Abstract

Suicide is a worldwide health crisis. We aimed to identify genetic risk variants associated with suicide death and suicidal behavior. Meta-analysis for suicide death was performed using 3765 cases from Utah and matching 6572 controls of European ancestry. Meta-analysis for suicidal behavior using data across five cohorts (n = 8315 cases and 256,478 psychiatric or populational controls of European ancestry) was also performed. One locus in neuroligin 1 (NLGN1) passing the genome-wide significance threshold for suicide death was identified (top SNP rs73182688, with p = 5.48 × 10−8 before and p = 4.55 × 10−8 after mtCOJO analysis conditioning on MDD to remove genetic effects on suicide mediated by MDD). Conditioning on suicidal attempts did not significantly change the association strength (p = 6.02 × 10−8), suggesting suicide death specificity. NLGN1 encodes a member of a family of neuronal cell surface proteins. Members of this family act as splice site-specific ligands for beta-neurexins and may be involved in synaptogenesis. The NRXN-NLGN pathway was previously implicated in suicide, autism, and schizophrenia. We additionally identified ROBO2 and ZNF28 associations with suicidal behavior in the meta-analysis across five cohorts in gene-based association analysis using MAGMA. Lastly, we replicated two loci including variants near SOX5 and LOC101928519 associated with suicidal attempts identified in the ISGC and MVP meta-analysis using the independent FinnGen samples. Suicide death and suicidal behavior showed positive genetic correlations with depression, schizophrenia, pain, and suicidal attempt, and negative genetic correlation with educational attainment. These correlations remained significant after conditioning on depression, suggesting pleiotropic effects among these traits. Bidirectional generalized summary-data-based Mendelian randomization analysis suggests that genetic risk for the suicidal attempt and suicide death are both bi-directionally causal for MDD.

Subject terms: Psychiatric disorders, Neuroscience, Genetics

Introduction

Suicide is a worldwide public health crisis, accounting for close to 800,000 deaths per year. In 2019, suicide was the tenth leading cause of death [1], the second leading cause of death among individuals between the ages of 10 and 34, and the fourth leading cause of death among individuals between the ages of 35 and 54 in the United States [2]. The rate of suicidal behavior (SB) has climbed steadily over the past two decades [3–6]. Suicide outcomes encompass a range of behaviors. Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) is defined as the intentional destruction of body tissue without suicidal intent [7]. Suicidal attempt (SA), defined as nonfatal self-injurious behavior with the intent to die, has been estimated to occur over 20 times more frequently than suicide death (SD) and is a major source of disability, reduced quality of life, social and economic burden. SB includes both SD and SA. There are intricate relationships between trauma exposure, NSSI, suicidal ideation, SA, and SD with common genetic contributions to trauma exposure and self-injurious thoughts and behaviors [8]. The observations of a higher frequency of SD and SA in monozygotic twins compared to dizygotic twins among suicide twin survivors but not non-suicide twin survivors suggest a genetic contribution to SB [9–14]. Family studies suggest a significant genetic contribution with heritability ranging from 30 to 55% to suicidal thoughts and behaviors [15, 16], while SAs have heritability estimates of 17–45%, even after controlling for psychiatric disorders [17].

Psychiatric disorders are nevertheless a major risk factor for SB, and shared heritability has been demonstrated via polygenic risk score (PRS) analysis and/or genetic correlation, with the strongest genetic correlation with depression (rg = 0.81) in the UK Biobank (UKB) [18, 19]. A prior SA is also a risk factor for SD and shared heritability is expected. However, based on conceptual and empirical differences (e.g., methods used, peak age, gender differences, frequency; CDC, 2016), nonfatal and fatal attempts are considered qualitatively distinct phenomena [20], suggesting genetic risk factors specific to SD may exist. Approximately two dozen genome-wide association studies (GWAS) using dichotomized traits of SA, SD, SB, and/or suicidal or self-harm ideation, or severity-based quantitative traits have been reported from both clinical and non-clinical population cohorts (civilians and military personnel) [18, 19, 21–42]. Most studies are from primarily European ancestry, but studies from other ancestries such as the Hispanic/Latino [27, 28, 41, 42], Asian [34, 41, 42], and African American [30, 41, 42] have started to emerge. Few genome-wide significant loci have been identified, and to date, replication has occurred for genome-wide significant association signals from chromosome 7, and variants near LDHB (European) and FAH (African American) [26, 30]. The largest meta-analysis to date between International Suicide Genetics Consortium (ISGC) and MVP identified 12 genome-wide significant loci [42]. Significant chip-based SNP heritability was estimated from several GWAS as well, with a heritability of 3.5% in the UKB (p = 7.12 × 10−4) [24], 4.6% in a Danish cohort (heritability was reduced to 1.9% after adjusting for mental disorders) [25], and 6.8% in the ISGC meta-analysis [26]. Gene-by-environment genome-wide interaction study was reported identifying PTSD as the main environment driver and a replicated male-associated genome-wide signal near CWC22 [43]. In addition, the contribution of rare variants by whole-exome sequencing was evaluated in UKB for the ever-attempted suicide and suicidal ideation phenotypes, and no significant finding was reported using the study-wide significance threshold of 2.18 × 10−11 [44]. Lastly, an increased global copy number variation (CNV) rate was reported for SA cases and a common CNV verified by qPCR assay near ZNF33B was reported in a small MDD cohort [45].

Since the recently published genomic analysis of SD data from a large population-ascertained cohort from Utah [22], we have genotyped another ~1200 samples from the original cohort and matched the cases with controls genotyped using a matching array platform. We additionally added three cohorts of subjects with a lifetime history of suicide attempts (FinnGen cohort and two Janssen clinical trial samples). We aim to further interrogate the genetic basis of suicidal death and SB and further understand the relationship between SA and suicidal death. We also would like to interrogate SD-specific and SA-specific genetic risk factors by performing conditional analysis on the most correlated psychiatric condition (depression), and SA (for the SD phenotype only). Lastly, we would like to further dissect the genetic architecture of SD, SA, and SB by understanding the shared genetic components and causal relationship between these traits and psychiatric/non-psychiatric traits.

Subjects and methods

Cohorts and sample ascertainment

A total of five cohorts were included in this study (Supplementary Method S1). Cohorts 1 and 2 consist of SD cases from the University of Utah [22] and matching controls from Janssen Research & Development, LLC and dbGaP. The Utah case samples were genotyped in three waves to date. Wave 1 and 2 samples were included in a previous report [22] except that the cases were matched to different sets of controls (Generation Scotland samples genotyped using OmniExpress and UK10K samples with whole-genome sequencing data). Compared to the previous SD GWAS (3413 cases) [22], a total of 3765 cases were included between cohorts 1 and 2, among which 2832 are common while 581 were unique in the previous SD GWAS analysis and 933 cases were unique in this study.

Cohorts 3 and 4 consist of suicide attempt cases and controls of European ancestry and were drawn from 12 clinical trial samples (NCT00044681, NCT00397033, NCT00412373, NCT00334126, NCT01193153, NCT02497287, NCT02422186, NCT01627782, NCT00253162, NCT00257075, NCT01515423, and NCT01529515) conducted by Janssen Research & Development, LLC. A subset of samples from cohorts 3 and 4 were included in a previous GWAS [26]. All Janssen clinical studies were approved by the appropriate institutional review boards or ethnic committees and have followed the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for all human investigations. In addition, informed consent has been obtained from the study participants involved.

Cohort 5 consists of SA cases and controls from FinnGen (https://www.finngen.fi/en/about). The SA analysis using FinnGen data release 6 (R6) from the FinnGen Study included 4098 individuals with SA history, defined as the presence of SA International Classification of Diseases codes, and 247,898 individuals without the relevant codes. The diagnosis codes used to define SA are provided in Supplementary Table S1. The detailed descriptions of these cohorts are available in Supplementary Method S1.

Cohorts 1 and 2 were used for SD GWAS, while all five cohorts were used for SB GWAS.

Genotyping and quality control

SD cases were genotyped using the Infinium PsychArray platform (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, Supplementary Method S2). Janssen’s SA cases and control samples were genotyped using either PsychArray, Human1M-Duo, or HumanOmni5Exome (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA). QC was performed initially by a local QC pipeline by genotyping batch, while the combined data were QC’ed again using RICOPILI [46] pipeline. Additional details on QC, principal component analysis (PCA), case–control matching, and imputation can be found in Supplementary Method S3.

