Abstract

Background:

Little research addresses the experiences of autistic people at work, yet employment prospects remain bleak. The extant literature takes a largely remedial perspective and does not focus on harnessing this population's considerable talents. In global organizational practice, several programs purposefully target autistic people for their abilities. However, preliminary evidence suggests that such programs are inadvertently attracting mainly White males, to the exclusion of other demographics. Therefore, stigma surrounding autism at work remains, creating potential compound adverse impacts by marginalizing identities, including gender, race, ethnicity, sexuality, and socioeconomic status. We explored the intersection of autism with other marginalizing identities in the context of work. The research focused on labor force participation for autistic people and, for those in employment, perceptions of exclusion and inclusion. We compared the aforementioned variables by gender identity, racial identity, sexuality, socioeconomic background, and geographic origin.

Methods:

We undertook a global cross-sectional survey, advertised through various social media platforms and promoted directly to relevant organizations. The survey included a range of validated measures as well as demographic information. We analyzed the data with frequencies, cross tabulations, chi-square tests, and non-parametric, group-wise comparisons.

Results:

We found preliminary evidence of reduced rates of employment participation by race and geographic location. Females and non-binary people had lower perceptions of inclusion and belonging at work. The perception of accommodation provision had a strong association with inclusion and belonging; more so than incidental provision of flexibility in environment and scheduling not framed as a specific accommodation.

Conclusions:

The findings highlight the relational aspects of accommodation and a more universal inclusion perspective. We urge practitioners and researchers to monitor employment participation and levels of inclusion/exclusion using intersectional demographic identification. We appeal for cross-cultural collaboration with academic institutions outside the anglosphere to improve our knowledge of global programs and their impact.

Keywords: autism hiring, autism employment, intersectionality, equality, diversity, inclusion, and belonging (EDIB), stigma theory, autism, race, gender, sexual orientation

Community brief

Why is this an important issue?

Employment data show that autistic people find it harder to get and keep work. This study focuses on understanding whether multiple identities and people's background make a difference.

What is the purpose of this study?

We asked a group of Autistic people about gender and race, as well as being gay lesbian, bisexual, transgender or queer (LGBTQ). We asked where people live, their education, parents' education and whether they had any diagnoses in addition to autism. We predicted that these things would have a negative effect on autistic employment rates. We thought they would also affect how autistic people felt at work.

What we did?

An online survey was completed by 576 autistic people. We analyzed whether their identities and backgrounds made it more or less likely that they were in work. We then asked the 387 employed people within this group about their experiences at work. We compared their experiences by identity and background to see whether these made a positive or negative difference.

What we found?

We found that White Autistic people living in western countries such as the United States and Europe were more likely to have jobs. They were also more likely to have jobs specifically designed for Autistic people. We found that women, non-binary, and transgender autistic people felt less included at work. We also found that feeling that someone cares is more important than any adjustments to work scheduling such as flexible working to support people.

What do these findings add to what was already known?

It is already known that autistic people are less likely to be in work than non-autistic people. This study shows that these overall numbers are masking important differences arising from gender, race, and ethnicity.

What are the potential weaknesses in the study?

The survey was taken at one point in time, which does not explain how these differences happened. Most people who completed the study were highly educated. We did not have enough people from the non-western countries or communities of color. Therefore, the sample is not large or diverse enough to draw firm conclusions.

How will the study help Autistic people now or in the future?

We hope that the study inspires people to think about different identities and additional stigma for autism at work programs. We have provided a sample of baseline data from all over the world that shows a difference by location. Even though this is just a trend, it might spark more research looking at the crossover between autism, identities, and backgrounds. It provides a starting point to help researchers who want to do longer studies that test interventions to improve autistic participation and experiences in work.

Introduction

Autism is a neurodevelopmental difference that affects 1% of the global population.1 Autism affects communication, cognition, and sensory perception2 and is widely reported to be genetic in origin.3 From a medical model perspective, autism is considered disabling because such differences are framed as neurological deficits frequently co-occurring with other neurodevelopmental conditions, such as intellectual disability (ID; 33% overlap),1 attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (21%–78%),4 dyspraxia (∼7%),5 and tic disorders (4%–20%).6

Autism is a spectrum condition that varies between individuals from high levels of support required to comparatively minor needs, which may change through the life span.7 The social model of disability8 focuses on the interaction between people and their context. This model argues for environmental adaptations to enable everyone to participate in society and fulfill their potential and highlights the importance of other potential marginalizing aspects of identity and background, such as gender identity and race.

From this perspective, we focus on the experience of autistic people at work and potential intersection with other demographics to inhibit both labor force participation and the experience of workplace belonging. To contextualize our approach, we outline how intersections currently affect diagnoses, before turning to the relatively sparse literature on autism and work. We make a case for a considered intersectional perspective given that stigma about visible characteristics (such as ethnically minoritized positions)9 and hidden disablement remain stark.10

Prevalence rates and disparities

Autism has been commonly thought to affect more males than females (ranging on average a 4.2:1 ratio worldwide)1 although researchers and advocates alike increasingly criticized the diagnostic methods as gender- and culture-bound and unreliable.11 Such disparities in diagnosis carry risks of negatively affecting understanding, support, and accommodation for undiagnosed women and girls.12 To elucidate, the ratio variability between cultures supports claims for female underdiagnosis, ranging from 1.1:1 in Africa to 4.7:1 in the Western Pacific.1

A United Kingdom-based study with narrower geographical boundaries compared the ratio of male to female diagnosis in children and found ranges from 2:1 to 12:1, dependent on the respective education authority.13 Disparities in diagnosis have a direct impact on the provision of support as Black children were being diagnosed at similar rates to White children (though more frequently than Asian and Roma children); yet there was a ratio of 15.71:1 for White boys compared with Black girls regarding formal agreement of educational support.

Research further suggests that socioeconomic class negatively affects the provision of support for less advantaged communities14 and that the prevalence of autism appears to intersect with sexual orientation, with a higher prevalence in transgender communities without clear explanation.15–17 In summary, variability in access to diagnosis and early support contributes to increased risk of social exclusion,12 even though active support for a positive identity increases the likelihood of gainful and meaningful work experiences.

Autism and work

Work has a central role for addressing health inequalities18 but there is a generic shortage of intervention studies providing evidence for effective workplace support as well as lack of data on labor force participation. Regarding autistic people, previous interventions have been targeted at those with co-occurring ID and, though successful, were intensive, costly19,20 and biased toward White autistic people,21 ranging from the remedial “fixing” behaviors to those highlighting specialized and unique skill sets22 of autistic people.

Labor force participation

Legal protections about the right to employment for disabled people and other protected conditions/identities around the globe23–26 have not materialized into a reduction in the autism employment gap. Only 22% of autistic people are in employment,27 indicating consistent marginalization and labor force exclusion.28 This is evident from a UK data comparison of physical conditions and other disabilities (including mental health conditions) as the lowest employment rate in this particular comparison.

The average disability employment across all conditions was cited as 52.7% for all disabled people against 81% for non-disabled people. Observed data are similar in the United States, where it is estimated that fewer than 40% of autistic adults were in work.29 National and international data, thus, raise the question of what can be done to improve work and career outcomes for this demographic. Although there is some knowledge about disparities in employment statistics for autism as a whole, we know far less about how this affects autistic people with further marginalized identities, indicating the need for intersectional analysis. We also know less about how to effectively support autistic careers, including identifying opportunities and/or barriers for promotion, progression, and career advancement.

Autism-specific programs at work

The equality, diversity, inclusion, and belonging (EDIB) agenda has gained momentum in modern economies across private and public organizations. Concurrently, the Neurodiversity movement, which frames biological differences (including neurodevelopmental conditions such as autism) as natural variations in human functioning, has begun to influence public discourse, awareness, and organizational practice.30–32

These movements suggest a need to move toward more inclusive practice for autistic people that is underpinned by context-relevant scientific evidence. There has been a proliferation of affirmative action programs designed to attract autistic people into the workforce on the basis of their talent—hereafter termed “autism-specific employment.”33 Autism-specific employment programs are frequently lauded in popular press and business literature,34,35 but they lack sufficient academic scrutiny concerning their access and entry criteria.

