Abstract

There have been many surveys of genetic variation in BRCA1 and BRCA2 to identify variant prevalence and catalogue population specific variants, yet none have evaluated the magnitude of unobserved variation. We applied species richness estimation methods from ecology to estimate “variant richness” and determine how many germline pathogenic BRCA1/2 variants have yet to be identified and the frequency of these missing variants in different populations. We also estimated the prevalence of germline pathogenic BRCA1/2 variants and identified those expected to be most common. Data was obtained from a literature search including studies conducted globally that tested the entirety of BRCA1/2 for pathogenic variation. Across countries, 45% to 88% of variants were estimated to be missing, i.e., present in the population but not observed in study data. Estimated variant frequencies in each country showed a higher proportion of rare variants compared to recurrent variants. The median prevalence estimate of BRCA1/2 pathogenic variant carriers was 0.64%. BRCA1 c.68_69del is likely the most recurrent BRCA1/2 variant globally due to its estimated prevalence in India. Modeling variant richness using ecology methods may assist in evaluating clinical targeted assays by providing a picture of what is observed with estimates of what is still unknown.

Introduction

BRCA1 and BRCA2 are among the most studied human genes, with many thousands of variants in each gene defined and dozens of populations surveyed. Although studies report on pathogenic variants observed, none have evaluated what is potentially missing in these surveys. Understanding pathogenic variation in these genes is important because these variants increase risk for several cancers including breast, ovarian, prostate, and pancreatic [1]. Knowledge about carrier status has useful clinical implications, as individuals who learn about their pathogenic variation early through genetic testing can engage in more frequent screening to increase the odds of early cancer detection and undergo prophylactic surgery to decrease future cancer risk.

Many recent studies have estimated the overall prevalence of pathogenic BRCA1/2 variant carriers in specific populations. Population genetic screening studies in the United States have reported prevalence estimates ranging from 0.5% to 0.7% [2–4]. Higher prevalence has been seen among Ashkenazi Jewish populations, reaching 2% [2]. These estimates provide insight into the burden of BRCA1/2-related hereditary cancer and indicate that the number of individuals who might benefit from genetic testing and subsequent preventive measures is substantial. However, less is known about the prevalence of BRCA1/2 pathogenic variant carriers in other populations around the world.

Understanding the types of pathogenic BRCA1/2 variation in a given population can also be useful for informing genetic screening strategies. For instance, if certain pathogenic variants are found more commonly in a particular population, this can lead to the development of population-specific screening strategies [5, 6]. Alternatively, if there appears to be a wide range of variation, more comprehensive sequencing may better detect pathogenic variant carriers. There have been extensive efforts of large consortia to understand the global spectrum of pathogenic BRCA1/2 variants, including the most recurrent variants in different regions around the globe [7, 8]. However, many statistical analyses of these results are limited by inconsistencies in ascertainment strategies, variant testing methods, and an inability to account for variation that has not yet been observed.

The purpose of this study was to model the prevalence of germline pathogenic BRCA1/2 variants in different populations around the world and predict their allele frequency spectrum. Specifically, we sought to determine how many germline pathogenic BRCA1/2 variants have yet to be identified in well-studied countries and how common unreported variants are in their respective populations. We also compiled a list of the most recurrent observed variants in several countries. Given the clinical significance of BRCA1/2, it is important to understand the number of people who may benefit from genetic testing and what spectrum of pathogenic variants should be expected in different places around the world.

Materials and methods

Data sources

PubMed was used to search for studies published between January 1999 and March 2020 that involved screening individuals for pathogenic variants in BRCA1 and BRCA2. Search terms included “BRCA1”, “BRCA2”, “breast cancer”, “ovarian cancer”, “population screening”, “gene sequencing”, and “direct sequencing”. The resulting studies and their references were examined and only those that tested the entirety of these genes for pathogenic variation were included in later analyses. Studies that targeted specific variants or that used methods capable of detecting only a subset of variants were excluded. For our analyses, variants were classified as pathogenic using classifications from individual studies based on ACMG PVS1 criteria for dominant hereditary breast and ovarian cancer risk in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes or likely pathogenic or pathogenic classifications in ClinVar [9]. The following accession version numbers were used for BRCA1 and BRCA2, respectively: NM_007294.3 and NM_000059.3. Detailed search and selection procedures are shown in S1 Fig.

Unique variant estimation methods

We sought to apply species richness estimation methods from field ecology to estimate the number of unique pathogenic variants in a given gene that are present in a population and the relative frequency of these variants. Briefly, species methods look at the number of unique species and their frequencies in a sample of the environment to estimate the total number of unique species in the same environment. “Species” can be defined broadly (e.g., words in a book, bugs in software programs, alleles in genetic code), so these methods have many applications [10]. Underlying assumptions of species richness estimate methods are [11–13]:

Individual representatives of a species are independently and randomly sampled from a population.

Species are distributed uniformly in a specific catchment area.

Species distributions can be mathematically defined.

For all practical purposes, similar assumptions apply for estimating the total number of unique variants from a population sample of variants: 1) Most variant assessment studies are blind to variant status before sequencing. To further meet this assumption in our analysis, if multiple individuals from the same family were sequenced, only one individual was selected for inclusion. Additionally, data was included from studies performing sequencing rather than targeted testing to meet the criteria of random ascertainment. 2) Population substructure is always present in human populations and ecology. Since human populations are relatively large and variant status is unknown before sequencing, variant estimates should perform as well as species estimates with regards to this assumption. For our purposes, we used country as a catchment area given its public health relevance and because most study samples focused on a particular country. 3) We illustrate below that variant distributions follow patterns similar to species distributions.

There are several specific methods for estimating species richness, each with different strengths and different parameters for modeling distributions [14]. The Chao 1984 method [15] is a relatively simple and straightforward method that has been shown to give an accurate lower bound estimate. It assumes that variants (or species) that occur rarely provide the most information about the number of missing variants (or species). Importantly, this method only uses singletons and doubletons for estimation, so it breaks down when no doubletons occur [16]. We used the Chao method to estimate a lower bound of the total number of unique variants.

There are also several maximum likelihood methods for predicting species richness. Literature on maximum likelihood methods has shown that these give more accurate estimates but can be sensitive to input parameters. The penalized nonparametric maximum likelihood method (pnpml) assumes the number of unique variants fits a mixed Poisson distribution [17]. We chose the pnpml method to estimate the total number of unique variants because it also models the distribution of variant frequencies with estimated mixed Poisson parameters.

Application of variant estimation to BRCA1/2

Data for BRCA1/2 variant estimation were extracted from studies that identified at least 40 unique pathogenic variants because estimation techniques were sensitive to sample size and provided more stable estimates with a larger sample [12]. For some countries, data from several studies with unique participants were combined to obtain a larger sample of pathogenic variants. When variant nomenclature differed between studies, common variant names were identified via ClinVar [9] and HGMD [18] so that the frequency of variants could be more accurately determined. The variant data used for each country are listed in S1 Table. Both the Chao 1984 and pnpml method were implemented in R version 3.6.1 using functions from the SPECIES package [19]. Estimation parameters were not adjusted for variant sample size. In addition, as a supplemental analysis, we applied Chao and pnpml methods to BRCA1/2 gnomAD v2.1 data [20] for populations where at least 40 unique likely pathogenic or pathogenic variants, as identified by ClinVar [9] were observed in these genes.

