Abstract

Real-time surveillance of infectious diseases at schools or in communities is often hampered by delays in reporting due to resource limitations and infrastructure issues. By incorporating quantitative PCR and genome sequencing, wastewater surveillance has been an effective complement to public health surveillance at the community and building-scale for pathogens such as poliovirus, SARS-CoV-2, and even the monkeypox virus. In this study, we asked whether wastewater surveillance programs at elementary schools could be leveraged to detect RNA from influenza viruses shed in wastewater. We monitored for influenza A and B viral RNA in wastewater from six elementary schools from January to May 2022. Quantitative PCR led to the identification of influenza A viral RNA at three schools, which coincided with the lifting of COVID-19 restrictions and a surge in influenza A infections in Las Vegas, Nevada, USA. We performed genome sequencing of wastewater RNA, leading to the identification of a 2021–2022 vaccine-resistant influenza A (H3N2) 3C.2a1b.2a.2 subclade. We next tested wastewater samples from a treatment plant that serviced the elementary schools, but we were unable to detect the presence of influenza A/B RNA. Together, our results demonstrate the utility of near-source wastewater surveillance for the detection of local influenza transmission in schools, which has the potential to be investigated further with paired school-level influenza incidence data.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2; COVID-19; Influenza; Wastewater; Elementary schools, mutation; H3N2

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The global incidence of influenza cases and deaths was reduced to an unprecedented low level during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and early 2021 (Dhanasekaran et al., 2022; Groves et al., 2022). Public health directives such as social distancing and masking, coupled with a reduction in travel, likely contributed to the reduced community transmission of influenza viruses (Fong et al., 2020); however, relaxation of COVID-19 restrictions during the 2021/2022 influenza season resulted in the circulation of a new influenza H3N2 subclade called 3C.2a1b.2a.2 (Melidou et al., 2022). Due to mutations in key antigenic sites on hemagglutinin (HA) of 3C.2a1b.2a.2, influenza vaccine effectiveness was found to be low during reported outbreaks in the 2021/2022 influenza season (Bolton et al., 2022; Melidou et al., 2022). The emergence and evolution of new influenza strains highlight the growing need to develop new surveillance programs that 1) detect and identify circulating strains to limit community transmission and 2) guide the development of efficacious vaccines.

Wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE) has been adapted widely during the COVID-19 pandemic to measure changing levels of SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19) and microbial communities at the community and facility-level (Ahmed et al., 2020; de Jonge et al., 2022; Farkas et al., 2022; Gerrity et al., 2021, Gerrity et al., 2022; Harrington et al., 2022; Joshi et al., 2022; Kirby et al., 2022; Li et al., 2022; Nelson, 2022; Sellers et al., 2022; Vo et al., 2022b, Vo et al., 2022c; Wolfe et al., 2022b). Infected individuals shed viral RNA through urine, stool, or saliva which enters sewer lines through toilets, sinks, and shower drains (Schmitz et al., 2021; Tiwari et al., 2021). When levels of SARS-CoV-2 RNA increase in sewage entering wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), increasing case infections from communities served by WWTPs are observed. Similarly, when viral levels in wastewater decrease, a corresponding decrease in cases is observed, highlighting the utility of WBE as a real-time surveillance tool (Castro-Gutierrez et al., 2022; Godinez et al., 2022; Zdenkova et al., 2022). In addition to the quantification of viral levels in sewage, genome sequencing of nucleic acids extracted from wastewater has led to the identification of variants of interest (VOI) and concern (VOC) (Brumfield et al., 2022; Karthikeyan et al., 2022; Nemudryi et al., 2020; Reynolds et al., 2022; Tamáš et al., 2022; Vo et al., 2022a). As a result, wastewater sampling from treatment plants or buildings can provide operational information about the deployment of appropriate therapeutics and vaccines that target circulating variants.

Leveraging experience from the COVID-19 pandemic, we reasoned that community-scale wastewater monitoring programs could be used to detect influenza viruses in municipal wastewater. In addition, we queried whether our approach could be adapted to building-scale applications, specifically at elementary schools, since younger children are more susceptible to influenza and have high prevalence of symptomatic infections relative to other age groups (Ruf and Knuf, 2014; Sheu et al., 2016). Here, we aimed to interrogate 1) community and facility-level transmission of influenza in Southern Nevada through wastewater and public health surveillance and 2) genome sequencing of wastewater for the identification of viral variants. Our data highlight how wastewater programs can be deployed to detect local influenza transmission in schools and how genome sequencing from wastewater can lead to the identification of novel, vaccine-resistant influenza strains within this vulnerable subpopulation.

