Abstract

Malignancies of the peritoneal cavity are associated with a dismal prognosis. Systemic chemotherapy is the gold standard for patients with unresectable peritoneal disease, but its intraperitoneal effect is hampered by the peritoneal-plasma barrier. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy, which is administered repeatedly into the peritoneal cavity through a peritoneal implanted port, could provide a novel treatment modality for this patient population. This review provides a systematic overview of intraperitoneal used drugs, the performed clinical studies so far, and the complications of the peritoneal implemental ports. Several anticancer drugs have been studied for intraperitoneal application, with the taxanes paclitaxel and docetaxel as the most commonly used drug. Repeated intraperitoneal chemotherapy, mostly in combination with systemic chemotherapy, has shown promising results in Phase I and Phase II studies for several tumor types, such as gastric cancer, ovarian cancer, colorectal cancer, and pancreatic cancer. Two Phase III studies for intraperitoneal chemotherapy in gastric cancer have been performed so far, but the results regarding the superiority over standard systemic chemotherapy alone, are contradictory. Pressurized intraperitoneal administration, known as PIPAC, is an alternative way of administering intraperitoneal chemotherapy, and the first prospective studies have shown a tolerable safety profile. Although intraperitoneal chemotherapy might be a standard treatment option for patients with unresectable peritoneal disease, more Phase II and Phase III studies focusing on tolerability profiles, survival rates, and quality of life are warranted in order to establish optimal treatment schedules and to establish a potential role for intraperitoneal chemotherapy in the approach to unresectable peritoneal disease.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40265-022-01828-7.

Key Points

| Intraperitoneal chemotherapy is a safe treatment option for patients with unresectable peritoneal surface malignancies. |

| Several clinical studies in peritoneal metastases (e.g., gastric, ovarian, colorectal, and pancreatic cancer) suggest a survival benefit. |

| More studies are needed to compare its efficacy to current standard (systemic) treatments and to establish the optimal treatment regime with intraperitoneal and systemic chemotherapy. |

Introduction

Solid tumors, especially gastrointestinal malignancies, and tumors of the female reproductive systems may spread to the peritoneal cavity [1–3]. Peritoneal dissemination is associated with a dismal prognosis and substantial morbidity, and survival rates are shorter than those of patients with nonperitoneal metastases [4–6]. Symptoms such as bowel obstruction and ascites have a negative impact on quality of life and overall survival. For patients with unresectable peritoneal dissemination, systemic chemotherapy is the cornerstone of the treatment, but the 5-year survival rate does not exceed 10% [7, 8]. Therefore, more effective treatments are needed [9].

The intraperitoneal effect of systemic chemotherapy is reduced by the peritoneal-plasma barrier [10]. The peritoneal-plasma barrier is a complex, three-dimensional structure of peritoneal cells, interstitial tissue space and microvessels, which regulates intraperitoneal homeostasis [11]. Already in 1955, Weisberger et al investigated the use of chemotherapy directly infused into the peritoneal cavity [12]. In this way, higher intraperitoneal concentrations of drugs can be achieved compared to intravenous administration [13, 14]. Furthermore, the peritoneal-plasma barrier limits absorption into the systemic circulation, thereby reducing systemic toxicity and prolonging exposure of cancer cells to the drug [15–17].

Intraperitoneal chemotherapy can be delivered in different ways. Normothermic repeated intraperitoneal chemotherapy is repeated for several cycles at the outpatient clinic, typically combined with systemic chemotherapy. Pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC) is administered in repeated cycles during laparoscopy. On the other hand, hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) comprises a single heated intraperitoneal administration of anticancer drugs and is most often combined with cytoreductive surgery (CRS) [18]. Careful patient selection is essential to determine the optimal intraperitoneal treatment. Cytoreductive surgery-hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (CRS-HIPEC) has a curative intent but is only an option for a minority of fit patients with limited resectable peritoneal disease. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy and PIPAC can be applied as palliatively intended treatment to patients with more advanced peritoneal surface malignancies, with conversion surgery as potentially curative option in selected cases [19–21]. Compared to PIPAC, intraperitoneal chemotherapy is less demanding, because it does not require serial laparoscopy and can be administered in an outpatient setting, whereas PIPAC might lead to enhanced uptake and deeper penetration into the tumor due to the pressurized application.

Several reviews have focused on the use of intraperitoneal chemotherapy in combination with a resection [3, 22, 23]. This review gives an overview of intraperitoneal chemotherapy for unresectable peritoneal surface malignancies. We focus on the different intraperitoneally administered drugs and their pharmacokinetic characteristics and provide a systematic overview of the literature on the peritoneal implementable ports and clinical outcomes of intraperitoneal chemotherapy in the palliative setting.

Anticancer Drugs for Intraperitoneal Use

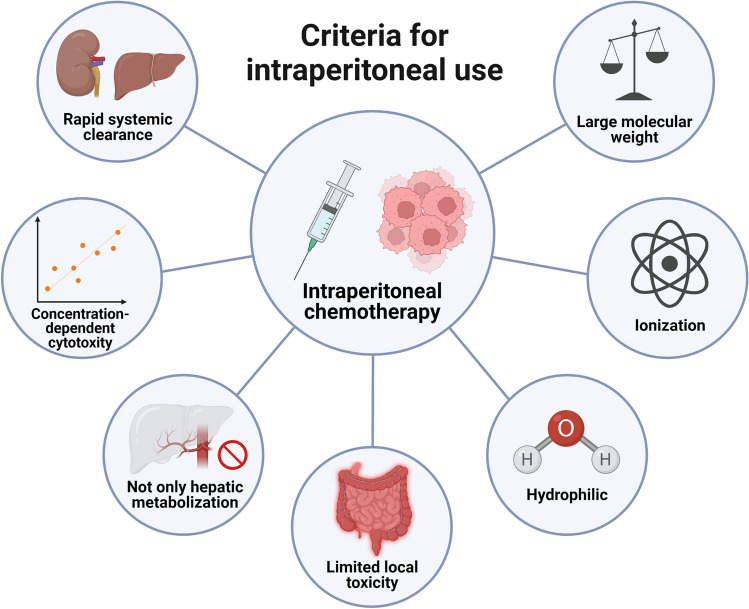

Figure 1 summarizes characteristics that are pivotal for a drug to be used intraperitoneally [21, 24]. First, it is important that absorption of the drug through the peritoneal-plasma barrier into the systemic circulation is limited, to prevent systemic toxicity. Physical properties such as relatively high molecular weight, hydrophilic characteristics, and ionization can impede the peritoneal barrier to clear the drug rapidly [25]. Moreover, the drug should have rapid renal or hepatic clearance. In that way, the pharmacokinetic advantage of intraperitoneal chemotherapy with high local exposure and low systemic exposure is optimal [21]. This pharmacokinetic advance is expressed as the area under the curve (AUC) ratio between intraperitoneal and systemic exposure, which varies from a factor 10 to a factor 1000 [26]. An optimal intraperitoneal drug has a maximum tolerated dose that is limited by systemic toxicity and not by local toxicity. High intraperitoneal dose escalation can thus be achieved, before the systemic concentration is similar to systemically administered chemotherapy [27]. Furthermore, the drug should not be dependent exclusively on the liver for metabolization into an active substance, because in that case local therapy has no advantage over intravenous therapy. Lastly, the drug must have concentration- or exposure-dependent cytotoxicity for the particular malignancy [21]. Table 1 presents an overview of important characteristics for intraperitoneal use per drug. Below, we will discuss literature on the most common intraperitoneally administered drugs for unresectable peritoneal surface malignancies.

Fig. 1.

Important characteristics of a drug when used for intraperitoneal chemotherapy

Table 1.

Characteristics of drugs used for intraperitoneal chemotherapy

| Drug | Molecular weight | Hydrophilic | AUC ratio | Thermal enhancement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taxanes | ||||

| Paclitaxel | 854 g/mol | No | 550–2300 | No |

| Docetaxel | 808 g/mol | No | 150–500 | No |

| Topoisomerase inhibitors | ||||

| Irinotecan | 587 g/mol | Yes | 38a | No |

| Mitoxantrone | 444 g/mol | No | 162–230 | No |

| Doxorubicin | 544 g/mol | Yes | 1109 | Yes |

| Platinum-based agents | ||||

| Cisplatin | 300 g/mol | Yes | 12–22 | Yes |

| Carboplatin | 371 g/mol | Yes | 15–20 | Yes |

| Oxaliplatin | 397 g/mol | Minimal | 16 | Yes |

| Antimetabolites | ||||

| 5-Fluorouracil | 130 g/mol | Minimal | 344 | Minimal |

| Gemcitabine | 263 g/mol | Yes | 847 | Yes |

| Pemetrexed | 427 g/mol | Yes | 70 | Yes |

aThe AUC-ratio for SN-38, the active metabolite of irinotecan, is approximately 4–15

Taxanes

Taxanes, such as paclitaxel and docetaxel, have been widely studied for intraperitoneal administration. Taxanes have a high molecular weight (854 g/mol for paclitaxel and 808 g/mol for docetaxel, respectively), which delays absorption from the peritoneal cavity [28, 29]. Intraperitoneal paclitaxel has been investigated in malignancies such as ovarian cancer, gastric cancer, peritoneal mesothelioma, and pancreatic cancer [30, 31]. The peritoneal to plasma AUC ratio for intraperitoneal paclitaxel is highly favorable, but substantial variability has been reported (AUC ratio 550 up to 2300) [32–36]. Intraperitoneal paclitaxel concentrations can be measured in the peritoneal cavity for several days after administration [37]. Repeated administration of intraperitoneal paclitaxel increases the penetration of paclitaxel in the cell layers of the tumor, which makes paclitaxel an interesting compound for repeated intraperitoneal use [38]. In recent years, intraperitoneal nab-paclitaxel (a solvent-free, albumin-bound form of paclitaxel) has been studied, which might enhance efficacy compared to conventional paclitaxel because of its increased water solubility. Just as for conventional paclitaxel, the favorable intraperitoneal pharmacokinetic profile applies for nab-paclitaxel [39]. Higher doses than anticipated could be achieved with nab-paclitaxel due to a lower frequency of abdominal pain than with conventional paclitaxel.

