Abstract

α-ketoglutarate is a key biomolecule involved in a number of metabolic pathways—most notably the TCA cycle. Abnormal α-ketoglutarate metabolism has also been linked with cancer. Here, isotopic labeling was employed to synthesize [1-13C,5-12C,D4]α-ketoglutarate with the future goal of utilizing its [1-13C]-hyperpolarized state for real-time metabolic imaging of α-ketoglutarate analyte and its downstream metabolites in vivo. The Signal Amplification By Reversible Exchange in Shield Enables Alignment Transfer to Heteronuclei (SABRE-SHEATH) hyperpolarization technique was used to create 9.7% [1-13C] polarization in 1 minute in this isotopologue. The efficient 13C hyperpolarization, which utilizes parahydrogen as the source of nuclear spin order, is also supported by favorable relaxation dynamics at 0.4 μT field (the optimal polarization-transfer field): The exponential 13C polarization buildup constant Tb is 11.0±0.4 s, versus the 13C polarization decay constant T1 of 18.5±0.7 s. An even higher 13C polarization value of 17.3% was achieved using natural-abundance α-ketoglutarate disodium salt, with overall similar relaxation dynamics at 0.4 μT field, indicating that substrate deuteration leads only to a slight increase (~1.2-fold) in the relaxation rates for 13C nuclei separated by three chemical bonds. Instead, the gain in polarization (natural abundance versus [1-13C]-labeled) is rationalized through the smaller heat capacity of the “spin bath” comprising available 13C spins that must be hyperpolarized by the same number of parahydrogen present in each sample—in line with previous 15N SABRE-SHEATH studies. Remarkably, the C-2 carbon was not hyperpolarized in both α-ketoglutarate isotopologues studied; this observation is in sharp contrast with previously reported SABRE-SHEATH pyruvate studies, indicating that the catalyst-binding dynamics of C-2 in α-ketoglutarate differ from that in pyruvate. We also demonstrate that 13C spectroscopic characterization of α-ketoglutarate and pyruvate analytes can be performed at natural 13C abundance with estimated detection limit of 80 micromolar concentration×*%P13C. All in all, the fundamental studies reported here enable a wide range of research communities with a new hyperpolarized contrast agent potentially useful for metabolic imaging of brain function, cancer, and other metabolically challenged diseases.

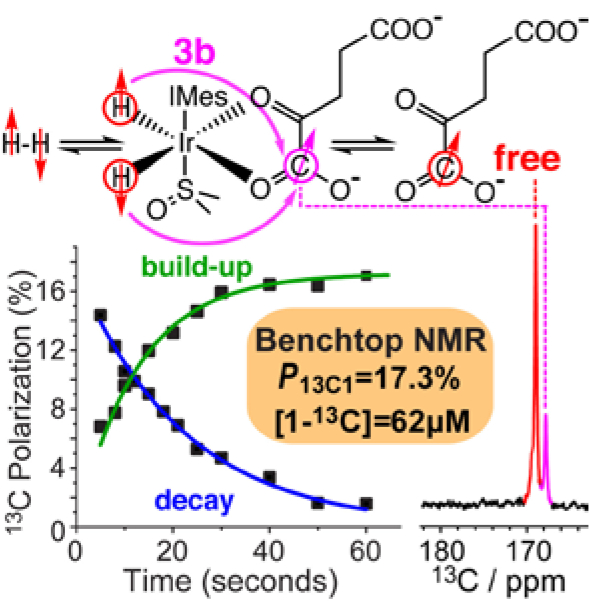

Graphical Abstract

The detection sensitivity of NMR techniques is directly proportional to the degree of nuclear spin alignment of the samples with the applied static magnetic field, i.e., the nuclear spin polarization (P).1 Because equilibrium P is very low (≤10−5) even in high-field MRI scanners (e.g., 3 T), MRI is regarded as a low-sensitivity technique in the context of real-time in vivo metabolic studies.2 The advent of non-equilibrium approaches to enhance P far beyond thermal equilibrium all the way to the order unity allows boosting NMR sensitivity by 4+ orders of magnitude (also termed hyperpolarization), thereby enabling in vivo tracking of relatively dilute metabolites (0.1–10 mM) such as [1-13C]pyruvate,3 [1-13C]lactate,4 [13C]bicarbonate5 and other hyperpolarized (HP) 13C injectable biocompatible molecules.6 The 13C carboxylic nucleus offers long T1 (on the order of 1 minute, therefore enabling in vivo tracking for up to several minutes.7 One hyperpolarization technology, dissolution Dynamic Nuclear Polarization (d-DNP),8 is already under investigation in 29 clinical trials (www.clinicaltrials.gov) to identify efficacy of HP 13C MRI for detecting aberrant metabolism of HP [1-13C]pyruvate in diseases.9 Despite the success of d-DNP in research settings to be able to provide safe, injectable HP 13C contrast agents for clinical utilization, this technology has a number of limitations including high device cost (>$2M) and slow production speed (≥1h for clinical device) that potentially pose barrier to translation for widespread clinical use.10 Lower cost and higher throughput hyperpolarization techniques are desirable to address these challenges.11–12

Another alternative group of HP techniques that has been developed over the years relies of the parahydrogen (p-H2) as a source of hyperpolarization.13 Historically, parahydrogen induced polarization (PHIP)13–14 relying on pairwise p-H2 addition was developed first, and translated to in vivo application approximately 15 years after the initial in vitro demonstration.15 Because this approach relies on the use of a PHIP catalyst required for p-H2 pairwise addition, it needs to be removed prior to potential clinical use. Moreover, hydrogenation reactions can be performed directly in aqueous media16–17 to facilitate biocompatible contrast agent preparation. Alternatively, hydrogenation in organic solvents followed by reconstitution into biocompatible aqueous buffer media has also been demonstrated.18–20 A wide range of biocompatible HP molecular probes has been developed and translated in vivo21–22 23–24 using this technique including most prominently HP [1-13C]pyruvate25 via a PHIP variant involving side arm hydrogenation (PHIP-SAH). The key advantages of the PHIP-SAH approach are fast hyperpolarization times (<1 min), and low costs of HP hardware. The key limitation of this method is the requirement of chemical modification of the to-be-hyperpolarized substrate through hydrogenation reactions, as well as the need for additional chemical de-esterification of the side arm after 13C nuclei have been hyperpolarized.12, 26–27

