Key Points

Question

What are the long-term outcomes of patients with advanced kidney disease who do not pursue maintenance dialysis?

Findings

In this systematic review of 41 cohort studies comprising 5102 adults with advanced kidney disease who did not pursue dialysis, limited available evidence suggests that many patients survived several years and experienced sustained quality of life until late in their illness course. However, use of acute care services was common, and there was substantial disparity in access to supportive care near the end of life across cohorts.

Meaning

These findings suggest that advances in research and health care delivery are needed to optimize outcomes among patients who are not treated with dialysis.

This systematic review assesses cohort studies reporting survival, use of health care resources, quality of life, and end-of-life care among patients with advanced chronic kidney disease who forgo maintenance dialysis.

Abstract

Importance

An understanding of the long-term outcomes of patients with advanced chronic kidney disease not treated with maintenance dialysis is needed to improve shared decision-making and care practices for this population.

Objective

To evaluate survival, use of health care resources, changes in quality of life, and end-of-life care of patients with advanced kidney disease who forgo dialysis.

Evidence Review

MEDLINE, Embase (Excerpta Medica Database), and CINAHL (Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature) were searched from inception through December 3, 2021, for all English language longitudinal studies of adults in whom there was an explicit decision not to pursue maintenance dialysis. Two investigators independently reviewed all studies and selected those reporting survival, use of health care resources, changes in quality of life, or end-of-life care during follow-up. Studies of patients who initiated and then discontinued maintenance dialysis and patients in whom it was not clear that there was an explicit decision to forgo dialysis were excluded. One author abstracted all study data, of which 12% was independently adjudicated by a second author (<1% error rate).

Findings

Forty-one cohort studies comprising 5102 patients (range, 11-812 patients) were included in this systematic review (5%-99% men; mean age range, 60-87 years). Substantial heterogeneity in study designs and measures used to report outcomes limited comparability across studies. Median survival of cohorts ranged from 1 to 41 months as measured from a baseline mean estimated glomerular filtration rate ranging from 7 to 19 mL/min/1.73 m2. Patients generally experienced 1 to 2 hospital admissions, 6 to 16 in-hospital days, 7 to 8 clinic visits, and 2 emergency department visits per person-year. During an observation period of 8 to 24 months, mental well-being improved, and physical well-being and overall quality of life were largely stable until late in the illness course. Among patients who died during follow-up, 20% to 76% had enrolled in hospice, 27% to 68% died in a hospital setting and 12% to 71% died at home; 57% to 76% were hospitalized, and 4% to 47% received an invasive procedure during the final month of life.

Conclusions and Relevance

Many patients who do not pursue dialysis survived several years and experienced sustained quality of life until late in the illness course. Nonetheless, use of acute care services was common and intensity of end-of-life care highly variable across cohorts. These findings suggest that consistent approaches to the study of conservative kidney management are needed to enhance the generalizability of findings and develop models of care that optimize outcomes among conservatively managed patients.

Introduction

Conservative kidney management is a planned, holistic, and person-centered approach to care for patients with stages 4 to 5 advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) who do not wish to pursue maintenance dialysis.1 It includes “interventions to delay progression of kidney disease and minimize risk of adverse events or complications; shared decision making; active symptom management; detailed communication including advance care planning; psychological support; social and family support; [and] cultural and spiritual domains of care.”2(p7) Desire for a more conservative approach to treating patients with advanced CKD has galvanized efforts around the world to develop the evidence base to support the care of these patients.

Toward this end, several systematic reviews and meta-analyses3,4,5,6,7 have been conducted comparing outcomes between patients treated with dialysis and those treated conservatively. They show that dialysis is associated with longer survival compared with conservative approaches3,4,5,6 but that these survival advantages are attenuated with increasing age and comorbidity.7 Patients treated conservatively also spend less time in the hospital and die there less often compared with patients receiving dialysis,6 and early changes in quality of life appear similar between treatment groups.7,8

Although the findings of these prior studies help to inform shared decision-making about treatment of advanced CKD, they are restricted to studies comparing groups treated with dialysis and those treated conservatively. As a result, prior systematic reviews and meta-analyses reflect only a small fraction of the patients who forgo dialysis described in the literature and provide only a limited view of the clinical course of patients to guide ongoing management and anticipatory guidance to patients who have already decided that they will not pursue dialysis. To support a deeper understanding of the long-term outcomes of patients with advanced CKD who do not pursue dialysis, we performed a systematic review of longitudinal studies reporting survival, use of health care resources, quality of life, and end-of-life care of patients with advanced CKD who did not pursue dialysis.

Methods

Data Sources

This systematic review was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline and is registered in PROSPERO (CRD42020156086). An experienced medical librarian (D. L.) performed a comprehensive search of MEDLINE, Embase (Excerpta Medica Database), and CINAHL (Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature) for all English language publications pertaining to patients with advanced CKD who did not pursue maintenance dialysis from inception through January 27, 2020, with a search update through December 3, 2021. We used database-specific subject heading terms and a range of text words (conservative, non-dialysis, palliative, supportive, and medical management) previously used in the literature to describe this approach to care9 (eMethods in the Supplement) to locate all potentially relevant articles.

Study Selection

We included all longitudinal studies that enrolled patients 18 years or older with advanced CKD in whom an explicit decision was made not to pursue maintenance dialysis. We selected studies reporting survival, use of health care resources (ie, all-cause hospitalization and in-hospital days, emergency department visits, and clinic visits), changes in quality of life, or end-of-life care (ie, hospice enrollment, place of death, and hospitalization and invasive procedures during the final month of life) during follow-up and a baseline measure of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) from which outcomes were measured. We excluded studies of patients who initiated and then discontinued maintenance dialysis, those that did not include information on baseline eGFR, and those of patients in whom it was unclear that an explicit decision to forgo dialysis was made. Case reports, qualitative studies, and the gray literature were excluded.

