Abstract

Objective

Redundant nerve root syndrome (RNRS) is characterized by tortuous, elongated, and enlarged nerve roots in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis. This study was performed to evaluate the effects of caudal block in patients with RNRS and assess factors associated with RNRS.

Methods

Patients with lumbar spinal stenosis who underwent caudal block were retrospectively analyzed. A comparative analysis of pain reduction was conducted between patients with RNRS (Group R) and those without RNRS (Group C). Generalized estimating equation analysis was used to identify factors related to the treatment response. RNRS-associated factors were analyzed using logistic regression analysis.

Results

In total, 54 patients were enrolled (Group R, n = 22; Group C, n = 32). Group R had older patients than Group C. The caudal block showed less pain reduction in Group R than in Group C, but the difference was not statistically significant. Generalized estimating equation analysis showed that RNRS was the factor significantly associated with the treatment response. The dural sac anteroposterior diameter and left ligamentum flavum thickness were associated with RNRS in the logistic regression analysis.

Conclusions

Caudal block tended to be less effective in patients with than without RNRS, but the difference was not statistically significant.

Keywords: Redundant nerve root syndrome, spinal stenosis, caudal block, pain reduction, dural sac diameter, ligamentum flavum thickness, generalized estimating equation analysis

Introduction

Redundant nerve root syndrome (RNRS) is characterized by the presence of tortuous, elongated, and enlarged nerve roots in the lumbar subarachnoid space.1–4 RNRS is closely related to lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS).4 Although the etiology of RNRS remains unclear, compressive force on nerve roots within the spinal canal2 and restriction of normal movement of nerve roots1 are thought to lead to stretching of nerve roots.4 In particular, spinal flexion and extension movements are hypothesized to cause stretching of nerve roots, which leads to redundancy and elongation.1

Whether RNRS is a simple phenomenon of LSS or a pathological cause of clinical symptoms remains unknown.4 Additionally, the response to treatment in patients with RNRS varies among studies.4–6 RNRS can induce degenerative changes of the nerve roots,3 which may reduce the effectiveness of treatment. Several studies have evaluated the effects of surgery on RNRS. Some studies revealed poor outcomes of surgery in patients with RNRS,5,7 whereas another study showed no significant differences in the effectiveness of surgical treatment.6

Few studies have focused on other types of interventions, such as epidural block, on the treatment response in patients with RNRS. Therefore, this observational retrospective study was performed to evaluate the effects of caudal block on patients with RNRS and to identify the factors associated with RNRS.

Methods

Study design

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Konyang University Hospital, Daejeon, Korea in February 2022 (approval number: KYUH 2022-01-035). The requirement for informed consent was waived because of the retrospective nature of the study. The clinical data of patients with LSS aged 20 to 90 years treated with caudal block from June 2019 to June 2021 were analyzed. The patients were stratified into two groups: Group R (patients with RNRS) and Group C (patients without RNRS). The medical records were reviewed to gather information on demographics, duration and intensity of pain based on a numeric rating scale (NRS), location of pain (low back pain and/or radicular pain), and claudication. A comparative analysis of pain reduction was conducted between the two groups. All patient data with personally identifiable information were removed. We designed this study according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.8

Patient eligibility

The inclusion criteria were (a) low back and/or leg pain and (b) LSS in one or more regions confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The exclusion criteria were (a) a history of spinal surgery, (b) spinal deformity (severe scoliosis, compression fracture, or high-grade spondylolisthesis), (c) spinal arteriovenous malformation on MRI, and (d) a history of lumbar spine cancer.

