Abstract

The density functional theory (DFT) method using the functional hybrid (B3LYP) and 6-311G(d,p) basis set was utilized for the geometry optimization with dispersion correction, procedure (GO + DC), for the E and Z chalcone isomers -1-(4-aminophenyl)- 3-(i,j-dichlorophenyl)prop-2-en-1-one, where (i) and (j) represent the positions of the two chlorine atoms [(2,3), (2,4),(2,5),(2,6),(3,4), and (3,5)] abbreviated (i,j)-chalcone, and 4-(x,y-dichloro-8aH-chromen-2-yl)aniline, where (x = 5,6 and y = 6,7,8,8a) abbreviated (x,y)-chromen isomers. The calculations revealed that E chalcones are the most stable and the 4-(x,y-dichloro-8aH-chromen-2-yl) aniline isomers are the least stable. The (3,5) chalcones were the most stable in both E and Z chalcone series. However, the 4-(5,8a-dichloro-8aH-chromen-2-yl) aniline is the most stable in the series. The isomer stability order is the same as in Part 1, in which the geometry optimization calculation was followed by the dispersion correction single point energy calculation (GO/SPDC) procedure. The procedures (GO + DC) and (GO/SPDC) were used to calculate energies of the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest-unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) and related properties. The order of the HOMO–LUMO energy gap (ΔEgap) was chromens <E chalcones <Z chalcones. The lowest ΔEgap was calculated for the (6,8)-chromen, while the highest energy gap was calculated for the Z (2,6)-chalcone, the least planar isomer. Among the E chalcones, the (2,6)-has the highest EHOMO, ELUMO, ΔEgap, hardness, and electronic chemical potential while possessing the lowest Mulliken electronegativity, electrophilicity index, ionization potential, and electron affinity. The (3,5)-isomer behaved oppositely. The Z chalcones have higher ΔEgap than E chalcones but follow the same trend as the E series with regard to the EHOMO. Among the chromens, the (5,8a)-chromen has the highest ΔEgap, electron affinity, Mulliken electronegativity, hardness, and electrophilicity index but has the lowest EHOMO and ELUMO, and electronic chemical potential. (5,6)-Chromen was found to have the highest ELUMO, electronic chemical potential, and lowest electron affinity. The highest EHOMO is acquired by (6,8)-chromen; however, it has the lowest hardness value. The chromen isomers possessed the highest first-order hyperpolarizability due to being more planar and having longer π-conjugation than the other isomers. In contrast, the Z chalcones had the lowest hyperpolarizability. The HOMO and LUMO surfaces revealed intramolecular charge transfer in the E and Z chalcones and chromens. Calculations of the molecular electrostatic potential showed that oxygen was the most negative. The HOMOs, LUMOs, and related properties mentioned above calculated according to the (GO + DC) and (GO/SPDC) procedures are in complete numerical agreement.

1. Introduction

Chalcones (1,3-diaryl-2-propen-1-one) are a class of synthetic organic compounds naturally present in plants and pigments, including fruits, vegetables, tea, spices, and many soy-based food products. Chalcones also act as important intermediates and are involved in the synthesis of bioflavonoids and isoflavonoids.1

Chalcones have recently attracted attention due to the possibility of using them as photonic devices, where they can be used as erasable-memory media and optics for light photoswitching.2 Chalcone derivatives are also considered excellent substances for their second harmonic generation since they have high transmittance of blue light and excellent crystallizability in a noncentrosymmetric structure.2,3 These properties give chalcones excellent nonlinear optical (NLO) properties.3,4 Organic molecular materials with NLO characteristics have recently attracted significant attention due to their potential applications in optoelectronics, including telecommunications, information storage, signal processing, and information storage.5,6 Over the last decade, a large number of studies have investigated the performance of several compounds with donor–acceptor substituents in nonlinear optics by combining their structural and NLO properties. The applications of organic molecules in nonlinear optics depend on the asymmetric polarization produced by the donor and acceptor groups on both sides of the molecular systems. The NLO properties can be significantly increased by increasing the capability of the donor–acceptor substituents linked to the π-conjugated system. In addition, the position of the substituents also plays an important role in improving the NLO properties because the value of the first-order hyperpolarizability, β, which measures the NLO activity, is associated with the intramolecular charge transfer interactions due to the transfer of electrons from the electron-donor substituent group to the electron-acceptor substituent group through the π-conjugated framework.5 Chalcones are one variety of organic molecular material that possess remarkable NLO properties attributed to the extended conjugation and excellent charge transfer from donor–acceptor substituents via the π-conjugated framework in their molecular systems.7−9 Kumar et al.10 have studied the NLO properties of the chalcone derivative (2E)-3-[4-(methylsulfanyl)phenyl]-1-(3-bromophenyl)prop-2-en-1-one. They have predicted that this molecule is an excellent NLO material by calculating its first-order hyperpolarizability, β, which equals 79.035 × 10–30 esu, 212 times greater than urea. Asiri et al.11 have studied the NLO properties of (E)-1-(4-bromophenyl)-3-(4-(dimethylamino)phenyl)prop-2-en-1-one and found that the values of the dipole moment, polarizability, and first-order hyperpolarizability (β) are larger than urea. Singh et al.12 have prepared and investigated the NLO properties of two new chalcones, 3-(4-(benzyloxy)phenyl)-1-(2-hydroxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one (1) and 3-(4-chlorophenyl)-1-(2-hydroxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one (2), using density functional theory (DFT). They calculated the first static hyperpolarizability (β), and they found that these two chalcones have better NLO properties than the standard para-nitro aniline.

Recently, Yousif and Fadhil13 have calculated the relative energies of the geometry-optimized structure of six (i,j) dichloro methoxy chalcone isomers of (E)-3-(i,j-dichlorophenyl)-1-(4-methoxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one without dispersion correction using the DFT (B3LYP) method with the 6-311G(d,p) basis set. Also, they applied single-point energy calculations with a dispersion correction to the optimized geometry. These calculations revealed the following sequence of stability when a single-point energy with dispersion correction was applied after the geometry optimization: (3, 5) > syn (2,4) > syn (2,5) > anti (3,4) > (2,6) > syn (2,3). The geometry optimization without dispersion correction gave the same ordering, except that (2,6) and syn (2,3) exchanged positions.

In this investigation, it was found that the calculations of the NLO properties revealed that all of the isomers possessed large polarizability and β values compared with those of the urea molecule, which was attributed to the presence of donor and acceptor substituent groups and the involvement of π-conjugation in all isomers. In particular, the (E)-3-(2,6-dichlorophenyl)-1-(4-methoxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one isomer possessed the highest β. This was attributed to the one-direction donor (methoxy group)–acceptor (carbonyl group) as opposed to the two donor–acceptor interactions occurring in opposite directions due to the second donor(chlorine)–acceptor (carbonyl group), which was present in the other chalcone isomers.

The highest occupied molecular orbitals (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals (LUMO) are related to the ionization energy and the electron affinity, respectively.14 The HOMO and LUMO are also referred to as the frontier molecular orbitals (FMOs), and the energy gap between these orbitals can be used to indicate the molecular chemical stability and determine the electrical transport properties of the molecules.1 Furthermore, the HOMO and LUMO energy gap can be used to describe the FMO properties of molecules, such as chemical reactivity, kinetic stability, polarizability, chemical hardness, softness, electronegativity, and aromaticity.15,16 Xue et al.17 have analyzed the electronic structure and studied the FMO properties of quinolone chalcones using DFT with the PBE1PBE functional and the 6-31G level basis set. That calculation was performed by finding the excitation energy and plotting the HOMO–LUMO electron densities. Xue et al. have found that the HOMO–LUMO energy gap decreased by increasing conjugation length, enhancing the electronic charge transfer properties.17 Mary et al.18 have also studied the molecular structure of the chalcone derivative (2E)-1-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-3-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one using B3LYP DFT with 6-31G (6D, 7F) as the standard basis set. They have shown that the HOMO–LUMO energy gap can efficiently characterize the chemical reactivity, the kinetic stability, and the charge transfer interactions in the molecules. Panicker et al.19 have investigated the FMO properties of (2E)-3-(3-nitrophenyl)-1-[4-piperidin-1-yl]prop-2-en-1-one by calculating the Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrum using the HF/6-31G(d) (6D, 7F), B3LYP/6-31G(d) (6D, 7F) and B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) (5D, 7F) basis sets. They have applied HOMO and LUMO energy values to find the global reactivity descriptors. Furthermore, they measured the hardness (η = 0.999), chemical potential (μ = −7.026), electronegativity (χ = 7.026), and electrophilicity index (ω = 24.707). Malarkodi et al.20 have analyzed the FMO characteristics of 3′-(1-benzyl-5-methyl-1H-1,2,3-triazole-4-carbonyl)-1′-methyl-4′-phenyl-2H-spiro-[acenaphthylene-1,2′-pyrrolidine]-2-one using DFT (B3LYP) with the 6-311G(d,p) basis set. They have found that this molecule has a small HOMO–LUMO energy gap of −3.4869 eV with large intramolecular charge transfer interactions, and therefore it is classified as a soft, highly polarizable, and reactive molecule. Mary et al.18 have measured the FMO properties of this chalcone and found that it has a negative chemical potential (μ = −3.995 eV) and is thus a chemically stable molecule. Yoshizawa and co-workers21−23 have investigated the HOMO–LUMO energy gap and conductance of closed ring isomers of diarylethenes using DFT. They have found that the energy gap in the diarylethenes is very small as a result of π-conjugation and the resulting significant delocalization of the charge. Therefore, they have implied that these closed-ring isomers usually have significant charge transfer, electron transport, and electrical conductivity, which are attributed to the larger electron delocalization in these closed-ring isomers, 100 times that of the open-ring isomers. George24 has studied the molecular structure and electronic properties of bischromophoric molecules containing electron-donor and electron-acceptor substituents, such as benzene and anthracene linked together by the cyclopentanone units. He has analyzed the HOMO and LUMO electron densities of different geometry-optimized molecular structures and investigated the tendency of the intramolecular charge transfer to increase with increased length of π-electron conjugation and planarity of the molecule. Yousif and Fadhil13 have also found that HOMO orbitals are more likely to cover more regions where the planarity is significant and less likely to cover geometry-constrained sites. HOMO–LUMO energy gap calculations showed that for the E dichloro para methoxy chalcones, the (2,6)-dichloro methoxy chalcone isomer was the least reactive while the (3,5)-dichloro methoxy chalcone isomer was the most reactive and the most thermodynamically stable isomer. These characteristics were attributed to the finding that the (2,6)-dichloro methoxy chalcone isomer has the largest HOMO–LUMO energy gap, while the (3,5)-dichloro methoxy chalcone isomer possessed the smallest HOMO–LUMO energy gap. In the same investigation, the (2,6)-dichloro methoxy chalcone isomer was the hardest, least reactive, and least polarizable isomer among all of the investigated isomers. Conversely, the (3,5)-dichloro methoxy chalcone isomer was the softest, most reactive, and most polarizable isomer relative to the other chalcone isomers.