Michael Bernick, a disability law specialist, reported in Forbes in 202136 that the “autism at work” program started by SAP in 2015 has been joined by other large employers, including Microsoft and EY. However, the total number employed on these schemes still amounts to fewer than 800. In total, Bernick estimates that only around 1500 employees are employed via autism-specific hiring, indicating that they alone are not likely to remediate the systemic underemployment of autistic people across society. Autism-specific hiring could, however, provide insight into the experiences of autistic people at work and thus signpost how employers more broadly could facilitate greater inclusion.

Autistic experience at work

Existing research presents a complex picture of autistic experiences when in work. One German study considered the perceptions of autistic people comparing general and autism-specific employment experiences. Interestingly, the autism-specific participants all self-reported as male and weighted toward technology-focused roles.28 Study participants reported more social problems in non-autism-specific work and rated these as very important, whereas people in autism-specific work faced more job demand issues, while rating these as less important than social problems.

The authors (ibid) argue that it is important to better understand stigma-related threat and protective mechanisms when designing and delivering interventions. Similarly, Hayward et al.33 compared positive and negative experiences of work between autistic and non-autistic employees in a mixed-methods study. Their results also point to the central importance of good communication and social interactions that cater to the preferences of autistic people. Both studies indicate that perceptions of belonging and inclusion are likely to increase employment participation and progression.

Ohl et al.29 found that disclosure of autism was correlated with a three-fold increase in employment participation and rendering it plausible that a perceived de-stigmatization of autism leads to increased work resources. This observation dovetails with psychosocial theoretical frameworks about inclusion/exclusion, such as stigma theory, which we turn to next, explored.

Stigma and intersectionality: theoretical framing

Stigma theory has a broad scope that dates back decades to Goffman's work in 1963.37 He defined stigma as “undesirable attributes” (sic, p. 131) that are incongruous with people's stereotypes of what an individual should be like as an innate attribute of human functioning. Such conceptualization has been much critiqued, specifically in the context of autism.38 The Neurodiversity paradigm39 has argued for a more holistic consideration that acknowledges societal influences (including labor force participation) on stigma as a result of exclusion rather than the cause.

The untapped talent argument40 argues that we should “decouple” stigma to harness the opportunities of contemporary employment. This requires reconceptualizing autism from a “syndrome of deficits”38(p. 1) toward an essential feature of human cognitive diversity.41 Although such narrative is beginning to shape popular understanding, the disproportionate exclusion of autistic people appears to indicate that stigmatized stereotypes that preclude inclusion at work continue to prevail. Stigma theory provides an underlying explanatory framework for understanding the disparity in autism employment rates.

Grounded in the broader concept of stigma, we drew on the intersectionality theory,42 which conceptualizes the dynamics and tensions of a variety of difference and sameness (rather than “single axis thinking”).43,44 First, we consider the organizational level to address the issue of invisibility, as per the original conceptualization of Dr Kimberlé Crenshaw. When an organization considers inclusion per category, they might find that they are improving proportional representation of Black people, or women, for example. They might have good representation of disability, or specifically autistic people.

However, they may not have representation of Black autistic people or autistic women, or Black autistic women; consequently, the experience of intersecting identities is overlooked in organizational data. According to the intersectionality theory, there is a risk that EDIB activity that focuses on one marginalizing characteristic at a time overlooks the experience of multiple identities, which might explain why there are fewer women in autism-specific hiring programs, for example.28

Invisibility and masking

We note that invisibility regarding targeted inclusion activities is likely to have a psychological impact via the mechanism of “masking,” a strategy to reduce stigma.45 Autistic masking refers to attempts to conform to non-autistic behavioral norms, a process known to be more prevalent in autistic women46 and complicated by transgender status.47 An example might be self-enforced eye contact during social interactions. A similar concept is called “code-switching,” which originated in understanding second language acquisition in linguistics and now adopted in gender, race, and sexual orientation research.48–50

Both phrases refer to a process where individuals attempt to minimize differences in their speech, body language, and cultural references compared with the dominant identity to “fit in” and therefore to reduce any stigma they might experience. Whether consciously or subconsciously, the purpose of masking is to reduce exclusion and enhance opportunity for the marginalized person. However, masking comes at a cost. Raymaker et al.51 found that the cognitive and emotional costs of masking for autistic people led to burnout and dropping out of work.

Compound adverse effects may be created when autism intersects with other identities (i.e., gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, socioeconomic status [SES], and other attributes.)21,46,52,53 Johnson and Joshi12 identified that those with an early diagnosis experienced less self-stigmatization and sourced work roles and environments that closely matched their authentic skills and work style, decreasing the need for masking. However, if diagnosis is restricted by race and gender, and complicated by sexuality and transgender status, such identities create hidden barriers in the workplace.

Research questions

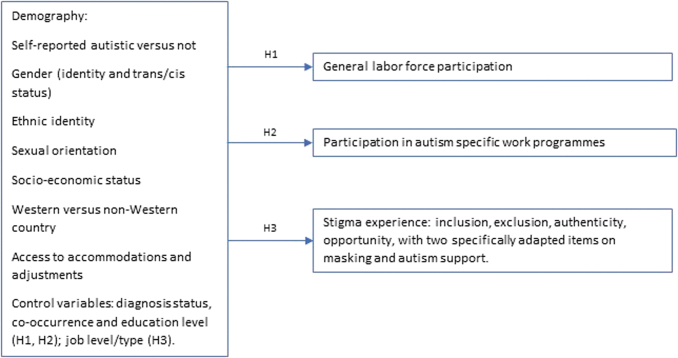

We position this study as pump-priming research to gather data about the intersection of personal experiences of work, including labor force participation and stigma, with prevalence data regarding identities such as gender, race, and sexual orientation in relation to experience of autism-specific hiring and general experience of autistic people at work. We outline our indicative model in Figure 1. We tested the following exploratory hypotheses:

FIG. 1.

Independent and dependent variables in our hypothetical model.

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Employment status

Participation in the workplace, defined as current, paid work, self-employment, or autism-specific hiring, will be lower for autistic people who are:

(a) Female or non-binary compared with male

(b) Black, Brown, Indigenous, or Mixed Heritage compared with White

(c) Lesbian, Bisexual, Gay, Queer, or other compared with heterosexual

(d) Transgender compared with cisgender (same as assigned at birth)

(e) From a low SES background compared with a high SES background

(f) Not living in Western countries compared with Western countries.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Autism-specific hiring will be lower for autistic people who are:

(a) Female or non-binary compared with male

(b) Black, Brown, Indigenous, or Mixed Heritage compared with White

(c) Lesbian, Bisexual, Gay, Queer, or other compared with heterosexual

(d) Transgender compared with cisgender (same as assigned at birth)

(e) From a low SES background compared with a high SES background

(f) Not living in Western countries compared with Western countries.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Experience

Self-reported measures of stigma (including a sense of inclusion, exclusion, authenticity, and specifically masking) will be rated worse by employed autistic people who are:

(a) Female or non-binary compared with male

(b) Black, Brown, Indigenous, or Mixed Heritage compared with White

(c) Lesbian, Bisexual, Gay, Queer, or other compared with heterosexual

(d) Transgender compared with cisgender (same as assigned at birth)

(e) From a low SES background compared with a high SES background

(f) Not living in Western countries compared with Western countries

(g) Unable to access adjustments/accommodations (perception of personalized accommodation, or general provision of flexible time and location).

Methods

This study received approval from the Ethics Committee of Birkbeck College, University of London in January 2021, as part of the Centre for Neurodiversity Research at Work, which is staffed and led by neurodivergent researchers. We situate our approach within a critical realist paradigm.54

User involvement

To facilitate inclusive design and user involvement, we shared the draft questionnaire with six independent autistic individuals who formed a focus group before survey commencement and asked for detailed feedback on survey layout, instructions, and item wording. We wanted to avoid the typical pitfalls of working with autistic participants by preparing for a breadth and depth of idiosyncratic answers in data collection.55 The focus group reported several errors and omissions, as well as ambiguities in the questions.

Full details of the edits and recalculated alphas for the sample data are provided in Supplementary Appendix SA1, with a summary below in the Measures section. The intention was to provide a replicable model for follow-up studies to compare our sample with non-autistic samples. However, to accommodate the user feedback, we amended the survey instructions to clarify that validated scales are habitually written with a non-autistic norm in mind, and that it was our aim to understand overall experience.

