Significance

The secret of the human brain in high-level information processing compared to solid-state electronics, e.g., pattern recognition, resides in the “nonlinearity” of synapses constituting the complex neural networks. Synaptic connections can strengthen or weaken by themselves with time and history of the past signals. We construct an ion-based aqueous platform, “iontronics,” by combining the ionic diode with chemical precipitation to emulate logical clusters of artificial synapses. In contrast to other previous attempts, the proposed device is an aqueous unidirectional system just like biological neurons, which is capable of ionic signal integration. This is a report of gel-based two-terminal iontronic information processors making one great step forward to truly neuromimetic analogs.

Keywords: iontronics, synaptic plasticity, neuromorphic device, precipitation, ionic diode

Abstract

In this study, an aqueous nonlinear synaptic element showing plasticity behavior is developed, which is based on the chemical processes in an ionic diode. The device is simple, fully ionic, and easily configurable, requiring only two terminals—for input and output—similar to biological synapses. The key processes realizing the plasticity features are chemical precipitation and dissolution, which occur at forward- or reverse-biased ionic diode junctions in appropriate reservoir electrolytes. Given that the precipitate acts as a physical barrier in the circuit, the above processes change the diode conductivity, which can be interpreted as adjusting “synaptic weight” of the system. By varying the operating conditions, we first demonstrate the four types of plasticity that can be found in biological system: long-term potentiation/depression and short-term potentiation/depression. The plasticity of the proposed iontronic device has characteristics similar to those of neural synapses. To demonstrate its potential use in comparatively complex information processing, we develop a precipitation-based iontronic synapse (PIS) capable of both potentiation and depression. Finally, we show that the postsynaptic signals from the multiple excitatory or inhibitory PISs can be integrated into the total “dendritic” current, which is a function of time and input history, as in actual hippocampal neural circuits.

Understanding the way the biological system operates and its related applications have been one of the hugest research domains for a long time in the history of scientific developments. In terms of information processing, in particular, researchers have invested ceaseless efforts in exploring human brain and nervous system, although it is still distant to unravel them. It is true that the computer, a solid-state electronic information processor originated on the basis of von Neumann architecture (1), excels in individual numerical calculations compared to the brain, and is undergoing ceaseless development. However, the human brain still has a higher energy efficiency than solid-state electronic systems in high-level information processing tasks such as pattern recognition and intelligent reasoning. This is a consequence of their remarkably different working principles (2). Solid-state information processing relies on the control of electrons or holes, whereas biological systems use ions and molecules as signal carriers in complex neuronal networks composed of more than 1015 synapses (3). The multiplicity of signal carriers leads to degenerate ionic signals, which are associated with nonlinear characteristics, e.g., hysteresis and plasticity. Difficulties in accomplishing these complex neuromimetic functions in electronic circuitry or software programming (4) propelled the scientific community to open up a new field, iontronics. Iontronics is an artificial aqueous technology based on ions and molecules with a major focus on biomimetic information processing (2, 5).

Although numerous nonlinear ionic devices have been reported since the pioneering observation of bipolar membrane (BM)-based ionic current rectification reported by Bockris et al. (6), the majority focused on demonstrating only basic information processing elements such as ionic diodes (5, 7–14), transistors (15–21), logic gates (5, 8, 22, 23), and capacitors (24). Recently, however, researchers have started paying attention to actualizing more sophisticated nonlinear functions that can be found in the nervous system, synaptic plasticity or dendritic integration (25). Synaptic plasticity refers to the capacity of the nervous system to change the activity and strength of synaptic signal transmission (26, 27). Generally, plasticity plays a crucial role in complex neural functions such as habituation, recognition, learning, and memory, because the synaptic connection gradually strengthens or weakens in various patterns in response to specific input stimuli. The incoming signals from countless synapses are summed through dendritic integration, and then the signal continues to propagate further (28, 29). Most synaptic plasticity functions developed on an iontronic platform employ organic electrochemical transistors (OECTs) using a conducting polymer as the active layer (30, 31), which are three-terminal devices, different from actual neurons, which have a two-terminal nature. Gkoupidenis et al. employed an OECT composed of poly (3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly (styrene sulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS) to replicate short-term plasticity by temporal ion injection triggered by gate voltage modulation (32), and demonstrated homeoplasticity through global electrolyte gating upon OECT array (33). They also reported long-term plasticity in OECTs made of poly(tetrahydrofuran)-based PEDOT derivative (34). Gerasimov et al. developed an evolvable OECT by in situ electropolymerization of a conducting polymer between source and drain terminals, which showed both short- and long-term plasticity behaviors (35, 36).

In this study, we demonstrated iontronic synaptic plasticity behaviors in a two-terminal BM-based ionic diode, where the formation or dissolution of an ionic precipitate at the junction triggers either temporal or long-lasting changes in the conductivity of the circuit (Fig. 1A). This is an example of a two-terminal plasticity device constructed on a fully aqueous ionic platform composed of only charged hydrogels and electrolyte, wherein all types of plasticity occur. The precipitate formed under a forward bias acts as a physical blockage, which decreases the conductivity, i.e., synaptic depression, whereas a reverse bias potential results in synaptic potentiation caused by the precipitate dissolution. Depending on the input history or working conditions, the effect of precipitate formation and dissolution strengthens or weakens the synaptic weight of the diode in a temporal and long-lasting manner, respectively. This effect can be classified into long-term potentiation (LTP), long-term depression (LTD), short-term potentiation (STP), and short-term depression (STD). To highlight the potential of such iontronic plasticity for future biomimetic information processing, we constructed a precipitation-based iontronic synapse (PIS) composed of a pair of ionic plasticity diodes, which can be potentiated or depressed by the history of input stimuli. As a proof of concept, we also demonstrated an iontronic version of dendritic signal integration with combination of excitatory and inhibitory PISs, which reflected the CA3-CA1 and interneuron-CA1 synapses in the hippocampal neural circuit (37).

