Abstract

The photolysis of colchicine under ultraviolet and visible light irradiation was studied by ultraviolet (UV) scanning and HPLC-MS. The photoproduct was proposed and the cytotoxicity change before and after irradiation was investigated. Results showed that both ultraviolet and visible light irradiation could effectively degrade colchicine into deacetamido-lumicolchicine. The process conformed to first-order kinetics, in which a high degradation rate (K = 0.5862 h− 1) was observed when colchicine was dissolved in ethanol and irradiated by UV light. Cell viability and cell cycle studies proved that a photolysis treatment of colchicine could weaken the cytotoxicity effectively. Colchicine inhibited the division of BRL 3 A cells in G2/M phase with an IC50 value of 0.48 µg/mL, while the toxic effect could be reduced significantly with IC50 2.1 µg/mL when colchicine was exposed to UV irradiation. Results are beneficial to the toxicity elimination of colchicine in the processing of daylily flower in food industry, and can also provide photochemistry reference for colchicine-related studies.

Keywords: Colchicine, Daylily, Photolysis, Cytotoxicity, Food safety

Introduction

Daylily flower (Hemerocallis citrine Baroni) has been used as an herbal vegetable for hundreds of years in Asia. Documents showed that it contains high content of antioxidant flavonoids and has many functional effects [1–3]. So, daylily flowers were introduced as an edible flower worldwide and becomes very popular nowadays [4]. However, fresh daylily flower may be toxic if not treated properly owing to the existence of colchicine. Cases of food poisoning caused by daylily flower were reported due to the excessive intake of colchicine [5–7]. Therefore, it is significant in food processing to decrease the content of colchicine in daylily flower in consideration of health benefits. Generally, daylily flower is heat-treated in hot water or in steam, and then dried for toxicity reduction and long-term storage. Besides, the harvested daylily flower in rural areas was also exposed to sunshine to reduce the potential food safety risk of colchicine.

Colchicine is an alkaloid which can be extracted from Colchicum autumnale. It could be used as a prescription for Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF), gout, inflammation, cardiovascular disease, and cancer, etc. [8–10]. Recent studies showed that colchicine is potential to prevent Covid-19 complications [11, 12]. Colchicine consists of a trimethoxy benzene ring (A-ring), a seven-membered ring (B-ring) with an acetamide group, and a methoxy tropone ring (C-ring) in molecule. This structure may exhibit different stability due to ambient conditions including pH, temperature, solvent, redox system, and light. In our pre-experiment, colchicine showed not only excellent thermo-stability but also light sensitivity under irradiation. Attempts, such as photolysis, were made to reduce the toxins in natural foods over the years. Previous studies reported that the structure of colchicine might occur with isomerization transformation and aggregation when it was irradiated [13–15]. Moreover, the food safety questions on alkaloids in natural foods were increasingly focused on by researchers in recent years [16, 17]. Although the cytotoxicity of colchicine and its derivatives was widely studied previously [18, 19], there is few reports about the toxicity change resulting from the irradiation. So, the photolysis of colchicine under ultraviolet and visible light irradiation was conducted, herein, by which the kinetics was studied and the possible structure of photoproduct was proposed. Further, the toxicity changes of colchicine before and after irradiation was investigated by MTT and cell cycle assays on BRL 3 A cells. Results can provide a photochemistry reference for the toxicity elimination of colchicine in the daylily flower processing of food industry.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and materials

Colchicine (C22H25NO6, 98%) was purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd, China. Phosphate buffered solution (PBS, pH 7.2–7.4, Adamas life), cell cycle detection kit (Bioss), Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, GIBCO by life technologies), DMSO (Adamas) and fetal bovine serum (FBS, Adamas life) were purchased from Shanghai Titan Scientific Co., Ltd, China. BRL 3 A (CRL-1442) rat liver cells were obtained from National Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures in Shanghai, China.

Photolysis of colchicine

A method graph of the overall experimental design was shown in Fig. S1. The photolysis of colchicine was carried out under the irradiation of a tungsten lamp (200 W, 300–700 nm, Shenzhen IWOWN Information Technology Co., Ltd, China) and an ultraviolet lamp (T5-8 W, 254 nm, Suzhou Antai Airtech Co., Ltd, China). Twenty-five milliliter colchicine solution (in PBS or water) was put into a conical flask, which was corked and then exposed to tungsten lamp irradiation. The solution was sampled for UV-Vis scanning (UV-6000PC, Shanghai Metash Instruments Co., Ltd, China) and concentration analysis every two hours during the irradiation. In the case of UV (8 W) irradiation, colchicine solution was contained in a quartz tube to avoid light penetration loss.