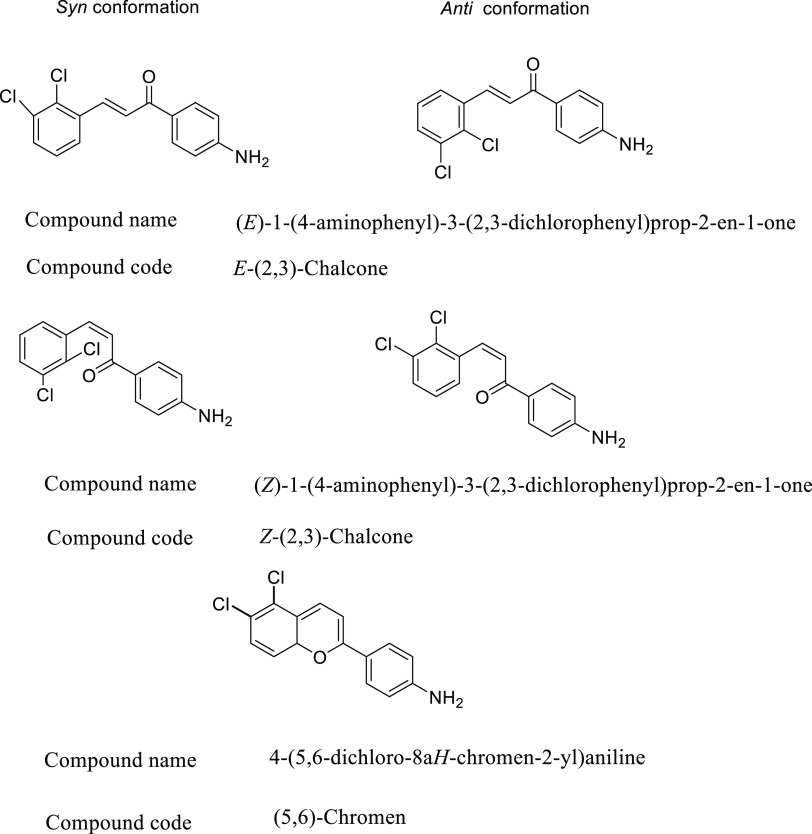

Recently, we investigated25 the structure–stability relationship of chalcone 1-(4-aminophenyl)-3-(i,j-dichlorophenyl)prop-2-en-1-one, where (i) and (j) represent the chlorine atom positions and were abbreviated as E and Z [(2,3), (2,4), (2,5), (2,6), (3,5), and (3,4)] para dichloro amino chalcone isomers. The third investigated series of isomers was 4-(x,y-dichloro-8aH-chromen-2-yl) aniline, where (x) and (y) represent the chlorine atom positions, abbreviated as (x, y)-Chromen. Isomers structures are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

E and Z chalcones and chromens.

The substitutions in the isomers fulfilled the donor–acceptor demands that the para amino group be in conjugation with the carbonyl group. The two chlorines on the other ring represent moderate and same electron-donating groups. Variations in the positions of these two chlorines will result in different electronic responses. The geometry-optimized structures were then determined by single-point energy calculation with a dispersion correction to account for the steric hindrance in the investigated structures. These calculations revealed that the most thermodynamically stable isomer in the E and Z series is the (3,5)-chalcone, and in the chromen series is the (5,8a)-chromen. The least stable isomer of the E, Z chalcones, and chromen series are E (2,3), Z (2,3), and (6,7)-chromen, respectively. Steric and electronic effects were responsible for this ordering. However, the E isomers were the most thermodynamically stable, and the chromen isomers were the least stable.

Due to the aforementioned importance of chalcones, we conducted this study to investigate the stability of E and Z dichloro amino chalcones and their chromen isomers (Figure 1). The energy calculation of the geometry-optimized isomer structure will be achieved using DFT (B3YLP) with a 6-311G(d,p) basis set, accompanied by the dispersion correction method to account for steric hindrance in the isomers. The chalcones and chromen isomers shown in Figure 1 possess a donor, amino group, acceptor groups, carbonyl, and two chlorines, which makes them suitable molecules for a nonlinear optics material. To investigate the isomer efficiency in nonlinear optics, the polarizability, first-order hyperpolarizability and dipole moment will be calculated at the same level of theory.

The isomer’s reactivity is associated with the energy gap of (EHOMO – ELUMO), which efficiently characterizes the molecules’ chemical reactivity, kinetic stability, and intramolecular charge transfer interactions. The energy gap also reflects the extent of π-conjugation and the resulting significant delocalization of the charge in the closed ring isomers and chromene isomers. To examine differences in reactivity among the investigated isomers, we calculated the energies of the HOMO and LUMO orbitals. We used these energies to assess the softness and hardness of the orbitals and thereby understand the variation of ionization potential and electron affinity of the studied isomers. The electron escape tendency, Mulliken electronegativity and hardness of the isomer to reactivity will also be calculated. The final reactivity parameter that will be calculated is the electrophilicity index, which reflects the ability of an electrophile to accommodate an additional electronic charge from its environment (i.e., it is a gauge of the system’s resistance to exchanging electronic charges with its environment). The HOMO–LUMO surfaces of the isomers will also be inspected to investigate the existence of intramolecular charge transfers. The molecular electrostatic potential surfaces will be calculated and used to investigate each isomer’s electrophilic sites.

2. Computation

Gaussian 0926 package together with GaussView 5 were used to perform the calculations and geometry optimization for the starting structure. The geometry optimization for the ground-state structure was carried out applying density functional theory (DFT) as a method, B3LYP (Becke 3 parameter Lee Yang Parr) as a functional and 6-311G(d, p) as a basis set. To check that the geometry optimized ground structures are at true minima, the non-negative frequency was confirmed for each geometry-optimized isomer by computing vibrational frequencies at the same level of theory. Since there was an unacceptable elongation of the C8a-chlorine bond length (Figure 1) in the structure of (5,8a)-chromen isomer, the geometry optimization step for this isomer was run in a different way from the rest of the isomers. This was done by pre-geometry optimizing (5,8a)-chromen using the restricted semiempirical model PM6 and after that the full-geometry optimization was performed by DFT (B3LYP) using 6-311G(d,p) as a basis set. Freezing C8a-Chlorine bond length at 1.76 Å was run using mod redundant keyword (#opt = (tight, modredundant) freq rb3lyp/6-311g(d,p) nosymm geom = connectivity) in Gaussian 09. Molecular electrostatic potential (MEP), nonlinear optics (NLO), HOMO, and LUMO energies were calculated by Gaussian 09. Other reactivity indices were calculated from HOMO and LUMO energies. The calculations were performed by applying geometry optimization with dispersion correction will be referred to as (GO + DC) procedure. The dispersion correction was used to find the impact of steric effect using the keyword Empirical Dispersion = GD3. Also, for the sake of comparison results from Part I,25 in which a different procedure was used to investigate the impact of steric hindrance, the structure was first geometry-optimized without dispersion correction, followed by single-point energy calculation with dispersion correction. This procedure is called (GO/SPDC). The units of the polarizability α0 and first-order hyperpolarizability β0 values from the Gaussian 09 output were originally in atomic units (a.u.), and the units were then converted into electrostatic units(esu) (for α:1 a.u. = 0.1482 × 10–24 esu; for β:1 a.u. = 8.639 × 10–33 esu).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Stability of Isomers

The dichloro E and Z chalcone isomers can exist in two conformations, such as having the chlorine atom number (2) or (3) parallel to the carbonyl group, forming a syn conformation. The other possible conformation is the antiparallel, anti-conformation. Figure 2 presents the (2,3) E and Z chalcones in both conformations and (5,6)-chromen.

Figure 2.

syn, anti (2,3)-Chalcone and (5,6)-Chromen.

Structures, compound names, and isomers coding of E and Z chalcone and chromen isomers are shown in Table S1.

The energy of the optimized structure of each isomer was calculated with a dispersion correction (GO + DC) to account for the steric hindrance of each isomer.

We followed Part I of this investigation in that for the E chalcones, only the most stable conformer of the two possible syn and anti-conformations will be investigated. In Part I, we investigated the stability of each conformer, and the results indicated that the syn (2,3), syn (2,4), and syn (2,5) conformers are more stable than their anti-counterparts. However, the anti (3,4) of the E chalcone was more stable than the syn (3,4) E chalcone. Nevertheless, the Z chalcone series with the anti-conformers are more stable than the syn conformers for (2,3), (2,4), and (2,5), while the syn (3,4) Z chalcone is more stable than its anti-counterpart.

Table 1 gives the electronic energies of the isomers calculated using the procedure (GO + DC). For the sake of comparison, Table 1 presents the electronic energies of the isomers calculated in Part I using geometry optimization. The three-dimensional (3D) geometry-optimized structures for isomers determined according to the (GO + DC) procedure are shown in Table S2.

