Abstract

A very important area where COVID-19 has seriously disrupted is the global financial markets, where stock markets have experienced great turmoil. To shed light on the nature of this turmoil and to characterize nonlinear dynamics in inter-market risk transmission, we formally test the existence of inter-stock market contagion, identify the main channel once the presence of contagion has been established, and assess the upside and downside risk spillovers dynamically focusing on complexity during pre-COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 periods. Applying multiple measures including time-varying conditional value-at-risk based on copula theory, and sample entropy methods, considering a sample covering seven countries (USA, UK, France, Germany, Japan, Brazil, China) during the period from 4 January 2019 to 30 December 2020, we show that contagion is widely present among analysed stock markets with only a few exceptions and that “portfolio rebalancing” as opposed to “wealth constraint” occurs more as the main channel of transmission. All market pairings exhibit significant bilateral upside and downside spillovers after the outbreak of COVID-19. A significant shift in complexity of risk spillover dynamics is evident for most recipient countries following the shock of COVID-19, among which all but China display a downward shift. The findings of this paper could help regulators, politicians, and portfolio risk managers amid the uncertainty created by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, Copula functions, Sample entropy, Complex risk spillover

Introduction

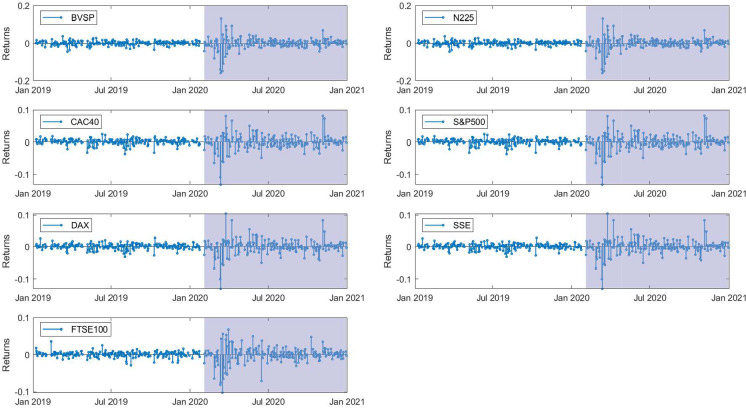

The recent COVID-19 highlighted that financial markets around the world are growing more intertwined as integrated complex systems. It generated a worldwide market slump and caused global economic recessions. In the case of stock markets, all major indices fell sharply in March 2020 (see Fig. 1), with the S &P 500 witnessing repeated drops, triggering a circuit breaker mechanism four times consecutively in two weeks. The intensity of such turmoil is comparable to many well-known financial crises. As such stock market crashes can inflict huge impacts on the management of international portfolios, it is of great importance to understand the nature of simultaneous stock market crashes as well as the nonlinear dynamics in the mechanism behind them.

Fig. 1.

The relative price dynamics of stock market indexes

As pointed out by Forbes and Rigobon [21], a high level of correlation between markets in turmoil periods may simply be a result of strong linkages persistent at all times, yet the main concern is the phenomenon of contagion, i.e., a significant increase in the cross-market comovement after a shock. Although there is some debate in the literature about the definition and measurement of contagion [6, 18, 21, 42], we follow the above definition given by Forbes and Rigobon [21] in this paper, as it is widely accepted in the literature and has the advantage of not relying on theoretical explanations to define excessive shock transmission. Since the focus on this research is contagion, it is of importance to distinguish its definition from other relevant concepts like interdependence and integration. Interdependence suggests a high level of market comovement in all time, while contagion refers to a significant increase in comovement in turmoil period. Integration is a much wider concept, which focus on the degree of market movement susceptible to multiple global factors, and contagion can be one of the consequences when integration is present. When a contagion between stock markets is identified, it is important to assess the channel through which it occurs. Potentially, the financial transmission of contagion could be divided into two types: (i) the wealth constraint channel where investors are forced to sell assets outside the shock-originating market due to margin calls or large withdrawals from mutual funds [36] and (ii) the portfolio rebalancing channel where investors adjust their portfolios to achieve better risk profiles [13].

The literature generally acknowledges the presence of contagion in financial markets under the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Empirical studies have found that after the COVID-19 outbreak, risks in global financial markets increased significantly [27, 63], leading to spillover effects across various asset classes [17, 25, 41, 59], including equity markets [4, 31]. However, there are limited studies on the investor-induced channels behind this contagion across stock markets facing the COVID-19 pandemic, and it is unclear what roles are played by wealth constraint and portfolio balancing in different markets. In addition, since risk can be faced by holding either long (downside risk) or short (upside risk), whether upside risk spillovers and downside risk spillovers may have different dynamic behaviours requires more detailed investigation, which is rare in the literature. Last and perhaps more importantly, despite a general interests in nonlinear financial dynamics of return, volatility and order flow series (see [24, 37, 40, 47, 56, 58] amongst others), there is little investigation into inter-market dynamics, like the risk spillover series. In this study, we attempt to address these issues.

Therefore, this paper aims to make a contribution to the existing literature from three perspectives. First, it formally detects the existence of contagion and identifies the main channel of contagion during the COVID-19 turmoil in multiple stock markets worldwide. To the best of our knowledge, the analysis on cross-market contagion and its primary channels for this pandemic period through formal tests have not yet been made. Second, this paper dynamically quantifies the risk spillover effects of substantial inter-market contagion, distinguishing between upper and lower tail risks. Third, the complexity of upside and downside risk spillovers is measured and how it has been affected by the shock of the COVID-19 is examined. In doing so, we are able to add richness and depth to the current discussion on nonlinear dynamic behaviours of risk transmission, by comparing upside and downside spillover patterns, as well as analysing potential change in complexity characteristics.

Methods

The methods we applied in this study are all based on copula theory [34, 44]. Financial risk contagion is defined as a significant increase in cross-market linkages following a shock to one or more markets [21], and such linkages are usually approximated by the correlation coefficients between financial markets. In recent years, the copula function has been regarded as a more desirable mathematical tool for measuring the correlation of skewed or asymmetric distributions of multidimensional financial time series. It is known for providing great flexibility when modelling marginal distributions separately, while the traditional correlation measures given by linear correlation coefficients are inappropriate and often misleading [12, 20]. Studies that examined financial contagion during the 2008 crisis through copula theory [5, 29] verified that the superiority of copula theory is mainly reflected in two aspects: i) It provides statistics that give a more complete picture of the nonlinear correlation among multivariate variables, such as the Kendall coefficient based on the copula function. ii) It offers statistics to quantify the linkage of extreme events. For example, the asymptotic tail correlation coefficient that can measure the probability of large simultaneous increases and decreases in the stock markets. In addition, Reboreo and Ugolini [50] use the copula model to characterize and calculate the conditional value at risk (CoVaR) proposed by Adrian and Brunnermeier [3].

Let and be the two random variables of the joint distribution function , with marginal distribution functions and , respectively. According to Sklar’s theorem, the standard representation of copula is a joint function that couples two marginal distribution functions together [53]), expressing the joint distribution function as

| 1 |

If the marginal distribution functions and are all continuous, for and is a unique bivariate copula function; otherwise, is uniquely determined on . As shown in Eq. (1), the copula provides a natural way to study and characterize the dependence structure between random variables. Therefore, we provide some dependence measures based on the copula.

Kendall’s and Spearman’s , originally known as two accepted measures of nonparametric rank correlations with their sample-based estimators, can now be obtained by measuring the probability of concordance between continuous random variables with the appropriate selection of the underlying copula, given by

| 2 |

| 3 |

Then, they are possible to extract synthetic and global measures of association between variables, note that the values of them are still often quite different.

Corresponding to the extreme upward or downward movements of the joints of two random variables and , the upper (right) and lower (left) tail dependence coefficients are defined as

| 4 |

| 5 |

where and . If or are positive, and are said to be asymptotically correlated in the lower tail (upper tail), which means that we have a nonzero probability of observing extremely minimal (large) values for both variables at the same time; () mean that and are asymptotically uncorrelated in the lower tail (upper tail).

In addition, the conditional value-at-risk in financial markets (CoVaR) proposed by Adrian and Brunnermeier [3] and popularized by Girardi and Ergün [23] is a well-known directional tail dependence measure of systemic risk [10, 11] and can also be estimated using the copula function [45]. To capture the evolution of tail risk dependence on stock returns over time, dynamic copulas [46] are used to develop time-varying CoVaRs in combination with ARMA-TGARCH models [49, 50] and upper and lower value-at-risk (VaR). Recall that VaR [48] focuses on isolated financial market risks and quantifies the maximum losses that a stock market is likely to experience over a given time horizon and level of confidence by holding either long (downside risk) or short (upside risk). At time , for confidence level , downside and upside are defined as and , respectively. Let and be the returns of stock markets A and B, respectively. The downside CoVaR of the stock market A at confidence level can be formally defined as the -quantile of the conditional distribution of , given as

| 6 |

Similarly, we can measure the upside CoVaR of stock market A in a given extreme upward movement in terms of the return of stock market B, given as

| 7 |

Since the conditional probabilities can be rewritten, the CoVaRs in Eqs. (6)–(7) can be expressed by copula, respectively, as [see Eqs. (4)–(5)]

| 8 |

| 9 |

where and are marginal distribution functions of returns of stock market A and stock market B, respectively. In practice, and are usually set to the same confidence level, as was the case in this study.

For a clearer and more logical presentation of the methodologies used in this article, we summarize them into the following six steps. The first four steps are to measure financial contagion and identify the main channels through which a financial crisis spreads, referring to the methods in [29, 32]. The five step is to analyse the dynamic risk spillovers. And the final step is to analyse the complexity of the dynamic risk spillovers.

Step 1: ARMA-TGARCH models

Financial return series have typical characteristics such as volatility clustering and leverage effect. Compared with the classical GARCH model, Bekaert et al. [7] propose that the threshold generalized autoregressive conditional heteroscedasticity (TGARCH) model can better reflect the above characteristics of financial returns. Therefore, in this paper, the ARMA-TGARCH model is applied to remove the autocorrelation and conditional heteroscedasticity of the return series to obtain the standardized residuals for subsequent correlation analysis. For each return time series, we select its corresponding optimal model by Akaike’s criterion (AIC) to obtain the filtered return series, i.e., the standardized residual series. For the sake of simplicity, the filtered returns are referred to as “returns” then. The original stock return series are divided into two periods: the pre-COVID-19 period and the in-COVID-19 period. The details of the sample splitting are introduced in Sect. 3. And the optimal ARMA-TGARCH model is obtained for each period of a stock return series. The ARMA(p, q) model is

| 10 |

where p and q are both nonnegative integers; and are the autoregressive (AR) and moving average (MA) parameters, respectively. , where is the dynamic conditional variance, given by the threshold generalized autoregressive conditional heteroscedasticity (TGARCH) model,

| 11 |

In the above equation, is a constant; and are the GARCH and ARCH components, respectively; if , and if ; captures asymmetric effects, i.e., when the future conditional variance will increase proportionally more after a negative shock than after a positive shock of the same magnitude, and when the volatility model in Eq. (11) is a GARCH model. Generally, the residuals of the actual financial returns do not conform to a normal distribution. Thus, Hansen’s (1994) skewed-t density distribution is used to capture the fat tail and asymmetry in the distribution of stock residuals. is an i.i.d. random variable with zero mean and unit variance, and according to [38] it follows the following distribution,

| 12 |

where is a symmetric Student-t probability density function, is the skew parameter that measures asymmetry () and v is the degree of freedom parameter (). Parameters a and b are the mean and variance, respectively, given by and . Using Akaike criterion (AIC), the optimal combinations of ARMA-TGARCH model parameters are selected to characterize the marginal distribution of financial returns and to obtain filtered returns (standardized residuals).

