This cohort study assesses a protocol for eliminating postdischarge opioid prescriptions after major urologic cancer surgery by assessing patients who receive usual, reduced, or no opioids.

Key Points

Question

Can postdischarge opioid prescriptions be eliminated in patients undergoing major abdominopelvic cancer surgery?

Findings

In this cohort study of 686 patients, interventions included presurgical patient education, use of nonopioid analgesics, and restriction on preemptive opioid prescribing at discharge. Over 97% of patients did not require any opioid prescriptions, and postdischarge pain control and satisfaction was high with no increase in pain-related complications.

Meaning

Using nonopioid pain control measures, along with patient education, postoperative opioid prescriptions may be able to be safely eliminated without compromising pain control and recovery.

Abstract

Importance

Postoperative opioid prescriptions are associated with delayed recovery, perioperative complications, opioid use disorder, and diversion of overprescribed opioids, which places the community at risk of opioid misuse or addiction.

Objective

To assess a protocol for eliminating postdischarge opioid prescriptions after major urologic cancer surgery.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cohort study of the no opioid prescriptions at discharge after surgery (NOPIOIDS) protocol was conducted between May 2017 and June 2021 at a tertiary referral center. Patients undergoing open or minimally invasive radical cystectomy, radical or partial nephrectomy, and radical prostatectomy were sorted into the control group (usual opioids), the lead-in group (reduced opioids), and the NOPIOIDS group (no opioid prescriptions).

Interventions

The NOPIOIDS group received a preadmission educational handout, postdischarge instructions for using nonopioid analgesics, and no routine opioid prescriptions. The lead-in group received a postdischarge instruction sheet and reduced opioid prescriptions at prescribers’ discretion. The control group received opioid prescriptions at prescribers’ discretion.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary outcome measures included rate and dose of opioid prescriptions at discharge and for 30 days postdischarge. Additional outcome measures included patient-reported pain and satisfaction level, unplanned health care utilization, and postoperative complications.

Results

Of 647 opioid-naive patients (mean [SD] age, 63.6 [10.0] years; 478 [73.9%] male; 586 [90.6%] White), the rate of opioid prescriptions at discharge for the control, the lead-in, and the NOPIOIDS groups was 80.9% (157 of 194), 57.9% (55 of 95), and 2.2% (8 of 358) (Kruskal-Wallis test of medians: P < .001), and the overall median (IQR) tablets prescribed was 14 (10-20), 4 (0-5.3), and 0 (0-0) per patient in the control, lead-in, and NOPIOIDS groups, respectively (Kruskal-Wallis test of medians: P < .001). In the NOPIOIDS group, median and mean opioid dose was 0 tablets for all procedure types, with the exception of kidney procedures (mean [SD], 0.5 [1.7] tablets). Patient-reported pain surveys were received from 358 patients (72.6%) in the NOPIOIDS group, demonstrating low pain scores (mean [SD], 2.5 [0.86]) and high satisfaction scores (mean [SD], 86.6 [3.8]). There was no increase in postoperative complications in the group with no opioid prescriptions.

Conclusions and Relevance

This perioperative protocol, with emphasis on nonopioid alternatives and patient instructions, may be safe and effective in nearly eliminating the need for opioid prescriptions after major abdominopelvic cancer surgery without adversely affecting pain control, complications, or recovery.

Introduction

Opioid analgesics prescribed following surgical procedures remain a major contributor to the opioid misuse crisis in the US. Exposure to prescription opioids increases the risk of opioid misuse as well as related morbidity and mortality.1 Regardless of the complexity of surgical procedures (major or minor), postoperative opioid prescriptions can lead to persistent or chronic opioid use in 5% to 15% of patients, depending on the duration of initial opioid exposure.2,3,4 Furthermore, communities experience the consequences of opioid misuse resulting from diversion of the overprescribed, unused opioids.5 As many as 75% of patients have received excess opioid prescriptions, which become a readily available source of opioids diversion and misuse.6,7 Reportedly, 40% to 60% of opioid overdose-related deaths can be traced back to prescription opioid diversion to the community.5,8

Various regulatory initiatives including prescription limits, guidelines, and mandatory education have become ubiquitous over the last decade. Yet, the effect of these initiatives in reducing opioid prescriptions has been disappointingly slow and quite modest.9,10 Various physician-led initiatives have been used across all surgical specialties to reduce opioid prescriptions. With a few exceptions, the interventions after major surgical procedures have yielded variable reductions in opioid prescriptions ranging from 0% to 60%.11,12,13,14,15 It is well established that even transient opioid exposure after minor procedures can increase the risk of persistent, long-term opioid use by the patient.2,4,16 Due to the preventable nature of this complication, there are calls to classify development of opioid dependence as a never event in opioid-naive surgical patients.17

To address these concerns, we designed a prospective intervention protocol, no opioid prescriptions at discharge after surgery (NOPIOIDS), to test the feasibility of eliminating opioid prescriptions in patients undergoing major abdominopelvic cancer surgery (NCT04469868). The primary outcome of interest was the number of patients receiving any opioid prescription and the opioid dose prescribed per patient. Secondary outcome measures included the need for additional opioid prescriptions, patient-reported outcomes, unplanned health care utilization (telephone calls, clinic or emergency department visit, readmissions), and complication rates.