The results of search queries were imported into Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation Ltd) for screening and study selection. Two authors (S.P.Y.W. and T.R.) independently screened titles and abstracts and reviewed full-text articles to determine study eligibility. Disagreements were resolved through consensus by another author (L.Z. or A.L.J.).

Data Extraction

Data extraction was performed by 1 reviewer (S.P.Y.W.) using a standardized data extraction form. For studies comparing multiple treatment groups, we collected information only on groups of patients in whom there was a decision not to pursue dialysis from each study. From each study, we collected information on study design, year of publication, country of origin, sample size, study inclusion criteria, clinical setting, and whether patients were cared for in a dedicated care pathway for those not planning to be treated with dialysis or in usual nephrology care settings. Because nearly all the studies did not report information on the race and ethnicity of its study participants, this information was not collected. We recorded baseline age, sex, eGFR, and distribution of comorbidities of study participants. We recorded measures of survival, use of health care resources, and changes in quality of life. We also collected information on patterns of end-of-life care for study participants who died during study follow-up. We contacted study authors by email to obtain any missing data. One investigator (T.O.) independently reviewed the full text of 5 randomly selected studies (12%) to confirm accuracy of data extraction (<1% errors found).

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Owing to the heterogeneity in study designs, patient populations, approaches to care, and measures used across studies, we opted not to meta-analyze collected data; we herein provide a narrative synthesis of reported outcomes. For our primary outcome, we evaluated the median (IQR) survival of patients and the baseline mean eGFR from which survival was measured. For studies reporting only a threshold eGFR value (eg, <20 mL/min/1.73 m2), the closest value (ie, 19 mL/min/1.73 m2) was used in place of mean values. Median eGFR values were used in place of mean values when the latter were not reported. For studies that did not report median and/or IQR measures of survival, these values were abstracted from reported Kaplan-Meier survival curves, estimated using reported mortality rates assuming an exponential distribution, and/or calculated using reported means of survival and their SDs.10 Studies that had insufficient information to estimate median survival or were limited to only patients who died during follow-up were not included in survival analyses. Preplanned subgroup assessment of survival by study region (Asia, Australia, continental Europe, North America, and the UK), year of study publication (before 2010, 2010-2015, and after 2015), mean age of the study cohort (70-79 and ≥80 years), and approach to care (as part of general nephrology care vs a dedicated care pathway) were also performed.

As secondary outcomes, we assessed use of health care resources, trajectories of quality of life, and end-of-life care of patients. Evaluation of these secondary measures by study region, publication date, age of cohort, and approach to care could not be performed owing to the low number of studies in each category.

Results

Study Characteristics

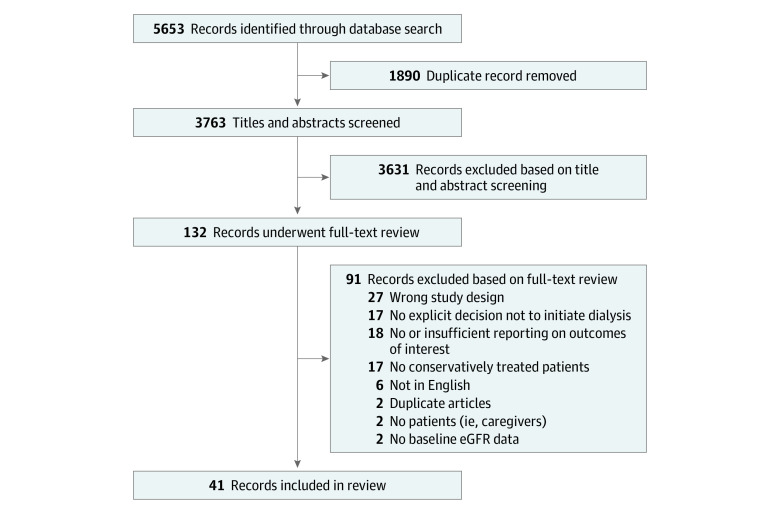

The literature search yielded 5653 references, of which the full text was reviewed in 132 (Figure 1). A total of 41 cohort studies comprising 5102 patients (study size range, 11-812 patients; 5%-99% men; mean age range, 60-87 years) were included in this review (eTable 1 in the Supplement).11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51 No clinical trials were identified in our search.

Figure 1. PRISMA Flow Diagram of Study Selection.

eGFR indicates estimated glomerular filtration rate.