Step 2: copula approaches

In most available research of financial market risk, the copula functions are applied to measure the dependence between the extreme values of two random variables, i.e., the tail dependence coefficient. In this paper, we consider a symmetrized Joe–Clayton copula (SJC), which allows for asymmetric dependence in the lower and in the upper tails of the distribution. Some common Archimedean copulas like Clayton and Gumbel also allow for tail dependence. However, while modelling dependence in the lower (Clayton) and the upper (Gumbel) tails of the distribution, they impose no dependence in the opposite tail. When two tails are modelled using two different copulas, the tail dependence coefficients are not necessarily comparable between each other. One cannot say that a country had stronger dependence in the lower tail than in the upper tail, for instance, by using two distinct copulas for each of the tails. SJC copula does not suffer from these problems. The SJC copula, as a type of Archimedean copula, is a slight modification of the Joe–Clayton copula [34] proposed by Patton [46]. The Joe–Clayton copula is:

| 13 |

where , , and are the tail dependence coefficients. The symmetrized Joe–Clayton (SJC) copula modifies the Joe–Clayton copula by nesting symmetry as a special case, that is,

| 14 |

Step 3: the bootstrap technique

In order to prepare for the financial contagion test, we bootstrap the four dependence coefficients: Kendall’s , Spearman’s , and , each of which has 1000 repeated constructs. The bootstrap technique used in this step was proposed by Horta et al. [30] and Jayech [32] inspired by Trivedi and Zimmer [57], and the steps are summarized as:

-

(i)

For a pair of stock returns of equal length, the vector of parameters () calculated by the given copula function is obtained, which is defined as .

-

(ii)

A new sample of observations is done by pairwise resampling of the returns of the original filter as a replacement, and they are used to reestimate , , , and store the estimate as vector .

-

(iii)

Repeat steps (ii) times (with ) and denote the nth estimation of the parameters as , , , , . Then, the nth vector of parameters is stored as , .

-

(iv)

The standard deviations of the estimators are the square roots of the main diagonal of the following matrix: .

Step 4: two tests of financial contagion

The two hypothesis tests of contagion under investigation are described below.

Test 1: The first test is to examine the existence of a financial contagion in stock markets during the outbreak of COVID-19. Considering the difference of Kendall’s and Spearman’s , they are both suggested in this paper to identify contagion between markets during the outbreak of COVID-19 under stricter criteria [32]. In other words, to determine the existence of contagion between markets, the correlation measured by Kendall’s and Spearman’s extracted from the given copula, should both increase during the outbreak of COVID-19 when compared to the tranquil period. But if we find no increase in such comovements, even if the comovement measure is of high degree, the stock markets are said to exhibit no contagion but only interdependence.

Using the Kendall’s , the null hypothesis and the alternative one are:

| 15 |

Similarly, using the Spearman’s , we have

| 16 |

In Eqs. (15)–(16), x denotes pairs of filtered stock returns, and rejecting the null hypothesis means that the contagion exists. To obtain the probability distribution of and , 1000 replications are constructed using the bootstrap procedure in Step 3 for , , , and , where each replication produces one value for and . After increasingly sorting the 1000 values, the p-values of the tests can be inferred.

Test 2: If the null hypothesis is rejected in the first test, that is, there is contagion between the stock markets. This second test is then applied to assess whether the channel of contagion is due to wealth constraint or portfolio rebalancing. In the former case, as demonstrated by the model of Kyle and Xiong [36], the presence of liquidity constraints makes the dependence between the filtered stock returns to be higher during market stress than during market boom. Or in other words, there exist asymmetric extreme comovements between markets. In the latter case, as a consequence of the model by Kodres and Pritsker [35], the dependence between the filtered stock returns is expected to be equal, displaying symmetric extreme comovements. The asymptotic tail coefficients, and , are able to measure the probability that both stock markets will experience a high price rise or fall at the same time. Thus, we use a two-tailed t-test to compare comovements between markets when prices fell sharply with those when prices rose sharply after the outbreak of the COVID-19 period,

| 17 |

where x denotes pairs of filtered stock returns. As in Test 1, 1000 bootstraps performed to calculate the values of the statistics and by pairwise resampling the returns to finally obtain the test statistics . Based on test statistics and critical values at 1% significance level (), pairs of markets will be categorized into three types: (i) wealth constraint as the main channel (rejecting the null hypothesis with test statistic greater than 2.576); (ii) portfolio rebalancing as the main channel (rejecting the null hypothesis with test statistic less than ); (iii) unclear main channel (not rejecting the null hypothesis).

Step 5: dynamic risk spillover analysis

The conditional value-at-risk (CoVaR) will be represented in terms of dynamic copulas in this step. To this aim, the temporal dynamics of the correlation coefficients of the Student-t copula and the SJC copula are characterized by the autoregressive moving average process following [46]. For in the Student-t copula:

| 18 |

where is the modified logistic transformation to always keep in (-1,1), and g is the order of the moving average processes. For and in the SJC copula:

| 19 |

| 20 |

where is the logistic transformation, used to keep and in (0, 1) at all times. We calculate CoVaR according to a two-step procedure [50]: First, given the same confidence level of VaR and CoVaR () and the specific form of the copula function, we solve Eqs. (8)–(9) to obtain the value of then, in the second step, using the distribution function for the stock market returns given by the marginal models in Eqs. (10)–(12), we calculate that CoVaR is . Combining the above two steps with the dynamic copulas, time-varying CoVaRs will be obtained and applied in the following two tests to reveal more details about both upside and downside risk spillovers.

Test 3: The third test in this study uses the Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) bootstrapping test introduced by Abadie [1] and applied by Bernal et al. [9], to test the significance of risk spillovers by comparing cumulative distributions for the and the of stock markets. The KS test relies on the empirical distribution function, but does not consider any underlying distribution function, and measures the difference between two functions of accumulated integrals, defined as

| 21 |

where and are the cumulative CoVaR and VaR distribution functions, respectively, and and are the sample sizes. According to the value of this statistic, we test the null hypothesis of no risk spillover effects between stock markets as follows:

| 22 |

and

| 23 |

Test 4: This test is to examine whether there is a significant difference between the effect of risk spillover transmitted to or received by a market. Such asymmetry follows the definition of “spatial asymmetry”, noted by [43]. More specifically, taking the upside-risk spillover between market A and market B as an example, we consider two directions: from A to B and from B to A. For each direction, we normalize the upside CoVaR by the upside VaR. The KS statistic is then calculated for these normalized CoVaR of two directions to test for significant differences. With this statistic, we test the null hypothesis of no spatial asymmetry in the downside risk spillover between stock markets:

| 24 |

And if the null hypothesis is rejected, we perform a second test to check which direction is of stronger risk spillover:

| 25 |

Similarly, the above tests are also conducted for upside risk spillovers.

Step 6: complexity analysis of dynamic risk spillovers

The sample entropy (SampEn) [52] is a improved approach of nonlinear dynamical analysis to measure the complexity of time series compared with approximate entropy (ApEn), and with improved accuracy SampEn statistics is also largely independent of data length and displays more relative consistency than ApEn does. Two input parameters, a length of sequences to be compared (h) and a tolerance for accepting matches (), must be specified for each SampEn calculation, which is proceed as follows:

-

(i)For a time series of N points, , forms the vectors as follows,

26 -

(ii)Calculate the Chebyshev distance between each pair of sequences to be compared as,

27 -

(iii)

Consider as a template. Let be the number of vectors , , within of . Define the function as the probability that any vector is within of . Define the function as the average of the functions .

-

(iv)

Get by repeating steps 1 to 3 with embedding dimension .

-

(v)

Estimate the statistic .

In order to study the changes in the complexity of the risk dynamic spillovers received by a stock market before and in the COVID-19, we calculated the SampEn of the upside and downside time-varying CoVaR series obtained in Step 5 at different confidence levels and then get the following test.

Test 6: With the statistic SampEn of the time-varying CoVaRs, we test the null hypothesis of no changes in the complexity of the risk dynamic spillovers received by a stock market at different confidence levels ():

| 28 |

Data and descriptive statistics

In this study, we consider stock markets from seven countries, covering major economies and emerging ones. For each market, we choose a representative index, i.e., the Standard and Poor’s 500 for the US (S &P500), the Financial Times Stock Exchange 100 Index for UK (FTSE100), the CAC 40 index for France (CAC40), the Deutscher Aktienindex for Germany (DAX), the Nikkei 225 index for Japan (N225), the Bovespa index for Brazil (BVSP), the Shanghai Stock Exchange (SSE) Composite index for China. The daily closing prices of these indices are used, excluding observations where data of one or more markets are missing due to holidays or weekends. All data are sourced from Bloomberg Terminal, and the sample period is from 4 January 2019 to 30 December 2020.

We first show the dynamics of closing prices (Fig. 1) and logarithmic returns (Fig. 2). In Fig. 1, the relative closing price series are obtained by adjusting all series to the same starting price, so as to give a better view of market comovement. On a glance, it is notable that all stock markets exhibit a deep price drop shortly after the coronavirus outbreak, accompanied by a strengthened clustering of volatility (Fig. 2). To investigate such a change in price dynamics, we split the sample period into the pre-COVID-19 period and the in-COVID-19 period. As there are no unified breakpoint choices, we choose the breakpoint at 30 January 2020, at which the Committee of WHO agreed that the outbreak of COVID-19 met the criteria for a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. This breakpoint date is similar to multiple other studies [17, 22]. Alternative breakpoint choice given by the Bai–Perron test is also considered, which is only six data points later, and we find switching to this alternative breakpoint has brought about little changes in the main results.

Fig. 2.

