Summary

Single cell RNA-sequencing and in vivo functional-imaging provide expansive but disconnected views of neuronal diversity. Here we developed a strategy for linking these modes of classification to explore molecular and cellular mechanisms responsible for detecting and encoding touch. By broadly mapping function to neuronal class, we uncovered a clear transcriptomic logic responsible for the sensitivity and selectivity of mammalian mechanosensory neurons. Notably, cell-types with divergent gene-expression profiles often shared very similar properties but we also discovered transcriptomically related neurons with specialized and divergent functions. Applying our approach to knockout mice revealed that Piezo2 differentially tunes all types of mechanosensory neurons with a marked cell-class dependence. Together our data demonstrate how mechanical stimuli recruit characteristic ensembles of transcriptomically defined neurons providing rules to help explain the discriminatory power of touch. We anticipate a similar approach could expose fundamental principles governing representation of information throughout the nervous system.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Sensory neurons innervating the skin provide animals with important details about their environment and induce complex behavioral, motor and emotional responses to a range of stimuli including temperature and touch. These neurons, localized to the trigeminal and dorsal root ganglia, have been classified using anatomy, genetics, physiology, biochemistry, according to their functional tuning and by the responses they provoke (Abraira and Ginty, 2013; Basbaum et al., 2009; Julius, 2013; Le Pichon and Chesler, 2014). Although some modalities like cooling (Bautista et al., 2007; Dhaka et al., 2007) or itch (Abraira and Ginty, 2013; Mishra and Hoon, 2013) may be encoded by dedicated neurons that serve as labeled lines, it is believed that most types of mechanical stimuli activate broad and overlapping populations of differentially responsive cells to trigger percepts (Norrsell et al., 1999). Indeed, the human sense of touch exhibits a tremendous range of sensitivity: detecting the bending of a single hair but still discriminating intensity even after a stimulus becomes painful (Hill and Bautista, 2020). At the same time, it provides exquisite positional information and temporal resolution as well as a multitude of qualities (e.g. sharpness, roughness or compliance). Most naturalistic stimuli are extremely complex, for example a breath of wind may ruffle hairs, vibrate the skin and rapidly evolve in terms of direction, speed and intensity but both the nature of the stimulus and its features can be instantaneously and unambiguously recognized. How does the activity of the different types of sensory neurons combine to provide us with this remarkable perceptual power?

Recently single cell (sc) RNA-sequencing added a new dimension to understanding the diversity of the nervous system by classifying neurons according to the expression of hundreds of genes (Tasic et al., 2018; Zeisel et al., 2018). In the somatosensory system, many of the sc-transcriptomic classes define cell types that had previously been studied using genetic strategies supporting the premise that they encode functional types of cells (Nguyen et al., 2017; Sharma et al., 2020; Usoskin et al., 2015). Moreover, comparison between dorsal root and trigeminal ganglia reveals a set of tightly conserved cell types that provide a minimal framework for classifying these cells (Gatto et al., 2019; von Buchholtz et al., 2020). In parallel, advances in functional imaging have provided a way to characterize large groups of neurons according to their activity (Ghitani et al., 2017; Szczot et al., 2018; Yarmolinsky et al., 2016). One approach for associating function with gene expression relies on restricting expression of genetically encoded calcium indicators (e.g. GCaMP) to select subsets of neurons (Chang et al., 2015; Ghitani et al., 2017; Williams et al., 2016). Other strategies involve single cell sequencing after functional recordings (Cadwell et al., 2016) or functional tagging (Lee et al., 2019). However, naturalistic stimuli produce highly complex neuronal activity patterns. Thus, in a more ideal scenario, transcriptomic class of all the responding neurons would be determined and directly matched to function at a single cell level. We reasoned that molecular profiling after Ca-imaging should link these different types of classification, broadly map function to transcriptomic class and reveal how features of mechanical stimuli are detected and represented by the somatosensory system.

The neurons responsible for detecting touch in mice fall into at least 5 broad categories (Abraira and Ginty, 2013; Hill and Bautista, 2020; Zimmerman et al., 2014) reflecting their degree of myelination and conduction velocity (unmyelinated, c; medium, Aδ; and high, Aβ) and also their sensitivity (high or low threshold mechanoreceptors, HTMRs or LTMRs, respectively). These groups are also distinguished at the transcriptomic level: in the trigeminal ganglion cLTMRs have been referred to as C3 cells; Aβ-LTMRs as C4; Aδ-LTMRs as C5; Aδ-HTMRs as C6; and c-fiber nociceptors (including HTMRs), a range of classes from C7-C13 (Nguyen et al., 2017). Of these, the C4 Aβ-LTMRs are known to be physiologically and anatomically variable. For example, they exhibit a range of adaptation rates (e.g. slowly or rapidly adapting; SA or RA), diverse terminal specializations (e.g lanceolate or circumferential endings) as well as distinct receptive tuning profiles (Bai et al., 2015; Ghitani et al., 2017; Rutlin et al., 2014; Zimmerman et al., 2014). Consistent with this heterogeneity, the C4 class (Aβ-LTMRs) can be divided into many transcriptomic subgroups (Nguyen et al., 2019; Sharma et al., 2020). However, how these different types of somatosensory neurons combine to represent and distinguish a gentle brush, or a pinch remains largely unknown.

We recently showed that multiplex in situ hybridization (ISH) using just eight genes could be used to distinguish the major classes of trigeminal neurons (von Buchholtz et al., 2020). Based on this approach we have now developed a platform for assigning transcriptomic class to large ensembles of functionally characterized neurons and use it to reveal important features and mechanistic detail about the sense of touch.

Results

Matching functionally distinct classes of neurons with their molecular expression profile is a fundamental problem throughout neuroscience. Recently, we developed a GCaMP6f-based approach for measuring the sensory responses of trigeminal neurons innervating the cheek (Ghitani et al., 2017; Szczot et al., 2018). Importantly, this type of Ca-imaging allows the functional tuning of hundreds of neurons to be determined simultaneously, is highly reliable with the same neurons responding reproducibly to the same type of stimulation and has single-spike sensitivity. In parallel we developed a multigene ISH methodology for decoding transcriptomic class in tissue sections (von Buchholtz et al., 2020). We reasoned that combining these techniques might provide a powerful strategy for determining not only how complex mechanical stimuli are represented by ensembles of neurons but also if responding cells are differentially tuned by virtue of their gene expression profiles.

A robust approach for aligning in vivo functional imaging to post-hoc ISH

Neonatal injection of adeno associated virus (AAV)-Cre into Ai95 (Rosa-LSL-GCaMP6f) mice provides an effective way of inducing GCaMP-expression in a large and representative subset of trigeminal neurons without excessive neuropil staining (Szczot et al., 2018). In vivo epifluorescence GCaMP-imaging of the trigeminal ganglion reveals the functional tuning of neurons at its exposed dorsal surface. After isolating the ganglion, a whole mount ISH preparation should provide information about gene expression in the same set of cells but tissue distortion confounds accurate alignment of the different images. We reasoned that if a red fluorescent protein marker could be detected during the functional imaging and also by whole mount ISH-imaging, these cells would act as fixed guideposts for image matching. To this end, we expressed a red fluorescent protein (tagRFP) in a subset of sensory neurons. The Tac1-tagRFP mouse-line that we chose provided four important features: first, fluorescent signal was readily detectable and resolved from GCaMP fluorescence in live mice; second, expression of this marker was dense enough to allow accurate alignment, but nonetheless sparse enough for resolution of single cells (Figure 1A); third, the endogenous tagRFP fluorescence was destroyed during ISH meaning that it did not interfere with hybridization signal detection; finally, Tac1 is a useful marker of a subset of nociceptive somatosensory neurons, thus its expression pattern contributes to the molecular characterization of cells.

Figure 1. Aligning in vivo imaging of large ensembles of neurons with whole mount ISH.

A) Example images of a dorsal view of the trigeminal ganglion showing red fluorescence in a live Tac1-tagRFP mouse (left panel, red) and whole mount tagRFP ISH from the excised ganglion (middle panel, green). Images were aligned using scaled rotation (right panel); note that only very few cells overlap but other non-aligned pairs of red and green neurons can be identified. B) Images were aligned by manual matching of cell pairs (left panel, arrows) to identify guideposts for Delaunay triangulation of the ISH image (middle panel) and construction of corresponding triangles in the live image (right panel). The aligned region is delimited by the triangles; affine transform of Delaunay triangles (see Figure S1) generates a continuous image (C) where a large area and many neurons are perfectly matched between the live image (red) and ISH (green). D) Imaging from a different mouse showing in vivo fluorescence of tagRFP (top left, red) and GCaMP6f calcium transients (green, see methods for details). The whole mount ISH counterpart (top right; tagRFP, cyan; GCamP6f, magenta) was aligned to the live image using tagRFP guideposts (bottom left). As a result, functional activity maps also matched the GCaMP6f expression (bottom right). Note that as expected only a subset of GCaMP6f expressing neurons responded to mechanical stimulation of the cheek; scale-bars = 100 μm; see also Figure S1.

