Abstract

Background

The success of elective colorectal surgery is mainly influenced by the surgical procedure and postoperative complications. The most serious complications include anastomotic leakages and surgical site infections (SSI)s, which can lead to prolonged recovery with impaired long‐term health. Compared with other abdominal procedures, colorectal resections have an increased risk of adverse events due to the physiological bacterial colonisation of the large bowel. Preoperative bowel preparation is used to remove faeces from the bowel lumen and reduce bacterial colonisation. This bowel preparation can be performed mechanically and/or with oral antibiotics. While mechanical bowel preparation alone is not beneficial, the benefits and harms of combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation is still unclear.

Objectives

To assess the evidence for the use of combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation for preventing complications in elective colorectal surgery.

Search methods

We searched MEDLINE, Embase, CENTRAL and trial registries on 15 December 2021. In addition, we searched reference lists and contacted colorectal surgery organisations.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of adult participants undergoing elective colorectal surgery comparing combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation (MBP+oAB) with either MBP alone, oAB alone, or no bowel preparation (nBP). We excluded studies in which no perioperative intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis was given.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures as recommended by Cochrane. Pooled results were reported as mean difference (MD) or risk ratio (RR) and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) using the Mantel‐Haenszel method. The certainty of the evidence was assessed with GRADE.

Main results

We included 21 RCTs analysing 5264 participants who underwent elective colorectal surgery.

None of the included studies had a high risk of bias, but two‐thirds of the included studies raised some concerns. This was mainly due to the lack of a predefined analysis plan or missing information about the randomisation process.

Most included studies investigated both colon and rectal resections due to malignant and benign surgical indications. For MBP as well as oAB, the included studies used different regimens in terms of agent(s), dosage and timing. Data for all predefined outcomes could be extracted from the included studies. However, only four studies reported on side effects of bowel preparation, and none recorded the occurrence of adverse effects such as dehydration, electrolyte imbalances or the need to discontinue the intervention due to side effects.

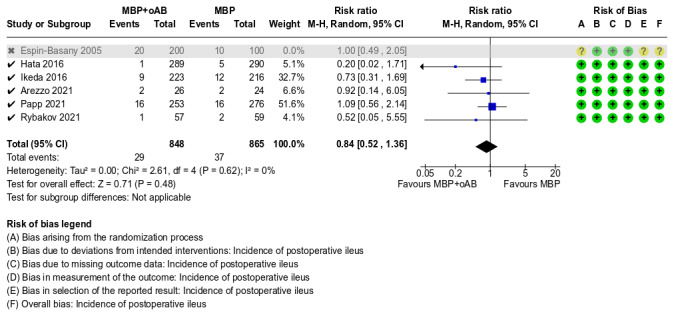

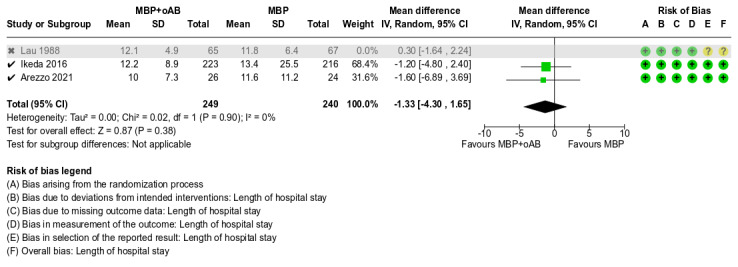

Seventeen trials compared MBP+oAB with sole MBP. The incidence of SSI could be reduced through MBP+oAB by 44% (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.74; 3917 participants from 16 studies; moderate‐certainty evidence) and the risk of anastomotic leakage could be reduced by 40% (RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.99; 2356 participants from 10 studies; moderate‐certainty evidence). No difference between the two comparison groups was found with regard to mortality (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.27 to 2.82; 639 participants from 3 studies; moderate‐certainty evidence), the incidence of postoperative ileus (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.32; 2013 participants from 6 studies, low‐certainty of evidence) and length of hospital stay (MD ‐0.19, 95% CI ‐1.81 to 1.44; 621 participants from 3 studies; moderate‐certainty evidence).

Three trials compared MBP+oAB with sole oAB. No difference was demonstrated between the two treatment alternatives in terms of SSI (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.34 to 2.21; 960 participants from 3 studies; very low‐certainty evidence), anastomotic leakage (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.21 to 3.45; 960 participants from 3 studies; low‐certainty evidence), mortality (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.30 to 3.50; 709 participants from 2 studies; low‐certainty evidence), incidence of postoperative ileus (RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.68 to 2.33; 709 participants from 2 studies; low‐certainty evidence) or length of hospital stay (MD 0.1 respectively 0.2, 95% CI ‐0.68 to 1.08; data from 2 studies; moderate‐certainty evidence).

One trial (396 participants) compared MBP+oAB versus nBP. The evidence is uncertain about the effect of MBP+oAB on the incidence of SSI as well as mortality (RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.33 to 1.23 respectively RR 0.20, 95% CI 0.01 to 4.22; low‐certainty evidence), while no effect on the risk of anastomotic leakages (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.33 to 2.42; low‐certainty evidence), the incidence of postoperative ileus (RR 1.18, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.81; low‐certainty evidence) or the length of hospital stay (MD 0.1, 95% CI ‐0.8 to 1; low‐certainty evidence) could be demonstrated.

Authors' conclusions

Based on moderate‐certainty evidence, our results suggest that MBP+oAB is probably more effective than MBP alone in preventing postoperative complications. In particular, with respect to our primary outcomes, SSI and anastomotic leakage, a lower incidence was demonstrated using MBP+oAB. Whether oAB alone is actually equivalent to MBP+oAB, or leads to a reduction or increase in the risk of postoperative complications, cannot be clarified in light of the low‐ to very low‐certainty evidence. Similarly, it remains unclear whether omitting preoperative bowel preparation leads to an increase in the risk of postoperative complications due to limited evidence.

Additional RCTs, particularly on the comparisons of MBP+oAB versus oAB alone or nBP, are needed to assess the impact of oAB alone or nBP compared with MBP+oAB on postoperative complications and to improve confidence in the estimated effect. In addition, RCTs focusing on subgroups (e.g. in relation to type and location of colon resections) or reporting side effects of the intervention are needed to determine the most effective approach of preoperative bowel preparation.

Keywords: Adult, Humans, Anastomotic Leak, Anastomotic Leak/drug therapy, Anastomotic Leak/prevention & control, Anti-Bacterial Agents, Anti-Bacterial Agents/administration & dosage, Anti-Bacterial Agents/therapeutic use, Colorectal Surgery, Colorectal Surgery/adverse effects, Ileus, Ileus/drug therapy, Ileus/prevention & control, Preoperative Care, Surgical Wound Infection, Surgical Wound Infection/drug therapy, Surgical Wound Infection/prevention & control

Plain language summary

Can combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation reduce the risk of complications after scheduled colon or rectal resections compared with purely mechanical, purely oral antibiotic or no bowel preparation?

Key messages

‐ A combined mechanical (using laxatives) and oral antibiotic bowel preparation probably reduces the occurrence of infections of the surgical site (wound infections and infections in the abdominal cavity) as well as the likelihood of anastomotic leakage (leakage of the suture connection of the bowel) compared with mechanical bowel preparation alone.

‐ Oral antibiotics alone might be as effective as a combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation, but this cannot be clearly determined based on the available data.

‐ Whether no bowel preparation compared with a combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation has an influence on the occurrence of postoperative complications could not be determined on the basis of the available data.

What is the purpose of preoperative bowel preparation? Due to the naturally bacterial colonisation of the large bowel, infections of the surgical site are more frequent after operations in which the large bowel is opened. To prevent these infections, bowel preparation before surgery is intended to reduce faecal contamination of the bowel and minimise bacterial colonisation.

How is the bowel preparation done? Preoperative bowel preparation can be done mechanically, using laxatives to rinse the bowel, or by taking oral antibiotics that lead to local decontamination. These two methods can be performed either alone or in combination.

What did we want to find out? We wanted to find out whether combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation compared with mechanical or oral antibiotic preparation alone or no bowel preparation has an effect on:

‐ the occurrence of surgical site infections

‐ the occurrence of anastomotic leakages

In addition, we wanted to find out whether combined bowel preparation had an effect on mortality, the occurrence of mild or severe postoperative complications, the likelihood of postoperative ileus (bowel motility disorder) or the length of hospital stay. Furthermore, we wanted to investigate whether side effects of the bowel preparation interventions differ between combination therapy and sole mechanical, sole oral antibiotic, or no bowel preparation.