Methods

Patient Population

The study cohort included 686 consecutive patients at a tertiary care referral center undergoing either open (flank or midline incision) or minimally invasive cancer surgery (MIS), including radical cystectomy with urinary diversion, radical or partial nephrectomy, and radical prostatectomy between May 2017 and June 2021. Twenty-one health care professionals were involved in the postoperative pain management during the study period (12 residents, 3 nurse practitioners, 6 attending surgeons) who had completed the existing state-mandated education. All patients in the control and intervention groups were managed using the early recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols. Details of medications used under the ERAS protocols are provided in eTable 1 in the Supplement. The study was approved as exempt from patient consent by the institutional Committee on Human Subject Research (protocol number 5866).

Study Groups

The control (preintervention) group included 202 patients, from May 2017 to December 2018, who were given opioid prescriptions (dose, duration) at the discretion of discharging health care professional. Of note, this control group represents the intervention group from our previous study where over 30% reduction in opioid prescriptions was noted after implementation of ERAS protocol.18

In the initial feasibility (ie, lead-in group with 100 patients; January 2019 and June 2019), patients were given a 1-page informational handout that explained the rationale for avoiding opioids and using nonopioid medications for postoperative pain control (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). The opioid prescriptions were at the discretion of the prescribers who were given instructions (repeated at change of resident rotations) to try to limit opioid prescriptions to 4 days or fewer.

For the intervention (ie, NOPIOIDS group with 384 patients; July 2019 to June 2021), a standardized workflow included preferential use of nonopioid analgesics during hospital stay using electronic order sets, with instructions to prescribers (via email) to avoid writing preemptive opioid prescriptions unless a reason for opioid prescriptions was documented (pain, activity level). Instructions were repeated when staff rotations changed. The modified 1-page informational sheet regarding postoperative use of analgesics was provided with the preadmission packet and again at discharge (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). In addition, an instruction sheet with visual guidance regarding the schedule and dose of over-the-counter nonopioid analgesics for use at home was provided at discharge (eFigure 3 in the Supplement).

Data Collection

The nonopioid and opioid analgesics used during hospitalization and any opioid prescriptions data were extracted from the inpatient and outpatient electronic medical record (EMR). Further, the New York State Prescription Monitoring Program was queried at 30 days from discharge to identify any new or refills of opioid prescriptions. The opioid prescription dose was converted into standardized 5-mg oxycodone-equivalent (oxycodone, 5 mg) tablets since tablets are a more familiar prescribing unit. Other clinical and demographic information was collected from the EMR (Table 1). Patients were followed up for minimum 30 days postdischarge.

Table 1. Patient Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Control | Lead-in | NOPIOIDS | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 202 | 100 | 384 | NA |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 61.57 (11.29) | 64.84 (9.37) | 63.26 (10.2) | .03 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 28.2 (5.61) | 29.62 (5.76) | 29.07 (6.03) | .09 |

| Male, No. (%) | 144 (71.3) | 76 (76) | 287 (74.8) | .58 |

| Female, No. (%) | 58 (28.7) | 24 (24) | 97 (25.2) | |

| Race and ethnicity, No. (%) | ||||

| Asian | 2 (1.0) | 5 (5) | 7 (1.8) | .19 |

| Black | 9 (4.5) | 7 (7) | 28 (7.3) | |

| Hispanic | 0 | 0 | 3 (0.8) | |

| White | 186 (92.1) | 88 (88) | 346 (90.1) | |

| Procedure type,a No. (%) | ||||

| Open kidney | 60 (29.7) | 17 (17) | 67 (17.5) | <.001 |

| Robotic kidney | 69 (34.2) | 31 (31) | 88 (22.9) | |

| Robotic prostatectomy | 58 (28.7) | 37 (37) | 167 (43.5) | |

| Open cystectomy | 15 (7.4) | 15 (15) | 62 (16.2) | |

| Surgical approach, No. (%) | ||||

| Robotic | 127 (62.9) | 68 (68) | 255 (66.4) | .59 |

| Open | 75 (37.1) | 32 (32) | 129 (33.6) | |

| Length of stay, median (IQR), d | ||||

| Open kidney | 2 (2-4) | 2 (2-4) | 2 (1-3) | .46 |

| Robotic kidney | 2 (1-3) | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-2) | .76 |

| Robotic prostatectomy | 1 (1-1) | 1 (1-1) | 1 (1-1) | .97 |

| Open cystectomy | 6 (6-8) | 8 (7-11) | 7 (6-10) | .45 |

| Presurgical opioid use, No. (%) | 8 (4.0) | 5 (5) | 26 (6.8) | .36 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); NA, not applicable; NOPIOIDS, no opioid prescriptions at discharge after surgery.

Kidney procedures: radical nephrectomy, partial nephrectomy, and nephroureterectomy.

For the lead-in group, the focus was on the feasibility of reducing opioid prescriptions and recovery, and patient-reported pain assessment was not carried out in a standardized fashion. Some patients completed the self-reported pain scores at the health care professional’s discretion during the follow-up visit at 1 to 4 weeks after discharge. In contrast, patient-reported outcomes surveys in the NOPIOIDS group were prospectively completed by patients in real time. Completed surveys were mailed back to the office using the included stamped envelope. The patient-reported outcomes survey included a composite of several validated tools including numerical rating scale, a verbal descriptor scale, and modified Mankoski pain scale with descriptions of pain levels associated with various activity levels.19,20 Thus, our survey included a component of functional assessment that is missing from the unidimensional tools, such as numerical rating scale or verbal descriptor scale (eFigure 4 in the Supplement).