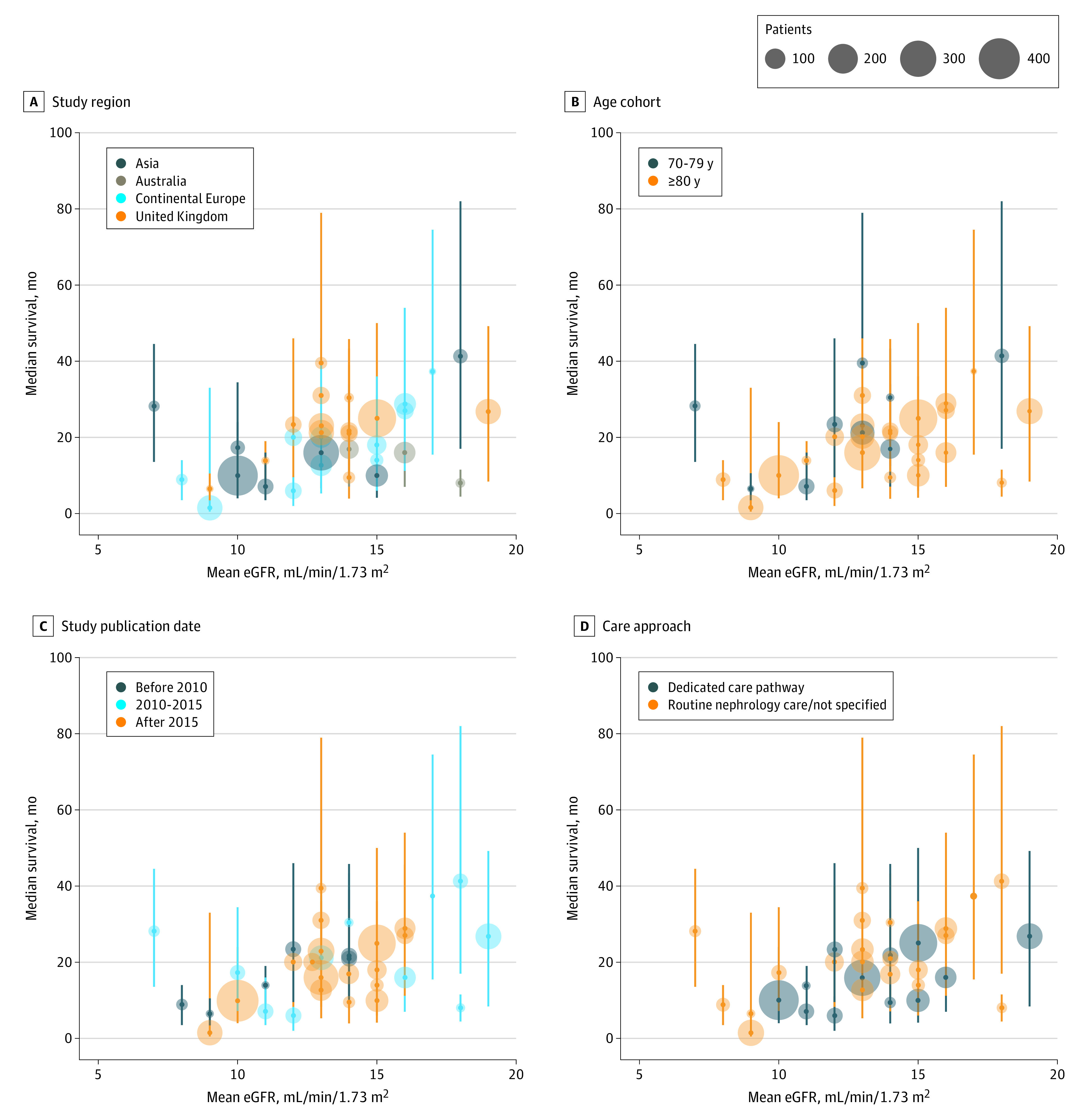

Survival

Thirty-four studies (3754 patients)11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,20,21,22,23,25,26,27,29,30,31,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,50 provided information on median survival and IQR or sufficient information to estimate these values (eTable 2 in the Supplement). The range of median survival of cohorts was 1 to 41 months as measured from a baseline mean eGFR range of 7 to 19 mL/min/1.73 m2 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Median Survival of Cohorts With Conservative Management According to Baseline Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR).

Median survival varied widely by study region (A), age group (B), year of study publication (C), and approach to conservative care (D). Vertical lines represent IQRs.

The median survival of cohorts ranged from 1 to 31 months in the UK (13 studies; 1320 patients),12,15,16,18,20,22,25,31,34,35,36,43,50 6 to 37 months in continental Europe (11 studies; 1021 patients),21,23,29,37,38,39,40,45,46,47,48 7 to 41 months in Asia (7 studies; 1147 patients),13,14,26,27,41,42,44 and 8 to 17 months in Australia (3 studies; 258 patients).11,17,30 The wide ranges in median survival for cohort members in these regions corresponded to the wide ranges in baseline mean eGFR (7-18 mL/min/1.73 m2 for Asia, 14-18 mL/min/1.73 m2 for Australia, 8-17 mL/min/1.73 m2 for continental Europe, and 9-19 mL/min/1.73 m2 for the UK). No studies published in North America provided sufficient information to estimate median survival of cohort members in this region. Median survival was 6 to 22 months and baseline mean eGFR was 8 to 14 mL/min/1.73 m2 for cohorts published before 2010 (6 studies; 317 patients),12,20,23,31,43,50 6 to 37 months and 7 to 19 mL/min/1.73 m2 for cohorts published from 2010 to 2015 (11 studies; 851 patients),11,13,15,17,18,22,39,41,42,44,45 and 1 to 39 months and 9 to 16 mL/min/1.73 m2 for cohorts published after 2015 (17 studies; 2586 patients).14,16,21,25,26,27,29,30,34,35,36,37,38,40,46,47,48 Younger cohorts aged 70 to 79 years (9 studies; 607 patients)13,15,18,30,34,42,43,44,50 had a median survival of 7 to 41 months, and cohorts 80 years or older (25 studies; 3186 patients)11,12,14,16,17,19,20,21,23,25,26,27,29,30,31,35,36,37,38,39,40,45,46,47,48 had a median survival of 1 to 37 months despite overlapping ranges of baseline mean eGFR (7-18 and 8-18 mL/min/1.73 m2, respectively). Patients who were treated in usual nephrology care settings or who had received an unspecified approach to care (22 studies; 1886 patients)15,16,17,18,20,21,23,29,30,34,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,46,47,48 had a median survival of 1 to 39 months and baseline mean eGFR of 7 to 17 mL/min/1.73 m2, whereas patients managed in a dedicated care pathway (12 studies; 1944 patients)11,12,13,14,22,25,26,27,31,35,45,50 had a median survival of 1 to 27 months and mean baseline eGFR of 10 to 19 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Quality of Life

Eight studies (500 patients)11,18,25,33,34,40,41,46 measured changes in quality of life among patients (Table 1) using different standardized instruments (36-Item Short Form Health Survey [SF-36], Kidney Disease Quality of Life Short Form [KDQOL-SF], and EuroQol-5D Scale). Studies also ascertained ancillary measures pertaining to quality of life, including symptom burden (Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale and Palliative Care Outcome Scale–Symptoms), functional status (Barthel Index), frailty (Timed Up-and-Go), mental health symptoms (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale), life satisfaction (Satisfaction With Life Scale), and self-rated overall health (visual analog scale). The period of observation for changes in quality of life ranged from 8 to 24 months across studies.

