 | 0.0005 | 0.06 | 0.7258 |

| KABC Delayed Recall Learning Standardized total | 10.35 (14.58) | .4830 | 0.0165 | 0.07 | 0.6716 |

| KABC Nonverbal Index Composite Standardized total | −8.24 (13.15) | .5311 | 0.0128 | −0.17 | 0.3145 |

P-value<.05 and medium or larger eta-squared ≥0.06 are bolded.

Table 3.

Prediction of school-age Tests of Variables of Attention (TOVA) and Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children, 2nd edition (KABC-II) principal performance outcomes in Ugandan HIV exposed/uninfected (HEU) children. The predictor measure is performance on the Early Childhood Vigilance Test (ECVT) proportion of time spent view animation (eye tracking) several years prior as preschoolers. All general linear models included the adjustment for age at school-age testing, SES, gender, MISC intervention treatment arm, and Home Observational Measurement Evaluation (HOME) total quality of caregiving score.

| Tests of Variables of Attention (TOVA) and Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children (KABC) global performance measures | Early Childhood Vigilance Test (ECVT) coef. (SE) | Adjusted P-value for sig. ECVT | ECVT adjusted partial eta squared | Unadjusted correlation coefficient for ECVT | Unadjusted P-value for sig. ECVT correlation coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOVA ADHD Index score | 4.76 (2.58) | .0760 | 0.1082 | 0.34 | 0.0380 |

| TOVA percent omission errors | −15.78 (12.65) | 0.2223 | 0.0149 | −0.33 | 0.0442 |

| TOVA percent commission errors | −5.47 (8.19) | 0.5097 | 0.0157 | −0.34 | 0.0373 |

| TOVA correct resp. time (msec) | −59.96 (110.10) | .5903 | 0.0105 | −0.15 | 0.3819 |

| TOVA resp. time variability (msec) | −151.96 (68.68) | .0352 | 0.1488 | −0.40 | 0.0134 |

| TOVA Signal Detection D prime | 1.30 (0.68) | .0695 | 0.0648 | 0.51 | 0.0013 |

| KABC Mental Processing Index (MPI) Standardized total | 2.45 (8.05) | 0.7626 | 0.0031 | 0.06 | 0.8904 |

| KABC Learning Standardized total | −3.85 (11.08) | 0.7307 | 0.0040 | −0.08 | 0.6543 |

| KABC Planning Standardized total | 3.14 (13.28) | 0.8155 | 0.0024 | 0.03 | 0.8827 |

| KABC Sequential Processing total | 8.34 (8.10) | 0.3113 | 0.0341 | 0.16 | 0.3416 |

| KABC Simultaneous Processing Standardized total | 12.15 (10.51) | 0.2568 | 0.0090 | 0.28 | 0.0960 |

| KABC Delayed Recall Learning Standardized total | 9.31 (12.05) | 0.4461 | 0.0202 | 0.10 | 0.5693 |

| KABC Nonverbal Index Composite Standardized total | −6.68 (10.94) | 0.5464 | 0.0123 | −0.10 | 0.5410 |

P-value<.05 and medium or larger eta-squared ≥0.06 are bolded.

The ECVT automated eye tracking overall proportion measure viewing animation screen was significantly correlated with the TOVA average correct response time to signal (p=0.0352). However, it was not significantly correlated with the TOVA ADHD index score (p=0.0760) or the TOVA RTV measure of attention (p=0.0695) (Table 3). Though not statistically significant, there was a moderate effect size for the adjusted measures (adjusted partial eta-squared = 0.1082 for TOVA ADHD index score; and 0.0648 for TOVA signal detection D prime), compared to a strong effect size for average correct response time to signal (adjusted partial eta-squared = 0.1488) (Table 3). Again, ECVT was significantly correlated with all the TOVA performance outcomes for the unadjusted correlation coefficients (bolded values in far-right column) except for average response time to signal. The ECVT eye tracking measures for proportion of total time viewing animation screen was not predictive of any of the KABC-II performance domains (Table 3).