Genome-wide association analysis

For the Utah SD association analysis, a linear mixed model (LMM) algorithm was used to test the association between variants and SD. For SD cohort 1, GWAS were performed using GEMMA [47], a computationally efficient yet suitable for smaller sample size, and an open-source LMM algorithm for GWAS modeling population stratification remaining after PCA by use of genomic relatedness matrices. For SD cohort 2, GWAS was performed using BOLT-LMM [48] that implements an extremely efficient Bayesian mixed-model analysis and is suitable in large cohorts (requiring N to be at least 5000). For the FinnGen cohort, GWAS was performed using the standard FinnGen pipeline that implements the LMM algorithm using SAIGE [49] that efficiently controls for case–control imbalance and sample relatedness. For the two Janssen SA cohorts, the standard logistic regression using PLINK as implemented in the RICOPILI pipeline was used. Meta-analysis was performed using METAL [50] (as implemented in the RICOPILI pipeline) for the two SD cohorts to identify genetic variants associated with SD and across all five cohorts to identify genetic variants associated with SB. Conventional genome-wide significance threshold 5 × 10−8 is used to declare study-wide significance. A list of variants with unadjusted p value less than 5 × 10−6 is also reported.

It is well known that substantial genetic liability is shared across psychiatric traits. To identify putative SD-specific genetic associations, multi-trait conditional and joint analysis (mtCOJO) [51] was further used to adjust using GWAS summary statistics for the effects of genetically correlated traits (MDD and SA). For MDD and SAs, the GWAS summary statistics from Howard et al. [52], without 23andMe cohort and Mullin et al. [26] without SD cohort (Utah wave 1 and 2 data and two other cohorts with predominant SD cases) were used (Supplementary Method S4), respectively. Likewise, to identify SB-specific genetic associations, mtCOJO was also used to adjust for the effects of MDD to identify putative SB-specific genetic associations. mtCOJO analyses were performed using Genome-wide Complex Trait Analysis version 1.93.2 beta [53].

Variant annotation and multi-marker analysis of genomic annotation (MAGMA) gene- and gene-set-based analysis

Variant clumping to identify independent genomic locus and annotation was performed using FUMA [54]. In addition to single-marker-based GWAS, gene-based analyses followed by pathway enrichment analysis were computed using MAGMA [55] based on GWAS meta-analysis summary statistics. SNPs were mapped to 18,927 protein-coding genes. Genome-wide significance was defined at p = 0.05/18,927 = 2.64 × 10−6. The MAGMA analyses were performed using FUMA [54].

Replication of genome-wide significant loci from ISGC and Million Veteran Program suicidal attempt meta-analysis

Among the five cohorts used in this study, the FinnGen cohort was completely independent of the cohorts included in the ISGC and Million Veteran Program meta-analysis [42]. We used the results from the FinnGen cohort to replicate the 12 genome-wide significant loci reported in the meta-analysis between ISGC and MVP cohorts [42]. SNPs with an association p value less than 0.05/12~0.00417 were considered replicated. Other cross-references/replication attempts of published results are also described in Supplementary Method S5.

Polygenic risk score association with suicide death

PRSs derived from 92 summary statistics (for non-unique traits) were tested for association with SD for cohort 1 and cohort 2, respectively, using PRSice-2 [56] with PT fixed at 1. Traits for calculating PRS included both psychiatric and somatic comorbidities, personality traits, and lifestyle factors. A full list of PRS derived is available in Supplementary Table S2 and Supplementary Method S6. Association p value less than 0.05/92~0.00054 was considered significant. The association results between cohort 1 and cohort 2 were compared for consistency. The results were also compared to the published PRS prediction or genetic correlation analysis results.

SNP heritability and genetic correlation estimations

The phenotypic variance explained by variants (both genotyped and imputed, mostly SNPs) (h2SNP) for each of the phenotype groups was estimated using association statistics as implemented in linkage disequilibrium (LD) Score regression [57]. Genetic correlations between a smaller list of selected traits (psychiatric and non-psychiatric as described in Supplementary Method S7) and SD and SB both before and after mtCOJO adjustments were also evaluated using LD Score regression. ISGC SA [26] (Supplementary Method S4) was also included as a reference for the calculation of genetic correlation. Details of summary statistics used for these traits together with population prevalence rate assumptions are available in Supplementary Table S3. Genetic correlation with a p value less than 0.05/18~0.0028 was considered significant as we accounted for the number of non-suicide traits for multiple testing corrections.

Generalized summary-data-based Mendelian randomization (GSMR)

GSMR [51] is a method to test for a putative causal association between a risk factor and a disease using summary-level data from GWAS. In this study, we test the relationship between MDD and SD/SA as well as the relationship between SA and SD.

Results

For the SD cohorts from the University of Utah and the SA cohort from FinnGen, psychiatry conditions were more prevalent among the cases as expected (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of cohorts used in this study.

| Cohorts 1 and 2 | Cohort 3 (PsychArray) | Cohort 4 (Omni1Mc) | Cohort 5 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affection status | Casesa | Cases | Controlsb | Cases | Controlsb | Cases | Controlsb |

| Case phenotype | Suicide death | Suicidal attempts | Suicidal attempts | Suicidal attempts | |||

| N | 3765 | 183 | 1199 | 268 | 780 | 4098 | 247,898 |

| Cases with linked demographic data, N | 3426 | 183 | 1199 | 268 | 780 | 4098 | 247,898 |

| Cases with linked demographic data and EHR, N | 2981 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 4098 | 247,898 |

| Demographic information | |||||||

| Female, n (%) | 743 (21.7) | 95 (51.9) | 612 (51.0) | 142 (53.0) | 435 (55.8) | 3525 (86.0) | 138,666 (55.9) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 41.0 (17.2) | 47.1 (13.0) | 44.3 (14.2) | 41.2 (11.8) | 43.6 (12.5) | 56.6 (17.8) | 59.6 (17.7) |

| Clinical characteristics, n (%) | |||||||

| Bipolar disorder | 321 (10.8) | 91 (34.0) | 223 (28.6) | 257 (6.3) | 3428 (1.4) | ||

| Broad bipolar spectrum illness | 450 (15.1) | 295 (7.2) | 4130 (1.7) | ||||

| MDD | 927 (31.1) | 87 (47.3) | 492 (41.0) | 93 (34.7) | 355 (45.5) | 1020 (24.9) | 20,691 (8.3) |

| Broad depression | 1568 (52.6) | 1141 (27.8) | 24,379 (9.8) | ||||

| Anxiety | 747 (25.1) | 844 (20.6) | 17,576 (7.1) | ||||

| Schizophrenia | 117 (3.9) | 53 (28.8) | 579 (48.3) | 20 (7.5) | 87 (11.2) | 222 (5.4) | 2634 (1.1) |

| Psychosis | 295 (9.9) | 673 (16.4) | 13,185 (5.3) | ||||

| Pain | 1636 (54.9) | 40 (1.0) | 1012 (0.4) | ||||

| Sleep problems | 822 (27.6) | 328 (8.0) | 9312 (3.8) | ||||

| SUD | 1513 (50.8) | 739 (18.0) | 13,895 (5.6) | ||||

| SLE | 283 (9.5) | – | – | ||||

| Suicidal ideation | 560 (18.8) | – | – | ||||

| Adult maltreatment | 7 (0.2) | – | – | ||||

| Childhood maltreatment | 15 (0.5) | – | – | ||||

| Any mental health | 2142 (71.9) | 2378 (58.0) | 73,576 (29.7) | ||||

| Diabetes | 278 (9.3) | ||||||

| Asthma | 359 (12.0) | ||||||

| Schizoaffective disorder | 43 (23.5) | 128 (10.7) | 64 (23.9) | 115 4.7) | |||

Specifically, cohorts 1 and 2 are used for suicide death (SD) GWAS meta-analysis, and cohorts 1–5 are used for suicidal behavior (SB) GWAS meta-analysis.

aThe controls for cohort 1 are Coriell controls screened for psychiatric medical and family history (n = 804), while the controls for cohort 2 are IAMDGC controls not screened for suicide attempt (n = 5768).

bThe controls for cohorts 3 and 4 are psychiatric controls within the same studies.

cUsing the overlapping markers between Omni1M-Duo and Omni5M.