Signal Amplification By Reversible Exchange28 in SHield Enables Alignment Transfer to Heteronuclei (SABRE-SHEATH)29 is an alternative technique to create HP [1-13C]pyruvate.30–31 This method relies on simultaneous exchange of p-H2 and a to-be-hyperpolarized substrate (e.g., [1-13C]pyruvate) with a metal complex (e.g., Ir-IMes hexacoordinate complex, e.g., 3b in Scheme 1) to enable spontaneous polarization transfer from p-H2-derived hydrides to spin-spin-coupled heteronuclei (e.g., 13C of [1-13C]pyruvate30–31). SABRE-SHEATH was first demonstrated for 15N,29 and then quickly expanded to 13C,32 19F,33 31P,34 and other nuclei. In 2019, Duckett and co-workers demonstrated the feasibility of SABRE-SHEATH hyperpolarization of [1-13C]pyruvate using DMSO as a co-ligand, but 13C polarization levels were limited to 1.85%.30, 35 The addition of DMSO leads to the formation of SABRE-active complex and 3b (Scheme 1); note that axial positions are not exchanging on the time scale of the SABRE-SHEATH experiment, and therefore, only complex 3b undergoes effectively reversible exchange with the HP substrate. The key advantages of the SABRE-SHEATH hyperpolarization approach are the low cost of HP hardware (<$20k) and rapid (~1 min) hyperpolarization process.36 Moreover, this HP technique does not modify the to-be-HP substrate.37–38 Since HP [1-13C]pyruvate is the leading HP contrast agent, the reader is reminded that d-DNP performs hyperpolarization of [1-13C]pyruvic acid, which is chemically modified to sodium [1-13C]pyruvate via a neutralization reaction. The key limitation of SABRE is that it is most efficient in alcohol solutions, e.g., in methanol, which has poor bio-compatibility.12 Pioneering efforts to produce aqueous solutions of HP compounds via SABRE have improved this issue but so far have led to marked (by an order of magnitude or more) P decrease.39–44 Development of bio-compatible formulations for agents hyperpolarized via SABRE technology remains a key unaddressed translational need, which is outside the scope of this manuscript. The reader is also directed to several recent reviews for detailed descriptions of leading HP technologies.9, 12, 26–27, 45–46

Scheme 1.

Formation of [IrCl(H)2(DMSO)2(IMes)] (2) and [Ir(H)2(η2-substrate)(DMSO)(IMes)] (3) complexes following activation of [IrIMes(COD)Cl] (1) pre-catalyst. Catalyst 1 was prepared previously50 according to Cowley et al.51 The species 1, 2, 3a and 3b are as indicated by Iali et al. for pyruvate variants.30 R = CH3 for pyruvate and R = CH2-CH2-COO− for α-KG.

We and others have recently demonstrated a series of innovations (including the use of water as an additional potential co-ligand,47–48 and temperature cycling37, 49) demonstrating that catalyst-bound [1-13C]pyruvate 13C polarization (P13C) may reach order-unity values,47 and 13C bulk P13C of up to 13% can be obtained.

The work presented here aims to expand efficient SABRE-SHEATH hyperpolarization to other biologically relevant ketocarboxylic acids, exemplified by α-ketoglutarate. α-ketoglutarate is a central intermediate of the tricarboxylic acid cycle and other important metabolic pathways.52 Moreover, HP [1-13C]α-ketoglutarate ([1-13C]α-KG) prepared by d-DNP has been successfully employed to delineate altered metabolism in the isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) gene mutant. Therefore, HP [1-13C]α-KG can inform on IDH1 status via detection of the metabolic product HP [1-13C]2-hydroxyglutarate ([1-13C]2HG), which is missing in wild-type cells.53 IDH1 mutants are potentially druggable.53 Accordingly, HP 13C MRI with HP [1-13C]α-KG can inform on IDH1 mutation, and thus, has the potential to guide cancer patient treatment.53

A pioneering study employing HP [1-13C]α-ketoglutarate showed that the HP resonance of metabolic product ([1-13C]2HG may overlap with the natural-abundance HP resonance from the 13C-5 carbon of [1-13C]α-KG. To mitigate this potential translational challenge of spectral overlap, Miura and co-workers have recently synthesized [1-13C,5-12C]α-KG and employed this HP isotopologue for detecting HP [1-13C]2HG in IDH1 mutants without natural-abundance HP 13C-5 background signal.54 Taglang and co-workers have also demonstrated that late-stage deuteration of HP carboxylic acids can extend carboxylate 13C T1 by up to a factor of 4.55 That work indicated that 13C HP metabolic probes or in vivo analytes could generally benefit from deuteration to improve the lifetime of the 13C HP state of the molecular probe.55

Inspired by the previous works, we have synthesized [1-13C,5-12C,D4]α-KG, Scheme 2. Here, we have hyperpolarized two α-KG isotopologues to study their utility for SABRE-SHEATH: natural-abundance α-KG and newly developed [1-13C,5-12C,D4]α-KG depicted in Scheme 1.

Scheme 2.

Overall synthetic schematic of [1-13C,5-12C,D4]α-KG. See Supporting Information (SI) for details of experimental procedure and characterization details.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The standard pre-catalyst used for SABRE, [IrCl(COD)(IMes)](IMes=1,3-bis(2,4,6-trimethylphenyl)imidazol-2-ylidene; COD=cyclooctadiene)],51, 56 catalyst 1 (6 mM) was activated with p-H2 bubbling in the presence of ~5 mM α-KG, 20 mM DMSO and 0.5 M H2O in CD3OD (Figure 1, top), corresponding to our previously optimized protocol for preparation of HP [1-13C]pyruvate (P13C=13%).47 We used a low α-KG concentration (5 mM) because of the low α-KG solubility in CD3OD. Fast activation (<5 mins) leads to the formation of species 2, 3a and 3b in accord with the notation introduced by Duckett and co-workers (in the context of pyruvate SABRE).30–31 Complex 3b is the primary SABRE-active species as discussed above. For natural-abundance substrate studies, we have also performed a comparative study with pyruvate.

Figure 1.

a) Schematic of SABRE-SHEATH hyperpolarization process and relevant polarization transfer path of [1-13C,5-12C,D4]α-KG. b) 13C spectrum of HP [1-13C,5-12C,D4]α-KG; carbon positions are labeled by blue numerals. c) Representative stacked variable-temperature 13C spectra of 5 mM [1-13C,5-12C,D4]α-KG demonstrating the interplay between HP complex 3b and the “free” peak as a function of temperature during the SABRE-SHEATH hyperpolarization process; d) corresponding 13C spectrum of thermally polarized neat [1-13C]acetic acid employed as signal reference for computation of signal enhancements. e) Build-up and decay of total 13C polarization of 13C-1 (i.e., integrating over all bound and free resonances) in [1-13C,5-12C,D4]α-KG at BT=0.42 μT; f) corresponding 13C-1 T1 relaxation curves at the Earth’s and the clinically-relevant 1.4 T field of the benchtop spectrometer. Total 13C polarization of 13C-1 in [1-13C,5-12C,D4]α-KG as a function of temperature (g) and magnetic transfer field (h). All experiments are performed at 1.4 T using a SpinSolve NMR spectrometer in CD3OD at TT=+10 °C (unless otherwise noted).