Prevalence calculations

Overall frequency of variation is relevant to estimates of the total number of variants present. Studies from the PubMed search that had at least 100 participants and included both likely hereditary and sporadic cancer cases were used to assess the prevalence of pathogenic BRCA1/2 variant carriers in each study location. Cases were considered likely hereditary for a variety of reasons such as cancer diagnosis before age 35, bilateral breast cancer before age 50, and/or first-degree relative(s) with breast or ovarian cancer, though classification varied from study to study based on the information provided and, in some instances, cases were excluded from further analysis when the appropriate information was not provided.

For each study meeting the above criteria, the following data was extracted separately for likely hereditary and sporadic cancer cases if available: the number of individuals recruited, the number of individuals tested for pathogenic BRCA1/2 variation, and the number of pathogenic BRCA1/2 variant carriers. Extracted datasets with complete information can be found in S2 Table. These data were used to estimate the prevalence of pathogenic BRCA1/2 variant carriers in each country by maximizing the Horvitz-Thompson pseudo likelihood function described in Whittemore et al., which takes into account the number of individuals identified with a pathogenic variant among hereditary and sporadic cancer cases separately [21]. For estimation involving breast cancer cases, 0.57 was used as the probability of disease by age 70 given a BRCA1/2 pathogenic variant [22] while 0.07 was the probability of disease for noncarriers [23]. For ovarian cancer cases, 0.4 and 0.006 were used for these respective probabilities [22, 23]. Confidence intervals for all prevalence estimates were calculated using log transformed data.

Variant scaling

All pathogenic variants, even founder variants in BRCA1/2, were rare in all populations studied. However, for our analysis, “rare” is a relative term used to refer to variants that represent fewer than 5% of the BRCA1/2 variants in a given population or a given study. Recurrent pathogenic variants were identified using the studies included in the variant estimation analyses and were defined as variants that made up at least 5% of the observed variants for a respective country. The number of carriers of each recurrent variant in each country was estimated using the 2019 population size of the country, as listed by The World Bank [24]. The prevalence estimate used, 0.62%, was determined by averaging the prevalence estimates of BRCA1/2 pathogenic variant carriers from 3 population screening studies: The Healthy Nevada Project [3] the Geisinger MyCode Community Health Initiative [4] and the BioMe BioBank [2].

Results

We found that the Chao and pnpml species richness estimation methods could be applied to estimate "variant richness” and the number of missing variants in BRCA1/2. The pnpml method was more informative, generating an expected distribution, whereas the Chao method provided only a discrete lower bound of expected variants. A total of 53 studies were included in our analyses (Table 1), with 48 studies providing data for variant count estimation and 11 for BRCA1/2 prevalence estimation (6 had data used for both estimates). China, Spain, and the United States had the most studies identified meeting inclusion criteria. Of the 15 countries represented in our analyses, 2 were from North America, 1 from South America, 5 from Europe, 6 from Asia, and 1 from Australia.

Table 1. Studies included in analyses.

| Country | Reference | Method | Analysis | “Likely hereditary” definitiona |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | [25] AR Solano et al. (2017) | MLPA, NGS, Sanger sequencing | SE | |

| Australia | [26] K Alsop et al. (2012) | MLPA, Sanger sequencing | HT, SE | FDR with BC at <60 years; Male FDR with BC at any age; FDR with OC; 2+ FDR with BC/OC |

| Austria | [27] CF Singer et al. (2019) | DHPLC, MLPA, Sanger sequencing | HT | At least 1 other BC/OC in the family |

| Canada | [28] S Zhang et al. (2011) | DGGE, DHPLC, MLPA, PTT, Sanger sequencing | HT, SE | FDR with BC/OC |

| China | [29] WM Cao et al. (2016) | Sanger sequencing | SE | |

| [30] GT Lang et al. (2017) | NGS, Sanger sequencing | SE | ||

| [31] G Li et al. (2017) | NGS, Sanger sequencing | SE | ||

| [32] JY Li et al. (2019) | NGS panel | SE | ||

| [33] W Li et al. (2019) | NGS panel | SE | ||

| [34] J Ou et al. (2013) | DHPLC | SE | ||

| [35] T Shi et al. (2017) | NGS, Sanger sequencing | SE | ||

| [36] X Wu et al. (2017) | NGS, Sanger sequencing | HT | FDR/SDR with BC/OC | |

| [37] X Yang et al. (2015) | NGS panel, Sanger sequencing | SE | ||

| [38] X Zhong et al. (2016) | NGS, Sanger sequencing | SE | ||

| Denmark | [39] M Soegaard et al. (2008) | MLPA, Sanger sequencing | HT | FDR with BC/OC |

| India | [40] A Mehta et al. (2018) | MLPA, NGS | SE | |

| [41] S Saxena et al. (2006) | HDX, Sanger sequencing | SE | ||

| [42] J Singh et al. (2018) | NGS panel, Sanger sequencing | SE | ||

| [43] K Vaidyanathan et al. (2009) | CSGE, Sanger sequencing | SE | ||

| Italy | [44] C Capalbo et al. (2006) | MLPA, PTT, Sanger sequencing | SE | |

| [45] A Musolino et al. (2007) | DHPLC, Sanger sequencing | SE | ||

| [46] L Ottini et al. (2009) | PTT, Sanger sequencing, SSCP | SE | ||

| [47] IJ Seymour et al. (2008) | Sanger sequencing | SE | ||

| [48] L Stuppia et al. (2003) | PTT, Sanger sequencing, SSCP | SE | ||

| Japan | [49] A Hirasawa et al. (2014) | MLPA, Sanger sequencing | SE | |

| [50] M Sekine et al. (2001) | Sanger sequencing | SE | ||

| [51] K Sugano et al. (2008) | MLPA, Sanger sequencing | SE | ||

| Korea | [52] KJ Eoh et al. (2018) | NGS panel, Sanger sequencing | SE | |

| [53] H Kim et al. (2012) | DHPLC, CSCE, CSGE, Sanger sequencing | SE | ||

| [54] BS Kwon et al. (2019) | DHPLC, Sanger sequencing | HT, SE | Primary breast cancer; FDR/SDR with BC/OC | |

| [55] B Park et al. (2017) | MLPA, Sanger sequencing | SE | ||

| Malaysia | [56] E Thirthagiri et al. (2008) | MLPA, Sanger sequencing | SE | |

| [57] XR Yang et al. (2017) | MLPA, Sanger sequencing | HT, SE | Family history of BC | |

| Saudi Arabia | [58] R Bu et al. (2016) | Sanger sequencing | HT | FDR/SDR with BC/OC |

| Spain | [59] E Beristain et al. (2007) | CSGE, Sanger sequencing | SE | |

| [60] P Blay et al. (2013) | MLPA, Sanger sequencing | SE | ||

| [61] I de Juan et al. (2015) | CSCE, CSGE, HDX, HPLC, HRM, MLPA, NGS, Sanger sequencing | SE | ||