Radiologic evaluation

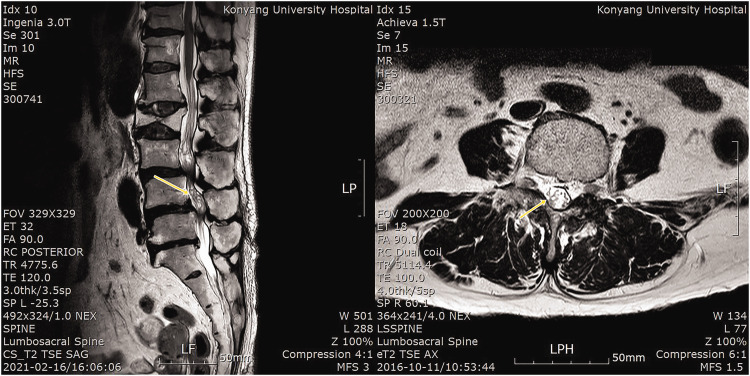

The MRI scans were analyzed by a radiologist and a pain clinic specialist with >5 years of clinical experience. The presence of RNRS was reviewed on T2-weighted MRI scans (Figure 1). The following data were also recorded: total number of spinal stenoses, most stenotic level, spinal cord cross-sectional area (CSA), distance from the conus medullaris to the most stenotic level in the lumbar spine (distance from C to S), grade of lumbar central spinal stenosis, grade of lumbar foraminal spinal stenosis, and other spinal radiologic parameters on lumbar MRI.

Figure 1.

Redundant nerve root syndrome on T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging.

The spinal cord CSA and distance from C to S were measured on axial and sagittal MRI, respectively. The spinal cord CSA was defined as the region distributed by the dural sac on axial MRI, and the distance from C to S was measured as the length from the conus medullaris to the most stenotic level on mid-sagittal MRI (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Spinal cord CSA: area distributed by the dural sac on axial magnetic resonance imaging. Distance from C to S: distance from conus medullaris to the most stenotic level in the lumbar spine.

CSA, cross-sectional area.

Both central and foraminal spinal stenosis were divided into four grades. Central spinal stenosis: grade 0 = no lumbar stenosis without obliteration of the anterior cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) space, grade 1 = mild stenosis with separation of all of the cauda equina, grade 2 = moderate stenosis with some aggregation of the cauda equina, and grade 3 = severe stenosis with no separation of the cauda equina.9 Foraminal spinal stenosis: grade 0 = no abnormal finding, grade 1 = perineural fat obliteration in two opposing directions (vertical or transverse) with no morphological change, grade 2 = perineural fat obliteration surrounding the nerve root in four directions without morphologic change in either the vertical or transverse direction, and grade 3 = nerve root collapse or morphological change.10

Other spinal radiologic parameters (dural sac anteroposterior [AP] diameter, osseous spinal canal AP diameter, osseous spinal canal transverse diameter, ligamentous interfacet distance, disc bulge, lateral recess height, ligamentum flavum thickness, and foraminal diameter)11 were measured at the most stenotic level of the spine on lumbar MRI. To minimize bias, the measurements were performed by a radiologist who was blinded to the presence of RNRS.

Additionally, MRI was used to evaluate the morphology of RNRS with respect to the RNRS type (type I, tortuous vs. type II, thickened), RNRS shape (shape I, serpentine vs. shape II, loop), and RNRS location (above/below/above vs. below) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Morphology of RNRS on magnetic resonance imaging. (a) RNRS type: type I = tortuous, type II = thickened. (b) RNRS shape: shape I = serpentine, shape II = loop and (c) Location of RNRS (above/below/above and below): above or below based on the most stenotic lesion.

RNRS, redundant nerve root syndrome.

Caudal block

The patient was placed in the prone position. Skin areas were prepared with an antiseptic solution. After draping, the sacral cornu was palpated, and the sacral hiatus was identified radiographically. The overlying skin and subcutaneous tissues were infiltrated with 1 mL of 1% lidocaine. A 20-gauge Touhy needle was advanced directly through the sacrococcygeal ligament and then advanced into the spinal canal an additional 1 cm. After confirming that the needle tip was placed in the epidural space under fluoroscopy, the needle was used to check for blood or CSF. After confirming no aspiration of blood or CSF, 1 mL of nonionic radiographic contrast was injected. Once the needle position was confirmed, 10 mL of 0.2% ropivacaine with 5 mg of dexamethasone was injected.

Evaluation of clinical outcomes and factors related to RNRS

The primary outcome of our study was comparison of pain reduction using the NRS in patients with and without RNRS after caudal block. The NRS ranged from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain imaginable). Pain based on the NRS was assessed at baseline and at <1, 1, 3, and 6 months after the caudal block by a resident who was blinded to whether the patient had RNRS. The extent of the pain reduction was compared based on the preprocedural NRS scores between the two groups. Patients with pain reduction of ≤30% and >30% were classified into the moderate and substantial response groups, respectively. The secondary outcome was determination of the factors related to RNRS based on medical records and MRI findings. The factors analyzed included patient demographic data and spinal radiological parameters. In addition, the treatment response according to RNRS morphology was evaluated.