Genome-wide association (SNP-level and gene-level associations)

For the expanded SD GWAS meta-analysis using 3765 cases and 6572 populational controls genotyped (Table 1 and Supplementary Method S1), one locus in neuroligin 1 (NLGN1) passing genome-wide significance threshold for SD meta-analysis compared to the general population was identified (top SNP rs73182688, with p = 5.48 × 10−8 before and p = 4.55 × 10−8 after mtCOJO analysis conditioning on MDD summary statistics (Table 2); Manhattan plots in Fig. 1A and Supplementary Fig. S3A, QQ-plots in Supplementary Fig. S2A, B). Conditioning on SA summary statistics (p = 6.02 × 10−8, Manhattan plot in Supplementary Fig. S3B, QQ-plot in Supplementary Fig. S2C) or both MDD and SA summary statistics (p = 4.70 × 10−8) did not significantly change the association strength, suggesting that this is an SD-specific genetic risk locus. NLGN1 encodes a member of a family of neuronal cell surface proteins. Members of this family act as splice site-specific ligands for beta-neurexins and the NLGN1 protein is involved in the formation and remodeling of central nervous system synapses. Additional variants associated with SD with suggestive association p value less than 5 × 10−6 and the annotated genes based on positional, eQTL, or chromatin interaction mapping are listed in Supplementary Tables S4 and S5, respectively. In addition, our study replicated the genome-wide significant finding in rs116955121 [19] that was associated with suicidal ideation and attempt in UKB (p = 0.0003 in our SD GWAS meta-analysis, Supplementary Table S6). Additional replication attempts were described in Supplementary Text S1 and Supplementary Tables S7 and S8. Among the 22 implicated genes associated with SD, 6 were significantly differentially expressed in postmortem brain samples of schizophrenia, autism, and/or bipolar disorder (p value less than 0.05/22~0.0023) based on the analysis from the PsychENCODE Consortium (Supplementary Table S9). Of particular interest, EIF4G2 were consistently downregulated in both schizophrenia (p = 1.88 × 10−5) and bipolar disorder (p = 0.001).

Table 2.

Top genome-wide association signals.

| Analysis | CHR | SNP | BP | A1 | A2 | FRQ_A | FRQ_U | INFO | OR | SE | p | Direction | Nca | Nco |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicide death | 3 | rs73182688 | 173,612,201 | A | G | 0.885 | 0.863 | 0.603 | 1.06855 | 0.0122 | 5.48E–08 | ++ | 3765 | 6572 |

| Suicide death | MDD | 4.55E–08 | |||||||||||||

| Suicide death | attempt | 6.02E–08 | |||||||||||||

| Suicide death | MDD and attempt | 4.70E–08 | |||||||||||||

| Suicidal behavior | 3 | rs7649370 | 77,175,484 | A | G | 0.645 | 0.677 | 0.989 | 1.03448 | 0.0065 | 1.51E–07 | +++++ | 8315 | 256,478 |

| Suicidal behavior | MDD | 2.89E–07 | |||||||||||||

| Suicidal behavior | 3 | rs6782116 | 77,176,032 | C | T | 0.651 | 0.68 | 0.986 | 1.03386 | 0.0065 | 2.92E–07 | ––––– | 8315 | 256,478 |

| Suicidal behavior | MDD | 4.38E–07 |

A1: Allele 1 (odds ratios calculated with respect to this allele), A2: Allele 2, INFO: quality of imputation for the SNP.

BP base-pair position in reference to hg19, CHR chromosome, FRQ_A minor allele frequency (A1) in cases, FRQ_U minor allele frequency (A1) in controls, OR odds ratio, SE standard error, SNP single-nucleotide polymorphism.

SNP in bold reached genome-wide significance threshold in either the main analysis or mtCOJO conditional analysis.

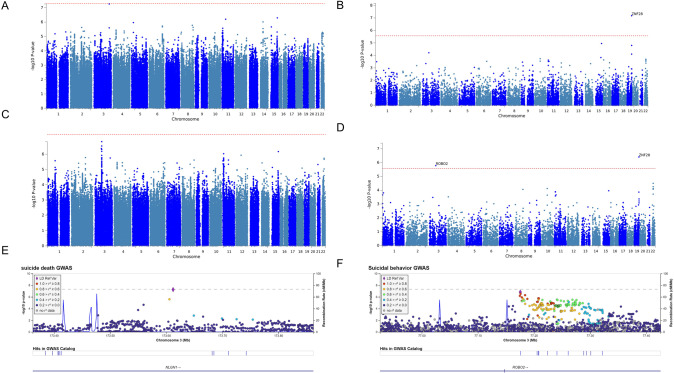

Fig. 1. Genome-wide significant association signals.

Manhattan plots for suicide death GWAS meta-analysis: SNP-level (A), gene-level (B); and suicidal behavior GWAS meta-analysis: SNP-level (C), gene-level (D). Regional plot for NLGN1 (E); regional plot for ROBO2 (F). The dotted line indicates a genome-wide significance threshold of 5 × 10–8. For the regional association plot generated by LocusZoom [95], SNPs in genomic risk loci are color-coded as a function of their r2 to the index SNP in the locus, as follows: red (r2 > 0.8), orange (r2 > 0.6), green (r2 > 0.4) and light blue (r2 > 0.2). SNPs that are not in LD with the index SNP (with r2 ≤ 0.2) are dark blue, while SNPs with missing LD information are shown in gray.

Gene-based association using MAGMA additionally identified ZNF28 to be associated with SD (Manhattan plot in Fig. 1B, QQ-plot in Supplementary Fig. S2D, regional plot in Fig. 1E), and the association did not weaken when adjusting for correlated traits including MDD and SA (Manhattan plots in Supplementary Fig. S3C, D, QQ-plots in Supplementary Fig. S2E, F). Additional regional plots for suggestive association signals from the SD GWAS are available in Supplementary Fig. S4. The top 10 genes with suggestive evidence associated with SD are also listed in Supplementary Table S10.

No variant associated with SB passed the genome-wide significance threshold in the meta-analysis across five cohorts (n = 8315 cases and 256,478 psychiatric or populational controls, Table 1) before (Manhattan plot in Fig. 1C, QQ-plot in Supplementary Fig. S2G) and after (Manhattan plot in Supplementary Fig. S3E, QQ-plot in Supplementary Fig. S2H) applying the mtCOJO adjustment for MDD. Additional variants associated with SB with suggestive association p value less than 5 × 10−6 and the corresponding implicated genes are listed in Supplementary Tables S11 and S12 with regional plots available in Supplementary Fig. S5. Genes with differential gene expression evidence from PsychENCODE are also provided in Supplementary Table S13. SB “replication” attempt of ISGC results is described in Supplementary Text S1 and Supplementary Tables S14 and S15. Among the 12 genome-wide significant loci identified from the ISGC and Million Veteran Program SA meta-analysis, two associations with SA (equivalent to our SB endpoint in this study) were replicated accounting for 12 independent tests in the FinnGen cohort with consistent directionality (rs17485141 [p = 0.003, OR = 0.92] near SRY-box transcription factor 5 (SOX5) and rs62404522 near LOC101928519 [p = 0.001, OR = 1.12]. There were two other associations trended toward nominal associations (rs2503185 [p = 0.08] near PDE4B and rs7131627 near DRD2 [p = 0.08]) with consistent directionality. The other nominal association (rs3791129 [p = 0.04] near SLC6A9) was in opposite directionality (Table 3).

Table 3.