Intraperitoneal docetaxel has also been investigated in both ovarian cancer and gastric cancer. For docetaxel, the peritoneal to plasma AUC ratio was found to range between 150 and 500 [40, 41]. Docetaxel is also detectable in the abdominal fluid for several days, and therefore its potential as an intraperitoneal drug seems comparable to that of paclitaxel [40].

Topoisomerase Inhibitors

Both topoisomerase I and topoisomerase II inhibitors have been studied for intraperitoneal use. Irinotecan, the most commonly used topoisomerase I inhibitor, is favored for gastrointestinal malignancies and has a molecular weight of 587 g/mol. Irinotecan is a prodrug and requires conversion to its active metabolite SN-38 by carboxylesterases, of which CES1 is expressed in the liver and CES2 in various tissues such as the gastrointestinal mucosa [42]. Interestingly, biotransformation of irinotecan to SN-38 also occurs in the peritoneal cavity, suggesting the presence of carboxylesterases in the peritoneal fluid [43, 44]. The peritoneal to plasma AUC ratio of irinotecan is approximately 38, whereas the AUC ratio of SN-38 is estimated to be 4–15 [21, 45]. Due to the local biotransformation, irinotecan is a promising agent for intraperitoneal use in patients with (unresectable) peritoneal surface malignancies, especially from a gastrointestinal origin.

Topoisomerase II inhibitors like doxorubicin or mitoxantrone are less well studied for intraperitoneal use in non-resectable malignancies. Doxorubicin has an antitumor effect in e.g., breast cancer, soft tissue sarcoma and mesothelioma. It possesses beneficial pharmacokinetic characteristics for intraperitoneal use, such as a relatively high molecular weight (544 g/mol), high peritoneal/plasma AUC ratio (range of 162–230) and increasing intra-tumoral concentrations with increasing doses [29, 46]. However, most studies have focused on the application of intraperitoneal doxorubicin in the perioperative or intraoperative setting. Studies on intraperitoneal doxorubicin in unresectable malignancies are warranted. Meanwhile, doxorubicin as agent for PIPAC treatment has shown to be an interesting option due to high penetration levels when administered pressurized, but pharmacokinetic data are currently restricted to animal studies only [47]. Intraperitoneal mitoxantrone has been studied for the treatment of malignant ascites and showed a high peritoneal to plasma AUC ratio of 1109 with slow clearance from the peritoneal cavity [48, 49].

Platinum-Based Agents

Platinum compounds have also been commonly used for intraperitoneal application. These agents are less lipophilic and have a lower molecular weight than taxanes and topoisomerase inhibitors (cisplatin 300 g/mol, carboplatin 371 g/mol, and oxaliplatin 397 g/mol, respectively). Intraperitoneal cisplatin has been explored in the treatment of gastric cancer, ovarian cancer, and peritoneal mesothelioma [16, 50, 51]. The AUC ratio of cisplatin is less favorable than for many other drugs, ranging from 12 to 22 [21]. The cytotoxic effect of cisplatin is enhanced by heat with a factor 2.9 [52]. As a result of these characteristics, intraperitoneal cisplatin is particularly studied as HIPEC-treatment or in cases with low amounts of residual disease. The effect of repeated, normothermic intraperitoneal cisplatin for unresectable peritoneal disease is less obvious. Cisplatin is proposed as a potential agent for PIPAC treatment as well, but pharmacokinetic data are primarily based on in vitro or animal studies.

Intraperitoneal carboplatin has been studied in patients with ovarian cancer. Carboplatin has a slightly better pharmacokinetic profile than cisplatin, because of its higher molecular weight. The peritoneal to plasma AUC ratio of 15–20 is comparable with cisplatin [26]. However, data on the capacity of intraperitoneal carboplatin to penetrate peritoneal tumor cells are contradicting, questioning the use of intraperitoneal carboplatin so far [53, 54].

Oxaliplatin is effective against malignancies of the digestive and hepatobiliary tract. Intraperitoneal oxaliplatin has a relatively low peritoneal to plasma AUC ratio of 16, but has a rapid tissue penetration [26, 55]. Similar to cisplatin and carboplatin, intraperitoneal oxaliplatin is primarily studied as part of HIPEC since heat enhances its cytotoxic effect [56, 57] Therefore, platinum-based agents are theoretically less optimal for the use of repeated, normothermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy than taxanes or topo-isomerase inhibitors.

Antimetabolites

Antimetabolites are another option for intraperitoneal administration. 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) is used for a wide range of malignancies including those of the gastrointestinal tract and has a favorable peritoneal to plasma AUC ratio of approximately 344, but a relatively low molecular weight (130.1 g/mol) [58]. As 5-FU requires prolonged exposure to malignant cells, repeated intraperitoneal use might be an interesting option, but its value remains to be elucidated in prospective trials [21].

Gemcitabine and pemetrexed both have beneficial pharmacokinetics (AUC ratio of 847 and 70, respectively) [59, 60]. However, these agents have only been studied as heated adjuvant intraperitoneal chemotherapy combined with cytoreductive surgery. Their utility for intraperitoneal chemotherapy for unresectable disease is unknown.

Novel Intraperitoneal Agents

In recent years, agents other than chemotherapeutics have been studied for intraperitoneal use. These include, among others, nanoparticles, immunotherapy, or injectable hydrogels. No clinical studies with these agents have been performed in patients with unresectable peritoneal disease to date. A recent review summarized the novel methods of intraperitoneal drug delivery in post-debulking surgery ovarian cancer patients [61]. Micro- and nanosized particles consist of microspheres, most often loaded with paclitaxel, which enhance the retention time of the drug in the peritoneal cavity prolonging its cumulative exposure. The same rationale applies for hydrogel depots, which function as a carrier for cytotoxic agents [61]. These novel methods might enhance intraperitoneal drug delivery by prolonging its local exposure, but no clinical or pharmacokinetic studies in patients with unresectable peritoneal disease have been performed so far. Intraperitoneal immunotherapy (anti-PD-1 therapy) has been studied in vivo for intraperitoneal use [62, 63]. A cellular immune response has been shown in mouse models and might therefore have potential as an intraperitoneal drug, but as yet, no pharmacokinetic or clinical data are available demonstrating this rationale.

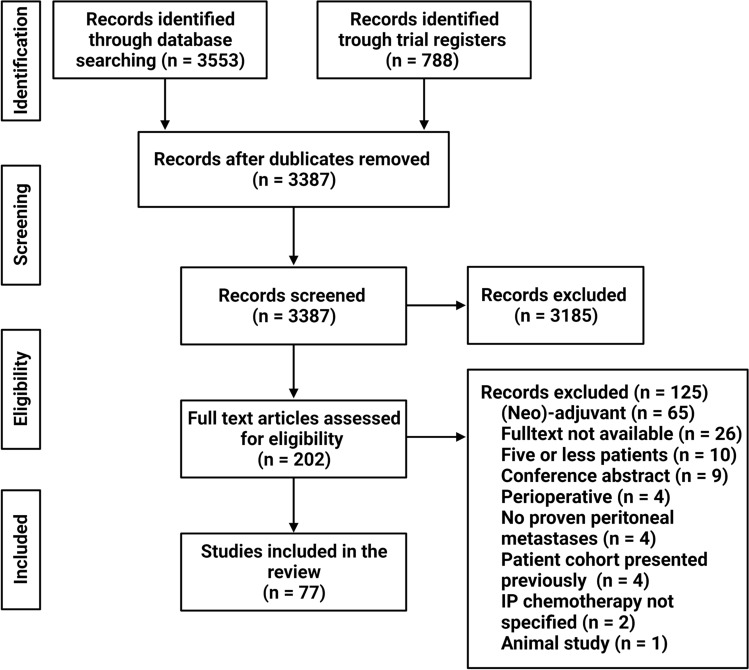

Literature Search Strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted in Embase, Medline, Web of Science and Cochrane for studies (English language only) about the clinical results of intraperitoneal chemotherapy and port complications for solid malignancies with unresectable peritoneal dissemination until the 27th of October 2022. Unresectable peritoneal disease was defined as peritoneal malignancy in patients who received intraperitoneal chemotherapy as a palliative treatment without curatively intended surgical resection. The detailed search strategy is presented in Supplementary Table 1. In addition, clinical trial databases such as ClinicalTrials.gov, EU Clinical Trial Register (www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/) and the Netherlands Trial Register (www.trialregister.nl) were searched to identify potentially relevant clinical trials. We included studies focusing on repeatedly administered intraperitoneal chemotherapy in patients with proven peritoneal solid malignancy (primary tumor or metastasis). We excluded studies in which intraperitoneal chemotherapy was part of a curatively intended surgical resection (e.g., perioperative or adjuvant), or case studies with 5 patients or less. Figure 2 shows the study selection process of the literature search. Seventy-seven included studies only describe repeated intraperitoneal normothermic chemotherapy or PIPAC for unresectable peritoneal surface malignancies. No studies investigating HIPEC as stand-alone treatment for unresectable peritoneal disease (i.e., without being part of a surgical resection) were identified. The level of evidence per study in all tables was individually assessed with regard to the Level of Evidence as per the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine [64].

Fig. 2.

