Abstract

Until recently, psychotherapies, including exposure and response prevention (ERP) for obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), have primarily been delivered in-person. The COVID-19 pandemic required OCD providers delivering ERP to quickly transition to telehealth services. While evidence supports telehealth ERP delivery, limited research has examined OCD provider perceptions about patient characteristics that are most appropriate for this modality, as well as provider abilities to identify and address factors interfering with effective telehealth ERP. In the present study, OCD therapists (N = 113) rated the feasibility of delivering telehealth ERP relative to in-person for different (1) patient age-groups, (2) levels of OCD severity, and (3) provider ability to identify and address factors interfering with ERP during in-person and telehealth ERP (e.g., cognitive avoidance, reassurance seeking, etc.). Providers reported significantly greater feasibility of delivering telehealth ERP to individuals ages 13-to-65-years relative to other age groups assessed. Greater perceived feasibility for telehealth relative to in-person ERP was reported for lower versus higher symptom severity levels. Lastly, providers felt better able to identify and address problematic factors in-person. These findings suggest that providers should practice appropriate caution when offering telehealth ERP for certain patients with OCD. Future research may examine how to address these potential limitations of telehealth ERP delivery.

Keywords: OCD, Telehealth, Exposure and response prevention, Treatment, Psychotherapy

1. Introduction

Psychological services have historically been provided using in-person psychotherapy, where one mental health provider works with a patient to help address presenting concerns (Fernandez et al., 2021). This holds true for treatment across specific psychopathologies, including obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), a condition characterized by recurring distressing, unwanted, and intrusive thoughts that motivate compulsive behaviors/avoidance to mitigate obsessional distress (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Exposure and response prevention (ERP) is the gold-standard psychotherapy for OCD with well-established treatment efficacy (Ferrando and Selai, 2021; McGuire et al., 2015; Olatunji et al., 2013; Reid et al., 2021). Through the course of ERP, patients are encouraged to systematically confront fear-inducing stimuli while actively resisting compulsive behaviors. Through graded exposure, individuals learn that feared stimuli are unlikely to result in adverse outcomes, and that the anxiety reduces with exposure, and is within their ability to cope (McKay et al., 2015). Providers and patients work collaboratively to address areas of concern, improve symptom management, and resume day-to-day activities previously impacted by OCD symptoms. Largely, providers relied on inperson ERP delivery, until 2020.

The COVID-19 pandemic stemming from the rapid spread of the novel SARS-CoV-2 virus had wide-reaching implications and disrupted healthcare providers’ ability to delivery interventions for their patients through traditional means, including mental health providers (Sasangohar et al., 2020). Compared to other types of specialty care, such as surgery centers where procedures were temporarily suspended (Boyarsky et al., 2020; Iacobucci, 2020), mental health providers were able to transition to telehealth relatively smoothly and continued providing treatment with patient-provider video connections. Existing literature provided evidence for the effective delivery of psychotherapy through this medium (Elford et al., 2000; Rees and Maclaine, 2015; Storch et al., 2011; Tuerk et al., 2018) and many providers were already offering some degree of telehealth treatment prior to the pandemic. Indeed, recent meta-analytic data provides strong evidence for cognitive-behavioral treatment (CBT) using telehealth, with this modality resulting in significant symptom decrease pre-to-post treatment (g = 0.99) as well as compared to wait-list control (g = 0.77), and near-equal effectiveness compared to in-person therapy (g = 0.01) (Fernandez et al., 2021). Mental health providers were clearly well-equipped to continue providing indicated services, albeit through a different medium than what has traditionally been used.

Treatment research has consistently supported the use of telehealth ERP for both short-term and sustained symptom reduction in both children and adults with OCD (Comer et al., 2017; Fletcher et al., 2021; Goetter et al., 2014; Storch et al., 2011; Vogel et al., 2014; Wootton et al., 2013; Wootton, 2016). While many OCD providers were required to transition quickly to telehealth ERP delivery, there are benefits of this transition. Providers can now assist with in-home exposures without added costs, time, or travel, and patients are less likely to cancel due to the ease of attending telehealth appointments. Additionally, more intensive interventions, such as partial hospitalization and intensive-outpatient programs that would typically require patients to be away from home for extended periods, can now be conducted within the home (Pinciotti et al., 2022; Sequeira et al., 2021).

While it is possible that OCD providers and patients may return to the pre-pandemic norm of relying largely on in-person ERP, the benefits of telehealth services make this increasingly unlikely. Early research in this area suggests a hybrid approach of both in-person and telehealth will likely become the norm, as providers identify this mixed-approach to be optimal relative to relying solely on one modality (Shklarski et al., 2021a; Shklarski et al., 2021b). With telehealth likely here to stay, there are important considerations for those delivering ERP to patients with OCD that have been unexplored to date. Specifically, providers will need to consider whether telehealth ERP delivery is clinically indicated for all patients, and what individual differences may make telehealth delivery more or less appropriate.