Table 1. Isomers Calculated Electronic Energies by the Procedures (GO/SPDC)25 and (GO + DC)a.

| electronic

energy (hartree) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| calculation procedure | E | Z | Chromen |

| (2,3) | (2,3) | (5,6) | |

| GO/SPDC | –1628.83764887 | –1628.83243095 | –1628.79548134 |

| GO + DC | –1628.83768588 | –1628.83255784 | –1628.79550639 |

| ΔE (hartree) | 3.701 × 10– 5 | 3.1474 × 10–4 | 2.505 × 10–5 |

| ΔE(kcal/mol) | 23.22 × 10–3 | 194.49 × 10–3 | 15.72 × 10–3 |

| (2,4) | (2,4) | (5,7) | |

| GO/SPDC | –1628.84283318 | –1628.83777013 | –1628.79979535 |

| GO + DC | –1628.84285546 | –1628.83797540 | –1628.79981376 |

| ΔE (hartree) | 2.228 × 10–5 | 2.0527 × 10–4 | 1.841 × 10–5 |

| ΔE(kcal/mol) | 13.98 × 10–3 | 128.81 × 10–3 | 11.55 × 10–3 |

| (2,5) | (2,5) | (5,8) | |

| GO/SPDC | –1628.84285181 | –1628.83721770 | –1628.80075946 |

| GO + DC | –1628.84287352 | –1628.83740182 | –1628.80078969 |

| ΔE (hartree) | 2.171 × 10–5 | 1.8412 × 10–4 | 3.023 × 10–5 |

| ΔE(kcal/mol) | 13.62 × 10–3 | 115.53 × 10–3 | 18.96 × 10–3 |

| (2,6) | (2,6) | (5,8a) | |

| GO/SPDC | –1628.83792693 | –1628.83322724 | –1628.81466782 |

| GO + DC | –1628.83798158 | –1628.83373766 | –1628.81466780 |

| ΔE (hartree) | 5.465 × 10–5 | 5.1042 × 10–4 | 2.0 × 10–8 |

| ΔE(kcal/mol) | 34.29 × 10–3 | 320.28 × 10–3 | 0.0125 × 10–3 |

| (3,4) | (3,4) | (6,7) | |

| GO/SPDC | –1628.84115564 | –1628.83482636 | –1628.79398374 |

| GO + DC | –1628.84118805 | –1628.83492643 | –1628.79401062 |

| ΔE (hartree) | 3.241 × 10–5 | 2.641 × 10–5 | 2.688 × 10–5 |

| ΔE(kcal/mol) | 20.33 × 10–3 | 16.57 × 10–3 | 16.86 × 10–3 |

| (3,5) | (3,5) | (6,8) | |

| GO/SPDC | –1628.84470894 | –1628.83825675 | –1628.79996263 |

| GO + DC | –1628.84472538 | –1628.83836462 | –1628.79999092 |

| ΔE (hartree) | 1.644 × 10–5 | 1.0787 × 10–4 | 2.829 × 10–5 |

| ΔE(kcal/mol) | 10.31 × 10–3 | 67.68 × 10–3 | 17.75 × 10–3 |

ΔE is the difference between the calculated energies according to the two procedures.

The isomer stability order of this investigation is E chalcone > Z chalcone > chromen, which is the same as the ordering obtained from the energy calculations which employed the procedure (GO/SPDC). In Part I of this investigation, the order of the calculated stability of the electronic energies without using dispersion correction of the E dichloro amino chalcone isomers was: (3,5) > syn (2,4) > syn (2,5) > anti (3,4) > (2,6) >syn (2,3). However, on introducing the (GO/SPDC) procedure, the order becomes: (3,5) > syn (2,5) > syn (2,4), anti (3,4) > (2,6) > syn (2,3). The order of the stability of the E chalcones in this investigation which uses (GO + DC) procedure is: (3,5) > syn (2,5) > syn (2,4) > anti (3,4) > (2.6) > syn (2,3). This order of stability is the same as the order given by the previous calculations25 using the procedure (GO/SPDC). In the previous calculations, the syn (2,4) form was more stable than the syn (2,5) form by 0.0001 hartree, which is equal to 1.0422 × 10–22 Calories. This difference is the least among the E chalcone series.

The Z chalcone isomer stability calculated with the (GO + DC) procedure is (3,5) > anti (2,4) > anti (2,5) > syn (3,4) > (2,6) > anti (2,3), which is similar to that obtained from (GO/SPDC), as shown in Table 1. The chromen isomer stability order is (5,8a) > (5,8) > (6,8) > (5,7) > (5,6) > (6,7), which agrees completely with that obtained using (GO/SPDC). The electronic energy calculated with the (GO + DC) procedure reveals more stable structures than that calculated by (GO/SPDC). However, the difference in the calculated energies for each isomer from both procedures is less than 1 kcal/mol, which is very small and can be ignored. Hence, we consider the calculated energies from both procedures for each isomer to be the same; this shows that the procedure (GO/SPDC) is sufficient to obtain the energies of the isomers, and there is no need to use the more time-consuming procedure (GO + DC).

3.2. Frontier Molecular Orbitals Analysis

The energy gap between the HOMO and LUMO molecular orbitals is an important indicator for determining the intramolecular charge transfer because it measures electron conductivity.27 A molecule with a small energy gap is described as a more polarizable molecule with high chemical reactivity and low kinetic stability. Such molecules are also termed soft molecules.28 A molecule with a large HOMO–LUMO energy gap is known as a hard molecule.1,29 According to Koopmans’ theorem,30,31EHOMO is related to the ionization potential (I) of the species, while ELUMO is related to its electron affinity (A). A large energy gap (ΔEgap) between these two orbitals implies resistance to both oxidation and reduction, and low chemical reactivity is one of the defining characteristics of aromaticity. The electronic chemical potential (μ), which measures the “escape tendency” of the electrons in the system,18,32 can be calculated from the electron affinity and ionization energy as

| 1 |

which is the opposite of the absolute Mulliken electronegativity given in eq 2.

| 2 |

The absolute hardness (η) is related to the energy gap by eq 3.32

| 3 |

where I and A are the ionization potential and electron affinity equal to the negative HOMO and LUMO, respectively, according to eqs 4 and 5.33

| 4 |

| 5 |

The electrophilicity index of the molecule is also given by eq 6.3

| 6 |

Changes in the stabilization energy when the system gains an additional electronic charge from the environment can be made using the electrophilicity index parameter. This involves the ability of an electrophile to acquire an additional electronic charge from the environment and also measures the resistance of the system to exchanging electronic charges with its environment.18 Additionally, it accommodates information about electron transfer (chemical potential), stability (hardness), and global chemical reactivity.18 For the title compounds, EHOMO, ELUMO, the energy gap (ΔE = ELUMO – EHOMO), I, A, η, μ, and ω were calculated for the E, Z, and chromen isomers of chalcone, and their values are shown in Tables 2–4.

Table 2. EHOMO, ELUMO, ΔE, I, A, η, μ, and ω for the E Chalcone Isomers Computed by DFT(B3LYP) Using 6-311G(d,p) Basis Set and (GO + DC) Procedure.

| E | EHOMO (au) | ELUMO (au) | ΔE (au) | I | A | η | μ | χ | ω ×10–4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (2,3) | –0.22264 | –0.08534 | 0.13730 | 0.22264 | 0.08534 | 0.06865 | –0.15399 | 0.15399 | 8.1395 |

| (2,4) | –0.22263 | –0.08708 | 0.13555 | 0.22263 | 0.08708 | 0.06778 | –0.15486 | 0.15486 | 8.1262 |

| (2,5) | –0.22272 | –0.08795 | 0.13477 | 0.22272 | 0.08795 | 0.06739 | –0.15534 | 0.15534 | 8.1297 |

| (2,6) | –0.22036 | –0.08075 | 0.13961 | 0.22036 | 0.08075 | 0.06981 | –0.15056 | 0.15056 | 7.9113 |

| (3,4) | –0.22271 | –0.08821 | 0.13450 | 0.22271 | 0.08821 | 0.06725 | –0.15546 | 0.15546 | 8.1264 |

| (3,5) | –0.22399 | –0.09054 | 0.13345 | 0.22399 | 0.09054 | 0.06673 | –0.15727 | 0.15727 | 8.2513 |

Table 4. EHOMO, ELUMO, ΔE, I, A, η, μ and ω for the Chromen Isomers Computed by DFT (B3LYP) Using 6-311G (d,p) Basis Set and (GO + DC) Procedure.

| chromen | EHOMO (au) | ELUMO (au) | ΔE (au) | I | A | η | μ | χ | ω ×10–4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (5,6) | –0.18906 | –0.08065 | 0.10841 | 0.18906 | 0.08065 | 0.05421 | –0.13486 | 0.13486 | 4.9 |

| (5,7) | –0.19390 | –0.08373 | 0.11017 | 0.19390 | 0.08373 | 0.05509 | –0.13882 | 0.13882 | 5.3 |

| (5,8) | –0.19095 | –0.08316 | 0.10779 | 0.19095 | 0.08316 | 0.05390 | –0.13706 | 0.13706 | 5.1 |

| (5,8a) | –0.19880 | –0.08540 | 0.11340 | 0.19880 | 0.08540 | 0.05670 | –0.14210 | 0.14210 | 5.7 |

| (6,7) | –0.18887 | –0.08174 | 0.10713 | 0.18887 | 0.08174 | 0.05357 | –0.13531 | 0.13531 | 4.9 |

| (6,8) | –0.18780 | –0.08198 | 0.10582 | 0.18780 | 0.08198 | 0.05291 | –0.13489 | 0.13489 | 4.8 |

Table 3. EHOMO, ELUMO, ΔE, I, A, η, μ and ω for the Z Chalcone Isomers Computed by DFT(B3LYP) Using 6-311G(d,p) Basis Set and (GO + DC) Procedure.

| Z | EHOMO (au) | ELUMO (au) | ΔE (au) | I | A | H | μ | χ | ω ×10–4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (2,3) | –0.22383 | –0.07705 | 0.14678 | 0.22383 | 0.07705 | 0.07339 | –0.15044 | 0.15044 | 8.3049 |

| (2,4) | –0.22404 | –0.08108 | 0.14296 | 0.22404 | 0.08108 | 0.07148 | –0.15256 | 0.15256 | 8.3183 |

| (2,5) | –0.22392 | –0.08017 | 0.14375 | 0.22392 | 0.08017 | 0.07188 | –0.15205 | 0.15205 | 8.3079 |

| (2,6) | –0.22060 | –0.07252 | 0.14808 | 0.22060 | 0.07252 | 0.07404 | –0.14656 | 0.14656 | 7.9518 |

| (3,4) | –0.22375 | –0.08715 | 0.13660 | 0.22375 | 0.08715 | 0.06830 | –0.15545 | 0.15545 | 8.2522 |

| (3,5) | –0.22475 | –0.08860 | 0.13615 | 0.22475 | 0.08860 | 0.06808 | –0.15668 | 0.15668 | 8.3552 |

The reaction kinetics can be understood by investigating the concept of hard and soft HOMO and LUMO orbitals, which is also useful in comparing isomers.34 The E (2,6)-chalcone has the highest EHOMO and softest HOMO; hence, it has the lowest ionization potentials. It possesses the highest ELUMO and hardest LUMO; hence, it has the lowest electron affinity, as opposed to the E (3,5) isomer, which has the lowest EHOMO, hardest HOMO, and lowest ELUMO; hence, it has the softest LUMO and highest electron affinity. This agrees with the fact that both properties are negative of the EHOMO or ELUMO values, and the EHOMO and ELUMO of the E (2,6)- and the E (3,5)-chalcones represent the extreme of the E chalcone series. A large energy gap between HOMO and LUMO implies resistance to both oxidation and reduction, and low global chemical reactivity is one of the defining characteristics of aromaticity. The global hardness (η) trend for the E chalcone series follows the energy gap trend (2,6) > (2,3) > (2,4) > (2,5) > (3,4) > (3,5). However, the E (3,5)-chalcone behaves contrary to the E (2,6)-chalcone. This highlights that the thermodynamic stability of the E (2,6)-chalcone, which is the lowest in the E series, shows an opposite trend to its global hardness, is the least reactive to oxidation and reduction reactions, and the hardest in the E chalcone series. The E (2,6)-chalcone hardness is related to its ELUMO hardness value. In contrast to the E (2,6)-chalcone, the E (3,5)-chalcone possesses the least hardness value, reflecting its ELUMO, which is the softest among the investigated isomers.