Replication results for genome-wide significant loci identified in the ISGC and MVP meta-analysis.

| CHR | SNP | BP | A1 | A2 | FRQ_A_4098 | FRQ_U_247898 | INFO | OR | SE | p | Nearest gene (distance to index SNP in kb) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | rs3791129 | 44,480,093 | A | G | 0.7582 | 0.7503 | 0.99 | 1.06 | 0.03 | 0.041 | SLC6A9 (0.0) |

| 1 | rs2503185 | 66,461,401 | G | A | 0.4231 | 0.4347 | 1 | 0.96 | 0.02 | 0.078 | PDE4B (0.0) |

| 11 | rs7131627 | 113,299,829 | A | G | 0.4986 | 0.5107 | 1 | 0.96 | 0.02 | 0.075 | DRD2 (0.0) |

| 12 | rs17485141 | 24,213,634 | T | C | 0.2325 | 0.248 | 1 | 0.92 | 0.03 | 0.003 | SOX5 (0.0) |

| 13 | rs9525171 | 96,908,223 | G | C | 0.4996 | 0.5072 | 1 | 0.97 | 0.02 | 0.259 | HS6ST3 (0.0) |

| 14 | rs850261 | 57,346,423 | G | A | 0.4344 | 0.4274 | 1 | 1.04 | 0.02 | 0.114 | OTX2-AS1 (0.0) |

| 15 | rs17514846 | 91,416,550 | A | C | 0.3905 | 0.3936 | 1 | 0.99 | 0.02 | 0.59 | FURIN (0.0) |

| 22 | rs2284000 | 37,053,338 | G | C | 0.2922 | 0.2902 | 0.99 | 1 | 0.03 | 0.853 | CACNG2 (0.0) |

| 3 | rs7649709 | 173,129,819 | A | C | 0.3291 | 0.3269 | 0.96 | 1 | 0.02 | 0.965 | NLGN1 (0.0) |

| 6 | rs62404522 | 19,307,114 | C | T | 0.1416 | 0.1301 | 1 | 1.12 | 0.03 | 0.001 | LOC101928519 (–76.4) |

| 6 | rs35869525 | 26,946,687 | T | C | 0.04866 | 0.05079 | 1 | 0.98 | 0.05 | 0.642 | MHC |

| 7 | rs62474683 | 115,020,725 | G | A | 0.4203 | 0.4283 | 1 | 0.97 | 0.02 | 0.172 | LINC01392 (–149.3) |

A1: Allele 1 (odds ratios calculated with respect to this allele), A2: Allele 2, INFO: quality of imputation for the SNP.

BP base-pair position in reference to hg19, CHR chromosome, FRQ_A minor allele frequency (A1) in cases, FRQ_U minor allele frequency (A1) in controls, OR odds ratio, SE standard error, SNP single-nucleotide polymorphism.

P-values in bold signify replication with consistent directional effects.

Gene-based association using MAGMA additionally identified ROBO2 and ZNF28 passing study-wide significance as being associated with SB (Manhattan plot in Fig. 1D, QQ-plot in Supplementary Fig. S2I), this association did not weaken significantly when adjusting for MDD using mtCOJO, suggesting that the association is SB-specific (Manhattan plot in Supplementary Fig. S3F, QQ-plot in Supplementary Fig. S2J). It is noteworthy that the study-wide significant gene-based association for ROBO2 corresponds to the most significant suggestive association in the SNP-based meta-analysis. ROBO2 encodes a transmembrane receptor for the slit homolog 2 protein and functions in axon guidance and cell migration. The top 10 genes with suggestive evidence associated with SB are listed in Supplementary Table S10. There are also a few genes with suggestive evidence in multiple analyses, such as ROBO2, which had suggestive evidence associated with SD (p = 6.21 × 10−5 before adjusting with depression, p = 1.58 × 10−4 after adjusting with depression, p = 1.46 × 10−4 after conditioning on SA). The same is true for a few other brain-expressed genes such as LIMK2, NRBF2, NRG1, and ZNF710 (Supplementary Table S10). Among the 18 implicated genes across all traits from the gene-based analysis, three of them were significantly differentially expressed in postmortem brain samples of schizophrenia, autism, and/or bipolar disorder (p value less than 0.05/18~0.00278) based on the analysis from PsychENCODE Consortium (Supplementary Table S16). Of particular interest, LIMK2 were consistently upregulated in ASD (p = 0.0003), schizophrenia (p = 3.18 × 10−9), and bipolar disorder (p = 0.0003).

MAGMA gene-set analysis

MAGMA gene-set enrichment analysis revealed that MHC class Ib receptor activity pathway was enriched among variants associated with SD (p = 1.82 × 10−7, Bonferroni-corrected p value = 2.82 × 10–3). This gene-set enrichment was driven by gene-based association results from leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor B1 (LILRB1, p = 0.003) in chromosome 19 and CD160 (p = 0.07) in chromosome 1. There was suggestive enrichment for immune-related pathways, such as natural killer cell cytokine production (p = 7.68 × 10–6), positive regulation of interferon-gamma secretion (p = 3.39 × 10–5), immunological memory processing (p = 5.76 × 10–5), and negative regulation of viral-induced cytoplasmic pattern recognition receptor signaling pathway (p = 9.10 × 10–5) (Supplementary Table S17).

Polygenic risk score association with suicide death

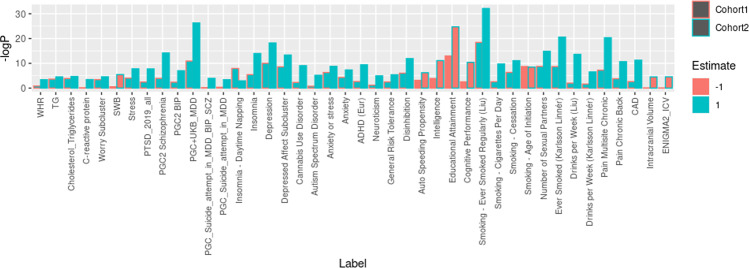

Among the 92 PRSs derived from psychiatric, personality, somatic comorbidity, and lifestyle traits, 22 and 41 were associated with SD status in cohort 1 and cohort 2, respectively (Fig. 2), among which 21 were common. In both cohorts, PRSs derived from depression, anxiety, stress, insomnia, schizophrenia, and pain were positively associated while smoking-related traits and education attainment/intelligence were negatively associated with SD. Cohort 2 was much larger in sample size and revealed additional positive PRS associations derived from bipolar disorder, PTSD, general anxiety disorder (GAD), ASD, ADHD, substance use disorder (SUD), neuroticism, cholesterol/triglycerides, and negative associations derived from subjective well-being, intracranial volume, and cognitive performance. Many of these traits including depression, anxiety, pain, neuroticism, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and PTSD were previously reported to be genetically correlated with suicidality [19, 26]. A complete list of associations passing multiple test corrections is available in Supplementary Table S18.

Fig. 2. Polygenic risk score association with suicide death.

P values plotted are association p value for the respective PRS and suicide death status in cohorts 1 and 2, respectively. Bar plots filled in red denote a negative association coefficient, while green ones denote a positive association coefficient. ADHD attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, ASD autism spectrum disorder, BIP bipolar disorder, CAD coronary artery disease, ICV intracranial volume, MDD major depressive disorder, PTSD posttraumatic stress disorder, SCZ schizophrenia, SWB subjective well-being, TG triglycerides, WHR waist-to-hip ratio.

Genetic heritability of suicidal death, suicidal attempt, and suicidal behavior and genetic correlation with other traits

Total Liability scale h2SNP for SD (from this study) and SA (from ISGC) was 5.02% and 5.45%, respectively. Conditioning on MDD, SA, or both reduced the h2SNP for SD to 3.93%, 4.6%, and 3.65%, respectively. Total Liability scale h2SNP for SB (from this study) was 2.98%, while conditioning on MDD reduced it to 2.19%.

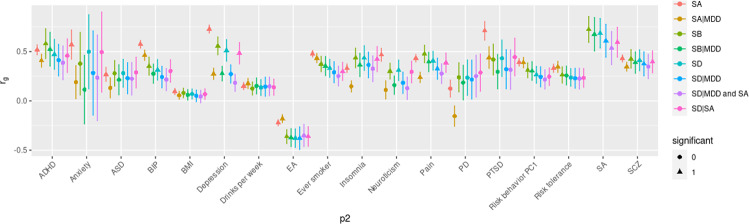

The genetic correlation between SD and SA was 0.69 (p = 4.16 × 10–6). Both traits were correlated with psychiatric trait depression (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table S18). Specially, the genetic correlation between SD and MDD was 0.51 (SE = 0.11, p = 2.92 × 10–6), while the genetic correlation between SA (ISGC excluding SD cohorts) and MDD was 0.73 (SE = 0.04, p = 1.41 × 10–72). Likewise, the genetic correlation between SB and MDD was 0.56 (SE = 0.09, p = 6.84 × 10–10). After conditioning on depression, the correlations with depression were reduced (for SD|MDD, rg = 0.27, p = 0.003; for SB|MDD, rg = 0.28, p = 0.0002).

Fig. 3. Genetic correlation between suicide death, suicidal attempt, and suicidal behavior (p1), and selected psychiatric/non-psychiatry traits (p2).

Triangle points indicate genetic correlations that passed the Bonferroni-corrected significance threshold (p < 2.78 × 10–3). Error bars represent the standard error. ADHD attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, ASD autism spectrum disorder, BIP bipolar disorder, MDD major depressive disorder, PTSD posttraumatic stress disorder, SA suicidal attempt, SB suicidal behavior, SB|MDD SB results after conditioning on MDD, SCZ schizophrenia, SD suicide death, SD|MDD SD results after conditioning on MDD, SD|SA SD results after conditioning on SA, SD|MDD and SA SD results after conditioning on MDD and SA.