| [62] S de Sanjose et al. (2003) | DHPLC, HDX, Sanger sequencing | SE | ||

| [63] O Díez et al. (2003) | CSGE, DGGE, PTT, Sanger sequencing, SSCP | SE | ||

| [64] G Llort et al. (2002) | Sanger sequencing | SE | ||

| [65] MD Miramar et al. (2008) | DHPLC, MLPA, Sanger sequencing | SE | ||

| [66] A Ruiz de Sabando et al. (2019) | MLPA, Sanger sequencing | SE | ||

| UK | [67] Anglian Breast Cancer Study Group (2000) | HDX, Sanger sequencing | SE | |

| [68] VM Basham et al. (2002) | HDX, Sanger sequencing, SSCP | SE | ||

| [69] J Peto et al. (1999) | CSGE, Sanger sequencing | SE | ||

| USA | [70] EB Claus et al. (2005) | Sanger sequencing | HT, SE | FDR with BC |

| [71] AW Kurian et al. (2009) | 2D Gene Scanning, Exon Grouping Analysis, Sanger sequencing | HT | BC at <35 years; bilateral BC at <50 years; prior OC or childhood cancer; FDR with BC/OC | |

| [72] AM Martin et al. (2001) | CSGE, HDX, Sanger sequencing | SE | ||

| [73] Z Nahleh et al. (2015) | BART, Sanger sequencing | SE | ||

| [74] R Nanda et al. (2005) | DHPLC, SSCP, Sanger sequencing | SE | ||

| [75] T Pal et al. (2005) | Sanger sequencing | HT, SE | FDR/SDR with BC/OC | |

| [76] T Pal et al. (2015) | MLPA, Sanger sequencing | SE | ||

| [77] JN Weitzel et al. (2005) | Sanger sequencing | SE |

aDefinition of “likely hereditary” only provided for those countries where pathogenic BRCA1/2 prevalence estimates were calculated using the Horvitz-Thompson pseudo-likelihood function

BART: BRCA Analysis Rearrangement Testing, BC: breast cancer, CSCE: conformation sensitive capillary electrophoresis, CSGE: conformation sensitive gel electrophoresis, DGGE: denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis, DHPLC: denaturing high performance liquid chromatography, FDR: first-degree relative, HDX: heteroduplex analysis, HPLC: high performance liquid chromatography, HRM: high resolution melting analysis, HT: Horvitz-Thompson prevalence calculation, MBC: male breast cancer, MLPA: multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification, NGS: next generation sequencing, OC: ovarian cancer, PTT: protein truncation test, SDR: second-degree relative, SE: species estimation, SSCP: single strand conformation polymorphism

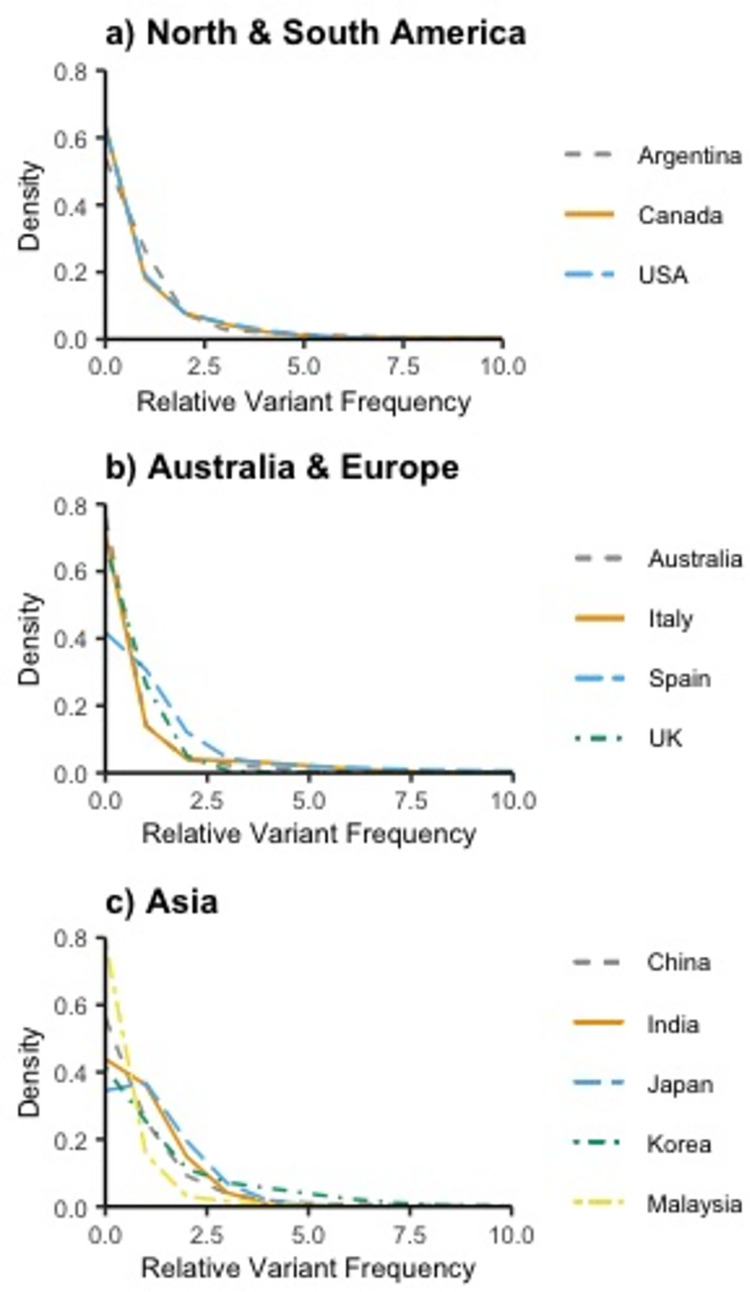

The estimated total number of unique pathogenic variants ranged from 137 (95% CI: 90..252) in Argentina to 1,153 in China (95% CI: 844..1,466) and are shown in Table 2. Chao and pnpml estimates were calculated for 12 countries. The pnpml estimates were consistently equal to or greater than the Chao estimates, as expected. The median Chao estimate was 364, and study samples consisted of 13% to 58% of the total expected variants, predicting 34% of the total variants on average. The median pnpml estimate was 395, and study samples consisted of 12% to 55% of the total expected variants, predicting 31% of the total variants on average. Conversely, the average proportion of missing variants was 69%, with studies expected to be missing 45% to 88% of variants. While China had both the largest number of unique variants sampled and the highest Chao and pmpml estimates, when all countries were considered, having a larger sample of unique variants did not always result in larger estimates. The mixed Poisson distributions of variant frequency estimated via the pnpml method are seen in Fig 1 and the parameters that make up these mixtures are listed in S3 Table. These estimated distributions indicate a higher proportion of rare variants compared to recurrent variants making up the pathogenic burden.