13C SABRE-SHEATH experiments were performed similarly to the recently reported study for [1-13C]pyruvate47 by bubbling >98.5% p-H257 at a flow rate of 70 standard cubic centimeters per minute (sccm) at 8 atm p-H2 partial pressure for 2 min. Parahydrogen was temporarily stored (1–4 days) in aluminum cylinders using the storage and distribution system described in detail in the SI. 13C signal detection was performed using a clinically relevant 1.4 T field. The thermally polarized sample of neat (~17.5 M) [1-13C]acetic acid (Figure 1d) was employed as a signal reference to compute 13C polarization enhancement and P13C (see SI).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Simultaneous exchange of p-H2 and α-KG leads to hyperpolarization of the 1-13C site detected in both isotopologues, Figs. 1,2(a,b). The temperature sweep (Figs. 1c,g and Fig. 2f) reveals that at cold temperatures (e.g., −12 °C), HP species 3b dominates the spectral intensity. The HP free (i.e., not catalyst bound) is negligible compared to the HP 3b resonance because the substrate exchange is too slow on the time scale of the experiment.47 SABRE-SHEATH polarization at elevated temperature leads to the rise of the resonances from HP free species with an optimal polarization transfer temperature TT of 6–10 °C, Figs. 1g,2f, for both isotopologues studied. At this temperature, the exchange rate of the substrate is likely matched to the size of the spin-spin coupling between the parahydrogen-derived hydrides and the 13C-1 nucleus. A field sweep revealed a P13C maximum at BT of ~0.42 μT (Figs. 1f, 2g).

Figure 2.

a) Schematic of SABRE-SHEATH hyperpolarization process and relevant polarization transfer path of natural-abundance α-KG; carbon positions are labeled by blue numerals. b) Representative HP 13C spectrum of 5.6 mM natural-abundance α-KG obtained by performing SABRE-SHEATH at +10 °C in CD3OD at 1.4 T; c) corresponding 13C spectrum of thermally polarized neat [1-13C]acetic acid; d) Total (bound+free) 13C polarization build-up and decay at BT=0.42 μT and TT=+10 °C; e) Total (bound+free) 13C polarization decay at the Earth’s field and 1.4 T. Total 13C polarization of 13C-1 in natural abundance α-KG as a function of temperature (f) and magnetic transfer field (g). All experiments are performed at 1.4 T using a SpinSolve NMR spectrometer in CD3OD.

The high P13C level allows detecting dilute biomolecules with high SNR at natural 13C abundance (ca. 1.1%) even using a benchtop NMR spectrometer, which is remarkable as it substantially expands the capability of the demonstrated approach to potentially screen a wide range of new metabolic analytes that could be amenable to NMR hyperpolarization. Indeed, Figure 2b shows a spectrum of HP α-KG with a corresponding signal reference spectrum (neat [1-13C]acetic acid) shown in Figure 2c. We estimate the detection limit of 5 μM at the reported polarization level or ~80 μM*%polarization of 13C.

Just like in Figure 1, the microtesla relaxation dynamics of the 13C-1 carbon of natural abundance isotopologue (Figure 2d) shows that the total P13C (bound+free) build-up time (Tb=12.8±0.5 s) is substantially shorter that the corresponding T1 value of 22.4±0.8 s, indicating that the P13C build-up rate substantially exceeds the rate of spin polarization destruction via T1 relaxation (note the bound 3b and free species likely have different intrinsic 13C T1 values (mostly because the catalyst itself is a relaxation agent), but since their exchange rate is substantially faster than 1/T1, then one should observe “the same” average 13C T1 for both lines that would be weighted by the mole fractions of each site under some set of conditions—hence, the current simplified analysis of our relaxation data). These favorable relaxation dynamics fundamentally enable relatively high P13C levels. Indeed, P13C of up to 17.3% was observed for natural-abundance α-KG (Fig. 2b). Somewhat lower maximum P13C values were observed for [1-13C,5-12C,D4]α-KG (e.g., Fig. 1b) even though the relaxation dynamics at BT = 0.42 μT is effectively similar in the labeled isotopologue (Tb=11.0±0.4 s and T1=18.5±0.8 s respectively, Fig. 1e). Instead, we explain the P13C increase in the naturally abundant isotopologue in terms of the smaller heat capacity of the “spin bath” comprising available 13C spins that must be hyperpolarized by the same number of p-H2 spins.58 Indeed, corresponding 15N SABRE-SHEATH studies with isotopically enriched metronidazole and natural abundance metronidazole revealed substantially greater P15N in the natural abundance compound59–60 versus fully labeled analogue.61–62 Future work on improving p-H2 access to the polarization-transfer complex may potentially yield much better P13C levels in HP [1-13C,5-12C,D4]α-KG.

The observation of similar 13C-1 Tb and T1 values measured at 0.42 μT of the two α-KG isotopologues is also remarkable in the context of exchangeable substrate deuteration. Deuterium is a quadrupolar nucleus that may potentially act as a source of relaxation for the nearby spins due to enhanced scalar relaxation of the second kind.31, 63–64. Therefore, potentially deleterious effects of deuterium on 13C-1 T1 (and by extension, on the maximum attainable P13C-1 due to the increased rate of spin destruction) may be expected in a manner similar to that observed for 15N T1 relaxation arising from 15N-14N two-bond interactions (where 14N spins act as quadrupolar relaxation sinks).62 We rationalize the above observation by the negligible strength of the relevant interactions over three (13C-C-C-D) chemical bonds. Indeed, the corresponding 15N-C-C-14N three-bond interactions have also been shown to be too weak to have a measurable effect of microtesla 15N relaxation in SABRE-SHEATH.65

This observation of only a minor effect of γ-position deuteration on 13C-1 T1 relaxation is important in the context of attaining high 13C-1 polarization levels because it implies that such substrate deuteration may cause no undesirable rapid 1-13C-1 depolarization in microtesla magnetic fields (and by extension, may not interfere with achieving high P13C-1 values because the spin destruction rate remains lower than the polarization build-up rate). On the other hand, substrate deuteration will likely have a positive impact on extending 1-13C T1 in α-KG at clinically relevant magnetic fields (particularly in the absence of the SABRE catalyst).55 Of note, 13C-1 T1 values (e.g., 54.4±2.3 s at 1.4 T and 39.6±1.1 s at the Earth’s field, Figure 1f) are likely limited by the interplay of the Iridium-catalyst induced- and exchange-induced T1 relaxation processes. This notion is supported by the substantially longer 13C-1 T1 values even at the higher (and more clinically relevant) 3 T field and in aqueous media (with no SABRE catalyst): e.g., 97.1±0.4 s for [1-13C,5-12C,D4]α-KG—note that the non-deuterated isotopologue yields substantially lower 13C-1 T1 at 3 T of 63.0±0.8 s, clearly demonstrating the potential clinical translation benefit of substrate deuteration for HP metabolic 13C studies.