Statistical analysis

We calculated the sample size to ensure that the study analysis was feasible. Pain reduction in both groups was measured in a preliminary study (n = 10 each), and the average pain reduction in Group C and Group R was 25.8% (standard deviation, 17.9%) and 10.1% (standard deviation, 18.4%), respectively. The sample size was calculated with an effect size of 0.865, power of 0.8, and α-value of 0.05 (two-sided), and 22 patients were required per group.

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation and were analyzed using Student’s t-test. Categorical variables are expressed as frequency or percentage and were analyzed using either the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Generalized estimating equation (GEE) analysis was used to identify the factors related to response (moderate or substantial response) to the caudal block. The factors associated with RNRS were evaluated using univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses. Variables included in the multivariate regression analysis were chosen for clinical importance, biological plausibility, and statistical consideration. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software Version 25.0 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and a p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

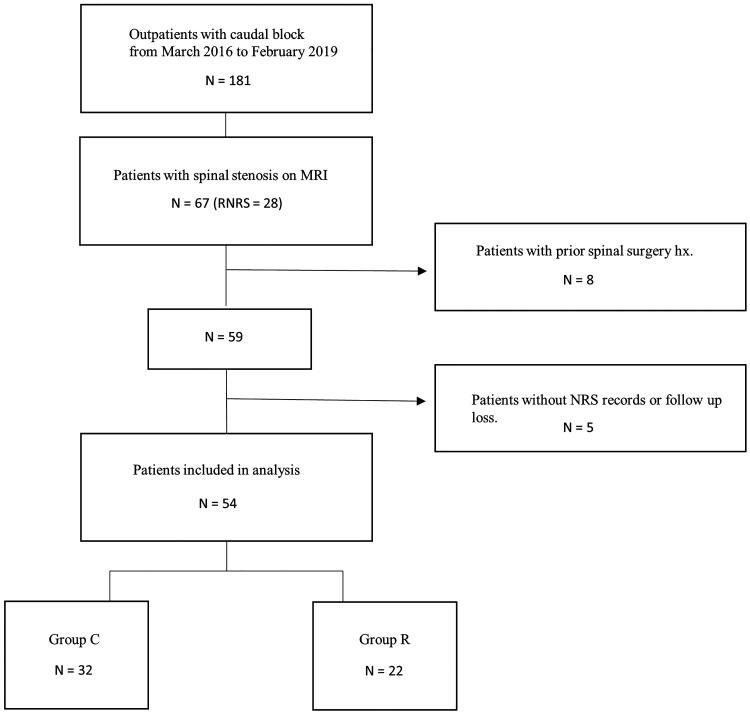

We identified 181 patients who underwent caudal block during the study period. Of the 181 patients, 67 had spinal stenosis on MRI, and 28 of them had RNRS. Of these 67 patients, 13 were excluded because of a history of spinal surgery before the caudal block (n = 8) and absence of NRS records or loss to follow-up (n = 5). Finally, 54 patients were included in this study, of whom 22 (40.7%) were found to have RNRS based on MRI findings. The final study group comprised 54 patients (22 in Group R and 32 in Group C) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Study flow diagram.

MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; hx, history; NRS, numeric rating scale.

With the exception of age, there were no significant differences in patient demographics or radiologic parameters between the two groups (Table 1). The proportion of older patients was significantly higher in Group R than in Group C (74.9 ± 7.3 versus 67.9 ± 9.3 years, respectively; p = 0.024). The male-to-female ratio was the same in both groups. The pain duration was not significantly different between Groups R and C (51.5 ± 39.5 and 39.9 ± 39.2 months, respectively). A comparison of the two groups showed no significant differences in parameters such as pain location and intensity, spinal stenosis levels, and underlying disease.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and radiologic parameters.