Logarithmic returns from 4 January 2019 to 30 December 2020 of BVSP, CAC40, DAX, FTSE100, N225, S &P500 and SSE

Table 1 reports descriptive statistics for all return series considered over the whole sample period as well as the two subsample periods. For the whole sample period, the average returns are close to zero. Volatility behaviours in markets are measured by standard deviations, which shows that volatility levels are comparable in most stock markets. Only one market (Brazil) is characterized by volatility exceeding 0.02. All return series exhibit high kurtosis and negative skewness, consistent with fat-tailed return distributions. Consequently, the Jarque–Bera test results support the rejection of the normality of all return series. When we compare the descriptive statistics for two subsample periods, all return series are lower in average but higher in volatility for the in-COVID-19 period. In fact, volatility levels easily double or triple after the COVID-19 hit, with the only exception being the Chinese market, which has the smallest increase in volatility. Yet, this is still an increase above 20% which is not commonly seen. Another notable feature is the reduction in skewness values in most markets, which indicates that the return distribution is more left skewed, that is, more negative extreme price movements are observed after the outbreak of COVID-19. Nonnormality of return distributions still holds for both pre- and in-COVID-19 periods.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics

| Max | Min | Mean (%) | STD | Kurtosis | Skewness | JB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole sample | |||||||

| BVSP | 0.1302 | − 0.1599 | 0.0779 | 0.0242 | 17.8871 | − 1.5419 | 3746.3197* |

| CAC40 | 0.0814 | − 0.1310 | 0.0462 | 0.0182 | 15.9901 | − 1.2016 | 2828.6451* |

| DAX | 0.1041 | − 0.1305 | 0.0673 | 0.0184 | 16.2212 | − 0.7721 | 2871.8835* |

| FTSE100 | 0.0867 | − 0.1151 | − 0.0069 | 0.0161 | 15.2935 | − 1.1649 | 2537.5339* |

| N225 | 0.0773 | − 0.0714 | 0.0812 | 0.0152 | 9.2047 | − 0.0013 | 623.9875* |

| S &P500 | 0.0897 | − 0.1277 | 0.1045 | 0.0182 | 17.3311 | − 1.1730 | 3418.1040* |

| SSE | 0.0755 | − 0.0804 | 0.0808 | 0.0135 | 9.6027 | − 0.1883 | 708.9033* |

| Pre-COVID-19 | |||||||

| BVSP | 0.0440 | − 0.0449 | 0.1493 | 0.0124 | 4.5712 | − 0.3007 | 24.2925* |

| CAC40 | 0.0243 | − 0.0364 | 0.1185 | 0.0088 | 5.9528 | − 0.9779 | 107.6732* |

| DAX | 0.0282 | − 0.0316 | 0.1153 | 0.0091 | 4.2791 | − 0.4871 | 22.1899* |

| FTSE100 | 0.0223 | − 0.0332 | 0.0528 | 0.0080 | 4.7559 | − 0.4809 | 34.4051* |

| N225 | 0.0323 | − 0.0305 | 0.0840 | 0.0093 | 3.9501 | 0.1012 | 8.1006* |

| S &P500 | 0.0212 | − 0.0302 | 0.1413 | 0.0078 | 5.8784 | − 0.9487 | 102.0164* |

| SSE | 0.0545 | − 0.0532 | 0.0859 | 0.0122 | 6.5473 | 0.1205 | 108.5033* |

| In-COVID-19 | |||||||

| BVSP | 0.1302 | − 0.1599 | − 0.0023 | 0.0328 | 11.1318 | − 1.2432 | 551.3505* |

| CAC40 | 0.0814 | − 0.1310 | − 0.0352 | 0.0248 | 9.6435 | − 0.8740 | 359.8321* |

| DAX | 0.1041 | − 0.1305 | 0.0133 | 0.0251 | 9.9253 | − 0.5692 | 375.5763* |

| FTSE100 | 0.0867 | − 0.1151 | − 0.0741 | 0.0219 | 9.3213 | − 0.8800 | 328.3082* |

| N225 | 0.0773 | − 0.0714 | 0.0780 | 0.0199 | 6.5015 | − 0.0090 | 93.4887* |

| S &P500 | 0.0897 | − 0.1277 | 0.0630 | 0.0252 | 9.8990 | − 0.8624 | 385.6051* |

| SSE | 0.0755 | − 0.0804 | 0.0750 | 0.0149 | 10.5698 | − 0.3698 | 441.0946* |

JB denote the Jarque–Bera statistics for normality. An asterisk (*) indicates rejection of the null hypothesis (normal return distribution) at 5%

Empirical results

Marginal distribution

In Tables 2 and 3, the estimation results for stock returns based on the marginal models [Eqs. (10)–(12)] are presented for the pre- and in-COVID-19 periods, respectively. The choices for the lag parameters in the ARMA and TGARCH process are made by minimizing the AIC values over different combinations of p, q, r, m, ranging from 0 to 2. According to the pre-COVID-19 sample (Table 2), all stock returns exhibit serial correlation and more than half of the series show a high degree of volatility persistency. However, the asymmetric effect is not common and is observed only in three markets. The skewed Student-t distribution is characterized by the skew parameter, which governs the symmetry of the distribution, and the shape parameter, also known as the degrees of freedom. The former is significant for all and the latter is insignificant for only one market (UK), indicating that overall error terms are nonnormal and instead follow an asymmetrical distribution. More specifically, it can be observed from the sign of that only the Japanese and Chinese markets show slightly left-skewed error terms, while the rest are all skewed to the right.

Table 2.

Parameter estimates for marginal distribution models using pre-COVID-19 sample

| BVSP | CAC40 | DAX | FTSE100 | N225 | S &P500 | SSE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | |||||||

| 0.0019* | 0.0029* | 0.0008 | 0.0019* | 0.0005* | 0.0016* | 0.0037* | |

| (22.0279) | (2253.6877) | (1.4295) | (12649.1192) | (198.6832) | (1301.8018) | (2518.1155) | |

| − 0.2534* | 0.9871* | 0.9425* | 0.0211* | − 0.5353* | − 0.2287* | 1.0000* | |

| (− 1070.7225) | (149.5750) | (740.2807) | (3.6253) | (− 3644.3505) | (− 4845.3152) | (109.8970) | |

| 0.6827* | − 1.0281* | 0.9306* | 0.4744* | 0.7237* | |||

| (961.0543) | (− 834.8224) | (120.7843) | (6069.4192) | (2636.3639) | |||

| 0.3005* | − 0.9594* | − 0.9461* | − 0.0067* | 0.5449* | 0.2218* | − 0.9235* | |

| (926.2293) | (− 6115.2797) | (− 626.4208) | (− 2.3242) | (7468.2118) | (3128.4054) | (− 5468.8112) | |

| − 0.7657* | − 0.0768* | 1.0255* | − 1.0658* | − 0.5372* | − 0.8658* | − 0.1146* | |

| (− 1991.3875) | (− 2469.1984) | (814.3099) | (− 44366.9750) | (− 2470.3534) | (− 8757.6857) | (− 3845.7482) | |

| Variance | |||||||

| 0.0000 | 0.0056* | 0.0006 | 0.0070* | 0.0079* | 0.0002 | 0.0003 | |

| (0.0037) | (2.8338) | (1.5219) | (6.6907) | (13.7014) | (0.9908) | (1.5434) | |

| 0.0010 | 0.1973* | 0.0799* | 0.0559 | 0.1977* | 0.0887* | 0.0470* | |

| (0.8600) | (2.8224) | (2.0772) | (0.2520) | (3.5201) | (2.5413) | (3.7259) | |

| 0.0603* | 0.6235* | ||||||

| (2.3990) | (6.0637) | ||||||

| 0.9517* | 0.8867* | 0.9046* | 0.9431* | ||||

| (281.3315) | (18.0719) | (32.4272) | (13.2012) | ||||

| 0.0000 | |||||||

| (0.0000) | |||||||

| − 0.6980 | 1.0000* | 1.0000 | − 0.6724 | 0.9952* | 0.2900 | − 1.0000* | |

| (− 0.0353) | (4.3663) | (1.5205) | (− 0.1832) | (45.5846) | (0.8550) | (− 6.5061) | |

| − 0.3706* | − 0.1150 | ||||||

| (− 2.0207) | (− 0.4540) | ||||||

| skew | 0.8507* | 0.6964* | 0.8658* | 0.8534* | 1.0232* | 0.7835* | 1.0858* |

| (12.6539) | (16.1453) | (11.5402) | (11.8544) | (12.5339) | (11.0710) | (11.2071) | |

| shape | 5.1816* | 2.5470* | 3.6487* | 26.3642 | 4.6916* | 5.2060* | 4.7242* |

| (3.3866) | (15.2141) | (3.5971) | (1.4361) | (4.0312) | (2.9509) | (3.2104) | |

| AIC | − 5.9934 | − 6.8499 | − 6.6951 | − 6.8847 | − 6.5698 | − 7.0813 | − 6.1556 |

| LogLik | 630.3168 | 716.5386 | 700.5956 | 719.1235 | 686.6882 | 740.3693 | 645.0251 |

| LB | 18.7463 | 15.3890 | 24.7720 | 17.9460 | 22.3193 | 23.5231 | 16.1707 |

| [0.5384] | [0.7537] | [0.2103] | [0.5910] | [0.3234] | [0.2638] | [0.7060] | |

| LB 2 | 7.3508 | 9.0971 | 15.1238 | 12.4110 | 15.7981 | 23.7545 | 25.2448 |

| [0.9954] | [0.9818] | [0.7693] | [0.9012] | [0.7291] | [0.2533] | [0.1922] | |

| ARCH | 8.5936 | 8.0974 | 12.3520 | 10.9718 | 14.3136 | 23.9630 | 21.4060 |

| [0.9872] | [0.9912] | [0.9034] | [0.9470] | [0.8142] | [0.2440] | [0.3736] |

The table shows parameter estimates, t-values (in brackets) and the Akaike criterion (AIC) for the optimal combination of parameters of the ARMA-TGARCH models described in Eqs. (10)–(12). The asterisks (*), behind the estimated values in the first line, denote the level of significance to reject the null hypothesis (each coefficient is NOT statistically significant). LogLik, LB, LB 2 denote the log-likelihood value and the Ljung–Box statistic for serial correlation in the residual model and in the squared residual model calculated with 20 lags, respectively. ARCH denotes Engle’s LM test for the ARCH effect in residuals up to the 20th order. The p values (in square brackets) below 0.05 reject the null hypothesis of the correct specification

Table 3.