Images from functional imaging and ISH (Figure 1A) illustrate that the wholemount ISH recapitulated the pattern of tagRFP detected in vivo but with significant regional distortions. Even with the tagRFP-guideposts, these differences prevented alignment using automated approaches based on simple transformations. To solve this issue, we manually matched guideposts between the two images (Figure 1B) and implemented an algorithm that splits the images into triangular sections where the guideposts serve as vertices (Figure 1B, Delaunay triangulation). The Delaunay triangles in the ISH image could then be warped into their target counterparts in the live image by affine transformation (Figure 1C). A related strategy is used in face-morphing (Figure S1A), which provided us with a framework for software development. Since Tac1-expression is dense and distributed in cells of the trigeminal ganglion, we typically could match large areas containing hundreds of neurons in multiple rounds of ISH imaging to their in vivo partners (Figure 1C) with accurate cellular resolution (Figure S1B,C) allowing us to map functional responses to GCaMP-expressing cells (Figure 1D). A similar approach could easily be developed to simultaneously determine the gene-expression profiles of ensembles of functionally characterized neurons in many regions of the nervous system.

Decoding the molecular signatures of neurons activated by naturalistic mechanical stimuli

Naturalistic mechanical stimuli including gentle brush, pinch, hair-pull, air-puff and vibration applied to a small region of cheek located between the whisker pad and the eye activated large sets of trigeminal neurons (Figure 2). These responses were robust, reliable and selective allowing neurons to be assigned to one of five categories (Figure 2A). We defined criteria (see Methods) based on maximum calcium responses to the stimuli for automatically classifying 1840 mechanosensory neurons from 23 mice. The heatmap and example traces of responses (Figure 2) confirm that this approach provides overall consistency while eliminating observer bias. Air-puff cells were rather selectively tuned but often also responded strongly to vibration; vibration cells only detected vibration; brush cells detected gentle brushing but typically also responded to high threshold stimulation and vibration; high threshold cells (HT-cells) were tuned to noxious stimuli (pinch and/or hair-pull) and showed at most very weak responses to brush or air-puff; finally we identified a group of mixed responders that detected air-puff, brush and high-threshold stimulation. About 40 % of mechanosensors were HT-cells, 35 % brush cells with the other three classes making up the remaining 25 % (Figure 2A). Notably, about 80% of the mechanosensory neurons were engaged by noxious stimuli including all brush cells and mixed responders. The skin is flexible meaning that hair pull and pinch affect wide areas of the face. Therefore, it would be expected that sensitive brush responsive neurons might be activated by distal noxious stimuli. Indeed, this is exactly what we found (Figure S2): brush cells respond to pinch at multiple locations on the cheek. By contrast HT-cells have smaller receptive fields to pinch. Interestingly, although air-puff, vibration and mixed responder cells appeared rather uniform in their calcium transients, the larger groups of brush cells and HT-cells were more functionally diverse (Figure 2B). For example, approx. 30% of the brush cells were vibration insensitive, half responded preferentially to lower frequency vibration and a smaller fraction were strongly activated by the full spectrum of vibration frequencies (Figure 2). Similarly, HT-cells exhibited differences in their sensitivity to hair-pull and their response dynamics (Figure 2B). This type of heterogeneity is consistent with previous results demonstrating the existence of several different classes both of low and high threshold mechanosensors (Abraira and Ginty, 2013; Ghitani et al., 2017; Hill and Bautista, 2020; Zimmerman et al., 2014). Taken together, our analysis highlights the value of using functional imaging for analyzing responses to naturalistic stimuli and reveals the existence of a novel class of mechanosensory neurons adapted for selective detection of air-puff.

Figure 2. Trigeminal neuron responses to naturalistic mechanical stimuli identify clear functional categories.

A) Heatmap showing the in vivo GCaMP6f responses from 1840 neurons responding to five types of mechanical stimulation as labeled (top) in 23 mice. Calcium transients were first normalized to the median pinch response in that animal and colored as indicated in the scale bar (inset). The five cell-categories (labelled colored boxes, with cell numbers) were assigned using an automated script and a set of thresholding rules. Note sharp boundaries in response profiles demarcate the categories highlighting robust differences in the tuning of these groups of cells. B) Representative example GCaMP-transients (ΔF/F fluorescence changes indicated by scale bars) for each category of cells showing responses of individual neurons to a series of air-puff durations, vibration frequencies, gentle brush strokes, vigorous hair-pulls and pinching (the order, approximate timing and repetitive nature is schematically represented by number scales or arrows). Note that responses to vibration are somewhat variable in all categories of LTMRs; see also Figure S2.

How are the five categories of mechanosensory neurons specified by the genes they express? To address this issue, we developed sets of robust probes for classifying neurons according to their transcriptomic profiles (see Figure S3 for explanation of diagnostic gene expression patterns) and aligned multiplex ISH images to the functional responses. Our approach and its specificity are illustrated in Figure 3 where a region of a trigeminal ganglion containing 48 responding cells is shown. In vivo GCaMP-imaging was used to assign a functional category to each of these cells (Figure 3A). Subsequent whole mount ISH, warped to match the functional imaging (Figure 3B), shows the combined expression of 6 diagnostic markers in this region of the ganglion. The expression profiles of select cells highlighted in Figure 3 panels A and B are enlarged and analyzed in detail (Figure 3C), showing the basis for transcriptomic classification of functionally categorized neurons. For example, the air-puff cell A1 corresponds with GCaMP-expression and also is positive for S100b but no other markers, defining it as a C4 cell (see Figure S3). By contrast, the HT-cell H2, again aligns with GCaMP-expression but does not contain S100b mRNA and instead expresses all the other markers shown, making it a C13 neuron. In this way 46 of the 48 responding neurons in this field could be classified (Figure 3D, Figure S4) and their response dynamics analyzed in detail with respect to their cell class (Figure 3E).

Figure 3. Multiplexed ISH aligned to functional imaging maps cellular responses to transcriptomic class.

A) Activity maps for 48 responding neurons in a region of the trigeminal ganglion shown in Figure S1C were color coded to distinguish their functional categories. B) Multiplex wholemount ISH was performed and images for 6 probes were aligned to the functional image using tagRFP guideposts; the overlaid 6 images were colored as indicated in the upper panel. Boxes (A) and (B) depict representative cells with a variety of distinct functional responses (A, air-puff cell, M, mixed responder B, brush cell and H, HT-cell) and gene expression patterns; scale bar = 100 μm. C) Activity map (left column) and detailed gene expression patterns for the cells boxed in (A) and (B) illustrate our strategy for assigning cell class to functionally characterized mechanosensory neurons (see also Figure S3). D) Map of transcriptomic classes of the responding cells; note in this imaging field 46 from 48 neurons were classified using this panel of genes (see also Figure S4 for details); the color code for classes is shown in the lower panel. E) GCaMP-transients for the cells boxed in (A) and (B) with transcriptomic class indicated. ΔF/F fluorescence changes are indicated by scale bars and traces are color coded according to transcriptomic class (as specified, D).

Transcriptomic classes selectively encode distinct mechanosensory features

We used the strategy of combining functional imaging and ISH to unambiguously assign transcriptomic class to more than 1000 of the 1830 mechanosensory neurons classified in 23 mice using definitive gene expression patterns. This comprehensive survey (Figure 4) exposed six fundamental principles for detection and representation of a range of salient mechanical stimuli at the periphery defining the transcriptomic basis for their discrimination. First, the vast majority of mechanosensors responding to low threshold stimuli (air-puff, vibration, mixed responders and brush cells) are C3, C4 and C5 neurons (Figure 4, Figure S5); responses in these neuronal classes are saturated by gentle stimuli. Second, C3 and C5 cells are both quite homogeneous in their tuning and are predominantly brush cells; despite their markedly different transcriptomic profiles, these two classes appear very similarly tuned. Third, most (> 80%) mechanosensory neurons are activated by stimuli that evoke pain, with all classes of brush cells and mixed responders reliably responding to pinch and hair-pull. Fourth, the C4 class encompassed the only mechanosensor categories (air-puff and vibration) not robustly activated during noxious stimulation. However, this cell class was heterogeneous, including not only air-puff and vibration cells but also half the mixed responders and a small fraction (12.5%) of the brush cells as well as an equal number of cells activated only by higher intensity stimuli (Figure 4C). Fifth, our data showed that classes C6-C13 (nociceptors) only very rarely responded to air-puff, vibration or brush (Figure 4, Figure S5) and represented more than 80% of HT-cells. Finally, C1/2 neurons (Trpm8-expressing) were essentially unresponsive to any mechanical stimulus with just 2 cells responding to air-puff (Figure S5).

Figure 4. Sweeping assignment of transcriptomic class to function reveals a cellular basis for the detection and coding of mechanosensation at the periphery.