2. Methods

2.1. Wastewater sample collection and preparation

Wastewater surveillance at six elementary schools, each serving ~200–800 students in Southern Nevada, was conducted between January 20th and June 13th of 2022. All six schools were located in the Las Vegas/Henderson school districts and were from similar socioeconomic and ethnicity (~39 % White, ~32 % Hispanic, ~11 % Black, and ~ 10 % Asian) regions. Grab samples were collected from the elementary school manholes three days per week (on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays) between 12:00 and 1:00 pm; three samples were collected every 5–10 min to generate a manual composite over 30 min of ~500-1000mls. In addition, 10 L of grab primary effluent was collected at ~10:00 am every Monday from a corresponding wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) serving approximately one million local residents and the schools in question (Gerrity et al., 2021).

2.2. Quantification of influenza A and B viral levels

For quantification and sequencing, nucleic acids were extracted from wastewater using the Wizard Enviro TNA Kit (Promega Cat #A2991) according to the manufacturer's instructions and eluted in 100 μL of RNase-free dH2O. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using the LunaScript RT SuperMix Kit (NEB). Quantification of influenza RNA in wastewater was performed using a Bio-Rad Opus qPCR instrument using CDC's Influenza SARS-CoV-2 multiplex assay (M gene for influenza A and NS2 gene for Influenza B) (CDC, 2020). Reactions, in triplicate, were performed in a final volume of 10 μL containing: 1 μL template cDNA, 5 μl of 2× KiCqStart Probe qPCR ReadyMix (Millipore-Sigma), 1 μL of 9 μM primer and 2.5 μM probe mix, and 3 μL of nuclease-free water. Primers and probes were purchased from Millipore-Sigma and Integrated DNA Technologies, respectively. Primer and probe details include: Influenza A forward 1 (5′-CAA GAC CAA TCY TGT CAC CTC TGA C-3′), Influenza A forward 2 (5′-CAA GAC CAA TYC TGT CAC CTY TGA C-3′), Influenza A reverse 1 (5′-GCA TTY TGG ACA AAV CGT CTA CG-3′), Influenza A reverse 2 (5′-GCA TTT TGG ATA AAG CGT CTA CG-3′), Influenza A probe (5′-FAM- TGCAGTCCT/ ZEN/CGCTCACTGGGCACG/IABkFQ-3′), Influenza B forward (5′-TCC TCA AYT CAC TCT TCG AGC G-3′), Influenza B reverse (5′- CGG TGC TCT TGA CCA AAT TGG-3′), Influenza B probe (5′-HEX- CCAATTCGA/ZEN/ GCAGCTGAAACTGCGGTG/3IABkFQ-3′). Standard curves for influenza A were generated using a synthetic H3N2 RNA control (Twist Biosciences). Pepper mild mottle virus (PMMoV) was measured to determine the presence of human fecal content in the wastewater and used as a normalizing control. The concentration of PMMoV was determined by amplification of experimental samples along with dilutions of a PMMoV standard (provided as part of the GoTaq Enviro PMMoV Quant Kit from Promega) using quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR) with primers (forward: 5′-GAG TGG TTT GAC CTT AAC GTT TGA-3′; reverse: 5′- TTG TCG GTT GCA ATG CAA GT-3′) and probe (5′-TxRd- CCTACCGAAGCAAATG-BHQ2–3′) specific for PMMoV (Abdool-Ghany et al., 2022; Mondal et al., 2021). A no-template control was also included in each standard curve for the different targets. Cycling conditions included a denaturation step of 95 °C for 2 min followed by amplification at 95 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 30 s for 45 cycles. Public health surveillance for influenza in Las Vegas included data collected from local acute care hospitals and healthcare providers. Clinical cases were confirmed by PCR, culture, immunofluorescent antibody staining, IHC antigen staining, rapid influenza diagnostic tests with hospitalizations for 24 h or longer, or death certificates (SNHD, 2022). Given that influenza morbidity is not reportable to public health and that the majority of infected individuals suffer from mild forms of influenza, we expect that reported case counts represent an underestimation of total influenza infections.

