Abstract

Background

Vellus hair is the fine, wispy hair found over most of the body surface, and the arrector pili muscles (hair muscle) serve to raise these hairs. Hair muscles are also critical for skin regeneration, contributing to the maintenance of stem cells in epidermis and hair follicles. However, little is known about their fundamental properties, especially their structure, because of the limitations of conventional two‐dimensional histological analysis.

Objectives

We aimed to quantitatively characterize the structure of vellus hair muscles by establishing a method to visualize the 3D structure of hair muscle.

Methods

We observed young female abdominal skin specimens by means of X‐ray micro CT and identified hair muscles in each cross‐sectional CT image. We then digitally reconstructed the 3D structure of the hair muscles on computer (digital‐3D skin), and numerically evaluated their structural parameters.

Results

Vellus hair muscles were clearly distinguished from the surrounding dermal layer in X‐ray micro CT images and were digitally reconstructed in 3D from those images for quantification of the structural parameters. The mean value of number of divisions of vellus hair muscles was 1.6, mean depth was 943.6 μm from the skin surface, mean angle to the skin surface was 28.8 degrees, and mean length was 1657.9 μm. These values showed relatively little variation among subjects. The mean muscle volume was approximately 20 million μm3 but showed greater variability than the other parameters.

Conclusion

Digital‐3D skin technology is a powerful approach to understand the tiny but complex 3D structure of vellus hair muscles. The fundamental nature of vellus hair muscles was characterized in terms of their 3D structural parameters, including number of divisions, angle to the skin surface, depth, and volume.

Keywords: 3D, arrector pili muscle, digital‐3D skin, hair follicle, hair muscle, vellus

1. INTRODUCTION

Arrector pili muscles (hair muscles) are smooth muscles located in the dermal layer that are connected to hair follicles. 1 They are innervated by the noradrenergic nervous system and contract under the stimulus of cold or emotional movement, inducing piloerection (“goose bumps”), which contributes to thermoregulation in animals with fur.

Since the hair muscles spread under sebaceous glands, contraction of hair muscles is also proposed to induce sebum secretion by squeezing the sebaceous glands, based on histological observations. 2 They may also have a role in maintaining the pilosebaceous unit (hair follicle, sebaceous gland, and hair muscle). 3 Hair muscles also contribute to maintaining vellus hair at the proper position, thereby contributing to the function of vellus hair as a critical sensor of physical stimulation (sense of touch). 4

Physiologically, hair muscles connect to the bulge area of hair follicles, which are regulated by hair follicle stem cells in that area via expression of nephronectin. 5 In contrast, a recent study indicated that hair muscles together with sympathetic nerves modulate hair follicle stem cell activity. 6 In androgenic alopecia, detachment of hair muscles from the hair follicles has been reported. 7 Moreover, the distal site of hair muscles binds to the epidermis, and this binding contributes to the maintenance of epidermal stem cells. 8 Thus, hair muscles could contribute to epidermal renewal and wound healing.

The structure of hair muscles has been studied histologically in scalp hair. The proximal terminal of the hair muscle binds to the bulge area of the hair follicle 9 via an elastic tendon. 10 The distal end of the hair muscle is located in the dermal layer close to the epidermis, 11 and some of the muscles are connected to the basal layer of the epidermis via integrin. 12 Classically, a single hair muscle had been considered to be associated with a single hair follicle, but recently it was proposed that a single hair muscle is shared by all follicles within a follicular unit (FU). 13 This may be consistent with the observation that the distal region of a hair muscle spreads, forming branches. 14

However, little is known about hair muscles at other body sites. The scalp hair is thick and long, while other body sites have thin short hair, known as vellus hair. As vellus hair is widely considered a matter of esthetic concern, various approaches have been developed to remove it, either chemically or physically. 15 , 16 Since hair muscles influence both hair and epidermal condition, understanding the structure of hair muscles in the face and body is important not only to enable efficient removal of unwanted vellus hair but also to maintain a healthy skin condition.

Conventionally, studies of hair muscle structure have employed histological, namely two‐dimensional (2D), methods. Although some researchers have attempted to reconstruct 3D structure from hundreds of serial 2D histological images, this involves technical difficulties. For example, the sections are mechanically pressed and deformed randomly, so that the reconstructed 3D image is not necessarily smooth or accurate. Therefore, hair muscles have not been fully characterized in terms of quantitative 3D structural parameters.