A) Heatmaps showing normalized mechanical responses from transcriptomically classified neurons tested with the five stimuli (indicated above the heatmaps) grouped according to transcriptomic class. Data display is as in Figure 2A and functional category color coding is shown in (C); note that mechanical stimuli broadly activate all transcriptomic classes of neurons with the exception of C1/2 cooling sensors (see Figure S5A). Nonetheless, clear functional differences are immediately apparent with most classes selectively tuned to either brush or noxious stimuli. By contrast C4 Aβ-LTMRs are diverse and include the vast majority of the specialized air-puff and vibration cells. B) Example GCaMP-transients of each cell class (ΔF/F fluorescence changes indicated by scale bars; traces color coded according to functional category) highlight their different tuning characteristics. Differential vibration sensitivity and calcium transient dynamics are also class dependent (see Figure S5B-D). C) Quantification of response category across cell-class; data were normalized to the number of responding neurons tested for each class (numbers of class responders / responding cells tested for that class by ISH are also indicated).

The overarching conclusion from this broad classification of mechanosensory neurons is one of consistency: class determines function (Figure 4). However, a small fraction of cells showed atypical response profiles: part of this may be experimental as a result of using naturalistic stimuli. For example, differences in stimulation intensity and target are impossible to rule out. Thus, C3 or C5 HT-cells may simply reflect that the area brushed fell outside their receptive fields. Nonetheless, some of these outliers likely have a biological role: a small subgroup of C5 neurons, which are mainly brush cells, also respond to air-puff and are mixed responders in our classification scheme (Figure 4A, B). C5 Aδ-LTMRs are extremely uniform in their transcriptomic profile (Nguyen et al., 2017; Usoskin et al., 2015) and quite unique in the markers they express. Thus, their unexpected functional diversity further highlights the power of using an unbiased and comprehensive imaging-based approach. Conversely, the response heterogeneity of C4-neurons that we observed likely reflects the transcriptomic diversity of this class in recent scRNA sequencing (Nguyen et al., 2019; Sharma et al., 2020).

Does the classification of cells responding to the different naturalistic stimuli begin to explain how touch stimuli might be distinguished from one another? At the most fundamental level, LTMRs and HTMRs are defined by their genetic profiles (Figure 4). However, the majority of LTMRs respond to a wide range of naturalistic stimuli and indeed often have extended receptive fields for noxious hair-pull and pinch (Figure S2). By contrast, air-puff and vibration cells are unusually selective and do not respond to hair-pull, pinch or gentle brushing. Our data demonstrate that both these functional categories are narrowly tuned C4 Aβ-LTMRs (Figure 4) insinuating them as labeled lines that could allow an animal to unambiguously identify these types of stimuli. The high specificity of air-puff cells was particularly unexpected: in the past air-puff has only been shown to activate a population of rapidly adapting Aβ-LTMRs that detect a wide range of mechanical deflections of the hair including brushing and make lanceolate endings in the skin (Bai et al., 2015). These RA-Aβ-LTMRs have functional properties and a genetic profile matching the C4 mixed responder category that we identified here (Figure 4); intriguingly, C5 Aδ-LTMRs also make lanceolate endings and, as noted above, a subset of these cells exhibited a similar mixed responder profile.

The other category of LTMRs, the brush cells, were more variable in their gene expression profiles but primarily fell into three transcriptomic classes, C3-C5 (Figure 4). This complex representation of brush is completely consistent with several elegant studies that examined individual responses of select types of cell in the DRG (Bai et al., 2015; Rutlin et al., 2014) and nicely demonstrates how single brush strokes simultaneously activate tens to hundreds of transcriptomically heterogeneous neurons to provide a peripheral representation of this stimulus. Notably, when brush cells were separated by class, a logic explaining the differences in their response properties began to emerge (Figure 4B, Figure S5). For example, C4-brush cells exhibited staccato calcium transients to brush, hair-pull and pinch, with each stimulus event resolved (Figure S5). In contrast, responses tended to be more sustained in their C3 and C5 counterparts (Figure S5). Vibration responses were also transcriptomic class dependent and again were largely observed in C3-C5 cells (Figure 4). Notably, unlike for brush, C3-cells were relatively insensitive to vibration and rarely responded to frequencies above 100 Hz (Figure 4A,B). Therefore, although C3, C4 and C5 brush cells detect broadly overlapping stimuli these neurons transmit different information to the next station in the sensory pathway.

High intensity mechanical stimuli provide crucial information for survival by activating nociceptors that trigger protective behavioral responses and evoke acute pain. Most HT-cells were C6 Aδ-nociceptors or C13 non-peptidergic c-nociceptors, with C11/C12 (itch-related) neurons (Abraira and Ginty, 2013; Mishra and Hoon, 2013) making up an additional and surprisingly large group. These classes are all strongly positive for the Nav1.8 sodium channel (Scn10a) reflecting the key role of this channel in mechanical nociception (Abrahamsen et al., 2008). Interestingly, just as we had observed for C3 and C4 brush cells, the clearest distinction between c- and A-fiber nociceptors was in the dynamics of their responses (Figure 4B, Figure S5B-D). Indeed, quantitative analysis demonstrated that responses of C13 neurons decayed significantly more slowly than those of C6 cells (Figure S5C,D).

Genetic identification of a class of neurons that respond selectively to air-puff and vibration

Air-puff cells represent a new type of mechanosensor with highly specialized properties: strong responses to relatively gentle deflection of hairs by air flow and vibration but not brushing the fur or noxious stimuli like hair-pull and pinch. Previously, elegant genetic strategies have revealed important information about the tuning and anatomy of select types of mechanosensory neurons (Abraira and Ginty, 2013; Zimmerman et al., 2014). Just like many of these mechanosensors, the air-puff cells are C4 Aβ-LTMRs (Figure 4), a large and transcriptomically diverse set of neurons. Therefore, we reasoned that markers defining air-puff cells might be revealed by screening the responding cells for expression of genes mapping to C4-subtypes (Nguyen et al., 2019). Indeed, this approach revealed that a subset of the air-puff cells expressed the calcium binding protein calretinin (Calb2, Figure 5A,B). By contrast, this marker very rarely labeled mixed responders, brush or HT-cells (Figure 5B,C).

Figure 5. Calretinin (Calb2) expression defines a subtype of Aβ-LTMRs selectively tuned to air-puff and vibration.

A) UMap representation of snRNA sequence data (Nguyen et al., 2019) showing that Calb2 expression is restricted to a transcriptomically defined subgroup of C4 Aβ-LTMRs (dark blue); the expression of Calb2 (yellow) is overlaid on the classified cells; see also Figure S6. B-C) Calb2-Aβ-LTMRs are highly selective for air-puff and vibration; B) sample images showing ISH localization of Calb2 (green) overlaid on category specific spatial activity maps (red). Arrowheads highlight the Calb2-expressing cells with air-puff and vibration response profiles; note only a subset of air-puff or vibration cells express this marker and that many Calb2 cells are not stimulated, likely reflecting their projections to different areas of the head and neck. C) Heatmap showing the response profiles of all 37 responding Calb2-Aβ-LTMRs identified by ISH after functional imaging in 10 mice. D) Representative fluorescence micrographs of Calb2-Aβ-LTMR termini in the skin illustrating that these neurons form circumferential endings around small hairs. Neurons were labeled by tdT-expression (Calb2-Cre/Ai9 RCL-tdT mice with appropriate recombination, see also Figure S6); signal is shown in black and contrasts with the weaker autofluorescence of hairs allowing morphology to be clearly discerned. These neuronal termini are not limited to the cheek (left panel) but are also prominent in the nearby whisker pad (center left) and back skin (right panels); scale bars = 100 μm.

Using the multiplex ISH approach we demonstrated that 30 % of air-puff cells (23 from 76 responders) expressed the gene Calb2; 23 % of vibration cells (9 / 39) were also positive suggesting that a subset of vibration cells are air-puff cells with receptive fields outside the region that we stimulated. Importantly the vast majority of the responding Calb2-Aβ-LTMRs (approx. 90 %) were activated just by these two stimuli that both cause repetitive fluctuation of hairs (Figure 5C). The specificity and the functional homogeneity of Calb2-Aβ-LTMRs fits nicely with Calb2 marking a small transcriptomically distinct subgroup of C4 neurons (Figure 5A, Figure S6A).

We next set out to determine if specific anatomic features of Calb2-Aβ-LTMRs might account for their unusual response properties. To do this we used a well-characterized Calb2-Cre knockin mouse line (Taniguchi et al., 2011) to genetically target these cells by crossing it into Rosa-Cre-reporter backgrounds. We observed markedly variable recombination in the trigeminal ganglion using this line regardless of breeding strategy. For some mice recombination and expression of reporter-genes was detected in many sensory neurons with a wide range of diameters. In others, just a few large diameter neurons were labeled in keeping with the Calb2-expression profile (Figure S6A,B). Variability is a relatively common and well-documented problem with Cre-based labeling strategies most likely reflecting stochastic expression of Cre during development (Luo et al., 2020). We tested whether mice with sparse recombination labeled the appropriate cells: only a small subset of Calb2-positive cells expressed the reporter (Figure S6B) but all labeled cells (in sections from 5 ganglia) expressed Calb2 and therefore provided high-specificity for directed functional and anatomical studies.