What did we do? We searched for studies comparing combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation with sole mechanical, sole oral antibiotic, or no bowel preparation in patients scheduled for colon or rectal resection. We compared and summarised the results of the studies and rated our confidence in the evidence, based on factors such as study methods and sizes.

What did we find? We included 21 studies in which patients scheduled for colon or rectal resection were assigned either to a group receiving combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation or to a comparison group. The comparison group received mechanical bowel preparation alone in 17 studies, oral antibiotics alone in three studies, and no bowel preparation at all in one study. All participants received intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis during surgery. The studies included a total of 5968 participants, of whom 5264 were analysed. Most of the studies were conducted in industrialised countries in Europe or Asia. Bowel preparation was conducted over one to three days before surgery and the follow‐up period was 30 days in most of the studies. No industrial funding was reported by any of the studies, but only five of the 21 studies provided information on their funding. Overall, slightly more men (58%) than women (42%) were included. The average age of the study participants varied between 42 and 69 years.

We found moderate‐certainty evidence that combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation probably reduces the risk of surgical site infections and leakages without affecting mortality, the occurrence of postoperative ileus or length of hospital stay. When comparing combined bowel preparation with oral antibiotics alone or with no bowel preparation, we found low‐certainty evidence that there is little to no difference between the compared approaches.

What are the limitations of the evidence? There are different reasons why our confidence in the evidence is limited. We are moderately confident in the evidence regarding the reduction of surgical site infections through combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation, because different surgical strategies (in terms of surgical access and type and location of bowel resection) and also different methods of bowel preparation (in terms of agent, dose and timing) were used. We are also only moderately confident in the reduction of anastomotic leakage through combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation, because just a few cases occurred across the included studies. Regarding the comparison of combination therapy with oral antibiotics alone, we have little confidence in the evidence because not enough studies examined this issue to be certain about the results of our outcomes. In addition, there are some concerns about the methods used in the included studies. As there is only one study, we also have little confidence in the evidence comparing combined bowel preparation with no bowel preparation.

How up to date is this evidence? This evidence is up‐to‐date as of December 2021.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Summary of findings table ‐ Combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation versus mechanical bowel preparation alone.

| Combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation versus mechanical bowel preparation alone | ||||||

| Patient or population: Patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery Setting: Any type of hospital offering elective colorectal resections. Both single and multicentre studies are included Intervention: MBP+oAB Comparison: MBP | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with MBP | Risk with MBP+oAB | |||||

| SSI follow‐up: 30 days | 137 per 1000 | 77 per 1000 (58 to 101) | RR 0.56 (0.42 to 0.74) | 3917 (16 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | Combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation probably results in a reduction in surgical site infections. |

| Anastomotic leakage follow‐up: 30 days | 44 per 1000 | 26 per 1000 (16 to 43) | RR 0.60 (0.36 to 0.99) | 2356 (10 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderateb | Combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation may result in a reduction in anastomotic leakage. |

| Mortality follow‐up: 30 days | 18 per 1000 | 16 per 1000 (5 to 51) | RR 0.87 (0.27 to 2.82) | 639 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatec | Combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation may result in no difference in mortality. |

| Incidence of postoperative ileus follow‐up: 30 days | 49 per 1000 | 43 per 1000 (29 to 64) | RR 0.89 (0.59 to 1.32) | 2013 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowd,e | Combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation may result in no difference in incidence of postoperative ileus. |

| Length of hospital stay follow‐up: 30 days | MD 0.19 lower (1.81 lower to 1.44 higher) | ‐ | 621 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderated | Combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation may result in no difference in length of hospital stay. | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

| See interactive version of this table: https://gdt.gradepro.org/presentations/#/isof/isof_question_revman_web_431253836665717559. | ||||||

a The rating was downgraded by one level due to moderate heterogeneity between studies that could not be explained by the subgroup analyses; I2 =44%. b The rating was downgraded by one level for imprecision. Few events occurred in the included trials (28 in the intervention group and 52 in the control group) and the confidence intervals include both benefits and no effect. c The rating was downgraded by one level for imprecision. Few events occurred in the included studies (5 in the intervention group and 6 in the control group) and the confidence intervals include considerable benefit and harm. d The rating was downgraded by one level due to imprecision, as the confidence interval includes considerable benefit and harm. e The rating was downgraded by one level due to possible puplication bias, as small studies reported statistically significant benefits while larger studies showed a much smaller and statistically non‐significant effect.

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings table ‐ Combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation versus oral antibiotics alone.

| Combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation versus oral antibiotics alone | ||||||

| Patient or population: Patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery Setting: Any type of hospital offering elective colorectal resections. Both single and multicentre studies are included Intervention: MBP+oAB Comparison: oAB | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with oAB | Risk with MBP+oAB | |||||

| Surgical site infections follow‐up: 30 days | 68 per 1000 | 59 per 1000 (23 to 151) | RR 0.87 (0.34 to 2.21) | 960 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | Combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation may have no effect on surgical site infections, and the evidence is very uncertain. |

| Anastomotic leakage follow‐up: 30 days | 25 per 1000 | 21 per 1000 (5 to 86) | RR 0.84 (0.21 to 3.45) | 960 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,c | Combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation may result in no difference in anastomotic leakage. |

| Mortality follow‐up: 30 days | 14 per 1000 | 14 per 1000 (4 to 49) | RR 1.02 (0.30 to 3.50) | 709 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,c | Combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation may result in no difference in mortality. |

| Incidence of postoperative ileus follow‐up: 30 days | 47 per 1000 | 59 per 1000 (32 to 111) | RR 1.25 (0.68 to 2.33) | 709 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,c | Combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation may result in no difference in the incidence of postoperative ileus. |

| Length of hospital stay follow‐up: 30 days | In two studies, the reported mean difference between groups was 0.1 and 0.2 (95% CI ‐0.68 to 1.08) days, respectively. | (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | Combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation probably results in little to no difference in length of hospital stay. | ||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

| See interactive version of this table: https://gdt.gradepro.org/presentations/#/isof/isof_question_revman_web_431253847765418810. | ||||||

a The rating was downgraded by one level because of some concerns about risk of bias, as information on a predefined analysis plan could not be identified for any of the included studies. b The rating was downgraded by one level due to moderate heterogeneity between studies; I2 =69%. c The rating was downgraded by one level due to imprecision, as the confidence interval includes considerable benefit and harm.

Summary of findings 3. Summary of findings table ‐ Combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation versus no bowel preparation.

| Combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation versus no bowel preparation | ||||||

| Patient or population: Patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery Setting: Any type of hospital offering elective colorectal resections. Both single and multicentre studies are included Intervention: MBP+oAB Comparison: nBP | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with nBP | Risk with MBP+oAB | |||||

| Surgical site infections follow‐up: 30 days | 105 per 1000 | 66 per 1000 (35 to 129) | RR 0.63 (0.33 to 1.23) | 396 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | Combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation may result in little to no difference in surgical site infections. |

| Anastomotic leakage follow‐up: 30 days | 40 per 1000 | 36 per 1000 (13 to 97) | RR 0.89 (0.33 to 2.42) | 396 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | Combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation may result in no difference in anastomotic leakage. |

| Mortality follow‐up: 30 days | 10 per 1000 | 2 per 1000 (0 to 42) | RR 0.20 (0.01 to 4.22) | 396 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | Combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation may result in little to no difference in mortlaity. |

| Incidence of postoperative ileus follow‐up: 30 days | 160 per 1000 | 189 per 1000 (123 to 290) | RR 1.18 (0.77 to 1.81) | 396 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | Combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation may result in no difference in incidence of postoperative ileus. |

| Length of hospital stay follow‐up: 30 days | MD 0.1 higher (0.8 lower to 1 higher) | ‐ | 396 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | Combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation may result in no difference in length of hospital stay. | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

| See interactive version of this table: https://gdt.gradepro.org/presentations/#/isof/isof_question_revman_web_431253860479140670. | ||||||

a The rating was downgraded by two levels due to imprecision because of the small sample size and the wide confidence intervals, which include considerable benefit and harm.

Background

Description of the condition

Colorectal operations are amongst the most frequently performed surgical procedures worldwide. In addition to emergency surgery (e.g. bowel perforations, diverticulitis, lower gastrointestinal bleeding), colon resections are performed for treating inflammatory diseases (e.g. ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease) and colorectal cancer (Kuhry 2008; Spanjersberg 2011).