| Total | Group C | Group R | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 54) | (n = 32) | (n = 22) | p | |

| Age, years | 64.8 ± 10.9 | 67.9 ± 9.3 | 74.9 ± 7.3 | 0.024 |

| Sex | 1.000 | |||

| Male | 27 (50.0) | 16 (50.0) | 11 (50.0) | |

| Female | 27 (50.0) | 16 (50.0) | 11 (50.0) | |

| Hypertension | 25 (46.3) | 15 (46.9) | 10 (45.5) | 0.918 |

| Diabetes | 11 (20.4) | 7 (21.9) | 4 (18.2) | 0.741 |

| Duration of pain, months | 43.4 (3.0–54.0) | 39.9 ± 39.2 | 51.5 ± 39.5 | 0.293 |

| Pain location | 0.840 | |||

| Low back pain | 2 (3.7) | 1 (3.1) | 1 (4.5) | |

| Buttock or leg pain | 6 (11.1) | 3 (9.4) | 3 (13.6) | |

| Both | 46 (85.2) | 28 (87.5) | 18 (81.8) | |

| Pain intensity, NRS score | 5.6 ± 1.6 | 5.6 ± 1.7 | 5.6 ± 1.5 | 0.861 |

| Claudication | 0.551 | |||

| Yes | 15 (72.2) | 10 (31.3) | 5 (22.7) | |

| No | 39 (27.8) | 22 (68.8) | 17 (77.3) | |

| Spinal stenosis | 0.081 | |||

| 1 level | 7 (13.0) | 6 (18.8) | 1 (4.5) | |

| 2 levels | 20 (37.0) | 14 (43.8) | 6 (27.3) | |

| ≥3 levels | 27 (50.0) | 12 (37.5) | 15 (68.2) | |

| Most stenotic level | 0.428 | |||

| L2/3 | 6 (11.1) | 4 (12.5) | 2 (9.1) | |

| L3/4 | 11 (20.4) | 4 (12.5) | 7 (31.8) | |

| L4/5 | 34 (63.0) | 22 (68.8) | 12 (54.5) | |

| L5/S1 | 3 (5.6) | 2 (6.3) | 1 (4.5) | |

| Spinal cord CSA, mm2 | 90.4 ± 46.6 | 99.0 ± 53.2 | 77.88 ± 31.9 | 0.102 |

| Distance from C to S, mm | 89.7 ± 31.1 | 89.39 ± 34.3 | 90.14 ± 26.8 | 0.933 |

| Sedimentation sign | 0.152 | |||

| Yes | 20 (37.4) | 9 (28.1) | 11 (50.0) | |

| No | 34 (64.0) | 23 (71.9) | 11 (50.0) |

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, n (%), or median (range). NRS, numeric rating scale; CSA, cross-sectional area of central spinal canal at the level of the most severe lumbar spinal stenosis; Distance from C to S, distance from conus medullaris to the most stenotic level.

