Abstract

Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD) involves non-episodic irritability and frequent severe temper outbursts in children. Since the inclusion of the diagnosis in the DSM-5, there is no established gold-standard in the assessment of DMDD. In this systematic review of the literature, we provide a synopsis of existing diagnostic instruments for DMDD. Bibliographic databases were searched for any studies assessing DMDD. The systematic search of the literature yielded K = 1167 hits, of which n = 110 studies were included. The most frequently used measure was the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia DMDD module (25%). Other studies derived diagnostic criteria from interviews not specifically designed to measure DMDD (47%), chart review (7%), clinical diagnosis without any specific instrument (6%) or did not provide information about the assessment (9%). Three structured interviews designed to diagnose DMDD were used in six studies (6%). Interrater reliability was reported in 36% of studies (ranging from κ = 0.6–1) while other psychometric properties were rarely reported. This systematic review points to a variety of existing diagnostic measures for DMDD with good reliability. Consistent reporting of psychometric properties of recently developed DMDD interviews, as well as their further refinement, may help to ascertain the validity of the diagnosis.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00787-021-01840-4.

Keywords: Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder, Irritability, Diagnostics, Measurement, Systematic review of the literature

Introduction

Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD) is a relatively new diagnosis, which has been introduced to the domain of depressive disorders in the fifth version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) in 2013 [1]. The diagnosis was endorsed by DSM-5 work groups to address concerns that children with pathological irritability and temper outbursts/anger were being inappropriately diagnosed with bipolar disorder [2]. The diagnosis of bipolar disorder did not accurately capture the non-episodic nature of those children’s symptoms and therefore, might have led to questionable treatment decisions [3]. The development of the DMDD diagnosis was based on the description of a broad phenotype of pediatric bipolar disorder called severe mood dysregulation (SMD) by Leibenluft and colleagues in 2003 [4]. In addition to irritability and anger, the latter required symptoms of chronic hyperarousal (e.g. agitation, distractibility, racing thoughts, insomnia, pressured speech or intrusiveness). Increasing evidence of the clinical distinction between episodic and non-episodic irritability and anger as well as distinct pathophysiology finally led to the formulation of the new diagnosis [2, 5–7].

DMDD involves non-episodic anger or irritability and frequent severe temper outbursts over a period of at least one year in pediatric patients aged 6–18 years [1]. Temper outbursts occur on average three or more times per week, can occur verbally or behaviorally (e.g. physical aggression towards objects or persons), their duration or intensity is inappropriate to the situation and they are inconsistent with the child’s developmental level. DMDD is characterized by persistent irritable and angry mood between temper outbursts in at least two of three settings (i.e. at home, at school, with peers). While the average age of onset is suggested to be 5 years of age [2], the diagnosis is assigned from age 6, as the identification of pathology before this age is difficult due to normal variations in preschool behavior [8].

The prevalence of DMDD ranges from 0.8% to 3.3%, with 2–3% in preschool children, 1–3% in 9–12 year-olds, and 0–0.12% in adolescents [9–11]. Although the prevalence of DMDD decreases with increasing age, individuals with a history of DMDD are at higher risk for adult depression and anxiety, adverse health outcomes, low educational attainment, poverty, and reported police contact, compared to healthy and clinical controls with other psychiatric conditions [11]. Prevalence estimates differ between studies because there is substantial diagnostic variability in the adherence to DSM-5 criteria with respect to the frequency of outbursts, the duration of irritability or the exclusion criteria.

Comorbidity is one of the obstacles which have been reported around the DMDD diagnosis [12]. The majority of patients with DMDD have at least one other comorbid psychiatric disorder, of which oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) or depressive disorders are most commonly reported [10]. In addition, there is substantial diagnostic overlap with childhood psychiatric disorders such as ODD, intermittent explosive disorder or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), questioning the validity of the diagnosis as a distinct disorder [13–15]. Correspondingly, in the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD‐11), DMDD will be listed as a subtype “with chronic irritability‐anger” of oppositional defiant disorder [16].

The diagnostic challenges may, at least in part, be due to difficulties in its assessment [17]. As such, symptoms of DMDD are not unique to children referred for psychiatric services. Hence, many existing measures provide questions which assess symptoms relevant to DMDD (e.g. irritability is measured but considered a nonspecific indicator and is related to several other psychiatric disorders) [12]. Moreover, structured interviews or questionnaires specifically developed to diagnose DMDD are still in their infancy. Consequently, there is currently no gold standard or broad consensus regarding the clinical assessment of DMDD.

In this systematic review of the literature, we aimed to provide a synopsis of all measures that have been used in diagnosing DMDD since the advent of the diagnosis in 2013. Study characteristics of the included studies, quantities of used diagnostic measures, and psychometric properties, where applicable, are reported and discussed. The results of this systematic review of the literature might guide future research in the selection of appropriate tools to diagnose DMDD in the clinical and research setting.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist [18]. The protocol was pre-registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) and may be accessed under the registration number CRD 42020165496.

Literature search

The goal of the literature search was to identify any studies assessing DMDD. Therefore, a broad search strategy was formulated. The full electronic search strategy of the systematic literature search in the PubMed database (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) was: ("Disruptive Mood Dysregulation*") OR ("DMDD"). No limits or filters were added to this search. PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, and Web of Science databases were scrutinized for relevant literature published from 2013 to 31st March 2020. We used identical search terms in all databases. Further, reference lists of publications identified through database search were screened for potentially pertinent studies not identified in the initial search. To reflect the broadest use of tools to diagnose DMDD, in research as well as in the clinic, we included any regular article, case report, or conference abstract published in any of the searched databases.

Study selection

Studies were excluded if they (a) did not include patients with diagnosed DMDD; or (b) a full text was not available. Prior to a full-text review, the titles, abstracts, and methods sections of the articles identified through database searches were screened for the eligibility criteria outlined above by two independent reviewers until consensus was reached.

Data extraction

A digital data extraction sheet was developed and refined during the data extraction process. The following data were extracted if available: general information and identifying features of the study, i.e., full reference, year of publication, and country of study origin. Additionally, the article type was identified, comprising regular articles, conference abstracts, or case reports. All article types were included to cover the full breadth of tools available for research and clinical purposes. Magnitudes and percentages of all outcome variables were given for all study types included as well as for abstracts only. Further data extracted comprised details on the study design, study population, sample size, and age range. The main outcome was the tool used to diagnose DMDD, including the rater (clinician, parent, self) and whether psychometric properties had been assessed. Where possible, information about the number of items, administration time, and availability of the tool (licensed vs. free of cost) in different languages was obtained. Authors were contacted to provide details if any of the information of interest was not provided in the study.

Results

Search results

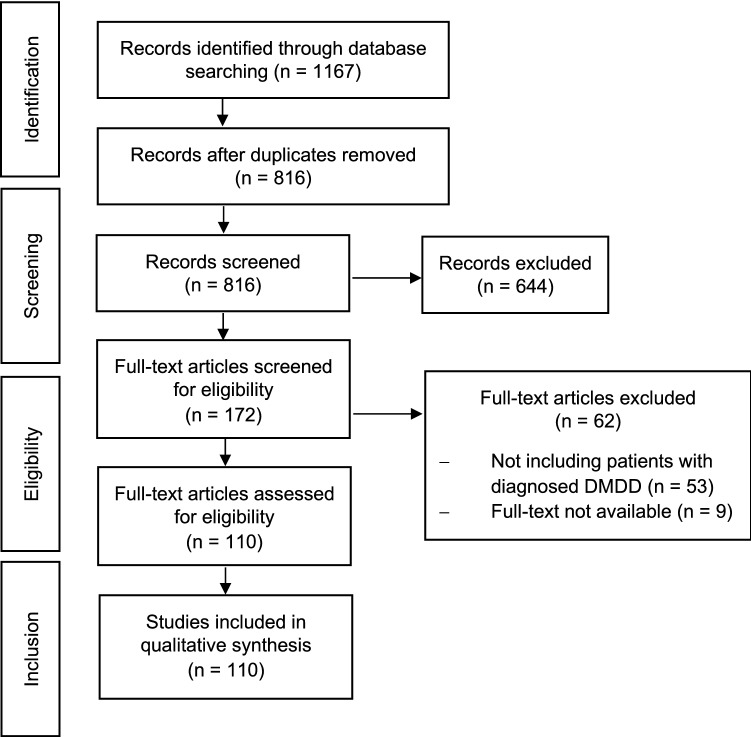

The first literature search, conducted on January 22, 2020, yielded K = 1149 records (PubMed k = 168, PsycINFO k = 471, Web of Science k = 201, Embase k = 309). Search updates identical to the first search were carried out on May 26, 2020, yielding an additional k = 18 records. K = 351 duplicates were removed from the K = 1167 records screened for eligibility. Of the k = 172 full-text articles screened for eligibility, a further k = 53 studies were excluded as they did not include patients with diagnosed DMDD and k = 9 because a full text was not obtainable. The PRISMA flow diagram of the full process of study selection is depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram depicting the study selection process

Included studies

From the initial base of records, k = 110 studies fulfilled all inclusion criteria and were retained for qualitative syntheses.