The treatment outcome is significantly influenced by the surgical procedure itself along with the occurrence of postoperative complications. Amongst the most serious complications are anastomotic leaks and surgical site infections (SSIs), which can lead to a prolonged and severe clinical course with impaired long‐term outcomes. In oncological cases, prolonged postoperative recovery can lead to a delayed start of adjuvant oncological treatment and thus to an increased risk of metastasis or local recurrence (Beck 2020; Kulu 2015; Nachiappan 2016; Young 2012). The incidence of complications is, amongst other factors, related to the type of surgery performed. Whilst anastomotic leaks are infrequent for small bowel and elective colon resections (1% to 3%), they occur far more frequently after rectal resections (10% to 23%) (ISOS 2016; Kulu 2015; Toh 2018; Walker 2004; Weidenhagen 2007). Compared with other abdominal operations, colorectal resections present an eight‐fold higher risk for the occurrence of adverse events. For instance, the SSI rate in colorectal surgery lies between 9% and 24 %, while in non‐colorectal surgery it is only 2% to 9 % (Anjum 2017; Migaly 2019). One reason for the increased complication rate in colorectal surgery is the high bacterial colonisation by the physiological intestinal flora, the so‐called microbiome.

Overall, there are numerous recommendations to reduce the risk of surgical complications. These range from specified preoperative preparation of the surgical field (e.g. preoperative whole‐body bathing or showering, hair removal, and disinfection methods) to intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis (Ling 2019; Nelson 2014; NICE 2019; WHO 2018). However, there is disagreement about what might be the best strategy for bowel preparation before elective colon and rectal surgery.

Description of the intervention

The underlying idea of preoperative bowel preparation is to clean the bowel from faeces, thereby reducing the bacterial load, which could lead to a lower rate of postoperative complications, especially SSIs and anastomotic leakage. Furthermore, removing the faeces makes it easier to manipulate the bowel in laparoscopic surgeries and lowers the risk of unwanted faecal spillage into the abdominal cavity.

In summary, there are four widespread interventions for bowel preparation before colorectal surgery in everyday clinical practice:

no bowel preparation;

mechanical bowel preparation (MBP);

oral antibiotics (oAB);

combination of oral antibiotics and mechanical bowel preparation (MBP+oAB).

For MBP, osmotically active solutions are mainly used nowadays (Kumar 2013; WHO 2018). By translocating fluid into the intestine, these lead to the development of diarrhoea and as a result the emptying of the bowel. Given the constant development of the applied solutions in the last decade, complications such as dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, or cardiovascular dysfunction rarely occur (Kumar 2013).

Regarding the antibiotic regimen, a combination of active substances that are effective against both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria are used (Migaly 2019; WHO 2018). Numerous different protocols exist regarding the active substance, dosage, and duration of treatment (WHO 2018). Two meta‐analyses from 2018 recommend a combination of an aminoglycoside (kanamycin or neomycin) and metronidazole or erythromycin administered one to three days before surgery (McSorley 2018; Toh 2018).

There is some evidence that luminal faeces may lead to an inactivation of the topically acting antibiotics. Consequently, oAB should be administered after, or at least in combination with MBP (Schardey 2017). However, the evidence for this hypothesis is ambiguous. Recent meta‐analyses failed to demonstrate a significant difference in SSI or anastomotic leak rates after combined or sole oral antibiotic bowel preparation, calling into question the need for combination therapy (Nelson 2020; Rollins 2019).

How the intervention might work

It is well known that the intestinal microbiome is important for myriads of physiological processes such as metabolism of drugs and nutrition degradation, biosynthesis of neurotransmitters and hormones, and influences immune maturation, host cell proliferation, and neurological signalling – to name but a few examples. However, the microbiome also plays an important role in disease development, for example autoimmune and gastrointestinal disease, but also neuropsychiatric illnesses (Lynch 2016). There is growing evidence that the intestinal microbiome is also involved in wound‐healing processes, especially in the healing of bowel anastomosis or the development of an anastomotic leakage (Schardey 2017). In addition to the surgical technique, bacterial colonisation of the intestinal mucosa of the anastomotic region also influences the occurrence of an insufficiency. Due to the surgical trauma and resulting ischaemia, mucosal bacteria such as Enterococcus faecalis or Pseudomonas aeruginosa develop the ability to express collagenases and activate matrix metalloproteinase 9 in the patient's intestinal tissue. This mechanism promotes the degradation of synthesised tissue leading to vulnerability of the newly created anastomosis (Anjum 2017; Schardey 2017; Shogan 2015).

In order to prevent these wound‐healing disturbances, preoperative preparation of the bowel is intended to create a clean working environment by reducing bacterial contamination of the intestine and respectively of the surgical field.

Why it is important to do this review

In several publications, as well as a Cochrane Review published in 2011, the use of MBP compared with no preparation or rectal enemas did not demonstrate an improved outcome for patients, which led to the recommendation to refrain from preoperative bowel preparation (Güenaga 2011).

In contrast, a current large registry study with more than 8000 patients demonstrated a significantly lower rate of postoperative SSIs as well as a shorter length of hospital stay with combined therapy of oAB and MBP compared with no bowel preparation or monotherapy with MBP or oAB (Klinger 2019). In addition, the combination therapy group also had the lowest readmission rate. Based on these data, the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons recommended a combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation prior to elective colon and rectal resections (Migaly 2019).

Despite the evidence for a beneficial effect of supplementing oAB to MBP, a current survey amongst members of the German Society of General and Visceral Surgery revealed that MBP alone is performed in over 50% of colon and over 75% of rectal operations. Additional oAB was only performed in about 10% of these operations (Buia 2019). A comparable survey amongst members of the European Society of Coloproctology revealed similar results (Devane 2017). Whilst the majority of respondents reported to regularly use MBP, less than 10% prescribe oral antibiotic therapy. In the USA, the rate of usage of combination therapies is much higher, although it has decreased over the last few years. In a survey conducted by the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons in 1990, 88% of the participants reported using a combined bowel preparation (Solla 1990). In a more recent survey from 2010, only 36% of the colorectal surgeons still prescribe oral antibiotic therapy (Markell 2010).

The results of these surveys reveal that there is currently no uniform approach. Although there are already several meta‐analyses on this topic, they differ considerably in their conclusions: whilst some meta‐analyses report a benefit of combined oral and intravenous antibiotic therapy, with an unclear effect of concurrent mechanical bowel preparation (Nelson 2020; Rollins 2019), other meta‐analyses have shown superiority of the combination of oral antibiotic prophylaxis and mechanical bowel preparation (Toh 2018). However, these differences are not due to more recent findings, but rather to differences in the literature search, study selection criteria, and data extraction management. In order to establish an evidence‐based therapy, a structured and high‐quality meta‐analysis of the available evidence is necessary to provide optimal guidance on preoperative bowel preparation aiming to reduce the postoperative complication rate as well as overall mortality.

Objectives

The aim of this review is to assess the evidence for the use of combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation for preventing complications in elective colorectal surgery.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all published, unpublished, and ongoing randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi‐RCTs (trials in which randomisation is attempted but potentially predictable, such as allocating participants by day of the week or sequence of entry into trial) comparing preoperative bowel preparation using MBP and oAB prior to elective colon or rectal surgery. We considered all identified studies for inclusion regardless of date, location, or language of publication.

Types of participants

Adult participants (18 years of age and older) undergoing elective colorectal surgery.

There were no exclusion criteria regarding the indication for surgery (both benign and malignant diseases were eligible); the type of colorectal surgery performed ((extended) right/left hemicolectomy, transverse colectomy, sigmoid resection, rectal resections, proctocolectomies or reanastomoses (provided a colorectal anastomosis was performed)); any previous treatment of the patient (e.g. neoadjuvant therapy); patient co‐morbidities; or the timing and location of the surgery.

For studies that include both eligible participants and others (e.g. children), we extracted data only from the eligible participants. We requested this information from the study authors if necessary. For one study, it was not possible to extract eligible data separately, and we could not obtain further information from the study author, so this study was classified as awaiting classification.

Types of interventions

We included any combination therapy of preoperative oAB and MBP.

We anticipated that there were different protocols in terms of the timing, duration, and frequency of administration, as well as the dosage of substances used (both in terms of antibiotics and mechanical bowel preparation). Any type of preoperative oral antibiotic prophylaxis, as well as any method of mechanical bowel cleansing, was eligible regardless of the mode of delivery, dose, duration, intensity, and co‐interventions. However, combination therapy and parenteral antibiotic prophylaxis (in both the control and intervention group) was mandatory. Regarding the effect of MBP or oAB alone, analyses already exist in further Cochrane Reviews (Güenaga 2011; Nelson 2014). We included studies using standard of care regarding parenteral antibiotic prophylaxis in both participant groups (intervention and control).

