This cross-sectional study examines data from 13 hospitals in 2 donor service areas to estimate the number of potential donor patients and identify ways to improve the organ procurement system.

Key Points

Question

Where are the opportunities in the US transplant system to increase the number of available organs?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study of hospitals served by 2 organ procurement organizations (OPOs), we found wide variation in the performance of OPOs, especially at individual hospitals.

Meaning

Focusing on OPO performance at individual hospitals could eliminate the shortage of extrarenal organs and increase the kidney supply.

Abstract

Importance

Availability of organs inadequately addresses the need of patients waiting for a transplant.

Objective

To estimate the true number of donor patients in the United States and identify inefficiencies in the donation process as a way to guide system improvement.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A retrospective cross-sectional analysis was performed of organ donation across 13 different hospitals in 2 donor service areas covered by 2 organ procurement organizations (OPOs) in 2017 and 2018 to compare donor potential to actual donors. More than 2000 complete medical records for decedents were reviewed as a sample of nearly 9000 deaths. Data were analyzed from January 1, 2017, to December 31, 2018.

Exposure

Deaths of causes consistent with donation according to medical record review, ventilated patient referrals, center acceptance practices, and actual deceased donors.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Potential donors by medical record review vs actual donors and OPO performance at specific hospitals.

Results

Compared with 242 actual donors, 931 potential donors were identified at these hospitals. This suggests a deceased donor potential of 3.85 times (95% CI, 4.23-5.32) the actual number of donors recovered. There was a surprisingly wide variability in conversion of potential donor patients into actual donors among the hospitals studied, from 0% to 51.0%. One OPO recovered 18.8% of the potential donors, whereas the second recovered 48.2%. The performance of the OPOs was moderately related to referrals of ventilated patients and not related to center acceptance practices.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cross-sectional study of hospitals served by 2 OPOs, wide variation was found in the performance of the OPOs, especially at individual hospitals. Addressing this opportunity could greatly increase the organ supply, affirming the importance of recent efforts from the federal government to increase OPO accountability and transparency.

Introduction

The number of organ donors in the United States has been increasing in the last few years because of opioid-related deaths, the use of organs from donors who are hepatitis C–positive, and improved use of organs after circulatory determination of death. However, more than 11 000 wait-listed patients died or became too sick to undergo transplantation in 2021.1,2,3,4,5 The more than 100 000 patients wait-listed for a kidney transplant will wait a median time longer than 4 years. Dialysis is highly morbid and carries significant mortality.6 Increasing the donor supply is therefore critical to help bridge the organ demand-supply gap.

Published studies suggest the potential number of deceased donors in the United States is substantially higher than the actual number of donors. An early study using the gold standard of individual medical record review published in 2002 included data from 36 organ procurement organizations (OPOs) and estimated donor potential of 10 500 to 13 800 individuals compared with an actual number of donors of less than 6000.7 In 2012, a deceased donor potential study performed by a United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) task force using population-based data suggested a donor potential of nearly 30 000 individuals.8 A separate study performed in 2016 using administrative databases identified a gap of nearly 31 000 donors in the United States.9 Taken together, these studies over 20 years paint a consistent picture that the system is missing thousands of donors every year. Compare this to the number of patients who died or were delisted in 2021 while waiting for a liver, which was 2346 patients; 525 patients were waiting for a heart, and 280 patients were waiting for a lung. It becomes clear that even a modest increase in donors could solve the current nonrenal organ shortage and decrease the time waiting to receive a deceased-donor kidney.

There is little understanding of the root causes of variation in procurement rates by OPOs, in part because relevant data are difficult to obtain. For example, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) requires that individual death record review be performed by each OPO, but these data are not publicly reported.10 This lack of data has led to various theories on why the system is missing so many donors. Some argue that blame lies with the failure of hospitals to refer ventilated patients to OPOs or with center acceptance practices.11,12 It is likely that differences in OPO performance are partly responsible, which varies by 400% according to objective metrics.13 To remediate significant variation in performance, the CMS recently approved a final rule that would change the way OPOs are evaluated, using population-level data about cause of death from the National Center for Health Statistics as the denominator to measure performance.10,14 The new metric considers cause, age, and location-consistent (CALC) deaths and is an objective, independently reported measure.