SA (based on ISGC summary statistics excluding SD cohorts) was used as a positive control in this study and the detailed results are provided in Supplementary Text S1. SB was correlated with SA (rg = 0.72, p = 3.09 × 10–8), pain (rg = 0.48, p = 8.15 × 10–8), educational attainment (rg = –0.36, p = 2.51 × 10–7), ever smoker (rg = 0.37, p = 1.41 × 10–6), schizophrenia (rg = 0.43, p = 6.06 × 10–6), and insomnia (rg = 0.44, p = 1.28 × 10–5). SD was also associated with pain and educational attainment. To examine whether these genetic correlations were mediated by depression, rg was estimated with the same traits using the SB|MDD, and SD|MDD results. For SB and SD, genetic correlations with ASD, anxiety, PTSD were not significant before conditioning, while the genetic correlations with ADHD, insomnia (for SD|MDD only), risk tolerance (for SB|MDD only), bipolar disorder, and neuroticism (for both SB|MDD, and SD|MDD) became nonsignificant after conditioning. After conditioning on both MDD and SA, most of the genetic correlations with SD were nonsignificant except for the negative correlation with EA (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table S19).

Generalized summary-data-based Mendelian randomization (GSMR)

Bidirectional GSMR analysis suggests that the genetic risk for the SA and SD are both bidirectional causal with the genetic risk for MDD (Supplementary Fig. S6). Specifically, we found significant bidirectional causal relationships in SNP effect sizes for MDD loci in the genetic risk for SAs (pGSMR = 8.30 × 10–63) and SA loci in MDD (pGSMR = 2.65 × 10–9). In addition, we also found significant bidirectional causal relationships in SNP effect sizes for MDD loci in the genetic risk for SD (pGSMR = 8.2 × 10–5) and SD loci in MDD (pGSMR = 0.05).

Discussion

Using a total of 3765 SD cases and 6572 populational controls, we identified one locus in neuroligin 1 (NLGN1) with genome-wide significance. The top SNP is rs73182688, with p = 5.48 × 10–8 before and p = 4.55 × 10–8 after mtCOJO analysis conditioning on depression; Howard et al., using summary statistics without the 23andMe cohort). Conditioning on the SA (ISGC summary statistics [26] without Utah and two other SD cohorts) did not significantly change the association strength (p = 6.02 × 10–8), suggesting this is a locus with SD specificity. Gene-based association using MAGMA additionally identified ROBO2 and ZNF28 as being associated with SB in the meta-analysis across five cohorts consisting of 8315 cases and 256,478 psychiatric or populational controls, among which ZNF28 was also associated with SD. The gene-set enrichment analysis identified the MHC Class Ib receptor activity pathway as being significantly associated with SD. Using a completely independent sample set from FinnGen, we replicated two genome-wide significant findings from the ISGC and MVP meta-analysis including variants near SOX5.

Among the genes near the replicated variants associated with SA, SOX5 was previously associated with schizophrenia, depression, neuroticism, chronotype, chronic back pain, C-reactive protein levels, cortical thickness, and surface area [52, 58–63], and is among a panel of genes contributing to the bidirectional causal effect of neuroticism on MDD [64]. The variant associated with depression (rs78337797) and the variant associated with SA (rs17485141) are in weak LD with each other (r2 = 0.13, D’ = 0.75), suggesting allelic heterogeneity and pleotropic effect of this locus. SOX5 encodes a transcription factor important for embryogenesis and cell fate determination with the expression level highest during fetal development (Supplementary Fig. S7). A full list of reported genome-wide significant associations annotated to SOX5 is provided in Supplementary Table S20.

Among the genes associated with SD, NLGN1 encodes a member of a family of postsynaptic neuronal cell surface proteins. Members of this family act as splice site-specific ligands for presynaptic β-neurexins and are involved in the formation and remodeling of central nervous system synapses [65, 66]. Another variant in NLGN1 (weak LD with the variant reported herein) is associated with SA in the ISGC and MVP meta-analysis, suggesting allelic heterogeneity in this gene. Neurexin 1 variants were previously implicated as risk factors for SD [67, 68]. The top associated variant rs73182688 in NLGN1 in this study is nominally associated with BMI (p = 0.0006), depression (p = 0.004 in FinnGen R5), and personality disorder (p = 0.004 in FinnGen R5) (Supplementary Table S21). Other variants (SNVs and CNVs) in NLGN1 and/or other family members NLGN3 and NLGN4 were previously associated with PTSD, autism, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and depression [69–75]. The rs6779753 variant in NLGN1 associated with PTSD as well as with the intermediate phenotypes of higher startle response and greater hemodynamic responses (assessed using functional MRI) of the amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex to fearful face stimuli was not in LD with the variant identified herein. In our study, rs6779753 was only suggestively associated with SD (p = 0.06). NLGN1 was also implicated in a preclinical model of depression [76]. In addition, presynaptic neurexins and cytoplasm partners such as SHANK also have been implicated in autism, schizophrenia, and mental retardation [73, 77–83]. Overall, there is substantial genetic evidence on the NRXN-NLGN pathway in suicide and other psychiatric conditions.

ROBO2 and ZNF28 were associated with SB in our study. Variants in ROBO2 were previously reported to be associated with circadian phenotypes such as self-identification as a “morning person” and chronotype [62], smoking initiation [84], and highest math classes taken [85], all reaching genome-wide significance threshold. These genome-wide significant variants are in LD with the top variant rs7649370 from this study (r2 > 0.86). ROBO2 was also implicated in schizophrenia, and psychopathic tendencies, although a subsequent study replicated the emotionally reactive, impulsive aspects of conduct disorder, but not the concurrent risk for psychopathy [86–88]. ZNF28, on the other hand, was not previously associated with psychiatric disorders. A few genes with gene-level suggestive association evidence across multiple analyses were discussed in Supplementary Text S3.

Consistent with the previous SD GWAS [22], elevated PRS for disinhibition, MDD, schizophrenia, and ASD in SD cases were observed in this study. The previously reported PRS associations for child IQ (p = 0.03 in cohort 1 and p = 0.95 in cohort 2) and loneliness (p = 0.04 and p = 0.06) were nominal in this study. This study however uncovered additional evidence of elevated PRS in anxiety, insomnia, stress, smoking, alcohol use, and pain among SD cases, consistent with epidemiology evidence, known risk factors, and warning signs noted by several suicides- or health-focused organizations, a previous meta-analysis on predictors of suicidal thought and behaviors, and/or previous reported genetic correlations [20, 26, 89–92]. Reduced PRS for education attainment and intelligence was associated with SD. Cohort 2 revealed additional positive PRS associations for bipolar disorder, PTSD, GAD, ASD, ADHD, SUD, neuroticism, cholesterol/triglycerides, and negative associations for subjective well-being, intracranial volume, and cognitive performance. While the last SD GWAS did not reveal significant genetic correlation results [22], this study revealed a significant genetic correlation between pain and educational attainment, consistent with the PRS association findings. We had expected to identify a causal relationship from SAs to SD. However, the absence of a significant causal relationship in the current study may reflect limitations in statistical power for the GWAS for both SA and SD summary statistics, as few genome-wide significant findings have been reported to date. However, the non-significance of this relationship may alternatively reflect the observation that the majority of people who die by suicide die on their first attempt [93, 94]. Thus, a large fraction of individuals who completed suicides would be expected to not have a prior attempt. Conversely, among patients who require medical attention for a suicide attempt only a relatively small fraction die on the first attempt [94].