We included the following comparisons:

combination of MBP and oAB versus MBP alone;

combination of MBP and oAB versus oAB alone;

combination of MBP and oAB versus no preoperative preparation or placebo control (nBP).

Types of outcome measures

We analysed the occurrence of the predefined primary and secondary outcome parameters listed below within 30 days postoperatively. We assessed only the incidence of complications, and not the time of their occurrence. The outcome parameters listed below can be differentiated into efficacy and safety outcomes, whereby all listed outcome parameters, with the exception of length of hospital stay, refer to patient safety.

Reporting one or more of the listed outcomes was not a study inclusion criterion of the review.

Primary outcomes

If an outcome occurred in a participant at multiple sites (e.g. wound infection) or at different time points during the 30‐day postoperative observation interval, we counted such an outcome measure only once.

We considered the following primary outcomes.

Number of participants with SSIs (infection of the incision site involving the skin and subcutaneous tissue (superficial), deep soft tissue (deep), or a part of the body deeper than the fascia/muscle layers that was opened or manipulated during the surgical procedure (organ/space) and occurs within 30 days after the surgical procedure);

Number of participants with anastomotic leakage.

For the above outcome parameters, an absolute risk reduction (RRR) of 5 % was considered clinically relevant. From this RRR value, a risk ratio (RR) of 0.95 can be derived. This means that the RR and the 95% confidence interval (CI) for SSI and anastomotic leakages should be equal to or smaller than 0.95 to be considered a clinically relevant difference.

Secondary outcomes

We recorded the number of participants with the following adverse events (as defined by the primary study author) within 30 days postoperatively.

Mortality.

Mild postoperative complications (Clavien‐Dindo grade I and II).

Severe postoperative complications (Clavien‐Dindo grade III and IV).

Incidence of postoperative ileus.

Length of hospital stay (LOS) [days].

-

Side effect of intervention:

incidence of adverse effects of MBP such as dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, renal failure, or cardiac dysfunction (as defined by the primary study author);

incidence of adverse effects of oAB such as diarrhoea or pseudomembranous enterocolitis (as defined by the primary study author);

number of participants for whom the intervention was discontinued due to side effects, as well as the number of participants for whom therapy was initiated to treat the complications.

C. difficile‐related diarrhoea

Our prespecified outcome measures were not independent of each other. For example, people with SSIs, anastomotic leakages, or other adverse events were additionally classified according to the severity of the complications that occurred using the Clavien‐Dindo classification (Clavien 2009).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases from inception to December 15, 2021:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL via the Cochrane Library; 1998 to 2021);

MEDLINE (via PubMed; 1946 to 2021);

Embase (via Ovid; 1988 to 2021).

The search strategies are given in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We also searched the trial registries ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov, see Appendix 1) and the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) search portal (trialsearch.who.in, see Appendix 1). Furthermore, we screened the reference lists of all included publications and the included studies of related meta‐analyses for additional studies. We contacted organisations (e.g. regional colorectal surgery societies) to ask if they have knowledge of ongoing or completed studies to complement our database searches. We sought both published and unpublished trials. We did not limit the search by language or date.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (MW and TV) screened the title and abstract of each study identified in the electronic search for potential relevance. Each review author independently decided on trial inclusion using the following predetermined eligibility criteria.

Study design: RCT or quasi‐RCT.

Population: adults undergoing elective colorectal surgery.

Intervention: preoperative bowel preparation using oAB and MBP.

Comparison: no preoperative bowel preparation (nBP) or sole treatment with either MBP or oAB.

Any disagreements regarding study eligibility during title and abstract screening were resolved by a third review author or by contacting the study authors for clarification.

Afterwards, two review authors (MW and TV) independently carried out the full‐text screening using the same inclusion criteria.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (MW and SS) independently abstracted the following information from the included studies using a standardised form. The data extraction form was previously piloted on two studies and adjusted where necessary.

-

General information

Study ID, study title, corresponding author and contact details, publication date, country where the study was conducted, duration of trial and duration of follow‐up, aim of study (short description), inclusion and exclusion criteria, baseline imbalances, any conflicts of interest stated by the investigators, source of funding, ethics approval, trial registration, and sample size calculation.

-

Number of participants

Number randomised, number analysed, number of participants in the intervention/control group.

-

Population

Age, sex, co‐morbidities, surgery indication, type of operation, subgroups reported, and subgroups measured.

-

Intervention

Description of the intervention, agent and dose used for MBP, agent and dose used for oAB, timing of preparation (MBP), timing of preparation (oAB), modification of intervention, and concomitant medications.

-

Control

Description of control, agent and dose used, and timing of preparation.

-

Outcomes

Incidence of SSI, incidence of incisional (superficial or deep) and organ/space SSI, incidence of anastomotic leakage, spectrum of organisms detected, postoperative complications subdivided according to Clavien‐Dindo in mild (I/II) and severe (III/IV) complications as reported by the authors, incidence of postoperative ileus according to the definition of the primary study author, LOS (days), mortality, and side effects of the intervention (e.g. electrolyte imbalances, renal failure, incidence of Clostridium difficile infection, or termination of the intervention due to side effects).

Outcomes reported in trial but not used in review.

In cases where the majority of the required data was not reported in an identified publication, we searched for the associated study report or attempted to obtain the required data through correspondence with the study author. Trials whose results were published in more than one publication were included as one study. Data extraction was based on the main primary publication, but secondary publications were also considered for additional information. All publications are listed in the references of included studies.

Any disagreements were resolved by discussion or by consultation with a third review author if required.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risk of bias in the included studies using Cochrane's RoB 2 tool (Sterne 2019; Higgins 2021). Two review authors (MW and SS) independently assessed the risk of bias of the results, with any disagreements resolved through discussion with a third review author.

We were interested in the effect of allocation at baseline, regardless of whether the intervention was delivered as intended (i.e. the 'intention‐to‐treat' effect). Consistent with the RoB 2 tool (Sterne 2019; Higgins 2021), we considered the following five domains in our assessment:

risk of bias arising from the randomisation process;

risk of bias due to deviations from the intended interventions (effect of assignment as well as adhering to intervention);

missing outcome data;

risk of bias in measurement of the outcome;

risk of bias in selection of the reported result.

We assessed the risk of bias for the following five outcomes that also contribute to the summary of findings tables of the review, measured at a time point closest to the 30‐day postoperative window (see 'Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence' section below):

SSIs;

anastomotic leakage;

mortality;

incidence of postoperative ileus;

LOS.

We assessed these domains using the 'Excel tool to implement RoB 2' (available at www.riskofbias.info/welcome/rob-2-0-tool/current-version-of-rob-2), and followed the recommended algorithm of signalling questions and response options to reach one of the following risk of bias judgements for each of the five domains, and consequently for each of our prespecified outcome measures:

low risk;

some concerns;

high risk.

To assess the overall risk of bias of an outcome, we considered judgements of the five individual domains. To be judged as 'low risk', all domains had to be rated as at low risk of bias. We assessed an outcome as 'some concerns' if risk of bias had been rated as some concerns in at least one domain, and high risk of bias in no domains. We assessed an outcome as 'high risk' if high risk of bias was identified in even one domain. We also classified an outcome as 'high risk' if we judged several domains as 'some concerns', as we consider confidence in such an outcome to be considerably reduced (Higgins 2021).

Measures of treatment effect

For continuous outcomes (e.g. LOS), we extracted the final mean value and standard deviation (SD) of each outcome of interest as well as the number of participants evaluated at the final assessment in each treatment arm. With these data, we calculated the mean difference (MD) and the 95% CI and, if appropriate, a pooled estimate of treatment effects. In cases were MDs and SDs were reported by the primary study authors, those data were used.

For dichotomous outcomes (SSIs, anastomotic leakage, mortality, postoperative complications, incidence of postoperative ileus, treatment‐related adverse effects), we extracted the RR including the 95% CI. If the RR was not reported, the number of affected participants were extracted to estimate an RR and its 95% CI.

Unit of analysis issues

We expected neither cross‐over studies nor cluster‐randomised studies in this clinical area, therefore the protocol did not specify how such studies should have been handled if we had identified one.

Our review includes one intervention group (MBP+oAB) and three comparison groups (comparison 1: MBP alone; comparison 2: oAB alone; comparison 3: no preoperative bowel preparation (nBP)). As there were no restrictions on the methodology of the intervention, no further subdivision of the intervention or comparison groups was intended.