Understanding the true donor potential in the United States and areas of underperformance is critical to guide system improvement efforts. Our previous work demonstrated variation in donor-hospital performance based on CMS ranking.15 We sought to extend this analysis by performing a retrospective cross-sectional study reviewing actual complete records for deceased patients across 13 hospitals, served by 2 OPOs, to determine donor patient potential and examine variability at the OPO and hospital level. Taken together, these data provide contemporary estimates of donor patient potential and suggest areas for targeted intervention.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cross-sectional analysis of organ donation across 13 different hospitals in 2 donor service areas covered by 2 OPOs. Outcome measures included potential donors by medical record review vs actual donors, correlation of ventilated patient referrals to donation performance by hospital, comparison of OPO performance, and proportion of center acceptances to OPO performance. The determination of the Vanderbilt University Medical Center institutional review board was that our study did not qualify as human subjects research per 45 CFR §46.102 because we were not conducting research on living individuals.16 A similar determination was achieved at all study sites.

Choice of Donor Service Areas and Hospitals

We chose 2 donor service areas that did not differ based on previous CMS ratio of observed-to-expected donor metrics but that did differ based on the new CMS CALC metric. We chose hospitals for which we were able to obtain medical records, including transplant and nontransplant hospitals in each donor service area. We reviewed data from 2017 and 2018 to eliminate any possible effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Record Access

We obtained access to medical records for all 13 hospitals using the local electronic medical record with remote access when possible. This access consisted of the entire hospital medical record containing all notes, including discharge summaries, laboratory values, and study reports. Access included all deaths in 2017 and 2018. Each hospital was assigned a letter and the OPOs a number (OPO-1 and OPO-2) in this article to maintain anonymity.

Medical Record Review

We determined the number of deaths per hospital for patients aged 5 to 75 years. To simplify data collection, we choose age 5 years as a lower limit because less than 0.3% of donors are younger than 5 years, and many of the deaths in our cohort were fetal demise and therefore did not represent potential donors. For each center, we then computed the number of records needed to review to yield a confidence interval half-width of 4%. Based on our experience, we hypothesized that 10% of all deaths would be potential donors. We examined the number of records required to estimate the actual number of potential donors to within 4% based on sample-size analysis with these initial assumptions. The maximum required sample size was 600. The total number of records reviewed was 2008. This set of 2008 death records was then used, through appropriate weighting, to make estimates on 8925 total individual inpatient deaths (reviewed plus nonreviewed). This provided the number of potential donors with a 95% CI of a width of 0.013 (maximum possible, 0.021).

Medical records were chosen randomly and divided among the investigators. Each record was reviewed once by a member of the group. To minimize bias, all deaths classified as a potential donor were then reviewed by a senior transplant surgeon experienced in offer evaluation (S.J.K. or M.B.S.). We used strict criteria to define an inpatient death as a potential donor and to avoid overcounting potential donors.9 We excluded an inpatient death as a potential donor if the patient (1) had an in-hospital cardiac arrest and did not regain spontaneous circulation; (2) died in the emergency department; (3) did not die within 1 hour of a terminal extubation; (4) had any active, nontreated cancer; (5) had a diagnosis of both chronic renal disease and chronic liver disease; (6) had a terminal serum creatinine concentration greater than 2.0 mg/dL and terminal aspartate aminotransferase or amino alanine transferase value greater than 2000 IU/mL; (7) was a potential donor after cardiac death but was older than 70 years of age; or (8) experienced severe sepsis. These criteria were based on our clinical experience suggesting the logistics would not make donation possible (eg, in-hospital cardiac arrest without return of spontaneous circulation), medical criteria that would exclude a patient from being considered a suitable donor (eg, multiorgan failure), and published literature.5

Program Data

National data were obtained from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS). OPO-specific data were obtained from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) program-specific reports. Data on ventilated patient referrals were obtained directly from the OPOs. UNOS and the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients maintain publicly available data sets on their websites and include downloadable .pdf files. Data files from OPO-specific reports were downloaded and used as described. Data were analyzed from January 1, 2017, to December 31, 2018.