The Mulliken electronegativity (χ) trend in the E chalcone series reveals that the E (3,5)-chalcone has the greatest ability to attract electrons, which agrees with the softness of its LUMO and its large electron affinity. Meanwhile, the E (2,6)-chalcone has the least electron affinity because it has the hardest LUMO. However, the behavior of the electronic chemical potential (μ) is exactly opposite that of the Mulliken electronegativity, as indicated by eqs 1 and 2. Hence, E (2,6)-chalcone possesses the highest tendency to lose electrons. This can be attributed to the highest chemical potential, and the softest HOMO of the E (2,6)-chalcone.

The electrophilicity indexes (ω) of the E chalcones reflect the absolute value of the electronic potential and the global hardness, as indicated by eq 6. The ω of the E (2,6)- and (3,5)-chalcone isomers are reflected in the trend of the absolute values of their electronic chemical potentials. Hence, ω is lowest for the E (2,6)-chalcone (i.e., it has the least tendency to accommodate additional electronic charge), which agrees with its LUMO being the hardest. However, the highest electrophilicity index is for the E (3,5)-chalcone, which reflects its greater LUMO softness among the investigated E chalcones. This trend agrees with the ordering of the Mulliken electronegativity and the electron affinity of the E (2,6)- and (3,5)-chalcone isomers. The other E isomers show minute differences in their ω values, which are between those of the (2,6)- and (3,5)-chalcone isomers. The electrophilicity index seems to be an insensitive function for discriminating among the E (2,4), (2,5), and (3,4) chalcones.

In the E chalcone series under investigation, the observed trends in ΔE, I, A, η, μ, χ, and ω agree with previous observations of the E dichloro methoxy chalcone series.13 This indicates that changing the substituent in the acetophenone ring does not change the trend of these FMO properties. However, the effect of changing the substituent from methoxy to amine as in our current series manifests in the EHOMO and ELUMO values and the energy gap (ΔEHOMO–LUMO). Lower (more negative) HOMO and LUMO energies were observed for E dichloro methoxy chalcones than E dichloro amino chalcones. In contrast, a larger energy gap (ΔEHOMO–LUMO) was observed in the E dichloro methoxy chalcones than in the E dichloro amino chalcones. This difference may be attributed to the greater electronegativity of the oxygen in the methoxy group than that of the nitrogen in the amino substituent group. This indicates that changing the substituent in the acetophenone ring does not change the trend of these FMO properties. However, the effect of changing the substituent manifests in the EHOMO and ELUMO values and the energy gap (ΔEHOMO–LUMO).

The Z chalcones follow the same trend as the E series with regard to the energy gap, global hardness, chemical potential, and electrophilicity index. However, a larger energy gap can be seen in Z chalcones, unlike the E isomers. The lower energy gap in the E chalcones compared to the Z chalcones is attributed to the increased planarity in the E chalcones isomers which enhances effective p-orbitals overlap, in other words, more conjugation and spread of charge delocalization in the π orbitals. In contrast, in the Z isomers, there is a greater degree of nonplanarity that prevents such conjugation, resulting in a larger energy gap. Figure 3 shows the geometry-optimized structures for the E and Z isomers of (2,3)-chalcones with their dihedral angles. Z (2,3)-chalcone possesses the largest dihedral angles and, thus, has the largest instability and less conjugation compared to E (2,3)-chalcone.

Figure 3.

Dihedral angles for the geometry-optimized E and Z (2,3)-chalcones using (GO + DC) procedure.

(5,8a)-chromen has the lowest EHOMO, hardest, highest ionization potential, and highest ELUMO, softest, highest electron affinity. Similarly, the largest energy gap for the chromen isomers can be found in the (5,8a)-isomer, whereas the smallest energy gap is in the (6,8)-isomer. Therefore, (5,8a)-chromen is classed as a hard and strong electron-donor molecule, whereas (6,8)-chromen is a soft and poor electron donor. This is because the dihedral angle of C3–C2–C1–C7 (Figure 1) in the (5,8a)-chromen isomer shown in Table 5 is lower than in the other chromen isomers and is far from 180°. This causes a deviation from planarity in (5,8a)-chromen and results in the largest energy gap because the conjugation is diminished.

Table 5. Computed Dihedral Angles for Chromen, E and Z Chalcone Isomers Using DFT(B3LYP) and 6-311G (d,p) Basis Set Using Geometry-Optimized Structures Given without Parentheses and Dihedral Angles According to the Procedure (GO + DC) between Parentheses.

| chromen | C6–C5–C4–C3 | C3–C2–C1–C7 | C7–C8–C9–O |

|---|---|---|---|

| (5,6) | 4.405 | 172.977 | –11.388 |

| (4.345) | (172.974) | (−11.378) | |

| (5,7) | 4.250 | 172.160 | –12.068 |

| (4.202) | (172.089) | (−12.069) | |

| (5,8) | 3.982 | 172.439 | –13.062 |

| (3.942) | (172.312) | (−12.845) | |

| (5,8a) | 4.647 | 165.689 | –6.115 |

| (4.627) | (165.609) | (−5.155) | |

| (6,7) | 4.634 | 171.672 | –10.889 |

| (4.572) | (171.622) | (−10.832) | |

| (6,8) | 4.209 | 172.112 | –11.999 |

| (4.167) | (172.008) | (−11.802) |

| chalcone | C6–C1–C7–C8 | C7–C8–C9–O | C8–C9–C10–C11 |

|---|---|---|---|

| E (2,3) | 28.298 | 6.741 | 8.492 |

| (31.123) | (7.949) | (10.140) | |

| E (2,4) | 21.367 | 4.172 | 6.903 |

| (24.478) | (5.144) | (8.203) | |

| E (2,5) | 22.940 | 3.360 | 4.609 |

| (25.501) | (3.592) | (4.921) | |

| E (2,6) | –42.656 | –3.423 | 1.269 |

| (−43.988) | (4.017) | (9.411) | |

| E (3,4) | –1.213 | –0.465 | –0.025 |

| (0.216) | (1.835) | (5.107) | |

| E (3,5) | 1.880 | 2.329 | 4.996 |

| (2.433) | (3.432) | (7.605) | |

| Z (2,3) | 40.005 | –40.732 | 169.320 |

| (−46.702) | (47.897) | (−169.505) | |

| Z (2,4) | 32.700 | –36.079 | 168.821 |

| (40.647) | (−44.051) | (168.868) | |

| Z (2,5) | 36.777 | –37.380 | 170.350 |

| (−42.640) | (44.165) | (−169.917) | |

| Z (2,6) | –70.164 | –13.581 | 170.688 |

| (−61.652) | (−27.869) | (170.833) | |

| Z (3,4) | –12.750 | 20.871 | –167.515 |

| (17.540) | (−26.940) | (167.265) | |

| Z (3,5) | 15.644 | –22.884 | 168.575 |

| (23.368) | (−33.578) | (168.325) |

Unlike the Z and E isomers, (5,6)-chromen was found to have the lowest electron affinity among the chromen isomers due to its highest LUMO energy and the hardest LUMO, given that A = −ELUMO (eq 5). This is due to the dihedral angle of C3–C2–C1–C7 being closer to 180°. Therefore, more conjugation occurs (higher planarity), which raises the LUMO energy compared with (5,8a)-chromen, which acquires less conjugation due to being less planar (Table 5) and having more deviation from 180° in the dihedral angle of C3–C2–C1–C7 than (5,6)-chromen. Chromen have the least hardness when compared to E and Z chalcones that agrees with the calculated stability energies of chromens being the least stable compared to chalcones. (5,6)-chromen has the highest chemical potential value because it possesses the highest ELUMO, taking into account the positive relationship between ELUMO and the chemical potential as a consequence of the negative relationship between the electron affinity and the chemical potential, as shown in eq 1. Since the relationship between the chemical potential and the Mulliken electronegativity is opposite (eqs 1 and 2), it is not surprising that (5,6)-chromen has the lowest Mulliken electronegativity. The (5,8a)-chromen has the opposite trend of chemical potential, lowest, and Mulliken electronegativity, highest, compared to (2,3)-chalcone. However, the (5,9)-chromen possesses the highest value of hardness because it has the highest energy gap. Also, the isomer with the highest electrophilicity index is (5,8a) chromen. The highest EHOMO, softest, is acquired by (6,8)-chromen and hence it has the lowest ionization potential, lowest value for hardness, and lowest electrophilicity index. The HOMOs, LUMOs, and related properties mentioned above, calculated according to the (GO + DC) procedure, are in complete numerical agreement with the same properties calculated using the (GO/SPDC) procedure as in Part I of this investigation.