Flowchart of study selection

Intraperitoneal Access Port

For patients with unresectable peritoneal disease, repeated intraperitoneal chemotherapy is the most commonly used method to administer chemotherapy intraperitoneally. With this method, intraperitoneal chemotherapy is given through a subcutaneous access port connected to an intraperitoneal catheter. The catheter is placed laparoscopically and the tip of the catheter is positioned in the pouch of Douglas. The patient is admitted on the day of surgery, and usually discharged on the same day. The port will remain in place during treatment and the drug is administered repeatedly at the outpatient clinic. Ascites, which is a common problem in patients with peritoneal metastasis, can be easily drained through the same port system. Currently, the standard port is the Port-A-Cath (PAC). The PAC is also commonly used as a central venous catheter. Alternative ways of port insertion have been investigated. For example, percutaneous image-guided port insertion is an interesting option, as it does not require general anesthesia [65]. However, development of new insertion techniques is still in an early stage, and surgical placement of intraperitoneal ports currently remains the gold standard.

Table 2 presents an overview of the reported port-related complications in Phase II and Phase III studies [66–81]. Moreover, two retrospective studies focused on the complications of intraperitoneal access. Yang et al found that in 249 gastric cancer patients who had received intraperitoneal chemotherapy through a PAC, 57 patients (22.9%) encountered port complications [82]. Most common complications were subcutaneous liquid accumulation (n = 24, 9.6% of all patients), infection (n = 16, 6.4%), and port rotation (n = 8, 3.2%). The severity of complications was graded from 1 to 4, in which grade 4 means stopping treatment and removing or replacing the port. Out of 57 complications, 18 were classified as grade 4 (32%). The most common grade 4 complication was port infection (n = 7), and ECOG performance status was statistically correlated with the grade of complication. Grade 3 complications, which were defined as complications in which an intervention (pharmacological or surgical) was required before the port could be used again, occurred in 7 patients. Remarkably, the high rate of subcutaneous liquid accumulation was not reported in the Phase II or III studies shown in Table 2. A second study with 131 gastric cancer patients found a similar rate of port complications (n = 27, 20.6%) [83]. Inflow obstruction (n = 10, 7.6%) and infection (n = 9, 6.9%) were the most observed complications. In this study, survival rates were not influenced by port complications. Taken together, complications of intraperitoneal ports are often manageable, but are related to clinical deterioration. In experienced hands, subcutaneous-placed ports are safe to use for intraperitoneal chemotherapy.

Table 2.

Port-related complications in Phase II and III studies with intraperitoneal chemotherapy for unresectable peritoneal metastases

| Author, year | N | Definition unres. Peritoneal disease | Patient population | IP therapy | Port complication rate | Observed complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase II studies | ||||||

| Chia et al., 2022 [66] | 44 | Pos. histology and/or cytology | Gastric cancer | Paclitaxel (40 mg/m2) at days 1 and 8 in 3-week cycles | 10/44 (23%) | Gr. 1 port leakage/infection, no intervention needed (n = 6), gr 3 would complications and re-siting of port (n = 4) |

| Ishigami et al., 2010 [67] | 40 | Pos. histology and/or cytology | Gastric cancer | Paclitaxel (20 mg/m2) at days 1 and 8 in 3-week cycles | 1/40 (2.5%) | Obstruction of IP catheter (n = 1) |

| Kitayama et al., 2012 [68] | 100 | Pos. histology | Gastric cancer | Paclitaxel (20 mg/m2) at days 1 and 8 in 3-week cycles | Rare (exact number not reported) | Not specified |

| Yamaguchi et al., 2013 [69] | 35 | Pos. histology | Gastric cancer | Paclitaxel (20 mg/m2) at days 1 and 8 in 3-week cycles | 6/35 (17.1%) | Obstruction of IP catheter (n = 3), port infection (n = 3) |

| Phase II studies | ||||||

| Chia et al., 2022 [66] | 44 | Pos. histology and/or cytology | Gastric cancer | Paclitaxel (40 mg/m2) at days 1 and 8 in 3-week cycles | 10/44 (23%) | Gr. 1 port leakage/infection, no intervention needed (n = 6), gr 3 would complications and re-siting of port (n = 4) |

| Ishigami et al., 2010 [67] | 40 | Pos. histology and/or cytology | Gastric cancer | Paclitaxel (20 mg/m2) at days 1 and 8 in 3-week cycles | 1/40 (2.5%) | Obstruction of IP catheter (n = 1) |

| Kitayama et al., 2012 [68] | 100 | Pos. histology | Gastric cancer | Paclitaxel (20 mg/m2) at days 1 and 8 in 3-week cycles | Rare (exact number not reported) | Not specified |

| Yamaguchi et al., 2013 [69] | 35 | Pos. histology | Gastric cancer | Paclitaxel (20 mg/m2) at days 1 and 8 in 3-week cycles | 6/35 (17.1%) | Obstruction of IP catheter (n = 3), port infection (n = 3) |

| Saito et al., 2021 [70] | 44 | Pos. histology and/or cytology | Gastric cancer | Paclitaxel (40 mg/m2) at days 1 and 8 in 3-week cycles | 6/44 (13.6%) | Gr. 3 obstruction of IP catheter (n = 3), gr 3. Port infection (n = 3) |

| Shi et al., 2021 [71] | 30 | Pos. histology | Gastric cancer | Paclitaxel (40 mg/m2) at days 1 and 8 in 3-week cycles | Rare (exact number not reported) | Peri-pump effusion (n = not specified), no obstructions or port infections reported. |

| Tu et al., 2022 [72] | 49 | Pos. histology and/or cytology | Gastric cancer | Paclitaxel (80 mg/m2) at days 1 in 3-week cycles | 0/49 (0%) | None |

| Cho et al., 2017 [73] | 39 | Pos. histology | Gastric cancer | Docetaxel (100 mg/m2) at days 1 in 3-week cycles | 2/39 (5.1%) | Gr. 3 port infection (n = 2) |

| Fushida et al., 2013 [74] | 27 | Pos. histology | Gastric cancer | Docetaxel (45 mg/m2) at days 1 and 15 in 4-week cycles | 6/27 (22%) | Gr. 1 or 2 abdominal pain after IP infusion (n = 5), port infection (n = 1) |

| Markman et al., 1985 [75] | 62 | Pos. histology | Ovarian cancer | Cisplatin (100 or 200 mg/m2) and cytosine arabinoside | Rare (exact number not reported) | Gr.3 bacterial peritonitis (n = 3), local abdominal pain (n = not reported) |

| Sood et al., 2004 [76] | 22 | Pos. histology | Ovarian cancer | Topotecan (1 mg/m2) on days 1 to 5 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Yamada et al., 2020 [77] | 46 | Pos. histology and/or cytology | Pancreatic cancer | Paclitaxel (20 mg/m2) at days 1, 8 and 15 in 4-week cycles | 14/46 (30.4%) | Peritoneal port trouble (not specified) (gr. 1, n=7; gr. 2, n=6; gr. 3, n=1) |

| Satoi et al., 2017 [78] | 33 | Pos. histology and/or cytology | Pancreatic cancer | Paclitaxel (20 mg/m2) at days 1 and 8 in 3-week cycles | 3/33 (9.1%) | Port dislocation (n = 2), port infection (n = 1) |

| Takahara et al., 2016 [79] | 35 | Pos. cytology | Pancreatic cancer | Paclitaxel (20 mg/m2) at days 1 and 8 in 3-week cycles | 5/35 (14.3%) | Port infection (gr ½, n=3; gr ¾, n=2) |

| Phase III studies | ||||||

| Ishigami et al., 2018 [80] | 183 | Pos. histology | Gastric cancer | Paclitaxel (20 mg/m2) at days 1 and 8 in 3-week cycles | 8/116 (6.9%) | Port infection (n = 3), catheter obstruction (n = 3), subcutaneous hematoma (n = 1), fistula (n = 1) |

| Bin et al., 2022 [81] | 78 | Pos. histology and/or cytology | Gastric cancer | Docetaxel (30 mg/m2) at days 1 and 8 in 3-week cycles | Not reported | Not reported |

| Saito et al., 2021 [70] | 44 | Pos. histology and/or cytology | Gastric cancer | Paclitaxel (40 mg/m2) at days 1 and 8 in 3-week cycles | 6/44 (13.6%) | Gr. 3 obstruction of IP catheter (n = 3), gr 3. Port infection (n = 3) |

| Shi et al., 2021 [71] | 30 | Pos. histology | Gastric cancer | Paclitaxel (40 mg/m2) at days 1 and 8 in 3-week cycles | Rare (exact number not reported) | Peri-pump effusion (n = not specified), no obstructions or port infections reported. |

| Tu et al., 2022 [72] | 49 | Pos. histology and/or cytology | Gastric cancer | Paclitaxel (80 mg/m2) at days 1 in 3-week cycles | 0/49 (0%) | None |

| Cho et al., 2017 [73] | 39 | Pos. histology | Gastric cancer | Docetaxel (100 mg/m2) at days 1 in 3-week cycles | 2/39 (5.1%) | Gr. 3 port infection (n = 2) |

| Fushida et al., 2013 [74] | 27 | Pos. histology | Gastric cancer | Docetaxel (45 mg/m2) at days 1 and 15 in 4-week cycles | 6/27 (22%) | Gr. 1 or 2 abdominal pain after IP infusion (n = 5), port infection (n = 1) |

| Markman et al., 1985 [75] | 62 | Pos. histology | Ovarian cancer | Cisplatin (100 or 200 mg/m2) and cytosine arabinoside | Rare (exact number not reported) | Gr.3 bacterial peritonitis (n = 3), local abdominal pain (n = not reported) |

| Sood et al., 2004 [76] | 22 | Pos. histology | Ovarian cancer | Topotecan (1 mg/m2) on days 1 to 5 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Yamada et al., 2020 [77] | 46 | Pos. histology and/or cytology | Pancreatic cancer | Paclitaxel (20 mg/m2) at days 1, 8 and 15 in 4-week cycles | 14/46 (30.4%) | Peritoneal port trouble (not specified) (gr. 1, n=7; gr. 2, n=6; gr. 3, n=1) |

| Satoi et al., 2017 [78] | 33 | Pos. histology and/or cytology | Pancreatic cancer | Paclitaxel (20 mg/m2) at days 1 and 8 in 3-week cycles | 3/33 (9.1%) | Port dislocation (n = 2), port infection (n = 1) |

| Takahara et al., 2016 [79] | 35 | Pos. cytology | Pancreatic cancer | Paclitaxel (20 mg/m2) at days 1 and 8 in 3-week cycles | 5/35 (14.3%) | Port infection (gr ½, n=3; gr ¾, n=2) |

| Ishigami et al., 2018 [80] | 183 | Pos. histology | Gastric cancer | Paclitaxel (20 mg/m2) at days 1 and 8 in 3-week cycles | 8/116 (6.9%) | Port infection (n = 3), catheter obstruction (n = 3), subcutaneous hematoma (n = 1), fistula (n = 1) |

| Bin et al., 2022 [81] | 78 | Pos. histology and/or cytology | Gastric cancer | Docetaxel (30 mg/m2) at days 1 and 8 in 3-week cycles | Not reported | Not reported |

