Abstract

Background

Positive influence of the sun on psoriasis is a common assumption in dermatology. Other season‐related factors such as mental health may interfere. However, the role of seasonal effects on psoriasis needs to be clarified. This review aims to systematically analyze the literature on seasonal variation on psoriasis with emphasis on Northern and Central Europe representing temperate climate conditions.

Materials and methods

Enrolled literature was identified through PubMed, EMBASE, and BIOSIS. An additional manual search of old reports before the introduction of efficient modern therapies, which can interfere with the spontaneous disease, was performed.

Results

Thirteen studies were enrolled. About 50% of psoriasis patients were stable and showed no seasonal difference between seasons. Approximately 30% improved in summer, and 20% performed better in winter, some with marked summer worsening. European results matched international reports from different continents and hemispheres with climate extremes. The psychological effects could not be ruled out.

Conclusion

About 50% of psoriasis patients experience a season‐independent disease, however, with a subset of patients who do better in summer. Others again do better in winter, with a few of these having marked worsening in warm periods. Individual season‐related activity records should be paid proper attention to when considering light therapy or climatotherapy as a treatment.

Keywords: climate, climatotherapy, psoriasis vulgaris, seasonal variation, ultraviolet light, UVB therapy

1. INTRODUCTION

Psoriasis is a chronic, hyperproliferative, inflammatory, and autoimmune condition of the skin. It is a multifactorial disease associated with a genetic predisposition, health status, and numerous environmental factors. 1 , 2 Smoking, alcohol, drugs, diet, infections, and stress are all known to aggravate psoriasis. 3 , 4 Thus, seasonal influence on psoriasis is likely to be orchestrated by a range of other factors as well as controlling disease activity at any time.

The overall prevalence of psoriasis is estimated to be 3%, but major geographical and ethnic variations have been reported worldwide. 2 Psoriasis is more frequent on the European continent with a prevalence of around 2–3%. Race along with geography seems to be a decisive influencing factor. In the United States, psoriasis has been found in 6.5/1000 of White in contrast to 0.6/1000 in African Americans. 2 , 3

In research settings, the Northern and Central European climate is generally accepted as an index climate for observing the seasonal influence on skin diseases. Northern and Central Europe is due to the high prevalence of psoriasis and dissimilar seasonal weather, for example, cold winters and warm summers, suited for the study of the seasonal influence on psoriasis.

It is believed that exposure to sunlight has a positive influence on psoriasis particularly in skin type III and IV (rarely and never tanned). 5 Ultraviolet B (UVB) phototherapy and climatotherapy, representing aggressive use of sunlight, are well adapted in the treatment of psoriasis. The positive effect of light therapy has probably shaped the idea of seasonal variation and psoriasis with automatic improvement in summer, defined as the sunny period. Contrarily, it is a general assumption that lack of sunlight and lower temperatures influence psoriasis negatively. However, the daily sun exposure and temperature represent two different physiological vectors. For instance, heat may dilate the cutaneous vasculature and create swelling and itch on a psoriatic plaque.

Several variables can affect psoriasis, and to study seasonal variation independently is unrealistic.

Patients with a chronic condition like psoriasis will experience a range of psychosocial problems such as worry, elevated levels of anxiety, and depression. 6 Psychological distress is a common part of the illness, which negatively affects both disease severity and quality of life (DLQI). 7 , 8 The fact that stress is a foremost trigger on the onset and exacerbation of psoriasis has been emphasized for many years. 4 , 5 , 9 , 10

In addition to this, psychological well‐being can also be changed by season with depression being more frequent in the dark winter season. 11 , 12 Seasonal affective disorder (SAD) is a systematic seasonal pattern of mood disorders. It is unsure whether SAD is a categorical diagnosis or an extreme form of a dimensional seasonality trait. Yet, even people with subsyndromal SAD still experience distress and functional impairment during the winter. 13 The prevalence of SAD correlates with latitude but not with other environmental factors such as cloud, sunshine hours, snowfall, etc. 13