To address these considerations, the present study was designed to assess provider perceptions of telehealth ERP delivery compared to in-person ERP delivery. More clearly, we sought to assess the perceived feasibility of delivering telehealth relative to in-person ERP for patients with OCD at different ages and different levels of OCD symptom severity. We additionally sought to assess provider perceived ability to identify and address different factors that often arise during ERP that adversely impact the course and pace of treatment. With these aims in mind, we predicted that (1) providers would report greater feasibility for telehealth ERP delivery for teenage and adult patients relative to the rest of the sample, but not for younger (< 13yo) and older patients (65+yo) when compared to the rest of the sample; (2) providers would report greater feasibility for telehealth ERP for lower versus higher levels of OCD symptom severity; and (3) that providers would report greater ability to identify and address ERP interfering factors during in-person ERP compared to telehealth ERP.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants consisted of mental health professionals currently working in the United States or Canada who provide ERP for adults and/or children/adolescents with OCD. A total of 156 participants consented and completed at least a portion of the survey; 43 (28%) participants were identified as non-responders, failing to complete all the self-report items assessed in the current study. These participants were excluded from analysis to ensure data integrity, as their responses to certain items but not others caused concern about the validity of responses to items completed. One notable exception was made, where participants who self-identified exclusively as treating children and did not complete questions specific to adult patients (e.g., treatment interference due to alcohol use) were kept in the dataset for analysis; all other non-complete responders were excluded from analysis. The final sample was comprised of 113 individuals. Relevant demographic data are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic information of the study sample.

| M (SD) | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age | 40.9 (12.27) | 23 | 72 |

| Number of years practicing | 12.8 (11.13) | < 1 | 44 |

| N (%) | |||

| Gender | |||

| Female | 81 (72%) | ||

| Male | 31 (27%) | ||

| Non-binary | 1 (1%) | ||

| Race | |||

| White | 102 (90%) | ||

| Black/African American | 1 (1%) | ||

| Asian | 5 (4%) | ||

| More than one | 3 (3%) | ||

| Prefer not to report | 2 (2%) | ||

| Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 104 (92%) | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 6 (5%) | ||

| Prefer not to report | 3 (3%) | ||

| Training Status | |||

| Non-trainee | 95 (84%) | ||

| Trainee, student, post-doctoral fellow | 18 (16%) | ||

| Provider Type | |||

| Psychologist | 79 (70%) | ||

| Psychotherapist | 31 (27%) | ||

| Psychiatrist | 2 (2%) | ||

| Prefer not to report | 1 (1%) | ||

Note. Psychotherapist refers to social workers, counselors, and marriage/family therapists.

2.2. Procedure

Potential participants were identified using public access listservs (Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies, and International OCD Foundation), supplemented by colleagues of the authors. Individuals were contacted via email with a link to an anonymous online Qualtrics survey and were encouraged to forward the survey to other providers who treat patients with OCD using ERP. Participation was voluntary and all participants provided consent prior to completing the questionnaire. No compensation was provided for this study. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Subjects Research at the Baylor College of Medicine. Data were collected from June 2021 through August 2021.

2.3. Measure

All items used were developed by the authors and reviewed by outside collaborators unaffiliated with this project who provided feedback. Participants were asked first to report relevant demographic information, years of clinical practice, level of clinical training (trainee versus licensed practitioner), and type of provider (e.g., psychologist, mental health counselor, etc.).

To assess the feasibility of delivering telehealth ERP compared to in-person ERP for different age ranges, participants were presented with and asked to respond to the following prompt: “Rate your perception of the feasibility of implementing telehealth ERP when treating clients with OCD compared to face-to-face appointments.” Participants were asked to respond to the prompt for the following age ranges: < 8-years old; 8-to-12 years old; 13-to-17 years old; 18-to-65 years old; and > 65 years old. Responses were recorded using a 0 to 4 scale (much less feasible; less feasible; equally as feasible, more feasible; much more feasible). A similar prompt was used to assess the feasibility of delivering ERP via telehealth relative to in-person for different levels of symptoms severity. Symptom severity levels corresponded with scores on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS; Goodman et al., 1989) and the following were assessed: Mild-to-Moderate (Y-BOCS score = 16–23); Moderate-to-Severe (Y-BOCS = 24–32); and Severe (Y-BOCS ≥ 33). Responses were recorded using the same 0 (much less feasible) to 4 (much more feasible) scale.

After completing feasibility ratings, participants were asked about their ability to identify and address factors that often interfere with and adversely impact the effectiveness of ERP delivery. These factors were decided after seeking input from experienced ERP clinicians and are consistent with what has been reported in existing research (Abramowitz et al., 2002; Davis et al., 2020; Himle et al., 2006; Wheaton et al., 2018). Participants were presented with the following prompt: “As a provider, I am able to identify and address the following…” This prompt was provided for both in-person and telehealth services, and participants were asked to respond for the following factors: cognitive avoidance and distraction during exposure; self-soothing, fidgeting or behavioral distractions; self-assurance seeking behaviors; reassurance seeking from others; environmental distractions; alcohol and/or substance use; non-verbal communication; difficulty delivering psychoeducational materials; limited patient insight into severity; and limited between-session exposure practice. Responses were recorded using a 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree) scale..