The ECVT automated eye tracking proportion measured only when the cartoon animals appeared significantly predicted TOVA average response time to the signal (p<0.01) and TOVA response time variability (p<0.05) (Table 4). As with the ECVT webcam PROCODER proportion, ECVT was significantly correlated with all the TOVA performance outcomes for the unadjusted correlation coefficients except for percent commission errors. Again, for both Tables 3 and 4, none of the school-age KABC-II global outcomes were significantly predicted by the preschool ECVT eye tracking measure of vigilance attention.

Table 4.

Prediction of school-age Tests of Variables of Attention (TOVA) and Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children, 2nd edition (KABC-II) principal performance outcomes in Ugandan HIV exposed/uninfected (HEU) children. The predictor measure is performance on the Early Childhood Vigilance Test (ECVT) proportion of time spent view animation (eye tracking of moving animals) several years prior as preschoolers. All general linear models included the adjustment for age at school-age testing, SES, gender, MISC intervention treatment arm, and Home Observational Measurement Evaluation (HOME) total quality of caregiving score.

| Tests of Variables of Attention (TOVA) and Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children (KABC) global performance measures | Early Childhood Vigilance Test (ECVT) coef. (SE) | Adjusted P-value for sig. ECVT | ECVT adjusted partial eta squared | Unadjusted correlation coefficient for ECVT | Unadjusted P-value for sig. ECVT correlation coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOVA ADHD Index score | 4.37 (2.78) | 0.1275 | 0.0381 | 0.341 | 0.0196 |

| TOVA percent omission errors | −16.67 (13.42) | 0.2244 | 0.0522 | −0.38 | 0.0162 |

| TOVA percent commission errors | 9.71 (8.56) | 0.2664 | 0.0439 | −0.16 | 0.3426 |

| TOVA correct resp. time (msec) | −296.62 (103.13) | .0076 | 0.2280 | −0.50 | 0.0018 |

| TOVA resp. time variability (msec) | −164.01 (72.61) | 0.0319 | 0.1541 | −0.50 | 0.0018 |

| TOVA Signal Detection D prime | 0.04 (0.77) | 0.9618 | 0.0001 | 0.33 | 0.0473 |

| KABC Mental Processing Index (MPI) Standardized total | −3.23 (8.77) | 0.7156 | 0.0045 | 0.06 | 0.7348 |

| KABC Learning Standardized total | −3.94 (12.08) | 0.7468 | 0.0035 | −0.07 | 0.6796 |

| KABC Planning Standardized total | 10.23 (14.56) | 0.4984 | 0.0210 | 0.08 | 0.6877 |

| KABC Sequential Processing total | 1.60 (8.99) | 0.8600 | 0.0011 | 0.04 | 0.8192 |

| KABC Simultaneous Processing Standardized total | −9.70 (11.58) | 0.4090 | 0.0228 | −0.08 | 0.6276 |

| KABC Delayed Recall Learning Standardized total | 8.71 (13.35) | 0.5191 | 0.0145 | 0.07 | 0.6771 |

| KABC Nonverbal Index Composite Standardized total | 4.37 (2.78) | 0.1275 | 0.0381 | −0.21 | 0.2199 |

P-value<.05 and medium or larger eta-squared ≥0.06 are bolded.

For the above findings, we do have many analyses (3 key ECVT predictors times 13 TOVA and KABC-II performance outcomes = 39). Therefore, we do need to consider the possibility of an inflated risk of Type 1 error, such as controlling for family-wise error (e.g., for all analyses involving the TOVA for a given predictor). Based on the Hochberg adjustment for the false discovery rate for each of 3 predictors separately, only TOVA correct response time versus webcam (Table 2) and versus time spent viewing animation (eye tracking, Table 4) remained significant. However, due to the pilot nature of this study, the adjustment for the false discovery rate was not planned. Future research is needed to evaluate whether findings from this pilot study hold in larger samples.