With the high prevalence of seasonal mood problems and the limited daylight during winter in Northern Europe, SAD or subsyndromal SAD needs to be noted when analyzing the seasonal variation of psoriasis. 14 , 15 , 16

Lastly, the use of modern therapies makes it challenging to isolate the effects of seasonal variation. Since the introduction of topical steroids and methotrexate around 1958, these efficient treatments have been widely used and significantly modified the spontaneous disease. Also, retinoids, ciclosporin, PUVA (psoralen and ultraviolet A), and biological treatments have changed the course and status of moderate to severe psoriasis. Today many patients have achieved clear state psoriasis the whole year.

To review the medical evidence of seasonal influence on psoriasis, we aim to systematically evaluate Northern and Central European studies grouped before and after the introduction of topical steroids and later systemic treatments.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

References for this review were identified using the following index words in the PUBMED database: “psoriasis AND seasonal variation” and “psoriasis AND seasonality.” Supplementary searches were made in EMBASE, BIOSIS, and Cochrane to ensure enrolment of all relevant studies.

We included only studies from Northern and Central Europe to ensure that surveys used to illustrate the seasonal variation on psoriasis were comparable.

We independently assessed all publications. In a primary, screening titles and abstracts were inspected for further enrolment. In the secondary screening, full‐text versions of relevant articles were evaluated by study design, relevance, and country of origin. The reference lists of all enrolled articles were reviewed for additional articles of interest. With the purpose to find relevant material of older origin, a search for references from chosen articles, textbooks, and local libraries was performed. In this study, it was of major interest to include literature from before the introduction of topical corticoids and other modern therapies, so the effects from seasonal variation are less modified.

2.1. Measuring seasonal variation according to an evidence‐based methodology

Studies on psoriasis and seasonality follow very different protocols, and it is not possible to perform a statistical meta‐analysis. Therefore, the literature measuring seasonal variation was assessed using the Cochrane principles of ranking studies on therapies, disease prevention, and quality improvement operate with seven levels 17 (see Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Cochrane principles of ranking studies

| Study ranking | |

|---|---|

| I | A randomized controlled trial (RCT) that demonstrates a statistically significant difference in at least one important outcome (not possible to apply in this review). |

| II | An RCT that does not meet level I criteria (not possible to apply in this review). |

| III | A nonrandomized trial with contemporaneous controls selected by some systematic method (i.e., not selected by a perceived suitability for one of the treatment options for individual patients) or subgroup analysis of an RCT (not possible to apply in this review). |

| IV | Case series (of at least 10 patients) with historical controls or controls drawn from other studies. |

| V | Case series (at least 10 patients without controls) |

| VI | Case report (fewer than 10 patients) |

| VII | Expert opinion |

| Method used to specify design | |

|---|---|

| a | Cases measured with recognized standardized methods (quantitative) |

| b | Cases with measurable objective endpoints (quantitative). |

| c | Cases with a personal interview by the investigator (qualitative) |

| d | Cases based on questionnaires (qualitative) |

Surveys based on expert opinions were found of little value to this review and have been excluded. The RCT design does not apply to any prospective assessment of seasonal influence on psoriasis since a nonseason randomized controlled group cannot be established. Thus, studying psoriasis and seasonal variation, Cochrane ranking level IV would be the highest level of evidence that could be achieved.

It was noted if the purpose of the investigation was to search for seasonal variation, or if this variable was a smaller part of a larger investigation having another purpose.