Parameter estimates for marginal distribution models using in-COVID-19 sample

| BVSP | CAC40 | DAX | FTSE100 | N225 | S &P500 | SSE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | |||||||

| 0.0005 | − 0.0012* | − 0.0021* | − 0.0013* | 0.0005 | 0.0004 | 0.0005 | |

| (0.6860) | (− 3.3378) | (− 10.4308) | (− 3.8779) | (0.8794) | (0.4594) | (0.6586) | |

| − 0.6553* | − 1.3141* | − 1.4938* | − 1.8324* | ||||

| (− 15.7730) | (− 78.8749) | (− 65.8320) | (− 412.5326) | ||||

| − 0.7645* | − 0.6359* | − 0.9327* | − 0.9245* | ||||

| (− 18.4993) | (− 84.7165) | (− 38.6331) | (− 213.7788) | ||||

| 0.7596* | 1.3755* | 1.5024* | 1.8202* | ||||

| (25.1224) | (227.4407) | (147.8802) | (577.7390) | ||||

| 0.8778* | 0.7614* | 0.9858* | 0.9277* | ||||

| (33.2509) | (85.4759) | (100.3902) | (220.6828) | ||||

| Variance | |||||||

| 0.0034* | 0.0010* | 0.0048* | 0.0013* | 0.0008 | 0.0015* | 0.0074* | |

| (2.6146) | (3.8685) | (14.1218) | (3.6581) | (1.3823) | (2.3898) | (4.5742) | |

| 0.3739* | 0.2885* | 0.4196* | 0.0685* | 0.2183* | 0.2049* | 0.2087* | |

| (3.2683) | (5.2257) | (32.8822) | (2.0880) | (2.5450) | (2.3102) | (1.9616) | |

| 0.1200* | 0.7727* | 0.3004* | 0.5469 | ||||

| (9.2287) | (37.2154) | (32.9723) | (0.7781) | ||||

| 0.4772* | 0.0000 | 0.5660* | 0.1279 | 0.7919* | |||

| (2.5858) | (0.0000) | (62.5871) | (1.0215) | (11.1532) | |||

| 0.0947 | 0.5205* | 0.6865* | |||||

| (0.5704) | (5.5220) | (5.4587) | |||||

| 0.8323* | 0.8234* | 1.0000* | 1.0000* | 1.0000* | 0.9140* | 0.3546 | |

| (5.0028) | (5.1232) | (18.1663) | (2.9453) | (3.3543) | (2.2242) | (0.7987) | |

| 1.0000* | − 0.2356* | − 0.0580 | − 0.4349 | ||||

| (2.7216) | (− 14.6950) | (− 1.3924) | (− 0.6999) | ||||

| skew | 0.8919* | 0.9972* | 0.8554* | 0.8501* | 1.0532* | 0.7166* | 1.0024* |

| (9.3888) | (10.5370) | (12.0637) | (9.3525) | (11.7855) | (8.1726) | (11.7156) | |

| shape | 19.8465 | 4.2361* | 3.4994* | 8.5423 | 3.4732* | 3.3045* | 3.2738* |

| (0.7309) | (3.8453) | (6.2075) | (1.9021) | (4.2572) | (4.9992) | (3.9379) | |

| AIC | − 4.8854 | − 5.1423 | − 5.0984 | − 5.2777 | − 5.4642 | − 5.5758 | − 5.8199 |

| LogLik | 455.0177 | 484.5218 | 478.5035 | 495.9054 | 507.9732 | 521.1837 | 540.5228 |

| LB | 16.0982 | 11.4992 | 12.5258 | 12.1650 | 20.9543 | 20.8595 | 8.5411 |

| [0.7105] | [0.9322] | [0.8968] | [0.9103] | [0.3998] | [0.4054] | [0.9876] | |

| LB 2 | 18.8524 | 2.1099 | 6.6805 | 13.2306 | 1.7264 | 1.1182 | 1.5745 |

| [0.5314] | [1.0000] | [0.9976] | [0.8673] | [1.0000] | [1.0000] | [1.0000] | |

| ARCH | 21.8196 | 13.8544 | 16.1792 | 41.7759 | 1.8316 | 5.8711 | 14.4658 |

| [0.3504] | [0.8378] | [0.7054] | [0.0030] | [1.0000] | [0.9991] | [0.8061] |

See notes for Table 2

Turning to the in-COVID-19 sample (Table 3), the serial correlation becomes insignificant in Brazilian, Japanese and Chinese markets, while remains significant in the rest. The strength of volatility persistence remains in these markets. A notable change is detected in the asymmetric effect, since all but one return series (China) show a significant positive , indicating that asymmetry in the conditional variance becomes common overall. As to the error distributions, the pattern of skew parameters is roughly the same, but there is one more market (Brazil) where the shape parameter value is not significant, compared to the pre-COVID-19 period. We also observe some interesting changes in individual markets, e.g., the French market displays the lowest value of shape during the pre-COVID-19 period but highest during the in-COVID-19 period among others, revealing drastic changes in error distributional properties. The returns of both subsamples that are filtered by the marginal models are then put to test through Ljung-Box and Engle approaches, confirming serial correlation and conditional heteroscedasticity becoming negligible.

Contagion and channels

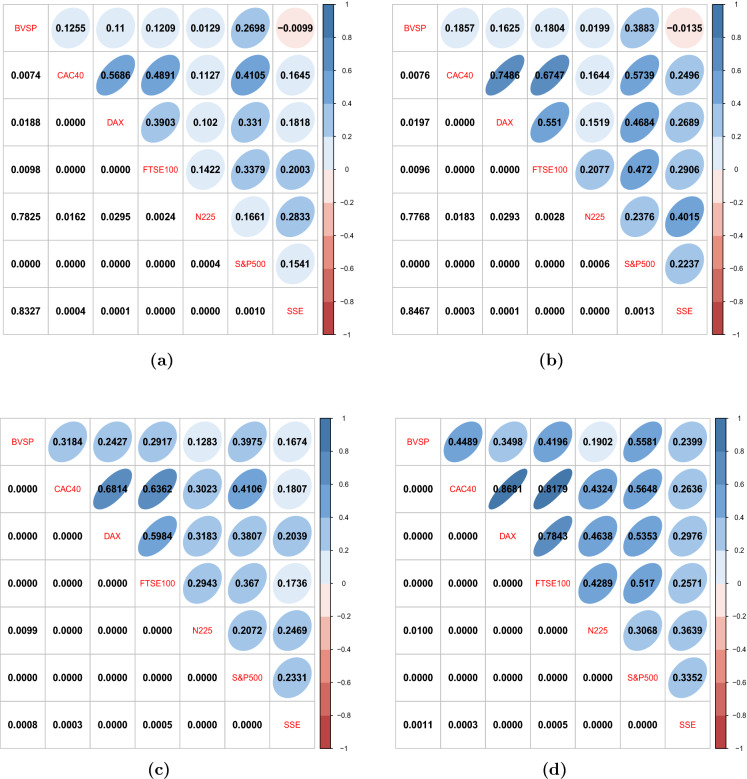

Based on the estimation results of marginal distributions, we can proceed to examine whether contagion is present between markets, and if so, what is the main channel of contagion. Before formally testing for contagion, it is helpful to investigate the comovements between market returns. We apply two measures, Kendall’s and Spearman’s , estimated by sample-based as well as copula-based. As all these methods give identical results for testing the existence of contagion and the main channel of contagion, we only report the sample-based results as representative to save space. Figure 3 presents estimates of these comovement measures for both subsample periods. For each matrix, the diagonal cells list names of the stock indices, the upper triangular displays the comovement coefficients, while the lower triangular reports the corresponding p-values indicating significance. Moreover, a graphical demonstration is added in the cell background of the upper triangular, where darker tones represent higher values of comovement coefficients, as shown by the colour bar. As shown in Fig. 3a, in the pre-COVID-19 sample period, almost all Kendall’s estimates for stock returns series pairings are positive (the pair of Brazil and China is the only exception), and 16 of them are tested as significant at the 1% level. The US market occupies a central position because the S &P 500 is the only index that has a significant value of Kendall’s with all other indices, while the comovement structure of the remaining indices reflects geographic closeness. Such results are generally in line with other studies. In Fig. 3b, the results of the same sample period are given, but using Spearman’s as an alternative comovement measure. Spearman’s usually produces a higher estimate value than Kendall’s , which is exactly the case in our results. In terms of significance, the results are identical for both measures at the level. The results for the in-COVID-19 period are shown in Fig. 3c and d; all pairs of stock returns are estimated to show significantly positive Kendall’s as well as Spearman’ at a level of , which can be seen as supportive evidence of the existence of contagion.

Fig. 3.

Market comovements measured by Kendall’s for a pre-COVID-19 and c in-COVID-19 periods, by Spearman’s for b pre-COVID-19 and d in-COVID-19 periods. Corresponding p-values are in matrix lower triangulars

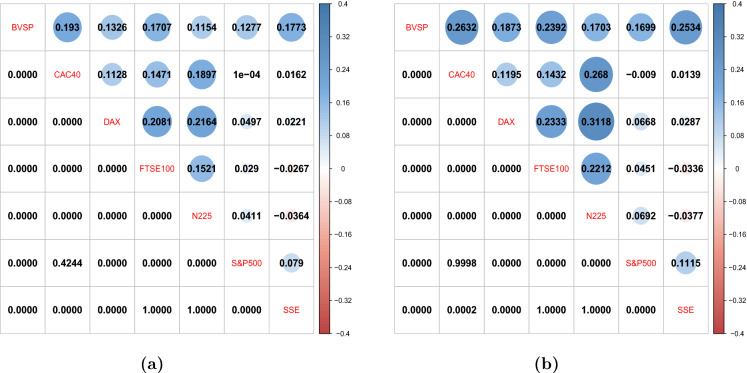

Although the above evidence is in favour of the presence of contagion, it is necessary to formally test these market pairings for positive and significant changes in comovement estimates after the COVID-19 outbreak. The test results are shown in Fig. 4a and b, where the upper triangular of each matrix shows the values of [Eq. (15)] or [Eq. (16)], while the lower triangular shows the corresponding p-values. Similar conclusions can be drawn using either of the measures, i.e., financial contagion is present at 1% significance level in almost all market pairings with a few exceptions, namely USA and France, China and UK, China and Japan. The existence of contagion among a majority of markets is quite as expected, since empirical studies of previous crises have revealed similar market behaviours [8, 19, 29, 32]. Among the market pairs without contagion, three are associated with China, corroborating some empirical evidence from other studies. For instance, in a recent study [43], applying similar copula-based test statistics, the equity market contagion between China and the UK and between China and Japan were bidirectional insignificant. In an earlier study, utilizing the Kalman filter method, it was found that the Chinese market was highly independent of European markets during the European debt crisis period [55]. On the contrary, it is somewhat surprising that our test detects contagion to be missing when pairing the US and France, but evidence of no contagion between the US and other mature equity markets during crises is not totally unseen, as suggested by [43]. Noteworthy, these two markets maintain a considerable degree of interdependence during both the pre-COVID-19 and in-COVID-19 periods, which is different from the aforementioned pairs associated with China, where only some weak dependency is found among them. Thus, there is a continuous sizeable comovement between the two, the US and France, possibly due to the interconnectedness of fundamentals between economies, just not in the way of contagion defined by [21].