We identified one study with two intervention groups (Espin‐Basany 2005), which we combined for statistical analysis in order to assign it to our predefined intervention group.

Dealing with missing data

For relevant data missing from a trial report, we attempted to contact the corresponding author to obtain the missing information. We did not impute missing information.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Clinical heterogeneity may be caused by several factors, such as patient age and co‐morbidities, indication, and treatment prior to surgery, as well as the procedures used to decontaminate the bowel. In addition, different surgical procedures, as well as the type of access route (minimally invasive versus open surgery), also contribute to heterogeneity. Methodological heterogeneity may be caused by the different risks of bias between studies. To assess the impact of clinical and methodological heterogeneity, we performed subgroup and sensitivity analyses on these topics. We identified statistical heterogeneity through visualisation of the forest plots as well as the Chi² test. We used the I² statistic for the quantification of heterogeneity.

We interpreted the I² value as follows (Deeks 2021).

< 30% to 40%: little or no heterogeneity.

41% to 74%: moderate heterogeneity.

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

Possible reasons for considerable heterogeneity were investigated and reported.

Assessment of reporting biases

To assess whether selective reporting of outcomes might affect the review findings, we matched the study protocols or registry entries, if available, with the published information on outcomes.

As we identified more than 10 studies reporting on our primary outcomes for the comparison MBP+oAB versus MBP, we created a funnel plots to assess the potential for small‐study effects where possible.

Data synthesis

Before conducting the meta‐analysis, we checked whether the participants, interventions, comparisons, and outcomes were sufficiently similar to ensure that the result of the analysis were clinically meaningful.

To calculate an overall treatment effect, we combined the data using a random‐effects model. As different agents of MBP and a variety of oAB with different administration intervals and combination options were included, a variance between the included trials has been assumed.

We included all eligible studies in the meta‐analysis regardless of their risk of bias rating. We performed the statistical analysis with Review Manager 5 software (Review Manager 2020) and RevMan Web (RevMan Web 2020). To combine dichotomous outcome data, we used the method proposed by Mantel‐Haenszel (Deeks 2021). If meta‐analysis was not appropriate due to an insufficient number of eligible studies or substantial heterogeneity between studies, we provided a narrative description of study characteristics and results.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Provided that sufficient studies were identified to justify subgroup analyses or meta‐regressions (at least 10 studies per outcome), we investigated the possible causes of heterogeneity by means of subgroup analyses for the primary outcome parameters.

We conducted subgroup analyses for the first comparison (MBP+oAB versus MBP) with regard to the outcome SSI for the following aspects:

surgery indication;

type of surgery;

surgical approach;

duration of mechanical bowel preparation;

agent combination of oral antibiotics;

duration of intravenous prophylaxis.

We assessed differences between subgroups by performing a test for heterogeneity across subgroups (i.e. Cochran's Q) and analysing I².

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted sensitivity analysis to examine the robustness of our findings, investigating the influence of studies judged at 'some concerns' on the effect size by removing these studies for each outcome and re‐analysing the remaining studies to see if the results were influenced by these factors.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We created summary of findings tables using GRADEpro GDT software (GRADEpro GDT) for each comparison (MBP+oAB versus MBP/oAB/nBP) for the following outcomes, as measured during the 30‐day postoperative duration (Schünemann 2021):

SSIs;

anastomotic leakage;

mortality;

incidence of postoperative ileus;

LOS.

Two review authors independently assessed the certainty of the evidence based on the five GRADE domains (overall RoB 2 judgement, imprecision, inconsistency, indirectness, and publication bias) (Schünemann 2013). Any disagreements were resolved through discussion or by involving a third review author. The GRADE assessment resulted in one of four degrees of certainty (high, moderate, low, or very low certainty), expressing our confidence in the estimate of impact.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies, Characteristics of studies awaiting classification and Characteristics of ongoing studies tables.

We contacted the authors of six studies included in the full‐text screening and asked for more information to better assess whether these studies could be included in our review (Abis 2019; Arezzo 2021; Ikeda 2016; Mulder 2020; Tagliaferri 2020; Uchino 2019). Based on this additional information we received, we included Arezzo 2021; Ikeda 2016 and Uchino 2019 in our review and excluded Mulder 2020. As Abis 2019 includes both eligible and ineligible patients which can not be separated based on the published version of the study, we classified this study as awaiting classification. Tagliaferri 2020 was classified as an ongoing study as only an abstract with primary results was found and no published report of the final study results.

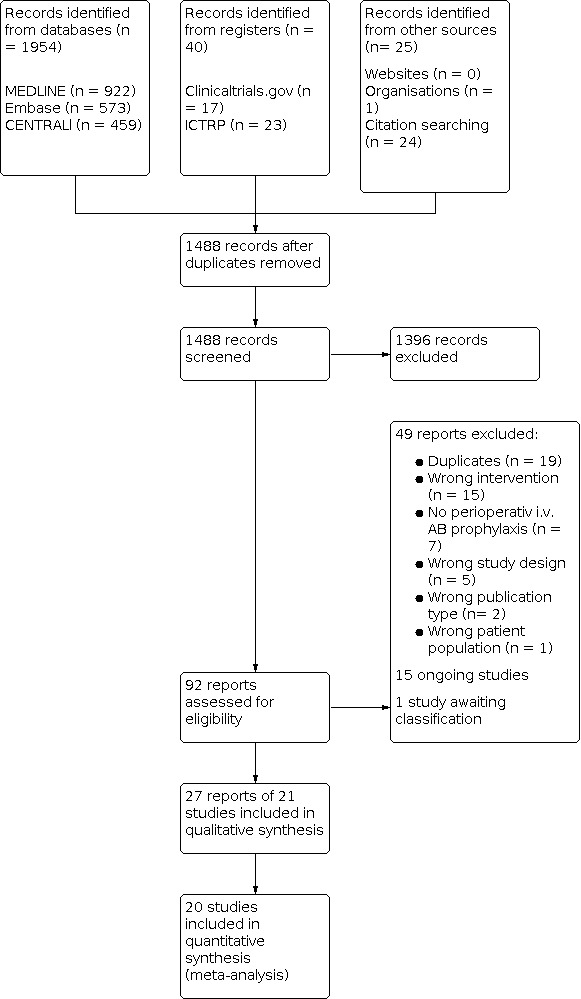

Results of the search

The process of our literature search is shown in a PRISMA flowchart in Figure 1. We identified 1954 records through the electronic searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (459 records), MEDLINE (922 records) and Embase (573 records). Additionally, 40 records were identified by searching trial registries (clinicaltrials.gov: 17 records; ICTRP: 23 records). Further, 25 records were identified by contacting colorectal surgical societies, screening reference lists and reviewing included studies in related meta‐analyses. Of the 1488 records after removing 531 duplicates, we excluded 1396 clearly irrelevant records by screening their titles and abstracts. We retrieved the full text of 92 records for further assessment. We excluded 30 studies for the reasons listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

1.

Figure 1: PRISMA flowchart

We also identified 15 ongoing studies (see Characteristics of ongoing studies), and found one study investigating the effect of selective bowel decontamination with oral antibiotics(OABs) and oral antimycotics (Abis 2019). Mechanical bowel preparation (MBP) was performed only in left‐sided colon, sigmoid and low‐anterior resections. To determine if any of the study participants might be eligible for our review, the authors were asked to provide primary data of the study. As we have not received a response yet, the study was rated as awaiting classification (see Studies awaiting classification).

Included studies

We included 21 studies. Seventeen studies compared MBP+oAB with sole MBP (Anjum 2017; Arezzo 2021; Espin‐Basany 2005; Hata 2016; Horie 2007; Ikeda 2016; Ishida 2001; Kobayashi 2007; Lau 1988; Lazorthes 1982; Lewis 2002; Oshima 2013; Papp 2021; Rybakov 2021; Sadahiro 2014; Takesue 2000; Uchino 2019). In three studies, MBP+oAB was compared with oAB alone (Ram 2005; Suzuki 2020; Zmora 2003). Only one study compared MBP+oAB with nBP (Koskenvuo 2019).

Participants

In total, 5968 patients were randomised and 5264 participants analysed in the 21 included studies. Whereby only a subgroup of participants from four studies (Arezzo 2021; Ikeda 2016;Lazorthes 1982; Uchino 2019) were eligible for our meta‐analysis and the corresponding primary data were provided by the authors if necessary. All study participants underwent elective colorectal surgery.