Table 2. Estimates for the total number of unique pathogenic BRCA1/2 variants in different countries using Chao and PNPML estimators.

| Country | # of People Screened | Observed # of Variants | Observed # of Unique Variants | Estimated # of Unique Variants, Chao | Estimated # of Unique Variants, PNPML |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 940 | 152 | 57 | 137 (90..252) | 137 (88..275) |

| Australia | 1,001 | 131 | 101 | 563 (312..1,114) | 647 (315..1,218) |

| Canada | 1,342 | 164 | 102 | 372 (233..658) | 461 (218..617) |

| China | 6,037 | 694 | 401 | 969 (806..1,198) | 1,153 (844..1,466) |

| India | 1,481 | 316 | 171 | 502 (365..734) | 520 (466..675) |

| Italy | 588 | 80 | 55 | 392 (160..1,139) | 397 (170..780) |

| Japan | 319 | 86 | 53 | 146 (92..277) | 146 (126..201) |

| Korea | 3,013 | 555 | 185 | 317 (263..409) | 356 (274..561) |

| Malaysia | 651 | 56 | 48 | 356 (143..1,043) | 392 (191..1,686) |

| Spain | 2,410 | 354 | 135 | 244 (195..332) | 244 (189..320) |

| UK | 2,146 | 59 | 49 | 149 (90..295) | 152 (96..394) |

| USA | 1,427 | 263 | 141 | 441 (306..687) | 562 (294..728) |

Fig 1. Normalized pathogenic variant frequencies in different locations globally.

a) North & South America, b) Australia & Europe, and c) Asia.

Chao and pnpml estimates were calculated for 5 populations from the gnomAD data: African, American, East Asian, European, and South Asian (S4 Table). The estimated total number of unique pathogenic variants ranged from 190 (95% CI: 98..447) for the African population to 850 (95% CI: 807..954) for the European population. The median Chao estimate was 494. The median pnpml estimate was 558 and gnomAD data consisted of 8% to 30% of the total expected variants, predicting 23% of the total variants on average.

Estimates of the prevalence of BRCA1/2 pathogenic variant carriers ranged from 0.09% (95% CI: 0.001, 9.42) (Denmark) to 1.05% (95% CI: 0.06, 18.58) (Austria) with a median estimate of 0.38% (IQR: 0.4) (Table 3). The median prevalence estimate was 0.64% (IQR: 0.25) among samples of breast cancer patients and 0.27% (IQR: 0.195) among samples of ovarian cancer patients. Although the prevalence point estimates were similar across countries, confidence intervals varied widely.

Table 3. Horvitz-Thompson estimates for the prevalence of BRCA1/2 carriers in various countries depending on cancer type.

| Hereditary | Sporadic | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer Type | Country | Estimate % (95% CI) | N Tested | N Carrier | N Tested | N Carrier |

| Breast | Malaysia [57] | 0.73 (0.03, 18.78) | 99 | 11 | 360 | 15 |

| Saudi Arabia [58] | 0.54 (0.01, 22.01) | 60 | 6 | 199 | 5 | |

| USA [70] | 0.38 (0.01, 17.04) | 93 | 6 | 274 | 5 | |

| USA [71] | 0.81 (0.05, 13.95) | 933 | 72 | 432 | 13 | |

| Ovarian | Australia [26] | 0.25 (0.01, 8.66) | 194 | 75 | 749 | 62 |

| Austria [27] | 1.05 (0.06, 18.58) | 331 | 168 | 112 | 16 | |

| Canada [28] | 0.25 (0.01, 7.71) | 327 | 111 | 993 | 78 | |

| China [36] | 0.59 (0.03, 12.94) | 96 | 68 | 730 | 167 | |

| Denmark [39] | 0.09 (0.001, 9.42) | 47 | 12 | 398 | 14 | |

| Korea [54] | 0.30 (0.01, 14.54) | 60 | 21 | 219 | 25 | |

| USA [75] | 0.27 (0.01, 15.29) | 99 | 22 | 110 | 10 | |

The most recurrent pathogenic variants in the included countries are listed in Table 4. In each country, the most recurrent variant made up between 5% to 16.4% of the total observed variants and the majority of the most recurrent variants were located in BRCA1. BRCA1 c.68_69del was seen commonly in 4 of the listed countries: Argentina, Canada, India, and the USA. Assuming that the overall prevalence of BRCA1/2 pathogenic variant carriers is 0.62%, India likely has the highest number of people carrying this variant, with an estimated 1,233,236 (95% CI: 920,037..1,604,558) affected, while the USA has the second highest number of carriers for this variant, with 255,353 (95% CI: 179,088..349,425) affected. Another variant, BRCA1 c.5266dup, was also observed commonly in 5 of the listed countries: Argentina, Australia, Canada, Italy, and the USA. The USA is estimated to have the most individuals with this variant, with 123,808 (95% CI: 71,635..197,200) carriers.

Table 4. Most common pathogenic BRCA1/2 variants in different countries.

| Country | Common Variants | # of Occurrences (% of Observed) | Estimated # of Carriers (95% CI) per 100,000 people* | Estimated # of Carriers (95% CI) Overalla |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | BRCA1 c.68_69del | 25 (16.4) | 102 (68, 145) | 45,826 (30,482..64,975) |

| BRCA2 c.5946del | 21 (13.8) | 86 (55, 127) | 38,494 (24,408..56,672) | |

| BRCA1 c.5266dup | 14 (9.2) | 58 (32, 93) | 25,663 (14,294..41,710) | |

| BRCA1 c.211A>G | 11 (7.2) | 45 (23, 78) | 20,164 (10,226..35,051) | |

| Australia | BRCA1 c.5266dup | 8 (6.1) | 38 (17, 73) | 9,604 (4,199..18,368) |

| Canada | BRCA1 c.5266dup | 11 (6.7) | 42 (22, 73) | 15,632 (7,924..27,221) |

| BRCA1 c.68_69del | 10 (6.1) | 38 (19, 68) | 14,211 (6,899..25,473) | |

| China | BRCA1 c.5470_5477del | 38 (5.5) | 34 (25, 47) | 474,499 (337,968..644,738) |

| India | BRCA1 c.68_69del | 46 (14.6) | 91 (68, 118) | 1,233,236 (920,037..1,604,558) |

| BRCA1 c.5074+1G>A | 22 (7.0) | 44 (28, 65) | 589,809 (373,606..876,831) | |

| Italy | BRCA1 c.1380dup | 6 (7.5) | 47 (18, 97) | 28,039 (10,468..58,358) |

| BRCA1 c.5266dup | 6 (7.5) | 47 (18, 97) | 28,039 (10,468..58,358) | |

| BRCA1 c.3756_3759del | 4 (5.0) | 32 (9, 77) | 18,693 (5,160..46,021) | |

| BRCA2 c.6468_6469del | 4 (5.0) | 32 (9, 77) | 18,693 (5,160..46,021) | |

| Japan | BRCA1 c.188T>A | 13 (15.1) | 94 (52, 152) | 118,337 (64,976..191,484) |

| BRCA1 c.2800C>T | 11 (12.8) | 80 (41, 135) | 100,132 (51,355..170,112) | |

| Korea | BRCA2 c.7480C>T | 51 (9.2) | 57 (43, 74) | 29,461 (22,186..38,151) |

| Malaysia | BRCA2 c.8961_8964del | 4 (7.1) | 45 (13, 108) | 14,150 (3,923..34,250) |

| BRCA2 c.5353_5354del | 3 (5.4) | 34 (7, 93) | 10,612 (2,219..29,456) | |

| Spain | BRCA2 c.2808_2811del | 32 (9.0) | 57 (39, 78) | 26,385 (18,301..36,543) |