2.3. Targeted genome sequencing and variant analyses

Whole genome sequencing libraries were constructed using the CleanPlex Respiratory Virus Research Panel from Paragon Genomics according to manufacturer's instructions. This panel combines SARS-CoV-2 whole genome amplification with 149 primers covering multiple gene segments for influenza A (H1N1,H1N2,H3N2), influenza B, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) types A and B. >10 ng of total RNA was processed for first-strand cDNA synthesis. Libraries were sequenced using an Illumina NextSeq 500 platform and a mid-output v2.5 (300 cycles) flow cell. Illumina adapter sequences were trimmed from reads using cutadapt v3.2. All sequencing reads were mapped to the respiratory pathogen genomes using bwa mem v0.7.17-r1188. Amplicon primers were trimmed from aligned reads using fgbio TrimPrimers v1.3.0 and segment 1 (hemagglutinin gene) consensus sequences were generated with iVar consensus v1.3. Genome coverages were calculated by samtools coverage (v1.10). The segment 1 consensus sequences were analyzed with Nextclade (v.1.8.1) and the phylogenetic tree was visualized on the Auspice webserver. Genome coverage of 6/8 influenza A genomic segments was >80 % with a median sequencing depth of >100-fold. However, the percentage of the full genome covered at 100-fold sequencing depth for all samples from the three schools was >55 % (Table S1). Raw fastq files are available on the National Center for Biotechnology Information website under BioProject PRJNA856656.

3. Human subjects statement

The Institutional Biosafety Committee (IBC) of the University of Nevada Las Vegas approved methods and techniques used in this study.

4. Results and discussion

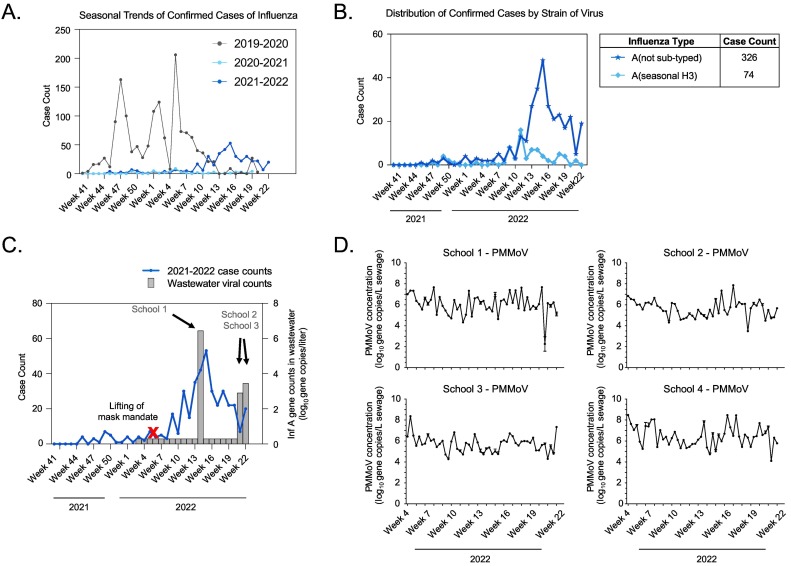

Influenza incidence in Southern Nevada remained uncharacteristically low throughout the COVID-19 pandemic but started to increase in the late spring of 2022, peaking in week 15 (Fig. 1A). During this surge, the Southern Nevada Public Health Laboratory confirmed 403 hospitalized cases through public health surveillance, with 98.3 % positive for influenza A (Fig. 1B). At this time, the influenza vaccination rate was 21.3 % across all 2.4 million residents of the region and 25.1 % for the 0–10 age group (i.e., elementary school age) (DPBH, 2022). Notably, at least two contributing factors led to a late influenza season. During the COVID-19 surge between December 2021 and February 2022, cases of influenza were at historical lows due to social distancing and hygiene practices. Second, Nevada lifted its mask mandate during week 6 of 2022, at which point face coverings were no longer required in indoor public places, including schools.

Fig. 1.