Table 1. Quality-of-Life Trajectories.

| Source | No. of patients | Follow-up, moa | Change in status | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall QOL | Physical well-being | Mental well-being | Symptom burden | Self-rated health | |||

| Brown et al,11 2015 | 122b | 10c | NR | SF-36 physical health worse | SF-36 mental health better | MSAS worse, POS-S worse | NR |

| Da Silva-Gane et al,18 2012 | 30 | 15 | NR | SF-36 physical health no change | SF-36 mental health better | SWLS no change, HADS depression no change, HADS anxiety no change | NR |

| Kilshaw et al,25 2016 | 41 | 11c | EQ5D worse | NR | NR | TUG worse, Barthel Index no change | NR |

| Murtagh et al,33 2011 | 49 | 8 | NR | NR | NR | MSAS worse, POS-S worse | NR |

| Phair et al,34 2018 | 42 | 12 | EQ5D worse | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Rubio Rubio et al,40 2019 | 64 | NR | NR | SF-36 physical health no change | SF-36 mental health better | NR | NR |

| Seow et al,41 2013 | 63 | 24 | NR | KDQOL-SF physical health worse | KDQOL-SF mental health better | NR | NR |

| van Loon et al,46 2019 | 89 | NR | EQ5D worse | NR | NR | NR | VAS worse |

Abbreviations: EQ5D, EuroQol-5D Scale; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; KDQOL-SF, Kidney Disease Quality of Life Short Form; MSAS, Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale; NR, not reported; POS-S, Palliative Care Outcome Scale–Symptoms; QOL, quality of life; SF-36, 36-Item Short Form Health Survey; SWLS, Satisfaction With Life Scale; TUG, Timed Up-and-Go; VAS, visual analog scale.

Unless otherwise indicated, data are expressed as mean.

Response rates for each survey ranged from 55% to 74%.

Indicates median values.

Studies measuring quality of life using the EuroQol-5D Scale reported small decrements (3 studies; 172 patients)25,34,46 in overall quality of life during an 11- to 12-month time frame. Although 1 study using the SF-36 found that most of its cohort members (12 of 19 patients [63%]) reported worse physical well-being during a 12-month follow-up period,11 3 other studies (157 patients) using either the SF-36 or the KDQOL-SF reported stable physical well-being during a 15- to 24-month follow-up period18,40 and then decline thereafter.41 All studies (4 studies; 279 patients)11,18,40,41 using either the SF-36 or the KDQOL-SF reported improvements in mental well-being among their cohort members.

Although in 1 study most patients reported improvement in symptom burden during a 12-month follow-up period on the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (12 of 21 [57%]) and Palliative Care Outcome Scale–Symptoms (49 of 69 [71%]) instruments,11 in another study examining symptom burden in the final year of life limited to decedents (49 patients),33 Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale and Palliative Care Outcome Scale–Symptoms scores were generally stable until the final 3 months of life, after which symptom burden increased before death. One study (30 patients)18 reported stable symptoms of anxiety and depression (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale) and unchanged sense of life satisfaction (Satisfaction With Life Scale) among its cohort members during a 15-month follow-up. One study (41 patients)25 reported sustained ability to perform activities of daily living (Barthel Index) but increasing risk of falls (Timed Up-and-Go) among its cohort members during an 11-month follow-up. One study (89 patients)46 reported lower self-rated health (visual analog scale) over time among its cohort members.

Use of Health Care Resources

Ten studies (570 patients)12,19,21,34,36,39,42,45,46,48 provided information on use of health care resources during follow-up (Table 2). Whereas 1 study (42 patients)42 reported a mean of 4 hospital admissions per person-year and 38 in-hospital days per person-year among its cohort members, the other studies (528 patients)12,19,21,34,36,39,45,46,48 reported approximately 1 to 2 hospital admissions per person-year and 6 to 16 in-hospital days per person-year. It was also reported that patients experienced approximately 7 to 8 clinic visits per person-year (2 studies; 207 patients)36,48 and 2 emergency department visits per person-year (1 study; 76 patients).45

Table 2. Use of Health Care Resources.

| Source | No. of patients | Follow-up, moa | No. of resources used per person-yeara | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalizations | In-hospital days | Emergency department visits | Clinic visits | |||

| Carson et al,12 2009 | 29 | 14 | NR | 16 | NR | NR |

| De Biase et al,19 2008 | 11 | 15 | 2b | 11b | NR | NR |

| García Testal et al,21 2021 | 54 | NR | NR | 15 | NR | NR |

| Phair et al,34 2018 | 42 | 12 | NR | 11 | NR | NR |

| Raman et al,36 2018 | 81 | NR | NR | 10 | NR | 8a |

| Rodriguez Villarreal et al,39 2014 | 20 | 19b | 1 | NR | NR | NR |

| Shum et al,42 2014 | 42 | 23b | 4 | 38 | NR | NR |

| Teruel et al,45 2015 | 76 | 8 | 1 | NR | 2 | NR |

| van Loon et al,46 2019 | 89 | 6 | 2b | 8b | NR | NR |

| Verberne et al,48 2018 | 126 | NR | 1 | 6 | NR | 7 |

Abbreviation: NR, not reported.