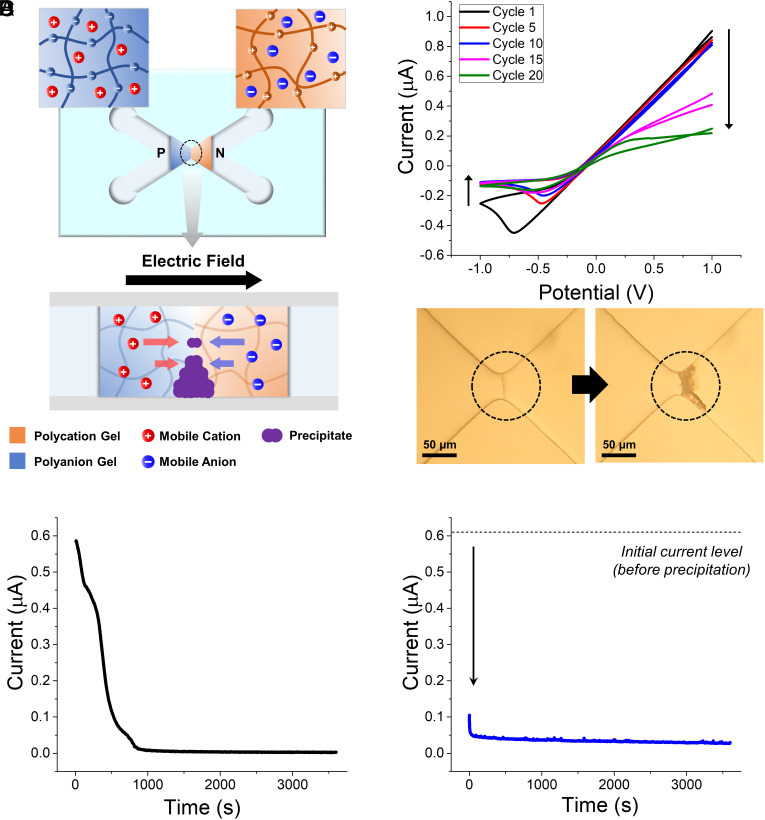

Fig. 1.

(A) Schematic of LTD mediated by chemical precipitation at ionic diode junction. Mobile cations and anions from each reservoir electrolyte precipitate at junction under forward-bias potential. (B) 1st (black), 5th (red), 10th (blue), 15th (magenta), and 20th (green) CVs obtained during continuous voltage cycling of ionic diode immersed in 5 mM BaCl2(aq) (p-side) and 5 mM Na2SO4(aq) (n-side). Scan rate is 20 mV/s. (Inset: optical microscope images of diode junction before and after voltage cycling) Current profiles recorded for 1 h while applying +1 V constant forward-bias voltage (C), to ionic diode immersed in 5 mM BaCl2(aq) (p-side) and 5 mM Na2SO4(aq) (n-side) and (D), to same diode whose reservoir electrolytes are replaced with 10 mM KCl(aq) after (C). Sampling interval is 0.5 s.

Results and Discussion

Iontronic LTD via Precipitation at Ionic Diode Junction.

A chemical or physical alteration is required to endow a BM-based diode with temporary or permanent plasticity behaviors triggered by a series of input signals. Electrical properties of BM-based ionic diodes operating under inert electrolyte condition, e.g., NaCl(aq), are practically independent of the past history of input signals (11). Although it shows a hysteresis in reverse-bias region in cyclic voltammogram (CV), the steady-state conductivity and overall shape of CV do not change unless the polyelectrolyte gel network undergoes some semi-permanent changes, e.g., deformation. Therefore, we used a chemical precipitate formed at the ionic diode junction by a forward-bias penetration current as a physical blockage triggering a change in the ion conductivity of the diode. In this study, we presumed that the direction of ionic signal transmission coincides with that of the forward-bias current in the ionic diode, which conforms well with the unidirectional nature of signal delivery along neurons. In other words, the forward-bias conductivity of the diode represents its synaptic weight.

Fig. 1A shows the ionic diode composed of p-type poly(sulfopropyl acrylate) and n-type poly(diallyldimethylammonium chloride) hydrogels, with a precipitable pair of reservoir solutions on each gel side, e.g., barium chloride (BaCl2) solution on the p-type gel side (p-side) and sodium sulfate (Na2SO4) solution on the n-side. In this case, barium and sulfate ions accumulate at the junction under a forward-bias voltage to precipitate BaSO4. To graphically visualize effects of the precipitate during the diode operation, we continuously measured 20 cycles of CVs of an ionic diode in 5 mM BaCl2(aq) and 5 mM Na2SO4(aq) at each reservoir (Fig. 1B). In forward-bias region, the ionic current gradually decreased during the first 10 cycles and then rapidly decreased during the next 10 cycles, while the current level at 1.0 V reached about 25% of the initial value at the last cycle. Similarly, the magnitude of reverse-bias current also decreased as the voltage cycling proceeded, except most of the decrease in ionic current occurred in early stage. These observations indicate a decrease in conductivity of ionic diode in both the potential ranges, which is in line with the fact that the precipitate formed at the junction can physically block the ionic current. Optical microscope images in Fig. 1B confirm the formation of precipitation induced by the repetitive voltage cycling. Notably, the hysteresis effect in reverse-bias region was also attenuated with the increasing number of cycles, which may be attributed to the fewer number of ions accumulated throughout the forward bias region in the presence of precipitate. Movie S1 demonstrates the formation of BaSO4 precipitate in a temporal manner. A variety of electrolyte combinations can be employed for precipitation if the solubility product constant (Ksp) is sufficiently low, such as BaCO3 precipitation from BaCl2(aq) and Na2CO3(aq) at each side of the diode (SI Appendix, Fig. S1).

Applying constant forward-bias potential to the ionic diode allows for more straightforward decrease in ionic current during precipitate formation, as presented in Fig. 1C. Under a forward-bias voltage of +1 V, the ionic current flowing through the ionic diode interfaced with BaCl2(aq) and Na2SO4(aq) reservoir electrolytes is significantly decreased to ca. 0.5% initial value (0.6 μA to 3 nA) within 1,000 s by the BaSO4 precipitation (Fig. 1C). Once a sufficient amount of precipitate is formed at the junction and effectively blocks the ionic current, the decreased ionic current remains almost constant, even after the replacement of the reservoir electrolytes with inert KCl(aq) (Fig. 1D). This suggests that it is extremely difficult to dissolve the precipitate solely by exposing the diode in inert electrolytes. These phenomena reflect the LTD in the nervous system because certain types of input stimuli, i.e., prolonged forward-bias input voltage signals, produce an irreversible attenuation in signal transmission beyond the ionic diode. LTDs in actual biological system involve more complicated signal transduction mechanisms such as N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-based LTD on hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells or those found in the neocortex (27, 38). The decrease in the synaptic weight is in line with the decrease in the ionic diode conductivity caused by the precipitation. This iontronic LTD based on precipitate formation is an essential feature in constructing an iontronic synapse with plasticity.