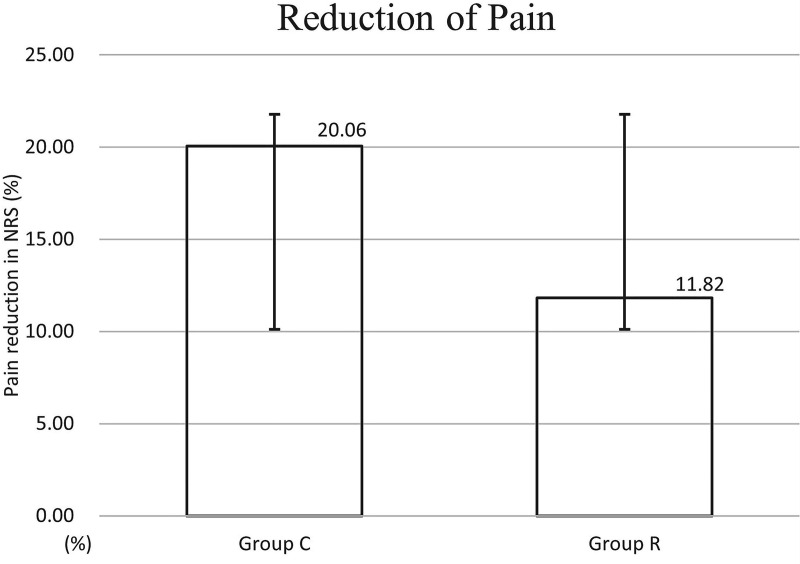

The caudal block showed a tendency to have less effect on the change in pain intensity (△NRS score <1 month after the caudal block) in Group R than in Group C, but there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups (Group R, 11.8 ± 25.1; Group C, 20.1 ± 21.5) (Figure 5). The proportion of patients with no response after the caudal block was higher in Group R than in Group C, but the difference was not statistically significant (Figure 6). However, GEE analysis showed that RNRS was significantly associated with a response to the caudal block (no RNRS: odds ratio [OR], 2.905; 95% confidence interval, 1.023–8.247; p = 0.045) (Table 2).

Figure 5.

Percentage of pain reduction <1 month after caudal block based on preprocedural pain score in patients with (Group R) and without (Group C) redundant nerve root syndrome. The graph shows the mean and standard deviation. Group R showed less pain relief, but there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups.

NRS, numeric rating scale.

Figure 6.

Treatment response after caudal block in patients with (Group R) and without (Group C) redundant nerve root syndrome.

Table 2.

Factors associated with moderate to substantial response to caudal block by generalized estimating equation analysis.

| Variables | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.029 | 0.976–1.083 | 0.289 |

| Sex | 0.658 | 0.211–2.047 | 0.469 |

| Duration of pain, months | |||

| <12 | 2.235 | 0.773–6.465 | 0.138 |

| 12 to 60 | 1.653 | 0.666–4.099 | 0.278 |

| >60 | 1 (Ref.) | ||

| Spinal stenosis | |||

| 1 level | 0.527 | 0.086–3.132 | 0.473 |

| 2 levels | 1.217 | 0.584–2.535 | 0.600 |

| ≥3 levels | 1 (Ref.) | ||

| Spinal cord CSA, mm2 | 1.009 | 0.993–1.025 | 0.259 |

| Central spinal stenosis | |||

| Grade 0 | 0.027 | 0.003–0.291 | 0.003 |

| Grade 1 | 0.366 | 0.056–2.375 | 0.292 |

| Grade 2 | 1.234 | 0.390–3.905 | 0.720 |

| Grade 3 | 1 (Ref.) | ||

| Foraminal stenosis | |||

| Grade 0 | 0.787 | 0.071–8.670 | 0.845 |

| Grade 1 | 0.292 | 0.037–2.281 | 0.240 |

| Grade 2 | 0.276 | 0.036–2.102 | 0.214 |

| Grade 3 | 1 (Ref.) | ||

| Claudication | 1.180 | 0.363–3.831 | 0.783 |

| Distance from C to S, mm | 0.999 | 0.983–1.014 | 0.853 |

| Redundant nerve root | |||

| No | 2.905 | 1.023–8.247 | 0.045 |

| Yes | 1 (Ref.) | ||

CSA, cross-sectional area of central spinal canal at the level of the most severe lumbar spinal stenosis; Distance from C to S, distance from conus medullaris to the most stenotic level; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; Ref., reference.

The dural sac AP diameter and right foraminal AP diameter were significantly lower in Group R than in Group C. The left ligamentum flavum thickness was significantly higher in Group R than in Group C (Table 3, Figure 7). Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that the dural sac AP diameter and left ligamentum flavum thickness were the independent factors associated with the occurrence of RNRS (OR, 0.753, p = 0.043 and OR, 1.883, p = 0.014, respectively) (Table 4). The treatment response according to RNRS morphology showed no statistically significant difference between the groups. However, no patients with the thickened type and loop shape showed a substantial response (Table 5).

Table 3.