The HOMO and LUMO orbital surfaces of the E and Z chalcone and chromen isomers were also computed and are shown in Figure 4 as an example; the rest of the isomers are shown in Figure S1. In Figure 4, the HOMO orbitals of the E and Z chalcones are mainly allocated around the amino aromatic ring, the vinyl double bond, and the carbonyl group. In contrast, the LUMO orbitals are delocalized over the entire molecule, including the dichlorobenzene ring, the ethylene double bond, the carbonyl group, and the amino aromatic ring. This behavior is exactly like that observed in the E dichloro methoxy chalcones.13 This indicates that the intramolecular charge transfer occurs as a result of the transfer of the electron cloud through the π-conjugated framework from the electron-donor groups (i.e., the amino benzene ring, the vinyl double bond, and the carbonyl group) to the electron-acceptor groups (i.e., the dichloride atoms).24,35

Figure 4.

HOMO and LUMO orbital surfaces of the E and Z (2,3)-chalcones and (5,6)-chromen.

In the chromen isomers (Figure 4), however, the length of the planarity is greater than in the E and Z chalcone isomers due to the multiring system. Thus, the molecule has a higher π-conjugation due to its seven conjugated π-bonds. Consequently, the electron delocalization that enhances the intramolecular charge transfer is greater in the chromene isomers.4,36 As a result, the HOMO and LUMO orbitals are spread over the entire molecule in the chromene isomers, unlike the E and Z chalcone isomers.

The molecular electrostatic potential surfaces (MEP) indicate the overall electrostatic impact at one particular point in the space around a molecule. It is determined using the total distribution of the charge density, involving both the electrons and protons of the molecule.18 The MEP tends to combine these properties with the physical and chemical properties of a given molecule, such as dipole moment, electronegativity, positive and negative partial charges, and chemical reactivity. In addition, the MEP also provides a beneficial overview and methodical insight into the other characteristics of a given molecule, such as the relative polarity.37,38 Also, the electrostatic potential mapping of the electron density isosurface predicts important information, such as the mass, charge density, chemical structure, and chemical reactivity locations. Figure 5 shows the MEP surfaces for the E and Z (2,3)- chalcone and (5,6)-chromen isomers as examples, and the rest of the isomers are shown in Figure S2. Distinct colors represent different values of the electrostatic potential: mainly green, red, and blue. Red represents the most negative electrostatic potential, while the blue regions represent the most positive electrostatic potential. The green areas are regions of zero electrostatic potential. Therefore, the electrostatic potential increases in the order blue > green > yellow > orange > red.39 For the E chalcone isomers, the negative electrostatic potential regions are mainly located around the oxygen atom, the phenyl ring of the para amino, the dichloride atoms, the nitrogen atom, and the ethylene double bond; these are all possible sites for an electrophilic attack. However, the positive regions are localized around the hydrogen atoms, indicating possible locations for nucleophilic attack. The maximum negative potential is on the carbonyl oxygen, while the weakest negative potential for chlorine atoms is on the phenyl ring. Conversely, the maximum positive potential is on the hydrogen atoms of the amino group, the weakest potential on the hydrogen atoms around the phenyl rings. These two cases were found to be much higher for the E (2,6)-chalcone (Figure S2), which has higher maximum negative and positive potentials in the red and blue regions, respectively. In addition, zero potential was found for the second phenyl ring attached to the two chlorine atoms. A similar trend was noticed in the E dichloro methoxy chalcones.13

Figure 5.

MEP surfaces of E and Z (2,3)-chalcones and (5,6)-chromene.

The MEP surface of Z (2,3)-chalcone is shown (Figure 5). The most negative regions surround the carbonyl oxygen atoms (orange color). This differs in the Z (2,6)-chalcone isomer (Figure S2), which has a redder negative potential region located around the oxygen atom and a more negative potential around the carbonyl oxygen. Other negative regions are shown by the yellow-green surrounding the two chlorine atoms, indicating an intermediate potential. The weakest negative regions are indicated by light green around the two phenyl rings, the nitrogen atom, and the double bond. The dark and light blue areas surrounding all of the hydrogen atoms show positive potential regions. The most positive regions with the maximum potential are situated around the two hydrogen atoms of the amino group, while the minimum positive regions are indicated by light blue areas localized around the hydrogen atoms of the two aromatic rings.

The MEP surface of (5,6)-chromen is shown in Figure 5. The surface clearly shows that the areas involving ethereal oxygen are mostly light red because they have the maximum negative potential and are followed by greenish-yellow around the two chlorine atoms, light and dark green at the phenyl ring ethylene double bonds and the nitrogen atom. (5,8a)-chromen (Figure S2) is the exception, as the negative potential appears as a relatively large red region surrounding the oxygen and chlorine atoms due to the repulsion between the two electronegative atoms, chlorine and ethereal oxygen. The MEPs obtained by the (GO/SPDC) method are in full agreement with those obtained from the (GO + DC) method.

3.3. NLO Investigation

Nonlinear optical (NLO) materials are those that induce NLO responses when they are exposed to incident light from the electric field, which in turn tends to alter the optical properties of the material, generating new fields that differ in phase, frequency, amplitude, or other propagation characteristics from the incident fields. The NLO optical response can be used for several functions, such as measuring shifts in the position of the frequency and changes in the structure of a material exposed to light. Thus, it has found important applications in communication, signal processing, and optical interconnections.40

Quantum chemical calculations have been widely used to study and describe the relationships between the electronic structures and the NLO responses in many systems.41

Computational approaches offer an inexpensive way of determining the NLO properties of a molecule by analyzing its potential prior to design, as well as its high-order hyperpolarizability tensor. The static polarizability (α), first-order hyperpolarizability (β), and electric dipole moment (μ) were computed for the molecules of interest using the finite field method DFT(B3LYP) with 6-311G(d,p) as a basis set.40

The energy of a system is a function of the electric field in the presence of an applied field, and β can be described by a 3 × 3 × 3 matrix. According to Kleinman symmetry, the 27 components of this 3D matrix can usually be reduced to only 10 components.42

The components of β are given as the coefficients in the Taylor series expansion of the energy in the presence of an applied external electric field.37 As the applied external electrical field is weak and homogeneous, the expansion is given by

where Eo is the energy of the unperturbed molecules; Fα is the field at the origin; μα, ααβ, and βαβγ are the components of the electric dipole moment, polarizability, and first-order hyperpolarizability, respectively. The mean values for the total static dipole moment (μ), polarizability (α0), and first-order hyperpolarizability (β0) are calculated by the following equations: Dipole moment, μtot = (μx2 + μy2 + μz2)1/2, polarizability, αtot = 1/3(αxx + αyy + αzz), and first-order hyperpolarizability, βtot = (βx2 + βy2 + βz2)1/2, where βx = βxxx + βxyy + βxzz, βy = βyyy + βxxy + βyzz and βz = βzzz + βxxz + βyyz.

The first-order hyperpolarizability plays an important role in determining the NLO properties of the material.10 A large β usually indicates a π-electron transfer from a donor to an acceptor that induces a highly polarized molecule with possible intramolecular charge transfer.40 The length of the π-conjugation and the presence of an asymmetric charge transfer process also increase the value of β.40 The main requirement to increase β is a push–pull feature in the molecule. The push–pull feature is characterized by the existence of a long conjugated π-bond system that accommodates an electron–acceptor group at one end and an electron-donor group at the other end. As a consequence of this geometry, the electrons can be transferred from the donor group to the acceptor group through the conjugated π-bond system; this will generate a polarized molecule, which mediates the internal charge transfer (ICT).36,43

The basic strategy of using electron-donor and electron-acceptor substituents to polarize the π-electron system of organic materials has been successful in developing NLO chromophores possessing large molecular nonlinearity, good thermal stability, and improved solubility and processability.4,6 In addition to the donor–acceptor substituents and π-conjugation, the planarity of the molecule also enhances β.41 To evaluate the β values calculated for the chalcone isomers in this study, they were compared with the standard reference material urea, which has a β value of 0.3728 × 10–30 esu.

In this study, the polarizabilities, α and β, were computed for the most stable conformations of the E and Z chalcones and the chromen isomers shown in Table S1; their values are given in Table 6.

Table 6. Values of the First-Order Hyperpolarizability β and Polarizability α in Electrostatic Units (esu) for E, Z, and Chromen Isomers of Chalcones Computed by DFT(B3LYP) Using 6-311G(d,p) Basis Set Using the (GO + DC) Procedure.

| first-order

hyperpolarizability β esu (×10–30) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| isomer | E chalcone | Z chalcone | isomer | chromen |

| (2,3) | 26.687 | 12.514 | (5,6) | 50.135 |

| (2,4) | 22.916 | 15.047 | (5,7) | 58.274 |

| (2,5) | 33.137 | 20.781 | (5,8) | 55.399 |

| (2,6) | 29.508 | 27.768 | (5,8a) | 54.478 |

| (3,4) | 24.641 | 17.898 | (6,7) | 48.714 |

| (3,5) | 31.099 | 26.446 | (6,8) | 46.866 |

| polarizability

α esu (×10–24) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| isomer | E chalcone | Z chalcone | isomer | chromen |

| (2,3) | 33.4405 | 31.9065 | (5,6) | 36.6025 |

| (2,4) | 34.3343 | 33.0471 | (5,7) | 36.0905 |

| (2,5) | 34.0452 | 32.1948 | (5,8) | 35.6200 |

| (2,6) | 32.6289 | 30.9122 | (5,8a) | 35.5202 |

| (3,4) | 34.6141 | 34.5844 | (6,7) | 36.9978 |

| (3,5) | 34.2144 | 33.7346 | (6,8) | 36.5367 |

| dipole

moment μ (debye) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| isomer | E chalcone | Z chalcone | isomer | chromen |