The study has a few limitations. Even though this is one of the largest GWAS analyses for SD, the effective sample size is still more modest than previous SD GWAS or SA GWAS reported by ISGC. Even though we genotyped an additional ~1200 SD cases, the net increase in SD case sample size was >300 after case–control matching, while the control sample size was smaller compared to the previous SD GWAS. However, this SD GWAS is the first well-powered GWAS to leverage matching arrays across cases and controls, which we believe is an important strength. Secondly, we prioritized depression and SAs for conditional analysis. There are certainly other psychiatric conditions that warranted such a test and therefore the conditional test is not exhaustive. In addition, the summary statistics from Howard et al. are likely to be powerful enough for conditional analysis given that 102 independent variants were discovered, while the summary statistics from the ISGC analysis may not be powerful enough as the genome-wide significant loci are just beginning to be unveiled. Thirdly, even though we tried to provide replication evidence for suggestive association findings from ISGC, the samples used in this study partially overlapped with the samples in ISGC, and therefore are not completely independent. The Finngen replication of ISGC and MVP meta-analysis results on the other hand are completely independent. The GSMR analysis is just the beginning to explore the intricate relationship between these traits. The selection of SNPs used a relaxed p value threshold simply due to the limited power of available GWAS summary statistics and this certainly benefits from future growth in sample size.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (HC, grant number R01MH099134; ARD, grant number K01MH093731); the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (ARD and AB), the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation (ARD and AAS, NARSAD Young Investigator Awards); the University of Utah EDGE Scholar Program (ARD); the Clark Tanner Foundation (HC). Partial support for all datasets housed within the Utah Population Data Base is provided by the Huntsman Cancer Institute (HCI), http://www.huntsmancancer.org/, and the HCI Cancer Center Support grant, P30-CA-42014 from the NIH. Genotyping was performed by U of Utah Genomics Core (wave 1 of Utah cases) and by Illumina, Inc (all Janssen samples and waves 2 and 3 of Utah cases) with support from Janssen Research & Development, LLC. This work was also supported by research funding from Janssen Research & Development, LLC to the University of Utah.

We want to acknowledge the participants and investigators of the FinnGen study. The FinnGen project is funded by two grants from Business Finland (HUS 4685/31/2016 and UH 4386/31/2016) and the following industry partners: AbbVie Inc., AstraZeneca UK Ltd, Biogen MA Inc., Bristol Myers Squibb (and Celgene Corporation & Celgene International II Sàrl), Genentech Inc., Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp, Pfizer Inc., GlaxoSmithKline Intellectual Property Development Ltd., Sanofi US Services Inc., Maze Therapeutics Inc., Janssen Biotech Inc, Novartis AG, and Boehringer Ingelheim. Following biobanks are acknowledged for delivering biobank samples to FinnGen: Auria Biobank (www.auria.fi/biopankki), THL Biobank (www.thl.fi/biobank), Helsinki Biobank (www.helsinginbiopankki.fi), Biobank Borealis of Northern Finland (https://www.ppshp.fi/Tutkimus-ja-opetus/Biopankki/Pages/Biobank-Borealis-briefly-in-English.aspx), Finnish Clinical Biobank Tampere (www.tays.fi/en-US/Research_and_development/Finnish_Clinical_Biobank_Tampere), Biobank of Eastern Finland (www.ita-suomenbiopankki.fi/en), Central Finland Biobank (www.ksshp.fi/fi-FI/Potilaalle/Biopankki), Finnish Red Cross Blood Service Biobank (www.veripalvelu.fi/verenluovutus/biopankkitoiminta), and Terveystalo Biobank (www.terveystalo.com/fi/Yritystietoa/Terveystalo-Biopankki/Biopankki/). All Finnish Biobanks are members of the BBMRI.fi infrastructure (www.bbmri.fi). Finnish Biobank Cooperative – FINBB (https://finbb.fi/) is the coordinator of BBMRI-ERIC operations in Finland. The Finnish biobank data can be accessed through the Fingenious® services (https://site.fingenious.fi/en/) managed by FINBB.

Control data for suicide death cohort 2 were obtained from dbGaP (phs001039: International Age-Related Macular Degeneration Genomics Consortium (IAMDGC) AMD Exome Chip experiment). All contributing sites and additional funding information are acknowledged in this publication: Fritsche et al. (2016) Nature Genetics 48 134–143, (doi: 10.1038/ng.3448); The International AMD Genomics consortium’s web page is http://eaglep.case.edu/iamdgc_web/, and additional information is available on http://csg.sph.umich.edu/abecasis/public/amd2015/.

Author contributions

HC collected the University of Utah suicide death samples and generated wave 1 genotype data. QSL generated the waves 2 and 3 suicide death genotyping data and the Janssen genotyping data. AP is the Scientific Director of the FinnGen study and is responsible for the overall conduct and output of the FinnGen Scientific Plan. QSL performed the data analysis except that AAS performed the PRS analysis. QSL wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and all authors reviewed, provided comments, and approved the manuscript.

Code availability

PLINK 1.07 https://zzz.bwh.harvard.edu/plink/

PLINK 1.9 https://www.cog-genomics.org/plink/

RICOPILI https://sites.google.com/a/broadinstitute.org/ricopili

GEMMA https://github.com/genetics-statistics/GEMMA

BOLT https://alkesgroup.broadinstitute.org/BOLT-LMM/BOLT-LMM_manual.html

SAIGE https://github.com/weizhouUMICH/SAIGE

PRSice-2 https://www.prsice.info/

LDSC https://github.com/bulik/ldsc

GCTA https://yanglab.westlake.edu.cn/software/gcta/#Overview

Competing interests

QSL, SG, CMC, and WCD are employed by Janssen Research & Development, LLC, and own stocks and options of Johnson & Johnson. All other authors have no financial relationships with commercial interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

A full list of members and their affiliations appears in the Supplementary Information.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41380-022-01828-9.

References

- 1.Kochanek KD, Xu JQ, Arias E. Mortality in the United States, 2019. NCHS Data Brief, no 395. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2020. [PubMed]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. WISQARS. Ten leading causes of death by age group.

- 3.Hedegaard H, Curtin SC, Warner M. Increase in suicide mortality in the United States, 1999–2018. NCHS Data Brief, no 362. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2020. [PubMed]

- 4.Pettrone K, Curtin SC. Urban–rural differences in suicide rates, by sex and three leading methods: United States, 2000–2018. NCHS Data Brief, no 373. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2020. [PubMed]

- 5.Curtin SC, Heron M. Death rates due to suicide and homicide among persons aged 10–24: United States, 2000–2017. NCHS Data Brief, no 352. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2019. [PubMed]

- 6.Stone DM, Simon TR, Fowler KA, Kegler SR, Yuan K, Holland KM, et al. Vital signs: trends in state suicide rates—United States, 1999–2016 and circumstances contributing to suicide—27 states, 2015. Morbidity Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:617–24. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6722a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nock MK, Favazza AR. Understanding nonsuicidal self-injury: origins, assessment, and treatment. In: Nock MK, editor. Understanding nonsuicidal self-injury: origins, assessment, and treatment. American Psychological Association; 2009. p. 9–18.