| BRCA2 c.9026_9030del | 23 (6.5) | 41 (26, 60) | 18,964 (12,143..27,991) | |

| BRCA2 c.211A>G | 18 (5.1) | 32 (19, 50) | 14,842 (8,874..23,117) | |

| UK | BRCA1 c.4065_4068del | 3 (5.1) | 32 (7, 88) | 21,070 (4,393..58,634) |

| USA | BRCA1 c.68_69del | 33 (12.5) | 78 (55, 107) | 255,353 (179,088..349,425) |

| BRCA1 c.5266dup | 16 (6.1) | 38 (22, 61) | 123,808 (71,635..197,200) | |

| BRCA2 c.5946del | 15 (5.7) | 36 (21, 58) | 116,070 (65,734..187,839) |

aUsing prevalence estimate of 0.62

Discussion

Species richness methods from ecology can provide informative estimates of “variant richness” or the number of missing pathogenic variants in a location and the relative frequency of these variants. Results from the unique variant estimation indicate that for the included countries, between 45% and 88% of pathogenic BRCA1/2 variants have yet to be observed in research studies. While different countries have different variant frequencies, all countries appear to have many more rare pathogenic variants compared to recurrent variants. This suggests that most of the variants that have not yet been identified in each studied country will be rare and have not yet been detected due to incomplete sampling of patient populations.

Species richness methods applied to gnomAD data additionally suggest that many pathogenic BRCA1/2 variants are still missing in research data. The prediction of fewer African BRCA1/2 variants may be due, in part, to smaller sample size, but may also be a reflection of more prominent recent population growth in other populations as dated pathogenic founder variants occurred relatively recently [78–81]. While gnomAD is broken out by ancestry rather than nationality, from a public health standpoint, nationality may be a more straightforward and useful metric around which to design screening strategies.

The BRCA1/2 prevalence point estimates reported here are similar to those previously reported by population genetic screening studies [2–4]. We observed a median prevalence estimate of 0.64% and 0.27% using samples of breast and ovarian cancer patients, respectively. In comparison, the Healthy Nevada Project reported a 0.66% prevalence for pathogenic BRCA1/2 variant carriers [3] the Geisinger MyCode Community Health Initiative reported 0.5% [4] and the BioMe Biobank reported 0.7% [2]. Our results have greater uncertainty and wider confidence intervals due to smaller samples in the international set of studies we included compared to other studies that present prevalence estimates. For a small number of included studies, cases with unknown heredity were excluded, while cases with complete heredity information were used for estimation. This may have resulted in sampling bias [82–84] perhaps making estimates for these countries appear larger because cases with strong family history are less likely to have unknown hereditary information compared to sporadic cases. In addition, different definitions for hereditary and sporadic cancers across studies may have impacted results. However, similar overall results between our study and others suggest that the prevalence of BRCA1/2 pathogenic variants is relatively consistent despite there being unique recurrent and rare variants represented in different populations. This observation is consistent with an assumption of similar mutation rates in different populations and with documented global population growth [85].

The largest number of estimated pathogenic BRCA1/2 carriers are seen in countries with large populations, such as China and India. BRCA1 c.68_69del is a commonly observed variant in several countries and may be the most recurrent BRCA1/2 variant globally. Although it is popularly known because of its high frequency in individuals of Ashkenazi Jewish descent [86] the reason for its high estimated occurrence globally is primarily because of its apparent frequency in India. Individuals with this variant may mistakenly believe they have Jewish ancestry, even though this variant has been shown to occur on a different haplotype [87]. Despite being recognized as a highly observed variant in India [41, 43, 88, 89] the risk implications of BRCA1 c.68_69del for individuals of Asian Indian ancestry are not currently acted upon clinically. The list of BRCA1/2 variants expected to be most recurrent in different parts of the world (Table 4) highlights situations like this and suggests that there may still be recurrent variants in less well studied countries with significant and unrecognized clinical implications.

Our study does not represent all literature on BRCA1/2 and includes a limited number of countries because species richness methods cannot be accurately applied for countries where only a small number of pathogenic BRCA1/2 variants have been observed [12]. Therefore, we limited estimations about missingness and the frequency of missing variants to only those locations where a modest amount of research has already been conducted. Even for countries included, the samples used may not be representative of the country in its entirety [7, 90–92] and different sequencing strategies, enrollment criteria, and sampling strategies across studies may have biased the results for some countries. Furthermore, differences in the number of expected variants between populations may be attributable to estimation error or size of population, rather than biological differences in underlying population genetics. These limitations of the current literature are consistent with and strengthen our conclusion that there is a large amount of missing information about BRCA1/2 pathogenic variation globally.

Despite being two of the most studied genes in the world, much information is still missing about pathogenic variation in BRCA1/2. Multiple studies examining BRCA1/2 variation that we observed but did not include in our study only sequenced a small set of variants due to cost constraints [93, 94]. While such population-based strategies targeting specific variants commonly observed among cases have been proposed as potentially being more cost-efficient [5, 6], these strategies assume that the variants observed in a small subset of individuals will represent a large portion of variants observed throughout the population. The species richness methods presented here provide a more rigorous statistical means to evaluate if targeted assays will achieve the desired sensitivity in a given population and can inform decision-making about the utility of targeted versus expanded screening and guide future test development. We suggest that future surveys of genetic variation also model variant richness as we have described. This will provide a picture of what is observed with estimates of what is still unknown.