We have recently developed “digital‐3D skin” technology to analyze the ultrafine structure of skin by digitally reconstructing skin on computer from micro computed tomography (CT) observations. 17 In this technology, target structures are identified and classified with full spatial information, so that we can analyze skin freely, for example, structure sorting and digital anatomy. A key advantage is that since the observation is conducted by micro CT, the spatial information is both accurate and smooth. 18 , 19

In this study, we aimed to clarify the 3D structure of vellus hair muscles by applying this digital‐3D skin technology.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Skin samples

Ten samples of young (<40 years old) female abdominal skin were purchased from Biopredic International (Rennes, France), as surplus skin excised during plastic surgery; areas without stretch marks were used for observation. The background of the donors is summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the skin specimen donors

| Minimum | Maximum | Average | SEM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 22 | 39 | 32.2 | 1.7 |

| BMI | 20 | 29 | 24.8 | 0.9 |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index; SEM, scanning electron microscopy.

2.2. Micro CT observation of hair muscles and 3D reconstruction on computer

The X‐ray micro CT observation procedure was conducted as described in our previous report. 17 Briefly, skin specimens were cut into cubes of about 5 mm3 and observed by X‐ray micro CT under the following conditions: voltage 80 kV, current 100 microA, and resolution 2.6 micrometers (D200RSS270; Comscan Techno, Kanagawa, Japan). The scanning time was 2 h on average. Using the obtained images, hair muscles were segmented and reconstructed in 3D using Amira (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA).

2.3. Analysis of hair muscles

Hair muscles completely included in the observed area were evaluated. The measurements of hair muscle are shown as follows: for hair muscles with more than one division, the depth and angle are the average values, length is the maximum value, and the volume was calculated as the total value of all divisions.

2.4. Histological observation

Skin specimens were fixed, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 5 μm. The sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated through graded alcohols, and then stained with hematoxylin‐eosin. 20

3. RESULTS

3.1. Reconstruction of 3D structure of hair muscle on computer

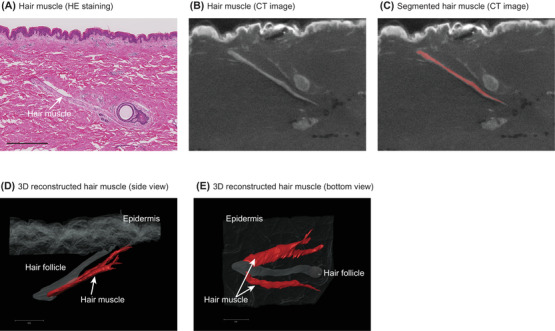

Hair muscle was clearly distinguished from the surrounding dermal layer on the CT images as a structure spreading from the hair follicle to the skin surface, in accordance with histological observations (Figure 1A–C). Epidermis and hair follicles were also identified on the CT images, and 3D images were digitally reconstructed (Figure 1D,E), with full spatial information. Subsequent analysis of hair muscle was done using the 3D data measured by micro CT.

FIGURE 1.

3D reconstruction of vellus hair muscle in body skin by means of microCT. (A) Vellus hair muscle (arrow) on hematoxylin‐eosin (HE)‐stained abdominal skin specimen. (B) Vellus hair muscle (arrow) on CT image. (C) Segmented vellus hair muscle on the CT image. 3D reconstructed vellus hair muscle: (D) side view and (E) bottom view