General study characteristics of the included studies are described in Table 1. Of the included studies, k = 58 were regular articles (52.7%), while there were k = 41 conference abstracts (37.3%) and k = 11 case reports (10.0%). Most of the studies included a clinical sample (k = 83, 75.5%; k = 36 abstracts, 32.7%), some were population-based (k = 12, 10.9%; k = 2 abstracts, 1.8%), case studies (k = 11, 10.0%; k = 0 abstracts), cohort studies (k = 3, 2.7%; k = 1 abstract, 0.9%) and k = 1 study was among youth in the juvenile justice setting (0.9%; k = 0 abstracts). K = 85 studies included unique samples (77.3%; k = 30 abstracts), while k = 25 articles (22.7%; k = 11 abstracts) reported data from overlapping samples (see Table 1 for details). K = 86 studies were conducted prospectively (78.2%; k = 35 abstracts, 31.8%) and k = 24 retrospectively (21.8%; k = 7 abstracts, 6.4%). Among the prospective studies, k = 7 assessed DMDD retrospectively (6.4%; k = 1 abstracts, 0.9%).

Table 1.

Study characteristics by year of publication

| Authors | Year | Country of origin | Article type | Study type | Study design | Sample | N (% female) | Age (range)5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copeland et al. [10] | 2013 | USA | Regular article | Population-based | Prospective | Community | 3258 (50) | 2–17 |

| Copeland et al. [11] | 2014 | USA | Regular article | Population-based | Prospective2 | Population | 1420 (47) | 10–25 |

| Dougherty et al. [54] | 2014 | USA | Regular article | Population-based | Prospective | Community | 462 (46) | 6 |

| Parmar et al. [55] | 2014 | USA | Case report | Case study | Retrospective | Outpatients | 1 (0) | 15 |

| Roy et al. [43] | 2014 | USA | Case report | Case study | Retrospective | Outpatients | 1 (0) | 8 |

| Sparks et al. [56] | 2014 | USA | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective2 | Outpatients and community controls | 616 (NA) | 6–17 |

| Deveney et al. [57] | 2015 | USA | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective2 | Outpatients | 194 (35) | 7–17 |

| Estrada Prat et al. [58] | 2015 | Spain | Conference abstract | Clinical | Prospective | Outpatients | 8 (25) | 7–18 |

| Mitchell et al.a [59] | 2015 | Canada | Conference abstract | Clinical | Prospective | Outpatients | 116 (NA) | NA |

| Schilpzand et al.b [60] | 2015 | Australia | Conference abstract | Clinical | Prospective | patients | 179 (31) | 6–8 |

| Stoddard et al. [61] | 2015 | USA | Conference abstract | Clinical | Prospective | patients and healthy controls | 89 (48)4 | 8–18 |

| Tseng et al. [62] | 2015 | USA | Conference abstract | Clinical | Prospective | patients and healthy controls | 75 (53) | 8–18 |

| Uran et al.c [63] | 2015 | Turkey | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective | Outpatients and healthy controls | 99 (51) | 7–18 |

| Uran et al.c [64] | 2015 | Turkey | Conference abstract | Clinical | Prospective | patients and healthy controls | 99 (51) | 7–18 |

| Althoff et al. [9] | 2016 | USA | Regular article | Population-based | Prospective | Population | 6483 (51) | 13–18 |

| Averna et al. [65] | 2016 | Italy | Case report | Case study | Retrospective | Outpatient | 1 (0) | 11 |

| Baweja et al. [66] | 2016 | USA | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective2 | Outpatients | 38 (28) | 7–12 |

| Brotman et al. [67] | 2016 | USA | Conference abstract | Clinical | Prospective | Patients and healthy controls | 110 (45) | 9–19 |

| Carlson et al. [68] | 2016 | USA | Conference abstract | Clinical | Prospective | Community | 36 (56) | 6, 9 and 12 |

| Copeland et al. [37] | 2016 | USA | Conference abstract | Clinical | Prospective2 | Community | 112 (NA) | M 11.4 |

| Dougherty et al.d [69] | 2016 | USA | Regular article | Population-based | Prospective | Population | 473 (46) | 3 6 and 9 |

| Freeman et al. [70] | 2016 | USA | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective2 | Outpatients | 597 (39) | 6–18 |

| Fristad et al. [71] | 2016 | USA | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective | Patients | 217 (38) | 6–12 |

| Gold et al. [72] | 2016 | USA | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective | Community, outpatients and healthy controls | 184 (40) | 8–19 |

| Kessel et al. [39] | 2016 | USA | Regular article | Population-based | Prospective | Community | 373 (45) | 9 |

| Kilic et al. [73] | 2016 | Turkey | Case report | Case study | Retrospective | Outpatient | 1 (0) | 18 |

| Mitchell et al.a [74] | 2016 | Canada | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective | Outpatients | 108 (68) | 13–19 |

| Mulraney et al.b [75] | 2016 | Australia | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective | Community | 179 (25) | 6–8 |

| Pogge et al. [76] | 2016 | USA | Conference abstract | Clinical | Prospective | Inpatients | 100 (NA) | 6–12 |

| Stoddard et al. [77] | 2016 | USA | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective | Patients and healthy controls | 89 (48)3 | 8–18 |

| Stoddarde [78] | 2016 | USA | Conference abstract | Clinical | Prospective | Patients and healthy Controls | 115 (44) | 8–17 |

| Taskiran et al. [79] | 2016 | Turkey | Conference abstract | Clinical | Prospective | Outpatients | 29 (NA) | M 9.2 |

| Tiwari et al. [80] | 2016 | India | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective | Inpatients | 70 (24) | 6–16 |

| Topal et al.f [81] | 2016 | Turkey | Conference abstract | Clinical | Prospective | Outpatients | 90 (48) | 12–16 |

| Topal et al.f [82] | 2016 | Turkey | Conference abstract | Clinical | Prospective | Offspring of parents with mood disorder | 87 (43) | 12–16 |

| Tudor et al. [83] | 2016 | USA | Case report | Case study | Retrospective | Patients | 1 (100) | 9 |

| Tufan et al. [84] | 2016 | Turkey | Regular article | Clinical | Retrospective | Outpatients | 403 (NA) | 6–17 |

| Wiggins et al. [41] | 2016 | USA | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective | Outpatients and healthy controls | 71 (40) | 9–21 |

| Alexander et al. [85] | 2017 | USA | Conference abstract | Population-based | Prospective | Population | 500 (NA) | 5–21 |

| Dougherty et al.d [86] | 2017 | USA | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective | Community | 329 (51) | 6 and 9 |

| Estrada Prat et al. [87] | 2017 | Spain | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective | Patients | 35 (33) | 6–18 |

| Eyre et al.g [88] | 2017 | UK | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective | Patients | 696 (16) | 6–18 |

| Faheem et al. [89] | 2017 | USA | Regular article | Clinical | Retrospective | Inpatients | 490 (NA) | 6–18 |

| Higdon et al. [90] | 2017 | USA | Conference abstract | Clinical | Prospective | Overweight patients | 438 (52) | 7–19 |

| Jain [91] | 2017 | India | Conference abstract | Clinical | Prospective | Patients | 25 (12) | 6–9 |

| Jalnapurkar et al. [92] | 2017 | USA | Conference abstract | Clinical | Prospective | Inpatients | 95 (NA) | 8–17 |

| Kircanski et al.h [93] | 2017 | USA | Conference abstract | Clinical | Prospective | Outpatients | 197 (46) | 8–18 |

| Kircanski et al.h [94] | 2017 | USA | Conference abstract | Clinical | Prospective | Outpatients and healthy controls | 199 (54) | 8–18 |

| Le et al. [95] | 2017 | USA | Conference abstract | Clinical | Retrospective | Patients | 7268 (NA) | < 18 |

| Martin et al. [96] | 2017 | USA | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective | Outpatients | 139 (25) | 4–5 |

| Matthews et al. [97] | 2017 | USA | Conference abstract | Clinical | Prospective | Previous inpatients | 91 (43) | 6–17 |

| McTate et al. [53] | 2017 | USA | Case report | Case study | Prospective | Outpatient | 1 (100) | 9 |

| Mitchell et al. [98] | 2017 | Australia | Conference abstract | Clinical | Prospective | Youth at familial risk of BD and controls | 242 (NA) | 12–30 |

| Munhoz et al.i [99] | 2017 | Brazil | Regular article | Cohort study | Prospective | Birth cohort (Pelotas study) | 3490 (48) | 11 |

| Özyurt et al. [100] | 2017 | Turkey | Regular article | Clinical | Retrospective | Outpatients | 12 (0) | 8–17 |

| Pagliaccio et al. [101] | 2017 | USA | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective | Patients and healthy controls | 83 (48) | 8–18 |

| Perepletchikova et al. [102] | 2017 | USA | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective | Community and outpatients | 43 (44) | 7–12 |

| Perhamus et al. [103] | 2017 | USA | Conference abstract | Clinical | Prospective | Patients and healthy controls | 120 (45) | 8–18 |