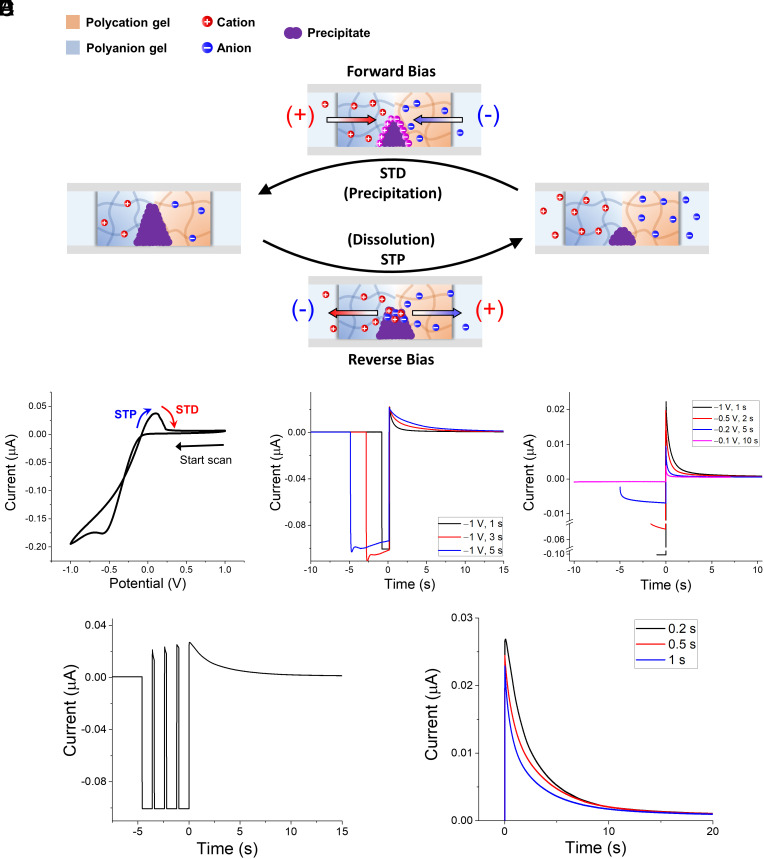

Iontronic STP and STD via Transitory Dissolution and Regeneration of Precipitate.

The conductivity change of the ionic diode caused by the input voltage stimuli can be temporary if the diode is immersed in a precipitable pair of electrolytes. Fig. 2A illustrates how the ionic diode exhibits short-term plasticity behavior—STP and STD—via the transient dissolution of the precipitate and reprecipitation. Here, the initial state is the ionic diode fully loaded with the precipitate at the junction. It is immersed in the same precipitable reservoir electrolytes, i.e., BaCl2(aq) and K2SO4(aq), with BaSO4(s) previously formed at the junction (see the leftmost diode illustration in Fig. 2A). Applying a forward-bias potential to this diode only permits a very low, constant ionic current of approximately several nanoamperes owing to the preformed precipitate (Fig. 1C). In contrast, a reserve-bias voltage temporarily dissolves a small amount of the precipitate by drawing cations and anions from the diode junction, momentarily increasing the diode conductivity (STP). The increased conductivity is immediately reverted to the initial value by the regeneration of the precipitate (STD), when the input voltage polarity is switched back from reverse to forward bias. The above short-term plasticity phenomena in an ionic diode were noticeable in the CV of the ionic diode with a preformed precipitate (Fig. 2B). The voltage scan in the reverse-bias region induces a hysteresis-like current bulge under the succeeding forward bias owing to the transient dissolution (STP) and instantaneous regeneration of the precipitate (STD). The precipitate seems to act as an ion source under reverse bias condition, which is in accordance with the high magnitude of reverse-bias current at −1 V compared to that of a normal ionic diode (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Against our expectation, however, SI Appendix, Fig. S3 implies that a dissociation of only a trace amount of precipitate is required to trigger the STP, given that the amount of precipitate in the top-view microscope image remains unchanged under reverse-bias potential. These iontronic short-term plasticity features reflect those found in the mammalian nervous system (26). Repeated activation at the neuromuscular synapse produces a transient increase in synaptic strength (STP) via increase in the presynaptic calcium level, which releases more neurotransmitters. The depletion of the available synaptic vesicles, in turn, decreases the synaptic weight (STD) during the replenishment of the neurotransmitter vesicles.

Fig. 2.

(A) Schematic of STP and STD mediated by temporal dissolution of preformed precipitate and reprecipitation at ionic diode junction. STP and STD occur under reverse and forward-bias conditions, respectively. (B–F) Electrical characterization data obtained from ionic diode with preformed BaSO4 precipitation at junction, immersed in 5 mM BaCl2(aq) (p-side; Left) and 5 mM Na2SO4(aq) (n-side; Right) reservoir electrolytes. (B) Single CV with scan rate of 20 mV/s. Ionic plasticity currents measured under single reverse-bias pulses of (C) various pulse lengths: 1 s (black), 3 s (red), and 5 s (blue) of −1 V, and (D) various pulse lengths and amplitudes: 1 s of −1 V (black), 2 s of −0.5 V (red), 5 s of −0.2 V (blue), and 10 s of −0.1 V (magenta). (E) Ionic currents measured under train of four reverse-bias pulses. Pulse width and interval are 1 s and 0.2 s, respectively. (F) Ionic currents obtained immediately after applying four consecutive reverse-bias pulses with differing pulse intervals: 0.2 s (black), 0.5 s (red), and 1 s (blue). Constant +0.5 V forward-bias potential is continuously applied as default to diode in all characterizations in (C–F), with sample interval of 0.01 s.

We further investigated the nonlinear characteristics of the ionic diode with precipitation when immersed in the precipitable pair of electrolytes relative to the characteristics of biological short-term plasticity. We modulated the parameters of the reverse-bias input voltage pulses, such as the pulse amplitude, width, and interval, and immediately recorded the ionic currents resulting from STP and STD under a forward-bias test voltage of 0.5 V. Fig. 2C shows an influence of the input pulse length on the STP behavior. A longer-duration reverse-bias pulse generates a high and gradually decaying STP current, which is ascribed to more precipitate dissolution from the diode junction. We also characterized the effect of input pulse amplitude by varying pulse width and amplitude while the product of the two parameters is constant (Fig. 2D). The short-term plasticity behaviors were rapidly attenuated with decrease in reverse-bias input voltage amplitude. For a more precise evaluation of this effect, we carried out exponential curve fitting of the four forward-bias ionic currents arising from STP in order to calculate their time constants (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A). The current curves were fitted using one-phase exponential decay function, Eq. 1, where y0, A, τ are steady-state ionic current, constant, and time constant, respectively.