3.2. Structure of vellus hair muscle

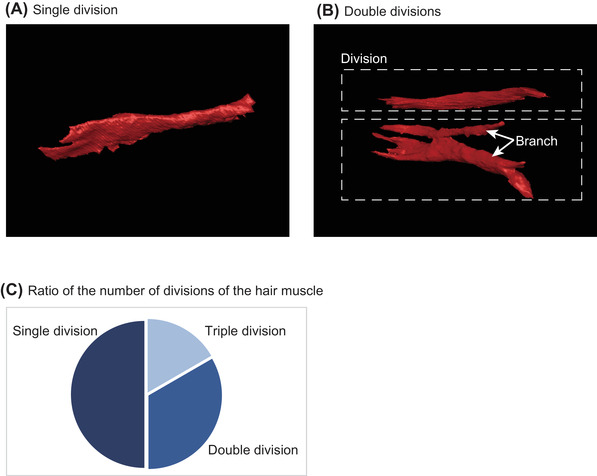

Vellus hair muscle connects to the hair and reaches to the epidermis. The distal terminal of vellus hair muscle did not appear to be connected to other hair follicles, in contrast to the case of scalp hair. 1 It has the same direction as the vellus hair above the skin surface, and thus we can predict the hair muscle direction from the orientation of the vellus hair. A single hair unit has one hair muscle consisting of one or more divisions (Figure 2A,B); the average number of divisions was 1.6 ± 0.2 (mean ± scanning electron microscopy [SEM]) (Figure 2C). Some of the divisions are split into two branches, which extend separately to the epidermis.

FIGURE 2.

Vellus hair muscle divisions. Bottom view of vellus hair muscle consisting of (A) single and (B) double divisions. Dotted rectangles show divisions with several branches. (C) Pie chart showing number of divisions of vellus hair muscles

3.3. Structural parameters of vellus hair muscle

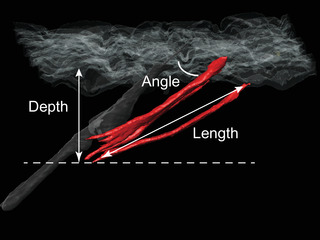

To define the spatial structure of hair muscles, we measured the parameters shown in Figure 3. Hair muscle originated from a mean depth of 943.6 ± 39.2 (mean ± SEM) μm, in the middle part of the dermal layer (Table 2). The mean length was 1657.9 ± 134.1 μm, and the muscles reached the epidermis at the angle of 28.8 ± 1.6 degrees. Similar values were obtained among all the subjects. This suggests that these structural parameters reflect the fundamental structure of vellus hair muscles. In contrast, the volume of hair muscle showed greater variation, with a mean value of 20 031 381.8 ± 4 508 356.9 (mean ± SEM) μm3.

FIGURE 3.

Structural parameters of vellus hair muscles. For hair muscles with more than one division, the depth and angle were the average values, length was the maximum values, and the volume was calculated as the total value of all divisions

TABLE 2.

Structural parameters of vellus hair muscles

| Minimum | Maximum | Average | SEM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depth (μm) | 721.8 | 1086.9 | 943.6 | 39.2 |

| Length (μm) | 948.4 | 2186.0 | 1657.9 | 134.1 |

| Volume (μm3) | 1 796 798.9 | 46 846 705.0 | 20 031 381.8 | 4 508 356.9 |

| Angle (degree) | 15.4 | 34.0 | 28.8 | 1.6 |

Abbreviation: SEM, scanning electron microscopy.

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, we used our digital‐3D skin technology to conduct a quantitative analysis of the structure of vellus hair muscles. This approach enabled us to determine the 3D structural parameters of vellus hair muscles in intact skin, overcoming some of the disadvantages of conventional 2D histological observation, such as uncertainty in evaluating the length, volume, and depth angle in the skin arising from the need to accurately assemble multiple successive 2D images of processed sections.

Various methods have been used to visualize and analyze the internal structure of skin. Recently, Wortsman 21 reported that hair muscle is detectable by means of ultrasonography. However, it is difficult to visualize the 3D structure, and the resolution of ultrasonography even with ultra‐high frequency ultrasound is at least one order of magnitude lower than that of micro CT (several tens of micrometers vs. micrometer order). 22 Focused ion beam‐SEM) can analyze the 3D structure of skin specimen at a subcellular level, 23 but it is difficult to cover the whole structure of the hair muscle. Our micro CT method also has a number of limitations: It uses X‐rays requiring specific facilities, is applicable only to excised skin samples, may damage samples after repeated measurements, and may have ethical limitations. Nevertheless, we think it represents a useful approach, especially for the quantitative measurement of the 3D structure of hair muscles.