| Propper et al. [104] | 2017 | Canada | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective | Offspring of parents with BD or MDD | 180 (53) | 6–18 |

| Ramires et al. [105] | 2017 | Brazil | Case report | Case study | Retrospective | Outpatients | 1 (0) | 7 |

| Stoddard et al.e [106] | 2017 | USA | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective | patients | 115 (44) | 8–17 |

| Stoddard et al. [107] | 2017 | USA | Conference abstract | Clinical | Prospective | Patients and healthy controls | 42 (42) | 8–21 |

| Swetlitz et al. [108] | 2017 | USA | Conference abstract | Clinical | Prospective | Outpatients and healthy controls | 48 (58) | 8–17 |

| Taskiran et al.j [109] | 2017 | Turkey | Conference abstract | Clinical | Prospective | Patients and healthy controls | 43 (NA) | M 9.5 |

| Taskiran et al.j [110] | 2017 | Turkey | Conference abstract | Clinical | Prospective | Patients and healthy controls | 43 (NA) | NA |

| Tseng et al.k [111] | 2017 | USA | Conference abstract | Clinical | Prospective | Patients and healthy controls | 197 (59) | 8–18 |

| Waxmonsky et al. [112] | 2017 | USA | Conference abstract | Clinical | Retrospective | Outpatients | 56 (29) | 7–12 |

| Abouzed et al. [113] | 2018 | Egypt | Conference abstract | Clinical | Prospective | Offspring of parents with ADHD and healthy controls | 212 (NA) | 6–18 |

| Bryant et al. [114] | 2018 | USA | Conference abstract | Clinical | Retrospective | Patients | 360 (29) | 4–17 |

| Cuffe et al. [115] | 2018 | USA | Conference abstract | Population-based | Prospective | Student population | 292 (48) | 5–17 |

| de la Peña et al. [38] | 2018 | Latin America1 | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective | Outpatients | 80 (40) | 6–18 |

| Delaplace et al. [116] | 2018 | France | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective | Outpatients | 21 (10) | 9–15 |

| Fridson et al. [117] | 2018 | USA | Conference abstract | Clinical | Retrospective | Patients | 839 (NA) | 6–18 |

| Grau et al. [36] | 2018 | Germany | Regular article | Population-based | Prospective | Population | 2413 (NA) | 18–94 |

| Kircanski et al.h [118] | 2018 | USA | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective | Community | 197 (46) | 8–18 |

| Miller et al. [119] | 2018 | USA | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective | outpatients | 19 (42) | 12–17 |

| Mroczkowski et al. [120] | 2018 | USA | Regular article | Juvenile justice | Retrospective | Juvenile justice involved youths | 2266 (30) | 8–18 |

| Pan et al. [121] | 2018 | Taiwan | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective | Outpatients | 58 (17) | 7–17 |

| Sagar-Ouriaghli et al. [122] | 2018 | Great Britain | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective2 | Outpatients | 117 (NA) | 6–12 |

| Vidal-Ribas et al. [123] | 2018 | USA | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective | Outpatients and healthy controls | 116 (38) | 8–20 |

| Walyzada et al. [124] | 2018 | USA | Conference abstract | Clinical | Retrospective | Outpatients | 1088 (46) | NA |

| Wiggins et al. [125] | 2018 | USA | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective | Outpatients | 425 (51) | 3–5 |

| Winters et al. [126] | 2018 | USA | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective | Patients | 22 (31) | 9–15 |

| Basu et al. [127] | 2019 | Australia | Regular article | Clinical | Retrospective | Patients | 101 (58) | 6–12 |

| Benarous et al. [128] | 2019 | France | Case report | Case study | Retrospective | Inpatients | 6 (30) | 10–14 |

| Benarous et al. [129] | 2019 | France | Conference abstract | Clinical | Retrospective | Outpatients | 163 (40) | 7–17 |

| Chen et al. [130] | 2019 | Taiwan | Regular article | Population-based | Prospective | Population | 4816 (48) | 10–17 |

| Eyre et al.g [131] | 2019 | UK | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective | Patients | 696 (16) | 6–18 |

| Guilé [132] | 2019 | France | Conference abstract | Clinical | Prospective | Patients and healthy controls | 21 (100) | M 11.7 ± 3 SD |

| Haller et al. [133] | 2019 | USA | Conference abstract | Clinical | Prospective | Patients and healthy controls | 44 (43) | 8–17 |

| Ignaszewski et al. [134] | 2019 | USA | Case report | Case study | Retrospective | Outpatient | 1 (0) | 14 |

| Linke et al. [135] | 2019 | USA | Case report | Case study | Retrospective | Outpatient | 1 (0) | 11 |

| Linke et al. [136] | 2019 | USA | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective | Patients and healthy controls | 118 (46) | 11–21 |

| Mulraney et al. [137] | 2019 | Australia | Conference abstract | Cohort study | Prospective | Patients | 134 (28) | 7–10 |

| Rice et al. [138] | 2019 | USA | Case report | Case study | Retrospective | Inpatient | 1 (100) | 12 |

| Towbin et al. [139] | 2019 | USA | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective | Patients | 53 (36) | 7–17 |

| Tseng et al.k [140] | 2019 | USA | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective | Patients and healthy controls | 195 (50) | 8–18 |

| Tüğen et al. [141] | 2019 | Turkey | Regular article | Population-based | Prospective | Community | 356 (55) | 6–11 |

| Ünal et al. [40] | 2010 | Turkey | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective | Outpatients | 120 (49) | 6–17 |

| Alexander et al. [27] | 2020 | USA | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective | Community | 523 (41) | 6–17 |

| Benarous et al. [142] | 2020 | France | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective | Patients | 30 (29) | 6–16 |

| Benarous et al. [143] | 2020 |

France, Canada |

Regular article | Clinical | Retrospective | outpatients | 163 (43) | 7–27 |

| Chang et al. [144] | 2020 | Taiwan | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective | Patients | 101 (31) | 7–18 |

| Cimino et al. [145] | 2020 | Italy | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective | Patients and healthy controls | 150 (48) | 8–9 |

| Haller et al. [146] | 2020 | USA | Conference abstract | Clinical | Prospective | Patients | 189 (34) | M 13.1 |

| Haller et al. [147] | 2020 | USA | Regular article | Clinical | Prospective | Patients | 98 (41) | 7–17 |

| Johnstone et al. [148] | 2020 | USA | Regular article | Clinical | Retrospective | Patients | 168 (23) | 6–12 |

| Laporte et al.i [45] | 2020 | Brazil | Regular article | Cohort study | Prospective | Birth cohort (Pelotas study) | 3562 (NA) | 10–12 |

| Le et al. [149] | 2020 | USA | Regular article | Population-based | Retrospective | Patients covered by Medicaid | 814,919 (49) | < 18 |

| Tseng et al. [150] | 2020 | USA | Conference abstract | Clinical | Prospective | Patients | 69 (NA) | M 14.5 |

DMDD disruptive mood dysregulation disorder, ADHD attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, ODD oppositional defiant disorder, BD bipolar disorder, SMD severe mood dysregulation, MDD major depressive disorder. NA information not available

aMitchell et al. (2015) and (2016) report data from overlapping samples

bSchipzand et al. (2015) and Mulraney et al. (2016) report data from overlapping samples

cUran et al. (2015) abstract and regular article report on same data

d Dougherty et al. (2016) and (2017) partly report on overlapping data

eStoddard et al. (2016) and (2017) report on overlapping data

f Topal et al. (2016) abstracts report data from overlapping samples

gEyre et al. (2017) and (2019) report on overlapping data

hKircanski et al. (2017) and (2018) report on overlapping data

iMunhoz et al. (2017) and Laporte et al. (2020) report on overlapping data

jTaskiran et al. (2017) abstracts report on overlapping data

kTseng et al. (2017) and (2019) report on overlapping data

1Mexico, Colombia, Chile, and Uruguay

2DMDD diagnosis was obtained retrospectively

3Where not otherwise specified, patients were in- and outpatients

4Experiment 1

5Mean (M) is given, where no information about range was available

There was an initial increase in numbers of publications from 2013 until 2017, after which numbers dropped again: k = 1 study in 2013 (0.9%; k = 0 abstracts), k = 5 in 2014 (4.5%; k = 0 abstracts), k = 8 in 2015 (7.3%; k = 6 abstracts, 5.5%), k = 24 in 2016 (21.8%; k = 7 abstracts, 6.4%), k = 29 in 2017 (26.4%; k = 16 abstracts, 14.5%), k = 16 in 2018 (14.5%; k = 5 abstracts, 4.5%), and k = 16 in 2019 (14.5%; k = 4 abstracts, 3.6%) and k = 11 in 2020 (10.0%; k = 2 abstracts, 1.8%).