2.4. Analysis plan

Firstly, the data were visually examined to ensure normal distributions. To assess provider perceived feasibility of administering ERP via telehealth relative to in-person at different patient age-ranges, a repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted with age as an independent variable with five-levels, and feasibility as the dependent variable. Post-hoc deviation contrasts were conducted (i.e., the mean feasibility rating for each age group was compared against the grand mean of each age group except for the reference group), with p < .01 used to minimize the risk of type-1 error.

In assessing provider perceived feasibility of administering ERP via telehealth relative to in-person at different levels of OCD symptom severity, a repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted with symptom severity as the independent variable with three-levels, and feasibility as the dependent variable. Paired-sample t-tests were conducted, with p < .01 used to minimize risk the of type-1 error.

Lastly, a series of paired samples t-tests were conducted to examine differences in perceived ability to identify and address factors that commonly interfere with ERP delivery during both in-person and telehealth ERP. A conservative p < .001 was set as the significance value to account for multiple comparisons.

3. Results

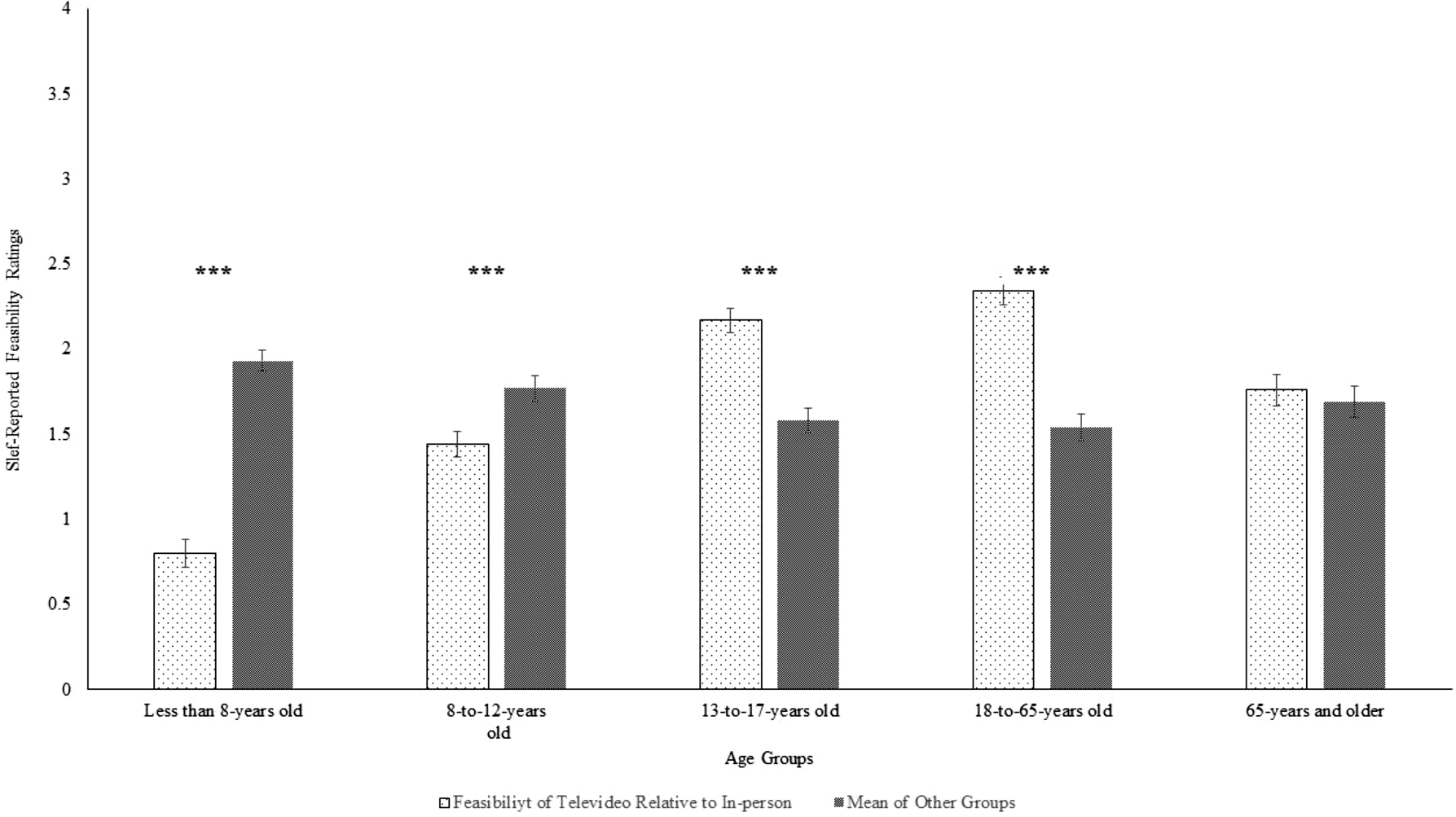

To assess the feasibility of delivering ERP via telehealth relative to in-person, self-reported feasibility ratings for each age-group were subjected to a repeated-measures ANOVA. Mauchly’s test revelated a violation of sphericity, χ2(9) = 118.18, p < .001; degrees of freedom were corrected using Greenhouse-Geisser estimates of sphericity (ε = 0.69). Following correction, the omnibus test revealed a significant effect of age F(2.76, 292.97) = 104.40, p < .001, , demonstrating that providers report different feasibility ratings for delivering ERP via telehealth relative to in-person across the different age-groups assessed in the study.