Postoperative complication rates were obtained from the institutional National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database, which includes prospectively collected, risk-adjusted data on various complications.21,22 Throughout the study period, all major cases (not just sampling) were entered in NSQIP database. We focused on complications that are potentially associated with activity level and could result from inadequate pain control. These included pneumonia, deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and readmissions. To ascertain postdischarge health care utilization, we tracked all telephone calls from patients, any new or refill opioid prescriptions, and any unplanned visits to the office or emergency department within 30 days. The reasons for the telephone calls were retrieved from the EMR where all patient contacts are recorded as a standard practice.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables (eg, age) were analyzed with 1-way analysis of variance with post hoc analysis using the Tukey multiple comparisons test. Categorical variables (eg, race and procedure type) were analyzed by contingency tables with χ2 test for inference unless expected cell counts were less than 5, in which case Fisher exact test was used. As discharge opioid data was not normally distributed, medians (IQRs) were reported with inference by Kruskal-Wallis test. Post hoc analysis after Kruskal-Wallis was by Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test. Values of 2-sided P < .05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical software R version 3.6.3 (R Foundation) was used for all of the analyses and PRISM software version 9.2.0 (GraphPad Software) was used to create the graphs.

Results

Of 686 patients, 202 (29.4%) were in the control group, 100 (14.6%) were in the lead-in group, and 384 (56%) were in the NOPIOIDS group (Table 1). Thirty-nine patients (5.7%) were using opioids prior to surgery. No difference in baseline patient characteristics for body mass index, sex, race, length of hospital stay, and preoperative opioid use was noted. The use of MIS (robotic) approach was similar among the groups.

Opioid Prescription Rate

Among 647 opioid-naive patients, the proportion of patients receiving any opioid prescription at discharge decreased significantly from 80.9% (157 of 194) in the control group, to 57.9% (55 of 95) in the lead-in group, and 2.2% (8 of 358) in the NOPIOIDS group (χ2 = 375.5; P < .001). In the NOPIOIDS group, the 8 patients receiving some opioid prescriptions at discharge had undergone either open or robotic kidney surgery. The procedure-specific opioid prescription details are provided in Table 2. None of the 229 patients undergoing radical cystectomy or prostatectomy required any opioid prescriptions at discharge (Table 2). Opioid prescription data including presurgical opioid users and the rate and dose of inpatient opioids used in various groups are detailed in eTables 2 and 3 in the Supplement, respectively.

Table 2. Opioid Prescribing Patterns in Opioid-Naive Patients.

| Group | No. (%) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Lead-in | NOPIOIDS | ||

| Patients, No. | 194 | 95 | 358 | NA |

| Any opioid prescriptions | ||||

| Overall | 157 (80.9) | 55 (57.9) | 8 (2.2) | <.001 |

| Open kidney | 52 (91.2) | 9 (60) | 4 (6.6) | <.001 |

| Robotic kidney | 50 (75.7) | 22 (71.0) | 4 (5.1) | <.001 |

| RALP | 56 (73.2) | 21 (56.8) | 0 (0) | <.001 |

| Cystectomy | 12 (80) | 6 (40) | 0 (0) | <.001 |

| Oxycodone, 5 mg, tablets, median (IQR) | ||||

| Overall | 14 (10-20) | 4 (0-5.3) | 0 (0-0) | <.001 |

| Open kidney | 16 (10-20) | 4 (0-5) | 0 (0-0) | <.001 |

| Robotic kidney | 13.6 (10-20) | 4 (0-6.7) | 0 (0-0) | <.001 |

| RALP | 14.5 (13.3-20) | 3.3 (0-6) | 0 (0-0) | <.001 |

| Cystectomy | 20 (13.3-22) | 0 (0-3.7) | 0 (0-0) | <.001 |

| Oxycodone, 5 mg, tablets, mean (SD) | ||||

| Overall | 17.5 (15.0) | 3.6 (4.2) | 0.2 (1.2) | <.001 |

| Open kidney | 20.5 (9.0) | 4.2 (5.5) | 0.6 (2.5) | <.001 |

| Robotic kidney | 16.4 (16.4) | 4.5 (4.5) | 0.3 (1.2) | <.001 |

| RALP | 15.3 (5.6) | 3.3 (3.6) | 0 (0) | <.001 |

| Cystectomy | 18.9 (8.6) | 1.7 (2.5) | 0 (0) | <.001 |

| Medications prescribed | ||||

| Hydrocodone | 3 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | .15 |

| Oxycodone | 92 (47.4) | 6 (6.3) | 1 (0.3) | <.001 |

| Tramadol | 99 (51.0) | 49 (51.6) | 7 (1.9) | <.001 |

| Total telephone calls | 34 (17.5) | 9 (9.5) | 41 (11.4) | .06 |

| Telephone calls for pain, No. (%) | 9 (4.6) | 2 (2.1) | 11 (3.1) | .47 |

| Additional opioids prescriptiona | 8 (4.1) | 1 (1.1) | 10 (2.8) | .10 |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; NOPIOIDS, no opioid prescriptions at discharge after surgery; RALP, robotic-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy.