Our focus group agreed that this would support autistic participants in making “best guess” responses rather than becoming frustrated by the lack of precision. We additionally provided autism-relevant examples in two items to reduce ambiguity. Focus group members were paid an honorarium of £150 for their time.

Survey distribution and sampling strategy

We initially distributed the survey using a convenience approach via social media (LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram) in February 2021 via the first and third authors' personal and professional accounts. As well as public posting, the first and corresponding researchers sent direct messages to all their primary LinkedIn contacts and sourced LinkedIn members (respectively), filtered under the term “autism”; this numbered more than 700 direct messages.

The information sheet expressly targeted both diagnosed and self-diagnosed participants in recognition of systemic discrimination toward access to diagnosis and biased diagnostic criteria.13,56,57 We attempted a purposive sample by directly approaching companies associated with autism-specific hiring to support dissemination of the study. However, none responded positively and take-up from those citing autism-specific roles was low (n = 19), though we note the overall low participation rates of these programs cited above as 1500 worldwide.

After 1 month, we reviewed demographic participation and identified a low take-up in communities of color. The researchers adapted to a purposive sample strategy, targeting additional responses with the support of Black and Brown influential social media accounts to improve response rates and address sampling bias. These efforts generated further feedback from the account holders, indicating that the purpose of the study was unclear, as well as highlighting the limitation of the White racial profile of the primary researchers.

In response, the information sheet and messaging were edited to improve clarity on the research goals, such as understanding intersectional exclusion. Black and Brown members of the assistant research team and the Advisory Board at our research centre in London personally extended the call for participation, which generated a higher response rate from autists with corresponding racial profiles. Despite our efforts, the number of responses from communities of color remained low, and we took the decision to group all Black, Indigenous People of Color (BIPOC) from the Global Ethnic Majority (GEM) as one group, to compare against White participants.

We also had difficulty recruiting from developing nations and so re-grouped the geographical categories to balance the groups sizes more equitably. We acknowledge the problematic nature of this decision and split the analyses more finely where possible. We will return to this point in the Study Limitations section.

The survey was kept open for 6 months to maximize opportunity for participation. Survey respondents were not recompensed for their time. Instead, a donation of £2 for each survey completed was provided to Tourette's Action; a UK charity supporting a significantly underfunded neurominority condition.

Sample

Our final sample had just more than 600 responses. Anyone under the age of eighteen would have been removed, however there were no cases of children entering details. Anyone who did not consent or confirm a diagnosis or self-diagnosis of autism was unable to proceed with the questionnaire. Several responses were excluded because they had withdrawn after the first three demographic questions, resulting in a final N = 576. There was a high representation of gender diversity (53.8% female), including non-binary (10.9%) and transgender (8.7%), as well as Lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, intersex, a-sexual (LGBQIA) (40.5%). Table 1 shows the demographic profile of the sample and a summary of descriptive data for all variables.

Table 1.

Demographic Representation of Sample (Frequency and Descriptive Data)

| Demographic | Description | Number (percentage) |

|---|---|---|

| Autism diagnosis | Diagnosed by a health professional | 394 (68.9) |

| Diagnosed by a different professional | 49 (8.6) | |

| Self-diagnosed | 129 (22.6) | |

| Co-occurring neurodivergence | At least one co-occurring ND | 386 (67) |

| ADHD | 206 (41.5) | |

| Dyscalculia | 56 (9.7) | |

| Dyslexia | 79 (13.7) | |

| Dyspraxia/DCD | 112 (19.4) | |

| Sensory processing disorder | 170 (29.5) | |

| Tic disorder | 22 (3.8) | |

| Co-occurring mental health need | At least one co-occurring MH need | 420 (73) |

| Anxiety | 370 (64.2) | |

| Depression | 279 (48.4) | |

| OCD | 76 (13.2) | |

| Phobia | 38 (6.6) | |

| SAD | 68 (11.8) | |

| Other | 111 (19.3) | |

| Gender identity | Female | 310 (53.8) |

| Male | 181 (31.4) | |

| Non-binary | 63 (10.9) | |

| Prefer not to say | 22 (3.8) | |

| Gender status | Cisgender (identifies as same gender as birth) | 481 (83.5) |

| Transgender | 50 (8.7) | |

| Prefer not to say | 45 (7.8) | |

| LGBQ status | Heterosexual | 304 (52.8) |

| Lesbian, bisexual, gay, queer, intersex, pansexual, asexual | 233 (40.5) | |

| Prefer not to say | 39 (6.8) | |

| Race/ethnicity | Asian | 32 (5.6) |

| Black | 33 (5.7) | |

| Hispanic | 12 (2.1) | |

| Indigenous | 1 (0.2) | |

| White | 436 (75.7) | |

| Mixed heritage | 45 (7.8) | |

| Prefer not to say/other | 17 (2.9) | |

| Location | North America | 118 (20.5) |

| Europe | 358 (62.2) | |

| Australasia | 37 (6.4) | |

| RoW | 59 (10.2) | |

| SES—Parents Education Level (a proxy measure) | No education | 86 (14.9) |

| Educated to High School level | 161 (28) | |

| Graduate or higher | 294 (51) | |

| Prefer not to say | 35 (6.1) | |

| Education level of participant | No education or High School only | 54 (12.8) |

| Some College or undergraduate complete | 251 (43.6) | |

| Post-graduate education complete | 251 (43.6) | |

| Employment status | Total employed | 387 (67.2) |

| Total unemployed | 189 (32.8) | |

| Autism-specific role (i.e., a role only offered to autistic people as part of affirmative action) | Autism-specific role | 19 (3.3) |

| Tried and failed to get an Autism-specific role | 14 (2.4) | |

| Unemployed and had not attempted an Autism-specific role | 148 (25.7) | |

| Applied and obtained role through neurotypical norms | 368 (63.9) | |

| Job features (hours, location, other) | Flexible hours | 161 (28) |

| Remote or blended location | 238 (41.3) | |

| Provided with other accommodations always/sometimes | 155 (26.9) | |

| Industry | Education, coaching, training, case management | 58 (10.1) |

| Professional Services incl. government | 54 (9.4) | |

| Software | 48 (8.3) | |

| Health and social care | 44 (7.6) | |

| Life, defense, and social sciences | 18 (3.1) | |

| Media, entertainment, and creative industries | 13 (2.3) | |

| Hardware | 8 (1.4) | |

| Other industries not ≤7 in each category, for example, retail, banking, telecoms, food and staples, energy, real estate, and transport. | ||

| Total participants | 576 | |

| Age | M = 38.6, SD = 10.758, range 17–67 years | |

| Workplace Exclusion Scale | M = 4.740, SD = 1.201, range 1–7 | |

| Perceived Group Inclusion Scale (inclusion) | M = 2.553, SD = 1.036, range 1–5 | |

| Perceived Group Inclusion Scale (authenticity) | M = 2.914, SD = 1.107, range 1–5 | |

| Autism item 1—masking | M = 3.17, SD = 1.312, range 1–5 | |

| Autism item 2—support for stimming/meltdowns | M = 3.28, SD = 1.296, range 1–5 | |

ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; DCD, developmental coordination disorder; LGBQ, lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer and other; MH, mental health; ND, neurodivergence; OCD, obsessive compulsive disorder; RoW, Rest of World; SAD, seasonally affected disorder; SD, standard deviation; SES, socioeconomic status.

Measures

Descriptive data for the scales are detailed in Table 1 and the full survey items and adaptations in Supplementary Appendix SA1. All participants (N = 576) answered demographic questions, and those who stated they were employed (n = 387) were directed to answer specific questions about the nature and experience of their work, whereas those who stated they were not employed (n = 189) were directed to answer questions enquiring as to the reasons.

Independent variables regarding identity and background

These included: gender identity and gender status (cis/trans), sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, nationality, and parents' educational level (as a proxy for SES). We also captured co-occurrence of a secondary diagnosis of other neurodevelopmental conditions/mental health needs, diagnosis status (self- vs. professional diagnosis), and level of participant education as control variables.

Dependent variables on participation

To answer labor force participation (H1 and H2), we first asked whether participants were employed (yes/no). Two participants enquired by email as to whether self-employment counted as employment, to which we answered yes. A total of 387 participants reported being employed; these participants were further directed to answer first whether their employment was autism-specific or general and then on to questions related to stigma at work. For the 189 participants who were not employed, we asked whether or not they had tried to acquire work through an autism-specific scheme and what the reasons for this might be.