Radiologic parameters of spine in both groups.

| Spinal radiology (mm) | Group C (n = 32) | Group R (n = 22) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dural sac AP diameter | 8.5 ± 2.7 | 6.9 ± 2.5 | 0.027 |

| Osseous spinal canal AP diameter | 13.3 ± 3.8 | 12.8 ± 2.8 | 0.580 |

| Osseous spinal canal transverse diameter | 14.6 ± 4.9 | 12.9 ± 3.2 | 0.182 |

| Ligamentous interfacet distance | 11.3 ± 4.3 | 9.9 ± 3.7 | 0.228 |

| Disc bulge | 3.6 ± 1.2 | 4.0 ± 1.5 | 0.270 |

| Lateral recess height (L) | 1.9 ± 1.0 | 1.6 ± 0.7 | 0.272 |

| Lateral recess height (R) | 2.0 ± 0.9 | 1.5 ± 0.9 | 0.084 |

| Ligamentum flavum thickness (L) | 2.5 ± 1.2 | 3.5 ± 1.4 | 0.007 |

| Ligamentum flavum thickness (R) | 2.4 ± 0.8 | 2.9 ± 1.0 | 0.278 |

| Foraminal AP diameter (L) | 6.3 ± 1.8 | 5.7 ± 1.4 | 0.225 |

| Foraminal AP diameter (R) | 6.8 ± 1.6 | 6.0 ± 1.4 | 0.039 |

| Foraminal SI diameter (L) | 7.3 ± 3.5 | 7.3 ± 1.3 | 0.994 |

| Foraminal SI diameter (R) | 8.0 ± 3.5 | 7.5 ± 1.2 | 0.610 |

Data area expressed as mean ± standard deviation. AP, anteroposterior; SI, superoinferior; L, left; R, right.

Figure 7.

Comparison of radiological parameters of the spine in the two groups.

AP, anteroposterior; SI, superoinferior; L, left; R, right. *Significant difference between the two groups.

Table 4.

Logistic regression analysis of factors related to redundant nerve root syndrome.

| Univariate |

Multivariate |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | |

| Age | 1.089 | 0.980–1.210 | 0.114 | 1.071 | 0.992–1.157 | 0.081 |

| Duration of pain, months | ||||||

| <12 | 1 (Ref.) | |||||

| 12 to 60 | 4.384 | 0.725–26.526 | 0.108 | |||

| >60 | 3.498 | 0.436–28.084 | 0.239 | |||

| Spinal stenosis | ||||||

| 1 level | 1 (Ref.) | |||||

| 2 levels | 1.412 | 0.082–24.201 | 0.812 | |||

| ≥3 levels | 1.113 | 0.061–20.375 | 0.942 | |||

| Spinal cord CSA | 1.003 | 0.984–1.022 | 0.783 | |||

| Dural sac AP diameter | 0.724 | 0.517–1.014 | 0.060 | 0.753 | 0.572–0.990 | 0.043 |

| Ligamentum flavum thickness (L) | 1.949 | 1.027–3.699 | 0.041 | 1.883 | 1.137–3.121 | 0.014 |

| Foraminal AP diameter (R) | 0.695 | 0.378–1.277 | 0.242 | |||

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; Ref., reference; CSA: cross-sectional area of central spinal canal at the level of the most severe lumbar spinal stenosis; AP, anteroposterior; L, left; R, right.

Table 5.

Treatment response according to morphology of RNRS.

| Morphology of RNRS | No response | Moderate response | Substantial response | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNRS type | 0.112 | |||

| Type I (tortuous) | 7 (50.0) | 2 (14.3) | 5 (35.7) | |

| Type II (thickened) | 4 (50.0) | 4 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| RNRS shape | 0.530 | |||

| Shape I (serpentine) | 8 (47.1) | 4 (23.5) | 5 (29.4) | |

| Shape II (loop) | 3 (60.0) | 2 (40.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Location of RNRS | 0.578 | |||

| Above | 8 (50.0) | 4 (25.0) | 4 (25.0) | |

| Below | 2 (66.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (33.3) | |

| Above and below | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | 0 (0.0) |

Data area expressed as n (%). RNRS, redundant nerve root syndrome; L, left; R, right; Location of RNRS, location of RNRS relative to the most stenotic lesion in the lumbar spine.

Discussion

The reported prevalence of RNRS ranges from 33.8% to 42.0% in patients with LSS.10 RNRS, initially thought to be rare, is a relatively common radiological finding in patients with LSS. In our study, patients with RNRS accounted for 40.7% of all patients analyzed. Although there has been controversy over the clinical relevance of RNRS, studies have revealed an association between RNRS and more severe stenosis.11,12 In RNRS, elongation and redundancy of the nerve roots induced by the constriction secondary to LSS can cause degenerative changes of the nerves.11,13 The degenerative changes may be accompanied by endoneural fibrosis, demyelination, and Schwann cell proliferation at the histological level.13 These degenerative changes in the nerve roots are not always reversible, and persistent RNRS is associated with poor clinical outcomes.6 Yokoyama et al.5 showed that RNRS may not resolve postoperatively, with worse outcomes observed for patients without than with RNRS resolution.