Statistical Analysis

Quoted observed-to-expected values refer to observed to expected ratios as determined by the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients using their methodology.17 Sample size was determined using standard methodology.18 A Spearman correlation coefficient was calculated to measure the strength of correlation between 2 numeric variables. To compare the performance of the 2 OPOs, we used the actual number of donors as the outcomes and log of potential donors as an offset and then fitted a Poisson regression model. The nontransplant centers in OPO-1 served as the reference, to which each of the other 3 combinations of OPO and transplant vs nontransplant status were compared.

Results

Donor Potential in Our Cohort

The 13 hospitals in our sample are listed in Table 1 along with the type of hospital and numbers of deaths, records reviewed, ventilated patient referrals, record-based potential donors, and actual donors.

Table 1. Hospital Characteristics and Donation Metrics.

| Hospital and OPO | Deaths, No. | Records reviewed, No. | Ventilated patient referrals, No. | Potential donors based on record review, No. | Actual deceased donors, No. | Ratio of actual to potential donors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPO-1 | ||||||

| A | 245 | 148 | 58 | 19.6 | 0 | 0.00 |

| B | 61 | 54 | 0 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.00 |

| C | 726 | 251 | 364 | 63.4 | 7 | 0.11 |

| D | 1080 | 281 | 339 | 53.2 | 7 | 0.13 |

| E | 279 | 162 | 3 | 10.3 | 1 | 0.10 |

| F | 391 | 194 | 199 | 48.1 | 2 | 0.04 |

| G | 75 | 61 | 29 | 4.8 | 1 | 0.21 |

| Ha | 3448 | 346 | See below | 388.6 | 69 | 0.18 |

| I | 328 | 178 | 1979 (H + I) | 20.3 | 0 | 0.00 |

| OPO-2 | ||||||

| Ja | 2079 | 191 | 1248 | 298.3 | 152 | 0.51 |

| K | 206 | 135 | 9 | 21.4 | 3 | 0.15 |

| L | 2 | 2 | 17 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| M | 5 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Total | 8925 | 2008 | 4246 | 931.2 | 242 | 0.26 |

Abbreviation: OPO, organ procurement organization.

Hospital type was transplant; the 11 other hospitals were nontransplant.

Our prestudy assumption to determine sample size, that approximately 10% of deaths would be possible donors, was confirmed after all the records were reviewed (actual 10.4%). The number of actual donors was obtained from public reports and is not an estimate.

For individual hospitals, the ratio of actual donors to record review–identified possible donors ranged from 0.0 to 0.51. In other words, the number of donors recovered across different hospitals ranged from 0% to 51% of record-identified possible donors. For example, hospital I had 328 deaths, 20.3 predicted possible donor patients, but not a single donor. For the entire cohort, 26% of possible donors were actually used for transplant. The probability of potential donor recovery was significantly greater among transplant vs nontransplant hospitals, with an odds ratio of 5 (95% CI, 3.09-8.45; P < .001). For the entire cohort, we identified 689 additional possible donors in addition to the 242 actual donors (for a total of 931).

Association of Ventilated Patient Referrals and Donation Performance by Hospital

To determine whether ventilated patient referrals were a critical determinant of how well an OPO performed in a particular hospital with respect to successful donation, we compared the ratio of ventilated patient referrals/deaths to the proportion of actual/potential donors. In other words, did a higher proportion of referred deaths translate into better OPO performance at that hospital? The Spearman correlation coefficient was 0.32, suggesting a moderate positive correlation, indicating that a higher ratio of ventilated patient referrals to deaths is associated with better donation performance.