We also note that 13C T1 values at the Earth’s field and higher fields are substantially greater than those at the sub-microtesla magnetic fields employed here for polarization build-up as part of the (static-field) SABRE-SHEATH process. Therefore, other polarization-transfer approaches operating at higher magnetic fields (including but not limited to LIGHT-SABRE,66 SLIC-SABRE,67 QUASR-SABRE-SHEATH,68 pulsed SABRE-SHEATH,69 alt SABRE-SHEATH,70 etc.71–72) may potentially perform polarization build-up with overall lower 13C T1 losses and thus may yield overall higher P13C values—future work is certainly warranted in this direction.

Remarkably, no resonance from the HP 13C-2 carbon was detected from either isotopologue (expected between 200 and 210 ppm, see e.g. the spectrum in Figure 2b). This observation is somewhat unexpected, because the spin-spin couplings between parahydrogen-derived hydrides and the 13C-2 site are overall expected to be similar to those of the 13C-1 site, Figure 2a. Moreover, no HP 13C-5 resonance was observed either, suggesting that catalyst coordination with the other carboxyl group does not take place. Prompted by this unexpected lack of 13C-2 hyperpolarization in both α-KG isotopologues, we have performed corresponding studies with natural abundance pyruvate at similar (8.6 mM) pyruvate concentration and otherwise the same sample preparation and experimental conditions, Figure 3.

Figure 3.

a) Schematic of SABRE-SHEATH hyperpolarization process and relevant polarization transfer path of natural-abundance sodium pyruvate; carbon positions are labeled by blue numerals. b) Representative HP 13C spectrum of 8.6 mM natural-abundance sodium pyruvate obtained by performing SABRE-SHEATH at +10 °C in CD3OD at 1.4 T; c) corresponding 13C spectrum of thermally polarized neat [1-13C]acetic acid; d) Total (bound+free) 13C polarization build-up and decay at BT=0.42 μT and TT=+10 °C; e) Total (bound+free) 13C polarization decay at the Earth’s field and 1.4 T. Total 13C polarization of 13C-1 in sodium pyruvate as a function of temperature (f) and magnetic transfer field (g). All experiments are performed at 1.4 T using a SpinSolve NMR spectrometer in CD3OD.

Figure 3b shows the spectrum of HP pyruvate with P13C-1 of 25.5% and P13C-2 of 5.3%, indeed revealing a remarkable difference in the polarization values of the two binding sites, Figure 3a. The systematic temperature sweeping of the SABRE-SHEATH polarization conditions (Figure 3f) shows nearly identical position of the maximum for P13C-1 of and P13C-2 at 6–10 °C. Moreover, the microtesla magnetic field sweep (Figure 3f) revealed that optimum BT for 13C-2 is slightly smaller (~0.20 μT) versus that for 13C-1 (~0.42 μT), indicating that the spin-spin interactions between p-H2-derived hydrides and 13C-2 are ~1.5-times weaker than those for 13C-1 site. Furthermore, the relaxation analysis of pyruvate 13C-1 and 13C-2 sites at 0.42 μT reveals no substantial differences between the two sites, indicating that the minute difference in the rates of polarization build-up and decay for the two molecular sites during the SABRE-SHEATH process cannot explain the remarkable 4–5-fold difference in the P13C-1 and P13C-2. It should also be noted that the studies at natural 13C abundance level allow probing all 13C sites independently, due to low probability (1.1%) of having 13C in both positions at the same time. Taking together the key presented observations, we hypothesize that 13C-2 in pyruvate coordinates the iridium complex (Figure 3a) weaker due to side-chain dynamics induced by the –CH3 group—and as a result, the residence lifetime of the bound 13C-2 site on the catalyst maybe reduced, in turn resulting in reduced P13C and lower value of optimal BT. In the case of α-KG, the side chain is substantially longer than the –CH3 group of pyruvate, leading to more deleterious effects—more specifically, the complete lack of observable 13C-2 polarization in both α-KG isotopologues studied. An additional contribution may arise from coherent leakage from 13С−2 via spin-spin coupling with the nearby protons in protonated systems: at the magnetic fields used, these protons can strongly couple to the 13C-2 site and hence exchange of magnetization could occur.73–74 Future site-specific hyperpolarization-EXSY experiments75 for determination of dissociation rates in SABRE complexes and computational studies are certainly warranted to support or rule out the presented side-chain and coherent leakage hypotheses to explain the presented observations.

The maximum reported P13C values for α-KG and pyruvate in their natural abundance form were 17.3% and 25.5% respectively at the time of the detection, and the actual achieved polarization values (inside the apparatus) are likely a few percent higher (the reader is reminded that the produced P13C decays during the sample shuttling from the polarizer to the NMR detector). These values were achieved through rigorous optimization of matching magnetic field to establish spontaneous polarization transfer and temperature that modulates the rates of simultaneous p-H2 and to-be-hyperpolarized substrate chemical exchange, Figures 2 and 3. While P13C values can be potentially further improved, we anticipate that the gains will likely come from the use of higher p-H2 pressure and flow rates, which have been shown previously to improve access to fresh p-H2, i.e., the source of hyperpolarization.58, 76 The reported studies have been performed at 8 atm, i.e., at the maximum pressure rating for 5 mm NMR tubes employed in our apparatus. Therefore, to achieve these additional potential gains, the design of a specialized hyperpolarizer operating at substantially higher p-H2 pressure and flow rate will be required. Such HP purpose-built setups have been reported for hydrogenative PHIP studies,26, 77–79 and we hope that this report will stimulate the development of corresponding instrumentation for SABRE polarization.