Dependent variables on experience

To understand the experience of stigma at work (H3), we selected relevant items from existing proxy instruments, all with Likert scale-style answers (interval rather than scaled response data): The Workplace Exclusion Scale (WES)58 and Perceived Group Inclusion Scale (PGIS).59 We recalculated alpha co-efficients to assess compatibility of the adapted measures for this particular sample, which were 0.97 and 0.88 respectively.

We concluded these were sufficiently reliable to proceed, though we note that 0.97 is very high and there is a risk our participants were answering each item in the WES without consideration to the nuance of different items. The WES (14 items) ranged from 1 to 7 in terms of frequency of occurrence (1 being all the time, a negative statement; 7 being never, a positive statement). The PGIS (16 items) ranged from 1 to 5 in terms of agreement with statements (1 being strongly agree, a positive statement; 5 being strongly disagree, a negative statement).

The PGIS included items specific to the ability to present one's authentic self and two of these items were adapted to be specific to the workplace and an autistic sample, by specifically referencing masking and the presence of autism-specific behaviors, such as stimming and overwhelm. The adapted items were as follows, with our additions shown in italics:

Overall, the employers at my place of work allow me to be authentic (i.e., without the need to for autistic masking).

Overall, the employers at my place of work allow me to be who I am (i.e., safe space to stim, with support and acknowledgement for shut down/meltdown).

Our focus group reported qualitatively different experiences within the PGIS and also when asked directly about behaviors linked to autism (the masking and support items). Although their feedback was not confirmed by factor analysis, we find to be outside of the remit of this study, we respectfully made the decision to present the data accordingly. Our approach, therefore, generated three dependent variables: WES, PGIS 1, and PGIS 2. These are named exclusion, inclusion, and authenticity, respectively.

We calculated a mean for each scale, per participant for analysis. We also took the decision to draw out the two autism-specific adapted items as separate analyses, due to their high fidelity with expected experience and to address the possibility that measures created for non-autistic populations are less sensitive to the experience of autistic participants.60

Independent variables to understand workplace experience

We refined our understanding of the influences on experiences with the creation of additional independent variables for the employed group, which centered on the provision of accommodations. We directly asked about their ability to work flexible hours or choose location, as these are frequently recommended in practice guidance as reasonable accommodations for autistic people.61,62

However, we also asked a single question about the extent to which respondents felt they were provided with adjustments/accommodations, because (1) the perception of being accommodated (or not) is relevant to exclusion/inclusion, irrespective of the demands of the actual job, (2) flexibility in location and hours are not specific to disability or autism, and (3) there is little evidence that accommodations in practice are effective.40 We also used the autism-specific hiring variable (yes/no) and the level at which the individual worked as independent variables for this analysis.

Analysis

A prior g-power analysis indicated that a sample size of >500 would be sufficient for hierarchical regression analysis, however this was discounted due to abnormally distributed dependent variables and the unevenly sized independent variables. We instead used a series of crosstabs with Chi-square analysis to assess H1 and H2 across the comparative representation of demographics in working and unemployed populations.

For workplace experience, the three dependent variables were irretrievably skewed and/or platykurtic, hence we undertook non-parametric comparisons where needed (Kruskall-Wallis/Mann Whitney U).63 We note that the original scales developed using non-autistic populations were normally distributed,58,59 whereas this sample tended toward a positive experience of inclusion and lower-than-expected exclusion.

A Bonferroni correction divider was calculated based on five dependent variables (exclusion, inclusion, authenticity, and the two autism-specific items), but with an adjustment to avoid type II error,64 hence dividing 5 by 1.5, then rounded to the nearest integer, which is three, resulting in a p-value limit of <0.017. We took a cautious approach to discounting trends, due to the uneven independent group sizes. Those that are near significance were reported, with additional effect size calculations for marginal/significant results (Cohen's d for the Chi Squares,65 eta squared for the Kruskall-Wallis and Glass-rank serial correlation for the Mann Whitney U)66 and a post hoc power check on marginal results.67

We provide descriptive data only on the perceived reasons for unemployment. Although incidental to our research questions, we compared formal versus self-diagnosis and co-occurrence by demographic data using crosstabs and chi-square, an opportunistic analysis as a matter of community and professional interest. All analyses were conducted using SPSS v26, except the effect sizes that were hand calculated based on SPSS output using formulae as per the citations above.

Results

Identity and background

Table 1 depicts the demographic characteristics for the sample, including their identity and background measures.

Employment status

The representation of autistic people in work (Yes)/not in work (No) as well as the representation on autism-specific hiring programs (Yes)/non-autistic employment (No) are presented in Tables 2 and 3 with cross-tabs and chi-square analyses.

Table 2.

Associations Between Identity/Background and Employment Status

| Demographic | Employed | Unemployed | Chi-square |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender identity | |||

| Male result | 128 (71%) | 53 (29%) | χ2(2) = 0.317, p = 0.854 |

| Male expected (exp.) | 125.1 | 55.9 | |

| Female result | 212 (68%) | 98 (32%) | |

| Female exp. | 214.3 | 95.7 | |

| Non-binary result | 43 (68%) | 20 (32%) | |

| Non-binary exp. | 43.6 | 19.4 | |

| Gender status | |||

| Trans result | 29 (58%) | 21 (42%) | χ2(1) = 2.962, p = 0.085 |

| Trans exp. | 34.4 | 15.6 | |

| Cis result | 336 (70%) | 145 (30%) | |

| Cis exp. | 330.6 | 150.4 | |

| LGBQ+ compared with heterosexual | |||

| LGBQ+ result | 157 (67%) | 76 (33%) | χ2(1) = 1.173, p = 0.279 |

| LGBQ+ exp. | 162.7 | 70.3 | |

| Heterosexual result | 218 (72%) | 86 (28%) | |

| Heterosexual exp. | 212.3 | 91.7 | |

| Race/Ethnicity (summarized as “GEM”) compared with Whitea,** | |||

| GEM result | 44 (57%) | 33 (43%) | χ2(1) = 7.107, p = 0.008, d = 0.236 a |

| GEM exp. | 53.9 | 23.1 | |

| White result | 315 (72%) | 121 (28%) | |

| White exp. | 305 | 130 | |

| Locationb | |||

| North America result | 79 (67%) | 39 (33%) | χ2(3) = 8.152, p = 0.043, d = 0.169 |

| North America exp. | 79.9 | 38.4 | |

| Europe result | 253 (71%) | 105 (29%) | |

| Europe exp. | 241.6 | 116.4 | |

| Australasia result | 23 (62%) | 14 (38%) | |

| Australasia exp. | 25 | 12 | |

| RoW result | 31 (53%) | 28 (47%) | |

| RoW exp. | 39.8 | 19.2 | |

| SES | |||

| Low SES result | 63 (73%) | 23 (27%) | χ2(2) = 3.905, p = 0.142 |

| Low SES exp. | 59 | 27 | |

| Med SES result | 117 (73%) | 44 (27%) | |

| Med SES exp. | 110.4 | 40.6 | |

| High SES result | 191 (65%) | 103 (35%) | |

| High SES exp. | 201.6 | 92.4 | |

Result reported first (with percentages in parentheses) followed by expected count, as determined by relative prevalence, shown in italics.

Results emboldened are significant or near significant.

p < 0.01; bp < 0.05.

p < .001.

GEM, global ethnic majority.

Table 3.