Comparison of the 2 OPOs

The historical ratio of observed to expected donors for the 2 OPOs showed the OPOs were equivalent in performance based on OPO-specific reports obtained from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients website (Table 2).17 To test whether the data confirmed this equivalent performance, we analyzed our data from record reviews showing that OPO-1 recovered 14% of possible donors whereas OPO-2 recovered 48% of possible donors.

Table 2. Publicly Reported Donation Rates by Organ and Organ Procurement Organization.

| Heart | Kidney | Liver | Lung | Standard donation rate (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPO-1 ratio of observed to expected | |||||

| 2017 | 1.02 | 0.95 | 1.02 | 0.96 | 1.01 (0.91-1.10) |

| 2018 | 0.98 | 1 | 0.95 | 1.06 | 1.07 (0.98-1.13) |

| OPO-2 actual rate | |||||

| 2017 | 1.13 | 0.99 | 1.05 | 1.2 | 1.02 (0.96-1.09) |

| 2018 | 1.17 | 1.01 | 1 | 1.1 | 0.98 (0.91-1.04) |

The multivariable Poisson regression model indicated that OPO-2 had nearly 3-fold higher actual donors (of estimated potential donors) relative to OPO-1, with a rate ratio (RR) of 2.77 (95% CI, 2.56-2.99; P < .001), adjusted for type of hospital. This suggests that historical performance metrics failed to find an actual difference in performance. Using the CALC criteria resulted in a difference between the OPOs.19 The OPO performance in transplant hospitals was better than in nontransplant hospitals (RR = 2.48; 95% CI, 1.58-3.88; P < .001).

Association of Center Acceptance Practices With OPO Metrics

Examination of the center acceptance practices revealed similar rates of nontransplanted organs across all organs between the 2 OPOs, with each being within 8% of the other for all organs (Table 3). This finding suggests that acceptance patterns are not responsible for the differences in OPO performance.18

Table 3. Proportion of Procured Organs Accepted for Transplant by Organ and Organ Procurement Organization.

| OPO | Kidney | Liver | Heart | Lung |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.78 | 0.91 | 1.00 | 0.94 |

| 2 | 0.72 | 0.92 | 0.99 | 0.98 |

Discussion

Our study found a statistically significant, large absolute variation in OPO performance at individual hospitals in 2 OPOs, ranging from 0% to 51%. This potentially explains the 2- to 4-fold gap between actual donors and published donor potential and is consistent with recent assessments of variation in OPO performance.7,8,9,20 Given that a modest increase in liver, heart, and lung procurements would equal the number of patients who died or were delisted for transplant, directly addressing this variability could virtually eliminate the shortage of nonrenal organs and make a significant impact on the renal waiting list.

By starting with medical record reviews, we provide the gold standard for determining the number of possible donors. The actual donation numbers we report are publicly reported and accurate. In contrast, the steps that occur between death and donation are opaque.