Kinetic study on colchicine photolysis

An enclosed room without any light was used to investigate the stability of colchicine in dark, and other studies were conducted under visible or UV light irradiation. Colchicine solution (initial concentration: 10 µg/mL) was prepared by using water, 30% ethanol, 70% ethanol and 100% ethanol as solvent, and was adjusted to pH 4, 7 or 10 when necessary. A water-bath was used to keep the solution temperature (5 °C, 25 °C, 60 or 90 °C). For control, the solution composition was the same as that of the test one, but it was under natural light. Change in colchicine concentration was quantified by HPLC analysis.

HPLC-MS analysis

Samples collected after 2 and 30 h of tungsten lamp irradiation were analyzed by Plus HPLC and a TSQ Quantum Ultra Mass system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The LC system was equipped with a Hypersil Gold column (100 × 2.1 mm, 5 μm, Thermo) maintained at 30 °C. Mobile phase (0.2 mL/min) included 0.1% (v/v) formic acid (A) and methanol (B). The gradient was 95% A for 0-5 min, 95 − 80% A for 5-8 min, 80 − 40% A for 8-13 min, 40 − 5% A for 13-18 min, 5% A for 18-30 min. The sample injection volume was 20 µL and the detection was carried out at 350 nm. Parameters for mass detection were as follows: sheath gas pressure, 30 (arbitrary unit); aux gas pressure, 15 (arbitrary unit); spray voltage, 4.50 kV; heated capillary temperature, 350 °C. MS scans were performed in positive ion mode (ESI) in the range of m/z 100–1000.

Cytotoxicity studies

MTT assay

A serial of colchicine solutions at 0.04, 0.07, 0.15, 0.31, 0.62, 1.25, 2.5, 5, 10, and 20 µg/mL were prepared with PBS, and then exposed to UV light (8 W) for 24 h. BRL 3 A cells were routinely cultured in DMEM (10% FBS) with a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere at 37 °C. The cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 103 cells/well (200 µL), and mixed with 100 µL colchicine solutions before and after the UV irradiation (PBS for control). The mixture was incubated for 24 h, followed by adding 10 µL MTT (5 mg/mL in PBS), which was further incubated at 37 °C for 4 h. Afterward, the medium was removed and 100 µL DMSO was added into the well. The absorbance of every well at 570 nm was tested with a microplate reader (Bio Tek, America) to assess the viability of BRL 3 A cells.

Cell cycle analysis

A colchicine solution (1.25 µg/mL in PBS) before and after being exposed to UV light (8 W, 24 h) was used for cell cycle analysis. The analysis was carried out by using a Bioss cell cycle detection kit according to its instruction. BRL 3 A cells were prepared as specified in the instruction, followed by adding colchicine solution with a control of PBS. After 24 h of incubation, the mixture was centrifuged and the treated cells were collected. Next, the cells were washed twice with pre-cooling PBS, suspended in 70% ethanol and stored at -20 °C overnight. Afterward, the cells were centrifuged again, washed with PBS, and stained by propidium iodide for 30 min. The categorization of cell cycle phases was then run by a flow cytometer (FCM, Thermo Fisher, America) with the software FlowJo V10.

Statistical analysis

All kinetic and cytotoxicity studies were carried out in triplicate and the results were expressed as means ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed with software SPSS 28.0 and the significant differences were evaluated by one-way ANOVA.