Associations Between Identity/Background and Autism-Specific Hiring

| Demographic | In an autism-specific role | In a general employment role | Chi square |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender identity** | |||

| Male result | 14 (11%) | 114 (89%) | χ2(2) = 16.986, p < 0.001, d = 0.386** |

| Male expected (exp.) | 5.8 | 117.2 | |

| Female result | 2 (0.01) | 208 (99.9%) | |

| Female exp. | 10.2 | 206.5 | |

| Non-binary result | 0 (0%) | 43 (100%) | |

| Non-binary exp. | 2 | 41.3 | |

| Gender status | |||

| Trans result | 0 (0%) | 29 (100%) | χ2(1) = 1.539, p = 0.215 |

| Trans exp. | 1.4 | 27.6 | |

| Cis result | 17 (0.05%) | 319 (99.95%) | |

| Cis exp. | 15.6 | 320.4 | |

| LGBQ+ compared with heterosexual | |||

| LGBQ+ result | 5 (0.03%) | 152 (99.97%) | χ2(1) = 0.774, p = 0.379 |

| LGBQ+ exp. | 6.7 | 150.3 | |

| Heterosexual result | 11 (0.05%) | 207 (99.95%) | |

| Heterosexual exp. | 9.3 | 208.7 | |

| GEM/White | |||

| GEM result | 3 (0.07%) | 41 (99.93%) | χ2(1) = 0.343, p = 0.558 |

| GEM exp. | 2.2 | 41.8 | |

| White result | 14 (0.04%) | 300 (99.96%) | |

| White exp. | 15.8 | 299.2 | |

| Location | |||

| North America result | 4 (0.05%) | 75 (99.95%) | χ2(3) = 2.074, p = 0.557, |

| North America exp. | 3.7 | 75.3 | |

| Europe result | 10 (0.04%) | 243 (99.96%) | |

| Europe exp. | 11.8 | 241.2 | |

| Australasia result | 1 (0.04%) | 22 (99.96%) | |

| Australasia exp. | 1.1 | 21.9 | |

| RoW result | 3 (0.1%) | 28 (99.9%) | |

| RoW exp. | 1.4 | 29.6 | |

| SES | |||

| Low SES result | 2 (0.03%) | 61 (99.97%) | χ2(2) = 1.482, p = 0.477 |

| Low SES exp. | 2.5 | 60.5 | |

| Med SES result | 3 (0.03%) | 114 (99.97%) | |

| Med SES exp. | 4.7 | 112.3 | |

| High SES result | 10 (0.05%) | 181 (99.95%) | |

| High SES exp. | 7.7 | 183.3 | |

Result reported first (with percentages in parentheses) followed by expected count, as determined by relative prevalence, shown in italics.

Double asterisk and emboldened numbers indicate significance.

Employment versus unemployment (H1)

We analyzed diagnosis status, co-occurrence, and education level as control variables by comparing frequencies in cross tabs; however, none of these revealed any statistically significant differences based on participants' employment status. In general, employment outcomes were significantly disproportionately lower with small effect size for BIPOC from the GEM compared with White people [χ2(1) = 7.107, p = 0.008, d = 0.236].

There was also a marginal result (although with less than small effect size) for those living outside the major western economies of North America, Europe, or Australasia [χ2(3) = 8.152, p = 0.043, d = 0.169]. Therefore, we did not find support for H1 in relation to adverse impact for gender identity, sexual orientation, transgender, nationality, or SES (a, c, d, e, f) The results did, however, support H1 for race/ethnicity (H1b) regarding employment versus unemployment.

Autism-specific hiring (H2)

We also explored representation in autism-specific hiring programs, though we advise caution regarding the interpretation of findings given the small number of responses from autistic people employed on such programs. Again, the control variables of diagnosis status, co-occurrence, and education level did not significantly affect participation in autism-specific hiring.

Table 3 shows that, even in this small sample, female and non-binary people were significantly disproportionately lacking in representation in autism-specific roles, with a small effect size [χ2(2) = 16.986, p < 0.001, d = 0.386], though no other demographic was significantly different. Therefore, we found support for gender identity disparities (H2a), but no support for H2 (race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, transgender, SES, geographical location [b–f]).

Experience of stigma (H3)

This part of our analysis only pertains to participants reporting employed status (n = 387). See Table 4 for the means, standard deviations, and test statistics for each groupwise comparison. We used Mann-Whitney U and Kruskall-Wallis H to assess the relationship between the independent variables and the dependent variables of WES, Inclusion, and Authenticity (analyzed as two from the PGIS). Again, the control variables of diagnosis status, co-occurrence, and education status did not significantly influence the experience scores; however, neither did being in an autism-specific role or not, or level of the participant's role in the organization. No support was found for the influence of their sexual orientation (H3c) or their geographical location (H3f).

Table 4.

Scale Means, Standard Deviations, and Analyses for the Experience of Stigma in Work (H3; n = 387)

| Ind. variables | Exclusion, M (SD), 1–7 scale, low is negative | Inclusion, M (SD), 1–5 scale, low is positive | Authenticity, 1–5 scale, low is positive | Masking, M (SD), 1–5 scale, low is positive | Stim/meltdown, M (SD), 1–5 scale, low is positive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 4.7 (1.2) | 2.4 (1.0) | 2.7 (1.2) | 2.8 (1.4) | 2.9 (1.3) |

| Female | 4.8 (1.2) | 2.5 (1.2) | 2.9 (1.1) | 3.3 (1.2) | 3.3 (1.3) |

| Non-binary | 4.4 (1.3) | 2.9 (1.0) | 3.3 (1.1) | 3.5 (1.4) | 3.78 (1.3) |

| H(2,279) = 2.78, p = 0.249 | H(2,298) = 7.68, p = 0.021, η = 0.016* | H(2,293) = 8.159, p = 0.017, η = 0.018* | H(2,298) = 10.077, p = 0.006, η = 0.02** | H(2,298) = 12.094, p = 0.002, η = 0.03** | |

| GEM | 4.4 (1.3) | 2.7 (1.1) | 3.3 (1.0) | 3.8 (1.1) | 4.0 (1.2) |

| White | 4.8 (1.2) | 2.5 (1.1) | 2.9 (1.1) | 3.1 (1.3) | 3.23 (1.3) |

| U(256) = 3759, p = 0.213 | U(274) = 3405, p = 0.267 | U(270) = 2886, p = 0.045, r = 0.22* | U(274) = 2664, p = 0.007, r = 0.29** | U(274) = 2616, p = 0.002, r = 0.33* | |

| Asian | 4.7 (1.6) | 2.4 (1.4) | 2.9 (1.1) | 3.3 (1.3) | 3.7 (1.4) |

| Black | 4.3 (1.1) | 2.8 (0.8) | 3.5 (0.8) | 4.2 (0.8) | 4.2 (0.9) |

| Hispanic | 4.3 (1.4) | 3.0 (1.2) | 3.4 (1.1) | 3.7 (1.2) | 3.9 (1.2) |

| White | 4.6 (1.2) | 2.5 (1.1) | 2.9 (1.1) | 3.1 (1.3) | 3.2 (1.3) |

| Mix heritage | 4.9 (1.0) | 2.5 (0.6) | 2.6 (0.7) | 3.1 (1.2) | 3.1 (1.1) |

| H(4,277) = 2.603, p = 0.626 | H(4,296) = 3.940, p = 0.414 | H(4,291) = 8.461, p = 0.076 | H(4,296) = 10.637, p = 0.031, η = 0.019* | H(4,296) = 11.342, p = 0.023, η = 0.021* | |

| LGBQa | 4.8 (1.12) | 2.5 (0.9) | 2.9 (1.1) | 3.2 (1.3) | 3.4 (1.3) |

| Heterosexual | 4.7 (1.2) | 2.6 (1.1) | 2.9 (1.1) | 3.1 (1.3) | 3.2 (1.3) |

| U(274) = 8527, p = 0.326 | U(293) = 10722, p = 0.756 | U(288) = 9890, p = 0.652 | U(293) = 9889, p = 0.368 | U(293) = 9620, p = 0.198 | |

| Transgender | 4.3 (1.1) | 3.1 (0.9) | 3.5 (1.1) | 3.5 (1.4) | 4.0 (1.3) |

| Cisgender | 4.8 (1.2) | 2.5 (1.0) | 2.9 (1.1) | 3.1 (1.3) | 3.2 (1.3) |

| U(270) = 2139, p = 0.05 | U(287) = 4450, p = 0.003, r = 0.36** | U(282) = 4141, p = 0.006, r = 0.34** | U(287) = 4230, p = 0.014, r = 0.29** | U(287) = 4462, p = 0.002**, r = 0.36** | |

| Low SES | 4.4 (1.2) | 2.7 (1.1) | 3.0 (1.2) | 3.3 (1.3) | 3.3 (1.4) |

| Medium SES | 4.9 (1.2) | 2.5 (1.0) | 2.8 (1.9) | 3.1 (1.3) | 3.1 (1.2) |

| High SES | 4.8 (1.2) | 2.5 (1.0) | 2.9 (1.1) | 3.2 (1.3) | 3.4 (1.3) |

| H(2,271) = 6.250, p = 0.044, η = 0.012* | H(2,289) = 1.835, p = 0.40 | H(2,285) = 1.727, p = 0.42 | H(2,289) = 1.83, p = 0.401 | H(2,289) = 2.102, p = 0.35 | |