Fig. 4.

a and b comparing pre-COVID-19 and in-COVID-19 periods. Corresponding p values are in matrix lower triangulars

Once the contagion is detected, the next step is to identify the main channel of the contagion. To this end, we perform the contagion channel test (Test 2) for each pair that passed the above contagion test (Test 1). The matrix in Fig. 5a reports the copula s (Eqs. (4) and (5)) of the upper (lower) tails in the upper (lower) triangular. In the matrix shown in Fig. 5b, the upper triangular shows the values of [Eq. (17)] and uses the colour tones and sizes of circles to help visualize these values, while the lower triangular gives corresponding test statistics. Pairs can be clearly categorized into 3 types: 5 pairs are with the wealth constraint as the main channel (blue colour tone or rejecting the null hypothesis with test statistic greater than 2.576); 11 pairs are with portfolio rebalancing as the main channel (red colour tone or rejecting the null hypothesis with test statistic less than ); the rest 2 pairs are of unclear main channel (white colour tone or not rejecting the null hypothesis). Overall, the occurrence of portfolio rebalancing being the main channel outnumbers that of wealth constraint channel, suggesting that it is of more importance, which in general is consonant with studies regarding the 2008 financial crisis [29] and the 2011 stock market crash [32]. A finding different from these studies is that the US market is susceptible to the wealth constraint channel. One possible explanation is that the US equity market exhibited some features during the heightened time of the COVID-19 outbreak that were unseen in previous periods of crisis. Specifically, four times of trading halts took place in just one fortnight, inflicting heavy and rapid losses on investors.

Fig. 5.

For in-COVID-19 periods a (lower triangular) and (upper triangular) and b (upper triangular) and corresponding test statistics (lower triangular). The corresponding critical values of the two-sided t-test are with significance level

Complex dynamic risk spillovers

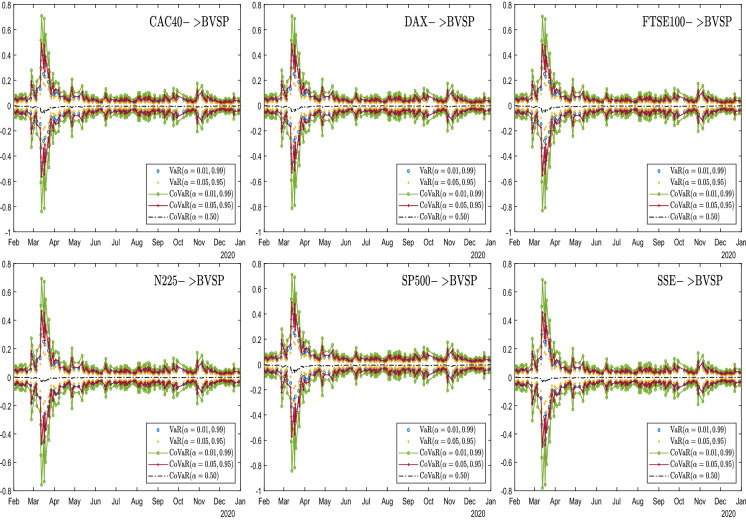

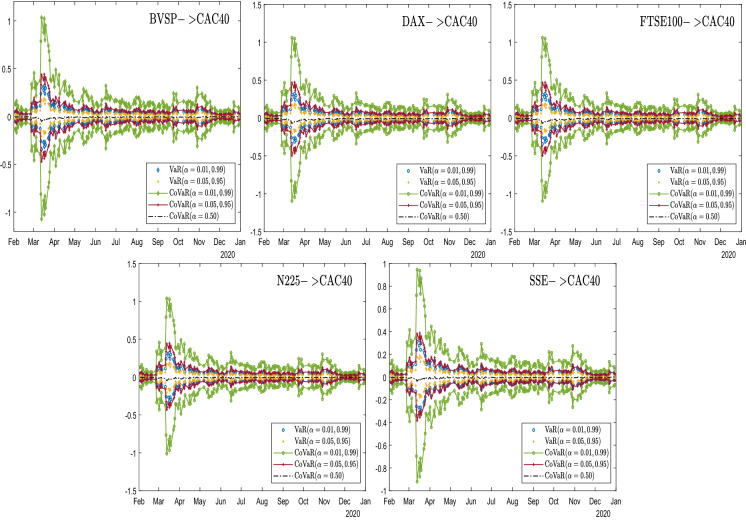

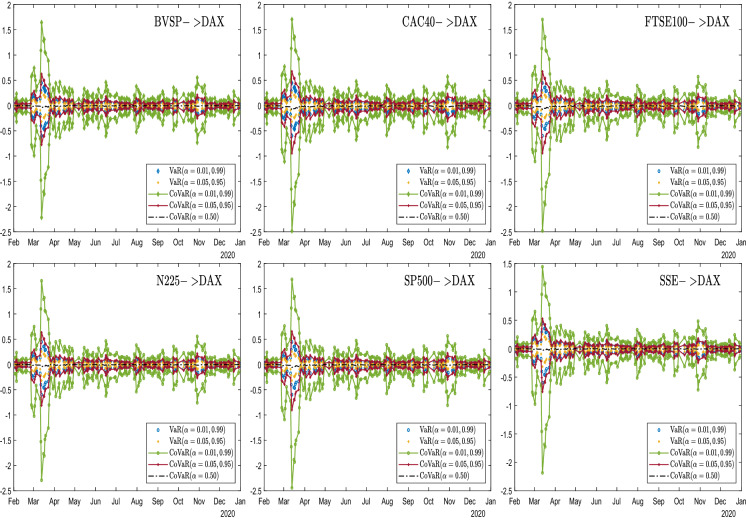

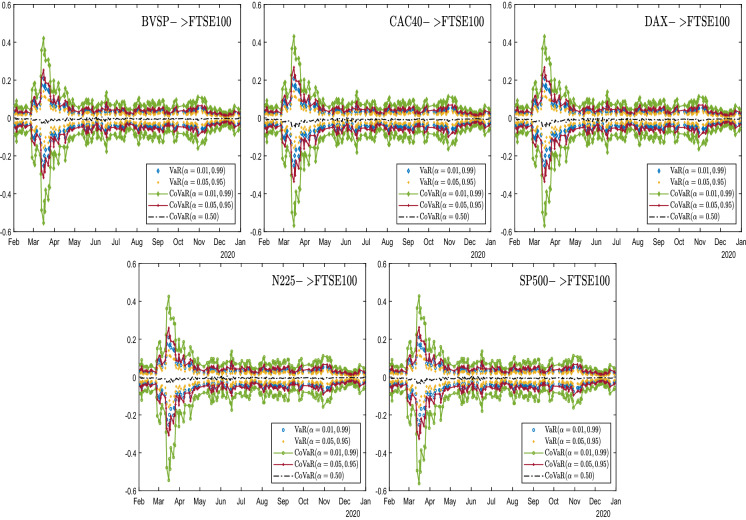

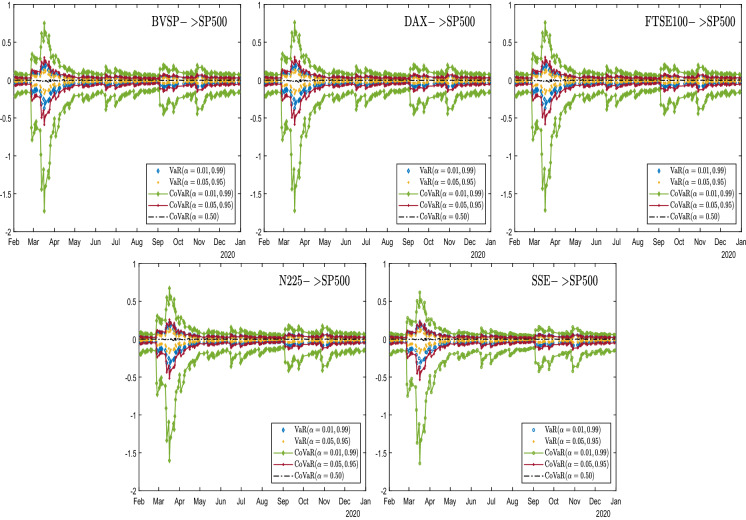

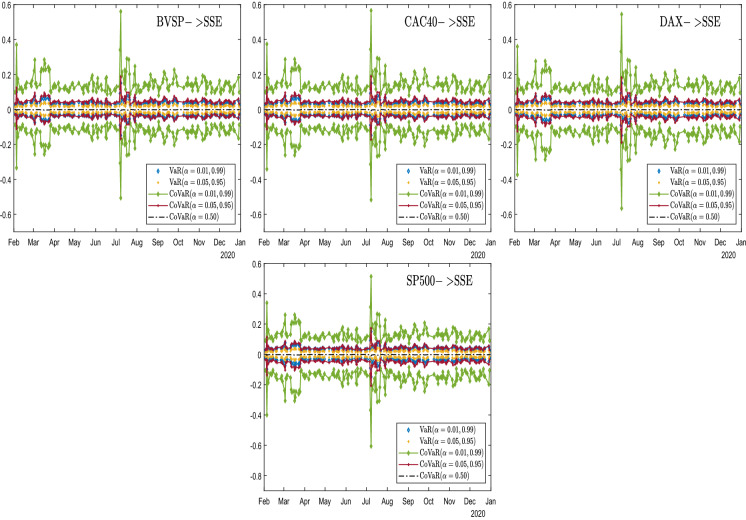

In this section, we analyse the behaviour of dynamic risk spillovers among stock markets where the contagion is identified and using sample entropy to characterize complexity in spillover series. On the basis of the SJC copula information, we consider both downside and upside conditional value-at-risk (CoVaR) for returns at two confidence levels (95% and 99%). To obtain these CoVaR values, VaR values of the corresponding confidence level are calculated as well. Figures 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 display these results for market pairings that passed the contagion test. Figures are grouped by receiver markets for better presentation, where the positive vertical axis indicates the magnitude of the upside risk and the negative vertical axis indicates that of the downside risk.

Fig. 6.

Time-varying CoVaR and VaR towards the Brazilian stock market

Fig. 7.

Time-varying CoVaR and VaR towards the French stock market

Fig. 8.

Time-varying CoVaR and VaR towards the German stock market

Fig. 9.

Time-varying CoVaR and VaR towards the UK stock market

Fig. 10.

Time-varying CoVaR and VaR towards the Japanese stock market

Fig. 11.

Time-varying CoVaR and VaR towards the US stock market

Fig. 12.