Confirmed through a search of the New York State Prescription Monitoring Program registry for all new or refill prescriptions.

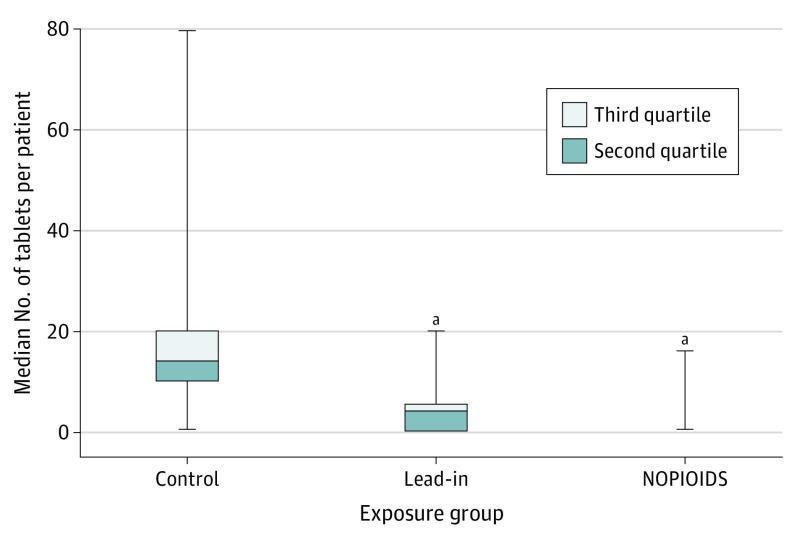

Dose of Prescribed Opioids

Overall, the median (IQR) number of oxycodone, 5 mg, tablets prescribed per patient was 14 (10-20) in the control group, 4 (0-5.3) in the lead-in group, and 0 (0-0) in the NOPIOIDS group (Kruskal-Wallis test of medians: P < .001) (Figure 1). For all individual procedure types in the NOPIOIDS group, the median (IQR) oxycodone, 5 mg, tablets prescribed was 0 (0-0) (Kruskal-Wallis test of medians: P < .001) for all procedures (Table 2). The mean (SD) oxycodone, 5 mg, tablets per patient decreased from the 17.5 (15.0) in the controls, 3.6 (4.2) in lead-in group, and 0.2 (1.2) in the NOPIOIDS groups (Kruskal-Wallis test of medians: P < .001). The mean (SD) number of opioid prescriptions was 0.6 (2.5) and 0.3 (1.2) tablets per patient for open and robotic kidney surgery, respectively, and 0 (0) tablets per patient at discharge for all other procedures. Various nonopioid analgesics used to facilitate reduction in opioid consumption by patients during hospitalization and after discharge are detailed in Table 3.

Figure 1. Box and Whisker Plots of Median 5-mg Oxycodone-Equivalent Tablets Prescribed at Discharge by Exposure Group.

Median (IQR) tablets per patient for the control group is reported. Whiskers represent the minimum and maximum tablets prescribed. NOPIOIDS indicates no opioid prescriptions at discharge after surgery.

aP < .001 compared with control group.

Table 3. Nonopioid Analgesics Used During Hospital Stay and After Discharge.

| Medicationa | Inpatient, No. (%) | Outpatient, No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lead-in | NOPIOIDS | Lead-in | NOPIOIDS | |

| Acetaminophen, tablets | 151 (78) | 326 (91.1) | 86 (89.0) | 330 (92.2) |

| TAP or intercostal nerve block, ropivacaine infiltration (for open cystectomy or kidney procedures) | 72 (37) | 294 (82.2)b | NA | NA |

| Celebrex | 34 (17.7)b | 26 (7.3) | NA | NA |

| Ibuprofen (overall) | 2 (1) | 22 | 31 (33.0) | 276 (77.1)b |

| Kidney procedures | NA | 4 (1) | 28 (29.1) | 207 (57.7) |

| Prostatectomy and cystectomy | 2 (1) | 19 (5.2) | 33 (34.6) | 295 (82.3) |

| Ketorolac, IV | 33 (17) | 73 (20.3) | NA | NA |

| Ketamine, IV | 25 (13) | 82 (22.9)b | NA | NA |

| Lidocaine, IV | 8 (4) | 63 (17.7)b | NA | NA |

| Lidocaine patch | 4 (2) | 9 (2.6) | NA | 6 (1.6) |

| Gabapentin or pregabalin, tablets | 109 (56) | 113 (31.6) | NA | 2 (0.5) |

| Cyclobenzaprine, tablets | 8 (4) | 83 (23.1)b | 1 (1) | 4 (1.0) |

Abbreviations: IV, intravenous; NOPIOIDS, no opioid prescriptions at discharge after surgery; TAP, transversus abdominis plane.

Use of over-the-counter medications, as reported by patients.

P < .05.

Unplanned Health Care Utilization

The number of telephone calls made to the office for any reason after discharge was slightly lower in the NOPIOIDS than the control group (41 [11.4%] vs 34 [17.5%], respectively; χ2 = 5.9; P = .04; Table 2). The number of calls related to inadequate pain control were similar between the controls, the in lead-in, and the NOPIOIDS groups at 9 (4.1%), 2 (2.1%), and 11 (3.1%), respectively. Most common reasons for telephone calls from the patients after discharge are detailed in eTable 4 in the Supplement. No patients in any group required an unplanned visit to the clinic or emergency department due to pain. No differences were noted before or after COVID-19 pandemic (March 2020) in the pain-related telephone calls (5 [2.6%] vs 5 [2.9%]) or readmissions (16 [8.8%] vs 15 [8.9%]).