Results and discussion

Photolysis of colchicine

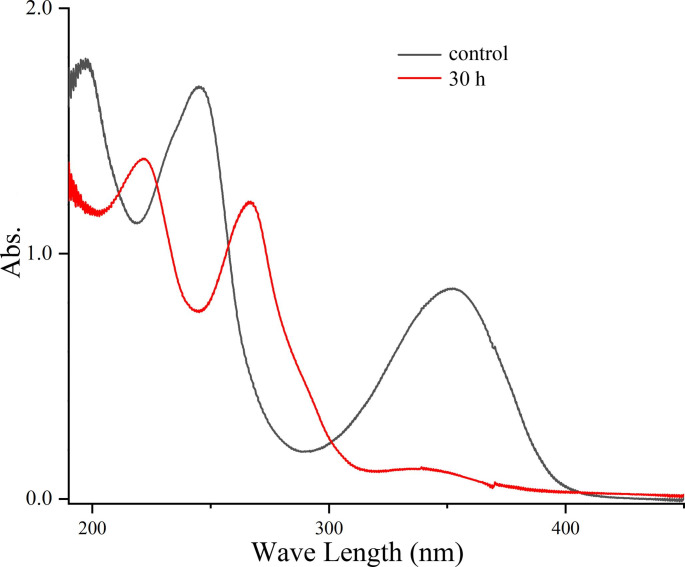

The stability of colchicine during 30 h of irradiation was investigated by using UV-vis absorbance scanning from 200 to 600 nm. As shown in Fig. 1, colchicine (20 µg/mL) has two characteristic peaks at 245 and 350 nm. When it was exposed to visible light irradiation (200w, 300–700 nm), both absorbances at the two peaks decreased gradually (data not shown). They ultimately disappeared after 30 h of irradiation, accompanied by the formation of two new peaks at around 221 and 267 nm (Fig. 1) This observation clearly suggested that colchicine was unstable and it occurred with changes in the molecular structure after being irradiated. The characteristic peaks of colchicine at 245 and 350 nm are typical for the tropolonic ring (C-ring), arising from n→π* and π→π* electron transitions [15]. Their disappearance indicated that the methoxy tropone ring (C-ring) of colchicine might be destructed by irradiation. In addition, since the n→π* transition is closely associated with the acetamide group contributing to the absorbance at 350 nm, so observations above also suggested that the irradiation might lead to the loss of the acetamide group in colchicine molecule [20]. The exact change in the structure of colchicine under irradiation was further investigated by following HPLC-MS studies.

Fig. 1.

UV-Vis scanning of colchicine (20 µg/mL in PBS) exposed to visible light at 25℃ (tungsten lamp, 200 W)

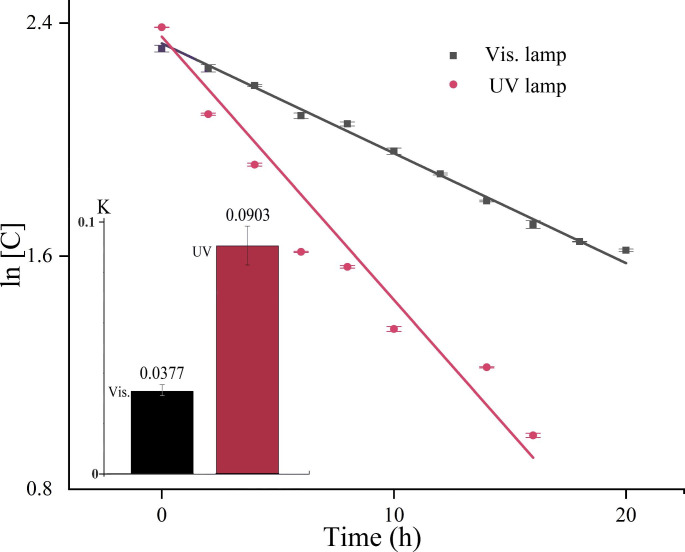

In comparison with visible light, UV irradiation (254 nm) of colchicine led to the same evolution trend of the absorption spectra. The two typical peaks at 245 and 350 nm disappeared gradually as colchicine was consumed, which were lastly replaced by two new peaks at around 221 and 267 nm. But it is worth noting that a much lower power of UV irradiation (8 W) reached a higher efficiency than visible light (200 W) to decrease colchicine concentration (Fig. 2). The reason may be that a shorter UV wavelength is more capable of activating colchicine photolysis through radical pathways [21]. Results above indicated that colchicine is unstable under both UV and visible light irradiation. In fact, when fresh daylily flower was harvested in rural, it was widely exposed to sunshine before storage. The sun-drying process of daylily flowers may be beneficial to health due to the reduction of colchicine in it.

Fig. 2.