To minimize the number of post-hoc tests, deviation contrasts were conducted to delineate these differences in perceived feasibility. Feasibility ratings for respective age-groups were as follows: Less than 8-years old (M = 0.78, SD = 0.85); 8-to-12-years old (M = 1.43, SD = 0.78); 13-to-17-years old (M = 2.14, SD = 0.78); 18-to-65-years old (M = 2.31, SD = 0.85); 65-years and older (M = 1.76, SD = 0.95). Age-groups where telehealth relative to in-person ERP was rated as more feasible than the mean of all other groups included: 13-to-17-years old t(106) = 10.33, p < .001, d = 0.99; 18-to-65-years old, t(106) = 0.93, p < .001, d = 0.71. Age-groups where telehealth relative to in-person ERP was rated as less feasible than the mean of all other groups included: less than 8-years old, t(106) = −16.78, p < .001, d = −1.62; 8-to-12-years old, t(106) = −0.21, p < .001, d = 1.0. A non-significant difference was observed for the 65-years and older group compared to the mean of the other groups, t(106) = 0.86, p > .05. These results are displayed in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Self-reported feasibility ratings for delivering ERP via telehealth relative to in-person for different age-groups (0 = much less feasible; 4 = much more feasible). Error-bars reflect standard error of the mean. *** = p < .001.

In assessing the feasibility of delivering ERP via telehealth relative to in-person with patients at different levels of symptom severity, self-reported feasibility ratings for each of the three symptom-severity groups (mild-to-moderate; moderate-to-severe; and severe) were subjected to a repeated-measures ANOVA. Mauchly’s test of sphericity revelated a violation of sphericity, χ2(2) = 33.74, p < .001; degrees of freedom were corrected using Greenhouse-Geisser estimates of sphericity (ε = 0.79). Upon correction, results revealed a significant effect of symptom severity F(1.58, 179.74) = 48.35, p < .001, , demonstrating that providers report different feasibility ratings for delivering ERP via telehealth relative to in-person across the different symptom severity levels.

Planned contrasts were used to delineate these differences in perceived feasibility. Feasibility ratings for respective OCD symptom severity groups were as follows: mild-to-moderate (M = 2.18, SD = 0.59); moderate-to-severe (M = 1.87, SD = 0.76); severe (M = 1.47, SD = 0.96). Greater feasibility was reported for mild-to-moderate compared to moderate-to-severe, t(110) = 5.52, p < .001, d = 0.52. A similar result was observed contrasting mild-to-moderate with severe, t(110) = 8.08, p < .001, d = 0.77. Finally, greater feasibility was also reported for moderate-to-severe relative to severe, t(110) = 5.75, p < .001, d = 0.55. Taken together, these findings indicate providers feel that at higher levels of OCD symptom severity, delivering ERP via telehealth is less feasible relative to in-person delivery of ERP. These results are displayed in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Self-reported feasibility ratings for delivering ERP via telehealth relative to in-person across different levels of OCD symptom severity (0 = much less feasible; 4 = much more feasible). Error-bars reflect standard error of the mean. *** = p < .001.

To assess provider ability to detect and address behaviors that interfere with ERP, self-reported ratings for both telehealth and in-person ERP were subjected to a series of paired-samples t-tests. All p’s < 0.001, providing evidence that providers felt better able to identify and address these behaviors in-person than in a telehealth setting.. These behaviors for both in-person and telehealth, along with descriptive statistics, t-statistics, and effect sizes, are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Provider ability to identify and address factors complicating effective ERP delivery.

| In-person |

Telehealth |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | t-test | Effect size | |

|

| ||||||

| Cognitive avoidance | 3.53 | .89 | 2.91 | .92 | 6.54*** | .62 |

| Self-soothing, fidgeting, behavioral distractions | 3.58 | .57 | 2.76 | .87 | 9.32*** | .89 |

| Self-reassurance seeking | 3.56 | .60 | 3.06 | .79 | 6.65*** | .63 |

| Reassurance seeking from others | 3.47 | .63 | 3.05 | .86 | 4.90*** | .47 |

| Environmental distractions | 3.55 | .58 | 2.30 | 1.08 | 11.74*** | 1.11 |

| Alcohol or substance use | 3.15 | .79 | 2.19 | .93 | 9.48*** | .90 |

| Non-verbal communication | 3.55 | .59 | 2.56 | .87 | 10.07*** | .96 |

| Difficulty delivering/patient understanding of psychoeducation. | 3.15 | 1.00 | 2.62 | .93 | 5.04*** | .48 |

| Limited symptom insight | 3.16 | .78 | 2.78 | .81 | 4.67*** | .44 |

| Limited between-session exposure practice | 3.18 | .83 | 2.77 | .93 | 4.65*** | .44 |

Note. Self-reported ratings for ability to identify and address were reported using a 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree) scale. Cohn’s d was used to calculate effect size.

p < .001.