Most of the included studies stem from the United States of America (k = 66, 60.0%; k = 26 abstracts, 23.6%). Other countries of origin include Turkey (k = 12, 10.9%; k = 6 abstracts, 5.5%), France (k = 6, 5.5%; k = 2 abstracts, 1.8%), Australia (k = 5, 4.5%; k = 3 abstracts, 2.7%), Brazil (k = 3, 2.7%; k = 0 abstracts), Canada (k = 3, 2.7%; k = 1 abstracts), United Kingdom (k = 3, 2.7%; k = 0 abstracts), Taiwan (k = 3, 2.7%; k = 0 abstracts), India (k = 2, 1.8%; k = 1 abstract), Spain (k = 2, 1.8%; k = 1 abstract), Italy (k = 2, 1.8%; k = 0 abstracts), Egypt (k = 1, 0.9%; k = 1 abstract) and Germany (k = 1, 0.9%; k = 0 abstracts). K = 1 regular article includes data from Mexico, Colombia, Chile, and Uruguay (0.9%).

Most study samples consisted of patients (in- and/or outpatients) k = 85 (77.3%; k = 33 abstracts, 30.0%). Of those, some reported to include only outpatients (n = 39, 35.5%; k = 10 abstracts, 9.1%), or inpatients (n = 7, 6.4%; k = 3 abstracts, 2.7%). Further, study samples consisted of community (n = 10, 9.1%; k = 2 abstracts, 1.8%), population (n = 7, 6.4%; k = 2 abstracts, 1.8%), youth at familial risk of psychiatric disorders (n = 4, 3.6%; k = 3 abstracts, 2.7%) birth cohorts (n = 2, 1.8%; k = 0 abstracts), juvenile justice involved youths (n = 1, 0.9%; k = 0 abstracts), and overweight patients (n = 1, 0.9%, k = 1 abstract). Many of the studies further examined healthy controls in addition to a patient group (n = 26, 23.6%). Sample sizes ranged from k = 1 in case-reports to k = 6483 in a large population-based study. Examined ages lay between 2 and 94 years of age, while most samples’ ages ranged from early school-age to adolescence or young adulthood.

Measurement of DMDD diagnosis

A variety of instruments were used to diagnose DMDD in the included studies. The instrument used most often was the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia Present and Lifetime Version, K-SADS-PL [19] (n = 48, 43.6%; k = 20 abstracts, 18.2%) in combination with the DMDD module (Table 2), k = 27 (24.5%; k = 12 abstracts, 10.9%). The Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment, PAPA [20] was used in k = 7 studies (6.4%; k = 1 abstracts, 0.9%), of which k = 4 did so in combination with ODD and depression sections. In k = 3 (2.7%) studies each, the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment, CAPA [21] (n = 0 abstracts), the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, Version IV, DISC-IV [22] (n = 1 abstract, 0.9%), and the Washington University in St. Louis Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia, WASH-U-K-SADS [23] (n = 1 abstract, 0.9%) were used. In k = 2 studies (1.8%) each, the Breton, Bergeron and Labelle DMDD Scale [24] (n = 1 abstract, 0.9%), the Conners rating scales [25] (n = 1 abstract, 0.9%), the Development and Well-Being Assessment, DAWBA [26] and the Extended Strengths and Weaknesses Assessment of Normal Behavior, E‐SWAN [27] (n = 1 abstracts, 0.9%) were used. Instruments used in k = 1 (0.9%) regular articles each included the Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventory, CASI [28], the Child Behavior Check List dysregulation profile, CBCL-DP [29], the Children’s Interview for Psychiatric Syndromes, ChIPS [30] in combination with the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents, MINI-KID [31], the Composite International Diagnostic Interview CIDI [32], the Diagnostic Infant and Preschool Assessment, DIPA [33], the Mandarin Version of the K-SADS-Epidemiological Version for DSM-5, K-SADS-E [34], the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, SCID-IV [35], a self-created set of six questions [36], and the Voice Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, V-DISC [22]. A not otherwise specified structured interview was reported in k = 1 conference abstract [37].

Table 2.

Measurement of DMDD in studies included in the systematic review, by tool

| Authors | Year | Main diagnostic DMDD measure | Additional measures or specifications | Rater | Were psychometric properties for DMDD measure assessed in this study?a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benarous et al. [128] | 2019 | K-SADS-PL | DMDD module | Clinician | No |

| Benarous et al. [142] | 2020 | K-SADS-PL | DMDD module | Clinician | No |

| Brotman et al. [67] | 2016 | K-SADS-PL | DMDD module | Clinician | Raters trained to IRR, κ ≥ 0.9; ICCs ≥ .9 differentiating DMDD module from mania/hypomania |

| Gold et al. [72] | 2016 | K-SADS-PL | DMDD module | Clinician | Raters trained to IRR, κ ≥ 0.9; ICCs ≥ .9 differentiating DMDD module from mania/hypomania |

| Haller et al. [133] | 2019 | K-SADS-PL | DMDD module | Clinician | Raters trained to IRR, κ ≥ 0.9; ICCs ≥ .9 differentiating DMDD module from mania/hypomania |

| Haller et al | 2020 | K-SADS-PL | DMDD module | Clinician | No |

| Kircanski et al. [93, 94] | 2017 | K-SADS-PL | DMDD module | Clinician | Raters trained to IRR, κ ≥ 0.9; ICCs ≥ .9 differentiating DMDD module from mania/hypomania |

| Kircanski et al. [118] | 2018 | K-SADS-PL | DMDD module | Clinician | Raters trained to IRR, κ ≥ 0.9; ICCs ≥ .9 differentiating DMDD module from mania/hypomania |

| Kircanski et al. [93, 94] | 2017 | K-SADS-PL | DMDD module | Clinician | Raters trained to IRR, κ ≥ 0.9; ICCs ≥ .9 differentiating DMDD module from mania/hypomania |

| Linke et al. [135] | 2019 | K-SADS-PL | DMDD module | Clinician | Raters trained to IRR, κ ≥ 0.9; ICCs ≥ .9 differentiating DMDD module from mania/hypomania |

| Linke et al. [136] | 2019 | K-SADS-PL | DMDD module | Clinician | Raters trained to IRR, κ ≥ 0.9; ICCs ≥ .9 differentiating DMDD module from mania/hypomania |

| Pagliaccio et al. [101] | 2017 | K-SADS-PL | DMDD module | Clinician | Raters trained to IRR, κ ≥ 0.9; ICCs ≥ .9 differentiating DMDD module from mania/hypomania |

| Perepletchikova et al. [102] | 2017 | K-SADS-PL | DMDD module | Clinician | No |

| Propper et al. [104] | 2017 | K-SADS-PL | DMDD module | Clinician | No |

| Stoddard et al. [77] | 2016 | K-SADS-PL | DMDD module | Clinician | Raters trained to IRR, κ ≥ 0.9; ICCs ≥ .9 differentiating DMDD module from mania/hypomania |

| Swetlitz et al. [108] | 2017 | K-SADS-PL | DMDD module | Clinician | Raters trained to IRR, κ ≥ 0.9; ICCs ≥ .9 differentiating DMDD module from mania/hypomania |

| Tseng et al. [62] | 2015 | K-SADS-PL | DMDD module | Clinician | Raters trained to IRR, κ ≥ 0.9; ICCs ≥ .9 differentiating DMDD module from mania/hypomania |

| Tseng et al. [111] | 2017 | K-SADS-PL | DMDD module | Clinician | Raters trained to IRR, κ ≥ 0.9; ICCs ≥ .9 differentiating DMDD module from mania/hypomania |

| Tseng et al. [140] | 2019 | K-SADS-PL | DMDD module | Clinician | Raters trained to IRR, κ ≥ 0.9; ICCs ≥ .9 differentiating DMDD module from mania/hypomania |

| Tudor et al. [83] | 2016 | K-SADS-PL | DMDD module | Clinician | NA |

| Vidal-Ribas et al. [123] | 2018 | K-SADS-PL | DMDD module | Clinician | Raters trained to IRR, κ ≥ 0.9; ICCs ≥ .9 differentiating DMDD module from mania/hypomania |

| Perhamus et al. [103] | 2017 | K-SADS-PL | DMDD module | Clinician | Raters trained to IRR, κ ≥ 0.9; ICCs ≥ .9 differentiating DMDD module from mania/hypomania |

| Stoddard [78] | 2016 | K-SADS-PL | DMDD module | Clinician | Raters trained to IRR, κ ≥ 0.9; ICCs ≥ .9 differentiating DMDD module from mania/hypomania |

| Stoddard et al. [61] | 2015 | K-SADS-PL | DMDD module | Clinician | Raters trained to IRR, κ ≥ 0.9; ICCs ≥ .9 differentiating DMDD module from mania/hypomania |

| Stoddard et al. [106] | 2017 | K-SADS-PL | DMDD module | Clinician | Raters trained to IRR, κ ≥ 0.9; ICCs ≥ .9 differentiating DMDD module from mania/hypomania |

| Stoddard et al. [107] | 2017 | K-SADS-PL | DMDD module | Clinician | Raters trained to IRR, κ ≥ 0.9; ICCs ≥ .9 differentiating DMDD module from mania/hypomania |

| Tüğen et al. [141] | 2019 | K-SADS-PL | Considering changes based on DSM-5; CBCL as a pre-screening | Clinician | No |