Additional Opioid Prescriptions

Patients receiving additional (either new or refill) opioid prescriptions within 30 days of discharge were identified through query of the EMR and New York State Prescription Monitoring Program registry. The rate of additional opioid prescriptions was similar between the control, the lead-in, and the NOPIOIDS groups at 4.1% (8 of 194), 1.1% (2 of 95), and 2.8% (10 of 358), respectively (Table 2). Of the 10 patients (2.8%) receiving additional opioid prescriptions in the NOPIOIDS group, 8 had undergone kidney surgery. In 4 of these 10 patients, the additional opioid prescriptions were obtained from an outside facility (discovered through New York State Prescription Monitoring Program) after the typical follow-up period (10-25 days).

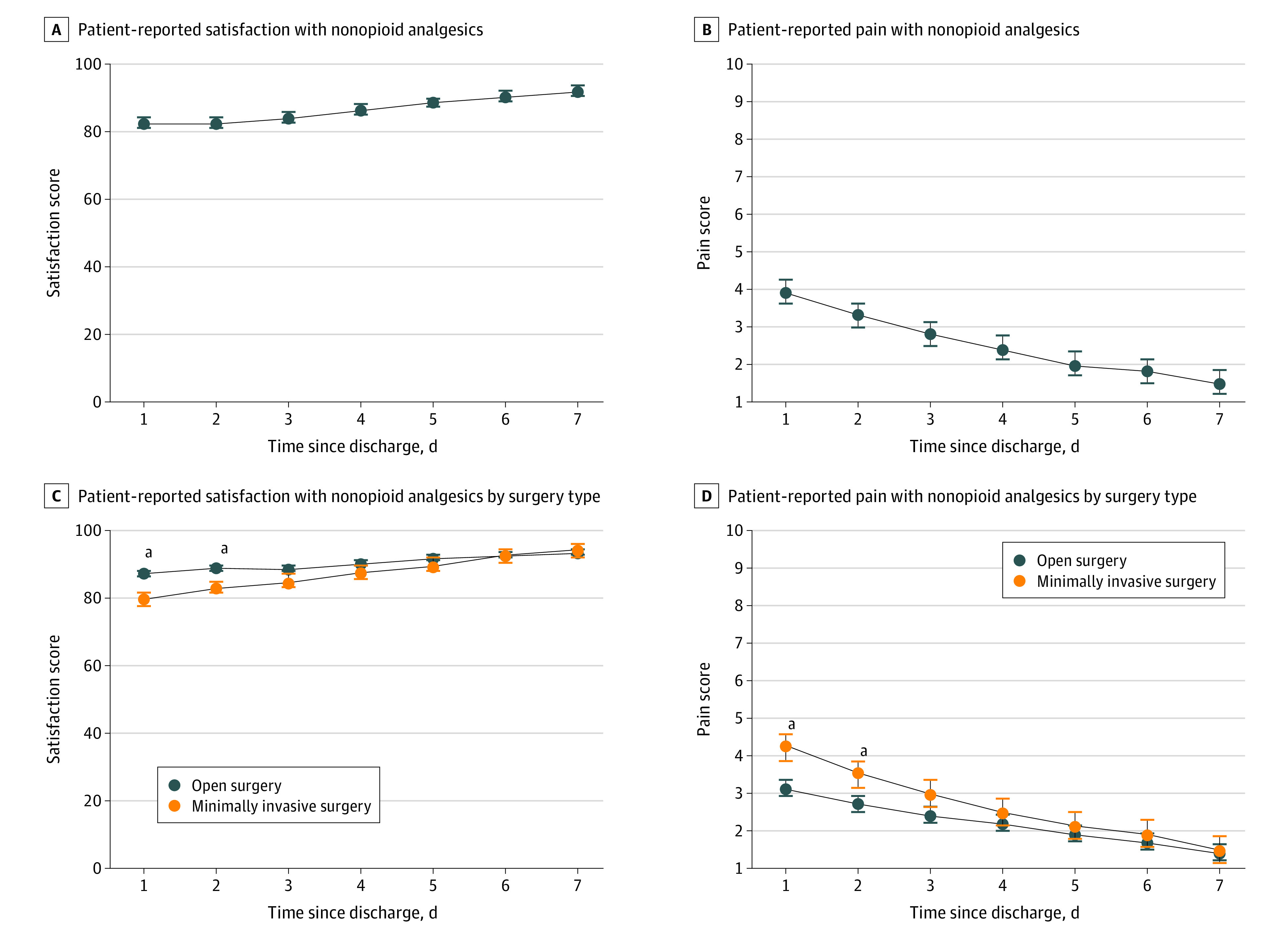

Patient-Reported Pain Assessment

In the NOPIOIDS groups, pain and satisfaction surveys were completed at home starting on postdischarge day 1. Of 358 patients, 260 (72.6%) completed the daily pain scores and 228 (63.7%) completed the satisfaction scores. Pain scores were low and overall satisfaction was high, with both scores steadily improving while using only nonopioid analgesics (Figure 2A and B). Compared with open surgery, the MIS group reported slightly higher pain scores and lower satisfaction rates for the first 2 days, but the scores became comparable by day 3 (Figure 2C and D). Of note, the mean (SD) hospital length of stay after MIS and open surgery was 1.46 (1.63) days and 5.5 (4.9) days, respectively. In contrast, lead-in groups completed the surveys during the follow-up visit at 2 to 4 weeks, at the health care professional’s discretion. Pain scores were completed by 22 (23.2%) and satisfaction scores by 15 (15.8%) in this group, demonstrating good pain control (eFigure 5 in the Supplement).