Discussion

Results presented here extend earlier findings (Boivin, Weiss, et al., 2017) in documenting that the ECVT as a measure of attention in preschoolers (both webcam PROCODER and Tobii eye tracking performance measures) was predictive of a school-age computer-based measure of attention in these same children. However, the ECVT was not predictive of the cognitive performance domains assessed by the KABC-II (e.g., working memory, learning, visual-spatial processing, planning). In previously published research with Ugandan HEU children in the same study setting as for the present study, ECVT measures of attention were correlated with the MSEL, the Color-Object Association Test (COAT), and Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function for preschool children (BRIEF-P; administered to the principal caregiver of the child) (Boivin, Weiss, et al., 2017). These assessments were all done during the same assessment session, so that concurrent validity could be evaluated for this cohort of children. Although the ECVT attention measures significantly correlated with COAT immediate recall and total recall measures of object placement learning, ECVT performance did not correlated with MSEL composite cognitive performance. This is consistent with the present findings. ECVT performance also did not correlate significantly with caregiver rating of the child on the BRIEF-P global executive composite.

The executive ability of attention in early childhood most certainly is foundational to the kind of global cognitive ability domains encompassed in the KABC-II at school age (Boivin & Giordani, 2009). However, ECVT performance in early childhood perhaps measures only a specific dimension of vigilance attention that is predictively overshadowed by other foundational domains (e.g., working memory, learning, visual-spatial analysis, problem solving, and planning/reasoning). Although made possible by attention, this domain is not directly measured by the KABC-II mental processing index of global cognitive ability when assessed at school age (Kaufman & Kaufman, 2004), Which in this study took place years after the ECVT evaluation. That is why Boivin and colleagues typically include the TOVA along with the KABC-II when evaluating the brain/behavior integrity of African children in a culture-fair manner (Boivin & Giordani, 2009).

Developmental measures of cognitive development in early childhood, on the other hand, that do encompass working memory, learning, visual-spatial analysis, and reasoning/planning (e.g., the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID)) will likely be predictive of global cognitive performance on the KABC-II years later at school age (Torras-Mana, Gomez-Morales, Gonzalez-Gimeno, Fornieles-Deu, & Brun-Gasca, 2016). To illustrate, Boivin and colleagues used the Malawi Developmental Assessment Tool (MDAT) to evaluate severe malaria survivors and their non-malarial controls longitudinally from preschool to school-age. The MDAT is an early childhood development test validated for Malawian children (Gladstone et al., 2010), and was used in this study to significantly predict KABC-II performance when these children reached school age (Boivin et al., 2019). Boivin and colleagues obtained similar findings using the MSEL (western-based test) in predicting KABC-II performance in at-risk but non-CM surviving children in Benin (Boivin et al., 2021). The MSEL cognitive composite standardized score was significantly correlated with the KABC-II MPI (with moderate effect sizes), but not with TOVA performance of vigilance attention and impulsivity).

The predictive validity measures for the TOVA were comparable whether we used the more labor-intensive ECVT webcam based PROCODER scoring by a human observer, or the Tobii eye tracking with its automated measures. As mentioned previously, the advantage of the eye tracking measures is that they can provide immediate results for the ECVT test, as opposed to the need for PROCODER webcam scoring later by well-trained observers. Webcam PROCODER-based ECVT measures also requires inter-observer reliability evaluation for a given sample set by multiple observers, whereas Tobii-based eye tracking measures just require consistent and careful calibration by the eye-tracking instrumentation (infrared camera mounted below the laptop animation screen (Figure 1). Perhaps the main challenge limiting the scalability of eye-tracking instrumentation is the lack of user-friendly solutions for automating video data analysis. Current available software requires manually tagging eye movement data, a process involving specific training and that can be time-consuming.