Characterization of influenza trends in Southern Nevada, including clinical and wastewater surveillance data. (A) Trends in confirmed cases of influenza plotted over three years: 2019–2020, 2020–2021, and 2021–2022. (B) Distribution of influenza A strains among confirmed cases in 2021–2022. (C) Correlation of weekly 2021–2022 influenza cases (left y-axis) with wastewater concentrations of influenza A RNA (right y-axis) detected in three of six elementary schools. (D) Wastewater concentrations of PMMoV RNA at four of the six elementary schools during the sampling period.

Similar to other studies (Dumke et al., 2022; Mercier et al., 2022; Wolfe et al., 2022a), we asked whether wastewater could be analyzed to observe trends from influenza shedding—in this case at elementary schools—and confirmed cases at the community-level. To ensure that wastewater samples were processed appropriately, we also measured RNA levels of PMMoV—a plant virus that is found commonly in human fecal material. Across the sampling period, we detected PMMoV RNA at all six schools (Fig. 1D and Suppl. Fig. 1), while influenza A viral RNA was detected at only three schools. Influenza RNA was not detected during the first three months of 2022, but influenza A was detected at School 1 at a concentration of 2.7 × 106 gene copies per liter (gc/L) in week 14, at School 2 at a concentration of 8.0 × 102 gc/L in week 21, and at School 3 at a concentration of 2.8 × 103 gc/L in week 22 (Fig. 1C). Interestingly, wastewater surveillance at the corresponding WWTP servicing the schools did not yield positive results for influenza A or for influenza B by qPCR, suggesting sensitivity limitations for influenza RNA detection at the community-scale (Heijnen and Medema, 2011). Corresponding clinical surveillance data indicated that detection of influenza A in elementary school wastewater occurred during increasing community transmission of influenza A in Las Vegas (Fig. 1C). This period of increased transmission occurred shortly after 1) the COVID-19 BA.1 surge ended, 2) lifting of a mask mandate, and 3) a time with relatively low influenza vaccination coverage.

Suppl. Fig. 1.

Wastewater concentrations of PMMoV RNA at elementary school five and six during the sampling period.

We next performed tiled-amplicon sequencing and determined that H3N2 was present in the three influenza-positive wastewater samples (Fig. 2 ). Several unique mutations could be annotated across the genomes revealing that all belonged to the 2a.2 subgroup of the influenza A (H3N2) subclade 3C.2a1b.2a and demonstrating the feasibility of tracking influenza lineages through wastewater (Delahoy et al., 2021; Melidou et al., 2022; Wolfe et al., 2022a). Vaccines against influenza A (H3N2) are historically less efficacious than for other strains since H3N2 evolves more rapidly to escape immunity (Delahoy et al., 2021). In fact, the 2021–2022 influenza vaccines for the northern hemisphere were eventually updated to protect against both the 2a.1 and 2a.2 subgroups of the 3C.2a1b.2a subclade (Delahoy et al., 2021; Melidou et al., 2022). With this update, vaccinated children in Las Vegas may have been partially protected against 2a.2., but either due to low vaccination coverage or vaccine evasion, influenza A infections were still apparent based on clinical surveillance and detection of the viral RNA in wastewater at three of six elementary schools.

Fig. 2.

Identification of a vaccine-resistant H3N2 subclade. Phylogenetic comparison of the three H3N2 genomes from the elementary schools with the 2022 Nevada reference (NV ref) and the 3C.2a1b.2a subclade.

A limitation of this study was that it was not possible to assess health data directly from the elementary schools, including influenza vaccine coverage or confirmed cases at the time of the wastewater detections. Nonetheless, our study and others (Dumke et al., 2022; Mercier et al., 2022; Wolfe et al., 2022a) demonstrate the feasibility of leveraging wastewater to detect influenza outbreaks and identify subtypes at the building-level. This could ultimately help public health officials mitigate the impacts of influenza outbreaks by more rapidly deploying interventions or assess the efficacy of future vaccines.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

Summary statistics for influenza wastewater libraries and alignment to reference influenza A (H3N2) virus segments (NC_007366.1-NC_007373.1).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Van Vo, Anthony Harrington, Ching-Lan Chang: Methodology, Supervision, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft.