Change in the concentration of colchicine exposed to UV and visible light. (Initial Conc., 10 µg/mL in water. UV, 8 W, ln[C] = 2.3531-0.0903t. Vis., 200 W, ln[C] = 2.2478-0.0377t)

Kinetic study on colchicine photolysis

The kinetic study was carried out by using the first-order kinetic equation as follows:

|

Where K is the apparent rate constant (h− 1), t is the irradiation time, C is the concentration of colchicine at the time t, and C0 is the initial concentration of colchicine [22, 23]. Under conditions including irradiation source, solvent, pH and temperature, the linear least-squares fits of ln(C0/C) versus irradiation time (t) were plotted. Results showed that the photolysis of colchicine conformed to the first-order kinetics, in which a larger K value suggests a higher degradation rate. As discussed above, irradiation source played a predominant role in affecting the degradation rate of colchicine. The rate constant K in the case of UV irradiation (8 W) was 0.0903 h− 1, while that under visible light irradiation (200 W) was 0.0377 h− 1 (Fig. 2). This result indicated that, in comparison with visible light, UV irradiation had a much higher efficiency to destroy colchicine.

The alcoholic solution of colchicine exhibited a faster degradation rate than the aqueous one. There are two ways involved in the photolysis of a compound in solution. One is the impact of the photon of light source, and the other refers to the induction of some active radicals [24, 25]. In comparison, the activation energy of ethanol dissociation is far lower than that of water. Thus, an alcoholic solution could produce radicals like hydroxyl radical more easily, which consequently promoted the degradation of colchicine. In order to specify the effect of solvent, the photolysis kinetics of colchicine in water, 30% ethanol, 70% ethanol and 100% ethanol were compared. As shown in Fig. 3, the rate constant K increased with the rise of ethanol ratio in the solvent, as a matter of fact, colchicine degraded 8 times faster in ethanol than in water.

Fig. 3.

Effect of solvent on the photolysis of colchicine (10 µg/mL) irradiated by tungsten lamp (200 W)

Effects of pH and temperature on colchicine photolysis were presented in Table 1, and more dynamics details were shown in Fig. S2-S7. When colchicine aqueous solutions kept a pH of 4, 7, and 10 at 25 °C, the rate constants K were 0.0309, 0.0377 and 0.0337 h− 1, respectively. In addition, when the solutions were at 5 °C, 25 and 60 °C with pH 7, the constants K were 0.0329, 0.0377 and 0.0332 h− 1, respectively. These observations indicated that pH and temperature did not change the degradation rate of colchicine substantially. In other words, the food safety risk of colchicine cannot be effectively eliminated by pH and temperature adjustment in daylily processing. Ghanem et al. applied a strong acid condition which resulted in a significant impact on the photolysis rate of colchicine [15]. However, no substantial change of the photolysis rate was observed at pH 4, 7 or 10 which is more similar to the ambient pH in food processing. The light sensitivity of colchicine was well recognized, which might be affected by solvent and light source [13–15, 23]. As shown in Table 1, when the ethanol solution was irradiated by visible light at 25 °C, colchicine quickly degraded at a rate constant of 0.2861 h− 1. While the irradiation was changed to UV source, the constant was remarkably increased to 0.5862 h− 1. It is worth noting that colchicine showed wonderful stability in the dark (Table 1). Without UV and visible light irradiation, no degradation was observed in the aqueous and alcoholic solutions, even if the temperature was further increased to 90 °C. So, it can be deduced that the reason why sun drying can decrease the colchicine content in daylily flower is not the heat effect but mainly the irradiation. It is also verified that a blanching treatment of fresh daylily flower is indispensable before following heat-drying in factory, by which the colchicine may be transferred into the water. Such a blanching treatment can effectively decrease the content of colchicine in daylily flower, therefore avoiding the toxicity of colchicine. Otherwise, the potential health risks of colchicine should remain in the dried product even after a long-term storage in dark [5–7].

Table 1.

Kinetics of colchicine photolysis affected by light source, solvent, pH and temperature (Initial Concentration., 10 µg/mL. Visible light., tungsten lamp, 200 W. UV, 8 W)

| Temp. (℃) | pH | solvent | light source | kinetic equation | K (h− 1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 4 | water | Vis. | ln[C] = 2.2859-0.0309t | 0.0309 |