3. RESULTS

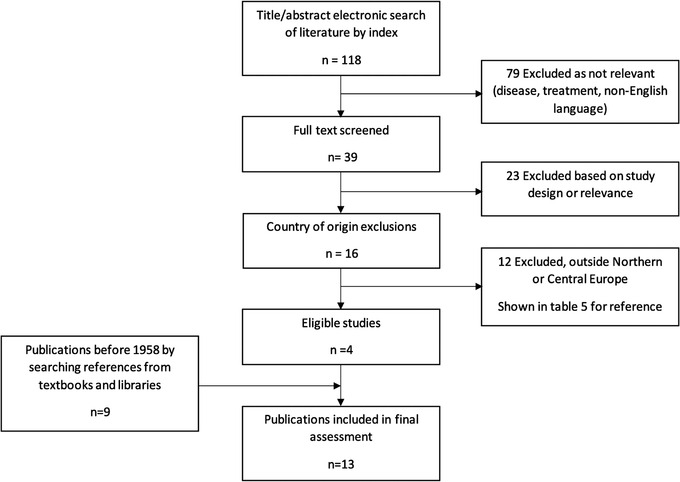

We identified 9 publications from the period before 1958, and 4 after 1958, which respected our study criteria (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart review procedure

Searching in EMBASE and BIOSIS led to no further publications of interest. No match was found by searching in the Cochrane library.

Tables 2 and 3 highlight the results from the included papers and the type of Cochrane ranking.

TABLE 2.

Results, Northern and Central European Studies before 1958, distribution of psoriasis relative to season in percentage

| Author, year, country | Sample size | Measure | Winter | Spring | Summer | Autumn | Method ranking a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nielsen 19 1892, Denmark | 782 | Cases treated | 29.5 | 22.1 | 21.5 | 26.9 | Vb |

| 77 | Disease onset | 35 | 23.4 | 23.4 | 18.2 | Vb | |

| 242 | Deterioration | 28.1 | 22.3 | 26.5 | 23.1 | Vb | |

| Krekeler 26 1912, Germany | 398 | Cases treated | 28 | 29 | 23 | 20 | Vb |

| Hanse 23 1916, Germany | 241 | Cases treated | 31 | 24 | 25 | 20 | Vb |

| Haxthausen 18 1924, Denmark | NA | Clinic visits through 10 years | Month of first visit was equally distributed throughout the year. | Vc | |||

| Hoede 24 1927, Germany | 154 | Disease onset | 22 | 30 | 21 | 27 | Vb |

| Deterioration | 37 | 25 | 23 | 14 | |||

| Hahnemann 21 1932, Germany | 470 | Cases treated | 23 | 26 | 29 | 22 | Vb |

| Müller 22 1933, Germany | 542 | Cases treated | 30 | 24 | 22 | 24 | Vb |

| Steinke 25 1935, Germany | 6708 | Cases treated | 24 | 26 | 25 | 25 | Vb |

| Disease onset | 25 | 27 | 21 | 27 | Vc | ||

| Weinsheimer 20 1937, Germany | 902 | Cases treated | 32.5 | 26.5 | 19.4 | 21.7 | Vb |

| 333 | Deterioration | 22 | 38 | 21 | 19 | Vc | |

Cochrane ranking of studies described in methods and materials, expressed in roman numbers. V: case series >10 patients, b: cases with measurable objective endpoints (quantitative), c: cases with a personal interview by the investigator (qualitative).

TABLE 3.

Results, Northern and Central European Studies after 1958, distribution of psoriasis relative to season in percentage

| Author, year, country | Sample size | Measure | Winter | Spring | Summer | Autumn | Method ranking b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Lomholt 12 1964, Faroe Islands |

206 a | Improvement | 21 | 1 | 63 | 15 | Vc |

| Deterioration | 25 | 52 | 15 | 8 | |||

|

Hellgren 9 1964, Sweden |

255 a | Improvement | 28.7 | NA | 22.6 | NA | Vc |

|

Könönen 28 1986, Finland |

1516 | Deterioration | 54 | 18 | 2 | NA | Vd |

|

Knopf 5 1989, Germany |

390 | Improvement | NA | NA | 60.5 | NA | Vd |

| Deterioration | 37.4 | 42.3 | NA | NA |

Only 50% of the interviewed patient experienced seasonal variation.