We used the ECVT test of attention as one of the neurocognitive assessments to evaluate the efficacy of the ECD interventions implemented to improve caregiving. Although eye tracking technology has been used to assess cognitive function in children (Forssman et al., 2017), we are the first to implement its use for neurodevelopmental assessment in African children affected with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa (Boivin, Weiss, et al., 2017; Chhaya et al., 2018). Our principal accomplishment for this study was establishing the utility of an eye-tracking based vigilance attention test in Ugandan preschoolers for predicting computer-based measures of attention in these same children at school-age. Our prior work established that eye tracking ECVT measures of attention correlate with other visual-spatial measures of working memory and learning (e.g., Color-Object Association Test (COAT) and portion of the Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL)) (Boivin, Weiss, et al., 2017). The predictive validation of the ECVT measure of vigilance attention in the present study provides a potentially automated and viable means of monitoring neuropsychological development in children perinatally exposed to HIV, cared for by mothers living with HIV in resource-constrained settings.

By establishing the predictive validity of such eye-tracking based measures as the ECVT in measuring attention in early childhood, we expand the pool of viable longitudinal neuropsychological assessment throughout early and middle childhood. Such an performance-based assessment program for developmental integrity of brain/behavior function can gauge the long-term benefits of early medical and behavioral interventions with neurologically at risk children, such as with severe malaria, HIV, and other CNS infections such as COVID (Boivin, Ruisenor-Escudero, & Familiar-Lopez, 2016).

Finally, validating a performance-based longitudinal assessment program for developmental integrity with predictive validity across the developmental life span can have very important implications for the science of child development. We propose that the valid application of western-based assessments like the. KABC-II with at-risk sub-Saharan children would support that such assessments can capture and characterize neurocognitive function in children, including vigilance attention.

It should not be taken as a given that a Western-based cognitive performance test measures the same constructs across cultural settings, as has been considered by other child development assessment specialists working in the sub-Saharan African setting (Holding et al., 2016). Future work with the ECVT as it predicts such school-age attention measures as the TOVA should establish the invariance of the constructs across cultural settings. The sample size in this study was small, which was perhaps our biggest study limitation. In future work, we need to employ much larger samples collected across very different LMICs for cross-cultural comparison (Kitsao-Wekulo et al., 2013). Similarly, we did not include a comparison group of unexposed, uninfected children.

In conclusion, we empirically evaluated an important issue in the adaptation of both experimental (eye tracking with the ECVT) and Western-based assessments (e.g., KABC-II and TOVA) for African children. That is, whether Western-based neurodevelopmental and subsequent neuropsychological tests adapted to the Ugandan rural context as embedded within an ECD cRCT intervention study can have predictive correlations. Performance on an animation cartoon attention test was predictive of school-age performance on a computerized test of vigilance attention administered several years later, but not of overall cognitive ability as measured by a comprehensive battery of cognitive ability neuropsychological tests. These are important findings because this is the first report that an automated measure of attention using eye tracking is predictive of measures of cognitive performance several years later with at-risk African children. Our next steps are now to evaluate other automated measures of neurocognition based on eye tracking in very early childhood in terms of their predictive sensitivity of cognitive performance domains at school-age. Such measures will be of real benefit to the field of neuropsychology in the global health context.

Our proposed eye-tracking neurocognitive performance measures that are feasible with very young children have potentially high impact in our present clinical settings. This is because such measures can prove viable and sensitive in gauging brain/behavior integrity and its developmental trajectory in response to early beneficial interventions. If such early neurocognitive measures are predictive of neuropsychological performance at school age, they can be used together in a longitudinal manner throughout the developmental life span. Such measures could be used to provide evidence for documenting the benefits of both medical and behavioral interventions in response to predominant risk factors in those settings, keeping children from achieving their full potential in life.

Key points.

Question: Is performance on a computer-based test of attention using eye-tracking to an animated cartoon in early childhood, predictive of neurocognitive performance on different tests at school-age in a cohort of Ugandan HIV-exposed/uninfected children?