| Sagar-Ouriaghli et al. [122] | 2018 | K-SADS-PL | Elaborate system of filters to check all DSM-5 criteria | Clinician | NA |

| Freeman et al. [70] | 2016 | K-SADS-PL | Mood modules from WASH-U-KSADS; retrospective rating based on DSM-5 criteria | Clinician | No |

| Estrada Prat et al. [87] | 2017 | K-SADS-PL | ODD module | Clinician | No |

| Mitchell et al. [59] | 2015 | K-SADS-PL | ODD module and narrative summaries | Clinician | No |

| Mitchell et al. [74] | 2016 | K-SADS-PL | ODD module as well as narrative summaries (for DMDD criteria A-G) | Clinician | No |

| Winters et al. [126] | 2018 | K-SADS-PL | Querying parent and child about DMDD criteria posted on the DSM-5 website | Clinician | No |

| Deveney et al. [57] | 2015 | K-SADS-PL | Retrospectively applied DMDD criteria to prospectively obtained K-SADS-PL SMD module | Clinician | Raters trained to IRR, κ ≥ 0.9; ICCs ≥ .9 differentiating DMDD module from mania/hypomania |

| Topal et al. [81] | 2016 | K-SADS-PL | Screening of DSM-5 criteria | Clinician | Inter-rater agreement for DMDD symptoms and diagnosis was high, Tau = 0.76, p = 0.00 |

| Topal et al. [82] | 2016 | K-SADS-PL | SMD module and screening for DSM-5 criteria | Clinician | Inter-rater agreement for DMDD symptoms and diagnosis was high, Tau = 0.76, p = 0.00 |

| Estrada-Prat et al. [58] | 2015 | K-SADS-PL | SMD module | Clinician | No |

| Miller et al. [119] | 2018 | K-SADS-PL | SMD module | Clinician | No |

| Mitchell et al. [98] | 2017 | K-SADS-PL | SMD module | Clinician | NA |

| Özyurt et al. [100] | 2017 | K-SADS-PL | SMD module | Clinician | No |

| Towbin et al. [139] | 2019 | K-SADS-PL | SMD module | Clinician | Raters trained to IRR, κ ≥ 0.9; ICCs ≥ .9 differentiating DMDD module from mania/hypomania |

| Uran et al. [63] | 2015 | K-SADS-PL | SMD module | Clinician | NA |

| de la Peña et al. [38] | 2018 | K-SADS-PL | Spanish version modified under the DSM-5 criteria | Clinician | Cronbach's alpha for DMDD = 0.92 |

| Roy et al. [43] | 2014 | K-SADS-PL | Teacher rating scales | Clinician | NA |

| Abouzed et al. [113] | 2018 | K-SADS-PL | Clinician | NA | |

| Higdon et al. [90] | 2017 | K-SADS-PL | Clinician | No | |

| Uran et al. [64] | 2015 | K-SADS-PL | Clinician | NA | |

| Ünal et al. [40] | 2019 | K-SADS-PL-DSM-5-T | Turkish adaptation of K-SADS-PL including DMDD module | Clinician | IRR κ = 0.63; consensus validity 96% consensus, κ = 0.70; concurrent validity with ARI |

| Wiggins et al. [41] | 2016 | K-SADS | In youths under age 18; SCID-III-R in youths over age 18, with the DMDD module | Clinician | Raters trained to IRR, κ ≥ 0.9; ICCs ≥ .9 differentiating DMDD module from mania/hypomania |

| Taskiran et al. [109, 110] | 2017 | K-SADS | Clinician | NA | |

| Cimino et al. [145] | 2020 | Clinical diagnosis | Based on DSM-5 criteria | Clinician | No |

| Le et al. [95] | 2017 | Clinical diagnosis | Based on DSM-5 criteria | Clinician | No |

| Pan et al. [121] | 2018 | Clinical diagnosis | Based on DSM-5 criteria | Clinician | No |

| Tiwari et al. [80] | 2016 | Clinical diagnosis | Based on DSM-5 criteria | Clinician | No |

| Ignaszewski et al. [134] | 2019 | Clinical diagnosis | Based on parent and child report and behavior seen longitudinally across course of treatment | Clinician | No |

| Ramires et al. [105] | 2017 | Clinical diagnosis | Parent and child interviews, CBCL, Rorschach method, teacher report form | Clinician | No |

| Bryant et al. [114] | 2018 | Clinical diagnosis | Retrospective based on medical records | Clinician | No |

| Rice et al. [138] | 2019 | Clinical diagnosis | Clinician | No | |

| Benarous et al. [129] | 2019 | Chart review | Checklist for symptoms of temper dysregulation disorder with dysphoria | Clinician | No |

| Benarous et al. [143] | 2020 | Chart review | Checklist for symptoms of temper dysregulation disorder with dysphoria | Clinician | No |

| Pogge et al. [76] | 2016 | Chart review | Checklist of the variables corresponding to DSM-5 criteria | Clinician | NA |

| Fridson et al. [117] | 2018 | Chart review | electronic medical record review | Clinician | NA |

| Basu et al. [127] | 2019 | Chart review | Self-created symptom check list | Clinician | No |

| Faheem et al. [89] | 2017 | Chart review | Clinician | No | |

| Walyzada et al. [124] | 2018 | Chart review | Clinician | No | |

| Dougherty et al. [86] | 2017 | PAPA | K-SADS-PL after age 6 | Clinician | IRR for all diagnoses and symptom scales κ = 0.64–0.89; ICC = 0.71–0.97 |

| Carlson et al. [68] | 2016 | PAPA | K-SADS-PL at age 9 and 12 | Clinician | NA |

| Wiggins et al. [125] | 2018 | PAPA | K-SADS-PL in a subset of reassessed children | Clinician | κ = 0.83 to 1.00 on all interviews |

| Copeland et al. [10] | 2013 | PAPA | ODD and depression sections | Clinician | NA |

| Dougherty et al. [54] | 2014 | PAPA | ODD and depression sections | Clinician | IRR for all diagnoses and symptom scales κ = 0.64–0.89; ICC = 0.71–0.97 |

| Dougherty et al. [69] | 2016 | PAPA | ODD and depression sections | Clinician | IRR for all diagnoses and symptom scales κ = 0.64–0.89; ICC = 0.71–0.97 |

| Kessel et al. [39] | 2016 | PAPA | ODD and depression sections | Clinician | ICC for dimensional lifetime psychopathology symptom scores ranged from 0.86 to 0.97. Cronbach's alpha = 0.75 |

| Copeland et al. [11] | 2014 | CAPA | Conduct problems and depression sections | Clinician | NA |

| Eyre et al. [88] | 2017 | CAPA | ODD and depression sections | Clinician | Raters trained to IRR, κ ≥ 0.9; ICCs ≥ .9 differentiating DMDD module from mania/hypomania |

| Eyre et al. [131] | 2019 | CAPA | ODD and depression sections | Clinician | Raters trained to IRR, κ ≥ 0.9; ICCs ≥ .9 differentiating DMDD module from mania/hypomania |

| Mulraney et al. [75] | 2016 | DISC-IV | ODD and MDD modules | Clinician | No |

| Schilpzand et al. [60] | 2015 | DISC-IV | ODD and MDD modules | Clinician | No |

| Cuffe et al. [115] | 2018 | DISC-IV | Three study stages: 1. Screening 2. DISC-IV and 3. K-SADS-PL | Clinician | No |

| Fristad et al. [71] | 2016 | WASH-U-KSADS | ODD supplement | Clinician | No |

| Waxmonsky et al. [112] | 2017 | WASH-U-KSADS | Disruptive Behavior Disorders Structured Parent Interview | Clinician | IRR κ > 0.9 |

| Baweja et al. [66] | 2016 | WASH-U-KSADS | Disruptive Behavior Disorders Structured Parent Interview | Clinician | No |

| Guilé [132] | 2019 | Breton, Bergeron & Labelle DMDD Scale | Self- and informant-based questionnaire | Self-rating | No |

| Delaplace et al. [116] | 2018 | Breton, Bergeron & Labelle DMDD Scale | Self- and informant-based questionnaire, and K-SADS-PL with DMDD module | Self-rating/clinician | NA |

| Tufan et al. [84] | 2016 | Conners | 8th (ready to pick up a fight, quick to anger) and 21st (is cranky and sullen) items and further details from screening instruments; subset of patients' caregivers interviewed about DMDD symptoms via phone | Clinician | κ = 0.68 |

| Mulraney et al. [137] | 2019 | Conners | DISC-IV | Clinician | No |

| Laporte et al. [45] | 2020 | DAWBA | DMDD section | Clinician | NA |

| Munhoz et al. [99] | 2017 | DAWBA | DMDD section | Clinician | No |

| Alexander et al. [27] | 2020 | E-SWAN | DMDD module | Parent-rating | Cronbach's alpha = 0.98, AUC 0.85 |

| Alexander et al. [85] | 2017 | E-SWAN | Parent-rating | Reliabilities range from .77 to .96 | |

| Le et al. [149] | 2020 | Case records | Medicaid records | Clinician | No |

| Averna et al. [65] | 2016 | CBCL-DP | Anxious/Depressed, Attention Problems, and Aggressive Behaviour syndrome scales | Clinician | NA |