Time-varying CoVaR and VaR towards the Chinese stock market

In these figures, some common features are found as follows. First, for almost all market pairs, the general trend of VaR and CoVaR evolution is quite similar, with China perhaps being the only exception to be discussed later. Moreover, risk spillovers from different countries received by the same country bear obvious pattern resemblance, almost indistinguishable to the eyes. Second, for upside or downside risk, the magnitude of the CoVaR value is systematically larger than the corresponding VaR value for all. This graphical evidence is also corroborated by the results of the KS bootstrapping test shown in Table 4, leading to the conclusion that for all market pairs considered, both upside and downside risk spillovers exist, or the extreme movement in one market causes VaR to move significantly in the same direction.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics and tests for downside and upside VaR and CoVaR for stock returns

| Downside | Upside | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VaR | CoVaR | H0: CoVaR = VaR | VaR | CoVaR | H0: CoVaR = VaR | |

| H1: CoVaR < VaR | H1: CoVaR > VaR | |||||

| CAC40BVSP | − 0.0642 | − 0.1171 | 0.5628 | 0.0579 | 0.1 | 0.5301 |

| (0.0658) | (0.1196) | [0.0000] | (0.0583) | (0.1012) | [0.0000] | |

| DAXBVSP | − 0.0642 | − 0.1137 | 0.5464 | 0.0579 | 0.0998 | 0.5246 |

| (0.0658) | (0.1162) | [0.0000] | (0.0583) | (0.1009) | [0.0000] | |

| FTSE100BVSP | − 0.0642 | − 0.1163 | 0.5628 | 0.0579 | 0.0993 | 0.5191 |

| (0.0658) | (0.1188) | [0.0000] | (0.0583) | (0.1005) | [0.0000] | |

| N225BVSP | − 0.0642 | − 0.1059 | 0.4809 | 0.0579 | 0.0975 | 0.5027 |

| (0.0658) | (0.1082) | [0.0000] | (0.0583) | (0.0987) | [0.0000] | |

| S &P500BVSP | − 0.0642 | − 0.1177 | 0.5683 | 0.0579 | 0.1002 | 0.5355 |

| (0.0658) | (0.1202) | [0.0000] | (0.0583) | (0.1013) | [0.0000] | |

| SSEBVSP | − 0.0642 | − 0.109 | 0.5027 | 0.0579 | 0.0964 | 0.4973 |

| (0.0658) | (0.1114) | [0.0000] | (0.0583) | (0.0975) | [0.0000] | |

| BVSPCAC40 | − 0.0623 | − 0.1985 | 0.6612 | 0.0599 | 0.1946 | 0.6667 |

| (0.0552) | (0.1761) | [0.0000] | (0.0537) | (0.1734) | [0.0000] | |

| DAXCAC40 | − 0.0623 | − 0.203 | 0.6721 | 0.0599 | 0.1996 | 0.6721 |

| (0.0552) | (0.1801) | [0.0000] | (0.0537) | (0.1778) | [0.0000] | |

| FTSE100CAC40 | − 0.0623 | − 0.203 | 0.6721 | 0.0599 | 0.1996 | 0.6721 |

| (0.0552) | (0.1801) | [0.0000] | (0.0537) | (0.1778) | [0.0000] | |

| N225CAC40 | − 0.0623 | − 0.1873 | 0.6448 | 0.0599 | 0.1957 | 0.6721 |

| (0.0552) | (0.1662) | [0.0000] | (0.0537) | (0.1744) | [0.0000] | |

| SSECAC40 | − 0.0623 | − 0.1702 | 0.612 | 0.0599 | 0.1782 | 0.6448 |

| (0.0552) | (0.151) | [0.0000] | (0.0537) | (0.1588) | [0.0000] | |

| BVSPDAX | − 0.0846 | − 0.3121 | 0.6667 | 0.0622 | 0.2307 | 0.6721 |

| (0.0846) | (0.3148) | [0.0000] | (0.0642) | (0.2347) | [0.0000] | |

| CAC40DAX | − 0.0846 | − 0.3496 | 0.7104 | 0.0622 | 0.2391 | 0.6831 |

| (0.0846) | (0.3527) | [0.0000] | (0.0642) | (0.2432) | [0.0000] | |

| FTSE100DAX | − 0.0846 | − 0.3495 | 0.7104 | 0.0622 | 0.2389 | 0.6831 |

| (0.0846) | (0.3526) | [0.0000] | (0.0642) | (0.243) | [0.0000] | |

| N225DAX | − 0.0846 | − 0.3226 | 0.6831 | 0.0622 | 0.2324 | 0.6776 |

| (0.0846) | (0.3254) | [0.0000] | (0.0642) | (0.2364) | [0.0000] | |

| S &P500DAX | − 0.0846 | − 0.3439 | 0.6995 | 0.0622 | 0.2363 | 0.6831 |

| (0.0846) | (0.3469) | [0.0000] | (0.0642) | (0.2404) | [0.0000] | |

| SSEDAX | − 0.0846 | − 0.3076 | 0.6557 | 0.0622 | 0.2022 | 0.612 |

| (0.0846) | (0.3102) | [0.0000] | (0.0642) | (0.2059) | [0.0000] | |

| BVSPFTSE100 | − 0.054 | − 0.1171 | 0.6612 | 0.0421 | 0.0863 | 0.6175 |

| (0.0386) | (0.0842) | [0.0000] | (0.0315) | (0.0634) | [0.0000] | |

| CAC40FTSE100 | − 0.054 | − 0.1199 | 0.6721 | 0.0421 | 0.0884 | 0.623 |

| (0.0386) | (0.0863) | [0.0000] | (0.0315) | (0.0649) | [0.0000] | |

| DAXFTSE100 | − 0.054 | − 0.1199 | 0.6721 | 0.0421 | 0.0883 | 0.623 |

| (0.0386) | (0.0862) | [0.0000] | (0.0315) | (0.0649) | [0.0000] | |

| N225FTSE100 | − 0.054 | − 0.1151 | 0.6557 | 0.0421 | 0.0873 | 0.6175 |

| (0.0386) | (0.0828) | [0.0000] | (0.0315) | (0.0642) | [0.0000] | |

| S &P500FTSE100 | − 0.054 | − 0.1187 | 0.6667 | 0.0421 | 0.0878 | 0.623 |

| (0.0386) | (0.0854) | [0.0000] | (0.0315) | (0.0645) | [0.0000] | |

| BVSPN225 | − 0.0481 | − 0.1412 | 0.7869 | 0.0534 | 0.1959 | 0.8415 |

| (0.0313) | (0.0911) | [0.0000] | (0.034) | (0.1257) | [0.0000] | |

| CAC40N225 | − 0.0481 | − 0.1748 | 0.8361 | 0.0534 | 0.2133 | 0.8798 |

| (0.0313) | (0.1128) | [0.0000] | (0.034) | (0.1369) | [0.0000] | |

| DAXN225 | − 0.0481 | − 0.1778 | 0.8361 | 0.0534 | 0.212 | 0.8798 |

| (0.0313) | (0.1147) | [0.0000] | (0.034) | (0.1361) | [0.0000] | |

| FTSE100N225 | − 0.0481 | − 0.1775 | 0.8361 | 0.0534 | 0.2129 | 0.8798 |

| (0.0313) | (0.1145) | [0.0000] | (0.034) | (0.1367) | [0.0000] | |

| S &P500N225 | − 0.0481 | − 0.177 | 0.8361 | 0.0534 | 0.1898 | 0.8361 |

| (0.0313) | (0.1142) | [0.0000] | (0.034) | (0.1218) | [0.0000] | |

| BVSPS &P500 | − 0.0673 | − 0.3139 | 0.8798 | 0.0399 | 0.1363 | 0.8251 |

| (0.0587) | (0.2718) | [0.0000] | (0.0346) | (0.1177) | [0.0000] | |

| DAXS &P500 | − 0.0673 | − 0.3131 | 0.8798 | 0.0399 | 0.138 | 0.8306 |

| (0.0587) | (0.2711) | [0.0000] | (0.0346) | (0.1192) | [0.0000] | |

| FTSE100S &P500 | − 0.0673 | − 0.3118 | 0.8743 | 0.0399 | 0.1377 | 0.8306 |

| (0.0587) | (0.27) | [0.0000] | (0.0346) | (0.1189) | [0.0000] | |

| N225S &P500 | − 0.0673 | − 0.2909 | 0.8743 | 0.0399 | 0.1219 | 0.8197 |

| (0.0587) | (0.2519) | [0.0000] | (0.0346) | (0.1053) | [0.0000] | |

| SSES &P500 | − 0.0673 | − 0.2979 | 0.8743 | 0.0399 | 0.1121 | 0.7923 |

| (0.0587) | (0.2579) | [0.0000] | (0.0346) | (0.0968) | [0.0000] | |

| BVSPSSE | − 0.0393 | − 0.1348 | 0.9781 | 0.0405 | 0.1498 | 0.9836 |

| (0.0151) | (0.0513) | [0.0000] | (0.0151) | (0.0565) | [0.0000] | |

| CAC40SSE | − 0.0393 | − 0.1376 | 0.9781 | 0.0405 | 0.1513 | 0.9836 |

| (0.0151) | (0.0523) | [0.0000] | (0.0151) | (0.0571) | [0.0000] | |

| DAXSSE | − 0.0393 | − 0.1507 | 0.9836 | 0.0405 | 0.1456 | 0.9781 |

| (0.0151) | (0.0573) | [0.0000] | (0.0151) | (0.0549) | [0.0000] | |

| S &P500SSE | − 0.0393 | − 0.1614 | 0.9836 | 0.0405 | 0.1375 | 0.9781 |

| (0.0151) | (0.0613) | [0.0000] | (0.0151) | (0.0519) | [0.0000] | |

Standard errors for VaR and CoVaR are in brackets. The p values for the Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) statistic are in squared brackets

Turning to the differences in Figs. 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, we focus on dissimilarities across groups. First, we notice that the dispersion of CoVaR and VaR values at a given time can vary across groups. A larger distance between CoVaR at 95% and CoVaR at 99% reveals that risk spillover is more sensitive to quantile selection. A larger distance between CoVaR and VaR of the same confidence level indicates that the spillover effect is more significant. Such high sensitivity to quantile selection and strong spillover significance are evident in almost all groups, though with varying degrees, consistent with observations of complex market movements [14, 15, 40, 61]. Among the groups considered, the figures of the group of Brazil show the least dispersion, yet they still pass the test of spillover significance, as shown in Table 4. Second, although for most groups, the downside CoVaR is roughly symmetrical to the upside CoVaR dynamically. Germany, the US exhibit strong asymmetries, with their downside CoVaR values significantly larger than the upside, especially when at extremes, while other countries show only moderate or no asymmetries. Such evidence corroborates testing results on the contagion channel, as all pairs with the wealth channel as the main channel contain one market from Germany and the USA. Evidence also supports the finding of a recent study [64], where the time-varying asymmetric tail dependence stronger in the lower quantile is also captured in the US market. Third, although abrupt changes in mid-March are evident in almost all groups, likely reflecting the effects of fear of COVID-19, the group of China seems to be an exception. Unlike other groups, where the CoVaR and VaR values reach the highest magnitude in mid-March, the group of China has the highest magnitude in July. Fourth, after the CoVaR and VaR values peaked, the speed at which they return to normal is different between groups, with the group of Japan recovering noticeably slower than other countries. This is likely due to the dubious efficacy of Japan’s fiscal and monetary policy in response to the COVID-19 shock, as noted by [16].