Unless otherwise indicated, data are expressed as mean.

Indicates median value.

End-of-Life Care

Fourteen studies (1709 patients)12,19,22,24,26,28,30,40,42,43,45,49,50,51 provided information on end-of-life care for cohort members who died during follow-up (Table 3). Reported rates of hospice enrollment (20%-76%),22,24,28,51 hospitalization during the final month of life (57%-76%),22,51 in-hospital death (27%-68%),12,19,22,24,26,30,40,43,45,49,51 and in-home death (12%-71%),19,30,40,45,50 were wide ranging. One study (39 patients)42 that defined intensive procedures during the final month of life as receipt of operative or endoscopic procedures, mechanical ventilation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and/or artificial enteral nutrition reported 47% of decedents received such procedures. Another study (812 patients)51 that examined only rates of mechanical ventilation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and artificial enteral nutrition found that only 4% of decedents received these intensive procedures during the final month of life.

Table 3. End-of-Life Care.

| Source | No. of decedents | Decedents, % | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalization during final month of life | Intensive procedures during final month of life | Hospice enrollment | In-hospital death | In-home death | Other place of death | ||

| Carson et al,12 2009 | 25 | NR | NR | NR | 36 | NR | Home or hospice, 40 |

| De Biase et al,19 2008 | 5 | NR | NR | NR | 40 | 60 | NR |

| Hussain et al,22 2013 | 77 | 76 | NR | 76 | 47 | NR | Hospice,18; nursing home, 12 |

| Kamar et al,24 2017 | 103 | NR | NR | 25 | 27 | NR | Home or LTC, 32; other, 17 |

| Kwok et al,26 2016 | 226 | NR | NR | NR | 47 | NR | Emergency department, 4 |

| Lovell et al,28 2017 | 146 | NR | NR | 20 | 46 | 34 | NR |

| Morton et al,30 2016 | 72 | NR | NR | NR | 42 | 12 | Hospice, 14; nursing home, 6 |

| Rubio Rubio et al,40 2019 | 38 | NR | NR | NR | 68 | 32 | NR |

| Shum et al,42 2014 | 39 | NR | 47 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Smith et al,43 2003 | 34 | NR | NR | NR | 35 | NR | Home or hospice, 65 |

| Teruel et al,45 2015 | 48 | NR | NR | NR | 31 | 50 | Inpatient palliative care, 19 |

| Verberne et al,49 2020 | 56 | NR | NR | NR | 32 | NR | NR |

| Wong et al,50 2007 | 28 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 71 | NR |

| Wong et al,51 2018 | 812 | 57 | 4 | 39 | 41 | NR | NR |

Abbreviations: LTC, long-term care; NR, not reported.

Discussion

This systematic review provides a comprehensive summary of the long-term outcomes of patients with advanced CKD who did not pursue maintenance dialysis. Our findings offer insights into directions for research and clinical care to improve survival, quality of life, use of health care resources, and end-of-life care for members of this population (eFigure in the Supplement).

Although research on conservative kidney management has been growing, available evidence is best regarded as very limited and preliminary. We observed a high degree of heterogeneity in study designs and measures used to assess outcomes across studies, thus limiting comparability across studies and the generalizability of our findings. In contrast, there have been national and international efforts to establish unified approaches to epidemiological surveillance of kidney replacement therapy and its outcomes.52,53 An important step toward advancing research on conservative kidney management is to implement similar approaches to the study and reporting of its practices and outcomes.

Our findings challenge the common misconception that the only alternative to dialysis for many patients with advanced CKD is no care54 or death.55 Despite the advanced ages and significant comorbid burden of cohorts in this study, most patients survived several years after the decision to forgo dialysis was made. We also found that mental well-being improved over time and that physical well-being and overall quality of life were largely stable until late in the illness course. These findings not only suggest that conservative kidney management may be a viable and positive therapeutic alternative to dialysis, they also highlight the strengths of its multidisciplinary approach to care and aggressive symptom management. Still, there was substantial variation in survival across cohorts according to regions, time periods, and approaches to care. We suspect that the observed variation is likely attributable to differences in local health systems and practices and their changes over time.56,57,58,59 Hence, our findings also underscore the need to develop models of care that optimize outcomes for members of this population who have the potential to live well and for quite some time without dialysis.

Although patients who forgo dialysis spend less time in the hospital than patients undergoing maintenance dialysis,13,36,43,47 we found that many still frequently used acute care services. Previous studies52,60 have shown that many existing health systems are not optimally configured to support the needs of patients who do not wish to pursue dialysis and that patients and their clinicians often fall back on acute care services when there are gaps in community-based and preventive care services.56 Collectively, our findings point to an area of focus in efforts to develop the care infrastructure that can help patients avoid or mitigate the impact of a health crisis.

We observed striking disparities in access to quality end-of-life care across cohorts. Although among some cohorts, most patients received hospice care, avoided burdensome procedures near the end-of-life, and died at home, for other cohorts, only a minority accessed supportive care near the end of life. One of the distinct benefits afforded by conservative kidney management is that patients who choose this option experience less intensive care near the end of life than patients who receive dialysis.6,22,30,42,43,51 However, it also is recognized that patients who forgo dialysis receive hospice services less often and die in the hospital setting more often than other patients in the same health system but with other serious illness, such as terminal cancer.51 More research is needed to understand and overcome the barriers to supportive care for this population.