The Port-A-Cath (PAC) was the port type used in all studies. Definition unres. Peritoneal disease clarifies whether positive peritoneal histology, or positive peritoneal cytology, or both were required to fulfill the definition of unresectable peritoneal disease

Gr grade, IP intraperitoneal, N number of patients, unres. unresectable

Results of Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy for Unresectable Peritoneal Surface Malignancies

Gastric Cancer

Peritoneal metastasis is the most common form of dissemination in patients with gastric cancer. It is found in approximately 14% of all newly diagnosed gastric cancer patients and is the most common form of recurrence (~ 60%) after surgery [5, 84]. The prognosis is unfavorable with a median overall survival of 9.4 months despite systemic therapy [85]. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy has gained attention, especially in Asian countries. Table 3 gives an overview of the results of all Phase I, Phase II and Phase III studies on intraperitoneal chemotherapy for gastric cancer. Paclitaxel is one of the most frequently applied intraperitoneal agents for gastric cancer, in combination with various systemic regimens. However, a retrospective analysis on intraperitoneal paclitaxel showed that the type of systemic chemotherapy did not influence overall survival [86]. In Phase I studies, intraperitoneal paclitaxel in combination with several types of systemic chemotherapy resulted in recommended doses between 20 and 80 mg/m2, depending on the frequency of administration [87–93]. The most common dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) were hematological disorders (mostly neutropenia) or gastro-intestinal toxicities such as diarrhea or vomiting. No port complications occurred as DLTs in any of the Phase I studies. In a Phase II study on weekly intraperitoneal paclitaxel with systemic capecitabine/oxaliplatin (CAPOX) for patients with peritoneal metastasis without other distant metastases and a ECOG performance status of zero to two, median overall survival was 14.6 months. In 13 of 44 patients (30%) with primary unresectable peritoneal metastases, conversion surgery was performed after intraperitoneal chemotherapy [66]. Weekly intraperitoneal paclitaxel with systemic paclitaxel or oxaliplatin and S-1 showed promising results in other Phase II studies with 1-year overall survival rates ranging between 78 and 80% and median overall survival of 15.1–25.8 months [67–71]. High-dose intraperitoneal paclitaxel (80 mg/m2) in 3-week cycles combined with oxaliplatin and S-1 showed comparable results with a 1-year overall survival rate of 82% and a median overall survival of 16.9 months [72]. In patients receiving intraperitoneal paclitaxel, several prognostic factors were discovered. Patients with an apparent reduction of ascites volume (>50%) had a better median overall survival than patients without (15.1 months vs 6.7 months, respectively) [94]. Moreover, change of positive cytology of peritoneal lavage fluid (CY1) to negative cytology (CY0) during intraperitoneal paclitaxel treatment was a positive prognostic factor (median OS 20.0 vs 13.0 months, respectively) [95]. These encouraging results led to the Phase III PHOENIX-GC trial [80]. A total of 183 patients with peritoneal metastases of gastric cancer were randomized at a two-to-one ratio to receive intraperitoneal and systemic chemotherapy (IP and IV paclitaxel plus oral S-1) or systemic treatment alone (IV cisplatin plus S-1). This study failed to show a statistical superiority of intraperitoneal paclitaxel (median overall survival IP group 17.7 months vs standard group 15.2 months, p = 0.080). In an exploratory post hoc analysis adjusted for baseline volume of ascites, overall survival was longer in the IP arm (HR 0.59, 95% CI 0.39–0.87, p = 0.008). The baseline amount of ascites was namely not comparable between the groups (ascites present in IP arm 63% vs 42% in standard arm). However, being a post hoc analysis, these results should be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, the PHOENIX-GC trial is limited by the different systemic regimens in both treatment arms. Platinum/5-FU combination therapy is the mainstay of systemic chemotherapy for gastric cancer and might be more effective than intravenous paclitaxel plus oral S-1. A follow-up analysis with 3-year overall survival rates suggested a survival benefit of intraperitoneal paclitaxel (IP group 21.9% vs standard group 6.0%). Several ongoing trials investigate the efficacy of intraperitoneal paclitaxel, in combination with various systemic therapies such as 5-fluorouracil/oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) or CAPOX (NCT03618758, NCT04943653, NCT04034251 and NCT05204173). Moreover, results from a non-randomized prospective study comparing the efficacy of intraperitoneal paclitaxel and bevacizumab + oral S-1 versus IV oxaliplatin + S-1 are anticipated soon (NCT03990103).

Table 3.

Results of intraperitoneal chemotherapy for unresectable peritoneal metastasis of gastric origin

| Author, year | LOI | N | Definition unres. peritoneal disease | IP therapy | Systemic therapy | MTD | RD | Dose-limiting toxicities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I studies | ||||||||

| Ishigami et al., 2010 [87] | 4 | 9 | Pos. histology | Paclitaxel and cisplatin at days 1 and 15 in 4-week cycles | Cisplatin |

IP paclitaxel 20 mg/m2, IP cisplatin 30 mg/m2 |

IP paclitaxel 20 mg/m2, IP cisplatin 25 mg/m2 |

Leukopenia grade 4, vomiting grade 3 |

| Ishigami et al., 2009 [88] | 4 | 9 | Pos. histology and/or cytology | Paclitaxel at days 1 and 8 in 3-week cycles | Paclitaxel + S-1 | 30 mg/m2 | 20 mg/m2 | Febrile neutropenia grade 3, diarrhea grade 3 |

| Kurita et al., 2011 [89] | 4 | 18 | Pos. histology and/or cytology | Paclitaxel at days 1 and 14 in 4-week cycles | S-1 | 90 mg/m2 | 80 mg/m2 | Leukocytopenia grade 3 |

| Vatandoust et al., 2022 [90] | 4 | 15 | Pos. histology | Paclitaxel at days 1 and 8 in 3-week cycles | Cisplatin + capecitabine | Not reached | 30 mg/m2 | Small bowel obstruction grade 3, febrile neutropenia grade 3 |

| Kobayashi et al., 2020 [91] | 4 | 9 | Pos. histology | Paclitaxel at days 1, 8 and 22 in 5-week cycles | Cisplatin + S-1 | Not reached | 20 mg/m2 | None |

| Kim et al., 2021 [92] | 4 | 9 | Pos. histology | Paclitaxel at days 1 and 8 in 3-week cycles | Oxaliplatin + S-1 | Not reached | 80 mg/m2 | None |

| Kang et al., 2022 [93] | 4 | 15 | Pos. histology | Paclitaxel at days 1 and 8 in 3-week cycles | 5-FU, leucovorin and oxaliplatin | 80 mg/m2 | 60 mg/m2 | Febrile neutropenia grade 3 |

| Cho et al., 2017 [73] | 4 | 12 | Pos. histology | Docetaxel at day 1 in 3-week cycles | Cisplatin + capecitabine | Not reached | 100 mg/m2 | Ileus grade 3 |

| Fushida et al., 2013 [74] | 4 | 12 | Pos. histology | Docetaxel at days 1 and 14 in 4-week cycles | S-1 | 50 mg/m2 | 45 mg/m2 | Febrile neutropenia grade 3, diarrhea grade 3 |

| Phase II studies | ||||||||

| Chia et al., 2022 [66] | 2b | 44 | Pos. histology and/or cytology | Paclitaxel (40 mg/m2) at days 1 and 8 in 3-week cycles | Oxaliplatin + capecitabine | 67.8% (95% CI: not reported) | 14.6 m (95% CI: 12.6 m – 16.6 m)( | Neutropenia (18%), electrolyte derangements (14%), port leakage/infection (9%), febrile neutropenia (9%), |

| Ishigami et al., 2010 [67] | 2b | 40 | Pos. histology and/or cytology | Paclitaxel (20 mg/m2) at days 1 and 8 in 3-week cycles | Paclitaxel + S-1 |

78% (95% CI: 65–90%) |

22.5 m (95% CI: 16.6 m – NR) |

Neutropenia (38%), leukopenia (18%), anemia (10%), nausea/vomiting (8%) |

| Kitayama et al., 2012 [68] | 2b | 100 | Pos. histology | Paclitaxel (20 mg/m2) at days 1 and 8 in 3-week cycles | Paclitaxel + S-1 |

80% (95% CI: not reported) |

23.6 m (95% CI: not reported) |

Neutropenia (36%), leukopenia (20%), anemia (8%) |

| Yamaguchi et al., 2013 [69] | 2b | 35 | Pos. histology | Paclitaxel (20 mg/m2) at days 1 and 8 in 3-week cycles | Paclitaxel + S-1 |