| [1] |

The fitted parameters in SI Appendix, Table S1 indicate that the time constant increases as the input signal amplitude increases, which is in accordance with the observed short-term plasticity effect in Fig. 2D. Fig. 2E shows the ionic current caused by the short-term plastic change on applying a train of reverse-bias input stimuli to the precipitation diode. At many biological synapses, the postsynaptic response can be enhanced when two stimuli are transmitted within a short time interval (20 to 500 ms) (39). This phenomenon, also referred as paired-pulse facilitation (PPF), is a result of the transient elevation of the presynaptic calcium level, which allows more neurotransmitters to be released. Similarly, there is a gradual increase in the forward-bias “postsynaptic” current level on successive reverse-bias input stimuli, which is attributed to an accumulative precipitate dissolution during the reverse-bias pulses. Notably, the ionic current after the series of input pulses decays even more gradually than the current response to a single-pulse input. This is similar to the post-tetanic potentiation at neural synapses, which signifies an enhancement in the neurotransmitter release for up to a few minutes after the high-frequency train of stimuli (40). The STD duration required to effectively block the diode junction increases exponentially with increasing amount of dissolution. Fig. 2F shows the dependence of the postsynaptic ionic current on the time interval between the reverse-bias input pulses. Noticeably, shorter input pulses induce higher postsynaptic ionic currents. This suggests that our precipitation diode acts as a high-pass filter, responding to high-frequency input spikes with a higher efficacy than to the low-frequency input spikes. Filtering characteristics are essential in biological information processing, because the synaptic weights are modulated depending on the initial probability of the transmitter release (41).

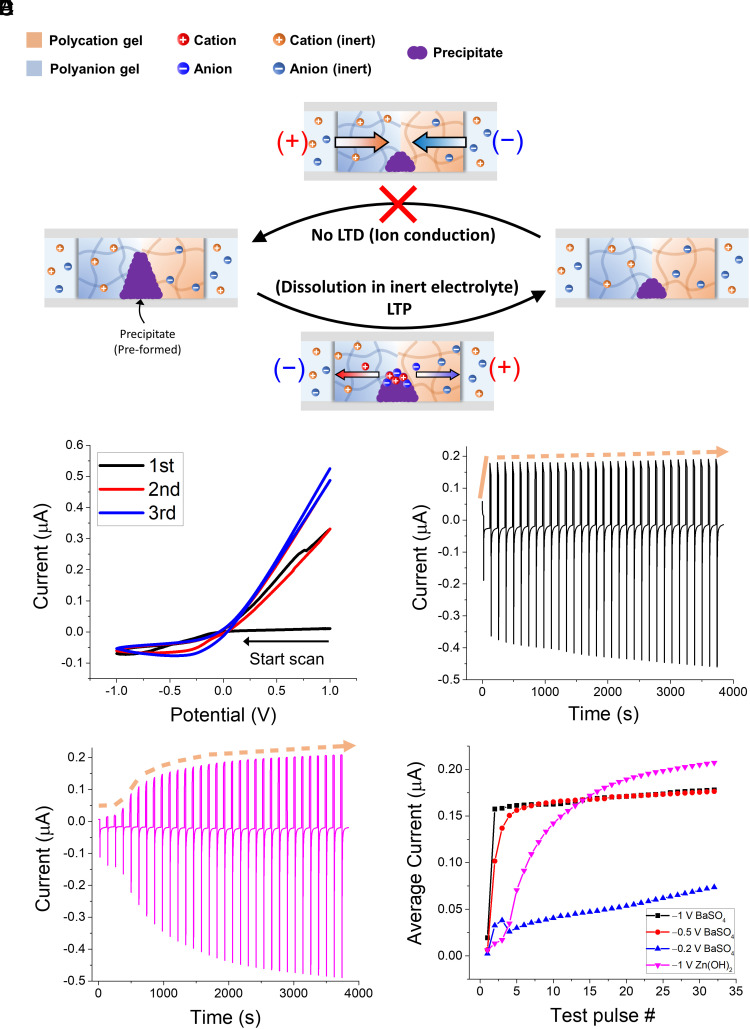

Iontronic LTP via Precipitate Dissolution in Inert Electrolytes.

Dissolving the precipitate at the ionic diode junction under a reverse-bias potential can also cause a persistent increase in the ionic conductivity of the diode under appropriate electrolyte conditions. Fig. 3A depicts the LTP of the ionic diode with a preformed precipitate at the junction. Similar to the STP described in the previous section (Fig. 2A), LTP is initiated with the elimination of the precipitate in response to a reverse-bias input signal; however, the entire process occurs in inert reservoir electrolytes such as NaCl(aq) or KCl(aq). Because the forward-bias ionic current is mostly carried by unprecipitable ions, e.g., K+ and Cl–, the precipitate cannot be regenerated once it is removed. This enduring effect caused by LTP is unambiguously visualized in the consecutive CVs presented in Fig. 3B. The initial diode with the BaSO4 precipitate shows a very low forward-bias current of approximately several nanoamperes; however, the current level rapidly increases to sub-microamperes as the diode continues to be subjected to the reverse-bias potential. We also applied a series of alternating pairs of reverse-bias input and forward-bias test pulses, i.e., −1 V for 200 s and 0.5 V for 20 s, to examine the LTP time scale (Fig. 3 C–E). The forward-bias test current rapidly increased to >100 nA within only one reverse pulse and further continued to increase more gradually. On the other hand, the ionic diode with Zn(OH)2 precipitate exhibited even slower LTP response to the same reverse-bias pulses, as demonstrated in Fig. 3D. This phenomenon may be ascribed to the difference in solubility product constant (Ksp) between the two precipitates: 1.1 × 10–10 (BaSO4) and 1.8 × 10–16 [Zn(OH)2], which correspond to 1.05 × 10–5 mol/L (BaSO4) and 3.56 × 10–6 mol/L [Zn(OH)2] of molar solubility in water, respectively. If the kinetics of dissolution reaction is sufficiently fast while the dissolved ions are removed from the junction instantaneously, the time scale of LTP will be primarily dependent on solubility of the precipitation. This implies that the iontronic potentiation property of ionic diodes can be adjusted with a proper choice of precipitation. Meanwhile, the magnitude of reverse-bias current spike also increases as LTP occurs, which seems to be in accordance with the LTP-mediated increase in ionic diode conductivity. As with the iontronic STP, the elimination of precipitate resulted from a prolonged reverse-bias potential does not give any noticeable change in microscope image (SI Appendix, Fig. S5).

Fig. 3.

(A) Schematic of LTP initiated by irreversible dissolution of preformed precipitate at ionic diode junction. Diode is immersed in inert (unprecipitable) reservoir electrolytes. (B) Three initial CVs obtained from ionic diode with preformed BaSO4 precipitate in 10 mM KCl(aq) reservoir electrolyte. Scan rate is 20 mV/s. Ionic currents measured while applying repetitive reverse-bias pulses of −1 V and 100 s to ionic diodes with preformed (C) BaSO4 and (D) Zn(OH)2. Orange dashed lines indicate the trend of forward-bias current peaks. Diodes are immersed in 10 mM KCl(aq). Forward-bias test pulses of +0.5 V and 20 s are applied between every reverse-bias pulse to monitor diode conductivity. Sample interval is 0.1 s. (E) Time average values of individual forward-bias test currents obtained under different conditions including (C and D): −1 V [black, (C)], −0.5 V (red), −0.2 V (blue) reverse-bias pulses to ionic diode with preformed BaSO4, and −1 V reverse-bias pulses to ionic diode with preformed Zn(OH)2 [magenta, (D)]. Same pulse widths are used as in (C and D).