| (2,3) | 6.7091 | 5.4284 | (5,6) | 6.8657 |

| (2,4) | 6.0526 | 5.6007 | (5,7) | 6.6904 |

| (2,5) | 4.7617 | 5.5320 | (5,8) | 5.0588 |

| (2,6) | 4.5604 | 4.0938 | (5,8a) | 6.5523 |

| (3,4) | 4.6069 | 7.0199 | (6,7) | 7.1097 |

| (3,5) | 5.5352 | 6.6071 | (6,8) | 5.8454 |

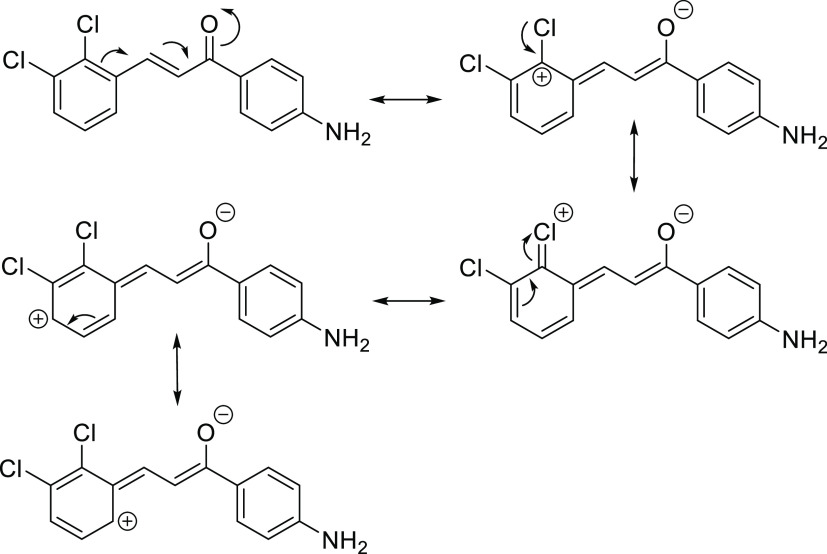

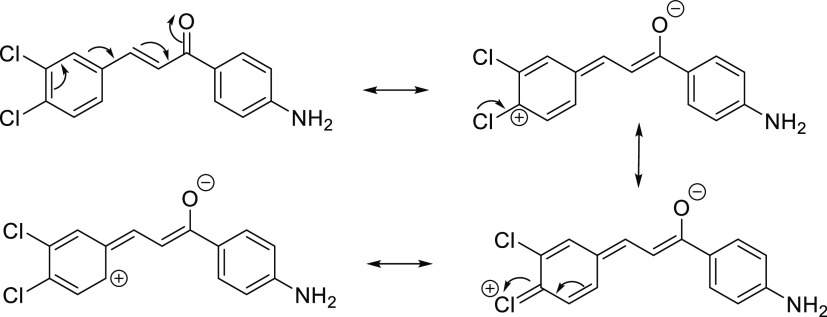

The chromen isomers possess the highest β values compared to the E and Z chalcone isomers. This may be attributed to several characteristics possessed by the chromen isomers. First, the energy gap between the HOMO and LUMO of the chromen isomers is less than that of any chalcone isomer (Tables 2–4). This condition is necessary for achieving easy excitation between HOMO and LUMO. A relatively small energy gap is typically required for a molecule to be polarizable.44 Second, the rigidity, the greater planarity, and the longer π-conjugation of the chromen structure (with seven conjugated bonds) are greater than in any E or Z chalcone isomers. Moreover, there is a donor−π–acceptor arrangement of the substituents at the extreme ends of the chromen with no cross-conjugation, unlike chalcones. This enhances the first-order hyperpolarizability in chromen over that of the chalcones.42,45,46 Despite each chalcone isomer having eight π-bonds, they are not fully conjugated due to the presence of the carbonyl group, which interrupts the conjugation between the two benzene rings of the donor−π–acceptor arrangement of the Cl and NH2 substituents. The order of the β values calculated by (GO + DC) (Table 6) within the chromen isomers is (5,7) > (5,8) > (5,8a) > (5,6) > (6,7) > (6,8). The donor–acceptor approach in the chromen isomers can be rationalized by investigating the resonance structures of the chromen isomers.

The (5,7)-chromen resonance structures are given in Figure 6. Here, the donor is the amine group and the acceptor is the π system of the dichlorophenyl ring. The resonance interaction between the amine group and the π-bond system reveals a negative charge at carbon 6 of the dichlorophenyl ring. This negative charge is stabilized by the electron-withdrawing inductive effect of the two adjacent chlorines because these two chlorines cannot donate π-electrons to carbon 6. Structure (III) of Figure 6 is responsible for the ICT that occurs in the (5,7)-dichloro amino chromen due to the push–pull interaction between the amine group and the π-bond system of the dichlorophenyl ring. The other chromen isomers (5,8), (5,6), (6,7), and (6,8) possess at least one resonance structure that accommodates a negative charge due to resonance on the carbon bonded to the chlorine, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 6.

Resonance structures of (5,7)-chromen.

Figure 7.

Resonance structures of (5,6), (5,8), (6,8), (6,7), and (5,8a)-chromen isomers.

The calculated Mulliken charges reveal a negative charge on carbons 8, 6, 6, and 8 of the (5,8)-, (5,6)-, (6,7)-, and (6,8)- chromens, respectively (Table 7). Carbons 8, 6, 6, 6, and 8 of (5,8)-, (5,6)-, (6,7)-, and (6,8)-chromens acquired negative charges due to resonance as the amine donor is involved in the resonance interaction. The chlorines bonded to these carbons are considered π-resonance donors; hence, they do not favor the negative charge due to resonance that the carbon-bonded chlorines accommodate.

Table 7. Calculated Mulliken Charges of Chromen Isomers Computed by DFT(B3LYP) Using 6-311G(d,p) Basis Set Using (GO + DC) Procedurea.

| Mulliken

charges |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| chromen isomer | C5 | C6 | C7 | C8 | C8a |

| (5,6) | –0.082 | –0.160 | 0.036 | –0.126 | 0.088 |

| (5,7) | –0.194 | 0.098 | –0.216 | –0.022 | 0.077 |

| (5,8) | –0.186 | –0.011 | 0.043 | –0.260 | 0.158 |

| (5,8a) | –0.204 | 0.018 | –0.080 | 0.009 | –0.179 |

| (6,7) | 0.097 | –0.184 | –0.117 | –0.026 | 0.095 |

| (6,8) | 0.103 | –0.282 | 0.148 | –0.261 | 0.165 |

The (5,8a)-chromen, which has the third-highest β value, also develops a negative charge due to resonance at carbons 6 and 8 (Figure 7), but neither of them is bonded to a chlorine. However, these carbons acquired a positive Mulliken charge (Table 7). This confirms that enhanced stabilization of donor–acceptor favors carbon-carrying positive Mulliken charges and resonance-induced negative charges.

Higher β values correlate with the resultant dipole moment (Figure 8) when its starting point lies at the mid-point of the positive charge center, and there it is equidistant from the two chlorine atoms, as in (5,7)-chromen. This resultant dipole moment crosses the (5,7)-chromen molecule, ending close to the negatively charged nitrogen atom, dividing the (5,7) chromen into two halves. However, in the (6,8)-chromen, which has the lowest β value, the dipole moment starting point (Figure 8) is not equidistant from the two chlorine atoms, due to the type of bonding of the carbons, which differs from that in (5,7)-chromen. Consequently, this central positive charge distortion in chromen, the dipole moment ends up at a further distance from the negative end of the nitrogen atom. Moreover, the oxygen and nitrogen atoms in the (5,7)-chromen isomers lie on a straight line that divides the molecule into two halves, although the oxygen and nitrogen atoms are not bonded to each other. To conclude, the (5,7)-chromen isomer was found to have the highest β value, 156 times greater than that of urea. Therefore, the (5,7)-chromen has excellent NLO properties. The chlorine has two opposing electronic effects, as it is an electron donor via resonance and an electron acceptor via the inductive effect. These two different sources of negative charge induce a destabilizing effect that does not support the donor–acceptor interaction. However, in the (5,7)-chromen, negative charges due to resonance are not present on the carbons, which are bonded to chlorines. Moreover, a positive Mulliken charge is acquired on carbon 6 (Table 7) along with a negative charge due to the resonance effect (Figure 6). The negative resonance charge at carbon 6 is stabilized by the electron-withdrawing effect of the chlorines on carbons 5 and 7 (Figure 6). These two chlorines cannot donate π-electrons to carbon 6 in the (5,7)-chromen.

Figure 8.

Position and direction of the dipole moment resultant (blue arrow) for (5,7)-chromen and (6,8)-chromen.

Unlike in (5,7)-chromen, the (6,8)-chromen has the lowest β value in the chromen isomers due to developing negative charges due to resonance at carbons 6 and 8 (Figure 7) without the stabilizing effect of the push–pull interaction. (6,8)-chromen has the weakest push–pull effect and the lowest ICT of the studied chromene isomers.

The first-order hyperpolarizabilities of the E chalcones are shown in Table 6. The ordering of the β values is (2,5) > (3,5) > (2,6) > (2,3) > (3,4) > (2,4). This order reflects the efficiency of the E chalcone isomers in extending the conjugation. The most important dihedral angles, which determine the planarity of the E chalcone isomers, are C6–C1–C7–C8, C7–C8–C9–O, and C8–C9–C10–C11 given in Table 5. The (2,5)-chalcone has the highest β value. The C8–C9–C10–C11 dihedral angle of E (2,5)-chalcone is about 4.921°, close to planarity, allowing the donor para-amine group to interact with the acceptor carbonyl via the resonance interaction of the π-conjugated framework.

Figure 9 (Structures IV and IVA) shows this interaction and the extended π-conjugation generated from it. The other important dihedral angle is C6–C1–C7–C8 (Table 5), which determines the planarity of the dichlorophenyl ring with the vinyl group of the enone moiety. This angle is rotated by 25.501° from planarity. Hence, this angle is not planar as C8–C9–C10–C11, so the π-resonance interaction between the dichlorophenyl ring (donor group) and the carbonyl (acceptor group) is not as effective as that between the amino group and the carbonyl. The resonance interaction between the π-bond system of the dichlorophenyl ring as a donor and the carbonyl as an acceptor can be initiated by one chlorine atom at the ortho position (Figure 9, Structures IVB and IVD). The other chlorine does not participate in this resonance interaction because it is in the meta position (Figure 9, Structures IVC and IVE). This donor–acceptor interaction competes with the more effective donor–acceptor pair (amino–carbonyl) because both the amine and the chlorine donate electrons (charges) to the carbonyl group, which is a requirement for a molecule to have NLO properties.

Figure 9.

Donor (NH2)–acceptor (CO) π-resonance and donor (dichlorophenyl ring)–acceptor (CO) π-resonance interactions in E (2,5)-chalcone.

The second highest β value is calculated for the E (3,5)-chalcone. In this isomer, the π-resonance interaction is favorable between the dichlorophenyl ring (donor group) and the carbonyl (acceptor group) (Figure 10) because the dihedral angles C6–C1–C7–C8 (2.433°) and C8–C9–C10–C11 (7.605°) are almost planar. The amine group π-resonance interaction with the carbonyl is more effective than the π-resonance interaction between the dichlorophenyl ring and the carbonyl group due to the efficiency of the lone pair of the nitrogen in a resonance interaction with the carbonyl. However, the opposing dichlorophenyl–carbonyl π-resonance interaction reduces the push–pull interaction and is responsible for the lower β value of the E (3,5)-chalcone compared to the E (2,5)-chalcone.