Findings: Performance on an animation cartoon attention test was predictive of school-age performance on a computerized test of vigilance attention administered several years later, but not of overall cognitive ability as measured by a comprehensive battery of cognitive ability neuropsychological tests.

Importance: This is the first time that an automated measure of attention using eye tracking instrumentation has been demonstrated to be predictive of measures of cognitive performance several years later with at-risk African children.

Next Steps: To evaluate other automated measures of neurocognition based on eye tracking in very early childhood, to gauge brain/behavior integrity and its developmental trajectory in a longitudinal manner throughout early and middle childhood.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge funding National Institutes of Health grant RO1 HD070723 (Michael J. Boivin and Alla Sikorskii), funding from the Michigan State University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Department of Psychiatry, and the Department of Neurology & Ophthalmology (Itziar Familiar and Michael J. Boivin), and funding from the Michigan State University College of Human Medicine (Ronak Chhaya and Jonathan Weiss) and the University of Michigan School of Public Health (Victoria Seffren).

Footnotes

We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Ajayi OR, Matthews G, Taylor M, Kvalsvig J, Davidson LL, Kauchali S, & Mellins CA (2017). Factors associated with the health and cognition of 6-year-old to 8-year-old children in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Trop Med Int Health, 22(5), 631–637. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangirana P, John CC, Idro R, Opoka RO, Byarugaba J, Jurek AM, & Boivin, (2009). Socioeconomic predictors of cognition in Ugandan children: Implications for community based interventions. PLoS One, 4(11), e7898. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangirana P, Musisi S, Allebeck P, Giordani B, John CC, Opoka RO, . . . Boivin, (2009). A preliminary investigation of the construct validity of the KABC-II in Ugandan children with prior cerebral insult. African Health Sciences, 9(3), 186–192. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangirana P, Opoka RO, Boivin J, Idro R, Hodges JS, Romero RA, . . . John CC (2014). Severe Malarial Anemia is Associated With Long-term Neurocognitive Impairment. Clin Infect Dis, 59(3), 336–344. doi:ciu293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin M, & Sikorskii A (2013). The correspondence between early andmiddle childhood neurodevelopmental assessments in Malawian and Ugandan children. Retrieved from London, UK: [Google Scholar]

- Boivin, (2002). Effects of early cerebral malaria on cognitive ability in Senegalese children. J Dev Behav Pediatr, 23(5), 353–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin J, Bangirana P, Byarugaba J, Opoka RO, Idro R, Jurek AM, & John CC (2007). Cognitive impairment after cerebral malaria in children: a prospective study. Pediatrics, 119(2), e360–366. doi:peds.2006–2027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin J, Bangirana P, Nakasujja N, Page CF, Shohet C, Givon D, . . . Klein PS (2013). A year-long caregiver training program improves cognition in preschool Ugandan children with human immunodeficiency virus. J Pediatr, 163(5), 1409–1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin J, Bangirana P, Tomac R, Parikh S, Opoka RO, Nakasujja N, . . . Giordani B (2008). Neuropsychological benefits of computerized cognitive rehabilitation training in Ugandan children surviving cerebral malaria and children with HIV. BMC Proceedings, 2(Suppl 1), P7. [Google Scholar]

- Boivin J, Chounramany C, Giordani B, Xaisida S, & Choulamountry L (1996). Validating a cognitive ability testing protocol with Lao children for community development applications. Neuropsychology, 10(4), 588–599. [Google Scholar]