Although the existence of hair muscles around the vellus hair follicles has been reported, 24 the properties of vellus hair muscles remain poorly understood. We previously reported the visualization of hair muscle, but measurements were based on 2D histological analysis. 25 Here, we obtained quantitative structural information, including the location, length, volume, angle to the skin surface, and number of divisions, for the first time. Although the number of divisions, depth, angle to the skin surface, and length of vellus hair muscles showed relatively little variation, the volume varied considerably. Thus, the basic structure of hair muscle appears to be common among subjects. Furthermore, the 3D structure of the vellus hair follicles on abdominal skin was similar to that of the scalp hair follicles, even though the thickness and the length of the hair are much smaller.

We also clarified the interaction of hair muscles with hair follicles in the body skin. In the case of scalp hair, the concept of an FU has been proposed, 26 namely one FU consists of several hair follicles, 14 and each hair muscle binds to several FUs in the scalp. However, in the abdominal skin, we found that a hair muscle binds to a single FU. This might be because the hair on abdominal skin is relatively sparse, making it difficult to connect several FUs to one vellus hair muscle, even though the fundamental components of FU are the same as in the scalp (sebaceous gland). Further, in scalp skin, hair follicles lose their connection to hair muscles in male and female pattern alopecia areata. 27 However, in healthy young abdominal skin, hair muscles are still connected, suggesting the importance of connection to the FU to maintain a healthy vellus hair condition. Although the differences of hair condition between body vellus and scalp hair have not yet been established, our 3D visualization method should be suitable to address this issue in the future.

Vellus hair muscles showed an angle of 28.8 degrees to the skin surface, which may play a role in maintaining vellus hair at an optimum orientation for sensing physical stimulation of the skin. 4 The similarity of orientation may also be beneficial to contract skin rapidly in response to cold or emotional stimulation to form goose bumps. Further, this orientation could also contribute to the formation of skin lines such as Langer's line used for surgical procedures. 28 Although body hair muscles bind to hair follicles similarly to scalp hair at the proximal site, the binding machinery to the epidermis remains unclear, as is the case for scalp hair muscle. 1 At the distal site, hair muscles are branched and connected to the papillary dermal layer, similarly to scalp hair. 11 Further study with higher resolution methods, such as 3D electron microscopy, are needed to overcome the issue of the low binding ratio, as suggested in the scalp study. 11

In conclusion, our study employs a new approach to quantitatively characterize the 3D structural properties of vellus hair muscles by employing digital‐3D skin based on micro CT imaging of skin samples. This enabled us to define the fundamental 3D structure of vellus hair muscle. Since hair muscle is important for skin regeneration and cosmetics, 29 our results are expected to be helpful for the development of clinical and esthetic treatments

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Ezure T, Amano S, Matsuzaki K. Quantitative characterization of 3D structure of vellus hair arrector pili muscles by micro CT. Skin Res Technol. 2022;28:689–694. 10.1111/srt.13168