The optimum values of BT and TT (and maximum total P13C) for 13C-1 in α-KG isotopologues are nearly identical to those of [1-13C]pyruvate reported recently,47 indicating that our SABRE-SHEATH polarization transfer approach may be universally tailored to this structural motif of α-ketocarboxylate in other biologically relevant biomolecules, such as [1-13C]α-ketoisocaproate.80

The main biomedical limitation of the presented study is production of HP substrate in an alcohol-based solution in the presence of an iridium-based catalyst, which may be considered toxic.81 While the iridium level employed here would likely not impact future feasibility studies in rodents, it would certainly need to be reduced by 2–3 orders of magnitude for clinical use. Several approaches have been recently demonstrated to capture iridium catalyst from SABRE-hyperpolarized solutions.81–84 Moreover, heterogeneous SABRE approaches have been demonstrated to produce HP compounds free from catalyst.85–86 In the context of methanol content of HP samples, it certainly needs to be substantially diluted (or preferably removed completely) for future in vivo studies. One way to achieve bio-compatible SABRE-based formulation of HP contrast agent is the use of water-soluble SABRE catalyst approaches, which have also been demonstrated to produce HP compounds in aqueous media to mitigate the use of toxic alcohols.39, 41, 43–44 However, the achieved P13C levels using aqueous media have generally been at least an order of magnitude lower than those in methanol (and thus not suitable for in vivo applications, where a high degree of P13C is needed), which has dampened enthusiasm for this approach. The development of bio-compatible HP contrast agents’ SABRE-based formulations is an active area of research investigations in our partnering and other laboratories, and we anticipate that this report will further stimulate work in that direction.

CONCLUSION

In summary, 13C SABRE-SHEATH enables efficient hyperpolarization (P13C of up to 17.3%) of 13C-1 in two α-KG isotopologues: the natural abundance variant and [1-13C,5-12C,D4]α-KG. [1-13C,5-12C,D4]α-KG is designed as a next-generation molecular probe to sense real-time metabolism of α-KG in vivo using NMR hyperpolarization. This isotopologue is (1) 13C labeled in position 1 for spectroscopic sensing, (2) per-deuterated to maximize the lifetime of the 13C-1 HP state in aqueous media at 3 T; and (3) 12C labeled in position 5 to minimize background signal from this resonance. Complete deuteration of γ- and δ- positions has only a minor impact on 13C-1 relaxation in the microtesla fields under our conditions, indicating that spin-spin interactions between 13C-1 and remote protons/deuterons sites and corresponding contributions to 13C-1 relaxation are effectively negligible under these conditions. In contrast, no HP signals from 13C-2 spins were detected from α-KG, and substantially reduced 13C-2 polarization was detected in the shorter pyruvate molecule—we hypothesize that the binding of the 13C-2 site is generally weaker than that of 13C-1 due to random motion of the side chain (-CH3 in pyruvate and –CH2-CH2-COO- in α-KG). Of critical importance in the context of biomedical utility of HP α-KG as a molecular probe, SABRE-SHEATH hyperpolarization process leads to highly specific polarization of 13C-1 site with no detectable polarization on any other sites and most notably 13C-5. This polarization specificity provides a clear benefit over d-DNP, which is non-site specific polarization technique, and which yields natural-abundance HP 13C-5 α-KG, which overlaps with HP [1-13C]2HG metabolic signal produced via metabolism of HP 13C-1 α-KG in IDH1 mutants.54 Future systematic experimental and computational binding studies are certainly warranted to obtain a better understanding of relaxation dynamics in these important biomolecules, with the goal to further improve accessible 13C polarization for biomedical applications. We have also presented the feasibility of studying HP substrates at natural 13C abundance (1.1%) using a benchtop NMR spectrometer—indeed, meaningful information was readily obtained at 13C concentrations below 100 μM 13C concentration. The utility of natural abundance studies in the context of benchtop NMR spectroscopy allows studying a wide range of substrates without 13C isotopic enrichment for 13C SABRE-SHEATH hyperpolarization in a chemistry laboratory, without the need for sample transportation to a high-field NMR facility. As a result, we anticipate that the scope of amendable substrates (and laboratories) to SABRE-SHEATH can be rapidly expanded.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by the NSF under grants CHE-1904780 and CHE-1905341, NIH R21CA220137, NIBIB R01EB029829. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. T.T. also acknowledges funding from the Mallinckrodt Foundation. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, NIH. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

BMG, EYC declare stake ownership in XeUS Technologies, LTD. TT holds stock in Vizma Life Sciences LLC.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

Additional experimental details of SABRE hyperpolarization studies; additional details of synthesis and spectral characterization; additional figures; detailed description of p-H2 storage and distribution system including bill of materials (file type, PDF).