4. Discussion

The present study assessed OCD provider perceptions of in-person and telehealth ERP to identify OCD patient profiles that providers feel are more and less appropriate for telehealth services, as well as provider perceived ability to identify and address factors interfering with effective ERP delivery. Providers reported telehealth relative to in-person ERP to be less feasible for younger patients (i.e., the less than 8-years-old and 8-to-12-years old groups) compared to all other age groups assessed. Significantly greater feasibility was reported for 13-to-17-years old and 18-to-65-yearsold groups compared to the feasibility ratings for all age-groups assessed, while no difference in feasibility was observed for older individuals (i.e., ≥ 65-years). As expected, providers also reported telehealth relative to in-person ERP delivery as more feasible at lower levels of OCD symptom severity. Lastly, these data demonstrate that providers feel better able to identify and address problematic factors during in-person compared to telehealth ERP. These findings provide evidence that providers endorse reservations about telehealth services for some individuals, even though existing literature supports both in-person and telehealth ERP as effective modalities for treating OCD (Comer et al., 2017; Fletcher et al., 2021; Ferrando and Selai, 2021; Goetter et al., 2014; McKay et al., 2015; McGuire et al., 2015 Storch et al., 2011;Vogel et al., 2014; Wootton et al., 2013; Wootton, 2016). Telehealth appears as a likely medium through which psychotherapies will continue to be delivered, even after the conclusion of the COVID-19 pandemic (Shklarski et al., 2021a; Shklarski et al., 2021b).

The treatment considerations presented here fit in the broader context of existing ERP and telehealth psychotherapy literature. Even with substantial support for telehealth ERP delivery, including with preadolescent children (Comer et al., 2017; Storch et al., 2011), clinicians appear to have concerns about using telehealth with this younger population. This may be due to difficulties engaging younger children and developing a close therapeutic relationship over video, though future work may explore specific concerns providers have with this population. Existing literature suggests when working with younger individuals, ERP should incorporate developmental adaptations, including tailoring psychoeducation to meet each patients’ ability to comprehend content, as well as including the involvement of parents to address family factors that may perpetuate presenting symptomology (i.e., Choate-Summer et al., 2008; Freeman et al., 2008). Future work may directly assess in-person and telehealth modalities with this specific age range and determine whether clinicians’ concerns for working with this population are matched by weaker efficacy. It may also be that further training is needed for providers of school-age youth, who may have a more difficult time adapting to telehealth compared to adolescents or adults.

Clinicians endorsed greater difficulty delivering psychoeducational materials over telehealth. This may help explain why providers reported lower perceived feasibility for telehealth ERP delivery for younger individuals. Furthermore, compared to adult populations, younger individuals with OCD are more likely to exhibit limited insight regarding symptom severity (Geller et al., 2021; Jacob et al., 2014; Selles et al., 2020). In the present study, providers endorsed greater difficulty identifying and addressing limited symptom insight, which may also contribute to lower perceived feasibility for delivering ERP via telehealth. These concerns specific to younger populations also mirror what has been reported in the educational literature, where schooling delivered over video may not be suitable for some young learners, specifically because of motivational and environmental factors impacting engagement (Black et al., 2021). Better understanding the factors specific to telehealth that impact younger individuals in the context of ERP may allow future intervention researchers to develop treatment adaptations for telehealth ERP delivery.

In addition to these findings regarding younger individuals, providers also endorsed lower feasibility of delivering ERP over telehealth for more severe OCD presentations. Individual outpatient ERP is generally effective for both children and adults with OCD, while higher levels of care, including residential treatment, can be indicated for those with greater symptom severity (Abramowitz et al., 2005; Leonard et al., 2016; Pozza and Dèttore, 2017; Stewart et al., 2005). At higher levels of symptom severity, it is often more difficult to help patients minimize compulsive behaviors, which is why more intensive intervention with greater provider-patient contact may be necessary (Björgvinsson et al., 2013). The telehealth medium may not be optimal for higher levels of OCD symptom severity. Providers in the current study endorsed greater difficulty identifying and addressing self-reassurance, and reassurance seeking from others, avoidance, among other problematic factors, all of which require more direct clinician support at higher levels of OCD severity that may be more difficult to provide in a telehealth environment. The limited field of view afforded via telehealth could contribute to the difficulties identifying these factors, causing OCD providers to feel telehealth is suboptimal at higher severity levels. Future work should continue to elucidate why providers perceive individuals with more severe OCD to require in-person therapy and whether these perceptions are matched by the empirical data (e.g., through side-by-side clinical trials). Together, the present findings suggest that ERP clinicians feel telehealth is less appropriate for certain groups (i.e., younger individuals and those with more severe OCD symptoms).