Figure 10.

Donor (π-bond)–acceptor (CO) π-resonance interaction in E (3,5)-chalcone.

The E (2,6)-chalcone has the third highest β value. In this isomer, the C6–C1–C7–C8 and C8–C9–C10–C11 dihedral angles are 43.988 and 9.411°, respectively. We expect the main donor–acceptor π-resonance interaction to occur between the amine and carbonyl groups and the π-resonance interaction to occur between the dichlorophenyl ring and the carbonyl group. The E (2,6)-chalcone has two chlorines in the ortho position capable of promoting donor π-resonance interactions with the carbonyl group (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Donor (π-bond)–acceptor (CO) π-resonance interaction in E (2,6)-chalcone.

Although the dihedral angle C6–C1–C7–C8 (43.988°) is not close to planar, it seems capable of promoting a donor π-resonance interaction with the carbonyl group. Consequently, this interaction competes with the amine group π-resonance interaction with the carbonyl and reduces the β value of E (2,6)-chalcone compared with that of E (3,5)-chalcone.

The (2,3)-chalcone isomer also has two competing donor–acceptor interactions (Figure 12), and the dichlorophenyl ring–carbonyl interaction is more effective than the similar interaction in the E (2,6)-chalcone. The C6–C1–C7–C8 dihedral angle in E (2,3)- chalcone is 31.123° and is closer to planar than the similar angle in the E (2,6)-chalcone. The E (3,4)-chalcone is the most planar (Table 5), and the two-competing donor–acceptor interactions in it are more competitive due to its perfect planarity. Figure 13 shows the π-resonance interactions of the carbonyl dichlorophenyl ring and the carbonyl.

Figure 12.

Donor (π-bond)–acceptor (CO) π-resonance interaction in E (2,3)-chalcone.

Figure 13.

Resonance interaction between the dichlorophenyl ring donor and carbonyl acceptor in E (3,4)-chalcone.

The E (2,4)-chalcone has the lowest β value of the studied E dichloro amino chalcone isomers. This isomer also has two opposing donor–acceptor interactions since it has two chlorines at ortho and para positions, which are capable of participating in donor π-resonance interactions with the carbonyl. Also, the C6–C1–C7–C8 dihedral angle (Table 5) permits such interactions, which compete with the donor amine–acceptor carbonyl and reduce the push–pull interaction (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Resonance interaction between the dichlorophenyl ring donor and the carbonyl acceptor in E (2,4)-chalcone.

Z dichloro amino chalcone isomers have lower β values than E chalcone isomers. This is mainly attributed to their lack of planarity: the three important dihedral angles discussed for the E chalcones are greater in the Z chalcones (Table 5). Also, Figure 3 and Table S2 illustrate the geometry of the Z chalcone and show the bent shape of the molecule and the nonplanarity in the structure of Z chalcones. This nonplanarity deprives the Z chalcones of the extended π-conjugation conditions found in the E isomers. The twist angles between the two aromatic rings in the Z isomers reduce their planarity and consequently the length of the conjugation present in the E chalcone isomers. Hence, the donor–acceptor interaction that requires planarity and a long π-conjugation area is missing in the Z chalcone isomers, hindering the charge transfer.

The magnitudes of the energy gaps (Tables 2–4) in the Z chalcone isomers are greater than in the E chalcone isomers. The chromen isomers have the lowest energy gaps and, thus, higher α and β (Table 6) than the E and Z chalcones isomers. This phenomenon is mainly attributed to the more extensive conjugation in the chromen isomers. E isomers also have lower energy gaps and higher α and β than Z isomers due to the greater conjugation and planarity in their molecules.

4. Conclusions

The application of the (GO + DC) procedure revealed the following: The E chalcone isomers are the most thermodynamically stable while the chromens are the least stable. The stability order of the E and Z chalcones in this investigation is: (3,5) > syn (2,5) > syn (2,4) > anti (3,4) > (2,6) > syn (2,3). The stability order of the chromen isomers is (5,8a) > (5,8) > (6,8) > (5,7) > (5,6) > (6,7). The E (2,6) and (3,5)-chalcones behaved oppositely in their calculated EHOMO and ELUMO and other FMO properties that are related to the EHOMO and ELUMO. The E (2,6) has the highest EHOMO and ELUMO values. The HOMO–LUMO energy gap, order for the E and Z chalcones is (2,6) > (2,3) > (2,4) > (2,5) > (3,4) > (3,5). The Z dichloro amino chalcones follow the same order of trends of E chalcones. The chromen isomers possessed the smallest energy gaps compared to the E and Z chalcone isomers but follow the same order as in E chalcones. The planarity of the E chalcones and chromens isomers contributes the most to reducing the energy gap compared to the Z chalcones.

Inspecting the surfaces of the HOMO and LUMO of the E and Z chalcones reveals an intramolecular charge transfer. The chromen isomers possessed longer conjugation and more planarity than the E and Z chalcones; hence, they are better candidates for ICT. MEP predicts the oxygen is the most prone to electrophilic attacks.

Chromens have the highest dipole moment, α, and β. The Z chalcones have the lowest dipole moment, α, and β. The higher β for chromens is attributed to the lower energy gap of HOMO–LUMO, better planarity, and longer π-conjugation with donor–acceptor interactions with no cross-conjugation compared to the other chalcone isomers. As in the (5,7)-chromen, the stabilization of the ICT increases the β values. Hence, the chromen isomers are good nominees for materials with NLO properties. The resonance structures and Mulliken charges are used to rationalize the variation of β values among the investigated isomers.

In E chalcones, the isomer with the greatest electron push–pull interaction in one direction, E (2,5)-chalcone, has the highest β value. However, if the E chalcone isomer geometry prefers two opposing electron push–pull interactions as in the E (2,4)-chalcone, this isomer will have the lowest β value. The lost planarity of the chalcones results in lower β values. The electronic energy calculated by (GO + DC) and (GO/SPDC) procedures are similar and we suggest doing (GO/SPDC) to save calculation time. The results of other properties calculated by both procedures are the same.

Acknowledgments

There is no funding to cover this research.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c07148.