REFERENCES

- (1).Hoult DI; Richards RE The signal-to-noise ratio of the nuclear magnetic resonance experiment. J. Magn. Reson. 1976, 24, 71–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Bluml S; Moreno-Torres A; Shic F; Nguy CH; Ross BD Tricarboxylic acid cycle of glia in the in vivo human brain. NMR Biomed. 2002, 15, 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Golman K; in’t Zandt R; Thaning M Real-time metabolic imaging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006, 103, 11270–11275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Day SE; Kettunen MI; Gallagher FA; Hu DE; Lerche M; Wolber J; Golman K; Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH; Brindle KM Detecting tumor response to treatment using hyperpolarized C-13 magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 1382–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Merritt M; Harrison C; Storey C; Jeffrey F; Sherry A; Malloy C Hyperpolarized C-13 allows a direct measure of flux through a single enzyme-catalyzed step by NMR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007, 104, 19773–19777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Golman K; Ardenkjær-Larsen JH; Petersson JS; Månsson S; Leunbach I Molecular imaging with endogenous substances. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003, 100, 10435–10439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Kurhanewicz J; Vigneron DB; Brindle K; Chekmenev EY; Comment A; Cunningham CH; DeBerardinis RJ; Green GG; Leach MO; Rajan SS, et al. Analysis of cancer metabolism by imaging hyperpolarized nuclei: Prospects for translation to clinical research Neoplasia 2011, 13, 81–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH; Fridlund B; Gram A; Hansson G; Hansson L; Lerche MH; Servin R; Thaning M; Golman K Increase in signal-to-noise ratio of > 10,000 times in liquid-state NMR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003, 100, 10158–10163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Kurhanewicz J; Vigneron DB; Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH; Bankson JA; Brindle K; Cunningham CH; Gallagher FA; Keshari KR; Kjaer A; Laustsen C, et al. Hyperpolarized 13C MRI: Path to clinical translation in oncology. Neoplasia 2019, 21, 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Nikolaou P; Goodson BM; Chekmenev EY NMR hyperpolarization techniques for biomedicine. Chem. Eur. J. 2015, 21, 3156–3166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Kovtunov KV; Pokochueva EV; Salnikov OG; Cousin S; Kurzbach D; Vuichoud B; Jannin S; Chekmenev EY; Goodson BM; Barskiy DA, et al. Hyperpolarized NMR: D-DNP, PHIP, and SABRE. Chem. Asian J. 2018, 13, 1857–1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Hövener J-B; Pravdivtsev AN; Kidd B; Bowers CR; Glöggler S; Kovtunov KV; Plaumann M; Katz-Brull R; Buckenmaier K; Jerschow A, et al. Parahydrogen-based hyperpolarization for biomedicine. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 11140–11162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Bowers CR; Weitekamp DP Transformation of symmetrization order to nuclear-spin magnetization by chemical-reaction and nuclear-magnetic-resonance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1986, 57, 2645–2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Eisenschmid TC; Kirss RU; Deutsch PP; Hommeltoft SI; Eisenberg R; Bargon J; Lawler RG; Balch AL Parahydrogen induced polarization in hydrogenation reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 8089–8091. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Golman K; Axelsson O; Johannesson H; Mansson S; Olofsson C; Petersson JS Parahydrogen-induced polarization in imaging: Subsecond C-13 angiography. Magn. Reson. Med. 2001, 46, 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Hövener J-B; Chekmenev EY; Harris KC; Perman W; Robertson L; Ross BD; Bhattacharya P PASADENA hyperpolarization of 13C biomolecules: Equipment design and installation. Magn. Reson. Mater. Phy. 2009, 22, 111–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Goldman M; Johannesson H; Axelsson O; Karlsson M Hyperpolarization of C-13 through order transfer from parahydrogen: A new contrast agent for MFI. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2005, 23, 153–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Cavallari E; Carrera C; Aime S; Reineri F Studies to enhance the hyperpolarization level in PHIP-SAH-produced C13-pyruvate. J. Magn. Reson. 2018, 289, 12–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Reineri F; Boi T; Aime S Parahydrogen induced polarization of 13C carboxylate resonance in acetate and pyruvate. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 5858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Knecht S; Blanchard JW; Barskiy D; Cavallari E; Dagys L; Van Dyke E; Tsukanov M; Bliemel B; Münnemann K; Aime S, et al. Rapid hyperpolarization and purification of the metabolite fumarate in aqueous solution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2021, 118, e2025383118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Zacharias NM; McCullough CR; Wagner S; Sailasuta N; Chan HR; Lee Y; Hu J; Perman WH; Henneberg C; Ross BD, et al. Towards real-time metabolic profiling of cancer with hyperpolarized succinate. J. Mol. Imaging Dyn. 2016, 6, 123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Bhattacharya P; Chekmenev EY; Reynolds WF; Wagner S; Zacharias N; Chan HR; Bünger R; Ross BD Parahydrogen-induced polarization (PHIP) hyperpolarized MR receptor imaging in vivo: A pilot study of 13C imaging of atheroma in mice. NMR Biomed. 2011, 24, 1023–1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Bhattacharya P; Chekmenev EY; Perman WH; Harris KC; Lin AP; Norton VA; Tan CT; Ross BD; Weitekamp DP Towards hyperpolarized 13C-succinate imaging of brain cancer. J. Magn. Reson. 2007, 186, 150–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Coffey AM; Shchepin RV; Truong ML; Wilkens K; Pham W; Chekmenev EY Open-source automated parahydrogen hyperpolarizer for molecular imaging using 13C metabolic contrast agents. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 8279–8288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Cavallari E; Carrera C; Sorge M; Bonne G; Muchir A; Aime S; Reineri F The 13C hyperpolarized pyruvate generated by parahydrogen detects the response of the heart to altered metabolism in real time. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Schmidt AB; Bowers CR; Buckenmaier K; Chekmenev EY; de Maissin H; Eills J; Ellermann F; Glöggler S; Gordon JW; Knecht S, et al. Instrumentation for hydrogenative parahydrogen-based hyperpolarization techniques. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 479–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Reineri F; Cavallari E; Carrera C; Aime S Hydrogenative-PHIP polarized metabolites for biological studies. Magn. Reson. Mater. Phy. 2021, 34, 25–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Adams RW; Aguilar JA; Atkinson KD; Cowley MJ; Elliott PIP; Duckett SB; Green GGR; Khazal IG; Lopez-Serrano J; Williamson DC Reversible interactions with para-hydrogen enhance NMR sensitivity by polarization transfer. Science 2009, 323, 1708–1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Theis T; Truong ML; Coffey AM; Shchepin RV; Waddell KW; Shi F; Goodson BM; Warren WS; Chekmenev EY Microtesla SABRE enables 10% nitrogen-15 nuclear spin polarization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 1404–1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Iali W; Roy SS; Tickner BJ; Ahwal F; Kennerley AJ; Duckett SB Hyperpolarising pyruvate through signal amplification by reversible exchange (SABRE). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 10271–10275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Tickner BJ; Semenova O; Iali W; Rayner PJ; Whitwood AC; Duckett SB Optimisation of pyruvate hyperpolarisation using SABRE by tuning the active magnetisation transfer catalyst. Catal. Sci. Tech. 2020, 10, 1343–1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Barskiy DA; Shchepin RV; Tanner CPN; Colell JFP; Goodson BM; Theis T; Warren WS; Chekmenev EY The absence of quadrupolar nuclei facilitates efficient 13C hyperpolarization via reversible exchange with parahydrogen. ChemPhysChem 2017, 18, 1493–1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Shchepin RV; Goodson BM; Theis T; Warren WS; Chekmenev EY Toward hyperpolarized 19F molecular imaging via reversible exchange with parahydrogen. ChemPhysChem 2017, 18, 1961–1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Zhivonitko VV; Skovpin IV; Koptyug IV Strong 31P nuclear spin hyperpolarization produced via reversible chemical interaction with parahydrogen. Chem. Comm. 2015, 51, 2506–2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Rayner PJ; Duckett SB Signal amplification by reversible exchange (SABRE): From discovery to diagnosis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 6742–6753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).TomHon PM; Han S; Lehmkuhl S; Appelt S; Chekmenev EY; Abolhasani M; Theis T A versatile compact parahydrogen membrane reactor. ChemPhysChem 2021, 22, 2526–2534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).TomHon P; Abdulmojeed M; Adelabu I; Nantogma S; Kabir MSH; Lehmkuhl S; Chekmenev EY; Theis T Temperature cycling enables efficient 13C SABRE-SHEATH hyperpolarization and imaging of [1-13C]-pyruvate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 282–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Green RA; Adams RW; Duckett SB; Mewis RE; Williamson DC; Green GGR The theory and practice of hyperpolarization in magnetic resonance using parahydrogen. Prog. Nucl. Mag. Res. Spectrosc. 2012, 67, 1–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Shi F; He P; Best QA; Groome K; Truong ML; Coffey AM; Zimay G; Shchepin RV; Waddell KW; Chekmenev EY, et al. Aqueous NMR signal enhancement by reversible exchange in a single step using water-soluble catalysts. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 12149–12156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Spannring P; Reile I; Emondts M; Schleker PPM; Hermkens NKJ; van der Zwaluw NGJ; van Weerdenburg BJA; Tinnemans P; Tessari M; Blümich B, et al. A new Ir-NHC catalyst for signal amplification by reversible exchange in D2O. Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 9277–9282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Truong ML; Shi F; He P; Yuan B; Plunkett KN; Coffey AM; Shchepin RV; Barskiy DA; Kovtunov KV; Koptyug IV, et al. Irreversible catalyst activation enables hyperpolarization and water solubility for NMR signal amplification by reversible exchange. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 18 13882–13889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Zeng H; Xu J; McMahon MT; Lohman JAB; van Zijl PCM Achieving 1% NMR polarization in water in less than 1 min using sabre. J. Magn. Reson. 2014, 246, 119–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Hövener J-B; Schwaderlapp N; Borowiak R; Lickert T; Duckett SB; Mewis RE; Adams RW; Burns MJ; Highton LAR; Green GGR, et al. Toward biocompatible nuclear hyperpolarization using signal amplification by reversible exchange: Quantitative in situ spectroscopy and high-field imaging. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 1767–1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Colell JFP; Emondts M; Logan AWJ; Shen K; Bae J; Shchepin RV; Ortiz GX; Spannring P; Wang Q; Malcolmson SJ, et al. Direct hyperpolarization of nitrogen-15 in aqueous media with parahydrogen in reversible exchange. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 7761–7767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Eills J; Budker D; Cavagnero S; Chekmenev EY; Elliott SJ; Jannin S; Lesage A; Matysik J; Meersmann T; Prisner T, et al. Spin hyperpolarization in modern magnetic resonance. ChemRxiv 2022, 10.26434/chemrxiv-2022-p7c9r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH On the present and future of dissolution-dnp. J. Magn. Reson. 2016, 264, 3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Adelabu I; TomHon P; Kabir MSH; Nantogma S; Abdulmojeed M; Mandzhieva I; Ettedgui J; Swenson RE; Krishna MC; Theis T, et al. Order-unity 13C nuclear polarization of [1–13C]pyruvate in seconds and the interplay of water and SABRE enhancement. ChemPhysChem 2022, 23, 131–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Tickner BJ; Lewis JS; John RO; Whitwood AC; Duckett SB Mechanistic insight into novel sulfoxide containing SABRE polarisation transfer catalysts. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 15198–15206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Chapman B; Joalland B; Meersman C; Ettedgui J; Swenson RE; Krishna MC; Nikolaou P; Kovtunov KV; Salnikov OG; Koptyug IV, et al. Low-cost high-pressure clinical-scale 50% parahydrogen generator using liquid nitrogen at 77 K. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 8476–8483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Barskiy DA; Kovtunov KV; Koptyug IV; He P; Groome KA; Best QA; Shi F; Goodson BM; Shchepin RV; Coffey AM, et al. The feasibility of formation and kinetics of NMR signal amplification by reversible exchange (SABRE) at high magnetic field (9.4 T). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 3322–3325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Cowley MJ; Adams RW; Atkinson KD; Cockett MCR; Duckett SB; Green GGR; Lohman JAB; Kerssebaum R; Kilgour D; Mewis RE Iridium N-heterocyclic carbene complexes as efficient catalysts for magnetization transfer from parahydrogen. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 6134–6137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Morris JP; Yashinskie JJ; Koche R; Chandwani R; Tian S; Chen C-C; Baslan T; Marinkovic ZS; Sánchez-Rivera FJ; Leach SD, et al. Α-ketoglutarate links P53 to cell fate during tumour suppression. Nature 2019, 573, 595–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Chaumeil MM; Larson PEZ; Yoshihara HAI; Danforth OM; Vigneron DB; Nelson SJ; Pieper RO; Phillips JJ; Ronen SM Non-invasive in vivo assessment of IDH1 mutational status in glioma. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Miura N; Mushti C; Sail D; AbuSalim JE; Yamamoto K; Brender JR; Seki T; AbuSalim DI; Matsumoto S; Camphausen KA, et al. Synthesis of [1-13C-5-12C]-alpha-ketoglutarate enables noninvasive detection of 2-hydroxyglutarate. NMR Biomed. 2021, 34, e4588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Taglang C; Korenchan DE; von Morze C; Yu J; Najac C; Wang S; Blecha JE; Subramaniam S; Bok R; VanBrocklin HF, et al. Late-stage deuteration of 13C-enriched substrates for T1 prolongation in hyperpolarized 13C MRI. Chem. Comm. 2018, 54, 5233–5236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Vazquez-Serrano LD; Owens BT; Buriak JM The search for new hydrogenation catalyst motifs based on N-heterocyclic carbene ligands. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2006, 359, 2786–2797. [Google Scholar]