Results specific to provider ability to address factors adversely impacting the course of treatment are consistent with a broader literature. Borrowing from dialectal behavioral therapy (DBT), treatment interfering behaviors get in the way of and adversely impact the course of therapy (Linehan, 1987; 1993). These behaviors are problematic in that they often prevent individuals from experiencing necessary anxiety to habituate or experience inhibitory learning about obsessive fears, ultimately resulting in poorer treatment outcomes (Sloan and Telch, 2002; Taylor and Alden, 2010). Recent research provides further support of the problematic nature of treatment interfering behaviors in OCD treatment, where a negative association has been observed between the presence of treatment interfering behaviors and provider perceptions of symptom improvement (Davis et al., 2020). As it relates to the present study, providers feel less able to identify and address ERP-specific treatment interfering behaviors over telehealth compared to in-person. Together, concerns raised by providers in this study should motivate more systematic research to investigate whether treatment interfering behaviors are truly more interfering via telehealth modalities.

While the present study offers evidence that providers believe telehealth ERP is less appropriate for certain individuals with OCD, there are study limitations that may be addressed in future research. Firstly, feasibility of specific exposure exercises was not assessed; it is plausible to suspect different types of exposures, such as driving exposures to address fears of harming others, are better suited for in-person compared to telehealth ERP. The present study also only assessed provider perceptions about telehealth versus in-person ERP. It did not assess treatment outcomes for either modality, nor did it assess perceptions specific to the patient populations treated by the participants (e.g., child psychologists were asked to respond to items for both adult and child patients). Future research may seek to address these limitations by examining the relationship between provider perceptions of these modalities and the effects they have on treatment outcomes for different age-groups and OCD symptom severity, and whether the ERP interfering factors raised in this study are truly more interfering in telehealth. Future research would also benefit from patient perspectives to complement clinician perspectives. Furthermore, the cross-sectional nature of the data collected may raise concerns, as data were collected approximately one-and-one-half years after the onset of the COVID-19 and perceptions may change as telehealth ERP becomes more commonplace and better incorporated in graduate training programs. Provider experience with telehealth may be an important variable to control for in future research. Finally, the sample size in the present study (N = 113) may appear small for a self-report study, although it should be noted that data were sampled from a relatively small population (i.e., OCD-ERP providers). Additionally, the present sample size is consistent with data from a recent systematic review (Connolly et al., 2020) of 38 studies on provider perceptions of telehealth psychotherapy, with an average sample size of 83.39 participants per study. Together, these factors further highlight the need for additional research in this area to both replicate and expand upon the present findings. Even with the noted limitations, the present study provides important empirical evidence for clinicians proving telehealth ERP for OCD, as well as a call for additional research in this area.

5. Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic led virtually all mental health care providers, including those providing ERP to patients with OCD, to transition to a telehealth format. Strong pre-COVID-19 evidence for the effective telehealth delivery of psychotherapies (Elford et al., 2000; Rees and Maclaine, 2015; Storch et al., 2011; Tuerk et al., 2018) aided this transition. The present study identified several factors that appear to make this format more difficult for ERP providers. Specifically, providers found it less feasible to deliver ERP via telehealth when working with patients under 13-years-old and with patients who present with higher levels of OCD symptom severity. Providers also feel they are less capable of identifying and addressing interfering factors during telehealth ERP as compared to in-person ERP, such as self-reassurance, avoidance, or substance use, among others. Nevertheless, due to its many practical and perceived benefits, widespread utilization of telehealth-based ERP is likely to persist beyond the pandemic (Candelari et al., 2021; Sequeria et al., 2021; Shklarski et al., 2021a; Shklarski et al., 2021b). Therefore, additional research is needed to establish guidelines for identifying and addressing interfering behaviors via telehealth and determine which symptom presentations, age ranges, levels of insight, and other individual patient factors necessitate a recommendation of in-person over telehealth ERP.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the therapists who participated in this study.

Funding/Support

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P50HD103555 for use of the Clinical and Translational Core facilities. It was also supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health under Award Numbers R01MH125958 and 1RF1MH121371. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosures: Dr. Storch discloses the following relationships: consultant for Biohaven Pharmaceuticals; Book royalties from Elsevier, Springer, American Psychological Association, Wiley, Oxford, Kingsley, and Guilford; Stock valued at less than $5000 from NView; Research support from NIH, IOCDF, Ream Foundation, and Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board.

Dr. Guzick discloses the following relationships: support from the REAM Foundation/Misophonia Research Fund and the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board.

Dr. Goodman discloses the following relationships: support from Brainsway, Biohaven Pharmaceutics and the NIH; Medtronic donated devices to a research project; and he received consulting fees from Biohaven and Neurocrine Biosciences.

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Andrew D. Wiese: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Formal analysis. Kendall N. Drummond: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Resources. Madeleine N. Fuselier: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Resources. Jessica C Sheu: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Resources. Gary Liu: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Resources. Andrew G. Guzick: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Project administration, Formal analysis. Wayne K. Goodman: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Eric A. Storch: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Supervision, Formal analysis.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114610.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

- Abramowitz JS, Franklin ME, Zoellner LA, Dibernardo CL, 2002. Treatment compliance and outcome in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav. Modif. 26 (4), 447–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramowitz JS, Whiteside SP, Deacon BJ, 2005. The effectiveness of treatment for pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis. Behav. Ther. 36 (1), 55–63. 10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80054-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association, 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association, Arlington. [Google Scholar]