While most studies had a mixed indication profile, 10 studies only included patients who had surgery for colorectal cancer (Arezzo 2021; Hata 2016; Horie 2007; Ikeda 2016; Kobayashi 2007; Lau 1988; Rybakov 2021; Sadahiro 2014; Suzuki 2020; Takesue 2000). Two other studies were limited to resections for inflammatory bowel disease (Oshima 2013: ulcerative colitis; Uchino 2019: Crohn's disease). Regarding the surgical approach, 10 studies included both open and minimally invasive procedures. Seven studies included only open surgery (Horie 2007; Lau 1988; Lazorthes 1982; Oshima 2013; Ram 2005; Takesue 2000; Uchino 2019), and four included only minimally invasive surgery (Arezzo 2021; Hata 2016; Ikeda 2016; Koskenvuo 2019).

Interventions

In 16 studies, MBP was performed on the day before surgery (Anjum 2017; Espin‐Basany 2005; Hata 2016; Horie 2007; Ikeda 2016; Ishida 2001; Kobayashi 2007; Koskenvuo 2019; Lewis 2002; Oshima 2013; Papp 2021; Ram 2005; Rybakov 2021; Takesue 2000; Uchino 2019; Zmora 2003). However, two studies each reported on a two‐day or three‐day laxative programme (Lau 1988; Lazorthes 1982; Sadahiro 2014; Suzuki 2020). The substance most commonly used for MBP was polyethylene glycol (PEG) in 10 studies (Arezzo 2021; Horie 2007; Ishida 2001; Kobayashi 2007; Koskenvuo 2019; Rybakov 2021; Sadahiro 2014; Suzuki 2020; Takesue 2000; Zmora 2003). The second most commonly used substance in nine studies was sodium picosulphate (Anjum 2017; Espin‐Basany 2005; Hata 2016; Ikeda 2016; Lewis 2002; Ram 2005; Sadahiro 2014; Suzuki 2020; Uchino 2019), and the third most commonly used were magnesium preparations in six studies (Hata 2016; Ikeda 2016; Lau 1988; Lazorthes 1982; Oshima 2013; Uchino 2019). A total of eight studies used a combination of several agents fo rMBP, while 13 studies used monotherapy (mostly with PEG solutions). The additional use of enemas was reported in four studies (Lau 1988; Lazorthes 1982; Papp 2021; Zmora 2003).

Regarding oral antibiotic therapy, there were multiple combinations of different substances and doses. In almost all studies, a combination of two active substances was used (exception: Horie 2007: monotherapy with kanamycin; Ram 2005: no information on agent, dosage and time of intake). The most common agents used were metronidazole in 14 studies (Anjum 2017; Espin‐Basany 2005; Hata 2016; Ikeda 2016; Koskenvuo 2019; Lazorthes 1982; Lewis 2002; Oshima 2013; Papp 2021; Rybakov 2021; Sadahiro 2014; Suzuki 2020; Takesue 2000; Uchino 2019), followed by kanamycin in 11 studies (Hata 2016; Horie 2007; Ikeda 2016; Ishida 2001; Kobayashi 2007; Lazorthes 1982; Oshima 2013; Sadahiro 2014; Suzuki 2020; Takesue 2000; Uchino 2019). The combination of these two agents was also the combination therapy most frequently used. Other agents used were neomycin in seven studies (Arezzo 2021; Espin‐Basany 2005; Koskenvuo 2019; Lau 1988; Lewis 2002; Papp 2021; Zmora 2003), erythromycin in five studies (Ishida 2001; Kobayashi 2007; Lau 1988; Rybakov 2021; Zmora 2003) ,and levofloxacin and bacitracin in one study each (Anjum 2017, respectively Arezzo 2021). As for dosage, metronidazole and kanamycin were mostly prescribed at a daily dose of 1500 mg each (in eight and six studies, respectively). However, the daily dose of metronidazole varied between 750 mg and 4000 mg in the included studies. Such differences in daily antibiotic dosage were observed throughout the studies. In terms of timing of administration, in 15 studies oAB was administered after the mechanical preparation of the bowel in two or three single doses on the day before surgery (Anjum 2017; Arezzo 2021; Hata 2016; Ikeda 2016; Kobayashi 2007; Koskenvuo 2019; Lau 1988; Lewis 2002; Oshima 2013; Papp 2021; Rybakov 2021; Sadahiro 2014; Suzuki 2020; Takesue 2000; Uchino 2019). Three studies report a two‐ or three‐day oral antibiotic preparation (Horie 2007; Ishida 2001; Lazorthes 1982). In addition, one three‐armed study compared a three‐day and a one‐day oAB‐regimen in addition to MBP with MBP alone (Espin‐Basany 2005). More detailed information on the agent, dosages used and time of intake for the individual studies can be found in the Characteristics of included studies tables.

Outcomes

Regarding the primary outcomes, all but one of the included studies reported the number of participants with surgical site infections (SSIs) (Lazorthes 1982 subdivided wound infections into major and minor, but only data from major wound infections were reported). Twelve studies also reported a subdivision into incisional and organ/space SSIs. Information on the number of participants with anastomotic leakage was reported in 13 studies. All predefined secondary outcomes were reported in individual included studies. Table 4 provides an overview of which study reported on which outcome.

1. Summary of outcomes reported per study.

| StudyID | SSI | Subdivision in incisional and organ/space SSI | Anastomotic leakage | Mortality | Mild and severe postoperative complications according to Clavien‐Dindo | Incidence of postoperative ileus | LOS | Side effect of Intervention | C. difficile‐related diarrhoea |

| MBP+oAB vs. MBP | |||||||||

| Anjum 2017 | yes | yes | no | no | no | no | no | no | no |

| Arezzo 2021 | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Espin‐Basany 2005 | yes | no | no | no | no | yes | no | yes | no |

| Hata 2016 | yes | yes | yes | no | no | yes | no | no | yes |

| Horie 2007 | yes | no | yes | no | no | no | no | no | no |

| Ikeda 2016 | yes | yes | yes | no | no | yes | yes | no | yes |

| Ishida 2001 | yes | yes | yes | no | no | no | no | no | no |

| Kobayashi 2007 | yes | yes | no | no | no | no | no | no | no |

| Lau 1988 | yes | no | yes | no | no | no | yes | no | no |

| Lazorthes 1982 | incorrect* | no | no | yes | no | no | incorrect** | no | no |

| Lewis 2002 | yes | no | no | no | no | no | no | no | no |

| Oshima 2013 | yes | yes | no | no | no | no | no | yes | no |

| Papp 2021 | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | no | yes |

| Rybakov 2021 | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | no | no | incorrect*** |

| Sadahiro 2014 | yes | yes | yes | no | no | no | no | no | incorrect**** |

| Takesue 2000 | yes | no | yes | no | no | no | no | no | no |

| Uchino 2019 | yes | yes | no | no | no | no | no | no | no |

| MBP+oAB vs. oAB | |||||||||

| Ram 2005 | yes | no | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | no | no |

| Suzuki 2020 | yes | yes | yes | no | no | no | no | no | yes |

| Zmora 2003 | yes | no | yes | yes | no | yes | incorrect** | no | no |

| MBP+oAB vs. nBP | |||||||||

| Koskenvuo 2019 | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

* Wound infections were classified into major and minor, but only data from major wound infections are reported **Only the numerical value given with no unit of measurement specified, no information about range or standard deviation *** Detection of Clostridia in general, not specific for C. difficile **** Detection rate of C. difficile toxin pre‐ and postoperatively, regardless of whether diarrhoea was present

Regarding the side effects of the intervention, only four of the 21 included studies reported the occurrence of adverse events related to preoperative bowel preparation (Arezzo 2021; Espin‐Basany 2005; Oshima 2013; Papp 2021). The reported side effects included nausea/vomiting or abdominal pain, but none of the included studies reported adverse effects of MBP such as dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, renal failure or cardiac dysfunction. The number of participants who discontinued the intervention due to side effects was also not reported in any study.

Excluded studies

A total of 30 of the identified studies were excluded. Fifteen because they investigated the wrong intervention, seven due to the lack of perioperative intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis, and five for an inappropriate study design. Two other articles were excluded because of the wrong publication type (congress poster and invited commentary, respectively), and one study was excluded for an inappropriate patient population (patients with anastomotic leakages were excluded from the analysis); see Characteristics of excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias assessments, including all domain evaluations and support for the assessment, are reported in the Risk of bias (tables) section and displayed along the forest plots of each analysis.

None of the included studies was assessed to be of high risk of bias. However, two‐thirds of the studies raised some concerns about the risk of bias. In most cases, these concerns were due to the lack of a predefined analysis plan or the lack of information about the randomisation process.