- Boivin J, & Giordani B (2009). Neuropsychological assessment of African children: evidence for a universal basis to cognitive ability. In Chiao JY (Ed.), Cultural Neuroscience: Cultural Influences on Brain Function. (Vol. 178, pp. 113–135). New York, NY: Elsevier Publications. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin J, Mohanty A, Sikorskii A, Vokhiwa M, Magen JG, & Gladstone,(2019). Early and middle childhood developmental, cognitive, and psychiatric outcomes of Malawian children affected by retinopathy positive cerebral malaria. Child Neuropsychol, 25(1), 81–102. doi: 10.1080/09297049.2018.1451497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin J, Nakasujja N, Familiar-Lopez I, Murray SM, Sikorskii A, Awadu J, . . . Bass JK (2017). Effect of Caregiver Training on the Neurodevelopment of HIV-Exposed Uninfected Children and Caregiver Mental Health: A Ugandan Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. J Dev Behav Pediatr, 38(9), 753–764. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin J, Nakasujja N, Sikorskii A, Opoka RO, & Giordani B (2016). A Randomized Controlled Trial to Evaluate if Computerized Cognitive Rehabilitation Improves Neurocognition in Ugandan Children with HIV. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses, 32(8), 743–755. doi: 10.1089/AID.2016.0026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin J, Ruisenor-Escudero H, & Familiar-Lopez I (2016). CNS impact of perinatal HIV infection and early treatment: the need for behavioral rehabilitative interventions along with medical treatment and care. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep, 13(6), 318–327. doi: 10.1007/s11904-016-0342-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin J, Weiss J, Chhaya R, Seffren V, Awadu J, Sikorskii A, & Giordani B (2017). The feasibility of automated eye tracking with the Early Childhood Vigilance Test of attention in younger HIV-exposed Ugandan children. Neuropsychology, 31(5), 525–534. doi: 10.1037/neu0000382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin J, Zoumenou R, Sikorskii A, Fievet N, Alao J, Davidson L, . . . Bodeau-Livinec F (2021). [Formula: see text]Neurodevelopmental assessment at one year of age predicts neuropsychological performance at six years in a cohort of West African Children. Child Neuropsychol, 27(4), 548–571. doi: 10.1080/09297049.2021.1876012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brahmbhatt H, Boivin M, Ssempijja V, Kagaayi J, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, . . . Gray RH (2017). Impact of HIV and Atiretroviral Therapy on Neurocognitive Outcomes Among School-Aged Children. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 75(1), 1–8. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell BM, & Bradley RH (1979). Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment. Little Rock, AR: University of Arkansas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chernoff C, Laughton B, Ratswana M, Familiar I, Fairlie L, Vhembo T, . . . Boivin, (2018). Validity of Neuropsychological Testing in Young African Children Affected by HIV. J Pediatr Infect Dis, 13(3), 185–201. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1637020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chhaya R, Weiss J, Seffren V, Sikorskii A, Winke PM, Ojuka JC, & Boivin, (2018). The feasibility of an automated eye-tracking-modified Fagan test of memory for human faces in younger Ugandan HIV-exposed children. Child Neuropsychol, 24(5), 686–701. doi: 10.1080/09297049.2017.1329412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durkin S, Davidson LL, & Desai P (2005). Validity of the ten-question screen for childhood disability: results from population based studies in Bangladesh, Jamaica and Pakistan. Epidemiology, 5, 283–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durkin S, Gottlieb CA, Maenner J, Cappa C, & Loaiza E (2008). Monitoring child disability in developing countries: results from the Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys. Retrieved from New York: [Google Scholar]