Hayley Baker, Nabih Ghani, Natnael Basinew, Jose Yani Itorralba1, Richard L. Tillett, Michael Moshi, Elizabeth Dahlmann, Tiffany Familara, Moonis Ghani, Sage Boss, Fritz Vanderford, Austin Tang, Richard Gu, Alice Matthews: Methodology, Resource, Writing – reviewing & editing.

Katerina Papp, Eakalak Khan, Carolina Koutras, Cassius Lockett, Horng-Yuan Kan: Resource, Writing – reviewing & editing.

Daniel Gerrity, Edwin C. Oh: Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Visualization, Supervision, Investigation, Writing – original draft.

Anthony Harrington, Van Vo, and Ching-Lan Chang are co-first authors and contributed equally.

Declaration of competing interest

Dr. Carolina Koutras is an employee of R-Zero Systems.

Acknowledgments

ECO is supported by NIH grants: GM103440 and MH109706 and a CARES Act grant from the Nevada Governor's Office of Economic Development. VV, HYK, CL, DG, and ECO are supported by a CDC grant: NH75OT000057-01-00. VV was supported by faculty opportunity funding from the UNLV Research Foundation and the UNLV Foundation through the Division of Research at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. We would like to acknowledge personnel at the collaborating wastewater agencies and the Southern Nevada Public Health Laboratory for their assistance with sample logistics and data access.

Editor: Kyle Bibby

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Abdool-Ghany A.A., Sahwell P.J., Klaus J., Gidley M.L., Sinigalliano C.D., Solo-Gabriele H.M. Fecal indicator bacteria levels at a marine beach before, during, and after the COVID-19 shutdown period and associations with decomposing seaweed and human presence. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;851 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed W., Angel N., Edson J., Bibby K., Bivins A., O’Brien J.W., Choi P.M., Kitajima M., Simpson S.L., Li J., Tscharke B., Verhagen R., Smith W.J.M., Zaugg J., Dierens L., Hugenholtz P., Thomas K.V., Mueller J.F. First confirmed detection of SARS-CoV-2 in untreated wastewater in Australia: a proof of concept for the wastewater surveillance of COVID-19 in the community. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;728 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton M.J., Ort J.T., McBride R., Swanson N.J., Wilson J., Awofolaju M., Furey C., Greenplate A.R., Drapeau E.M., Pekosz A., Paulson J.C., Hensley S.E. Antigenic and virological properties of an H3N2 variant that continues to dominate the 2021–22 Northern Hemisphere influenza season. Cell Rep. 2022;39 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumfield K.D., Leddy M., Usmani M., Cotruvo J.A., Tien C.-T., Dorsey S., Graubics K., Fanelli B., Zhou I., Registe N., Dadlani M., Wimalarante M., Jinasena D., Abayagunawardena R., Withanachchi C., Huq A., Jutla A., Colwell R.R. Microbiome Analysis for Wastewater Surveillance during COVID-19. mBio. 2022 doi: 10.1128/mbio.00591-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Gutierrez V., Hassard F., Vu M., Leitao R., Burczynska B., Wildeboer D., Stanton I., Rahimzadeh S., Baio G., Garelick H., Hofman J., Kasprzyk-Hordern B., Kwiatkowska R., Majeed A., Priest S., Grimsley J., Lundy L., Singer A.C., Di Cesare M. Monitoring occurrence of SARS-CoV-2 in school populations: a wastewater-based approach. PLoS One. 2022;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0270168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2020. CDC's influenza SARS-CoV-2 multiplex assay [WWW Document]https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/rt-pcr-panel-primer-probes.html URL. (accessed 1.25.22) [Google Scholar]

- Delahoy M.J., Mortenson L., Bauman L., Marquez J., Bagdasarian N., Coyle J., Sumner K., Lewis N.M., Lauring A.S., Flannery B., Patel M.M., Martin E.T. Influenza A(H3N2) outbreak on a university campus - Michigan, October-November 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1712–1714. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7049e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhanasekaran V., Sullivan S., Edwards K.M., Xie R., Khvorov A., Valkenburg S.A., Cowling B.J., Barr I.G. Human seasonal influenza under COVID-19 and the potential consequences of influenza lineage elimination. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:1721. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29402-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DPBH Influenza [WWW Document] 2022. https://dpbh.nv.gov/Programs/Flu/Influenza/ URL. (accessed 10.13.22)