Figure 2. Patient-Reported Outcomes in the No Opioid Prescriptions at Discharge After Surgery Group.

aP < .05.

Complication Rates

The overall 30-day NSQIP complication rates were similar between the control, the lead-in, and the NOPIOIDS groups at 16.3% (33 of 202), 21% (21 of 100), and 17.0% (65 of 384) (P = .69), respectively. The rate of those complications that could potentially be associated with pain and activity level such as pneumonia, symptomatic deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and readmissions are detailed in eTable 5 in the Supplement. There was no increase in the complication rate between the group receiving usual opioid prescriptions (control group) and those receiving minimal or no opioids (lead-in and NOPIOIDS groups).

Discussion

Opioid-related deaths have continued to rise, with over 81 000 deaths being reported in the US in 2020, an upward trend that began prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. The estimated overall economic burden on society (productivity, wages, health care, criminal justice, family) throughout the opioid epidemic (2001-2020) could exceed $1.5 trillion.23 Despite the decade-long intense focus on controlling opioid prescriptions through various regulations, mandatory training, prescription monitoring programs, and public awareness campaigns, the progress against opioid prescriptions has been slow.10,24,25 Our recent meta-analysis26 demonstrated that the regulatory, systemic interventions were less impactful in reducing postoperative opioid prescriptions than the more direct interventions implemented by health care professionals within their department or hospital. In contrast to most recent reports, our current intervention cohort study demonstrates that, with rare exceptions, opioid prescriptions may be safely eliminated following major abdominopelvic cancer surgery, without compromising perioperative outcomes.

Several strategies to reduce postoperative opioid prescriptions have yielded mixed results. Anderson et al12 described the use of preoperative counseling to use scheduled nonopioid analgesics after cholecystectomy, hernia repair, or thyroidectomy, noting that 73% of patients still received an opioid prescription. Using a 5-times multiplier to the opioids used just before discharge following hepatopancreatobiliary resection, 63% of patients received an opioid prescriptions and 17% required refills.27 Fearon et al28 reduced the default number of opioid prescription tablets in the EMR from 16 to 8 oxycodone tablets for patients undergoing prostatectomy and nephrectomy, but the opioid prescriptions refill rate increased by 75%. Considering the well-established link between minor exposure to opioids and increased risk of opioid use disorder, a statistical reduction in opioid prescriptions, although important, may not to be clinically sufficient in preventing opioid misuse and opioid diversion.

Thus, we used a stricter definition of opioid prescriptions reduction, ie, eliminating the need for opioid prescriptions following major abdominal surgery. We used 3 interventions: (1) presurgical patient engagement (informational handout); (2) postdischarge patient instructions on the use (dose, schedule) of nonopioid analgesics; and (3) health care professional instructions to avoid routine, preemptive opioid prescriptions (unless a reason is documented). Less than 2.5% of patients in the NOPIOIDS group required initial or subsequent opioid prescriptions for 30 days after discharge. The overall and procedure-specific median and mean opioid dose was 0 tablets per patient, except for those undergoing kidney surgery (0.5 tablet/patient). Those few patients receiving initial or subsequent opioid prescriptions had all undergone kidney surgery. This is likely associated with limited ability to use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs due to concerns over kidney function.

Our study was conducted with the backdrop of an existing ERAS protocol. However, the ERAS protocol alone may be insufficient in controlling outpatient opioid prescriptions. Two studies of ERAS for radical cystectomy reported no significant decrease in opioid prescriptions (prescribing nearly 40 tablets/patient).29 Similar lack of reduction in opioid prescriptions was reported by Brandal et al,30 with 72% requiring opioid prescriptions after colorectal surgery. Our previous study on the association of ERAS with opioid prescriptions reported a 33% reduction in opioid prescriptions but still required 17 oxycodone tablets per patient.18 Using multipronged approach and ERAS protocols, Jacobs et al11 reported a significant reduction in opioid prescriptions to an estimated 4 oxycodone tablets per patient. Counterintuitively, Gerrish et al31 noted that ERAS protocol resulted in a significant increase in opioid prescriptions (307.4 vs 242.5 morphine milligram equivalents) and refills (28.7% vs 18.8%). These studies indicate that the issue of excessive opioid prescriptions at discharge requires separate and specific attention.