77.1% (95% CI: 60.5–88.1%) |

17.6 m (95% CI: 13.3 m – NR) |

Neutropenia (34%), leukopenia (23%), anemia (9%), vomiting (3%) |

| Saito et al., 2021 [70] | 2b | 44 | Pos. histology and/or cytology | Paclitaxel (40 mg/m2) at days 1 and 8 in 3-week cycles | Oxaliplatin + S-1 |

79.5% (95% CI: 64.4–88.8%) |

25.8 m (95% CI: 16.3 m – NR) |

Neutropenia (39%), anemia (14%) leukopenia (11%), port-related complication (7%) |

| Shi et al., 2021 [71] | 2b | 30 | Pos. histology | Paclitaxel (40 mg/m2) at days 1 and 8 in 3-week cycles | Oxaliplatin + S-1 | Not reported |

15.1 m (95% CI: 12.4 m – 17.8 m) |

Peripheral sensory neuropathy (40%), nausea/vomiting (27%), leukopenia (23%) |

| Tu et al., 2022 [72] | 2b | 49 | Pos. histology and/or cytology | Paclitaxel (80 mg/m2) at days 1 in 3-week cycles | Oxaliplatin + S-1 |

81.6% (95% CI: 68.6–90%) |

16.9 m (95% CI: 13.6 – 20.2) |

Neutropenia (41%), anemia (22%), leukopenia (18%), nausea (14%) |

| Cho et al., 2017 [73] | 2b | 39 | Pos. histology | Docetaxel (100 mg/m2) at days 1 in 3-week cycles | Cisplatin + capecitabine | Not reported |

15.1 m (95% CI: 9.1 – 21.1 m) |

Neutropenia (39%), abdominal pain (31%), anemia (26%), febrile neutropenia (23%) |

| Fushida et al., 2013 [74] | 2b | 27 | Pos. histology | Docetaxel (45 mg/m2) at days 1 and 15 in 4-week cycles | S-1 |

70% (95% CI: 53–87%) |

16.2 m (95% CI: 8.4 – 22.1 m) |

Anorexia (18.5%), neutropenia (7%), leukopenia (7%) |

| Phase III studies | ||||||||

| Ishigami et al., 2018 [80] | 1b | 183 | Pos. histology | Paclitaxel (20 mg/m2) + paclitaxel and S-1 | Cisplatin + S-1 |

Median OS 17.7 vs 15.2 m (p = 0.080) 3-year OS: 21.9 vs 6.0%; |

Neutropenia and leukopenia grade 3/4 IP vs SP resp. 50% vs 30% and 25% vs 9% | |

| Bin et al., 2022 [81] | 2b | 78 | Pos. histology and/or cytology | Docetaxel (30 mg/m2) + oxaliplatin and S-1 | Docetaxel + oxaliplatin and S-1 | Median OS 11.7 vs 10.3 m (p = 0.005) | Neutropenia and leukopenia grade 3/4 IP vs SP resp. 26% vs 54% and 54% and 26% | |

Definition of unres. peritoneal disease clarifies whether positive peritoneal histology, or positive peritoneal cytology, or both were required to fulfill the definition of unresectable peritoneal disease

5-FU fluorouracil, IP intraperitoneal, IV intravenous, LOI level of evidence for therapeutic studies according to the grading of the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, m months, MTD maximum tolerated dose, N number of patients, NR not reported, OS overall survival, RD recommended dose, SP standard regime patients, unres. unresectable

Another frequently utilized intraperitoneal agent for gastric cancer is docetaxel. Intraperitoneal docetaxel in combination with systemic capecitabine and cisplatin resulted in a recommended dose of 100 mg/m2 and a median overall survival of 15.1 months. Most frequent grade 3/4 adverse events were neutropenia (38.6%) and abdominal pain (30.8%) [73]. Intraperitoneal docetaxel in combination with systemic S-1 resulted in a lower recommended dose of 45 mg/m2, and a median overall survival of 16.2 months. The most frequent grade 3/4 adverse events were anorexia (18.5%), neutropenia (7.4%) and leukopenia (7.4%) [74]. A recent randomized Phase III study assigned 78 patients to intraperitoneal docetaxel 30 mg/m2 (with systemic oxaliplatin and S-1) or to systemic docetaxel, oxaliplatin and S-1. This study found a higher median overall survival in the IP group (11.7 vs 10.3 months, HR 0.52, 95% CI 0.31–0.86, p = 0.005), despite the lack of systemic docetaxel in the experimental group. Moreover, ascites control rates were better in the intraperitoneal group (58.9% vs 30.8%, p = 0.012) and grade 3/4 hematological adverse events were lower in the intraperitoneal group (26% vs 54%, p = 0.01) [81]. A study combining intraperitoneal docetaxel with systemic FOLFOX has recently started (NCT04583488). Lastly, irinotecan has gained attention for intraperitoneal use since activation to its active form SN-38 occurs in the peritoneum. A Phase I study is currently investigating the recommended dose and toxicity profile of intraperitoneal irinotecan combined with systemic CAPOX for gastric cancer (NCT05379790).

As a conclusion, intraperitoneal chemotherapy for unresectable peritoneal metastases of gastric origin has been investigated in several studies, primarily in the Asian population. Despite the promising results in Phase II studies, two Phase III studies showed contradictory results, resulting in a low level of evidence for IP chemotherapy in patients with gastric cancer. Therefore, as yet, intraperitoneal chemotherapy does not have a place as a standard treatment for unresectable gastric cancer, and future randomized Phase III studies with comparable baseline characteristics in the treatment groups.

Ovarian Cancer

In ovarian cancer, peritoneal dissemination occurs frequently [96]. In patients with limited peritoneal disease, intraperitoneal adjuvant cisplatin chemotherapy is often administered after optimal cytoreductive surgery in FIGO stage III ovarian cancer. Table 4 provides an overview of the Phase I and II studies in unresectable peritoneal metastases. In 1985, Markman et al showed that a high dose of intraperitoneal cisplatin (200 mg/m2) and intraperitoneal cytosine arabinoside in combination with systemic sodium thiosulfate was feasible and safe with a clinical response in 16 of 52 patients [75]. Moreover, a retrospective analysis showed that intraperitoneal cisplatin and intraperitoneal paclitaxel resulted in improved survival compared to standard systemic chemotherapy [97]. The authors matched 33 IP-treated patients with 66 patients who underwent systemic therapy and found a survival advantage for patients who had no more than two previous treatment lines (HR 0.21, 95% CI 0.09–0.48, p < 0.001). However, as this was a subgroup analysis of a small retrospective study, one should be careful with the interpretation of these results. A comparable agent, oxaliplatin, resulted in a maximum-tolerated dose (MTD) of 50 mg/m2 when combined with systemic docetaxel [98]. Prolonged neutropenia and abdominal pain were the DLTs. Docetaxel itself was also used as intraperitoneal chemotherapy and resulted in a MTD of 75 mg/m2 in combination with systemic oxaliplatin, with neutropenia as the most common DLT. Median time to progression was 4.5 months [99]. A retrospective analysis of intraperitoneal mitoxantrone in 106 patients with ovarian carcinoma found that this treatment is safe and tolerable, and especially useful in reducing ascites levels [49]. In 63% of the patients, ascites volume was reduced by more than 50%. The only Phase II study this century on intraperitoneal chemotherapy investigated intraperitoneal topotecan and oral etoposide [76]. In 22 patients, intraperitoneal topotecan was administered as 1 mg/m2 and resulted in a median survival of 12.8 months. A complete clinical response was observed in three patients (14%) and the regimen was well tolerated. Grade 4 neutropenia and thrombocytopenia occurred in eight and four patients (36 and 18%), respectively. No grade 4 non-hematological toxicities were reported. Unfortunately, these promising results were not followed by a Phase III trial and no additional trials are ongoing. This could be explained by the fact that optimal debulking is increasingly used in patients with stage III/IV ovarian cancer [100]. Therefore, studies on intraperitoneal chemotherapy without the use of surgery have ceased and are not expected in the near future. The current evidence for intraperitoneal chemotherapy for unresectable ovarian cancer is therefore low.

Table 4.

Results of intraperitoneal chemotherapy for unresectable peritoneal metastasis of ovarian origin

| Author, year | LOI | N | Definition unres. peritoneal disease | IP therapy | Systemic therapy | MTD | RD | Dose-limiting toxicities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I studies | ||||||||

| Taylor et al., 2015 [98] | 4 | 13 | Pos. histology | Oxaliplatin at days 2 in 3-week cycles | Docetaxel | 50 mg/m2 | 50 mg/m2 | Prolonged neutropenia, abdominal pain |

| Taylor et al., 2019 [99] | 4 | 12 | Pos. histology | Docetaxel at days 2 in 3-week cycles | Oxaliplatin | 75 mg/m2 | 75 mg/m2 | Prolonged neutropenia, infection, hyponatremia, abdominal pain |

| Phase II studies | ||||||||

| Markman et al., 1985 [75] | 4 | 62 | Pos. histology | Cisplatin (100 or 200 mg/m2) and cytosine arabinoside | Sodium thiosulfate | Not reported |

10.5 m (range: 1.0–16.0 m) |

Nausea and vomiting, fever (without infection), nephrotoxicity |

| Sood et al., 2004 [76] | 4 | 22 | Pos. histology | Topotecan (1 mg/m2) on days 1 to 5 in 4-week cycles | Etoposide | Not reported | 54.8 weeks | Neutropenia (68%), anemia (45%), thrombocytopenia (36%), vomiting (9%) |

Definition unres. peritoneal disease clarifies whether positive peritoneal histology, or positive peritoneal cytology, or both were required to fulfill the definition of unresectable peritoneal disease