- Black E, Ferdig R, Thompson LA, 2021. K-12 virtual schooling, COVID-19, and student success. JAMA Pediatr. 175 (2), 119–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyarsky BJ, Po-Yu Chiang T, Werbel WA, Durand CM, Avery RK, Getsin SN, Jackson KR, Kernodle AB, Van Pilsum Rasmussen SE, Massie AB, Segev DL, Garonzik-Wang JM, 2020. Early impact of COVID-19 on transplant center practices and policies in the United States. Am. J. Transplant. 20 (7), 1809–1818. 10.1111/ajt.15915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björgvinsson T, Hart AJ, Wetterneck C, Barrera TL, Chasson GS, Powell DM, Heffelfinger S, Stanley MA, 2013. Outcomes of specialized residential treatment for adults with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J. Psychiatr. Pract. 19 (5), 429–437. 10.1097/01.pra.0000435043.21545.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candelari AE, Wojcik KD, Wiese AD, Goodman WK, Storch EA, 2021. Expert opinion in obsessive-compulsive disorder: treating patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic. Personal. Med. Psychiatry 27, 100079. 10.1016/j.pmip.2021.100079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choate-Summers ML, Freeman JB, Garcia AM, Coyne L, Przeworski A, Leonard HL, 2008. Clinical considerations when tailoring cognitive behavioral treatment for young children with obsessive compulsive disorder. Educ. Treatm. Child. 31 (3), 395–416. [Google Scholar]

- Comer JS, Furr JM, Kerns CE, Miguel E, Coxe S, Elkins RM, Freeman JB, 2017. Internet-delivered, family-based treatment for early-onset OCD: a pilot randomized trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 85 (2), 178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly SL, Miller CJ, Lindsay JA, Bauer MS, 2020. A systematic review of providers’ attitudes toward telemental health via videoconferencing. Clin. Psychol.: Sci. Pract. 27 (2), e12311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis ML, Fletcher T, McIngvale E, Cepeda SL, Schneider SC, La Buissonnière Ariza V, Egberts J, Goodman W, Storch EA, 2020. Clinicians’ perspectives of interfering behaviors in the treatment of anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders in adults and children. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 49 (1), 81–96. 10.1080/16506073.2019.1579857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elford R, White H, Bowering R, Ghandi A, Maddiggan B, St John K, House M, Harnett J, West R, Battcock A, 2000. A randomized, controlled trial of child psychiatric assessments conducted using videoconferencing. J. Telemed. Telecare 6 (2), 73–82. 10.1258/1357633001935086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez E, Woldgabreal Y, Day A, Pham T, Gleich B, Aboujaoude E, 2021. Live psychotherapy by video versus in-person: a meta-analysis of efficacy and its relationship to types and targets of treatment. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 28 (6), 1535–1549. 10.1002/cpp.2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrando C, Selai C, 2021. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the effectiveness of exposure and response prevention therapy in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. J. Obsessive Compuls. Relat. Disord. 31 10.1016/j.jocrd.2021.100684. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher TL, Boykin DM, Helm A, Dawson DB, Ecker AH, Freshour J, Hundt NE, 2021. A pilot open trial of video telehealth-delivered exposure and response prevention for obsessive-compulsive disorder in rural Veterans. Mil. Psychol. 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman JB, Garcia AM, Coyne L, Ale C, Przeworski A, Himle M, Leonard HL, 2008. Early childhood OCD: preliminary findings from a family-based cognitive-behavioral approach. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc.t Psychiatry 47 (5), 593–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller DA, Homayoun S, Johnson G, 2021. Developmental considerations in obsessive compulsive disorder: comparing pediatric and adult-onset cases. Front. Psychiatry 12, 678538. 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.678538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetter EM, Herbert JD, Forman EM, Yuen EK, Thomas JG, 2014. An open trial of videoconference-mediated exposure and ritual prevention for obsessive-compulsive disorder. J. Anxiety Disord. 28 (5), 460–462. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Delgado P, Heninger GR, & Charney DS (1989). The yale-brown obsessive compulsive scale: II. Validity. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry, 46(11), 1012–1016. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110054008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himle JA, Van Etten ML, Janeck AS, Fischer DJ, 2006. Insight as a predictor of treatment outcome in behavioral group treatment for obsessive–compulsive disorder. Cognit. Ther. Res. 30 (5), 661–666. [Google Scholar]