Cochrane ranking of studies described in methods and materials, expressed in roman numbers. V: case series >10 patients, c: cases with a personal interview by the investigator (qualitative), d: cases based on questionnaires (qualitative).

3.1. Studies from before 1958

In the case series with measurable endpoints, several factors have been used to describe seasonal variation. Haxthausen 18 used the month of the first visit, Nielsen 19 and Weinsheimer 20 the number of treated patients each month. The relative distribution of clinical visits was another measure of seasonal variation. 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 Although there might be some smaller variation among studies, showing a higher prevalence of psoriasis during winter, the overall tendency was close to equal distribution throughout the year. 19 , 20 , 23 In research of more qualitative measures, where the subjective perception of exacerbation of psoriasis is recorded, the results were quite the same. 19 , 25 , 26

In studies before 1958, there was no direct positive evidence for any seasonal variation of psoriasis 27 ; however, Table 2 shows slightly more treated patients and disease onset during winter, and higher rates of deterioration during spring.

3.2. Studies from after 1958

To study the subjective perception of the seasonality effect, Lomholt 12 examined and interviewed all psoriasis patients in the Faroe Islands, and Hellgren 9 interviewed psoriasis patients from the Department of Dermatology, Gothenborg, Sweden. In both cases, the number of patients experiencing no seasonal variation was about 50%. Of those who felt some kind of seasonality, summer seems to be the season for improvement 9 , 12 and spring the time for worsening. 12 Knopf stated that 60% have summer improvement. 5 Contradictory, Hellgren 9 observed a decline in disease onset during winter. He found fewer reported exacerbations in the winter months as well as April, May, July, and November, and more in March, June, August, September, and October. Könönen 28 reported that 54% of the most widespread activity was seen in the winter and only 2% in the summer, yet he also pointed out that a relatively high number of patients did not have any seasonal variation (see Table 3).

4. DISCUSSION

In the present review, the literature from before 1958 was considered more powerful in the study of spontaneous psoriasis not influenced by modern therapies. It appears from Table 2, including nine studies, that no convincing seasonal variation of psoriasis had been noted. In most cases, only hard measurable endpoints were used. However, from the old studies, it is not possible to deny a small statistical variation of seasonality in the direction of improvement in the summertime.

In the literature after 1958, only four studies were detected, however including self‐reported subjective assessments. Studies indicated seasonal variation in about half of the patients with improvement in the summer and possibly the autumn as the general trend. Interestingly, most authors agree that a smaller percentage directly experiences worsening in the summer. Using patient interviews or questionnaires in the more recent studies seem to confirm that there is clinically significant summer improvement.

Studies from outside Northern and Central Europe (see Table 4) agree that many patients have no or little seasonal variation, but many also have an improvement in the summer and a smaller group worsening. Improvement is supposed to be related to the sun. Improvement during summertime is in the global studies a consistent finding.

TABLE 4.

International studies after 1958 from outside Europe

| Author, year, country | Sample size | Methods | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Lane 29 1973, USA |

231 | Retrospective study of clinic visits over 2 years. Reported seasonal influence |

25% no seasonal influence 60.2% improvement in summer 14.3% deterioration in summer |

|

Farber 11 1974, USA |

5600 |

Questionnaire 47% response rate |

80% positive effect of sunlight 78% positive effect of warm weather |

|

Bedi 30 1977, India |

162 | Interview, clinic visits over a period of 2 years |

54% no seasonal variation 25% deterioration in winter and improvement in the summer |

|

Park 10 1998, South Korea |

870 | Questionnaire |

59% improvement in the summer 41% stationary/deterioration in the summer 65% deterioration in the winter 35% stationary/better in the winter |

|

Hancox 31 2004, USA |

NA | Clinic visits over a period of 8 years |

Astronomical calendar: Seasonal variation is not significant p = 0.07 (Winter: 30.6%, Spring: 28%, Summer: 20.3%, Autumn: 20%) Meteorological calendar: Seasonal variation is significant, p = 0.006 (spring 33.8%, fall 20.3%) |