- (57).Nantogma S; Joalland B; Wilkens K; Chekmenev EY Clinical-scale production of nearly pure (>98.5%) parahydrogen and quantification by benchtop NMR spectroscopy. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 3594–3601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Shchepin RV; Truong ML; Theis T; Coffey AM; Shi F; Waddell KW; Warren WS; Goodson BM; Chekmenev EY Hyperpolarization of “neat” liquids by NMR signal amplification by reversible exchange. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 1961–1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Barskiy DA; Shchepin RV; Coffey AM; Theis T; Warren WS; Goodson BM; Chekmenev EY Over 20% 15N hyperpolarization in under one minute for metronidazole, an antibiotic and hypoxia probe. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 8080–8083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Fekete M; Ahwal F; Duckett SB Remarkable levels of 15N polarization delivered through SABRE into unlabeled pyridine, pyrazine, or metronidazole enable single scan NMR quantification at the mM level. J. Phys. Chem. B 2020, 124, 4573–4580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Shchepin RV; Birchall JR; Chukanov NV; Kovtunov KV; Koptyug IV; Theis T; Warren WS; Gelovani JG; Goodson BM; Shokouhi S, et al. Hyperpolarizing concentrated metronidazole 15NO2 group over six chemical bonds with more than 15% polarization and 20 minute lifetime. Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 8829–8836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Birchall JR; Kabir MSH; Salnikov OG; Chukanov NV; Svyatova A; Kovtunov KV; Koptyug IV; Gelovani JG; Goodson BM; Pham W, et al. Quantifying the effects of quadrupolar sinks via 15N relaxation dynamics in metronidazoles hyperpolarized via SABRE-SHEATH. Chem. Comm. 2020, 56, 9098–9101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Bernatowicz P; Kubica D; Ociepa M; Wodyński A; Gryff-Keller A Scalar relaxation of the second kind. A potential source of information on the dynamics of molecular movements. 4. Molecules with collinear C–H and C–Br bonds. J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118, 4063–4070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Blanchard JW; Sjolander TF; King JP; Ledbetter MP; Levine EH; Bajaj VS; Budker D; Pines A Measurement of untruncated nuclear spin interactions via zero- to ultralow-field nuclear magnetic resonance. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 92, 220202. [Google Scholar]