Our study demonstrated that there was no increase in patient complaints associated with pain, additional opioid prescriptions, or unplanned encounters. In the NOPIOIDS group, which essentially received no opioid prescriptions, the satisfaction scores were high and pain scores remained low. Previous studies have noted the patient-reported outcomes survey response rates to be sometimes modest (<17%) or delayed (30-90 days after discharge), introducing significant selection or recall bias.12,32 In contrast, our patient-reported outcomes surveys in the group receiving no opioid prescriptions had a high response rate and were completed in real time. Interestingly, pain scores appeared to be higher in the MIS group on days 1 to 2 compared with open surgery. This is likely associated with the shorter inpatient convalescence time for MIS (1.5 days) vs open surgery group (5.5 days). It is important to note that postdischarge day 1 for MIS is approximately postoperative day 2 to 3 whereas postdischarge day 1 for open surgery approximately corresponds with postoperative day 6 to 7. The pain scores on the same postoperative day tended to be lower in the MIS group (eg, mean pain score on postoperative day 7 for open surgery was 3.1 and for MIS it was 2.5). Furthermore, statistically significant increase in numerical rating scale does not necessarily correlate to the need for opioids. The pain scores in the MIS group on postdischarge day 1 to 2 remained below the threshold of patient desire to request opioid analgesics.33 Concerns have been raised that significant reduction is opioid prescriptions could result in inadequate pain control, decreased mobility and increase in activity-related complications. Our NSQIP data demonstrated that there was no increase in the postoperative pulmonary or thromboembolic complications or readmission rate in patients receiving no opioid prescriptions.

Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to assess virtually eliminating opioid prescriptions after major abdominopelvic surgery, including multiorgan, multiquadrant procedures. Of critical importance, near elimination of opioid prescriptions also mitigates the major concerns related to excess opioid prescriptions, such as potential for opioid diversion and misuse. The strength of our intervention study is in its relatively seamless clinical integration. Preoperative patient engagement to set appropriate expectations and postdischarge analgesic instructional handout made this intervention readily acceptable by the prescribers and the patients. These features, and the included blueprint of the perioperative and postdischarge use of opioids and nonopioid analgesics, can facilitate the adoption of this protocol by others performing abdominopelvic surgery.

Our study has some limitations. Systemic factors such as state-mandated education, dose limits, and general awareness about opioids could have influenced the prescribing behavior. However, all 3 study groups were similarly exposed to the external influences which have been in place in New York State since 2013. Of note, several other studies published within this year report a high rate of opioid prescriptions. Further, patient-reported outcomes data were not available for the control group and only from a small number in the lead-in group, which precluded any direct comparison. Also, other potentially important aspects of recovery such as sleep and activity patterns were not measured. However, we measured several patientcentric outcomes that indirectly address these concerns including patient calls about pain, unplanned encounters, and activity-related complications, which remained unchanged despite the near-absence of opioid prescriptions.

Conclusions

With the use of preoperative instructions and nonopioid alternatives during and after major abdominopelvic surgery, opioid prescriptions at discharge are rarely necessary. This study found that routine postdischarge opioid prescriptions may be eliminated without compromising pain control, patient satisfaction, health care utilization, and complication rates while simultaneously alleviating the major concerns about opioid diversion and misuse.

eTable 1. Medications used under the ERAS protocol during hospital stay

eTable 2. Opioid prescription patterns for all patients, including presurgical opioid users

eTable 3. The rate and dose of opioid analgesics used during hospital stay

eTable 4. Reason for phone calls made by the patients within 30 days after discharge

eTable 5. Incidence of 30-day NSQIP complication rates

eFigure 1. Instruction for patients in the Lead-in group

eFigure 2. Instruction for patients in the NOPIOIDS group

eFigure 3. Instruction for taking pain medications after discharge

eFigure 4. Patient self-assessment of pain control after discharge

eFigure 5. Patient-reported pain scores and satisfaction scores in the Lead-in group