Table 4 presents additional information about CoVaR and VaR values that reveals more details about both upside and downside risk spillover effects. For either side, the averages of CoVaR and VaR values are presented, where standard errors are given in brackets. Then, we perform a test using CoVaR and VaR at the confidence level to compare if CoVaR values are significantly higher than VaR values (Test 3), confirming the graphical evidence mentioned in Figs. 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12. In addition, we perform Test 4 to examine whether there is asymmetry between opposite directions for the downside/upside risk spillover of a pair of markets. The results of the upside (downside) risk spillover effects are reported in the upper-right (lower-left) part of Table 5, where the test statistics and p-values (in square brackets) are given. Upward arrows () and downward arrows () indicate the direction in which the risk spillover effects are strongest. Consistent with other studies, emerging economies like Brazil witness stronger risk spillovers coming in than giving out, while other countries show mixed results. It is observed that most pairs of markets show stronger spillover effect in the same direction, no matter whether upside or downside risk is considered. However, the US market shows some distinguished features. When considering downside risk, it always transmits stronger spillovers than it receives, yet for upside risk, it receives stronger spillovers from Germany, Japan, and China and remains to be a net transmitter towards other markets. This switching role feature is unseen for other markets and possibly relevant to the dominant role played by the US stock market [26, 31]. Notably, it is well documented in the literature that the impact of volatility spillovers from the US stock market to other markets is highly visible especially during crises (e.g., [33, 39, 62]), yet there is also evidence on spillovers along the reverse direction, i.e., from other markets to US [54]. Therefore, our findings offer more insight by recognizing that upside and downside spillover effects could have differing patterns regarding the US stock market. The downside risk spillover stronger toward the US could be related to heightened uncertainty prospects in other important markets, as a recent study [28] found the S &P500 index volatility to be a net recipient of important EPU index spillovers, and the relationship is more pronounced considering bad volatility. The evidence of our study is also consistent with another study on the COVID-19 period [4], where China and Japan are detected to transmit more spillovers than they receive.

Table 5.

Asymmetric risk spillovers between opposite directions of stock returns

| A | BVSP | CAC40 | DAX | FTSE100 | N225 | S &P500 | SSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | |||||||

| BVSP | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | |

| [0.0000] | [0.0000] | [0.0000] | [0.0000] | [0.0000] | [0.0000] | ||

| CAC40 | 1.0000 | 0.7923 | 0.0000 | 0.9945 | 1.0000 | ||

| [0.0000] | [0.0000] | [1.0000] | [0.0000] | [0.0000] | |||

| DAX | 1.0000 | 0.9727 | 0.0000 | 0.7541 | 0.0055 | 0.8852 | |

| [0.0000] | [0.0000] | [1.0000] | [0.0000] | [0.9946] | [0.0000] | ||

| FTSE100 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | ||

| [0.0000] | [1.0000] | [1.0000] | [0.0000] | [0.0000] | |||

| N225 | 1.0000 | 0.9891 | 0.2350 | 1.0000 | 0.0437 | ||

| [0.0000] | [0.0000] | [0.0000] | [0.0000] | [0.7049] | |||

| S &P500 | 1.0000 | 0.8415 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9836 | ||

| [0.0000] | [0.0000] | [0.0000] | [0.0000] | [0.0000] | |||

| SSE | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.8689 | 0.0546 | |||

| [0.0000] | [0.0000] | [0.0000] | [0.5790] | ||||

The test statistics and p-values (in square brackets) of the asymmetric risk spillover test for the upside in the direction A to B (upper triangular) and the results of the asymmetric risk spillover test for the downside in the direction B to A (lower triangular). The upward arrows () indicate that the spillover effect is stronger from B to A than from A to B. The downward arrows () indicate that the opposite direction is with stronger spillover

We take a further step to measure the complexity of these risk spillover series and investigate whether the risk spillovers that a country receives after the COVID-19 outbreak has changed in terms of complex behaviour. As shown in Table 6, the sample entropy values of dynamic CoVaR series at 99% for both subsample periods are calculated, setting , where is the standard deviation of the CoVaR series considered. As seen, the estimated sample entropy values can be quite different across countries and periods, however, for a particular country, the sample entropy values of the risk spillovers transmitted from different countries do not differ much. A first glance of the table suggests there to be a shift in level of complexity in both upside and downside risk spillover dynamics in most series as a consequence of the COVID-19 outbreak. To formally investigate the issue, we treat the sample entropy values of one-side risk spillover with same recipient in a given period as one population and then apply two-sample t-test to compare pre- and post-COVID-19 populations. The test results including the t-statistic and associated p-value are displayed in Table 7. Except for the case of downside risk spillover received by Germany, the null hypothesis is strongly rejected for all other cases, which supports that the means of sample entropy values are significantly different before and after the outbreak of COVID-19 in most cases. More specifically, when we look into the sample entropy values as given in Table 6, higher mean of sample entropies is found in pre-COVID-19 sample for all risk spillover series, except for the Chinese market group. In fact, the inverse pattern is observed in this group, i.e., higher mean is found in post-COVID-19 sample rather than pre-COVID-19 one. This is another piece of evidence that the dynamics of the Chinese market possess a certain degree of distinction, consistent with previous results and other studies [60]. As an decrease of the sample entropy means that the likelihood of repeating patterns is increasing. We can conclude the effects of the outbreak of COVID-19 is mostly reducing the degree of randomness or irregularity in the risk spillover dynamics that received by a country.

Table 6.

Sample entropies of the time-varying CoVaRs at confidence level of 99%

| Pre-COVID-19 | In-COVID-19 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Downside | Upside | Downside | Upside | |

| CAC40->BVSP | 0.6174 | 0.9505 | 0.5572 | 0.5572 |

| DAX->BVSP | 0.6174 | 0.9447 | 0.5572 | 0.5572 |

| FTSE100->BVSP | 0.6174 | 0.9577 | 0.5572 | 0.5572 |

| N225->BVSP | 0.5718 | 1.0039 | 0.5572 | 0.5572 |

| SP500->BVSP | 0.6238 | 0.9393 | 0.5572 | 0.5572 |

| SSE->BVSP | 0.5575 | 0.9683 | 0.5572 | 0.5572 |

| BVSP->CAC40 | 1.4253 | 1.5405 | 0.6276 | 0.5680 |

| DAX->CAC40 | 1.4384 | 1.4239 | 0.6262 | 0.5629 |

| FTSE100->CAC40 | 1.4384 | 1.4526 | 0.6262 | 0.5629 |

| N225->CAC40 | 1.4253 | 1.5193 | 0.6297 | 0.5676 |

| SSE->CAC40 | 1.4253 | 1.5105 | 0.6335 | 0.5652 |

| BVSP->DAX | 0.7212 | 0.8954 | 0.7313 | 0.7106 |

| CAC40->DAX | 0.6852 | 0.7445 | 0.7275 | 0.7117 |

| FTSE100->DAX | 0.6877 | 0.7687 | 0.7275 | 0.7117 |

| N225->DAX | 0.7756 | 0.8679 | 0.7300 | 0.7106 |

| SP500->DAX | 0.6890 | 0.7795 | 0.7282 | 0.7088 |

| SSE->DAX | 0.7503 | 0.8520 | 0.7307 | 0.7049 |

| BVSP->FTSE100 | 1.7227 | 1.7570 | 0.7907 | 0.7412 |

| CAC40->FTSE100 | 1.9630 | 1.7970 | 0.7910 | 0.7397 |

| DAX->FTSE100 | 1.9197 | 1.7973 | 0.7910 | 0.7390 |

| N225->FTSE100 | 1.7852 | 1.7162 | 0.7892 | 0.7422 |

| SP500->FTSE100 | 1.9197 | 1.8135 | 0.7903 | 0.7408 |

| BVSP->N225 | 0.9984 | 1.0288 | 0.4596 | 0.4596 |

| CAC40->N225 | 1.0288 | 1.0518 | 0.4596 | 0.4596 |

| DAX->N225 | 1.0458 | 1.0187 | 0.4596 | 0.4596 |

| FTSE100->N225 | 1.0214 | 1.0365 | 0.4596 | 0.4596 |

| SP500->N225 | 1.0462 | 1.0163 | 0.4596 | 0.4596 |

| BVSP->SP500 | 0.6147 | 0.6921 | 0.2281 | 0.2383 |

| DAX->SP500 | 0.6157 | 0.6995 | 0.2285 | 0.2373 |

| FTSE100->SP500 | 0.6157 | 0.6960 | 0.2285 | 0.2377 |

| N225->SP500 | 0.6271 | 0.6904 | 0.2281 | 0.2410 |

| SSE->SP500 | 0.6263 | 0.7019 | 0.2283 | 0.2431 |

| BVSP->SSE | 0.4382 | 0.6539 | 1.3887 | 1.3887 |

| CAC40->SSE | 0.3864 | 0.5370 | 1.3887 | 1.3887 |

| DAX->SSE | 0.3870 | 0.5319 | 1.3887 | 1.3887 |

| SP500->SSE | 0.3864 | 0.5216 | 1.3887 | 1.3887 |

Table 7.

Test for changes in the complexity of the risk dynamic spillovers received by the stock market

| Downside | Upside | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T-stat | p value | T-stat | p value | |

| BVSP | 3.7518* | 0.0038 | 42.1172* | 0.0000 |

| CAC40 | 228.6517* | 0.0000 | 42.1169* | 0.0000 |

| DAX | − 0.7094 | 0.4943 | 4.3036* | 0.0016 |

| FTSE100 | 23.3361* | 0.0000 | 58.6114* | 0.0000 |

| N225 | 64.1751* | 0.0000 | 88.3658* | 0.0000 |

| SP500 | 140.8513* | 0.0000 | 188.3819* | 0.0000 |

| SSE | − 76.7193* | 0.0000 | − 26.6241* | 0.0000 |

The p values (in square brackets) below 0.05 reject the null hypothesis that the means of sample entropy are similar during pre-COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 periods. An asterisk (*) denotes the level of significance

Conclusion and future work

The main goal of this study was to analyse stock markets contagion facing the COVID-19 pandemic event. Following the definition of [21], the contagion effect has been analysed by three questions: Does the contagion exist? If so, what is the main propagation channel and how are the risk spillovers like both upside and downside dynamically? Are the complex dynamics in risk spillovers affected by the shock of COVID-19? This study covers the period from 4 January 2019 to 30 December 2020, consisting of the pre-COVID-19 period and the in-COVID-19 period with the breakpoint at 30 January 2020. A selection of a range of developed and emerging markets is considered, namely the US (S &P500), the UK (FTSE100), France (CAC40), Germany (DAX), Japan (N225), Brazil (BVSP), China (SSE). Implementing copula approaches, we estimate Kendall’s and Spearman’s to characterize market comovements and consequently detect the existence of contagion. We then calculate tail-dependence differences to identify the main contagion channels. Adding a dynamic perspective to the analysis, we assess both upside and downside risk spillovers using time-varying Copula-based CoVaR and use sample entropy to measure complexity in spillover dynamics.