Genetically targeted expression of GCaMP6f in Calb2-neurons confirmed that the labeled neurons selectively responded to air-puff and vibration but are rarely activated by gentle brush or high threshold mechanical stimuli (Figure S6C). Of 61 cells recorded in 4 mice, 51 (83 %) were air-puff / vibration cells confirming our initial findings and validating the genetic targeting approach. Notably, the majority of air-puff responding cells responded continuously for the duration of the stimulus (max. 5 s tested, Figure S6D) without adaptation or inactivation. This suggests that Calb2-Aβ-LTMRs are not only specialized to respond selectively to repetitive stimuli but also must be able to sustain this response for extended periods of time.

We then studied the anatomical projections of this class of neuron in hairy skin (Figure 5D) using Calb2-Cre to drive tdTomato (tdT) expression. To our surprise, we only observed distinctive circumferential endings targeting fine hairs in the cheek, whisker pad and back skin of these mice (Figure 5D). Previous studies have demonstrated that field-LTMRs (Bai et al., 2015) and circ-HTMRs (Ghitani et al., 2017) exhibit this type of terminal specialization around hairs but neither responds to air-puff. Instead both field-LTMRs and circ-HTMRs are particularly sensitive to hair-pull (Bai et al., 2015; Ghitani et al., 2017), which is not detected by Calb2-Aβ-LTMRs. Given their anatomic specialization, we suspect that Calb2-Aβ-LTMRs selectively respond to high-frequency and distributed deflection of small hairs either caused by airflow or repetitive skin motion. We propose that their selectivity results from rapid adaptation to sustained stimulation and in keeping with this hypothesis we detected very brief weak responses to brush, pinch and hair-pull in a number of cells (Figure S6D). In the future, it will be important to determine if the other C4 air-puff cells not marked by expression of Calb2 share anatomic, gene expression or biophysical properties (Zheng et al., 2019) with the Calb2-Aβ-LTMRs and thus help explain their unusual stimulus-response profile.

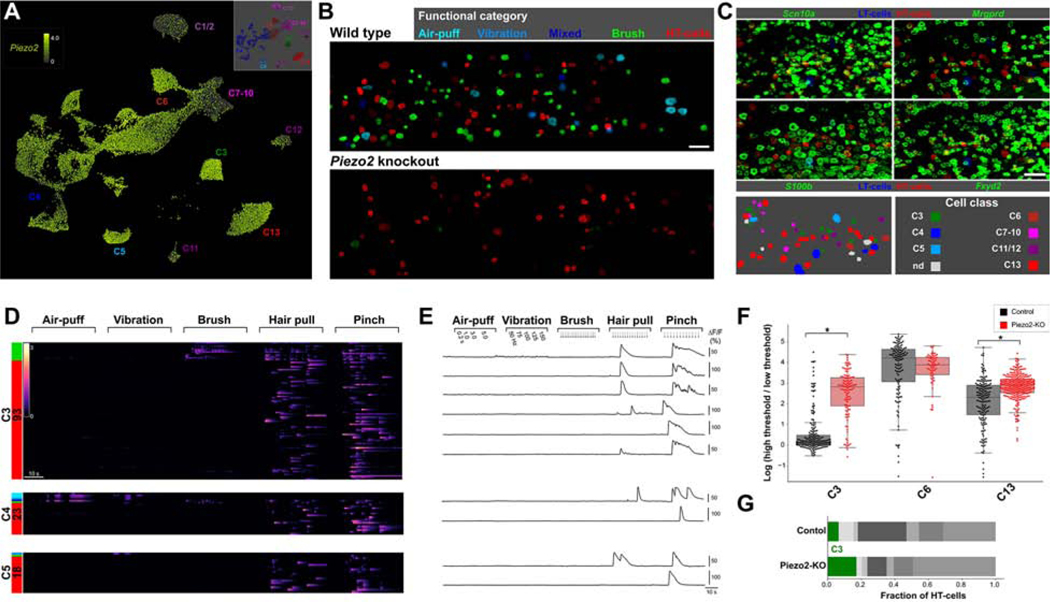

Class specific functions of Piezo2 in mechanosensation

We next explored the molecular mechanisms responsible for the differential response properties of the various transcriptomic classes. Recent studies have demonstrated that the tension-gated ion channel Piezo2 is required for detection of gentle touch, vibration and proprioceptive stimuli by mice and humans (Bai et al., 2015; Chesler et al., 2016; Coste et al., 2010; Ranade et al., 2014). Piezo2 is broadly expressed in almost all classes of trigeminal neurons including nociceptors (Figure 6A). Knockout of Piezo2 in nociceptors alters spike frequencies but these animals still respond to noxious mechanical stimuli (Murthy et al., 2018; Szczot et al., 2018). Similarly, humans with complete loss of PIEZO2 function report normal mechanical pain sensation in response to noxious pinch, pinprick and pressure (Chesler et al., 2016; Szczot et al., 2018). Therefore Piezo2-independent pathways for detecting stronger mechanical forces must exist. To determine the roles and relative contributions of these sensory mechanisms we investigated how the representation of touch was changed in each of the transcriptomic classes following Piezo2-knockout (Figure 6, Figure 7).

Figure 6. Piezo2 differentially confers mechanosensitivity to LTMR classes.

A) UMap representation of snRNA sequence data (Nguyen et al., 2019) showing broad expression of Piezo2 in almost all classes of trigeminal neurons; note that only a limited subset of C1/2 and C7–12 class neurons express this gene; by contrast it is a prominent marker of C6 and C13 nociceptors. B) Representative spatial activity maps showing the functional categories of mechanosensory neurons in equivalent areas of the dorsal trigeminal ganglion in control and Piezo2-KO recordings. Cellular response magnitude (see methods) is indicated by brightness and functional category by color; note how the functional response spectrum is narrowed by Piezo2 knockout. C) Example images showing ISH images (green) aligned to activity maps as indicated by color coding (top four panels) as well as the classified cells (lower left) in Piezo2-KO. D) Heatmaps showing mechanosensory responses for the three classes C3, C4 and C5 that normally encompass LTMRs after Piezo2-KO. Functional category (colored bars) and number of cells of a given class are indicated. Note that whereas almost all C4 and most C5 cells are silenced by Piezo2-KO many C3 neurons appear transformed from brush cells in control animals (Figure 4) to HT-cells (see Figure S7 for quantitation and detail). E) Representative GCaMP-transients illustrating the lack of responses of C3 - C5 neurons to gentle mechanical stimuli but robust activation of select neurons by hair-pull and pinch after Piezo2-KO. F) Box and whisker plot comparing the mechanical tuning of C3-cLTMRs with C6- and C13-HTMRs in control and Piezo2-KO recordings. Points represent the ratio for the maximum response of individual cells to pinch or hair-pull to gentle brush or air-puff (plotted on a natural log scale). Note that in control animals (black) C3-responses are generally saturated by low threshold stimuli with ln(ratio) near 0 and are thus distinct from HT-cells. After Piezo2-KO (red) most mechanosensitive C3 neurons are HT-cells; * indicates p < 10−20, Welch’s t-test with Holm-Šídák correction for multiple tests. As a consequence of this functional transformation stacked bar graphs (G) show that the proportion of C3 cells (green) amongst HT-cells nearly triples after Piezo2-KO; scale-bars = 100 μm.

Figure 7. Transcriptomic class dependent roles for Piezo2 in mechanical nociception.

A) Typical multiplex ISH images from sections of the trigeminal ganglion show robust expression of Piezo2 in both C13 and C6 neurons that represent mechanonociceptors. Top panel shows co-expression of Piezo2 (green) with Mrgprd (magenta) in C13 non-peptidergic nociceptors; bottom panel identifies a subset of C6 Aδ-HTMRs by their co-expression of S100b (red) and Calca (blue). Also shown (middle panels) are the individual images; arrowheads highlight a subset of nociceptors expressing Piezo2; scale bar = 100 μm. B) Heatmaps and (C) GCaMP-transients showing mechanosensory responses for mechano-nociceptors after Piezo2-KO. Note the large proportion of C13 HTMRs and their very homogeneous response profiles. Indeed quantitation (stacked bar graph, D) reveals that after Piezo2-KO, C13 neurons are now the dominant class of HT-cells and that unexpectedly the proportional representation of C6 Aδ-HTMRs was reduced by a factor of 2.5 relative to the control; see also Figure S7. (E-G) Individual hair pull responses were analyzed to evaluate the receptive field size of classified neurons to this stimulus both in control cells and after Piezo2-KO. (E) Shows the location of hair pulls across the cheek during a typical recording from a control animal and (F) the corresponding hair pull calcium transients of all neurons in that animal (grey overlaid traces). Pink dots represent computer determined maxima and blue bars are the corresponding peristimulus time histograms demonstrating that the different hair pulls can be reliably identified from the data. (G) The number and magnitude of calcium transients in every hair pull responsive neuron was used to calculate its receptive field index (RFI); low RFI indicates a narrow receptive field, see Quantification and Statistical analysis for details. Shown are the RFI distributions for the major classes of mechanosensor in control (grey bars) and after Piezo2-KO (pink bars). Note the receptive fields of brush sensitive C3 and C5 neurons were broader than for C6 and C13 HT-cells in control cells; after Piezo2-KO C3 and C5 neurons had lower RFIs (p = 4.5 × 10−8 and 2.2 × 10−4, respectively) whereas C6 and C13 RFIs were unaffected (p = 0.22 and 0.07, respectively).