The average forward-bias test currents recorded from the LTP behaviors under several conditions including Fig. 3 C and D are presented in Fig. 3E. The LTP response significantly varies with the amplitude of the reverse-bias input pulse. This is reasonable given that a higher reverse-bias potential expels ions from the diode junction more effectively. However, the LTP response does not accelerate linearly with the amplitude of the input pulse. Although input pulses of −1 V and −0.5 V only showed a slight difference in the sensitivity of the LTP response, applying a −0.2 V pulse resulted in a considerably sluggish increase in the forward-bias current. Similar to iontronic LTD based on the precipitate formation (Fig. 1), the enduring increase in the diode conductivity elicited by the precipitate dissolution can be interpreted as an increase in the synaptic weight. In the mammalian brain, repetitive synaptic activations trigger several different forms of LTP, which play crucial roles with LTD in encoding complex spatiotemporal patterns in neural circuits by elevating the synaptic weights on timescale longer than hours or days (42). The ionic diode with a preformed precipitate endows such LTP functionalities to an iontronic system.

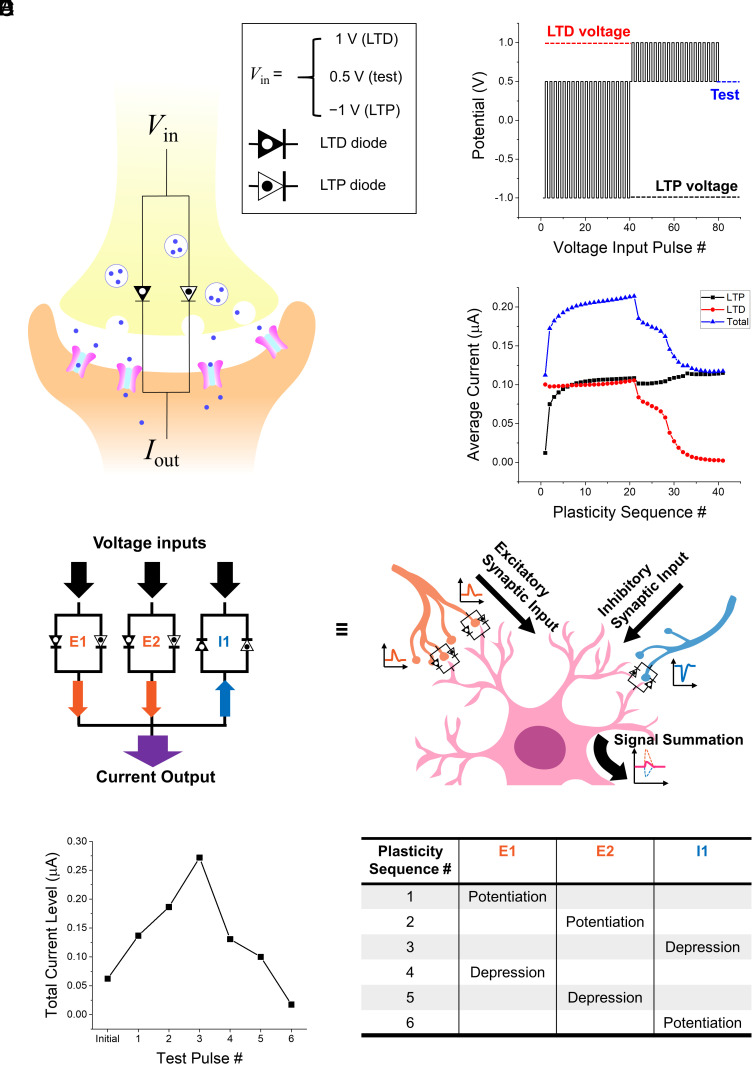

PIS for Neuromimetic Ionic Signal Integration with Plasticity.

Many complex neural functions such as thought, feeling, and memories are outcome of a complex cooperation between the synaptic plasticity at each synapse and the dendritic signal integration that occurs in individual neurons (29). Importantly, each synapse can undergo both potentiation and depression, and synaptic strength is bidirectionally modifiable. To demonstrate the potential of our ionic diode with plasticity features as a two-terminal neuromorphic signal-processing unit in an aqueous environment, we first constructed a PIS by incorporating a pair of ionic diodes with and without a preformed precipitate onto a microchip (Fig. 4A). The actual microchip design of PIS used in this study is shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S6A. One of the diodes interfaced with BaCl2(aq) and K2SO4(aq) was depressed by precipitation under a forward-bias input voltage (LTD diode), whereas the other diode with a preformed precipitate was potentiated by reverse bias-mediated salt dissolution (LTP diode). Additional p- and n-type gel plugs were installed next to the above diodes, allowing the Ag/AgCl electrodes to be immersed in chloride-based reservoir electrolytes, which also prevented unnecessary solution mixing. However, we employed PISs with a slightly different design, i.e., SI Appendix, Fig. S6B, to characterize the ionic currents flowing through both the LTP and LTD diodes separately (Fig. 4 B and C), where each diode is connected to its own separate input channel. Herein, the PIS whose input terminal is on the p-side of both the LTP and LTD diodes is defined as “excitatory”, as depicted in Fig. 4A. For device characterization, we applied a series of −1 V and +1 V pulses to an excitatory PIS to trigger LTP and LTD while simultaneously recording the forward-bias synaptic currents with +0.5 V test pulses between each input signal (Fig. 4B). The average forward-bias test currents obtained at each channel present synaptic potentiation and depression, as shown in Fig. 4C (see SI Appendix, Fig. S7 for the full time–current plots). The total synaptic current first increases up to ca. 0.22 μA under LTP and subsequently reverts to the initial current level of ca. 0.10 μA because of LTD. The perturbation of the ionic current flowing through the LTD channel during the LTP phase is insignificant and vice versa. If LTD precedes LTP (SI Appendix, Fig. S8), the LTD first leads a marked decrease in forward-bias ionic current (SI Appendix, Fig. S9A). Once the precipitate is formed at LTD diode, the diode becomes prone to STP and STD under reverse-bias input pulses. For confirmation, we applied two different test pulse widths, ten 20 s-pulses and ten 100 s-pulses, during the LTP period. The average test current plot clearly shows the influence of STP and STD (SI Appendix, Fig. S9B). The current level from the first 10 test pulses are higher than those from the succeeding 10 pulses, probably because the 20-s pulse is too short to induce an effective STD. This observation accords well with the nonlinear and time-dependent nature of the system, considering that the final state of the diode is dependent on the order of input pulse sequences.