Supporting information

(PDF)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Data Availability

Data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supporting information files. Additional datasets used for analysis are available in The Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD), https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/downloads.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by the Brotman Baty Institute for Precision Medicine (BHS, https://brotmanbaty.org/). It was additionally supported by National Institute of Health grant, T32 GM081062 (NDR, https://www.niaid.nih.gov/grants-contracts/training-grants). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Bhaskaran SP, Chandratre K, Gupta H, Zhang L, Wang X, Cui J, et al. Germline variation in BRCA1/2 is highly ethnic-specific: Evidence from over 30,000 Chinese hereditary breast and ovarian cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2019. Aug 15;145(4):962–73. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abul-Husn NS, Soper ER, Odgis JA, Cullina S, Bobo D, Moscati A, et al. Exome sequencing reveals a high prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 founder variants in a diverse population-based biobank. Genome Med. 2019. Dec 31;12(1):2. doi: 10.1186/s13073-019-0691-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grzymski JJ, Elhanan G, Morales Rosado JA, Smith E, Schlauch KA, Read R, et al. Population genetic screening efficiently identifies carriers of autosomal dominant diseases. Nat Med. 2020. Aug;26(8):1235–9. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0982-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manickam K, Buchanan AH, Schwartz MLB, Hallquist MLG, Williams JL, Rahm AK, et al. Exome Sequencing-Based Screening for BRCA1/2 Expected Pathogenic Variants Among Adult Biobank Participants. JAMA Netw Open. 2018. Sep 7;1(5):e182140. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.2140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fragoso-Ontiveros V, Velázquez-Aragón JA, Nuñez-Martínez PM, de la Luz Mejía-Aguayo M, Vidal-Millán S, Pedroza-Torres A, et al. Mexican BRCA1 founder mutation: Shortening the gap in genetic assessment for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer patients. PloS One. 2019;14(9):e0222709. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0222709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gabai-Kapara E, Lahad A, Kaufman B, Friedman E, Segev S, Renbaum P, et al. Population-based screening for breast and ovarian cancer risk due to BRCA1 and BRCA2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014. Sep 30;111(39):14205–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415979111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rebbeck TR, Friebel TM, Friedman E, Hamann U, Huo D, Kwong A, et al. Mutational spectrum in a worldwide study of 29,700 families with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. Hum Mutat. 2018. May;39(5):593–620. doi: 10.1002/humu.23406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breast Cancer Association Consortium, Dorling L, Carvalho S, Allen J, González-Neira A, Luccarini C, et al. Breast Cancer Risk Genes—Association Analysis in More than 113,000 Women. N Engl J Med. 2021. Feb 4;384(5):428–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1913948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landrum MJ, Lee JM, Benson M, Brown GR, Chao C, Chitipiralla S, et al. ClinVar: improving access to variant interpretations and supporting evidence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018. Jan 4;46(D1):D1062–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chao A, Chiu CH. Species Richness: Estimation and Comparison. In: Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2016. p. 1–26. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781118445112.stat03432.pub2 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bunge J, Fitzpatrick M. Estimating the Number of Species: A Review. J Am Stat Assoc. 1993;88(421):364–73. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gotelli NJ, Colwell RK. Estimating species richness. In: Magurran AE, McGill BJ, editors. Biological Diversity: Frontiers in Measurement and Assessment. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Preston FW. The Commonness, And Rarity, of Species. Ecology. 1948;29(3):254–83. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daley T, Smith AD. Better lower bounds for missing species: improved non-parametric moment-based estimation for large experiments. arXiv:1605.03294v3 [stat.ME]. 2019. Available from: https://arxiv.org/abs/1605.03294 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chao A. Nonparametric Estimation of the Number of Classes in a Population. Scand J Stat. 1984;11(4):265–70. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chao A. Species Estimation and Applications. In: Kotz S, Read CB, Balakrishnan N, Vidakovic B, Johnson NL, editors. Encyclopedia of Statistical Sciences [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2006. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/ doi: 10.1002/0471667196.ess5051 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang JPZ, Lindsay BG. A Penalized Nonparametric Maximum Likelihood Approach to Species Richness Estimation. J Am Stat Assoc. 2005. Sep 1;100(471):942–59. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stenson PD, Ball EV, Mort M, Phillips AD, Shiel JA, Thomas NST, et al. Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD): 2003 update. Hum Mutat. 2003. Jun;21(6):577–81. doi: 10.1002/humu.10212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang J-P. SPECIES: An R Package for Species Richness Estimation. J Stat Softw. 2011. Apr 25;40:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karczewski KJ, Francioli LC, Tiao G, Cummings BB, Alföldi J, Wang Q, et al. The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature. 2020. May;581(7809):434–43. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2308-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whittemore AS, Gong G, John EM, McGuire V, Li FP, Ostrow KL, et al. Prevalence of BRCA1 mutation carriers among U.S. non-Hispanic Whites. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2004. Dec;13(12):2078–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen S, Parmigiani G. Meta-Analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 Penetrance. J Clin Oncol. 2007. Apr 10;25(11):1329–33. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.1066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howlader N, Noone A, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2017, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2017/ [Google Scholar]

- 24.Population, total. [cited 2021 Feb 17]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL

- 25.Solano AR, Cardoso FC, Romano V, Perazzo F, Bas C, Recondo G, et al. Spectrum of BRCA1/2 variants in 940 patients from Argentina including novel, deleterious and recurrent germline mutations: impact on healthcare and clinical practice. Oncotarget. 2017. Sep 1;8(36):60487–95. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alsop K, Fereday S, Meldrum C, deFazio A, Emmanuel C, George J, et al. BRCA Mutation Frequency and Patterns of Treatment Response in BRCA Mutation–Positive Women With Ovarian Cancer: A Report From the Australian Ovarian Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2012. Jul 20;30(21):2654–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.8545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singer CF, Tan YY, Muhr D, Rappaport C, Gschwantler‐Kaulich D, Grimm C, et al. Association between family history, mutation locations, and prevalence of BRCA1 or 2 mutations in ovarian cancer patients. Cancer Med. 2019. Mar 1;8(4):1875–81. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang S, Royer R, Li S, McLaughlin JR, Rosen B, Risch HA, et al. Frequencies of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations among 1,342 unselected patients with invasive ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2011. May 1;121(2):353–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cao WM, Gao Y, Yang HJ, Xie SN, Ding XW, Pan ZW, et al. Novel germline mutations and unclassified variants of BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in Chinese women with familial breast/ovarian cancer. BMC Cancer. 2016. Feb 6;16(1):64. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2107-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lang GT, Shi JX, Hu X, Zhang CH, Shan L, Song CG, et al. The spectrum of BRCA mutations and characteristics of BRCA-associated breast cancers in China: Screening of 2,991 patients and 1,043 controls by next-generation sequencing. Int J Cancer. 2017. Jul 1;141(1):129–42. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li G, Guo X, Tang L, Chen M, Luo X, Peng L, et al. Analysis of BRCA1/2 mutation spectrum and prevalence in unselected Chinese breast cancer patients by next-generation sequencing. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2017. Oct;143(10):2011–24. doi: 10.1007/s00432-017-2465-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li JY, Jing R, Wei H, Wang M, Xiaowei Q, Liu H, et al. Germline mutations in 40 cancer susceptibility genes among Chinese patients with high hereditary risk breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2019;144(2):281–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li W, Shao D, Li L, Wu M, Ma S, Tan X, et al. Germline and somatic mutations of multi-gene panel in Chinese patients with epithelial ovarian cancer: a prospective cohort study. J Ovarian Res. 2019. Aug 31;12(1):80. doi: 10.1186/s13048-019-0560-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ou J, Wu T, Sijmons R, Ni D, Xu W, Upur H. Prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 Germline Mutations in Breast Cancer Women of Multiple Ethnic Region in Northwest China. J Breast Cancer. 2013. Mar;16(1):50–4. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2013.16.1.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shi T, Wang P, Xie C, Yin S, Shi D, Wei C, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in ovarian cancer patients from China: ethnic-related mutations in BRCA1 associated with an increased risk of ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer. 2017. May 1;140(9):2051–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu X, Wu L, Kong B, Liu J, Yin R, Wen H, et al. The First Nationwide Multicenter Prevalence Study of Germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutations in Chinese Ovarian Cancer Patients. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2017. Oct;27(8):1650–7. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000001065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang X, Wu J, Lu J, Liu G, Di G, Chen C, et al. Identification of a Comprehensive Spectrum of Genetic Factors for Hereditary Breast Cancer in a Chinese Population by Next-Generation Sequencing. PLOS ONE. 2015. Apr 30;10(4):e0125571. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhong X, Dong Z, Dong H, Li J, Peng Z, Deng L, et al. Prevalence and Prognostic Role of BRCA1/2 Variants in Unselected Chinese Breast Cancer Patients. PLOS ONE. 2016. Jun 3;11(6):e0156789. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soegaard M, Kjaer SK, Cox M, Wozniak E, Høgdall E, Høgdall C, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation prevalence and clinical characteristics of a population-based series of ovarian cancer cases from Denmark. Clin Cancer Res. 2008. Jun 15;14(12):3761–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mehta A, Vasudevan S, Sharma SK, Kumar D, Panigrahi M, Suryavanshi M, et al. Germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 deleterious mutations and variants of unknown clinical significance associated with breast/ovarian cancer: a report from North India. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:6505–16. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S186563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saxena S, Chakraborty A, Kaushal M, Kotwal S, Bhatanager D, Mohil RS, et al. Contribution of germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 sequence alterations to breast cancer in Northern India. BMC Med Genet. 2006. Oct 4;7:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-7-75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Singh J, Thota N, Singh S, Padhi S, Mohan P, Deshwal S, et al. Screening of over 1000 Indian patients with breast and/or ovarian cancer with a multi-gene panel: prevalence of BRCA1/2 and non-BRCA mutations. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018. Jul;170(1):189–96. doi: 10.1007/s10549-018-4726-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vaidyanathan K, Lakhotia S, Ravishankar HM, Tabassum U, Mukherjee G, Somasundaram K. BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline mutation analysis among Indian women from south India: identification of four novel mutations and high-frequency occurrence of 185delAG mutation. J Biosci. 2009. Sep;34(3):415–22. doi: 10.1007/s12038-009-0048-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Capalbo C, Ricevuto E, Vestri A, Ristori E, Sidoni T, Buffone O, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic testing in Italian breast and/or ovarian cancer families: mutation spectrum and prevalence and analysis of mutation prediction models. Ann Oncol. 2006. Jun;17 Suppl 7:vii34–40. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Musolino A, Bella MA, Bortesi B, Michiara M, Naldi N, Zanelli P, et al. BRCA mutations, molecular markers, and clinical variables in early-onset breast cancer: a population-based study. Breast Edinb Scotl. 2007. Jun;16(3):280–92. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2006.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ottini L, Rizzolo P, Zanna I, Falchetti M, Masala G, Ceccarelli K, et al. BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation status and clinical-pathologic features of 108 male breast cancer cases from Tuscany: a population-based study in central Italy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009. Aug 1;116(3):577–86. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0194-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seymour IJ, Casadei S, Zampiga V, Rosato S, Danesi R, Scarpi E, et al. Results of a population-based screening for hereditary breast cancer in a region of North-Central Italy: contribution of BRCA1/2 germ-line mutations. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008. Nov;112(2):343–9. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9846-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stuppia L, Di Fulvio P, Aceto G, Pintor S, Veschi S, Gatta V, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in breast/ovarian cancer patients from central Italy. Hum Mutat. 2003. Aug;22(2):178–9. doi: 10.1002/humu.9164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hirasawa A, Masuda K, Akahane T, Ueki A, Yokota M, Tsuruta T, et al. Family History and BRCA1/BRCA2 Status Among Japanese Ovarian Cancer Patients and Occult Cancer in a BRCA1 Mutant Case. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2014. Jan 1;44(1):49–56. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyt171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sekine M, Nagata H, Tsuji S, Hirai Y, Fujimoto S, Hatae M, et al. Mutational analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 and clinicopathologic analysis of ovarian cancer in 82 ovarian cancer families: two common founder mutations of BRCA1 in Japanese population. Clin Cancer Res. 2001. Oct;7(10):3144–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sugano K, Nakamura S, Ando J, Takayama S, Kamata H, Sekiguchi I, et al. Cross-sectional analysis of germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Japanese patients suspected to have hereditary breast/ovarian cancer. Cancer Sci. 2008. Oct;99(10):1967–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00944.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eoh KJ, Kim JE, Park HS, Lee ST, Park JS, Han JW, et al. Detection of Germline Mutations in Patients with Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Using Multi-gene Panels: Beyond BRCA1/2. Cancer Res Treat. 2018. Jul;50(3):917–25. doi: 10.4143/crt.2017.220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim H, Cho DY, Choi DH, Choi SY, Shin I, Park W, et al. Characteristics and spectrum of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in 3,922 Korean patients with breast and ovarian cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012. Aug;134(3):1315–26. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2159-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kwon BS, Byun JM, Lee HJ, Jeong DH, Lee TH, Shin KH, et al. Clinical and Genetic Characteristics of BRCA1/2 Mutation in Korean Ovarian Cancer Patients: A Multicenter Study and Literature Review. Cancer Res Treat. 2019. Jul;51(3):941–50. doi: 10.4143/crt.2018.312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Park B, Sohn JY, Yoon KA, Lee KS, Cho EH, Lim MC, et al. Characteristics of BRCA1/2 mutations carriers including large genomic rearrangements in high risk breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017. May 1;163(1):139–50. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4142-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thirthagiri E, Lee SY, Kang P, Lee DS, Toh GT, Selamat S, et al. Evaluation of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations and risk-prediction models in a typical Asian country (Malaysia) with a relatively low incidence of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10(4):R59. doi: 10.1186/bcr2118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang XR, Devi BCR, Sung H, Guida J, Mucaki EJ, Xiao Y, et al. Prevalence and spectrum of germline rare variants in BRCA1/2 and PALB2 among breast cancer cases in Sarawak, Malaysia. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017. Oct;165(3):687–97. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4356-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bu R, Siraj AK, Al‐Obaisi KAS, Beg S, Al Hazmi M, Ajarim D, et al. Identification of novel BRCA founder mutations in Middle Eastern breast cancer patients using capture and Sanger sequencing analysis. Int J Cancer. 