| North America | 4.8 (1.2) | 2.4 (1.0) | 2.7 (1.0) | 2.9 (1.2) | 3.0 (1.3) |

| Europe | 4.7 (1.2) | 2.6 (1.0) | 3.0 (1.1) | 3.3 (1.3) | 3.3 (1.2) |

| Australasia | 4.8 (1.3) | 2.5 (1.1) | 2.7 (1.4) | 2.8 (1.5) | 3.0 (1.5) |

| RoW | 4.5 (1.0) | 2.6 (1.0) | 3.2 (1.2) | 3.6 (1.4) | 3.8 (1.3) |

| H(3,281) = 1.725, p = 0.631 | H(3,300) = 1.42, p = 0.701 | H(3,295) = 7.504, p = 0.057 | H(3,300) = 7.414, p = 0.06 | H(3,300) = 9.269, p = 0.026, η = 0.017* | |

| Accommodations | |||||

| Always | 5.4 (1.0) | 2.0 (0.9) | 2.0 (1.0) | 2.3 (1.2) | 2.2 (1.2) |

| Sometimes | 4.9 (1.1) | 2.4 (0.8) | 2.8 (0.9) | 3.0 (1.2) | 3.2 (1.1) |

| Occasionally | 4.3 (1.3) | 2.9 (1.0) | 3.3 (1.0) | 3.7 (1.2) | 3.6 (1.1) |

| Never | 4.4 (1.2) | 2.9 (1.1) | 3.4 (1.1) | 3.6 (1.3) | 3.8 (1.3) |

| H(3,279) = 34.95, p < 0.001, η = 0.11** | H(3,298) = 33.234, p < 0.001, η = 0.1** | H(3,293) = 56.811, p < 0.001, η = 0.18** | H(3,298) = 46.417, p < 0.001** | H(3,298) = 57.826, p < 0.001** |

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, intersex, a-sexual, two-spirit or other.

Emboldened numbers indicate interest. Double asterisk indicates significance, single asterisk indicates marginal significance. Italicized letters indicate test statistics.

The following analyses were significant or near significant, with small effect sizes. We found partial support for increased stigma concerning gender identity (H3a): Female and non-binary people scored lower for inclusion [H(2,298) = 7.687, p = 0.021, ƞ2 = 0.016] and authenticity [H(2,293) = 8.159, p = 0.017, ƞ2 = 0.018]. Post hoc testing revealed significant differences between non-binary and male, non-binary and female (p = 0.006–0.026), but not male and female (p = 0.121–0.316). No significant differences were found for experience of exclusion.

Being White tentatively improved experience of authenticity in the workplace [U(270) = 2886, p = 0.045, r = 0.22], a marginal significance, and a small effect size. This was not the case for exclusion or inclusion, hence providing only minimal support for race/ethnicity (H3b). Post hoc power analysis indicated a high likelihood of Type II error (β = 0.34).

We found support for the influence of gender status (H3d) as transgender participants reported significantly worse perceptions than cisgender on inclusion [U(287) = 4450, p = 0.003, r = 0.36] and authenticity [U(282) = 4140.5, p = 0.006, r = 0.34], with medium effect sizes.

We found minimal support for SES affecting experience of exclusion [H(2,271) = 6.25, p = 0.044, ƞ2 = 0.012] but not inclusion or authenticity.

The perceived presence of accommodations (H3g) significantly improved perceptions of exclusion [H(3,279) = 34.950, p < 0.001, ƞ2 = 0.11], inclusion [H(3,298) = 33.234, p < 0.001, ƞ2 = 0.10], and authenticity [H(3,293) = 56.811, p < 0.001, ƞ2 = 0.18]; with medium to large effect sizes. Post hoc comparisons revealed that the perception of having accommodations sometimes or always was significantly more beneficial than having them occasionally or never (p = 0.019 to p < 0.001).

Support is, therefore, noted for H3g in that autistic people who perceived themselves to be consistently accommodated experienced higher rates of inclusion. However, the presence of remote working and flexible hours, which are not framed as a specific accommodation (as explained above) but are frequently deployed as such, was not significantly related to inclusion, exclusion, or authenticity.

Autism-specific items

We analyzed the two items that were adapted to give examples pertaining to an autistic population specifically and separately from the aggregate exclusion, inclusion, and authenticity data. In these highly specified items, we found more nuanced differences by gender identity and race. There were significant differences with small effect sizes between genders for not feeling required to mask [masking item; H(2,298) = 10.077, p = 0.006, ƞ2 = 0.02] and feeling allowed to stim with support for shutdown [support item; H(2,298) = 12.094, p = 0.002, ƞ2 = 0.03]. In these questions, both females and non-binary people were significantly disadvantaged compared with male participants (p = 0.015–0.001). The means for non-binary people indicated greater disadvantage to females, though these differences were not significant (p = 0.543/0.059).

By race/ethnicity using the major categories of GEM/White, we found significant differences for both items with a small effect size for masking [U(274) = 2664, p = 0.007, r = 0.29] and a medium effect size for support [U(274) = 2616, p = 0.002, r = 0.33]. Using the five categories in which there was a minimum of 12 participants for each group (Table 4), we found marginally significant differences with small effect sizes for masking [H(4,296) = 10.637, p = 0.031, ƞ2 = 0.019] and support [H(4,296) = 11.342, p = 0.023, ƞ2 = 0.021]. Post hoc power analysis showed these analyses at a significant risk of Type II error (β = 0.04–0.05), hence they are reported despite being marginal.

Specifically, Black respondents perceived their need to mask as higher than those identifying as White (p = 0.003) or of mixed heritage (p = 0.008), but not compared with Asian and Hispanic respondents. Black respondents also felt less supported compared with White autists (p = 0.006), those of mixed heritage (p = 0.008) but again not compared with Asian, or Hispanic participants who were not significantly different from each other. Geography also marginally affected the perception of being supported during a stim/meltdown [H(3,300) = 9.269, p = 0.026, ƞ2 = 0.017].

Unemployment

Of the 14 people who reported having tried and failed to access an autism-specific role, 12 of these thought they were unsuccessful because they had no qualifications or experience. Of the 148 who answered that they were unemployed but had not tried to obtain an autism-specific role, the most common reason was that they did not know how to access such schemes (n = 103). This was followed by concerns about disclosure (n = 45) and limiting career options (n = 30). These are reported as descriptive data only.

Disparities in diagnoses

Although not framed as a hypothesis, we undertook exploratory, convenience analysis to see whether intersectional demographics were linked to formal diagnosis status and co-occurrence. We present only significant results as tangential, but of use to the wider autism research community. Representation in formal diagnosis (vs. self-diagnosis) was significantly weighted toward White participants [χ2(2) = 10.391, p = 0.006] and males as opposed to females/non-binary [χ2(4) = 14.442, p = 0.006], and to those living in Australasia, North America, and Europe as opposed to the rest of the world [χ2(6) = 19.524, p = 0.003].

There were no significant differences in diagnosis status according to sexual orientation, transgender or SES. Co-occurrence was significantly weighted toward males compared with females and non-binary for other neurodevelopmental conditions [χ2(2) = 38.757, p < 0.001] but not mental health needs. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual, two-spirit (LGBTQIA2S+) participants were significantly less likely to receive a co-occurring neurodivergent diagnosis than cisgender [χ2(1) = 6.107, p = 0.013] or heterosexual participants [χ2(2) = 4.270, p = 0.039]. LGBQIA (but not transgender) were also less likely to receive a mental health diagnosis than heterosexual participants [χ2(1) = 11.031, p = 0.001].

North Americans were significantly more likely to have received a diagnosis of co-occurring mental health needs than those from any other region [χ2(3) = 11.589, p = 0.009], but not other neurodivergence. Neither race nor socioeconomic class affected co-occurrence diagnosis in this sample.

Discussion

We found partial support for our hypotheses as labor force participation was affected by race/ethnicity and nationality, with White westerners holding the highest employment rate of any other group. No other group comparisons were statistically significant. Access to autism-specific roles was adversely affected by being female or non-binary, though we advise caution on this result given the low sample size. The experiences of stigma, as represented by the measures of exclusion, inclusion, authenticity as well as specifically the need to mask and being supported when stimming or in shutdown, were more nuanced. Due to the limitations in diverse participation and the highly privileged sample, we present our analysis as tentative trends for further exploration.