The main findings of this study are as follows. First, consistent with most empirical studies, it is observed that stock market comovement relationships before the outbreak of COVID-19 reflect their geographic closeness generally, with the US market occupying a central position, significantly associated with all other markets. After the hit of the disease, the number of significantly comoving market pairs rises to all. Second, contagion is widely present among the stock markets during the COVID-19 pandemic. Of 21 market pairings, 18 are found to show substantial contagion, with exceptions being the US-France, UK-China, Japan-China pairs. Third, among pairs where contagion is detected, 11 pairs are shown to have portfolio rebalancing as the main propagation channel, and 5 pairs are prone to wealth constraint channel. A finding different from studies of previous crises is that the US market is susceptible to the wealth constraint channel. Fourth, in the dynamic risk spillover analysis, all market pairs show significant bilateral upside and downside spillovers, which are generally sensitive to quantile selection. When pairs are grouped by receiver markets, we find that China reaches a peak spillover of risks several months later than others, while Japan exhibits a relatively slow recovery rate after the peak. The USA and Germany show a strong asymmetry in which negative spillovers outweigh positive spillovers in magnitude, while others show only modest or no asymmetries. The US also shows a distinguished feature, being stronger at upside risk spillovers to all other countries, while its downside risk spillovers are weaker when the recipients are Germany, Japan and China. Fifth, upon the shock of COVID-19, complexity measured by sample entropy takes a significant shift in risk spillover dynamics for most recipient countries. This shift is downward for most but upward for China.

We acknowledge that there are some limitations in the current study. One such limitation is that due to the length of data, we do not tackle the question whether the market behaviour changes identified during COVID-19 are temporary or permanent. Also, delayed risk spillover effects are not taken into consideration, and how the spillover further goes through sectors within each market is untouched. Another limitation is that we only split the data into 2 windows, alternative windows may be utilized to strengthen the robustness of analysis, such as sliding windows. These are all interesting issues that we leave for future work to explore. And there are other statistics that quantify serial relationships that can be introduced into future work, for example, the dynamic transfer entropy method [51] realized by sliding windows.

The findings of this study may have some important implications for investors and policy makers confronting the COVID-19 pandemics. In particular, for investors, understanding the bilateral contagion behaviours of global equity financial markets helps to explore more opportunities for resource allocation, encourage new ideas for portfolio diversification, and conduct better dynamic portfolio risk management. For policy makers, it can help to adopt suitable policy measures to strengthen the resilience of their markets to external shocks emanating from their countries. Timely policy adjustments are also necessary to keep up with the dynamics of risk spillovers to contain the crisis.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 72001022); the Postdoctoral Research Foundation of China (No. 2020M680791); and the Annual project of Renmin University of China -New Teacher Initiation Fund Project (No. 2021030194).

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 72001022); Postdoctoral Research Foundation of China (No. 2020M680791); Annual project of Renmin University of China -New Teacher Initiation Fund Project (No. 2021030194).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or nonfinancial interests to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Abadie A. Bootstrap tests for distributional treatment effects in instrumental variable models. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2002;97(457):284–292. doi: 10.1198/016214502753479419. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abduraimova K. Contagion and tail risk in complex financial networks. J. Bank. Finance. 2022;143:106560. doi: 10.1016/j.jbankfin.2022.106560. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adrian T, Brunnermeier MK. CoVaR. Am. Econ. Rev. 2016;106(7):1705–1741. doi: 10.1257/aer.20120555. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akhtaruzzaman M, Boubaker S, Sensoy A. Financial contagion during COVID-19 crisis. Financ. Res. Lett. 2021;38:101604. doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2020.101604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aloui R, Hammoudeh S, Nguyen DK. A time-varying copula approach to oil and stock market dependence: The case of transition economies. Energy Econ. 2013;39:208–221. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2013.04.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bekaert G, Ehrmann M, Fratzscher M, Mehl A. The global crisis and equity market contagion. J. Financ. 2014;69(6):2597–2649. doi: 10.1111/jofi.12203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bekaert G, Engstrom E, Ermolov A. Bad environments, good environments: a non-Gaussian asymmetric volatility model. J. Econom. 2015;186(1):258–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jeconom.2014.06.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.BenMim I, BenSaïda A. Financial contagion across major stock markets: a study during crisis episodes. N. Am. J. Econ. Finance. 2019;48:187–201. doi: 10.1016/j.najef.2019.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernal O, Gnabo J-Y, Guilmin G. Assessing the contribution of banks, insurance and other financial services to systemic risk. J. Bank. Finance. 2014;47:270–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jbankfin.2014.05.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Billio M, Getmansky M, Lo AW, Pelizzon L. Econometric measures of connectedness and systemic risk in the finance and insurance sectors. J. Financ. Econ. 2012;104(3):535–559. doi: 10.1016/j.jfineco.2011.12.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bisias D, Flood M, Lo AW, Valavanis S. A Survey of Systemic Risk Analytics. Annu. Rev. Financ. Econ. 2012;4(1):255–296. doi: 10.1146/annurev-financial-110311-101754. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boland J, Hurd TR, Pivato M, Seco L. Measures of dependence for multivariate lévy distributions. AIP Conf. Proc. 2001;553(1):289–295. doi: 10.1063/1.1358198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyer BH, Kumagai T, Yuan K. How do crises spread? Evidence from accessible and inaccessible stock indices. J. Financ. 2006;61(2):957–1003. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6261.2006.00860.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cai Z, Fang Y, Tian D. Assessing tail risk using expectile regressions with partially varying coefficients. J. Manag. Sci. Eng. 2018;3(4):183–213. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen J, Han Q, Ryu D, Tang J. Does the world smile together? a network analysis of global index option implied volatilities. J. Int. Finan. Markets. Inst. Money. 2022;77:101497. doi: 10.1016/j.intfin.2021.101497. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christensen, J.H.E., Spiegel, M.M.: Central Bank Credibility During COVID-19: Evidence from Japan. Working Paper Series 2021-24, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (2021)

- 17.Corbet S, Larkin C, Lucey B. The contagion effects of the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from gold and cryptocurrencies. Financ. Res. Lett. 2020;35:101554. doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2020.101554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diebold FX, Yılmaz K. On the network topology of variance decompositions: measuring the connectedness of financial firms. J. Econom. 2014;182(1):119–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jeconom.2014.04.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dungey M, Gajurel D. Equity market contagion during the global financial crisis: Evidence from the world’s eight largest economies. Econ. Syst. 2014;38(2):161–177. doi: 10.1016/j.ecosys.2013.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Embrechts, P., Lindskog, F., Mcneil, A.: Modelling Dependence with Copulas and Applications to Risk Management. In: Handbook of Heavy Tailed Distributions in Finance, pp. 329–384. Elsevier (2003)

- 21.Forbes KJ, Rigobon R. No contagion, only interdependence: measuring stock market comovements. J. Financ. 2002;57(5):2223–2261. doi: 10.1111/0022-1082.00494. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gharib C, Mefteh-Wali S, Jabeur SB. The bubble contagion effect of COVID-19 outbreak: evidence from crude oil and gold markets. Financ. Res. Lett. 2021;38:101703. doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2020.101703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Girardi G, Tolga Ergün A. Systemic risk measurement: multivariate GARCH estimation of CoVaR. J. Bank. Finance. 2013;37(8):3169–3180. doi: 10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.02.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gontis V. Order flow in the financial markets from the perspective of the Fractional Lévy stable motion. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2022;105:106087. doi: 10.1016/j.cnsns.2021.106087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodell JW, Goutte S. Co-movement of COVID-19 and Bitcoin: evidence from wavelet coherence analysis. Financ. Res. Lett. 2021;38:101625. doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2020.101625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gunay S, Can G. The source of financial contagion and spillovers: an evaluation of the covid-19 pandemic and the global financial crisis. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(1):e0261835. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0261835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harjoto, M. A., Rossi, F.: Market reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from emerging markets. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. (2021)

- 28.He F, Wang Z, Yin L. Asymmetric volatility spillovers between international economic policy uncertainty and the US stock market. N. Am. J. Econ. Finance. 2020;51:101084. doi: 10.1016/j.najef.2019.101084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horta P, Lagoa S, Martins L. Unveiling investor-induced channels of financial contagion in the 2008 financial crisis using copulas. Quant. Finance. 2016;16(4):625–637. doi: 10.1080/14697688.2015.1033447. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horta P, Mendes C, Vieira I. Contagion effects of the subprime crisis in the European NYSE Euronext markets. Port. Econ. J. 2010;9(2):115–140. doi: 10.1007/s10258-010-0056-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iwanicz-Drozdowska M, Rogowicz K, Kurowski Ł, Smaga P. Two decades of contagion effect on stock markets: Which events are more contagious? J. Financ. Stab. 2021;55:100907. doi: 10.1016/j.jfs.2021.100907. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jayech S. The contagion channels of July–August-2011 stock market crash: a DAG-copula based approach. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2016;249(2):631–646. doi: 10.1016/j.ejor.2015.08.061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jin X, An X. Global financial crisis and emerging stock market contagion: a volatility impulse response function approach. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2016;36:179–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ribaf.2015.09.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Joe, H.: Multivariate models and dependence concepts, volume 73 of Monographs on statistics and applied probability. Chapman and Hall, London (1997)

- 35.Kodres LE, Pritsker M. A rational expectations model of financial contagion. J. Financ. 2002;57(2):769–799. doi: 10.1111/1540-6261.00441. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kyle AS, Xiong W. Contagion as a wealth effect. J. Financ. 2001;56(4):1401–1440. doi: 10.1111/0022-1082.00373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lahmiri S, Bekiros S. Disturbances and complexity in volatility time series. Chaos Solitons Fract. 2017;105:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2017.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lambert, P. and Laurent, S.: Modelling financial time series using garch-type models with a skewed student distribution for the innovations (2001)

- 39.Li Y, Giles DE. Modelling volatility spillover effects between developed stock markets and asian emerging stock markets. Int. J. Finance Econ. 2015;20(2):155–177. doi: 10.1002/ijfe.1506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu Y, Wang J. Multivariate multiscale entropy of financial markets. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2017;52:77–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cnsns.2017.04.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mensi W, Sensoy A, Vo XV, Kang SH. Impact of COVID-19 outbreak on asymmetric multifractality of gold and oil prices. Resour. Policy. 2020;69:101829. doi: 10.1016/j.resourpol.2020.101829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]