| 25 | 10 | water | Vis. | ln[C] = 2.2819-0.0337t | 0.0337 |

| 25 | 7 | water | Vis. | ln[C] = 2.2478-0.0377t | 0.0377 |

| 5 | 7 | water | Vis. | ln[C] = 2.3122-0.0329t | 0.0329 |

| 60 | 7 | water | Vis. | ln[C] = 2.3150-0.0332t | 0.0332 |

| 25 | 7 | water | UV | ln[C] = 2.3531-0.0903t | 0.0903 |

| 25 | - | ethanol | Vis. | ln[C] = 2.2649-0.2861t | 0.2861 |

| 25 | - | ethanol | UV | ln[C] = 2.5169-0.5862t | 0.5862 |

| 90 | 7 | water | dark | - | 0 |

| 25 | 4 | water | dark | - | 0 |

| 25 | 10 | water | dark | - | 0 |

| 25 | - | ethanol | dark | - | 0 |

Product of colchicine photolysis

The retention time (RT) of colchicine was 15.92 min under tested LC conditions. After 2 h of irradiation by tungsten lamp, colchicine remained in the LC spectra while a derivative (compound A) was observed at 16.76 min (Fig. 4a). With the extension of illuminating time, the relative abundance of colchicine decreased gradually in LC chromatogram, accompanied by an increasing abundance of compound A (data not shown). This observation is consistent with previous UV-Vis scan showing a gradual formation of a new compound as colchicine was consumed. After 30 h of irradiation, the abundance of compound A increased greatly, but colchicine was no longer observed (Fig. 4b). Meanwhile, the LC spectra displayed another derivative (Compound B, Fig. 4b) at 16.33 min. The MS spectra of compound B gave a pseudo-molecular ion peak at m/z 400.06 (M+, Fig. 4c), suggesting the same molecular weight (MW) as that of colchicine (MW 399). From the chemical point of view, the tropolone ring (C-ring) of colchicine is the most light-sensitive portion of the molecule, on which photochemical rearrangement and isomerization transformation may occur under irradiation. Considering this fact, compound B can be preliminarily identified as lumicolchicine (Fig. 4c) based on its MW and UV spectra, and it was most likely produced by the ring contraction of the tropolone moiety [26]. Compound A should be the major photolysis product of colchicine, and it displayed a pseudo-molecular ion peak at m/z 341.03 (M+, Fig. 4d). This MW was consistent with the structure of a deacetamido derivative of colchicine, which was generated from the breakdown of the C-N bond together with the formation of a double bond at the seven-membered B-ring. Consequently, the photolysis product (compound A) can be tentatively identified as deacetamido-lumicolchicine (Fig. 4d). Lumicolchicine was known as the photoproduct of colchicine. However, observations above proved that it may further degrade with a loss of acetamide group under irradiation.

Fig. 4.

LC/MS analysis of colchicine (20 µg/mL in PBS) under visible light (tungsten lamp, 200 W. Figure 4a, irradiated for 2 h. Figure 4b, irradiated for 30 h. Figure 4c, MS of compound B. Figure 4d, MS of compound A)

The cytotoxicity of colchicine before and after photolysis

Regardless of whether colchicine was photolyzed or not, it showed certain toxicity to BRL 3 A cells, and a higher concentration indicated a stronger toxicity (Fig. 5). Comparatively, the cells treated with colchicine had lower viability than those when the colchicine was exposed to UV irradiation for 24 h. The IC50 value of colchicine to BRL 3 A cells was calculated as 0.48 µg/mL, while the UV irradiation could increase the IC50 value to 2.1 µg/mL. These observations suggested that the toxicity of colchicine to BRL 3 A cells could be weakened by a photolysis treatment. Such weakening effect was much more remarkable when colchicine ranged from 0.31 µg/mL to 2.5 µg/mL (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Viability of BRL 3 A cells affected by colchicine before and after UV irradiation (8 W, 24 h. Result was as a percentage of control. *P < 0.01, **P < 0.0001)