References

- 1.Lin N, Dabas E, Quan ML, et al. Outcomes and healthcare utilization among new persistent opioid users and non-opioid users after curative-intent surgery for cancer. Ann Surg. Published online July 29, 2021. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shah A, Hayes CJ, Martin BC. Characteristics of initial prescription episodes and likelihood of long-term opioid use: United States, 2006-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(10):265-269. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6610a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brummett CM, Waljee JF, Goesling J, et al. New persistent opioid use after minor and major surgical procedures in US adults. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(6):e170504. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barham DW, McMann LP, Musser JE, et al. Routine prescription of opioids for post-vasectomy pain control associated with persistent use. J Urol. 2019;202(4):806-810. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000000304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han B, Compton WM, Blanco C, Crane E, Lee J, Jones CM. Prescription opioid use, misuse, and use disorders in U.S. adults: 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(5):293-301. doi: 10.7326/M17-0865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bates C, Laciak R, Southwick A, Bishoff J. Overprescription of postoperative narcotics: a look at postoperative pain medication delivery, consumption and disposal in urological practice. J Urol. 2011;185(2):551-555. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.09.088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel HD, Faisal FA, Patel ND, et al. Effect of a prospective opioid reduction intervention on opioid prescribing and use after radical prostatectomy: results of the Opioid Reduction Intervention for Open, Laparoscopic, and Endoscopic Surgery (ORIOLES) Initiative. BJU Int. 2020;125(3):426-432. doi: 10.1111/bju.14932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall AJ, Logan JE, Toblin RL, et al. Patterns of abuse among unintentional pharmaceutical overdose fatalities. JAMA. 2008;300(22):2613-2620. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agarwal S, Bryan JD, Hu HM, et al. Association of state opioid duration limits with postoperative opioid prescribing. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(12):e1918361. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.18361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chua K-P, Kimmel L, Brummett CM. Disappointing early results from opioid prescribing limits for acute pain. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(5):375-376. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.5891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobs BL, Rogers D, Yabes JG, et al. Large reduction in opioid prescribing by a multipronged behavioral intervention after major urologic surgery. Cancer. 2021;127(2):257-265. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson M, Hallway A, Brummett C, Waljee J, Englesbe M, Howard R. Patient-reported outcomes after opioid-sparing surgery compared with standard of care. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(3):286-287. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.5646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu CY, Schumm MA, Hu TX, et al. Patient-centered decision-making for postoperative narcotic-free endocrine surgery: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(11):e214287-e214287. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.4287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaafarani HMA, Eid AI, Antonelli DM, et al. Description and impact of a comprehensive multispecialty multidisciplinary intervention to decrease opioid prescribing in surgery. Ann Surg. 2019;270(3):452-462. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiu AS, Jean RA, Hoag JR, Freedman-Weiss M, Healy JM, Pei KY. Association of lowering default pill counts in electronic medical record systems with postoperative opioid prescribing. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(11):1012-1019. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.2083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alam A, Gomes T, Zheng H, Mamdani MM, Juurlink DN, Bell CM. Long-term analgesic use after low-risk surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(5):425-430. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barth RJ Jr, Waljee JF. Classification of opioid dependence, abuse, or overdose in opioid-naive patients as a “never event”. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(7):543-544. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.0432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carnes KM, Ata A, Cangero T, Mian BM. Impact of enhanced recovery after surgery protocols on opioid prescriptions at discharge after major urological cancer surgery. Urol Pract. 2021;8(2):270-276. doi: 10.1097/UPJ.0000000000000207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Breivik H, Borchgrevink PC, Allen SM, et al. Assessment of pain. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101(1):17-24. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Douglas ME, Randleman ML, DeLane AM, Palmer GA. Determining pain scale preference in a veteran population experiencing chronic pain. Pain Manag Nurs. 2014;15(3):625-631. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2013.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.About ACS NSQIP. American College of Surgeons. Accessed January 3, 2023. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/data-and-registries/acs-nsqip/about-acs-nsqip/

- 22.Dimick JB, Osborne NH, Hall BL, Ko CY, Birkmeyer JD. Risk adjustment for comparing hospital quality with surgery: how many variables are needed? J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210(4):503-508. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.01.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Economic toll of opioid crisis in U.S. exceeded $1 trillion since 2001. Alatrum. Published February 13, 2018. Accessed January 10, 2022. https://altarum.org/news/economic-toll-opioid-crisis-us-exceeded-1-trillion-2001

- 24.Porter SB, Glasgow AE, Yao X, Habermann EB. Association of Florida house bill 21 with postoperative opioid prescribing for acute pain at a single institution. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(3):263-264. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.4913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.US opioid dispensing rate map. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed January 10, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/rxrate-maps/index.html

- 26.Carnes KM, Singh Z, Ata A, Mian BM. Interventions to reduce opioid prescriptions following urological surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Urol. 2022;207(5):969-981. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000002447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Day RW, Newhook TE, Dewhurst WL, et al. Assessing the 5×-multiplier calculation to reduce discharge opioid prescription volumes after inpatient surgery. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(12):1166-1167. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.3527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fearon NJ, Benfante N, Assel M, et al. Standardizing opioid prescriptions to patients after ambulatory oncologic surgery reduces overprescription. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2020;46(7):410-416. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2020.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greenberg DR, Kee JR, Stevenson K, et al. Implementation of a reduced opioid utilization protocol for radical cystectomy. Bladder Cancer. 2020;6:33-42. doi: 10.3233/BLC-190243 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brandal D, Keller MS, Lee C, et al. Impact of enhanced recovery after surgery and opioid-free anesthesia on opioid prescriptions at discharge from the hospital: a historical-prospective study. Anesth Analg. 2017;125(5):1784-1792. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gerrish AW, Fogel S, Lockhart ER, Nussbaum M, Adkins F. Opioid prescribing practices during implementation of an enhanced recovery program at a tertiary care hospital. Surgery. 2018;164(4):674-679. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2018.06.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Howard R, Brown CS, Lai YL, et al. The association of postoperative opioid prescriptions with patient outcomes. Ann Surg. 2021;276(6):e1076-e1082. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Dijk JF, Kappen TH, Schuurmans MJ, van Wijck AJ. The relation between patients’ NRS pain scores and their desire for additional opioids after surgery. Pain Pract. 2015;15(7):604-609. doi: 10.1111/papr.12217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Medications used under the ERAS protocol during hospital stay

eTable 2. Opioid prescription patterns for all patients, including presurgical opioid users

eTable 3. The rate and dose of opioid analgesics used during hospital stay

eTable 4. Reason for phone calls made by the patients within 30 days after discharge

eTable 5. Incidence of 30-day NSQIP complication rates

eFigure 1. Instruction for patients in the Lead-in group

eFigure 2. Instruction for patients in the NOPIOIDS group

eFigure 3. Instruction for taking pain medications after discharge

eFigure 4. Patient self-assessment of pain control after discharge

eFigure 5. Patient-reported pain scores and satisfaction scores in the Lead-in group