Participation

Comparisons by race/ethnicity and geographical location indicated hidden intersectional effects for autistic people at work since our data suggest that EDIB initiatives are not “finding” autistic people of color and are confined to Europe and the anglo-sphere of North America, the United Kingdom, and Australia. This has implications for EDIB professionals, indicating a need for a renewed interest in multi-layered diversity approaches, across departments and businesses world-wide rather than siloed activity.

Although labor force participation in general was not affected by gender, participation in autism-specific hiring programs indicated a privilege for male autists. The low response rate for this subgroup was regrettable, however there are low numbers for this group worldwide. We suggest that the programs may have more marketing than actual value for enhancing workforce participation. To start, we ask all relevant providers to transparently monitor and share participation and retention statistics, demographic data and to make concerted efforts for appeal and participation across all autistic people.

More specifically, including women to operate in fields beyond the technology sector and to acknowledge the high number of autists working in education, professional services, health care, science, and media is demonstrated in our sample demographics (Table 1). Solutions for improving autism employment rates should promote a holistic perspective to avoid pigeon-holing autistic people to the trope of the White, male technologist.

Our findings indicate a lack of consistent access to programs (outside North America) and concerns regarding the limitations of disclosing confidential medical information on future careers. Though the latter concerns are reported here as qualitative and not generalizable, they are of interest in terms of legal concerns (confidentiality and data protection) and should be further explored by providers/employers. We need a critical and informed perspective on potential long-term implications for careers in different contexts. For example, (1) the risks of open disclosure where cultures associate more stigma with autism as well as (2) insight into reducing intersectional adverse impact in hiring, specifically where sexual orientation/transgender is criminalized or where gender and income inequalities are more pronounced.

Systemic workplace inclusion for autistic and disabled people, more broadly, needs to accommodate the reality of access to opportunities that are limited by race, ethnicity, gender, and geographical location. Diversity and inclusion professionals need to work together on intersectional inclusion, as opposed to initiating interventions one demographic at a time.

Experience

We found significant and strong effects for the impact of gender identity, gender status, and race/ethnicity on experiences of stigma in the workplace. We note that the strongest evidence related to questions adapted to include examples pertaining specifically to autistic experience, reinforcing critiques that generalist measures cannot be assumed to have validity for this population.60

Sexuality and SES had less impact on workplace experience, which chimes with previous research on stigma and inclusion, which highlight the greater negative effect of non-concealable differences37 compared with those which could be less visible or can be disguised. However, the enhanced possibility of masking does not mitigate the potential long-term effects of masking and so this result should not be interpreted as an indication of less marginalization for these groups—just a difference. It should also be noted that the ability to “pass as heterosexual” is not uniform among the LGBQIA community and nor is the visibility of color, with many Black Brown and mixed heritage people able to “pass for White.”

Surprisingly, we found that provision of flexible hours and location, which are frequently recommended as accommodations for this group in practice68 (thought to be essential for reducing environmental and commuting sensory overwhelm), were not significantly correlated with feelings of inclusion. This finding indicates a disconnect between heuristical advice and individual experience, indicating a need for more theoretically grounded research into the mechanisms by which accommodations achieve inclusion. Conversely, we found that perceptions of accommodation were, by far, the strongest and most compelling result in terms of predicting experience in the workplace; this is a significant signpost for practitioners and employers.

To understand this result, we draw from industrial/organizational psychology. Workplace well-being research has highlighted that workplace support is more effective if it is targeted and domain-specific.69 We contend that the same logic might apply here, indicating a need to educate organizations not only on the compliance-focused provision of any accommodations, but crucially also specific organizational and managerial support.

Given that research to date28,29,51 draws out the importance of social support, it may be that the feeling of being accommodated (e.g., following conversations that allow one to explore specific incidences such as masking, stimming, and shutdowns) is more important than the provision of technical flexibilities in contract. This proposition is consistent with both stigma and intersectionality theories. It is through conversation, reflexive exchanges with “others” that we can reduce stigma and form a new social norm as part of a working alliance between employer and employee.70,71

An “accommodations process” that formally recognizes autistic needs, at the individual and personal level, is likely to form a stronger bond than broad brush flexible locations and/or timing policies for all. Further, inequities that come with additional marginalizing identities can be transparently discussed in a 1-2-1 accommodation conversation. These allow for individuals to discuss intersectional concerns of covert and overt discrimination, as well as hopes and ambitions that might not be stereotypically associated with the identity of the employee.

With accommodations levied at the organizational level, they will target the disability only, and miss the intersection of disability with race, gender, sexuality, and more. At the individual level, more personalization and nuance allow for hidden inequities to become visible and resolvable.

The organizational psychology concept of “job crafting” is relevant here.72 Job crafting involves a holistic and dynamic approach to balancing the competing needs of the environment, task demands, and employee capability to individualize the job role and work performance. Job crafting is reported to increase levels of engagement and productivity,73 and the adoption of its principles with human resources protocols may provide a more systemic approach to accommodating larger numbers of autistic employees.

Job crafting is part of a wider theoretical framework on motivation and performance, which dates back to the mid-20th century. Using Herzberg's motivational theory,74 our data suggest that the presence of accommodations is a “hygiene factor” rather than a motivator—that is, the absence of accommodations is demotivating, but the presence of accommodations does not motivate; rather, the presence of interactive communication and being “listened to” motivates.

To support accommodation practice, future research requires sophisticated and ideally multi-method designs to understand not just what should be provided, but also how it should be determined and mutually agreed. Until more evidence from intervention studies is available, we recommend providing access to personalized accommodations and flexible Human Resources protocols.

Study limitations

We relied on a cross-sectional design and correlational descriptive data, running the risk of common method bias. The sample was somewhat female biased; a known problem in online surveys and in Autism research in particular.75 We recognize the representation of privilege in the sample with a trend toward highly educated autistic people from well-resourced backgrounds, which may have been perpetuated by our sampling strategy using media fora used by professional populations.

The survey also failed to attract high numbers of responses from Black and Brown communities, almost none from indigenous communities and a few from non-western countries, meaning that results should be interpreted cautiously. We were encouraged by an increase in non-White responses following a call for support from our research centre assistants and Advisory Board, which signposts the importance of research team membership from a wider diverse background. We acknowledge that blending all non-White groups into one cohort is problematic given the need to understand nuance between ethnicities and encourage research colleagues to explore this aspect in more depth.

We observed a potential mismatch in applying neuro-normative measures to an autistic population, though this was mitigated to some degree by our rigorous approach of employing a focus group, adapting instructions and items, and analyzing certain items separately.

In summary, the results from this survey in relation to race, nationality, and autism-specific roles can only cautiously be interpreted as potential trends to stimulate replication and further analysis, rather than generalizable data from which we can make inferences and conclusions. However, we contend that there are more general points to be made here about (1) the difficulties of capturing truly intersectional data within a vulnerable population and (2) the limits of White and western-led institutions to understand experiences within the GEM. By transparently reporting the stark disparities in representation, we hope to sound a call to action for the wider field.

We recommend that journals and institutions support the endeavors of Asian, African, and South American researchers to generate a more balanced body of knowledge in the autism field, indeed in science. The high levels of representation in the sample of gender identification, transgender status, SES, and diverse sexual orientation make these findings comparatively more reliable. Further studies with increased representation from minoritized autistic voices are recommended to enable more sophisticated path analysis and reduce sampling bias.

Conclusions

We found support for stigma and intersectional theory, as our basic understanding of autism at work is masking differences for autistic people with multiple identities regarding labor force participation and experience at work. We have collected preliminary evidence of a compound intersectional adverse impact for gender identification, gender status, and race/ethnicity in a highly educated autistic population where women and ethnic minorities are disadvantaged.

We frame our findings as opening an agenda for future research and more nuanced consideration of EDIB. We recommend further exploration of experience at work comparing autistic and non-autistic samples with particular reference to not only the effectiveness, but also the interpersonal facilitation of tailored accommodation and support. Our work appears to indicate that it is not structural adjustments that make the difference, but the perception that someone cares.