In our study, patients with RNRS were less responsive to the caudal block than were patients without RNRS. We expected RNRS to have a more pronounced negative effect on pain reduction. However, there was no significant difference between the patients with and without RNRS, although GEE analysis showed that RNRS had a significant effect on the treatment response over time. A previous study on lumbar epidural block showed significant differences in pain reduction between patients with and without RNRS.4 An epidural block is an alternative treatment method for refractory low back pain with LSS.14 The caudal block and lumbar epidural block are representative approaches of epidural blocks. A major advantage of caudal block is that access is easier, and an equal or better effect can be expected compared with lumbar epidural block.15,16 Therefore, it is unlikely that the difference in the approach for the epidural block significantly affected the study result.

Previous studies have also shown inconsistent results regarding the treatment outcomes of patients with RNRS. Some studies showed poorer outcomes associated with RNRS,4,5,7 whereas other studies did not reveal significant differences.6,17 These results may have been influenced by several factors, including patient characteristics and the assessment and treatment methods. More fundamentally, however, the type and shape of RNRS may have affected the results. Type II RNRS is associated with grossly thickened nerve roots compared with type I, which is characterized simply by tortuous roots, and it is thought that irreversible change in the nerve roots may have occurred secondary to increased intradural pressure.4 Additionally, shape II RNRS has a loop shape beyond the serpentine shape of shape I.17 A previous study showed that loop-shaped RNRS has a significant correlation with the persistence of RNRS postoperatively and a poorer post-treatment outcome.5 Therefore, clinical results may differ depending on the ratio of type II and shape II among patients with RNRS. In this study, eight (36.4%) and five (22.7%) patients had type II and shape II, respectively, and these proportions seem to vary among studies.17 Our study showed no substantial treatment response in patients with type II and shape II. Therefore, treatment is expected to be less effective for these patients. Accordingly, further research on clinical results based on RNRS types and shapes is needed.

In this study, RNRS was significantly associated with age. Patients with RNRS were older than those without RNRS. This result is also consistent with the findings reported by Nathani et al.11,18 It may be assumed that more degenerative changes of the spine occur over time, resulting in the development of RNRS. Among the MRI parameters, the dural sac AP diameter, left ligamentum flavum thickness, and right foraminal AP diameter were significantly correlated with RNRS. This result differs from that of a previous study, in which only the ligamentous interfacet distance was significantly related.11 Our multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that only the dural sac AP diameter and left ligamentum flavum thickness were independent factors associated with the occurrence of RNRS. Therefore, it may be assumed that LSS of the central and lateral recess zones has a decisive effect on the development of RNRS. However, the distance from C to S (the length of redundant nerve roots), which was associated with RNRS in the previous studies,4,6 was not significantly correlated in the present study. A shorter distance from C to S was associated with a higher likelihood of RNRS. However, this parameter is likely to be affected by an individual’s body size and sex. In addition, the sedimentation sign, which is mainly observed in patients with central spinal stenosis,19 was not significantly related to RNRS.

The current study has several limitations. A major limitation is the small number of enrolled patients. In addition, the retrospective nature of this study is associated with a possibility of bias, as are the different treatment efforts such as medication and other interventions over time. The presence of RNRS could not be completely hidden from the radiologist while measuring spinal parameters on MRI. The relatively short follow-up period is also a limitation of our study. Although the response to treatment according to the type and shape of RNRS was evaluated, the number of patients in each subgroup was insufficient. Finally, factors other than pain reduction were not evaluated. An assessment of factors such as changes in functional outcomes and improvements of LSS symptoms after caudal block is also required.