- Forssman L, Ashorn P, Ashorn U, Maleta K, Matchado A, Kortekangas E, & Leppanen J(2017). Eye-tracking-based assessment of cognitive function in low-resource settings. Arch Dis Child, 102(4), 301–302. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2016-310525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordani B, Boivin J, Opel B, Dia Nseyila D, Diawaku N, & Lauer RE (1996). Use of the K-ABC with children in Zaire, Africa: An evaluation of the sequential-simultaneous processing distinction within an intercultural context. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 43(1), 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- Giordani B, Novak B, Sikorskii A, Bangirana P, Nakasujja N, Winn BW, & Boivin, (2015). Designing and evaluating Brain Powered Games for cognitive training and rehabilitation in at-risk African children. Global Mental Health, 2(e6), 1–14. doi: 10.1017/gmh.2015.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladstone M, Lancaster GA, Umar E, Nyirenda M, Kayira E, van den Broek NR, & Smyth RL (2010). The Malawi Developmental Assessment Tool (MDAT): the creation, validation, and reliability of a tool to assess child development in rural African settings. PLoS Med, 7(5), e1000273. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman DZ, Shapiro EG, & Nelson CA (2004). Measurement of vigilance in 2-year-old children. Developmental Neuropsychology, 25(3), 227–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg L(1993). The T.O.V.A. (Version 6.X) (Computer Program). Los Alamitos, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Holding P, Anum A, van de Vijver FJ, Vokhiwa M, Bugase N, Hossen T, . . . Gomes,(2016). Can we measure cognitive constructs consistently within and across cultures? Evidence from a test battery in Bangladesh, Ghana, and Tanzania. Appl Neuropsychol Child, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/21622965.2016.1206823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikekwere J, Ucheagwu V, Familiar-Lopez I, Sikorskii A, Awadu J, Ojuka JC, . . . Boivin, (2021). Attention test improvements from a cluster randomized controlled trial of caregiver training for HIV-exposed/uninfected Ugandan preschool children. Journal of Pediatrics, 235, 226–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.03.064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen P, & Greenop K (2008). Factor analysis of the Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children assessed at 5 and 10 years. South African Journal of Psychology, 38(2), 355–365. [Google Scholar]

- John CC, Bangirana P, Byarugaba J, Opoka RO, Idro R, Jurek AM, . . . Boivin, (2008). Cerebral malaria in children is associated with long-term cognitive impairment. Pediatrics, 122(1), e92–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman AS, & Kaufman NL (2004). Manual for the Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children, Second Edition. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service Publishing/Pearson Products Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Kitsao-Wekulo P, Holding P, Taylor HG, Abubakar A, Kvalsvig J, & Connolly K (2013). Nutrition as an important mediator of the impact of background variables on outcome in middle childhood. Front Hum Neurosci, 7, 713. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochieng CO (2003). Meta-Analysis of the Validation Studies of the Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children. International Journal of Testing, 3(1), 77–93. [Google Scholar]

- Ruel TD, Boivin J, Boal HE, Bangirana P, Charlebois E, Havlir DV, . . . Wong JK (2012). Neurocognitive and motor deficits in HIV-infected Ugandan children with high CD4 cell counts. Clin Infect Dis, 54(7), 1001–1009. doi:cir1037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruff HA, Capozzoli M, Dubiner K, & Parrinello RA (1990). A measure of vigilance in infancy. Infant Behavior and Development, 13 (1), 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ruff HA, & Capozzoli C (2003). Development of attention and distractibility in the first 4 years of life. Dev Psychol, 39(5), 877–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semrud-Clikeman M, Romero RA, Prado EL, Shapiro EG, Bangirana P, & John CC (2016). Selecting measures for the neurodevelopmental assessment of children in low- and middle-income countries. Child Neuropsychology, 23(7), 761–802. doi: 10.1080/09297049.2016.1216536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torras-Mana M, Gomez-Morales A, Gonzalez-Gimeno I, Fornieles-Deu A, & Brun-Gasca C (2016). Assessment of cognition and language in the early diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder: usefulness of the Bayley Scales of infant and toddler development, third edition. J Intellect Disabil Res, 60(5), 502–511. doi: 10.1111/jir.12291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyhe K. S. v., Water T. v. d., Boivin, Cotton, & Thomas KGF (2017). Cross-cultural assessment of HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Impairment using the Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children: A systematic review. Journal of the International AIDS Society, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelinsky D, Hughes S, Rumsey RI, Jordan C, & Shapiro EG (1996). The Early Childhood Vigilance Task: A new technique for the measurement of sustained attention in very young children. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 2, 23. [Google Scholar]