- Dumke R., Geissler M., Skupin A., Helm B., Mayer R., Schubert S., Oertel R., Renner B., Dalpke A.H. Simultaneous detection of SARS-CoV-2 and influenza virus in wastewater of two cities in southeastern Germany, January to May 2022. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022;19:13374. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192013374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkas K., Pellett C., Alex-Sanders N., Bridgman M.T.P., Corbishley A., Grimsley J.M.S., Kasprzyk-Hordern B., Kevill J.L., Pântea I., Richardson-O’Neill I.S., Lambert-Slosarska K., Woodhall N., Jones D.L. Comparative assessment of filtration- and precipitation-based methods for the concentration of SARS-CoV-2 and other viruses from wastewater. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022;10 doi: 10.1128/spectrum.01102-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong M.W., Gao H., Wong J.Y., Xiao J., Shiu E.Y.C., Ryu S., Cowling B.J. Nonpharmaceutical measures for pandemic influenza in nonhealthcare settings-social distancing measures. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26:976–984. doi: 10.3201/eid2605.190995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrity D., Papp K., Stoker M., Sims A., Frehner W. Early-pandemic wastewater surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 in southern Nevada: methodology, occurrence, and incidence/prevalence considerations. Water Res.X. 2021;10 doi: 10.1016/j.wroa.2020.100086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrity D., Papp K., Dickenson E., Ejjada M., Marti E., Quinones O., Sarria M., Thompson K., Trenholm R.A. Characterizing the chemical and microbial fingerprint of unsheltered homelessness in an urban watershed. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;840 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.156714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godinez A., Hill D., Dandaraw B., Green H., Kilaru P., Middleton F., Run S., Kmush B.L., Larsen D.A. High sensitivity and specificity of dormitory-level wastewater surveillance for COVID-19 during fall semester 2020 at Syracuse University, New York. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022;19:4851. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19084851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves H.E., Papenburg J., Mehta K., Bettinger J.A., Sadarangani M., Halperin S.A., Morris S.K., for members of the Canadian Immunization Monitoring Program Active (IMPACT) The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on influenza-related hospitalization, intensive care admission and mortality in children in Canada: a population-based study. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2022;7 doi: 10.1016/j.lana.2021.100132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington A., Vo V., Papp K., Tillett R.L., Chang C.-L., Baker H., Shen S., Amei A., Lockett C., Gerrity D., Oh E.C. Urban monitoring of antimicrobial resistance during a COVID-19 surge through wastewater surveillance. Sci. Total Environ. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heijnen L., Medema G. Surveillance of influenza A and the pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 in sewage and surface water in the Netherlands. J. Water Health. 2011;9:434–442. doi: 10.2166/wh.2011.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jonge E.F., Peterse C.M., Koelewijn J.M., van der Drift A.-M.R., van der Beek R.F.H.J., Nagelkerke E., Lodder W.J. The detection of monkeypox virus DNA in wastewater samples in the Netherlands. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;852 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi M., Kumar M., Srivastava V., Kumar D., Rathore D.S., Pandit R., Graham D.W., Joshi C.G. Genetic sequencing detected the SARS-CoV-2 delta variant in wastewater a month prior to the first COVID-19 case in Ahmedabad (India) Environ. Pollut. 2022;310 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2022.119757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karthikeyan S., Levy J.I., De Hoff P., Humphrey G., Birmingham A., Jepsen K., Farmer S., Tubb H.M., Valles T., Tribelhorn C.E., Tsai R., Aigner S., Sathe S., Moshiri N., Henson B., Mark A.M., Hakim A., Baer N.A., Barber T., Belda-Ferre P., Chacón M., Cheung W., Cresini E.S., Eisner E.R., Lastrella A.L., Lawrence E.S., Marotz C.A., Ngo T.T., Ostrander T., Plascencia A., Salido R.A., Seaver P., Smoot E.W., McDonald D., Neuhard R.M., Scioscia A.L., Satterlund A.M., Simmons E.H., Abelman D.B., Brenner D., Bruner J.C., Buckley A., Ellison M., Gattas J., Gonias S.L., Hale M., Hawkins F., Ikeda L., Jhaveri H., Johnson T., Kellen V., Kremer B., Matthews G., McLawhon R.W., Ouillet P., Park D., Pradenas A., Reed S., Riggs L., Sanders A., Sollenberger B., Song A., White B., Winbush T., Aceves C.M., Anderson Catelyn, Gangavarapu K., Hufbauer E., Kurzban E., Lee J., Matteson N.L., Parker E., Perkins S.A., Ramesh K.S., Robles-Sikisaka R., Schwab M.A., Spencer E., Wohl S., Nicholson L., Mchardy I.H., Dimmock D.P., Hobbs C.A., Bakhtar O., Harding A., Mendoza A., Bolze A., Becker D., Cirulli E.T., Isaksson M., Schiabor Barrett K.M., Washington N.L., Malone J.D., Schafer A.M., Gurfield N., Stous S., Fielding-Miller R., Garfein R.S., Gaines T., Anderson Cheryl, Martin N.K., Schooley R., Austin B., MacCannell D.R., Kingsmore S.F., Lee W., Shah S., McDonald E., Yu A.T., Zeller M., Fisch K.M., Longhurst C., Maysent P., Pride D., Khosla P.K., Laurent L.C., Yeo G.W., Andersen K.G., Knight R. Wastewater sequencing reveals early cryptic SARS-CoV-2 variant transmission. Nature. 