Detailed data on the risk of bias assessment, such as the Excel file with the consensus responses to the signalling questions, are available on request.

Surgical site infections (SSIs) Twelve of the 20 studies that reported this outcome raised some concerns about the risk of bias (Anjum 2017; Espin‐Basany 2005; Horie 2007; Ishida 2001; Kobayashi 2007; Lau 1988; Lewis 2002; Oshima 2013; Ram 2005; Suzuki 2020; Takesue 2000; Zmora 2003). The concerns were due to the lack of a predefined analysis plan, and in three of these studies, additional inadequate information about the randomisation process (Espin‐Basany 2005; Oshima 2013; Takesue 2000).

Anastomotic leakage Eight of the 14 studies reporting this outcome were at low risk of bias (Arezzo 2021; Hata 2016; Ikeda 2016; Koskenvuo 2019; Papp 2021; Rybakov 2021; Sadahiro 2014; Zmora 2003), six were considered to have some concerns about the risk of bias because no predefined analysis plan could be identified for these studies (Horie 2007; Ishida 2001; Lau 1988; Ram 2005; Suzuki 2020; Takesue 2000). One of the studies also inadequately described the randomisation process, which also raises concerns about risk of bias (Takesue 2000).

Mortality Half of the six studies had a low risk of bias (Arezzo 2021; Koskenvuo 2019; Papp 2021). The other three studies were rated as having some concerns regarding the selection of the reported outcomes of the individual studies (Lazorthes 1982; Ram 2005; Zmora 2003); additionally, in one of the three studies, the randomisation process was not adequately described, leading to some concerns regarding the risk of bias (Lazorthes 1982).

Incidence of postoperative ileus. Only three of the nine studies reporting this outcome raised some concerns about the risk of bias (Espin‐Basany 2005; Ram 2005; Zmora 2003). Again, these concerns were due to the lack of a predefined analysis plan and additional an unclear randomisation method in one case (Espin‐Basany 2005).

Length of hospital stay Only one of the four studies reporting this outcome raised some concerns about the risk of bias (Lau 1988). The reason for this is again the lack of a predefined analysis plan.

Assessment of publication bias The assessment of a small study effect using funnel plots was only possible for the comparison MBP+oAB versus MBP for the outcomes SSI and anastomotic leakage, as no other comparison included ten or more studies. The funnel plots show a nearly symmetrical distribution, indicating that there was no evidence of publication bias (Figure 2; Figure 3). In the funnel plot for the outcome SSI (Figure 2), one study stands out with a much smaller patient population that does not fit the otherwise symmetrical distribution. This study is Arezzo 2021, of which only a subpopulation was included, which explains the smaller sample size resulting in an outlier from symmetry in the funnel plot.

2.

Comparison 1 (MBP+oAB vs. MBP): Funnel plot regarding the incidence of SSI

3.

Comparison 1 (MBP+oAB vs. MBP): Funnel plot regarding the incidence of anastomotic leakage

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

See: Table 1 for combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation versus mechanical bowel preparation alone, Table 2 for combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation versus oral antibiotics alone and Table 3 for combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation versus no bowel preparation.

Comparison 1: Combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation versus mechanical bowel preparation alone (MBP+oAB versus MBP)

We identified 17 relevant studies for this comparison (Anjum 2017; Arezzo 2021; Espin‐Basany 2005; Hata 2016; Horie 2007; Ikeda 2016; Ishida 2001; Kobayashi 2007; Lau 1988; Lazorthes 1982; Lewis 2002; Oshima 2013; Papp 2021; Rybakov 2021; Sadahiro 2014; Takesue 2000; Uchino 2019). As only a subpopulation of participants from Arezzo 2021, Ikeda 2016 and Uchino 2019 were eligible for our meta‐analysis, primary data from these studies were requested and received, ensuring that only eligible patients were included in our analysis.

All pre‐defined outcomes were addressed in at least three studies, so that meta‐analyses could be calculated for all outcomes.

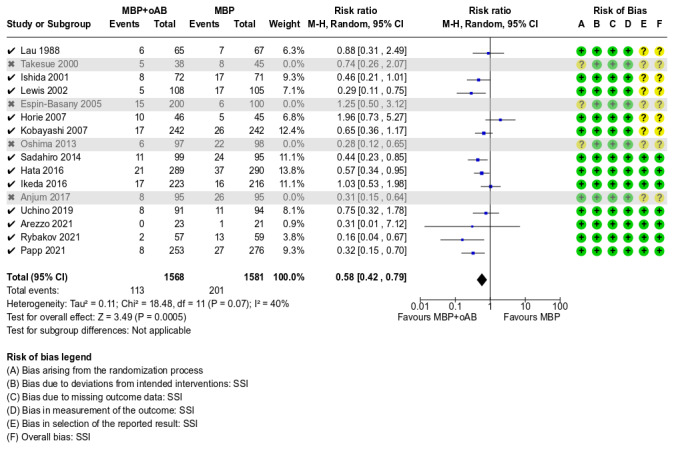

Surgical site infections (SSIs)

A total of 3917 participants from 16 studies were included for this outcome and in corresponding meta‐analysis. The results suggested that the intervention (MBP+oAB) reduced the risk of SSI from 137 per 1000 with MBP alone to 77 per 1000 (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.74; P < 0.0001, I² = 44%; Analysis 1.1). This risk reduction is clinically relevant, as we defined an RR and 95% CI of 0.95 or less as a minimally important difference (MID).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: MBP+oAB vs. MBP, Outcome 1: SSI

The overall certainty of evidence was moderate, downgraded one level for inconsistency due to moderate heterogeneity amongst these studies (Chi² = 27.01, df = 15 (P = 0.03); I² = 44%). The subgroup analyses performed regarding the indication for surgery (Analysis 1.13), the type of surgery performed (Analysis 1.14) or the surgical approach (Analysis 1.15) as well as concerning the duration of mechanical bowel preparation (Analysis 1.16) or the substances used for oral antibiotic bowel preparation (Analysis 1.17) and with regard to the duration of intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis (Analysis 1.18) could not explain the heterogeneity.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1: MBP+oAB vs. MBP, Outcome 13: SSI_Subgroup analysis regarding surgery indication

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1: MBP+oAB vs. MBP, Outcome 14: SSI_Subgroup analysis regarding the type of surgery

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1: MBP+oAB vs. MBP, Outcome 15: SSI_Subgroup analysis regarding the surgical approach

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1: MBP+oAB vs. MBP, Outcome 16: SSI_Subgroup analysis regarding the duration of mechanical bowel preparation

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1: MBP+oAB vs. MBP, Outcome 17: SSI_Subgroup analysis regarding the agent combination of oral antibiotics

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1: MBP+oAB vs. MBP, Outcome 18: SSI_Subgroup analysis regarding the duration of intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis

Regarding incisional and organ/space SSIs MBP+oAB also reduced the risk compared with MBP alone (incisional: RR 0.47, 95% CI 0.33 to 0.66; P < 0.0001, I² = 37%; 10 studies, 3054 patients; Analysis 1.2; organ/space: RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.44 to 0.98; P = 0.04, I² = 0%; 10 studies, 3054 patients; Analysis 1.3).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: MBP+oAB vs. MBP, Outcome 2: Incisional SSI

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: MBP+oAB vs. MBP, Outcome 3: Organ/space SSI

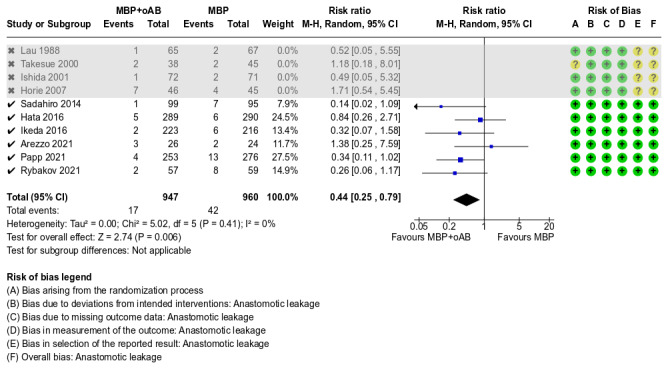

Anastomotic leakage

A total of 2356 participants from 10 studies were included for this outcome and the respective meta‐analysis. The results indicated that the risk of anastomotic leakage could be reduced from 44 per 1000 patients receiving MBP alone to 26 per 1000 patients when MBP+oAB was used (RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.99; P = 0.05, I² = 9%; Analysis 1.4). Whether the risk reduction that can be achieved by MBP+oAB is clinically relevant cannot be ascertained, as the upper limit of the 95% CI slightly exceeds our MID of 0.95. The overall certainty of the evidence was moderate, downgraded by one level due to the limited number of events in the included studies and a rather wide confidence interval, suggesting imprecision of the results.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: MBP+oAB vs. MBP, Outcome 4: Anastomotic leakage