IP intraperitoneal, LOI level of evidence for therapeutic studies according to the grading of the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, m months, MTD maximum tolerated dose, N number of patients, OS overall survival, RD recommended dose, unres. unresectable

Pancreatic Cancer

Peritoneal metastases are present in approximately 50% of patients with pancreatic cancer at the time of death and are one of the most important poor prognostic factors [101, 102]. As median overall survival for pancreatic cancer patients with peritoneal metastasis is only 7.6 months when treated with systemic chemotherapy, innovative treatment options such as intraperitoneal chemotherapy are warranted [103]. For this use, intraperitoneal paclitaxel has been the only agent investigated so far. Table 5 presents all prospective studies performed with intraperitoneal chemotherapy in patients with pancreatic cancer. Two Phase I studies found a recommended dose of 30 mg/m2 and 20 mg/m2 for intraperitoneal paclitaxel when combined with systemic gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel [77, 104]. Dose-limiting toxicities were port dysfunction, pneumonia, neutropenia, and gastrointestinal hemorrhage. In a consecutive Phase II study with 20 mg/m2 intraperitoneal paclitaxel, a median overall survival of 14.5 months was reached [77]. Two other Phase II studies combined intraperitoneal paclitaxel with intravenous paclitaxel and oral S-1 [78, 79]. One study included chemotherapy-naive pancreatic cancer patients with peritoneal dissemination, but with no other distant metastases, and found a median overall survival of 16.3 months [78]. In the second study, intraperitoneal paclitaxel was investigated in a group of gemcitabine-refractory patients with peritoneal and distant metastases [79]. In this heavily treated population, median overall survival was 4.8 months. A recent analysis combined above-mentioned studies to investigate the possibility of conversion surgery [105]. In 16 of 79 patients (20.3%) conversion surgery was performed after completion of intraperitoneal chemotherapy. In those patients, median overall survival was 32.5 months (range, 13.5–66.9 months). The authors announced a Phase III study, comparing intraperitoneal paclitaxel to systemic chemotherapy in this patient population [106]. Currently, there is insufficient clinical evidence for intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal metastases of pancreatic origin to be applied in daily clinical practice, but this Phase III study will likely determine its role and potentially expand the treatment landscape for this patient population in the case of a positive result.

Table 5.

Results of intraperitoneal chemotherapy for unresectable peritoneal metastasis of pancreatic origin

| Author, year | LOI | N | Definition unres. peritoneal disease | IP therapy | Systemic therapy | MTD | RD | Dose-limiting toxicities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I studies | ||||||||

| Takahara et al., 2021 [104] | 4 | 12 | Pos. histology | Paclitaxel at days 1, 8 and 15 in 4-week cycles | Gemcitabine + nab-paclitaxel | Not reached | 30 mg/m2 | Port dysfunction grade 3, pneumonia grade 3 |

| Yamada et al., 2020 [77] | 4 | 10 | Pos. histology and/or cytology | Paclitaxel at days 1, 8 and 15 in 4-week cycles | Gemcitabine + nab-paclitaxel | 50 mg/m2 for nab-paclitaxel | 20 mg/m2 | Neutropenia grade 4, gastrointestinal hemorrhage grade 5 |

| Phase II studies | ||||||||

| Yamada et al., 2020 [77] | 2b | 46 | Pos. histology and/or cytology | Paclitaxel (20 mg/m2) at days 1, 8 and 15 in 4-week cycles | Gemcitabine + nab-paclitaxel | 61% |

14.5 m (range: 11.5–19.2 m) |

Neutropenia (32%), leukocytopenia (22%), anemia (8%) |

| Satoi et al., 2017 [78] | 2b | 33 | Pos. histology and/or cytology | Paclitaxel (20 mg/m2) at days 1 and 8 in 3-week cycles | Paclitaxel + oral S-1 | 62% |

16.3 m (range: 11.5–22.6 m) |

Neutropenia (42%), leukopenia (18%), appetite loss (12%), nausea (9%) |

| Takahara et al., 2016 [79] | 2b | 35 | Pos. cytology | Paclitaxel (20 mg/m2) at days 1 and 8 in 3-week cycles | Paclitaxel + oral S-1 | Not reported |

4.8 m (95% CI: 2.1–5.3 m) |

Neutropenia (34%), anemia (31%), thrombocytopenia (9%), anorexia (9%) |

Definition unres. peritoneal disease clarifies whether positive peritoneal histology, or positive peritoneal cytology, or both were required to fulfill the definition of unresectable peritoneal disease

IP intraperitoneal, LOI level of evidence for therapeutic studies according to the grading of the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, m months, MTD maximum tolerated dose, N number of patients, OS overall survival, RD recommended dose, unres. unresectable

Colorectal Cancer

Peritoneal lesions occur in approximately 15% of the patients with colorectal cancer [107]. CRS-HIPEC has become standard of care in patients with low to moderate disease load [108]. In patients with a high peritoneal tumor load and in whom CRS-HIPEC is not possible, intraperitoneal chemotherapy has been a subject of investigation. A Phase I study investigating intraperitoneal paclitaxel 20 mg/m2 in combination with systemic FOLFOX or CAPOX and bevacizumab in six patients found no dose-limiting or grade 4 toxicities [109]. Adverse events were comparable with systemic FOLFOX or CAPOX alone. Although the validity of the study is limited by the small sample size, survival rates were promising with median survival rate of 29.3 months [110]. Another Phase I study is investigating intraperitoneal irinotecan in combination with systemic FOLFOX, and results are expected soon. [111] A subsequent Phase II study has been initiated recently (NL81672.100.22). A Phase I study testing intraperitoneal oxaliplatin in combination with systemic FOLFORI (5-fluorouracil, leucovorin and irinotecan) is also underway (NCT02833753). So far, two DLTs were reported in the 85 mg/m2 group, and three additional patients are being enrolled into the 55 mg/m2 group. As for now, clinical evidence for repeated intraperitoneal chemotherapy in patients with unresectable peritoneal metastases of colorectal cancer is low, as results of potential Phase II or III studies are not yet available.

Peritoneal Mesothelioma

Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma (MPM) is a rare and aggressive malignancy confined to the serosal lining of the abdominal cavity [112]. Surgery is only possible in a small selection of patients, as the disease has often already spread widely across the peritoneum [113]. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy seems a logical and promising treatment option, because MPM is mostly limited to the peritoneal cavity [112]. However, as MPM is a rare disease, few studies have been performed. In 1992, Markman et al treated 19 MPM patients with intraperitoneal cisplatin 100 mg/m2 every 28 days [51]. The treatment was well tolerated up to a maximum of four to five cycles. Median survival was nine months, but four patients (21%) responded extremely well and survived for over three years. A retrospective analysis included 8 MPM patients who were treated with intraperitoneal cisplatin in combination with systemic irinotecan [114]. This combination did not lead to any complete responses, but partial remission and stable disease were observed in most patients and the treatment was well tolerated. Most common side effects were nausea and vomiting. Recently, a prospective Phase I/II study with intraperitoneal paclitaxel has started (NL9718) [31]. As there is currently very limited evidence for any treatment for patients with unresectable peritoneal mesothelioma, positive results of this Phase II study will likely be adapted quickly in the treatment guidelines while awaiting the results of a Phase III study. However, it is questionable if a Phase III study will ever be feasible due to the rarity of the disease.

Pseudomyxoma Peritsonei

Pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP) is a rare disease caused by mucinous tumor cells located in the peritoneal cavity producing mucin and ascites [115]. As the disease is limited to the abdominal space and most often slow-growing, local treatment seems an appealing approach [115]. Trials on intraperitoneal chemotherapy have been performed only in combination with cytoreductive surgery [9, 115]. No studies were identified that tested intraperitoneal chemotherapy for unresectable disease. As (repeated) surgical debulking (often combined with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy) is the standard treatment of PMP, no studies are expected in the near future investigating intraperitoneal chemotherapy without surgery. Two small observational studies on patients with PMP are described below.

Pressurized Intraperitoneal Aerosol Chemotherapy

Pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy is a novel, alternative intraperitoneal treatment method using pressurized vaporization to deliver doxorubicin and cisplatin [116]. Nine prospective Phase I and II studies with predefined endpoints have been performed in several tumor types. As the dosages of the chemotherapy used in preliminary PIPAC studies were arbitrarily chosen and derived from the dose administered in HIPEC treatment, three recent Phase I studies ought to confirm these dosages. For oxaliplatin, higher doses than hypothesized were found to be well tolerated (ranging from 90 to 135 mg/m2) [117–119]. For cisplatin and doxorubicin, doses of 30 mg/m2 and 6 mg/m2, respectively, were found to be safe [118]. A recent Phase I study used nab-paclitaxel in 23 patients with several tumor types (of whom 13 patients continued systemic chemotherapy) and found a recommended Phase II dose of 140 mg/m2 [120]. Four Phase II studies on PIPAC have been performed so far. A Phase II study in 64 ovarian cancer patients with doxorubicin (1.5 mg/m2) and cisplatin (7.5 mg/m2) found a mean OS of 11 months and no grade 4 or 5 adverse events. Of 53 evaluable patients (in the remaining 11 patients laparoscopic access was not possible), 30 patients had stable disease and three patients had a partial response [121]. Two Phase II studies investigated PIPAC treatment in patients with peritoneal metastases of gastric origin. The first study administered PIPAC monotherapy (cisplatin and doxorubicin) in 25 patients and found a median OS of 6.7 months, with a tolerable safety profile [122]. The other study on 31 gastric cancer patients with PIPAC in combination with CAPOX found a median OS of 13 months. The therapy was well tolerated with no grade 4 or higher adverse events [123]. Another Phase II study treated 20 colorectal cancer patients with PIPAC monotherapy (oxaliplatin) [124]. Median overall survival was 8 months and major treatment-related adverse events occurred in 3 of 20 (15%) patients, including one possibly treatment-related death due to sepsis. Minor adverse events occurred in all patients, with abdominal pain being the most common (88%). The last Phase II study treated 63 patients with unresectable peritoneal carcinomatosis of several tumor types (most commonly gastric cancer or ovarian cancer) and found a median overall survival of 15 months. These survival data are difficult to interpret as several tumor types were included, different PIPAC schedules were used, and some patients received concomitant systemic treatment, whereas other did not [125]. Moreover, several observational studies reporting the safety and feasibility of PIPAC treatment in various tumor types concluded that PIPAC is generally well tolerated [126–134]. However, as these studies are retrospective analyses based on databases without predefined outcome variables, it is difficult to draw definite conclusions based on these results. Two observational studies describe the use of PIPAC in patients with PMP (n = 5) [133, 134]. Pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy was safe and median survival was not reached after 11.8 months. However, the small sample size must be considered when interpreting these promising results. As for now, the evidence level for PIPAC is low and not sufficient to be integrated into the current guidelines. More prospective studies to determine the role of PIPAC and improve patient selection are ongoing, including two randomized Phase III studies in upper gastro-intestinal adenocarcinomas and ovarian carcinoma (resp.: EudraCT: 2018-001035-40 and EudraCT number 2018-003664-31) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Results of pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy for unresectable peritoneal metastasis of several origins