2022 doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05049-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby A.E., Welsh R.M., Marsh Z.A., Yu A.T., Vugia D.J., Boehm A.B., Wolfe M.K., White B.J., Matzinger S.R., Wheeler A., Bankers L., Andresen K., Salatas C., New York City Department of Environmental Protection. Gregory D.A., Johnson M.C., Trujillo M., Kannoly S., Smyth D.S., Dennehy J.J., Sapoval N., Ensor K., Treangen T., Stadler L.B., Hopkins L. Notes from the field: early evidence of the SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 (Omicron) variant in community wastewater - United States, November-December 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2022;71:103–105. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7103a5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Mazurowski L., Dewan A., Carine M., Haak L., Guarin T.C., Dastjerdi N.G., Gerrity D., Mentzer C., Pagilla K.R. Longitudinal monitoring of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater using viral genetic markers and the estimation of unconfirmed COVID-19 cases. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;817 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.152958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melidou A., Ködmön C., Nahapetyan K., Kraus A., Alm E., Adlhoch C., Mooks P., Dave N., Carvalho C., Meslé M.M., Daniels R., Pebody R., Members of the WHO European Region influenza surveillance network. Members of the WHO European Region influenza surveillance network that contributed virus characterisation data Influenza returns with a season dominated by clade 3C.2a1b.2a.2 A(H3N2) viruses, WHO European Region, 2021/22. Euro Surveill. 2022;27 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2022.27.15.2200255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercier E., D’Aoust P.M., Thakali O., Hegazy N., Jia J.-J., Zhang Z., Eid W., Plaza-Diaz J., Kabir M.P., Fang W., Cowan A., Stephenson S.E., Pisharody L., MacKenzie A.E., Graber T.E., Wan S., Delatolla R. Municipal and neighbourhood level wastewater surveillance and subtyping of an influenza virus outbreak. Sci. Rep. 2022;12:15777. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-20076-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondal S., Feirer N., Brockman M., Preston M.A., Teter S.J., Ma D., Goueli S.A., Moorji S., Saul B., Cali J.J. A direct capture method for purification and detection of viral nucleic acid enables epidemiological surveillance of SARS-CoV-2. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;795 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson B. What poo tells us: wastewater surveillance comes of age amid COVID, monkeypox, and polio. BMJ. 2022;378 doi: 10.1136/bmj.o1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemudryi A., Nemudraia A., Wiegand T., Surya K., Buyukyoruk M., Cicha C., Vanderwood K.K., Wilkinson R., Wiedenheft B. Temporal detection and phylogenetic assessment of SARS-CoV-2 in municipal wastewater. Cell Rep. Med. 2020;1 doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2020.100098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds L.J., Gonzalez G., Sala-Comorera L., Martin N.A., Byrne A., Fennema S., Holohan N., Kuntamukkula S.R., Sarwar N., Nolan T.M., Stephens J.H., Whitty M., Bennett C., Luu Q., Morley U., Yandle Z., Dean J., Joyce E., O’Sullivan J.J., Cuddihy J.M., McIntyre A.M., Robinson E.P., Dahly D., Fletcher N.F., Carr M., De Gascun C., Meijer W.G. SARS-CoV-2 variant trends in Ireland: wastewater-based epidemiology and clinical surveillance. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;838 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.155828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruf B.R., Knuf M. The burden of seasonal and pandemic influenza in infants and children. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2014;173:265–276. doi: 10.1007/s00431-013-2023-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz B.W., Innes G.K., Prasek S.M., Betancourt W.Q., Stark E.R., Foster A.R., Abraham A.G., Gerba C.P., Pepper I.L. Enumerating asymptomatic COVID-19 cases and estimating SARS-CoV-2 fecal shedding rates via wastewater-based epidemiology. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;801 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers S.C., Gosnell E., Bryant D., Belmonte S., Self S., McCarter M.S.J., Kennedy K., Norman R.S. Building-level wastewater surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 is associated with transmission and variant trends in a university setting. Environ. Res. 2022;215 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2022.114277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheu S.-M., Tsai C.-F., Yang H.-Y., Pai H.-W., Chen S.C.-C. Comparison of age-specific hospitalization during pandemic and seasonal influenza periods from 2009 to 2012 in Taiwan: a nationwide population-based study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016;16:88. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1438-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SNHD . Southern Nevada Health District; 2022. Influenza surveillance [WWW Document]https://www.southernnevadahealthdistrict.org/news-info/statistics-surveillance-reports/influenza-surveillance/ URL. (accessed 10.13.22) [Google Scholar]