|

Balato 32 2013, Italy |

300 | Consultation |

69.4% improved in summer, 13.2 deterioration 8.3% improved in autumn, 31.4 deterioration 1.6% improved in winter, 59.5% deterioration 15.7% improved in spring, 23.1% deterioration |

|

Kubota 33 2014, Japan |

565 903 |

Use of healthcare service Japanese National Database |

–0.3% (−0.5 to −0.1%) in hot season referenced to cold season Minimal seasonal difference |

| Ammar‐Khodja, 34 2015, North Africa | 373 |

Consultation Interview |

43% seasonal variation, not specified 79.4% stress as trigger of outbreak |

|

Kimball 35 2015, USA |

5468 |

Consultation Disease score |

16% visits in summer 25% visits in fall 31% visits in winter 28% visits in spring 20.4% cleared in summer 15.3% cleared in winter |

|

Harvell 36 2016, USA |

223 |

Skin samples Pathology bank Histology 15‐year retrospective study |

No seasonal variation |

|

Brito 37 2018, Brazil |

155 | Hospitalizations dermatology ward |

19% in summer 30% in autumn 27% in winter 25% in spring |

|

Wu 38 2020, China |

NA |

Google Trend Infodemiology data from Australia, New Zealand vs. USA, Canada, UK, Ireland, 2004–2018 |

Small but significant summer/autumn improvement in all countries Seasonal change followed the climate on the respective hemisphere |

The authors’ descriptions of seasonal variation indicate individual traits. Ethnicity and melanin pigmentation, of course, are bound to the person. The relation between Fitzpatrick skin type and seasonal variation seems not studied. Psoriasis patients are of different diagnostic types with individual characteristics relative to severity, outbreaks and, response to treatment. It is likely that seasonal influence on psoriasis also could be a personal characteristic. Following this view and guided by the literature review there may be different characteristic subsets of patients to season, for example, a larger group of about 50% of patients who are not influenced by season, a significant group who are improved in the summer, and a smaller group who do better in the winter. Some in the latter group directly are intolerant to the sun and experience a significant worsening in the summer. D‐vitamin levels are reduced in patients with psoriasis and arthritis but independent of season and latitudes, thus, seasonal variation in different subsets of psoriasis patients is unlikely to be attributed to the variable synthesis of D‐vitamin in the skin due to variable seasonal exposures to sunlight. 39 , 40

The concept of subsets of psoriasis patients relative to season automatically shall have implications for UVB therapy: Those with an improvement of psoriasis in summer are possible success candidates. Those with no seasonal variation may gain benefit from UVB, and those with worsening in summer may experience negative effects. A search of the literature has detected no precise study using seasonal variation as a measure of the UVB effectiveness on psoriasis. Climatotherapy given as a 4‐week intensive course at the Dead Sea in Israel is highly effective in nearly every patient selected for this treatment and a highly relevant experimental study on the effect of concentrated summer on psoriasis. 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 Climatotherapy also incorporates relief from stress and illustrates a combined effect. Thus, patients belonging to the subset of no seasonal variation under temperate climate conditions at home may when exposed to the Death Sea climate with aggressive use of sunlight experience major improvement or clearing, at the level of effectiveness from modern biologics.

This study of the literature suffers from limitations that it could not identify or eliminate the potential influence of mood, psyche, and SAD related to the season, which possibly influences the grade of psoriasis during seasons. Numerous other confounders are related to summers such as holidays, travels to other climate zones, leisure, and pleasant feel supporting mental well‐being ameliorating psoriasis.

In conclusion, the classical literature on psoriasis and season collected before modern therapies were introduced indicated no seasonal variation of psoriasis. Recent literature limited to Northern and Central Europe indicates that the seasonal effect on psoriasis has three clinical subsets: About 50% are not influenced by season, approximately 30% improve during summer, and about 20% do better in winter. A smaller group becomes significantly worse in summer. Changes of psoriasis relative to season shall be considered as an individual patient characteristic that may guidance the success of UVB light therapy. Observations from Europe are accordant with global observations covering different ethnicities and the northern and southern hemispheres and different climate extremes.