We hope that our work might initiate a program of synthesizing research with robust conceptual/theoretical frameworks from organizational psychology; a discipline with more than a hundred years of experience in developing employer practices.76

Implications for theory and research

We frame our exploratory survey findings as opening up a fertile agenda for research and practice. In time, we hope that future studies will develop more sophisticated longitudinal designs to test the effectiveness of targeted employment initiatives through an intersectionality lens. A viable next step is to build our observations concerning the links between stigma from marginalizing characteristics and workplace inclusion into a testable, theoretically grounded set of intervention studies. For example, we might predict (1) the success of awareness training as an intervention that leads to less masking, via (2) the reduction of stigma thus (3) addressing the limitations of non-autistic colleagues in positively appraising the communication and intention of autistic people.77

If this proposition were true, we would further expect awareness training to lead to increased deployment of reasonable accommodations and reduced absence/turnover of autistic staff. Longitudinal studies using empirical third-party data to evaluate the success/limitations of accommodations and interventions are long overdue.21

The lack of participation from individuals participating in autism-specific roles makes it hard to draw confident conclusions from the crosstabs data in Table 3. We urge fellow researchers to explore in more detail the potential limitations and benefits of these initiatives. Our descriptive data point toward concerns that are not represented in public discourse, which is almost entirely positive.35,78 Replication with larger samples and cooperation from autism-specific hiring organizations is essential to address any systemic biases in relevant initiatives as a potential solution to low labor force participation for autistic people.

Given that no study can include all measures of interest without risking participant fatigue, we did not collect data on whether and how the organizations (for those in employment) implemented any wider EDIB programs or other inclusion activities. Neurodiversity research is never context or power blind, and future research would do well to consider such aspects.

Specific implications for EDIB programs

The implication of this study for those working in autism hiring roles and EDIB are to urgently improve reporting on industry-wide race, gender, and geographic participation and to begin addressing disparities. In addition, practitioners and researchers need to collaborate in systematic and robust research to explore potential concerns regarding disclosure within autism-specific hiring.

We found that the perception of being accommodated was strongly related to experiences of inclusion and authenticity, highlighting a need for a more person- and support-focused rather than compliance-focused approach to dispensing accommodations at work.79 Useful avenues for further enquiry therein include reducing the need to avoid stigma by masking, for example, via provision of individual job-role crafting72 as a way to help autistic people shape what is best for them without abdicating responsibility for the wider EDIB agenda.

Practitioners are encouraged toward more systemic, universal design types of inclusion40 and cautioned against tokenism. This study has provided a nuanced, complex report of the intersectional experiences of autistic people at work; we contend that improving both labor force participation and career progression/fulfilment will involve theoretically grounded research collaborations in applied settings.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of Genius Within Community Interest Company (CIC) in funding this research and members of the Advisory Board of the Centre for Neurodiversity at Work, at Birkbeck, University of London, for their guidance on prioritizing this investigation as an essential building block of our research agenda as well as their oversight and support in generating responses. The authors acknowledge the work of Marcia Brissett-Bailey, Whitney Iles, Judy Singer, and Tumi Sotire in sharing the survey link widely in their networks.

Authorship Confirmation Statement

N.D. and A.M. were involved in the conception and design of the work. N.D., with research assistant support from U.W., was involved in data collection, analysis, and interpretation. N.D. and A.M. were involved in drafting and critical revision of the article, and all approved the final version to be published.

Author Disclosure Statement

N.D. and U.W. are employed by Genius Within CIC,* a non-profit organization based in the United Kingdom, which is paid to provide advice and guidance on Autism Hiring programs and is also contracted by the UK government to provide support for unemployed people and those leaving prison. This work was conducted as part of wider project to gather evidence on how to conduct services ethically and effectively. The other author has no conflicts of interest.

Funding Information

This research was funded by Genius Within CIC, as part of their legal obligation to reinvest any operating profits into services that support their community. Genius Within is majority owned and led by neurodivergent thinkers, including autistic people.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Appendix SA1

CIC, which is considered non-profit under the laws of England and Wales, requiring all registered companies to return a minimum of 65% of profits to services for their community.

References

- 1. Zeidan J, Fombonne E, Scorah J, et al. Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Autism Res. 2022;15(5):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thye MD, Bednarz HM, Herringshaw AJ, et al. The impact of atypical sensory processing on social impairments in autism spectrum disorder. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2018;29:151–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Isaksson J, Neufeld J, Bölte S. What's the link between theory of mind and other cognitive abilities—A co-twin control design of neurodevelopmental disorders. Front Psychol. 2021;12:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Song P, Zha M. The prevalence of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health. 2021;11:04009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cassidy S, Hannant P, Tavassoli T, et al. Dyspraxia and autistic traits in adults with and without autism spectrum conditions. Mol Autism. 2016;7(48):1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kalyva E, Kyriazi M, Vargiami E, et al. A review of co-occurrence of autism spectrum disorder and Tourette syndrome. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2016;24:39–51. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Howlin P, Moss P. Adults with autism spectrum disorders. Can J Psychiatry. 2012;57(5):275–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Charlton J. Nothing About Us Without Us: Disability Oppression and Empowerment. Berkley, CA: University of California Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Smith M. The time for talking is over now is the time to act: Race in the workplace. London; 2017. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/594336/race-in-workplace-mcgregor-smith-review.pdf Accessed December 1, 2021.

- 10. Putz C, Sparkes I, Foubert J. Outcomes for disabled people in the UK: 2020. Off Natl Stat. 2021:1–27. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/disability/articles/outcomesfordisabledpeopleintheuk/2020 Accessed December 1, 2021.

- 11. Lockwood Estrin G, Milner V, Spain D, et al. Barriers to autism spectrum disorder diagnosis for young women and girls: A systematic review. Rev J Autism Dev Disord. 2020;8:454–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Johnson TD, Joshi A. Dark clouds or silver linings? A stigma threat perspective on the implications of an autism diagnosis for workplace well-being. J Appl Psychol. 2016;101(3):430–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Roman-Urrestarazu A, Van Kessel R, Allison C, Matthews FE, Brayne C, Baron-Cohen S. Association of race/ethnicity and social disadvantage with autism prevalence in 7 million school children in England. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(6):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Adak B, Halder S. Systematic review on prevalence for autism spectrum disorder with respect to gender and socio-economic status. J Ment Disord Treat. 2017;3(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Heylens G, Aspeslagh L, Dierickx J, et al. The co-occurrence of gender dysphoria and autism spectrum disorder in adults: An analysis of cross-sectional and clinical chart data. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48(6):2217–2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kallitsounaki A, Williams D. Mentalising moderates the link between autism traits and current gender dysphoric features in primarily non-autistic, cisgender individuals. J Autism Dev Disord. 2020;50(11):4148–4157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Warrier V, Greenberg DM, Weir E, et al. Elevated rates of autism, other neurodevelopmental and psychiatric diagnoses, and autistic traits in transgender and gender-diverse individuals. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):3959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Marmot M, Atkinson T, Bell J, et al. Fair Society, Healthy Lives. London: Institute of Health Equity; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jacob A, Scott M, Falkmer M, Falkmer T. The costs and benefits of employing an adult with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wehman P, Brooke V, Brooke AM, et al. Employment for adults with autism spectrum disorders: A retrospective review of a customized employment approach. Res Dev Disabil. 2016;53–54:61–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ellenberg J, Paff M, Harrison A, et al. Disparities based on race, ethnicity, and socio-economic status over the transition to adulthood among adolescents and young adults on the autistic spectrum: A systematic review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21(32):1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Grandin T, Duffy K. Developing Talents for Individuals with Asperger Syndrom and High-Functioning Autism. 2nd ed. Shawnee Mission, KS: Autism Publishing Co; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23. United Nations. United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD). Geneva: United Nations; 2006;1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 24. United Kingdom Parliament. Equality Act. United Kingdom; 2010. www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/introduction Accessed December 1, 2021.

- 25. South African Department of Labour. Employment Equity Act. Arbeit + R. 1998;(12):448–450. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Department of Education, Skills and Employment (DESE). Disability Discrimination Act. Australia: Canberra, Australia: Department of Education, Skills and Employment; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Office for National Statistics. Disability and employment, UK. London; 2019. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/disability/bulletins/disabilityandemploymentuk/2019#:~:text=Over 4.2 million disabled people,employed was nearly 2.9 million Accessed December 1, 2021.