Conclusion

RNRS showed a tendency to be less responsive to caudal block. However, pain reduction was not significantly different between patients with and without RNRS. We did not observe a clinical correlation between RNRS and pain relief after caudal block. This can be helpful for practitioners who consult with patients regarding epidural block and prognosis. However, further studies based on the type and shape of RNRS are needed to determine the clinical relevance of RNRS. The independent factors associated with RNRS were a short dural sac AP diameter and increased left ligamentum flavum thickness.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge Jee-Young Hong, Healthcare Data Science, Konyang University Hospital, Republic of Korea for supervising the statistical analysis in this study.

Author contributions: Conceptualization: Chi-Bum In

Data curation: Sieun Yoon, Hyeongchun Kim, Chi-Bum In

Formal analysis: Sieun Yoon, Hyeongchun Kim, Chi-Bum In

Supervision: Chi-Bum In

Validation: Hyeongchun Kim, Chi-Bum In

Writing – original draft: Sieun Yoon, Chi-Bum In

Writing – review & editing: Sieun Yoon, Hyeongchun Kim, Chi-Bum In

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Chi-Bum In https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3658-5277

Data availability statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

References

- 1.Ozturk AK, Gokaslan ZL. Clinical significance of redundant nerve roots of the cauda equina. World Neurosurg 2014; 82: e717–e718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Villafañe FE, Harvey A, Kettner N. Redundant nerve root in a patient with chronic lumbar degenerative canal stenosis. J Chiropr Med 2017; 16: 236–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mattei TA, Mendel E. Redundans nervi radix cauda equina: pathophysiology and clinical significance of an intriguing radiologic sign. World Neurosurg 2014; 82: e719–e721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee JH, Sim KC, Kwon HJ, et al. Effectiveness of lumbar epidural injection in patients with chronic spinal stenosis accompanying redundant nerve roots. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019; 98: e14490. Epub ahead of print. DOI: 10.1097/MD.0000000000014490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yokoyama K, Kawanishi M, Yamada M, et al. Clinical significance of postoperative changes in redundant nerve roots after decompressive laminectomy for lumbar spinal canal stenosis. World Neurosurg 2014; 82: e825–e830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Min JH, Jang JS, Lee SH. Clinical significance of redundant nerve roots of the cauda equina in lumbar spinal stenosis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2008; 110: 14–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoon LJ, Moon BG, Bae IS, et al. Association between redundant nerve root and clinical outcome after fusion for lumbar spinal stenosis. Asian J Pain 2021; 7: 5. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med 2007; 147: 573–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guen YL, Joon WL, Hee SC, et al. A new grading system of lumbar central canal stenosis on MRI: an easy and reliable method. Skeletal Radiol 2011; 40: 1033–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee S, Lee JW, Yeom JS, et al. A practical MRI grading system for lumbar foraminal stenosis. Am J Roentgenol 2010; 194: 1095–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nathani KR, Barakzai MD, Rai HH, et al. Spinal radiology associated with redundant nerve roots of cauda equina in lumbar spine stenosis. J Clin Neurosci 2022; 102: 36–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Savarese LG, Ferreira-Neto GD, Herrero CF, et al. Cauda equina redundant nerve roots are associated to the degree of spinal stenosis and to spondylolisthesis. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2014; 72: 782–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kobayashi S. Pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment of intermittent claudication in patients with lumbar canal stenosis. World J Orthop 2014; 5: 134–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsai YH, Huang GS, Tang CT, et al. The role of power Doppler ultrasonography in caudal epidural injection. Medicina (Mex) 2022; 58: 575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogoke BA. Caudal epidural steroid injections. Pain Physician 2000; 3: 305–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu J, Zhou H, Lu L, et al. The effectiveness of transforaminal versus caudal routes for epidural steroid injections in managing lumbosacral radicular pain. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016; 95: e3373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeong KS, Cho SA, Chung WS, et al. Effectiveness of percutaneous lumbar foraminoplasty in patients with lumbar foraminal spinal stenosis accompanying redundant nerve root syndrome: a retrospective observational study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020; 99: e21690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rousan LA, Al-Omari MH, Musleh RM, et al. Redundant nerve roots of the cauda equina, MRI findings and postoperative clinical outcome: emphasizing an overlooked entity. Glob Spine J 2022; 12: 392–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barz T, Melloh M, Staub LP, et al. Nerve root sedimentation sign: evaluation of a new radiological sign in lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine 2010; 35: 892–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.