| Author, year | N | LOI | Definition unres. peritoneal disease | Tumor type | PIPAC (and systemic) therapy | MTD | RD | Dose-limiting toxicities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I studies | ||||||||

| Dumont et al., 2020 [117] | 10 | 4 | Pos. histology | Gastro-intestinal |

PIPAC: oxaliplatin Systemic: leucovorin + 5-FU |

90 mg/m2 | 90 mg/m2 | Neutropenia grade 3, allergic reaction grade 4 |

| Robella et al., 2021 [118] | 13 | 4 | Pos. histology and/or cytology | Several | PIPAC: oxaliplatin, cisplatin + doxorubicin, systemic: none | Not reached | Resp: 135 mg/m2, 30 mg/m2 and 6 mg/m2 | None |

| Kim et al., 2021 [119] | 16 | 4 | Pos. histology and/or cytology | Gastro-intestinal |

PIPAC: oxaliplatin Systemic: none |

120 mg/m2 | 120 mg/m2 | Pancreatitis grade 3 |

| Ceelen et al., 2022 [120] | 23 | 4 | Pos. histology | Several | PIPAC: nab-paclitaxel, systemic: 65% of the patients, several regimens | 140 mg/m2 | 140 mg/m2 | Based on a calculated posterior probability of DLT of 15%. |

| Phase II studies | ||||||||

| Tempfer et al., 2015 [121] | 64 | 2b | Pos. histology | Ovarian |

PIPAC: doxorubicin (1.5 mg/m2) + cisplatin (7.5 mg/m2) Systemic: none |

50% | NR, mean OS: 10.9 m (95% CI: 9.6–12.2 m) | Trocar hernia (4%), abdominal pain (4%) |

| Struller et al., 2019 [122] | 25 | 2b | Pos. histology | Gastric |

PIPAC: doxorubicin (1.5 mg/m2) + cisplatin (7.5 mg/m2) Systemic: none |

NR | 6.7 m (95% CI: 2.5–12.0 m) | Subilieus (8%), abdominal pain (4%) |

| Khomyakov et al., 2016 [123] | 31 | 2b | Pos. histology | Gastric |

PIPAC: doxorubicin (1.5 mg/m2) + cisplatin (7.5 mg/m2) Systemic: capecitabine + oxaliplatin |

49.8% | 13 m (range: NR) | Only toxicities reported associated with PIPAC procedure: diaphragmatic perforation (3%) |

| Rovers et al., 2021 [124] | 20 | 2b | Pos. histology | Colorectal |

PIPAC: oxaliplatin (92 mg/m2) Systemic: none |

NR | 8.0 m (IQR 6.3–12.6 m) | Leukocytosis (85%), lymphocytopenia (25%), dead due to sepsis of unknown origin (5%) |

| De Simone et al., 2020 [125] | 63 | 4 | Pos. histology | Several | No standardized regimens (several types used dependent upon tumor type) | 67% | 15 m (range: NR) | Anemia (1.5%), nausea (1.5%), surgery-related complication (1.5%) |

Definition unres. peritoneal disease clarifies whether positive peritoneal histology, or positive peritoneal cytology, or both were required to fulfil the definition of unresectable peritoneal disease

5-FU fluorouracil, IP intraperitoneal, IV intravenous, LOI level of evidence for therapeutic studies according to the grading of the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, m months, MTD maximum tolerated dose, N number of patients, NR not reported, OS overall survival, RD recommended dose, SP standard regime patients, unres. unresectable

Discussion

Clinical issues remain to be resolved before intraperitoneal chemotherapy could be a potential standard treatment option for patients with unresectable peritoneal surface malignancies. More clinical trials are warranted to assess the efficacy of intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Both Phase II studies assessing the efficacy and safety of intraperitoneal chemotherapy, followed by Phase III studies comparing its efficacy to (standard) systemic chemotherapy alone, are needed to generate more data on the additional value of intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Most studies were prospectively performed with a well-defined group of patients (i.e., peritoneal metastases were proven with laparoscopy in all studies), but widespread usage is hampered by small patient numbers, varying cytotoxic agents and dose levels, and non-randomized designs. The only two Phase III studies on intraperitoneal chemotherapy showed contradictory results, with one study showing superiority of intraperitoneal chemotherapy over standard systemic chemotherapy in patients with gastric cancer whereas the other study did not [80, 81]. Subgroup analyses of the latter study corrected for baseline ascites and 3-year follow-up result suggested a survival benefit but should be interpreted with caution [80]. Therefore, future studies should primarily focus on survival instead of response rate, which is hard to evaluate by CT scan. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or FAPI PET/CT scan might be more accurate for response evaluation of peritoneal tumor, but these modalities are also associated with false-negative outcomes, have longer exam times, and higher costs [135, 136]. Furthermore, the optimal chemotherapy regimen is under debate. Multiple agents have been proposed for intraperitoneal use and a subset of regimens have been tested as concurrent systemic therapy. Optimal treatment schedules are lacking and are hampered by the heterogeneity of evidence. Intraperitoneal immunotherapy, such as checkpoint inhibitors or tumor-specific antibodies, might be a promising route for in the future, but current evidence is confined to animal-studies only [62, 63]. To generalize the use of intraperitoneal chemotherapy and to determine the optimal drug combination, studies directly comparing different regimens are warranted. Finally, the impact of intraperitoneal chemotherapy on quality of life is unknown and should be considered in future studies. As intraperitoneal chemotherapy is mostly applied in the palliative setting, quality of life is hugely important.

Limitations of the present review include the variety of definitions for unresectable disease in the different studies and the various regimens used. This limits comparability of the studies. Furthermore, most studies were performed in the Asian population, which affects the external validity of the results.

In conclusion, peritoneal dissemination has been regarded as a terminal condition ever since, and treatment has been palliative in the majority of patients with disappointing results. Repeated intraperitoneal administration of anticancer drugs has shown to be a promising and safe treatment strategy for unresectable peritoneal surface malignancies in Phase I or II studies, with conversion surgery as potential curative treatment in selected patients with excellent response. The separate ways in which intraperitoneal chemotherapy can be delivered (PIPAC and normothermic repeated intraperitoneal chemotherapy) are important. However, there is insufficient evidence to implement intraperitoneal chemotherapy in daily clinical practice because the results of the only two Phase III studies so far have been contradictory. More studies on the efficacy of intraperitoneal chemotherapy in comparison to current standard treatments and on the optimal drug selection are needed to investigate if intraperitoneal chemotherapy might eventually change the treatment landscape in patients with unresectable peritoneal dissemination and be integrated in daily practice and in guidelines.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Wichor Bramer, Marjolein Udo and Maarten Engel from the Erasmus MC Medical Library for developing and updating the search strategies. Figures 1 and 2 were created using BioRender.org.

Declarations

Funding

No external funding was used in the preparation of this manuscript.

Competing Interests

Bas P.L. Wijnhoven received consulting fees and a research grant from BMS. Bianca Mostert received consulting fees from Lilly, Servier and BMS, and research funding from Sanofi, Pfizer and BMS. Niels A.D. Guchelaar, Bo J. Noordman, Stijn L.W. Koolen, Eva V.E. Madsen, Jacobus W.A. Burger, Alexandra R.M. Brandt-Kerkhof, Geert-Jan Creemers, Ignace H.J.T. de Hingh, Misha Luyer, Sander Bins, Esther van Meerten, Sjoerd M. Lagarde, Cornelis Verhoef and Ron. H.J. Mathijssen declare that they have no conflicts of interest that might be relevant to the contents of this manuscript.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

NADG: conceptualization, methodology, validation, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, visualization, project administration. BJN: conceptualization, methodology, validation, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, visualization, project administration. SLWK: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, writing—review and editing. BM: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, writing—review and editing. EVEM: writing—review and editing. JWAB: writing—review and editing. ARMB-K: writing—review and editing. G-JC: writing—review and editing. IHJTdH: writing—review and editing. ML: writing—review and editing. SB: writing—review and editing. EvM: writing—review and editing. SML: writing—review and editing. CV: writing—review and editing. BPLW: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, writing—review and editing. RHJM: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, writing—review and editing.

Footnotes

Niels A. D. Guchelaar and Bo J. Noordman share first-authorship.

Contributor Information

Niels A. D. Guchelaar, Email: n.guchelaar@erasmusmc.nl

Bo J. Noordman, Email: b.noordman@erasmusmc.nl

Stijn L. W. Koolen, Email: s.koolen@erasmusmc.nl

Bianca Mostert, Email: b.mostert@erasmusmc.nl.