2016. Sep 1;139(5):1091–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Beristain E, Martínez-Bouzas C, Guerra I, Viguera N, Moreno J, Ibañez E, et al. Differences in the frequency and distribution of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in breast/ovarian cancer cases from the Basque country with respect to the Spanish population: implications for genetic counselling. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007. Dec;106(2):255–62. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9489-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Blay P, Santamaría I, Pitiot AS, Luque M, Alvarado MG, Lastra A, et al. Mutational analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 in hereditary breast and ovarian cancer families from Asturias (Northern Spain). BMC Cancer. 2013. May 17;13:243. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.de Juan I, Palanca S, Domenech A, Feliubadaló L, Segura Á, Osorio A, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in males with familial breast and ovarian cancer syndrome. Results of a Spanish multicenter study. Fam Cancer. 2015. Dec;14(4):505–13. doi: 10.1007/s10689-015-9814-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.de Sanjosé S, Léoné M, Bérez V, Izquierdo A, Font R, Brunet JM, et al. Prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline mutations in young breast cancer patients: A population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2003;106(4):588–93. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Díez O, Osorio A, Durán M, Martinez-Ferrandis JI, de la Hoya M, Salazar R, et al. Analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in Spanish breast/ovarian cancer patients: a high proportion of mutations unique to Spain and evidence of founder effects. Hum Mutat. 2003. Oct;22(4):301–12. doi: 10.1002/humu.10260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Llort G, Muñoz CY, Tuser MP, Guillermo IB, Lluch JRG, Bale AE, et al. Low frequency of recurrent BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Spain. Hum Mutat. 2002. Mar;19(3):307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miramar MD, Calvo MT, Rodriguez A, Antón A, Lorente F, Barrio E, et al. Genetic analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 in breast/ovarian cancer families from Aragon (Spain): two novel truncating mutations and a large genomic deletion in BRCA1. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008. Nov;112(2):353–8. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9868-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ruiz de Sabando A, Urrutia Lafuente E, García-Amigot F, Alonso Sánchez A, Morales Garofalo L, Moreno S, et al. Genetic and clinical characterization of BRCA-associated hereditary breast and ovarian cancer in Navarra (Spain). BMC Cancer. 2019. Nov 27;19(1):1145. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-6277-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Anglian Breast Cancer Study Group. Prevalence and penetrance of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in a population-based series of breast cancer cases. Anglian Breast Cancer Study Group. Br J Cancer. 2000. Nov;83(10):1301–8. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Basham VM, Lipscombe JM, Ward JM, Gayther SA, Ponder BA, Easton DF, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in a population-based study of male breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2002;4(1):R2. doi: 10.1186/bcr419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Peto J, Collins N, Barfoot R, Seal S, Warren W, Rahman N, et al. Prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations in patients with early-onset breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999. Jun 2;91(11):943–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.11.943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Claus EB, Petruzella S, Matloff E, Carter D. Prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutations in Women Diagnosed With Ductal Carcinoma In Situ. JAMA. 2005. Feb 23;293(8):964–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.8.964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kurian AW, Gong GD, John EM, Miron A, Felberg A, Phipps AI, et al. Performance of prediction models for BRCA mutation carriage in three racial/ethnic groups: findings from the Northern California Breast Cancer Family Registry. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2009. Apr;18(4):1084–91. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-1090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Martin AM, Blackwood MA, Antin-Ozerkis D, Shih HA, Calzone K, Colligon TA, et al. Germline mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 in breast-ovarian families from a breast cancer risk evaluation clinic. J Clin Oncol. 2001. Apr 15;19(8):2247–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.8.2247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nahleh Z, Otoukesh S, Dwivedi AK, Mallawaarachchi I, Sanchez L, Saldivar JS, et al. Clinical and pathological characteristics of Hispanic BRCA-associated breast cancers in the American-Mexican border city of El Paso, TX. Am J Cancer Res. 2015;5(1):466–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nanda R, Schumm LP, Cummings S, Fackenthal JD, Sveen L, Ademuyiwa F, et al. Genetic testing in an ethnically diverse cohort of high-risk women: a comparative analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in American families of European and African ancestry. JAMA. 2005. Oct 19;294(15):1925–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.15.1925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pal T, Permuth-Wey J, Betts JA, Krischer JP, Fiorica J, Arango H, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations account for a large proportion of ovarian carcinoma cases. Cancer. 2005. Dec 15;104(12):2807–16. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pal T, Bonner D, Cragun D, Monteiro ANA, Phelan C, Servais L, et al. A high frequency of BRCA mutations in young black women with breast cancer residing in Florida. Cancer. 2015. Dec 1;121(23):4173–80. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Weitzel JN, Lagos V, Blazer KR, Nelson R, Ricker C, Herzog J, et al. Prevalence of BRCA mutations and founder effect in high-risk Hispanic families. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2005. Jul;14(7):1666–71. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hamel N, Feng BJ, Foretova L, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Narod SA, Imyanitov E, et al. On the origin and diffusion of BRCA1 c.5266dupC (5382insC) in European populations. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011. Mar;19(3):300–6. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Janavičius R, Rudaitis V, Feng BJ, Ozolina S, Griškevičius L, Goldgar D, et al. Haplotype analysis and ancient origin of the BRCA1 c.4035delA Baltic founder mutation. Eur J Med Genet. 2013. Mar;56(3):125–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2012.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Marroni F, Cipollini G, Peissel B, D’Andrea E, Pensabene M, Radice P, et al. Reconstructing the genealogy of a BRCA1 founder mutation by phylogenetic analysis. Ann Hum Genet. 2008. May;72:310–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2007.00420.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Peixoto A, Santos C, Pinheiro M, Pinto P, Soares MJ, Rocha P, et al. International distribution and age estimation of the Portuguese BRCA2 c.156_157insAlu founder mutation. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011. Jun;127(3):671–9. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1036-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Geibel J, Reimer C, Weigend S, Weigend A, Pook T, Simianer H. How array design creates SNP ascertainment bias. PloS One. 2021;16(3):e0245178. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lachance J, Tishkoff SA. SNP ascertainment bias in population genetic analyses: why it is important, and how to correct it. BioEssays. 2013. Sep;35(9):780–6. doi: 10.1002/bies.201300014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nielsen R. Population genetic analysis of ascertained SNP data. Hum Genomics. 2004. Mar 1;1(3):218–24. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-1-3-218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, Samocha KE, Banks E, Fennell T, et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016. Aug;536(7616):285–91. doi: 10.1038/nature19057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Struewing JP, Abeliovich D, Peretz T, Avishai N, Kaback MM, Collins FS, et al. The carrier frequency of the BRCA1 185delAG mutation is approximately 1 percent in Ashkenazi Jewish individuals. Nat Genet. 1995. Oct;11(2):198–200. doi: 10.1038/ng1095-198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kadalmani K, Deepa S, Bagavathi S, Anishetty S, Thangaraj K, Gajalakshmi P. Independent origin of 185delAG BRCA1 mutation in an Indian family. Neoplasma. 2007;54(1):51–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mannan AU, Singh J, Lakshmikeshava R, Thota N, Singh S, Sowmya TS, et al. Detection of high frequency of mutations in a breast and/or ovarian cancer cohort: implications of embracing a multi-gene panel in molecular diagnosis in India. J Hum Genet. 2016. Jun;61(6):515–22. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2016.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rajkumar T, Meenakumari B, Mani S, Sridevi V, Sundersingh S. Targeted Resequencing of 30 Genes Improves the Detection of Deleterious Mutations in South Indian Women with Breast and/or Ovarian Cancers. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16(13):5211–7. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.13.5211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kim YC, Zhao L, Zhang H, Huang Y, Cui J, Xiao F, et al. Prevalence and spectrum of BRCA germline variants in mainland Chinese familial breast and ovarian cancer patients. Oncotarget. 2016. Feb 23;7(8):9600–12. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Laitman Y, Friebel TM, Yannoukakos D, Fostira F, Konstantopoulou I, Figlioli G, et al. The spectrum of BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic sequence variants in Middle Eastern, North African, and South European countries. Hum Mutat. 2019. Nov;40(11):e1–23. doi: 10.1002/humu.23842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Vos JR, Teixeira N, van der Kolk DM, Mourits MJE, Rookus MA, van Leeuwen FE, et al. Variation in mutation spectrum partly explains regional differences in the breast cancer risk of female BRCA mutation carriers in the Netherlands. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2014. Nov;23(11):2482–91. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-1279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Briceño-Balcázar I, Gómez-Gutiérrez A, Díaz-Dussán NA, Noguera-Santamaría MC, Díaz-Rincón D, Casas-Gómez MC. Mutational spectrum in breast cancer associated BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in Colombia. Colomb Med. 2017. Jun 30;48(2):58–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Villarreal-Garza C, Alvarez-Gómez RM, Pérez-Plasencia C, Herrera LA, Herzog J, Castillo D, et al. Significant clinical impact of recurrent BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Mexico. Cancer. 2015. Feb 1;121(3):372–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

Data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supporting information files. Additional datasets used for analysis are available in The Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD), https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/downloads.