| McTate et al. [53] | 2017 | ChIPS and MINI-KID | Both measures were checked for relevant items | Clinician | NA |

| Johnstone et al. [148] | 2020 | CASI | DMDD subscale | Parent-rating | No |

| Althoff et al. [9] | 2016 | CIDI | Strengths and Difficulties section of the PSAQ | Clinician | Rates of this new measure were compared with other psychiatric diagnoses and to service usage, no numbers reported |

| Martin et al. [96] | 2017 | DIPA | ODD and MDD modules | Clinician | NA |

| Chen et al. [130] | 2019 | K-SADS-E | In Mandarin | Clinician | Reported in Chen et al. 2017 |

| Sparks et al. [56] | 2014 | SCID-IV | Sections from K-SADS-PL and ODD module, and review of narrative summaries of clinical presentations | Clinician | NA |

| Grau et al. [36] | 2018 | Set of questions | Six questions referring to current severe temper outbursts and severe temper outburst during primary school to determine whether DSM-5 criteria were met | Self-rating | NA |

| Copeland et al. [37] | 2016 | Structured interview | Structured diagnostic interview completed with a parent; diagnosis of DMDD was made post hoc because its criteria overlapped entirely with those of ODD and depression | Clinician | NA |

| Mroczkowski et al. [120] | 2018 | V-DISC | ODD module | Self-rating/clinician | No |

K = 10 studies without any information about DMDD measurement or psychometric properties are not shown

DMDD disruptive mood dysregulation disorder, ADHD attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, ODD oppositional defiant disorder, BD bipolar disorder, SMD severe mood dysregulation, MDD major depressive disorder, ARI Affective Reactivity Index, NA information not available

aIf not provided in the publication, this information was obtained through direct contact with study authors

In k = 8 studies (7.3%; k = 2 abstracts, 1.8%) a clinical diagnosis was made without any specific measures and in k = 7 studies (6.4%; k = 3 abstracts, 2.7%) diagnosis was made using chart review or Medicaid records (n = 1). Finally, k = 10 (9.1%; k = 6 abstracts, 5.5%) studies did not provide any information on the measure used.

In most of the measures used in the included studies, a clinician rated the patients’ and participants’ statements and behavior (n = 91, 82.7%), while others consisted of a parent- (n = 3, 2.7%), or self-rating (n = 4, 3.6%). No information about the rater was given in k = 10 (9.1%) studies.

Psychometric properties

In k = 79 studies (71.8%; k = 17 abstracts, 15.5%), any information on the presence or absence of psychometric properties of the measure used to diagnose DMDD was given or obtained from the authors. Of those, in k = 39 (35.5%; k = 4 abstracts, 3.6%) no psychometric properties have been obtained or reported as part of the study or using the study data. In the remaining k = 40 studies (36.4%, k = 13 abstracts, 11.8%), the most commonly reported psychometric property was reliability, with k = 33 (30.0%; k = 13 abstracts, 11.8%) reporting inter-rater reliability ranging from κ = 0.6 to 1 and k = 29 (26.4%; k = 11 abstracts, 10.0%) reporting intra-class correlation coefficients. Three studies assessed internal consistency with Cronbach's alpha = 0.92 for a Spanish version of the K-SADS-PL modified under the DSM-5 to diagnose DMDD [38], and Cronbach's alpha = 0.75 for the PAPA [39] and 0.98 for the E-SWAN DMDD scale [27]. In the studies of the NIMH group around Dr. Ellen Leibenluft (n = 25, 22.7%), raters were trained to reach inter-rater reliability with κ ≥ 0.9, before they contributed to interviews/data collection for the respective studies. Cases were further discussed in conference with other reliable clinicians and in a lab meeting where leading clinicians reviewed the core criteria before diagnosis was made. The same group also provided ICCs ≥ 0.9 differentiating the DMDD module from the mania/hypomania part of the K-SADS-PL. One study examined consensus validity between a clinical psychiatric interview based on DSM-5 diagnostic criteria and the Turkish version of the DSM-5 version of the K-SADS-PL (K-SADS-PL-DSM-5-T), led by two independent clinician-researchers [40]. A consensus of 96%, κ = 0.63 was reached. Further, concurrent validity was evaluated with the Affective Reactivity Index (ARI), κ = 0.70. One study generated Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves to obtain Area Under the Curve (AUC) for their diagnostic instrument, as a measure of predictive validity. With an AUC value of 0.85, the E-SWAN DMDD scale performed equally well in predicting diagnoses compared to the Affective Reactivity Index [27].

Discussion

Evidence from this systematic review points to a variety of different measures used for the evaluation and diagnosis of DMDD. The majority of studies used clinician-rated structured interviews in combination with DMDD specific symptom checklists. Few studies employed questionnaires or interviews specifically designed to measure DMDD or its severity. In the following, some of the most used measures are presented in more detail, before practical aspects, such as available languages and cost as well as diagnostic challenges and future directions are discussed.

By far the most often used instrument was the K-SADS-PL in combination with the DMDD module. The K-SADS-PL is a semi-structured interview to diagnose mental disorders in children aged 6–18. Administration time is estimated to be about 75 min for psychiatric patients and 35–45 min for healthy control subjects. It is freely available for download online. It has high inter-rater reliability and good to excellent test–retest reliability [19]. The DMDD module has been developed by a workgroup around Leibenluft, in collaboration with the K-SADS developer Kaufman. A prior version of this module was based on a research diagnosis coined severe mood dysregulation (SMD) [4]. The DMDD module is a checklist consisting of four items probing for the DSM-5 criteria to be met (Fig. 2, see supplementary material for the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria A-K). With training and case discussion, the module can be administered with high inter-rater reliability [41]. It has further shown to differentiate well between other mood disorders such as mania/hypomania.

Fig. 2.

K-SADS-PL DMDD module. Each of the questions are evaluated with 0, 1 or 2 for current and/or past episodes. The diagnostic criteria of DMDD are listed below the questions in the module (see supplementary material for the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria). Reprint authorized by Joan Kaufman, owner of the copyright of the K-SADS-PL

Our study’s findings revealed different methodological approaches to diagnosing DMDD. Some of the instruments utilized in the reviewed studies consisted of a symptom checklist. This was the case not only for the K-SADS-PL DMDD module but also for its precursor, the SMD module or the ODD module. While the checklist format might suggest simplicity, it is most often used in the context of the more comprehensive K-SADS-PL semi-structured interview, which is used by raters to create a proxy diagnostic using a combination of ODD, depression, or mania criteria, and thereby empirically derive a DMDD diagnosis. Moreover, a combination of comprehensive structured or semi-structured interviews (e.g., K-SADS-PL, SCID, DISC or CIDI) and self-made checklists or clinical evaluation to probe for DSM criteria have been employed. An approach that has further been adopted in some of the reviewed studies was to search established interviews or questionnaires (CBCL-DP, Conners, ChIPS, MINI or PAPA/CAPA/DIPA) for items relevant to the DMDD diagnosis. This approach likely stems from the fact that these studies assessed DMDD retrospectively in data not collected with the focus of determining the prevalence of DMDD.

Few instruments have been deliberately designed to diagnose DMDD. Those identified by this systematic review were the K-SADS-PL DMDD module, the Breton, Bergeron and Labelle DMDD scale (available as a semi-structured interview and questionnaire), the E-SWAN DMDD module (interview) and the DAWBA DMDD section (interview; see Table 3 for an overview of instruments designed to diagnose DMDD). The instruments contain 4–34 items assessing occurrences, frequencies, and circumstances of temper tantrums/outbursts and irritable or angry mood. All instruments are available in the English language. The Breton, Bergeron and Labelle DMDD Scale is additionally available in French, and the DAWBA DMDD section additionally exists in Danish and Portuguese. The E-SWAN and DAWBA scales are freely available online or upon request to the authors. Indicated age ranges are similar, encompassing preschool age to early adulthood. While the K-SADS-PL DMDD module, the Breton, Bergeron and Labelle DMDD Scale, and the DAWBA DMDD section provide categorical outcomes, the E-SWAN DMDD module is designed to capture DMDD symptoms dimensionally. This scale reconceptualizes each diagnostic criterion for DMDD as a behavior, which can range from high (strengths) to low (weaknesses). Regarding the psychometric properties, it seems that the DMDD module has been evaluated most often, as high levels of reliability are reported in many studies. However, these reliabilities have been reached artificially by training raters to differentiate K-SADS-PL DMDD from mania modules. Although useful for the clinic, this approach does not correspond to the evaluation of reliability as a measure of consistency between raters for a certain diagnostic instrument used in a study. Therefore, a more comprehensive psychometric evaluation of this widely used measure is necessary. Besides the DMDD module, psychometric properties have been reported for the E-SWAN DMDD module. The reliability of this scale has been reported to be excellent (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.98). Reporting of psychometric properties of the other DMDD scales is still pending. Studies using tools to diagnose DMDD followed a broad spectrum of study objectives and hypotheses. Thus, the DMDD measure and its psychometric properties might not have been the focus of attention, which might be the reason for not providing this information. However, to determine gold-standard measurement, psychometric evaluation of the currently used diagnostic measures is necessary.