- (65).Salnikov OG; Chukanov NV; Svyatova A; Trofimov IA; Kabir MSH; Gelovani JG; Kovtunov KV; Koptyug IV; Chekmenev EY 15N NMR hyperpolarization of radiosensitizing antibiotic nimorazole via reversible parahydrogen exchange in microtesla magnetic fields. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 2406–2413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Theis T; Truong M; Coffey AM; Chekmenev EY; Warren WS LIGHT-SABRE enables efficient in-magnet catalytic hyperpolarization. J. Magn. Reson. 2014, 248, 23–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Pravdivtsev AN; Skovpin IV; Svyatova AI; Chukanov NV; Kovtunova LM; Bukhtiyarov VI; Chekmenev EY; Kovtunov KV; Koptyug IV; Hövener J-B Chemical exchange reaction effect on polarization transfer efficiency in SLIC-SABRE. J. Phys. Chem. A 2018, 122, 9107–9114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Theis T; Ariyasingha NM; Shchepin RV; Lindale JR; Warren WS; Chekmenev EY Quasi-resonance signal amplification by reversible exchange. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 6136–6142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Tanner CPN; Lindale JR; Eriksson SL; Zhou Z; Colell JFP; Theis T; Warren WS Selective hyperpolarization of heteronuclear singlet states via pulsed microtesla SABRE. J. Chem. Phys. 2019, 151, 044201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Pravdivtsev AN; Kempf N; Plaumann M; Bernarding J; Scheffler K; Hövener J-B; Buckenmaier K Coherent evolution of signal amplification by reversible exchange in two alternating fields (alt-SABRE). ChemPhysChem 2021, 22, 2381–2386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Eriksson SL; Lindale JR; Li X; Warren WS Improving SABRE hyperpolarization with highly nonintuitive pulse sequences: Moving beyond avoided crossings to describe dynamics. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabl3708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Dagys L; Bengs C; Levitt MH Low-frequency excitation of singlet–triplet transitions. Application to nuclear hyperpolarization. J. Chem. Phys. 2021, 155, 154201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Gemeinhardt ME; Limbach MN; Gebhardt TR; Eriksson CW; Eriksson SL; Lindale JR; Goodson EA; Warren WS; Chekmenev EY; Goodson BM “Direct” 13C hyperpolarization of 13C-acetate by microtesla NMR signal amplification by reversible exchange (SABRE). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 418–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Chukanov NV; Salnikov OG; Shchepin RV; Svyatova A; Kovtunov KV; Koptyug IV; Chekmenev EY 19F hyperpolarization of 15N-3-19F-pyridine via signal amplification by reversible exchange. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 23002–23010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Hermkens NKJ; Feiters MC; Rutjes FPJT; Wijmenga SS; Tessari M High field hyperpolarization-EXSY experiment for fast determination of dissociation rates in SABRE complexes. J. Magn. Reson. 2017, 276, 122–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Truong ML; Theis T; Coffey AM; Shchepin RV; Waddell KW; Shi F; Goodson BM; Warren WS; Chekmenev EY 15N hyperpolarization by reversible exchange using SABRE-SHEATH. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 8786–8797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Schmidt AB; Berner S; Schimpf W; Müller C; Lickert T; Schwaderlapp N; Knecht S; Skinner JG; Dost A; Rovedo P, et al. Liquid-state carbon-13 hyperpolarization generated in an MRI system for fast imaging. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Agraz J; Grunfeld A; Li D; Cunningham K; Willey C; Pozos R; Wagner S Labview-based control software for para-hydrogen induced polarization instrumentation. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2014, 85, 044705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).Hövener J-B; Chekmenev EY; Harris KC; Perman W; Tran T; Ross BD; Bhattacharya P Quality assurance of PASADENA hyperpolarization for 13C biomolecules. Magn. Reson. Mater. Phy. 2009, 22, 123–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (80).Tickner BJ; Ahwal F; Whitwood AC; Duckett SB Reversible hyperpolarization of ketoisocaproate using sulfoxide-containing polarization transfer catalysts. ChemPhysChem 2021, 22, 13–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (81).Manoharan A; Rayner P; Iali W; Burns M; Perry V; Duckett S Achieving biocompatible SABRE: An in vitro cytotoxicity study. ChemMedChem 2018, 13, 352–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (82).Barskiy DA; Ke LA; Li X; Stevenson V; Widarman N; Zhang H; Truxal A; Pines A Rapid catalyst capture enables metal-free para-hydrogen-based hyperpolarized contrast agents. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 2721–2724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (83).Kidd BE; Gesiorski JL; Gemeinhardt ME; Shchepin RV; Kovtunov KV; Koptyug IV; Chekmenev EY; Goodson BM Facile removal of homogeneous SABRE catalysts for purifying hyperpolarized metronidazole, a potential hypoxia sensor. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 16848–16852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (84).Mewis RE; Fekete M; Green GGR; Whitwood AC; Duckett SB Deactivation of signal amplification by reversible exchange catalysis, progress towards in vivo application. Chem. Comm. 2015, 51, 9857–9859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (85).Shi F; Coffey AM; Waddell KW; Chekmenev EY; Goodson BM Heterogeneous solution NMR signal amplification by reversible exchange. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 7495–7498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (86).Kovtunov KV; Kovtunova LM; Gemeinhardt ME; Bukhtiyarov AV; Gesiorski J; Bukhtiyarov VI; Chekmenev EY; Koptyug IV; Goodson BM Heterogeneous microtesla SABRE enhancement of 15N NMR signals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 10433–10437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.