Structures and their names; 3D structures with geometry parameters; HOMO–LUMO orbitals surfaces; and MEP surfaces of isomers (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Abbas A.; Gökce H.; Bahçeli S.; Naseer M. M. Spectroscopic (FT-IR, Raman, NMR and UV-Vis.) and Quantum Chemical Investigations of (E)-3-[4-(Pentyloxy)phenyl]-1-Phenylprop-2-En-1-One. J. Mol. Struct. 2014, 1075, 352–364. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2014.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xue Y.; Liu Y.; Zhang L.; Wang H.; Luo Q.; Chen R.; Liu Y.; Li Y. Antioxidant and Spectral Properties of Chalcones and Analogous Aurones: Theoretical Insights. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2018, 119, e25808 10.1002/qua.25808. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lvov A. G.; Herder M.; Grubert L.; Hecht S.; Shirinian V. Z. Photocontrollable Modulation of Frontier Molecular Orbital Energy Levels of Cyclopentenone-Based Diarylethenes. J. Phys. Chem. A 2021, 125, 3681–3688. 10.1021/acs.jpca.1c01836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal A.; Kakkar R. A theoretical assessment of the structural and electronic features of some retrochalcones. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2021, 121, e26797 10.1002/qua.26797. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clara T. H.; Christian P. J.; Reuben J. D.; Vishwanathan V. Structural Elucidation, Growth and Characterization of (E)-2-(4-dimethylamino) benzylidine-3, 4-dihyronapthalen-1(2H) -one Single Crystal for Nonlinear Optical Applications. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1261, 132942 10.1016/j.molstruc.2022.132942. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rajesh K.; Karthick T.; Srivastava A.; Gangopadhyay D.; Parol V.; Tandon P.; Gupta A.; Kumar A.; Subrahmanya K. B. Spectroscopic and quantum chemical study on a non-linear optical material 4-[(1E)-3-(5-chlorothiophen-2-yl)-3-oxoprop-1-en-1-yl] phenyl4-methylbenz ene-1-sulfonate. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1248, 131540 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.131540. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nazar M. F.; Badshah A.; Mahmood A.; Zafar M. N.; Janjua M. R. S. A.; Raza M. A.; Hussain R. Synthesis, Spectroscopic Characterization, and Computed Optical Analysis of Green Fluorescent Cyclohexenone Derivatives. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2016, 29, 152–160. 10.1002/poc.3512. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lansbergen B.; Meister C. S.; McLeod M. C. Unexpected rearrangements and a novel synthesis of 1,1-dichloro-1-alkenones from 1,1,1-trifluoroalkanones with aluminium trichloride. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2021, 17, 404–409. 10.3762/bjoc.17.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanigaimani K.; Arshad S.; Khalib N. C.; Razak I. A.; Arunagiri C.; Subashini A.; Sulaiman F. S.; Hashim S. N.; Ooi L. K. A new chalcone structure of (E)-1-(4-Bromophenyl)-3-(napthalen-2-yl)prop-2-en-1-one:Synthesis,structural characteriz ations,quantum chemical investigations and biological evaluations. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2015, 149, 90–102. 10.1016/j.saa.2015.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A.; Kumar R.; Gupta A.; Tandon P.; D’silva D. E. Molecular structure, nonlinear optical studies and spectroscopic analysis of chalcone derivative (2E)-3-[4-(methylsulfanyl) phenyl]-1-(3-bromophenyl) prop-2-en-1-one by DFT calculations. J. Mol. Struct. 2017, 1150, 166–178. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2017.08.072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asiri A. M.; Karabacak M.; Sakthivel S.; Al-youbi A. O.; Muthu S.; Hamed S. A.; Renuga S.; Alaganesan T. Synthesis, Molecular Structure, Spectral Investigation on(E)-1-(4-Bromophenyl)-3-(4-(Dimethylamino)phenyl)prop-2-En-1-One. J. Mol. Struct. 2016, 1103, 145–155. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2015.08.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A. K.; Saxena G.; Prasad R.; Kumar A. Synthesis, characterization and calculated non-linear optical properties of two new chalcones. J. Mol. Struct. 2012, 1017, 26–31. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2012.02.070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yousif A. A.; Fadhil G. F. DFT of Para Methoxy Dichlorochalcone Isomers. Investigation of Structure, Conformation, FMO, Charge, and NLO Properties. Chem. Data Collect. 2021, 31, 100618 10.1016/j.cdc.2020.100618. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yakalı G.; Biçer A.; Eke C.; Cin G. T. Solid State Structural Investigations of the Bis(chalcone) Compound with Single Crystal X-Ray Crystallography, DFT, Gamma-Ray Spectroscopy and Chemical Spectroscopy Methods. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2018, 145, 89–96. 10.1016/j.radphyschem.2017.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fukui K. Role of Frontier Orbitals in Chemical Reactions. Science 1982, 218, 747–754. 10.1126/science.218.4574.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson R. G. Absolute electronegativity and hardness correlated with molecular orbital theory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1986, 83, 8440–8441. 10.1073/pnas.83.22.8440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue Y.; Liu Y.; An L.; Zhang L.; Yuan Y.; Mou J.; Liu L.; Zheng Y. Electronic Structures and Spectra of Quinoline Chalcones: DFT and TDDFT-PCM Investigation. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2011, 965, 146–153. 10.1016/j.comptc.2011.01.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mary Y. S.; Panicker C. Y.; Anto P. L.; Sapnakumari M.; Narayana B.; Sarojini B. K. Molecular Structure, FT-IR, NBO, HOMO and LUMO, MEP and First Order Hyperpolarizability of (2E)-1-(2,4-Dichlorophenyl)-3-(3,4,5-Trimethoxyphenyl) Prop-2-En-1-One by HF and Density Functional Methods. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2015, 135, 81–92. 10.1016/j.saa.2014.06.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panicker C. Y.; Varghese H. T.; Nayak P. S.; Narayana B.; Sarojini B. K.; Fun H. K.; War J. A.; Srivastava S. K.; Van Alsenoy C. Infrared Spectrum, NBO, HOMO-LUMO, MEP and Molecular Docking Studies (2E)-3-(3-Nitrophenyl)-1-[4-Piperidin-1-Yl]prop-2-En-1-One. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2015, 148, 18–28. 10.1016/j.saa.2015.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malarkodi J. H.; Murugavel S.; Ezhilarasi J. R.; Dinesh M.; Ponnuswamy A. Structure Investigation, Spectral Characterization, Electronic Properties, and Antimicrobial and Molecular Docking Studies of 3′-(1-Benzyl-5-Methyl-1H-1,2,3-Triazole-4-Carbonyl)-1′-Methyl-4′-Phenyl-2H-Spiro[acen aphth ylene-1,2′-Pyrrolidine]-2-One. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2019, 66, 205–217. 10.1002/jccs.201800128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo M.; Tada T.; Yoshizawa K. A theoretical measurement of the quantum transport through an optical molecular switch. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2005, 412, 55–59. 10.1016/j.cplett.2005.05.126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Staykov A.; Nozaki D.; Yoshizawa K. J. Photoswitching of conductivity through a diarylperfluorocyclopentene nanowire. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 3517–3521. 10.1021/jp067612b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji Y.; Staykov A.; Yoshizawa K. Orbital Control of the Conductance Photoswitching in Diarylethene. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 21477–21483. 10.1021/jp905663r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- George G.Photochemical and Photophysical Studies of a Few Bischromophoric Systems. Ph.D. Thesis; Cochin University of Science and Technology: Cochin-22, Kerala, India, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein H. A.; Fadhil G. F. Theoretical Investigation of Para Amino-Dichloro Chalcone Isomers, Part I: A DFT Structure - Stability Study. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2020, 4073, e4073 10.1002/poc.4073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch J. M.; Trucks W. G.; Schlegel B. H.; Scuseria E. G.; Robb A. M.; Cheeseman R. J.; Scalmani G.; Barone V.; Mennucci B.; Petersson A. G.; Nakatsuji H.; Caricato M.; Li X.; Hratchian P. H.; Izmaylov F. A.; Bloino J.; Zheng G.; Sonnenberg L. J.; Hada M.; Ehara M.; Toyota K.; Fukuda R.; Hasegawa J.; Ishida M.; Nakajima T.; Honda Y.; Kitao O.; Nakai H.; Vreven T.; Montgomery A. J. Jr.; Peralta E. J.; Ogliaro F.; Bearpark M.; Heyd J. J.; Brothers E.; Kudin N. K.; Staroverov N. V.; Kobayashi R.; Normand J.; Raghavachari K.; Rendell A.; Burant C. J.; Iyengar S. S.; Tomasi J.; Cossi M.; Rega N.; Millam M. J.; Klene M.; Knox E. J.; Cross B. J.; Bakken V.; Adamo C.; Jaramillo J.; Gomperts R.; Stratmann E. R.; Yazyev O.; Austin J. A.; Cammi R.; Pomelli C.; Ochterski W. J.; Martin L. R.; Morokuma K.; Zakrzewski G. V.; Voth A. G.; Salvador P.; Dannenberg J. J.; Dapprich S.; Daniels D. A.; Farkas Ö.; Foresman B. J.; Ortiz V. J.; Cioslowski J.; Fox J. D.. Gaussian 09, Revision D.01; Gaussian, Inc: Wallingford CT, 2013.

- Sudha S.; Sundaraganesan N.; Vanchinathan K.; Muthu K.; Meenakshisundaram S. Spectroscopic (FTIR, FT-Raman, NMR and UV) and Molecular Structure Investigations of 1,5-Diphenylpenta-1,4-Dien-3-One: A Combined Experimental and Theoretical Study. J. Mol. Struct. 2012, 1030, 191–203. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2012.04.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Powell B. J.; Baruah T.; Bernstein N.; Brake K.; McKenzie H. R.; Meredith P.; Pederson R. M. A first-principles density-functional calculation of the electronic and vibrational structure of the key melaninmonomers. J. Chem. Phys. 2004, 120, 8608–8615. 10.1063/1.1690758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Zhang Y.; Ni H.; Meng N.; Ma K.; Zhao J.; Zhu D. Experimental and DFT Studies on the Vibrational and Electronic Spectra of 9-P-Tolyl-9H-Carbazole-3-Carbaldehyde. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2015, 135, 296–306. 10.1016/j.saa.2014.06.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopmans T. Über die Zuordnung von Wellenfunktionen und Eigenwerten zu den Einzelnen Elektronen EinesAtoms. Physica 1993, 1, 104–113. 10.1016/S0031-8914(34)90011-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carrol A. F.Perspectives On Structure and Mechanism in Organic Chemistry, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, 2010; Vol. 26, pp 48–188. [Google Scholar]

- Hirao K.; Bae H.-S.; Song J.-W.; Chan B. Vertical ionization potential benchmarks from Koopmans prediction of Kohn–Sham theory with long-range corrected (LC) functional. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2022, 34, 194001 10.1088/1361-648X/ac54e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar C. S. C.; Quah C. K.; Balachandran V.; Fun H.-K.; Asiri A. M.; Chandraju S.; Karabacak M. Synthesis, Single Crystal Structure, Spectroscopic Characterization and Molecular Properties of (2E)-3-(2,6-Dichlorophenyl)-1-(3,4-Dimethoxyphenyl)prop-2-En-1-One. J. Mol. Struct. 2016, 1116, 135–145. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2016.02.089. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parr R. G.; Szentpaly V. L.; Liu S. Electrophilicity Index. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 1922–1924. 10.1021/ja983494x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming I.Molecular Orbitals and Organic Chemical Reactions; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, 2010; pp 128–134. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham J. P.; Sajan D.; Shettigar V.; Dharmaprakash S. M.; Němec I.; Hubert Joe I.; Jayakumar V. S. Efficient π-Electron Conjugated Push-Pull Nonlinear Optical Chromophore 1-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-3-(3,4-Dimethoxyphenyl)-2-Propen-1-One:A Vibrat ional Spectral Study. J. Mol. Struct. 2009, 917, 27–36. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2008.06.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nalwa S. H.; Miyata S.. Nonlinear Optics of Organic Molecules and Polymers, 1st ed.; CRC Press: London, 1996; p 490. [Google Scholar]

- Chidangil S.; Shukla M. K.; Mishra P. C. A Molecular Electrostatic Potential Mapping Study of Some Fluoroquinolone Anti-Bacterial Agents. J. Mol. Med. 1998, 4, 250–258. 10.1007/s008940050082. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luque F.; López J.; Orozco M. Perspective on “Electrostatic interactions of a solute with a continuum. A direct utilization of ab initio molecular potentials for the prevision of solvent effects”. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2000, 103, 343–345. 10.1007/s002149900013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bukhari N. S.; Butt M. A.; Amjad M. W.; Ahmad W.; Shah H. V.; Trivedi R. A. Synthesis and evaluation of chalcone analogues based pyrimidines as angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2013, 16, 1368–1372. 10.3923/pjbs.2013.1368.1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar C. S. C.; Govindarasu K.; Fun H.; Kavitha E.; Chandraju S.; Quah C. K.Syn thesis,Molecular Structure,Spectroscopic Characterizat ion and Quantum Chemical Calculation Studies of (2E) -1-(5-Chlorothiophen-. J. Mol. Struct. 2015, 1085, 63–77. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2014.12.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burland D. M.; Miller D. R.; Walsh A. C. Second-order nonlinearity in poled-polymersystems. Chem. Rev. 1994, 94, 31–75. 10.1021/cr00025a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A. D. Nonlinear Dielectric Polarization in Optical Media. Phys. Rev. 1962, 126, 1977–1979. 10.1103/PhysRev.126.1977. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bosshard C.; Sutter K.; Prêtre Ph.; Flörsheimer M.; Kaatz P.; Günter P.; Hulliger J.. Organic Nonlinear Optical Materials, Advances in Nonlinear Optics, 1st ed.; CRC Press: London, 1995; p 14. [Google Scholar]

- Nazar M. F.; Badshah A.; Mahmood A.; Zafar N. M.; Janjua A. S. R. M.; Raza A. M.; Hussain R. Synthesis, Spectroscopic Characterization, and Computed Optical A nalysis of Green Fluorescent Cyclohexenone Derivatives. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2016, 29, 152–160. 10.1002/poc.3512. [DOI] [Google Scholar]