We recently developed a versatile strategy for imaging the functional responses of neurons lacking Piezo2-expression that involves AAV-Cre mediated knockout just in the neurons expressing GCaMP (Szczot et al., 2018). This approach was easily rendered compatible with our platform for ISH after functional recordings by crossing the reporter mice into a conditional Piezo2-KO background. As expected, knockout of Piezo2 dramatically alters mechanosensation by essentially eliminating responses to gentle stimuli (Figure 6B-E, Figure S7A). In wild type controls C4-neurons represented all five functional categories with approximately 85 % being LTMRs. Amongst these LTMRs, air-puff and vibration cells normally accounted for nearly half of the C4 responsive neurons and only responded to these types of gentle mechanical stimulation (Figure 4). As expected, these cells were almost completely silenced after Piezo2-knockout (Figure 6D,E, Figure S7C). More interestingly, the C4 brush and mixed responder cells, which in control animals are also activated by noxious pinch and hair-pull were also silenced; i.e. they were not transformed to a corresponding set of C4-HT-cells (Figure 6, Figure S7). Similarly, C5-class (Aδ-LTMR) brush and mixed responding cells were also extensively silenced (Figure 6, Figure S7). Thus, Piezo2 is the essential mechanosensor for touch detection by these myelinated neurons and endows them with sensitivity to a wide range of stimuli including some that are noxious to the animal like hair-pull and pinch.

In wild type mice, C3 cLTMRs are mainly brush cells and exhibit similar sensitivity and tuning to their myelinated C4 and C5 counterparts. However, many C3 cells remained mechanosensitive after Piezo2 knockout but, for the most part, now just responded to high threshold stimuli making these neurons a new type of HT-cells (Figure 6D-G, Figure S7). This indicates that C3 neurons must possess at least two distinct types of transduction pathways. Closer examination of the responses of C3 cells in the knockout reveals that responses to high threshold stimuli showed altered dynamics (Figure S7B). In control animals, a series of hair-pulls generally evokes responses that track each event; in marked contrast, the same stimulation paradigm predominantly elicits a single slowly adapting transient in the mutant cells reminiscent of wild type C13 (cHTMR) responses (compare Figure S5C and Figure S7B). This was also reflected in a profound narrowing of the C3 receptive field to hair pull (Figure 7E-G). Taken together these results strongly suggest that Piezo2 not only sets the threshold for mechanosensation in C3 neurons but also contributes to their detection of high intensity stimuli. The unknown mechanosensory transduction pathway exposed in knockout C3 cells is less sensitive and likely endows cLTMRs with an extended dynamic range in wild type mice.

Piezo2 is prominently expressed in many HTMRs as well as LTMRs (Figure 6A, Figure 7A) raising the question of its importance in mechanical nociception. Our data demonstrate that C13 nociceptors become by far the largest class of mechanosensors after Piezo2-knockout, doubling their representation amongst responding neurons (Figure 7, Figure S7C). Thus, Piezo2 independent mechanisms must play a dominant role for the mechanosensitivity of this cell class. Nonetheless, rare C13-neuron responses to brush in wild type mice (Figure 4) were eliminated after Piezo2 knockout, demonstrating that this ion channel plays a role for setting mechanical threshold even in this neuronal class (Figure 6F, Figure 7). Since many LTMRs are silent in the conditional knockout animals, we had expected C6-nociceptors to also become more prevalent amongst responding neurons. Surprisingly, however, this was not the case; their representation was dramatically reduced compared with the C13 neurons (Figure 7D) or even the itch related C11 and C12 classes (Figure S7A,C). Importantly, in wild type mice, C6 neurons have all the hallmarks of nociceptors: they express nociceptive markers (e.g. Scn10a and Calca), do not detect brush or air puff and have restricted receptive fields (Figure 7E-G). Moreover, in contrast to C3-neurons where Piezo2 knockout decreases a cell’s effective receptive field size to noxious stimulation, this was unchanged in both C6 and C13 class nociceptors (Figure 7G). Therefore, Piezo2 plays an unexpectedly important role in transducing rapid responses to painful mechanical stimuli in a large subset of the C6 Aδ-HTMRs.

Discussion

The sense of touch allows us to distinguish objects, warns of dangers and underlies our most intimate social interactions. The prevailing view stemming from studies carried out more than 100 years ago is that specialized receptor cells tuned to detect specific features function together to endow touch with its remarkable discriminatory repertoire (Norrsell et al., 1999). Subsequent work has revealed the beautiful anatomical specializations responsible for cellular level tuning (Willis, 2007) and more recently has linked this to selective molecular markers (Abraira and Ginty, 2013; Arcourt et al., 2017; Bai et al., 2015; Ghitani et al., 2017; Rutlin et al., 2014; Zimmerman et al., 2014). However, deciphering how the various classes of specialized neurons combine to provide a physical substrate encoding the rich sensory information of naturalistic stimuli remains challenging. In vivo functional imaging studies have begun to provide a view of how somatosensory stimuli may be represented by tens or even hundreds of neurons (Ghitani et al., 2017; Szczot et al., 2018; Yarmolinsky et al., 2016). But how do these rich and complex activity patterns relate to the anatomical and molecular features of the responding cells? Here we devised an approach to link the molecular and anatomical description of individual neurons to population responses. Using this platform, we exposed new information about the representation of touch at the periphery; we then identified a transcriptomic subgroup of myelinated neurons that function as selective detectors for air-puff and vibration; and finally, we uncovered mechanistic detail about mechanosensory detection across the full range of neuronal classes.

As a rule, we found that naturalistic stimuli activate many different classes of sensory neurons with most types of LTMR also responding to higher intensity stimulation. Since brush responsive neurons detect distal high force stimuli, this means that pinch and hair pull are represented both by specialist C6 and C13 nociceptors (with narrow receptive fields) and a larger population of C3 and C5 touch neurons. Notably however, we identified two functional classes of C4 neurons (air-puff and vibration) that were completely dependent on Piezo2 for mechanotransduction and only responded to gentle stimuli. Air-puff cells are particularly interesting as this type of stimulus was previously thought to be detected primarily by broadly tuned Aβ-RA-LTMRs (Bai et al., 2015) with properties of mixed responders. Moreover, our data revealed that there are at least 2 distinct transcriptomic types of air-puff cell with one of these marked by expression of calretinin (Calb2). These Calb2-Aβ-LTMRs constitute a third class of neurons with circumferential endings that wrap around hair follicles. Remarkably, the two other types of myelinated mechanosensors with this anatomical specialization do not respond to air-puff induced hair deflection but are sensitive to sustained stimuli and higher forces (Bai et al., 2015; Ghitani et al., 2017) demonstrating that anatomy alone does not account for tuning. So how is functional diversity achieved, and how can a neuron detect an air-puff but not respond to brushing or far higher forces? We suspect that the Calb2-Aβ-LTMRs may rapidly inactivate to sustained deflection of a hair and thus preferentially detect repetitive stimuli like vibration or the turbulent effects of air-puff. Indeed, very small and short-lived calcium transients were sometimes observed in response to other types of stimulation, in keeping with this hypothesis. Alternatively, it has been beautifully demonstrated that neurons forming circumferential endings almost always have expansive terminal fields (Wu et al., 2012), thus the distributed nature of air-puff and vibration might also play a role. In the future, targeted electrophysiological recordings will be needed to address these issues and may help explain how other differences arise between anatomically related classes of mechanosensors.

We take our sense of touch for granted despite its fundamental importance for many aspects of our lives including both pleasure and pain. Our identification of a group of individuals who lack PIEZO2 function has highlighted both expected and unexpected impact of losing this mechanosensor on human touch perception (Chesler et al., 2016; Szczot et al., 2018). Notably, despite these individuals’ inability to detect vibration, they could still perceive slow brushing on hairy skin but showed atypical fMRI responses (Chesler et al., 2016). Anecdotally, we noted that this type of brushing and other types of touch would often evoke unusual sensations that they described as prickling or itchy. Here, we showed that almost all somatosensory neurons are impacted by Piezo2 knockout and were able to disentangle how each transcriptomic class was differentially affected. For example, whereas A-type LTMRs were essentially silenced, cLTMRs remained mechanosensitive albeit with higher threshold and altered kinetics. Given that these different types of mechanosensor normally respond to brushing, their different reliance on Piezo2 provides a plausible explanation for how human PIEZO2 loss of function subjects still detect this type of relatively gentle stimulation as well as their atypical brush perception.