Table 3.

Instruments designed to diagnose DMDD

| Method | Number of items | Freely available/costs | Languages available | Outcome dimensional | Indicated age range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-SADS-PL DMDD module | Symptom Checklist | 4 | Yes | English | No | 6–19 |

| Breton, Bergeron & Labelle DMDD Scale | Semi-structured interview/questionnaire | 11 | NA | English, French | No | NA |

| DAWBA DMDD section | Interview | 34 | Yes | English, Danish, Portugese | No | 5–18 |

| E-SWAN DMDD module | Interview | 10 | Yes | English | Yes | 6–17 |

DMDD disruptive mood dysregulation disorder, NA information not available

When assessing the psychometric properties of the instruments used in the included studies, mainly measures of reliability have been considered and reported. However, the psychometric evaluation of a diagnostic tool ideally also contains the assessment of its validity. Neither content-related (e.g., construct validity, factorial structure) nor criterion-related types of validity (e.g., concurrent or predictive validity) have been considered broadly in existing studies. One study reported substantial consensus validity (κ = 0.63) and concurrent validity (κ = 0.70) of a Turkish version of the K-SADS-PL [40]. A further study showed substantial predictive validity of the E-SWAN DMDD module (AUC = 0.85) [27]. Consequently, measures of validity require more attention in future research on the measurement of DMDD and should guide the reporting of respective measures in future studies.

Given the aim of the present systematic review, to provide an overview of existing instruments for the assessment of DMDD and their use in the diagnostic process, we refrained from conducting a formal risk of bias assessment of included studies. The potential risk of bias does not interfere with the aim of the present review and was thus deemed irrelevant.

Since the advent of DMDD, clinicians and researchers have noted various challenges and the diagnosis is not without controversy [17]. The characteristic symptoms of DMDD, namely irritable mood and temper outbursts are observed across multiple disruptive behavior and mood disorders and the validity of DMDD as a distinct diagnosis has been questioned [13, 42, 43]. Further, DMDD could not be distinguished from ODD based on symptomatology alone in a population-based study [44]. It has further been criticized that alternative thresholds for defining DMDD, as well as a closer investigation of clinically relevant thresholds, have so far only partly been considered in the existing literature [45]. The lack of precision in diagnosing DMDD might in part account for the criticism voiced about the clinical entity of DMDD. Similarly, the heterogeneity in measurement of DMDD up to date, as found in the present systematic review of the literature, might account for variations in current prevalence and comorbidity rates as well as findings on associations with risk factors or functional outcomes in individuals with DMDD. Studies designed a priori with appropriate instruments to capture DMDD are therefore necessary [46].

While the diagnostic entity of DMDD may be a useful clinical heuristic, many researcher-clinicians focus their efforts on broader transdiagnostic constructs, such as irritability [8]. Irritability has been defined as a heightened proneness to anger relative to peers [47, 48] which can be seen as a personality trait with a continuous distribution across the population. In children and adolescents with DMDD, by definition, irritability is severe and expressed stably across time. In the last decade, there has been a marked increase in irritability research and there have been neuroscientific as well as treatment-related approaches to understanding pathophysiological mechanisms [41, 49]. Until now, whether persistent irritability between temper outbursts and the outbursts themselves are independent of each other, or whether the mood between outbursts is rather a concatenation of less severe tantrums, remains unknown.

In addition to further psychometric evaluation of current diagnostic measures and the development of a gold-standard diagnostic measure, adjuvant measurement approaches have become popular in the last decade. One promising approach to describe the full spectrum of irritability and temper outbursts in patients’ everyday lives is ecological momentary assessment (EMA; also known as experience sampling method or ambulatory assessment). This involves the repeated sampling of patients’ experiences or mood, performed via a handheld device such as a mobile phone. This measurement method has high ecological validity, avoiding biases due to retrospective assessments [50]. The repeated measurement of affect, with multiple measurements during the day over several days, potentially in children or their parents might be insightful in the characterization of hourly and daily fluctuations of mood in patients with irritability and/or DMDD.

To inform the debate around the diagnostic entity of DMDD, the application of Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) constructs may yield greater clarity in terms of underlying processes and thus inform nosology as well as appropriate interventions [51]. The constructs of frustrative non-reward (Negative Valence Domain), reward prediction error (Positive Valence domain), attention and language (Cognitive domain) as well as arousal (Arousal and Regulatory systems) have been found to be particularly promising in this regard.

Limitations of the review

The present systematic review encompasses literature involving instruments for the categorical diagnosis of DMDD. In view of the described developments regarding dimensional aspects of DMDD, a systematic review of the literature on dimensional constructs, such as irritability would be informative and topical. Similarly, a comprehensive overview on the examination of developmentally non-appropriate temper tantrums would be of interest in this regard.

A substantial proportion of the studies included in this systematic review stems from one laboratory in the United States. More studies evaluating the reliability and validity of the DMDD diagnosis should be conducted in other laboratories, to reduce the potential bias of findings and address cultural differences.

Psychological assessment should not be made based on any one instrument in isolation. Rather, test findings should be integrated with information from personal and educational histories and in collaboration with other clinicians [52, 53]. Consequently, using any current instruments to evaluate DMDD will require additional query and clinical evaluation. For research purposes, however, standardized assessment methods are inevitable.

Conclusion and future directions

A variety of different measures have been used for the evaluation of DMDD. The most commonly used and established instrument consists of a symptom checklist, while more recently developed structured interviews and questionnaires are still to establish their reliability and validity in diagnosing DMDD. Dimensional and experimental approaches to assessing irritability and temper outbursts as well as their interrelation might bring forth more clarity about DMDD symptomatology in children.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all authors who responded to our requests and sent us additional information on their studies for the purpose of this systematic review of the literature (in alphabetical order by last name): Althoff Robert R., Basu Soumya, Baweja Raman, Benarous Xavier, Brotman Melissa A., Bryant Beverly J., Carlson Gabrielle A., Cimino Silvia, Coffey Barbara J, Copeland William E., Corell Christoph U., Cruz Maria, Cuffe Steven P., Davis Winders Deborah, Deveney Christen M., Dougherty Lea R., Estrada Prat Xavier, Eyre Olga, Freeman Andrew J., Fristad Mary A., Gold Andrea L., Guilé Jean-Marc, Haller Simone P., Higdon Claudine, Hulvershorn Leslie A., Ignaszewski Martha J., Kircanski Katharina, Labelle Réal, Linke Julia O., McTate Emily A., Miller Leslie, Mitchell Rachel H., Mroczkowski Megan M., Mulraney Melissa, Munhoz Tiago Neuenfeld, Özyurt Gonca, Pagliaccio David, Perepletchikova Franchesca, Perhamus Gretchen, Pogge David L., Ramires Vera R., Rohde Luis A., Santosh Paramala, Stoddard Joel, Stringaris Argyris, Swetlitz Caroline, Topal Zehra, Tseng Wan-Ling, Tudor Megan E., Tüğen Leyla E., Uher Rudolf, Ulloa Elena, Vidal-Ribas Pablo, Walyzada Frozan, Waxmonsky James G., Wiggins Jillian L., Zeni Cristian P. We would also like to thank our research assistant Laura Auderset for her great help in the study selection process.

Author contributions

IM-L and JK conceptualized the study, IM-L performed the literature search and data analysis and drafted the work, IM-L, JK and MK critically revised the work.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Universität Bern. Institutional funding from Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University of Bern, Switzerland.