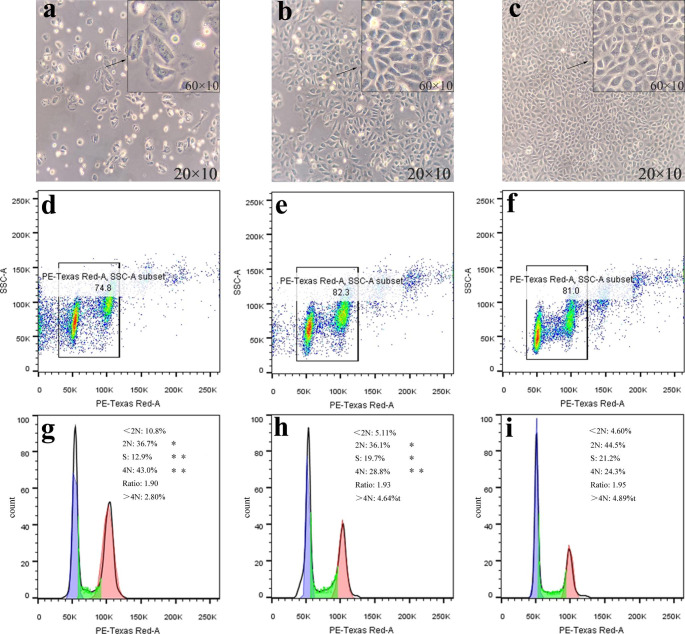

A colchicine solution at 1.25 µg/mL was further used for cell cycle assay, and the results were shown in Fig. 6. After incubation with colchicine before and after irradiation, the living BRL 3 A cells in both cases showed a decrease in number (Fig. 6a-c). But, in comparison with the colchicine group without UV exposure, the group with UV irradiation had more living cells, which was in agreement with the result of the viability analysis above. In addition, the cells of the irradiation group comparatively maintained better morphology. The colchicine group was detected to have more cell debris (< 2 N: 10.8%) than the irradiation group (< 2 N: 5.11%) and control (< 2 N: 4.60%) (Fig. 6d-f). The population percentage of cells in the G2/M phase was 24.3% in control, while the tested groups with colchicine before and after photolysis had 43.0% and 28.8% of cells in the G2/M phase, respectively (Fig. 6g-i). The observations indicated that the presence of colchicine significantly inhibited the division of BRL 3 A cells in the G2/M phase, while this inhibition could be reduced when colchicine was photolyzed.

Fig. 6.

Cell cycle progression of BRL 3 A cells affected by colchicine before and after UV irradiation (Conc., 1.25 µg/mL. 8 W, 24 h. Figures a-c, cell photograph. Figures d-i, cell cycle distribution. Figures a, d and g were before irradiation, Figures b, e and h were after irradiation, Figures c, f and i were of PBS control. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01)

Both cell viability and cell cycle studies proved the toxicity of colchicine, and after photolysis, the toxicity was found to be weakened. Numerous studies have reported the structure-activity relationships of colchicine [20, 27]. The observed toxicity of colchicine was attributed to that it can bind to tubulin, considering the fact that tubulin plays a crucial role in many biological processes for living cells. There is no doubt that the toxicity decrease due to irradiation is closely associated with the structure change of colchicine. HPLC-MS analysis indicated that the main photoproduct of colchicine was deacetamido-lumicolchicine. In comparison with the molecular structure of colchicine, the photoproduct has one less acetamide group on ring B and ring C occurs with isomerization, as discussed above. Such structure change should result in a lowered binding with cell tubulin [20, 27], suggesting that the photoproduct of colchicine was less toxic against tested cells. The harvest period of the daylily flower is very short, which is usually half a month. So, in the rural areas of many Asian countries, the harvested daylily flower is widely exposed to strong sunshine irradiation in order to remove the moisture before storage. It is commonly found that, unlike fresh daylily flowers, the sun-dried one hardly leads to food safety incidents. The reason is just that, not only the moisture was removed during the drying process, but the degradation of colchicine in daylily flowers under sunshine irradiation could effectively reduce the possible toxicity to the human body.