- 8.Richmond-Rakerd LS, Trull TJ, Gizer IR, McLaughlin K, Scheiderer EM, Nelson EC, et al. Common genetic contributions to high-risk trauma exposure and self-injurious thoughts and behaviors. Psychological Med. 2019;49:421–30. doi: 10.1017/S0033291718001034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roy A, Segal NL. Suicidal behavior in twins: a replication. J Affect Disord. 2001;66:71–74. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00275-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roy A, Segal NL, Centerwall BS, Robinette CD. Suicide in twins. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:29–32. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810250031003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baldessarini RJ, Hennen J. Genetics of suicide: an overview. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2004;12:1–13. doi: 10.1080/714858479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaquero-Lorenzo C, Vasquez MA. Suicide: genetics and heritability. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2020;46:63–78. doi: 10.1007/7854_2020_161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roy A, Segal NL, Sarchiapone M. Attempted suicide among living co-twins of twin suicide victims. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1075–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.7.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Segal NL. Suicidal behaviors in surviving monozygotic and dizygotic co-twins: is the nature of the co-twin’s cause of death a factor? Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2009;39:569–75. doi: 10.1521/suli.2009.39.6.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Statham DJ, Heath AC, Madden PA, Bucholz KK, Bierut L, Dinwiddie SH, et al. Suicidal behaviour: an epidemiological and genetic study. Psychological Med. 1998;28:839–55. doi: 10.1017/S0033291798006916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voracek M, Loibl LM. Genetics of suicide: a systematic review of twin studies. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2007;119:463–75. doi: 10.1007/s00508-007-0823-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mann JJ, Arango VA, Avenevoli S, Brent DA, Champagne FA, Clayton P, et al. Candidate endophenotypes for genetic studies of suicidal behavior. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:556–63. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruderfer DM, Walsh CG, Aguirre MW, Tanigawa Y, Ribeiro JD, Franklin JC, et al. Significant shared heritability underlies suicide attempt and clinically predicted probability of attempting suicide. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:2422–30. doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0326-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strawbridge RJ, Ward J, Ferguson A, Graham N, Shaw RJ, Cullen B, et al. Identification of novel genome-wide associations for suicidality in UK Biobank, genetic correlation with psychiatric disorders and polygenic association with completed suicide. EBioMedicine. 2019;41:517–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franklin JC, Ribeiro JD, Fox KR, Bentley KH, Kleiman EM, Huang X, et al. Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: a meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychol Bull. 2017;143:187–232. doi: 10.1037/bul0000084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sokolowski M, Wasserman J, Wasserman D. Genome-wide association studies of suicidal behaviors: a review. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24:1567–77. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Docherty AR, Shabalin AA, DiBlasi E, Monson E, Mullins N, Adkins DE, et al. Genome-wide association study of suicide death and polygenic prediction of clinical antecedents. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177:917–27. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.19101025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mullins N, Bigdeli TB, Borglum AD, Coleman JRI, Demontis D, Mehta D, et al. GWAS of suicide attempt in psychiatric disorders and association with major depression polygenic risk scores. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176:651–60. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.18080957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mullins N, Perroud N, Uher R, Butler AW, Cohen-Woods S, Rivera M, et al. Genetic relationships between suicide attempts, suicidal ideation and major psychiatric disorders: a genome-wide association and polygenic scoring study. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2014;165B:428–37. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erlangsen A, Appadurai V, Wang Y, Turecki G, Mors O, Werge T, et al. Genetics of suicide attempts in individuals with and without mental disorders: a population-based genome-wide association study. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:2410–21. doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0218-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mullins N, Kang J, Campos AI, Coleman JRI, Edwards AC, Galfalvy H, et al. Dissecting the shared genetic architecture of suicide attempt, psychiatric disorders, and known risk factors. Biol Psychiatry. 2022;91:313–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Shen H, Gelaye B, Huang H, Rondon MB, Sanchez S, Duncan LE. Polygenic prediction and GWAS of depression, PTSD, and suicidal ideation/self-harm in a Peruvian cohort. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020;45:1595–602. doi: 10.1038/s41386-020-0603-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gonzalez-Castro TB, Martinez-Magana JJ, Tovilla-Zarate CA, Juarez-Rojop IE, Sarmiento E, Genis-Mendoza AD, et al. Gene-level genome-wide association analysis of suicide attempt, a preliminary study in a psychiatric Mexican population. Mol Genet Genom Med. 2019;7:e983. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kimbrel NA, Garrett ME, Dennis MF, VA Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center Workgroup. Hauser MA, Ashley-Koch AE, et al. A genome-wide association study of suicide attempts and suicidal ideation in U.S. military veterans. Psychiatry Res. 2018;269:64–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levey DF, Polimanti R, Cheng Z, Zhou H, Nunez YZ, Jain S, et al. Genetic associations with suicide attempt severity and genetic overlap with major depression. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9:22. doi: 10.1038/s41398-018-0340-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perlis RH, Huang J, Purcell S, Fava M, Rush AJ, Sullivan PF, et al. Genome-wide association study of suicide attempts in mood disorder patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:1499–507. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10040541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Willour VL, Seifuddin F, Mahon PB, Jancic D, Pirooznia M, Steele J, et al. A genome-wide association study of attempted suicide. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17:433–44. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schosser A, Butler AW, Ising M, Perroud N, Uher R, Ng MY, et al. Genomewide association scan of suicidal thoughts and behaviour in major depression. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20690. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Otsuka I, Akiyama M, Shirakawa O, Okazaki S, Momozawa Y, Kamatani Y, et al. Genome-wide association studies identify polygenic effects for completed suicide in the Japanese population. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44:2119–24. doi: 10.1038/s41386-019-0506-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Galfalvy H, Haghighi F, Hodgkinson C, Goldman D, Oquendo MA, Burke A, et al. A genome-wide association study of suicidal behavior. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2015;168:557–63. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stein MB, Ware EB, Mitchell C, Chen CY, Borja S, Cai T, et al. Genomewide association studies of suicide attempts in US soldiers. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2017;174:786–97. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zai CC, Goncalves VF, Tiwari AK, Gagliano SA, Hosang G, de Luca V, et al. A genome-wide association study of suicide severity scores in bipolar disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;65:23–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thorp JG, Marees AT, Ong JS, An J, MacGregor S, Derks EM. Genetic heterogeneity in self-reported depressive symptoms identified through genetic analyses of the PHQ-9. Psychological Med. 2020;50:2385–96. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719002526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zai CC, Fabbri C, Hosang GM, Zhang RS, Koyama E, de Luca V, et al. Genome-wide association study of suicidal behaviour severity in mood disorders. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2021;22:722–31. doi: 10.1080/15622975.2021.1907711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lybech LKM, Calabro M, Briuglia S, Drago A, Crisafulli C. Suicide related phenotypes in a bipolar sample: genetic underpinnings. Genes (Basel). 2021;12:1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Kimbrel NA, Ashley-Koch AE, Qin XJ, Lindquist JH, Garrett ME, Dennis MF, et al. A genome-wide association study of suicide attempts in the million veterans program identifies evidence of pan-ancestry and ancestry-specific risk loci. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27:2264–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Docherty AR, Mullins N, Ashley-Koch AE, Qin XJ, Coleman J, Shabalin AA, et al. Genome-wide association study meta-analysis of suicide attempt in 43,871 cases identifies twelve genome-wide significant loci. medRxiv [Preprint] 2022.