Fig. 4.

(A) Conceptual illustration of two-terminal precipitation-based excitatory iontronic synapse (PIS) composed of ionic diode without precipitate (LTD diode) and another with preformed precipitate (LTP diode). Three input voltages are predefined for producing LTD (1 V), LTP (−1 V), and for measuring diode conductivity (0.5 V), respectively. (B) Pulse sequence for PIS characterization. Specifically, 20 100 s-LTP pulses are followed by 20 100 s-LTD pulses with 20 s-test pulses placed in between each LTP or LTD pulse. (C) Time average values of individual forward-bias test currents flowing through LTP diode (black), LTD diode (red), and output terminal electrode (blue), which are obtained from pulse sequence in (B). Actual circuit design and reservoir electrolytes used in (B and C) are fully described in SI Appendix, Fig. S6B. (D) Iontronic model of dendritic signal integration, inspired by hippocampal neural circuits. Model is composed of three independent PISs (E1, E2, I1), one of which has inhibitory configuration (I1). Inhibitory PIS is defined as inverted counterpart of excitatory PIS in terms of signal propagation (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). Output currents from all PISs are summed at terminal. (E) Total output current from three PIS postsynaptic currents, which are measured after every plasticity operation. Inset table summarizes plasticity sequence used for demonstration. LTP or LTD is induced by applying 2,000 s of constant input voltage to the PIS. Duration of forward-bias test pulse is 20 s. Actual circuit design and reservoir electrolytes used in (D and E) are fully described in SI Appendix, Fig. S6A.

Furthermore, we implemented multiple PISs to mimic the dendritic integration found in the nervous system, where several excitatory and inhibitory inputs with varying synaptic weights are merged into a single summed signal. As shown in Fig. 4D, an integrated output current is produced by the ionic currents at two excitatory PISs (E1 and E2) and one inhibitory PIS (I1), the synaptic weights of which can be adjusted by the time-dependent input signal history. We define the inhibitory PIS as an inverted version of an excitatory PIS, whose input terminal is at the n-side of both diodes. This suggests that the voltage polarity causing the plasticity effects as well as that of the forward-bias test pulses are opposite to those of the excitatory PIS, as shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S10. This three-PIS signal integration model is motivated by hippocampal neural circuits. The synaptic interconnections between the dentate gyrus (DG), CA3, and CA1 areas in the hippocampus play crucial parts in hippocampal memory functions (43). Particularly, our model replicates the dendritic integration that occurs at CA1, where the signals delivered from CA3 through glutamatergic excitatory synapses and those from DG interneurons through GABAergic inhibitory synapses converge. As a proof of concept, we elicited LTP or LTD individually at each synapse according to the arbitrary sequence listed in Fig. 4E. The summed current obtained by applying a forward-bias voltage of 0.5 V to every PIS, i.e., +0.5 V to E1 and E2 and −0.5 V to I1, increased after potentiation of the excitatory PISs or depression of the inhibitory PIS. The test current decreased upon the LTD of E1 and E2 and the LTP of I1. Analogous to a neural synapse, the PIS has the potential to evolve as a central nonlinear element for highly complex neuromorphic information processing in a fully aqueous environment.

Conclusion

We report the concept of mimicking biological synapses on a microchip-based aqueous ionic circuit by combining an ionic diode with chemical precipitation and dissolution. These chemical processes arising from appropriate input signals lead to temporal or long-lasting changes in the diode conductivity, which correspond to adjustments of the synaptic weight of this iontronic system. We attribute the plasticity phenomena to the formation and dissolution of precipitate, which acts as a physical blockage in the ionic circuitry, despite the negligible visual change in the precipitate during the dissolution process. The type of plasticity elicited and its time scale depend on the initial precipitate presence and the input signal parameters: voltage duration, amplitude, input pulse interval, and polarity. The LTP and LTD effects caused by prolonged input voltage signals are practically irreversible compared to the STP and STD based on rapid reversible precipitate dissolution and regeneration, which also present several properties similar to those of biological synaptic plasticity such as PPF. Furthermore, we develop an iontronic analog of a neural synapse called PIS, for more complex nonlinear information processing. The two parallel diodes in the PIS enable bidirectional modification of the synaptic weight between LTP and LTD without having to change the electrolyte during operation. We further demonstrate iontronic dendritic signal integration using three PISs with both excitatory and inhibitory configurations, similar to the hippocampal neural circuit. Importantly, our PIS is an ionic nonlinear element with a simple two-terminal structure operating in a fully aqueous environment. Its memristive behavior may pave the way for aqueous neuromorphic devices in conjunction with device optimization and simplification. Finally, the PIS could also serve as a seamless channel at a human-machine interface, which requires bilateral communication between the biological system and the electronic device (44, 45).

Materials and Methods

Glass Microchip Fabrication.

Marienfeld slide glasses (75 mm by 25 mm, 1 mm thick, Marienfeld-Superior) were used as substrates. A slide glass was cleaned in a piranha solution [H2SO4 (J.T. Baker)/H2O2 (Samchun Chemical) = 3:1] for 45 min and then washed with deionized (DI) water (NANOpure Diamond) several times. After removing the moisture on the surface with an air blower, the cleaned slide glass was dehydrated on a hot plate at 200 °C for 5 min and then cooled to room temperature. The slide was then spin-coated (YS-100MD, Won Corp.) with hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS, Samchun Chemical) at 7,000 rpm for 30 s. It was then baked on a hot plate at 110 °C for 90 s and was coated with a photoresist (PR; AZ4620, Microchem) at 7,000 rpm for 30 s. After soft baking the PR on a hot plate at 100 °C for 90 s, the slide glass was cooled to room temperature and aligned under a pattern mask. The PR on the slide glass was exposed to Ultraviolet (UV) light (365 nm) with an intensity of 21 mW cm−2 for 12 s (MDA-400M, Midas) and was developed with AZ 400 K developer (Merck) for 100 s. The slide glass was then washed with DI water, and the PR was hard-baked on a hot plate at 200 °C for 15 min. The slide glass was etched with a 6:1 buffered oxide etch solution (J. T. Baker) for 45 min at room temperature with stirring. Adhesion tape was attached to the opposite side of the slide glass for protection from the etching solution. Afterward, the etched slide glass was rinsed with DI water and sonicated (Branson 1510 Ultrasonic Cleaner, Bransonic) for 10 min to remove glass particles. The etched glass was then drilled with a 1.5-mm-diameter diamond drill at 15,000 rpm for making electrolyte solution inlet. The remaining PR was removed by 45 min of piranha cleaning. Another slide glass was also cleaned in piranha solution for 45 min and was used to cover the micropatterned glass. The two slide glasses were put together while rinsing them with DI water. The stacked glasses were bonded by thermal bonding, which was done by heating at 615 °C in a furnace (Wisetherm) for 6 h and slowly cooling to room temperature.