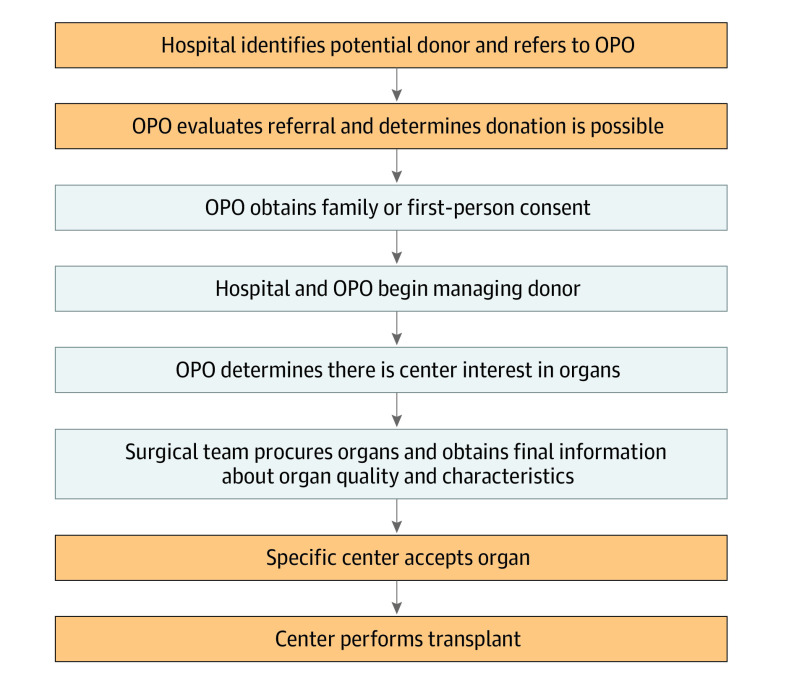

To realize a donation, a number of events must occur: (1) a patient must die in a hospital of causes compatible with donation, (2) the donor patient must be referred to the OPO, (3) the OPO must appropriately care for the donor patient and facilitate donation, and (4) a center must accept the donation (Figure). Our study helps determine the outcomes at each level.

Figure. Events Required for Successful Donation.

OPO indicates organ procurement organization.

Analyzing the US donation system by these steps provides important information. With respect to step 1, we found many patients who die of causes consistent with donation; only 26% of potential donors actually become donors. This result is highly consistent with other studies over 20 years.7,8,9 Regarding step 2, we next found that ventilated patient referrals to the OPO are moderately correlated with donation performance, suggesting that differences in referrals could help explain a small portion of the variation in donation. Regarding step 3, because we were not permitted access to all detailed OPO records, it was not possible to determine the timeliness of the referrals, how well the OPO responded to the referral, or the final decision by the OPO regarding suitability for donation. Although it has been argued that failure of hospitals to refer ventilated potential donors is a critical issue, our data suggest this is a minor component of the problem. Regarding center acceptance practices (step 4), although it has been argued this is a major problem for the US donation system, we did not find acceptance practice to be a reason for differences in OPO performance. With recent changes to allocation in which organs are allocated to many more centers than before, it is unlikely that the acceptance practice of any individual center is going to affect the overall number of transplants or OPO performance.

We therefore conclude that the vast majority of missing donors arise in the space between the referral and center acceptance. This in turn argues strongly for transparent, public access to OPO records, including the referrals and how they progress through the system. Fortunately, there is a relatively easy way to address this issue. Conditions of participation by CMS mandate that OPOs collect number of hospital deaths, results of death record reviews, and number and timeliness of referral calls from hospitals. Ensuring these data are available to oversight bodies and researchers would be a small but highly significant step in improving the system.

These findings support CMS moving forward with existing OPO oversight measures and accountability and congressional calls for publication of OPO process data to increase transparency about where organs are missed in the process. We note that 7 OPOs have already committed to such transparency through making such data available. Ensuring transparency would immediately allow research into the existing “black box” where most donations fail. Inside this black box are the different referral criteria provided by the OPO to the hospitals and performance based on these criteria. Examination of these processes could lead to insight about the utility of in-house coordinators or setting staffing ratios, for example.

Limitations

Our study has many potential limitations. It is possible we overcounted the number of potential donors. We tried to mitigate this possibility by using conservative criteria to rule out donors. Even with this approach, the lost donation potential is enormous. Hospitals were chosen based on our ability to obtain medical records and not in any randomized fashion. This could introduce bias into the findings. One of the hospitals in OPO-2 was responsible for the majority of donors, which could skew the results. Finally, our analyses include only 2 OPOs; therefore, we cannot make any general statements about other OPOs that were not part of our study.

Conclusions

In this retrospective cross-sectional analysis of organ donation, we found wide variation in the performance of OPOs, especially at individual hospitals. Addressing this opportunity could increase the organ supply, such as through targeted approaches. Multiple reports have shown that individual OPOs can increase the number of donors in a short period of time with the institution of new policies or changes in leadership.20,21 Given that only a modest increase in donors could eliminate the shortage of nonrenal organs, these steps are crucial. Taken together, our findings are consistent with the potential for dramatic increases in donor supply in the United States and suggest strategies to guide system improvement.