Recently other mechanosensitive transduction channels and receptors have been described that are expressed in sensory neurons and may detect painful stimuli (Beaulieu-Laroche et al., 2020; Murthy et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2018). Our results suggest that such mechanisms would be particularly important in C13-cHTMRs consistent with the recent report that one of these, Tacan, is essential for C13-nociception (Beaulieu-Laroche et al., 2020). Nonetheless, Piezo2 also appears important for mechanonociception with a large subset of C6 Aδ-HTMRs silenced by its knockout. It remains formally possible that some of these neurons respond to gentle stimulation either outside the area of skin that we tested or of a specialized nature (not brush, air-puff or vibration). However, both the gene-expression profile and the restricted receptive fields of these cells to hair pull (Figure 7G) make this unlikely. Therefore, it will be important to understand features of these cells, perhaps including splice forms of Piezo2 (Ghitani et al., 2017) or interacting proteins (Poole et al., 2014), that allow a very sensitive channel to provide C6 cells with the ability to specifically detect high-threshold stimuli. In the future, it will also be interesting to address whether people with PIEZO2-deficiency syndrome have selective rapid mechanical pain deficits e.g. to hair-pull, which in mice strongly activates a subset of C6-neurons (Ghitani et al., 2017).

In this study, we generated a rich dataset examining mechanical responses applied to just a small region of the cheek. Expanding the approach to other stimuli and specialized peripheral targets should help decipher an expanded logic for peripheral somatosensory coding. Interestingly, an analogous approach has just been used to study cellular level function-gene expression profiles in the zebrafish hypothalamus (Lovett-Barron et al., 2020). Thus, phenotyping ensembles of neurons followed by in situ hybridization in different brain regions is an attractive approach for matching function to cell identity and will provide a new dimension for understanding of how the nervous system represents and processes complex information.

STAR METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

LEAD CONTACT

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Alexander Chesler (alexander.chesler@ nih.gov).

MATERIALS AVAILABILITY

This study did not generate new unique materials.

DATA AND CODE AVAILABILITY

Calcium traces, gene expression annotation and cell classification data has been deposited at Mendeley (http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/hct95nx3t8.1). ImageJ macros and Python scripts for morphing/aligning images are available on Github (https://github.com/lars-von-buchholtz/warping).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

All experiments using animals strictly followed National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines and were approved by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) or the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) Animal Care and Use Committees and used male and female mice. Ai95(RCL-GCaMP6f)-D (#024105), Ai9(RCL-tdT) (#007909) and Calb2-Cre (#010774) mice were purchased from the Jackson laboratory. Tac1-tagRFP-2a-TVA and Piezo2lox/lox lines have been described previously (Szczot et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2018). For the main body of this study, Tac1-tagRFP-2A-TVA::Ai95(RCL-GCaMP6f)-D double transgenic mice were bred and GCaMP6f expression was induced by AAV-Cre injection. Piezo2 knockout effects were investigated in mice that additionally were homozygous for the Piezo2lox allele.

Calb2-expressing cells were investigated in Calb2-Cre::Ai95(RCL-GCaMP6f)-D double heterozygous transgenic mice (Madisen et al., 2015; Taniguchi et al., 2011) and their peripheral projections were visualized in Calb2-Cre::Ai9(RCL-tdT) double heterozygous transgenic mice (Madisen et al., 2010). C57BL/6N mice were purchased from Harlan.

METHOD DETAILS

Injection of AAV in mouse pups

Trigeminal ganglion neurons were targeted by intracerebroventricular, intrajugular and intraperitoneal injections (either singly or in combination) of AAV9-Cre in postnatal day 1–3 mouse pups. Mouse pups were briefly anesthetized by placing the animals in a plastic weighing tray on ice. An infusion syringe pump (KDS230, KD Scientific) setup with a 0.3 ml insulin syringe (BD) or a Hamilton syringe (Hamilton Robotics, Reno, USA) was used to inject 1–3μl of AAV9-CAG-Cre virus ( 2 × 1012 to 2 × 1013 virions/ml, catalog # CV17187-AV9, Vigene, Rockville, USA).

In vivo epifluorescence calcium imaging

The surgical preparation to gain optical access to the trigeminal ganglion was performed as previously described (Ghitani et al, 2017). Calcium imaging used a custom-built epifluorescence Cerna microscope (Thorlabs) with a 4x, 0.16 NA objective (Olympus) using a 480nm fluorescence LED to image GCaMP6f, and a 561nm LED to image tagRFP (Lambda, Sutter Instruments). Excitation and emission light passed through a standard green fluorescent protein (GFP) filter cube for GCaMP6f, and an mCherry filter cube for tagRFP (Olympus). Images were acquired at 5 Hz using a PCO Panda 4.2bi scientific CMOS camera, using the provided PCO acquisition software. For each trigeminal ganglion, Tac1-tag-RFP expressing neurons were imaged in the red channel, then GCaMP6f transients were recorded in the green channel, without moving the specimen. A series of air-puffs of increasing durations (0.2, 1, 3 and 5s) was delivered to the face using a Picospritzer III (Parker). This device delivered pressurized air at 25psi through a 1mm inner diameter Teflon tubing that ejected air at a distance of 3 cm from the face to achieve visible hair deflection. Vibration was delivered using a custom-built latex-Pasteur-pipette bulb tipped applicator that was applied by just touching the hairs over the center of the cheek. Sinusoidal waveforms at 50, 75, 100, 125, and 150 Hz, lasting 3 seconds for each, were generated using a Digidata 1550 (Molecular Devices) to control a solenoid (SolidDrive SD1sm, Induction Dynamics) and were amplified by a 70W subwoofer plate amplifier (SA70, Dayton Audio). Manual gentle stroking of a large area of the cheek was performed repeatedly using a cotton tipped applicator with the grain (i.e. in a rostral to caudal direction). Hair-pull and pinch were performed manually using forceps at multiple locations covering the whole cheek between the eye and whisker pad in each stimulation epoch. The Digidata 1550 was also used to control image acquisition, timing of air-puff pulses and vibration. GCaMP6f fluorescence was recorded during stimulation episodes (40s at 5Hz for each stimulus) and concatenated to a single image stack in ImageJ. Individual frames were registered to the first frame using a custom ImageJ macro based on the ‘Linear Stack Alignment With SIFT’ plugin to correct for motion artifacts.

Spatial activity maps

To generate spatial maps of activity, the standard deviation for each pixel over a stimulation episode was calculated in FIJI/ImageJ. Silent cells show a very low standard deviation from their mean fluorescence whereas stimulus-induced calcium transients result in high standard deviations. To compound activity across multiple stimuli, a maximum intensity projection over the individual episodes was used.

Regions of interest (ROIs) were manually extracted from these images using the ‘Cell Magic Wand’ plugin in ImageJ. Overlapping cell ROIs that were contaminated by each other’s responses as well as out of focus or spontaneously active cells were excluded from the analysis. These choices were made while blind to transcriptomic information.

Functional category specific maps were generated for air-puff cells, vibration cells, brush cells, mixed responders and HT-cells. To do this, the standard deviation images for the preferred stimulus of a category were multiplied with binary masks that outline the cell ROIs belonging to that category (see below). These maps are specific for a functional category of cells and provide an estimate of the response magnitude as well as the shape and location of a cell.

Analysis of fluorescence dynamics

For each cell ROI, relative change in GCaMP6f fluorescence was calculated as percent ΔF/F and potential contaminant signal from the underlying out-of-focus tissue and neighboring cells was removed by subtracting the fluorescence of a donut-shaped area surrounding each cell using a custom Matlab script (Szczot et al. 2018). Responses to each stimulus were recorded as individual 40 second episodes and concatenated for display as traces or activity heatmaps. For the heatmaps in figures 2, 4, 6 and 7, GCaMP6f fluorescence changes were normalized to the median of the pinch response peaks in the respective mouse to standardize data between animals.

Functional categorization of cells

Each cell’s background fluorescence noise was calculated as the standard deviation of the bottom 50% of all data points. A transient rise in fluorescence was considered significant if its peak exceeded 10 times this value. A cell was assigned a functional category according to a set of numerical rules to allow automation and eliminate observer bias. Air-puff cells had significant air-puff responses and ratios of air-puff response to brush response exceeding 2. Vibration cells had significant vibration responses and a ratio of vibration responses to all other responses greater than 3. Brush cells had a significant brush response and a ratio of brush to air-puff response greater than 2 and a ratio of pinch and hair-pull responses to brush greater than 3. Mixed responders had significant air-puff and brush responses with ratio between 0.5 and 2 and ratios of pinch and hair-pull responses to brush responses larger than 3. HT-cells were defined as cells that had a significant response to pinch and/or hair-pull and had a ratio of high threshold to low threshold peak responses of at least 3.