Limitations

The present study should be interpreted within the context of the following limitations. First, in studies for which mean eGFR, median survival, and IQR were estimated based on available data reported, these values are imprecise and limit the reliability of our findings. Second, the present review includes only patients in whom there had been an explicit decision made to not undergo dialysis and for whom conservative management was likely a planned approach to care. Thus, our findings do not provide insights on the experiences of patients with untreated advanced CKD, those who are unsure about dialysis, or those who had not yet faced decisions about dialysis in their illness course.61,62,63 The present study also does not reflect the experiences of patients in developing countries or other resource-poor settings where conservative options may not be widely available.59 Third, although we eliminated duplicate studies from this review, owing to similar studies conducted at the same site during overlapping time periods, there were several studies that may have included duplicate cases.32,33,47,48 These cases likely constituted a very small proportion (<4%) of the total number of patients included in this review and would unlikely have a substantial effect on our main findings. Fourth, lack of consistency is apparent in the terminology used to describe caring for patients not treated with dialysis in published literature.64 Although we used multiple different terms in our literature search to identify all relevant articles pertaining to this approach to care, articles that used alternate terms might have been missed. Fifth, approaches to quality and bias assessments of cohort studies recommended for systematic reviews pertain to studies comparing 2 or more treatment groups65 and therefore were not appropriate for the present analyses that focused on the long-term outcomes of only patients who had chosen not to pursue dialysis. To facilitate reader appraisal of studies included in this review, we provide extensive descriptions of cohort design, characteristics, and measures collected for each study to present the relevance, consistency, comprehensiveness, and depth of detail provided on the populations and outcomes studied.66

Conclusions

Despite substantial heterogeneity across studies on the long-term outcomes of patients with advanced CKD who forgo maintenance dialysis, this systematic review found that patients could survive several years and experienced improvements in their mental well-being in addition to sustaining physical well-being and overall quality of life until late in their illness course. Nonetheless, use of acute care services was common and intensity of end-of-life care was highly variable across cohorts of patients. Collectively, our findings demonstrate the need to implement systematic and unified research methods for conservative kidney management and to develop models of care and the care infrastructure to advance practice and outcomes of conservative kidney management.

eMethods. Search Strategy for Medline (EBSCO)

eTable 1. Description of Conservatively Managed Cohorts

eTable 2. Median Survival and Mean eGFR of Conservatively Managed Cohorts

eFigure. Summary of Findings of Current Systematic Review and Recommendations to Advance Conservative Kidney Management