Jensen KK, Serup J, Alsing KK. Psoriasis and seasonal variation: A systematic review on reports from Northern and Central Europe—Little overall variation but distinctive subsets with improvement in summer or wintertime. Skin Res Technol. 2022;28:180–186. 10.1111/srt.13102

REFERENCES

- 1. Ameen M. Genetic basis of psoriasis vulgaris and its pharmacogenetic potential. J Eur Acad Dermatol. 2005;153:346–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gudjonsson JE, Elder JT. Psoriasis Epidemiology. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:535–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Plunkett A, Marks R. A review of the epidemiology of psoriasis vulgaris in the community. Australas J Dermatol. 1998;39:225–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schäfer T. Epidemiology of psoriasis. Review and the German perspective. Dermatology. 2006;212:327–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Knopf VB, Geyer A, Roth H, Barta U. Der Einfluss endogener und exogener Faktoren auf die Psoriasis Vulgaris –eine Klinische Studie. Dermatol Mon Schr. 1989;175:242–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Griffiths CEM, Richards HL. Psychological influences in psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:338–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. O´Leary CJ, Creamer D, Higgins E, Weinman J. Perceived stress, stress attributions and psychological distress in psoriasis. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57:465–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zachariae R, Zachariae H, Blomqvist K, Davidsson S, Molin L, Mørk C, Sigurgeirsson B. Self‐reported stress reactivity and psoriasis‐related stress of Nordic psoriasis suffers. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hellgren L. Psoriasis, a statistical, clinical and laboratory investigation of 255 psoriatics and matched healthy controls. Acta Derm Venereol. 1964;44:191–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Park BS, Youn JI. Factors influencing psoriasis: an analysis based upon the extent of involvement and clinical type. J Dermatol. 1998;25:97–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Farber EM, Nall ML. The natural history of psoriasis in 5600 patients. Dermatologica. 1974;148:1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lomholt G. Prevalence of skin diseases in a population; a census study from the Faroe Islands. Dan Med Bull. 1964;11:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Westring Å, Lam RW. Seasonal affective disorder: a clinical update. Anns Clin Psychiatry. 2007;19:239–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rastad C, Sjödén PO, Ulfberg J. High prevalence of self‐reported winter depression in a Swedish county. Psychiatry Clin Neurosc. 2005;59:665–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dam H, Jakobsen K, Mellerup E. Prevalence of winter depression in Denmark. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1998;97:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mersch PPA, Vastenburg NC, Meesters Y, Bouhuys AL, Beersma DGM, van den Hoofdakker RH, den Boer JA. The reliability and validity of the Seasonal Pattern Assessment Questionaire: a comparison between patient groups. J Affect. 2004;80:209–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Maibach HJ, Bashir SJ, McKibbon AN. Evidence‐Based Dermatology. BC Decker Inc., Hamilton London: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Haxthausen H. Om årstidernes indflydelse på forskellige hudsygdomme. Bibl Laeger. 1924;116:321–29. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nielsen L. Bidrag til kundskaben om Psoriasis. Dissertation. University of Copenhagen, København, 1892. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Weinsheimer E. Das Schicksal unserer Psoriasiskranken. Dissertation, Freiburg Universität, 1937. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hahnemann H. Beitrag zur Statistik der Psoriasis Vulgaris. Dissertation, Würtzburg Universität, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Müller AC. Zur Statistik der Psoriasis Vulgaris, auf grund der von 1926 bis 1930 in der Dermatologischen Klinik der Universität Leipzig behandelten Krankheitsfälle. Dissertation, Leipzig Universität, 1933. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hanse W. Zur Statistik der Psoriasis Vulgaris auf Grund der von 1920–25 in der Leipziger dermatologischen Klinik behandelten 241 Krankheitsfälle. Dissertation, Leipzig Universität, 1926. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hoede K. Beiträge zur Statistik, Aetiologie und Pathogenese der Psoriasis Vulgaris unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Erblichkeit. Dissertation, Würtzburg Universität, 1927. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Steinke A. Stellungsnahme zu umstrittenen fragen bei der Psoriasis Vulgaris. Dissertation, Berlin Universität, 1935. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Krekeler O. Beiträge zur statistik der Psoriasis Vulgaris. Dissertation, Leipzig Universität, 1912. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Romanus T. Psoriasis from a prognostic and hereditary point of view. Dissertation, Uppsala University, 1945. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Könönen M, Troppa J, Lassus A. An epidermeological survey of psoriasis in the Greater Helsinki area. Acta Dermato Venereol Suppl. 1986;124:3–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lane CG, Crawford GM. Psoriasis. A statistical study of 231 cases. Dermat Syph. 1937;35:1051–61. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bedi TR. Psoriasis in North India. Dermatologica. 1977;155:310–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hancox JG, Sheridan SC, Feldman SR, Fleisher AB Jr. Seasonal variation of dermatologic diseases in the USA: a study of office visits from 1990–1998. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:6–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Balato N, Di Constanzo L, Patruno C, Patrì A, Ayala F. Effect of weather and invironmental factors on the clinical course of psoriasis. Occup Environ Med. 2013;70:600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kubota K, Kamijima Y, Sato T, Ooba N, Koide D, Iizuka H, Nakagawa H. Epidemiology of psoriasis and palmoplantar pustulosis: a nationwide study using the Japanese national claims database. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ammar‐Khodja A, Benkaidali I, Bouadjar B, Serradj A, Titi A, Benchikhi H, et al. EPIMAG: international cross‐sectional epidemiological psoriasis study in the Maghreb. Dermatology. 2015;23:134–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kimball AB. Seasonal variation of acne and psoriasis: a 3‐year study using the physician global assessment scale. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:523–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Harvell JD, Selig DJ. Seasonal variations in dermatologic and dermapathologic diagnoses: a retrospective 15‐years analysis of dermatopathologic data. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:1115–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Brito LAR, Nascimento ACM, de Marque C, Moit HA. Seasonality of the hospitalization at a dermatologic ward (2007‐2017). An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:755–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wu Q, Xu Z, Zhao CN. Seasonality and global public interest in psoriasis: an infodemiology study. Postgrad Med J. 2020;96:139–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Touma Z, Eder L, Zisman D, Feld J, Chandran V, Rosen CF, et al. Seasonalvariation in vitamin D levels in psoriatic arthritis patients from different latitudes and its association with clinical outcomes. Arthrit Care Res. 2011;63:1440–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tuoma Z, Thavaneswaran A, Chandran V, Gladman DD. Does the change in season affect disease activity in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:1370–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Even‐Paz Z, Gumon R, Kipnis V, Abels DJ, Efron D. Dead Sea sun versus Dead Sea water in the treatment of psoriasis. J Dermatol Treat. 1996;7:83–6. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Snellman E, Lauharanta J, Reunanen A, Jansén CT, Jyrkinen‐Pakkasvirta T, Kallio M, et al. Effect of heliotherapy on skin and joint symptoms in psoriasis: a 6‐month follow‐up study. Br J Dermatol. 1993;128:172–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Snellman E, Aromaa A, Jansen CT, Lauharanta J, Reunanen A, Jyrkinen‐Pakkasvirta T, et al. Supervised four‐week heliotherapy alleviates the long‐term course of psoriasis. Acta Derm‐Venereol. 1993;73:388–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Harari, M. , David M, Friger M, Moses SW, et al., The percentage of patients achieving PASI 75 after 1 month and remission time after climatotherapy at the Dead Sea. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:1087–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Harari, M. , Czarnowicki T, Fluss R, Ingber A. Patients with early‐onset psoriasis achieve better results following Dead Sea climatotherapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:554–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]