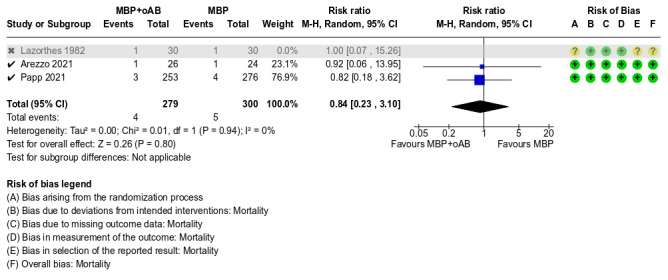

Mortality

A total of 639 participants from 3 studies were included in this meta‐analysis. The results suggested that there was no difference in mortality between MBP+oAB and MBP alone (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.27 to 2.82; P = 0.81, I² = 0%; Analysis 1.5). The overall certainty of the evidence was moderate, downgraded by one level due to the limited number of events in the included studies and wide confidence intervals including both, benefit and harm, suggesting imprecision of the results.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: MBP+oAB vs. MBP, Outcome 5: Mortality

Postoperative complications subdivided according to Clavien‐Dindo in mild (I/II) and severe (III/IV) complications

A total of 695 participants from 3 studies were included in this meta‐analysis. The risk of mild or severe postoperative complications did not differ between MBP+oAB and MBP alone (mild complications: RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.29 to 2.00; P = 0.58, I² = 65%; Analysis 1.6. Severe complications RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.70; P = 0.99, I² = 0%; Analysis 1.7).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: MBP+oAB vs. MBP, Outcome 6: Mild postoperative complications according to Clavien‐Dindo(I + II)

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1: MBP+oAB vs. MBP, Outcome 7: Severe postoperative complications according to Clavien‐Dindo (III + IV)

Incidence of postoperative ileus

A total of 2013 participants from 6 studies were included in this meta‐analysis. The results indicated that the incidence of postoperative ileus was similar between the MBP+oAB and MBP alone groups (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.32; P = 0.56, I² = 0%; Analysis 1.8). The overall certainty of the evidence was low, downgraded one level due to suspected publication bias as small studies report a statistically significant benefit while larger studies show a much smaller effect, and downgraded another level due to imprecision because of the limited number of events in the included studies with wide confidence intervals that included both benefits and harms.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1: MBP+oAB vs. MBP, Outcome 8: Incidence of postoperative ileus

Length of hospital stay (LOS)

A total of 621 participants from 3 studies were included in this meta‐analysis. LOS seemed to be similar between the MBP+oAB and MBP alone groups as the mean discharge time for patients in the intervention group was only 4.6 hours earlier than for patients in the control group (MD ‐0.19, 95% CI ‐1.81 to 1.44; P = 0.82, I² = 0%; Analysis 1.9). The overall certainty of the evidence was moderate, downgraded by one level due to a small sample size and rather wide confidence intervals, suggesting some imprecision of the effect estimate.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1: MBP+oAB vs. MBP, Outcome 9: Length of hospital stay

Side effect of intervention

A total of 545 participants from 3 studies were included for this outcome. The pooled effect estimate implied that side effects of the intervention, both nausea/vomiting and abdominal pain, occurred more frequently in the MBP+oAB group than in the MBP group (nausea/vomiting: RR 2.22, 95% CI 1.33 to 3.72; P = 0.002, I² = 0%; Analysis 1.10). Abdominal pain: RR 1.79, 95% CI 0.67 to 4.82; P = 0.25, I² = 0%; Analysis 1.11).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1: MBP+oAB vs. MBP, Outcome 10: Side effects of Intervention ‐ Nausea/Vometing

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1: MBP+oAB vs. MBP, Outcome 11: Side effects of Intervention ‐ Abdominal pain

C. difficile‐related diarrhoea

Four studies reported on this outcome, but only three were included in the pooled effect estimate. In Arezzo 2021 no patient in this study had C. difficile‐related diarrhoea (n = 50). The results indicated that with regard to the occurrence of C. difficile‐related diarrhoea, there seemed to be no difference between the MBP+oAB and MBP groups (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.24 to 3.34; P = 0.86, I² = 9%; 3 studies, 1547 patients; Analysis 1.12).

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1: MBP+oAB vs. MBP, Outcome 12: C. difficile‐related diarrhoea

Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis including only studies with a low risk of bias revealed that the studies labelled as "some concern" did not have a considerable impact on the overall effect with regard to SSI, mortality, incidence of postoperative ileus and LOS. For the risk of anastomotic leakage on the other hand, excluding the studies with some concern resulted in a stronger effect (RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.95 instead of RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.99; see Appendix 2).

Comparison 2: Combined mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation versus oral antibiotics alone (MBP+oAB versus oAB)

We identified 3 studies for this comparison (Ram 2005; Suzuki 2020; Zmora 2003). The predefined outcomes SSI, anastomotic leakage, mortality and incidence of postoperative ileus were each reported in more than one study so that the data could be pooled in a meta‐analysis.

Surgical site infections (SSIs)

A total of 960 participants from 3 studies were included in the meta‐analysis for this outcome. The results indicated that there was no difference in the risk of postoperative SSI between the MBP+oAB and the oAB alone group (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.34 to 2.21; P = 0.76, I² = 69%; Analysis 2.1). The overall certainty of the evidence was very low and was downgraded by three levels in total due to some concerns about the risk of bias, moderate heterogeneity between included studies suggesting inconsistency of results (Chi² = 6.41, df = 2 (P = 0.04); I² = 69%), and a small sample size with wide confidence intervals, indicating imprecision.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: MBP+oAB vs. oAB, Outcome 1: SSI

Anastomotic leakage

A total of 960 participants from 3 studies were included in this meta‐analysis. The result implicated that the incidence of anastomotic leakage was equal in the MBP+oAB and oAB alone groups (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.21 to 3.45; P = 0.81, I² = 39%; Analysis 2.2). The overall certainty of the evidence was low, downgraded by two levels due to some concerns the risk of bias in the included studies and a small sample size, limited number of events, and wide confidence intervals, indicating imprecision.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2: MBP+oAB vs. oAB, Outcome 2: Anastomotic leakage

Mortality

A total of 709 participants from 2 studies were included in this meta‐analysis. The results indicated that mortality was equal in the MBP+oAB and oAB alone group (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.30 to 3.50; P = 0.97, I² = 0%; Analysis 2.3). The overall certainty of the evidence was low, downgraded by two levels due to some concerns about the risk of bias in the included studies and a small sample size, limited number of events, and wide confidence intervals, indicating imprecision.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2: MBP+oAB vs. oAB, Outcome 3: Mortality

Postoperative complications subdivided according to Clavien‐Dindo in mild (I/II) and severe (III/IV) complications

None of the three identified studies collected data on the occurrence of postoperative complications according to the Clavien‐Dindo classification.

Incidence of postoperative ileus

A total of 709 participants from 2 studies were included in this meta‐analysis. The results indicated that the incidence of postoperative ileus was equal in the MBP+oAB and the oAB alone group (RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.68 to 2.33; P = 0.47, I² = 0%; Analysis 2.4). The overall certainty of the evidence was low, downgraded by two levels due to some concerns about the risk of bias in the included studies and a small sample size, limited number of events, and rather wide confidence intervals, indicating possible imprecision.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2: MBP+oAB vs. oAB, Outcome 4: Incidence of postoperative ileus

Length of hospital stay (LOS)

Both Zmora 2003 and Ram 2005 found no significant differences in the length of hospital stay between the MBP+oAB and the oAB groups. The mean difference between the groups was 0.1 respectively 0.2 (95% CI ‐0.68 to 1.08) days.

Side effects of the Intervention

None of the three identified studies provided data on the occurrence of side effects of the intervention.

C. difficile‐related diarrhoea

The detection rate of C. difficile toxin was collected both pre‐ and postoperatively by Suzuki 2020. It was demonstrated that the number of C. difficile detections tended to increase after surgery in all groups, although the absolute number was quite low. C. difficile‐related diarrhoea was not observed in any group.

Sensitivity analysis

No sensitivity analyses were performed for this comparison as all studies were judged as "some concerns".