References

- 1.Harris DCH, Davies SJ, Finkelstein FO, et al. ; Strategic Plan Working Groups . Strategic plan for integrated care of patients with kidney failure. Kidney Int. 2020;98(5S):S117-S134. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.07.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davison SN, Levin A, Moss AH, et al. ; Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes . Executive summary of the KDIGO Controversies Conference on Supportive Care in Chronic Kidney Disease: developing a roadmap to improving quality care. Kidney Int. 2015;88(3):447-459. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foote C, Kotwal S, Gallagher M, Cass A, Brown M, Jardine M. Survival outcomes of supportive care versus dialysis therapies for elderly patients with end-stage kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrology (Carlton). 2016;21(3):241-253. doi: 10.1111/nep.12586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wongrakpanich S, Susantitaphong P, Isaranuwatchai S, Chenbhanich J, Eiam-Ong S, Jaber BL. Dialysis therapy and conservative management of advanced chronic kidney disease in the elderly: a systematic review. Nephron. 2017;137(3):178-189. doi: 10.1159/000477361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fu R, Sekercioglu N, Mathur MB, Couban R, Coyte PC. Dialysis initiation and all-cause mortality among incident adult patients with advanced CKD: a meta-analysis with bias analysis. Kidney Med. 2020;3(1):64-75.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.xkme.2020.09.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engelbrecht BL, Kristian MJ, Inge E, et al. Does conservative kidney management offer a quantity or quality of life benefit compared to dialysis? a systematic review. BMC Nephrol. 2021;22(1):307. doi: 10.1186/s12882-021-02516-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Connor NR, Kumar P. Conservative management of end-stage renal disease without dialysis: a systematic review. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(2):228-235. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ren Q, Shi Q, Ma T, Wang J, Li Q, Li X. Quality of life, symptoms, and sleep quality of elderly with end-stage renal disease receiving conservative management: a systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019;17(1):78. doi: 10.1186/s12955-019-1146-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murtagh FE, Burns A, Moranne O, Morton RL, Naicker S. Supportive care: comprehensive conservative care in end-stage kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(10):1909-1914. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04840516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown MA, Collett GK, Josland EA, Foote C, Li Q, Brennan FP. CKD in elderly patients managed without dialysis: survival, symptoms, and quality of life. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(2):260-268. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03330414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carson RC, Juszczak M, Davenport A, Burns A. Is maximum conservative management an equivalent treatment option to dialysis for elderly patients with significant comorbid disease? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(10):1611-1619. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00510109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan CK, Wong SSZ, Ho ETL, et al. Supportive management in patients with end-stage renal disease: local experience in Hong Kong. Hong Kong J Nephrol. 2010;12(1):31-6. doi: 10.1016/S1561-5413(10)60006-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan KY, Yip T, Yap DYH, Sham MK, Tsang KW. A pilot comprehensive psychoeducation program for fluid management in renal palliative care patients: impact on health care utilization. J Palliat Med. 2020;23(11):1518-1524. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2019.0424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chandna SM, Da Silva-Gane M, Marshall C, Warwicker P, Greenwood RN, Farrington K. Survival of elderly patients with stage 5 CKD: comparison of conservative management and renal replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(5):1608-1614. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chandna SM, Carpenter L, Da Silva-Gane M, Warwicker P, Greenwood RN, Farrington K. Rate of decline of kidney function, modality choice, and survival in elderly patients with advanced kidney disease. Nephron. 2016;134(2):64-72. doi: 10.1159/000447784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheikh Hassan HI, Brennan F, Collett G, Josland EA, Brown MA. Efficacy and safety of gabapentin for uremic pruritus and restless legs syndrome in conservatively managed patients with chronic kidney disease. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49(4):782-789. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Da Silva-Gane M, Wellsted D, Greenshields H, Norton S, Chandna SM, Farrington K. Quality of life and survival in patients with advanced kidney failure managed conservatively or by dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(12):2002-2009. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01130112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Biase V, Tobaldini O, Boaretti C, et al. Prolonged conservative treatment for frail elderly patients with end-stage renal disease: the Verona experience. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(4):1313-1317. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ellam T, El-Kossi M, Prasanth KC, El-Nahas M, Khwaja A. Conservatively managed patients with stage 5 chronic kidney disease—outcomes from a single center experience. QJM. 2009;102(8):547-554. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcp068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.García Testal A, García Maset R, Fornés Ferrer V, et al. Cohort study with patients older than 80 years with stage 5 chronic kidney failure on hemodialysis vs conservative treatment: survival outcomes and use of healthcare resources. Ther Apher Dial. 2021;25(1):24-32. doi: 10.1111/1744-9987.13493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hussain JA, Mooney A, Russon L. Comparison of survival analysis and palliative care involvement in patients aged over 70 years choosing conservative management or renal replacement therapy in advanced chronic kidney disease. Palliat Med. 2013;27(9):829-839. doi: 10.1177/0269216313484380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joly D, Anglicheau D, Alberti C, et al. Octogenarians reaching end-stage renal disease: cohort study of decision-making and clinical outcomes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(4):1012-1021. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000054493.04151.80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamar FB, Tam-Tham H, Thomas C. A description of advanced chronic kidney disease patients in a major urban center receiving conservative care. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2017;4:2054358117718538. doi: 10.1177/2054358117718538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kilshaw L, Sammut H, Asher R, Williams P, Saxena R, Howse M. A study to describe the health trajectory of patients with advanced renal disease who choose not to receive dialysis. Clin Kidney J. 2016;9(3):470-475. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfw005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kwok AO, Yuen SK, Yong DS, Tse DM. The symptoms prevalence, medical interventions, and health care service needs for patients with end-stage renal disease in a renal palliative care program. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2016;33(10):952-958. doi: 10.1177/1049909115598930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwok WH, Yong SP, Kwok OL. Outcomes in elderly patients with end-stage renal disease: comparison of renal replacement therapy and conservative management. Hong Kong J Nephrol. 2016;19:42-56. doi: 10.1016/j.hkjn.2016.04.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lovell N, Jones C, Baynes D, Dinning S, Vinen K, Murtagh FE. Understanding patterns and factors associated with place of death in patients with end-stage kidney disease: a retrospective cohort study. Palliat Med. 2017;31(3):283-288. doi: 10.1177/0269216316655747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moranne O, Fafin C, Roche S, et al. Treatment plans and outcomes in elderly patients reaching advanced chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2018;33(12):2182-2191. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfy046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morton RL, Webster AC, McGeechan K, et al. Conservative management and end-of-life care in an Australian cohort with ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(12):2195-2203. doi: 10.2215/CJN.11861115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murtagh FE, Marsh JE, Donohoe P, Ekbal NJ, Sheerin NS, Harris FE. Dialysis or not? a comparative survival study of patients over 75 years with chronic kidney disease stage 5. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22(7):1955-1962. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murtagh FE, Addington-Hall JM, Higginson IJ. End-stage renal disease: a new trajectory of functional decline in the last year of life. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(2):304-308. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03248.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murtagh FE, Sheerin NS, Addington-Hall J, Higginson IJ. Trajectories of illness in stage 5 chronic kidney disease: a longitudinal study of patient symptoms and concerns in the last year of life. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(7):1580-1590. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09021010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Phair G, Agus A, Normand C, et al. Healthcare use, costs and quality of life in patients with end-stage kidney disease receiving conservative management: results from a multi-centre observational study (PACKS). Palliat Med. 2018;32(8):1401-1409. doi: 10.1177/0269216318775247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pyart R, Aggett J, Goodland A, et al. Exploring the choices and outcomes of older patients with advanced kidney disease. PLoS One. 2020;15(6):e0234309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0234309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raman M, Middleton RJ, Kalra PA, Green D. Outcomes in dialysis versus conservative care for older patients: a prospective cohort analysis of stage 5 chronic kidney disease. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):e0206469. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramspek CL, Verberne WR, van Buren M, Dekker FW, Bos WJW, van Diepen M. Predicting mortality risk on dialysis and conservative care: development and internal validation of a prediction tool for older patients with advanced chronic kidney disease. Clin Kidney J. 2020;14(1):189-196. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfaa021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reindl-Schwaighofer R, Kainz A, Kammer M, Dumfarth A, Oberbauer R. Survival analysis of conservative vs dialysis treatment of elderly patients with CKD stage 5. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0181345. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodriguez Villarreal I, Ortega O, Hinostroza J, et al. Geriatric assessment for therapeutic decision-making regarding renal replacement in elderly patients with advanced chronic kidney disease. Nephron Clin Pract. 2014;128(1-2):73-78. doi: 10.1159/000363624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rubio Rubio MV, Lou Arnal LM, Gimeno Orna JA, et al. Survival and quality of life in elderly patients in conservative management. Nefrologia (Engl Ed). 2019;39(2):141-150. doi: 10.1016/j.nefroe.2018.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seow YY, Cheung YB, Qu LM, Yee AC. Trajectory of quality of life for poor prognosis stage 5D chronic kidney disease with and without dialysis. Am J Nephrol. 2013;37(3):231-238. doi: 10.1159/000347220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shum CK, Tam KF, Chak WL, Chan TC, Mak YF, Chau KF. Outcomes in older adults with stage 5 chronic kidney disease: comparison of peritoneal dialysis and conservative management. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69(3):308-314. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith C, Da Silva-Gane M, Chandna S, Warwicker P, Greenwood R, Farrington K. Choosing not to dialyse: evaluation of planned non-dialytic management in a cohort of patients with end-stage renal failure. Nephron Clin Pract. 2003;95(2):c40-c46. doi: 10.1159/000073708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Szeto CC, Kwan BC, Chow KM, et al. Life expectancy of Chinese patients with chronic kidney disease without dialysis. Nephrology (Carlton). 2011;16(8):715-719. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2011.01504.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Teruel JL, Rexach L, Burguera V, et al. Home palliative care for patients with advanced chronic kidney disease: preliminary results. Healthcare (Basel). 2015;3(4):1064-1074. doi: 10.3390/healthcare3041064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Loon IN, Goto NA, Boereboom FTJ, Verhaar MC, Bots ML, Hamaker ME. Quality of life after the initiation of dialysis or maximal conservative management in elderly patients: a longitudinal analysis of the Geriatric Assessment in Older Patients Starting Dialysis (GOLD) study. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20(1):108. doi: 10.1186/s12882-019-1268-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Verberne WR, Geers AB, Jellema WT, Vincent HH, van Delden JJ, Bos WJ. Comparative survival among older adults with advanced kidney disease managed conservatively versus with dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(4):633-640. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07510715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Verberne WR, Dijkers J, Kelder JC, et al. Value-based evaluation of dialysis versus conservative care in older patients with advanced chronic kidney disease: a cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2018;19(1):205. doi: 10.1186/s12882-018-1004-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Verberne WR, Ocak G, van Gils-Verrij LA, van Delden JJM, Bos WJW. Hospital utilization and costs in older patients with advanced chronic kidney disease choosing conservative care or dialysis: a retrospective cohort study. Blood Purif. 2020;49(4):479-489. doi: 10.1159/000505569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wong CF, McCarthy M, Howse ML, Williams PS. Factors affecting survival in advanced chronic kidney disease patients who choose not to receive dialysis. Ren Fail. 2007;29(6):653-659. doi: 10.1080/08860220701459634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wong SPY, Yu MK, Green PK, Liu CF, Hebert PL, O’Hare AM. End-of-life care for patients with advanced kidney disease in the US Veterans Affairs health care system, 2000-2011. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;72(1):42-49. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Robinson BM, Bieber B, Pisoni RL, Port FK. Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS): its strengths, limitations, and role in informing practices and policies. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(11):1897-1905. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04940512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu FX, Rutherford P, Smoyer-Tomic K, Prichard S, Laplante S. A global overview of renal registries: a systematic review. BMC Nephrol. 2015;16:31. doi: 10.1186/s12882-015-0028-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ladin K, Pandya R, Kannam A, et al. Discussing conservative management with older patients with CKD: an interview study of nephrologists. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;71(5):627-635. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hussain JA, Flemming K, Murtagh FE, Johnson MJ. Patient and health care professional decision-making to commence and withdraw from renal dialysis: a systematic review of qualitative research. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(7):1201-1215. doi: 10.2215/CJN.11091114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wong SPY, Boyapati S, Engelberg RA, Thorsteinsdottir B, Taylor JS, O’Hare AM. Experiences of US nephrologists in the delivery of conservative care to patients with advanced kidney disease: a national qualitative study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;75(2):167-176. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grubbs V, Tuot DS, Powe NR, O’Donoghue D, Chesla CA. System-level barriers and facilitators for foregoing or withdrawing dialysis: a qualitative study of nephrologists in the United States and England. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;70(5):602-610. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.12.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wong SPY, McFarland LV, Liu CF, Laundry RJ, Hebert PL, O’Hare AM. Care practices for patients with advanced kidney disease who forgo maintenance dialysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(3):305-313. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lunney M, Bello AK, Levin A, et al. Availability, accessibility, and quality of conservative kidney management worldwide. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;16(1):79-87. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09070620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kaufman SR. And a Time to Die: How American Hospitals Shape the End of Life. University of Chicago Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wong SP, Vig EK, Taylor JS, et al. Timing of initiation of maintenance dialysis: a qualitative analysis of the electronic medical records of a national cohort of patients from the Department of Veterans Affairs. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(2):228-235. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kurella Tamura M, Desai M, Kapphahn KI, Thomas IC, Asch SM, Chertow GM. Dialysis versus medical management at different ages and levels of kidney function in veterans with advanced CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29(8):2169-2177. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2017121273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wong SP, Hebert PL, Laundry RJ, et al. Decisions about renal replacement therapy in patients with advanced kidney disease in the US Department of Veterans Affairs, 2000-2011. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(10):1825-1833. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03760416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Winterbottom AE, Mooney A, Russon L, et al. Kidney disease pathways, options and decisions: an environmental scan of international patient decision aids. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35(12):2072-2082. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfaa102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zeng X, Zhang Y, Kwong JS, et al. The methodological quality assessment tools for preclinical and clinical studies, systematic review and meta-analysis, and clinical practice guideline: a systematic review. J Evid Based Med. 2015;8(1):2-10. doi: 10.1111/jebm.12141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Iorio A, Spencer FA, Falavigna M, et al. Use of GRADE for assessment of evidence about prognosis: rating confidence in estimates of event rates in broad categories of patients. BMJ. 2015;350:h870. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Search Strategy for Medline (EBSCO)

eTable 1. Description of Conservatively Managed Cohorts

eTable 2. Median Survival and Mean eGFR of Conservatively Managed Cohorts

eFigure. Summary of Findings of Current Systematic Review and Recommendations to Advance Conservative Kidney Management