- Tamáš M., Potocarova A., Konecna B., Klucar Ľ., Mackulak T. Wastewater sequencing-an innovative method for variant monitoring of SARS-CoV-2 in populations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022;19:9749. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19159749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari A., Phan N., Tandukar S., Ashoori R., Thakali O., Mousazadesh M., Dehghani M.H., Sherchan S.P. Persistence and occurrence of SARS-CoV-2 in water and wastewater environments: a review of the current literature. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-16919-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vo V., Harrington A., Afzal S., Papp K., Chang C.-L., Baker H., Aguilar P., Buttery E., Picker M.A., Lockett C., Gerrity D., Kan H.-Y., Oh E.C. Identification of a rare SARS-CoV-2 XL hybrid variant in wastewater and the subsequent discovery of two infected individuals in Nevada. Sci. Total Environ. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.160024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vo V., Tillett R.L., Chang C.-L., Gerrity D., Betancourt W.Q., Oh E.C. SARS-CoV-2 variant detection at a university dormitory using wastewater genomic tools. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;805 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vo V., Tillett R.L., Papp K., Shen S., Gu R., Gorzalski A., Siao D., Markland R., Chang C.-L., Baker H., Chen J., Schiller M., Betancourt W.Q., Buttery E., Pandori M., Picker M.A., Gerrity D., Oh E.C. Use of wastewater surveillance for early detection of Alpha and Epsilon SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern and estimation of overall COVID-19 infection burden. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;835 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.155410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe M.K., Duong D., Bakker K.M., Ammerman M., Mortenson L., Hughes B., Arts P., Lauring A.S., Fitzsimmons W.J., Bendall E., Hwang C.E., Martin E.T., White B.J., Boehm A.B., Wigginton K.R. Wastewater-based detection of two influenza outbreaks. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2022;9:687–692. doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.2c00350. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe M.K., Duong D., Hughes B., Chan-Herur V., White B.J., Boehm A.B. 2022. Detection of monkeypox viral DNA in a routine wastewater monitoring program. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zdenkova K., Bartackova J., Cermakova E., Demnerova K., Dostalkova A., Janda V., Jarkovsky J., Lopez Marin M.A., Novakova Z., Rumlova M., Ambrozova J.R., Skodakova K., Swierczkova I., Sykora P., Vejmelkova D., Wanner J., Bartacek J. Monitoring COVID-19 spread in Prague local neighborhoods based on the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater collected throughout the sewer network. Water Res. 2022;216 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2022.118343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Summary statistics for influenza wastewater libraries and alignment to reference influenza A (H3N2) virus segments (NC_007366.1-NC_007373.1).

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.