Photopolymerization of Polyelectrolyte Gels on a Microchip.

A microchannel was coated with 3-(trimethoxysilyl)propylmethacrylate (TMSMA) solution containing 1:2:2 volume ratio of TMSMA (Aldrich), AcOH (Aldrich), and MeOH (Aldrich). TMSMA acts as a linker between the polyelectrolyte and the glass surface. The microchannel was then cleaned with methanol. Diallyldimethylammonium chloride (DADMAC, Aldrich) and potassium 3-sulfopropyl acrylate (SPA, Aldrich) were used as the monomers to create positively (n-type) and negatively (p-type) charged polyelectrolyte gels, respectively. The 4 M DADMAC solution containing 1 wt % of N,N′-methylenebisacrylamide (MBAAm, Aldrich) for cross-linker and 1 wt% of lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP, Aldrich) for photoinitiator was used as a monomer solution for p-type gel. For n-type gel, 3 M SPA solution containing 1.6 wt% of MBAAm for cross-linker and 0.7 wt% of LAP for photoinitiator was used as a monomer solution. Methanol-rinsed microchannel was filled with DADMAC monomer solution, aligned under a photomask, and was exposed to UV light (365 nm) with an intensity of 21 mWcm−2 for 2 s for photopolymerization. Residual monomer solution was removed and the microchannel was rinsed with aqueous 10 mM potassium chloride (KCl, Aldrich) solution. The p-type hydrogel was made in a similar manner, with UV exposure time of 0.4 s. Glass cloning cylinders were attached to the drilled holes to make electrolyte solution reservoirs. The fabricated microchip was filled with and stored in aqueous 10 mM KCl solution.

Electrochemical and Plasticity Feature Characterization of Single-Diode Devices.

All electrochemical characterizations of single-diode devices were performed with CH Instruments model 660E electrochemical analyzer. Experiments were conducted with two-electrode configuration using Ag/AgCl electrodes at every reservoir terminal unless otherwise stated, where working electrode (WE) is immersed in p-side reservoir and reference and counter electrodes (RE and CE) in n-side.

For basic characterization of as-fabricated ionic diodes, cyclic voltammetry was performed with voltage range of +1 V to –1 V and 20 mV/s of scan rate. 10 mM KCl(aq) was used as reservoir electrolyte. Only diodes with high rectification ratio (I1 V/I–1 V > 10) were used for further plasticity experiments.

Plasticity experiments accompanying precipitate formations such as LTD and STP/STD, were carried out in precipitable pairs of reservoir electrolytes. 5 mM barium chloride (p-side; Aldrich) and 5 mM sodium sulfate solutions (n-side; Aldrich) were used for BaSO4 formation. Similarly, 5 mM barium chloride and 5 mM sodium carbonate (n-side; Aldrich) were used for BaCO3 formation. In the case of Zn(OH)2 formation, 5 mM zinc chloride (p-side; Aldrich) and 10 mM potassium hydroxide (n-side; Aldrich) were used while platinum wire was employed as electrode at n-side reservoir. For preparation of all the ionic diodes with preformed precipitates used in the experiments, constant +1 V forward-bias voltage was applied for 3,600 s to as-fabricated ionic diodes.

Plasticity experiments based on dissolution of precipitates were carried out in either inert reservoir electrolytes, 10 mM KCl(aq), for LTP, or in the same electrolyte conditions as in precipitation for STP/STD. Reverse-bias input voltages were applied to ionic diodes with preformed precipitate.

Characterization of a Single PIS.

For characterization of a single PIS circuit, PIS chips with two separated input channels (SI Appendix, Fig. S6B) were employed. Bipotentiostat (PGSTAT302N with BA module, Metrohm Autolab) was utilized for measuring individual ionic currents flowing through the LTP and LTD diodes, as well as the total ionic current. Ag/AgCl wires were used as input and output terminal electrodes. WE1 and WE2 were connected to each input terminal, and RE and CE were connected together to the output terminal. Identical voltage sequence was applied to the two WEs and the ionic currents (ILTP, ILTD) were recorded separately. +1 V pulse and –1 V pulse were applied for inducing LTD or LTP, respectively. Voltage pulse with 0.5 V of magnitude was applied to measure the electrical conductivity of each diode.

Iontronic Signal Integration with Multiple PISs.

For demonstration of iontronic signal summation with multiple PISs mimicking hippocampal neural circuits, PIS chips with a single input channel configuration were utilized (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A). Inhibitory PIS was connected in the opposite manner to excitatory PIS, as described in SI Appendix, Fig. S10. PIS chips were stimulated separately with 660E electrochemical analyzer for 2,000 s according to the pulse sequence presented in Fig. 4E, while the integrated output current was measured after every plasticity operation via bipotentiostat. Ag/AgCl wire was used for each input and output terminal electrode. For measuring summed signals, +0.5 V was applied for 20 s to WE1 which was connected to the input terminals of two excitatory PISs, and −0.5 V to WE2 which was connected to the input terminal of inhibitory PIS.

Monitoring Precipitate Formation and Dissolution via Optical Microscope.

An optical microscope (SMZ1500, Nikon) was used for monitoring the diode junction. A digital camera (EOS 750D, Canon) was connected to the optical microscope for capturing images of the diode junction, as well as for video recording of the precipitate formation and dissolution process.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Formation of BaSO4 precipitate during application of constant +1 V forward bias for 1 hr (fast forward speed at 32×real time). Reservoir electrolytes used were 5 mM BaCl2(aq) for p-side and 5 mM Na2SO4(aq) for n-side.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2021R1A5A1030054), (MSIT) (No. 2022R1A2C3004327), Korea Medical Device Development Fund grant funded by the Korea government (the Ministry of Science and ICT, the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy, the Ministry of Health & Welfare, the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety) (NTIS Number: 1711138201), Technology Innovation Program (or Industrial Strategic Technology Development Program) (20011101) funded By the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (Korea). We thank C.I. Shin for helpful discussions.

Author contributions

S.H.H., S.I.K., M.-A.O., and T.D.C. designed research; S.H.H. and S.I.K. performed research; S.H.H. and S.I.K. analyzed data; T.D.C. project supervision; and S.H.H. and S.I.K. wrote the paper.