In order to compare the effective receptive field sizes of brush and HT neurons, a separate set of 4 ganglia was stimulated with 4 pinches in a straight line across the cheek at ~1mm intervals and gentle brushing of the cheek. A total of 580 neurons were identified in these experiments. They were functionally classified into brush / mixed responder and HT cells as described above and their calcium transients were normalized to their maximal response to better visualize the effective receptive field of these neurons.

Whole-mount ISH of trigeminal ganglia

Immediately after in vivo calcium imaging, trigeminal ganglia were immersed in ice-cold 4% PFA (Electron Microscopy Sciences) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 90 min. They were then washed 3 times in PBS and attached (ventral surface, super-glue) to plastic strips (10 × 2mm) to facilitate handling and then were rinsed again using PBS. ISH was performed using hybridization chain reaction (HCR) version 3 (Choi et al., 2018): pre-hybridization, 30 min, 35 °C in HCR hybridization solution (Molecular Instruments); hybridization, 48 – 72 h, 35 °C using combinations of five of the following probes: Trpm8 (Genbank NM_134252, full-length), Cd34 (NM_001111059, full-length), S100b (NM_009115, full-length), Fxyd2 (NM_007503, full-length), Scn10a (NM_001205321, CDS), Calca (NM_007587, full-length), Trpv1 (NM_001001445, full-length), Etv1 (NM_007960, full-length), Tmem233 (NM_001101546, full-length), Mrgprd (NM_203490, full-length), Calb2 (NM_007586, CDS), tagRFP-TVA and EGFP (which detects GCaMP6f-expression). Ganglia were then washed 2 times, 15 min in wash buffer (Molecular Instruments) at 37 °C followed by 4 times, 30 min in 2xSSC / 30% formamide, 37 °C. Ganglia were rinsed twice in 2xSSC and incubated overnight at room temperature with amplifier hairpins for adapters B1 - B5 conjugated to Alexa488, Alexa514, Alexa561, Alexa594 and Alexa647 that were prepared as described by the manufacturer. Ganglia were then washed 4 times, 20 min in 5xSSC/0.1%Tween-20 and embedded in 2% low-melt agarose in the top half of a CoverWell™ imaging chamber (Grace Biolabs). The rest of the chamber was filled with Imaging Buffer (3 U / ml pyranose oxidase, 0.8 % D-glucose, 2 x SSC, 10 mM Tris HCl pH 7.4). After imaging, ganglia were rinsed in 2xSSC and DNA probes and amplifiers were removed by incubation in 250 U / ml RNase-free DNase (Roche Diagnostics), 60 min at room temperature. Ganglia were washed 6 times, 5 min in 2xSSC and pre-hybridized for the next round of hybridization with the next 5 probes. For some ganglia, this procedure was repeated a third time to increase the number of aligned probes but deterioration both of signal to noise ratio and ganglion integrity meant this additional round rarely added useful information.

ISH of tissue sections

Trigeminal ganglia dissected from 2–4 months old C57BL/6 and Calb2-Cre::Ai9 (RCL-tdT) mice were embedded in OCT medium and frozen at −80 °C. 20 μm sections were prepared for RNAscope (ACD Inc.) ISH or for HCR probing as described previously (Nguyen et al., 2017; von Buchholtz et al., 2020). RNAscope probes were to Calb2 (313641-C3), Cre (474001), S100b (431731-C2) and tdT (317041); HCR probes to mouse Piezo2 (Genbank NM_001039485, full-length), Mrgprd, S100b and Calca.

Confocal imaging and signal unmixing

HCR ISH imaging was carried out using a Zeiss LSM 880 confocal microscope with spectral detector using a 10x/0.45NA air objective. Alexa647 was stimulated with a 633 laser and emission was collected from 644–752 nm. Alexa546 and Alexa594 were stimulated with 561 and 594 lasers respectively and wavelength scans with 9nm windows were collected to allow unmixing signals from different fluorophores. Similarly, Alexa488 and Alexa514 were stimulated with a 488 nm laser and 9nm wavelength scans allowed unmixing of these fluorophores. For detection of single transcripts of weakly expressed genes, imaging was performed with a 40x/1.1NA long working distance water immersion objective (Zeiss LD C-Apochromat). Spectral unmixing was performed using Zeiss ZEN software. Dorsal views of whole-mount ganglia were imaged as Z stacks with 10 μm intervals to capture the convex surface of the ganglion. Since the ganglion is opaque and our confocal imaging only penetrates ~20–30 μm into the tissue the convex surface of the ganglion captured in the Z stack can be collapsed by maximum intensity projection into a 2D dorsal view comparable to the in vivo image. This almost exclusively is a single cell layer both in functional imaging experiments and for ISH images. Imaging of sections was as previously described (Nguyen et al., 2017; von Buchholtz et al., 2020).

Aligning whole mount ISH images to in vivo recordings

As a first step, multi-channel 2D ISH images were crudely aligned to in vivo fluorescence by scaled rotation using the TurboReg plugin and a custom-written macro in ImageJ/FIJI. tagRFP mRNA positive guidepost cells were then manually matched to their in vivo red fluorescent counterparts using a custom-written ImageJ macro that identified coordinate pairs for each guidepost. The ISH image was then morphed to match its in vivo counterpart using these coordinates with a custom Python script that builds on the OpenCV library and was adapted from face morphing software (https://www.learnopencv.com/face-morph-using-opencv-cpp-python/).

In brief, Delaunay triangulation (Delaunay, 1934) was used to connect the guidepost points to obtain the most even set of triangles in the source image. The corresponding triangles for the target (in vivo) guideposts were calculated; then each source triangle was transformed into its target shape by affine transformation. This approach allows each triangular patch to be transformed independently from the rest of the image. As a result, the whole area of the ISH image spanned by the guidepost cells is morphed smoothly and continuously to fit the matching in vivo pair (Figure 1, see also Figure S1 for illustration). Similarly, multiple rounds of ISH were aligned to each other using a shared probe (or probes labeling similar sets of cells) in both rounds to provide guideposts for morphing.

Evaluation of alignment accuracy

In order to evaluate the alignment accuracy between subsequent rounds of ISH, 3 trigeminal ganglia were stained with probes for Trpm8, Mrgprd, S100b and Tac1 which cover >90% of trigeminal ganglion neurons. In a second round, ganglia were re-stained with the same set of probes. ISH images were aligned using Trpm8 cells as guideposts and correct recovery of Mrgprd cells (which are not overlapping with Trpm8 cells) was assessed in a blinded fashion: 3000 cell outlines and their Mrgprd expression were determined by an annotator based on first round ISH data and Mrgprd status of each cell outline in the second round was determined by a second annotator based solely on ISH data from the second round. Similarly, accuracy of alignment between in vivo functional imaging and ISH images was assessed by comparing spatial activity maps to their corresponding GCaMP ISH in two representative ganglia. A first annotator outlined responsive cells and discarded cells that were not suitable for functional analysis (spatially overlapping, out-of-focus and spontaneously active cells). The same annotator generated an equal number of decoy ROIs interspersed in the area of alignment. After alignment using tagRFP guidepost cells, a second annotator who was blind to the in vivo imaging then determined the GCamp status of functional and decoy ROIs based solely on GCaMP ISH data. Relative cell displacement was measured in ImageJ.

Analysis of gene expression and transcriptomic classification

Cell ROIs based on the functional imaging (i.e. responding cells) were manually analyzed for the cellular expression (positive or negative) of every gene with high-quality (diagnostic) ISH data. ROIs that were located outside the alignment area or could not be matched unambiguously to the ISH data were discarded from the analysis. At the time of analysis, the annotator was blind to the response profile of the ROI cells. Binary expression patterns were decoded into transcriptomic cell classes by the set of rules explained in Figure S3; rare cells (<2%) with conflicting expression patterns (unclassified or nd) were excluded from subsequent analysis.

Skin histology

Skin from the back, cheek and whisker pad of Calb2-Cre::Ai9(RCL-tdT)-D mice with appropriate expression of tdT-fluorescence in a small subset of large diameter trigeminal neurons was fixed in 4% PFA in PBS for 5 days at 4°C. Tissue samples were washed in PBS and embedded in OCT medium (Tissue Tek) for cryosectioning. Thick sections (60–80 μm) were collected, washed in PBS and mounted in Vectashield with DAPI (Vector Labs) for imaging. Z stack images were acquired using a 40x oil objective on a laser scanning confocal system (Olympus Fluoview FV1000) and collapsed by maximum intensity projection using FIJI/ImageJ software.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The number of control (Tac1-tagRFP-2A-TVA::Ai95(RCL-GCaMP6f)-D,Piezo2+/+) and Piezo2-KO (Tac1-tagRFP-2A-TVA, Ai95(RCL-GCaMP6f)-D, Piezo2lox/lox) animals that were tested for each transcriptomic class and functional category is shown in the supplemental Data Table 1.