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.Karp SJ, Segal G, Patil DJ. Using data to achieve organ procurement organization accountability–reply. JAMA Surg. Published online October 7, 2020. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.4391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldberg D, Lynch R. Improvements in organ donation: riding the coattails of a national tragedy. Clin Transplant. 2020;34(1):e13755. doi: 10.1111/ctr.13755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldberg DS, Blumberg E, McCauley M, Abt P, Levine M. Improving organ utilization to help overcome the tragedies of the opioid epidemic. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(10):2836-2841. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldberg D, Lynch R. Response to: Deceased donors: defining drug-related deaths. Clin Transplant. 2020;34(5):e13828. doi: 10.1111/ctr.13828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network . National data search page [based on OPTN data as of November 1]. Accessed November 2, 2021. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/view-data-reports/national-data/#

- 6.Chen TK, Knicely DH, Grams ME. Chronic kidney disease diagnosis and management: a review. JAMA. 2019;322(13):1294-1304. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.14745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheehy E, Conrad SL, Brigham LE, et al. Estimating the number of potential organ donors in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(7):667-674. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa021271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.United Network for Organ Sharing . OPTN deceased donor potential study. (CTSE_Task 6_OPTN DDPS Final Report 4Review_v10.25.12_FINAL_TSR). Accessed January 1, 2023. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/media/1161/ddps_03-2015.pdf

- 9.Klassen DK, Edwards LB, Stewart DE, Glazier AK, Orlowski JP, Berg CL. The OPTN deceased donor potential study: implications for policy and practice. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(6):1707-1714. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) . Medicare and Medicaid Programs; organ procurement organizations conditions for coverage: revisions to the outcome measure requirements for organ procurement organization; 42 CFR Part 486, CMS-3380-P. Updated December 19, 2019. Accessed April 2, 2020. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/12/23/2019-27418/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-organ-procurement-organizations-conditions-for-coverage-revisions-to

- 11.Aubert O, Reese PP, Audry B, et al. Disparities in acceptance of deceased donor kidneys between the United States and France and estimated effects of increased US acceptance. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(10):1365-1374. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Connor K, Glazier A. OPO performance improvement and increasing organ transplantation: metrics are necessary but not sufficient. Am J Transplant. 2021;21(7):2325-2326. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldberg D, Karp S, Shah MB, Dubay D, Lynch R. Importance of incorporating standardized, verifiable, objective metrics of organ procurement organization performance into discussions about organ allocation. Am J Transplant. 2019;19(11):2973-2978. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldberg D, Kallan MJ, Fu L, et al. Changing metrics of organ procurement organization performance in order to increase organ donation rates in the United States. Am J Transplant. 2017;17(12):3183-3192. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lynch RJ, Doby BL, Goldberg DS, Lee KJ, Cimeno A, Karp SJ. Procurement characteristics of high- and low-performing OPOs as seen in OPTN/SRTR data. Am J Transplant. 2022;22(2):455-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Code of Federal Regulations . Human subject: definitions. Accessed January 3, 2023. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-45/subtitle-A/subchapter-A/part-46/subpart-A/section-46.102

- 17.Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients . Program-specific reports: program-specific statistics on organ transplants. Accessed January 1, 2023. https://www.srtr.org/reports/program-specific-reports/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Noordzij M, Tripepi G, Dekker FW, Zoccali C, Tanck MW, Jager KJ. Sample size calculations: basic principles and common pitfalls. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25(5):1388-1393. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.OPO Annual Public Aggregated Performance Report: final. Accessed January 10, 2023. https://qcor.cms.gov/main.jsp

- 20.Doby BL, Hanner K, Johnson S, Purnell TS, Shah MB, Lynch RJ. Results of a data-driven performance improvement initiative in organ donation. Am J Transplant. 2021;21(7):2555-2562. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niroomand E, Mantero A, Narasimman M, Delgado C, Goldberg D. Rapid improvement in organ procurement organization performance: potential for change and impact of new leadership. Am J Transplant. 2020;20(12):3567-3573. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data sharing statement