Eva V. E. Madsen, Email: e.madsen@erasmusmc.nl

Jacobus W. A. Burger, Email: pim.burger@catharinaziekenhuis.nl

Alexandra R. M. Brandt-Kerkhof, Email: a.brandt-kerkhof@erasmusmc.nl

Geert-Jan Creemers, Email: geert-jan.creemers@catharinaziekenhuis.nl.

Ignace H. J. T. de Hingh, Email: ignace.d.hingh@catharinaziekenhuis.nl

Misha Luyer, Email: misha.luyer@catharinaziekenhuis.nl.

Sander Bins, Email: s.bins@erasmusmc.nl.

Esther van Meerten, Email: e.vanmeerten@erasmusmc.nl.

Sjoerd M. Lagarde, Email: s.lagarde@erasmusmc.nl

Cornelis Verhoef, Email: c.verhoef@erasmusmc.nl.

Bas P. L. Wijnhoven, Email: b.wijnhoven@erasmusmc.nl

Ron. H. J. Mathijssen, Email: a.mathijssen@erasmusmc.nl

References

- 1.Hartgrink HH, Jansen EPM, van Grieken NCT, van de Velde CJH. Gastric cancer. Lancet. 2009;374:477–490. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60617-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lengyel E. Ovarian cancer development and metastasis. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:1053–1064. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cortés-Guiral D, Hübner M, Alyami M, Bhatt A, Ceelen W, Glehen O, et al. Primary and metastatic peritoneal surface malignancies. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7:91. doi: 10.1038/s41572-021-00326-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanda M, Kodera Y. Molecular mechanisms of peritoneal dissemination in gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:6829–6840. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i30.6829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sadeghi B, Arvieux C, Glehen O, Beaujard AC, Rivoire M, Baulieux J, et al. Peritoneal carcinomatosis from non-gynecologic malignancies: results of the EVOCAPE 1 multicentric prospective study. Cancer. 2000;88:358–363. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000115)88:2<358::aid-cncr16>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gwee YX, Chia DKA, So J, Ceelen W, Yong WP, Tan P, et al. Integration of genomic biology into therapeutic strategies of gastric cancer peritoneal metastasis. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:2830. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.02745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franko J, Shi Q, Meyers JP, Maughan TS, Adams RA, Seymour MT, et al. Prognosis of patients with peritoneal metastatic colorectal cancer given systemic therapy: an analysis of individual patient data from prospective randomised trials from the Analysis and Research in Cancers of the Digestive System (ARCAD) database. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1709–1719. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30500-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rijken A, Lurvink RJ, Luyer MDP, Nieuwenhuijzen GAP, van Erning FN, van Sandick JW, et al. The burden of peritoneal metastases from gastric cancer: a systematic review on the incidence, risk factors and survival. J Clin Med. 2021;10:4882. doi: 10.3390/jcm10214882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kepenekian V, Bhatt A, Péron J, Alyami M, Benzerdjeb N, Bakrin N, et al. Advances in the management of peritoneal malignancies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022;19:698–718. doi: 10.1038/s41571-022-00675-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacquet P, Sugarbaker PH. Peritoneal-plasma barrier. Cancer Treat Res. 1996;82:53–63. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-1247-5_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Michael FF. The transport barrier in intraperitoneal therapy. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2005;288:F433–F442. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00313.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weisberger AS, Levine B, Storaasli JP. Use of nitrogen mustard in treatment of serous effusions of neoplastic origin. J Am Med Assoc. 1955;159:1704–1707. doi: 10.1001/jama.1955.02960350004002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flessner MF. The transport barrier in intraperitoneal therapy. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2005;288:F433–F442. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00313.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dedrick RL, Myers CE, Bungay PM, DeVita VT., Jr Pharmacokinetic rationale for peritoneal drug administration in the treatment of ovarian cancer. Cancer Treat Rep. 1978;62:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Quteimat OM, Al-Badaineh MA. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy: rationale, applications, and limitations. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2013;20:369–380. doi: 10.1177/1078155213506244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kobayashi D, Kodera Y. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy for gastric cancer with peritoneal metastasis. Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:111–121. doi: 10.1007/s10120-016-0662-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Averbach AM, Sugarbaker PH. Methodologic considerations in treatment using intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Cancer Treat Res. 1996;82:289–309. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-1247-5_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feingold PL, Klemen ND, Kwong MLM, Hashimoto B, Rudloff U. Adjuvant intraperitoneal chemotherapy for the treatment of colorectal cancer at risk for peritoneal carcinomatosis: a systematic review. Int J Hyperth. 2018;34:501–511. doi: 10.1080/02656736.2017.1401742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matharu G, Tucker O, Alderson D. Systematic review of intraperitoneal chemotherapy for gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2011;98:1225–1235. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gill RS, Al-Adra DP, Nagendran J, Campbell S, Shi X, Haase E, et al. Treatment of gastric cancer with peritoneal carcinomatosis by cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC: a systematic review of survival, mortality, and morbidity. J Surg Oncol. 2011;104:692–698. doi: 10.1002/jso.22017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Eelco B, Dimosthenis M, Dimitris S, John R, Odysseas Z. Pharmacological principles of intraperitoneal and bidirectional chemotherapy. Pleura Peritoneum. 2017;2:47–62. doi: 10.1515/pp-2017-0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marchetti C, De Felice F, Perniola G, Palaia I, Musella A, Di Donato V, et al. Role of intraperitoneal chemotherapy in ovarian cancer in the platinum–taxane-based era: a meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2019;136:64–69. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2019.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brandl A, Prabhu A. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy in the treatment of gastric cancer peritoneal metastases: an overview of common therapeutic regimens. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2021;12:S32–S44. doi: 10.21037/jgo-2020-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Bree E, Tsiftsis DD. Principles of perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal carcinomatosis. In: González-Moreno S, editor. Advances in peritoneal surface oncology. Berlin: Springer; 2007. pp. 39–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yan TD, Cao CQ, Munkholm-Larsen S. A pharmacological review on intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal malignancy. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010;2:109–116. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v2.i2.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Bree E, Tsiftsis DD. Experimental and pharmacokinetic studies in intraperitoneal chemotherapy: from laboratory bench to bedside. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2007;169:53–73. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-30760-0_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hasovits C, Clarke S. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of intraperitoneal cancer chemotherapeutics. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2012;51:203–224. doi: 10.2165/11598890-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Bree E, Rosing H, Michalakis J, Romanos J, Relakis K, Theodoropoulos PA, et al. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy with taxanes for ovarian cancer with peritoneal dissemination. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32:666–670. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Bree E, Theodoropoulos PA, Rosing H, Michalakis J, Romanos J, Beijnen JH, et al. Treatment of ovarian cancer using intraperitoneal chemotherapy with taxanes: from laboratory bench to bedside. Cancer Treat Rev. 2006;32:471–482. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sugarbaker PH. Intraperitoneal paclitaxel: pharmacology, clinical results and future prospects. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2021;12:S231–S239. doi: 10.21037/jgo-2020-03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Kooten JP, Dietz MV, Guchelaar NAD, Brandt-Kerkhof ARM, Koolen SLW, Burger JWA, et al. Intraperitoneal paclitaxel for patients with primary malignant peritoneal mesothelioma: a phase I/II dose escalation and safety study-INTERACT MESO. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e062907. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-062907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Markman M, Rowinsky E, Hakes T, Reichman B, Jones W, Lewis J, et al. Phase I trial of intraperitoneal taxol: a Gynecoloic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:1485–1491. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.9.1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Francis P, Rowinsky E, Schneider J, Hakes T, Hoskins W, Markman M. Phase I feasibility and pharmacologic study of weekly intraperitoneal paclitaxel: a Gynecologic Oncology Group pilot Study. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2961–2967. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.12.2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hofstra LS, Bos AME, de Vries EGE, van der Zee AGJ, Willemsen ATM, Rosing H, et al. Kinetic modeling and efficacy of intraperitoneal paclitaxel combined with intravenous cyclophosphamide and carboplatin as first-line treatment in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;85:517–523. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2002.6665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fushida S, Furui N, Kinami S, Ninomiya I, Fujimura T, Nishimura G, et al. Pharmacologic study of intraperitoneal paclitaxel in gastric cancer patients with peritoneal dissemination. Gan To Kaguku Ryoho. 2002;29:2164–2167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mohamed F, Marchettini P, Stuart OA, Yoo D, Sugarbaker PH. A comparison of hetastarch and peritoneal dialysis solution for intraperitoneal chemotherapy delivery. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2003;29:261–265. doi: 10.1053/ejso.2002.1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Markman M. Intraperitoneal taxol. In: Sugarbaker PH, editor. Peritoneal carcinomatosis: drugs and diseases. Boston: Springer US; 1996. pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuh HJ, Jang SH, Wientjes MG, Weaver JR, Au JL. Determinants of paclitaxel penetration and accumulation in human solid tumor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;290:871–880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cristea MC, Frankel P, Synold T, Rivkin S, Lim D, Chung V, et al. A phase I trial of intraperitoneal nab-paclitaxel in the treatment of advanced malignancies primarily confined to the peritoneal cavity. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2019;83:589–598. doi: 10.1007/s00280-019-03767-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Bree E, Rosing H, Beijnen JH, Romanos J, Michalakis J, Georgoulias V, et al. Pharmacokinetic study of docetaxel in intraoperative hyperthermic i.p. chemotherapy for ovarian cancer. Anticancer Drugs. 2003;14:103–110. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200302000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morgan RJ, Jr, Doroshow JH, Synold T, Lim D, Shibata S, Margolin K, et al. Phase I trial of intraperitoneal docetaxel in the treatment of advanced malignancies primarily confined to the peritoneal cavity: dose-limiting toxicity and pharmacokinetics. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:5896–5901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]