Conclusion

Colchicine was unstable to light irradiation, which was remarkably affected by light source and solvent. The photoproduct was preliminarily identified as deacetamido-lumicolchicine, namely a deacetamido derivative of colchicine with a ring contraction occurring at the tropolone moiety in the molecule. The photolysis process conformed to first-order kinetics, in which the alcoholic solution of colchicine could reach a high degradation rate under UV irradiation. Colchicine was toxic to BRL 3 A cells, but the toxicity could be effectively reduced by photolysis treatment. Results provided the mechanism of the toxicity elimination of colchicine by light irradiation, and could promote the proper treatment of daylily flower in agricultural production and food processing in consideration of food safety.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by Basic Research Programs of Sichuan Province (2020CDDZ-13). We appreciate Dr. Bo Gao from the Analytical & Testing Center of Sichuan University for helping the LC-MS characterization.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interest or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mao LC, Pan X, Que F, Fang XH. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2006;222(3):236–241. doi: 10.1007/s00217-005-0007-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hao Z, Liang L, Liu H, Yan Y, Zhang Y. Molecules. 2022;27(9):2964. doi: 10.3390/molecules27092964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu WT, Mong M, Yang Y, Wang Z, Yin M. J. Food Sci. 2018;83:1463–1469. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.14137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu W, Zhao Y, Sun J, Li G, Shan Y, Chen P. Food Res. Int. 2017;102:493–503. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2017.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirayama I, Hiruma T, Ueda Y, Doi K, Morimura N. J. Med. Case Rep. 2018;12(1):191. doi: 10.1186/s13256-018-1737-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mulkareddy V, Sokach C, Bucklew E, Bukari A, Sidlak A, Harrold IM, Pizon A, Reis S. JACC: Case Rep. 2020;2(4):678–680. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Panziera W, Schwertz CI, Henker LC, Konradt G, Bassuino DM, Rodrigues R, Driemeier D, Sonne L. Acta Sci. Vet. 2019;357:5. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu B, Xu T, Li YP, Yin X, Cochrane DB. Syst. Rev. 2022;3:10893. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010893.pub4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roth ME, Chinn ME, Dunn SP, Bilchick KC, Mazimba S. Clin. Cardiol. 2022;45:733–741. doi: 10.1002/clc.23830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin ZY, Yeh ML, Huang CI, Liang PC, Hsu PY, Chen SC, Huang CF, Huang JF, Dai CY, Yu ML, Chuang WL. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022;153:113540. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gorial FI, Maulood MF, Abdulamir AS, Alnuaimi AS, Abdulrrazaq MK, Bonyan FA. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022;77:103593. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2022.103593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanghavi D, Bansal P, Kaur IP, Mughal MS, Keshavamurthy C, Cusick A, Schram J, Yarrarapu SNS, Giri AR, Kaur N, Franco PM, Abril A, Aslam F. Ann. Med. 2022;54:775–789. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2021.1993327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma XY, Zhu BQ, Yang Z, Jiang YH, Mei XF. CRYSTENGCOMM. 2021;23:30–34. doi: 10.1039/D0CE01551B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bussotti L, Cacelli I, Cacelli M, Foggi P, Lesma G, Silvani A, Villani V. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2003;107:9079–9085. doi: 10.1021/jp035507l. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghanem R, Baker H, Seif MA, Qawasmeh RAA, Mataneh AA, Gharabli SIA. J Solut. Chem. 2010;39(4):441–456. doi: 10.1007/s10953-010-9515-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Go HC, Low JA, Khoo KS, Sit NW. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2021;15:3962–3972. doi: 10.1007/s11694-021-00981-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adeniran AA, Sonibare MA, Food Meas J. Charact. 2017;11:685–695. doi: 10.1007/s11694-016-9438-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ergul M, Bakar-Ates F. Toxicol. in Vitro. 2021;73:105138. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2021.105138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Z, Liu RL, Zhang X, Chang X, Gao MH, Zhang S, Guan Q, Sun J, Zuo DY, Zhang WG. Bioorgan Med. Chem. 2022;58:116671. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2022.116671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gracheva IA, Shchegravina ES, Schmalz HG, Beletskaya IP, Fedorov AY. J. Med. Chem. 2020;63(19):10618–10651. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marquez JJR, Levchuk I, Ibañez PF, Sillanpää M. J. Clean. Prod. 2020;258:120694. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120694. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu J, Li J, Cui J, An W, Liu L, Liang Y, Cui W. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020;384:121399. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tran ML, Fu CC, Juang RS. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 2019;26(12):11846–11855. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-04683-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Attri P, Kim YH, Park DH, Park JH, Hong YJ, Uhm HS, Kim KN, Fridman A, Choi EH. Sci. Rep-UK. 2015;5:9332. doi: 10.1038/srep09332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang L, Chen Y, Chen B, Yang J. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021;404:124040. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nery ALP, Quina FH, Moreira PF, Jr, Medeiros CER, Baader WJ, Shimizu K, Catalani LH, Bechara EJH. Photochem. Photobiol. 2007;73:213–218. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2001)0730213DTPCOC2.0.CO2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghawanmeh AA, Bajalan HMA, Mackeen MM, Alali FQ, Chong KF. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020;185:111788. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]