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research data are not shared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Torkamani N, Rufaut NW, Jones L, Sinclair RD. Beyond goosebumps: does the arrector pili muscle have a role in hair loss? Int J Trichology. 2014;6(3):88–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Song WC, Hu KS, Kim HJ, Koh KS. A study of the secretion mechanism of the sebaceous gland using three‐dimensional reconstruction to examine the morphological relationship between the sebaceous gland and the arrector pili muscle in the follicular unit. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157(2):325–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Morioka K, Arai M, Ihara S. Steady and temporary expressions of smooth muscle actin in hair, vibrissa, arrector pili muscle, and other hair appendages of developing rats. Acta Histochem Cytochem. 2011;44(3):141–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Halata Z. Sensory innervation of the hairy skin (light‐ and electronmicroscopic study. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;101(1 Suppl):S75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fujiwara H, Ferreira M, Donati G, Marciano DK, Linton JM, Sato Y, et al. The basement membrane of hair follicle stem cells is a muscle cell niche. Cell. 2011;144(4):577–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shwartz Y, Gonzalez‐Celeiro M, Chen CL, Pasolli HA, Sheu S‐H, Fan SMY, et al. Cell types promoting goosebumps form a niche to regulate hair follicle stem cells. Cell. 2020;182(3):578–93.e519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Torkamani N, Rufaut NW, Jones L, Sinclair R. Destruction of the arrector pili muscle and fat infiltration in androgenic alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170(6):1291–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Torkamani N, Rufaut NW, Jones L, Sinclair R. Epidermal cells expressing putative cell markers in nonglabrous skin existing in direct proximity with the distal end of the arrector pili muscle. Stem Cells Int. 2016;2016:1286315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Barcaui CB, Pineiro‐Maceira J, de Avelar Alchorne MM. Arrector pili muscle: evidence of proximal attachment variant in terminal follicles of the scalp. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146(4):657–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Guerra Rodrigo F, Cotta‐Pereira G, David‐Ferreira JF. The fine structure of the elastic tendons in the human arrector pili muscle. Br J Dermatol. 1975;93(6):631–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Narisawa Y, Hashimoto K, Kohda H. Merkel cells participate in the induction and alignment of epidermal ends of arrector pili muscles of human fetal skin. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134(3):494–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mendelson JK, Smoller BR, Mendelson B, Horn TD. The microanatomy of the distal arrector pili: possible role for alpha1beta1 and alpha5beta1 integrins in mediating cell‐cell adhesion and anchorage to the extracellular matrix. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27(2):61–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Poblet E, Ortega F, Jimenez F. The arrector pili muscle and the follicular unit of the scalp: a microscopic anatomy study. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28(9):800–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Song WC, Hwang WJ, Shin C, Koh KS. A new model for the morphology of the arrector pili muscle in the follicular unit based on three‐dimensional reconstruction. J Anat. 2006;208(5):643–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aleem S, Majid I. Unconventional uses of laser hair removal: a review. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2019;12(1):8–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Casey AS, Goldberg D. Guidelines for laser hair removal. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2008;10(1):24–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ezure T, Amano S, Matsuzaki K. Aging‐related shift of eccrine sweat glands toward the skin surface due to tangling and rotation of the secretory ducts revealed by digital 3D skin reconstruction. Skin Res Technol. 2021;. 27:569–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim IG, Park SA, Lee SH, Choi JS, Cho H, Lee SJ, et al. Transplantation of a 3D‐printed tracheal graft combined with iPS cell‐derived MSCs and chondrocytes. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):4326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Messerli M, Aaldijk D, Haberthur D, Röss H, García‐Poyatos C, Sande‐Melón M, et al. Adaptation mechanism of the adult zebrafish respiratory organ to endurance training. PLoS One. 2020;15(2):e0228333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sato Y, Mukai K, Watanabe S, Goto M, Shimosato Y. The AMeX method. A simplified technique of tissue processing and paraffin embedding with improved preservation of antigens for immunostaining. Am J Pathol. 1986;125(3):431–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wortsman X, Carreno L, Ferreira‐Wortsman C, Poniachik R, Pizarro K, Morales C, et al. Ultrasound characteristics of the hair follicles and tracts, sebaceous glands, montgomery glands, apocrine glands, and arrector pili muscles. J Ultrasound Med. 2019;38(8):1995–2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Albano D, Aringhieri G, Messina C, De Flaviis L, Sconfienza LM. High‐frequency and ultra‐high frequency ultrasound: musculoskeletal imaging up to 70 MHz. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2020;24(2):125–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Klose M, Scheungrab M, Luckner M, Wanner G, Linder S. FIB‐SEM‐based analysis of Borrelia intracellular processing by human macrophages. J Cell Sci. 2021;134(5):jcs252320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Narisawa Y, Kohda H. Arrector pili muscles surround human facial vellus hair follicles. Br J Dermatol. 1993;129(2):138–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ezure T, Amano S, Matsuzaki K, Ohno N. New horizon in skincare targeting the facial‐morphology‐retaining dermal “dynamic belt”. IFSCC magazine. Forthcoming 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Headington JT. Transverse microscopic anatomy of the human scalp. A basis for a morphometric approach to disorders of the hair follicle. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120(4):449–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yazdabadi A, Whiting D, Rufaut N, Sinclair R. Miniaturized hairs maintain contact with the arrector pili muscle in alopecia areata but not in androgenetic alopecia: a model for reversible miniaturization and potential for hair regrowth. Int J Trichology. 2012;4(3):154–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Alhamdi A. Facial skin lines. Iraqi JMS. 2015;13(2):103–7. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kovacevic M, McCoy J, Goren A, Situm M, Stanimirovic A, Liu W, et al. Novel shampoo reduces hair shedding by contracting the arrector pili muscle via the trace amine‐associated receptor. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019;18(6):2037–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Research data are not shared.