- Iacobucci G, 2020. Covid-19: all non-urgent elective surgery is suspended for at least three months in England. BMJ: Br. Med. J. (Online) 368, m1106. 10.1136/bmj.m1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob ML, Larson MJ, Storch EA, 2014. Insight in adults with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Compr. Psychiatry 55 (4), 896–903. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard RC, Franklin ME, Wetterneck CT, Riemann BC, Simpson HB, Kinnear K, Cahill SP, Lake PM, 2016. Residential treatment outcomes for adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychother. Res.: J. Soc. Psychother. Res. 26 (6), 727–736. 10.1080/10503307.2015.1065022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, 1987. Dialectical behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder: theory and method. Bull. Menninger Clin. 51 (3), 261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan M, 1993. Skills Training Manual For Treating Borderline Personality Disorder, Vol. 29. Guilford press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- McKay D, Sookman D, Neziroglu F, Wilhelm S, Stein DJ, Kyrios M, Matthews K, Veale D, 2015. Efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 225 (3), 236–246. 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire JF, Piacentini J, Lewin AB, Brennan EA, Murphy TK, Storch EA, 2015. A meta-analysis of cognitive behavior therapy and medication for child obsessive–compulsive disorder: moderators of treatment efficacy, response, and remission. Depress. Anxiety 32 (8), 580–593. 10.1002/da.22389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olatunji BO, Davis ML, Powers MB, Smits JA, 2013. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis of treatment outcome and moderators. J. Psychiatr. Res. 47 (1), 33–41. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinciotti CM, Bulkes NZ, Horvath G, Riemann BC, 2022. Efficacy of intensive CBT telehealth for obsessive-compulsive disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Obsessive Compuls. Relat. Disord. 32, 100705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozza A, Dèttore D, 2017. Drop-out and efficacy of group versus individual cognitive behavioural therapy: what works best for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder? A systematic review and meta-analysis of direct comparisons. Psychiatry Res. 258, 24–36. 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees CS, Maclaine E, 2015. A systematic review of videoconference-delivered psychological treatment for anxiety disorders. Aust. Psychol. 50 (4), 259–264. 10.1111/ap.12122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reid JE, Laws KR, Drummond L, Vismara M, Grancini B, Mpavaenda D, Fineberg NA, 2021. Cognitive behavioural therapy with exposure and response prevention in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Compr. Psychiatry 106, 152223. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2021.152223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasangohar F, Bradshaw MR, Carlson MM, Flack JN, Fowler JC, Freeland D, Head J, Marder K, Orme W, Weinstein B, Kolman JM, Kash B, Madan A, 2020. Adapting an outpatient psychiatric clinic to telehealth during the COVID-19 Pandemic: a Practice Perspective. J. Med. Internet Res. 22 (10), e22523. 10.2196/22523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selles RR, Højgaard D, Ivarsson T, Thomsen PH, McBride NM, Storch EA, Geller D, Wilhelm S, Farrell LJ, Waters AM, Mathieu S, Stewart SE, 2020. Avoidance, insight, impairment recognition concordance, and cognitive-behavioral therapy outcomes in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 59 (5), 650–659. 10.1016/j.jaac.2019.05.030 e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sequeira A, Alozie A, Fasteau M, Lopez AK, Sy J, Turner KA, Björgvinsson T, 2021. Transitioning to virtual programming amidst COVID-19 outbreak. Couns. Psychol. Q. 34 (3–4), 538–553. 10.1080/09515070.2020.1777940. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shklarski L, Abrams A, Bakst E, 2021a. Navigating changes in the physical and psychological spaces of psychotherapists during Covid-19: when home becomes the office. Pract. Innovat. 6 (1), 55–66. 10.1037/pri0000138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shklarski L, Abrams A, Bakst E, 2021b. Will we ever again conduct in-person psychotherapy sessions? Factors associated with the decision to provide in-person therapy in the age of COVID-19. J. Contemp. Psychother. 1–8. 10.1007/s10879-021-09492-w. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan T, Telch MJ, 2002. The effects of safety-seeking behavior and guided threat reappraisal on fear reduction during exposure: an experimental investigation. Behav. Res. Ther. 40 (3), 235–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SE, Stack DE, Farrell C, Pauls DL, Jenike MA, 2005. Effectiveness of intensive residential treatment (IRT) for severe, refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 39 (6), 603–609. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Caporino NE, Morgan JR, Lewin AB, Rojas A, Brauer L, Larson MJ, Murphy TK, 2011. Preliminary investigation of web-camera delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy for youth with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 189 (3), 407–412. 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CT, Alden LE, 2010. Safety behaviors and judgmental biases in social anxiety disorder. Behav. Res. Ther. 48 (3), 226–237. 10.1016/j.brat.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuerk PW, Keller SM, Acierno R, 2018. Treatment for anxiety and depression via clinical videoconferencing: evidence base and barriers to expanded access in practice. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ) 16 (4), 363–369. 10.1176/appi.focus.20180027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel PA, Solem S, Hagen K, Moen EM, Launes G, Håland ÅT, Hansen B, Himle JA, 2014. A pilot randomized controlled trial of videoconference-assisted treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav. Res. Ther. 63, 162–168. 10.1016/j.brat.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton MG, Gershkovich M, Gallagher T, Foa EB, Simpson HB, 2018. Behavioral avoidance predicts treatment outcome with exposure and response prevention for obsessive–compulsive disorder. Depress. Anxiety 35 (3), 256–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wootton BM, 2016. Remote cognitive–behavior therapy for obsessive–compulsive symptoms: a meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 43, 103–113. 10.1159/000348582 and ritual prevention. Psychopathology, 46(6), 365–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wootton BM, Dear BF, Johnston L, Terides MD, Titov N, 2013. Remote treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized controlled trial. J. Obsessive Compuls. Relat. Disord. 2 (4), 375–384. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.