- 43.Wendt FR, Pathak GA, Levey DF, Nunez YZ, Overstreet C, Tyrrell C, et al. Sex-stratified gene-by-environment genome-wide interaction study of trauma, posttraumatic-stress, and suicidality. Neurobiol Stress. 2021;14:100309. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2021.100309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Backman JD, Li AH, Marcketta A, Sun D, Mbatchou J, Kessler MD, et al. Exome sequencing and analysis of 454,787 UK Biobank participants. Nature. 2021;599:628–34. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04103-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rao S, Shi M, Han X, Lam MHB, Chien WT, Zhou K, et al. Genome-wide copy number variation-, validation- and screening study implicates a new copy number polymorphism associated with suicide attempts in major depressive disorder. Gene. 2020;755:144901. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2020.144901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lam M, Awasthi S, Watson HJ, Goldstein J, Panagiotaropoulou G, Trubetskoy V, et al. RICOPILI: Rapid Imputation for COnsortias PIpeLIne. Bioinformatics. 2020;36:930–3. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou X, Stephens M. Genome-wide efficient mixed-model analysis for association studies. Nat Genet. 2012;44:821–4. doi: 10.1038/ng.2310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Loh PR, Tucker G, Bulik-Sullivan BK, Vilhjalmsson BJ, Finucane HK, Salem RM, et al. Efficient Bayesian mixed-model analysis increases association power in large cohorts. Nat Genet. 2015;47:284–90. doi: 10.1038/ng.3190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou W, Nielsen JB, Fritsche LG, Dey R, Gabrielsen ME, Wolford BN, et al. Efficiently controlling for case-control imbalance and sample relatedness in large-scale genetic association studies. Nat Genet. 2018;50:1335–41. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0184-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Willer CJ, Li Y, Abecasis GR. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2190–1. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhu Z, Zheng Z, Zhang F, Wu Y, Trzaskowski M, Maier R, et al. Causal associations between risk factors and common diseases inferred from GWAS summary data. Nat Commun. 2018;9:224. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02317-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Howard DM, Adams MJ, Clarke TK, Hafferty JD, Gibson J, Shirali M, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis of depression identifies 102 independent variants and highlights the importance of the prefrontal brain regions. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22:343–52. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0326-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. GCTA: a tool for Genome-wide Complex Trait Analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Watanabe K, Taskesen E, van Bochoven A, Posthuma D. Functional mapping and annotation of genetic associations with FUMA. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1826. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01261-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Leeuw CA, Mooij JM, Heskes T, Posthuma D. MAGMA: generalized gene-set analysis of GWAS data. PLoS Comput Biol. 2015;11:e1004219. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Choi SW, O’Reilly PF. PRSice-2: Polygenic Risk Score software for biobank-scale data. Gigascience. 2019;8:giz082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Bulik-Sullivan BK, Loh PR, Finucane HK, Ripke S, Yang J, Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, et al. LD Score regression distinguishes confounding from polygenicity in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2015;47:291–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.3211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pardinas AF, Holmans P, Pocklington AJ, Escott-Price V, Ripke S, Carrera N, et al. Common schizophrenia alleles are enriched in mutation-intolerant genes and in regions under strong background selection. Nat Genet. 2018;50:381–9. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0059-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Han X, Ong JS, An J, Hewitt AW, Gharahkhani P, MacGregor S. Using Mendelian randomization to evaluate the causal relationship between serum C-reactive protein levels and age-related macular degeneration. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020;35:139–46. doi: 10.1007/s10654-019-00598-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Suri P, Palmer MR, Tsepilov YA, Freidin MB, Boer CG, Yau MS, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis of 158,000 individuals of European ancestry identifies three loci associated with chronic back pain. PLoS Genet. 2018;14:e1007601. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shadrin AA, Kaufmann T, van der Meer D, Palmer CE, Makowski C, Loughnan R, et al. Vertex-wise multivariate genome-wide association study identifies 780 unique genetic loci associated with cortical morphology. NeuroImage. 2021;244:118603. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.118603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jones SE, Lane JM, Wood AR, van Hees VT, Tyrrell J, Beaumont RN, et al. Genome-wide association analyses of chronotype in 697,828 individuals provides insights into circadian rhythms. Nat Commun. 2019;10:343. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-08259-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nagel M, Jansen PR, Stringer S, Watanabe K, de Leeuw CA, Bryois J, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for neuroticism in 449,484 individuals identifies novel genetic loci and pathways. Nat Genet. 2018;50:920–7. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0151-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang F, Baranova A, Zhou C, Cao H, Chen J, Zhang X, et al. Causal influences of neuroticism on mental health and cardiovascular disease. Hum Genet. 2021;140:1267–81. doi: 10.1007/s00439-021-02288-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sudhof TC. Neuroligins and neurexins link synaptic function to cognitive disease. Nature. 2008;455:903–11. doi: 10.1038/nature07456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Krueger DD, Tuffy LP, Papadopoulos T, Brose N. The role of neurexins and neuroligins in the formation, maturation, and function of vertebrate synapses. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2012;22:412–22. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Coon H, Darlington TM, DiBlasi E, Callor WB, Ferris E, Fraser A, et al. Genome-wide significant regions in 43 Utah high-risk families implicate multiple genes involved in risk for completed suicide. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:3077–90. doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0282-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.William N, Reissner C, Sargent R, Darlington TM, DiBlasi E, Li QS, et al. Neurexin 1 variants as risk factors for suicide death. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26:7436–45. doi: 10.1038/s41380-021-01190-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kilaru V, Iyer SV, Almli LM, Stevens JS, Lori A, Jovanovic T, et al. Genome-wide gene-based analysis suggests an association between Neuroligin 1 (NLGN1) and post-traumatic stress disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6:e820. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jamain S, Quach H, Betancur C, Rastam M, Colineaux C, Gillberg IC, et al. Mutations of the X-linked genes encoding neuroligins NLGN3 and NLGN4 are associated with autism. Nat Genet. 2003;34:27–9. doi: 10.1038/ng1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Laumonnier F, Bonnet-Brilhault F, Gomot M, Blanc R, David A, Moizard MP, et al. X-linked mental retardation and autism are associated with a mutation in the NLGN4 gene, a member of the neuroligin family. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:552–7. doi: 10.1086/382137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yan J, Oliveira G, Coutinho A, Yang C, Feng J, Katz C, et al. Analysis of the neuroligin 3 and 4 genes in autism and other neuropsychiatric patients. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:329–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Glessner JT, Wang K, Cai G, Korvatska O, Kim CE, Wood S, et al. Autism genome-wide copy number variation reveals ubiquitin and neuronal genes. Nature. 2009;459:569–73. doi: 10.1038/nature07953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lewis CM, Ng MY, Butler AW, Cohen-Woods S, Uher R, Pirlo K, et al. Genome-wide association study of major recurrent depression in the U.K. population. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:949–57. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09091380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gazzellone MJ, Zarrei M, Burton CL, Walker S, Uddin M, Shaheen SM, et al. Uncovering obsessive-compulsive disorder risk genes in a pediatric cohort by high-resolution analysis of copy number variation. J Neurodev Disord. 2016;8:36. doi: 10.1186/s11689-016-9170-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Feng P, Akladious AA, Hu Y. Hippocampal and motor fronto-cortical neuroligin1 is increased in an animal model of depression. Psychiatry Res. 2016;243:210–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bena F, Bruno DL, Eriksson M, van Ravenswaaij-Arts C, Stark Z, Dijkhuizen T, et al. Molecular and clinical characterization of 25 individuals with exonic deletions of NRXN1 and comprehensive review of the literature. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2013;162B:388–403. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Coelewij L, Curtis D. Mini-review: update on the genetics of schizophrenia. Ann Hum Genet. 2018;82:239–43. doi: 10.1111/ahg.12259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sato D, Lionel AC, Leblond CS, Prasad A, Pinto D, Walker S, et al. SHANK1 deletions in males with autism spectrum disorder. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:879–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Leblond CS, Nava C, Polge A, Gauthier J, Huguet G, Lumbroso S, et al. Meta-analysis of SHANK mutations in autism spectrum disorders: a gradient of severity in cognitive impairments. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004580. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Durand CM, Betancur C, Boeckers TM, Bockmann J, Chaste P, Fauchereau F, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding the synaptic scaffolding protein SHANK3 are associated with autism spectrum disorders. Nat Genet. 2007;39:25–7. doi: 10.1038/ng1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Peca J, Feng G. Cellular and synaptic network defects in autism. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2012;22:866–72. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Berkel S, Marshall CR, Weiss B, Howe J, Roeth R, Moog U, et al. Mutations in the SHANK2 synaptic scaffolding gene in autism spectrum disorder and mental retardation. Nat Genet. 2010;42:489–91. doi: 10.1038/ng.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Liu M, Jiang Y, Wedow R, Li Y, Brazel DM, Chen F, et al. Association studies of up to 1.2 million individuals yield new insights into the genetic etiology of tobacco and alcohol use. Nat Genet. 2019;51:237–44. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0307-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lee JJ, Wedow R, Okbay A, Kong E, Maghzian O, Zacher M, et al. Gene discovery and polygenic prediction from a genome-wide association study of educational attainment in 1.1 million individuals. Nat Genet. 2018;50:1112–21. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0147-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Potkin SG, Macciardi F, Guffanti G, Fallon JH, Wang Q, Turner JA, et al. Identifying gene regulatory networks in schizophrenia. NeuroImage. 2010;53:839–47. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Viding E, Hanscombe KB, Curtis CJ, Davis OS, Meaburn EL, Plomin R. In search of genes associated with risk for psychopathic tendencies in children: a two-stage genome-wide association study of pooled DNA. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51:780–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dadds MR, Moul C, Cauchi A, Hawes DJ, Brennan J. Replication of a ROBO2 polymorphism associated with conduct problems but not psychopathic tendencies in children. Psychiatr Genet. 2013;23:251–4. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e3283650f83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Racine M. Chronic pain and suicide risk: a comprehensive review. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;87:269–80. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Vermeulen JM, Bolhuis K. The co-occurrence of smoking and suicide. Br J Psychiatry. 2020;217:708–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2020.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Harrison R, Munafo MR, Davey Smith G, Wootton RE. Examining the effect of smoking on suicidal ideation and attempts: triangulation of epidemiological approaches. Br J Psychiatry. 2020;217:701–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2020.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Poorolajal J, Darvishi N. Smoking and suicide: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0156348. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Isometsa ET, Lonnqvist JK. Suicide attempts preceding completed suicide. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:531–5. doi: 10.1192/bjp.173.6.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bostwick JM, Pabbati C, Geske JR, McKean AJ. Suicide attempt as a risk factor for completed suicide: even more lethal than we knew. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:1094–1100. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15070854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pruim RJ, Welch RP, Sanna S, Teslovich TM, Chines PS, Gliedt TP, et al. LocusZoom: regional visualization of genome-wide association scan results. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2336–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

PLINK 1.07 https://zzz.bwh.harvard.edu/plink/

PLINK 1.9 https://www.cog-genomics.org/plink/

RICOPILI https://sites.google.com/a/broadinstitute.org/ricopili

GEMMA https://github.com/genetics-statistics/GEMMA

BOLT https://alkesgroup.broadinstitute.org/BOLT-LMM/BOLT-LMM_manual.html

SAIGE https://github.com/weizhouUMICH/SAIGE

PRSice-2 https://www.prsice.info/

LDSC https://github.com/bulik/ldsc

GCTA https://yanglab.westlake.edu.cn/software/gcta/#Overview