Availability of data and material

Can be requested from the corresponding author.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leibenluft E. Severe mood dysregulation, irritability, and the diagnostic boundaries of bipolar disorder in youths. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:129–142. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10050766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stringaris A, Vidal-Ribas P, Brotman MA, Leibenluft E. Practitioner review: definition, recognition, and treatment challenges of irritability in young people. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2018;59:721–739. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leibenluft E, Charney DS, Towbin KE, et al. Defining clinical phenotypes of juvenile mania. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:430–437. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.3.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adleman NE, Kayser R, Dickstein D, et al. Neural correlates of reversal learning in severe mood dysregulation and pediatric bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50:1173–1185.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deveney CM, Connolly ME, Jenkins SE, et al. Neural recruitment during failed motor inhibition differentiates youths with bipolar disorder and severe mood dysregulation. Biol Psychol. 2012;89:148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas LA, Brotman MA, Muhrer EJ, et al. Parametric modulation of neural activity by emotion in youth with bipolar disorder, youth with severe mood dysregulation, and healthy volunteers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:1257–1266. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brotman MA, Kircanski K, Stringaris A, et al. Irritability in youths: a translational model. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174:520–532. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16070839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Althoff RR, Crehan ET, He J-P, et al. Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder at ages 13–18: results from the National Comorbidity Survey—Adolescent Supplement. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2016;26:107–113. doi: 10.1089/cap.2015.0038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Copeland WE, Angold A, Costello EJ, Egger H. Prevalence, comorbidity, and correlates of DSM-5 proposed disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:173–179. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12010132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Copeland WE, Shanahan L, Egger H, et al. Adult diagnostic and functional outcomes of DSM-5 disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:668–674. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13091213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tapia V, John RM. Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. J Nurse Pract. 2018;14:573–578.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2018.07.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Axelson D, Findling RL, Fristad MA, et al. Examining the proposed disruptive mood dysregulation disorder diagnosis in children in the longitudinal assessment of manic symptoms study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:1342–1350. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m07674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mayes SD, Waxmonsky J, Calhoun SL, et al. Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD) symptoms in children with autism, ADHD, and neurotypical development and impact of co-occurring ODD, depression, and anxiety. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2015;18:64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2015.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mayes SD, Waxmonsky JD, Calhoun SL, Bixler EO. Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder symptoms and association with oppositional defiant and other disorders in a general population child sample. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2016;26:101–106. doi: 10.1089/cap.2015.0074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Rosa C (2018) ICD-11 sessions in the 17th World Congress of Psychiatry. World Psychiatry. 17(1):119–120. 10.1002/wps.20507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Bruno A, Celebre L, Torre G, et al. Focus on disruptive mood dysregulation disorder: a review of the literature. Psychiatry Res. 2019;279:323–330. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, et al. Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Egger H, Angold A. The preschool age psychiatric assessment (PAPA): a structured parent interview for diagnosing psychiatric disorders in preschool children. In: DelCarmen-Wiggins R, Carter A, editors. Handbook of Infant and Toddler Mental Health Assessment. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. pp. 223–243. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Angold A, Costello EJ. The Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:39–48. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, et al. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geller B, Zimerman B, Williams M, et al. Reliability of the Washington University in St. Louis Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (WASH-U-KSADS) Mania and Rapid Cycling Sections. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:450–455. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boudjerida A, Labelle R, Bergeron L et al (2018) Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder scale in adolescence. 23rd World Congress of the International Association for Child & Adolescent Psychiatry and Allied Professions, Prague

- 25.Conners CK (2008) Conners 3rd edition manual. In: Multi-health systems, Toronto Ontario, Canada

- 26.Goodman R, Ford T, Richards H, et al. The development and well-being assessment: description and initial validation of an integrated assessement of child and adolescent psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000;41:645–655. doi: 10.1017/S0021963099005909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alexander LM, Salum GA, Swanson JM, Milham MP. Measuring strengths and weaknesses in dimensional psychiatry. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 2020;61:40–50. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gadow KD, Sprafkin JN (2015) Child and Adolescent Symptoms Inventory, vol 5. In: Checkmate Plus, Stony Brook New York.

- 29.Althoff RR, Rettew DC, Ayer LA, Hudziak JJ. Cross-informant agreement of the Dysregulation Profile of the Child Behavior Checklist. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178:550–555. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weller EB, Weller RA, Fristad MA, et al. Children’s interview for psychiatric syndromes (ChIPS) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:76–84. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kessler RC, Ustün TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scheeringa MS, Haslett N. The reliability and criterion validity of the Diagnostic Infant and Preschool Assessment: a new diagnostic instrument for young children. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2010;41:299–312. doi: 10.1007/s10578-009-0169-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen Y-L, Shen L-J, Gau SS-F. The Mandarin version of the Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-Epidemiological version for DSM-5—a psychometric study. J Formos Med Assoc. 2017;116:671–678. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2017.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.First MB, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, et al. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV (SCID) Washington, DC: Amercian Psychiatric Association; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grau K, Plener PL, Hohmann S, et al. Prevalence rate and course of symptoms of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD): a population-based study. Z Kinder Jugendpsychiatr Psychother. 2018;46:29–38. doi: 10.1024/1422-4917/a000552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Copeland WE, Simonoff E, Stringaris A. Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder in children with autism spectrum disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55:S269–S270. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.07.164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de la Peña FR, Rosetti MF, Rodríguez-Delgado A, et al. Construct validity and parent–child agreement of the six new or modified disorders included in the Spanish version of the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia present and Lifetime Version DSM-5 (K-SADS-PL-5) J Psychiatr Res. 2018;101:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kessel EM, Dougherty LR, Kujawa A, et al. Longitudinal associations between preschool disruptive mood dysregulation disorder symptoms and neural reactivity to monetary reward during preadolescence. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2016;26:131–137. doi: 10.1089/cap.2015.0071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ünal F, Öktem F, Çetin Çuhadaroglu F, et al. Reliability and validity of the schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version, DSM-5 November 2016-Turkish Adaptation (K-SADS-PL-DSM-5-T) Turk J Psychiatry. 2019 doi: 10.5080/u23408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wiggins JL, Brotman MA, Adleman NE, et al. Neural correlates of irritability in disruptive mood dysregulation and bipolar disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:722–730. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15060833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lochman JE, Evans SC, Burke JD, et al. An empirically based alternative to DSM-5’s disruptive mood dysregulation disorder for ICD-11. World Psychiatry. 2015;14:30–33. doi: 10.1002/wps.20176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roy AK, Lopes V, Klein RG. Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD): a new diagnostic approach to chronic irritability in youth. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:918–924. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13101301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mayes SD, Waxmonsky JD, Calhoun SL, Bixler EO (2016) Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder Symptoms and Association with Oppositional Defiant and Other Disorders in a General Population Child Sample. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 26(2):101–106. 10.1089/cap.2015.0074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Laporte PP, Matijasevich A, Munhoz TN, et al. Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder: symptomatic and syndromic thresholds and diagnostic operationalization. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2019.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tseng W-L. Editorial: A transdiagnostic symptom requires a transdiagnostic approach: neural mechanisms of pediatric irritability. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leibenluft E, Stoddard J. The developmental psychopathology of irritability. Dev Psychopathol. 2013;25:1473–1487. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413000722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vidal-Ribas P, Brotman MA, Valdivieso I, et al. The status of irritability in psychiatry: a conceptual and quantitative review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55:556–570. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haller SP, Stoddard J, MacGillivray C, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of a computer-based Interpretation Bias Training for youth with severe irritability: a study protocol. Trials. 2018;19:626. doi: 10.1186/s13063-018-2960-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Larson R, Csikszentmihalyi M (1992) Validity and reliability of the Experience Sampling Method. In: Csikszentmihalyi M, Vries M (eds) The Experience of Psychopathology: Investigating Mental Disorders in their Natural Settings (pp. 43- 57). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/CBO9780511663246.006

- 51.Meyers E, DeSerisy M, Roy AK. Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD): an RDoC perspective. J Affect Disord. 2017;216:117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Matarazzo JD. Psychological assessment versus psychological testing. Validation from Binet to the school, clinic, and courtroom. Am Psychol. 1990;45:999–1017. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.9.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McTate EA, Leffler JM. Diagnosing disruptive mood dysregulation disorder: integrating semi-structured and unstructured interviews. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2017;22:187–203. doi: 10.1177/1359104516658190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dougherty LR, Smith VC, Bufferd SJ, et al. DSM-5 disruptive mood dysregulation disorder: correlates and predictors in young children. Psychol Med. 2014;44:2339–2350. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713003115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Parmar A, Vats D, Parmar R, Aligeti M. Role of naltrexone in management of behavioral outbursts in an adolescent male diagnosed with disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2014;24:594–595. doi: 10.1089/cap.2014.0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sparks GM, Axelson DA, Yu H, et al. Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder and chronic irritability in youth at familial risk for bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53:408–416. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Deveney CM, Hommer RE, Reeves E, et al. A prospective study of severe irritability in youths: 2- and 4-year follow-up. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32:364–372. doi: 10.1002/da.22336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Estrada Prat X, Alvarez Guerrico I, Camprodon Rosanas E, et al. Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder and pediatric bipolar disorder. Sleep and attention. Eur Child Adolesc Psych. 2015;24:S245–S245. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mitchell RHB, Hlastala SA, Mufson L, et al (2015) Correlates of disruptive mood dysregulated disorder (DMDD) phenotype among adolescents with bipolar disorder. 17th Annual Conference of the International Society for Bipolar Disorders, June 3–6, Toronto, Canada. Bipolar Disorders, Volume 17, S1. 10.1111/bdi.12309

- 60.Schilpzand EJ, Hazell P, Nicholson J, et al (2015) Comorbidity and correlates of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder in 6–8 year old children with ADHD. 5th World Congress on ADHD: From Child to Adult Disorder: 28th-31st May, Glasgow Scotland. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. Volume 7, Suppl 1:1-119. 10.1007/s12402-015-0169-y

- 61.Stoddard J, Sharif-Askary B, Harkins E, et al. Preliminary evidence for computer-based training targeting hostile interpretation bias as a treatment for DMDD. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40:S290–S291. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tseng W-L, Brotman M, Deveney C, et al. Neuropsychopharmacology. London: Nature Publishing Group; 2015. Neural mechanisms of irritability in youth across diagnoses: dimensional and categorical approaches; pp. S190–S191. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Uran P, Kılıç BG. Family Functioning, Comorbidities, and behavioral profiles of Children with ADHD and disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. J Atten Disord. 2015 doi: 10.1177/1087054715588949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]