In order to calculate receptive field indices (RFI), individual response peaks to multiple pinches or hair pulls distributed across the cheek were determined using the find_peaks function of the scipy.signal package and normalized to the neuron’s maximal response. Stimulation timepoints were identified by pooling response peaks from all neurons in an experiment and finding maxima in the histogram of response timepoints. Peaks that did not occur within a 2.4 s window around a simulation-time point were excluded from the analysis. The RFI was calculated as the sum of all (normalized) response peaks divided by the number of stimulations. A wide receptive field will result in robust responses from many stimulations across the cheek and therefore a high RFI whereas a narrow field neuron will only respond to one or a few stimulations. In experiments using 4 pinches in a straight line (Figure S2), a stringent cutoff for wide field neurons was set at an RFI of 0.35.

Percentages of transcriptomic cell classes contributing to a functional cell category were calculated by dividing the number of responding cells positive for a given class by the number of responding cells that were tested with ISH probes for that class. Since not all classes were tested in any individual animal, the summed percentages do not exactly add up to 100%; (98.59% for control and 98.61% for Piezo2-KO). To display proportions in stacked bar graphs (Figures 6G, 7D), percentages were further normalized to total 100% in these graphs.

Relative abundance of functional cell categories in control animals and after Piezo2 knockout (Figure S7A) was calculated as the number of cells belonging to a specific category divided by the total number of responding cells.

The log ratio of high threshold to low threshold responses per cell (Figure 6F) was calculated by dividing the response peak to hair-pull and pinch by the response peak to air-puff and brush and taking the natural logarithm.

Mean lifetime of GCaMP transients was calculated by fitting logarithmic decay from maximum to 10% this value using linear regression. The mean lifetime τ is the negative inverse of the coefficient. Values in Figure S5D are the means ± s.e.m. of τ values of the individual cells.

Data were plotted as either bar graphs or as box and whisker plots with the medians and quartiles indicated by the box and the whiskers extending to the most extreme data point within 1.5 times the interquartile range. Individual data points (animals or cells) are superimposed as dots on these graphs. Since our data compared different sample sizes with potentially different variances, we chose a two-sided Welch’s unequal variances t-test to assess the significance of differences. Holm–Šidák correction was applied to all statistical tests to adjust for multiple comparisons.

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| AAV9-CAG-Cre | Vigene | CV17187-AV9 |

| Biological Samples | ||

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| Hybridization Chain Reaction (HCR) version 3 kit | Molecular Instruments | n/a |

| RNAscope Fluorescent Multiplex | ACD | n/a |

| Deposited Data | ||

| Calcium traces, ISH annotation and cell classifications | This paper | http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/hct95nx3t8.1 |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Mouse: B6;129S-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm95.1(CAG-GCaMP6f)Hze/J (Ai95) | The Jackson Laboratory | Stock No: 024105 |

| Mouse: B6.Cg-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm9(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J (Ai9) | The Jackson Laboratory | Stock No: 007909 |

| Mouse: B6(Cg)-Calb2tm1(cre)Zjh/J | The Jackson Laboratory | Stock No: 010774 |

| Mouse: Tac1-tagRFP-2a-TVA | Wu et al., 2018 | n/a |

| Mouse: Piezo2lox/lox | Szczot et al., 2018 | n/a |

| Mouse: C57BL/6N | Harlan | n/a |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Python 3.6 | www.python.org | |

| OpenCV 3 | www.opencv.org | |

| FIJI/ImageJ | Schindelin et al., 2012 | https://imagej.net/Fiji |

| ZEN | Zeiss | https://www.zeiss.com/microscopy/us/products/microscope-software.html |

| Custom ImageJ macros and Python scripts | This paper |

https://github.com/lars-von-buchholtz/warping DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.4088771 |

| Other | ||

Naturalistic mechanical stimuli activate large overlapping ensembles of neurons

In situ hybridization after functional imaging maps responses to cell class

Tuning properties of the classes reveal a transcriptomic basis for specialization

Mechanotransduction via Piezo2 contributes to almost all aspects of touch

von Buchholtz et al. evaluate the representation of naturalistic mechanosensory stimuli by combining functional imaging with multigene in situ hybridization to determine gene expression profiles of large ensembles of trigeminal neurons. Their results expose a transcriptomic logic for touch discrimination and cell-class specific roles for the Piezo2 ion channel.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Intramural program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (N.J.P.R.) and National Center for Integrative and Complementary Health (A.T.C.) and included funding from Department of Defense in the Center for Neuroscience and Regenerative Medicine (A.T.C.); microscopy used the NINDS Light Imaging Facility. We thank Drs. M. Nguyen, A. Barik and M. Szczot for their help and input; we are also indebted to other members of our groups and Drs. M. Hoon, M. Krashes, C. Le Pichon and C. Bushnell for their encouragement and advice.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abrahamsen B, Zhao J, Asante CO, Cendan CM, Marsh S, Martinez-Barbera JP, Nassar MA, Dickenson AH, and Wood JN (2008). The cell and molecular basis of mechanical, cold, and inflammatory pain. Science (New York, NY) 321, 702–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraira VE, and Ginty DD (2013). The sensory neurons of touch. Neuron 79, 618–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcourt A, Gorham L, Dhandapani R, Prato V, Taberner FJ, Wende H, Gangadharan V, Birchmeier C, Heppenstall PA, and Lechner SG (2017). Touch Receptor-Derived Sensory Information Alleviates Acute Pain Signaling and Fine-Tunes Nociceptive Reflex Coordination. Neuron 93, 179–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai L, Lehnert BP, Liu J, Neubarth NL, Dickendesher TL, Nwe PH, Cassidy C, Woodbury CJ, and Ginty DD (2015). Genetic Identification of an Expansive Mechanoreceptor Sensitive to Skin Stroking. Cell 163, 1783–1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardoni R, Tawfik VL, Wang D, François A, Solorzano C, Shuster SA, Choudhury P, Betelli C., Cassidy C., Smith K., de Nooij JC., Mennicke F., O’Donnell D., Kieffer BL., Woodbury CJ., Basbaum AI., MacDermott AB., and Scherrer G. (2014). Delta opioid receptors presynaptically regulate cutaneous mechanosensory neuron input to the spinal cord dorsal horn. Neuron 81, 1312–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basbaum AI, Bautista DM, Scherrer G, and Julius D (2009). Cellular and molecular mechanisms of pain. Cell 139, 267–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bautista DM, Siemens J, Glazer JM, Tsuruda PR, Basbaum AI, Stucky CL, Jordt SE, and Julius D (2007). The menthol receptor TRPM8 is the principal detector of environmental cold. Nature 448, 204–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu-Laroche L, Christin M, Donoghue A, Agosti F, Yousefpour N, Petitjean H, Davidova A, Stanton C, Khan U, Dietz C, et al. (2020). TACAN Is an Ion Channel Involved in Sensing Mechanical Pain. Cell 180, 956–967.e917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadwell CR, Palasantza A, Jiang X, Berens P, Deng Q, Yilmaz M, Reimer J, Shen S, Bethge M, Tolias KF, et al. (2016). Electrophysiological, transcriptomic and morphologic profiling of single neurons using Patch-seq. Nature Biotechnology 34, 199–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang RB, Strochlic DE, Williams EK, Umans BD, and Liberles SD (2015). Vagal Sensory Neuron Subtypes that Differentially Control Breathing. Cell 161, 622–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesler AT, Szczot M, Bharucha-Goebel D, Ceko M, Donkervoort S, Laubacher C, Hayes LH, Alter K, Zampieri C, Stanley C, Innes AM, Mah JK, Grosmann CM, Bradley N, Nguyen D, Foley AR, Le Pichon CE, and Bonnemann CG (2016). The Role of PIEZO2 in Human Mechanosensation. N Engl J Med 375, 1355–1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi HMT., Schwarzkopf M., Fornace ME., Acharya A., Artavanis G., Stegmaier J., Cunha A., and Pierce NA. (2018). Third-generation in situ hybridization chain reaction: multiplexed, quantitative, sensitive, versatile, robust. Development (Cambridge, England) 145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coste B, Mathur J, Schmidt M, Earley TJ, Ranade S, Petrus MJ, Dubin AE, and Patapoutian A (2010). Piezo1 and Piezo2 Are Essential Components of Distinct Mechanically Activated Cation Channels. Science (New York, NY) 330, 55–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaunay B (1934). Sur la sphere vide. Bull Acad Sci USSR(VII), Classe Sci Mat Nat, 793–800.

- Dhaka A, Murray AN, Mathur J, Earley TJ, Petrus MJ, and Patapoutian A (2007). TRPM8 is required for cold sensation in mice. Neuron 54, 371–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatto G, Smith KM, Ross SE, and Goulding M (2019). Neuronal diversity in the somatosensory system: bridging the gap between cell type and function. Curr Opin Neurobiol 56, 167–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]