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Von Neumann J., First draft of a report on the EDVAC. IEEE Ann. Hist. Comput. 15, 27–75 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chun H., Chung T. D., Iontronics. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 8, 441–462 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Z., et al. , Nanoionics-enabled memristive devices: Strategies and materials for neuromorphic applications. Adv. Electron. Mater. 3, 1600510 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hasegawa T., et al. , Learning abilities achieved by a single solid-state atomic switch. Adv. Mater. 22, 1831–1834 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han J. H., Kim K. B., Kim H. C., Chung T. D., Ionic circuits based on polyelectrolyte diodes on a microchip. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 3830–3833 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lovrecek B., Despic A., Bockris J., Electrolytic junctions with rectifying properties. J. Phys. Chem. 63, 750–751 (1959). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim S.-M., et al. , Ion-to-ion amplification through an open-junction ionic diode. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 13807–13815 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han S. H., Kwon S.-R., Baek S., Chung T.-D., Ionic circuits powered by reverse electrodialysis for an ultimate iontronic system. Sci. Rep. 7, 14068 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gabrielsson E. O., Janson P., Tybrandt K., Simon D. T., Berggren M., A four-diode full-wave ionic current rectifier based on bipolar membranes: Overcoming the limit of electrode capacity. Adv. Mater. 26, 5143–5147 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gabrielsson E. O., Berggren M., Polyphosphonium-based bipolar membranes for rectification of ionic currents. Biomicrofluidics 7, 064117 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Han J. H., et al. , Ion flow crossing over a polyelectrolyte diode on a microfluidic chip. Small 7, 2629–2639 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cayre O. J., Chang S. T., Velev O. D., Polyelectrolyte diode: Nonlinear current response of a junction between aqueous ionic gels. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 10801–10806 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hegedüs L., et al. , Nonlinear effects of electrolyte diodes and transistors in a polymer gel medium. Chaos 9, 283–297 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vlassiouk I., Siwy Z. S., Nanofluidic diode. Nano Lett. 7, 552–556 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun G., Senapati S., Chang H.-C., High-flux ionic diodes, ionic transistors and ionic amplifiers based on external ion concentration polarization by an ion exchange membrane: A new scalable ionic circuit platform. Lab. Chip 16, 1171–1177 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tybrandt K., Gabrielsson E. O., Berggren M., Toward complementary ionic circuits: The npn ion bipolar junction transistor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 10141–10145 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tybrandt K., Larsson K. C., Richter-Dahlfors A., Berggren M., Ion bipolar junction transistors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 9929–9932 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim K. B., Han J.-H., Kim H. C., Chung T. D., Polyelectrolyte junction field effect transistor based on microfluidic chip. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 143506 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hegedus L., Kirschner N., Wittmann M., Noszticzius Z., Electrolyte transistors: Ionic reaction− diffusion systems with amplifying properties. J. Phys. Chem. A 102, 6491–6497 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nam S.-W., Rooks M. J., Kim K.-B., Rossnagel S. M., Ionic field effect transistors with sub-10 nm multiple nanopores. Nano lett. 9, 2044–2048 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalman E. B., Vlassiouk I., Siwy Z. S., Nanofluidic bipolar transistors. Adv. Mater. 20, 293–297 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han S. H., et al. , Hydrogel-based iontronics on a polydimethylsiloxane microchip. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 6606–6614 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tybrandt K., Forchheimer R., Berggren M., Logic gates based on ion transistors. Nat. Commun. 3, 871 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janson P., Gabrielsson E. O., Lee K. J., Berggren M., Simon D. T., An ionic capacitor for integrated iontronic circuits. Adv. Mater. Technol. 4, 1800494 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li C., Xiong T., Yu P., Fei J., Mao L., Synaptic iontronic devices for brain-mimicking functions: Fundamentals and applications. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 4, 71–84 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Purves D., et al. , Neuroscience (Sinauer Associates. Inc., USA, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Citri A., Malenka R. C., Synaptic plasticity: Multiple forms, functions, and mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology 33, 18–41 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stuart G. J., Spruston N., Dendritic integration: 60 years of progress. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 1713–1721 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Magee J. C., Dendritic integration of excitatory synaptic input. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 1, 181–190 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rivnay J., et al. , Organic electrochemical transistors. Nat. Rev. Mater. 3, 17086 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bernards D. A., Malliaras G. G., Steady-state and transient behavior of organic electrochemical transistors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 17, 3538–3544 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gkoupidenis P., Schaefer N., Garlan B., Malliaras G. G., Neuromorphic functions in PEDOT: PSS organic electrochemical transistors. Adv. Mater. 27, 7176–7180 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gkoupidenis P., Koutsouras D. A., Malliaras G. G., Neuromorphic device architectures with global connectivity through electrolyte gating. Nat. Commun. 8, 15448 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gkoupidenis P., Schaefer N., Strakosas X., Fairfield J. A., Malliaras G. G., Synaptic plasticity functions in an organic electrochemical transistor. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 263302 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gerasimov J. Y., et al. , A biomimetic evolvable organic electrochemical transistor. Adv. Electron. Mater. 7, 2001126 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gerasimov J. Y., et al. , An evolvable organic electrochemical transistor for neuromorphic applications. Adv. Sci. 6, 1801339 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klausberger T., Somogyi P., Neuronal diversity and temporal dynamics: The unity of hippocampal circuit operations. Science 321, 53–57 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kirkwood A., Dudek S. M., Gold J. T., Aizenman C. D., Bear M. F., Common forms of synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus and neocortex in vitro. Science 260, 1518–1521 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zucker R. S., Regehr W. G., Short-term synaptic plasticity. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 64, 355–405 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Erulkar S., Rahamimoff R., The role of calcium ions in tetanic and post-tetanic increase of miniature end-plate potential frequency. J. Physiol. 278, 501–511 (1978). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abbott L. F., Regehr W. G., Synaptic computation. Nature 431, 796–803 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bliss T. V., Lømo T., Long-lasting potentiation of synaptic transmission in the dentate area of the anaesthetized rabbit following stimulation of the perforant path. J. Physiol. 232, 331–356 (1973). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hainmueller T., Bartos M., Dentate gyrus circuits for encoding, retrieval and discrimination of episodic memories. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 21, 153–168 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Song E., Li J., Won S. M., Bai W., Rogers J. A., Materials for flexible bioelectronic systems as chronic neural interfaces. Nat. Mater. 19, 590–603 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Keene S. T., et al. , A biohybrid synapse with neurotransmitter-mediated plasticity. Nat. Mater. 19, 969–973 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Formation of BaSO4 precipitate during application of constant +1 V forward bias for 1 hr (fast forward speed at 32×real time). Reservoir electrolytes used were 5 mM BaCl2(aq) for p-side and 5 mM Na2SO4(aq) for n-side.

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.